Effect of Replacement of Ni by Ta on Glass-Forming Ability, Crystallization Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni Amorphous Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

3. Results and Discussion

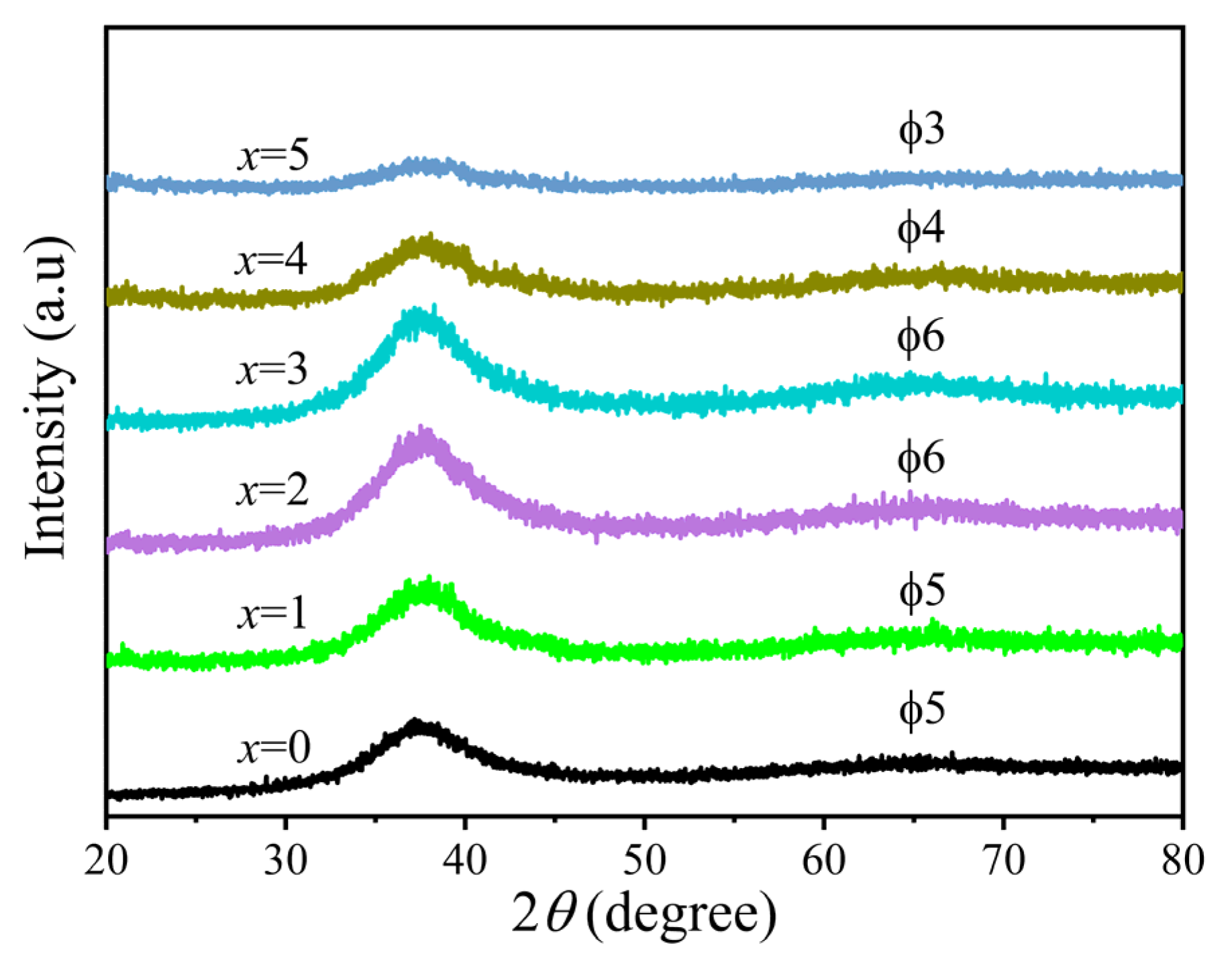

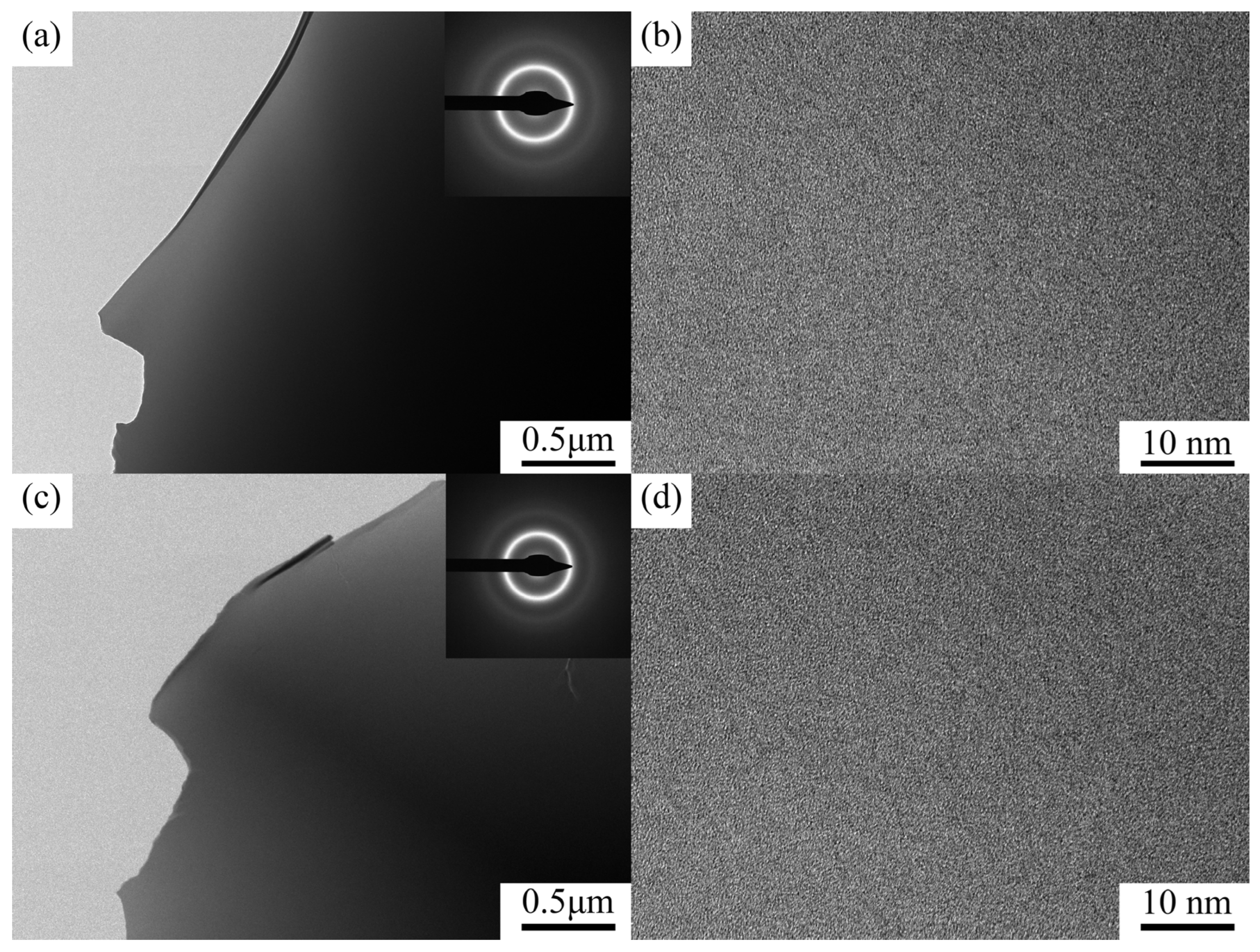

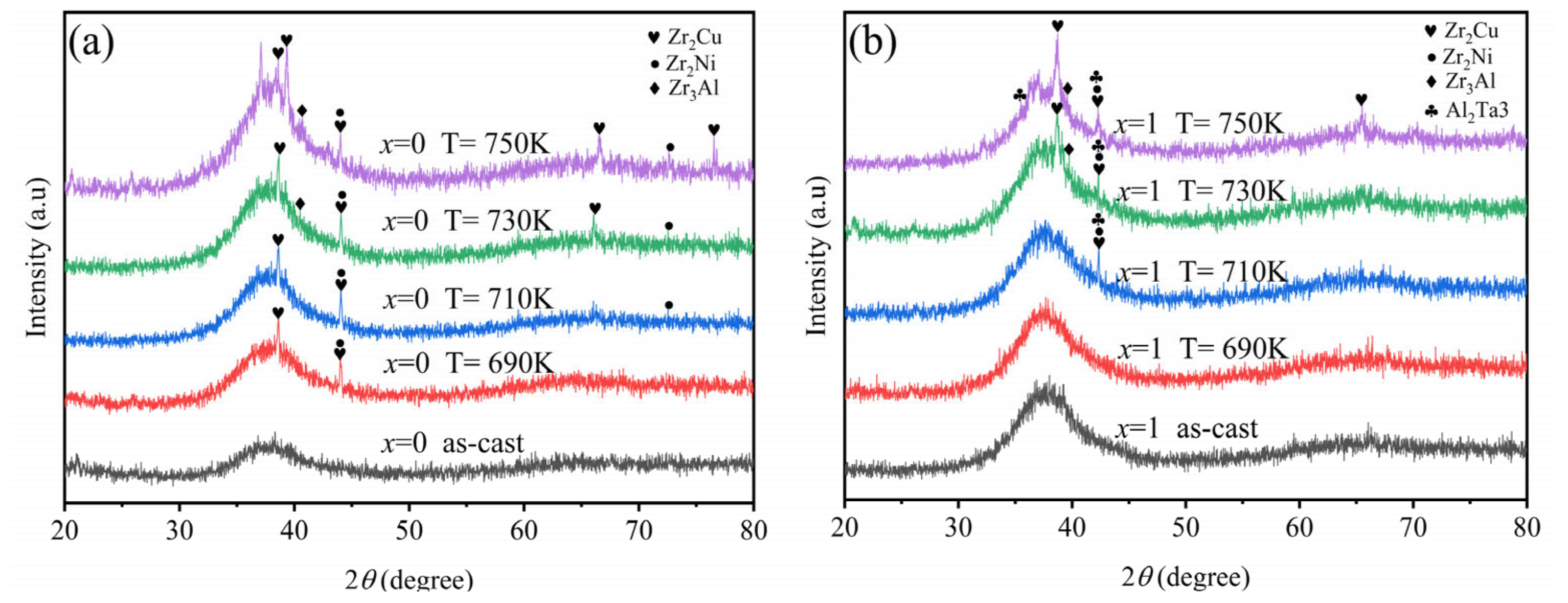

3.1. Microstructure

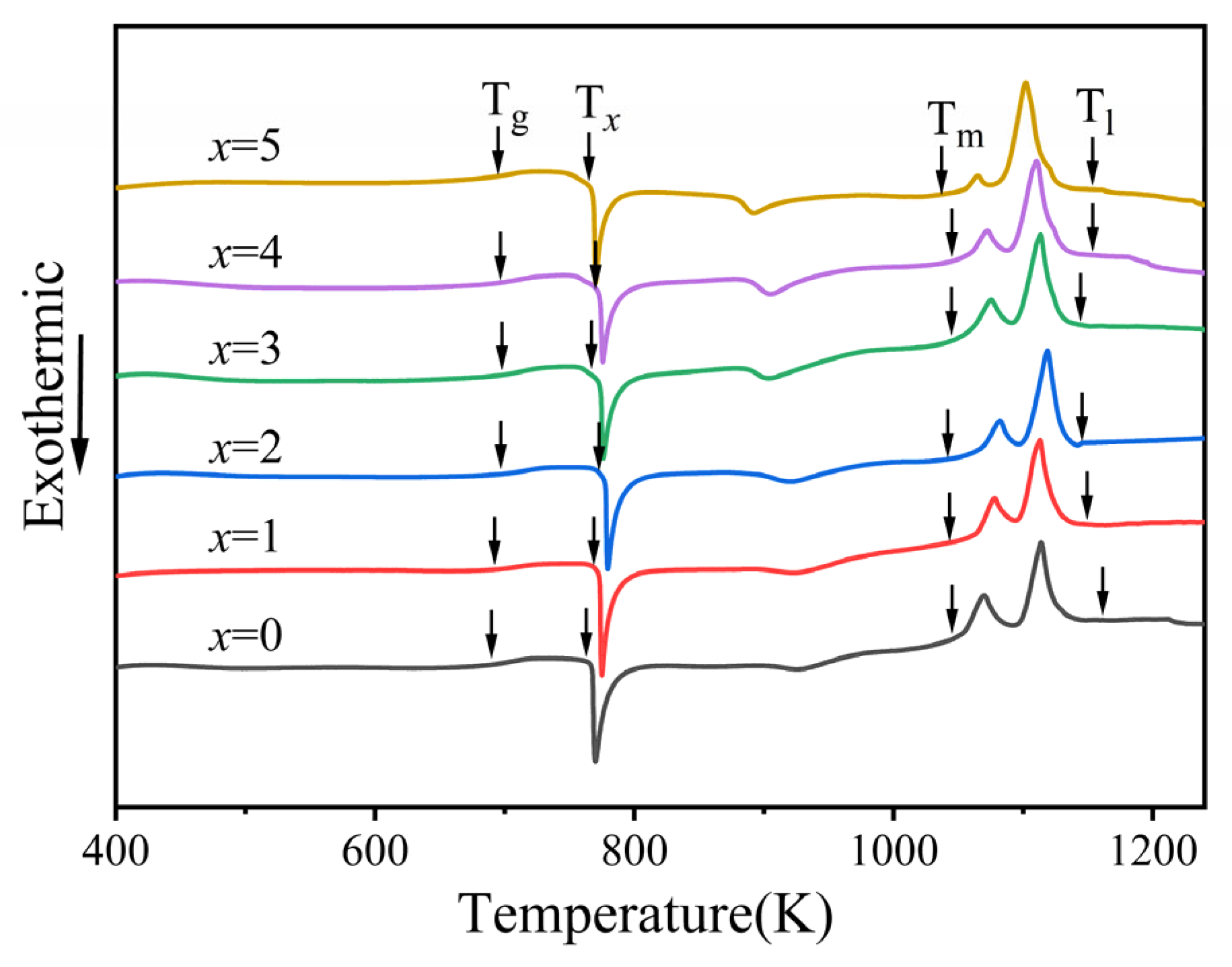

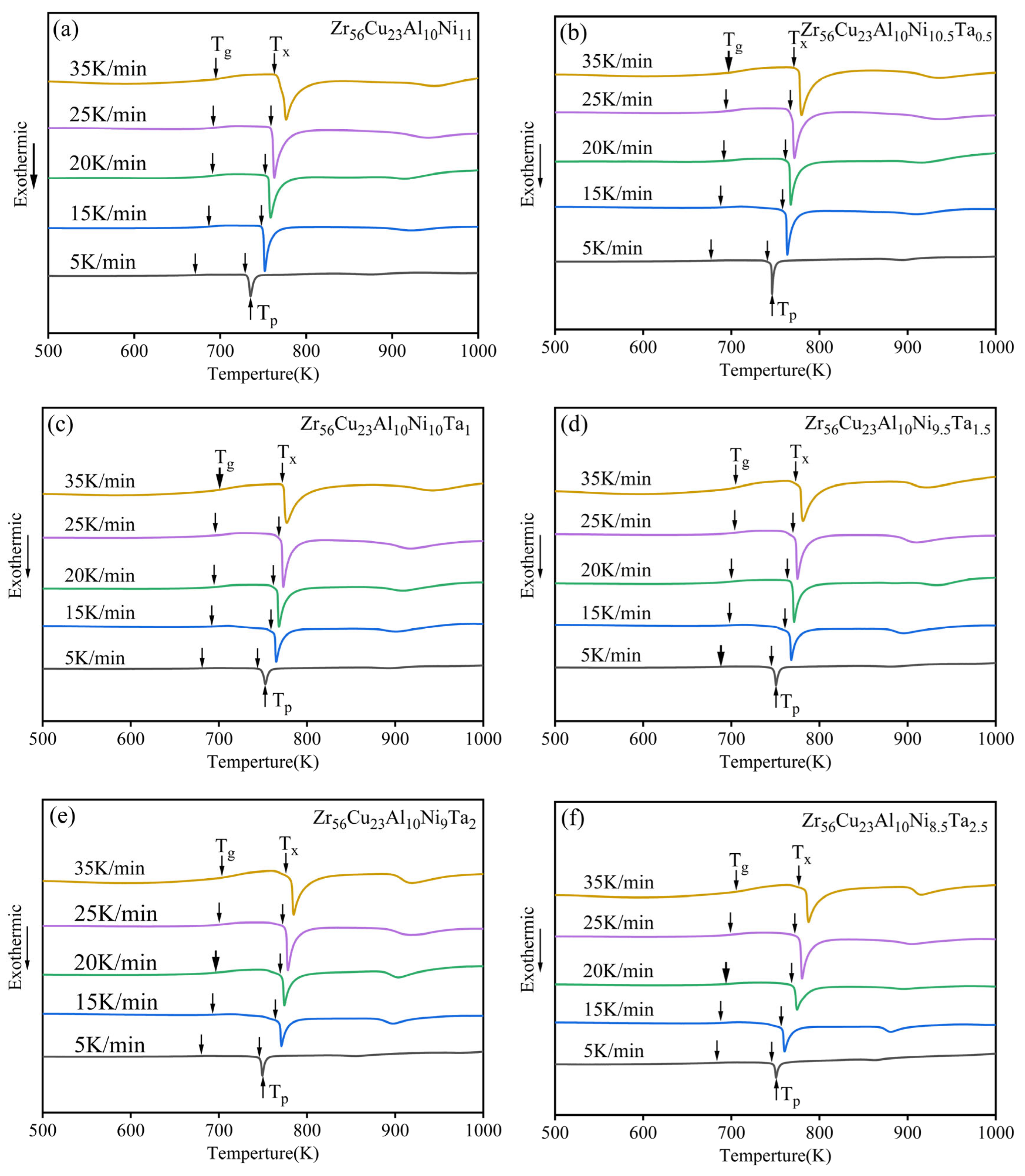

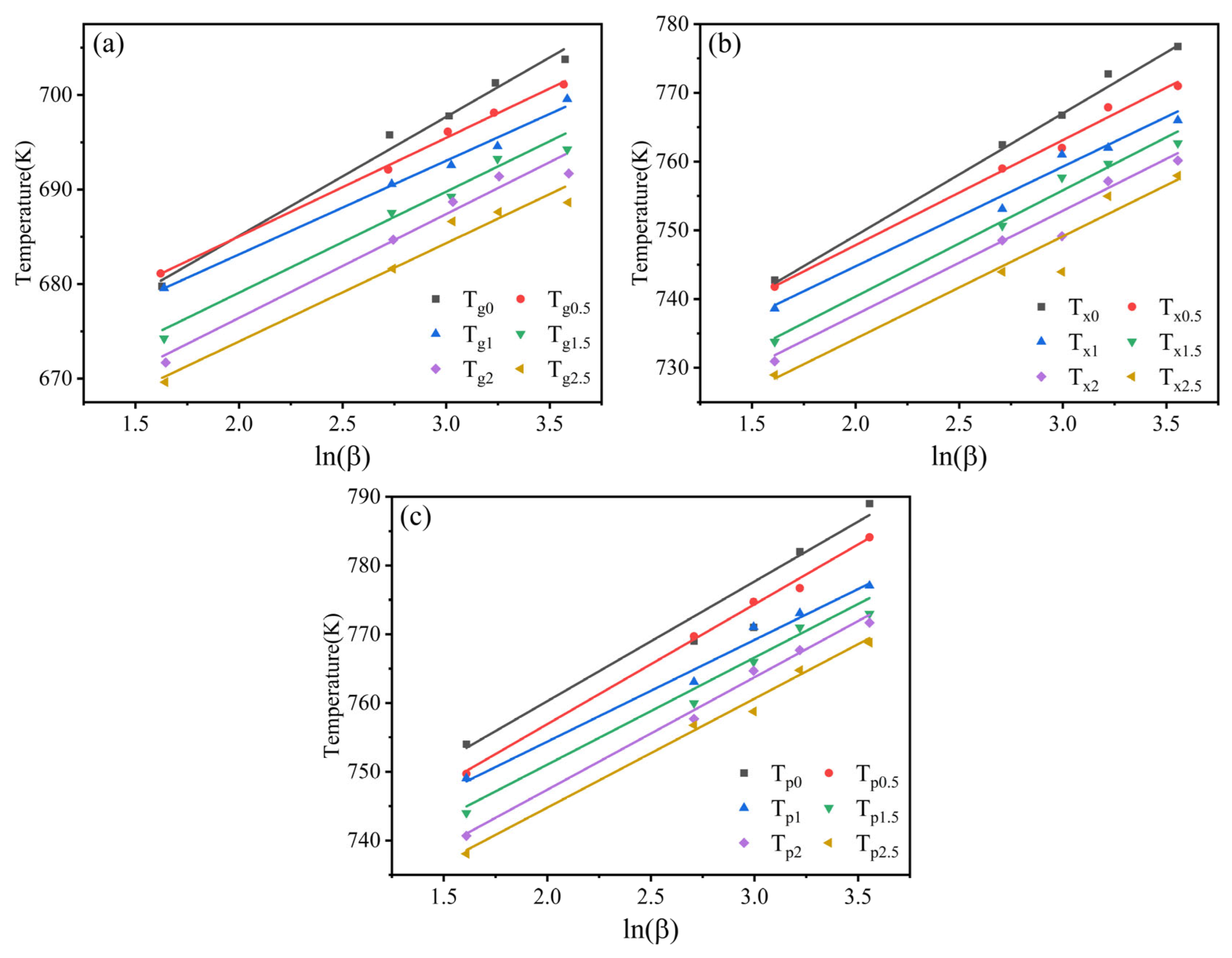

