Research on Microstructure Evolution and Rapid Hardening Mechanism of Ultra-Low Carbon Automotive Outer Panel Steel Under Minor Deformation

Abstract

1. Introduction

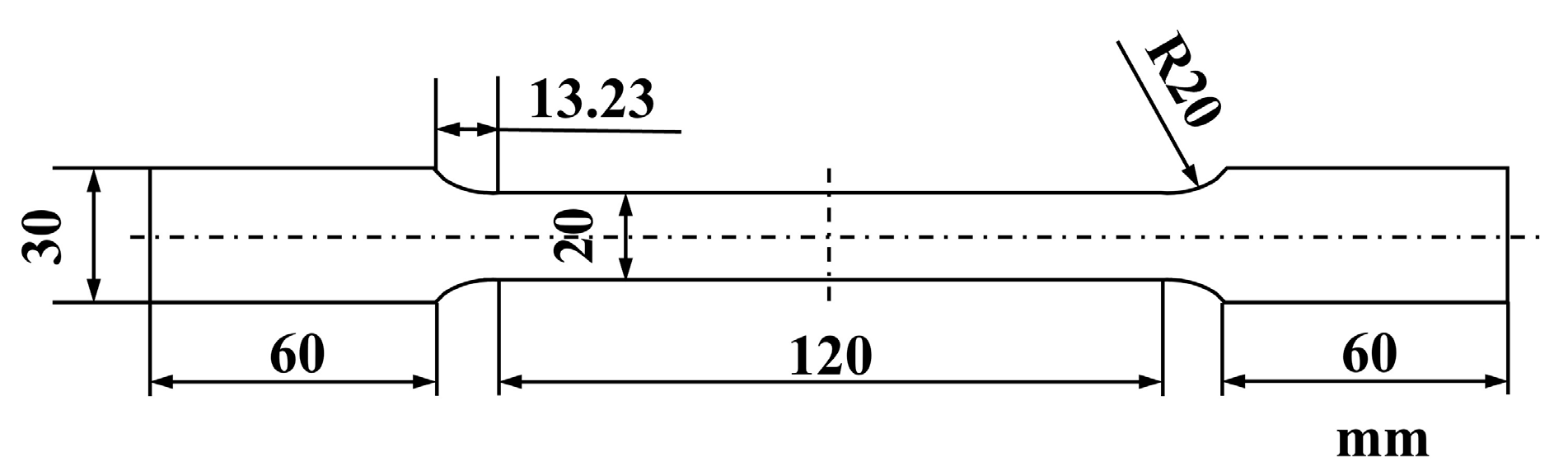

2. Experimental Methods

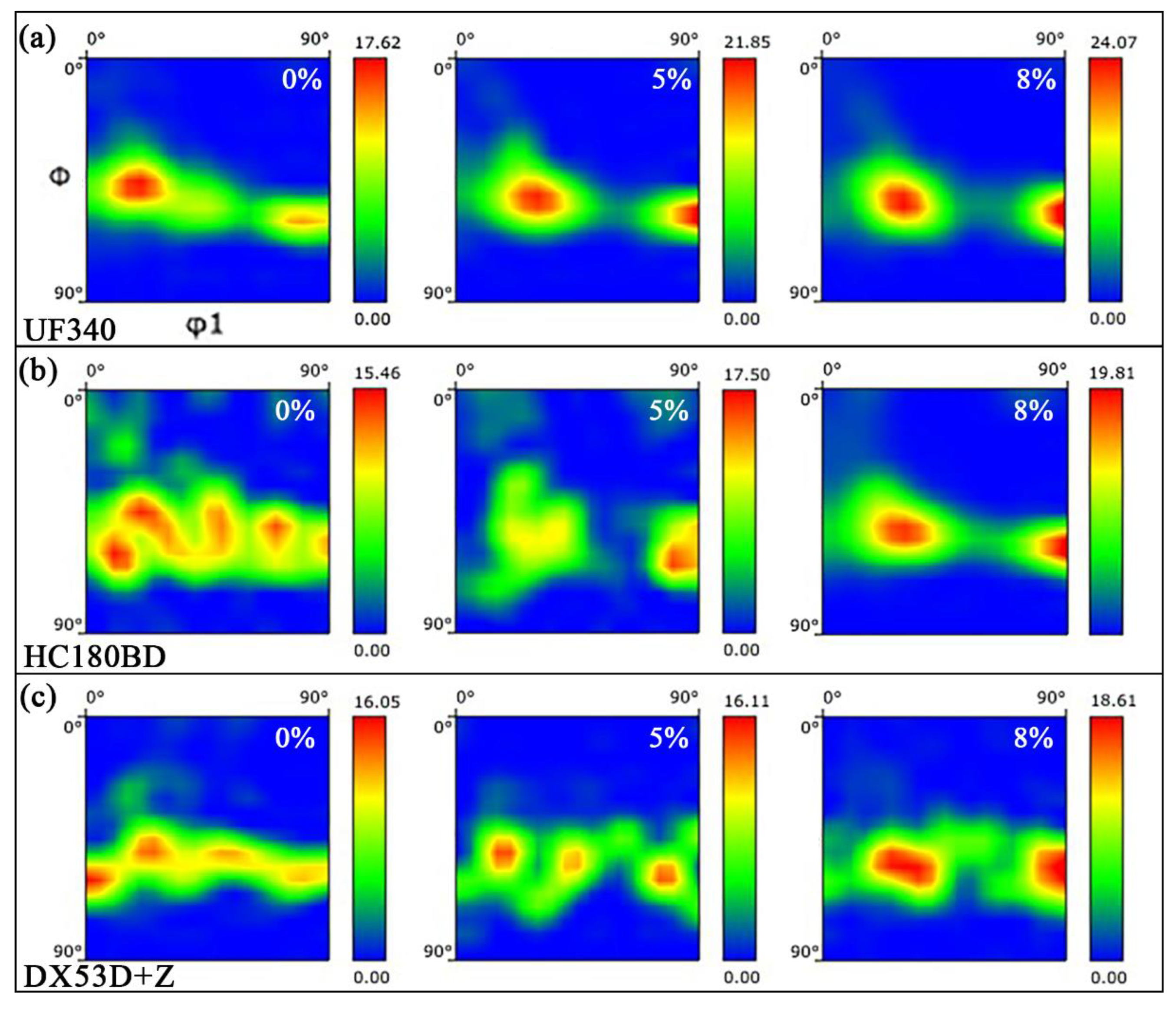

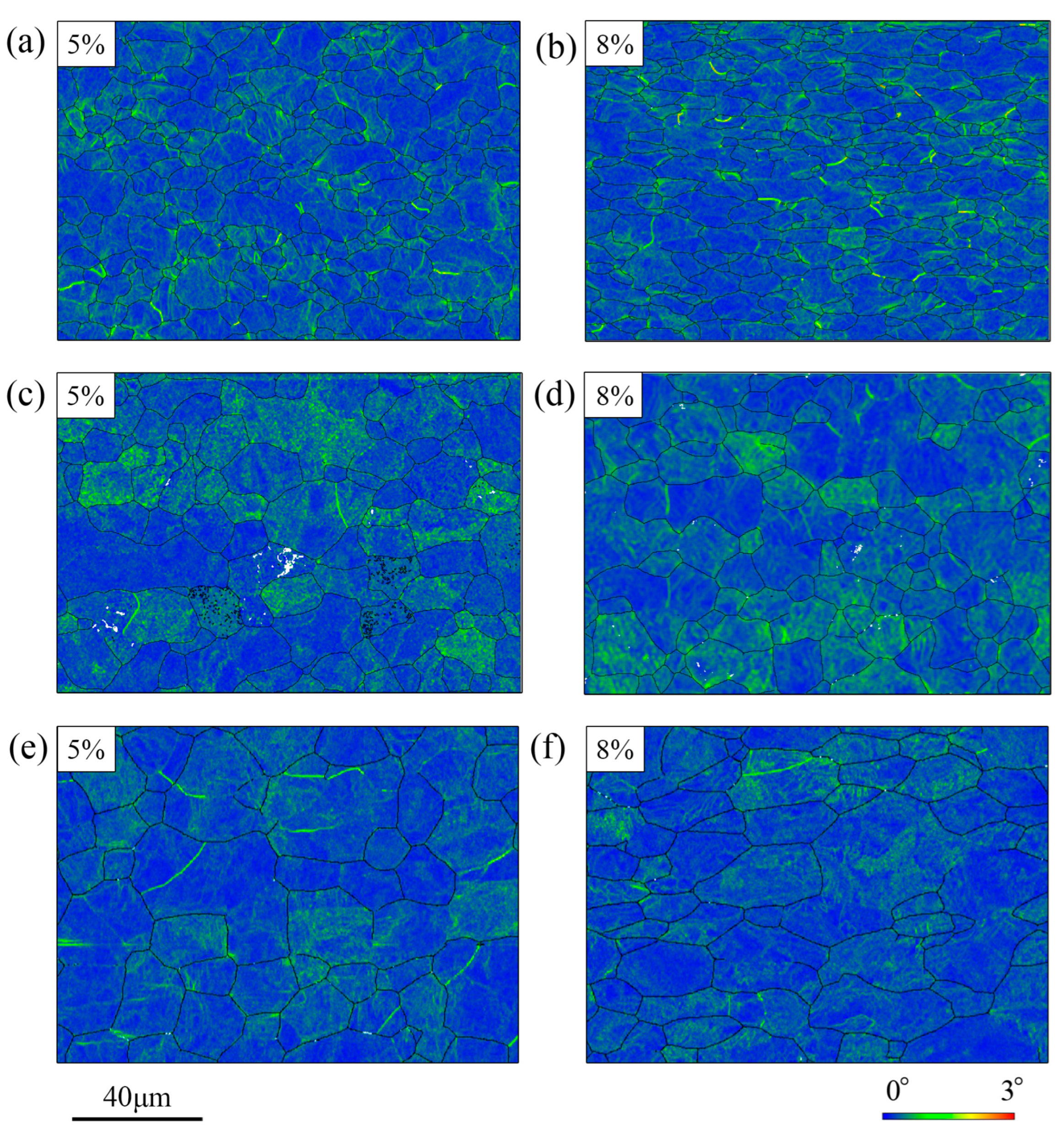

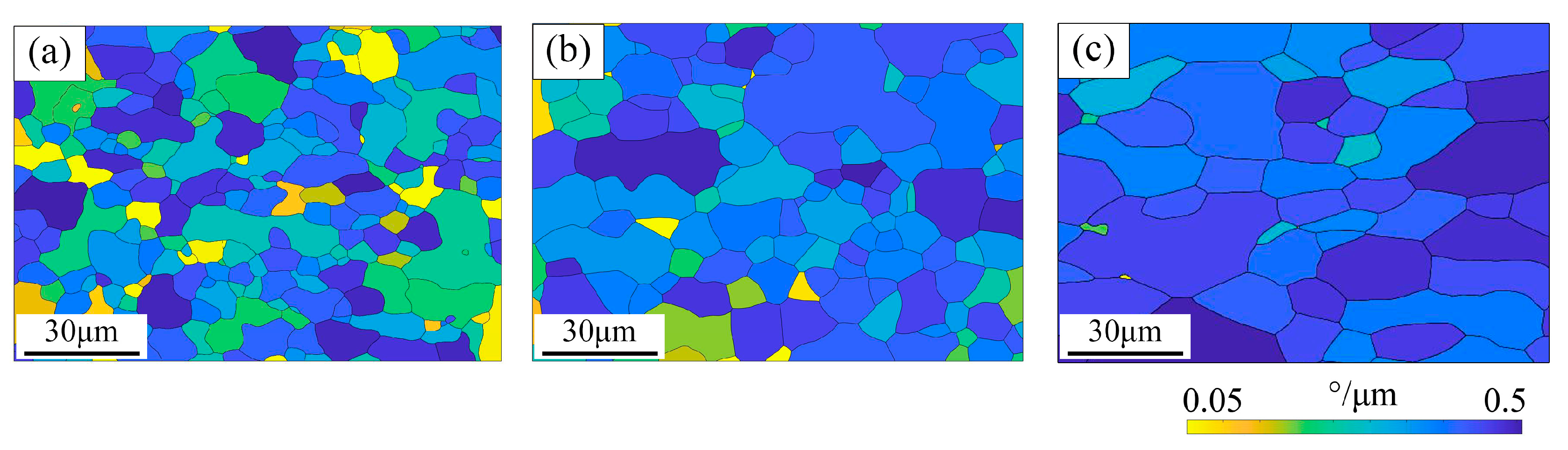

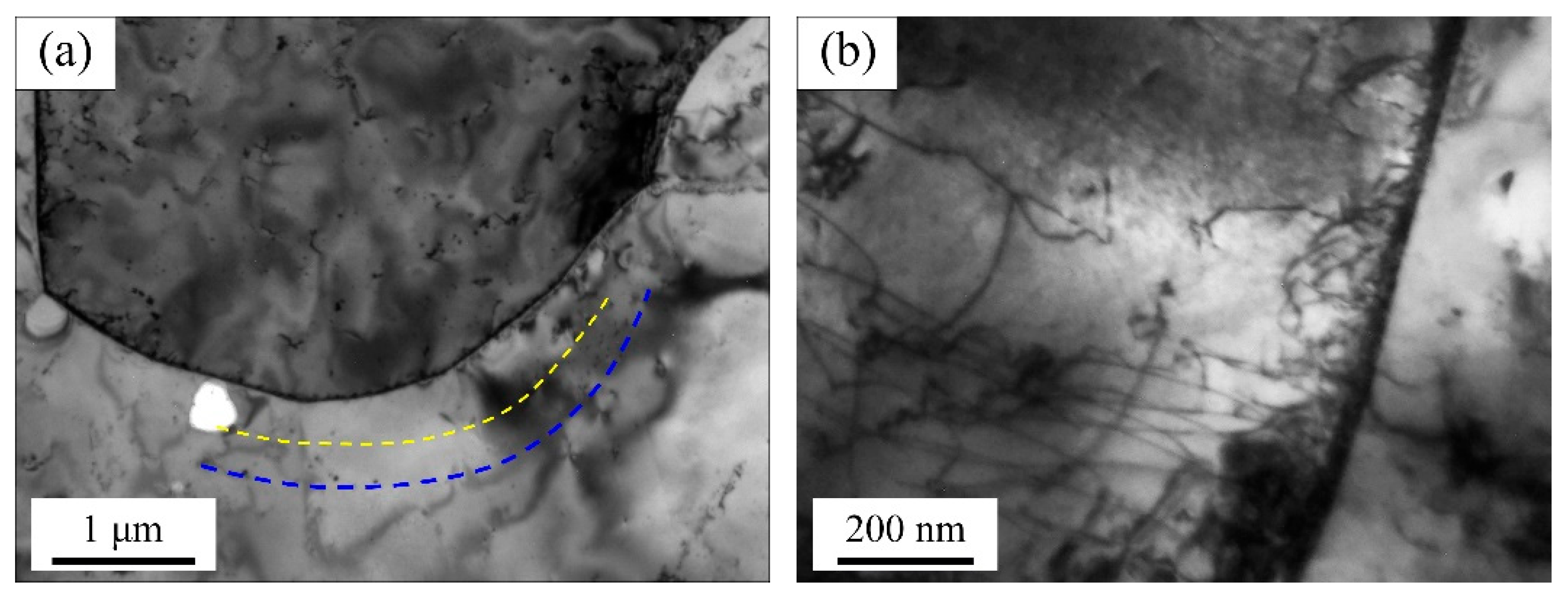

3. Results and Discussion

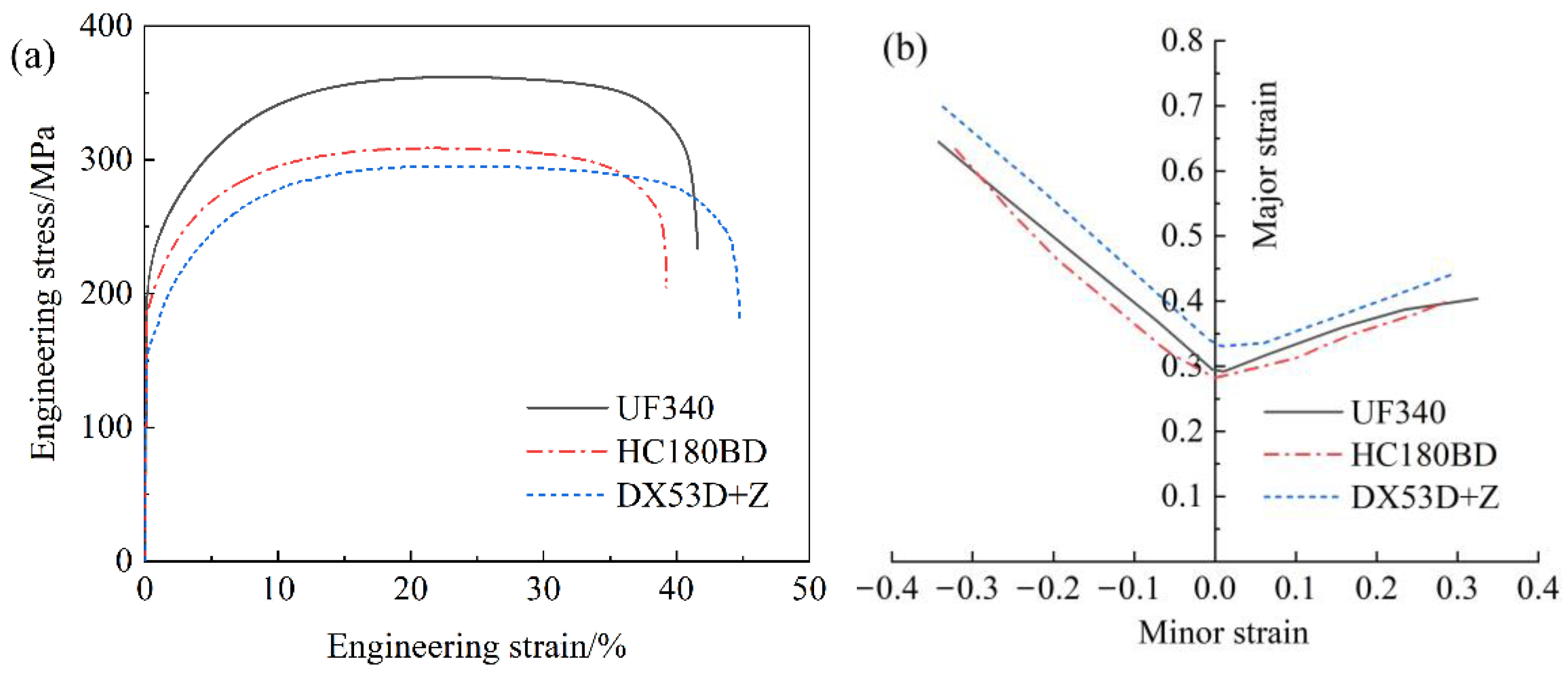

3.1. Mechanical Properties

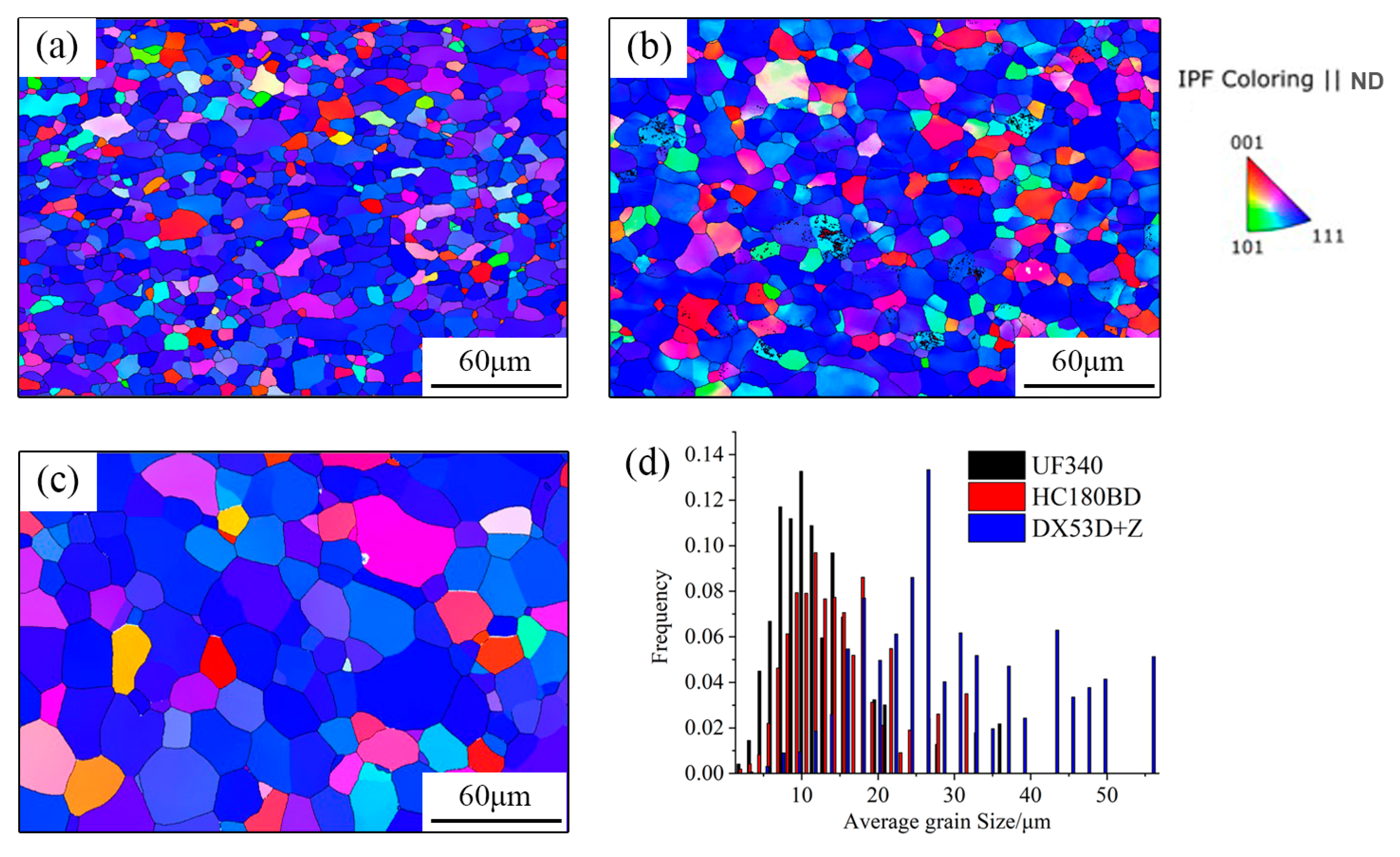

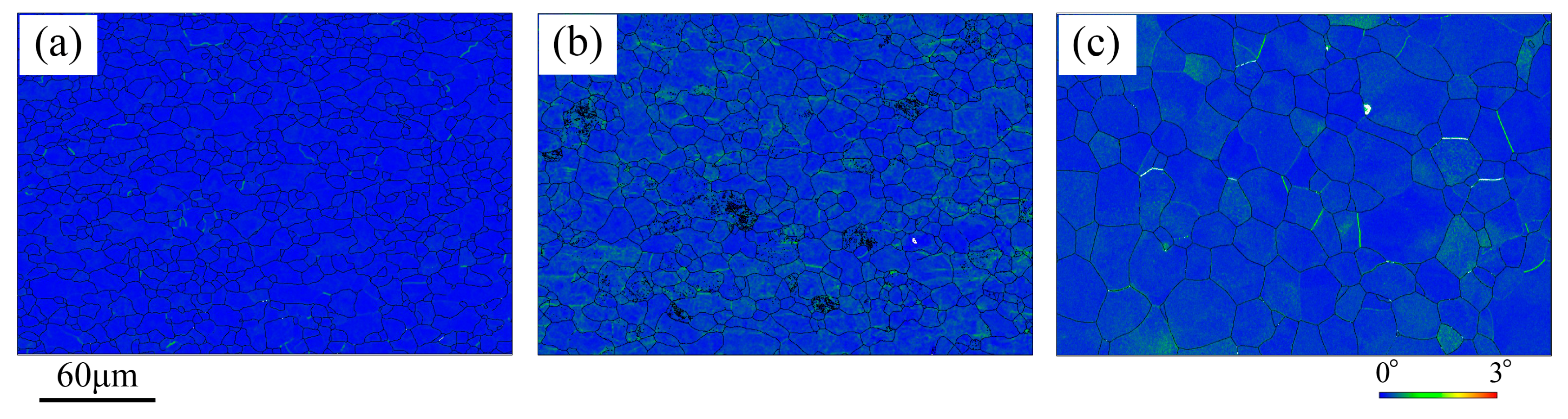

3.2. Microstructure

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, L.; Jia, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Novel Multiphase DC/DC Boost Converter for Interaction of Solar Energy and Hydrogen