Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete and Connection Strategies for Large-Scale Reusable Formwork in Digital Construction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials and Mix Proportion

2.2. Specimen Description

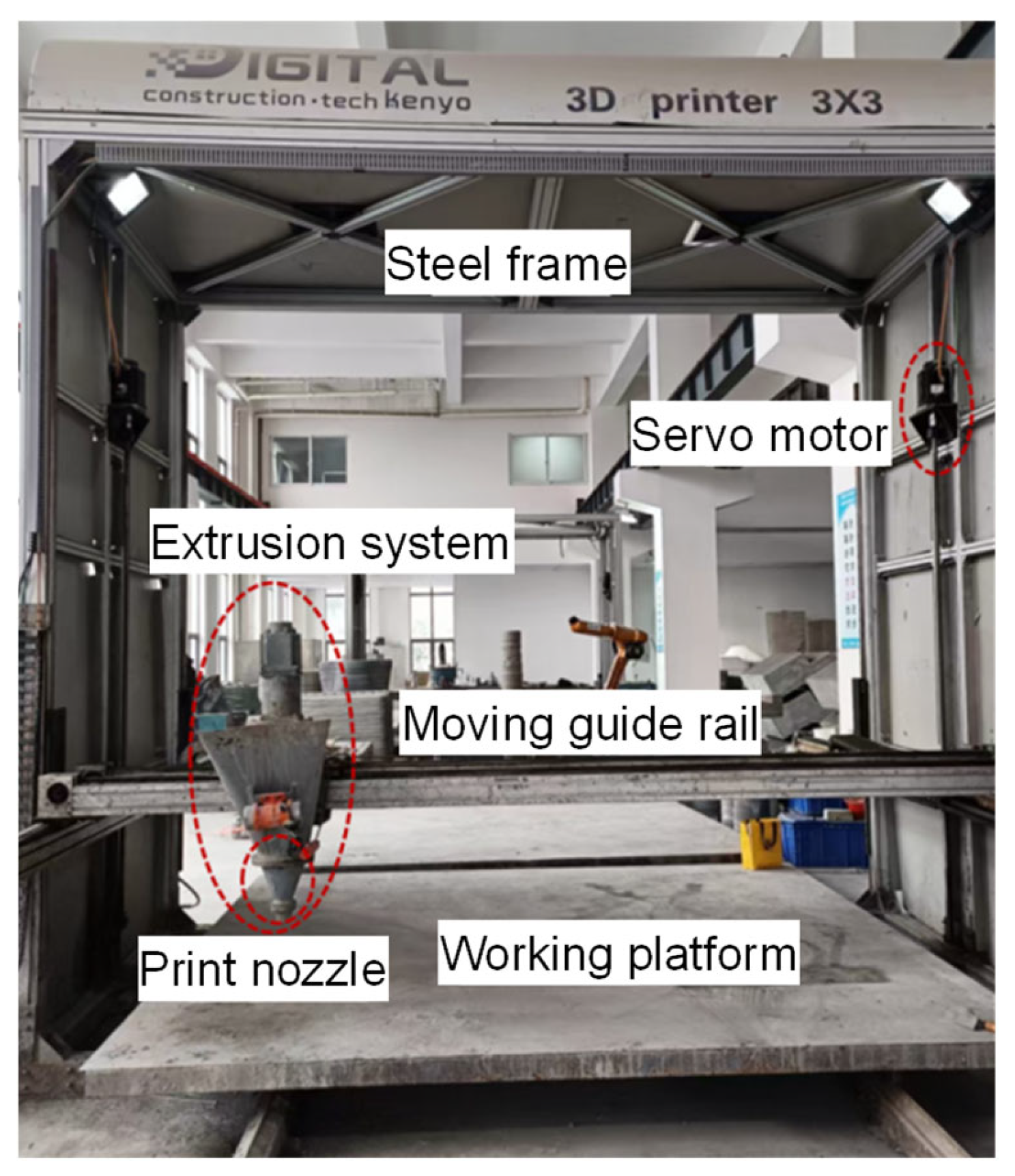

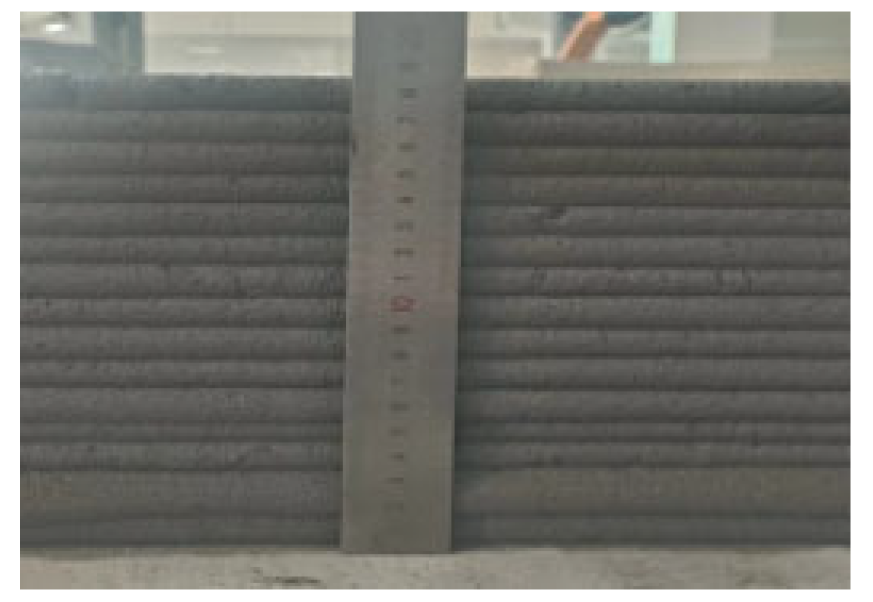

2.3. Three-Dimensional Concrete Printing

2.4. Experimental Set-Up and Measurements

2.4.1. Mechanical Property Testing

2.4.2. Anisotropy Evaluation

2.4.3. Carbon Emission Calculation

2.4.4. Connection Strategies for Printed Formwork

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.1.1. Compressive Strength

3.1.2. Splitting Tensile Strength

3.1.3. Flexural Strength

3.2. Carbon Emissions of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete

3.2.1. Raw Material Production Stage

3.2.2. Raw Material Transportation Stage

3.2.3. Concrete Mixing Stage

3.2.4. Carbon Emission Results and Analysis

3.3. Comprehensive Performance Evaluation of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete Based on TOPSIS

4. Finite Element Modelling

4.1. Model Description

4.2. Strength Verification

4.3. Stiffness Verification

4.4. Simulation Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The mixtures showed clear mechanical anisotropy: compressive strength was highest in the X-direction, splitting and flexural strength peaked in the Z-direction, while the lowest values appeared in the X-direction. Higher steel slag and iron tailings sand replacement ratios led to notable strength improvements.

- (2)

- Carbon emissions are dominated by raw material production, while transportation and mixing contribute minimally. Replacing cement with steel slag and natural sand with tailings sand is effective for emission reduction.

- (3)

- Both the 0.3-0.2-0.6% and 0.3-0.4-0.3% mixtures demonstrate excellent overall performance through the coefficient-of-variation TOPSIS method. The 0.3-0.4-0.3% mixture is recommended for practical application in 3D printed low-carbon concrete, as it achieves a favourable balance between mechanical strength and low-carbon objectives by increasing iron tailings sand utilization while reducing fibre content.

- (4)

