Bioceramics Based on Li-Modified Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

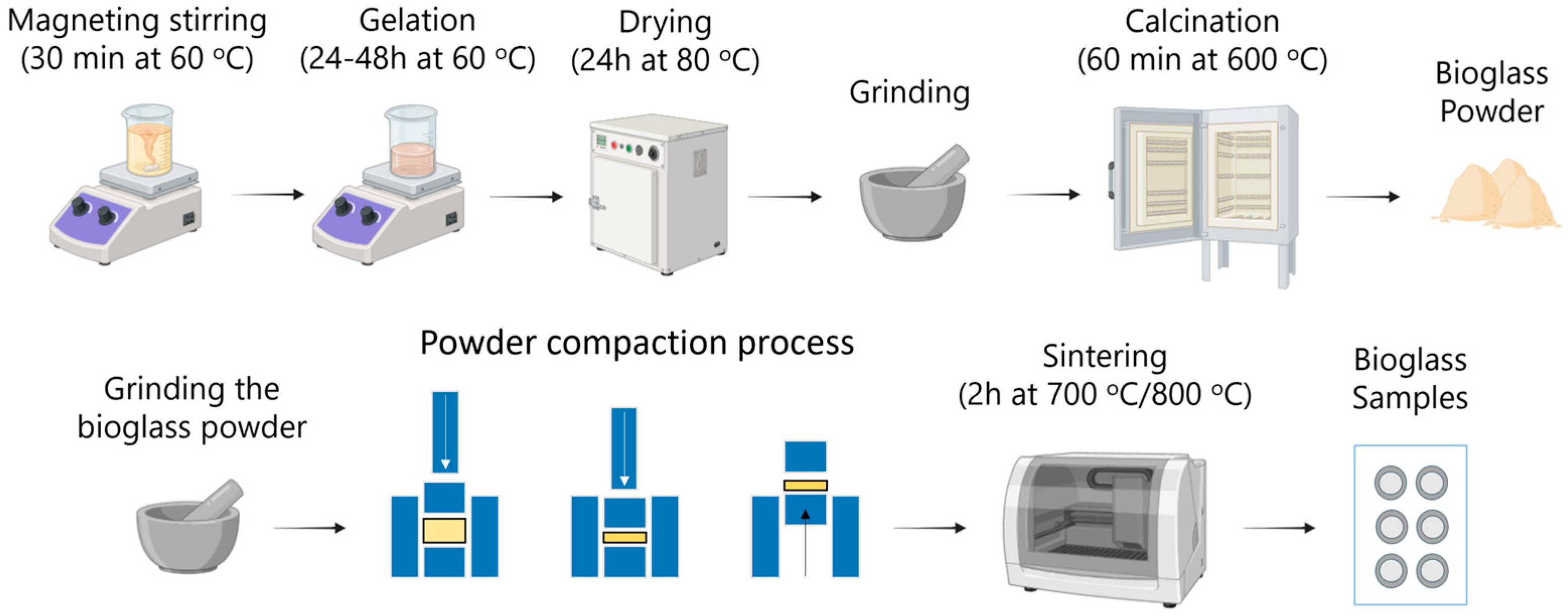

2.1. Processing of Bioglass-Based Materials

2.2. Characterisation Techniques and Instrumentation

3. Results and Discussion

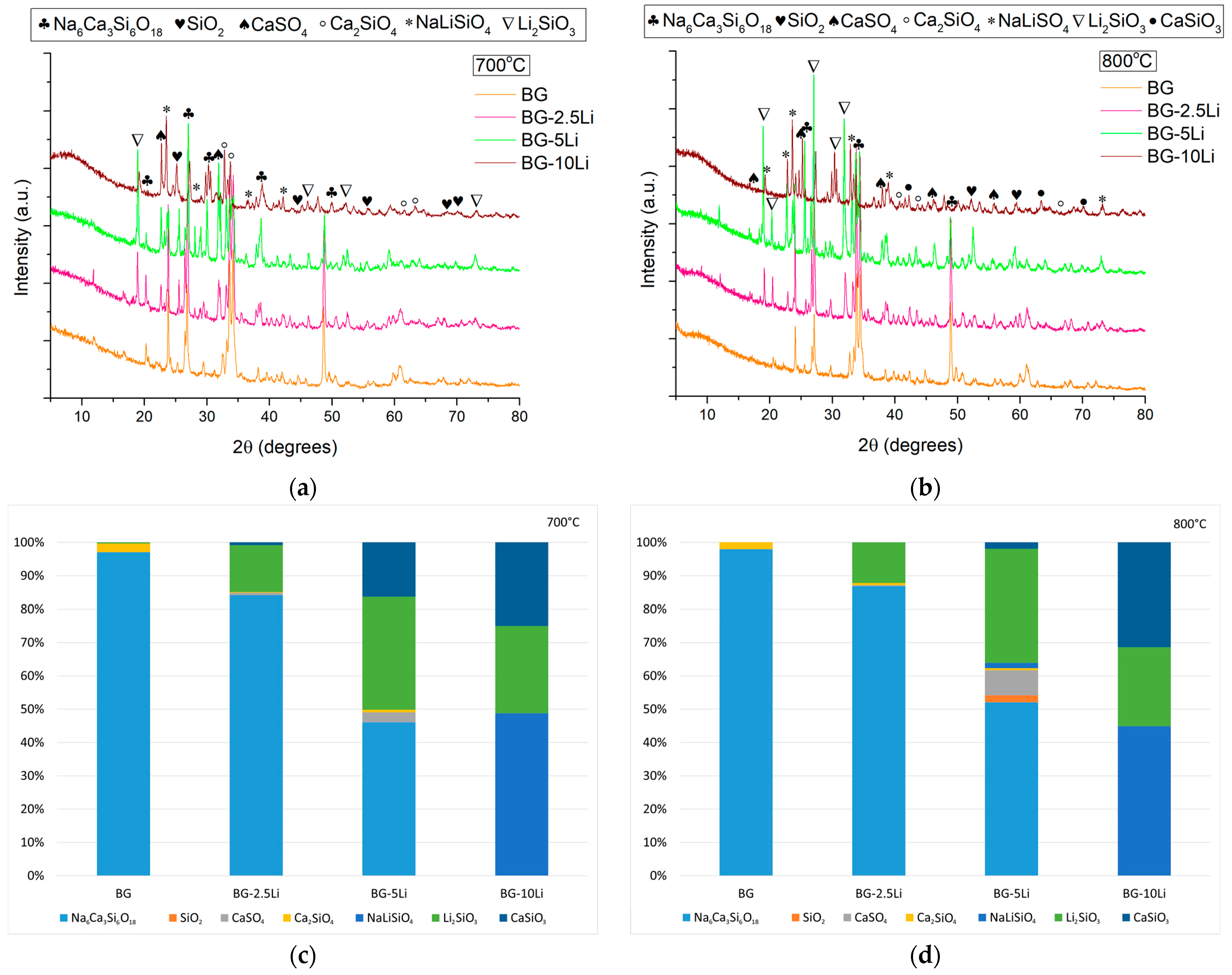

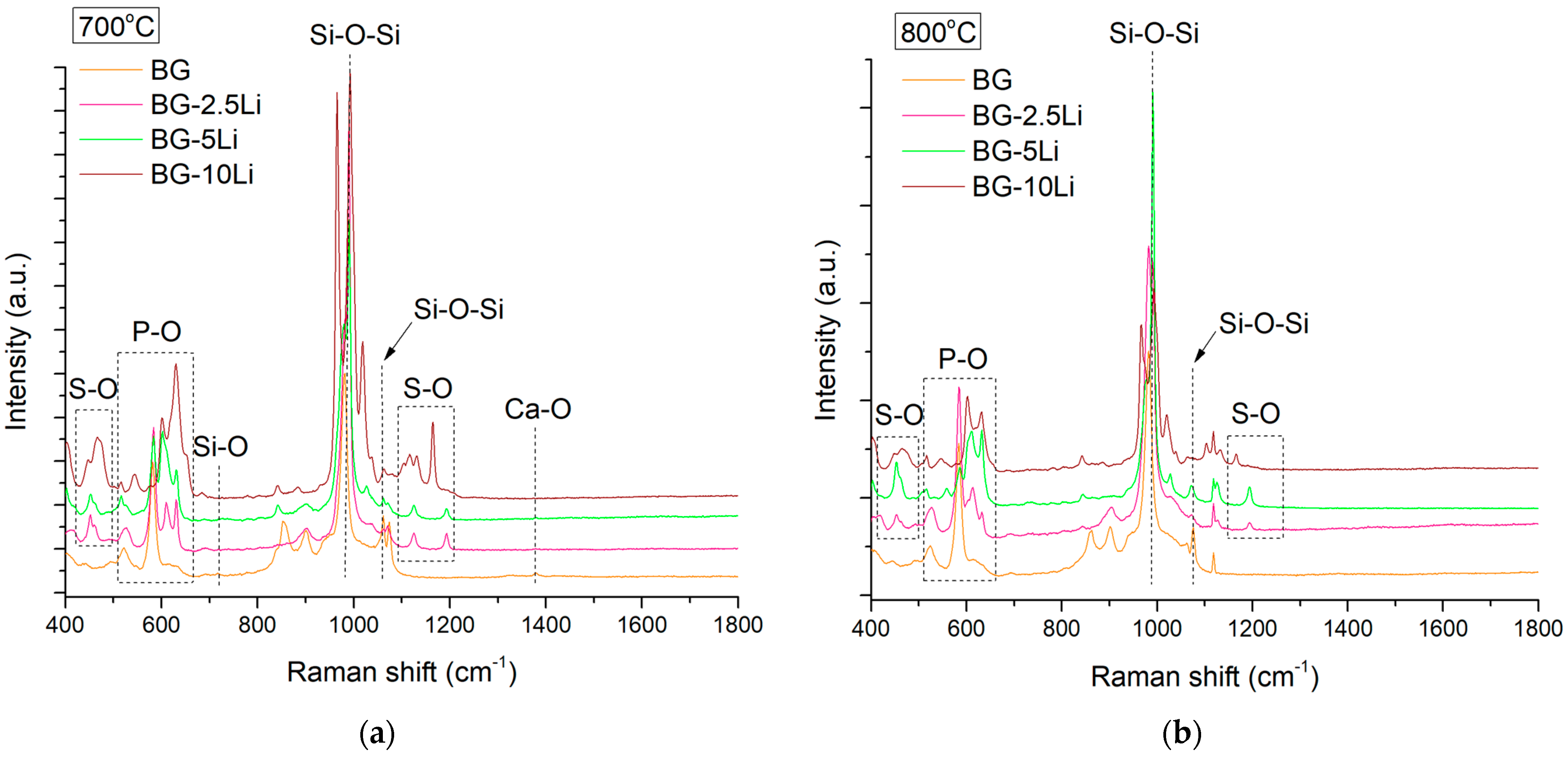

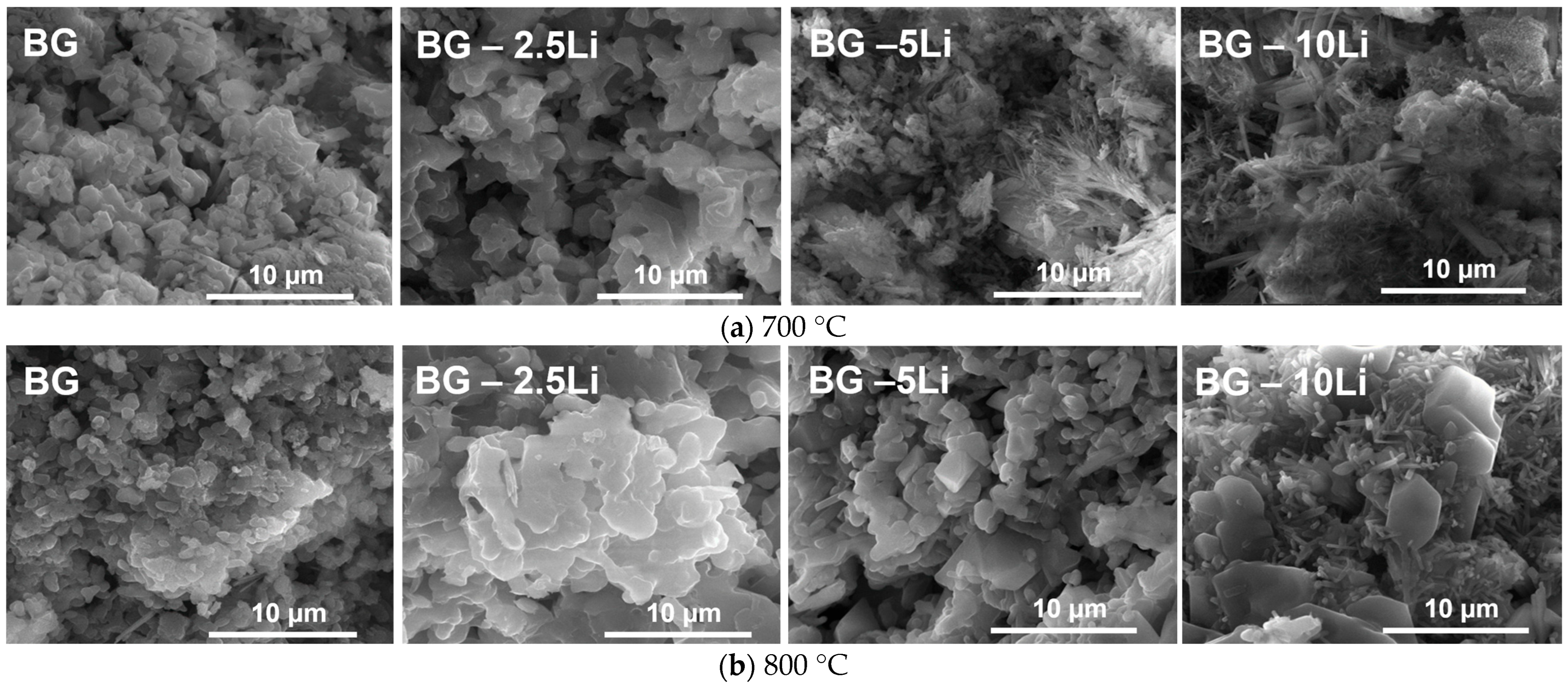

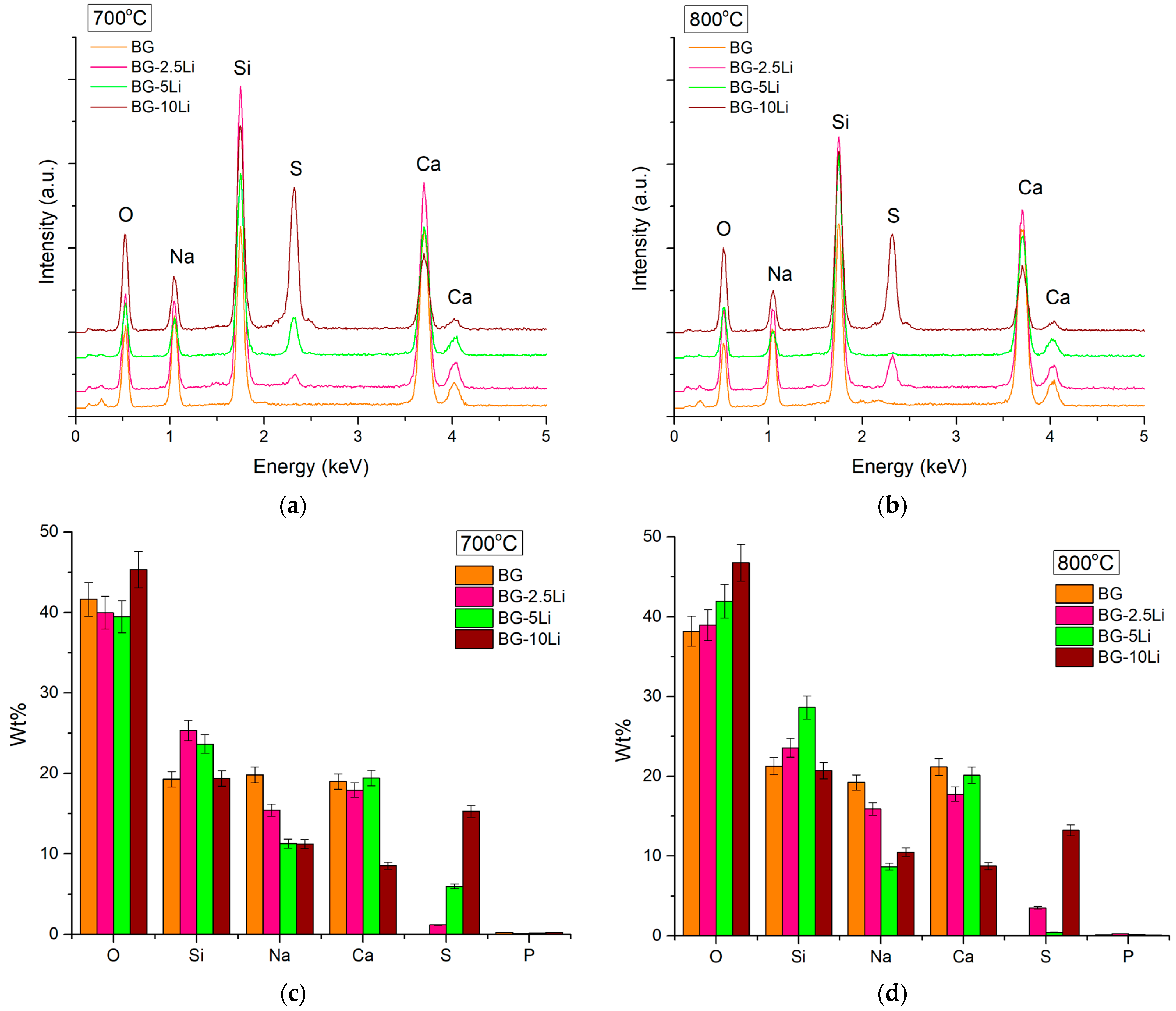

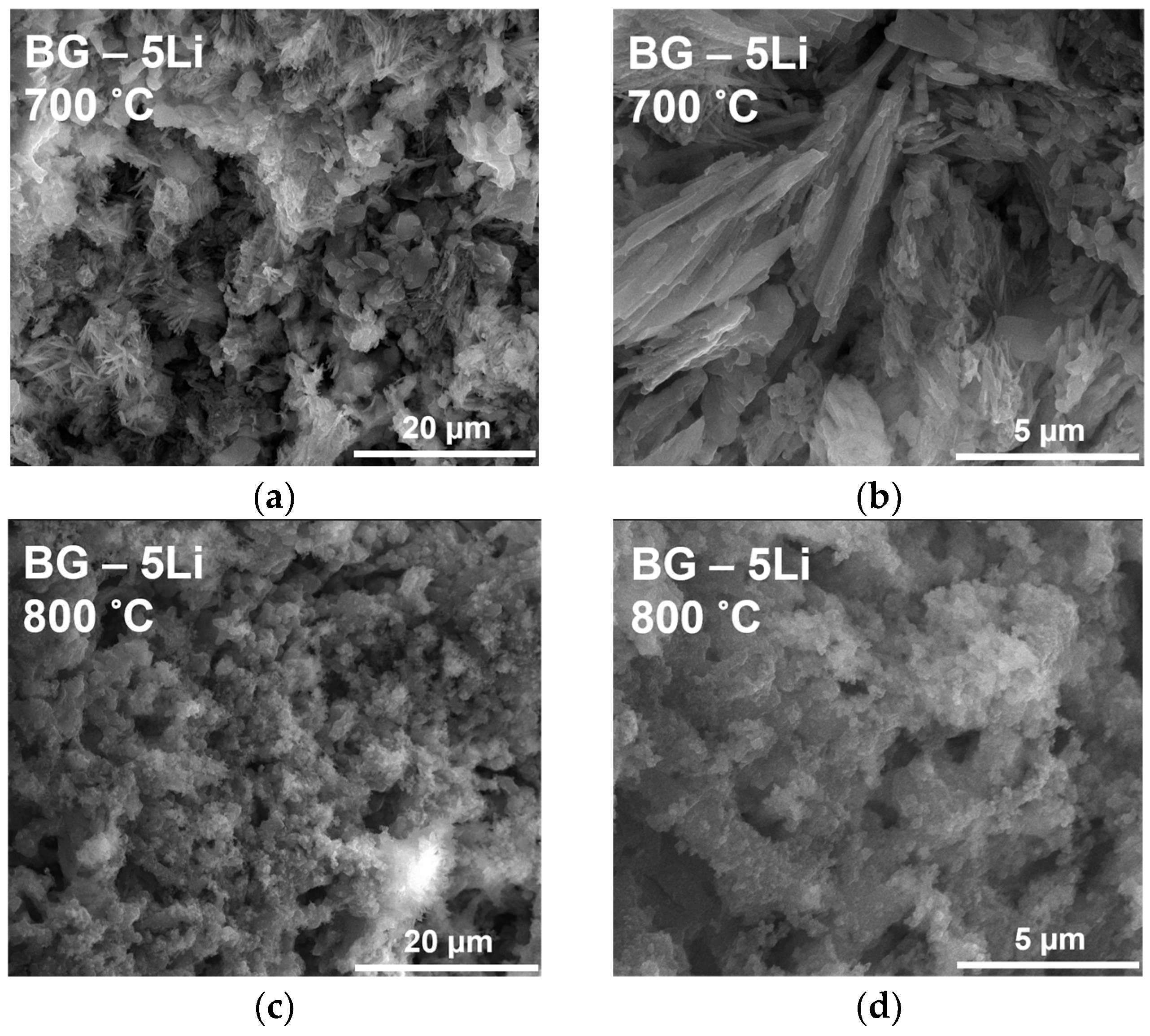

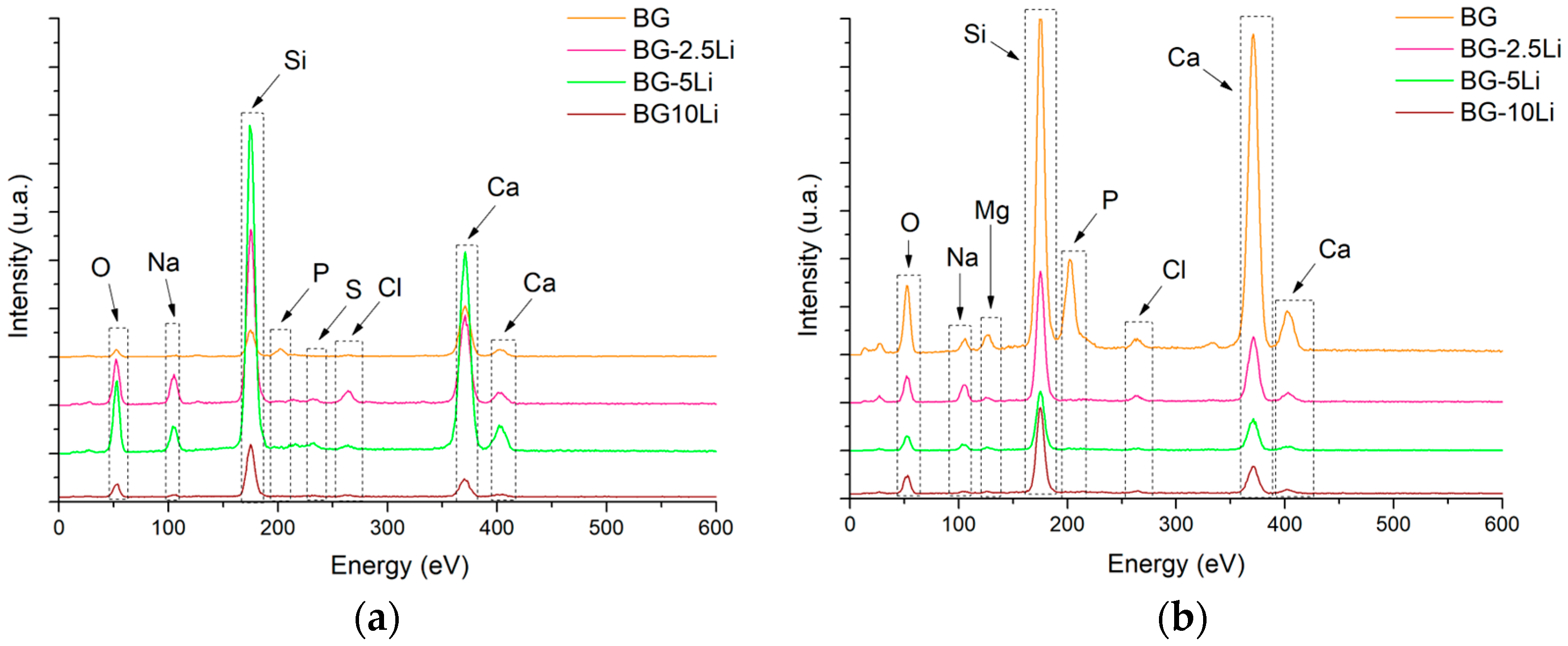

3.1. Morpho-Structural Analysis

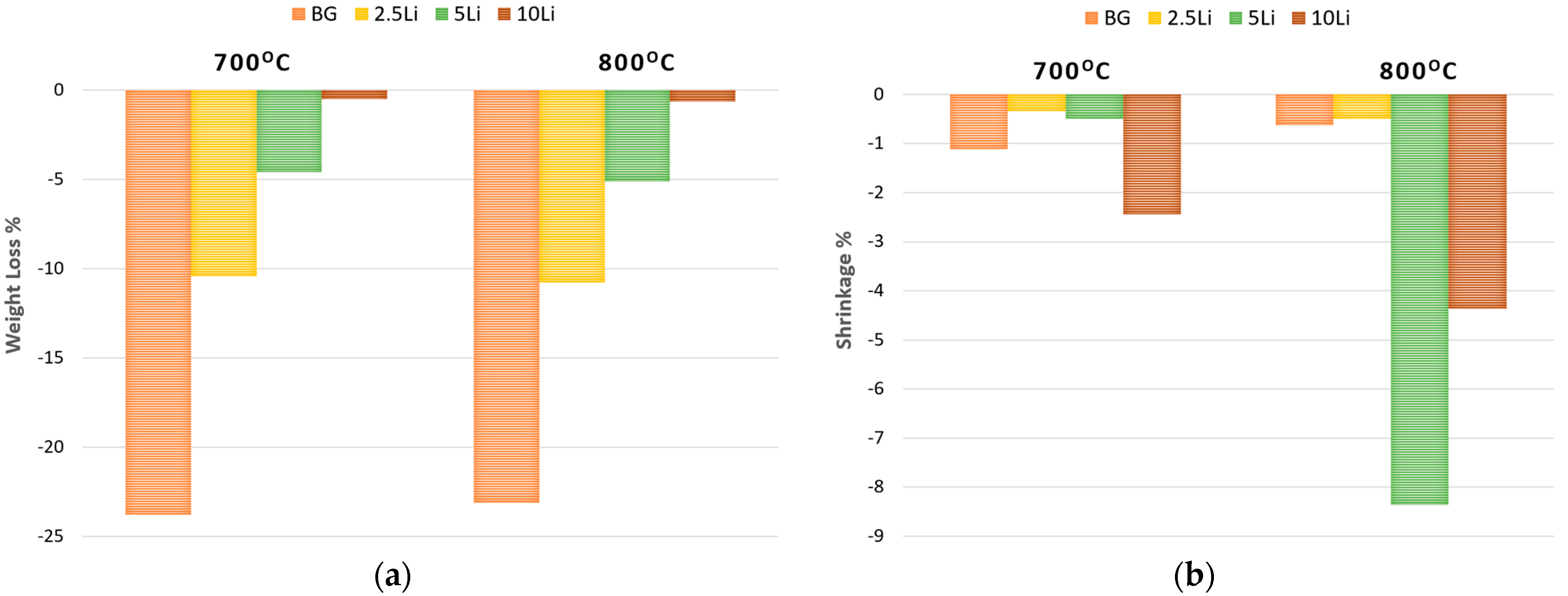

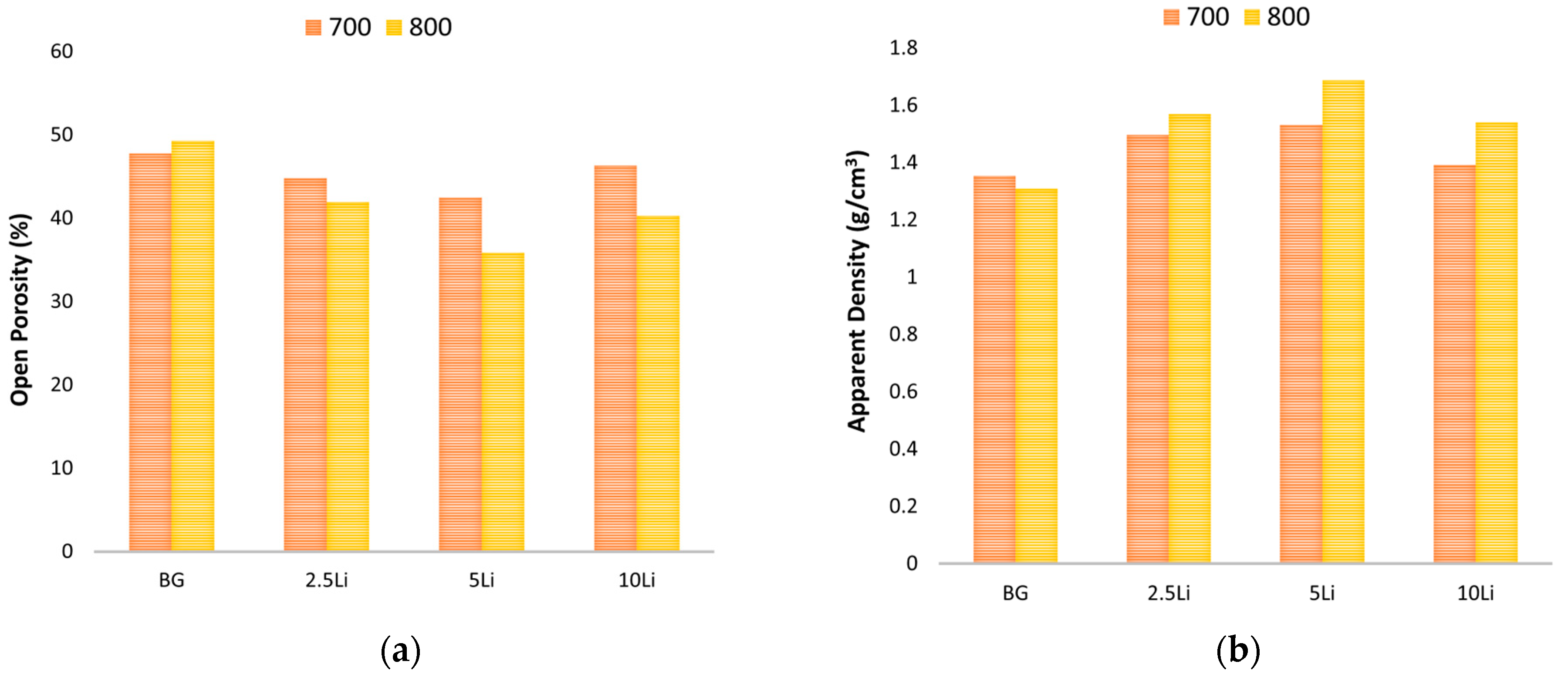

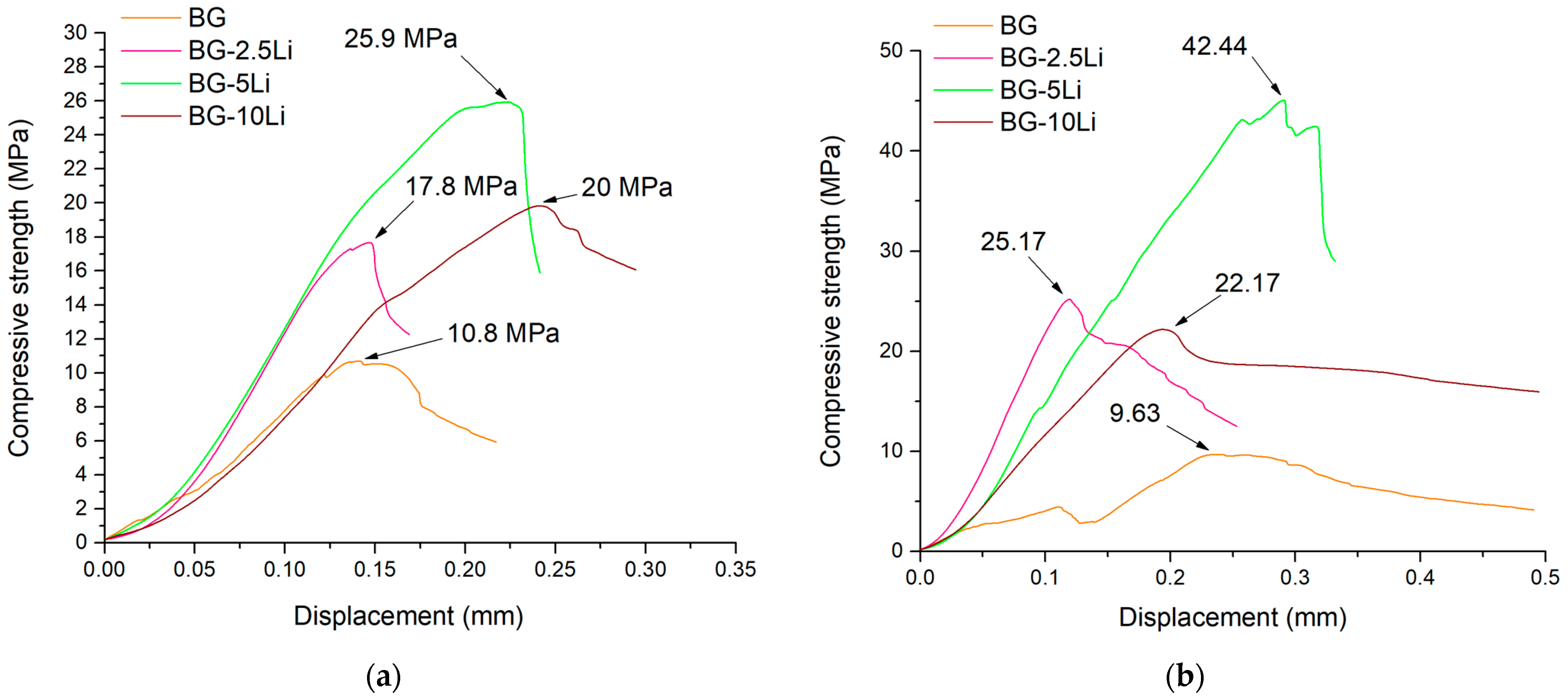

3.2. Ceramic and Mechanic Properties Evaluation

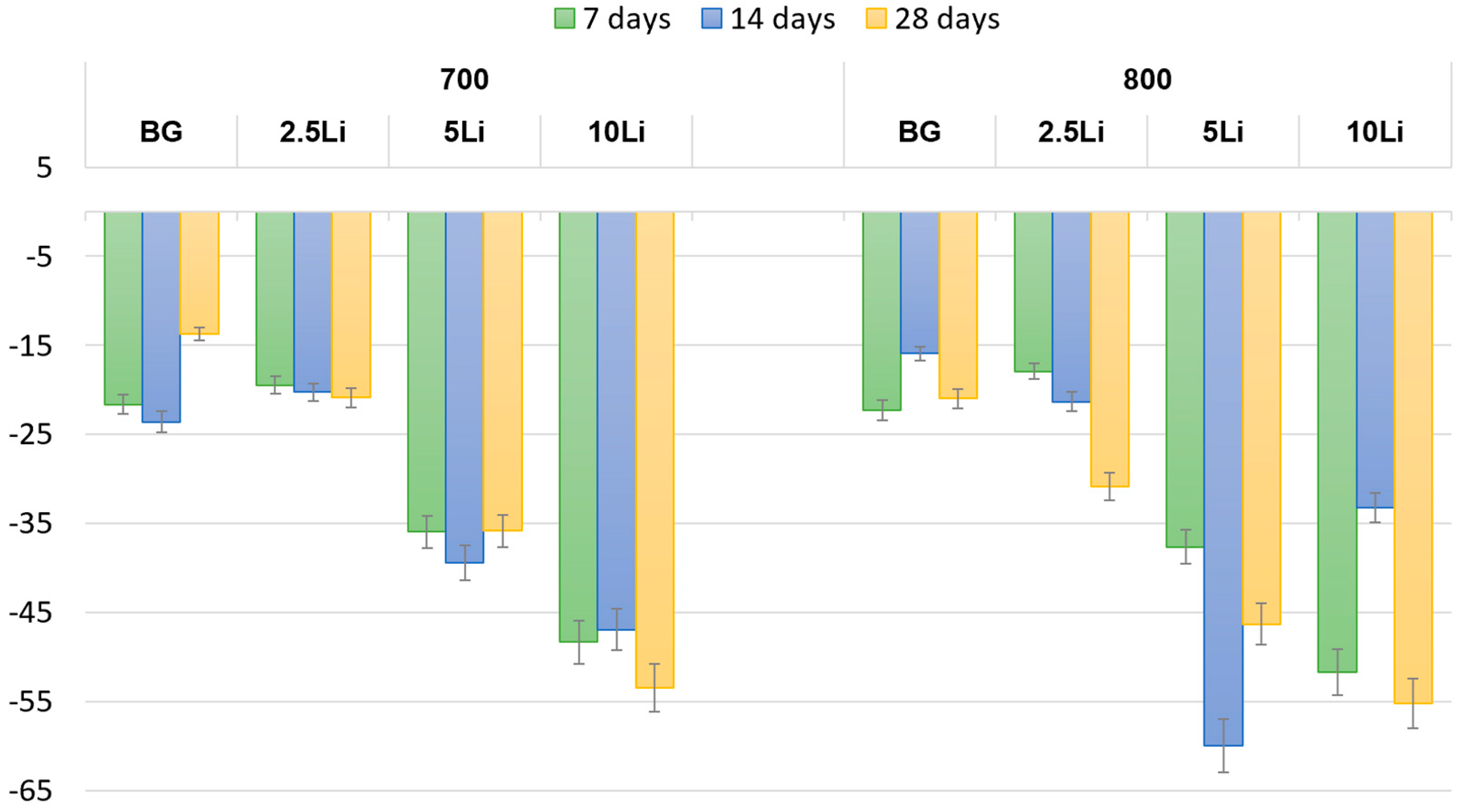

3.3. In Vitro Behaviour

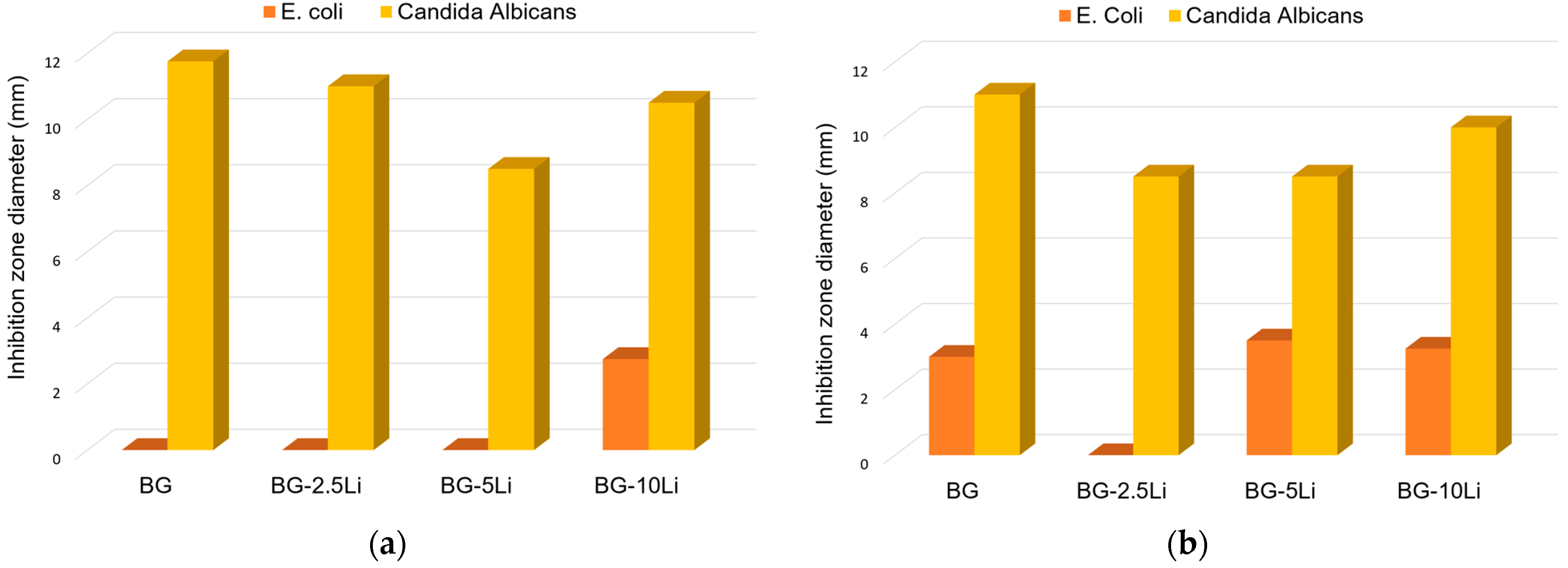

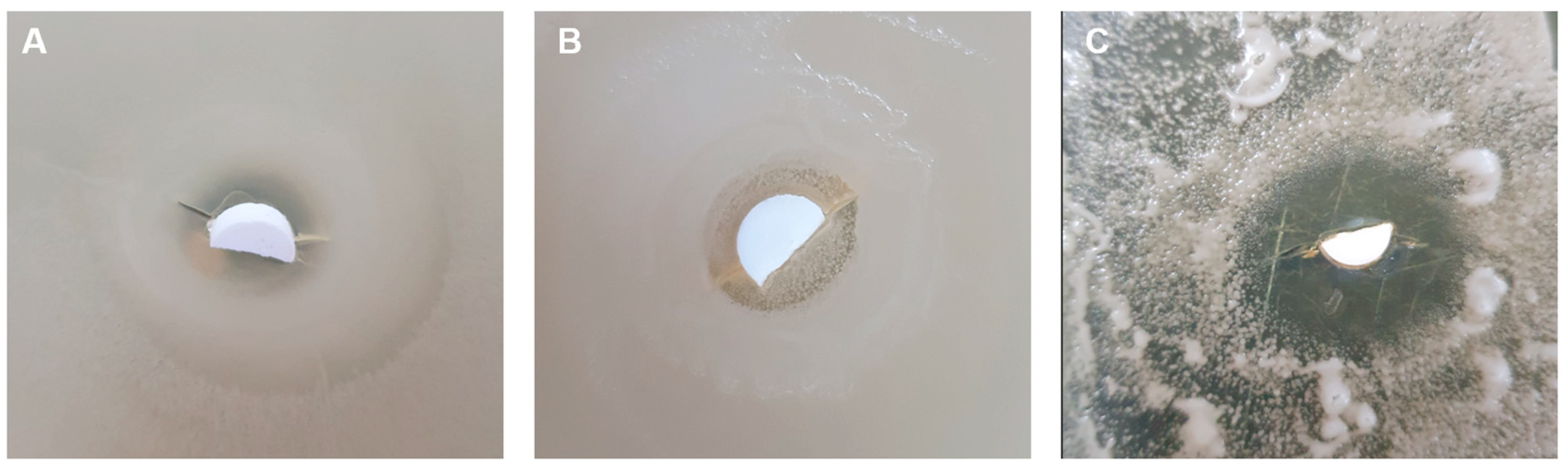

3.4. Antibacterial Assessment

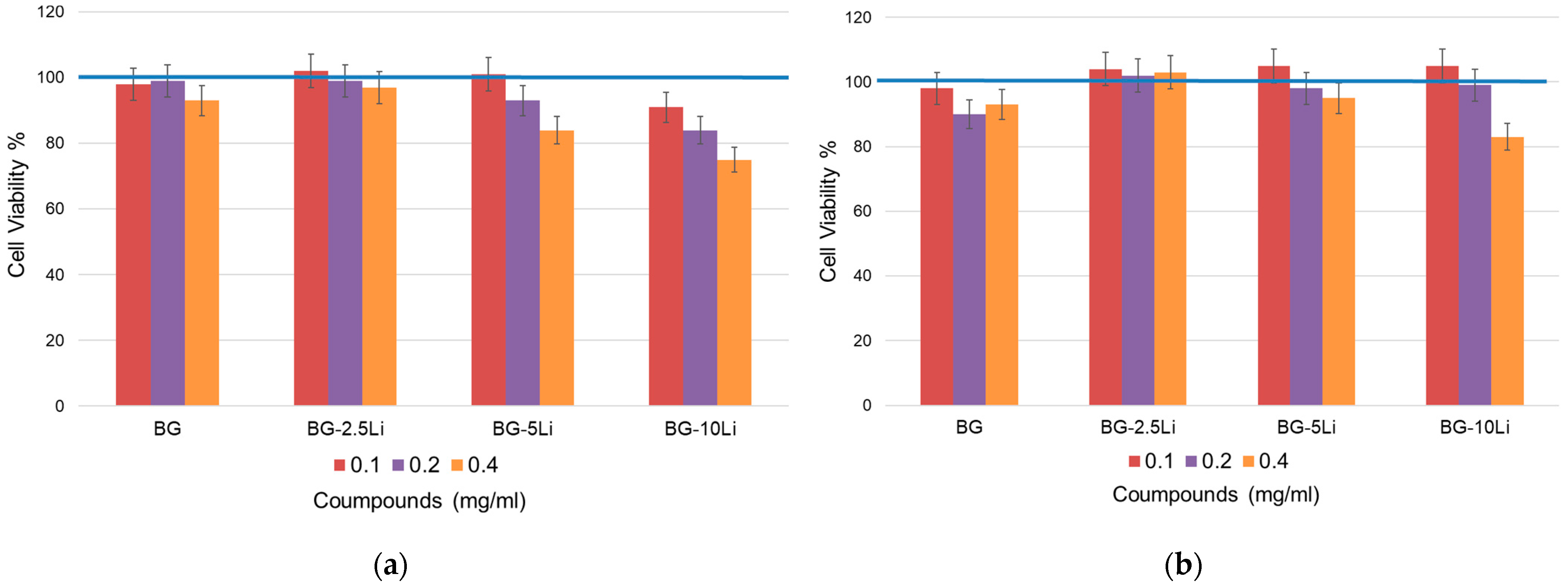

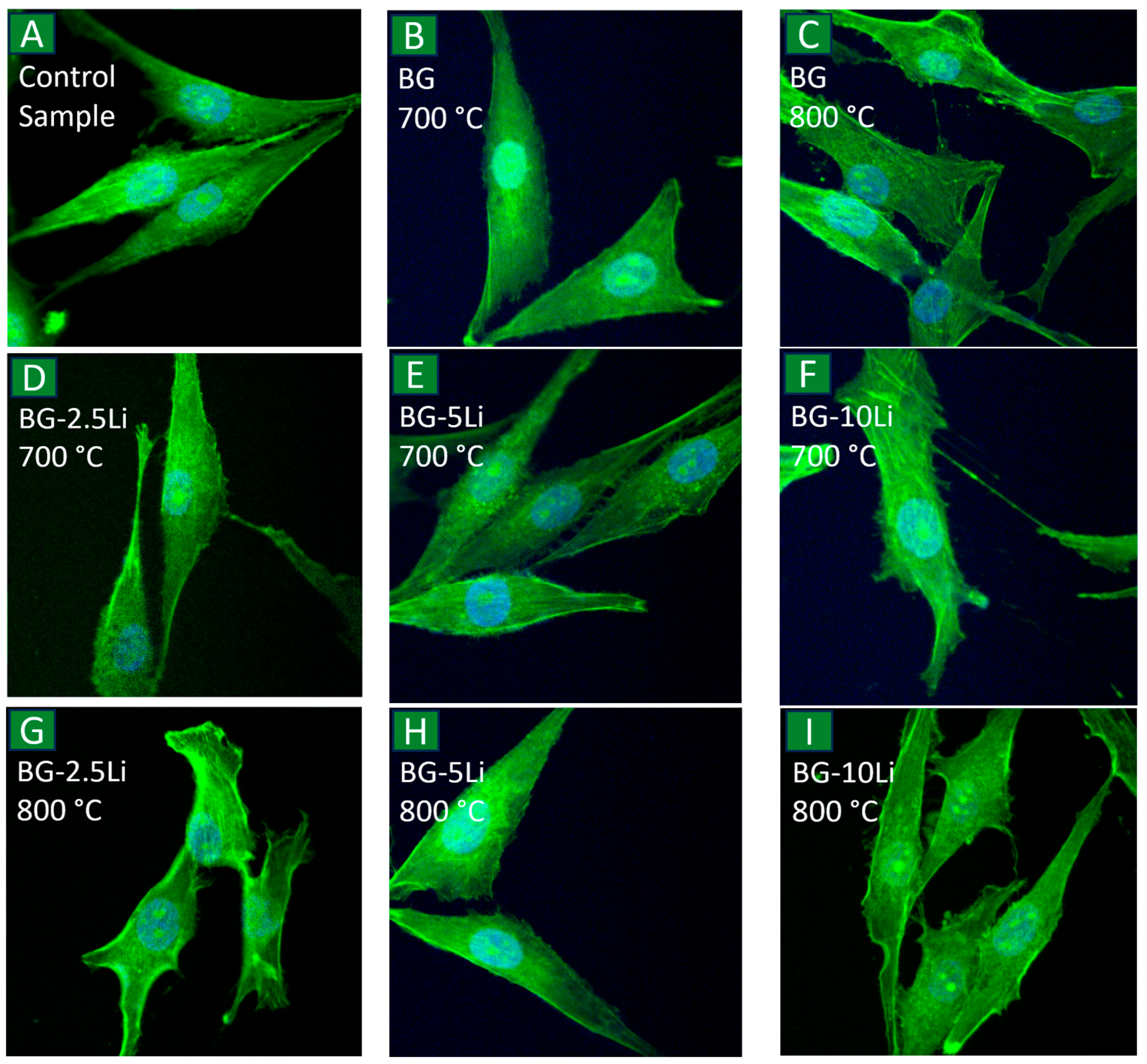

3.5. Cell Viability

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carrascal-Hernández, D.C.; Martínez-Cano, J.P.; Rodríguez Macías, J.D.; Grande-Tovar, C.D. Evolution in Bone Tissue Regeneration: From Grafts to Innovative Biomaterials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, K.; Ahuja, N.; Yacoub, A.S.; Brotto, L.; Young, S.; Mikos, A.; Aswath, P.; Varanasi, V. Revolutionizing Bone Regeneration: Advanced Biomaterials for Healing Compromised Bone Defects. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1217054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaou, M.H.; Furkó, M.; Balázsi, K.; Balázsi, C. Advanced Bioactive Glasses: The Newest Achievements and Breakthroughs in the Area. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makurat-Kasprolewicz, B.; Ipakchi, H.; Rajaee, P.; Ossowska, A.; Hejna, A.; Farokhi, M.; Mottaghitalab, F.; Pawlak, M.; Rabiee, N.; Belka, M.; et al. Green Engineered Biomaterials for Bone Repair and Regeneration: Printing Technologies and Fracture Analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 152703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Qiu, L.; Liu, D.; Dai, S.; Sheu, C.L. The Role of Smart Polymeric Biomaterials in Bone Regeneration: A Review. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1240861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.C.; Lu, X.T.; Bai, T.; Yang, H.; Li, D.; Chen, M.; Wang, L.; Meng, M. Mechanical Behavior and Biological Activity Performance of Li+/Ca2+@Li+/K+ Ion-Exchanged Lithium Disilicate Glass-Ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 47157–47171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, V.; Lakshmi, T. Bioglass: A Novel Biocompatible Innovation. J. Adv. Pharm. Technol. Res. 2013, 4, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Alexander, D.; Čapek, J.; Geis-Gerstorfer, J.; Wan, G.; Han, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, A. Zinc Based Biodegradable Metals for Bone Repair and Regeneration: Bioactivity and Molecular Mechanisms. Mater. Today Bio 2024, 25, 