Anchorage and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bar Embedded in High-Strength Grout Mortar

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Program

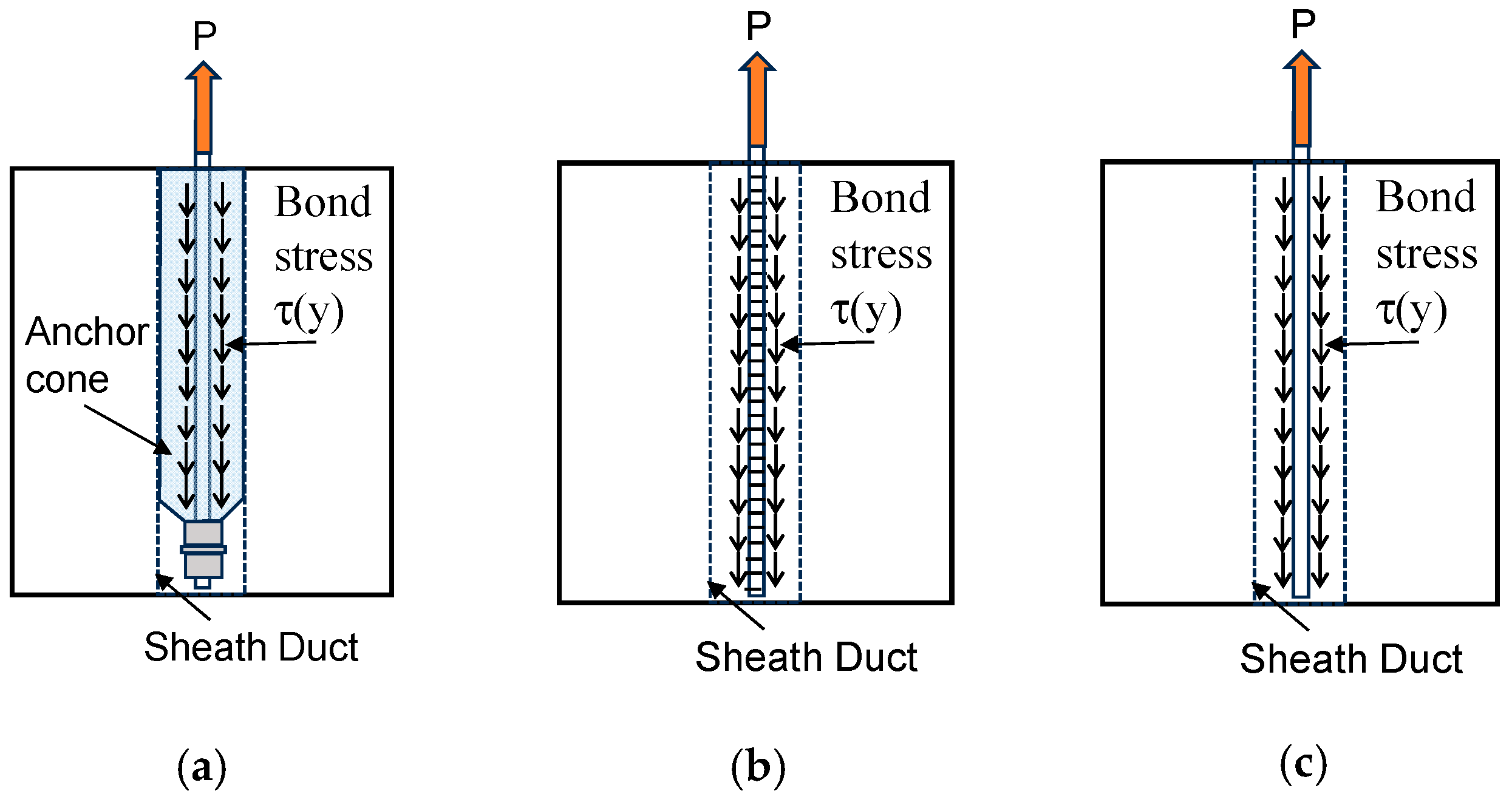

2.1. Outline of the Proposed Anchorage Methods

2.2. Outlines of Specimens

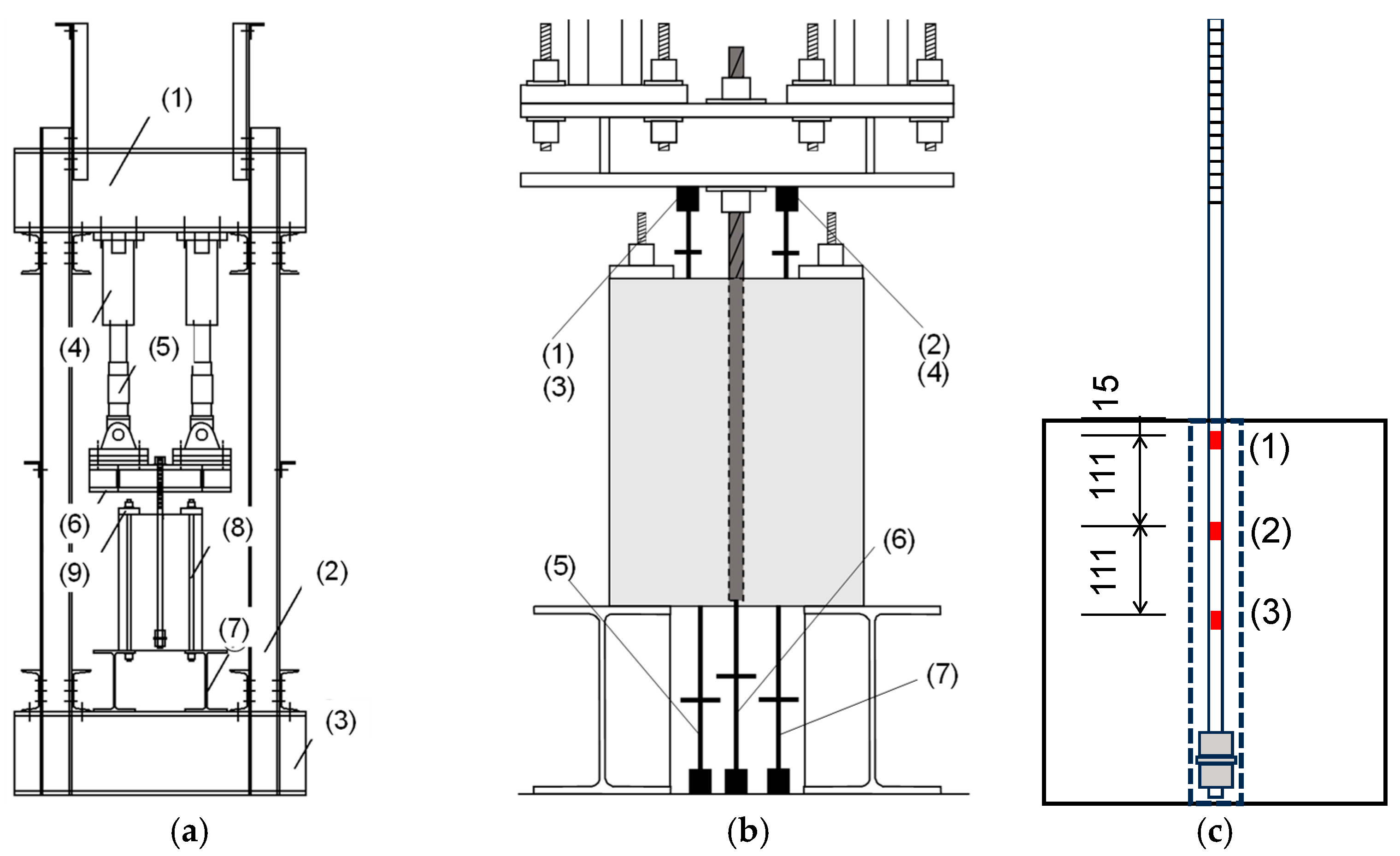