- All three connection strategies meet strength requirements, but Strategy 1 fails the deflection limit. Strategies 2 and 3 satisfy stiffness criteria, with Strategy 3 showing the smallest deformation. A combined use of Strategies 2 and 3 further enhances system stability, offering practical guidance for engineering application of reusable 3D-printed formwork.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Warnke, P.H.; Seitz, H.; Warnke, F.; Becker, S.T.; Sivananthan, S.; Sherry, E.; Liu, Q.; Wiltfang, J.; Douglas, T. Ceramic scaffolds produced by computer-assisted 3D printing and sintering: Characterization and biocompatibility investigations. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B 2010, 93, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Gemeda, H.B.; Duoss, E.B.; Spadaccini, C.M. Toward multiscale, multimaterial 3D printing. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2314204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Buswell, R.; da Silva, W.R.L.; Wang, L.; Xu, J.; Jones, S.Z. Technology readiness: A global snapshot of 3D concrete printing and the frontiers for development. Cem. Concr. Res. 2022, 156, 106774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasani, A.; Dorafshan, S. Transforming construction? Evaluation of the state of structural 3D concrete printing in research and practice. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 438, 137027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, A.K.; Alqamish, H.H.; Khaldoune, A.; Alhaidary, H.; Shirvanimoghaddam, K. Framework of 3D concrete printing potential and challenges. Buildings 2023, 13, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, S.; Basavaraj, A.S.; Rahul, A.V.; Santhanam, M.; Gettu, R.; Panda, B.; Schlangen, E.; Chen, Y.; Copuroglu, O.; Ma, G.; et al. Sustainable materials for 3D concrete printing. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 122, 104156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Reiner, D.M.; Yang, F.; Cui, C.; Meng, J.; Shan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tao, S.; Guan, D. Projecting future carbon emissions from cement production in developing countries. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Han, S.; Lin, Y.; Wei, Y.; Geng, N. Study on the mechanical properties of recycled aggregate concrete modified by bamboo fiber-nano SiO2 synergistic effect. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 494, 143415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, G.; Chen, S. Experimental study on the feasibility of using innovative biomass bamboo aggregate for cementitious materials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 217, 118864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, H.; Zhu, J.; Yang, X. Analysis of mechanical properties and failure mechanism of bamboo aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 422, 135835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Ding, M.; Wang, L.; Wei, Y. Experimental study on mechanical properties of raw bamboo fibre-reinforced concrete. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e04003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Zhu, B.; Li, X.; Meng, L.; Cai, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J. Investigation of the rheological and mechanical properties of 3D printed eco-friendly concrete with steel slag. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Zhu, H.; Zhai, M.; Wu, Q.; Yin, Z.; Qian, H.; Hua, S. Stability of steel slag as fine aggregate and its application in 3D printing materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 123938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Wang, J.; Zhan, X.; Zhao, P.; Xie, Z.; Wang, S.; Yue, Z. Effects of retarders on the rheological properties of coal fly ash/superfine iron tailings-based 3D printing geopolymer: Insight into the early retarding mechanism. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heraiz, H.; Li, J.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, D.; Hu, Y.; Mu, X.; Baras, A.; Liu, J.; Ni, W.; Hitch, M. The Utilization of Slag, Steel Slag, and Desulfurization Gypsum as Binder Systems in UHPC with Iron Tailings and Steel Fibers—A Review. Minerals 2025, 15, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Qu, F.; Li, W. Advancing circular economy and construction sustainability: Transforming mine tailings into high-value cementitious and alkali-activated concrete. Npj Mater. Sustain. 2025, 3, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, N.; Yuan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Zhang, Y. Preparation and microstructural characterization of a novel 3D printable building material composed of copper tailings and iron tailings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boutemy, C.; Lebée, A.; Skouras, M.; Mimram, M.; Baverel, O. Reusable Inflatable Formwork for complex shape concrete shells. In Design Modelling Symposium Berlin; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 198–210. [Google Scholar]

