Tensile and Structural Performance of Annealed 3D-Printed Polymer Composite Impellers for Pump-as-Turbine Applications in District Heating Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Design flexibility: The ability to create custom and complex shapes without the need for expensive molds;

- Prototyping speed: Reducing the time needed to transform an idea into a physical model;

- Cost reduction: Lower material consumption and reduced production waste.

- Material Modification: Incorporating additives or blending with other materials (like nylon, carbon fiber, or other polymers) to improve strength;

- Optimized Printing Parameters: Adjusting print settings such as layer height, infill density, print temperature, and print speed to produce stronger parts;

- Post-Processing Techniques: Methods like annealing (heat treatment) can increase crystallinity, resulting in higher strength and heat resistance;

- Using Higher-Quality Filament: Selecting premium filaments that have better fiber alignment and fewer impurities can lead to stronger printed parts.

2. Methodology for Tensile Testing of Temperature-Resistant Polymers

2.1. Filament Selection

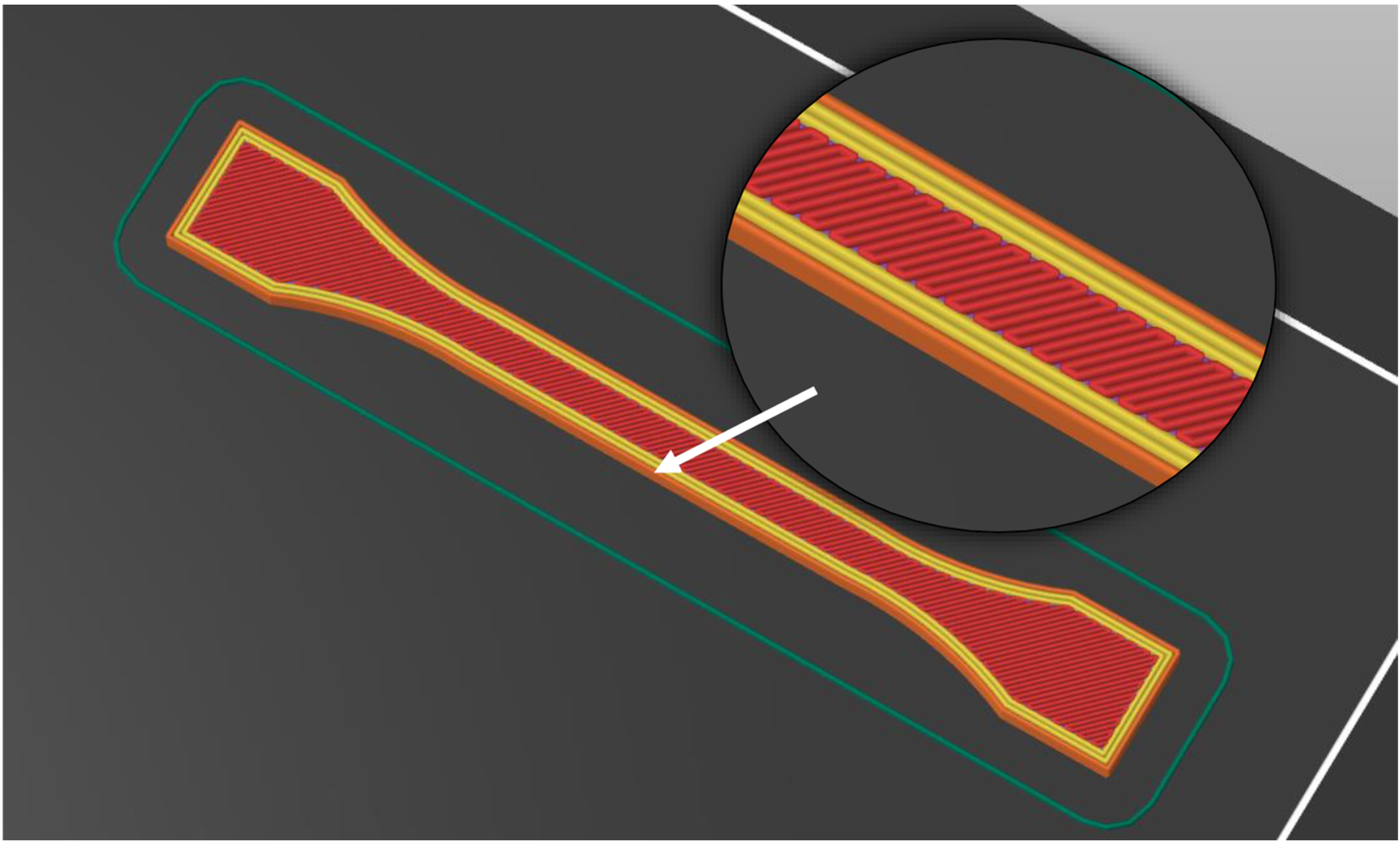

