1. Introduction

One of the major flaws of the alloy cast solidifying under terrestrial gravity is its chemical inhomogeneity, known as solute macro-segregation. This phenomenon is attributed to the solute segregation at the individual grains’ scale due to different solute solubility in the liquid and solid phases and then to convective transport of the excess solute, the solidification shrinkage, and the relative motion of the liquid and solid phases at the whole cast’s scale. Thus, the evolution of a non-uniform distribution of the solute concentration and highly solute-reach long and narrow channels, which post-solidification thermal manufacturing processes can hardly remove, considerably deteriorates the quality of alloy casting products.

In this context, manufacturing of metal alloy casts in the centrifugal field has attracted foundry engineers and researchers, as the high-speed rotation enhances melt flow and significantly alters the processes of heat and solute transfer at both the grain’s and the whole cast’s scales, thus changing the developing dendrite structures, solute distributions, and the macro-segregation pictures. Therefore, for the last decades, vast experimental research has been conducted all over the world to comprehend better the role of strength and directions of centrifugal forces in complex transport processes occurring in metal alloy solidification and to search for appropriate conducting of the centrifugal casting process to obtain the product of satisfactory grain structure and mechanical properties.

From the research papers [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] and several others available in the worldwide literature involving in situ and real-time observations of various metal alloy samplings solidifying in the hyper-gravity field, it comes out that final grain structures and thermo-mechanical properties of the cast are subject to many mold and processing factors, such as cast dimensions, direction and speed of rotation and temperature gradient, the solidification rate, the composition of the molten alloy and others. So, for a high-quality product of hyper-gravity casting, it is essential to tailor this specialized manufacturing method by continuously monitoring and optimizing its process parameters.

For this purpose, a complete understanding and detailed knowledge of multi-scale heat and mass transfer processes are needed, including the role of external forces in developing chemical inhomogeneity in the final product of centrifugal casting. However, such a complete study is not possible only through cumbersome, expensive, and time-consuming experiments. Several advanced models of computer simulation of heat and mass transfer processes occurring at the scale of individual grains (the mesoscopic scale) and the whole casting product (the macro-scale) have been developed in the last two decades to assist this cognitive endeavor significantly.

Computer simulations at the mesoscopic scale of individual grains, based on the phase-field method (e.g., [

9,

10]), Cellular Automaton and the Lattice Boltzmann methods (e.g., [

11]), show that the melt flow modulated under the hyper-gravity conditions significantly affects the grain nucleation, interface instability, constitutional undercooling, the primary dendrite arms spacing (PDAS) and growth of columnar and equiaxed crystals, their migration and the phenomenon of Columnar–to-Equiaxed Transition (CET), and thus gives the potential for grain refinement.

But the chemical heterogeneity at the scale of individual grains, inherent to the difference in solubility at the liquid–solid interface and non-equilibrium solidification, while associated with the relative motion of the liquid and solid phases, (caused by thermosolutal convection, solidification shrinkage, grains sedimentation) leads to the solute macro-segregation developing in a whole cast domain containing an enormous number of grains. Here, computer simulation models used at the grain’s scale would require a tremendous and unavailable burden of computer resources nowadays. Therefore, meso-macroscopic modeling has been developed, where key calculations are performed on the macroscopic scale, and information about the developing grains’ structures is transferred to the macroscopic model through the effective properties of the two-phase region, the so-called mushy zone. Several such multi-scale computer simulation models have been proposed in the last three decades to predict compositional macro-segregation of chemical species in terrestrial gravity conditions. Macroscopic conservation equations of mass, momentum, energy, and species concentration are based on the mixture theory (e.g., Bennon and Incropera [

12], Ni and Incropera [

13]) or volume averaging (e.g., Beckermann and Viskanta [

14]).

The mushy zone is formed in non-isothermal alloy solidification, where the competing columnar and equiaxed/globular grain structures develop. Motionless columnar dendrites are immersed in a molten alloy; in the other part of the mushy zone, equiaxed/ globular grains are suspended or/and transported in the alloy melt, and the CET can develop in the proceeding solidification. Various models of the mushy zone’s permeability have been proposed and supplemented to the macroscopic calculations of the transport equations. Some researchers treat the whole two-phase region as Darcy’s porous medium using the Kozeny–Carman model of permeability (e.g., Založnik and Combeau [

15], Kumar et al. [

16], Cao et al. [

17]). Li et al. [

18] simulated macro-segregation during directional solidification of TiAl ingots in the external magnetic field. They applied the enthalpy–porosity model, based on the two-phase mixture approach, and calculated it on a 2D finite element mesh. They treated the entire mushy zone as a columnar porous medium, where equiaxed crystals were absent. Xu et al. [

19] employed a volume-averaged mixed columnar–equiaxed enthalpy–porosity model for the solidification of a titanium-based alloy in a strong electromagnetic field. They have shown that although the melt flow induced by thermo-solute natural convection is visibly weaker than that resulting from electromagnetic forces, buoyancy convection remains crucial for the developing spatial pattern of solute macro-segregation. However, they assumed that the mushy zone, with a solid volume fraction range of 0.01–0.9, consists of only columnar dendrite grains and the liquid melt.

The others distinguish zones of columnar and equiaxed grains, where different models of the resistance to melt flow are applied. Recently, Xu et al. [

20] used the Eulerian meso-macroscopic model where the liquid, columnar dendrite, and equiaxed grain phases were treated separately to analyze the macro-segregation pictures in an Al-4.34 wt.% Cu billet. They applied two different criteria for separating the columnar and equiaxed regions in the mushy zone. The equiaxed grains were trapped by the columnar ones when the sum of solid fractions of both these dendritic structures exceeded the value of 0.637 or when the volume fraction of columnar phase rose over 0.2.

In many research papers, these two different grain structures are identified by the inspection of the solid fraction value in the mushy zone (e.g., Ilegbusi and Mat [

21], Vreeman and Incropera [

22], Krane [

23], Zhang et al. [

24]). When it exceeds the dendrite coherency point (DCP) value, Darcy’s flow model with the permeability concept is used; otherwise, the pseudo-viscosity [

17] or semi-solid medium [

21] models are applied. Alternatively, Banaszek and Seredyński [

25] have proposed the replacement of the DCP model used in the identification of different dendritic structures by the direct tracking of a virtual surface, being a locus of the columnar dendrite tips and moving according to the local law of crystal growth on a fixed non-structural control-volume mesh. They have compared both models in the prediction of the solute macro-segregation pictures of Pb-Sn alloys solidifying in the rectangular cavities under the terrestrial gravity and concluded that the predicted channel segregates are prone to the used control-volume mesh, the applied permeability formula, and the method of separating different dendritic structures within the mushy zone (Seredynski and Banaszek [

26]).

However, the research reported so far on computer simulations of transport processes accompanying the centrifugal casting is less extensive than that concerning the process in terrestrial gravity conditions. It is mainly concerned with the pouring process; only a few research papers have addressed the issue of the effect of the strength and direction of hyper-gravity on the solute inhomogeneity developing throughout the whole cast at different stages of the centrifugal casting.

