The Effect of Different Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment Time on the Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy in Artificial Seawater

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Effects of Different SMAT Time on the Surface Morphology, Roughness and Crystal Structure of TC4 Alloy

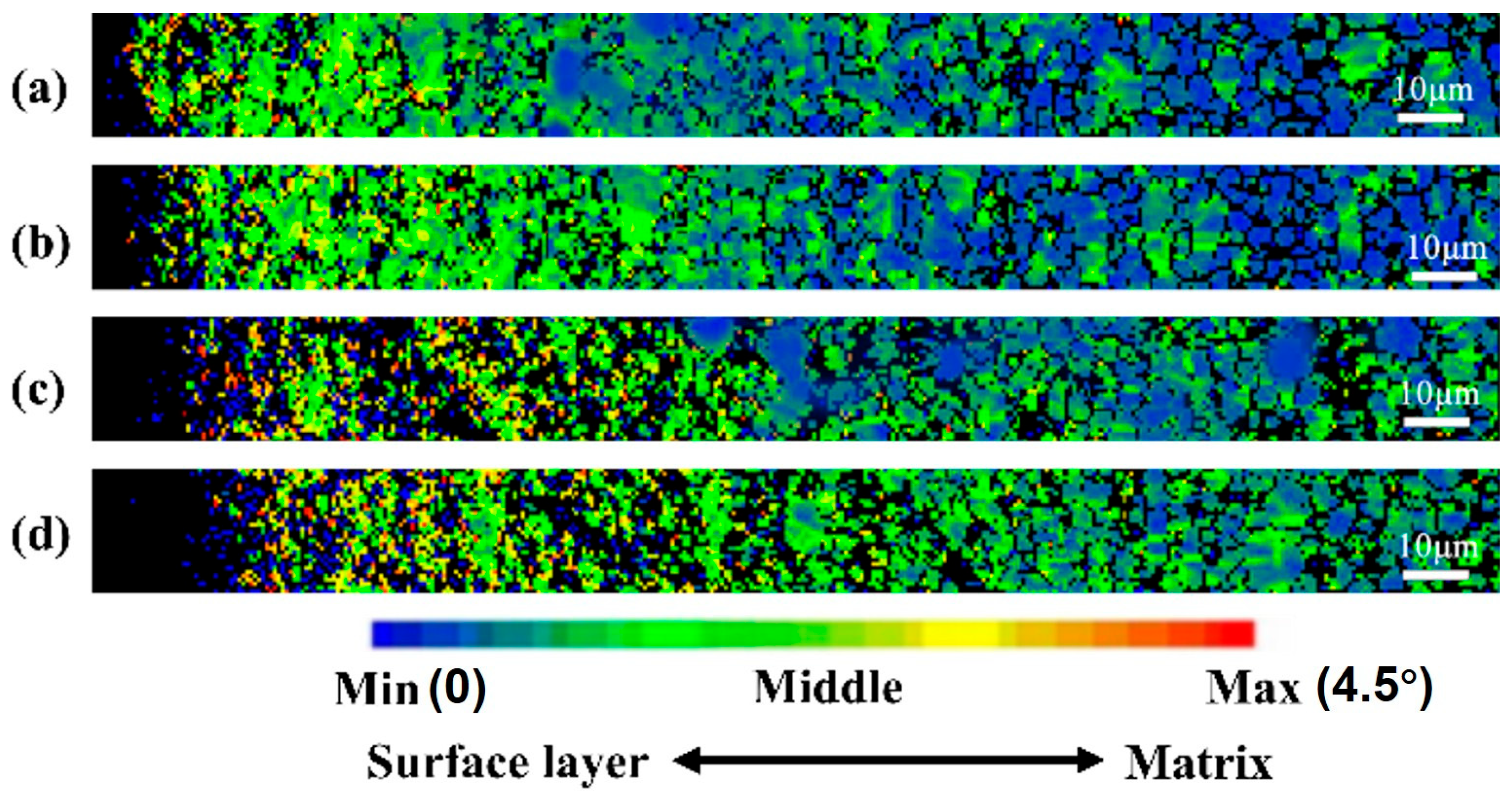

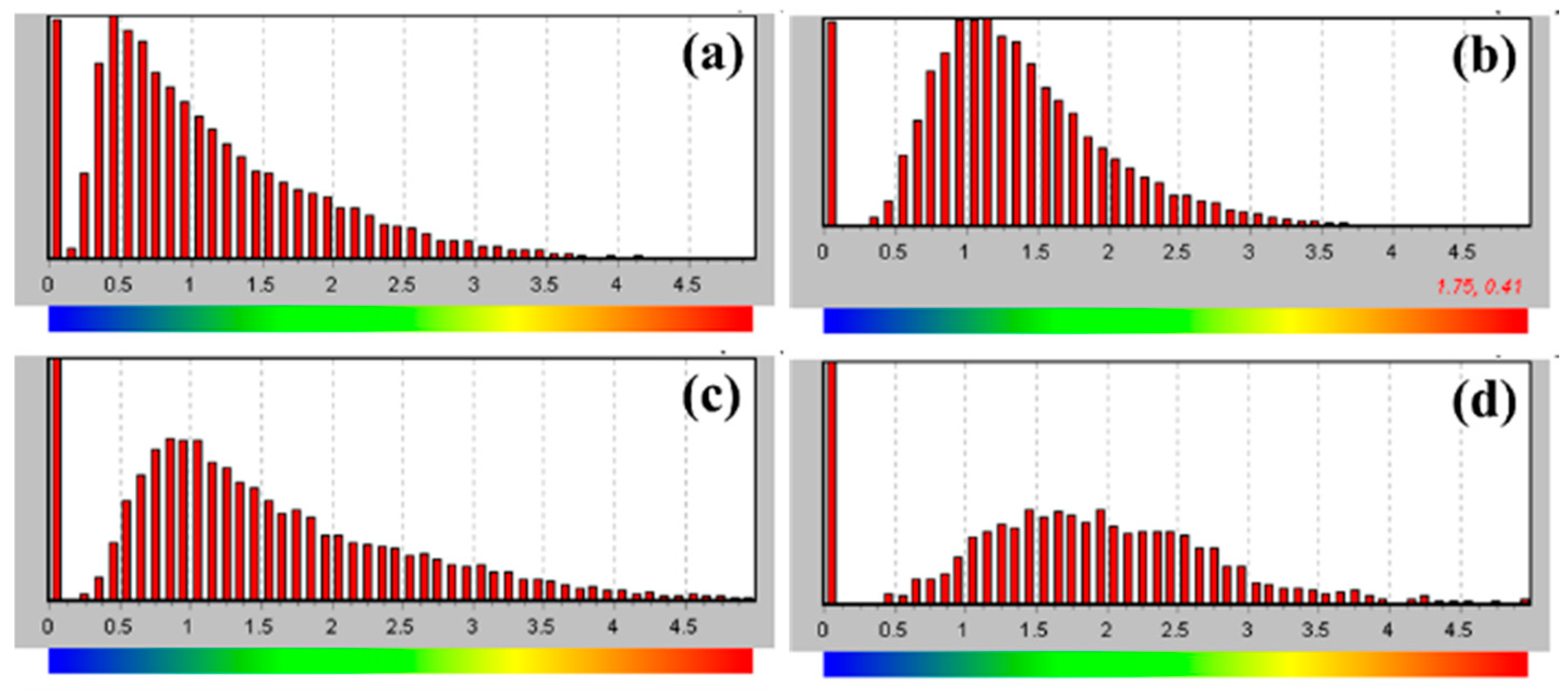

