Chitosan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4/Chitosan Composites

2.2. X-Ray Diffraction Measurements

2.3. Measurements of the AC Properties of Ferrofluids

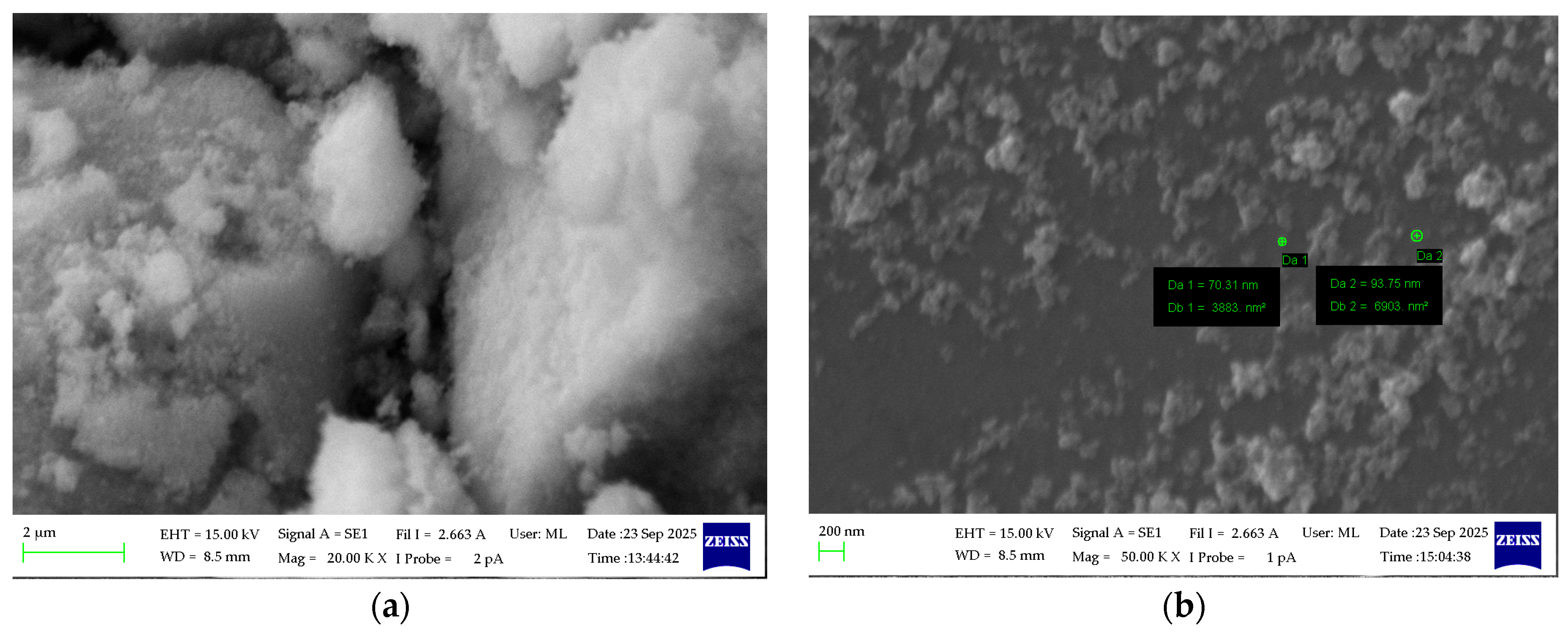

