The Preparation of ZnFe2O4 from Coal Gangue for Use as a Photocatalytic Reagent in the Purification of Dye Wastewater via the PMS Reaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Chemicals

2.1.2. Coal Gangue Raw Materials

2.2. Acid Leaching and Extraction of Coal Gangue

2.3. Preparation of Catalysts

2.4. Experimental Procedures

2.5. Characterization and Analysis Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Resource Utilization Process of Coal Gangue

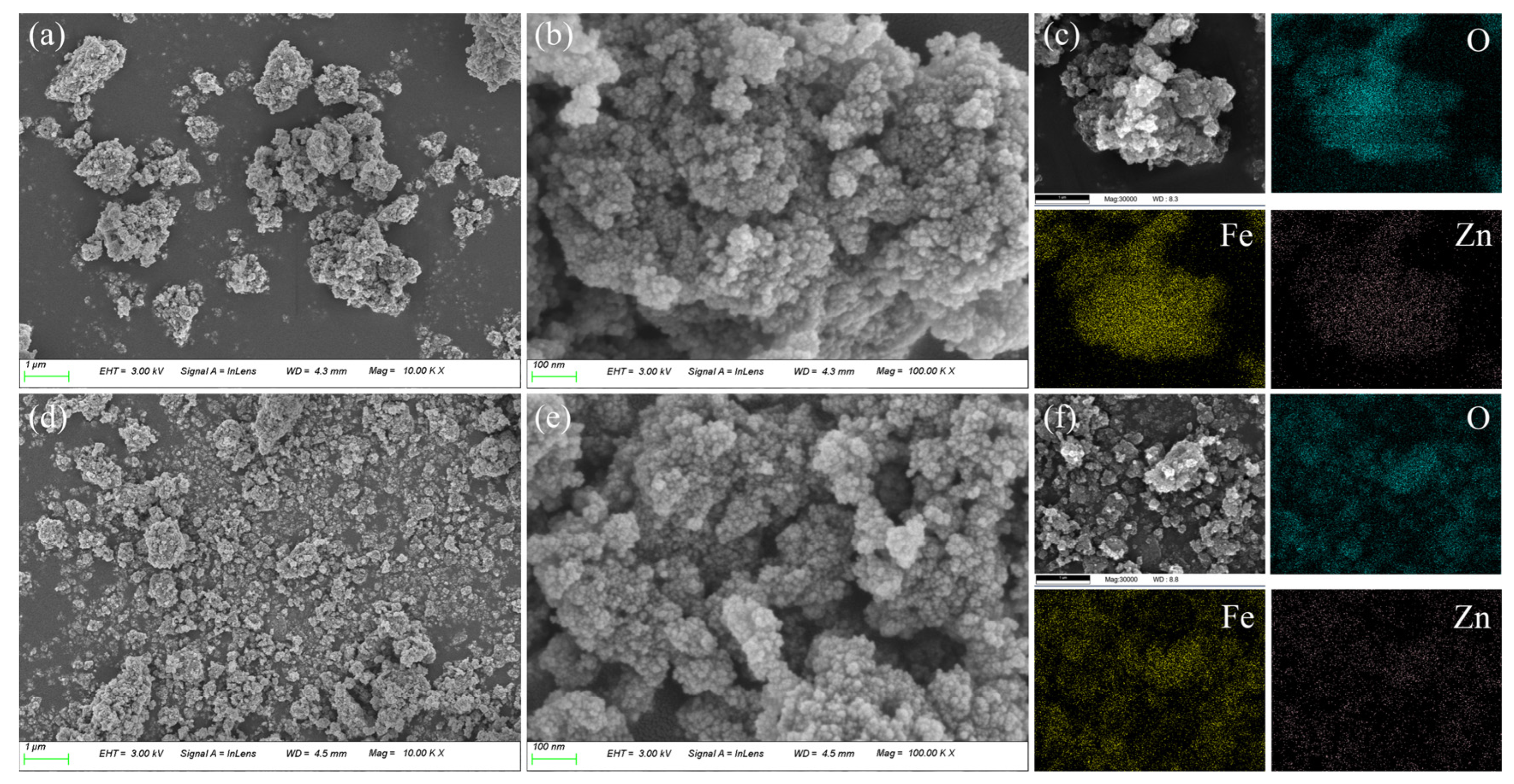

