Metal-Coordinated Lignosulfonate Catalysts for the Selective Conversion of Hexose: Active Site and Reaction Medium

Highlights

- Sustainable metal-coordinated lignosulfonate catalysts were selected as the model catalyst to reveal the role of active sites and solvents in hexose transformation.

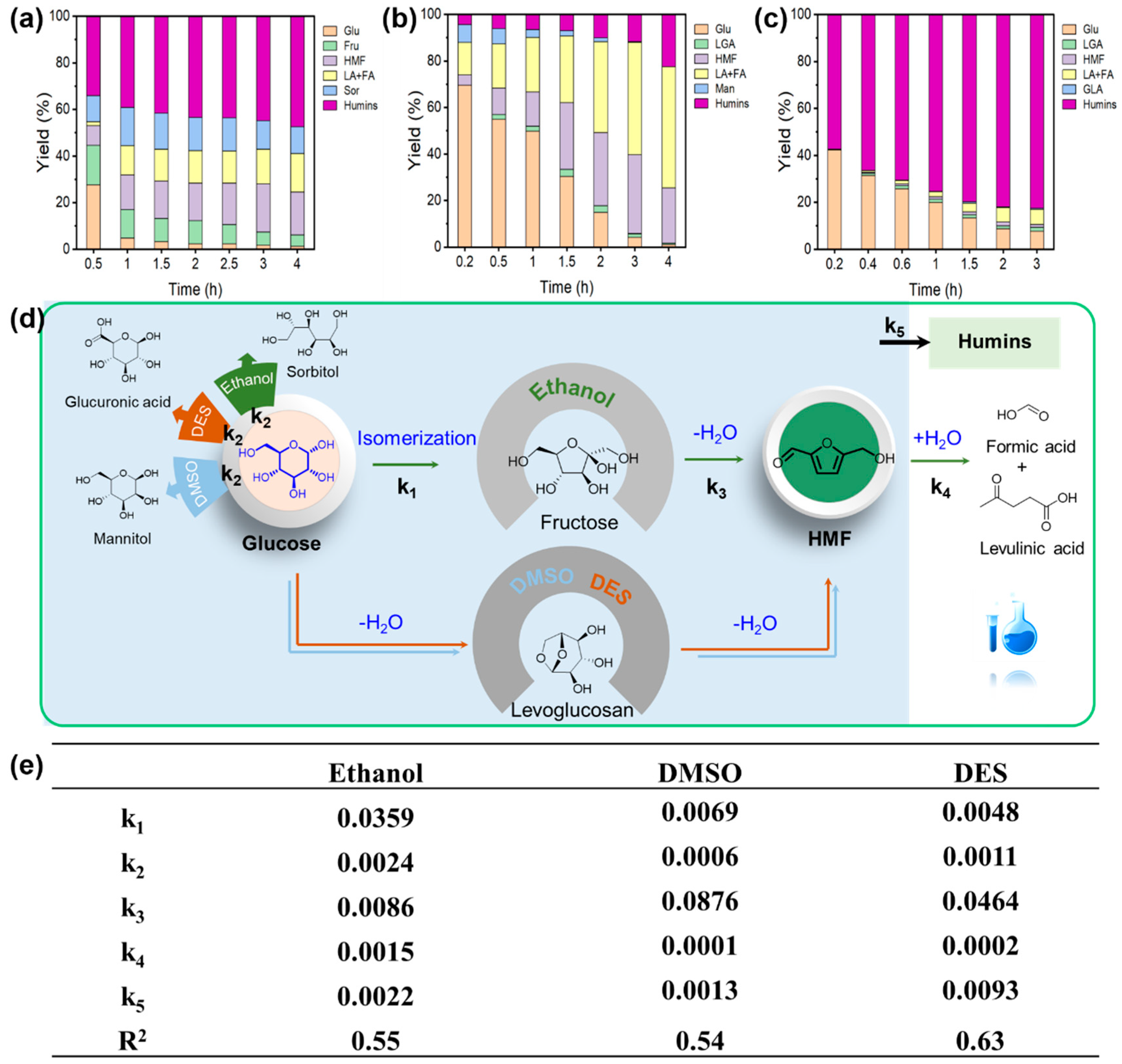

- Lewis acid–base couple sites and Brønsted acid sites regulated the transformation process.