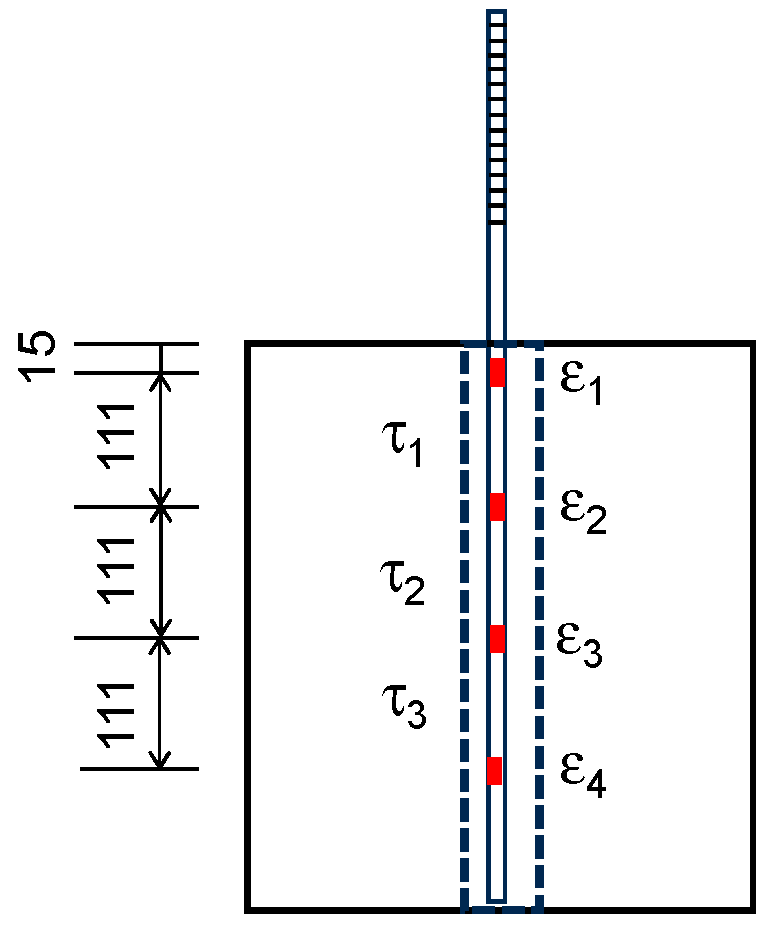

2.3. Loading Apparatus and Instrumentations

3. Test Results and Discussion

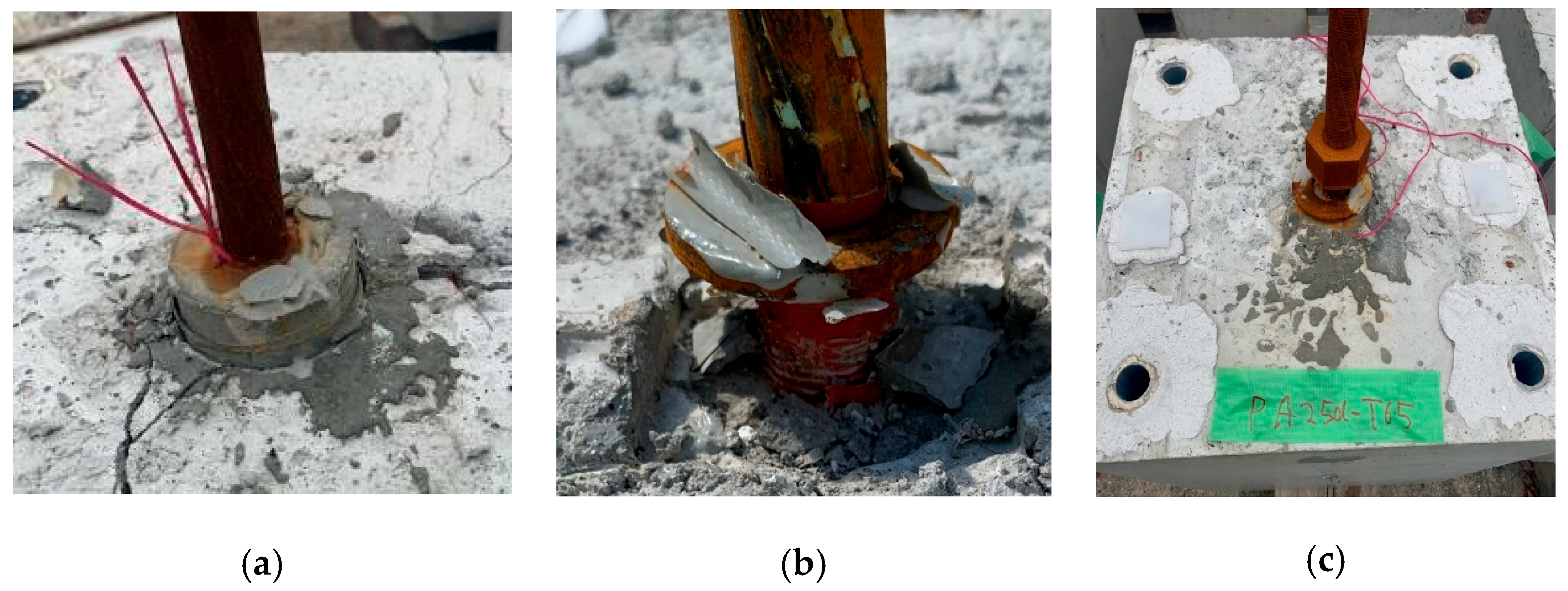

3.1. Primary Test Results and Observed Behavior

3.2. Pull-Out Load Versus Upper Pull-Out Displacement Relationships

3.3. Histories of the Axial Strains of SBPDN Bars