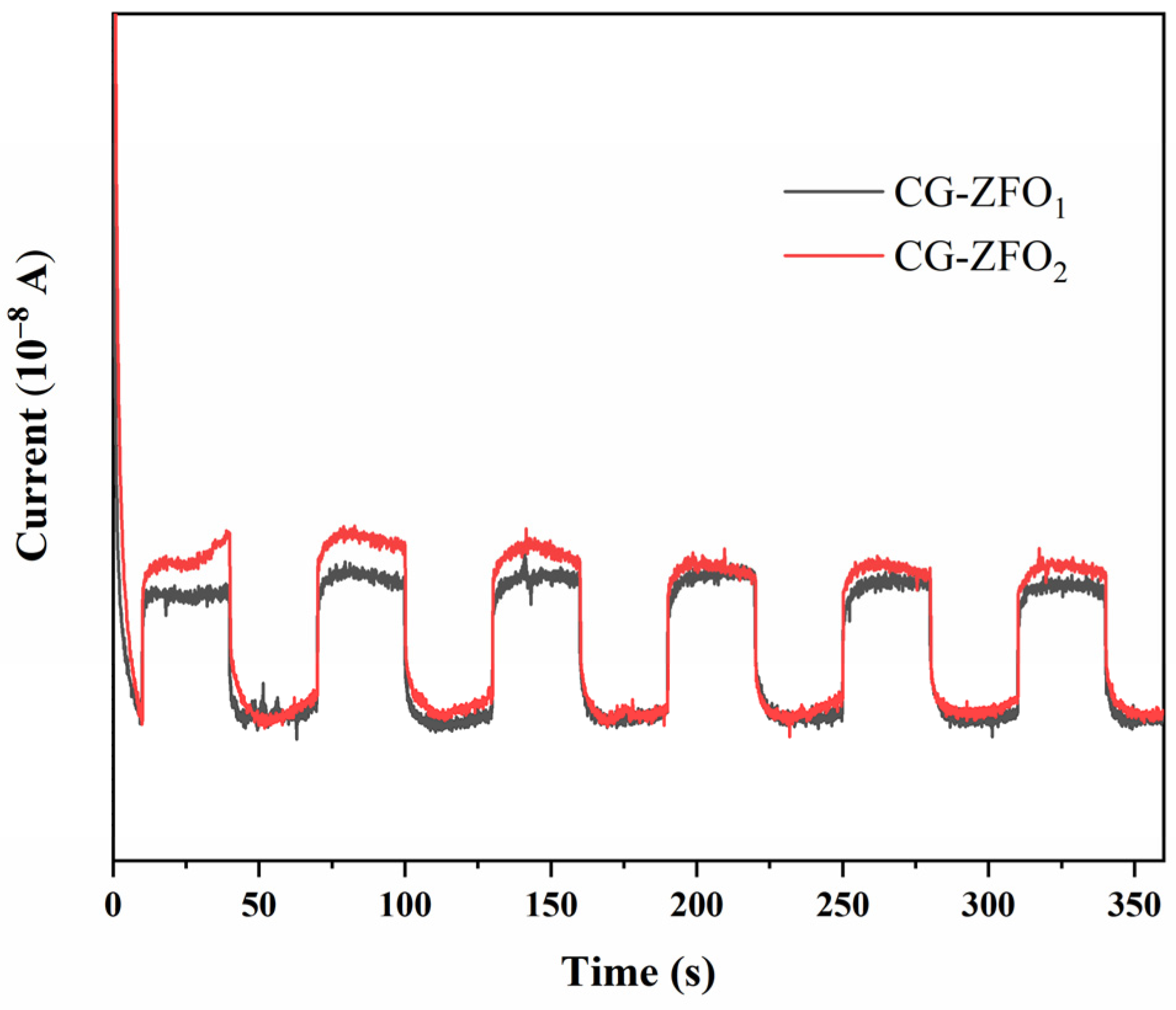

3.2. Catalyst Characterization

3.3. Catalytic Performance Study of CG-ZFO Catalysts

3.3.1. Effects of CTAB Addition on RhB Degradation

3.3.2. Effects of Catalytic Systems on RhB Degradation

3.3.3. Effects of Initial pH on RhB Degradation

3.3.4. Effects of PMS Dosage on RhB Degradation

3.4. Degradation Mechanism Study

3.4.1. Identification of Active Species

3.4.2. XPS Analysis

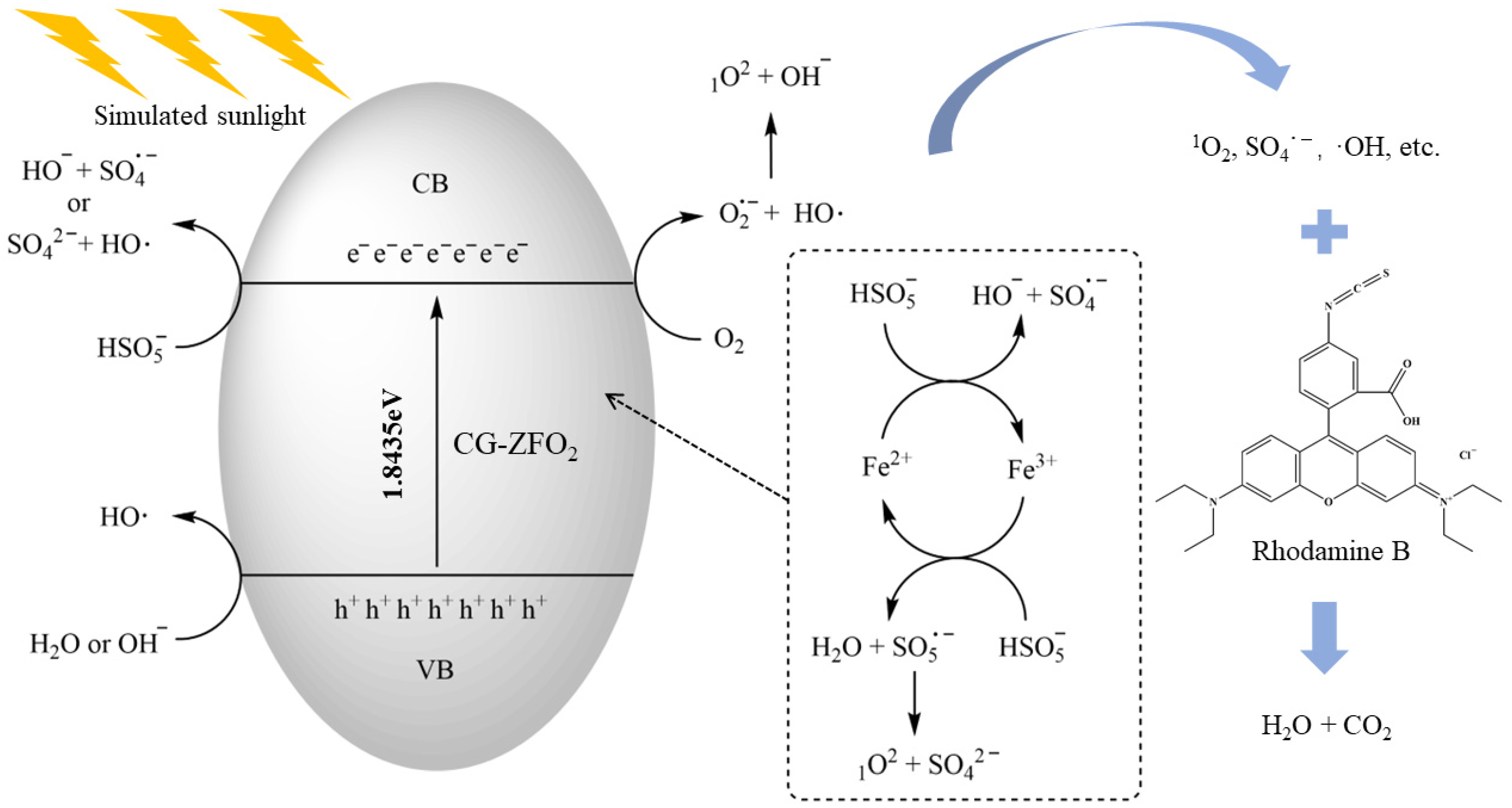

3.4.3. Degradation Mechanism

4. Conclusions

- Through activation and acid leaching processes, Fe2O3 in the coal gangue was effectively removed. Subsequently, the leaching solution was subjected to extraction using tributyl phosphate (TBP) followed by back-extraction with deionized water. This series of operations increased the iron (Fe) concentration in the solution from 46.29% to 99.64%, making it a feasible iron source for the synthesis of the ZnFe2O4 catalyst.

- CG-ZFO was characterized by XRD, SEM, FT-IR, etc., showing that the catalysts have a pure ZnFe2O4 crystal structure. The addition of CTAB resulted in a smaller crystal grain size, higher dispersion, and better light absorption capability and photo-generated charge separation capability of the catalyst.

- A series of degradation experiments based on CG-ZFO further confirmed the enhancement of the catalyst’s photoelectric performance by CTAB addition and the synergistic action between SS, PMS, and CG-ZFO. It was found that when the initial pH was 7.85 and the PMS dosage was 150 mg, the degradation performance of the catalytic system was maximized.

