Study on the Transport Law and Corrosion Behavior of Sulfate Ions of a Solution Soaking FA-PMPC Paste

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiments

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportions of PMPC Paste and Specimen Preparation

2.3. Test Methods

2.3.1. Exposure of Specimens

2.3.2. Measurement of Sulfate Concentration

2.3.3. Fluidity, Strength and Deformation Measurement

2.3.4. Microstructural Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Microstructure Characteristics and Products

3.1.1. XRD Analysis

3.1.2. SEM-EDS Analysis

3.1.3. TG-DTG Analysis

3.1.4. MIP Analysis

3.2. SO42− Content Test and Analysis Inside PMPC Paste

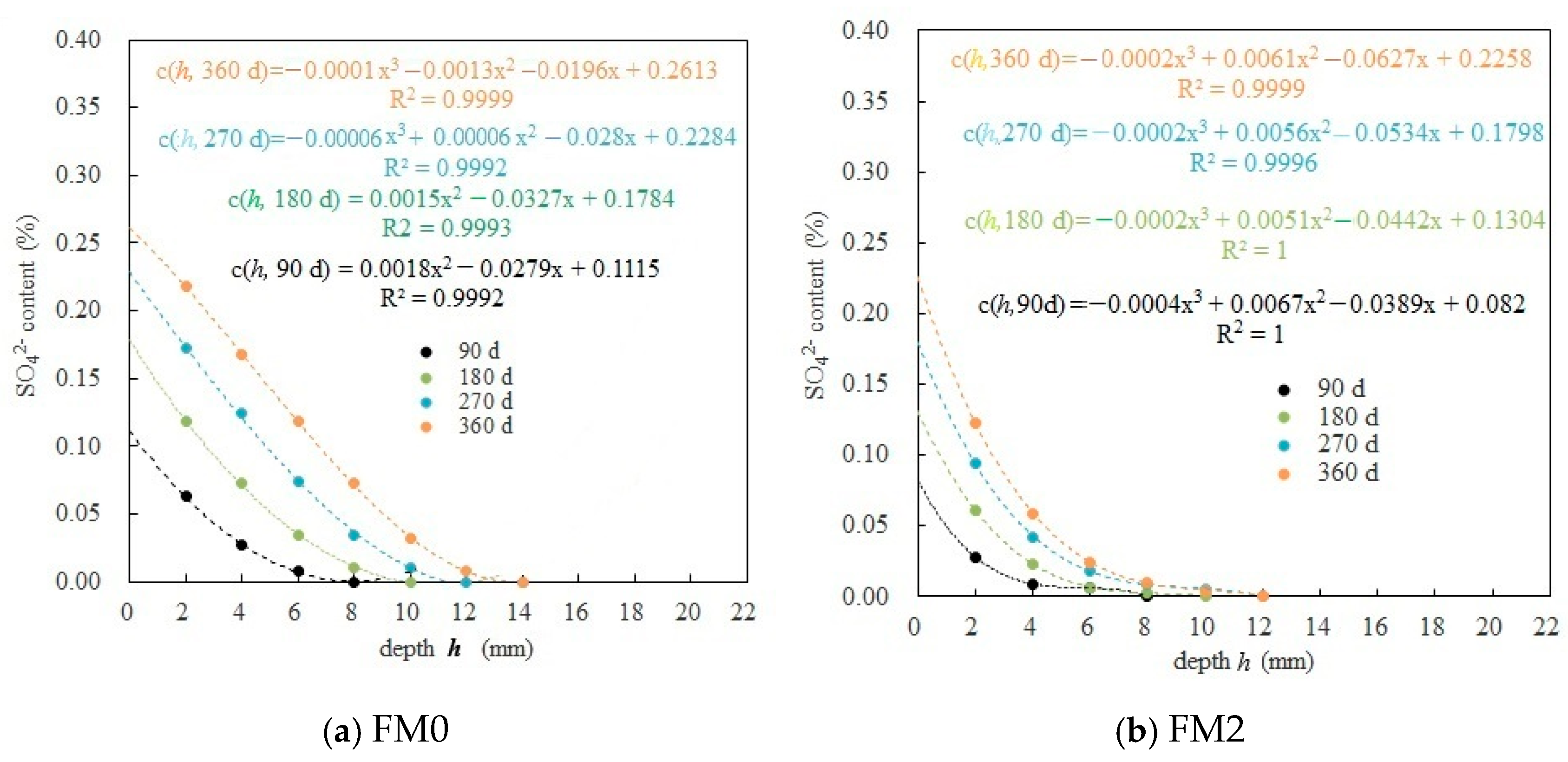

3.2.1. Diffusion Rule of SO42− Inside PMPC Paste

3.2.2. Calculation of Fitting Parameters for SO42− Diffusion in PMPC Paste

3.3. The Mechanical Properties of PMPC Specimens

3.3.1. Flexural and Compressive Strength

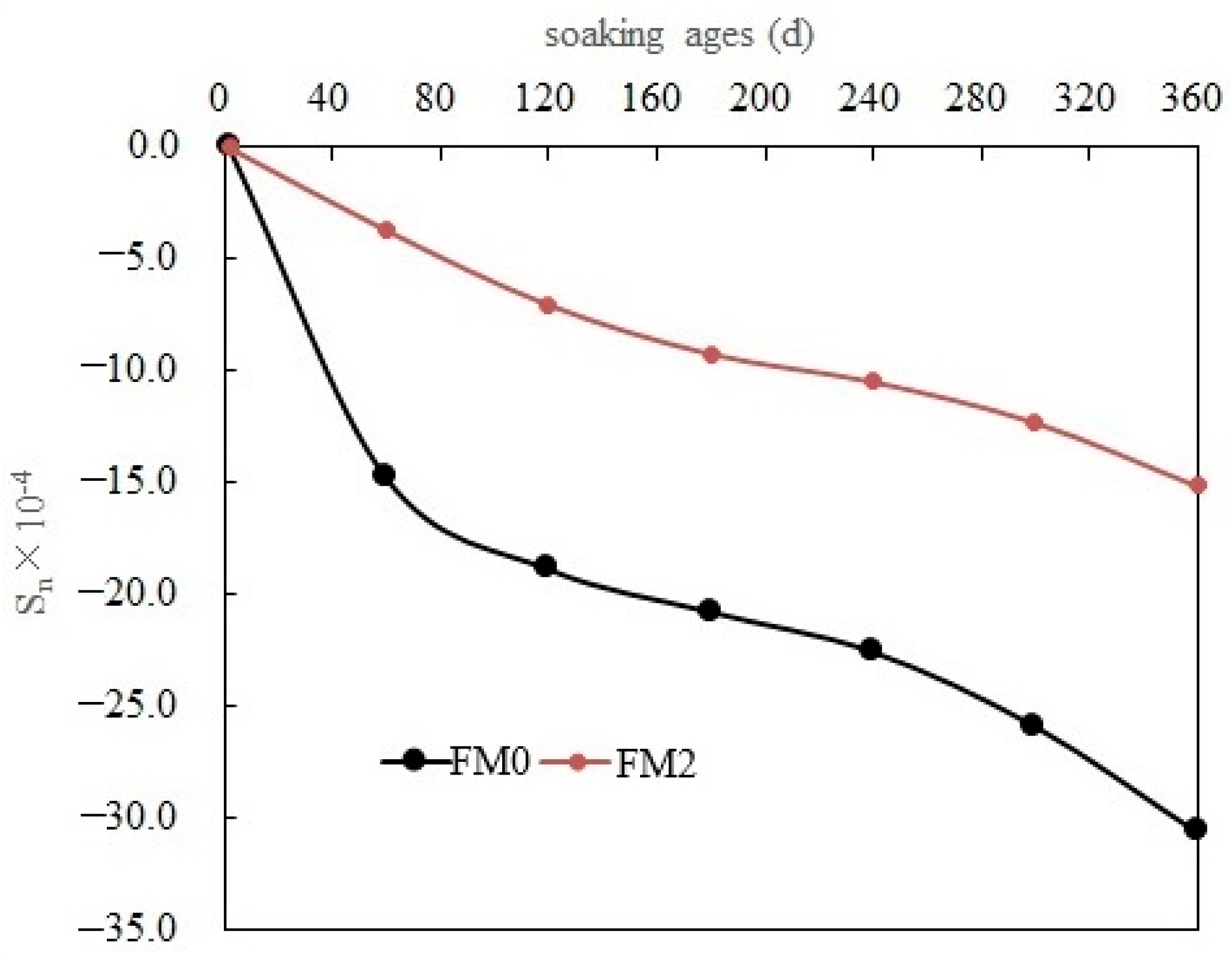

3.3.2. Deformation

4. Discussion

- a.

- The SO42− in the hardened PMPC paste becomes enriched in shallow areas close to the surface due to the lower initial porosity. The low W/B leads to the presence of unreacted KH2PO4 in FM0 that has been hydrated for 28 days (Figure 3). The KH2PO4 and excess MgO powders in PMPC paste undergo chemical reaction under water saturation conditions, and the newly formed MgKPO4·6H2O fills the pores of the