Interfacial Structure and Bonding Properties of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite Fabricated by Dual-Face Hot-Roll Inlaying Process

Highlights

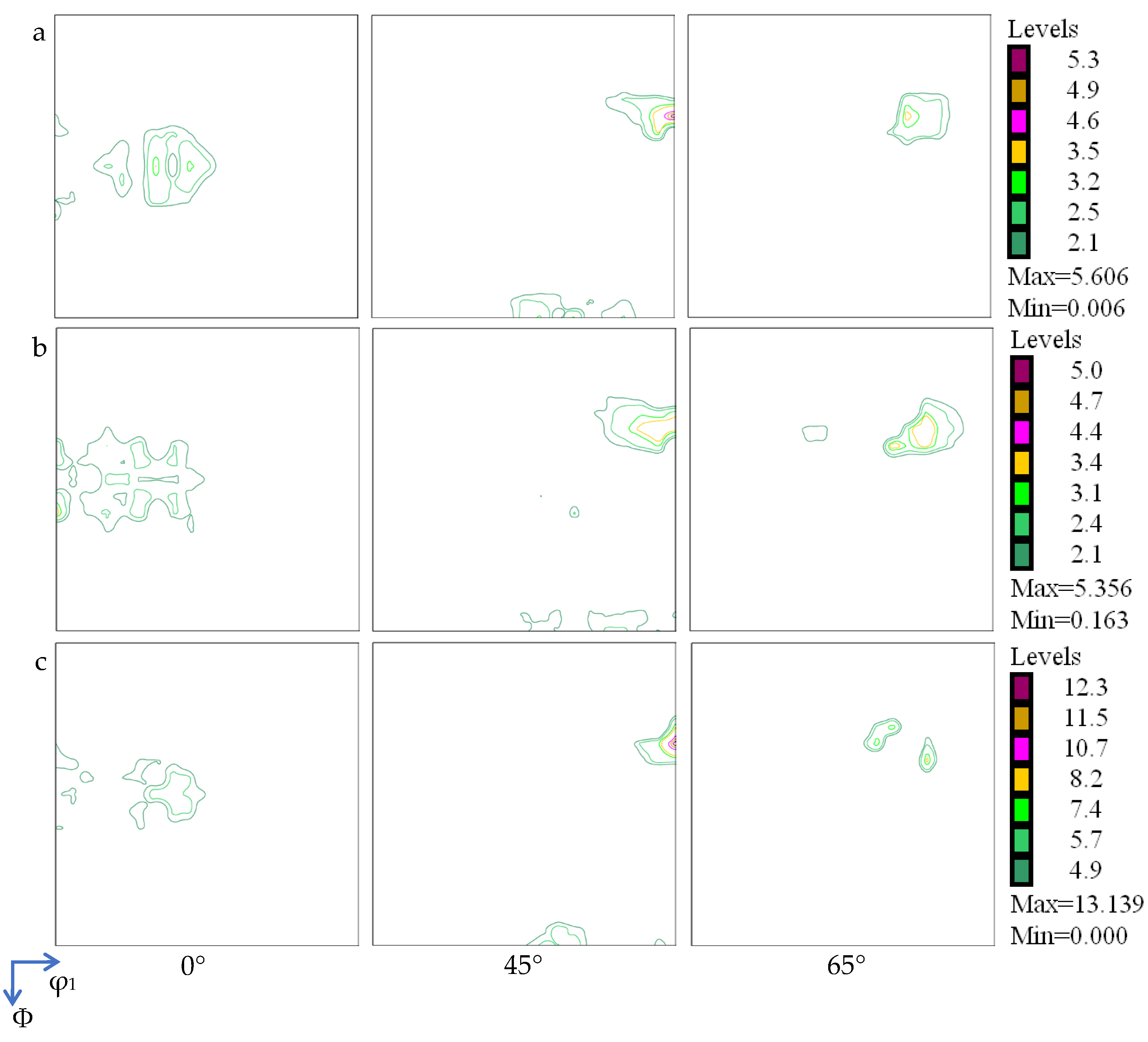

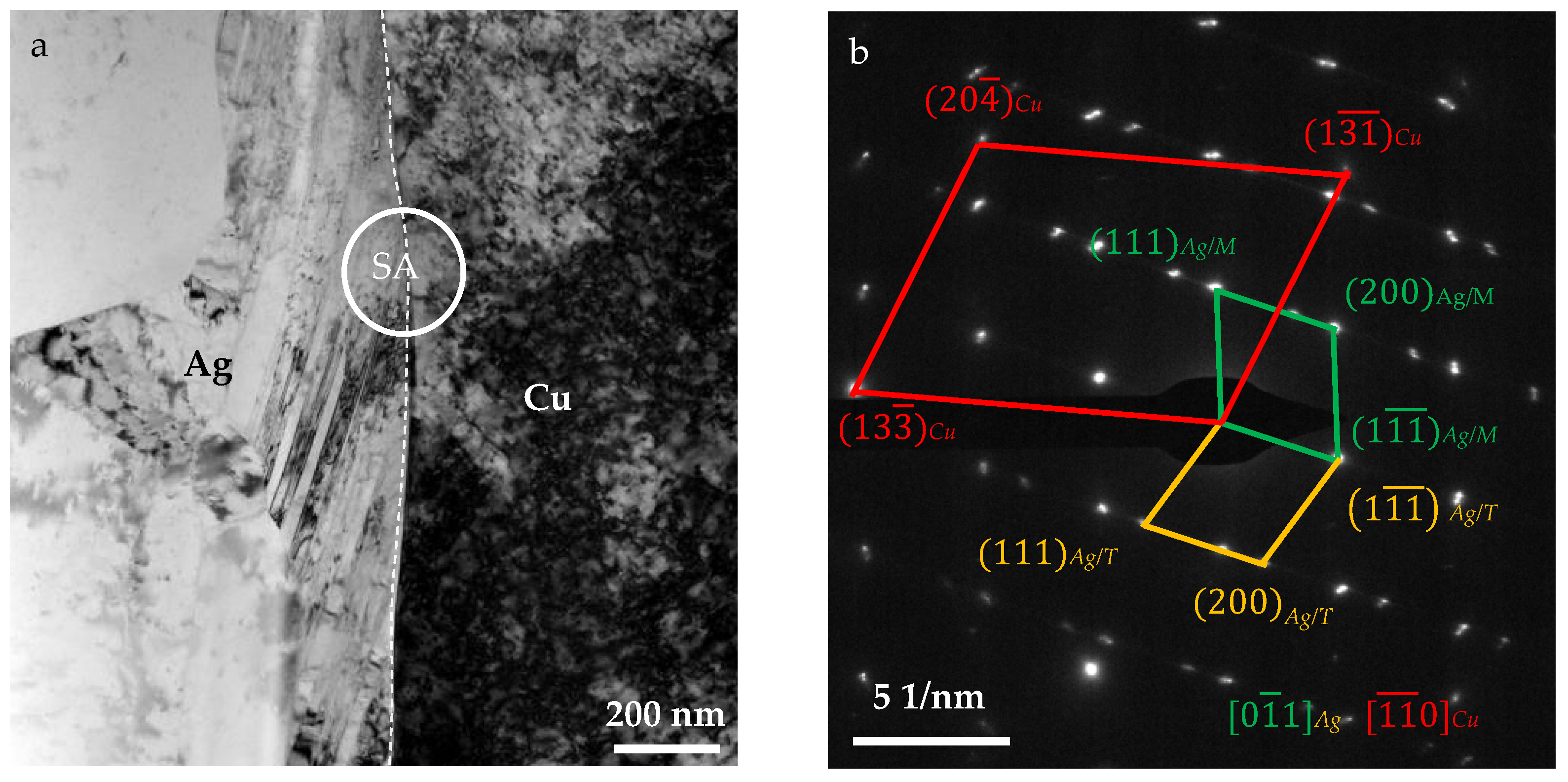

- A novel dual-face hot-roll inlaying process was developed to fabricate a Ag/Cu through-layered composite. The Ag and Cu layers had the same textural components (copper, brass, and S-type components). However, no well-matched crystallographic orientation relationship was identified at the Ag/Cu interface.