Fuel Cell in Hybrid Electric Vehicles. Renew. Renew. Energy 2024, 229, 120779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pinkerton, A.; Li, L.; Liu, Z.; Mistry, A. Gap-Free Fibre Laser Welding of Zn-Coated Steel on Al Alloy for Light-Weight Automotive Applications. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, N.; Al-Ali, A.; Al-Ali, A.; Bayhan, S.; Malluhi, Q. LPPDA: A Light-Weight Privacy-Preserving Data Aggregation Protocol for Smart Grids. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 95358–95367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doruk, E.; Demir, S. New Generation Steels for Light Weight Vehicle Safety Related Applications. Mater. Test. 2024, 66, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fang, G.; Zhou, J.; Zhou, Z.; Niu, L. Dent resistance of sheet metal for automobile panel. Forg. Stamp. Technol. 2024, 49, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Wan, X.; Zhou, J. Research on Dent Resistance Properties of Steel Sheets for Automotive Outer Panel. Hot Work. Technol. 2022, 51, 40–43+47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Wang, K.; Yang, Q.; Lin, Y.; Zhu, L.; Wu, X.; Han, B.; Wang, B.; Zhang, D.; Feng, J. Research on the Strengthening Mechanism of Nb-Ti Microalloyed Ultra Low Carbon IF Steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 5785–5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.M.; Chen, R.; Jia, H.B.; Li, Y.; Jiang, Z.Y. Effect of Solid-Solution Second-Phase Particles on the Austenite Grain Growth Behavior in Nb-Ti High-Strength If Steel. Strength Mater. 