A Comparison Between the Growth of Naturally Occurring Three-Dimensional Cracks in Scalmalloy® and Pre-Corroded 7085-T7452 and Its Implications for Additively Manufactured Limited-Life Replacement Parts

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (i)

- It has primary structural applications in both current commercial and military aircraft, see Main et al. [1].

- (ii)

- European Aviation Safety Authority (EASA) Safety Information Bulletin (SIB) 2018-04R2 [2] revealed that AA7085-T7452 airframes can experience environmentally assisted cracking (EAC) issues.

- (iii)

- As stated in Appendix X3 of the ASTM fatigue test standard ASTM E647 [3]: “Fatigue cracks of relevance to many structural applications are often small or short for a significant fraction of the structural life.”

- (iv)

- As explained in MIL-STD-1530Dc [4], which addresses the airworthiness certification of conventionally built metallic airframes, and in United States Air Force (USAF) Structures Bulletin EZ-SB-19-01 [5], which addresses AM parts, the airworthiness certification of both conventionally and additively manufactured aircraft parts requires a durability assessment which, as also stated, is best done using a linear elastic fracture mechanics (LEFM) based approach. Furthermore, as explained in the USAF F-15 study reported in [6], this requires using a valid small crack da/dN versus ∆K curve. Here ∆K = Kmax − Kmin, where Kmax and Kmin are the maximum and minimum values of the stress intensity factor (K) in a cycle.

- (i)

- Why compare naturally occurring 3D cracks in AA7085-T7452 with naturally occurring 3D cracks in BSI&WS LPBF built Scalmalloy®?

- (ii)

- Why raise the implications of this study for “limited-life” AM parts?

- (a)

- That the previous study [31] revealed that BSI&WS LPBF built Scalmalloy® is more damage tolerant than conventionally built AA7075-T6, which is used in a variety of both fixed and rotary wing military and civil aircraft;

- (b)

- That BSI&WS LPBF Scalmalloy® is particularly resistant to corrosion [33], the materials science explanation for this is given in [33]; that the durability of BSI&WS LPBF Scalmalloy® is predictable [32,33]. (Other studies that highlight Scalmalloy’s® excellent resistance to corrosion can be found in [34,35,36].);

- (c)

- That BSI&WS LPBF built Scalmalloy® has mechanical properties that are equivalent to that of conventionally manufactured AA 7075-T6 and superior to those of the conventionally manufactured AA 2024-T3 [31].

- (d)

- That the 2019 US Department of Defense (DoD) Memo [37] mandates that AM will be used to “increase logistics resiliency, and improve self-sustainment”;

- (e)

- That USAF Structures Bulletin EZ-SB-19-01 [5] subsequently stated that the most difficult challenge facing the airworthiness certification of an AM part is to establish an “accurate prediction of structural performance” specific to its durability and damage tolerance (DADT);

- (f)

- That USAF Structures Bulletin EZ-SB-19-01 [5] clearly stated that one of the primary considerations for a limited-life AM part is its durability;

- (g)

- That Muhammad et al. [38] concluded that of all the AM aluminium alloys studied Scalmalloy® had superior tensile strength, Young’s modulus, yield strength, and elongation to failure;

- (h)

- That, although not previously reported, AA7085-T7452 and LPBF Scalmalloy® have similar mechanical properties, see Table 1.

- (i)

- That NASA [39] have proposed an approach to the certification of AM parts that which is based on ‘material equivalence’.

| σy (MPa) | σult (MPa) | Strain to Failure (mm/mm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LPBF Scalmalloy®, heat treated at 325 °C for 4 h, from Muhammad et al. [38]. | 508 | 530 | 0.16 |

| AA 7085-T7452, values as given by SAE International [40] | 448–462 | 496–503 | 0.07–0.10 |

- (1)

- To compare the corrosion seen by identical AA7085-T7452 and BSI&WS LPBF Scalmalloy® when placed in the same ASTM B117-19 environmental chamber [43] and subjected to the same environmental conditions.

- (2)

- To highlight the similarity between the growth of naturally occurring 3D cracks in identical BSI&WS LPBF Scalmalloy® and AA7085-T7452 specimens when subjected to the same variable amplitude load spectrum.

- (3)

- To use this discovery to estimate the crack growth equation associated with naturally occurring 3D cracks in pre-exposed AA7085-T7452, and to then use this equation to predict their growth.

- (4)

- To use this equation to predict the growth of cracks in an anodised pre-exposed AA7085-T7452 specimen with a fastener hole which has corrosion damage at the intersection between the bore of the hole and the anodised surface.

