Thermal [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with Ethylene, Benzene and Styrene: A MEDT Perspective

Highlights

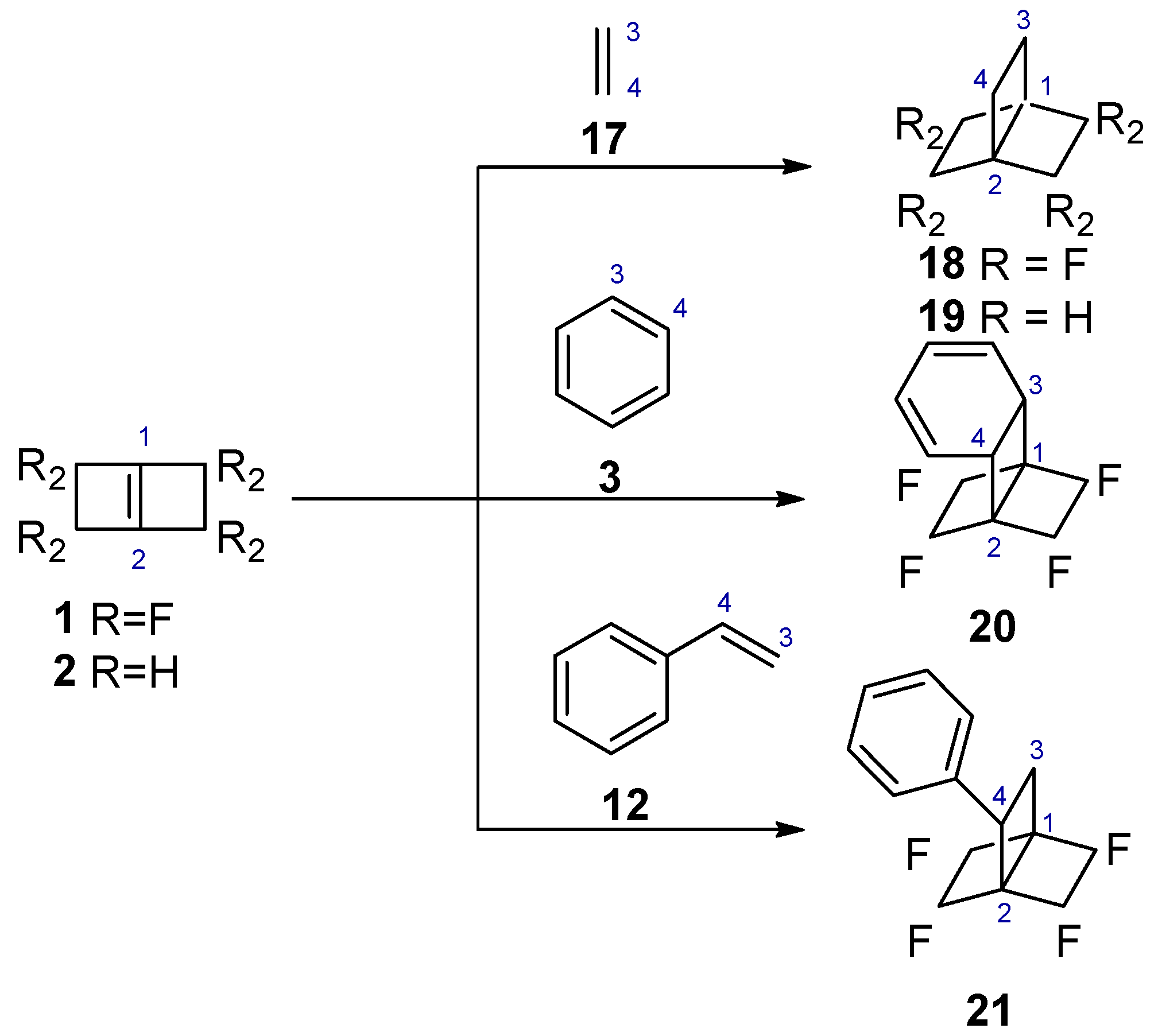

- Thermal [2+2] cycloaddition reactions of perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with ethylene, benzene, and styrene have been researched.

- Thermal [2+2] cycloaddition reactions of bicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with ethylene, benzene, and styrene have been analyzed.

- Thermal [2+2] cycloadditions proceed through a stepwise mechanism.

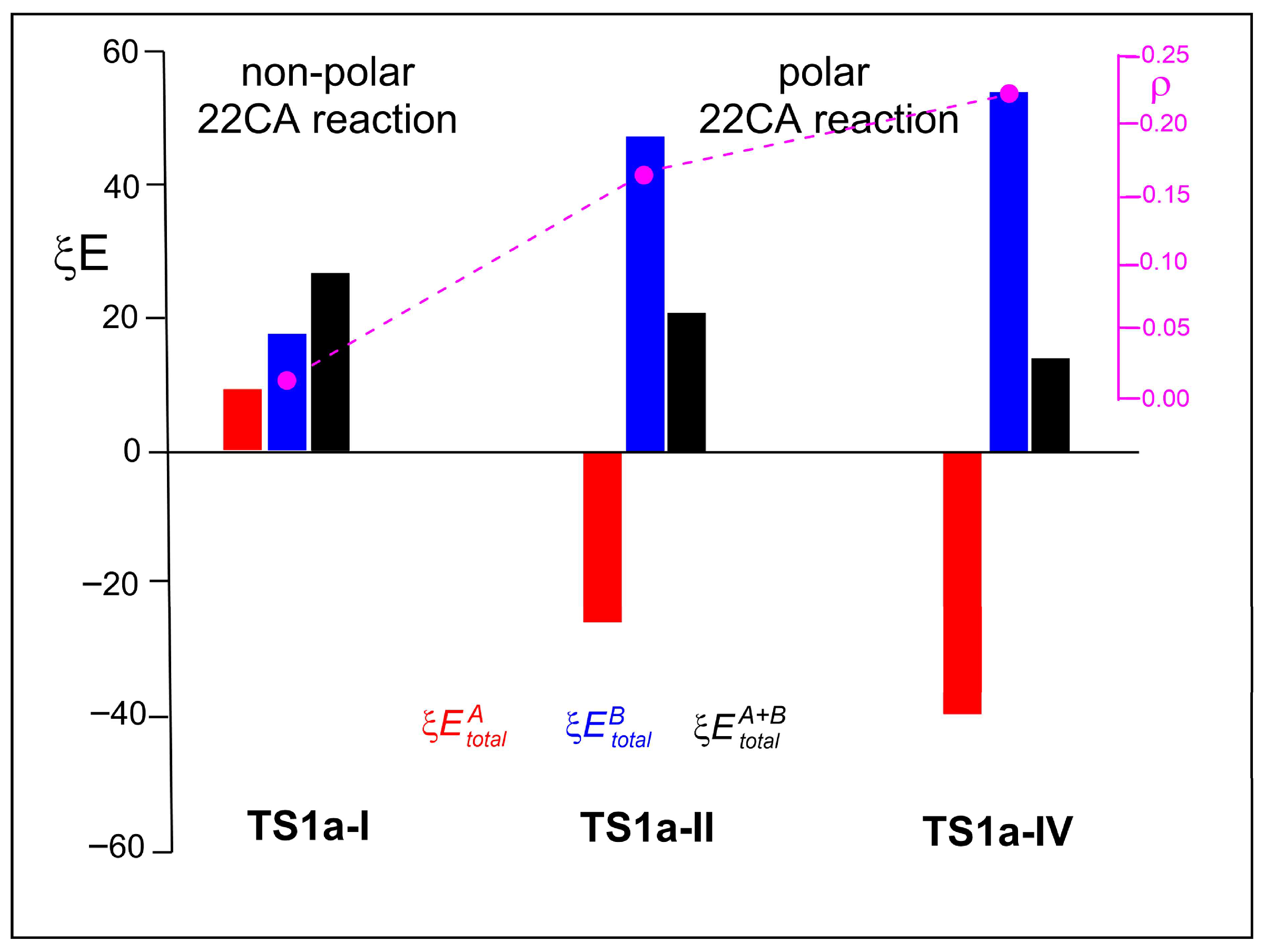

- RIAE analysis shows that the non-polar transition states are electronically destabilized.