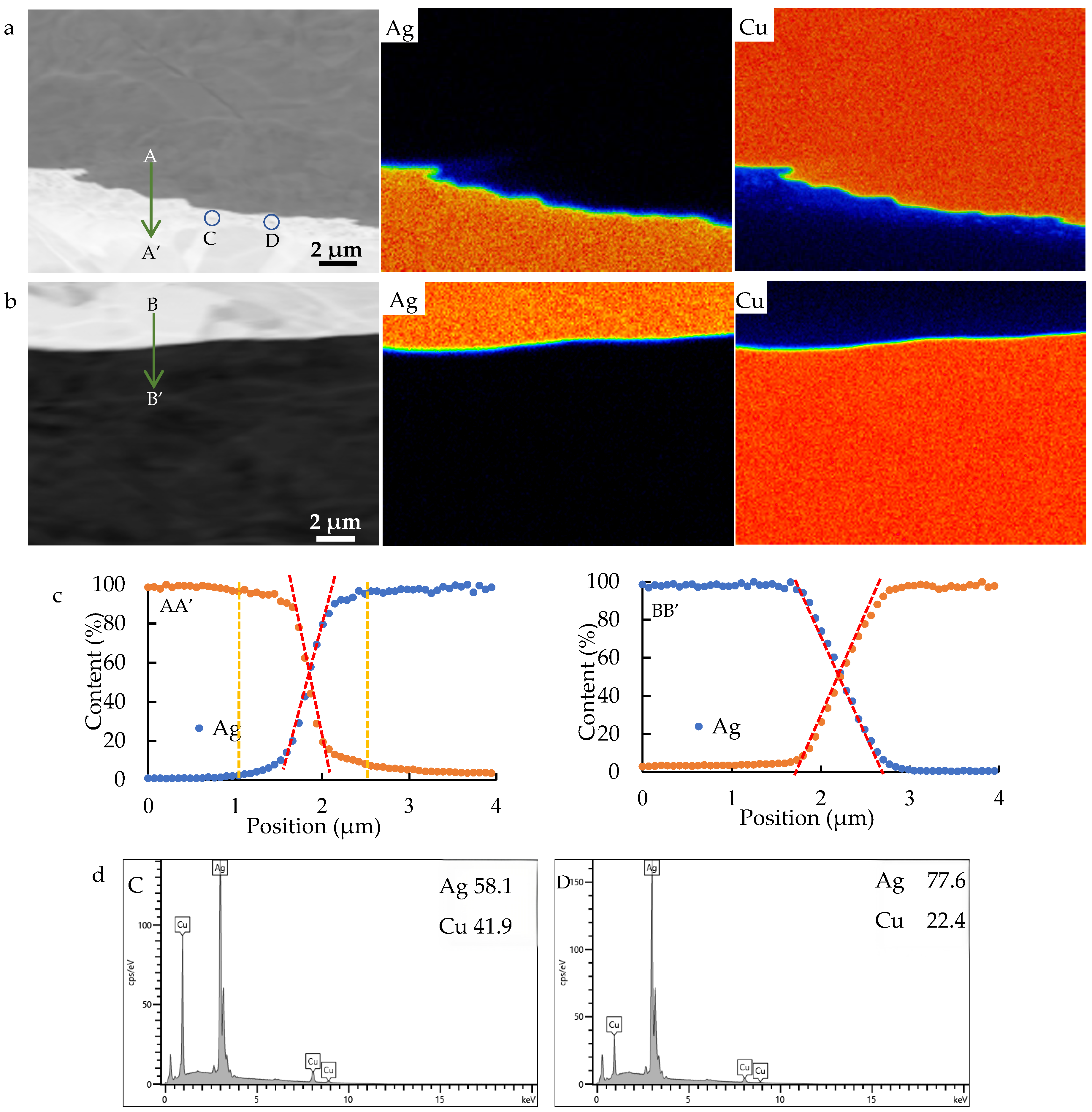

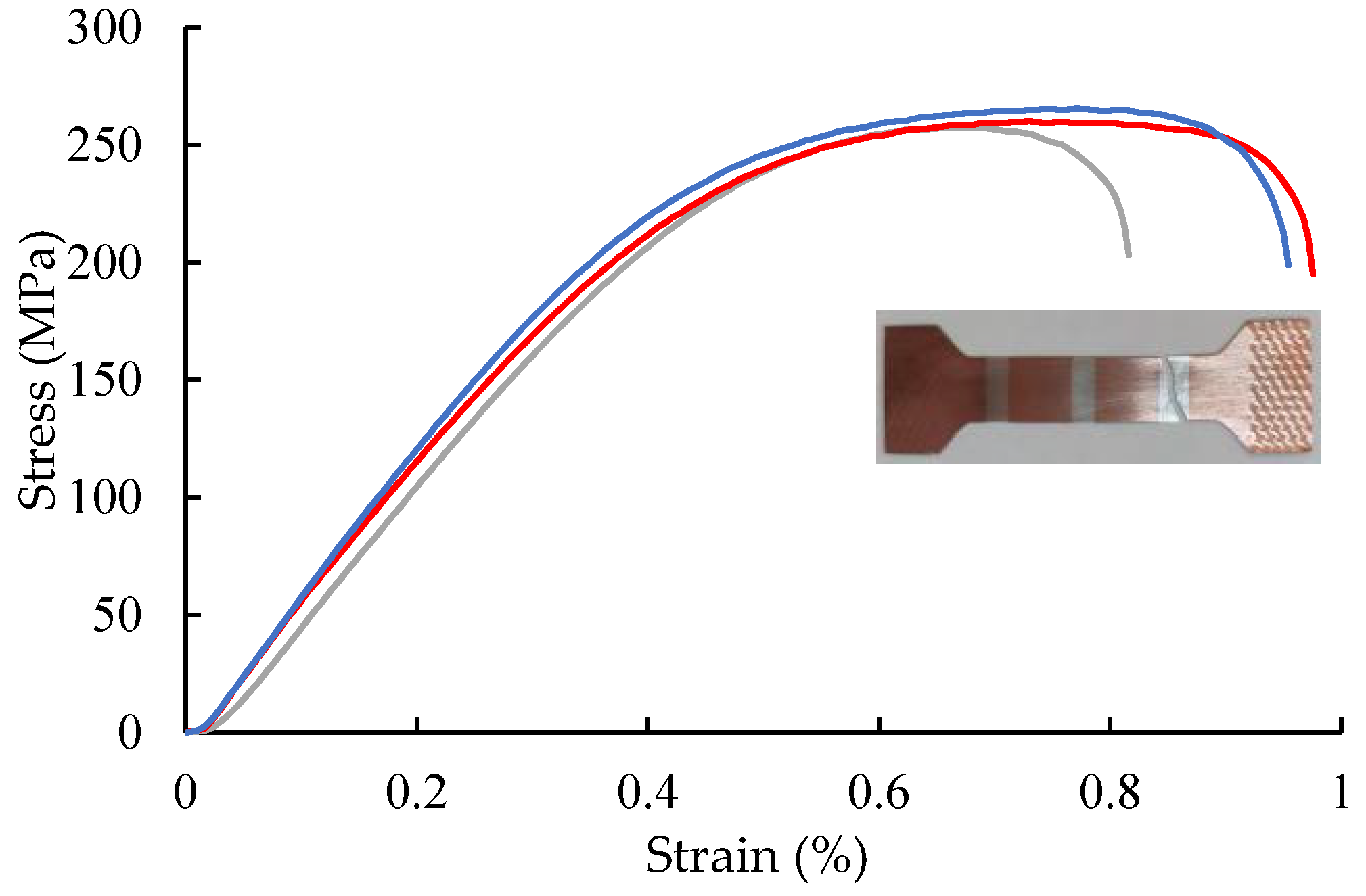

- The width of the elemental interdiffusion layer is generally less than 2 μm. The Ag/Cu interface bonding strength surpasses the tensile strength of Ag (260 MPa), and each interface contributes an increase of 1.1% to the electrical resistivity of the composite.