100932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kadhim, Z.J.; Al-Hasani, F.J.; Al-hassani, E.S. Investigation the Bioactivity of Cordierite/Hydroxyapatite Ceramic Material Used in Bone Regeneration. Silicon 2023, 15, 6673–6682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, F.; McGuire, J.; Gupta, P.; Nikolaou, A.; Kyffin, B.A.; Kelly, N.L.; Hanna, J.V.; Gutierrez-Merino, J.; Knowles, J.C.; Baek, S.Y.; et al. Antibacterial Copper-Doped Calcium Phosphate Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 5, 6054–6062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kong, X.; Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B. Current Advances of Antibacterial Biomaterials for Bone Regeneration. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 12, 2400960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, P.K.; Hsieh, C.-Y.; Shen, Y.-T.; Tsai, Y.-H.; Tsai, H.-W.; Yao, C.-L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, P.-C. Synthesis and Physicochemical Properties of Doxorubicin-Loaded PEGA Containing Amphiphilic Block Polymeric Micelles. J. Polym. Res. 2024, 31, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoara, A.I.; Alecu, A.E.; Balaceanu, G.C.; Puscasu, E.M.; Vasile, B.S.; Trusca, R. Fabrication and Characterization of Porous Diopside/Akermanite Ceramics with Prospective Tissue Engineering Applications. Materials 2023, 16, 5548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, M.A.; Lancheros, Y.; Garzón-Alvarado, D.A. Geometric and Mechanical Properties Evaluation of Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Applications Designing by a Reaction-Diffusion Models and Manufactured with a Material Jetting System. J. Comput. Des. Eng. 2016, 3, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos Gomes, D.; de Sousa Victor, R.; de Sousa, B.V.; de Araújo Neves, G.; de Lima Santana, L.N.; Menezes, R.R. Ceramic Nanofiber Materials for Wound Healing and Bone Regeneration: A Brief Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, K.J.; Czechowska, J.P.; Yousef, E.S.; Zima, A. Novel Phosphate Bioglasses and Bioglass-Ceramics for Bone Regeneration. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 45976–45985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, H.; Gao, X.; Zhang, C. Effect of Manganese Doping on the Bioactivity and Antioxidant Activity of Bioglass. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process 2025, 131, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, A.A.; El-Sayed, M.M.H.; Emam, A.N.; Abd-Rabou, A.A.; Dawood, R.M.; Oudadesse, H. Bioactive Glass Doped with Noble Metal Nanoparticles for Bone Regeneration:In Vitrokinetics and Proliferative Impact on Human Bone Cell Line. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 25628–25638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, S.K.; Mahato, A.; Kundu, B.; Mukherjee, P. Doped Bioactive Glass Materials in Bone Regeneration. In Advanced Techniques in Bone Regeneration; InTech: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fotu, M.; Manolache, Ș.; Nicoară, A.