- RIAE analysis shows that the polar transition states cause a strong electronic stabilization.

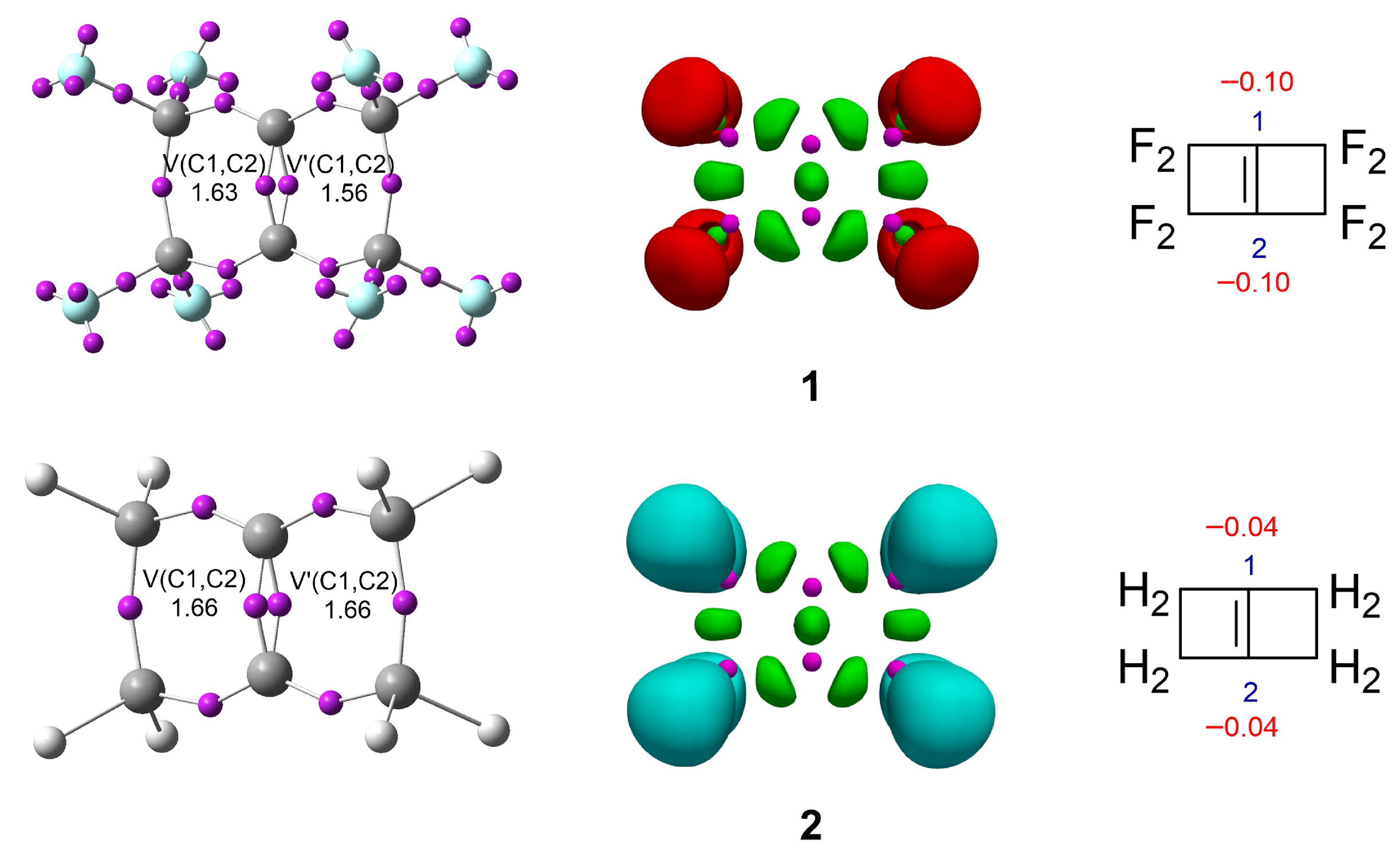

- The presence of the eight fluorines notably increases the electrophilic character of the bicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene.

- ELF analysis of TSs indicates that forming of the first bond has begun, while the forming of the second bond has not begun.

- The analysis of the geometrical parameters of the TS structures and intermediates portrays a great similarity between them.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Details