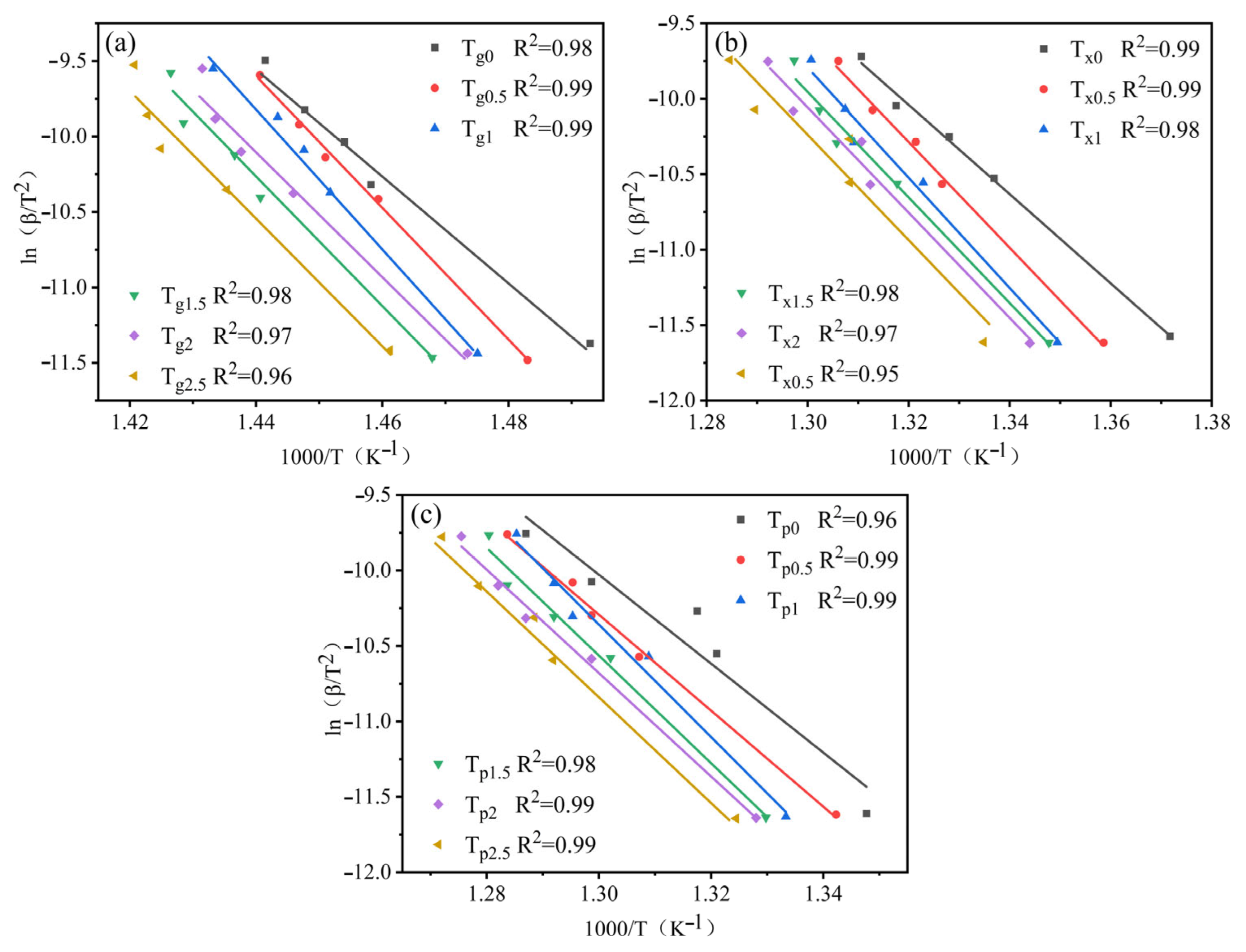

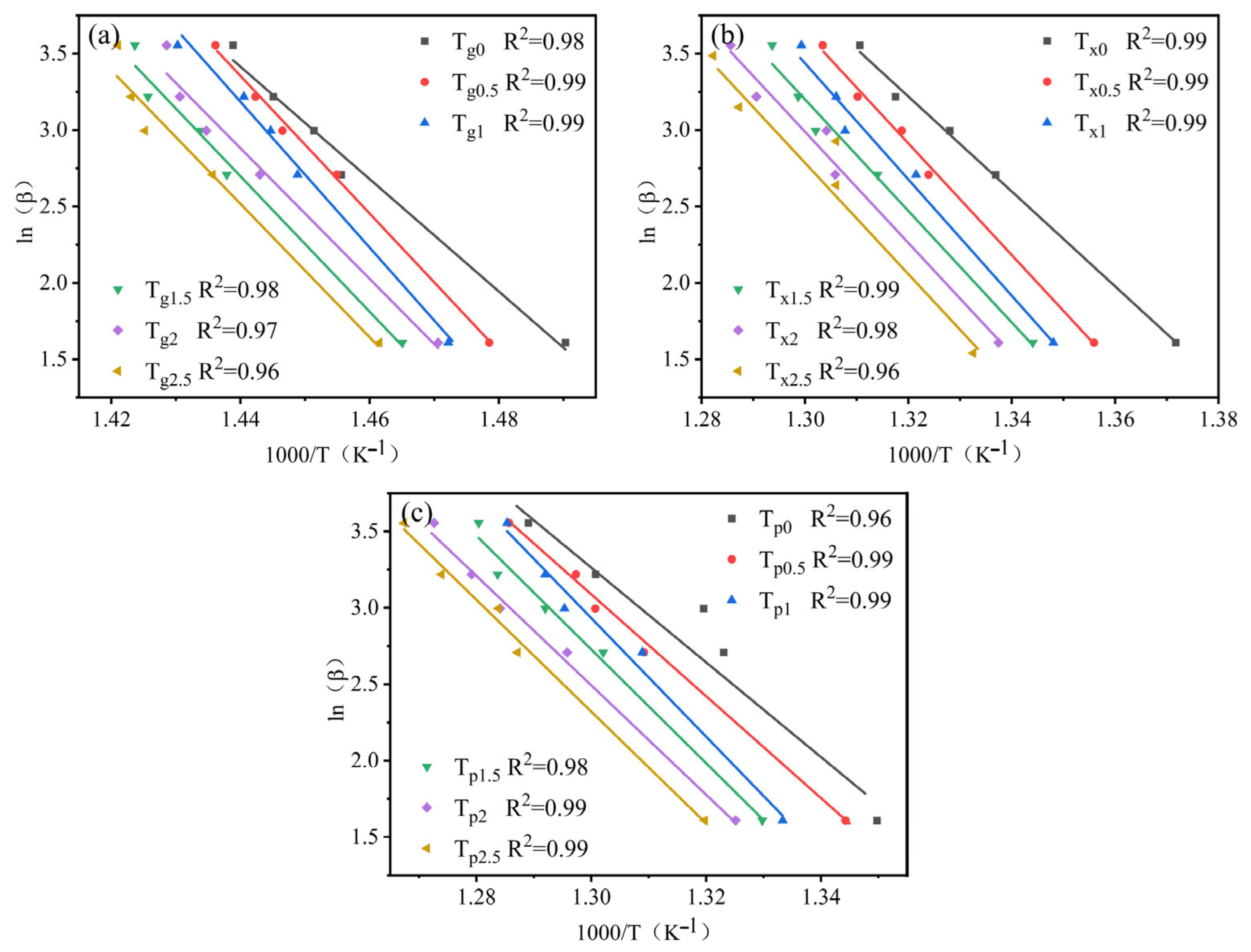

3.2. GFA and Crystallization Kinetics

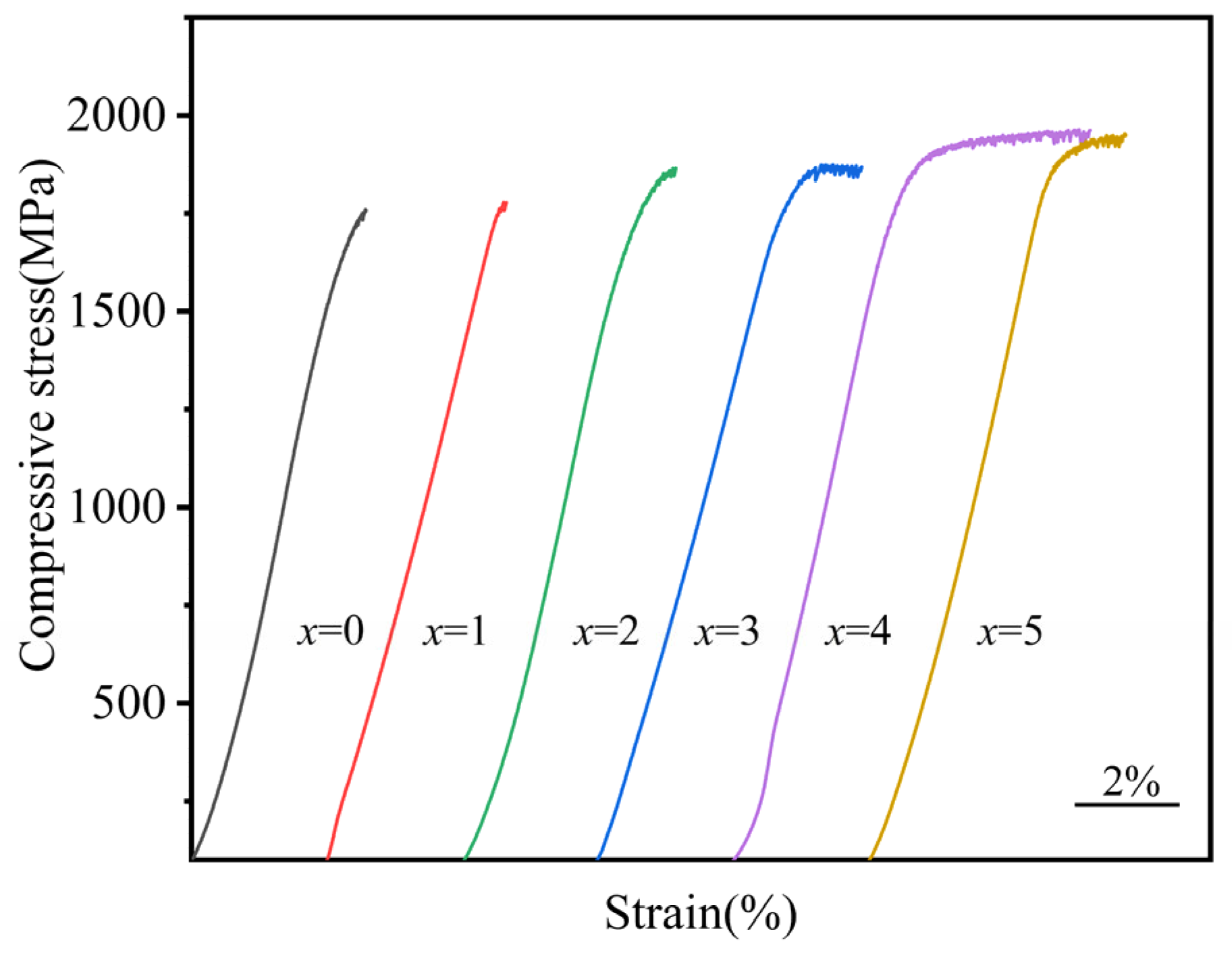

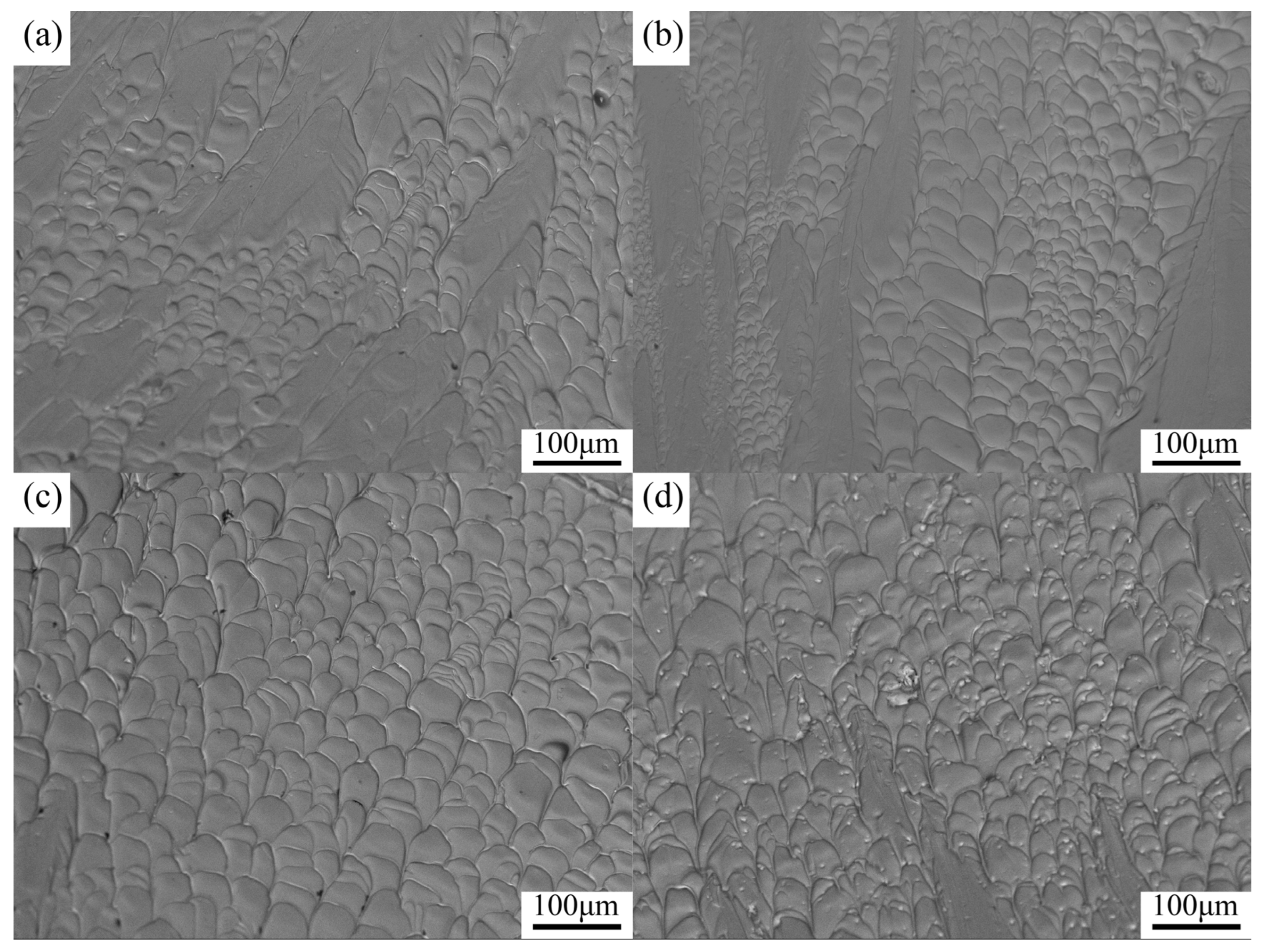

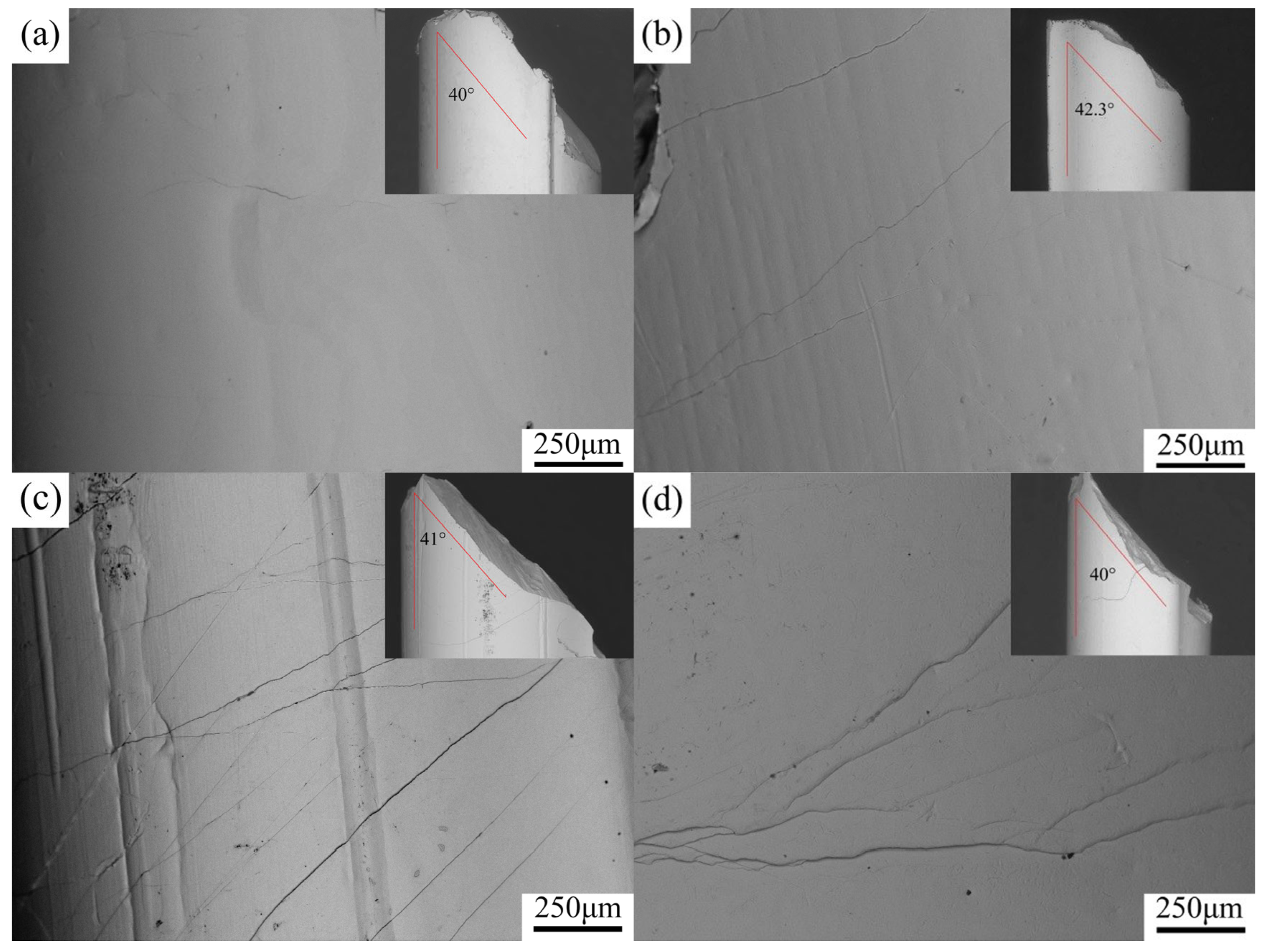

3.3. Mechanical Properties

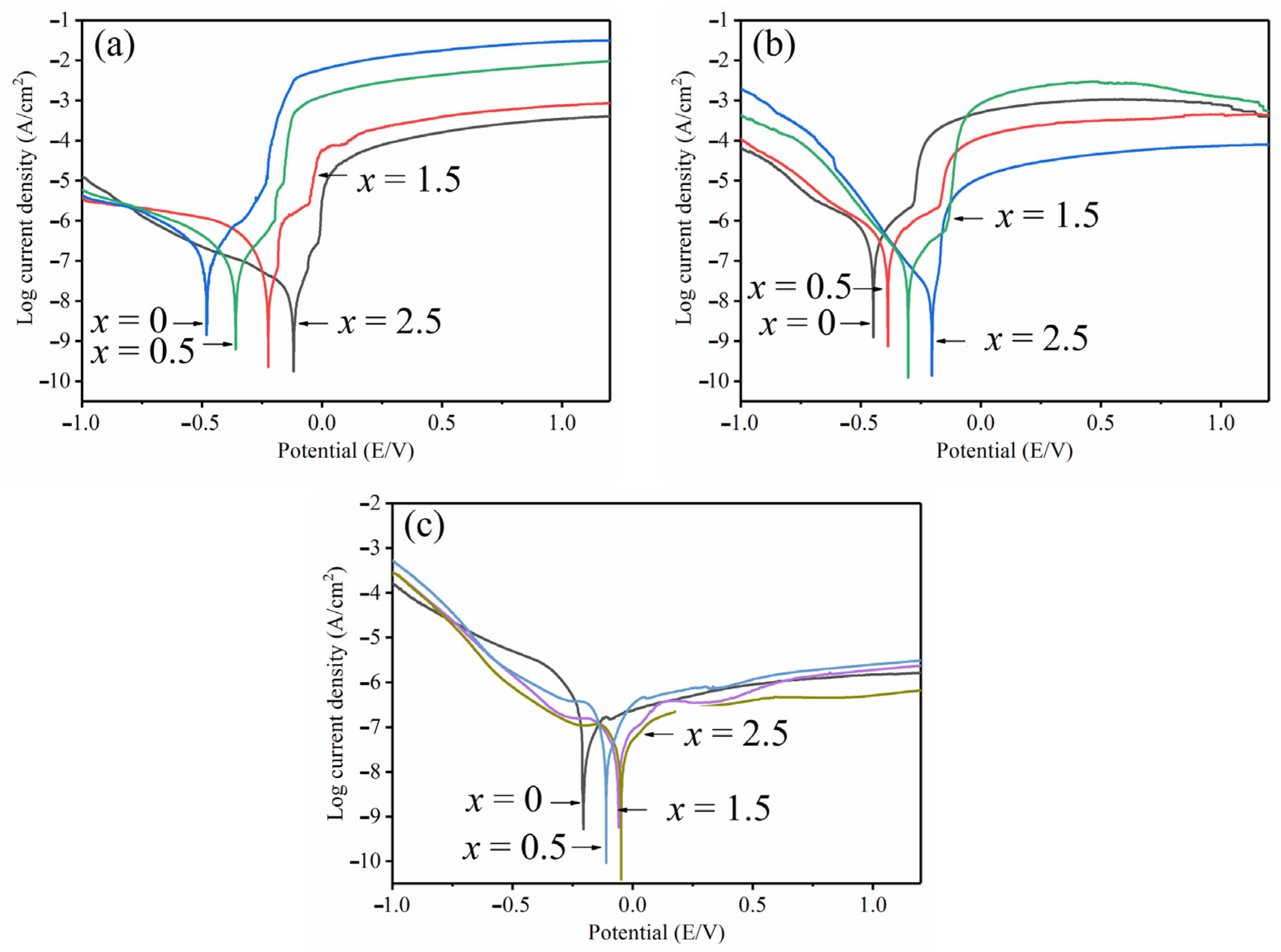

3.4. Corrosion Behavior

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- The addition of appropriate amounts of Ta improved the