-I.; Busuioc, C. Synthesis and Characterization of Lithium-Substituted Bioglass-Ceramic Powders. UPB Sci. Bull. Ser. B 2025, 87, 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Crovace, M.C.; Souza, M.T.; Chinaglia, C.R.; Peitl, O.; Zanotto, E.D. Biosilicate®—A Multipurpose, Highly Bioactive Glass-Ceramic. in Vitro, in Vivo and Clinical Trials. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 432, 90–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peitl, O.; Dutra Zanotto, E.; Hench, L.L. Highly Bioactive P2O5–Na2O–CaO–SiO2 Glass-Ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2001, 292, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Yu, F.; Chen, L.; Xia, L.; Wu, C.; Fang, B. Lithium-Containing Biomaterials Stimulate Cartilage Repair through Bone Marrow Stromal Cells-Derived Exosomal MiR-455-3p and Histone H3 Acetylation. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2023, 12, e2202390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez Gramajo, F.; Rivoira, M.A.; Rodríguez, V.; Vargas, G.; Vera Mesones, R.; Zago, M.P.; Boccaccini, A.R.; Gorustovich, A. Lithium-Containing 45S5 Bioglass-Derived Glass-Ceramics Have Antioxidant Activity and Induce New Bone Formation in a Rat Preclinical Model of Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Biomed. Mater. 2025, 20, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schatkoski, V.M.; Larissa do Amaral Montanheiro, T.; Canuto de Menezes, B.R.; Pereira, R.M.; Rodrigues, K.F.; Ribas, R.G.; Morais da Silva, D.; Thim, G.P. Current Advances Concerning the Most Cited Metal Ions Doped Bioceramics and Silicate-Based Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Engineering. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 2999–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguez-Pacheco, V.; Büttner, T.; Maçon, A.L.B.; Jones, J.R.; Fey, T.; De Ligny, D.; Greil, P.; Chevalier, J.; Malchere, A.; Boccaccini, A.R. Development and Characterization of Lithium-Releasing Silicate Bioactive Glasses and Their Scaffolds for Bone Repair. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2016, 432, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, N.Q.A.; Sa’at, N.K.; Zaid, M.H.M.; Zainuddin, N.; Mayzan, M.Z.H. Effect of Temperature Variations on the Fabrication of SLS-Na2CO3-ES-P2O5-CaF2-Al2O3 Based Bioglass-Ceramics. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghighi, F.D.; Sami, N.; Azizi, M.; Beidokhti, S.M.; Kiani Rashid, A.R. Sol-Gel-Synthesized Bioglass-Ceramics: Physical, Mechanical, and Biological Properties. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 1085–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Guo, L.; Shen, H.; An, X.; Jiang, H.; Ji, F.; Niu, Y. Degradability, Bioactivity, and Osteogenesis of Biocomposite Scaffolds of Lithium-Containing Mesoporous Bioglass and MPEG-PLGA-b-PLL Copolymer. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 4125–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmani, A.R.; Nekoofar, M.H.; Ebrahimi-Barough, S.; Azami, M.; Najafipour, S.; Moradpanah, S.; Ai, J. Preparation and In Vitro Osteogenic Evaluation of Biomimetic Hybrid Nanocomposite Scaffolds Based on Gelatin/Plasma Rich in Growth Factors (PRGF) and Lithium-Doped 45s5 Bioactive Glass Nanoparticles. J. Polym. Environ. 