- Liebringshausen, A.; Eversmann, P.; Göbert, A. Circular, zero waste formwork-Sustainable and reusable systems for complex concrete elements. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 107696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emami, N. Employing additive manufacturing to create reusable TPU formworks for casting topologically optimized facade panels. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 75, 106946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T. Experimental Study on Cast-in-Situ Concrete Composite Beam with Permanent Formwork; Jilin University: Changchun, China, 2012. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xun, Y.; Zhi, Z.; Zhang, Q. Experimental research on flexural behavior of reinforced concrete beams strengthened with textile reinforced concrete sheets. J. Build. Struct. 2010, 31, 70–76. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jipa, A.; Giacomarra, F.; Giesecke, R.; Chousou, G.; Pacher, M.; Dillenburger, B.; Lomaglio, M.; Leschok, M. 3D-printed formwork for bespoke concrete stairs: From computational design to digital fabrication. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual ACM Symposium on Computational Fabrication, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 16–18 June 2019; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, T.W.; Ali, A.A.M.; Zidan, R.S. Properties of high strength polypropylene fiber concrete containing recycled aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 241, 118010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.V.; Cu, Y.T.H.; Le, C.V.H. Rheology and shrinkage of concrete using polypropylene fiber for 3D concrete printing. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 44, 103400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 17671-2021; Test Method of Cement Mortar Strength (ISO Method). Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Kazemian, A.; Yuan, X.; Cochran, E.; Khoshnevis, B. Cementitious materials for construction-scale 3D printing: Laboratory testing of fresh printing mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 145, 639–647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaeb, Z.; AlSakka, F.; Hamzeh, F. 3D concrete printing: Machine design, mix proportioning, and mix comparison between different machine setups. In 3D Concrete Printing Technology; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso-Cañon, S.; Alonso-Estébanez, A.; Yoris-Nobile, A.I.; Brunčič, A.; Blanco-Fernandez, E.; Castanon-Jano, L. Rheological parameter ranges for 3D printing sustainable mortars using a new low-cost rotational rheometer. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 140, 1945–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T/CBMF 183-2022; Test Methods for Basic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Concrete. China Construction Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Ye, J.; Cui, C.; Yu, J.; Yu, K.; Dong, F. Effect of polyethylene fiber content on workability and mechanical-anisotropic properties of 3D printed ultra-high ductile concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 281, 122586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Li, Z.; Wang, L.; Wang, F.; Sanjayan, J. Mechanical anisotropy of aligned fiber reinforced composite for extrusion-based 3D printing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 202, 770–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jia, L.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ma, L.; Chen, C.; Banthia, N.; Zhang, Y. Mechanical anisotropy evolution of 3D-printed alkali-activated materials with different GGBFS/FA combinations. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 50, 104126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zhang, J.; Lu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Zhang, C. Research on carbon emission calculation and low carbon realization method of concrete production. Mod. Chem. Res. 2025, 49–51. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Paul, S.C.; Tan, M.J. Anisotropic mechanical performance of 3D printed fiber reinforced sustainable construction material. Mater. Lett. 2017, 209, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, G.; Zhang, J.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Sun, J. Mechanical characterization of 3D printed anisotropic cementitious material by the electromechanical transducer. Smart Mater. Struct. 2018, 27, 075036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yan, P.; Yang, J.; Zhang, B. Influence of steel slag on mechanical properties and durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 47, 1414–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 51366-2019; Standard for Building Carbon Emission Calculation. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- Long, W.J.; Wu, Z.; Khayat, K.H.; Wei, J.; Dong, B.; Xing, F.; Zhang, J. Design, dynamic performance and ecological efficiency of fiber-reinforced mortars with different binder systems: Ordinary Portland cement, limestone calcined clay cement and alkali-activated slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 337, 130478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Zhang, J.; Yan, C.; Yin, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, S. Hydration characteristics of low carbon cementitious materials with multiple solid wastes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 322, 126366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Ma, M.; He, X.; Zheng, Z.; Su, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhao, H. Effect of wet-grinding steel slag on the properties of Portland cement: An activated method and rheology analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 286, 122823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, W.J.; Lin, C.; Tao, J.L.; Ye, T.H.; Fang, Y. Printability and particle packing of 3D-printable limestone calcined clay cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 282, 122647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Yu, L. Servicelife period-based carbon emission computing model for ready-mix concrete. Coal Ash 2011, 23, 42–46. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Artenian, A.; Sadeghpour, F.; Teizer, J. A GIS framework for reducing GHG emissions in concrete transportation. In Proceedings of the Construction Research Congress 2010, Innovation for Reshaping Construction Practice, Banff, AB, Canada, 8–10 May 2010; pp. 1557–1566. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, P. A novel coordinated TOPSIS based on coefficient of variation. Mathematics 2019, 7, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Wang, Q.; Wei, Y.; Pan, J.; Ye, H. Sustainable Bio-Gelatin Fiber-Reinforced Composites with Ionic Coordination: Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50666-2011; Code for Construction of Concrete Structures. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- GB 50204-2002; Code for Acceptance of Constructional Quality of Concrete Structures. China Architecture and Building Press: Beijing, China, 2010.