2020, 52, 539–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Y.; Fujita, T.; Nagataki, Y.; Urabe, T.; Hosoya, Y. Effect of NbC Distribution on Mechanical Properties in IF High Strength Steel with Fine Grain Structure. Mater. Sci. Forum 2003, 426–432, 1481–1486. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Qiao, L. The Study on the Low Yield Strength for Super Fine Grain and High Strength Bearing Nb IF Steel. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 335–336, 615–618. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Guan, J.; Wei, D.; Jin, L.; Wang, M.; Fu, G. Effects of Cooling Water between Rolling Mills on Surface Microstructure Uniformity of UF340. Automot. Technol. Mater. 2024, 6, 31–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jiao, H.; Wang, Q.; Gong, J.; Guan, J.; Wang, M.; Zhang, B. Recrystallization behavior of Nb-containing high strength IF steel during finishing rolling. Phys. Exam. Test 2025, 43, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Fang, G.; Lu, H.; Jin, L.; Guan, J.; Guo, A. Research on the Properties of the New Steel for Automotive Covering Parts. Automot. Technol. Mater. 2024, 6, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guan, J.; Ma, J.; Gong, J.; Wu, N.; Wei, D.; Wang, W.; Chen, F. Microstructure and Texture Development during Annealing in UF340. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2635, 012020. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 228.1-2021; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. State Administration for Market Regulation. Standardization Administration of the People’s Republic of China; China Standards Press: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Ramazani, A.; Serafeim, A.; Prahl, U. Towards a Micromechanical Based Description for Strength Increase in Dual Phase Steels during Bake-Hardening Process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 702, 386–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, D.; Luo, S.; Li, L. Influence of Microstructure and Pre-Straining on the Bake Hardening Response for Ferrite-Martensite Dual-Phase Steels of Different Grades. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 708, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Gao, J.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhao, H.; Wu, H.; Mao, X. A novel dual-heterogeneous-structure ultralight steel with high strength and large ductility. Acta Mater. 2023, 252, 118925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonasso, N.; Wagner, F.; Berbenni, S.; Field, D. A study of the heterogeneity of plastic deformation in IF steel by EBSD. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 548, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Guo, Z.; Chen, G.; Chen, S.; Chen, K.; Zhu, C. Probing the micro-mechanism of precipitate-strengthened alloys with precipitate free zone: An experimental and theoretical study. Int. J. Plast. 2024, 181, 104085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, S.; He, K.; Zheng, X.; Jia, G. The effect of precipitate-free zone on mechanical properties in Al-Zn-Mg-Cu aluminum alloy: Strain-induced back stress strengthening. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 969, 172426. [Google Scholar]