Daloz et al. [

27] have developed a 2D axisymmetric multi-scale computer simulation model for the centrifugally cast Al-Ti cylindrical sample. The proposed simulation is based on the volume-averaged Euler–Euler two-phase approach, where macroscopic thermal and solute convection calculations are coupled with microscopic nucleation and crystal growth models. Based on the analysis of the strength of terrestrial gravity, Coriolis, and centrifugal forces, only the latter has been taken into account in the calculations. The coherency point approach has been used to distinguish the zones of stationary columnar dendrites and moving equiaxed grains. Battaglioli et al. [

28] have developed a 2D computer simulation for predicting the influence of gravity strength on the evolution of fluid flow, temperature, and grain structures during the directional solidification of Ti-Al alloy on a centrifuge. The model is based on a single set of transport equations in the solid–liquid mixture, discretized on a structural control-volume mesh in the plane perpendicular to the rotation axis. The front tracking procedure is applied to trace the developing columnar dendrites zone, where the porous medium model is exploited. This research study omitted consideration of solute convection, and macro-segregation was not analyzed. Pan et al. [

29] have developed a 3D macroscopic model for the centrifugal investment casting of large-sized titanium alloy components. The proposed computer simulation is based on discretizing macroscopic mass, momentum, and energy transport equations on a non-conformal finite difference mesh. The 3D numerical simulation of the directional columnar solidification of Ti-Al alloys (consistent with the configuration of ESA GRADECET experiments) is presented by Fernández et al. in [

30,

31]. The applied volume-averaging model accounts for thermo-solutal convection, centrifugal, and Coriolis accelerations when the temperature gradient along the cylindrical sample is antiparallel to the total apparent gravity (sum of centrifugal and terrestrial gravity). The Kozeny–Carman hydrodynamic permeability of the columnar mushy zone and Boussinesq’s model for thermo-solutal buoyancy forces have been adopted. The research is, however, restricted only to the development of the columnar dendrites during directional solidification. Lv et al. [

6] have presented the numerical analysis of the mold-filling process and solidification of a wedge-shaped Al-Cu cast under horizontal centrifugation.

Their micro-macroscopic model adopted the cellular automaton method to calculate the grain nucleation, which was coupled with the finite element calculations of macroscopic transport processes. The presented parametric analysis concentrated only on the impact of centrifugal forces on the cast’s microstructure changes and confirms that the increase in rotation speed and the higher cooling rate cause the reduction in grain average sizes and the secondary dendrite arm spacing.

The combined experimental research and computer simulations have led to significant progress in understanding the role of enhanced melt flow in a centrifuge. Despite these two-decade efforts, more still has to be performed to achieve a better quantitative understanding of complex multi-scale processes deciding about grains’ micro and macro structures of hyper-gravity casting products. Among still open scientific questions, there is the influence of the interaction between the enhanced flow of melt and the Coriolis acceleration on convection and the growth of solidification microstructures [

9,

10,

32], the mechanisms behind columnar crystals progress [

4], and the macro-segregation developing at different hyper-gravity casting stages [

5,

30,

32]. Also, since numerical modeling is a primary potential source of valuable information on enhancing the reliability of the whole casting process, improving the accuracy and trustworthiness of multi-scale computer simulations of solute segregation under the centrifugal and Coriolis forces remains a challenge. The enhanced mesoscopic simulations [

9,

10,

11] give a deep insight and much better understanding of the impact of the strength and orientation of hyper-gravity and the augmented melt flow on the PDAS, the growth of single and multiple columnar and equiaxed dendritic crystals, and the other micro and mesoscopic characteristics of the mushy zone. On the other hand, the above-discussed filling process and mechanical defects (e.g., [

6,

27,

29]), and the directional solidification with the imposed thermal gradient direction (e.g., [

29]), do not take into account the terrestrial gravity (e.g., [

27]), Coriolis acceleration (e.g., [

26,

27]), the thermo-solutal buoyancy (e.g., [

7,

27,

28,

29]) and the different dendritic structures and the CET developing in the mushy zone (e.g., [

30,

31]).

So efforts should be continued to develop further advanced computer simulations involving more accurate predictions of the solute macro-segregation and channeling phenomena under hyper-gravity, where the melt flow process is more complex and changeable than in gravity casting, and thus to frame reliable correlations between hyper-gravity forces and the resulting grain structures and chemical and mechanical properties of the centrifugal casting product.

The presented paper is the authors’ contribution to this current research area, in which the issue of the role of the assumed model of mushy zone in predicting reliable pictures of solute macro-segregation in hyper-gravity is discussed. For this purpose, three different meso-macroscopic simulations, based on the single-domain enthalpy–porosity approach, are compared, each coupled with distinct models of flow resistance in the mushy zone. In the first, the whole two-phase zone is treated as a Darcy’s porous medium (EP model); in the other two, the columnar and equiaxed grain structures are distinguished using either the coherency point (EP-CP model) approach or by tracking a virtual surface of columnar dendrite tips (EP-FT model). The last one, being an extension of the EP-FT model proposed in [

25], is used for the first time in a detailed study of solute inhomogeneity under hyper-gravity conditions. For these comparisons, a simplified 2D model of the representative rotating plane is developed based on a thorough analysis of all forces acting on a cast in the centrifuge and their projections onto the plane. Having shown that the EP-FT model is the most reasonable choice for a reliable simulation of complex macro-segregation pictures in centrifugal alloy casting, it has been further used to address the interesting issue of the impact of the hyper-gravity level and the cooling direction on the development of the macro-segregation pictures, and the tendency to form freckles in solidifying Pb-Sn alloy casting.

The paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, the mathematical and computational model in the form of transport equations, boundary and initial conditions, closure relations, geometry, and material properties, is detailed. The emphasis is placed on the description of buoyancy volumetric forces inherent in centrifugal casting, as well as specific transport models in the slurry and porous zones, and the front tracking procedure. In