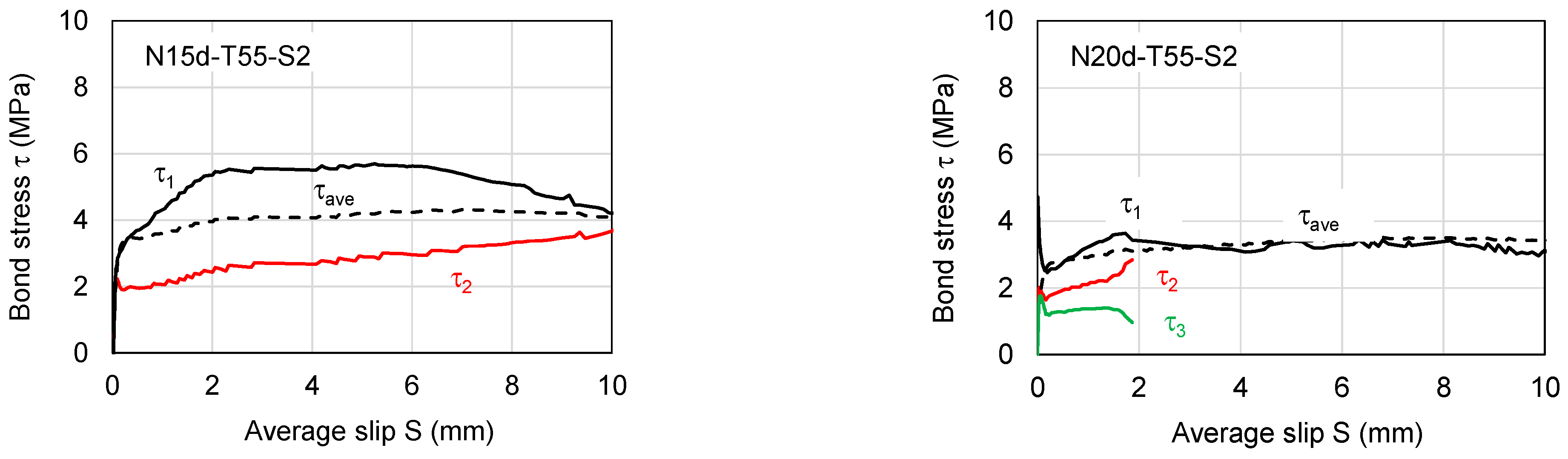

3.4. Bond Stress–Slip Behavior and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bars Embedded in Grout Mortar

4. Conclusions

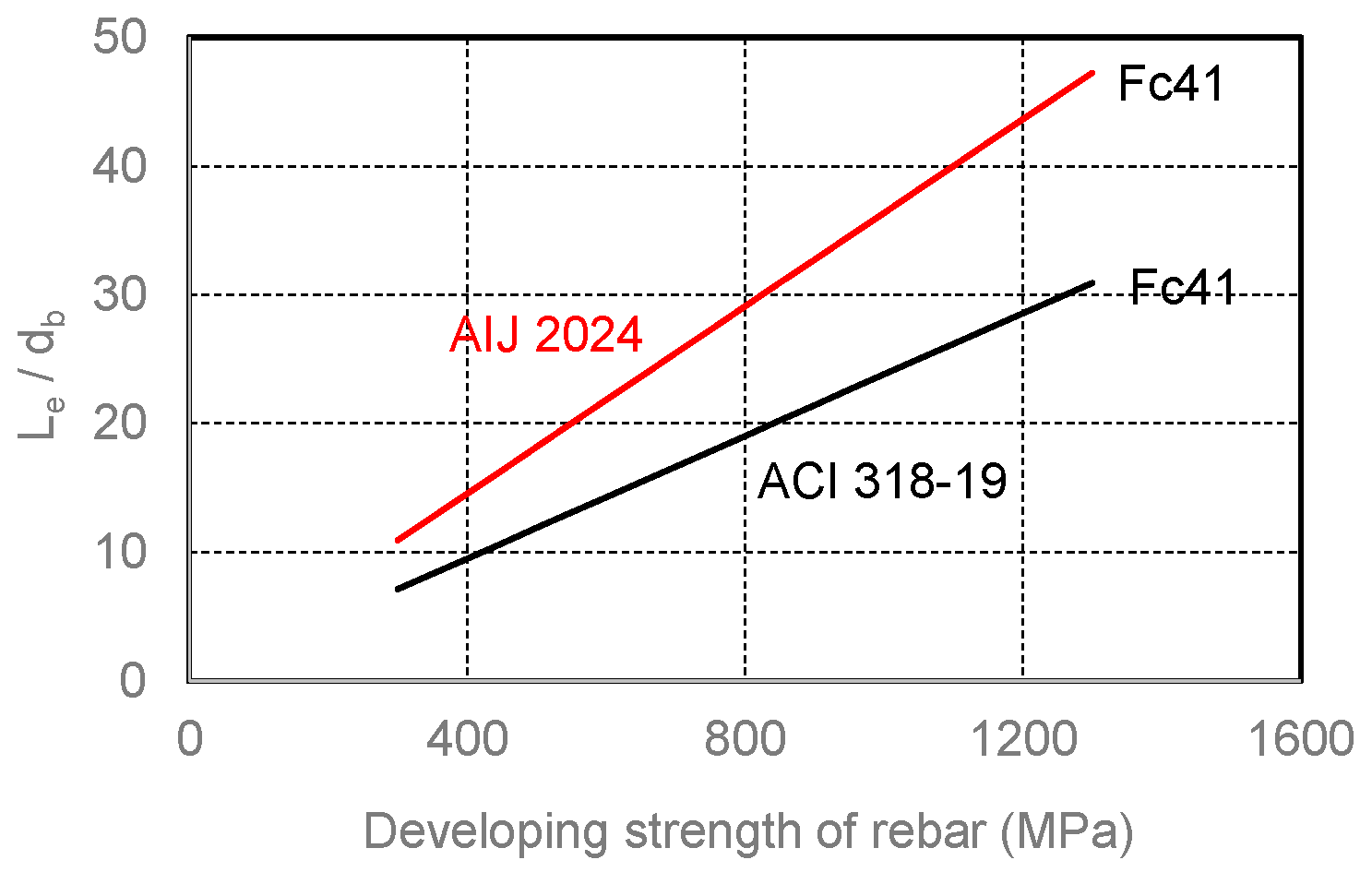

- Screwing two nuts to clamp one washer at the end of SBPDN bars (A-method) was observed to be able to provide SBPDN bars with sufficiently firm anchorage, enabling them to develop the ultra-high strength yield strength if the embedment length was twenty times the nominal diameter or longer. One A-specimen (A25d-T100-S1) was judged as indeterminate just because the jacks were out of tune before the pull-out load reached the yield load. The embedment length of 20 db is much shorter than those (24.4 db and 49.6 db) obtained by extrapolating ACI 318-19 and AIJ 2024 [6] provisions, respectively. For headed high-strength deformed bars and facilitates the application of SBPDN rebars to actual concrete components.