3. Results and Discussion

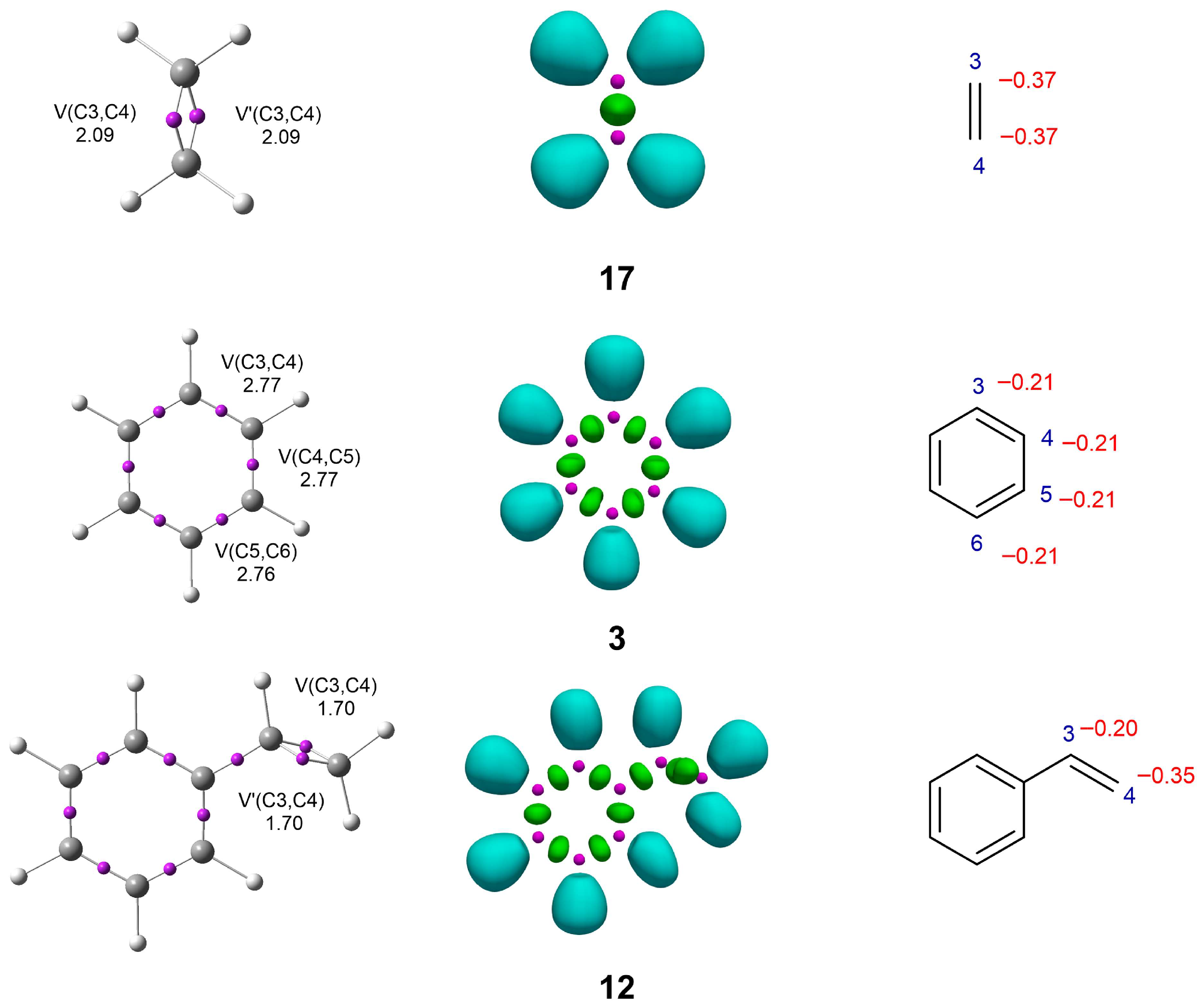

3.1. ELF and NPA Characterization of Reagents

3.2. Research on Reactivity Indices of the Reagents

3.3. Study of the 22CA Reactions of PFBHE 1 and BHE 2 with Ethylene 17, and PFBHE 1 with Benzene 3 and Styrene 12

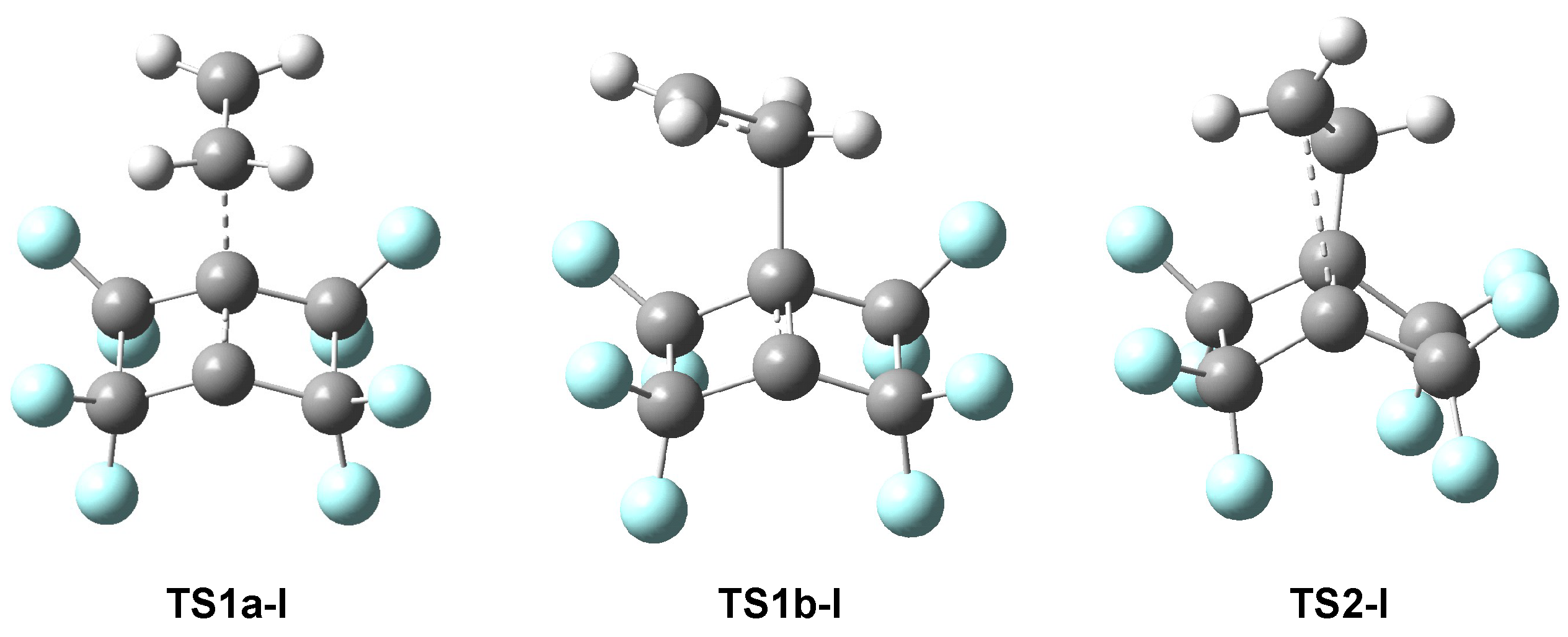

3.3.1. Analysis of the 22CA of PFBHE 1 and BHE 2 with Ethylene 17

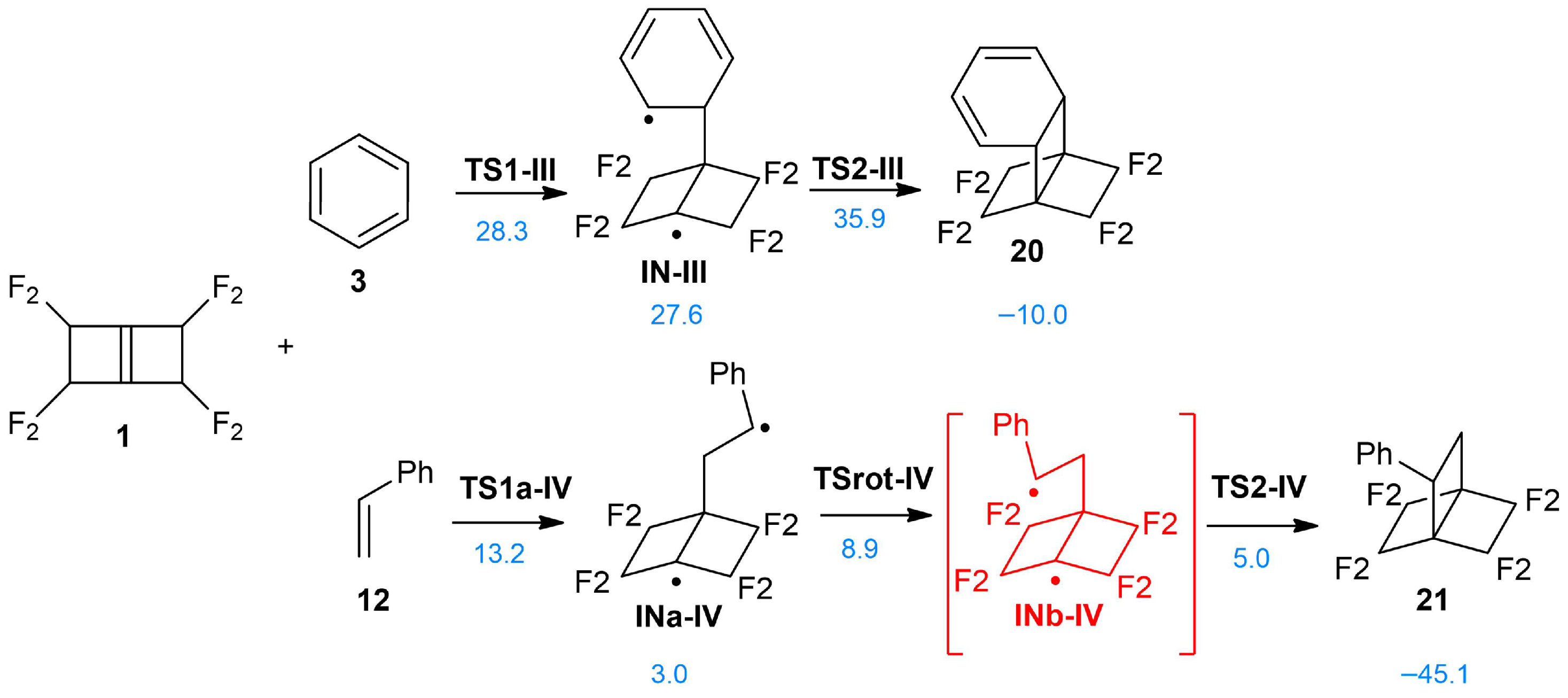

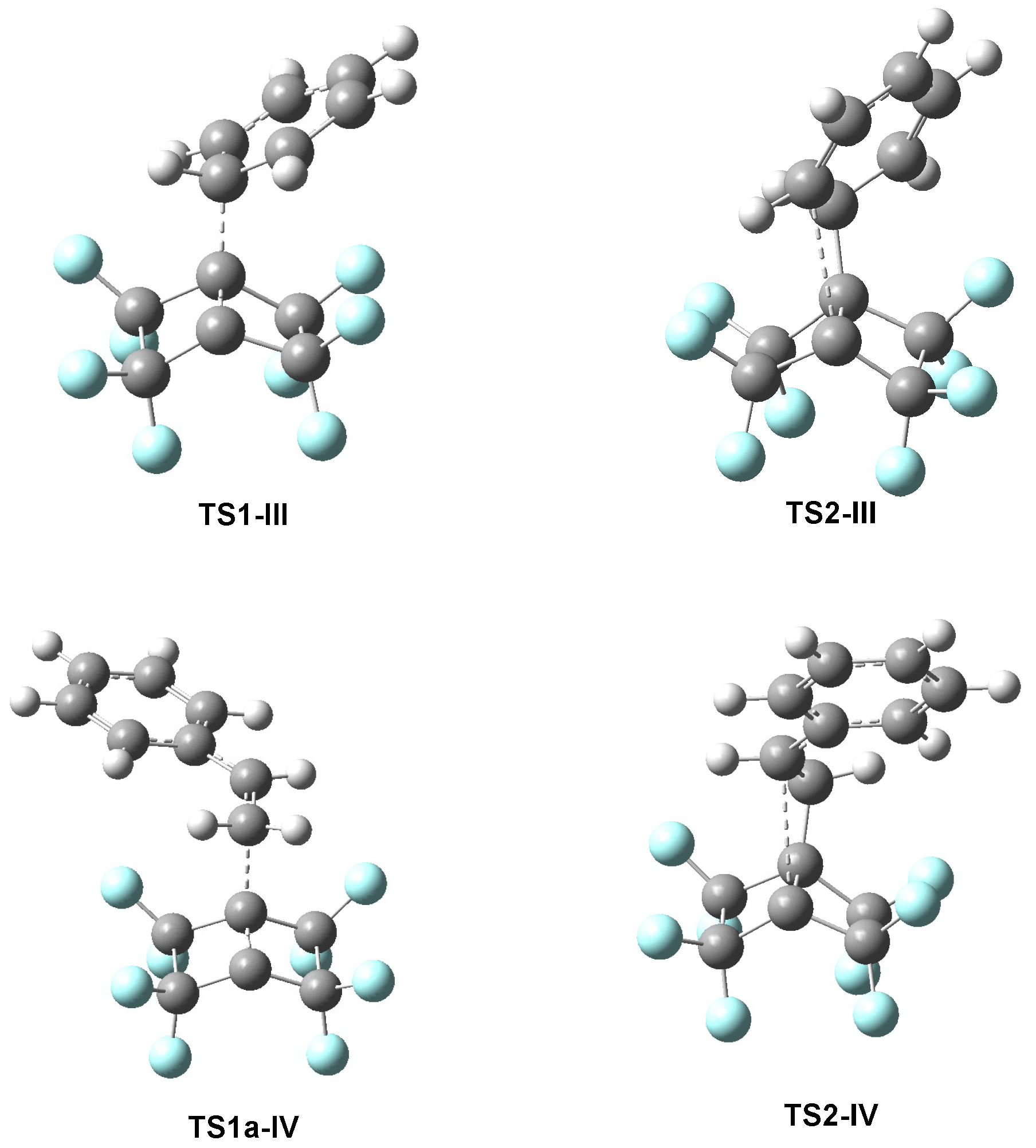

3.3.2. Analysis of the 22CA of PFBHE 1 with Benzene 3 and with Styrene 12

3.4. ELF Topological Analysis of the TSs and Intermediates Involved in the 22CA Reactions

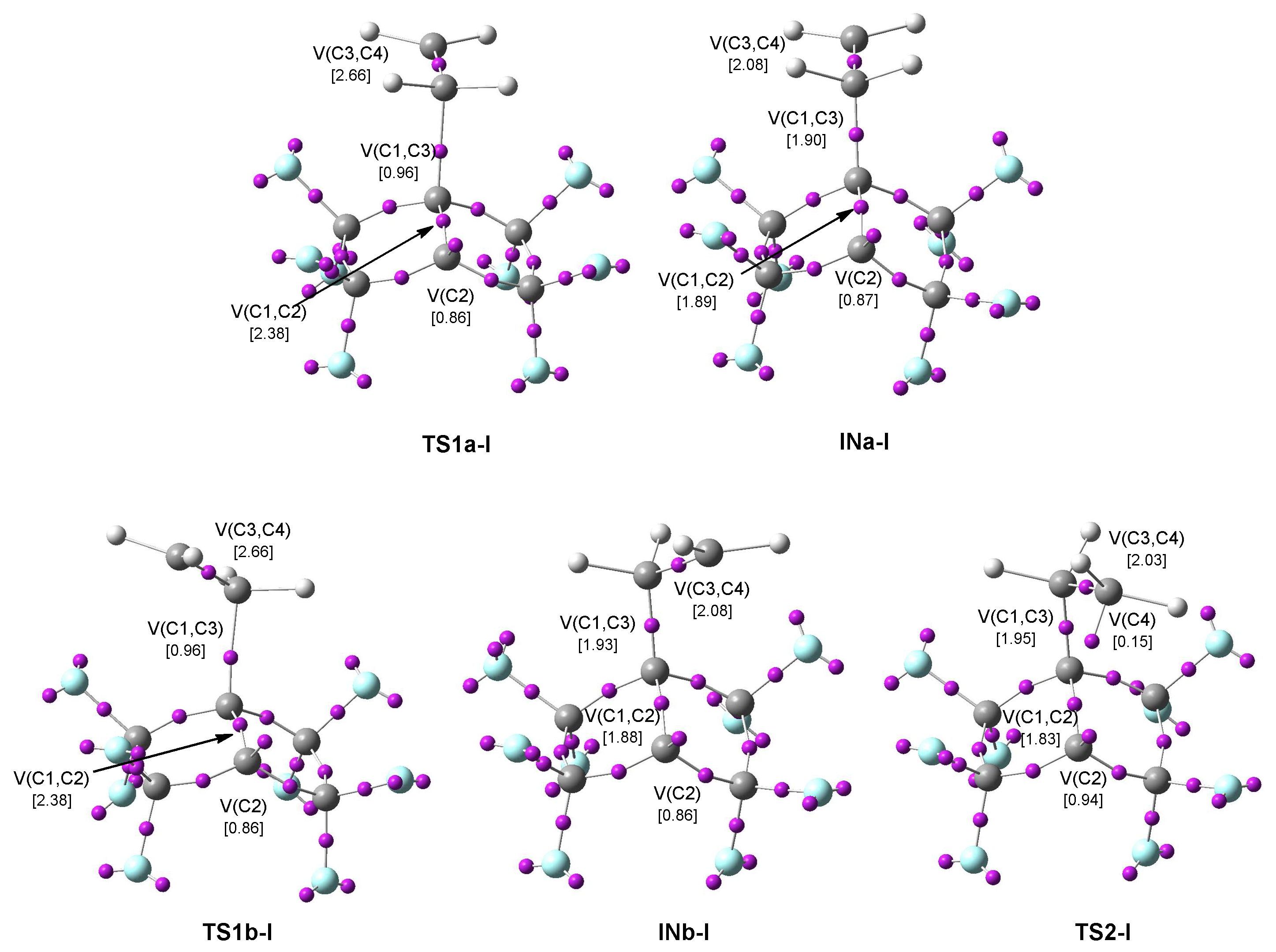

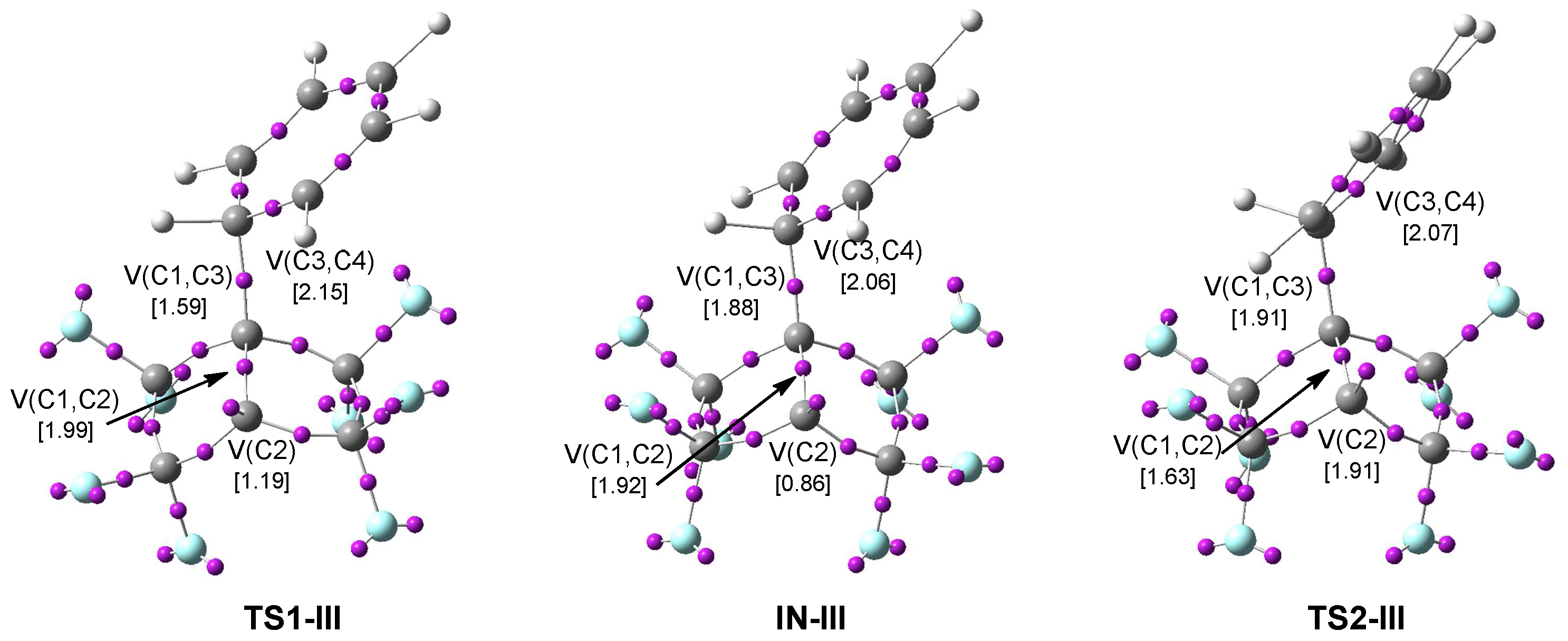