3.2. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of SMAT-Treated TC4

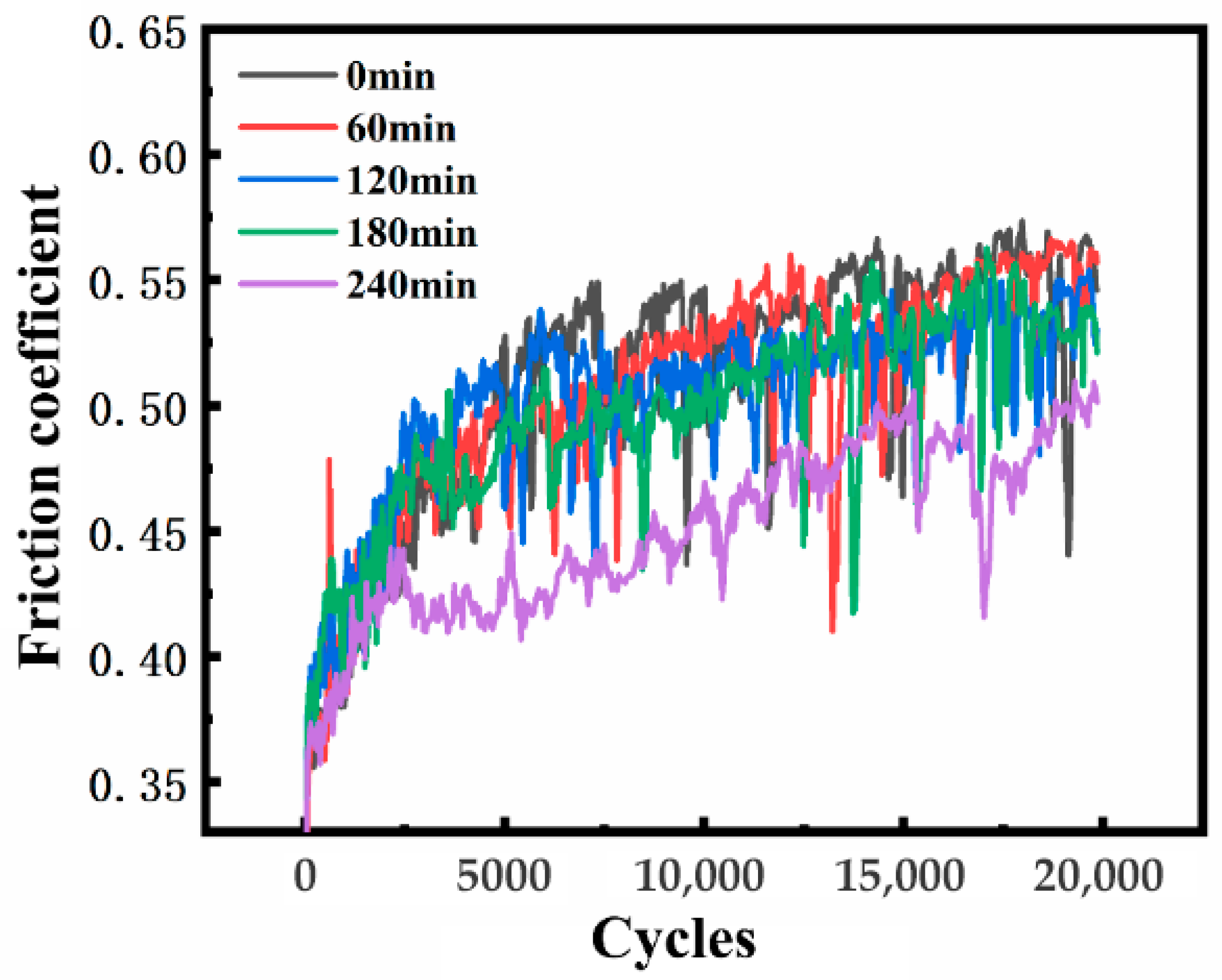

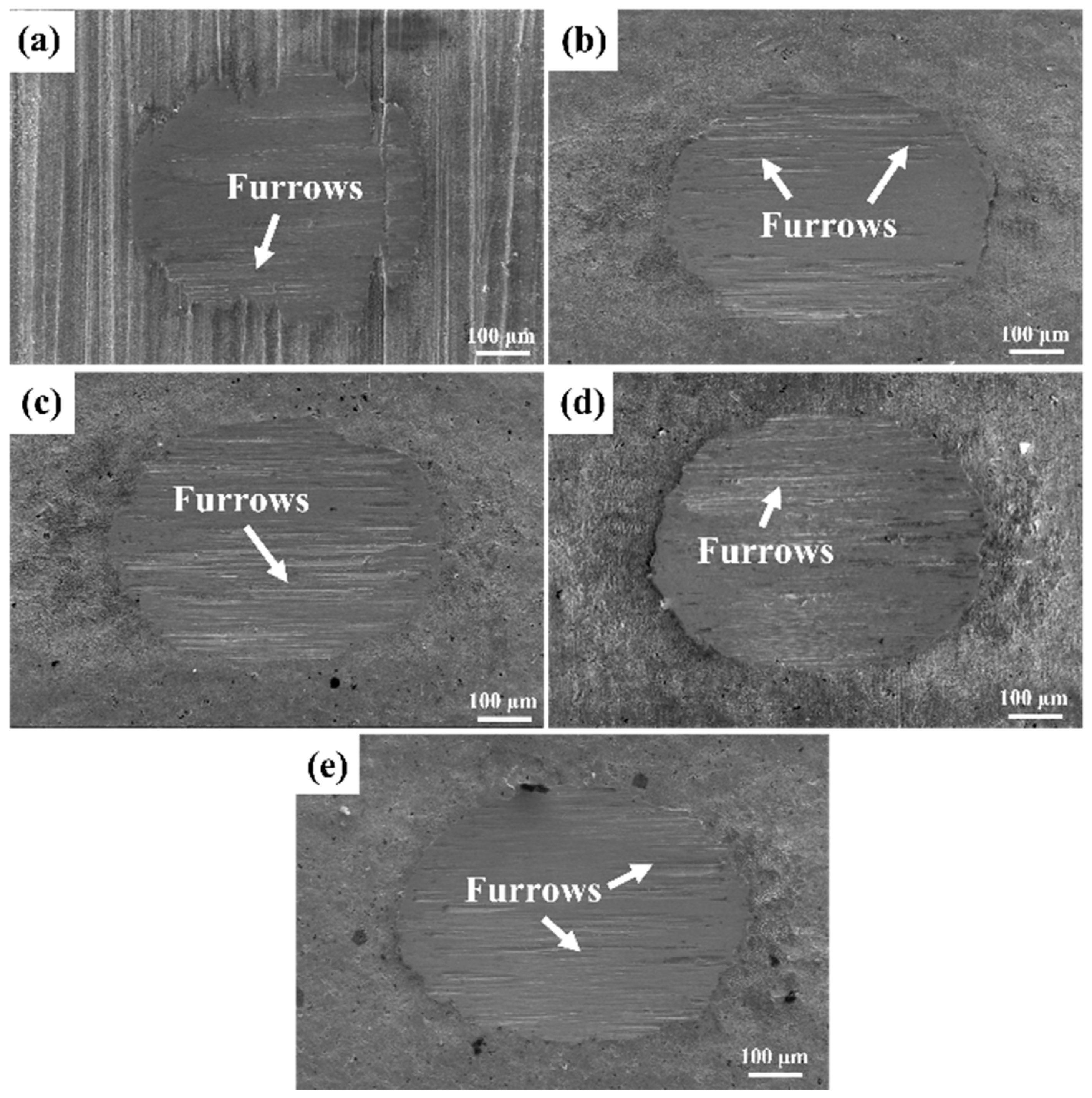

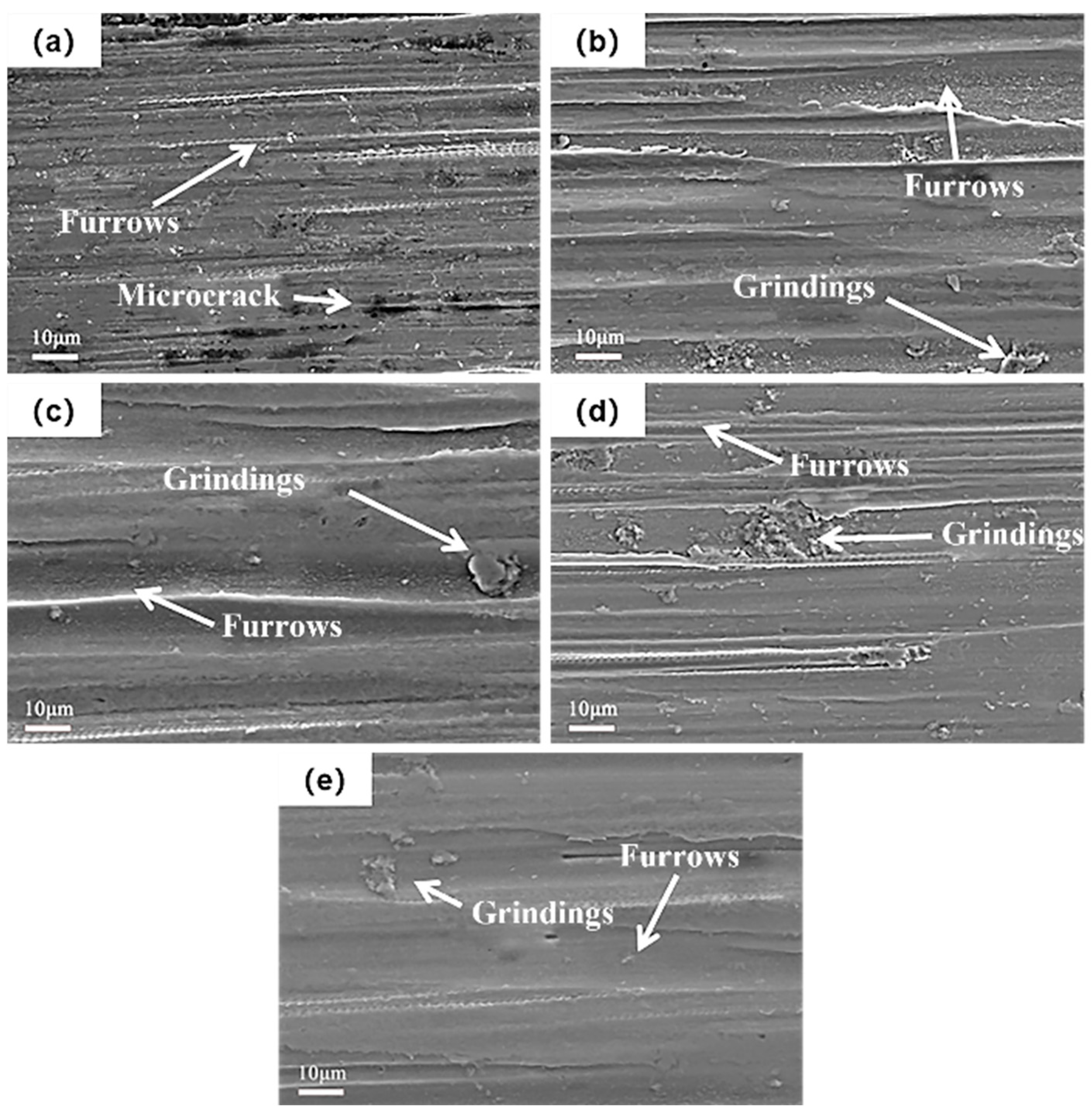

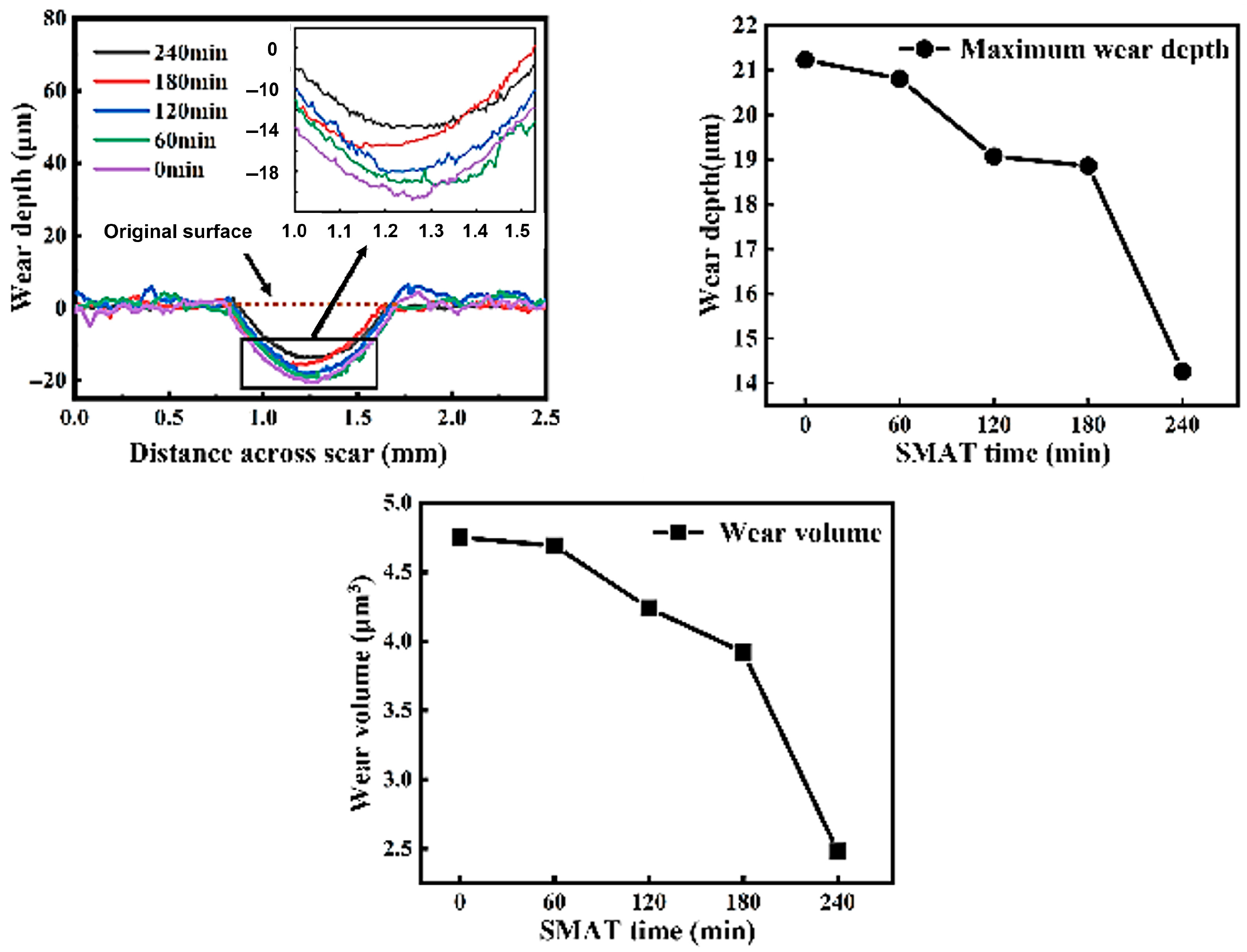

3.3. Effect of Different SMAT Time on Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy

4. Conclusions

- SMAT changes the surface morphology and roughness of TC4 alloy. With the increase in SMAT time, the plow grooves on the original surface disappear and are replaced by shallow pits, and the surface roughness (Ra) increases from 366 nm to 1133 nm.

- SMAT leads to severe plastic deformation of TC4 alloy and significantly refines the grain size. With the increase in SMAT time, the strain significantly increases and the deformation depth increases to 200 μm. The surface grains are obviously refined to nanometer size.

