Effects of Direct Fluorination on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Preparation and Fluorination Treatment

2.2. Isothermal High-Temperature Oxidation Tests

2.3. Material Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

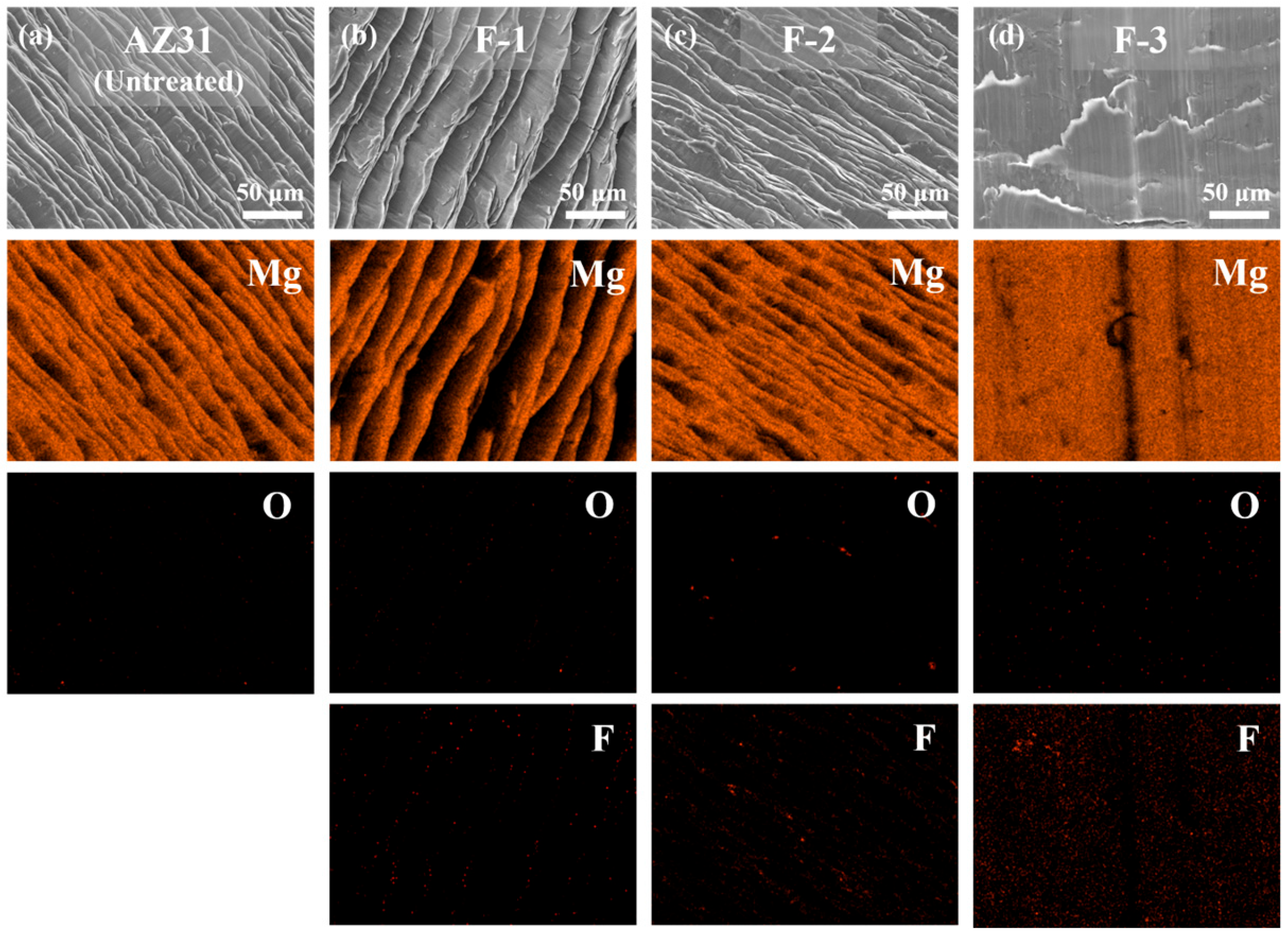

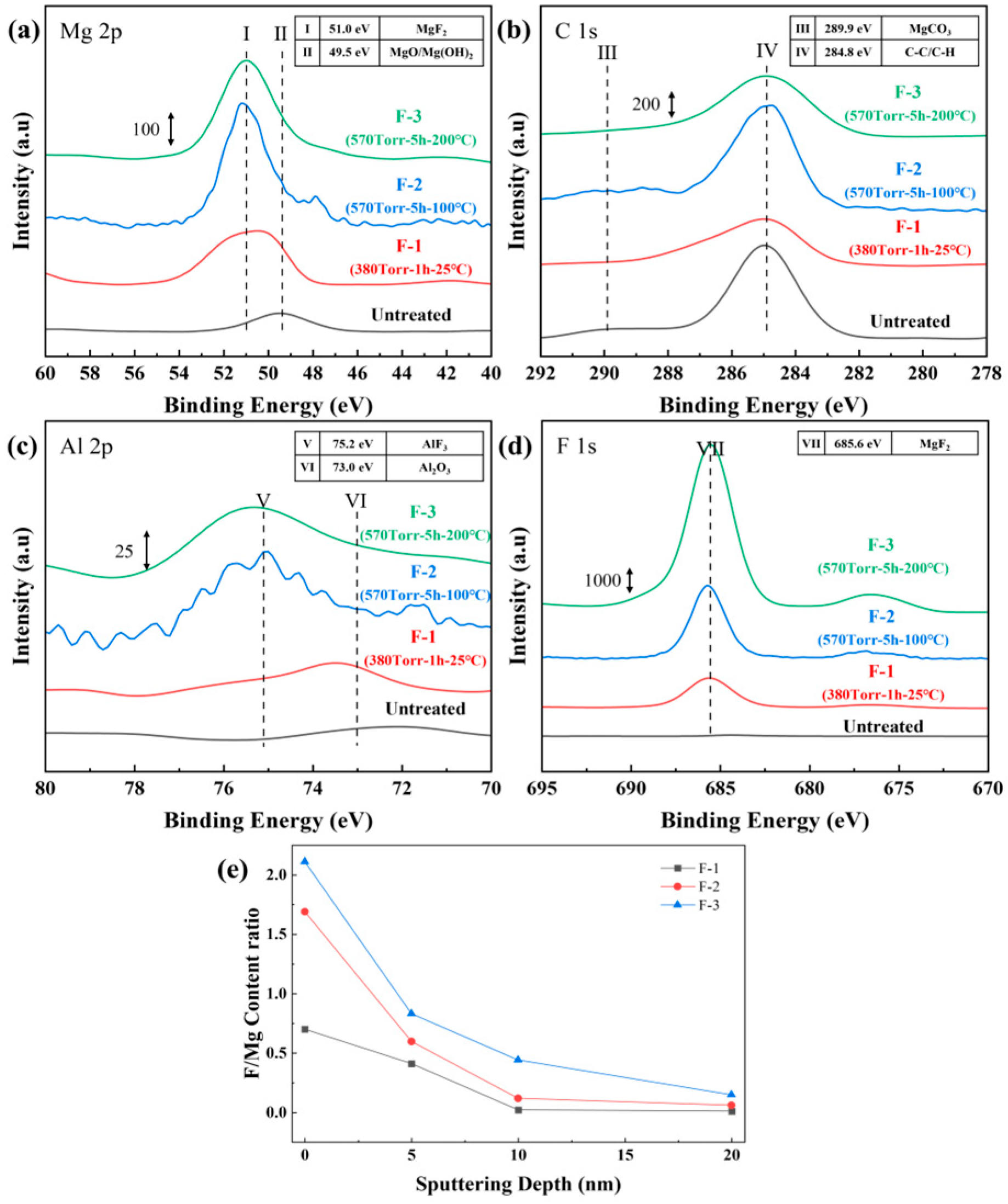

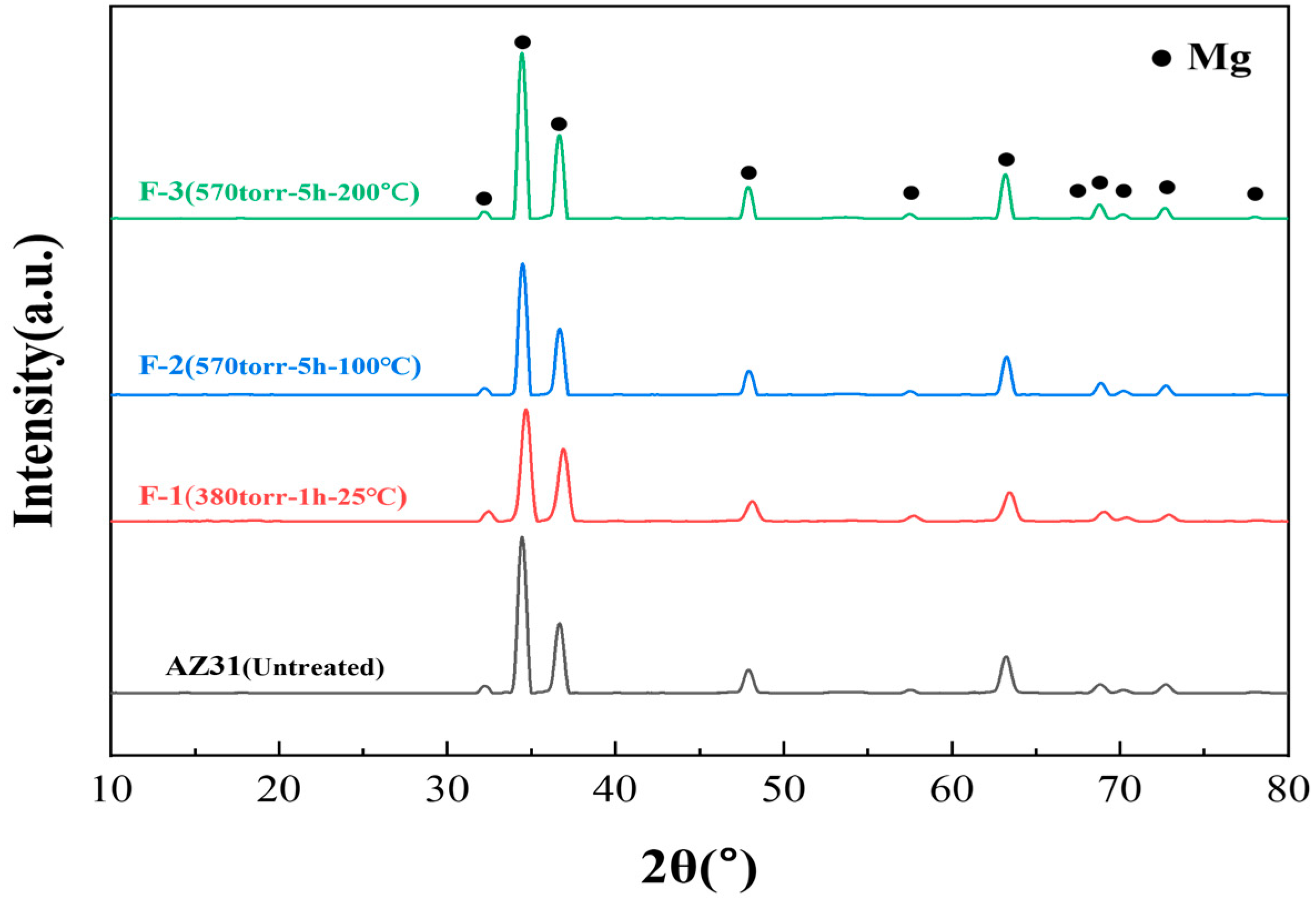

3.1. Fluorination Treatment Experiment of AZ31 Machining Chips

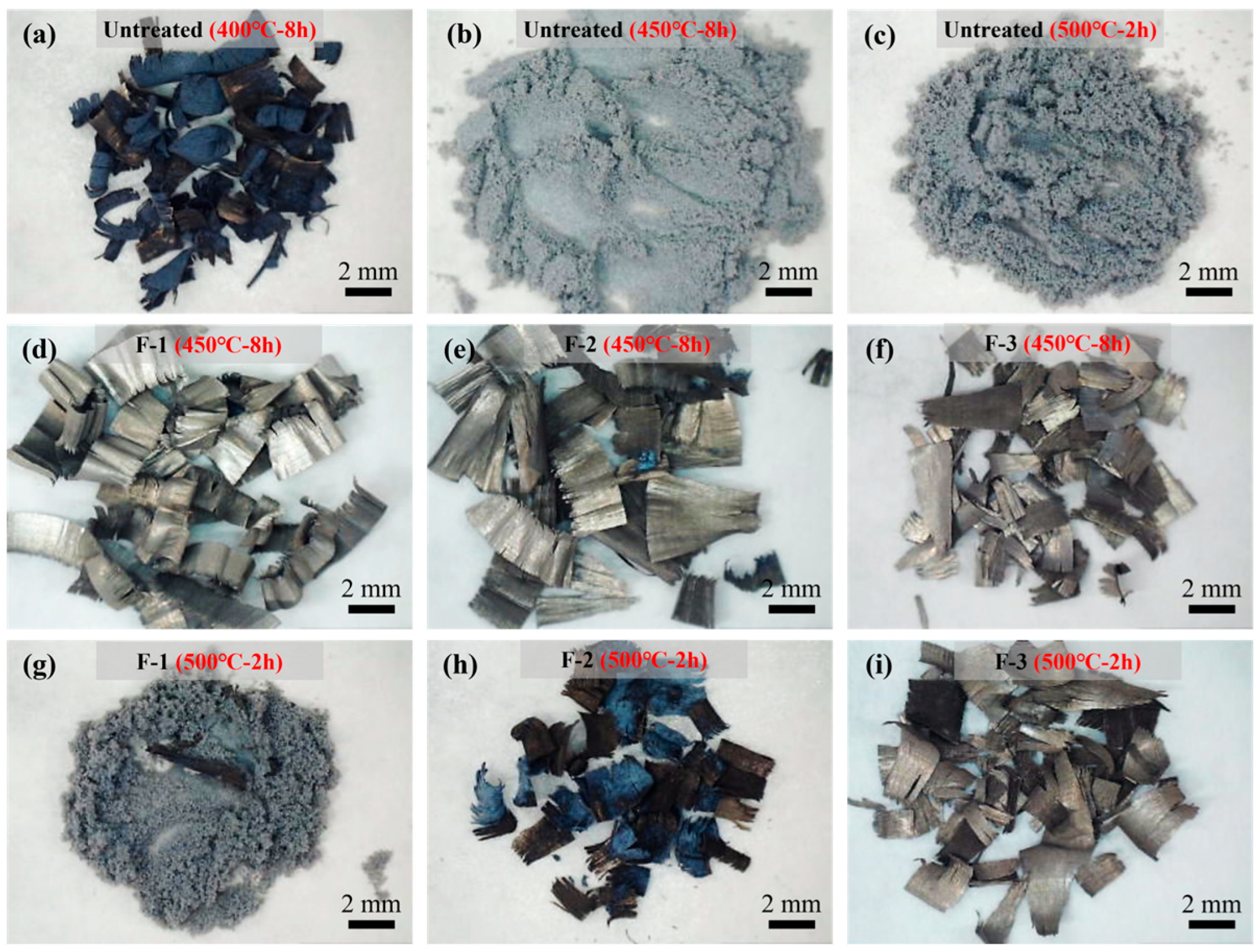

3.2. Isothermal High-Temperature Oxidation of Untreated and Fluorinated AZ31