hardened paste [31,32,33]. However, this process ends once the unreacted KDP is consumed. SO42− penetrated into hardened PMPC paste will combine with positive ions in the pore solution and form sulfate crystals (example for MgSO4·7H2O, Figure 3), which will fill up the pores of the PMPC paste [17,18,19]. The filling effects induce a denser structure in the PMPC paste, preventing the diffusion of shallow SO42− into deeper layers and improving the strengths of PMPC specimens. When a large amount of MgKPO4·6H2O and sulfate crystals are produced, the filling function will cause volume expansion of the PMPC test pieces.

- b.

- When PMPC test pieces are in a water-saturated state for a long time (for example, for longer than 180 days), the potassium ion on the surface of the MgKPO4·6H2O crystals will dissociate from K-O bonds and spread into the solution (Ksp = 2.4 × 10−11) [23,31]. The constitution water in MgKPO4·6H2O crystals is readily replaced by adjacent free water molecules due to the weak hydrogen bonds, leading to loss of stability in MgKPO4·6H2O crystals [31,32]. The dissociation of potassium ions and the replacement of bound water lead to the formation of surface fissures in MgKPO4·6H2O crystals; this process is usually called “dissolution of MgKPO4·6H2O crystals” [23,31,32,33]. Because of the lack of K+, the ions in the pore solution of PMPC paste precipitate out as mineral Mg3(PO4)2·22H2O crystals (Ksp = 8.0 × 10−24) (Figure 3) [23,31]; this process is usually called for “phase transition of MgKPO4·6H2O crystal”. The “dissociation and phase transition of MgKPO4·6H2O crystal” can cause deterioration in the pore structure of the PMPC paste (Figure 7 and Table 4) [31,32,33] and accelerate the permeation of SO42− into the PMPC paste [23], causing volume expansion of specimens and reducing the strength of the specimens [18,23].

- c.

- With the dissolution of the MgKPO4·6H2O crystals in hardened PMPC paste, the unreacted MgO grains exposed continue to hydrolyze into nongelatinous Mg (OH)2 crystals (Figure 3; the process is usually called “the slaking of MgO” [23,31]), which weakens the adhesion between unreacted MgO grains and MgKPO4·6H2O crystals and leads to the structural degradation of the PMPC paste (Figure 7 and Table 4) [16,31,32,33]. The slaking of MgO can accelerate the diffusion of SO42− into PMPC paste, cause rapid volume expansion of specimens [18], and reduce the strength of the specimens [16,23]. Synchronizing with the slaking of MgO grains, the SO42− combines with Mg2+ in the hardened paste to generate MgSO4·7H2O, which will consume some magnesium hydroxide, and the generated MgSO4·7H2O crystals will fill the capillary pores in the PMPC paste. The effect can ease the deterioration of the structure (Figure 7 and Table 4) but can still cause volume expansion of specimens [16,18].

- d.