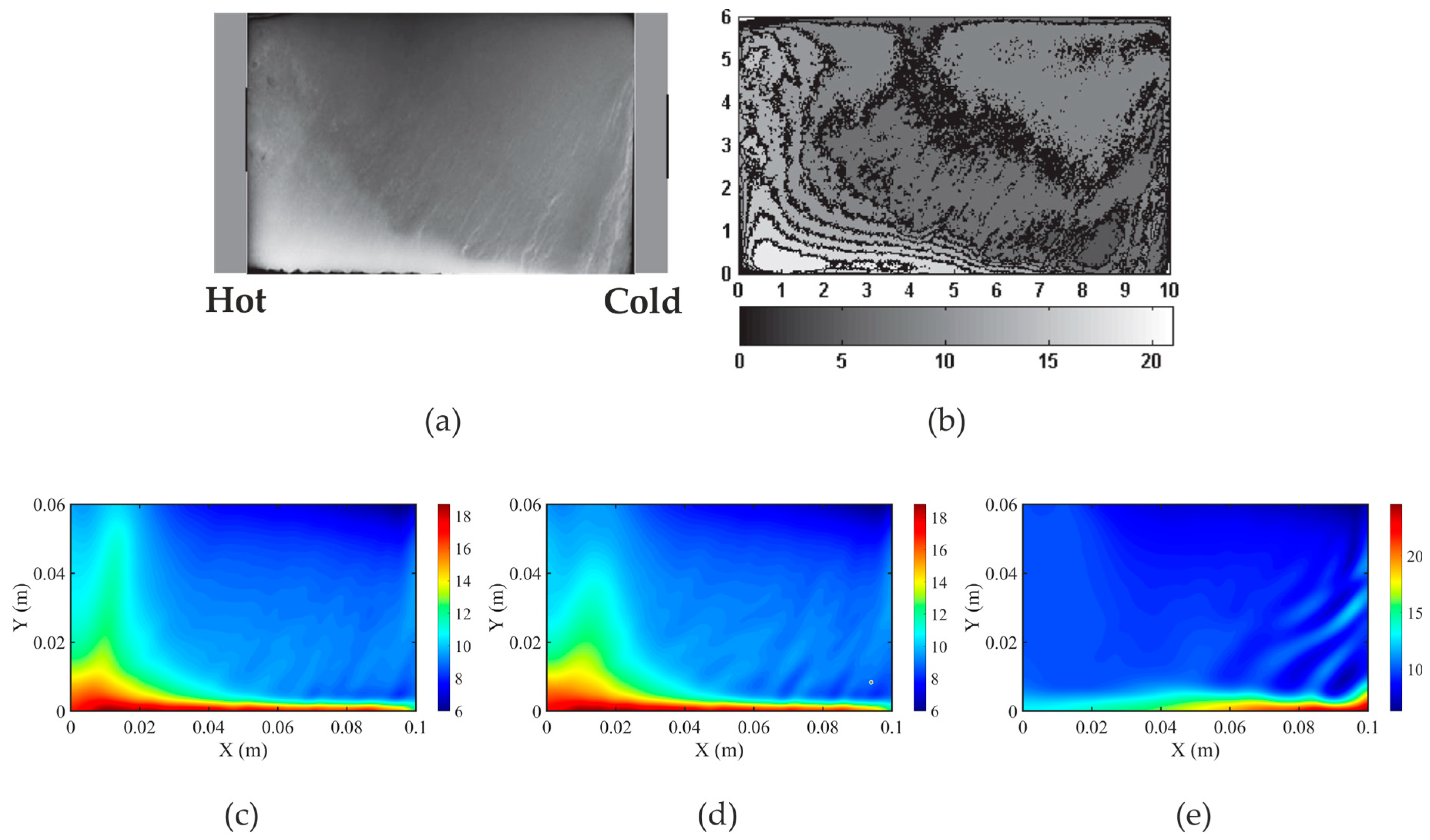

Section 3, the credibility analysis is carried out. It consists of model validation with the AFRODITE experiment, and simulations are executed for the Sn-10wt% Pb alloy solidification at purely natural convection conditions and terrestrial gravity. In the second part of

Section 3, the mesh sensitivity analysis is performed for the solidification of Pb-48wt. % Sn alloy, at an enhanced gravity level (5 g), and in the rotated frame. The parametric analysis (

Section 4) consists of several steps that highlight the various aspects of the model. In

Section 4.1, the models (EP, EP-FT, and EP-CP) are examined, and the impact of gravity level, cooling orientation, and coherency point value (EP-CP) on the development of macro-segregation and the formation of segregation channels is considered. In

Section 4.2, the EP-FT model is investigated. The role of orientation and gravity level in the macro-segregation picture is analyzed. Final conclusions are presented in

Section 5.

2. Mathematical and Computational Model

Macroscopic calculations of binary alloy centrifugal solidification are often built on the single continuum enthalpy–porosity model utilizing the classical two-phase mixture theory (e.g., [

12,

13]). During the cooling and solidification of an alloy’s cast, the two-phase zone (mushy zone) evolves, usually containing two distinguished regions of columnar and equiaxed grains. The former, having a strong directional nature, appears as a dense crystalline-like matrix filled with inter-dendritic liquid. In the equiaxed zone, grains freely grow, mutually influence, and move in the melt, and the CET phenomenon might occur. To account for different resistances to the melt flow occurring within these two diverse dendritic structures, Darcy’s porous medium model is commonly used in the columnar dendrite zone, whereas the slurry medium model is applied to the equiaxed grain zone. Therefore, it is necessary to distinguish regions of different grain structures in the computational model before applying distinct descriptions of the flow conditions. Two methods have been used to identify grain regions of varying flow conditions; they are coupled with the enthalpy–porosity model. The first one is the commonly used coherency point approach (e.g., [

22,

23,

24]), and the computational model is further referred to as the EP-CP (Enthalpy Porosity–Coherency Point). The second one, further called the EP-FT (Enthalpy Porosity–Front Tracking), involves the front tracking procedure to trace the envelope of columnar dendrite tips on finite volume meshes (e.g., [

25,

26,

29,

33,

34,

35]). The macro-segregation and channeling pictures developing in the centrifugal investment casting predicted by the EP-CP and EP-FT models are compared in this research.

2.1. Macroscopic Conservation Equations

A single set of the macroscopic conservation equations of mass, momentum, energy, and the solute transport in the liquid–solid mixture appears as

V, T, and C are the velocity vector, temperature, and solute concentration, respectively. Thermo-physical properties: ρ, k, c, μ, L, and D denote density, thermal conductivity, specific heat, dynamic viscosity, latent heat of fusion, and solute mass diffusivity, respectively. Indices S and L refer to the solid and liquid phases. g and f are phase volumetric and mass fractions, respectively, and stand for the switching function, which equals 1 in the columnar dendrites zone and 0 elsewhere.

According to the mixture theory, the velocity, thermal conductivity, overall solute concentration, and solute mass diffusivity of the liquid–solid mixture are given by the following:

where C

L and C

S are the average solute concentrations, and D

L and D

S are the solute diffusivities in the liquid and solid phases, respectively.

The volumetric sources,

FV, in Equation (2) are given by

The first and second terms in the square brackets refer to thermal and solute buoyancy forces described by the commonly used Boussinesq’s natural convection model. In a stationary coordinate system, they are multiplied by the terrestrial gravity acceleration vector,

g, and constitute the gravity force,

Fg. The second and third terms in the curly brackets express the centrifugal,

Fcf, and Coriolis,

FC, forces.

2.2. Simplified 2D Geometrical Model of the Volumetric Forces

The volumetric forces acting on a liquid volume in the rotating frame are three-dimensional; the terrestrial gravity works in the vertical direction, centrifugal acceleration acts radially concerning the centrifuge axis, and the Coriolis force operates in the horizontal planes.