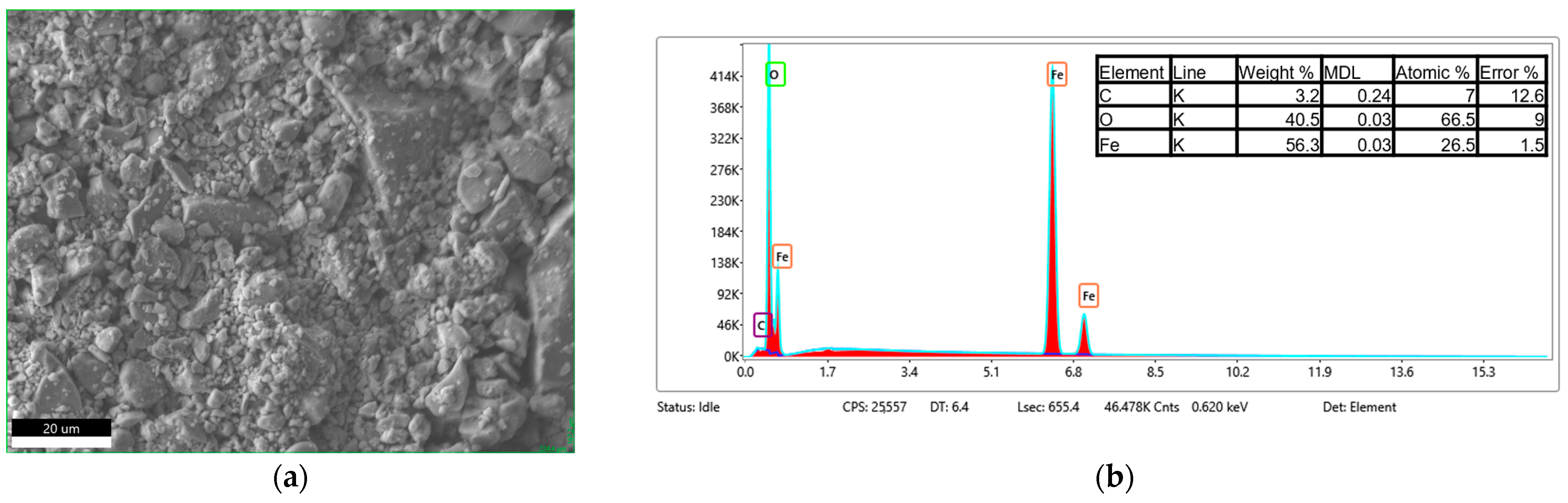

2.4. Electron Microscopy Studies and Analysis of the Chemical Composition of the Obtained Material

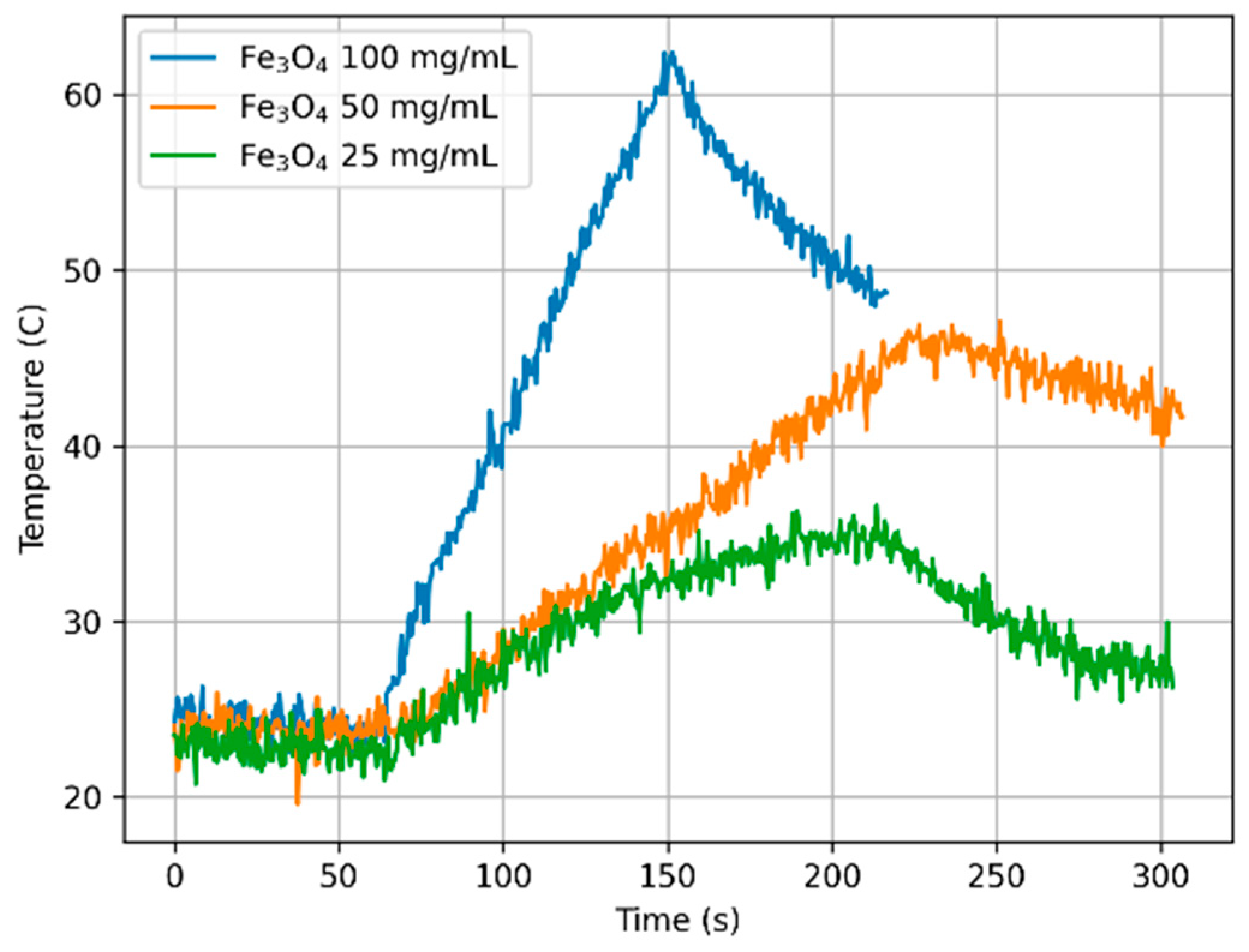