| Fibre | Density (g/cm3) | Length (mm) | Average Diameter (µm) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Rupture Elongation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP | 0.91 | 6 | 18 | 500 | 5 | 15 |

| Mix No. | OPC | SS | FA | SF | RS | ITS | PP | W | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0% | 0.3 | 0.4% |

| 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.3% | 0.3 | 0.4% |

| 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.9% | 0.3 | 0.4% |

| 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 0.3 | 0.6% | 0.3 | 0.4% |

| 0.3-0.4-0.3% | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 0.6 | 0.3% | 0.3 | 0.4% |

| Mix No. | 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.3-0.4-0.3% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extrudability test | Appearance |  |  |  |  |  |

| Width | 66 mm | 59 mm | 62 mm | 61 mm | 63 mm | |

| Buildability testing | Appearance |  |  |  |  |  |

| Height | 184.2 mm | 178.8 mm | 183.1 mm | 182.3 mm | 183.0 mm | |

| Average deformation rate | 2.3% | 0.6% | 1.7% | 1.3% | 1.7% | |

| Mix No. | OPC (kg) | FA (kg) | SS (kg) | SF (kg) | RS (kg) | ITS (kg) | PP (kg) | SP (kg) | Carbon Emissions (kgCO2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.2 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.0016 | 0.197 |

| 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.162 |

| 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0005 | 0.0016 | 0.130 |

| 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.0003 | 0.0016 | 0.127 |

| 0.3-0.4-0.3% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.125 |

| Raw Material | OPC | FA | SS | SF | RS | ITS | PP | SP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport distance (km) | 30 | 30 | 20 | 30 | 50 | 60 | 20 | 20 |

| Carbon emission factor (10−4 kgCO2/kg × km) | 1.1 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 1.11 | 2.35 | 2.35 | 2.35 |

| Mix No. | OPC (kg) | FA (kg) | SS (kg) | SF (kg) | RS (kg) | ITS (kg) | PP (kg) | SP (kg) | Carbon Emissions (kgCO2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.2 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0 | 0.0016 | 0.0063 |

| 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.24 | 0.36 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0084 |

| 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0 | 0.0005 | 0.0016 | 0.0054 |

| 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.0003 | 0.0016 | 0.0064 |

| 0.3-0.4-0.3% | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.0002 | 0.0016 | 0.0075 |

| Mix No. | Raw Material Production (C11) | Raw Material Transportation (C12) | Concrete MIXING Process (C13) | Concrete Production (C1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.197 | 0.0063 | 0.00121 | 0.20451 |

| 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.162 | 0.0084 | 0.00121 | 0.17161 |

| 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.130 | 0.0054 | 0.00121 | 0.13661 |

| 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.127 | 0.0064 | 0.00121 | 0.13461 |

| 0.3-0.4-0.3% | 0.125 | 0.0075 | 0.00121 | 0.13371 |

| Evaluation Indicator | Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation CVj | Weight wj |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compressive strength (MPa) | 43.28 | 3.13 | 0.072 | 0.211 |

| Flexural strength (MPa) | 6.84 | 0.50 | 0.074 | 0.217 |

| Splitting tensile strength (MPa) | 3.07 | 0.10 | 0.034 | 0.100 |

| Carbon emissions (kgCO2/−1) | 6.59 | 1.05 | 0.161 | 0.472 |

| Mix No. | 0.1-0.2-0% | 0.2-0.6-0.3% | 0.3-0-0.9% | 0.3-0.2-0.6% | 0.3-0.4-0.3% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ci | 0.0023 | 0.4407 | 0.7745 | 0.8823 | 0.8803 |

| Ranking | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, B.; Qi, M.; Chen, W.; Pan, J. Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete and Connection Strategies for Large-Scale Reusable Formwork in Digital Construction. Materials 2026, 19, 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010145

Zhu B, Qi M, Chen W, Pan J. Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete and Connection Strategies for Large-Scale Reusable Formwork in Digital Construction. Materials. 2026; 19(1):145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010145

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Binrong, Miao Qi, Wei Chen, and Jinlong Pan. 2026. "Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete and Connection Strategies for Large-Scale Reusable Formwork in Digital Construction" Materials 19, no. 1: 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010145

APA StyleZhu, B., Qi, M., Chen, W., & Pan, J. (2026). Anisotropic Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Low-Carbon Concrete and Connection Strategies for Large-Scale Reusable Formwork in Digital Construction. Materials, 19(1), 145. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010145