The gondola with the furnace and the sample, mounted at the end of the rotating arm (

Figure 1), rotates with the angular velocity, ω, around the axis Z. The rotation angle of the gondola, α, depends on the ratio of the centrifugal force and the gravity force and can be derived with the formula

the resulting (acceleration) force,

Fr, is the sum of the centrifugal,

Fcf, and gravity forces,

Fg, and is applied to the mass center of the gondola.

The rotation rate, ω, and the distance from the axis, R, are adjusted to ensure the required gravity acceleration level. Three values of gravity acceleration are considered: 1 g, 5 g, and 15 g. For the first one, treated as the reference case, the rotation speed is obviously equal to 0.

In the presented study, centrifugal casting in a simplified layout is considered. The sample is positioned in the center of the gondola. The cuboid shape of the mold is assumed. The basic orientation of the sample is presented in

Figure 1, according to the Cartesian coordinate system x’, y’, z’ (

Figure 1a), fixed with the gondola, rotating around axis Z. The length of the edge parallel to the z’ axis is much lower than other dimensions of the cavity, so the 2D geometry of the computational domain is assumed. Additionally, the interactions of the molten alloy with walls parallel to the x’-y’ plane are omitted, and the fluid velocity components in the z’ directions are set to zero.

In this paper, the relation between the direction of cooling and the resultant acceleration force is investigated, so various orientations of the sample are considered. To accomplish various heat dissipation directions, given with Q, the sample is rotated around the axis perpendicular to the x’-y’ plane and crossing the central point of the sample, marked as the rotation axis in

Figure 1b. For each case the rotation angle, β, is measured between the modified direction of the dissipated heat transfer, Q, and the resulting force,

Fr, as presented in

Figure 1b and it is considered as a multiple of a 30-degree angle. The limiting values of angles 0° and 180° correspond to the cooling from the bottom and top, respectively. The size of the considered domain is 0.1 m in the x-axis direction and 0.06 m in the y-axis direction (

Figure 1b. The new coordinate system, namely x, y, z, describes the orientation of the system relative to the acceleration force.

The first and second terms in the curly brackets in Equation (9) refer to the gravitational acceleration and the centrifugal forces, respectively, and their influence can be described with the resulting (acceleration) force, Fr.

The Coriolis force (the last term in Equation (9)) may act outside of the plane x-y, so, to account for the impact of that force in the considered 2D geometry, it is necessary to take the components of the Coriolis force cast in the x-y plane. However, for the highest enhanced gravity acceleration, 15 g, and the assumed process parameters, ω = 30 rad/s, R = 2.42 m, and assumed maximum molten alloy velocity Vmax = 0.1 m/s, the Coriolis force magnitude is comparable to the gravity force, and 15 times lower than the resulting force. So, in the simplified analysis, neglecting the Coriolis force is justified.

2.3. Identification of Zones of Different Grain Structures

Two different approaches are used to identify zones of prevailing distinct grain structures within the mushy zone. The first one is the dendrite coherency point model (DCP), which is based on continuously examining a solid fraction value in the mushy zone during developing solidification. Darcy’s flow model with the permeability concept is used when the solid fraction exceeds a critical value, generally accepted as equal to the solid fraction at the temperature at which the growing dendrites begin to impinge upon each other and form the stationary coherent dendritic network. Otherwise, in the zone where small equiaxed dendrites float in the alloy melt, the slurry model is adopted. This approach has been commonly used in meso-macroscopic computer simulations of metal alloy solidification under terrestrial gravity (e.g., [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26]) and by Daloz et al. [

27] in the numerical analysis of solute segregation in the centrifugally cast Al-Ti cylindrical sample. According to this methodology, the porous and slurry regions are identified with the switching function, Ṽ

coh, which depends on the solid fraction according to the following formula (e.g., Ilegbusi and Mat [

21]):

where g

s,coh is the volumetric fraction of the solid phase when the grains start to impinge.

The main uncertainty arising when using the DCP model concerns the reliable estimation of the packing solid fraction value at the dendrite coherency point. The literature review shows that because of the lack of experimental data for various metal alloys, some authors misuse the DCP value determined experimentally by Arnberg et al. [

36] for only aluminum-based alloys, while others set its value arbitrarily. This parameter is also known as the coherency solid fraction (e.g., Ilegbusi and Mat [

21]), and is referred to as g

s,coh in this paper. The DCP solid fraction, g

s,coh, strongly depends on the alloy composition (e.g., [

36,

37]), and its assumed value has a significant impact on numerically predicted solute concentration fields and macro-segregation pictures (e.g., [

23,

24]). Moreover, Banaszek and Seredyński [

25] have shown that the use of the isoline of constant solid packing fraction for distinguishing different grain structures is inaccurate, particularly at early stages of solidification when the formation of channel segregates develops much earlier than the CET appears, i.e., for smaller values of the solid fraction.

An alternative method for identifying zones of different dendritic structures is based on direct tracking of a virtual surface, being a locus of the columnar dendrite tips and moving on a fixed control-volume mesh during proceeding solidification according to the assumed crystal growth kinetics. This approach, originated by Browne and Hunt [

33] for the case of purely diffusive alloy solidification, has been further extended to modeling columnar and equiaxed binary alloy solidification driven by natural thermal convection [

34] and thermo-solutal convection [

35] on 2D structural control-volume meshes. Recently, Seredyński and Banaszek [

26] have generalized the front tracking procedure to 2D unstructured control-volume meshes and used it to analyze the role of different permeability laws and various microstructure characteristic lengths on the numerically predicted solute macro-segregation developing during solidification of Pb-Sn alloys in the terrestrial gravity conditions. Battaglioli et al. [

28] have applied the front tracking method in their 2D computer simulation of centrifugal directional solidification of Ti-Al alloy to study the role of hyper-gravity on the evolution of fluid flow, temperature, and grain structures. Their model is, however, restricted to a structural control-volume mesh and does not involve the solute transport, so the solute macro-segregation is not addressed.

In the presented study, for the first time to the authors’ best knowledge, the front tracking approach, coupled with the macroscopic description of heat, momentum, and solute mass transport phenomena driving the binary alloy solidification, is used to address the issue of the role of hyper-gravity acceleration in the development of chemical inhomogeneity in a solidifying cast.

The main novelty of the EP-FT simulation model lies in tracking the envelope of columnar dendrite tips on a fixed control-volume unstructured mesh at the end of each subsequent calculation cycle of the transport processes conducted using the enthalpy–porosity (EP) model. This hypothetical interface of columnar dendrite tips is represented by a series of linear segments connected with massless markers, as shown in

Figure 2a. An i-th marker’s initial location,

, is known from the previous time step; the marker moves in the normal direction to the front towards the bulk liquid, according to the determined local undercooling, ΔT, and the assumed columnar dendrite growth law. The marker’s new position is determined as

and a new shape of the front is obtained by the interpolation between new locations of the markers (red line segments in

Figure 2a). In the presented calculations, the columnar dendrite tip velocity, V

tip, is assumed to be independent of the acceleration level and is determined using the Kurz–Giovanola–Trivedi law [

38] and the least-square approximation to obtain

for the further analyzed Pb-48wt.% Sn alloy.