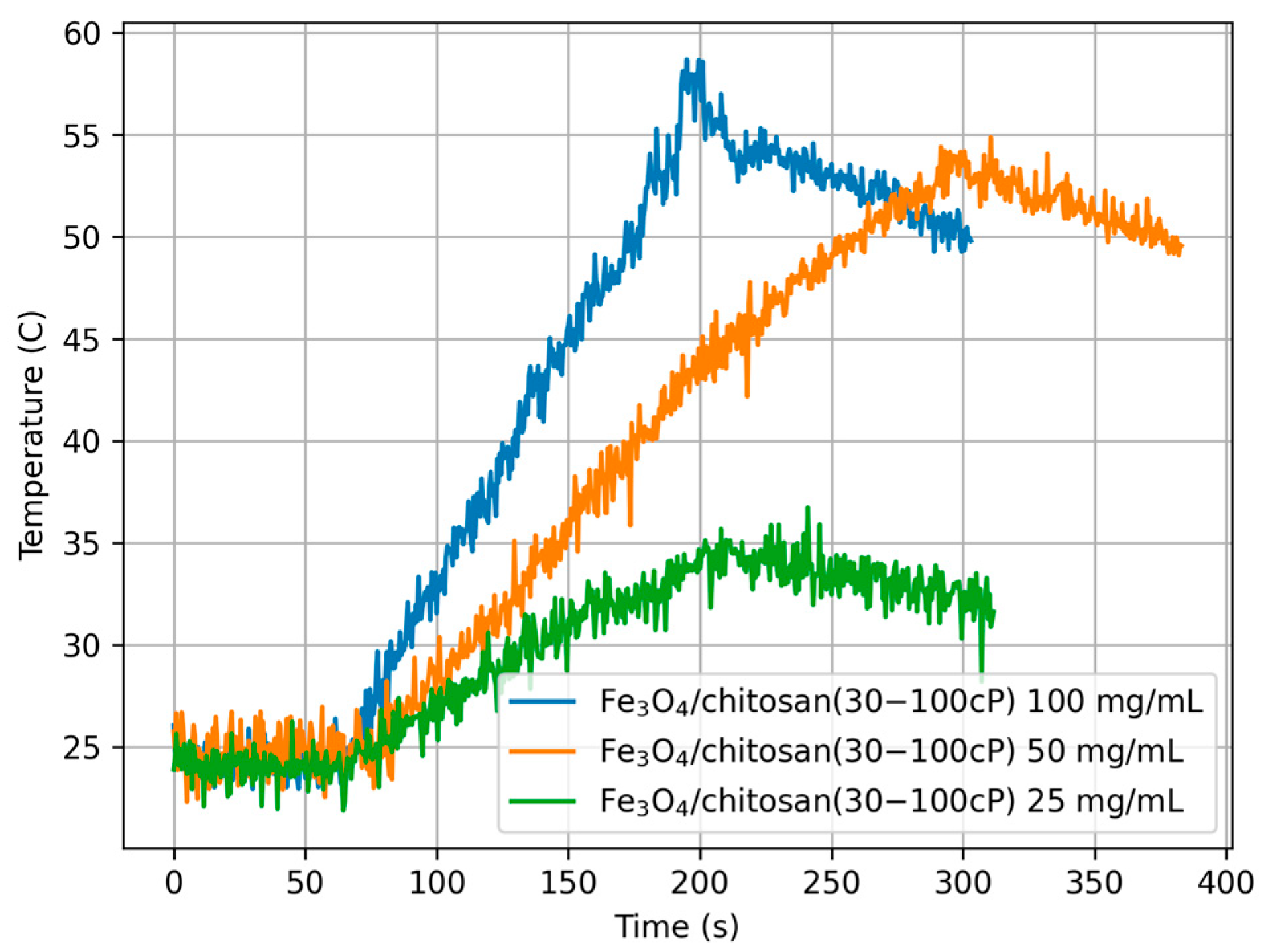

2.5. Calorimetric Experiments

2.6. Mössbauer Spectroscopy

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Analysis of Properties of Fe3O4 and Fe3O4-Chitosan Composites

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction Measurements

3.3. Measurements of Electrical and Dielectric Properties of Nanoparticles Suspended in Water Using Impedance Spectroscopy