- Providing a rolling-threaded end region (S-method) was also observed to be able to ensure SBPDN bars fully develop the yield strength when the embedment length was twenty times the nominal diameter or longer. The lower limit of the average bond strength of the rolling-threaded SBPDN bars was observed to be about 15.0 MPa.

- Diameter of sheath duct did not significantly influence the ultimate pull-out resistant capacity of SBPDN bars embedded in grout mortar but did mitigate the requirement of contribution to the pull-out action provided by the bond between the bar and grout mortar. The larger diameter of the sheath duct seemed to increase the pull-out resistance by the proposed end anchorage A- and S- methods. Furthermore, the simplicity of the proposed A- and S-methods obviously could facilitate the injection of grout mortar and improve detailing in the joint regions of precast concrete components reinforced by SBPDN rebars.

- The SBPDN bar itself exhibited much lower bond strength than deformed bars, and the measured bond strength of 22.2 mm SBPDN bars varied between 2.84 MPa and 3.98 MPa. Therefore, to straightly anchor SBPDN bars into the beam–column joints or the foundation beams is not a feasible means because it would cause large premature slip, hinder the development of steel stress, and degrade the load-carrying capacity of concrete components reinforced by SBPDN rebars.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- BS EN 1998-2:2005 A2:2011; Eurocode 8 Design of Structures for Earthquake Resistance. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2011.

- NZS 3101:2006; Concrete Structures Standard. New Zealand Standard: Wellington, New Zealand, 2006.

- ASCE/SEI 7-22; Minimum Design Loads and Associated Criteria for Buildings and Other Structures. American Society of Civil Engineering (ASCE): Reston, VA, USA, 2022.

- ACI Committee 318. ACI 318R-19; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. American Concrete Institute: Country Club Hills, MI, USA, 2019.

- Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ). AIJ Seismic Performance Evaluation Guidelines for Reinforced Concrete Buildings Based on the Capacity Spectrum Method; Maruzen Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Architectural Institute of Japan (AIJ). Standard for Structural Calculation of Reinforced Concrete Structures; revised 2024; Maruzen Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, Japan, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Murao, N. Overview Report of Damages of Buildings and Infrastructures Caused by Hyogo-Ken Nanbu Earthquake; The Japan Institute of Architects: Tokyo, Japan, 1995; Available online: https://www.jia.or.jp/kinki/wp2022/wp-content/uploads/11-51.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2025). (In Japanese)

- Takahashi, A.; Ando, A.; Mun, S. Estimation of the economic damages caused by the Hanshin-Awaji Great Earthquake. Infrastruct. Plan. Rev. 1997, 14, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sezen, H.; Whittaker, A.S.; Elwood, K.J.; Mosalam, K.M. Performance of reinforced concrete buildings during the August 17, 1999, Kocaeli, Turkey earthquake, and seismic design and construction practice in Turkey. Eng. Struct. 2003, 25, 103–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Zealand Department of Building and Housing. Structural Performance of Christchurch CBD Buildings in the 22 February 2011 Aftershock; Expert Panel Report; New Zealand Department of Building and Housing: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hotel Grand Chancellor, Christchurch. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hotel_Grand_Chancellor%2c_Christchurch (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Asian Disaster Reduction Center. 2016 Kumamoto Earthquake Survey Report (Preliminary); Kobe, Japan, 2016. Available online: https://www.adrc.asia/publications/201604_KumamotoEQ/ADRC_2016KumamotoEQ_Report_1.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2025).