The front-position-based switching function, Ṽ

ft, is related to the position of the columnar front and is defined at a consecutive time step as the ratio of the part of the control volume marked with green color to the whole corresponding control volume (

Figure 2b). Control volumes crossed by the front have properties of both the slurry and porous media. The source terms in the momentum balance equation, Equation (2), are activated in this region with the appropriate weights depending on the Ṽ

ft function. Based on the actual position of the columnar front, the Ṽ

ft is equal to zero in the bulk liquid and the slurry zone and to one in the fully porous medium. It smoothly changes between these limit values along the control volume crossed by the columnar front. The function Ṽ

ft is also used to calculate actual values of the phase velocities as follows:

where for parameter Ṽ, the coherency switching function, Ṽ

coh, or the front-position-based switching function, Ṽ

ft, can be substituted.

More detailed information on procedures related to tracking of the front and its relation with emerging structures can be found in our previous papers, e.g., Seredynski and Banaszek [

26].

The initial position of the front is coincident with the cooled walls. In the case presented in

Figure 1, only one wall is cooled, located at x = 0, where x and y coordinates are related to the system rotated by angle β. The beginning of the front is positioned at the point (x, y) = {0.0, 0.06} and the end at the point (x, y) = {0.0, 0.0}.

2.4. Transport Properties and Closure Relationships

The system of macroscopic transport equations (Equations (1)–(4)) is based on the mixture theory approach, where a two-phase medium is treated as a pseudo-fluid with smoothly varying properties, and the local thermal, compositional, and mechanical equilibrium occurs on the scale of a single grain. Equations (5)–(8) gives the liquid–solid mixture’s properties as weighted averages of the phase-averaged properties. In the analyzed case, the lever-rule model of micro-segregation is used in calculations. The local thermodynamic equilibrium is assumed at the phase interface, so the following relation between solute concentrations holds: kpCL* = CS*, where kp is the equilibrium partition coefficient; CL* and CS* are the actual solute concentrations at the liquid and solid side of the interface, respectively. According to the assumed lever-rule micro-segregation model, both surface concentrations are equal to volume-averaged ones, namely CS = CS* and CL = CL*. The parameter kp is lower than 1, so the solubility of the solute is lower in the solid phase than in the liquid. It results in local chemical segregation of elements. The solute is rejected into the liquid phase (micro-segregation) and then transported with inter-dendritic liquid towards the bulk melt (macro-segregation). As a result, solute depletion is observed in the porous zone, while the liquid is enriched in the slurry region.

The hydrodynamic interaction between the molten alloy and the columnar dendrite porous structure is described with the Kozeny–Carman relation

under the assumption that the micro-scale parameter, namely the secondary dendrite arm spacing, λ

2, is constant, and the porous structure is isotropic.

In Equation (2), the solid phase viscosity is defined differently in the slurry and porous zones. In the former, it is determined based on the Ishii and Zuber [

39] rheological model, where the slurry dynamic viscosity equals the following:

, and is also a weighted average of solid and liquid viscosities

. In the porous zone, the solid phase velocity equals zero, so the third term on the right-hand side of Equation (2) disappears. In the control volumes close to the interface between the porous and slurry regions, demarcated by the Front (EP-FT model), the switching function, Ṽ, is used to switch between viscosity models smoothly.

On the other hand, in the EP-CP model, the coherency solid fraction isoline is captured, and the coherency switching function, ṼCP, is used to commute between viscosity models smoothly.

The local equilibrium process is assumed, where the hydrodynamic forces between phases are balanced, the locally averaged temperature is uniform at the scale of a single grain, and the steady-state solute transport across the phase boundary is assumed. The equal densities of solid and liquid phases are assumed, so alloy shrinkage-induced solidification is neglected. The cast is assumed to be filled with alloy, molten or solidified, so no free surface is present and the impact of the presence of the free surface on the process is neglected.

Material properties and boundary conditions used in the simulations are gathered in

Table 1.

2.5. Computer Simulation and Solution Procedures

The EP-CP and the EP-FT computer simulation models for the binary alloy centrifugal casting have been developed and implemented as in-house codes. The mixture mass, momentum, energy, and solute conservation equations; Equations (1)–(4) are supplemented with the closure relations, Equations (5)–(11) have been discretized on a non-orthogonal triangular control-volume mesh, and the implicit Euler scheme has been used for marching in time. The diameter of a single control volume of the nominal mesh is 1 mm, and the corresponding number of control volumes is 12,358. Since the computational mesh is non-orthogonal, the skew diffusion terms are taken into account, where gradients of the field quantities at the control volume’s faces are determined with the cell-based approximation scheme [

42]. The collocated mesh concept, where all parameters are stored in a control-volume centroid, has been adopted along with the Rhie and Chow scheme [

43] for local velocities at the cell faces, applied to avoid numerically generated spurious wavy modes of the pressure field. The first order upwind scheme [

44] has been used for the field variables on the control volume’s faces, and the fractional step computational algorithm [