| C | N | P | Si | Nb | Mn | Ti | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UF340 | 0.0030 | 0.0014 | 0.03 | 0.100 | 0.045 | 0.15 | - |

| HC180BD | 0.0026 | 0.0012 | 0.02 | 0.004 | 0.007 | 0.13 | - |

| DX53D+Z | 0.0015 | 0.0012 | 0.01 | 0.004 | - | 0.15 | 0.05 |

| Yield Strength/MPa | Tensile Strength/MPa | Elongation/% | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0° | UF340 | 215 | 357 | 40 |

| HC180BD | 191 | 314 | 40 | |

| DX53D+Z | 165 | 292 | 45 | |

| 45° | UF340 | 217 | 353 | 41 |

| HC180BD | 197 | 317 | 40 | |

| DX53D+Z | 170 | 296 | 47 | |

| 90° | UF340 | 218 | 352 | 41 |

| HC180BD | 194 | 308 | 39 | |

| DX53D+Z | 168 | 291 | 45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guan, J.; Li, Y.; Zhu, G.; Kang, Y.; Wang, F.; Xu, J.; Xun, M. Research on Microstructure Evolution and Rapid Hardening Mechanism of Ultra-Low Carbon Automotive Outer Panel Steel Under Minor Deformation. Materials 2026, 19, 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010128

Guan J, Li Y, Zhu G, Kang Y, Wang F, Xu J, Xun M. Research on Microstructure Evolution and Rapid Hardening Mechanism of Ultra-Low Carbon Automotive Outer Panel Steel Under Minor Deformation. Materials. 2026; 19(1):128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010128

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuan, Jiandong, Yi Li, Guoming Zhu, Yonglin Kang, Feng Wang, Jun Xu, and Meng Xun. 2026. "Research on Microstructure Evolution and Rapid Hardening Mechanism of Ultra-Low Carbon Automotive Outer Panel Steel Under Minor Deformation" Materials 19, no. 1: 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010128

APA StyleGuan, J., Li, Y., Zhu, G., Kang, Y., Wang, F., Xu, J., & Xun, M. (2026). Research on Microstructure Evolution and Rapid Hardening Mechanism of Ultra-Low Carbon Automotive Outer Panel Steel Under Minor Deformation. Materials, 19(1), 128. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010128