3.4.1. ELF Analysis of the TSs and Intermediates Concerned in the 22CA Reaction Between PFBHE 1 and Ethylene 17

3.4.2. ELF Study of the TSs and Intermediates Participated in 22CA of the BHE 1 and Ethylene 13

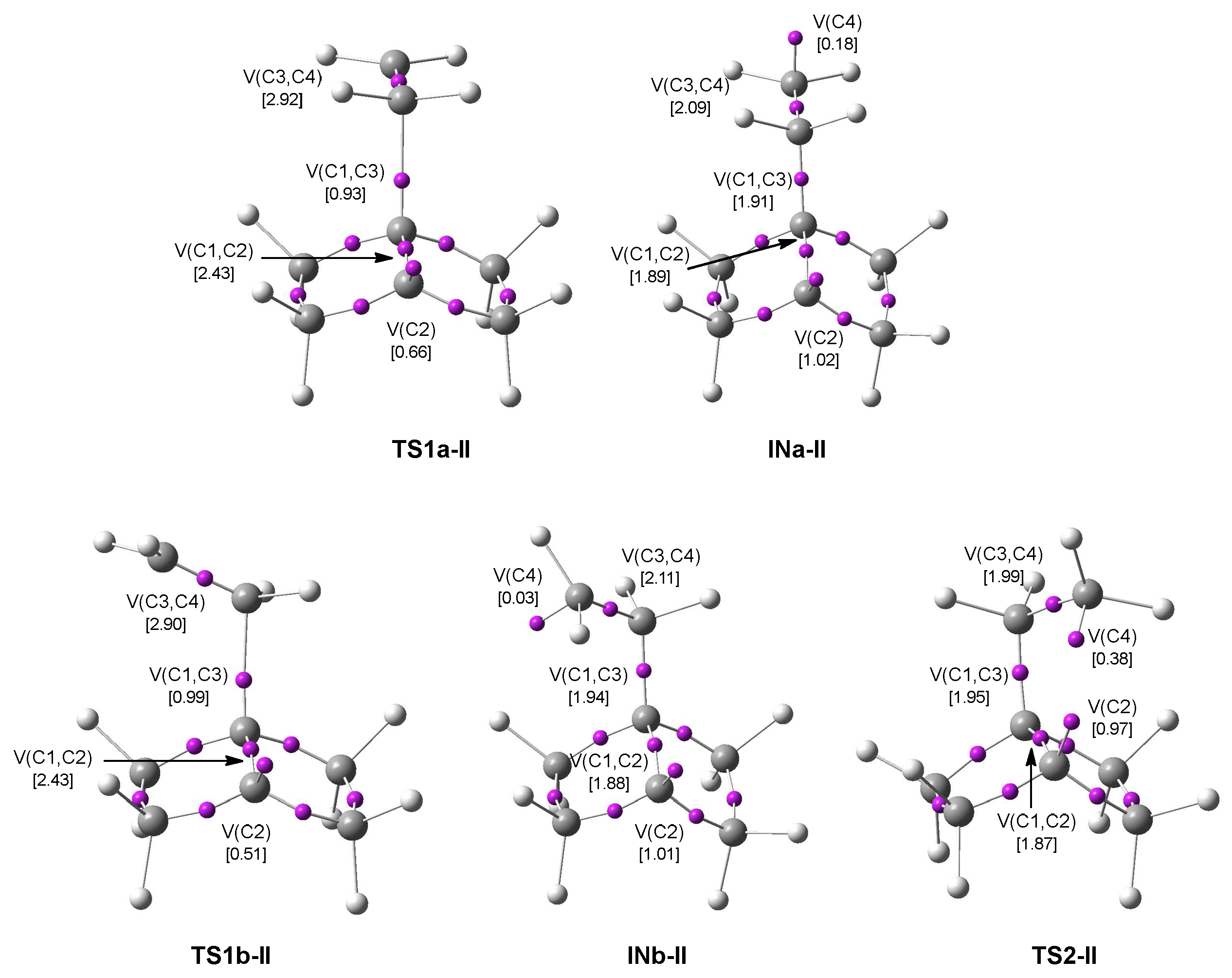

3.4.3. ELF Study of the TSs and Intermediate Participated in the 22CA Between PFBHE 1 and Benzene 3

3.4.4. ELF Study of the TSs and Intermediate Participated in the 22CA of the PFBHE 1 and Styrene 12

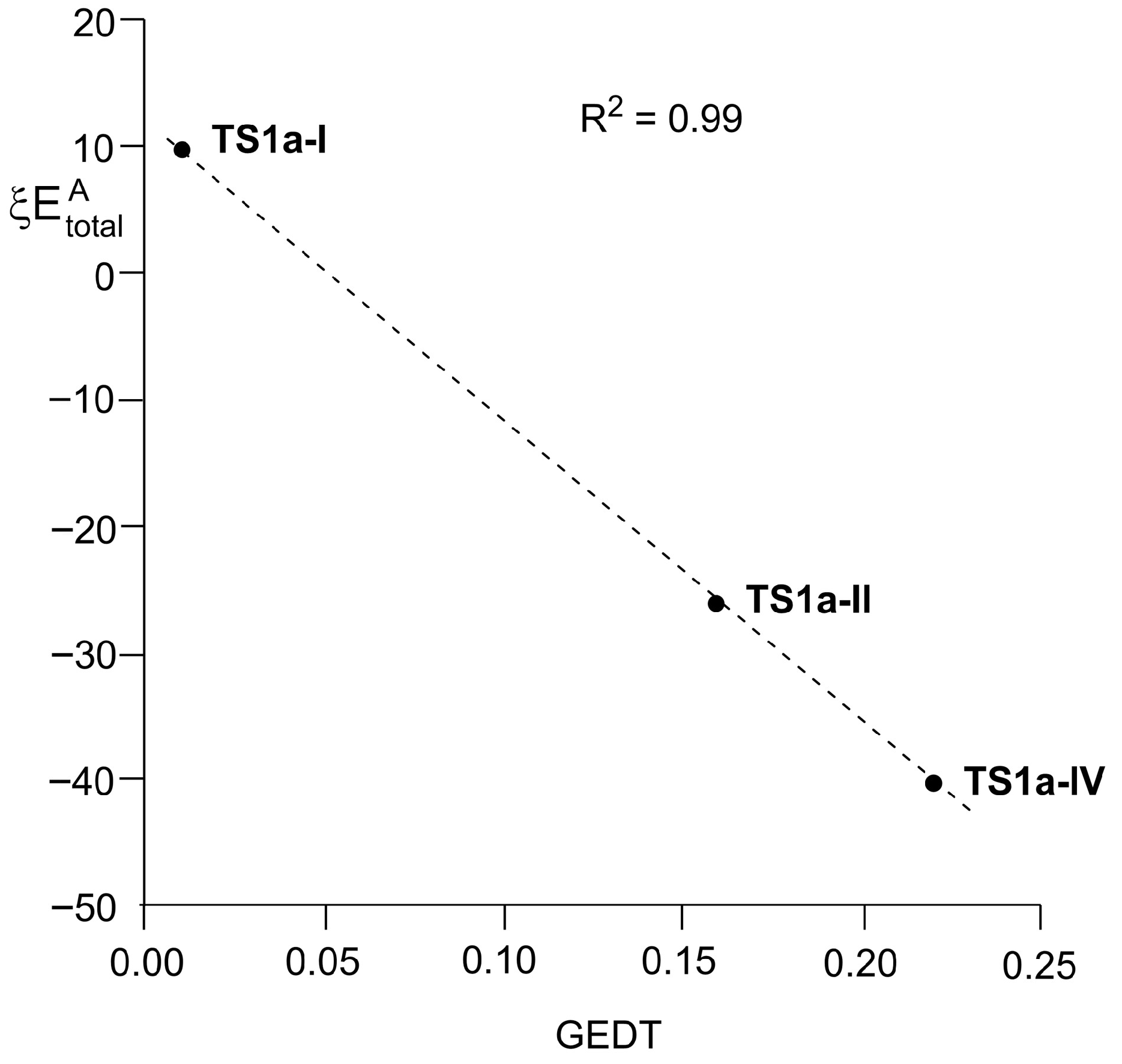

3.5. RIAE Analysis of the Electronic Effects Participating in the Activation Energies Related to the Thermal 22CA Reactions of BHE 2 with Ethylene 17, and Those of PFBHE 1 with Ethylene 17 and Styrene 12

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carruthers, W. Some Modern Methods of Organic Synthesis, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, W. Cycloaddition Reactions in Organic Synthesis; Pergamon: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Diels, O.; Alder, K. Synthesen in der hydroaromatischen Reihe. Justus Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1928, 460, 98–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, K.; Jasiński, R. Synthesis of bis-het(aryl) systems via domino reaction involving (2E,4E)- 2,5-dinitrohexa-2,4-diene: DFT mechanistic consideration. Chem. Heterocycl. Compd. 2024, 60, 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Kula, K. Nitro-functionalised analogues of 1,3-butadiene: An overview of characteristic, synthesis, chemical transformations and biological activity. Curr. Chem. Lett. 2024, 13, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. Molecular Electron Density Theory: A Modern View of Reactivity in Organic Chemistry. Molecules 2016, 21, 1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, Y.; Junk, C.P.; Lemal, D.M. Diels− Alder Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo [2.2. 0] hex-1 (4)-ene with Aromatics. Org Lett. 2023, 5, 2135–2136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A.; Pérez, P. Perfluorobicyclo [2.2. 0] hex-1 (4)-ene as unique partner for Diels–Alder reactions with benzene: A density functional theory study. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2021, 140, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