3.4. Morphology and Composition Analysis

3.5. Magnetic Properties

3.6. Measurements Under Non-Adiabatic Conditions

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Tonthat, L.; Ogawa, T.; Yabukami, S. Dumbbell-like Au–Fe3O4 nanoparticles for magnetic hyperthermia. AIP Adv. 2024, 14, 015035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, B.; Rivera, D.; Zhang, J.Y.; Brown, C.; Young, T.; Williams, T.; Huq, S.; Mattioli, M.; Bouras, A.; Hadjpanayis, C.G. Magnetic hyperthermia therapy for high-grade glioma: A state-of-the-art review. Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoială, A.; Ludmila, M.; Cornelia-Ioana, I.; Denisa, F.; Cristina, C.; Natalia, P.; Sabina, G.; Mateusz, M.; Joanna, K.; Adrian-Vasile, S.; et al. Aminoacid functionalised magnetite nanoparticles Fe3O4@AA (AA = Ser, Cys, Pro, Trp) as biocompatible magnetite nanoparticles with potential therapeutic applications. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, S.; Yu, X.; Qian, Y.; Chen, W.; Shen, J. Multifunctional magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: An advanced platform for cancer theranostics. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6278–6309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.D.; Tran, H.-V.; Xu, S.; Lee, T.R. Fe3O4 nanoparticles: Structures, synthesis, magnetic properties, surface functionalization, and emerging applications. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Yu, M.; Zhao, S.; Tian, Y.; Bian, X. Magnetoviscous property and hyperthermia effect of amorphous nanoparticle aqueous ferrofluids. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekharan, P.; Tay, Z.W.; Hensley, D.; Zhou, X.Y.; Fung, B.K.; Colson, C.; Lu, Y.; Fellows, B.D.; Huynh, Q.; Saayujya, C.; et al. Using magnetic particle imaging systems to localize and guide magnetic hyperthermia treatment: Tracers, hardware, and future medical applications. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2965–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, C.A.M.; De Araújo, J.C.R.; Xavier, J.; Anders, R.L.; de Araújo, J.M.; da Silva, R.B.; Soares, J.M.; Brito, E.L.; Streck, L.; Fonseca, J.L.C.; et al. Magnetic nanoparticles hyperthermia in a non-adiabatic and radiating process. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elbeltagi, S.; Saeedi, A.M.; Ali, M.A.; El-Dek, S.I. Magnetic fluid hyperthermia controlled by frequency counter and colorimetric program systems based on magnetic nanoparticles. Appl. Phys. A 2023, 129, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrick, M.A.; McRae, D.A. The effect of hyperthermia-induced tissue conductivity changes on electrical impedance temperature mapping. Phys. Med. Biol. 1994, 39, 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoň, Š.; Kúdelčík, J.; Gutten, M. Dielectric Spectroscopy of Two Concentrations of Magnetic Nanoparticles in Oil-Based Ferrofluid. Act. Phys. Pol. A 2020, 137, 961–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Liu, H.; Tong, S.; Wang, J.; Han, T.; Liu, C.; Gao, C.; Han, Y. Application of impedance spectroscopy in exploring electrical properties of dielectric materials under high pressure. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2022, 34, 434001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malaescu, I.; Bunoiu, M.O.; Teusdea, A.; Marin, C.N. Investigations on the electrical conductivity and complex dielectric permittivity of a ferrofluid subjected to the action of a polarizing magnetic field. Mater. Res. Bull. 2023, 164, 112281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radoń, A.; Łukowiec, D.; Kremzer, M.; Mikuła, J.; Włodarczyk, P. Electrical conduction mechanism and dielectric properties of spherical shaped Fe3O4 nanoparticles synthesized by co-precipitation method. Materials 2018, 11, 735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalioto, F.; Barbero, G.; Campos, A.F.; Neto, A.F. Free ions in kerosene-based ferrofluid detected by impedance spectroscopy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 2819–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, C.K.D.K. Study of electrical properties of iron (III) oside (Fe3O4) nanopowder by impedance spectroscopy. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2020, 11, 127–133. [Google Scholar]

