Oil Sorption Capacity of Recycled Polyurethane Foams and Their Mechanically Milled Powders

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

3. Results and Discussion

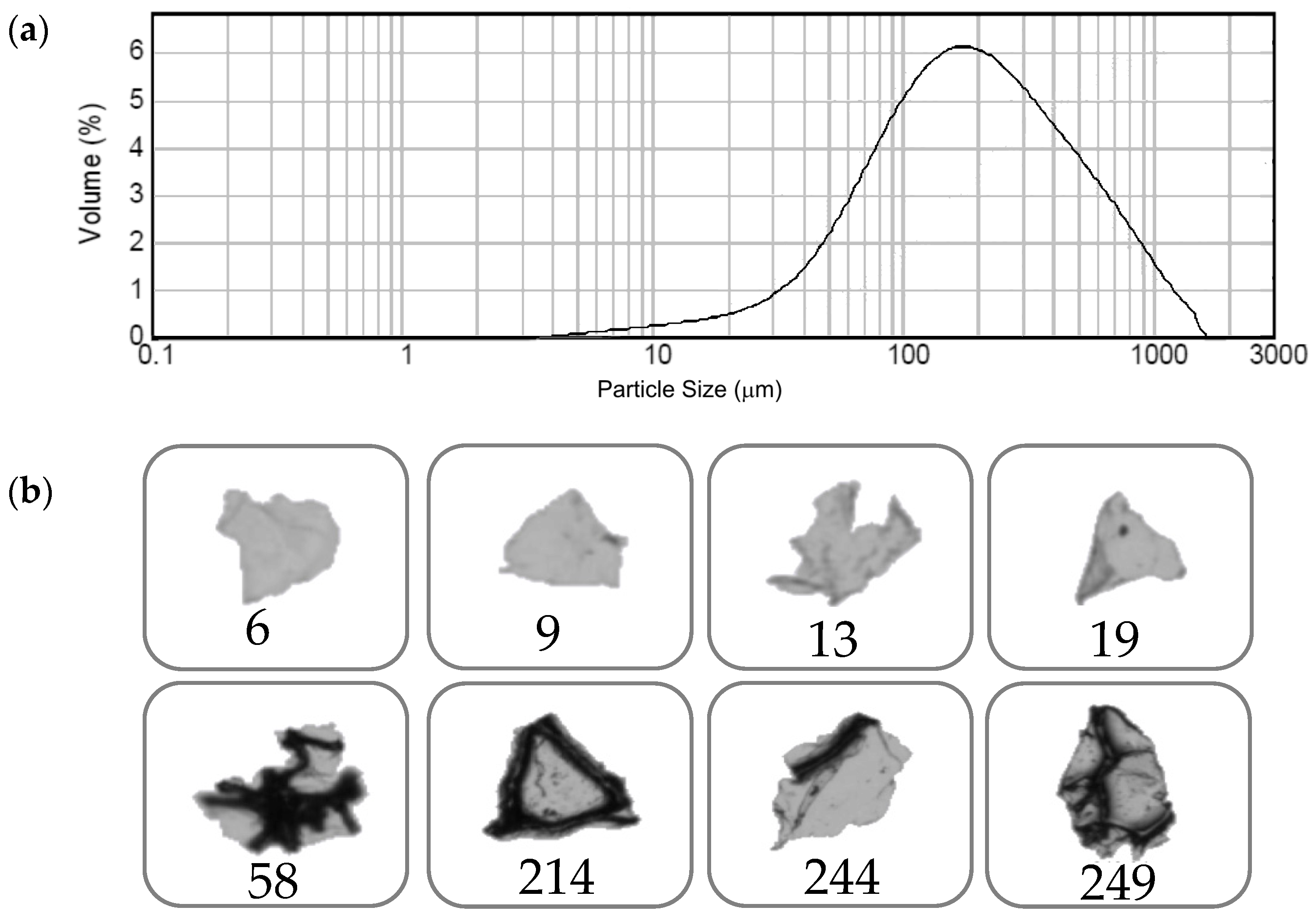