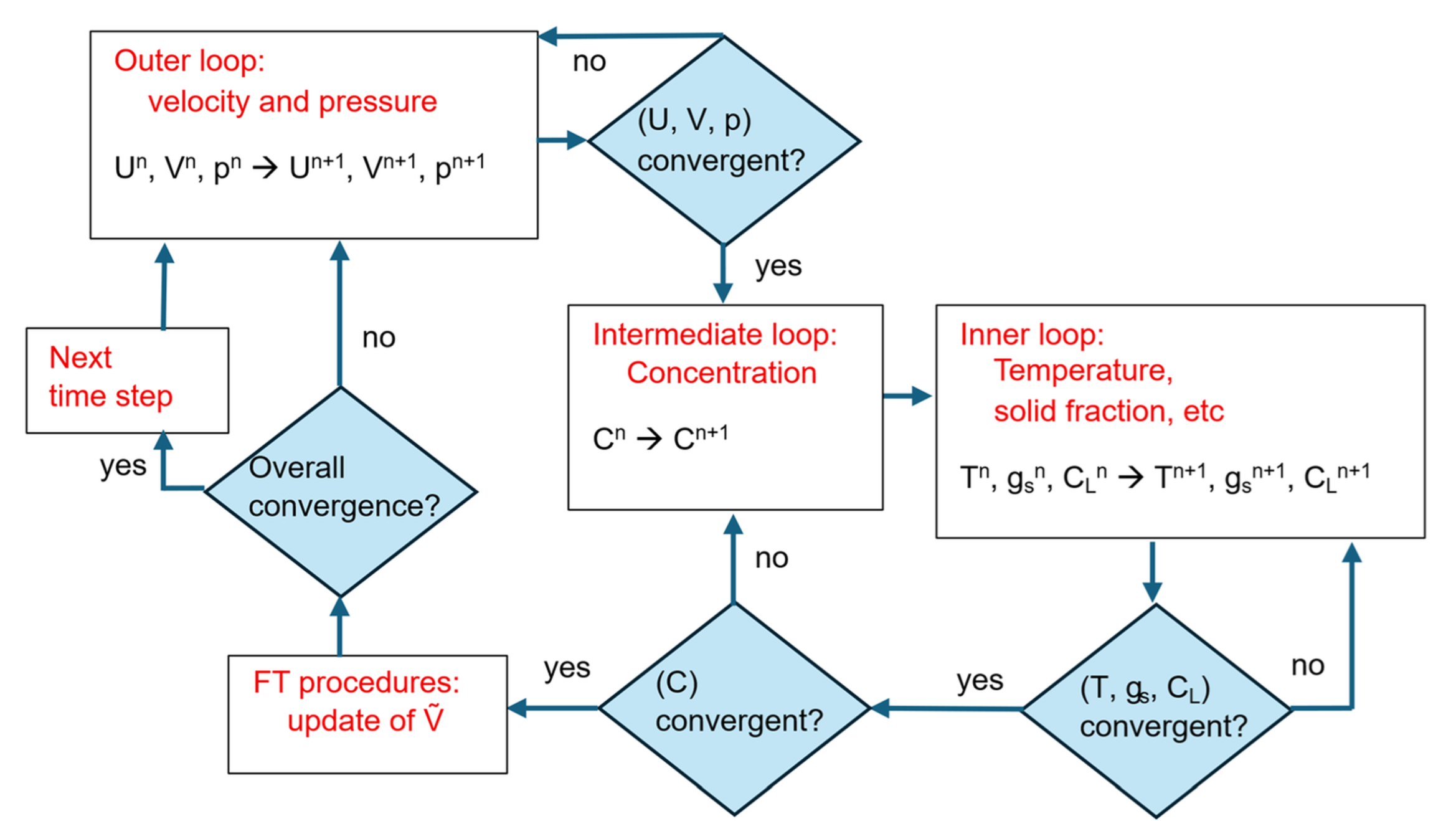

45] has been applied to couple the pressure and velocity fields. In the EP-CP calculations, different grain structures and the associated distinct models of the melt flow resistance within the mushy zone are identified by the DCP model (see

Section 2.4). On the other hand, in the EP-FT simulation model at each consecutive time step, after the iterative solving of the conservation equations (Equations (1)–(4)), the front tracking procedure is used. Zones of the columnar and equiaxed grains are recognized based on the most current temperature and concentration fields. Next, the switching function is calculated for each control volume, and the solution procedure is continued at the next step for the updated structure of the mushy zone. At each time step, the three nested iteration loops are executed. The schematic of the simulation procedures organization is presented in

Figure 3.

5. Final Conclusions

The presented research is the authors’ contribution to the development of advanced meso-macroscopic computer simulations for more accurate predictions of the solute macro-segregation and channeling phenomena under hyper-gravity, where the enhanced mass and heat transfer processes are more complex and challenging than under terrestrial gravity. Macro-segregation is a dynamic process that begins early in the solidification process and progresses over time. The primary goal of computationally efficient meso-macroscopic simulations, based on a single-domain enthalpy–porosity model coupled with the mushy zone models, is to provide valuable data on temporal changes in temperature, solid fraction, and solute concentration within a whole cast domain.