- (a)

- (b)

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pre-Exposure to an ASTM B117-19 5 wt% at 35 °C Environment

2.2. The Fatigue Test Program on Pre-Exposed Base-Line AA 7085-T7452 Specimens

2.3. The Third AA7085-T7452 Test Program—An Anodised Specimen with a Fastener Hole

- (i)

- To highlight that, as has been seen in operational aircraft [26], corrosion can arise at fastener holes even if the surfaces of the AA7085-T7452 have been anodized.

- (ii)

- To investigate if the crack growth equation developed in the previous test program for naturally occurring 3D cracks that emanate from corrosion damage, can be used to predict the growth of cracks that initiate in an anodised AA7085-T7452 specimen with a fastener hole that has been pre-corroded in an ASTM B117-19 5 wt% salt fog at 35 °C.

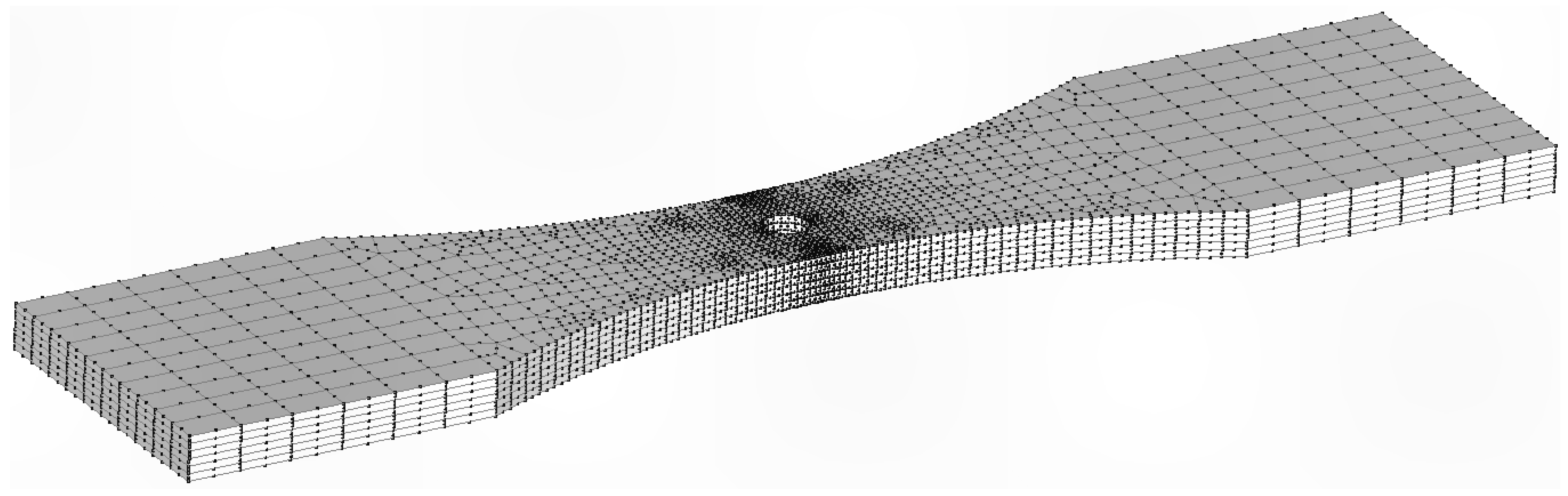

2.4. The Crack Growth Analyses

3. Results of the First Test Program—The Effect of Exposure on AA7085-T7452

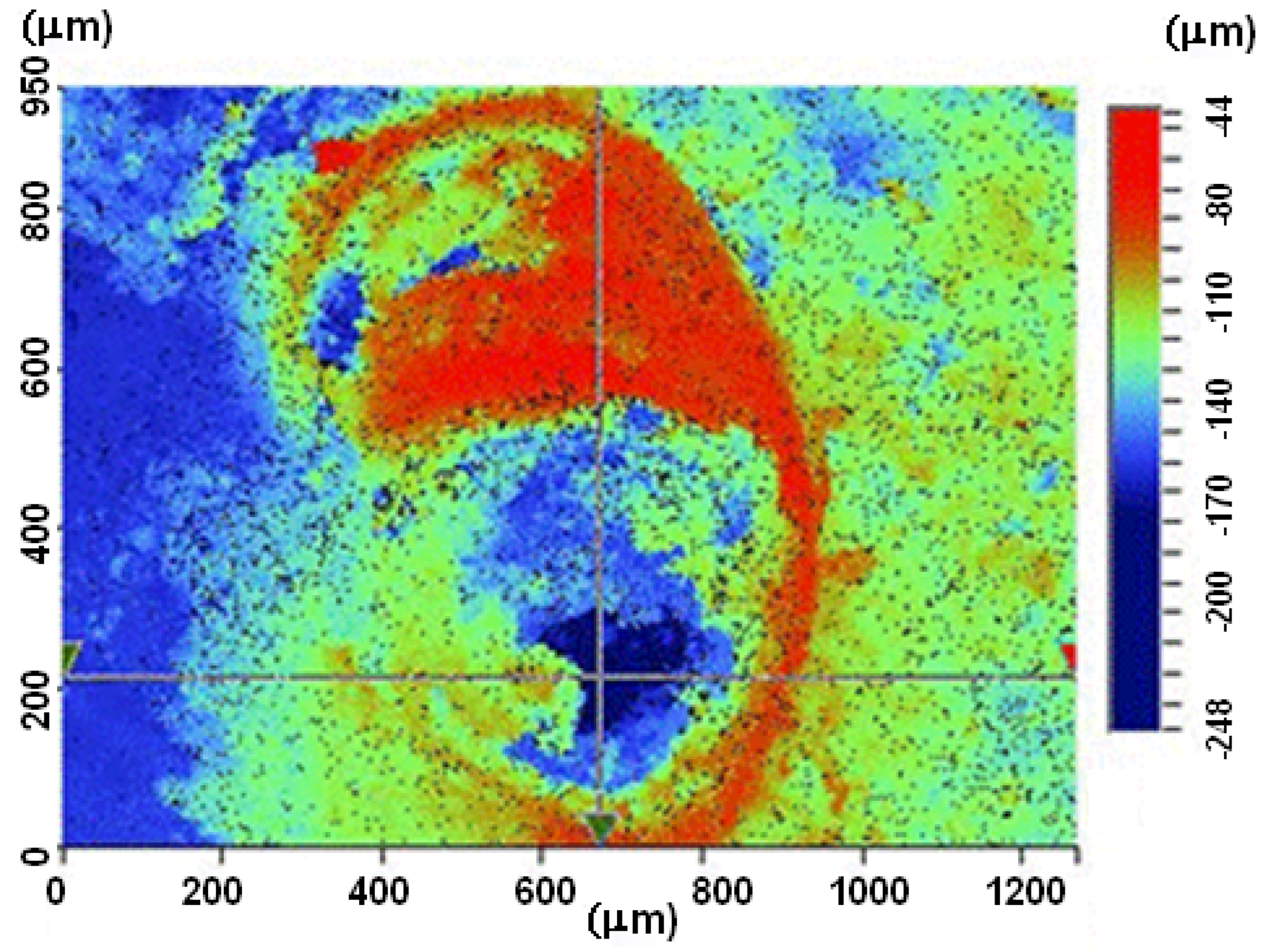

Preliminary Assessment of the Surface Topography

4. Results of the Fatigue Test Program on Pre-Exposed Base-Line AA7085-T7452 SPECIMENS

4.1. Fatigue Failure of Specimen 7085_2

4.2. Specimen 7085_3

5. Results of Predicting the Crack Growth Histories Seen in the Base-Line 7085-T7452 Test Program

5.1. Predicting the Crack Growth History Associated with Specimen 7085_2

5.2. Predicting the Crack Growth History Associated with Specimen 7085_3

6. Results of the Third AA7085-T7452 Test Program—A Specimen with a ¼ Inch (6.35 mm) Diameter Fastener Hole