2.2. Test Specimens

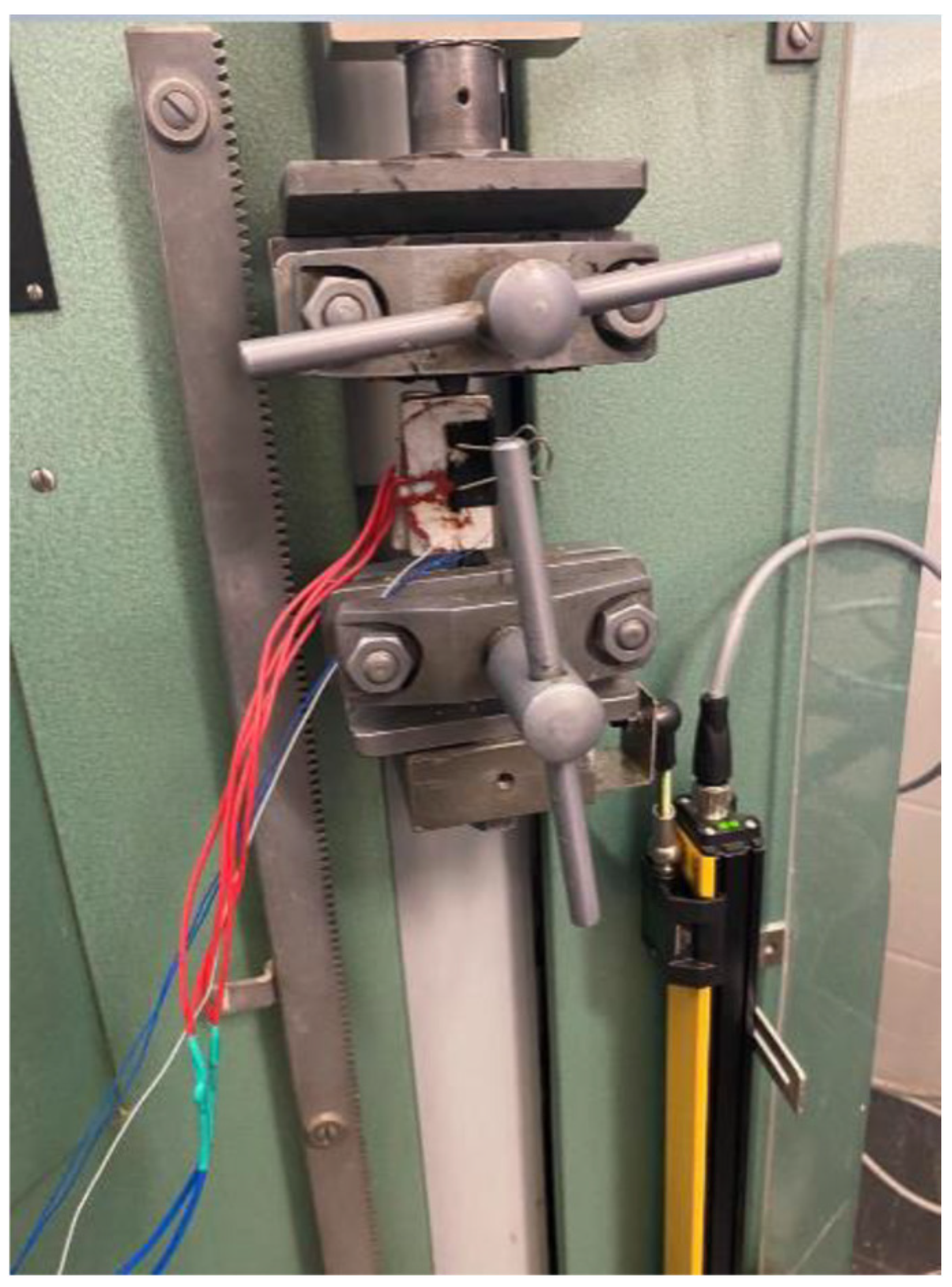

2.3. Testing Procedure

2.3.1. Specimen Preparation

2.3.2. Annealing of ePAHT-CF15 Samples

2.3.3. Specimen Heating

2.3.4. Tensile Testing

2.3.5. Repeatability and Validation

3. Material Strength Testing Results

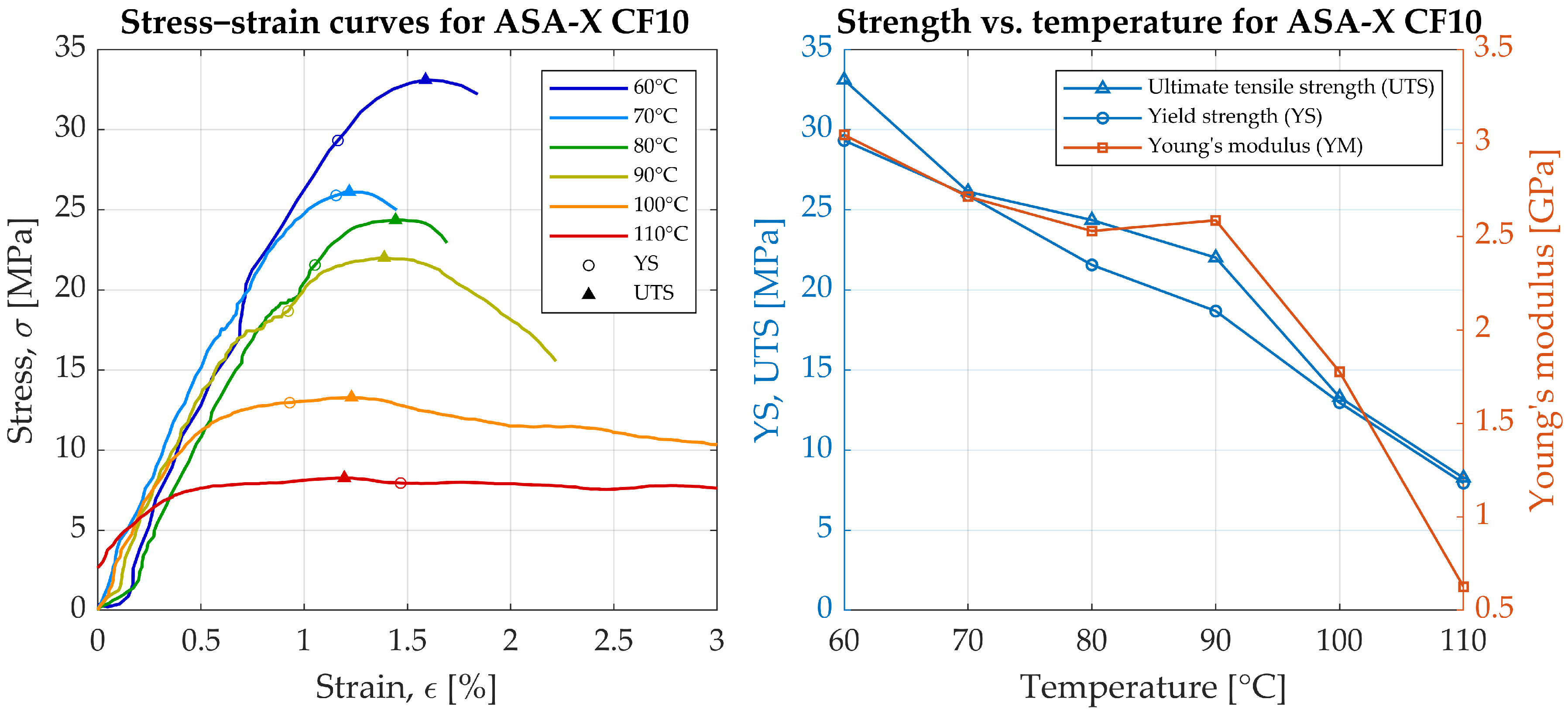

3.1. ASA-X CF10

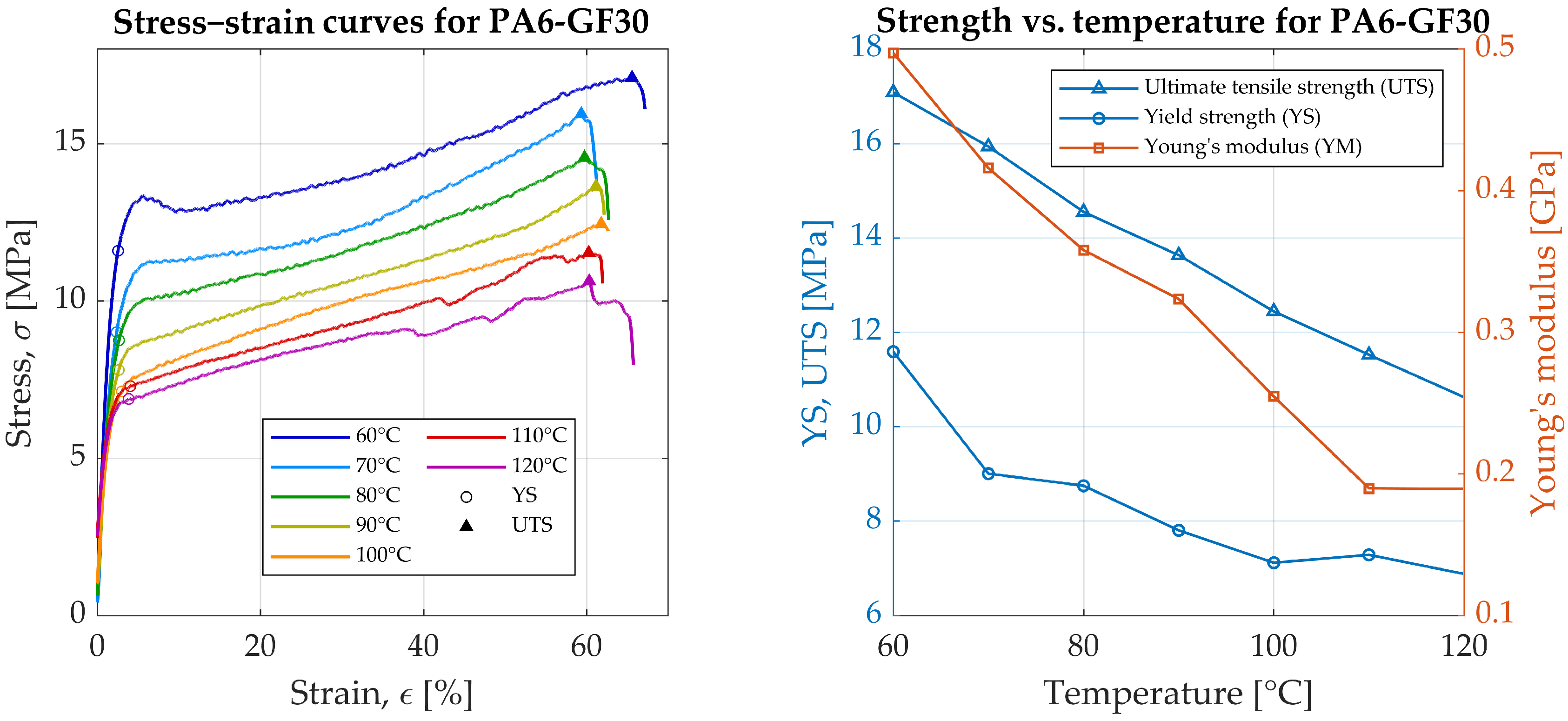

3.2. PA6-GF30

3.3. ePAHT-CF15

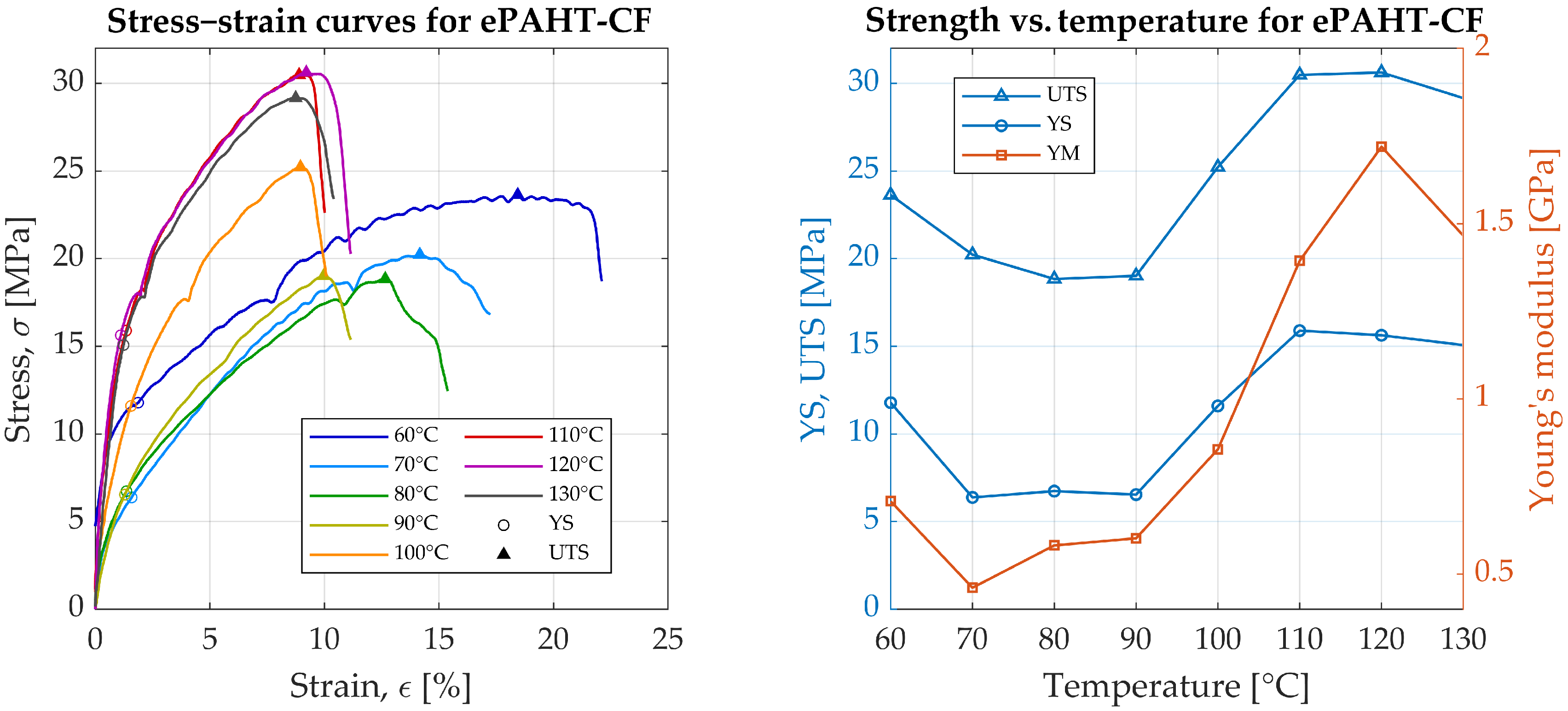

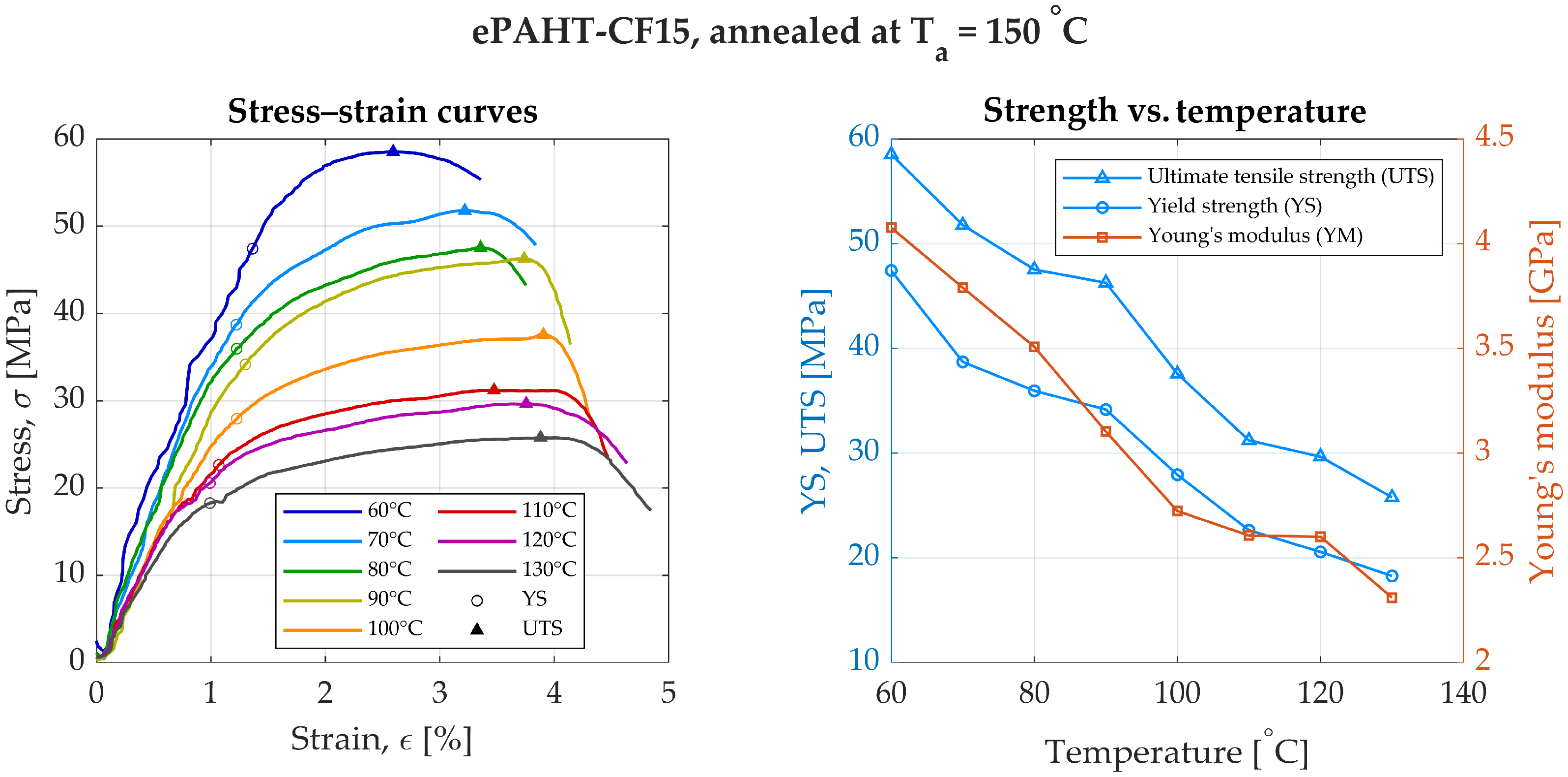

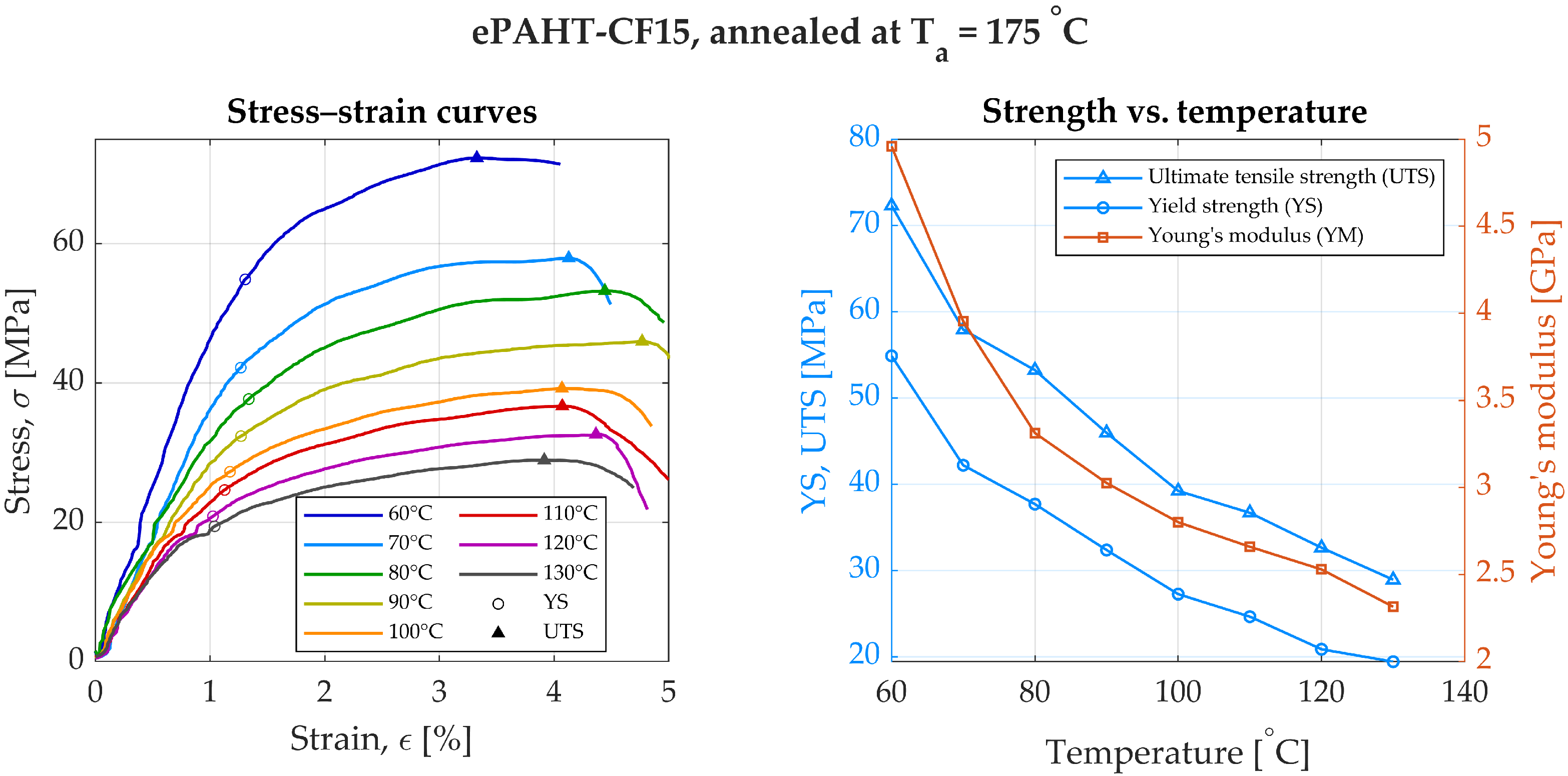

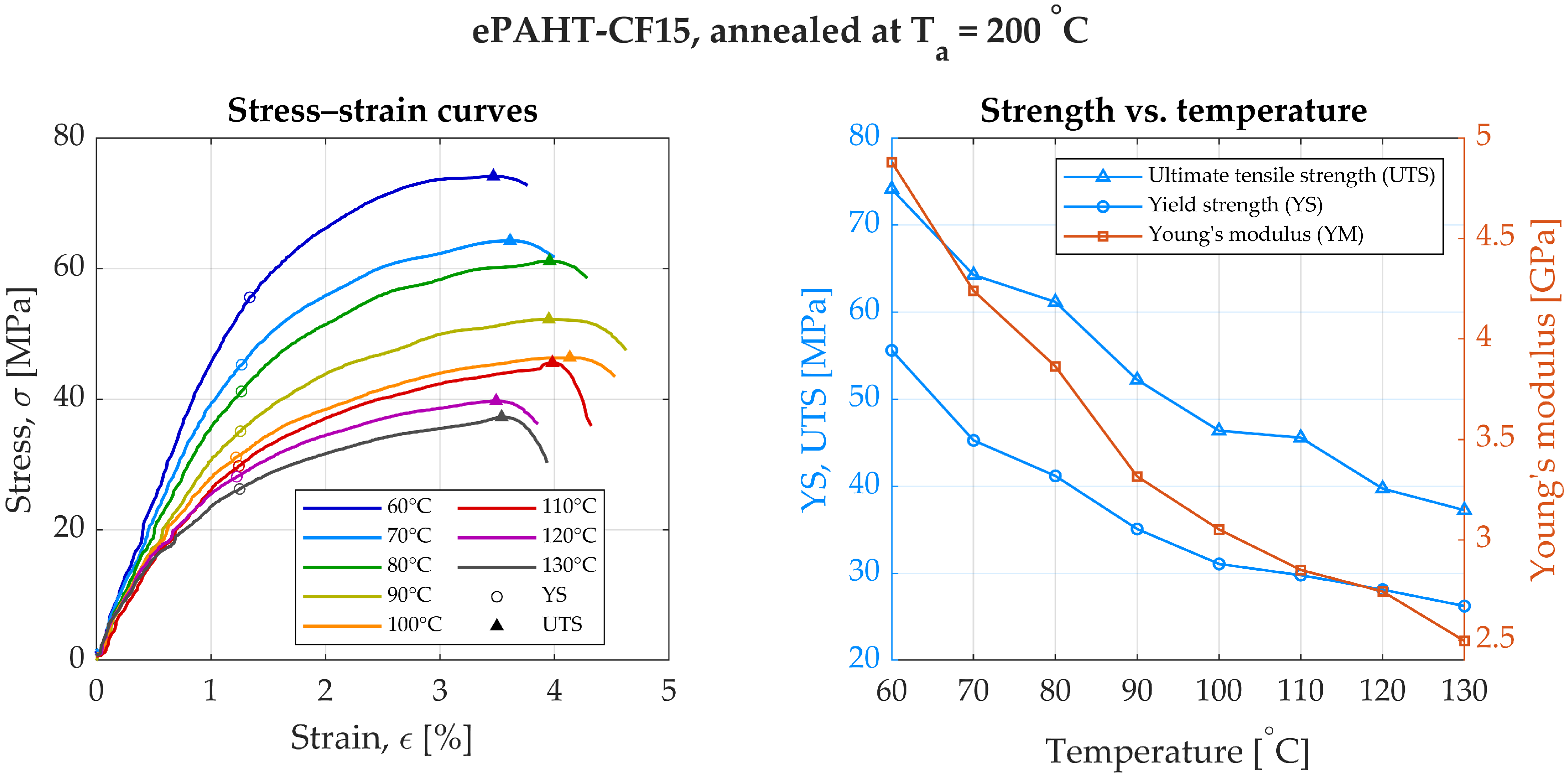