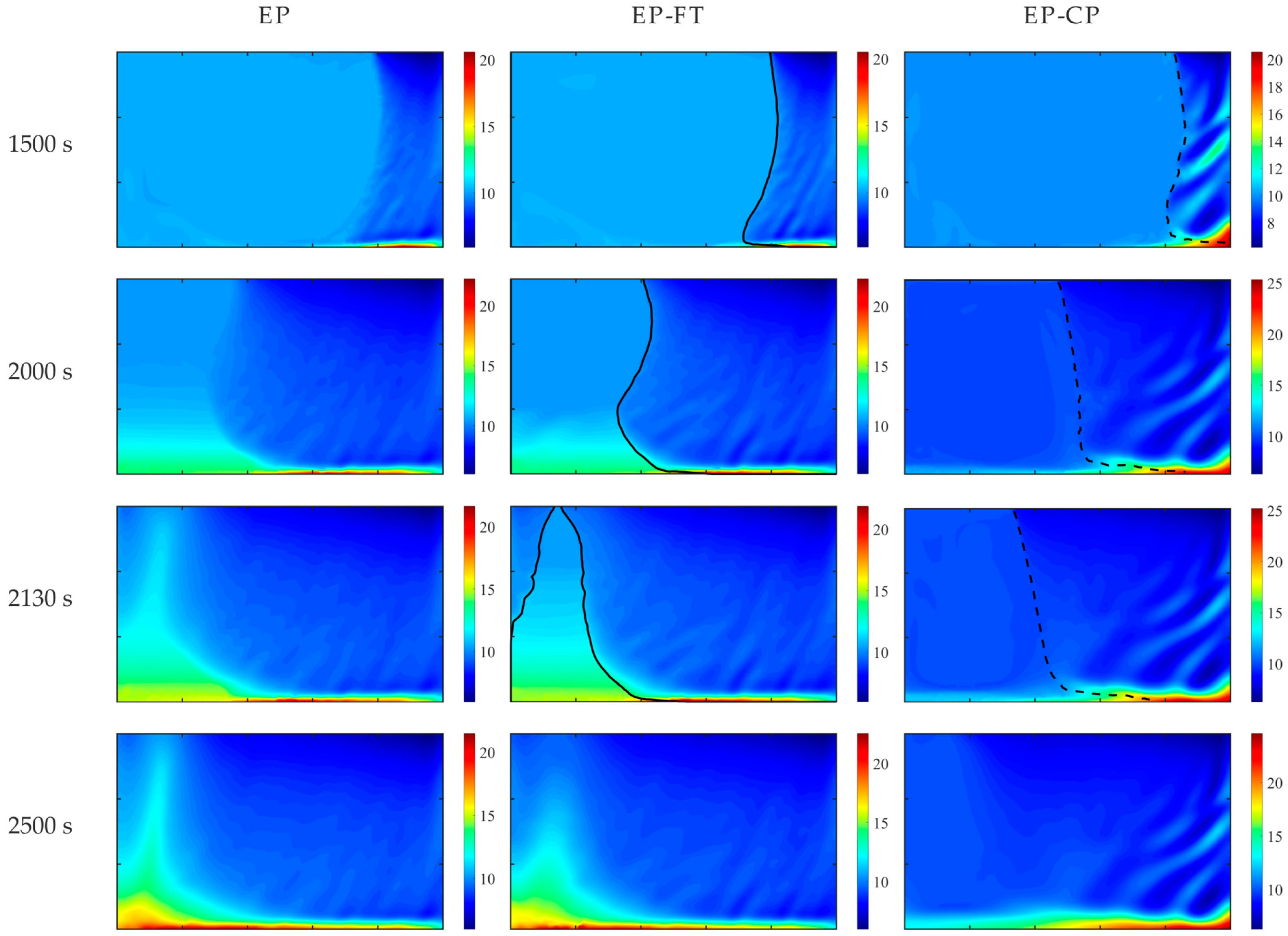

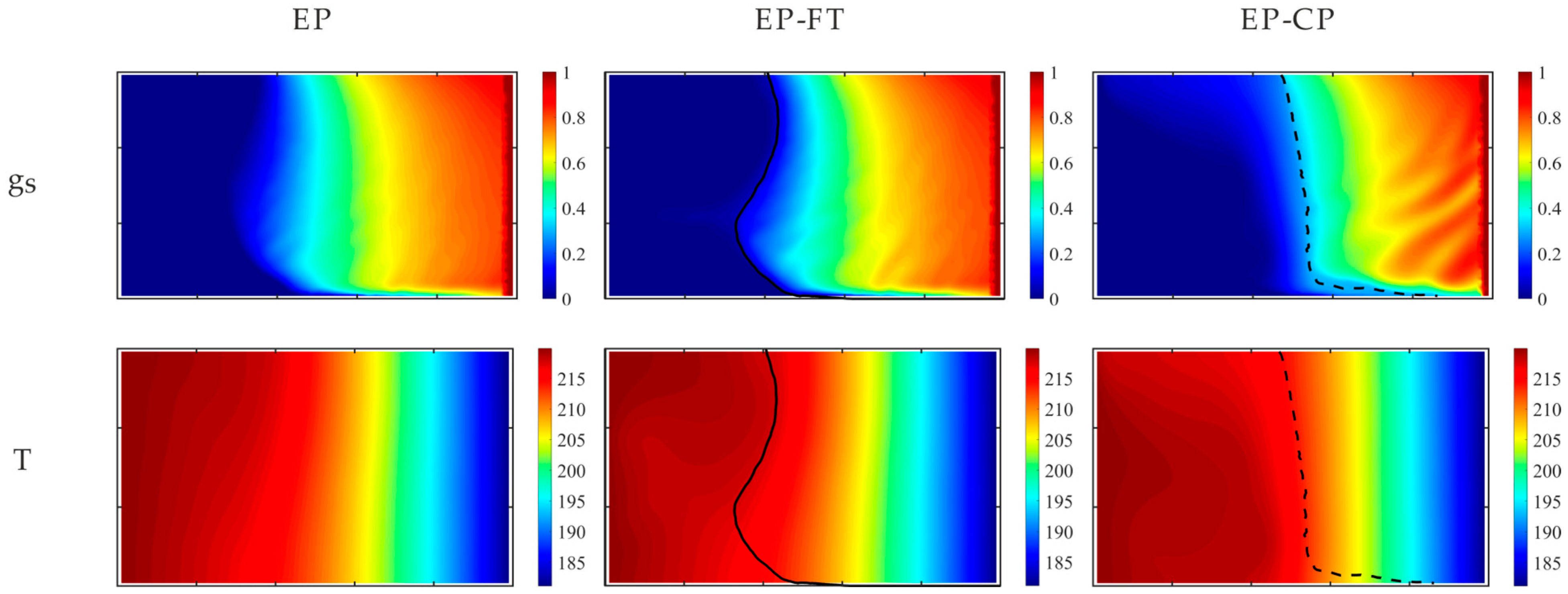

The paper addresses the issue of the role of the assumed model of mushy zone in predicting reliable pictures of solute macro-segregation in hyper-gravity. A simplified 2D model of the representative rotating plane has been developed, based on a thorough analysis of all forces acting on a cast in the centrifuge and their projections onto the plane. It has been used in a detailed comparative study of three different models of flow resistance in the mushy zone, i.e., EP, EP-CP, and EP-FT, when applied to simulate the solidification of Sn-10wt%Pb and Pb-48wt.% Sn alloys under terrestrial and hyper-gravity conditions. The study’s outcomes, in terms of predicted temporal fields of solute concentration and solid fraction, lead to the following conclusions.

The obtained pictures of macro-segregation and local channeling strongly depend on the mesoscopic model used. The differences in the models’ results increase with the rise in the hyper-gravity strength.

The columnar porous zone size predicted by the EP simulation is overestimated, particularly at early times during mold cooling, as a consequence of treating the whole mushy zone as a Darcy porous medium.