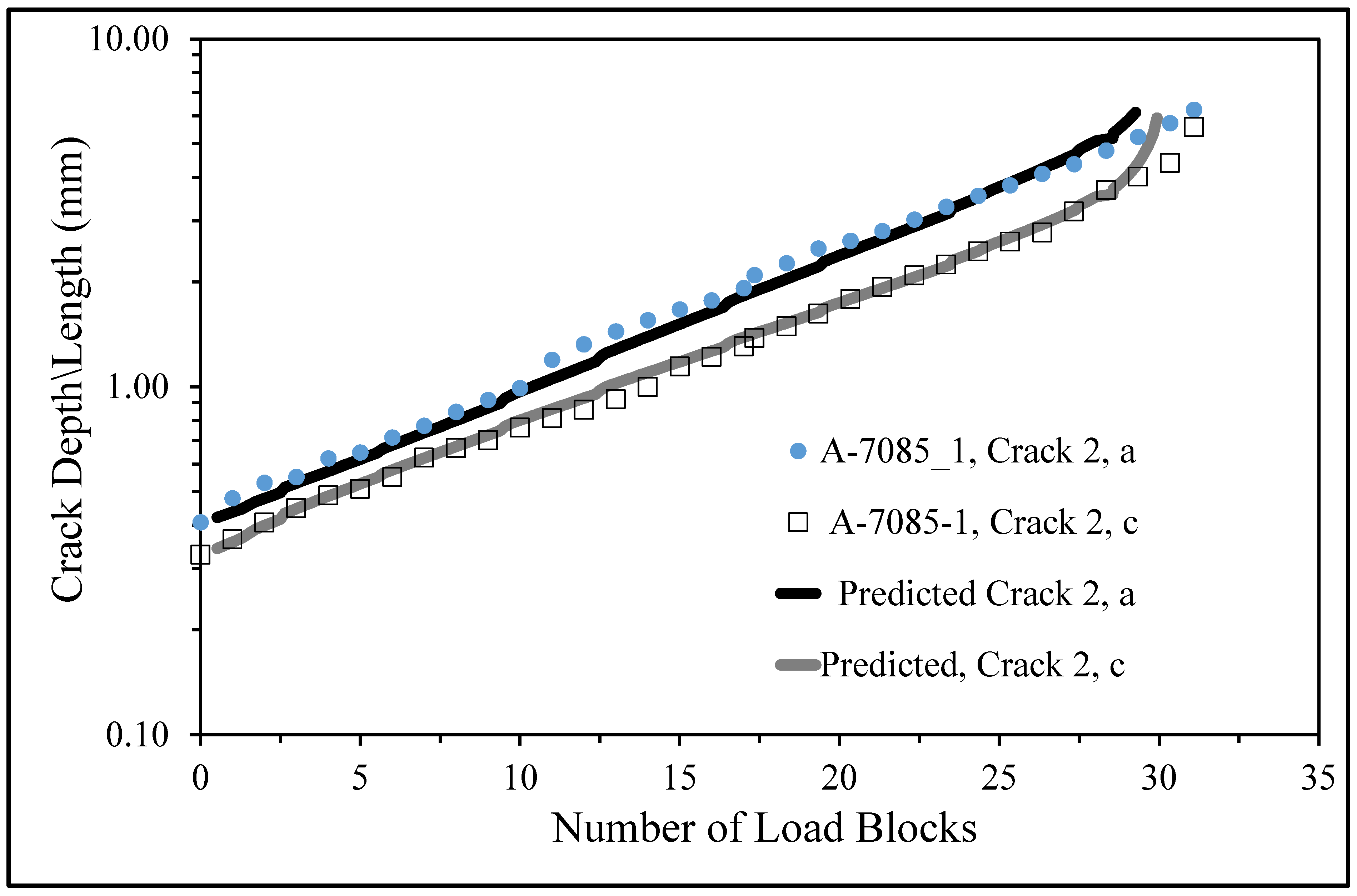

Predicting the Crack Growth History Associated with Specimen A-7085-1

7. Discussion—Implications for AM Scalmalloy

- (a)

- (b)

- the growth of naturally occurring 3D cracks in BSI&WS LPBF Scalmalloy® conforms to Equation (3);

- (c)

- Scalmalloy® has a superior damage tolerance than conventionally built AA7075-T6 [31];

- (d)

- Scalmalloy® has mechanical properties that are comparable with conventionally built AA7050-T7541 and AA7085-T7452;

- (e)

- Scalmalloy® is significantly more resistant to corrosion pitting than AA 7085-T7452;

8. Conclusions

- (i)

- similar mechanical properties;

- (ii)

- that naturally occurring 3D cracks in BSI&WS LPBF built Scalmalloy® and pre-corroded AA7085-T7452 have similar crack growth rates, and similar crack growth equations;

- (iii)

- that Scalmalloy® is significantly more resistant to corrosion pitting than AA 7085-T7452;

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| a | crack, length |

| a0 | initial crack depth |

| A | cyclic fracture toughness |

| AA | aluminium alloy |

| AM | Additively manufactured |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| da/dN | rate of fatigue crack (i.e., delamination) growth (FCG) per cycle |

| BSI&WS | Boeing Space, Intelligence and Weapon Systems |

| c0 | initial crack (surface) length |

| DADT | durability and damage tolerance |

| EAC | environmentally assisted cracking |

| EASA | European Aviation Safety Authority |

| EIDS | equivalent initial damage size |

| FCG | fatigue crack growth |

| stress-intensity factor | |