- 2023 Turkey–Syria Earthquakes. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2023_Turkey%E2%80%93Syria_earthquakes (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Priestley, M. Overview of PRESS research program. PCI J. 1991, 36, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M.; Sritharan, S.; Conley, J.; Pampanin, S. Preliminary results and conclusions from the PRESS five-story precast concrete test buildings. PCI J. 1999, 44, 42–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurama, Y.; Pessiki, S.; Sause, R.; Lu, L. Seismic behavior and design of unbonded post-tensioned precast concrete walls. PCI J. 1999, 44, 72–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurama, Y. Seismic design of unbonded post-tensioned precast concrete walls with supplemental viscous damping. ACI Struct. J. 2000, 97, 648–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, T.; Restrepo, J.; Mander, J. Seismic performance of precast reinforced and prestressed concrete walls. J. Struct. Div. 2003, 129, 286–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, F.; Sause, R.; Pessiki, S. Analytical and experimental lateral load behavior of unbonded posttensioned precast concrete walls. J. Struct. Div. 2007, 133, 1531–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belleri, A.; Schoettler, M.; Restrepo, J.; Fleischman, R. Dynamic behavior of rocking and hybrid walls in a precast concrete building. ACI Struct. J. 2014, 111, 661–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; French, C.W.; Sritharan, S. Performance of a Precast Wall with End Columns Rocking Wall System with Precast Surrounding Structure. ACI Struct. J. 2020, 117, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.P.; Takeuchi, T.; Okuda, S.; Ohada, S. Fundamental study on seismic behavior of resilient concrete column. Proc. Jpn. Concr. Inst. 2013, 35, 1501–1506. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Funato, Y.; Takeuchi, T.; Sun, Y.P. Modeling and application of bond behavior of ultra-high strength bars with spiraled grooves on the surface. Proc. JCI 2012, 34, 157–162. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y.P.; Cai, G.C. Seismic behavior of circular concrete columns reinforced by low bond ultra-high strength rebars. J. Struct. Eng. 2023, 149, 04023126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, J.; Yuan, S.; Sun, Y.P. Seismic Performance of Precast Drift-Hardening Concrete Walls Connected by Grout-Sheath Duct. Materials 2024, 17, 5165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.W.; Cheng, C.K. Modeling of bond stress-slip relationships of reinforcing bars embedded in concrete with different strengths. Materials 2020, 13, 3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.F.; Zhao, X.M. Unified Bond Stress–Slip Model for Reinforced Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2013, 139, 1951–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FIB-Federation Internationale Du Beton. Fib Model Code for Concrete Structures, 2010; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Comite Euro-International Du Beton. RC Elements under Cyclic Loading; Thomas Telford Publications: London, UK, 1996; pp. 70–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tamai, S.; Masuda, Y. Bond Behavior of Steel Bars Embedded in Grout. JCI Proc. 1995, 17, 1207–1212. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Tada, A.; Shima, H.; Hisano, K. Bond Behavior of Bars Embedded in Grout Injected into Sheath Duct of Precast Concrete Components. JCI Proc. 1996, 18, 557–562. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Hosoi, K.; Ichiki, T.; Nakazuka, K. Study on Testing of Bond Strength of PC bars embedded in Grout. JCI Proc. 2002, 24, 811–816. (In Japanese) [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki, Y.; Tajima, Y.; Kitayama, K. Experimental Study on Bond Strength of PC Bars embedded in Grout. In Proceedings of the AIJ Annual Convention 2007, Fukuoka, Japan, 29–31 August 2007; Volume 4, pp. 141–142. (In Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Darwin, D.; O’Reilly, M.; Lequesne, R.D.; Ghimire, K.P.; Hano, M. Anchorage of Conventional and High-Strength Headed Reinforcing Bars; SM Report No. 117; University of Kansas Center for Research: Lawrence, KS, USA, 2016; Available online: https://kuscholarworks.ku.edu/entities/publication/05c9e009-6cd3-4935-b6bd-5c4fca619fbb (accessed on 5 November 2025).