- Through the ball-rolling effect of spherical particles in FA, the fluidity of the PMPC paste with some FA was improved, resulting in a decrease in the W/C of the paste with the same fluidity (Table 2) [13]. Some FA can optimize the particle size distribution of dead burnt MgO powders (Figure 1), causing the alkali component particles in the PMPC paste to be more closely piled up [14,15,16,17]. The Al element in FA dissolves and participates in the hydration reaction in an acidic solution, generating AlPO4 (Figure 3). The permeation of the Al and Si elements in FA leads to an obvious change in the morphology of MgKPO4·6H2O in the hardened paste (Figure 5c). All the above-mentioned effects make the structure of FM2 test pieces tend to be dense (Figure 5c), leading to an improvement in the 28-day strength of the specimens (Table 2). Due to it not being easy to penetrate the FM2 test piece with the corrosive medium, its initial resistance to sulfate attack is enhanced compared to the FM0 test piece. The SO42− that penetrated to the hardened paste will combine with Mg2+ in the pore solution, forming MgSO4·7H2O (Figure 3) and filling in the defects in the hardened paste, refining its pore structure (Figure 7). These effects will hinder the diffusion of SO42− in the hardened paste and decrease the strength change and volume expansion of the P2 specimens [18].

5. Conclusions

- a.

- In PMPC specimens subjected to one-dimensional SO42− corrosion, the relation between the diffusion depth of SO42− (h) and the SO42− concentration (c (h, t)) can be referred by a polynomial very well (the correlation coefficients ≥ 0.999). Under the same conditions, the c (h, t) and h0 (depth measured when sulfate content is 0) in the FM2 specimen containing fly ash were less than those of the FM0 specimen (reference). At 360-day immersion ages, the h0 value of the FM0 and FM2 specimens was 14 mm and 12 mm, respectively.

- b.

- The D (SO42− diffusion coefficient) of the FM0 and FM2 specimens in different corrosion ages was in all cases on the order of 10−7 mm2/s (one order of magnitude lower than the Portland cement concrete). Under the same conditions, the surface SO42− concentration c (0, t), the SO42− computed corrosion depth h00 and D of the FM2 specimen were all lower than those of the FM0 specimen. At 360-day immersion ages, the c (0, 360 d) and h00 in the FM2 specimen (0.2258% and 11 mm) were obviously smaller than that in the FM0 specimen (0.2613% and 14 mm), and the D of FM2 specimen (4.38 × 10−7) was 64.2% of the FM0 specimen (6.08 × 10−7).

- c.

- The strengths of the FM2 specimens soaked for 2 days (the benchmark strength) were larger than those of the FM0 specimens. The strengths of the PMPC test pieces first rose and then fell with the corrosion age, and the strength peaks were attained at the corrosion age of 180 days. The strength change of the FM2 specimens was significantly lower than that of the FM0 specimens. At 360-day immersion ages, the residual flexural/compressive strength ratios (360-day strength/benchmark strength) of the FM0 and FM2 specimens (95.6%/99.2% and 96.7%/98.3%) were all higher than 95%).

- d.

- The volume linear expansion rates of the PMPC specimens continued to increase with the immersion age, and at 360 days the volume linear expansion rates of FM0 and FM2 specimens were 30.61 × 10−4 and 15.14 × 10−4, respectively. The volume linear expansion rate of the FA-modified FM2 specimen was only 49.5% of that of the reference specimen FM0.

- e.

- This study only investigated the sulfate diffusion law and corrosion mechanism of FA-PMPC paste in a sulfate immersion environment. Research on the sulfate diffusion law of the FA-PMPC system under sulfate freeze–thaw and sulfate dry–wet cycle conditions has not yet been conducted. Subsequent research will continue in this area.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jiang, J.Y.; Zheng, H.R.; Sun, G.W.; Wang, F.J.; Liu, Z.Y. Numerical simulation of sulfate attack in concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2023, 26, 1047–1053. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.H.; Wang, Y.; Guo, B.B.; Lv, Y.; Niu, D.T. Evolution of fractal characteristics of concrete pore structure under coupling effect of temperature field and sulphate attack. Chin. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 52, 474–484. [Google Scholar]