2023, 31, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Jiang, Q.; Yu, Y.; Xu, T.; Sun, H.; Deng, F.; Yu, X. Antibacterial Evaluation of Lithium-Loaded Nanofibrous Poly(L-Lactic Acid) Membranes Fabricated via an Electrospinning Strategy. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 676874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palza Cordero, H.; Castro Cid, R.; Diaz Dosque, M.; Cabello Ibacache, R.; Palma Fluxá, P. Li-Doped Bioglass® 45S5 for Potential Treatment of Prevalent Oral Diseases. J. Dent. 2021, 105, 103575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Alaohali, A.; Sawangboon, N.; Sharpe, P.T.; Brauer, D.S.; Gentleman, E. A Comparison of Lithium-Substituted Phosphate and Borate Bioactive Glasses for Mineralised Tissue Repair. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neubauer, T.; Bayer, G.S.; Wagner, M. Open Fractures and Infection. Acta Chir. Orthop. Trauma 2006, 73, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barabadi, Z.; Azami, M.; Sharifi, E.; Karimi, R.; Lotfibakhshaiesh, N.; Roozafzoon, R.; Joghataei, M.T.; Ai, J. Fabrication of Hydrogel Based Nanocomposite Scaffold Containing Bioactive Glass Nanoparticles for Myocardial Tissue Engineering. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2016, 69, 1137–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keikhosravani, P.; Maleki-Ghaleh, H.; Khosrowshahi, A.K.; Bodaghi, M.; Dargahi, Z.; Kavanlouei, M.; Khademi-Azandehi, P.; Fallah, A.; Beygi-Khosrowshahi, Y.; Siadati, M.H. Bioactivity and Antibacterial Behaviors of Nanostructured Lithium-Doped Hydroxyapatite for Bone Scaffold Application. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spuch, C.; López-García, M.; Rivera-Baltanás, T.; Rodrígues-Amorím, D.; Olivares, J.M. Does Lithium Deserve a Place in the Treatment Against COVID-19? A Preliminary Observational Study in Six Patients, Case Report. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 557629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, X.; Xu, W.; Li, M.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, Y.S.; Ding, J.; Chen, X. Antiviral Biomaterials. Matter 2021, 4, 1892–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokubo, T.; Kushitani, H.; Sakka, S.; Kitsugi, T.; Yamamuro, T. Solutions Able to Reproduce in Vivo Surface-structure Changes in Bioactive Glass-ceramic A-W3. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1990, 24, 721–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, K.; Zhang, J.; Shi, H.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; Li, H.; Ye, J. Preparation and in Vitro Cell-Biological Performance of Sodium Alginate/Nano-Zinc Silicate Co-Modified Calcium Silicate Bioceramics. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 8329–8339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, E.; Yanni, T.; Jamshidi, P.; Grover, L.M. Inorganic Cements for Biomedical Application: Calcium Phosphate, Calcium Sulphate and Calcium Silicate. Adv. Appl. Ceram. 