4. Conclusions

- The high-temperature oxidation resistance of the AZ31 alloy is significantly inferior to that of pure Mg, primarily because of the influence of its internal-phase constituents. The low-melting β-Mg17Al12 and Mg–Zn phases in AZ31 alloys promote accelerated magnesium evaporation at elevated temperatures, resulting in the rapid degradation of the oxide layer. In addition, Al exhibits a weaker affinity for oxygen than Mg and therefore cannot readily diffuse to the surface to form a dense protective Al2O3 layer. Consequently, the high-temperature oxidation resistance of AZ31 is lower than that of pure Mg. In this study, AZ31 underwent catastrophic oxidation after only 1 h at 450 °C, and prolonged exposure ultimately led to the complete transformation of the alloy into gray-MgO powder. Compared with the materials employed in other studies, machining chips, owing to their larger specific surface area, exhibit more rapid and severe oxidation behavior under high-temperature conditions.

- In contrast, direct fluorination with F2 gas significantly improved the high-temperature oxidation resistance of the AZ31 alloy. By adjusting the fluorination parameters, such as temperature, pressure, and reaction duration, the uniformity and coverage of the surface MgF2 layer can be further enhanced. Notably, the F-3 sample exhibited a mass gain of only 0.68% in the TG test at 450 °C for 12 h, compared with 64.6% for the untreated AZ31 sample, demonstrating excellent oxidation resistance. Under the tests conducted at 500 °C for 2 h, the F-3 sample (2.74%) exhibited superior high-temperature oxidation resistance compared with F-1 (42.44%) and F-2 (29.15%).