- Isomerization or dehydration pathway of glucose was adjustable via different solvents.

- Hf-LigS showed the best catalytic activity in hexose transformation, especially isomerization reaction at high glucose concentration in ethanol.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Catalysts Preparation

2.2. Catalytic Reaction of Hexose

Glucose Isomerization Reaction

2.3. Fructose Dehydration Reaction

2.4. Direct Conversion of Glucose into HMF

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Catalytic Characterization

3.2. Effect of Catalytic Active Site on Catalytic Performance

3.2.1. Glucose-to-Fructose Isomerization

3.2.2. Fructose Dehydration to HMF

3.2.3. Glucose Dehydration to HMF

3.3. Effect of Reaction Medium on Catalytic Performance

3.3.1. Glucose-to-Fructose Isomerization

3.3.2. Fructose Dehydration to HMF

3.3.3. Glucose Dehydration to HMF

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yan, J.; Oyedeji, O.; Leal, J.H.; Donohoe, B.S.; Semelsberger, T.A.; Li, C.; Hoover, A.N.; Webb, E.; Bose, E.A.; Zeng, Y.; et al. Characterizing variability in lignocellulosic biomass: A review. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 8059–8085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatel, G.; De Oliveira Vigier, K.; Jérôme, F. Sonochemistry: What potential for conversion of lignocellulosic biomass into platform chemicals? ChemSusChem 2014, 7, 2774–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomishige, K.; Yabushita, M.; Cao, J.; Nakagawa, Y. Hydrodeoxygenation of potential platform chemicals derived from biomass to fuels and chemicals. Green Chem. 2022, 24, 5652–5690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Ma, T.; Liu, F.; Zhao, S.; Yang, J.; Li, Y.; Ji, D.; Tang, W.; et al. Highly reactive biomass waste humins derived from photocatalytic polymerization of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural for self-healing polymers. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 4595–4605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyo, B.; Schneider, M.; Radnik, J.; Pohl, M.M.; Langer, P.; Steinfeldt, N. Influence of support on the aerobic oxidation of HMF into FDCA over preformed Pd nanoparticle based materials. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2014, 478, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonyraj, C.A.; Huynh, N.T.T.; Park, S.K.; Shin, S.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.Y.; Cho, J.K. Basic anion-exchange resin (AER)-supported Au-Pd alloy nanoparticles for the oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfural (HMF) into 2, 5-furan dicarboxylic acid (FDCA). Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2017, 547, 230–236. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Fu, X.; Hu, Y.; Hu, C. Controlling the Reaction Networks for Efficient Conversion of Glucose into 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 4812–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Chai, C.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Lu, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhao, L.; Cao, F.; Chen, K.; Wei, P.; et al. CaCl2 molten salt hydrate-promoted conversion of carbohydrates to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural: An experimental and theoretical study. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 2058–2068. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, H.; Nakahara, M.; Matubayasi, N. Solvent effect on pathways and mechanisms for D-fructose conversion to 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde: In situ 13C NMR study. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117, 2102–2113. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Mittal, A.; Robichaud, D.J.; Pilath, H.M.; Etz, B.D.; St. John, P.C.; Johnson, D.K.; Kim, S. Prediction of hydroxymethylfurfural yield in glucose conversion through investigation of Lewis acid and organic solvent effects. ACS Catal. 2020, 10, 14707–14721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Morales, I.; Teckchandani-Ortiz, A.; Santamaría-González, J.; Maireles Torres, P.; Jiménez-López, A. Selective dehydration of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on acidic mesoporous tantalum phosphate. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 144, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Chang, G.; Zhang, Z.; Xing, H.; Su, B.; Yang, Q.; Ren, Q.; Yang, Y.; Bao, Z. Catalytic dehydration of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural with a bifunctional metal-organic framework. AIChE J. 2016, 62, 4403–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wu, Z.; Xu, J.; Sun, Y.; Lin, L.; Liu, S. Zeolite-promoted transformation of glucose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural in ionic liquid. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 244, 137–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tempelman, C.; Jacobs, U.; Hut, T.; de Pina, E.P.; van Munster, M.; Cherkasov, N.; Degirmenci, V. Sn exchanged acidic ion exchange resin for the stable and continuous production of 5-HMF from glucose at low temperature. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2019, 588, 117267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bounoukta, C.E.; Megías-Sayago, C.; Ammari, F.; Ivanova, S.; Monzon, A.; Centeno, M.A.; Odriozola, J.A. Dehydration of glucose to 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural on bifunctional carbon catalysts. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 286, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.S.; Tulaphol, S.; Hossain, M.A.; Jasinski, J.B.; Sun, N.; George, A.; Simmons, B.A.; Maihom, T.; Crocker, M.; Sathitsuksanoh, N. Cooperative Brønsted-Lewisacid sites created by phosphotungstic acid encapsulated metal–organic frameworks for selective glucose conversion to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Fuel 2022, 310, 122459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, W.; Su, M.; Li, S.; Shao, Q.; Ma, L. Dehydration of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and 5-ethoxymethylfurfural by combining Lewis and Brønsted acid. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 41546–41551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Hacking, J.; Heeres, H.; Yue, J. Selective fructose dehydration to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from a fructose-glucose mixture over a sulfuric acid catalyst in a biphasic system: Experimental study and kinetic modelling. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 409, 128182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, D.P.; Tran, M.H.; Lee, E.Y. Metal-organic framework-based materials as heterogeneous catalysts for biomass upgrading into renewable plastic precursors. Mater. Today Chem. 2023, 33, 101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljammal, N.; Jabbour, C.; Thybaut, J.W.; Demeestere, K.; Verpoort, F.; Heynderickx, P.M. Metal-organic frameworks as catalysts for sugar conversion into platform chemicals: State-of-the-art and prospects. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 401, 213064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tana, T.; Han, P.; Brock, A.J.; Mao, X.; Sarina, S.; Waclawik, E.R.; Du, A.; Bottle, S.E.; Zhu, H.Y. Photocatalytic conversion of sugars to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using aluminium (III) and fulvic acid. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, F.; Chen, Y.; Dang, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, D.; Qi, H. Sustainable hydrothermal self-assembly of hafnium–lignosulfonate nanohybrids for highly efficient reductive upgrading of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 1421–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Dai, F.; Xiang, Z.; Song, T.; Liu, D.; Lu, F.; Qi, H. Zirconium–lignosulfonate polyphenolic polymer for highly efficient hydrogen transfer of biomass-derived oxygenates under mild conditions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 248, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Liao, P.; Xu, T.; Lu, L.; Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Ma, L.; Wang, C. Sustainable metal-lignosulfonate catalyst for efficient catalytic transfer hydrogenation of levulinic acid to γ-valerolactone. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2022, 635, 118556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holm, M.S.; Pagán-Torres, Y.J.; Saravanamurugan, S.; Riisager, A.; Dumesic, J.A.; Taarning, E. Sn-Beta catalysed conversion of hemicellulosic sugars. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 702–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Katz, M.J.; Kerton, F.M. Catalytic conversion of glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural using zirconium-containing metal–organic frameworks using microwave heating. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 31618–31627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, C.D.; García, J.I.; Bonardd, S.; Díaz, D.D. Lignin-based catalysts for C–C bond-forming reactions. Molecules 2023, 28, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Chen, K.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, D.; Wu, Q.; Liang, D.; Hu, C.; Li, H. N-doped carbon confined CoFe@ Pt nanoparticles with robust catalytic performance for the methanol oxidation reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 13345–13354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Peng, X.W.; Zhong, L.X.; Li, Y.; Sun, R.C. Lignosulfonic acid: A renewable and effective biomass-based catalyst for multicomponent reactions. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 1366–1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renault, O.; Samour, D.; Damlencourt, J.F.; Blin, D.; Martin, F.; Marthon, S.; Barrett, N.; Besson, P. HfO2/SiO2 interface chemistry studied by synchrotron radiation x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2002, 81, 3627–3629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Zhou, B.; Zhou, H.; Wu, L.; Meng, Q.; Liu, Z.; Han, B. Porous zirconium–phytic acid hybrid: A highly efficient catalyst for Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley reductions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9399–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Yang, T.; Fang, Z. Biomass-derived mesoporous Hf-containing hybrid for efficient Meerwein-Ponndorf-Verley reduction at low temperatures. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 227, 79–89. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, Q.; Ren, L.; Kumar, P.; Cybulskis, V.J.; Mkhoyan, K.A.; Davis, M.E.; Tsapatsis, M. A chromium hydroxide/MIL-101 (Cr) MOF composite catalyst and its use for the selective isomerization of glucose to fructose. Angew. Chem. 2018, 130, 5020–5024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upare, P.P.; Chamas, A.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, J.C.; Kwak, S.K.; Hwang, Y.K.; Hwang, D.W. Highly efficient hydrotalcite/1-butanol catalytic system for the production of the high-yield fructose crystal from glucose. ACS Catal. 2019, 10, 1388–1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabushita, M.; Shibayama, N.; Nakajima, K.; Fukuoka, A. Selective glucose-to-fructose isomerization in ethanol catalyzed by hydrotalcites. ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 2101–2109. [Google Scholar]