forming ability of the amorphous alloys. The critical dimension of Zr56Cu23Al10Ni9.5Ta1.5 amorphous alloy was determined as 6 mm. This alloy showed the highest amorphous forming ability, with 1 mm larger than the critical dimension of the original amorphous alloy. At x = 1.5, both Trg and γ of the amorphous alloys reached maximum values of 0.618 and 0.419, respectively. The subcooled liquid phase region also became larger.

- (2)

- The increment in Ta content led to an increasing trend followed by a decrease in the activation energy Eg, Ex, and Ep of the alloy systems. All values reached maxima at Ta content of 1 at.%. This showed larger energy barriers of the atomic rearrangement during glass transition, nucleation, and growth during crystallization of Zr56Cu23Al10Ni10Ta1. Hence, appropriate amounts of Ta for replacing Ni could significantly enhance the stability of alloy systems.

- (3)

- The fracture strength and compressive strain of Zr56Cu23Al10Ni11-xTax (x = 0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, and 2.5 at.%) amorphous alloys increased to some extent after the addition of Ta. At x = 2, the compressive strain and fracture strength of the amorphous alloy reached maximum values of 2.3% and 1962 MPa, respectively.

- (4)

- At x = 2.5, the highest corrosion potential in 1 mol/L HCl reached −278 mV, and the lowest corrosion current density was 7.9 × 10−8 A/cm2 (reduced by an order of magnitude when compared to original amorphous alloy). In 0.6 mol/L NaCl solution, the maximum corrosion potential was recorded as −142 mV, and the minimum corrosion current density was 6.3 × 10−8 A/cm2. Hence, obvious passivation took place in 1 mol/L H2SO4 solution with the lowest corrosion current density estimated to 2.5 × 10−8 A/cm2. Overall, the addition of Ta improved the corrosion resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni amorphous alloy.