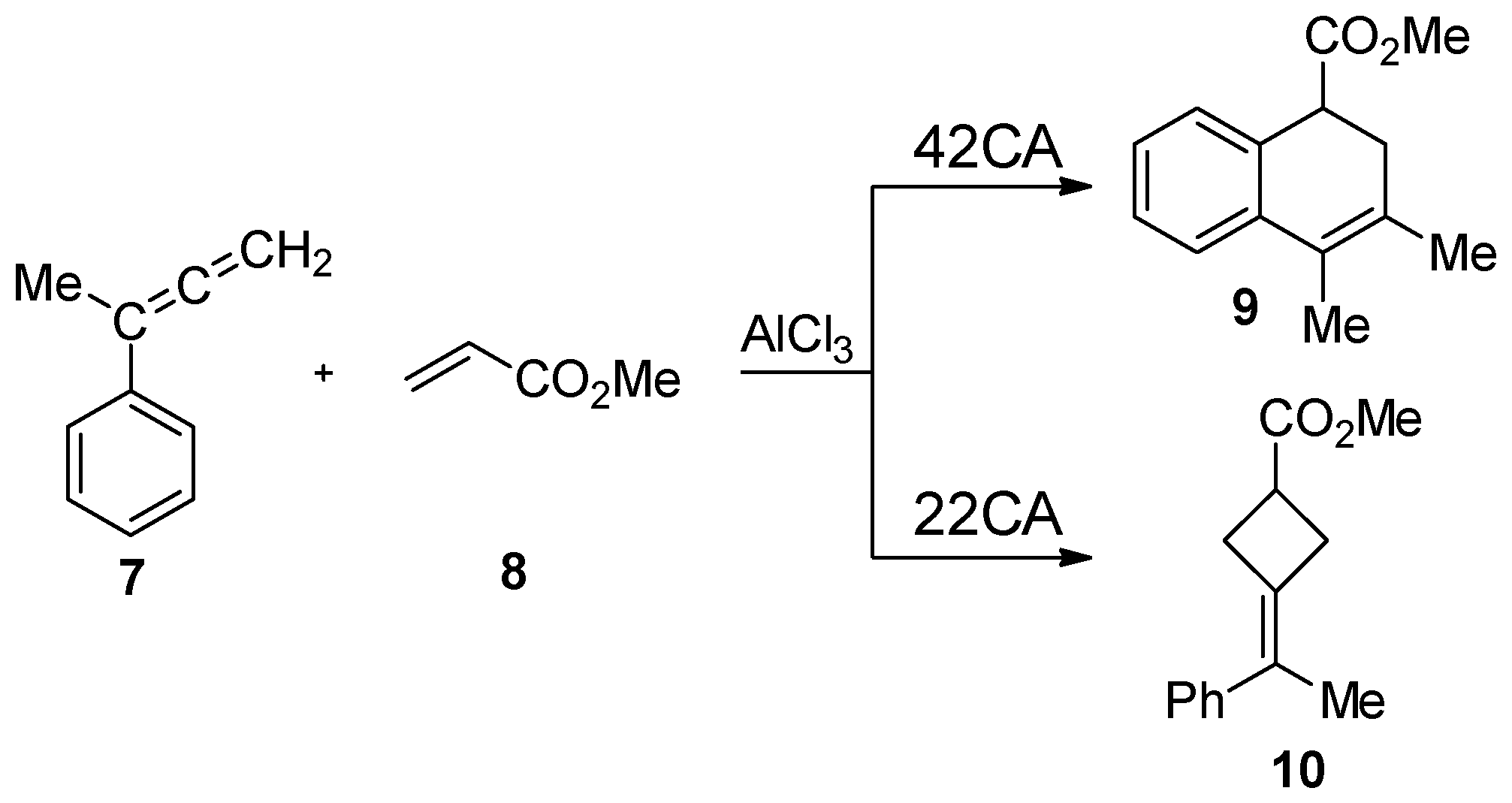

- Barama, L.; Bayoud, B.; Chafaa, F.; Nacereddine, A.K.; Djerourou, A. A mechanistic MEDT study of the competitive catalysed [4+2] and [2+2] cycloaddition reactions between 1-methyl-1-phenylallene and methyl acrylate: The role of Lewis acid on the mechanism and selectivity. Struct. Chem. 2018, 29, 709–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.P.; Lemal, D.M. Competing (4 + 2) and (2 + 2) cycloaddition reactions of tetrafluorothiophene-S, S-dioxide with phenylacetylene: A computational study. J. Fluor. Chem. 2019, 221, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zou, Y.; Li, M.; Tang, Z.; Wang, J.; Tian, Z.; Strassner, N.; Yang, Q.; Zheng, Q.; Guo, Y.; et al. A cyclase that catalyses competing 2 + 2 and 4 + 2 cycloadditions. Nat. Chem. 2023, 15, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, L.T.; Erden, I.; Brunsvold, W.R.; Schultz, T.H.; Houk, K.N.; Paddon-Row, N. Competitive [6 + 2], [4 + 2], and [2 + 2] cycloadditions. Experimental classification of two-electron cycloaddends. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 3659–3664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adachi, S.; Horiguchi, G.; Kamiya, H.; Okada, Y. Photochemical radical cation cycloadditions of aryl vinyl ethers. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2022, 44, e202201207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

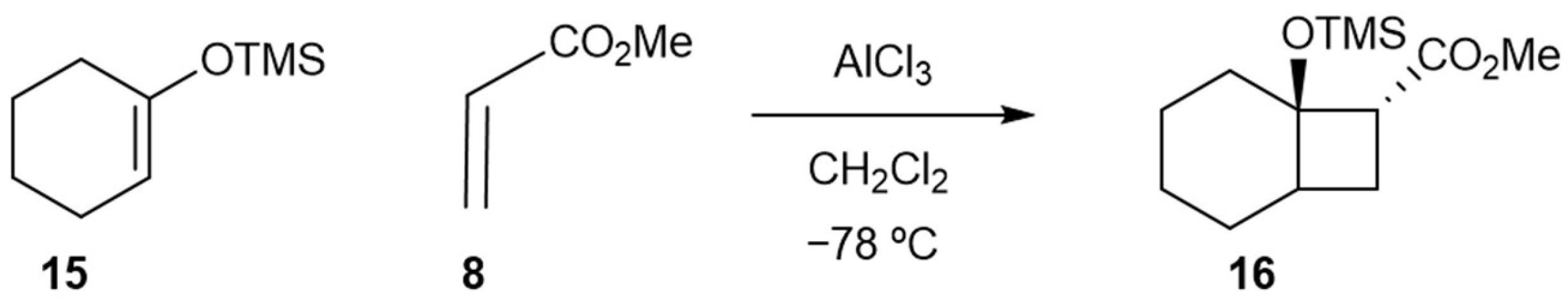

- Takasu, K.; Ueno, M.; Inanaga, K.; Ihara, M. Catalytic (2 + 2)-cycloaddition reactions of silyl enol ethers. A convenient and stereoselective method for cyclobutane ring formation. J. Org. Chem. 2004, 69, 517–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnó, M.; Zaragozá, R.J.; Domingo, L.R. Lewis Acid Induced [2+ 2] Cycloadditions of Silyl Enol Ethers with α, β-Unsaturated Esters: A DFT Analysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005, 18, 3973–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, M.A.; Pendás, A.M.; Francisco, E. Interacting quantum atoms: A correlated energy decomposition scheme based on the quantum theory of atoms in molecules. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 1096–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. Understanding the Electronic Effects of Lewis Acid Catalysts in Accelerating Polar Diels–Alder Reactions. J. Org. Chem. 2024, 89, 12349–12359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bader, R.F.W.; Tang, Y.H.; Tal, Y.; Biegler-König, F.W. Properties of atoms and bonds in hydrocarbon molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1982, 104, 946–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hohenberg, P.; Kohn, W. Inhomogenndeous Electron Gas. Phys. Rev. 1964, 136, B864–B871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohn, W.; Sham, L.J. Self-Consistent Equations Including Exchange and Correlation Effects. Phys. Rev. 1965, 140, A1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, J.-D.; Head-Gordon, M. Long-range corrected hybrid density functionals with damped atom–atom dispersion corrections. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 6615–6620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Truhlar, D.G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: Two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215–241. [Google Scholar]