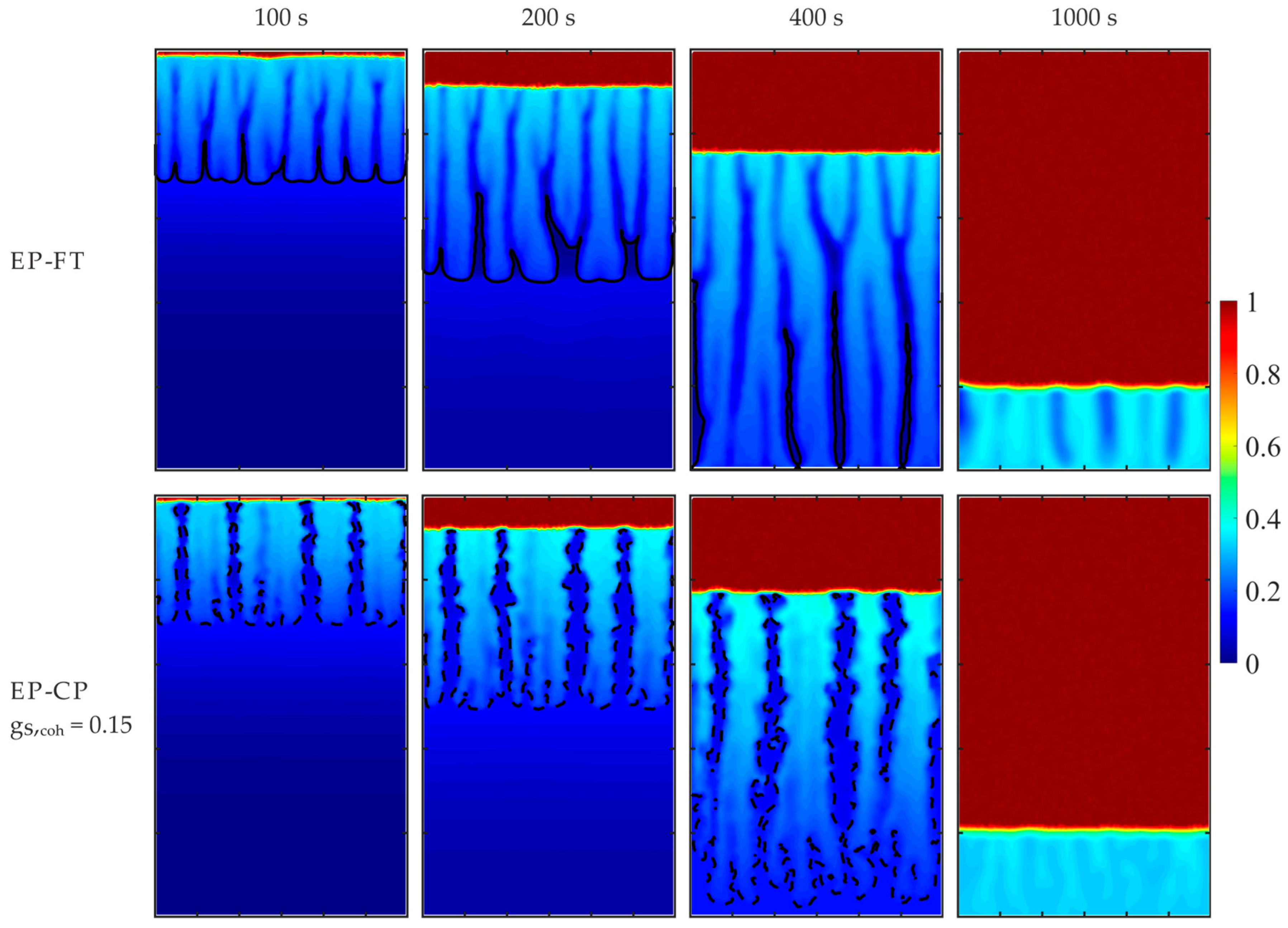

The EP-CP calculations are highly sensitive to the assumed coherence value of the solid fraction and provide completely different pictures of the solute inhomogeneity, with some complex structures of merged solid grains (see

Figure 11 and

Figure 12), which are not present in calculations with a lower coherence point. A critical problem in this popular EP-CP modeling is the lack of experimentally determined solid fraction values at the coherency point for most alloys, except for Al-based ones. Moreover, since the volumetric solid fraction varies in time, along the columnar dendrite front (see

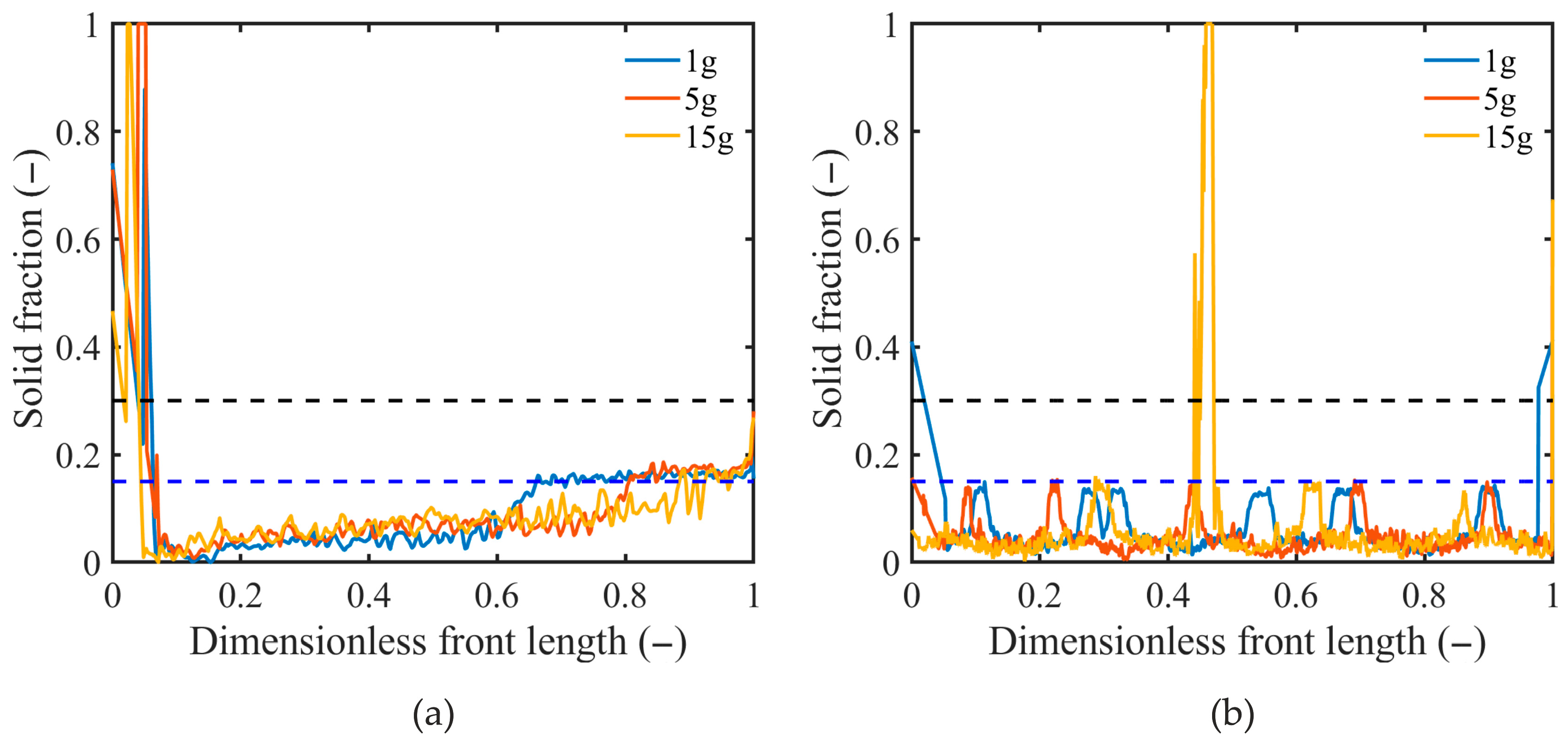

Figure 15), and with the hyper-gravity strength and direction, it is disputable to use its constant value at the coherence point for distinguishing regions of different dendritic structures.

Therefore, the proposed EP-FT model is the most reasonable choice for a reliable simulation of complex macro-segregation pictures, particularly in centrifugal alloy casting, where the melt flow, solute mass, and heat transport processes are significantly enhanced, influencing the evolving grain structure.

The EP-FT model has been positively validated by comparing its results with the AFRODITE experimental benchmark of Sn-10wt%Pb alloy solidification in terrestrial gravity. And, its accuracy has been verified through mesh sensitivity analysis in the case of Pb-48wt%Sn alloy solidification in the centrifuge with 5 g effective gravity acceleration. Then, the model has been used to frame correlations between hyper-gravity forces and the resulting chemical inhomogeneity of the centrifugal casting product. The results presented in the paper confirm the significant impact of both the strength of hyper-gravity and the angle between the cooling direction and the enhanced gravity direction on the solute concentration distribution, as well as the position and shape of the front separating different dendritic structures and the number and size of locally forming highly solute-rich channels.

Our future activity will be oriented towards developing a 3D parallelized simulation of centrifugal casting, accounting for Coriolis forces and built on unstructured adaptive meshes, for more precise modeling of the front separating different dendritic structures and simulations in more complex cast domains. Additionally, the impact of the relative density of solid grains and molten alloy, as well as the role of nominal alloy composition and the related direction of thermal and solute buoyancy forces, will be studied.