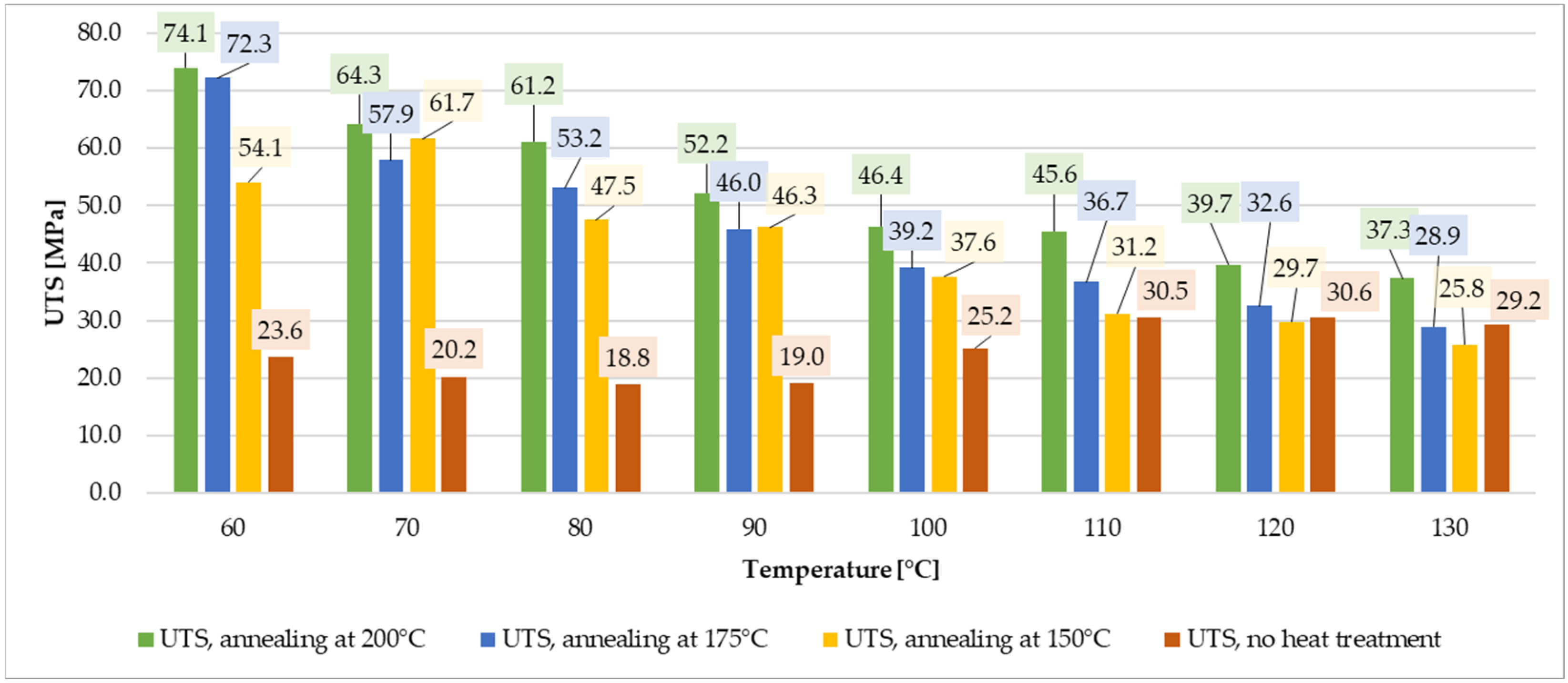

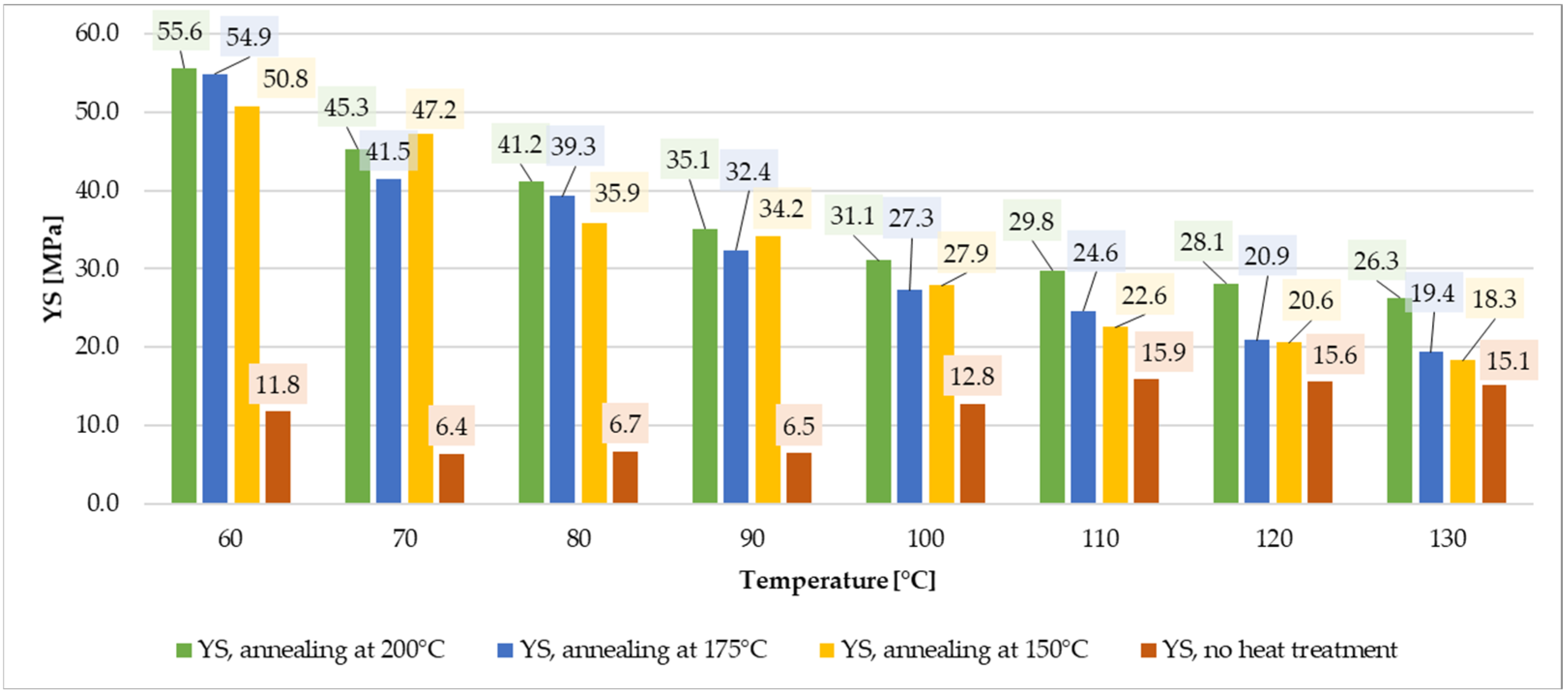

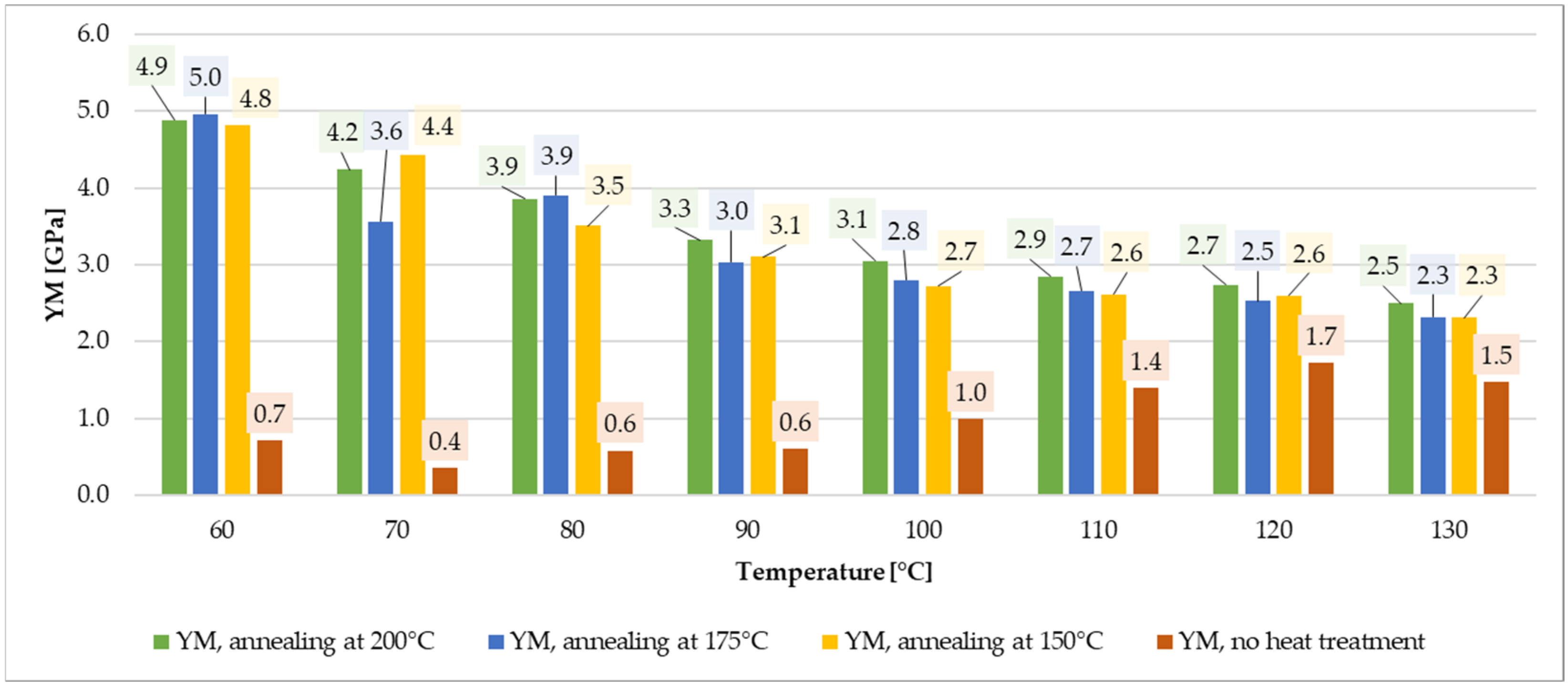

3.4. Annealed ePAHT-CF15

3.5. Strength Testing Summary

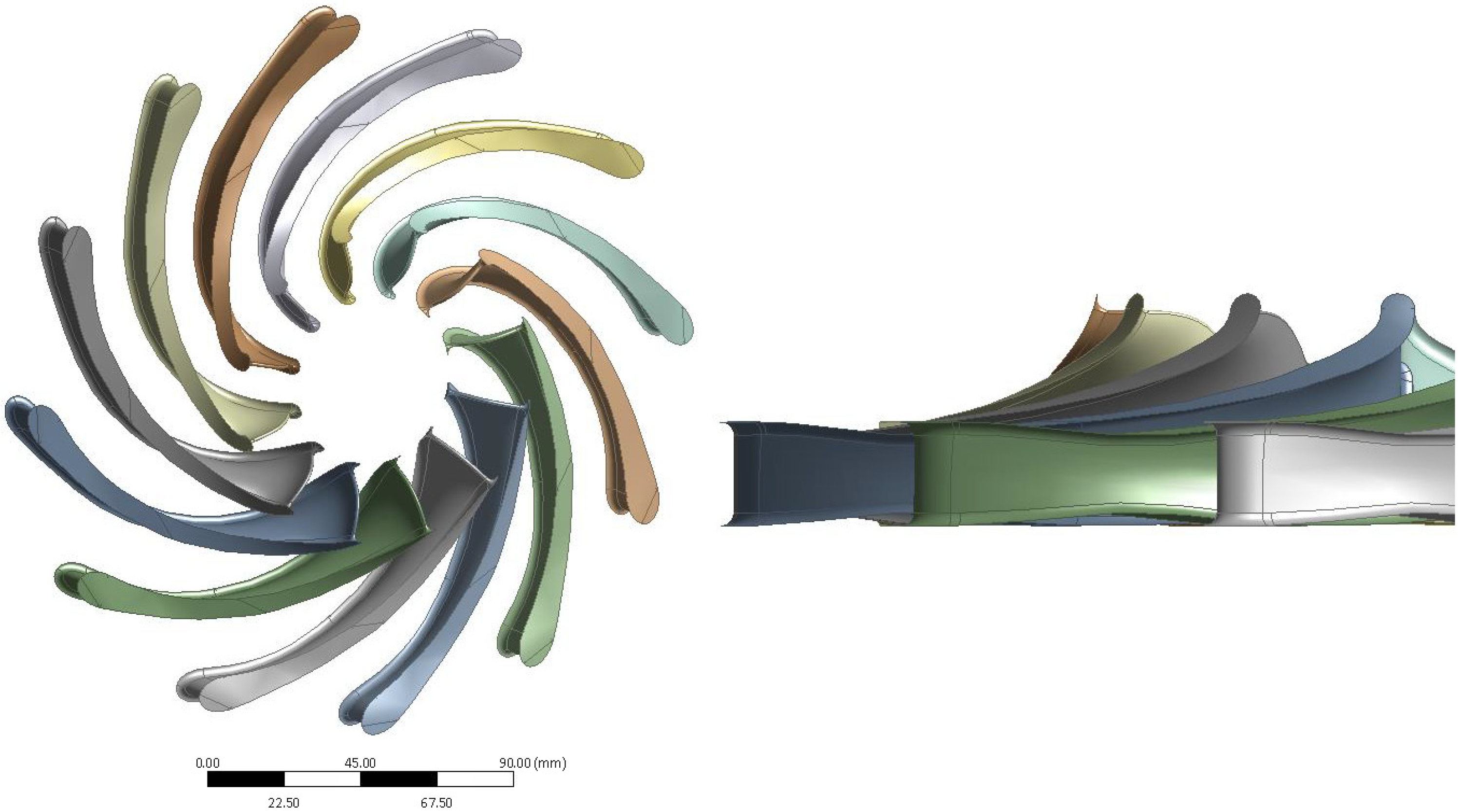

4. Pump as a Turbine Impeller Design

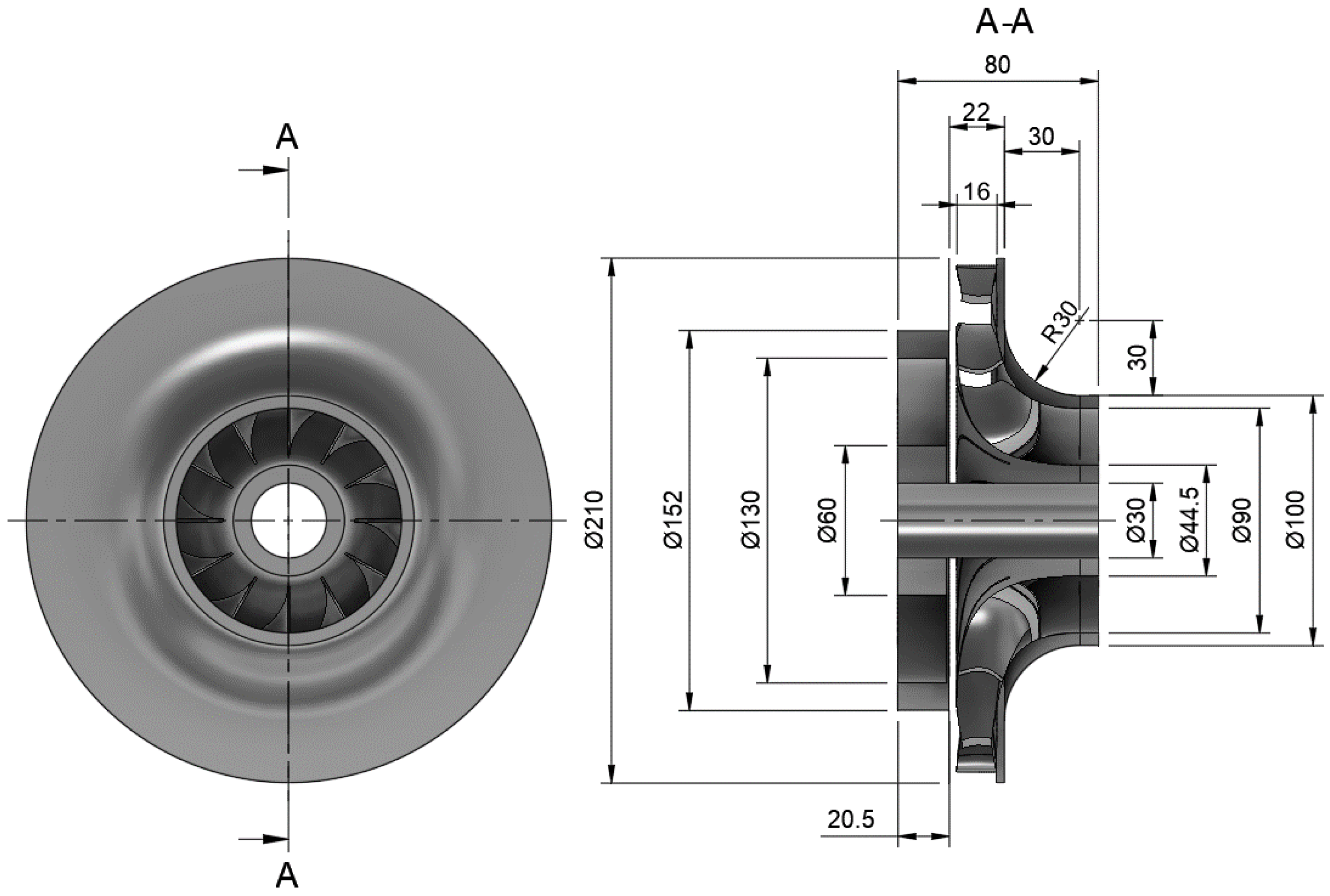

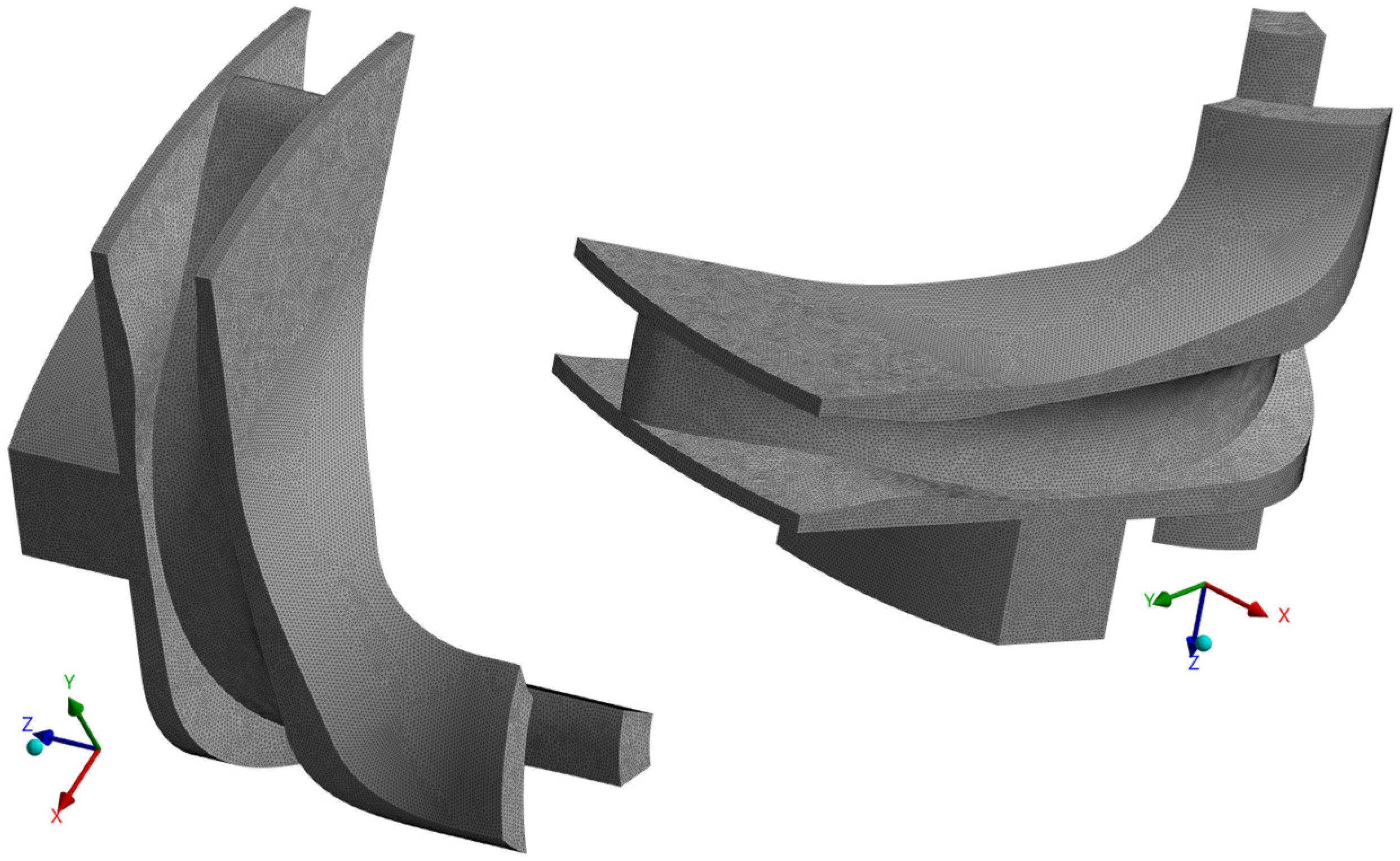

4.1. Impeller Design

- The radius of the blade at the hub/shroud interface was set to 2 mm;

- The blade thickness was designed in a hydrofoil shape, starting at 4 mm at the leading edge (LE), expanding to a maximum thickness of 6 mm, and tapering to 1 mm at the trailing edge (TE);