- (5)

- Based on the findings of this study regarding the beneficial effects of Ta element on the properties of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni amorphous alloys, future research could systematically investigate the synergistic mechanisms of refractory metal elements such as Nb, Mo, and W on the glass-forming ability, mechanical properties, and corrosion resistance. This provides fundamental data for expanding the application of Zr-based bulk metallic glasses as key structural materials in marine equipment such as offshore platforms and ships.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, W.H.; Dong, C.; Shek, C.H. Bulk metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2004, 44, 45–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, A.; Inoue, A. Classification of Bulk Metallic Glasses by Atomic Size Difference, Heat of Mixing and Period of Constituent Elements and Its Application to Characterization of the Main Alloying Element. Mater. Trans. 2005, 46, 2817–2829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A. Stabilization of metallic supercooled liquid and bulk amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 279–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z.; Geng, H.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, P. Progress, Applications, and Challenges of Amorphous Alloys: A Critical Review. Inorganics 2024, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, B.; Xu, M.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Hao, R.; Fan, X.; Jia, B.; She, D. Unlocking single-atom catalysts via amorphous substrates. Nano Res. 2023, 17, 3533–3546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantavisut, S.; Lohwongwatana, B.; Khamkongkaeo, A.; Tanavalee, A.; Tangpornprasert, P.; Ittiravivong, P. The novel toxic free titanium-based amorphous alloy for biomedical application. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2018, 7, 248–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illeková, E.L.; Bartoš, J. On structural relaxation of Zr52Ni26Al22 metallic glass. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 1998, 235–237, 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Guo, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Chen, M.; Yamaura, S. Formation and properties of P-free Pd-based metallic glasses with high glass-forming ability. J. Alloys Compd. 2014, 617, 310–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, T.; Kurosaka, K. High-strength Cu-based bulk glassy alloys in Cu–Zr–Ti and Cu–Hf–Ti ternary systems. Acta Mater. 2001, 49, 2645–2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, V.; Ritchie, R.O. Stress-corrosion fatigue–crack growth in a Zr-based bulk amorphous metal. Acta Mater. 2006, 54, 1785–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Yin, D.; Lv, J.; Zhang, S.; Ma, M.; Zhang, X.; Liu, R. Effect on microstructure and plastic deformation behavior of a Zr-based amorphous alloy by cooling rate control. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 82, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-Y.; Yang, Y.-S.; Tong, W.-H.; Li, H.-Q.; Hu, Z.-Q. A new model for calculating critical cooling rates of alloy systems based on viscosity calculation. Acta Phys. Sin. 2007, 56, 1543–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xie, G.; Qin, F.; Wang, X.; Inoue, A. Ni- and Be-free Zr-based bulk metallic glasses with high glass-forming ability and unusual plasticity. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 13, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.; Zu, F.-Q.; Jiang, W.-X.; Wang, L.-F.; Wang, Z.-Z. Achieving superior glass forming ability of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni–Ti/Ag bulk metallic glasses by element substitution. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2013, 375, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.B.; Wang, X.D.; Xu, F.; Ding, S.Q.; Jiang, J.Z. 73 mm-diameter bulk metallic glass rod by copper mould casting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 051910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.G.; Sohn, K.-S.; Lee, S.; Kim, N.J.; Kim, C.P. In situ fracture observation and fracture toughness analysis of Zr-based bulk amorphous alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 464, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Liu, K.; Liu, G.; Zong, H.; Bala, H.; Zhang, B. Improving the glass-forming ability and the plasticity of Zr-Cu-Al bulk metallic glass by addition of Nb. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 513, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, G.; Zhang, Z.F.; Löser, W.; Eckert, J.; Schultz, L. Effect of Ta on glass formation, thermal stability and mechanical properties of a Zr52.25Cu28.5Ni4.75Al9.5Ta5 bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 2383–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.Q.; Li, Y.; Ramesh, K.T.; Li, J.; Hufnagel, T.C. Enhanced plastic strain in Zr-based bulk amorphous alloys. Phys. Rev. B 2001, 64, 180201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hufnagel, T.C.; Fan, C.; Ott, R.T.; Li, J.; Brennan, S. Controlling shear band behavior in metallic glasses through microstructural design. Intermetallics 2002, 10, 1163–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, J.S.C.; Jian, S.R.; Pan, D.J.; Wu, Y.H.; Huang, J.C.; Nieh, T.G. Thermal and mechanical characterizations of a Zr-based bulk metallic glass composite toughened by in-situ precipitated Ta-rich particles. Intermetallics 2010, 18, 560–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Inoue, A. Ta-particulate reinforced Zr-based bulk metallic glass matrix composite with tensile plasticity. Scr. Mater. 2010, 62, 278–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K.C.; Liu, L.; Pang, G.K.H. The microprocesses of the quasicrystalline transformation in Zr65Ni10Cu7.5Al7.5Ag10 bulk metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2004, 85, 2788–2790. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Z.; Wei, H.; Ding, Y.; Zhang, P.; Xie, G.; Inoue, A. A new criterion for predicting the glass-forming ability of bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 475, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.P.; Liu, C.T. A new glass-forming ability criterion for bulk metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 2002, 50, 3501–3512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Shen, J.; Zhang, D.; Fan, H.; Sun, J.; McCartney, D.G. A new criterion for evaluating the glass-forming ability of bulk metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2006, 433, 155–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.H.; Gao, Y.L.; Song, T.T.; Wang, G.; Zhai, Q.J. Non-isothermal crystallization kinetics of FeZrB amorphous alloy. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 522, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.S.S.K. Kinetics of Ge20Se80-xAsx(x= 0, 5, 10, 15 and 20) in glass transition region. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2003, 26, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.C.; Li, H.Y. Kinetics of non-isothermal crystallization in Cu50Zr43Al7 and (Cu50Zr43Al7)95Be5 metallic glasses. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 115, 1089–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Li, J.S.; Wang, J.; Kou, H.C.; Qiao, J.C.; Gravier, S.; Blandin, J.J. Crystallization kinetics of Cu38Zr46Ag8Al8 bulk metallic glass in different heating conditions. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2014, 404, 7–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.J.; Gu, X.J.; Wen, P.; Wang, L.B.; Lu, K. Pressure effect on the structural relaxation and glass transition in metallic glasses. Acta Mater. 2003, 51, 6219–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K. Reaction kinetics in differential thermal analysis. Anal. Chem. 1957, 29, 1417–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, T. Kinetic analysis of derivative curves in thermal analysis. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1970, 2, 301–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q.; Pan, Y.J.; Tan, J.; Qin, X.M.; Li, C.J.; Gao, P.; Feng, Z.X.; Calin, M.; Eckert, J. A comparative study of glass-forming ability, crystallization kinetics and mechanical properties of Zr55Co25Al20 and Zr52Co25Al23 bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 785, 422–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Sun, S.; Li, K.; Li, H.; Huang, X.; Tu, G. The effect of Y addition on the crystallization behaviors of Zr-Cu-Ni-Al bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 799, 501–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizhanova, G.; Li, F.; Ma, Y.; Gong, P.; Wang, X. Development and crystallization kinetics of novel near-equiatomic high-entropy bulk metallic glasses. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 779, 474–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chan, K.C.; Sun, M.; Chen, Q. The effect of the addition of Ta on the structure, crystallization and mechanical properties of Zr–Cu–Ni–Al–Ta bulk metallic glasses. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 445–446, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, A.C.; Schuh, C.A. The Mohr–Coulomb criterion from unit shear processes in metallic glass. Intermetallics 2004, 12, 1159–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuh, C.A.; Hufnagel, T.C.; Ramamurty, U. Mechanical behavior of amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 2007, 55, 4067–4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q.P.; Liu, J.W.; Yang, K.J.; Xu, F.; Yao, Z.Q.; Minkow, A.; Fecht, H.J.; Ivanisenko, J.; Chen, L.Y.; Wang, X.D.; et al. Effect of pre-existing shear bands on the tensile mechanical properties of a bulk metallic glass. Acta Mater. 2010, 58, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.X.; Chen, Y.F.; Wu, F.F.; Gong, J.M. Numerical study on deformation behavior of bulk metallic glass composites via modified free-volume theory. Intermetallics 2020, 119, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosiba, K.; Şopu, D.; Scudino, S.; Zhang, L.; Bednarcik, J.; Pauly, S. Modulating heterogeneity and plasticity in bulk metallic glasses: Role of interfaces on shear banding. Int. J. Plast. 2019, 119, 156–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.J.; Chen, G.L.; Hui, X.; Liu, T.; Lu, Z.P. Ordered clusters and free volume in a Zr–Ni metallic glass. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 93, 011911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-W.; Lee, C.-M.; Wakeda, M.; Shibutani, Y.; Falk, M.L.; Lee, J.-C. Elastostatically induced structural disordering in amorphous alloys. Acta Mater. 2008, 56, 5440–5450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miedema, A.R.; de Boer, F.R.; Boom, R. Model predictions for the enthalpy of formation of transition metal alloys. Calphad 1977, 1, 341–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.J.; Jin, Z.S.; Ma, X.Z.; Zhang, Z.P.; Zhong, H.; Ma, M.Z.; Zhang, X.Y.; Li, G.; Liu, R.P. Comparison of corrosion behaviors between Ti-based bulk metallic glasses and its composites. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 750, 757–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostin, P.F.; Sueptitz, R.; Gebert, A.; Kuehn, U.; Schultz, L. Comparing the corrosion behaviour of Zr66/Ti66–Nb13Cu8Ni6.8Al6.2 bulk nanostructure-dendrite composites. Intermetallics 2008, 16, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Dong, C.; Qin, C.; Qiang, J.; Makino, A.; Inoue, A. Enhancement of glass-forming ability and corrosion resistance of Zr-based Zr-Ni-Al bulk metallic glasses with minor addition of Nb. J. Appl. Phys. 2011, 110, 023513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Yu, L.; Qiao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H.; Duan, M.; Chamas, M. Effect of atomic mobility on the electrochemical properties of a Zr58Nb3Cu16Ni13Al10 bulk metallic glass. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 267, 222–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linder, C.; Mehta, B.; Sainis, S.; Lindén, J.B.; Zanella, C.; Nyborg, L. Corrosion resistance of additively manufactured aluminium alloys for marine applications. npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, C.L.; Liu, L.; Sun, M.; Zhang, S.M. The effect of Nb addition on mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, and metal-ion release of ZrAlCuNi bulk metallic glasses in artificial body fluid. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part A 2005, 75A, 950–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Content of Ta | Tg (K) | Tx (K) | Tm (K) | Tl (K) | ΔT (K) | Trg | γ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 689 | 753 | 1046 | 1151 | 64 | 0.598 | 0.409 |