- Qayoom, M.; Shah, K.A.; Pandit, A.H.; Firdous, A.; Dar, G.N. Dielectric and electrical studies on iron oxide (α-Fe2O3) nanoparticles synthesized by modified solution combustion reaction for microwave applications. J. Electroceramics 2020, 45, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.N.; Fannin, P.C.; Malaescu, I. Polarizing magnetic field effect on some electrical properties of a ferrofluid in microwave field. Magnetochemistry 2024, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, C.N.; Fannin, P.C.; Malaescu, I.; Matu, G. Macroscopic and microscopic electrical properties of a ferrofluid in a low frequency field. Phys. Lett. A 2020, 384, 126786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batalioto, F.; Parekh, K.; Barbero, G.; Figueiredo Neto, A.M. Impedance measurements on kerosene-based ferrofluids. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 136, 094701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janem, N.; Azizi, Z.S.; Tehranchi, M.M. Microwave absorption and magnetic properties of thin-film Fe3O4@ polypyrrole nanocomposites: The synthesis method effect. Synth. Met. 2021, 282, 116948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liandi, A.R.; Cahyana, A.H.; Yunarti, R.T.; Wendari, T.P. Facile synthesis of magnetic Fe3O4@ Chitosan nanocomposite as environmentally green catalyst in multicomponent Knoevenagel-Michael domino reaction. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 20266–20274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G.K.; Hall, W.H. X-Ray line broadening from filed aluminium and wolfram. Acta Met.-Lurgica 1953, 1, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildeboer, R.R.; Southern, P.; Pankhurst, Q.A. On the reliable measurement of specific absorption rates and intrinsic loss parameters in magnetic hyperthermia materials. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2014, 47, 495003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szalai, A.J.; Kaptay, G.; Barany, S. Electrokinetic potential and size distribution of magnetite nanoparticles stabilized by poly (vinyl pyrrolidone). Colloid J. 2019, 81, 773–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vereda, F.; Martín-Molina, A.; Hidalgo-Alvarez, R.; Quesada-Pérez, M. Specific ion effects on the electrokinetic properties of iron oxide nanoparticles: Experiments and simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 17069–17078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowska, A.; Markowska-Szczupak, A.; Lendzion-Bieluń, Z. TiO2-modified magnetic nanoparticles (Fe3O4) with antibacterial properties. Materials 2022, 15, 1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinayasree, S.; Nitha, T.S.; Tiwary, C.S.; Ajayan, P.M.; Joy, P.A.; Anantharaman, M.R. Magnetically tunable liquid dielectric with giant dielectric permittivity based on core–shell superparamagnetic iron oxide. Nanotechnology 2018, 29, 265707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polikarpov, M.; Cherepanov, V.; Chuev, M.; Gabbasov, R.; Mischenko, I.; Jain, N.; Jones, S.; Hawkett, B.; Panchenko, V. Mössbauer evaluation of the interparticle magnetic Interactions within the magnetic hyperthermia beads. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2014, 380, 347–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosensweig, R.E. Heating magnetic fluid with alternating magnetic field. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2020, 252, 370–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Specific Surface Area, m2/g | Pore Volume, cm3/g | Micropore Volume, cm3/g | Pore Diameter, nm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 76.3 | 0.364 | none | 19.0 |

| chitosan 30–100 cP | 3.7 | 0.023 | none | 25.0 |

| chitosan 100–300 cP | 4.5 | 0.030 | none | 26.3 |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (30–100 cP) | 72.5 | 0.286 | none | 15.8 |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (100–300 cP) | 68.9 | 0.325 | none | 18.9 |

| Dispersion Series | Minimum Value of the PDI | Maximum Value of the PDI |

|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 0.296 (pH = 2.62) | 0.586 (pH = 6.61) |

| chitosan 30–100 cP | 0.479 (pH = 8.58) | 0.719 (pH = 9.47) |

| chitosan 100–300 cP | 0.705 (pH = 9.41) | 1 (pH = 3.65, 4.84, 8.47) |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (30–100 cP) | 0.217 (pH = 2.85) | 0.491 (pH = 6.73) |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (100–300 cP) | 0.296 (pH = 8.81) | 0.474 (pH = 7.20) |