| maximum value of the applied stress-intensity factor in the fatigue cycle | |

| minimum value of the applied stress-intensity factor in the fatigue cycle | |

| LEFM | linear-elastic fracture-mechanics |

| LPB | laser powder bed fusion |

| N | number of fatigue cycles |

| NASA | North American Space Administration |

| Pmax | maximum load applied during the fatigue test |

| Pmin | minimum load applied during the fatigue test |

| load ratio (=Pmin/Pmax) | |

| RAAF | Royal Australian Air Force |

| SAE | Society of Automotive Engineers |

| SEM | scanning electron microscope |

| US | United States |

| USAF | United States Air Force |

| US DoD | United States Department of Defense |

| σy,σult | Yield stress and ultimate strength |

| 3D | three dimensional |

References

- Main, B.; Jones, M.; Dixon, B.; Barter, S. On small fatigue crack growth rates in AA7085-T7452. Int. J. Fatigue 2022, 156, 106704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASA. Environmentally Assisted Cracking in Certain Aluminum Alloys, European Aviation Safety Information Bulletin 2018-04R2, 4th March 2018. Available online: https://ad.easa.europa.eu/ad/2018-04R2 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- ASTM E647-23b; Measurement of Fatigue Crack Growth Rates. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- MIL-STD-1530D, Department Of Defense Standard Practice Aircraft Structural Integrity Program (ASIP). 13 October 2016. Available online: http://everyspec.com/MIL-STD/MIL-STD.../download.php?spec=MIL-STD-1530D (accessed on 2 July 2022).