- Combining the conclusions of radical-quenching experiments, EPR, and XPS, it was determined that in the SS/CG-ZFO2/PMS catalytic system, 1O2 was the main active species. The CG-ZFO2 catalyst mainly relies on the FeII/FeIII redox cycle and the generation of photo-generated electron-holes to promote the activation of PMS for the degradation of RhB.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, Q.Q.; Ghosh, M.K.; Cai, S.L.; Liu, X.H.; Lu, L.; Muddassir, M.; Ghorai, T.K.; Wang, J. Three new Zn (II)-based coordination polymers: Optical properties and dye degradation against RhB. Polyhedron 2024, 247, 116731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhadi, S.; Siadatnasab, F.; Khataee, A. Ultrasound-assisted degradation of organic dyes over magnetic CoFe2O4@ZnS core-shell nanocomposite. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 37, 298–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Isari, A.A.; Payan, A.; Fattahi, M.; Jorfi, S.; Kakavandi, B. Photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B and real textile wastewater using Fe-doped TiO2 anchored on reduced graphene oxide (Fe-TiO2/rGO): Characterization and feasibility, mechanism and pathway studies. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 462, 549–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Guo, W.; Shi, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, A.; Hao, F.; Xing, L. Degradation of Rhodamine B by persulfate activated with Fe3O4: Effect of polyhydroquinone serving as an electron shuttle. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 240, 338–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelpohl, A. Applications of AOPs in wastewater treatment. Water Sci. Technol. 2007, 55, 207–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, D.; Lin, Y.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, A.; Yang, J.; Luo, L. Remediation of persistent organic pollutants in aqueous systems by electrochemical activation of persulfates: A review. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 260, 110125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, S.C.; Shirini, F.; Pendashteh, A.R. Advanced oxidation process as a green technology for dyes removal from wastewater: A review. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2021, 40, 1467–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Gong, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Deng, H. Progress and problems of water treatment based on UV/persulfate oxidation process for degradation of emerging contaminants: A review. J. Water Process Eng. 2024, 58, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Li, R.; Yu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Yan, B.; Chen, G. Efficient degradation of bentazone via peroxymonosulfate activation by 1D/2D γ-MnOOH-rGO under simulated sunlight: Performance and mechanism insight. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 741, 140492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Ma, H.; Shang, J.; Cheng, X. Synthesis of magnetic NiFe2O4/CuS activator for degradation of lomefloxacin via the activation of peroxymonosulfate under simulated sunlight illumination. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 288, 120664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Y.; Li, W.; Gao, J.Y.; Li, C.B.; Xiao, Y.S.; Liu, X.; Song, D.A.; Zhang, J.G. Activation of peroxymonosulphate using a highly efficient and stable ZnFe2O4 catalyst for tetracycline degradation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abouri, M.; Benzaouak, A.; Elouardi, M.; Hamdaoui, L.E.; Zaaboul, F.; Azzaoui, K.; Hammouti, B.; Sabbahi, R.; Jodeh, S.; Belghiti, M.A.E.; et al. Enhanced photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B using polyaniline-coated XTiO3(X = Co, Ni) nanocomposites. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pylnev, M.; Su, T.S.; Wei, T.C. Titania augmented with TiI4 as electron transporting layer for perovskite solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 549, 149224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, J.; Chiu, M.N.; Krishnan, S.; Kumar, R.; Rifah, M.; Ahlawat, P.; Jha, N.K.; Kesari, K.K.; Ruokolainen, J.; Gupta, P.K. Emerging Trends in Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles for Biomedical and Environmental Applications. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2024, 196, 1008–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjaneyulu, B.; Chinmay, V.; Chauhan, S.A.C.; Carabineiro, M. Recent Advances on Zinc Ferrite and Its Derivatives as the Forerunner of the Nanomaterials in Catalytic Applications. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2023, 34, 1887–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arimi, A.; Megatif, L.; Granone, L.I.; Dillert, R.; Bahnemann, D.W. Visible-light photocatalytic activity of zinc ferrites. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2018, 366, 118–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, P.; Li, W.; Zhou, T.; Jin, Y.; Gu, M. Physical and photocatalytic properties of zinc ferrite doped titania under visible light irradiation. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2004, 168, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, C.; Jauhar, S.; Kumar, V.; Singh, J.; Singhal, S. Synthesis of zinc substituted cobalt ferrites via reverse micelle technique involving in situ template formation: A study on their structural, magnetic, optical and catalytic properties. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2015, 156, 188–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, X.S.; Pham, T.D.; Ngo, K.D. Effect of different salt precursors on zinc ferrite synthesis and their photo-Fenton activity. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 17957–17967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renuka, L.; Anantharaju, K.S.; Sharma, S.C.; Vidya, Y.S.; Nagaswarupa, H.P.; Prashantha, S.C.; Nagabhushana, H. Synthesis of ZnFe2O4 Nanoparticle by Combustion and Sol Gel Methods and their Structural, Photoluminescence and Photocatalytic Performance. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 20819–20826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X. Zinc ferrite nanoparticles: Simple synthesis via lyophilisation and electrochemical application as glucose biosensor. Nano Express 2021, 2, 024001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakil, M.; Inayat, U.; Ashraf, M.; Tanveer, M.; Gillani, S.S.A.; Dahshan, A. Photocatalytic performance of novel zinc ferrite/copper sulfide composites for the degradation of Rhodamine B dye from wastewater using visible spectrum. Optik 2023, 272, 170353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Wang, D. Synthesis and characterization of low-cost zeolite NaA from coal gangue by hydrothermal method. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 791–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C.; Zheng, S.; Di, Y.; Sun, Z. A review of the synthesis and application of zeolites from coal-based solid wastes. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2022, 29, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; Ma, A.; Wang, X.; Zheng, X. Review of the Preparation and Application of Porous Materials for Typical Coal-Based Solid Waste. Materials 2023, 16, 5434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, R.; Song, S.; Feng, S.; Lian, M. Extraction of Aluminum and Iron Ions from Coal Gangue by Acid Leaching and Kinetic Analyses. Minerals 2022, 12, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; Li, Y.; Yan, J.; Shu, X.Q. Efficient Extraction of SiO2 and Al2O3 from Coal Gangue by Means of Acidic Leaching. Adv. Mater. Res. 2014, 878, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Li, F.; Zhong, Q.; Bao, H.; Wang, B.; Huang, J.; Zhang, Y. Separation of aluminum and silica from coal gangue by elevated temperature acid leaching for the preparation of alumina and SiC. Hydrometallurgy 2015, 155, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Ma, B.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Extraction of valuable components from coal gangue through thermal activation and HNO3 leaching. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2022, 113, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lv, L.; Chen, Y.; Zhong, B.; Tang, S. Extraction performance and mechanism of TBP in the separation of Fe3+ from wet-processing phosphoric acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 272, 118822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, M.; Masoudi, H. Zinc Ferrite Nanoparticles: New Preparation Method and Magnetic Properties. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2014, 27, 2563–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raland, R.D.; Borah, J.P. Efficacy of heat generation in CTAB coated Mn doped ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2017, 50, 035001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadeem, N.; Zahid, M.; Tabasum, A.; Mansha, A.; Jilani, A.; Bhatti, I.A.; Bhatti, H.N. Degradation of reactive dye using heterogeneous photo-Fenton catalysts: ZnFe2O4 and GO-ZnFe2O4 composite. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, L.; Yan, Z.; Yang, M.; Yin, H.; Fu, H.; Jin, M.; Feng, H.; Zhou, G.; Shui, L. Two-dimensional colloidal particle assembly in ionic surfactant solutions under an oscillatory electric field. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 475302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesi, S.; Nezamzadeh-Ejhieh, A. An experimental design study of photocatalytic activity of the Z-scheme silver iodide/tungstate binary nano photocatalyst. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 105440–105456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, H.; Dou, X.; Shi, H. 2D/2D step-scheme α-Fe2O3/Bi2WO6 photocatalyst with efficient charge transfer for enhanced photo-Fenton catalytic activity. Chin. J. Catal. 2021, 42, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, X.Z.; Ma, J.W.; Lu, Y.; Chang, Z.; Luo, D.Y.; Li, L.; Feng, Q.; Xu, L.J.; et al. A Novel SnO2/ZnFe2O4 Magnetic Photocatalyst with Excellent Photocatalytic Performance in Rhodamine B Removal. Catalysts 2024, 14, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagesh, T.; Ramesh, K.; Ashok, B.; Jyothi, L.; Vijaya Kumar, B.; Upender, G. Insights into charge transfer via Z-scheme for Rhodamine B degradation over novel Co3O4/ZnFe2O4 nanocomposites. Opt. Mater. 2023, 143, 114140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manohar, A.; Chintagumpala, K.; Kim, K.H. Magnetic hyperthermia and photocatalytic degradation of rhodamine B dye using Zn-doped spinel Fe3O4 nanoparticles. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2021, 32, 8778–8787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Liu, J.; Yu, R.H.; Zhu, M.G. Photocatalytic Activity of Magnetically Retrievable Bi2WO6/ZnFe2O4 Adsorbent for Rhodamine B. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2014, 50, 5200604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loan, T.T.N.; Dai-Viet, N.V.; Lan, T.H.N.; Anh, T.T.D.; Hai, Q.N.; Nhuong, M.C.; Duyen, T.C.N.; Thuan, V.T. Synthesis, characterization, and application of ZnFe@ZnO nanoparticles for photocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B under visible-light illumination. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2022, 25, 102130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.H.; Huang, Y.F.; Huang, C.; Chen, C.Y. Efficient decolorization of azo dye Reactive Black B involving aromatic fragment degradation in buffered Co2+/PMS oxidative processes with a ppb level dosage of Co2+-catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 170, 1110–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.; Chen, D.; Hao, Z.; Tang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Li, T.; Tian, B.; Yan, C.; Luo, Y.; Jia, B. Efficient degradation of Rhodamine B in water by CoFe2O4/H2O2 and CoFe2O4/PMS systems: A comparative study. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, R.; Zhao, J.; Shen, N.; Ma, T.; Su, Y.; Ren, H. Efficient degradation of 2,4-dichlorophenol in aqueous solution by peroxymonosulfate activated with magnetic spinel FeCo2O4 nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Chen, Y.J.; Lu, Y.A.; Ma, X.Y.; Feng, S.F.; Gao, N.; Li, J. Synthesis of magnetic CoFe2O4/ordered mesoporous carbon nanocomposites and application in Fenton-like oxidation of rhodamine B. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 14396–14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Guo, R.; Liang, M.; Li, L. Regulation of ZnFe2O4 synthesis for optimizing photoelectric response and its application for ciprofloxacin degradation: The synergistic effect with peroxymonosulfate and visible light. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2022, 165, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, C.; Ganeshraja, A.S. Visible-light-induced photocatalysis and peroxymonosulfate activation over ZnFe2O4 fine nanoparticles for degradation of Orange II. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 2296–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ai, J.; Zhang, H. The mechanism of degradation of bisphenol A using the magnetically separable CuFe2O4/peroxymonosulfate heterogeneous oxidation process. J. Hazard. Mater. 2016, 309, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Pervez, M.N.; Sun, P.; Cao, C.; Li, B.; Naddeo, V.; Jin, W.; Zhao, Y. Highly efficient removal of bisphenol A by a novel Co-doped LaFeO3 perovskite/PMS system in salinity water. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 801, 149490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, P.; Li, C.; Wang, D.; Jia, C.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Geng, L. Electronic modulation of fiber-shaped-CoFe2O4 via Mg doping for improved PMS activation and sustainable degradation of organic pollutants. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siriwardane, R.V.; Poston, J.A. Characterization of copper oxides, iron oxides, and zinc copper ferrite desulfurization sorbents by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1993, 68, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, P.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Chen, M.; Li, Y.; Niu, W.; Ye, Q. Defect-rich carbon based bimetallic oxides with abundant oxygen vacancies as highly active catalysts for enhanced 4-aminobenzoic acid ethyl ester (ABEE) degradation toward peroxymonosulfate activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 395, 124936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Sun, J.; Ding, J.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, J.; Sun, T. Catalytic Oxidation of VOCs over SmMnO3 Perovskites: Catalyst Synthesis, Change Mechanism of Active Species, and Degradation Path of Toluene. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 14275–14283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhiman, P.; Kumar, A.; Rana, G.; Sharma, G. Cobalt–zinc nanoferrite for synergistic photocatalytic and peroxymonosulfate-assisted degradation of sulfosalicylic acid. J. Mater. Sci. 2023, 58, 9938–9966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Zhang, X. Insights into the mechanism of multiple Cu-doped CoFe2O4 nanocatalyst activated peroxymonosulfate for efficient degradation of Rhodamine B. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 137, 382–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Wei, Y.; Cao, H.; Xin, Y.; Wang, C. Modulation of reactive species in peroxymonosulfate activation by photothermal effect: A case of MOF-derived ZnFe2O4/C. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 306, 122732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | CaO | K2O | MgO | P2O5 | ZrO2 | Cr2O3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 44.80 | 17.40 | 20.60 | 6.64 | 3.54 | 3.11 | 1.14 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.11 |