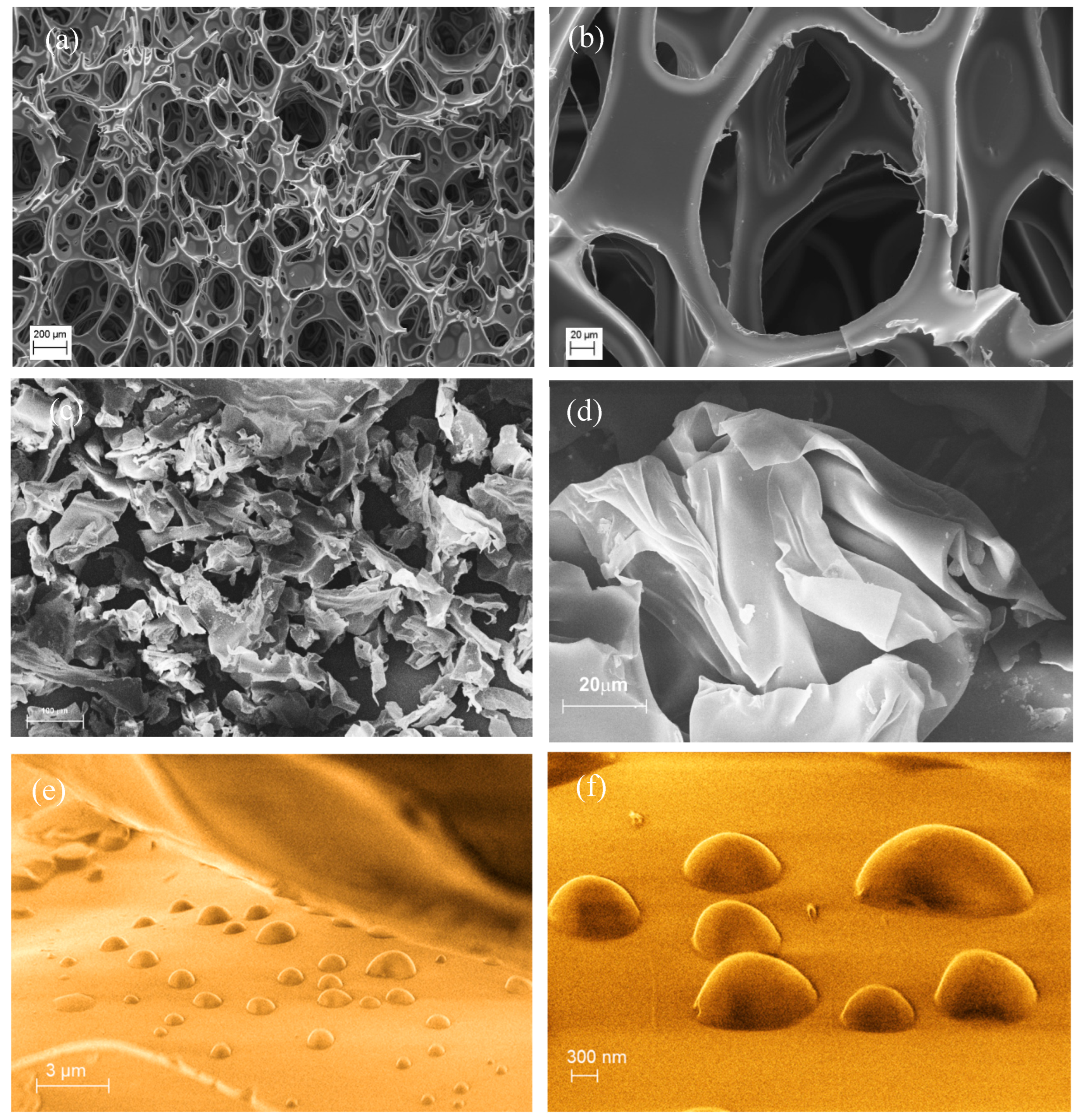

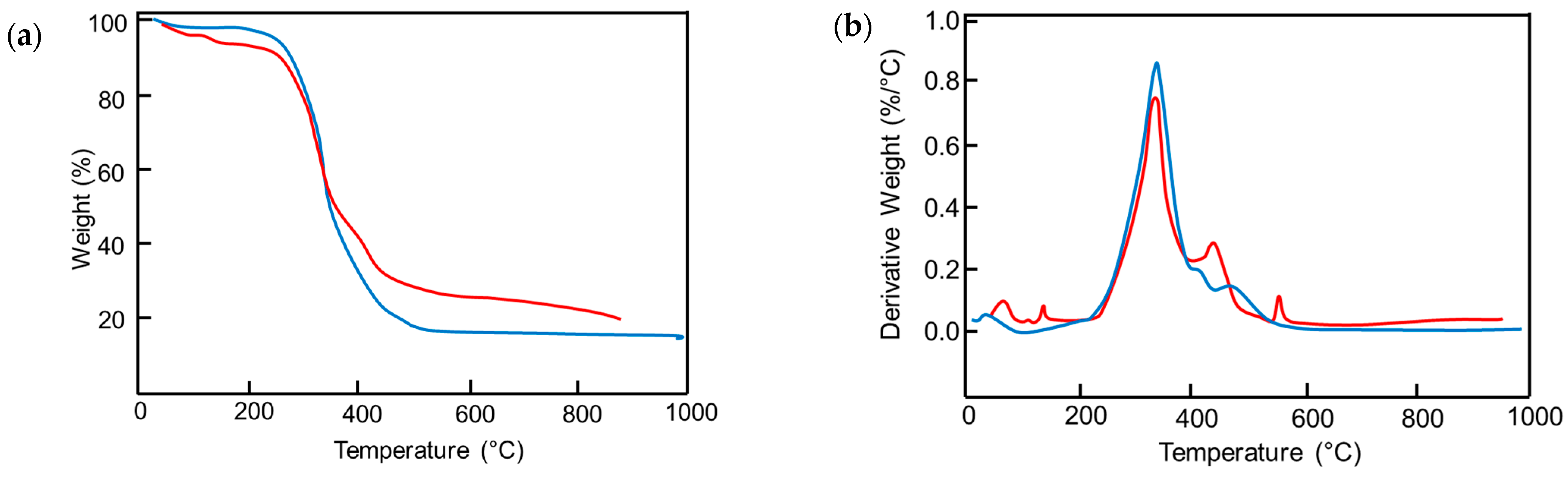

3.1. Recycle of Dismantled PU Foams and Mechanical Treatment by Blade-Milling Process: Analysis of Size, Morphology, and Chemico-Physical Properties