- Botti, L.; Kondrat, S.A.; Navar, R.; Padovan, D.; Martinez-Espin, J.S.; Meier, S.; Hammond, C. Solvent-activated hafnium-containing zeolites enable selective and continuous glucose–fructose isomerisation. Angew. Chem. 2020, 132, 20192–20198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Rehman, M.L.U.; Bai, X.; Xie, C.; Lai, R.; Qian, H.; Xia, T.; Yu, G.; Tang, Y.; Xie, H.; et al. Incorporation of MgO into nitrogen-doped carbon to regulate adsorption for near-equilibrium isomerization of glucose into fructose in water. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2024, 342, 123443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraher, J.M.; Fleitman, C.N.; Tessonnier, J.P. Kinetic and mechanistic study of glucose isomerization using homogeneous organic Brønsted base catalysts in water. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 3162–3173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román-Leshkov, Y.; Moliner, M.; Labinger, J.A.; Davis, M.E. Mechanism of glucose isomerization using a solid Lewis acid catalyst in water. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 8954–8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramli, N.A.S.; Amin, N.A.S. Kinetic study of glucose conversion to levulinic acid over Fe/HY zeolite catalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 283, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudíková, J.; Mastihubová, M.; Mastihuba, V.; Kolarova, N. Exploration of transfructosylation activity in cell walls from Cryptococcus laurentii for production of functionalised β-D-fructofuranosides. J. Mol. Catal. B Enzym. 2007, 45, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Kar, A.; Srivastava, R. Improving the glucose to fructose isomerization via epitaxial-grafting of niobium in UIO-66 framework. ChemCatChem 2022, 14, e202200721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Mello, M.D.; Tsapatsis, M. Selective glucose-to-fructose isomerization over modified zirconium UiO-66 in alcohol media. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 2417–2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, H.; Nakahara, M.; Matubayasi, N. In situ kinetic study on hydrothermal transformation of D-glucose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural through D-fructose with 13C NMR. J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 14013–14021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Weitz, E. An in situ NMR study of the mechanism for the catalytic conversion of fructose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural and then to levulinic acid using 13C labeled D-fructose. ACS Catal. 2012, 2, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, L.; Zhang, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhao, L.; He, W. Metal-Coordinated Lignosulfonate Catalysts for the Selective Conversion of Hexose: Active Site and Reaction Medium. Materials 2025, 18, 5584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245584

Chen L, Zhang H, Feng Y, Zhao S, Zhao L, He W. Metal-Coordinated Lignosulfonate Catalysts for the Selective Conversion of Hexose: Active Site and Reaction Medium. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245584

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Luyu, Haoyu Zhang, Yirong Feng, Shuangfei Zhao, Lili Zhao, and Wei He. 2025. "Metal-Coordinated Lignosulfonate Catalysts for the Selective Conversion of Hexose: Active Site and Reaction Medium" Materials 18, no. 24: 5584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245584

APA StyleChen, L., Zhang, H., Feng, Y., Zhao, S., Zhao, L., & He, W. (2025). Metal-Coordinated Lignosulfonate Catalysts for the Selective Conversion of Hexose: Active Site and Reaction Medium. Materials, 18(24), 5584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245584