- Chun, G.; Liu, D.W.; Cao, K.P.; Jian, Y.H. Study on the spatiotemporal evolution and prediction of internal porosity in concrete specimens under sulfate attack based on machine learning models. Results Eng. 2024, 24, 103258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Chen, B. Research progresses on magnesium phosphate cement: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 211, 855–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Hu, Z.; Shi, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, D.; Zhu, K.; Zhao, X.; Zhao, Z. Research progress on the properties and applications of magnesium phosphate cement. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 4001–4016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.R.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, B.; Wang, L.Y. Research progress on the setting time and solidification mechanism of magnesium phosphate cement: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 408, 133612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.W.; Han, J.M.; Yang, Y.Q. A review on magnesium potassium phosphate cement: Characterization methods. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 82, 108284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.H.; Qian, J.S.; You, C.; Fan, Y.R.; Li, Z.; Wang, H.T. Bond behavior and interfacial micro-characteristics of magnesium phosphate cement onto old concrete substrate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 166–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Sheikh, M.N.; Muhammad, N.S.H.; Feng, L.; Gao, D.Y.; Zhao, J. Interface bond performance of steel fibre embedded in magnesium phosphate cementitious composite. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 185, 648–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.H.; Zhou, J.; Yang, H.Y.; Yang, J.; Duan, K.; Feng, B.; Weng, J. Anti-corrosion performance of magnesium phosphate coating on carbon steel. Corros. Sci. Prot. Technol. 2017, 29, 515–520. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Z.; Li, Y.Y.; Xu, M.R.; Hong, X.; Hong, S.X.; Dong, B.Q. Electrochemical properties of aluminum tripolyphosphate modified chemically bonded phosphate ceramic anticorrosion coating. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 251, 118874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Wang, L. Effect of magnesium phosphate cement mortar coating on strand bond behaviour. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 64, 105613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Xu, X.H.; Yang, J.M.; Hu, X.M.; Xue, J.J.; He, Y.L.; Tang, Y.J. Effect of fly ash on the rheological properties of potassium magnesium phosphate cement paste. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.D.; Ji, T.; Wang, C.Q.; Sun, C.J.; Lin, X.J.; Hossain, K.M.A. Effect of the combination of fly ash and silica fume on water resistance of Magnesium–Potassium Phosphate Cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 106, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.W.; Ma, H.Y.; Shao, H.Y.; Li, Z.J.; Lothenbach, B. Influence of fly ash on compressive strength and micro-characteristics of magnesium potassium phosphate cement mortars. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 99, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.M.; Huang, P.; Mo, L.W.; Deng, M.; Qian, J.S.; Wang, A.G. Properties of magnesium potassium phosphate cement pastes exposed to water curing: A comparison study on the influences of fly ash and metakaolin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 203, 589–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, L.L.; Yang, J.M.; Xu, Z.Z.; Xu, X.C. Freezing and thawing resistance of MKPC paste under different corrosion solutions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 212, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.M.; Wang, L.M.; Jin, C.; Sheng, D. Effect of fly ash on the corrosion resistance of magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste in sulfate solution. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 237, 117639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Shi, T.F.; Li, J.Q. Effects of fly ash and quartz sand on water-resistance and salt-resistance of magnesium phosphate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.Z.; Meng, X.K.; Zhu, J.C. Corrosion resistance of magnesium phosphate cement under long-term immersion in different solutions. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 66, 105879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.J.; Qin, S.S.; Liu, T.J.; Jivkov, A. Experimental and numerical study of the effects of solution concentration and temperature on concrete under external sulfate attack. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 139, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Liu, T.; Zou, D.; Zhou, A. Compressive strength assessment of sulfate-attacked concrete by using sulfate ions distributions. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 293, 123550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Li, T.; Xu, X.H.; Yang, J.M.; Du, Y.B.; Hu, X.X.; Chen, W.L. Effect of steel slag powder on the sulfate corrosion behaviour of magnesium potassium phosphate cement paste. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 456, 139170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 2419-2005; Test Methods for Fluidity of Cement Mortar. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2005. (In Chinese)