- USAF Structures Bulletin EZ-SB-19-01, Durability and Damage Tolerance Certification for Additive Manufacturing of Aircraft Structural Metallic Parts, Wright Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA. 10 June 2019. Available online: https://daytonaero.com/usaf-structures-bulletins-library/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Lincoln, J.W.; Melliere, R.A. Economic Life Determination for a Military Aircraft. AIAA J. Aircr. 1999, 36, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holroyd, N.J.H.; Burnett, T.L.; Lewandowski, J.J.; Scamans, G.M. Environment-Induced Cracking of High-Strength Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Aluminum Alloys: Past, Present, and Future. Corrosion 2023, 79, 48–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, X.; Gao, L. Environmental Failure Behavior Analysis of 7085 High Strength Aluminum Alloy under High Temperature and High Humidity. Metals 2022, 12, 968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuang, D.; Tan, L.; Chen, K.; Chen, S.; Xie, P.; Jiao, H. Comparison of strength, stress corrosion cracking and microstructure of new generation 7000 series aluminum alloys. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 37, 616–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzenböck, E.; Ollivier, E.; Garner, A.; Cassell, A.; Hack, T.; Barrett, Z.; Engel, C.; Burnett, T.L.; Holroyd, N.J.H.; Robson, J.D.; et al. Environmental cracking performance of new generation thick plate 7000-T7x series alloys in humid air. Corros. Sci. 2020, 171, 108701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, T.M. An overview of high-performance aircraft structural Al alloy-AA7085. Acta Metall. Sin 2015, 28, 909–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, B.; Marino, G.; Schindelholz, E.; Dorman, S.G.; Locke, J.S. Measurement of atmospheric corrosion fatigue crack growth rates on AA7085-T7451. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 167, 107368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Su, Y.; Chen, Q.; Sun, J.; Huang, B.; Peng, F. Corrosion behavior and Mechanical Performance of 7085 Aluminum Alloy in a Humid and Hot Marine Atmosphere. Materials 2023, 15, 7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, L.; Xiang, L.; Tao, J.; Liu, J.; Chen, Q.; Zhong, Y. Effects of Actual Marine Atmospheric Pre-Corrosion and Pre-Fatigue on the Fatigue Property of 7085 Aluminum Alloy. Metals 2022, 12, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burns, J.T.; Boselli, J. Effect of plate thickness on the environmental fatigue crack growth behaviour of AA7085-T7451. Int. J. Fatigue 2016, 83, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboura, Y.; Garner, A.J.; Euseden, R.; Barrett, Z.; Engel, C.; Holroyd, N.J.H.; Prangnell, P.B.; Burnett, T.L. Understanding the environmentally assisted cracking (EAC) initiation and propagation of new generation 7xxx alloys using slow strain rate testing. Corros. Sci. 2022, 199, 110161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, T.L.; Euesden, R.; Aboura, Y.; Yao, Y.; Curd, M.E.; Grant, C.; Garner, A.; Holroyd, N.J.H.; Barrett, Z.; Engel, C.E.; et al. Mechanisms of Environmentally Induced Crack Initiation in Humid Air for New-Generation Al-Zn-Mg-Cu Alloys. Corrosion 2023, 79, 831–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAdam, G.; Wythe, A.; Loader, C. DSTG Intergranular Corrosion of 7000 series aluminium alloys. In Proceedings of the Joint AFRL–FAA Technical Interchange Meeting (TIM) on Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC) of High-Strength 7XXX Series Aluminum Alloys, Hope Hotel and Richard C. Holbrooke Conference Center at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH, USA, 5–6 November 2024; pp. 78–95. [Google Scholar]