- SMAT significantly improves the fretting wear resistance of TC4 alloy. After 240 min of treatment, the wear depth decreased from 21.23 μm to 14.27 μm (a 32.8% reduction), while the wear volume and wear rate were reduced from 4.75 × 106 μm3 and 2.375 × 103 μm3/s to 2.48 × 106 μm3 and 1.24 × 103 μm3/s, respectively (representing a ~48% improvement.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Samuel Ratna Kumar, P.S.; Mashinini, P.M. Chapter nine—Titanium alloys for aerospace structures and engines. In Aerospace Materials; Sultan, M.T.H., Uthayakumar, M., Korniejenko, K., Mashinini, P.M., Najeeb, M.I., Krishnamoorthy, R.R., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2025; pp. 227–253. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.-W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, L.-C. Towards load-bearing biomedical titanium-based alloys: From essential requirements to future developments. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2024, 144, 101277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fan, J.; Huang, H.; Xue, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Jiang, P.; Wang, C.; Kou, H.; Li, J. Creep anisotropy characteristics and microstructural crystallography of marine engineering titanium alloy Ti6321 plate at room temperature. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 854, 143728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; He, G.; Meng, Q.; Li, Y.; Tian, X. Corrosion mechanism investigation of TiN/Ti coating and TC4 alloy for aircraft compressor application. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2020, 33, 1824–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, B.; Qu, H.; Chen, F. A novel triple-layer hot stamping process of titanium alloy TC4 sheet for enhancing formability and its application in a plug socket part. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2023, 6, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wang, L. State of the art and current trends on the metal corrosion and protection strategies in deep sea. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 215, 192–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, J.; Pei, X.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J. Tribocorrosion performance of TC4 anodized/carbon fiber composite in marine environment. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 32, 762–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonkwo, B.O.; Li, Z.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; You, W.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Han, E.-H. Multifaceted study of the galvanic corrosion behaviour of titanium-TC4 and 304 stainless steel dissimilar metals couple in deep-sea environment. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 517, 145753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tong, X.; Yang, S.; Han, P. Analysis of friction and wear vibration signals in Micro-Textured coated Cemented Carbide and Titanium Alloys using the STFT-CWT method. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 224, 112237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, J.; Xin, L.; Han, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; et al. Fretting wear of alloy 690TT tubes in high-temperature pressurized water: A comparative study under impact, sliding, and impact-sliding motions. Tribol. Int. 2026, 215, 111426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toboła, D.; Chandran, P.; Morgiel, J.; Maj, Ł.; Drenda, C.; Korzyńska, K.; Łętocha, A. Microstructural dependence of tribological properties of Ti-6Al-4V ELI alloy after slide burnishing / shot peening and low-temperature gas nitriding. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2025, 501, 131941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Suo, W.; Wang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Ren, G.; Hu, H.; Huang, L. Enhancing wear resistance, anti-corrosion property and surface bioactivity of a beta-titanium alloy by adopting surface mechanical attrition treatment followed by phosphorus ion implantation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 671, 160766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olugbade, T.O.; Lu, J. Literature review on the mechanical properties of materials after surface mechanical attrition treatment (SMAT). Nano Mater. Sci. 2020, 2, 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Lu, J. Nanostructured surface layer on metallic materials induced by surface mechanical attrition treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 375–377, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajda, S.; Ratuszek, W.; Krzyzanowski, M.; Retraint, D. Inhomogeneity of plastic deformation in austenitic stainless steel after surface mechanical attrition treatment. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2017, 329, 202–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Guo, L.; Ouyang, J.-H. Microstructure and corrosion resistance of modified 2024 Al alloy using surface mechanical attrition treatment combined with microarc oxidation process. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 473–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.A.; Raman, S.G.S.; Narayanan, T.S.; Gnanamoorthy, R.J.A.M.R. Influence of surface mechanical attrition treatment on fretting wear behaviour of Ti-6Al-4V. Adv. Mater. Res. 2012, 463, 316–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eidivandi, S.; Shayegh Boroujeny, B.; Dustmohammadi, A.; Akbari, E. The effect of surface mechanical attrition treatment (SMAT) time on the crystal structure and electrochemical behavior of phosphate coatings. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 821, 153252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Retraint, D.; Baudin, T.; Helbert, A.L.; Brisset, F.; Chemkhi, M.; Zhou, J.; Kanouté, P. Experimental study of microstructure changes due to low cycle fatigue of a steel nanocrystallised by Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment (SMAT). Mater. Charact. 2017, 124, 117–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, X.; Huang, H.; Wang, S.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Deng, H.; Shen, G. FEM-ANN coupling dynamic prediction of residual stresses induced by laser shock peening of TC4 titanium alloy. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 179, 111395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Zhao, J.; Sheng, J.; Meng, X.; Agyenim-Boateng, E.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Zhou, J. Effect of laser peening with different power densities on vibration fatigue resistance of hydrogenated TC4 titanium alloy. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 131, 105335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Guo, N.; Zhu, B.; Shi, X.; Feng, J. Microstructure and properties of underwater laser welding of TC4 titanium alloy. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2020, 275, 116372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhan, L.; Diao, H.; Wang, Y.J.M. Diffusion bonding of Ti6Al4V at low temperature via SMAT. Metals 2022, 12, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behjat, A.; Mosallanejad, M.H.; Shamanian, M.; Taherizadeh, A.; Iuliano, L.; Saboori, A. Surface characteristic of Ti-6Al-4V alloy fabricated by Electron Beam Melting prepared by different surface post treatments. Procedia CIRP 2024, 126, 692–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Xu, F.; Luan, X.; Yu, S.; Guo, B.; Zhang, X.; Xin, L. The effect of load on the fretting wear behavior of TC4 alloy treated by SMAT in artificial seawater. Front. Mater. 2024, 11, 1520286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D1141-98; Standard Practice for Preparation of Substitute Ocean Water. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Chen, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhan, L.; Zhou, T.; Wang, G. Achieving high shear strength and bonding accuracy for diffusion bonding joint of TC4 alloy at low temperature based on SMAT process. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 895, 146192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurel, P.; Weiss, L.; Bocher, P.; Grosdidier, T. Effects of SMAT at cryogenic and room temperatures on the kink band and martensite formations with associated fatigue resistance in a β-metastable titanium alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 803, 140618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Yang, B.B.; Wang, Z.H.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.H.; Shoji, T. Effect of normal force on fretting wear behavior and mechanism of Alloy 690TT in high temperature water. Wear 2016, 368–369, 210–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Lu, Y.; Shoji, T. The role of material transfer in fretting wear behavior and mechanism of Alloy 690TT mated with Type 304 stainless steel. Mater. Charact. 2017, 130, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Input Voltage | Power | Operating Frequency | Working Vessel Vacuum | Processing Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC 380 V | 3 kw | ~50 Hz | >5 Pa (−0.08 MPa) | 100 mm × 100 mm |