| Composition | SiO2 | Al2O3 | Fe2O3 | TiO2 | CaO | K2O | MgO | P2O5 | ZrO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Content | 70.90 | 12.00 | 2.95 | 9.82 | 0.14 | 2.97 | 0.42 | 0.091 | 0.23 |

| Element | Fe | Al | Ca | Mg | K | Na | P | Zn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaching solution | 46.29 | 32.16 | 9.90 | 6.75 | 2.84 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 0.10 |

| Back-extraction solution | 99.640 | 0.009 | 0.0329 | 0.003 | 0.085 | 0.027 | 0.084 | 0.120 |

| Catalytic System | kobs (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| SS/CG-ZFO1/PMS | 0.0138 | 0.9939 |

| SS/CG-ZFO2/PMS | 0.0187 | 0.9962 |

| No. | Catalyst System | Dye | Irradiation/Time (min) | Degradtion | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SS+PMS+CG-ZFO2 | Rhodamine B | Xe-lamp 120 min | 90.12% | Present work |

| 2 | SnO2 | Rhodamine B | Xe-lamp 120 min | 54.7% | [37] |

| 3 | ZnFe2O4 | Rhodamine B | Xe-lamp 120 min | 32.5% | [37] |

| 4 | SnO2/ZnFe2O4 | Rhodamine B | Xe-lamp 120 min | 72.6% | [37] |

| 5 | Co3O4 | Rhodamine B | UV light 240min | 61% | [38] |

| 6 | ZnFe2O4 | Rhodamine B | UV light 240 min | 43% | [38] |

| 7 | 0.8Co3O4/0.2ZnFe2O4 | Rhodamine B | UV light 240 min | 92% | [38] |

| 8 | ZnFe2O4 nanoparticles | Rhodamine B | UV light 300 min | 97% | [39] |

| 9 | ZnFe@CuS 25% | Rhodamine B | visible light 150 min | 93% | [22] |

| 10 | ZnFe2O4/Bi2WO6 | Rhodamine B | visible light 180 min | 93% | [40] |

| 11 | ZnFe2O4-0%@ZnO | Rhodamine B | visible light 240 min | 34.62% | [41] |

| 12 | ZnFe2O4-50%@ZnO | Rhodamine B | visible light 240 min | 91.87% | [41] |

| Catalytic System | kobs (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| PMS | 0.0055 | 0.9927 |

| SS/PMS | 0.0067 | 0.9904 |

| CG-ZFO2/PMS | 0.0082 | 0.9864 |

| SS/CG-ZFO2/PMS | 0.0187 | 0.9962 |

| Initial pH | kobs (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 2.70 | 0.0161 | 0.9888 |

| 4.48 | 0.0187 | 0.9962 |

| 7.85 | 0.0209 | 0.9943 |

| 9.76 | 0.0203 | 0.9950 |

| PMS Dosage (mg) | kobs (min−1) | R2 |

|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0.0187 | 0.9962 |

| 70 | 0.0244 | 0.9954 |

| 90 | 0.0356 | 0.9954 |

| 110 | 0.0469 | 0.9857 |

| 130 | 0.0554 | 0.9885 |

| 150 | 0.0662 | 0.9800 |

| 190 | 0.0708 | 0.9934 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhang, M.; Du, J.; Zheng, X.; Ma, A. The Preparation of ZnFe2O4 from Coal Gangue for Use as a Photocatalytic Reagent in the Purification of Dye Wastewater via the PMS Reaction. Materials 2026, 19, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010169

Zhang M, Du J, Zheng X, Ma A. The Preparation of ZnFe2O4 from Coal Gangue for Use as a Photocatalytic Reagent in the Purification of Dye Wastewater via the PMS Reaction. Materials. 2026; 19(1):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010169

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Mingxian, Jinsong Du, Xuemei Zheng, and Aiyuan Ma. 2026. "The Preparation of ZnFe2O4 from Coal Gangue for Use as a Photocatalytic Reagent in the Purification of Dye Wastewater via the PMS Reaction" Materials 19, no. 1: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010169

APA StyleZhang, M., Du, J., Zheng, X., & Ma, A. (2026). The Preparation of ZnFe2O4 from Coal Gangue for Use as a Photocatalytic Reagent in the Purification of Dye Wastewater via the PMS Reaction. Materials, 19(1), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010169