- Hehre, M.J.; Radom, L.; Schleyer, P.Y.R.; People, J. Ab Initio Molecular Orbital Theory; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Becke, A.D.; Edgecombe, K.E. A simple measure of electron localization in atomic and molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1990, 92, 5397–5403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A.; Jasiński, R. Unexpected molecular mechanism of trimethylsilyl bromide elimination from 2-(trimethylsilyloxy)-3-bromo-3-methyl-isoxazolidines. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2019, 138, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kącka-Zych, A.; Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Jasiński, R. Understanding the mechanism of the decomposition reaction of nitroethyl benzoate through the Molecular Electron Density Theory. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2017, 136, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvi, B.; Savin, A. Classification of chemical bonds based on topological analysis of electron localization functions. Nature 1994, 371, 683–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Weinstock, R.B.; Weinhold, F. Natural population analysis. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 735–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular interactions from a natural bond orbital, donor-acceptor viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R. A New C-C Bond Formation Model Based on the Quantum Chemical Topology of Electron Density. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 32415–32428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. Applications of the Conceptual Density Functional Theory Indices to Organic Chemistry Reactivity. Molecules 2016, 21, 748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parr, R.G.; Szentpály, L.V.; Liu, S. Electrophilicity index. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999, 121, 1922–1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Chamorro, E.; Pérez, P. Understanding the reactivity of captodative ethylenes in polar cycloaddition reactions. A theoretical study. J. Org. Chem. 2008, 73, 4615–4624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Sáez, J.A. Understanding the local reactivity in polar organic reactions through electrophilic and nucleophilic Parr functions. RSC Adv. 2013, 3, 1486–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. Useful Classification of Organic Reactions Bases on the Flux of the Electron Density. Sci. Rad. 2023, 2, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, R.B.; Hoffmann, R. Selection Rules for Concerted Cycloaddition Reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1965, 87, 2046–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Pérez, P. A molecular electron density theory study of the enhanced reactivity of aza aromatic compounds participating in Diels–Alder reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 18, 292–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingo, L.R.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M. Revealing the Critical Role of Global Electron Density Transfer in the Reaction Rate of Polar Organic Reactions within Molecular Electron Density Theory. Molecules 2024, 29, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pendás, A.M.; Blanco, M.A.; Francisco, E. Chemical fragments in real space: Definitions, properties, and energetic decompositions. J. Comput. Chem. 2007, 28, 161–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triestram, L.; Falcioni, F.; Popelier, P.L.A. Interacting Quantum Atoms and Multipolar Electrostatic Study of XH··· π Interactions. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 34844–34851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, L.R.; Pérez, P.; Ríos-Gutiérrez, M.; Aurell, M.J. A molecular electron density theory study of hydrogen bond catalysed polar Diels–Alder reactions of α, β-unsaturated carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron Chem. 2024, 10, 100064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.B. Optimization of equilibrium geometries and transition structures. J. Comput. Chem. 1982, 3, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, H.B. Modern Electronic Structure Theory; Yarkony, D.R., Ed.; World Scientific Publishing: Singapore, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Fukui, K. Formulation of the reaction coordinate. J. Phys. Chem. 1970, 74, 4161–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Schlegel, H.B. Reaction path following in mass-weighted internal coordinates. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 5523–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, C.; Schlegel, H.B. Improved algorithms for reaction path following: Higher-order implicit algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 1991, 95, 5853–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasi, J.; Persico, M. Molecular interactions in solution: And overview of methods based on continuous distributions of the solvent. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2027–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simkin, B.I.; Sheikhet, I.I. Quantum Chemical and Statistical Theory of Solutions–Computational Approach; Ellis Horwood: London, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cossi, M.; Barone, V.; Cammi, R.; Tomasi, J. Ab initio study of solvated molecules: A new implementation of the polarizable continuum model. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 255, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cances, E.; Mennucci, B.; Tomasi, J. A new integral equation formalism for the polarizable continuum model: Theoretical background and applications to isotropic and anisotropic dielectrics. J. Chem. Phys. 1997, 107, 3032–3041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barone, V.; Cossi, M.; Tomasi, J. Geometry optimization of molecular structures in solution by the polarizable continuum model. J. Comput. Chem. 1998, 19, 404–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parr, R.G.; Yang, W. Density Functional Theory of Atoms and Molecules; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Sadowski, M.; Kula, K. Unexpected course of reaction between (1E,3E)-1,4-dinitro-1,3-butadiene and N-methyl azomethine ylide—A comprehensive experimental and quantum-chemical study. Molecules 2024, 29, 5066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowski, M.; Synkiewicz-Misualska, B.; Kula, K. (1E,3E)-1,4-dinitro-1,3-butadiene—Synthesis, spectral characteristics and computational study based on MEDT, ADME and PASS simulation. Molecules 2024, 29, 542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Noury, S.; Krokidis, X.; Fuster, F.; Silvi, B. Computational tools for the electron localization function topological analysis. Comput. Chem. 1999, 23, 597–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A. TK Gristmill Software, Version 19.10.12; AIMAll: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2019. Available online: https://aim.tkgristmill.com/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Dennington, R.; Keith, T.A.; Millam, J.M. GaussView, Version 6.1; Semichem Inc.: Shawnee Mission, KS, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

| µ | η | ω | N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | −5.38 | 6.96 | 2.08 | 0.26 |

| 12 | −3.43 | 5.20 | 1.13 | 3.09 |

| 3 | −3.30 | 6.80 | 0.80 | 2.42 |

| 17 | −3.37 | 7.76 | 0.73 | 1.87 |

| 2 | −2.46 | 7.41 | 0.41 | 2.95 |

[eV] | ωk [eV] | [eV] | Nk [eV] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | C1 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| C2 | 0.48 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | |

2 | C1 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 1.33 |

| C2 | 0.49 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 1.33 | |

12 | C3 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| C4 | 0.47 | 0.53 | 0.50 | 1.54 | |

| Structure | Interatomic Distance | GEDT [e] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1–C2 | C3–C4 | C1–C3 | C2–C4 | ||

| 1 | 1.326 | ||||

| 17 | 1.325 | ||||

| TS1a-I | 1.829 | 3.899 | 0.16 | ||

| TS1b-I | 1.846 | 3.412 | 0.15 | ||

| INa-I | 1.529 | 3.980 | 0.23 | ||

| INb-I | 1.529 | 3.101 | 0.24 | ||

| TS2-I | 1.516 | 2.693 | 0.20 | ||

| 18 | 1.546 | 1.546 | |||

| 2 | 1.313 | ||||

| TS1a-II | 1.908 | 3.997 | 0.01 | ||

| TS1b-II | 1.893 | 3.586 | 0.03 | ||

| INa-II | 1.527 | 3.977 | 0.04 | ||

| INb-II | 1.520 | 3.181 | 0.03 | ||

| TS2-II | 1.517 | 2.485 | 0.00 | ||

| 19 | 1.546 | 1.546 | |||

| Structure | Interatomic Distances | GEDT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1–C2 | C3–C4 | C1–C3 | C2–C4 | ||

| 1 | 1.326 | ||||

| 3 | 1.391 | ||||

| TS1-III | 1.631 | 3.202 | 0.29 | ||

| IN-III | 1.549 | 3.203 | 0.33 | ||

| TS2-III | 1.527 | 2.598 | 0.35 | ||

| 18 | 1.557 | 1.562 | |||

| 12 | 1.331 | ||||

| TS1a-IV | 1.825 | 3.896 | 0.22 | ||

| INa-IV | 1.526 | 3.979 | 0.34 | ||

| TS2-IV | 1.520 | 2.717 | 0.28 | ||

| 19 | 1.543 | 1.567 | |||

| ƒ(X) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS1a-I | A BHE | 9.9 | −0.2 | 9.7 | 27.3 |

| B ethylene | 23.0 | −5.4 | 17.6 | ||

| TS1a-II | A PFBHE | −116.3 | 89.9 | −26.5 | 21.9 |

| B ethylene | 35.5 | 12.9 | 48.3 | ||

| TS1a-IV | A PFBHE | −160.1 | 120.0 | −40.2 | 14.3 |

| B styrene | 42.4 | 12.1 | 54.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kącka-Zych, A.; Domingo, L.R. Thermal [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with Ethylene, Benzene and Styrene: A MEDT Perspective. Materials 2025, 18, 5675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245675

Kącka-Zych A, Domingo LR. Thermal [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with Ethylene, Benzene and Styrene: A MEDT Perspective. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245675

Chicago/Turabian StyleKącka-Zych, Agnieszka, and Luis R. Domingo. 2025. "Thermal [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with Ethylene, Benzene and Styrene: A MEDT Perspective" Materials 18, no. 24: 5675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245675

APA StyleKącka-Zych, A., & Domingo, L. R. (2025). Thermal [2+2] Cycloaddition Reactions of Perfluorobicyclo[2.2.0]hex-1(4)-ene with Ethylene, Benzene and Styrene: A MEDT Perspective. Materials, 18(24), 5675. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245675