| Compound | Chemical Formula | Concentration (g/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Chloride | NaCl | 24.53 |

| Magnesium Chloride | MgCl2 | 5.20 |

| Sodium Sulfate | Na2SO4 | 4.09 |

| Calcium Chloride | CaCl2 | 1.16 |

| Potassium Chloride | KCl | 0.695 |

| Sodium Bicarbonate | NaHCO3 | 0.201 |

| Potassium Bromide | KBr | 0.101 |

| Boric Acid | H3BO3 | 0.027 |

| Strontium Chloride | SrCl2 | 0.025 |

| Sodium Fluoride | NaF | 0.003 |

| Depth from Surface (μm) | Hardness (HV) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 min | 60 min | 120 min | 180 min | 240 min | |

| 10 | 367 | 380 | 410 | 421 | 453 |

| 60 | 364 | 376 | 409 | 410 | 437 |

| 110 | 352 | 371 | 401 | 406 | 419 |

| 160 | 360 | 367 | 386 | 372 | 376 |

| 210 | 371 | 368 | 367 | 357 | 365 |

| 260 | 366 | 362 | 366 | 360 | 361 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Luan, X.; Yu, S.; Liu, Z.; Yin, S.; Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Xin, L. The Effect of Different Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment Time on the Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy in Artificial Seawater. Materials 2026, 19, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010123

Luan X, Yu S, Liu Z, Yin S, Xu F, Zhang X, Xin L. The Effect of Different Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment Time on the Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy in Artificial Seawater. Materials. 2026; 19(1):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010123

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuan, Xiaoxiao, Sujuan Yu, Zhenlin Liu, Shaohua Yin, Feng Xu, Xiaofeng Zhang, and Long Xin. 2026. "The Effect of Different Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment Time on the Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy in Artificial Seawater" Materials 19, no. 1: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010123

APA StyleLuan, X., Yu, S., Liu, Z., Yin, S., Xu, F., Zhang, X., & Xin, L. (2026). The Effect of Different Surface Mechanical Attrition Treatment Time on the Fretting Wear Properties of TC4 Alloy in Artificial Seawater. Materials, 19(1), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010123