- Blade rounding was applied at the inlet with a radius of 2 mm and at the outlet with a radius of 1 mm. This design feature is known to enhance turbine efficiency by reducing flow separation and minimizing turbulence [42];

- A channel choke with a height of 12 mm was implemented at the radial inlet;

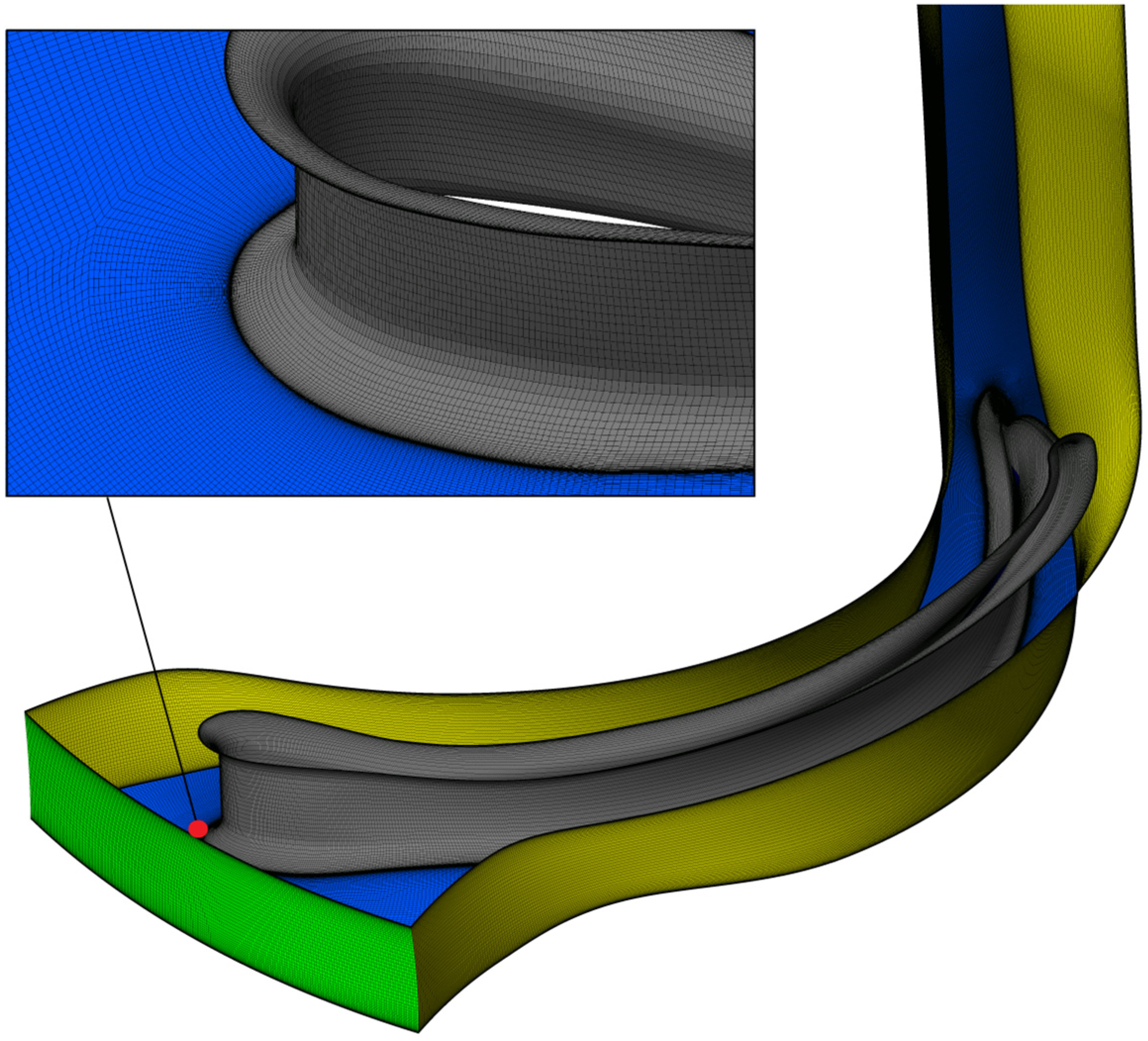

4.2. Mesh Generation

- Minimum orthogonality angle was equal to 31°.

- Maximum edge length ratio was lower than 200.

- Element volume ratio was lower than 2.6.

- Skewness was better than 0.81.

- First element height was equal to 4 μm.