- Compared with pure Mg, the phase constituents of AZ31 exerted a more pronounced detrimental effect on the integrity of the protective film at elevated temperatures. Therefore, future work should focus on optimizing the fluorination strategy, such as improving the film density and adjusting the film thickness, to further address the insufficient high-temperature oxidation resistance of AZ31 alloys. Furthermore, fluorination treatment will be carried out on the AZ alloy material of the sheet, and analysis and research will be conducted to better analyze the thickness of the magnesium fluoride layer and calculate the high-temperature oxidation kinetics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, J.; Miao, J.; Balasubramani, N.; Cho, D.H.; Avey, T.; Chang, C.-Y.; Luo, A.A. Magnesium Research and Applications: Past, Present and Future. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 3867–3895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Atrens, A.; Mo, N.; Zhang, M.-X. Oxidation of Magnesium Alloys at Elevated Temperatures in Air: A Review. Corros. Sci. 2016, 112, 734–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedrich, H.; Schumann, S. Research for a “New Age of Magnesium” in the Automotive Industry. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 117, 276–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Chen, T.; Tang, A.; Wu, L.; Li, D.; Steinbrück, M.; Pan, F. The Oxidation Behavior and Reaction Thermodynamics and Kinetics of the Mg-X (X = Ca/Gd/Y) Binary Alloys. Corros. Sci. 2023, 225, 111609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Lan, Q.; Wang, A.; Le, Q.; Yang, F.; Li, X. Effect of Ca Additions on Ignition Temperature and Multi-Stage Oxidation Behavior of AZ80. Metals 2018, 8, 766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tekumalla, S.; Gupta, M. An Insight into Ignition Factors and Mechanisms of Magnesium Based Materials: A Review. Mater. Des. 2017, 113, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dai, J.; Zhang, R.; Ba, Z.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion Behavior of Mg–3Gd–1Zn–0.4Zr Alloy with and without Stacking Faults. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Yin, Y.; Mo, N.; Zhang, M.; Atrens, A. Recent Understanding of the Oxidation and Burning of Magnesium Alloys. Surf. Innov. 2019, 7, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondori, B.; Mahmudi, R. Impression Creep Characteristics of a Cast Mg Alloy. Met. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 2007–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. The Reactive Element Effect on High-Temperature Oxidation of Magnesium. Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 264–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, D.; Ding, H.; Zhi, M.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, M. Research Progress on the Oxidation Behavior of Ignition-Proof Magnesium Alloy and Its Effect on Flame Retardancy with Multi-Element Rare Earth Additions: A Review. Materials 2024, 17, 3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, C. Beitrag zur Theorie des Anlaufvorgangs. Z. Phys. Chem. 1933, 21, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Oxidation Characteristics of Magnesium Alloys. JOM 2012, 64, 1477–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Yonezawa, S. Surface Fluorination of Magnesium Powder: Enhancing High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance. Materials 2025, 18, 5307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, J.; Ramakrishna, S. Applications of Magnesium and Its Alloys: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, L.; Kong, C.; Zhao, C.; Cui, X.; Zhang, L.; Song, Y.; Lu, Y.; Xia, L.; Ma, K.; Yang, H.; et al. Recent Advances on Magnesium Alloys for Automotive Cabin Components: Materials, Applications, and Challenges. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 9924–9961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiler, J.P. The Role of the Mg17Al12-Phase in the High-Pressure Die-Cast Magnesium-Aluminum Alloy System. J. Magnes. Alloys 2023, 11, 4235–4246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrabal, R.; Pardo, A.; Merino, M.C.; Mohedano, M.; Casajús, P.; Paucar, K.; Matykina, E. Oxidation Behavior of AZ91D Magnesium Alloy Containing Nd or Gd. Oxid. Met. 2011, 76, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emuna, M.; Greenberg, Y.; Hevroni, R.; Korover, I.; Yahel, E.; Makov, G. Phase Diagrams of Binary Alloys under Pressure. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 687, 360–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, T.-S.; Liu, J.-B.; Wei, P.-S. Oxide Films on Magnesium and Magnesium Alloys. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2007, 104, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerwinski, F. Controlling the Ignition and Flammability of Magnesium for Aerospace Applications. Corros. Sci. 2014, 86, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Le, Q.; Zhong, X.; Ji, A.; Jiang, Y.; Lin, Y.; Li, D. Effect of Ca and Y Microalloying on Oxidation Behavior of AZ31 at High Temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2024, 1002, 175472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.; Li, X.; Le, Q.; Guo, R.; Lan, Q.; Cui, J. Effect of REs (Y, Nd) Addition on High Temperature Oxidation Kinetics, Oxide Layer Characteristic and Activation Energy of AZ80 Alloy. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 1281–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.S.; Pan, C.X.; Cai, Q.Z.; Wei, B.K. Characterization of Coating Morphology and Heat-Resistance in Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation of Magnesium Alloy. Mater. Sci. Forum 2007, 561–565, 2459–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorský, D.; Kubásek, J.; Vojtěch, D. Magnesium Composite Materials Prepared by Extrusion of Chemically Treated Powders. Manuf. Technol. 2019, 19, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, D.; Kubasek, J.; Jablonska, E.; Kaufmanova, J.; Vojtech, D. Mechanical, Corrosion and Biological Properties of Advanced Biodegradable Mg–MgF2 and WE43-MgF2 Composite Materials Prepared by Spark Plasma Sintering. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 825, 154016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, S.-M.; Liu, X.-L. Microstructure, Composition, and Depth Analysis of Surface Films Formed on Molten AZ91D Alloy under Protection of SF6 Mixtures. Met. Mat. Trans. A 2007, 38, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buradagunta, R.S.; Ganesh, K.V.; Pavan, P.; Vadapalli, G.; Swarnalatha, C.; Swapna, P.; Bindukumar, P.; Reddy, G. Effect of Aluminum Content on Machining Characteristics of AZ31 and AZ91 Magnesium Alloys during Drilling. J. Magnes. Alloys 2016, 4, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, H.; Jiang, H.; Mu, X.; Yu, J. The Oxidation Properties of MgF2 Particles in Hydrofluorocarbon/Air Atmosphere at High Temperatures. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 688, 033086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Hu, K.; Tu, J.; Aierken, A.; Xu, D.; Song, G.; Sun, X.; Li, L.; Chen, K.; Zhang, D.; et al. Broadband Graded Refractive Index TiO2/Al2O3/MgF2 Multilayer Antireflection Coating for High Efficiency Multi-Junction Solar Cell. Sol. Energy 2021, 217, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarowicz, A.; Bailey, C.; Weiher, N.; Kemnitz, E.; Schroeder, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Wander, A.; Searle, B.; Harrison, N. Electronic Structure of Lewis Acid Sites on High Surface Area Aluminium Fluorides: A Combined XPS and Ab Initio Investigation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2009, 11, 5664–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Böse, O.; Kemnitz, E.; Lippitz, A.; Unger, W.E.S. XPS Analysis of β-AlF3 Phases with Al Successively Substituted by Mg to Be Used for Heterogeneously Catalyzed Cl/F Exchange Reactions. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 120, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Jiang, B.; Yang, H.; Yang, Q.; Xia, X.; Pan, F. High Temperature Oxidation Behavior of Mg-Y-Sn, Mg-Y, Mg-Sn Alloys and Its Effect on Corrosion Property. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 353, 1013–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample Name | Temperature (°C) | Time (h) | F2 Pressure (Torr) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | - | - | - |

| F-1 | 25 | 1 | 380 |

| F-2 | 100 | 5 | 570 |

| F-3 | 200 | 5 | 570 |

| Sample Name | Before Fluorination (mg) | After Fluorination (mg) | Weight Changes (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| F-1 | 340.88 | 339.43 | −0.43 |

| F-2 | 338.74 | 337.33 | −0.42 |

| F-3 | 339.85 | 339.60 | −0.07 |

| Sample Name | Elemental Contents (at %) | F/Mg | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | O | C | Al | F | ||

| Untreated | 11.55 | 30.35 | 57.00 | 1.10 | - | - |

| F-1 | 28.34 | 25.17 | 24.41 | 2.27 | 19.80 | 0.70 |

| F-2 | 21.95 | 19.92 | 18.69 | 2.23 | 37.21 | 1.69 |

| F-3 | 23.76 | 9.36 | 14.47 | 2.23 | 50.18 | 2.11 |

| Sample Name | Elemental Contents (at %) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg | O | C | Al | F | |

| Untreated (400 °C-8 h) | 32.36 | 54.0 | 10.4 | 3.11 | - |

| Untreated (450 °C-8 h) | 31.55 | 48.23 | 16.65 | 3.57 | - |

| F-1 (450 °C-8 h) | 39.87 | 45.65 | 8.63 | 4.59 | 1.26 |

| F-2 (450 °C-8 h) | 30.41 | 44.32 | 19.23 | 3.59 | 2.45 |

| F-3 (450 °C-8 h) | 37.36 | 36.69 | 17.99 | 3.08 | 4.88 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Kim, J.-H.; Yonezawa, S. Effects of Direct Fluorination on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Materials 2026, 19, 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010156

Wang Y, Kim J-H, Yonezawa S. Effects of Direct Fluorination on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Materials. 2026; 19(1):156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010156

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yu, Jae-Ho Kim, and Susumu Yonezawa. 2026. "Effects of Direct Fluorination on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy" Materials 19, no. 1: 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010156

APA StyleWang, Y., Kim, J.-H., & Yonezawa, S. (2026). Effects of Direct Fluorination on the High-Temperature Oxidation Resistance of AZ31 Magnesium Alloy. Materials, 19(1), 156. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010156