- ASTM C1012-04; Standard Test Method for Length Change of Hydraulic Cement Mortars Exposed to a Sulfate Solution. ASTM International (American Society for Testing and Materials): West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2004. (In American)

- GB/T 749-2008; Test Method for Cement Resistance to Sulfate Corrosion. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2008. (In Chinese)

- Leng, F.G.; Ma, X.X.; Tian, G.F. Investigation of test methods of concreteunder sulfate corrosion. J. Southeast Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2006, 36, 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 5750.5-2023; Standard Examination Methods for Drinking Water-Part 5: Inorganic Nonmetallic Indices. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese)

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method for Strength of Cement Mortar. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2021. (In Chinese)

- JC/T 603-2004; Standard Test Method for Drying Shinkage of Mortar. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2004. (In Chinese)

- Chong, L.L. Water Corrosion Behavior and Modification Mechanism of Magnesium Potassium Phosphate CEMENT-based Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, Hunan University, Changsha, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Y.Y.; Li, L.; Li, T.; Wu, Q.Q.; Zhou, Y.L.; Yang, J.M. Water-immersion stability of self-compacting potassium magnesium phosphate cement paste. Materials 2023, 16, 2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, R.; Li, T.; Hu, X.; Mao, Y.; Hu, X.; Wang, Z. Experimental study on sulfate corrosion behavior in water saturated PMPC paste and effect of W/C. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Chemical Composition | MgO | SiO2 | CaO | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | Loi * | Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content/% | MgO powder | 91.85 | 3.68 | 3.14 | 0.865 | 0.17 | 0.12 | 0.175 |

| FA | 0.935 | 42.26 | 5.149 | 4.026 | 34.7 | 8.95 | 3.98 | |

| Symbol Name | mFA/ m(MgO+FA) | m(MgO+FA) /mKDP | mCR/ m(MgO+FA) | W/B | Fluidity (mm) | FS (MPa) | CS (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 72 h | 28 d | 72 h | 28 d | ||||||

| FM0 | 0 | 3:1 | 0.13 | 0.115 | 160 | 9.7 | 12.1 | 48.6 | 62.8 |

| FM1 | 10% | 0.110 | 158 | 10.2 | 12.8 | 54.9 | 64.9 | ||

| FM2 | 20% | 0.113 | 161 | 11.0 | 13.9 | 62.2 | 69.4 | ||

| FM3 | 30% | 0.116 | 158 | 10.4 | 13.0 | 59.1 | 66.5 | ||

| Sample Status (Quantity) | Project | Instrument | Analysis Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| small piece (one piece) | SEM | field emission scanning electron microscope, Nova Nano SEM 450, FEI Corporation, Hillsboro, OR, USA | gold spraying treatment |

| small piece (one piece) | EDS | X-ray energy spectrum analyzer, AZtec X-MaxN 80, Oxford Company, Abingdon, UK | |

| powder (3 g) | XRD | X-ray diffraction analyzer, D/max-RB, Rigaku, Tokyo, Japan | scanning range of 5–80°, and a scanning speed of 10°/min |

| powder (5 mg) | TG DTG | thermal analyzer, STA 409 PC/PG, Netzsch, Selb, Germany | Using nitrogen as a protective gas |

| small piece (3 piece) | MIP | fully automatic porosity analyzer, PoreMaster-60, Boynton Beach, FL, USA | low pressure 55 psi and high pressure 40,000 psi |

| Element | Atomic Percentage/% | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area A | Area C | Area D | Area E | Area F | Area G | Area H | |

| O K * | 68.95 | 76.30 | 58.84 | 60.68 | 59.17 | 77.76 | 57.79 |

| Na K | 2.82 | 4.35 | 1.91 | ||||

| Mg K | 9.02 | 17.55 | 16.95 | 10.61 | 0.99 | 10.19 | 9.29 |

| P K | 9.65 | 3.11 | 8.02 | 11.11 | 3.28 | 4.20 | |

| K K | 9.55 | 3.05 | 8.51 | 7.51 | 2.42 | 3.16 | |

| Ca K | - | - | 0.19 | 4.50 | 6.35 | 2.02 | |

| Al K | 2.46 | 15.49 | |||||

| Si K | 5.36 | 18.75 | 1.27 | ||||

| Fe K | 0.16 | 1.09 | |||||

| S K | - | 3.33 | |||||

| C K | 22.27 | ||||||

| Code and Corrosion Condition | Total Porosity/% | Pore Volume Distribution/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <50 nm | 50–200 nm | >200 nm | ||