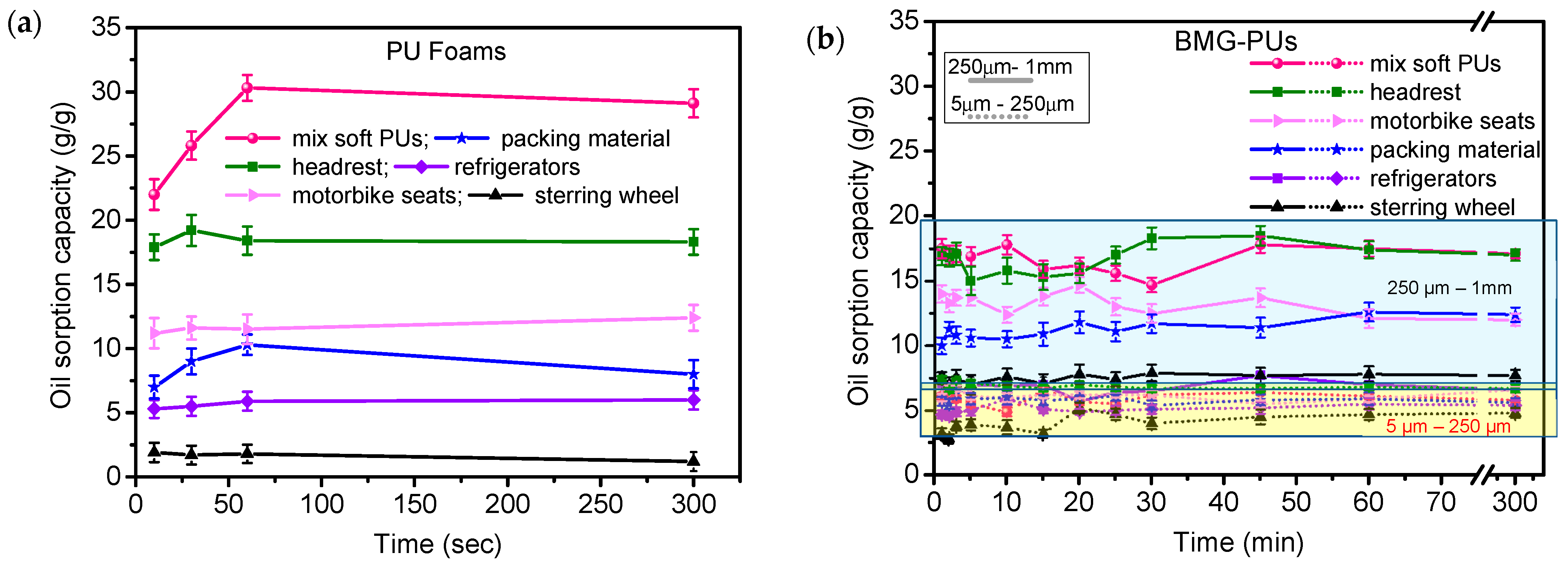

3.2. Oil Sorption Capacity of PU Foams and Powder

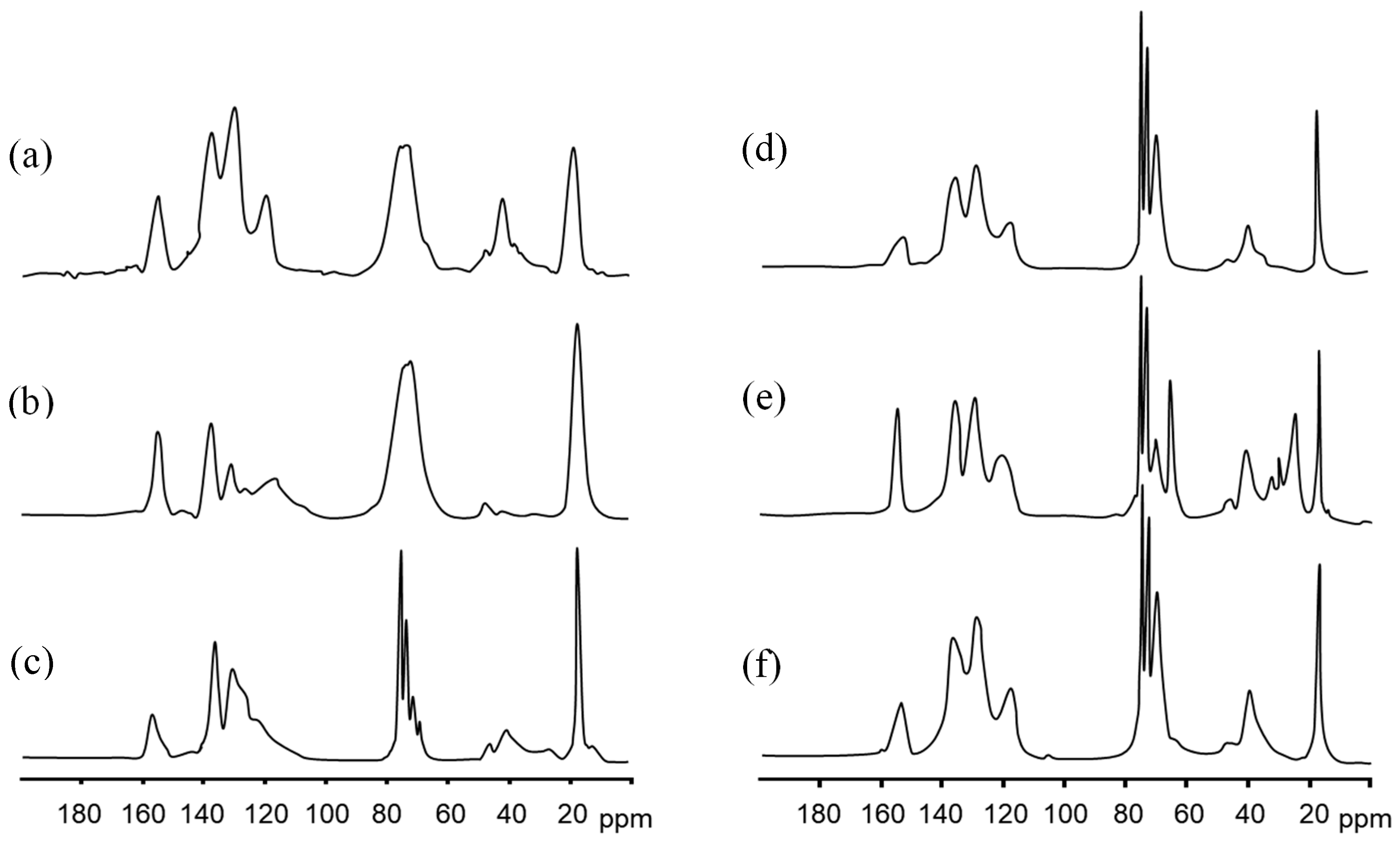

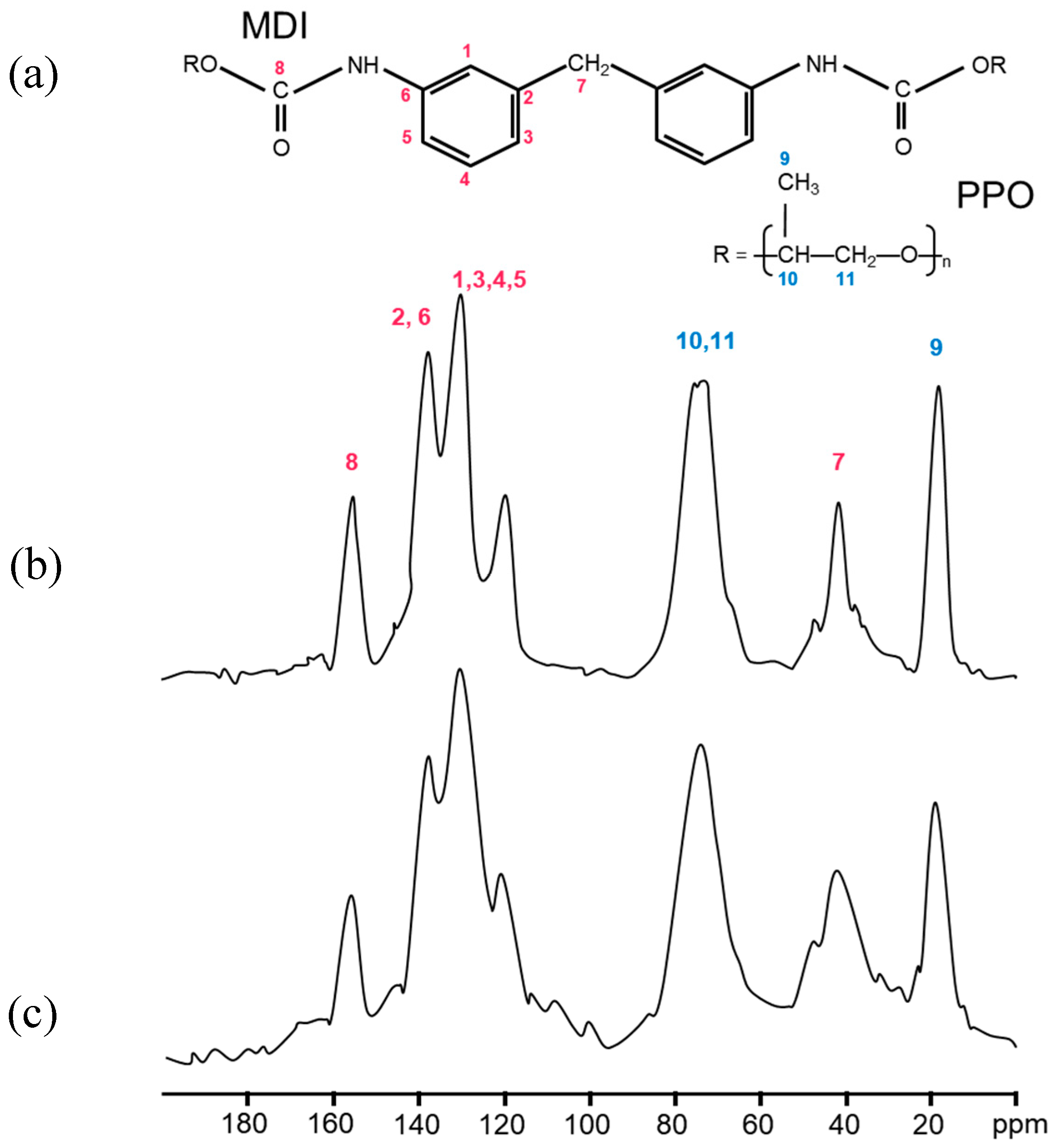

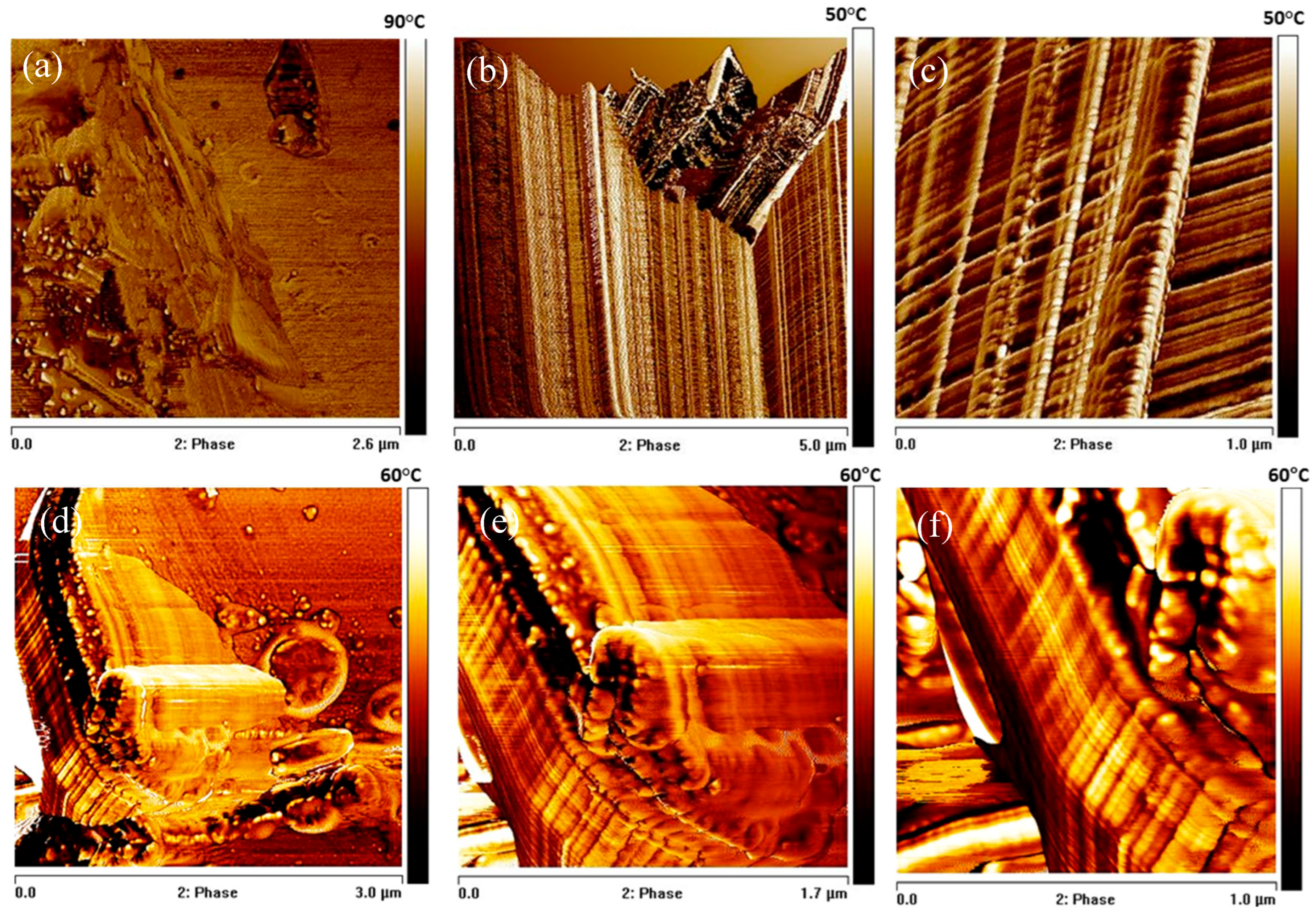

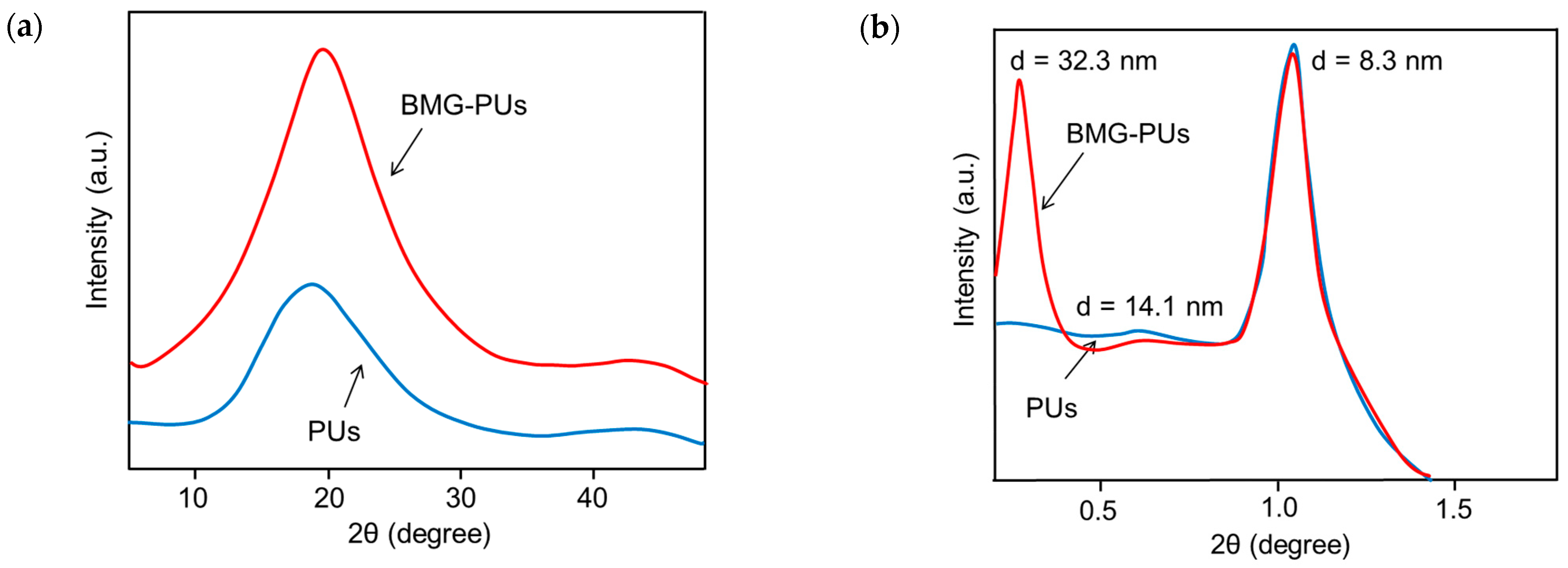

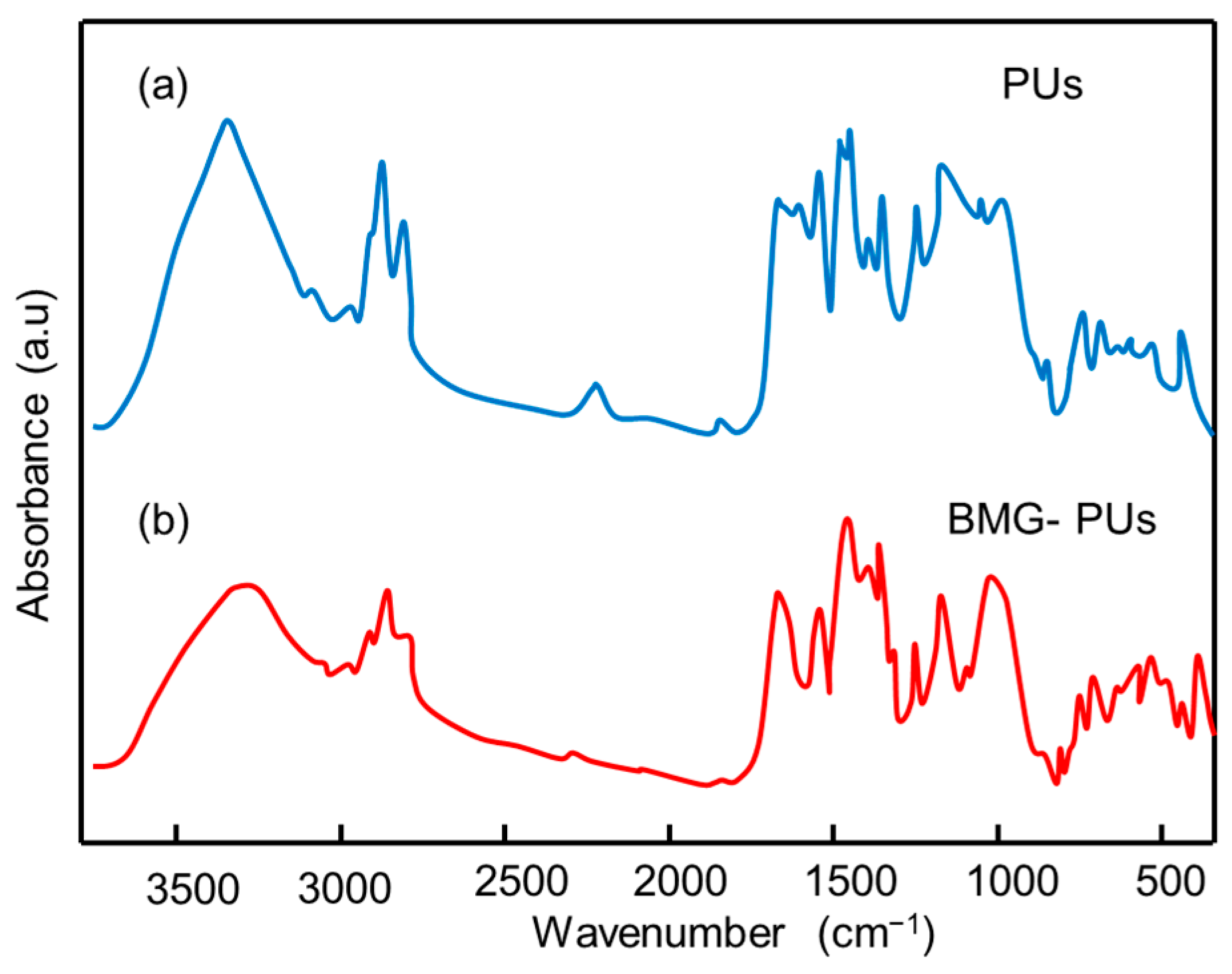

3.3. Analysis of Structural, Chemico-Physical Changes Induced by Mechanical Treatment

3.4. Morphological, Structural, and Chemico-Physical Changes Induced by the Grinding Process

3.5. Oil Sorption Mechanism of PU Foam and BMG-PU Powder

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Akindoyo, J.O.; Beg, M.D.H.; Ghazali, S.; Islam, M.R.; Jeyaratnam, N.; Yuvaraj, A.R. Polyurethane types, synthesis and applications—A review. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 114453–114482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, P. Synthesis methods, chemical structures and phase structures of linear polyurethanes. Properties and applications of linear polyurethanes in polyurethane elastomers, copolymers and ionomers. Prog. Mater Sci. 2007, 52, 915–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurichesse, S.; Avérous, L. Chemical modification of lignins: Towards biobased polymers. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2014, 39, 1266–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, M.; Karadag, S.; Ekerc, A.A.; Ekerd, B. Polyurethane foam materials and their industrial applications. Polym. Int. 2022, 71, 1157–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szycher, M. Szycher’s Handbook of Polyurethanes, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Ma, S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, C. A comprehensive review of polyurethane: Properties, applications and future perspectives. Polymer 2025, 327, 128361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.L.; Gupta, R.K. Polyurethanes: An Introduction. In Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes: Chemistry, Progress, and Challenges; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2025; Volume 1507, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, M.L.; Patel, R.; Gupta, R.K. Beyond isocyanates: Advances in non-isocyanate polyurethane chemistry and applications. Polymer 2025, 332, 128553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maamoun, A.A.; Arafa, M.; Esawi, A.M.K. Flexible polyurethane foam: Materials, synthesis, recycling, and applications in energy harvesting—A review. Mater. Adv. 2025, 6, 1842–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, J.; Zhao, H.; Luan, S.; Wang, L.; Shi, H. Recent advances in functional polyurethane elastomers: From structural design to biomedical applications. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 2526–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayalath, P.; Ananthakrishnan, K.; Jeong, S.; Shibu, R.P.; Zhang, M.; Kumar, D.; Yoo, C.G.; Shamshina, J.L.; Therasme, O. Bio-Based Polyurethane Materials: Technical, Environmental, and Economic Insights. Processes 2025, 13, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignolo, G.; Malucelli, G.; Lorenzetti, A. Recycling of polyurethanes: Where we are and where we are going. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Dong, Q.; Liu, S.; Xie, H.; Liu, L.; Li, J. Recycling and Disposal Methods for Polyurethane Foam Wastes. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2012, 16, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, J.; Głowińska, E.; Włoch, M. Mechanical Recycling via Regrinding, Rebonding, Adhesive Pressing, and Molding, in Recycling of Polyurethane Foams; Sabu, T., Rane, A.V., Krishnan, K., Abitha, V.K., Martin, G.T., Eds.; William Andrew Publishing: Norwich, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Nafziger, J.L.; Lowenkron, S.B.; Koehler, C.E.; Stevens, B.N. Flexible Polyurethane Rebond Foam Having Improved Tear Resistance and Methodfor the Preparation Thereof. U.S. Patent 5312888, 17 May 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Santucci, V.; Fiore, S. Recovery of Waste Polyurethane from E-Waste—Part I: Investigation of the Oil Sorption Potential. Materials 2021, 14, 6230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Chen, G.; Chang, B.P.; Mekonnen, T.H. Recent progress in the development of porous polymeric materials for oil ad/absorption application. RSC Appl. Polym. 2025, 3, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Folly d’Auris, A.; Rubertelli, F.; Taini, A.; Vocciante, M. A novel polyurethane-based sorbent material for oil spills management. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dacewicz, E.; Grzybowska-Pietras, J. Polyurethane Foams for Domestic Sewage Treatment. Materials 2021, 14, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, Q.; Cai, M.; Shi, Q.; Gao, J. Highly efficient reusable superhydrophobic sponge prepared by a facile, simple and cost effective biomimetic bonding method for oil absorption. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khalaf, A.A.; SAl-Lami, H.; Abbas, A.F. Flexible polyurethane foam with improved oleophilic and hydrophobic properties for oil spill cleaning. Pet. Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-D.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.-B.; He, Q. Evaluation of Hydrophobic Polyurethane Foam as Sorbent Material for Oil Spill Recovery. J. Macromol. Sci. Part A Pure Appl. Chem. 2014, 51, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomon, T.R.B.; Omisol, C.J.M.; Aguinid, B.J.M.; Sabulbero, K.X.L.; Alguno, A.C.; Malaluan, R.M.; Lubguban, A.A. A novel naturally superoleophilic coconut oil-based foam with inherent hydrophobic properties for oil and grease sorption. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Zhang, C.; Gnanasekar, P.; Xiao, P.; Luo, Q.; Li, S.; Qin, D.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Zhu, J.; et al. Mechanically robust, solar-driven, and degradable lignin-based polyurethane adsorbent for efficient crude oil spill remediation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 415, 128956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, J.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; Zheng, G.; Zhou, L.; Fu, P. Sustainable superhydrophobic lignin-based polyurethane foam: An innovative solution for oil pollutant adsorption. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 377–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calcagnile, P.; Fragouli, D.; Bayer, I.S.; Anyfantis, G.C.; Martiradonna, L.; Cozzoli, P.D.; Cingolani, R.; Athanassiou, A. Magnetically driven floating foams for the removal of oil contaminants from water. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 5413–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Yang, F. Oleophilic polyurethane foams for oil spill cleanup. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2013, 18, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Z.C.; Roslan, R.A.; Lau, W.J.; Gürsoy, M.; Karaman, M.; Jullok, N.; Ismail, A.F. A Green Approach to Modify Surface Properties of Polyurethane Foam for Enhanced Oil Absorption. Polymers 2020, 12, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivito, F.; Ilham, Z.; Wan-Mohtar, W.A.; Oza, A.I.; Procopio, G.A.; Nardi, M. Oil Spill Recovery of Petroleum-Derived Fuels Using a Bio-Based Flexible Polyurethane Foam. Polymers 2025, 17, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, S.; Zhang, K.; Wang, C.; Wang, G.; Wang, X.; Xia, L.; Xia, G.; Hua, C. The Influence of Enclosed Isocyanate Dosage on the Reaction Rate, Mechanical Properties and Grinding Performance of Polyurethane Grinding Wheels. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2025, 142, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szadkowska, K.; Kępczak, N.; Stachurski, W.; Pawłowski, W.; Rosik, R.; Bechciński, G.; Sikora, M.; Witkowski, B.; Sikorski, J. Influence of Machining Parameters on the Surface Roughness and Tool Wear During Slot Milling of a Polyurethane Block. Materials 2025, 18, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ASTM F726-17 (Reapproved 2024); Standard Test Method for Sorbent Performance of Adsorbents for use on Crude Oil and Related Spills. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Velankar, S.; Cooper, S.L. Microphase separation and rheological properties of polyurethane melts. 3. Effect of block length. Macromolecules 1998, 31, 9181–9192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilgör, I.; Yilgör, E.; Wilkes, G.L. Critical parameters in designing segmented polyurethanes and their effect on morphology and properties: A comprehensive review. Polymer 2015, 58, A1–A36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez-Amieva, Y.; Martín-Martínez, J.M. Understanding the Interactions between Soft Segments in Polyurethanes: Structural Synergies in Blends of Polyester and Polycarbonate Diol Polyols. Polymers 2023, 15, 4494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, I.d.A.A.; de Oliveira, A.P.P.; Bassetti, F.d.J.; Kloss, J.R.; Coral, L.A.d.A. Bio-based polyurethanes: A comprehensive review on advances in synthesis and functionalization. Polym. Int. 2025, 74, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganuma, K.; Matsuda, H.; Asakura, T. Characterization of polyurethane and a silk fibroin-polyurethane composite fiber studied with NMR spectroscopies. Polym. J. 2022, 54, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.X.; Gao, W.C.; Ren, X.M.; Ouyang, X.Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wu, W.; Huang, C.X.; Liu, Y.; Liu, X.Y.; et al. A review of microphase separation of polyurethane: Characterization and applications. Polym. Test. 2022, 107, 107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheth, J.P.; Wilkes, G.L.; Fornof, A.R.; Long, T.E.; Yilgor, I. Probing the Hard Segment Phase Connectivity and Percolation in Model Segmented Poly(urethane urea) Copolymers. Macromolecules 2005, 38, 5681–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, P.; Bagdi, K.; Molnár, K.; Markus, P.; Pukánszky, B.; Vancso, G.J. Quantitative mapping of elastic moduli at the nanoscale in phase separated polyurethanes by AFM. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, F.M.; Kahol, P.K.; Gupta, R.K. Introduction to Polyurethane Chemistry. In Polyurethane Chemistry: Renewable Polyols and Isocyanates; Gupta, R.K., Kahol, P.K., Eds.; ACS Symposium Series; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Volume 1, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovati, G.; Sanches, E.A.; Neto, S.C.; Mascarenhas, Y.P.; Chierice, G.O. Characterization of polyurethane resins by FTIR, TGA, and XRD. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2010, 115, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schemmer, B.; Kronenbitter, C.; Mecking, S. Thermoplastic Polyurethane Elastomers with Aliphatic Hard Segments Based on Plant-Oil-Derived Long-Chain Diisocyanates. Macromol. Mater Eng. 2018, 303, 1700416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, R.C.M.; Góes, A.M.; Serakides, R.; Ayres, E.; Oréfice, R.L. Porous Biodegradable Polyurethane Nanocomposites: Preparation, Characterization, and Biocompatibility Tests. Mater. Res. 2010, 13, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laity, P.R.; Taylor, J.E.; Wong, S.S.; Khunkamchoo, P.; Norris, K.; Cable, M.; Andrews, G.T.; Johnson, A.F.; Cameron, R.E. A 2-dimensional small-angle X-ray scattering study of the microphase-separated morphology exhibited by thermoplastic polyurethanes and its response to deformation. Polymer 2004, 45, 5215–5232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.P.; Dai, S.A.; Chang, H.L.; Su, W.C.; Wu, T.M.; Jeng, R.J. Polyurethane elastomers through multi-hydrogen-bonded association of dendritic structures. Polymer 2005, 46, 11849–11857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.T.; Lin, L.H. Waterborne Polyurethane/Clay Nanocomposites: Novel Effects of the Clay and Its Interlayer Ions on the Morphology and Physical and Electrical Properties. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 6133-6141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanzione, M.; Russo, V.; Oliviero, M.; Verdolotti, L.; Sorrentino, A.; Di Serio, M.; Tesser, R.; Iannace, S.; Lavorgna, M. Synthesis and characterization of sustainable polyurethane foams based on polyhydroxyls with different terminal groups. Polymer 2018, 149, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burelo, M.; Franco-Urquiza, E.A.; Martínez-Franco, E.; Moreno-Núñez, B.A.; Gómez, C.M.; Stringer, T.; Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D. Effect of Thermal Aging on Polyurethane Degradation and the Influence of Unsaturations in the Hard Segment. J. Polym. Sci. 2025, 63, 2639–2650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-B.; Cao, H.-B.; Zhang, Y. Thermal degradation kinetics of rigid polyurethane foams blown with water. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2006, 102, 4149–4156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-H.; Shen, M.-Y.; Kuan, C.-F.; Kuan, H.-C.; Ke, C.-Y.; Chiang, C.-L. Improving Thermal Stability of Polyurethane through the Addition of Hyperbranched Polysiloxane. Polymers 2019, 11, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cossari, P.; Caschera, D.; Plescia, P. Oil Sorption Capacity of Recycled Polyurethane Foams and Their Mechanically Milled Powders. Materials 2026, 19, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010166

Cossari P, Caschera D, Plescia P. Oil Sorption Capacity of Recycled Polyurethane Foams and Their Mechanically Milled Powders. Materials. 2026; 19(1):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010166

Chicago/Turabian StyleCossari, Pierluigi, Daniela Caschera, and Paolo Plescia. 2026. "Oil Sorption Capacity of Recycled Polyurethane Foams and Their Mechanically Milled Powders" Materials 19, no. 1: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010166

APA StyleCossari, P., Caschera, D., & Plescia, P. (2026). Oil Sorption Capacity of Recycled Polyurethane Foams and Their Mechanically Milled Powders. Materials, 19(1), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010166