| 0.5 | 692 | 762 | 1039 | 1142 | 70 | 0.605 | 0.415 |

| 1 | 694 | 767 | 1035 | 1140 | 73 | 0.608 | 0.418 |

| 1.5 | 700 | 768 | 1067 | 1131 | 68 | 0.618 | 0.419 |

| 2 | 697 | 765 | 1038 | 1144 | 68 | 0.609 | 0.415 |

| 2.5 | 693 | 760 | 1034 | 1145 | 67 | 0.605 | 0.413 |

| Content of Ta | β | Tg (K) | Tx (K) | Tp (K) | ΔT (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 5 | 671 | 729 | 742 | 58 |

| 15 | 687 | 748 | 757 | 61 | |

| 20 | 689 | 753 | 759 | 64 | |

| 25 | 692 | 759 | 770 | 67 | |

| 35 | 695 | 763 | 777 | 68 | |

| 0.5 | 5 | 677 | 741 | 745 | 64 |

| 15 | 688 | 759 | 765 | 71 | |

| 20 | 692 | 762 | 770 | 70 | |

| 25 | 694 | 767 | 772 | 73 | |

| 35 | 697 | 771 | 779 | 74 | |

| 1 | 5 | 681 | 744 | 750 | 63 |

| 15 | 692 | 759 | 764 | 67 | |

| 20 | 694 | 767 | 772 | 73 | |

| 25 | 696 | 768 | 774 | 72 | |

| 35 | 701 | 772 | 778 | 71 | |

| 1.5 | 5 | 685 | 744 | 752 | 59 |

| 15 | 698 | 761 | 768 | 63 | |

| 20 | 700 | 768 | 774 | 68 | |

| 25 | 704 | 770 | 779 | 66 | |

| 35 | 705 | 773 | 781 | 68 | |

| 2 | 5 | 680 | 746 | 753 | 66 |

| 15 | 693 | 764 | 770 | 71 | |

| 20 | 697 | 765 | 777 | 68 | |

| 25 | 699 | 773 | 780 | 74 | |

| 35 | 700 | 776 | 784 | 76 | |

| 2.5 | 5 | 676 | 745 | 754 | 69 |

| 15 | 688 | 760 | 773 | 72 | |

| 20 | 693 | 760 | 775 | 67 | |

| 25 | 694 | 771 | 781 | 77 | |

| 35 | 695 | 774 | 785 | 79 |

| Content of Ta | A/B | Tg | Tx | Tp |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | A | 651 | 700 | 712 |

| B | 12 | 17 | 17 | |

| 0.5 | A | 660 | 717 | 717 |

| B | 10 | 15 | 17 | |

| 1 | A | 665 | 721 | 726 |

| B | 10 | 14 | 15 | |

| 1.5 | A | 668 | 719 | 727 |

| B | 11 | 15 | 15 | |

| 2 | A | 663 | 722 | 726 |

| B | 11 | 15 | 16 | |

| 2.5 | A | 660 | 720 | 728 |

| B | 10 | 15 | 16 |

| Content of Ta (at.%) | Eg (kJ/mol) | Ex (kJ/mol) | Ep (kJ/mol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kissinger | Moynihan | Kissinger | Moynihan | Kissinger | Moynihan | |

| 0 | 294 | 305 | 245 | 257 | 244 | 256 |

| 0.5 | 362 | 374 | 295 | 303 | 264 | 276 |

| 1 | 384 | 396 | 303 | 315 | 309 | 321 |

| 1.5 | 356 | 368 | 290 | 302 | 295 | 308 |

| 2 | 343 | 355 | 289 | 301 | 284 | 296 |

| 2.5 | 351 | 362 | 289 | 301 | 290 | 303 |

| Content of Ta | σy (MPa) | σf (MPa) | εe (%) | εp (%) | E (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1760 ± 18 | 2.68 ± 0.1 | 0 | 92.6 ± 3 | |

| 0.5 | 1777 ± 16 | 2.85 ± 0.3 | 0 | 88.4 ± 2 | |

| 1 | 1834 ± 11 | 1864 ± 10 | 2.79 ± 0.2 | 0.49 ± 0.1 | 94.6 ± 4 |

| 1.5 | 1826 ± 13 | 1867 ± 20 | 3.08 ± 0.3 | 1.11 ± 0.3 | 86.4 ± 3 |

| 2 | 1900 ± 8 | 1962 ± 17 | 2.99 ± 0.4 | 2.61 ± 0.4 | 92.9 ± 1 |

| 2.5 | 1894 ± 6 | 1950 ± 15 | 3.06 ± 0.4 | 1.18 ± 0.2 | 89.9 ± 3 |

| Solutions | Aooly | Icorr (A/cm2) | Ecorr (mV) | Epit (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl | 0 | 2.7 × 10−7 | −493 | −241 |

| 0.5 | 1.8 × 10−7 | −368 | −203 | |

| 1.5 | 8.2 × 10−8 | −221 | −107 | |

| 2.5 | 6.3 × 10−8 | −142 | −67 | |

| HCl | 0 | 8.1 × 10−7 | −492 | −443 |

| 0.5 | 4.5 × 10−7 | −408 | −263 | |

| 1.5 | 1.3 × 10−7 | −322 | −108 | |

| 2.5 | 7.9 × 10−8 | −278 | −121 | |

| H2SO4 | 0 | 3.8 × 10−8 | −223 | |

| 0.5 | 3.4 × 10−8 | −137 | ||

| 1.5 | 2.8 × 10−8 | −86 | ||

| 2.5 | 2.5 × 10−8 | −79 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, W.; Ma, M.; Xiang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Z. Effect of Replacement of Ni by Ta on Glass-Forming Ability, Crystallization Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni Amorphous Alloys. Materials 2026, 19, 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010161

Sun W, Ma M, Xiang Z, Liu X, Li J, Yang Z, Chen Z. Effect of Replacement of Ni by Ta on Glass-Forming Ability, Crystallization Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni Amorphous Alloys. Materials. 2026; 19(1):161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010161

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Wenchao, Mingzhen Ma, Zhilei Xiang, Xing Liu, Jihao Li, Zian Yang, and Ziyong Chen. 2026. "Effect of Replacement of Ni by Ta on Glass-Forming Ability, Crystallization Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni Amorphous Alloys" Materials 19, no. 1: 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010161

APA StyleSun, W., Ma, M., Xiang, Z., Liu, X., Li, J., Yang, Z., & Chen, Z. (2026). Effect of Replacement of Ni by Ta on Glass-Forming Ability, Crystallization Kinetics, Mechanical Properties, and Corrosion Resistance of Zr–Cu–Al–Ni Amorphous Alloys. Materials, 19(1), 161. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010161