- Euesden, R.T.; Curd, M.E.; Yao, Y.; Grant, C.; Holroyd, N.J.H.; Prangnell, P.B.; Burnett, T.L. Direct comparison of the environmentally induced cracking resistance of 2nd and 3rd generation alloys, AA7050-T7651 and AA7085-T7651’. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proceedings of the Joint AFRL–FAA Technical Interchange Meeting (TIM) on Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC) of High-Strength 7XXX Series Aluminum Alloys, Hope Hotel and Richard C. Holbrooke Conference Center at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH, USA, 5–6 November 2024; Air Force Research Laboratory: Riverside, OH, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/AFRL_FAA_TIM_Presentations.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Waite, S.; Passard, L. EAC Certification & Continued Airworthiness. In Proceedings of the Joint AFRL–FAA Technical Interchange Meeting (TIM) on Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC) of High-Strength 7XXX Series Aluminum Alloys, Hope Hotel and Richard C. Holbrooke Conference Center at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH, USA, 5–6 November 2024; pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Z. AFRL-FAA Technical Interchange Meeting on Environmentally Assisted Cracking/Stress Corrosion Cracking of High-Strength 7000 Series Aluminium Alloys-Airbus Briefing. In Proceedings of the Joint AFRL–FAA Technical Interchange Meeting (TIM) on Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC) of High-Strength 7XXX Series Aluminum Alloys, Hope Hotel and Richard C. Holbrooke Conference Center at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH, USA, 5–6 November 2024; pp. 143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Yates, J.B. Lockheed Martin Experiences and Efforts–EAC/SCC of 7000 Series Alloys. In Proceedings of the Joint AFRL–FAA Technical Interchange Meeting (TIM) on Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC) of High-Strength 7XXX Series Aluminum Alloys, Hope Hotel and Richard C. Holbrooke Conference Center at Wright Patterson Air Force Base, Dayton, OH, USA, 5–6 November 2024; pp. 118–135. [Google Scholar]