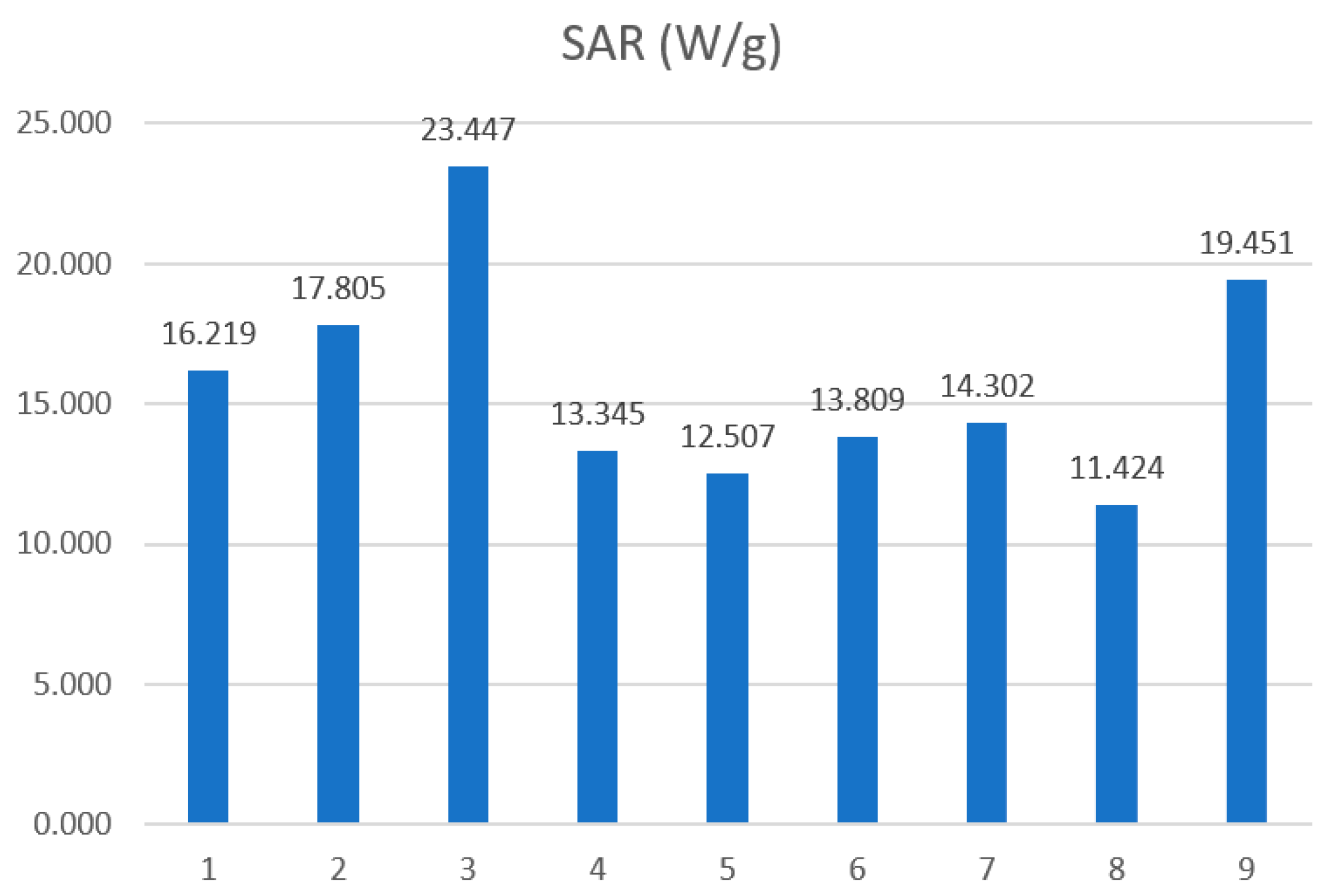

| Sample | Concentration φ mg/mL | SAR W/g | ILP nHm2kg−1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4 | 100 | 16.219 | 0.120 |

| 50 | 17.805 | 0.132 | |

| 25 | 23.447 | 0.174 | |

| 100 | 13.345 | 0.099 | |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (30–100 cP) | 50 | 12.507 | 0.093 |

| 25 | 13.809 | 0.102 | |

| 100 | 14.302 | 0.106 | |

| Fe3O4/chitosan (100–300 cP) | 50 | 11.424 | 0.085 |

| 25 | 19.451 | 0.145 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilczyńska, A.; Ruchomski, L.; Łakomski, M.; Góral-Kowalczyk, M.; Surowiec, Z.; Miaskowski, A. Chitosan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Materials 2025, 18, 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245629

Wilczyńska A, Ruchomski L, Łakomski M, Góral-Kowalczyk M, Surowiec Z, Miaskowski A. Chitosan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245629

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilczyńska, Aleksandra, Leszek Ruchomski, Mateusz Łakomski, Małgorzata Góral-Kowalczyk, Zbigniew Surowiec, and Arkadiusz Miaskowski. 2025. "Chitosan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia" Materials 18, no. 24: 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245629

APA StyleWilczyńska, A., Ruchomski, L., Łakomski, M., Góral-Kowalczyk, M., Surowiec, Z., & Miaskowski, A. (2025). Chitosan-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for Magnetic Hyperthermia. Materials, 18(24), 5629. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245629