2015, 114, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.-T.; Chang, J. Silicate Bioceramics for Bone Tissue Regeneration. J. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 28, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xiao, Y.; Song, W.; Ye, L.; Yang, C.; Xing, Y.; Yuan, Z. Clinical Application of Calcium Silicate-Based Bioceramics in Endodontics. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 21, 853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srinath, P.; Abdul Azeem, P.; Venugopal Reddy, K. Review on Calcium Silicate-Based Bioceramics in Bone Tissue Engineering. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2020, 17, 2450–2464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.-J.; Lin, M.; Zhang, L.; Gou, Z.-R. Progress of Calcium Sulfate and Inorganic Composites for Bone Defect Repair. J. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 28, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rojas, F.; Borrero-López, Ó.; Sánchez-González, E.; Hoffman, M.; Guiberteau, F. On the Durability of Zirconia-Reinforced Lithium Silicate and Lithium Disilicate Dental Ceramics under Severe Contact. Wear 2022, 508–509, 204460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaka, S.E.; Elnaghy, A.M. Mechanical Properties of Zirconia Reinforced Lithium Silicate Glass-Ceramic. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 908–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.R.; Kang, J.H.; Yun, Y.N.; Park, S.W.; Lim, H.P.; Yun, K.D.; Jang, W.H.; Lee, D.J.; Park, C. Ceramic 3D Printing Using Lithium Silicate Prepared by Sol-Gel Method for Customizing Dental Prosthesis with Optimal Translucency. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 39788–39799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hahn, S.H.; Ren, M.; Thiruvillamalai, M.; Gross, T.M.; Du, J.; van Duin, A.C.T.; Kim, S.H. Searching for Correlations between Vibrational Spectral Features and Structural Parameters of Silicate Glass Network. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 103, 3575–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Kong, L.; Wang, W.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, H. Microstructure, Dielectric Properties and Bond Characteristics of Lithium Aluminosilicate Glass-Ceramics with Various Li/Na Molar Ratio. Crystals 2023, 13, 1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litasov, K.D.; Podgornykh, N.M. Raman Spectroscopy of Various Phosphate Minerals and Occurrence of Tuite in the Elga IIE Iron Meteorite. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2017, 48, 1518–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetha, R.; Priyangha, P.T. The Synthesis and Characterization of Selenium-Doped Bioglass. Cureus 2024, 16, e61728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodaei, M.; Nejatidanesh, F.; Savabi, O.; Tayebi, L. Lithium Metasilicate Glass-Ceramic Fabrication Using Spark Plasma Sintering. Dent. Res. J. 2023, 20, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaniboni, J.F.; Silva, A.S.; Silva, A.M.; Besegato, J.F.; Muñoz-Chávez, O.F.; de Campos, E.A. Microstructural and Flexural Strength of Various CAD-CAM Lithium Disilicate Ceramics. J. Prosthodont. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonomura, H.; Ozaki, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Sakurai, Y. Natural Graphite Coated with Li2SiO3–Li2CO3-CNTs Composite by Solvothermal Synthesis for High-Performance Sulfide-Based All-Solid-State Lithium Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2025, 204, 112749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, H.; Sun, J.; Liu, C.; Xian, W.; Wang, W.; Luo, L.; Li, S. Study on Sintering Behavior and Properties of Lithium Slag-Based Foamed Ceramics. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 617, 122499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Zhu, X.; Xu, Z.; Ma, Y.; Lu, Y.; Shu, Y.; Yang, L.; Guo, S.; Ye, X.; Chen, K. Microwave Sintering of Lithium Hydride by Powder Metallurgy: Grain Growth Kinetics and Densification Mechanism. Adv. Powder Technol. 2025, 36, 104867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öhman-Mägi, C.; Holub, O.; Wu, D.; Hall, R.M.; Persson, C. Density and Mechanical Properties of Vertebral Trabecular Bone—A Review. JOR Spine 2021, 4, e1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zioupos, P.; Cook, R.B.; Hutchinson, J.R. Some Basic Relationships between Density Values in Cancellous and Cortical Bone. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 1961–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Wen, C.; Wu, J.; Wen, N.; Sa, B.; Zhang, T. Mechanical and Bioactive Properties of Lithium Disilicate Glass-Ceramic Mixtures Synthesized by Two Different Methods. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2019, 509, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, I.Y.; Raybolt dos Santos, A.; Costa, A.M.; Mavropoulos, E.; Tanaka, M.N.; Prado da Silva, M.H.; de Souza Camargo, S. In Vitro Assessment of Zinc Apatite Coatings on Titanium Surfaces. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 15502–15510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, C.R.D.; Santiago, A.A.G.; Vasconcelos, R.C.; Paiva, D.F.F.; Pirih, F.Q.; Araújo, A.A.; Motta, F.V.; Bomio, M.R.D. Study of Microstructural, Mechanical, and Biomedical Properties of Zirconia/Hydroxyapatite Ceramic Composites. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 12376–12386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzel, R.; Brauer, D.S. Apatite Formation of Substituted Bioglass 45S5: SBF vs. Tris. Mater. Lett. 2019, 257, 126760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, A.; Balossier, G.; Kannan, S.; Michel, J.; Rebelo, A.H.S.; Ferreira, J.M.F. Development and in Vitro Characterization of Sol-Gel Derived CaO-P2O5-SiO2-ZnO Bioglass. Acta Biomater. 2007, 3, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joughehdoust, S.; Manafi, S. Synthesis and in Vitro Investigation of Sol-Gel Derived Bioglass-58S Nanopowders. Mater. Sci.