| FM0, 28 d hydration ages | 8.96 | 49.65 | 9.21 | 41.14 |

| FM0, 5%Na2SO4 soaking for 360 d | 12.52 | 32.30 | 5.43 | 62.17 |

| FM2, 28 d hydration ages | 6.75 | 35.93 | 9.97 | 54.10 |

| FM2, 5%Na2SO4 soaking for 360 d | 8.10 | 57.54 | 6.09 | 36.37 |

| Name | t /d | cs (0, t)/% | c0 (h00, t)/% | h00 /(mm) | D /mm2/s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| 90 | 0.1115 | 0.0035 | 8 | 0.9686 | 3.87 × 10−7 | |

| 180 | 0.1784 | 0.0014 | 10 | 0.9804 | 3.01 × 10−7 | |

| 270 | 0.2284 | 0.0047 | 12 | 0.9763 | 5.81 × 10−7 | |

| 360 | 0.2613 | 0.0060 | 14 | 0.9970 | 6.08 × 10−7 | |

| FM2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - | - |

| 90 | 0.0820 | 0.0008 | 7 | 0.9902 | 2.88 × 10−7 | |

| 180 | 0.1304 | 0.0008 | 8 | 0.9939 | 2.73 × 10−7 | |

| 270 | 0.1798 | 0.0070 | 9 | 0.9611 | 4.07 ×10−7 | |

| 360 | 0.2258 | 0.0080 | 11 | 0.9646 | 4.38 ×10−7 |

| Code | Parameters | 2 d | 90 d | 180 d | 270 d | 360 d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FM0 | Flexural strength (MPa) | 11.4 | 14.1 | 14.1 | 12.8 | 10.6 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 4.39 | 5.53 | 6.74 | 6.40 | 6.98 | |

| Compressive strength (MPa) | 62.5 | 64.3 | 69.8 | 64.0 | 59.2 | |

| Coefficient of variation | 6.08 | 6.38 | 6.45 | 4.69 | 4.56 | |

| FM2 | Flexural strength (MPa) | 12.3 | 12.8 | 13.0 | 12.4 | 12.0 |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 4.88 | 6.25 | 6.92 | 5.65 | 5.83 | |

| Compressive strength (MPa) | 67.2 | 70.3 | 72.8 | 68.3 | 66.0 | |

| Coefficient of variation (%) | 5.80 | 5.97 | 6.32 | 4.69 | 4.39 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hou, Y.; Xu, Q.; Li, T.; Sa, S.; Mao, Y.; Xiong, C.; Hu, X.; Xu, K.; Yang, J. Study on the Transport Law and Corrosion Behavior of Sulfate Ions of a Solution Soaking FA-PMPC Paste. Materials 2026, 19, 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010202

Hou Y, Xu Q, Li T, Sa S, Mao Y, Xiong C, Hu X, Xu K, Yang J. Study on the Transport Law and Corrosion Behavior of Sulfate Ions of a Solution Soaking FA-PMPC Paste. Materials. 2026; 19(1):202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010202

Chicago/Turabian StyleHou, Yuying, Qiang Xu, Tao Li, Sha Sa, Yante Mao, Caiqiang Xiong, Xiamin Hu, Kan Xu, and Jianming Yang. 2026. "Study on the Transport Law and Corrosion Behavior of Sulfate Ions of a Solution Soaking FA-PMPC Paste" Materials 19, no. 1: 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010202

APA StyleHou, Y., Xu, Q., Li, T., Sa, S., Mao, Y., Xiong, C., Hu, X., Xu, K., & Yang, J. (2026). Study on the Transport Law and Corrosion Behavior of Sulfate Ions of a Solution Soaking FA-PMPC Paste. Materials, 19(1), 202. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010202