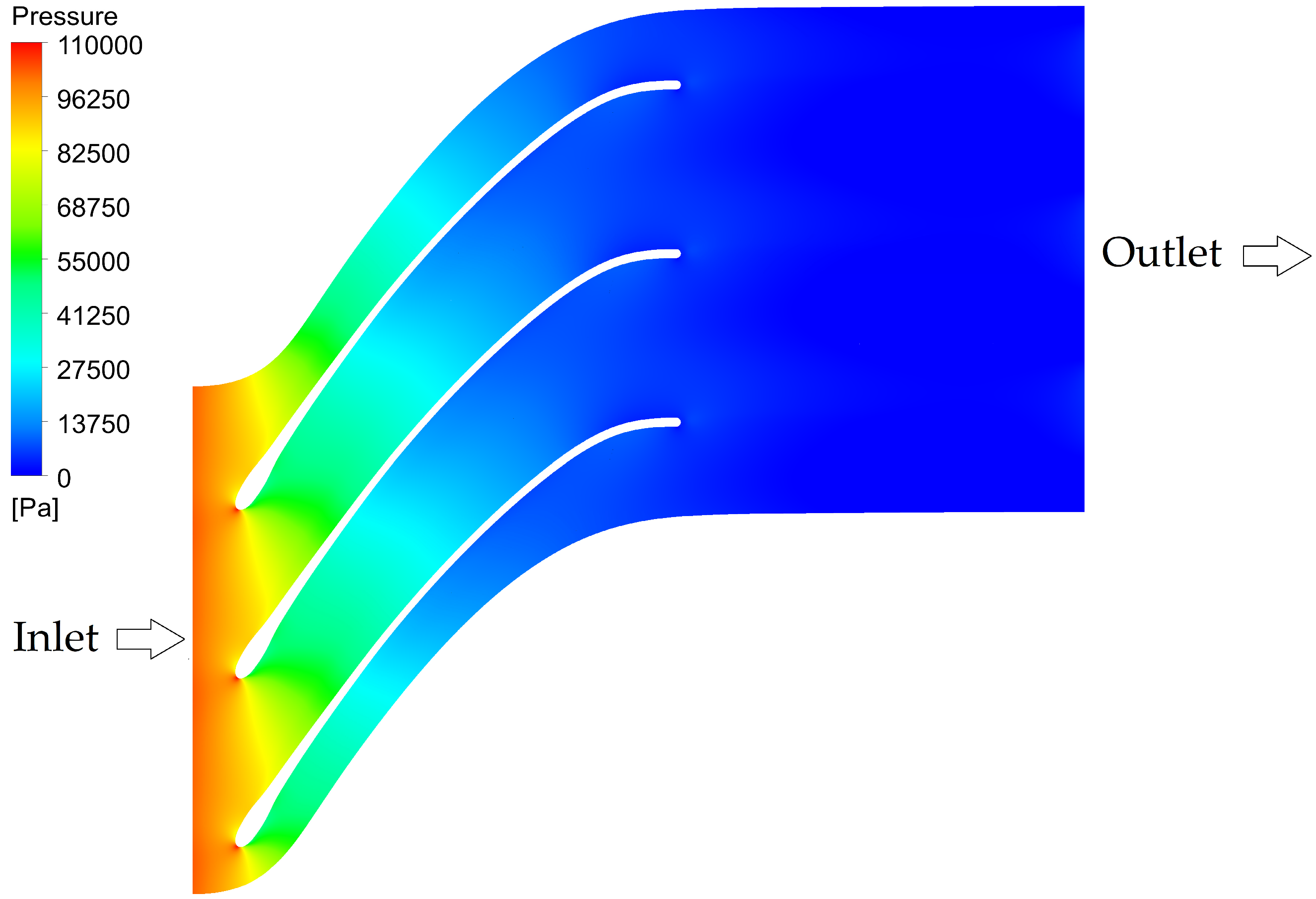

4.3. Boundary Conditions and CFD Simulation

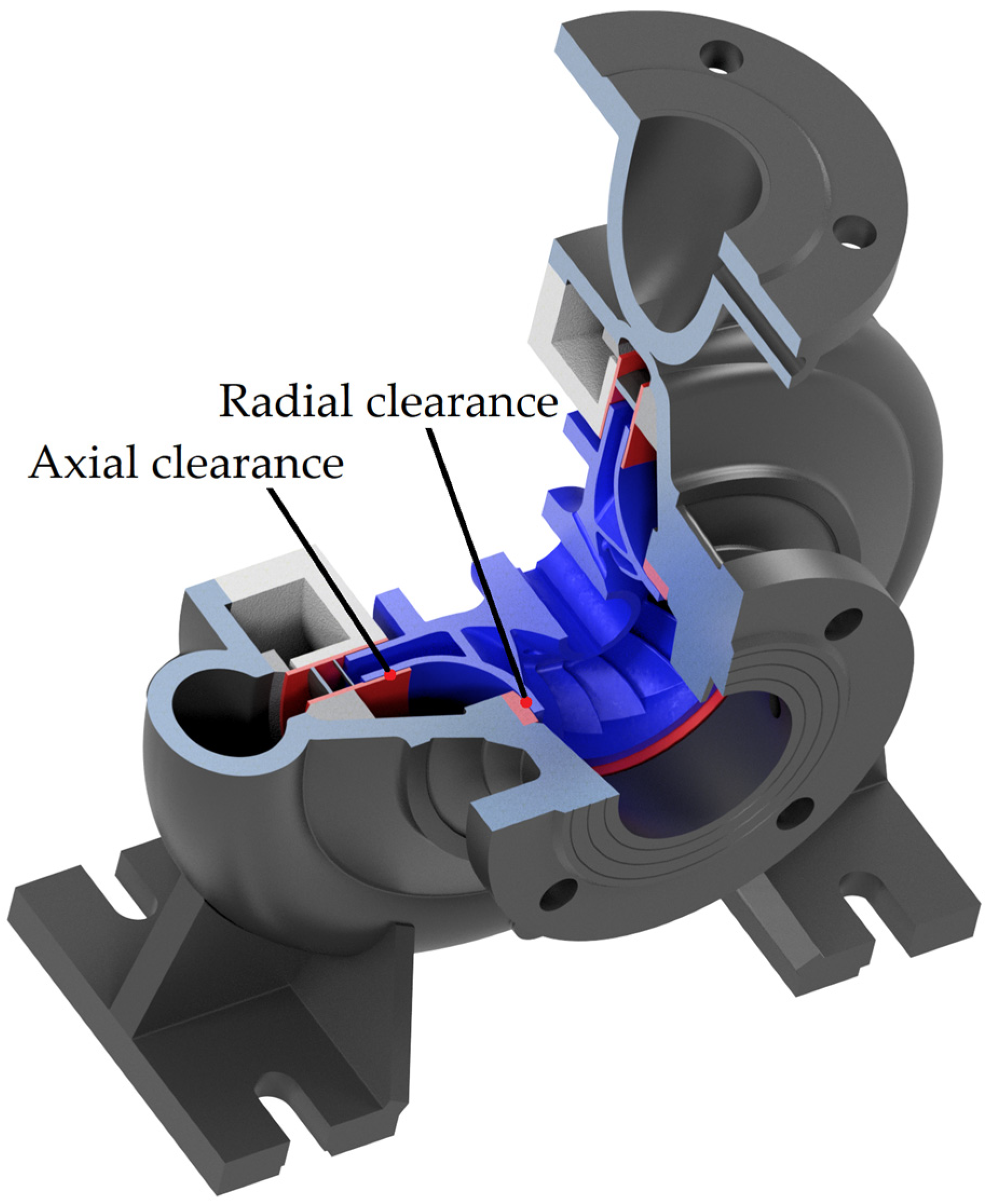

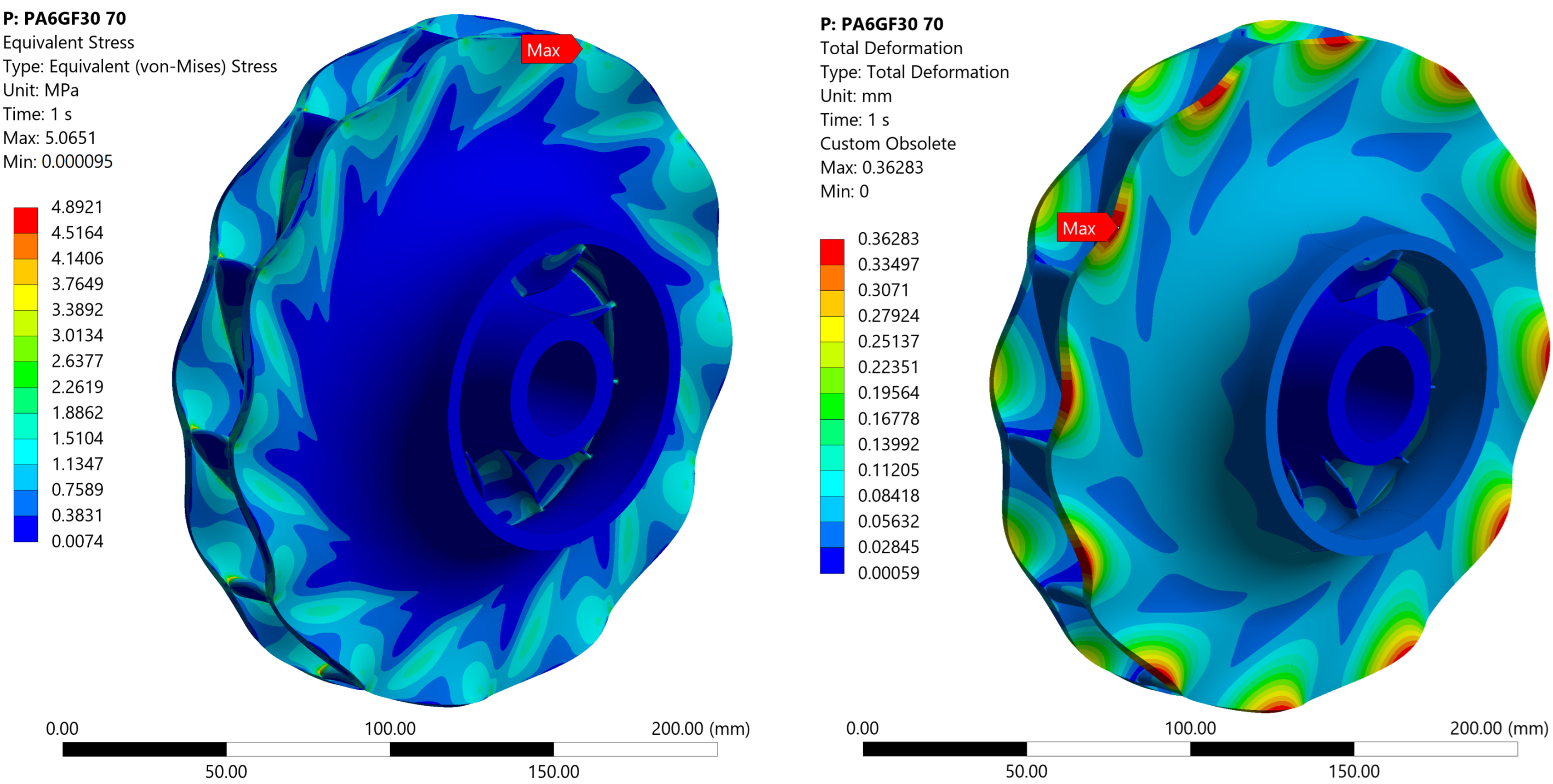

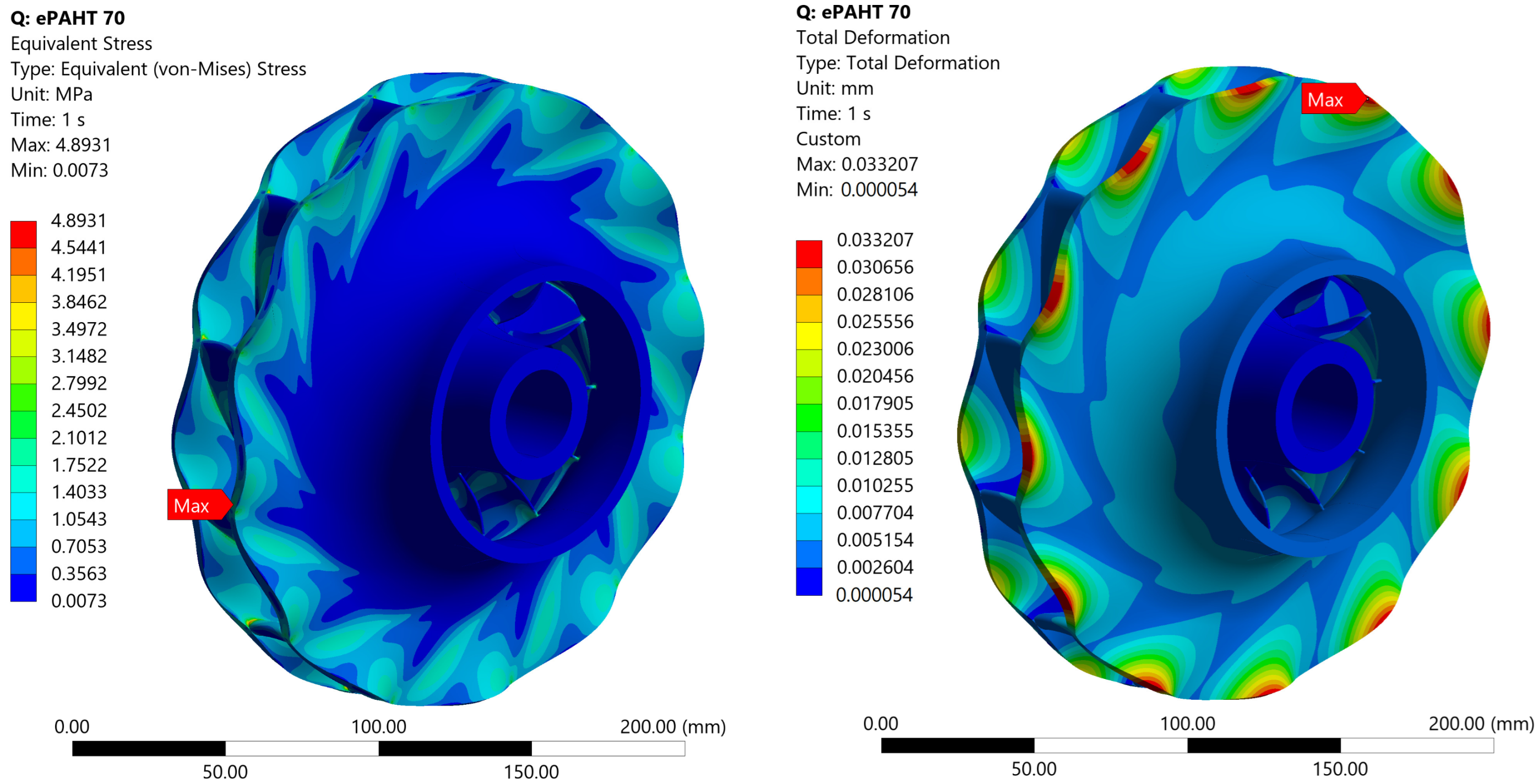

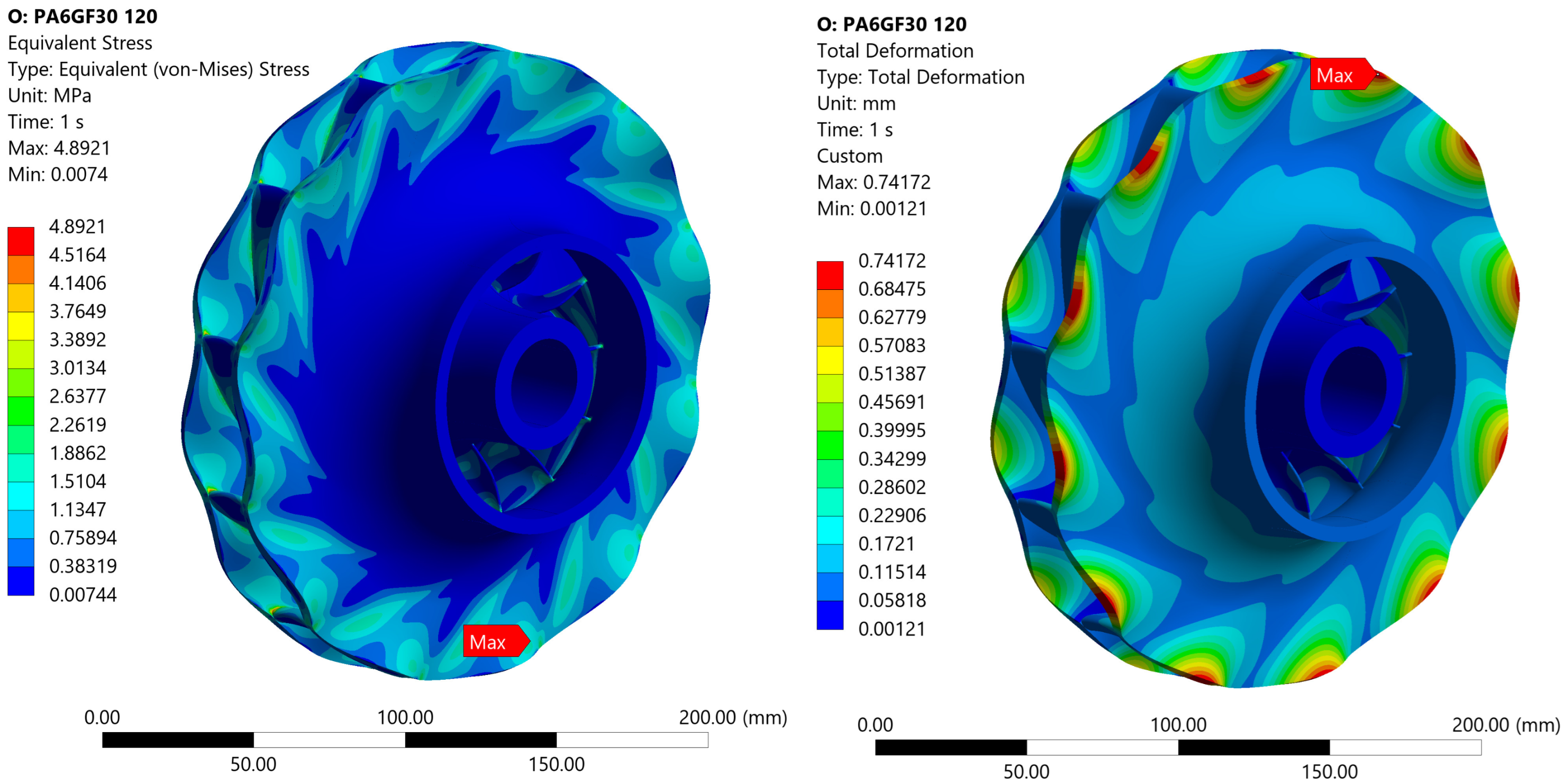

5. Structural Analysis

5.1. Problem Formulation

5.2. Geometry Preparation and Boundary Conditions

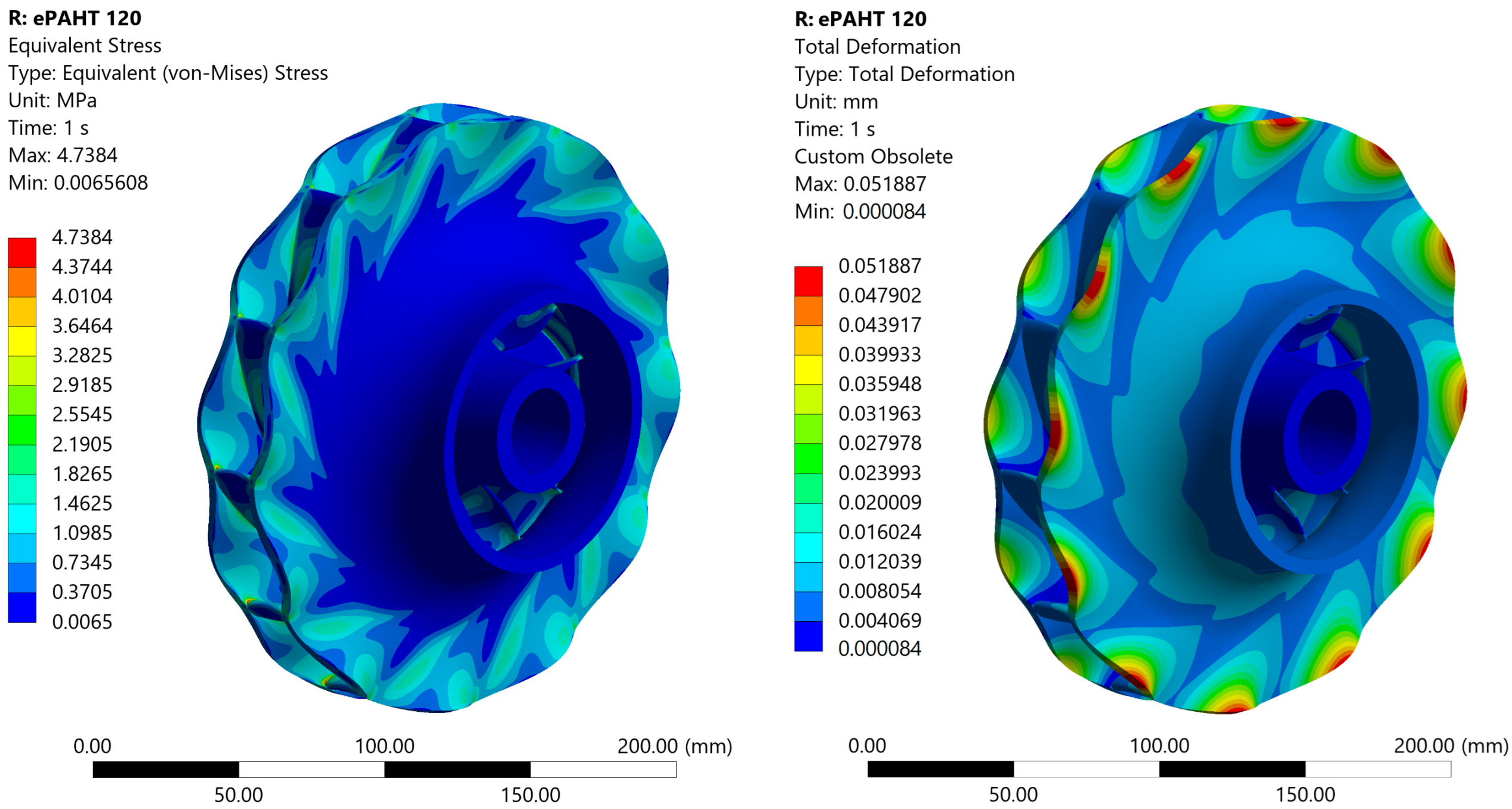

5.3. Structural Strength Simulation Results

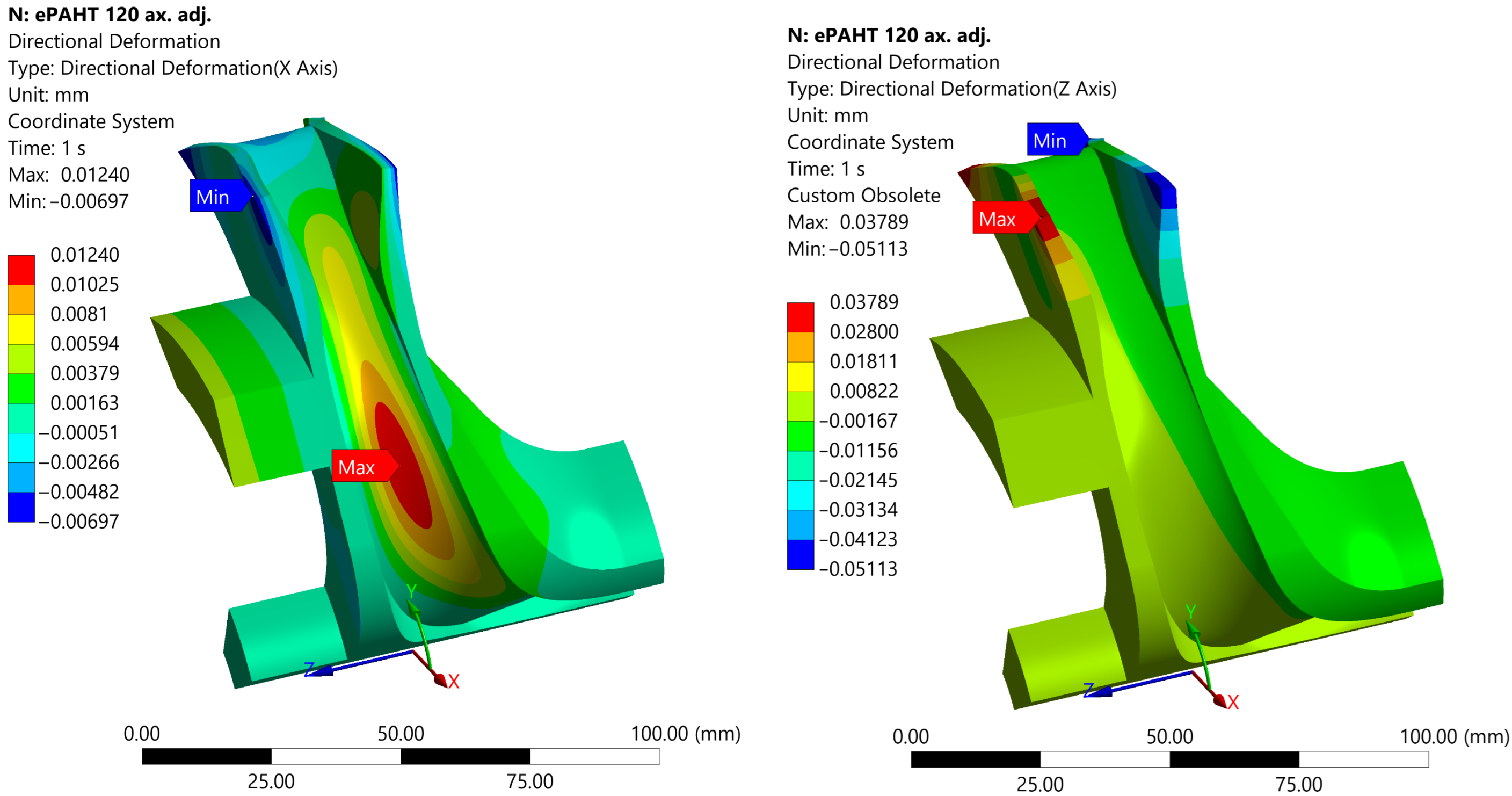

5.4. Axial Sealing Gap Adjustment

6. Conclusions

- Among ASA-X CF10, PA6-GF30, and ePAHT-CF15, ePAHT-CF15 is the most suitable material for 3D-printed PAT impellers operating in district heating systems;

- Material selection is primarily influenced by its stiffness and heat deflection behavior, with a focus on achieving high values of Young’s modulus and heat deflection temperature;

- Annealing ePAHT-CF15 significantly improves its strength properties;

- For tests at 60 °C, the Young’s modulus of annealed ePAHT-CF15 increased seven-fold, its yield strength five-fold, and its ultimate tensile strength is tripled. At 120 °C, it also showed significant improvement of mechanical strength;

- Based on the technical specifications provided, the impeller geometry for the MVB65.250 hydro-turbine pump was prepared, and a flow analysis was conducted to obtain the pressure distribution across the shroud and blade;

- Structural analysis confirmed that ePAHT-CF15 exhibited the lowest deformation, with values of 0.033 mm at 70 °C and 0.052 mm at 120 °C;

- The deformation results allowed for precise definition of operational and technological clearances;