-Pol. 2012, 30, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Tang, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Y. Influence of Lithium Ion Doping and Mitoxantrone Hydrochloride Loading on the Structure and in Vitro Biological Properties of Mesoporous Bioactive Glass Microspheres in the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 695, 134168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvamani, V.; Jeong, J.; Maruthamuthu, M.K.; Arulsamy, K.; Na, J.G.; Hong, S.H. Adsorption of Lithium on Cell Surface as Nanoparticles through Lithium Binding Peptide Display in Recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2023, 28, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajikarimlou, M.; Hunt, K.; Kirby, G.; Takallou, S.; Jagadeesan, S.K.; Omidi, K.; Hooshyar, M.; Burnside, D.; Moteshareie, H.; Babu, M.; et al. Lithium Chloride Sensitivity in Yeast and Regulation of Translation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 5730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, N.; Sadeeshkumar, H.; Sun, A.; Sudarsan, N.; Breaker, R.R. Lithium-Sensing Riboswitch Classes Regulate Expression of Bacterial Cation Transporter Genes. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 19145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekanska, E.; Stoddart, M.; Richards, R.; Hayes, J. In Search of an Osteoblast Cell Model for in Vitro Research. Eur. Cell Mater. 2012, 24, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.; Hermann, C.D.; Cheng, A.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Gittens, R.A.; Bird, M.M.; Walker, M.; Cai, Y.; Cai, K.; Sandhage, K.H.; et al. Role of A2β1 Integrins in Mediating Cell Shape on Microtextured Titanium Surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2015, 103, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekanska, E.M.; Stoddart, M.J.; Ralphs, J.R.; Richards, R.G.; Hayes, J.S. A Phenotypic Comparison of Osteoblast Cell Lines versus Human Primary Osteoblasts for Biomaterials Testing. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2014, 102, 2636–2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lüthen, F.; Lange, R.; Becker, P.; Rychly, J.; Beck, U.; Nebe, J.G.B. The Influence of Surface Roughness of Titanium on Β1- and Β3-Integrin Adhesion and the Organization of Fibronectin in Human Osteoblastic Cells. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2423–2440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saldaña, L.; Bensiamar, F.; Boré, A.; Vilaboa, N. In Search of Representative Models of Human Bone-Forming Cells for Cytocompatibility Studies. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 4210–4221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nebe, J.G.B.; Luethen, F.; Lange, R.; Beck, U. Interface Interactions of Osteoblasts with Structured Titanium and the Correlation between Physicochemical Characteristics and Cell Biological Parameters. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 567–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| BG Type * | Composition (wt%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | P2O5 | Li2O | CaO | Na2O | |