- Thompson, M.K.; Ziehl, M.J.; Jirsa, J.O.; Breen, J.E. CCT Nodes Anchored by Headed Bars—Part 1: Behavior of Nodes. ACI Struct. J. 2006, 102, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.K.; Jirsa, J.O.; Breen, J.E. CCT Nodes Anchored by Headed Bars—Part 2: Capacity of Nodes. ACI Struct. J. 2007, 103, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh, S.A.; Uzumeri, S.M. Strength and Ductility of Tied Concrete Columns. J. Struct. Div. 1980, 106, 1079–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical Stress-Strain Model for Confined Concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | fc′ [MPa] | fg′ [MPa] | Embedment Length (mm) | Anchor Type | Diameter of Sheath Duct (mm) | Configuration Type of Hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A15d-T55-S2 | 39.6 | 72.2 | 15 db (333) | A | 55 | Overlapped |

| A15d-T65-S1 | 36.0 | 66.3 | 65 | single | ||

| A15d-T65-S2 | 39.6 | 72.2 | 65 | Overlapped | ||

| A15d-T100-S1 | 33.3 | 65.1 | 100 | single | ||

| S15d-T55-S2 | 39.6 | 74.5 | S | 55 | Overlapped | |

| N15d-T55-S2 | 39.6 | 74.5 | N | 55 | Overlapped | |

| A20d-T55-S2 | 38.3 | 74.8 | 20 db (444) | A | 55 | Overlapped |

| A20d-T65-S1 | 33.3 | 65.1 | 65 | single | ||

| A20d-T65-S2 | 38.0 | 74.2 | 65 | Overlapped | ||

| S20d-T55-S2 | 38.3 | 74.8 | S | 55 | Overlapped | |

| N20d-T55-S2 | 38.0 | 74.2 | N | 55 | Overlapped | |

| A25d-T55-S2 | 40.7 | 74.2 | 25 db (555) | A | 55 | Overlapped |

| A25d-T65-S1 | 36.2 | 75.5 | 65 | single | ||

| A25d-T65-S2 | 40.7 | 74.2 | 65 | Overlapped | ||

| A25d-T100-S1 | 37.5 | 75.5 | 100 | single |

| Notation | Grade | [GPa] | [MPa] | [%] | [MPa] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D10 | SD295A | 167.8 | 344 | 0.20 | 436 | |

| U22.2 | S1 Specimens | SBPDN1275 | 212.0 | 1355 | 0.65 | 1479 |

| S2 Specimens | 211.1 | 1316 | 0.62 | 1455 | ||

| Specimen | Pmax [kN] | Py [kN] | Pmax/Py | Ultimate or Failure Mode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A15d-T55-S2 | 468 | 509 | 0.920 | PSD |

| A15d-T65-S1 | 361 | 524 | 0.690 | PSD |

| A15d-T65-S2 | 520 | 509 | 1.022 | PY |

| A15d-T100-S1 | 427 | 524 | 0.815 | PSD |

| S15d-T55-S2 | 456 | 509 | 0.896 | PSD |

| N15d-T55-S2 | 100 | 509 | 0.197 | PB |

| A20d-T55-S2 | 520 | 509 | 1.022 | PY |

| A20d-T65-S1 | 528 | 524 | 1.008 | PY |

| A20d-T65-S2 | 520 | 509 | 1.022 | PY |

| S20d-T55-S2 | 520 | 509 | 1.022 | PY |

| N20d-T55-S2 | 109 | 509 | 0.214 | PB |

| A25d-T55-S2 | 520 | 509 | 1.022 | PY |

| A25d-T65-S1 | 534 | 524 | 1.019 | PY |

| A25d-T65-S2 | 521 | 509 | 1.024 | PY |

| A25d-T100-S1 | 494 | 524 | 0.943 | Indeterminate |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Itoh, T.; Ueda, R.; Son, B.; Kuno, A.; Sun, Y. Anchorage and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bar Embedded in High-Strength Grout Mortar. Materials 2026, 19, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010002

Itoh T, Ueda R, Son B, Kuno A, Sun Y. Anchorage and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bar Embedded in High-Strength Grout Mortar. Materials. 2026; 19(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleItoh, Takaaki, Ryoya Ueda, Bunka Son, Ayami Kuno, and Yuping Sun. 2026. "Anchorage and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bar Embedded in High-Strength Grout Mortar" Materials 19, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010002

APA StyleItoh, T., Ueda, R., Son, B., Kuno, A., & Sun, Y. (2026). Anchorage and Bond Strength of SBPDN Bar Embedded in High-Strength Grout Mortar. Materials, 19(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010002