- Future work will focus on long-term hydro-thermal aging and combined fluid–structure simulations to validate the performance of the printed impellers in real PAT operation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| CTE | Coefficient of thermal expansion |

| FDM | Fused deposition modeling |

| FFF | Fused filament fabrication |

| HDT | Heat deflection temperature |

| UTS | Ultimate tensile strength |

| YS | Yield strength |

| YM | Young’s modulus |

| CFD | Computational fluid dynamics |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PA6-GF30 | Polyamide-6 reinforced with 30% glass fiber |

| ASA | Acrylonitrile styrene acrylate |

| ePAHT-CF15 | High-temperature PA-based filament with 15% carbon fiber |

Appendix A

| Temperature [°C] | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 110 | 120 | 130 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing at 200 °C | UTS [MPa] | 74.2 | 64.3 | 61.1 | 52.2 | 46.3 | 44.7 | 39.7 | 37.2 |

| YS [MPa] | 55 | 45.2 | 41.4 | 35.1 | 31.1 | 30 | 28.3 | 26.5 | |

| YM [GPa] | 4.9 | 4.2 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 3.05 | 2.9 | 2.74 | 2.5 | |

| Annealing at 175 °C | UTS [MPa] | 72.3 | 57.8 | 53.2 | 45.7 | 39.2 | 36.7 | 32.5 | 28.9 |

| YS [MPa] | 54.7 | 41.6 | 39.4 | 32.4 | 27.3 | 24.5 | 21.3 | 18.2 | |

| YM [GPa] | 5 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 2.5 | 2.3 | |

| Annealing at 150 °C | UTS [MPa] | 54.2 | 61.8 | 47.4 | 46.2 | 37.2 | 31.2 | 29.6 | 25.8 |

| YS [MPa] | 50.4 | 47 | 36 | 34.9 | 27.8 | 22.7 | 20.9 | 18.4 | |

| YM [GPa] | 4.8 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.3 | |

| No heat treatment | UTS [MPa] | 23.6 | 20.2 | 18.8 | 19 | 25.2 | 30.5 | 30.6 | 29.2 |

| YS [MPa] | 11.8 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 6.5 | 12.8 | 15.9 | 15.6 | 15.1 | |

| YM [GPa] | 0.71 | 0.35 | 0.58 | 0.6 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.47 | |

References

- Meli, E.; Furferi, R.; Rind, A.; Ridolfi, A.; Volpe, Y.; Buonamici, F. A General Framework for Designing 3D Impellers Using Topology Optimization and Additive Manufacturing. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 60259–60269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvalsvig, A.; Yuan, X.; Potgieter, J.; Cao, P. Analysing the Tensile Properties of 3D Printed Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Composite Specimens. In Proceedings of the 2017 24th International Conference on Mechatronics and Machine Vision in Practice (M2VIP), Auckland, New Zealand, 21–23 November 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissenboeck, J.; Amirkhanov, A.; Li, W.; Reh, A.; Amirkhanov, A.; Groeller, E.; Kastner, J.; Heinzl, C. Fiber Scout: An Interactive Tool for Exploring and Analyzing Fiber Reinforced Polymers. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Pacific Visualization Symposium, Yokohama, Japan, 4–7 March 2014; pp. 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajmohan, T.; Vignesh, G.; Palanikumar, K.; Harish, G. Synthesis and Characterization of Nano Filled Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composites. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Advanced Nanomaterials & Emerging Engineering Technologies, Chennai, India, 24–26 July 2013; pp. 218–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Mao, P.; He, W.; Li, J.; Dong, Y.; Wang, X. Influence of process parameters on the tensile properties of CFRTP composites 3D printed structures. Mech. Adv. Mat. Struct. 2024, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.; Fritsch, R.; Kier, J.; Malzer, K. A Green Process for Modifying Wood. Patent WO 2021/113705 A1, 4 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, G.; Lu, J. Comparison of silicate impregnation methods to reinforce Chinese fir wood. Holzforschung 2021, 75, 126–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furuno, T.; Imamura, Y. Combinations of wood and silicate Part 6. Biological resistances of wood-mineral composites using water glass-boron compound system. Wood Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, G.; Li, X. Construction of a network structure in Chinese firwood by Na2SiF6 crosslinked Na2SiO3. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 14190–14199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Xu, M.; Cai, L. Improvement of mechanical, humidity resistance and thermal properties of heat-treated rubber wood by impregnation of SiO2 precursor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Feng, M.; Zhan, H. Preparation of SiO2–wood composites by an ultrasonic-assisted sol–gel technique. Cellulose 2014, 21, 4393–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Lu, J.; Yuan, G.; Wu, Y. Preparation and characterization of sodium silicate impregnated Chinese fir wood with high strength, water resistance, flame retardant and smoke suppression. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Chu, P. Finite element analysis of large plastic impeller. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference On Computer Design and Applications, Qinhuangdao, China, 25–27 June 2010; Volume 4, pp. 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleksy, M.; Budzik, G.; Kozik, B.; Gardzińska, A. Hybrydowe nanokompozyty polimerowe stosowane w technologii Rapid Prototyping. Polimery 2017, 62, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozik, B.; Dębski, M.; Bąk, P.; Gontarz, M.; Zaborniak, M. Effect of heat treatment on the tensile properties of incrementally processed modified polylactide. Polimery 2021, 66, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, J.; Bobovsky, Z.; Safar, M.; Mlotek, J.; Vocetka, M.; Zeman, Z. Experimental analysis of temperature resistance of 3D printed PLA components. MM Sci. J. 2021, 4322–4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suder, J.; Bobovsky, Z.; Zeman, Z.; Mlotek, J.; Vocetka, M. The influence of annealing temperature on tensile strength of plyactic acid. MM Sci. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sztorch, B.; Brzakalski, D.; Pakuła, D.; Frydrych, M.; Špitalský, Z.; Przekop, R. Natural and Synthetic Polymer Fillers for Applications in 3D Printing—FDM Technology Area. Solids 2022, 3, 508–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz, H.; Hasan, M.; Dhanak, V.; Beamson, G.; Stewart, J.; Rangari, V.; Wei, X.; Khabashesku, V.; Jeelani, S. Reinforcement of nylon 6 with functionalized silica nanoparticles for enhanced tensile strength and modulus. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 445702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Meng, J.; Liu, Y. Strain Rate Dependence of Compressive Mechanical Properties of Polyamide and Its Composite Fabricated Using Selective Laser Sintering under Saturated-Water Conditions. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos Pintos, P.; Moreno Sánchez, D.; Delgado, F.J.; Sanz de León, A.; Molina, S.I. Influence of the Carbon Fiber Length Distribution in Polymer Matrix Composites for Large Format Additive Manufacturing. Polymers 2024, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, I.; Melo, C.; Neto, R.; Machado, M.; Alves, J.L.; Mould, S. Study of the Annealing Influence on the Mechanical Performance of PA12 and PA12 Fibre Reinforced FFF Printed Specimens. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2020, 26, 1761–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handwerker, M.; Wellnitz, J.; Marzbani, H.; Tetzlaff, U. Annealing of Chopped and Continuous Fibre Reinforced Polyamide 6 Produced by Fused Filament Fabrication. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 223, 109119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Xin, B.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, B.; Pang, Y. Two-Stage Annealing Method for Short Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Nylon 6 in Fused Filament Fabrication. Polym. Compos. 2025, 46, 618–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wang, J. Influences of Isothermal Annealing Post-Treatment on Mechanical Performances in Fused Deposition Modeling Manufactured Short Carbon Fibrous PETG and PA Composites. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2024, 64, 6247–6264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Jain, P.A.; Sattar, S.; Mulqueen, D.; Pedrazzoli, D.; Kravchenko, S.G.; Kravchenko, O.G. Role of Annealing and Isostatic Compaction on Mechanical Properties of 3D Printed Short Glass Fiber Nylon Composites. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 51, 102599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tumarchenko, L.; Vyshnepolskyi, Y.; Pavlenko, D. Effect of Heat Treatment on the Mechanical Properties of Nylon Parts in Additive Manufacturing. Nauk. Visnyk Natsionalnoho Hirnychoho Universytetu 2025, 2, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Yan, Y.; Mei, H.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, L. Effect of Infill Density, Build Direction and Heat Treatment on the Tensile Mechanical Properties of 3D-Printed Carbon-Fiber Nylon Composites. Compos. Struct. 2023, 304, 116370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazurkiewicz, M.; Kluczyński, J.; Jasik, K.; Sarzyński, B.; Szachogłuchowicz, I.; Łuszczek, J.; Torzewski, J.; Śnieżek, L.; Grzelak, K.; Małek, M. Bending Strength of Polyamide-Based Composites Obtained in FFF and SLS Processes. Materials 2022, 15, 5079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belei, C.; Joeressen, J.; Amancio-Filho, S.T. Fused-Filament Fabrication of Short Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide: Parameter Optimization for Improved Performance under Uniaxial Tensile Loading. Polymers 2022, 14, 1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, G.; Li, Z.; Cheng, Y.; Xu, D.; Zhu, D.; Jiang, S.; Guo, J.; Chen, X.; Xu, G.; Zhu, Y. Properties of Oriented Carbon Fiber/Polyamide 12 Composite Parts Fabricated by Fused Deposition Modeling. Mater. Des. 2018, 139, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, G.S.; Aravind Raj, S.; Adithya, R.N. Effect of Post-Heat Treatment on the Mechanical and Surface Properties of Nylon 12 Produced via Material Extrusion and Selective Laser Sintering Processes. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 10149–10174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirak, N.; Shirinbayan, M.; Deligant, M.; Tcharkhtchi, A. Toward Polymeric and Polymer Composites Impeller Fabrication. Polymers 2022, 14, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papageorgiou, V.; Mansour, G.; Chouridis, I. Improving Centrifugal Pump Performance and Efficiency Using Composite Materials Through Additive Manufacturing. Machines 2025, 13, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, G.; Papageorgiou, V.; Tzetzis, D. Carbon Fiber Polymer Reinforced 3D Printed Composites for Centrifugal Pump Impeller Manufacturing. Technologies 2024, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.; Praveenkumar, V.; Rusho, M.A.; Yishak, S. Optimizing Additive Manufacturing Parameters for Graphene-Reinforced PETG Impeller Production: A Fuzzy AHP–TOPSIS Approach. Res. Eng. 2024, 24, 103018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN ISO 527-2:2012; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Moulding and Extrusion Plastics. BSI: London, UK, 2012.

- Elnabawy, E.; Sun, D.; Shearer, N.; Toptas, A.; Kılıç, A.; Shyha, I. The role of annealing in enhancing crystallinity, mechanical properties, piezoelectricity, and air filtration performance of polylactic acid nanofibers. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2025, 343, 131000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, G.; Wu, X.; Zhai, Z. The effect of high temperature annealing process on crystallization process of polypropylene, mechanical properties, and surface quality of plastic parts. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2015, 132, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5725-2:2019; Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Measurement Methods and Results—Part 2: Basic Method for the Determination of Repeatability and Reproducibility of a Standard Measurement Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Szulc, P.; Lorenz, W.W.; Bieganowski, M.; Janczak, M. Design and modeling of a hydraulic energy recuperator based on a centrifugal pump. Wrocław Univ. Sci. Technol. Rep. 2019, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.V.; Swarnkar, A.; Motwani, K.H.; Patel, R.N. Effects of impeller diameter and rotational speed on performance of pump running in turbine mode. Energy Energy Convers. Manag. 2015, 89, 808–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, G.; Li, Z.; Wei, X. Influence of the Clearance Flow on the Load Rejection Process in a Pump-Turbine. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 11359-2:2021; Plastics—Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)—Part 2: Determination of Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion and Glass Transition Temperature. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

| Properties | ASA-X CF10 | PA6-GF30 | ePAHT-CF15 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile strength, MPa | 79 | 80 | 173 |

| Tensile modulus, MPa | 7580 | 5500 | − |

| Flexural modulus, MPa | − | 4500 | 5612 |

| Density, g/cm3 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| HDT 0.45 MPa, °C | 90 °C | 180 °C | 190 °C |

| Printing temperature | 235–260 °C | 250–280 °C | 240–300 °C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Błoński, D.; Romanik, G.; Augustyn, M.; Regucki, P. Tensile and Structural Performance of Annealed 3D-Printed Polymer Composite Impellers for Pump-as-Turbine Applications in District Heating Networks. Materials 2026, 19, 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010127

Błoński D, Romanik G, Augustyn M, Regucki P. Tensile and Structural Performance of Annealed 3D-Printed Polymer Composite Impellers for Pump-as-Turbine Applications in District Heating Networks. Materials. 2026; 19(1):127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010127

Chicago/Turabian StyleBłoński, Dominik, Grzegorz Romanik, Michał Augustyn, and Paweł Regucki. 2026. "Tensile and Structural Performance of Annealed 3D-Printed Polymer Composite Impellers for Pump-as-Turbine Applications in District Heating Networks" Materials 19, no. 1: 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010127

APA StyleBłoński, D., Romanik, G., Augustyn, M., & Regucki, P. (2026). Tensile and Structural Performance of Annealed 3D-Printed Polymer Composite Impellers for Pump-as-Turbine Applications in District Heating Networks. Materials, 19(1), 127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010127