| BG | 47.5 | 5 | 0 | 23.75 | 23.75 |

| BG-2.5Li | 47.5 | 5 | 2.5 | 21.25 | 23.75 |

| BG-5Li | 47.5 | 5 | 5 | 18.75 | 23.75 |

| BG-10Li | 47.5 | 5 | 10 | 13.75 | 23.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fotu, M.; Nicoară, A.I.; Manolache, Ș.; Bacalum, M.; Moisa, R.; Trușcă, R.D.; Isopencu, G.O.; Busuioc, C. Bioceramics Based on Li-Modified Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Materials 2026, 19, 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010153

Fotu M, Nicoară AI, Manolache Ș, Bacalum M, Moisa R, Trușcă RD, Isopencu GO, Busuioc C. Bioceramics Based on Li-Modified Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Materials. 2026; 19(1):153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010153

Chicago/Turabian StyleFotu, Mihai, Adrian Ionuț Nicoară, Ștefan Manolache, Mihaela Bacalum, Roberta Moisa (Stoica), Roxana Doina Trușcă, Gabriela Olimpia Isopencu, and Cristina Busuioc. 2026. "Bioceramics Based on Li-Modified Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration" Materials 19, no. 1: 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010153

APA StyleFotu, M., Nicoară, A. I., Manolache, Ș., Bacalum, M., Moisa, R., Trușcă, R. D., Isopencu, G. O., & Busuioc, C. (2026). Bioceramics Based on Li-Modified Bioactive Glasses for Bone Tissue Regeneration. Materials, 19(1), 153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010153