- En Nami, N.; Blal, A.A.; El Fallah, J.; Clet, G.; Hadjiivanov, K.; Maugé, F.; Aboulayt, A. Mesoporous Anatase–Brookite TiO2: Surface Acidity and Performance in Isopropanol Catalytic Dehydration. Catal. Lett. 2025, 155, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DODIG-2021-133 (U) Audit of Navy and Marine Corps Actions to Address Corrosion on F/A-18C-G Aircraft, Inspector General, Department of Defense. 29 September 2021. Available online: https://media.defense.gov/2021/Oct/01/2002865629/-1/-1/1/DODIG-2021-133.PDF (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Mendoza, R. In-Service Corrosion Issues in Sustainment of Naval Aircraft; NAVAIR, North Island Advanced Structures Design Group: San Diego, CA, USA, 2012; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA580875.pdf (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Shipilov, S.A. Impact of materials deterioration and corrosion on the readiness of U.S. Naval Aviation. Corros. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2025, 60, 620–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molent, L.; Wanhill, R. Management of Airframe In-Service Pitting Corrosion by Decoupling Fatigue and Environment. Corros. Mater. Degrad. 2021, 2, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, S.A.; Molent, L. Investigation of an in-service crack subjected to aerodynamic buffet and manoeuvre loads and exposed to a corrosive environment. In Proceedings of the 28th International Congress of the Aeronautical Sciences (ICAS28), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 23–28 September 2012; Available online: https://www.icas.org/icas_archive/ICAS2012/PAPERS/028.PDF (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Barter, S.A.; Molent, L. Fatigue cracking from a corrosion pit in an aircraft bulkhead. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2014, 39, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Peng, P.; Ang, A.S.M.; Aston, R.W.; Schoenborn, N.D.; Phan, N.D. A comparison of the damage tolerance of AA7075-T6, AA2024-T3 and Boeing Space, Intelligence, and Weapons Systems AM built LPBF Scalmalloy. Aerospace 2023, 10, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, R.; Ang, A.; Aston, R.; Schoenborn, N.D.; Champagne, V.K.; Peng, D.; Phan, N.D. On the Growth of Small Cracks in 2024-T3 and Boeing Space, Intelligence and Weapon Systems AM LPBF Scalmalloy®. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 48, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, A.; Aston, R.; King, H.; Chan, S.S.L.; Schoenborn, N.D.; Peng, D.; Jones, R. Corrosion and Fatigue Behaviour of Boeing Space, Intelligence, and Weapons Systems Laser Powder Fusion Built Scalmalloy® in 5% NaCl. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2025, 48, 2206–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Correa, L.; González-Rovira, L.; de Dios López-Castro, J.; Botana, F.J. Pitting and intergranular corrosion of Scalmalloy® aluminium alloy additively manufactured by Selective Laser Melting (SLM). Corros. Sci. 2022, 201, 110273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smit, M.; Van Gerner, H. Material Selection and Component Optimization for a Pumped Two-Phase Cooling System Using Additive Manufacturing; NLR-TP-2017-547; NLR-Netherlands Aerospace Centre: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Available online: https://reports.nlr.nl/server/api/core/bitstreams/4c8f218e-8254-451a-9e33-5fa8b4582002/content (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Spierings, A.B.; Kern, K.; Steimer, Y.; Palm, F.; Wegener, K. Assessment of Stress Corrosion Cracking Behavior of Additively Processed Al-Mg-Sc-Zr Alloy. SVOA Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 3, 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Under Secretary, Acquisition and Sustainment, Directive-Type Memorandum (DTM)-19-006-Interim Policy and Guidance for the Use of Additive Manufacturing (AM) in Support of Materiel Sustainment; Pentagon: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dtm/DTM-19-006.pdf?ver=2019-03-21-075332-443 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Muhammad, M.; Nezhadfar, P.; Thompson, S.; Saharan, A.; Phan, N.; Shamsaei, N. A comparative investigation on the microstructure and mechanical properties of additively manufactured aluminum alloys. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 146, 106165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordner, S.; Wells, D.N.; Park, A.M. NASA’s Considerations for Materials Engineering Equivalence Methodologies in Achieving and Sustaining Efficient Qualification and Certification of AM Materials and Parts. In Proceedings of the SAE AMS AM Face to Face Meeting, Cologne, Germany, 18–20 April 2023; Available online: https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20230005203 (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- SAE International. SAE AMS4403 Specification, Aluminum Alloy Die Forgings: 7.5Zn-1.6Cu-1.5Mg-0.12Zr (7085-T7452) (Solution Heat Treated, Compression Stress-Relieved, and Overaged). 2006. Available online: https://www.sae.org/standards/content/ams4403/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Colombi, J.; Bentz, B.; Recker, R.; Lucas, B.; Freels, J. Attritable Design Trades: Reliability and Cost Implications for Unmanned Aircraft. In Proceedings of the 2017 Annual IEEE International Systems Conference (SysCon), Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–27 April 2017, ISSN 2472-9647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, J. Opinion: Unmanned Aircraft Ready to Become True Teammates. Aviation Week. 8 September 2020. Available online: https://aviationweek.com/defense/aircraft-propulsion/opinion-unmanned-aircraft-ready-become-true-teammates?elq2=9e00557a1eb840059fce18010aef464e (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- ASTM B117-19; Standard Practice for Operating Salt Spray (Fog) Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Main, B.; Molent, L.; Singh, R.; Barter, S. Fatigue crack growth lessons from thirty-five years of the Royal Australian Air Force F/A-18 A/B Hornet Aircraft Structural Integrity Program. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 133, 105426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molent, L. Managing airframe fatigue from corrosion pits—A proposal. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2015, 137, 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trathan, P.N.; Hinton, B.W. A Sensor for Monitoring Corrosive Environments on Military Aircraft. In Proceedings of the Third DSTO International Conference on Health and Usage Monitoring Systems, HUMS2003, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 11–14 February 2003; Available online: https://humsconference.com.au/Papers2003/HUMSp411.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Jones, R. Fatigue crack growth and damage tolerance. Fatigue Fract. Engng. Mater. Struct. 2014, 37, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Liu, C.C.; Zhou, J.; Wang, F.S. Effect of alternate corrosion factors on multi-axial low-cycle fatigue life of 2024-T4 aluminum alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 772, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barter, S.A.; Sharp, P.K.; Clark, G. The failure of an F/A-18 trailing edge flap hinge. Eng. Fail. Anal. 1994, 4, 255–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, B.; Main, B.; Barter, S. Equivalent initial damage sizes (EIDS) for type 1C anodised aluminium alloy 7085-T7452 under variable amplitude loading. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 153, 107578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, D.J.; Liu, J.; Sawtell, R.R.; Venema, G.B. New Generation High Strength High Damage Tolerance 7085 Thick Alloy Product with Low Quench Sensitivity. In Proceedings of the 9th International Conference on Aluminium Alloys; Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 2–5 August 2004; Nie, J.F., Morton, A.J., Muddle, B.C., Eds.; Institute of Materials Engineering Australasia Ltd.: Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 2004; pp. 969–974. Available online: http://www.icaa-conference.net/ICAA9/data/papers/GP%20141.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Mueller, L.; Suffredini, L.; Bush, D.; Sawtell, R.; Brouwer, P. ALCOA 7085 Forgings: 7th Generation Structural Solutions, 3rd ed.; Alcoa Center Publisher: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 2006; Available online: http://files.engineering.com/download.aspx?folder=3248df31-9af6-47f2-8489-4bb8abf2a20a&file=ALCOA_7085-7452_Die_Forging_green_letter_Ed_3_August_2006.pdf (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Main, B.; Barter, S.; Kongshavn, I.; Rosario, R.F.; Rogers, J.; Figliolino, M. A fractographic study of fatigue failures in combat aircraft trailing edge flap hinge lug bores in both test and service assets. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2025, 176, 109668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Jones, R.; Ang, A.S.M.; Michelson, A.; Champagne, A.; Birt, A.; Pinches, A.; Kundu, S.; Alankar, A.; Singh Raman, R.K. Computing the durability of WAAM 18Ni 250 maraging steel specimens. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2022, 45, 3535–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Jones, R.; Ang, A.S.M.; Michelson, A.; Champagne, V.; Birt, A. Further thoughts on EIDS and the durability analysis of WAAM 18Ni 250 steel with rough surfaces. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2022, 46, 1638–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Champagne, V.K.; Ang, A.S.M.; Birt, A.; Michelson, A.; Pinches, S.; Jones, R. Computing the durability of WAAM 18Ni-250 Maraging steel specimens with surface breaking porosity. Crystals 2023, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitt, S.; Jones, R.; Atluri, S. Further studies into interacting 3D cracks. Comput. Struct. 1999, 70, 583–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishioka, T.; Atluri, S. Analytical solution for embedded elliptical cracks, and finite element alternating method for elliptical surface cracks, subjected to arbitrary loadings. Eng. Fract. Mech. 1983, 17, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H. A Review on Finite Element Alternating Methods for Analyzing 2D and 3D Cracks. Digit. Eng. Digit. Twin 2024, 2, 79–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pipkins, S.D.; Atluri, S.N. Applications of the three dimensional method finite element alternating method. Finite Elem. Anal. Des. 1996, 23, 133–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Atluri, S.N. Recent advances in the alternating method for elastic and inelastic fracture analyses. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 1996, 137, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berens, A.P.; Hovey, P.W.; Skinn, D.A. Risk Analysis for Aging Aircraft Fleets—Volume 1: Analysis; WL-TR-91-3066; Flight Dynamics Directorate, Wright Laboratory, Air Force Systems Command: Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA, 1991; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a252000.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025)WL-TR-91-3066.

- Manning, S.D.; Yang, Y.N. USAF Durability Design Handbook: Guidelines for the Analysis and Design of Durable Aircraft Structures; AFWAL-TR-83-3027; Air Force Wright Aeronautical Laboratories: Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA, 1984; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA142424 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Rudd, J.L.; Yang, J.N.; Manning, S.D.; Yee, B.W. Probabilistic fracture mechanics analysis methods for structural durability. In Proceedings of the Meeting of the AGARD Structures and Materials Panel (55th), Toronto, ON, Canada, 1982; pp. 19–24. Available online: http://handle.dtic.mil/100.2/ADP001608 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- Molent, L.; Barter, S.A.; Wanhill, R.J.H. The lead crack fatigue lifing framework. Int. J. Fatigue 2011, 33, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, S.D.; Yang, Y.N. USAF Durability Design Handbook: Guidelines for the Analysis and Design of Durable Aircraft Structures; AFFDL-TR-79-3119; USAF (U. S. Air Force): Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH, USA, 1989; Available online: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA206286.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2025)AFFDL-TR-79-3119.

- Yang, J.N.; Manning, S.D.; Rudd, J.L.; Arfley, M.E. Probabilistic durability analysis methods for metallic airframes. Probabilistic Eng. Mech. 1987, 2, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Peng, D.; Chan, S.S.L.; Main, B.; Ang, A.S.M.; Phan, N.; Brindza, M.R.; Jones, R. A Comparison Between the Growth of Naturally Occurring Three-Dimensional Cracks in Scalmalloy® and Pre-Corroded 7085-T7452 and Its Implications for Additively Manufactured Limited-Life Replacement Parts. Materials 2025, 18, 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245586

Peng D, Chan SSL, Main B, Ang ASM, Phan N, Brindza MR, Jones R. A Comparison Between the Growth of Naturally Occurring Three-Dimensional Cracks in Scalmalloy® and Pre-Corroded 7085-T7452 and Its Implications for Additively Manufactured Limited-Life Replacement Parts. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245586

Chicago/Turabian StylePeng, Daren, Shareen S. L. Chan, Ben Main, Andrew S. M. Ang, Nam Phan, Michael R. Brindza, and Rhys Jones. 2025. "A Comparison Between the Growth of Naturally Occurring Three-Dimensional Cracks in Scalmalloy® and Pre-Corroded 7085-T7452 and Its Implications for Additively Manufactured Limited-Life Replacement Parts" Materials 18, no. 24: 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245586

APA StylePeng, D., Chan, S. S. L., Main, B., Ang, A. S. M., Phan, N., Brindza, M. R., & Jones, R. (2025). A Comparison Between the Growth of Naturally Occurring Three-Dimensional Cracks in Scalmalloy® and Pre-Corroded 7085-T7452 and Its Implications for Additively Manufactured Limited-Life Replacement Parts. Materials, 18(24), 5586. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245586