- This Ag/Cu through-layered composite is a promising candidate for use as a substitute for pure Ag in the fabrication of melt elements in fuses, and it is commercially available.

Abstract

1. Introduction

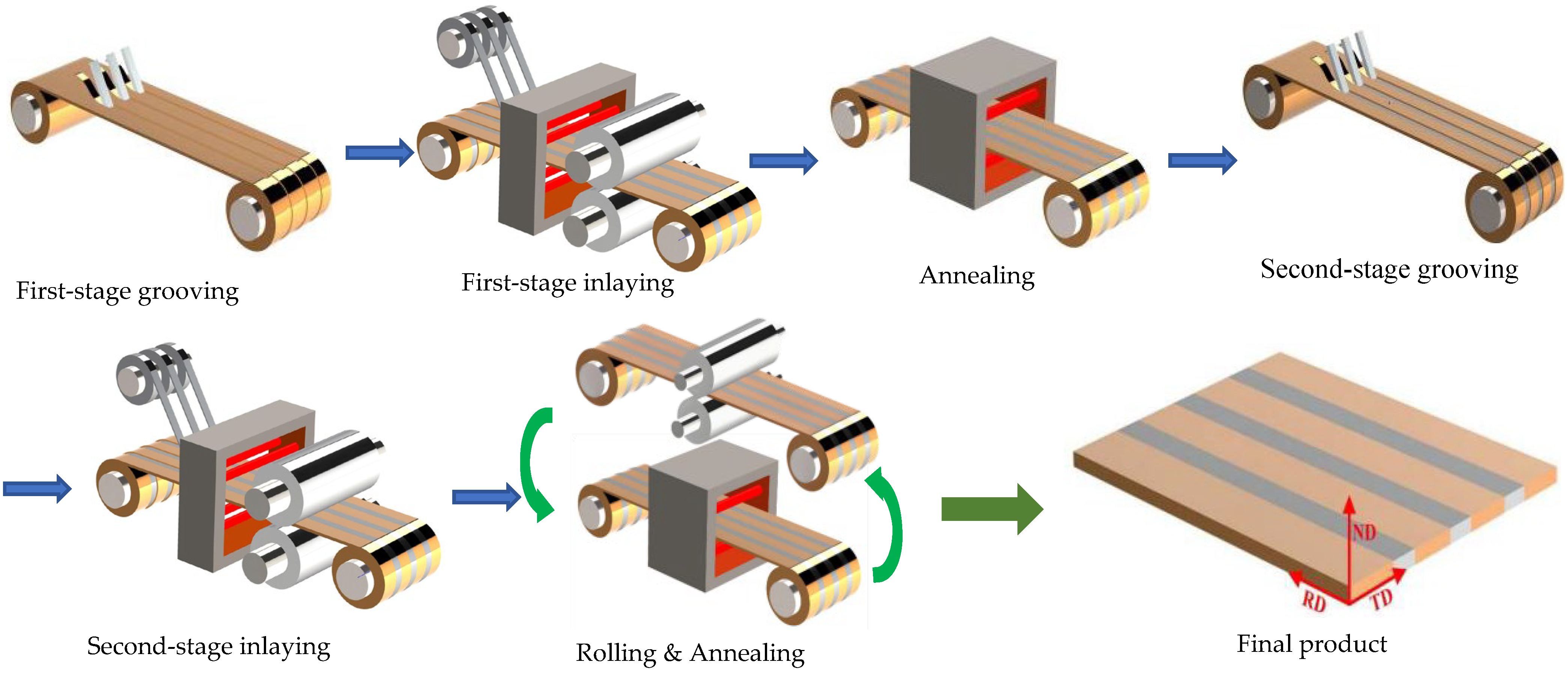

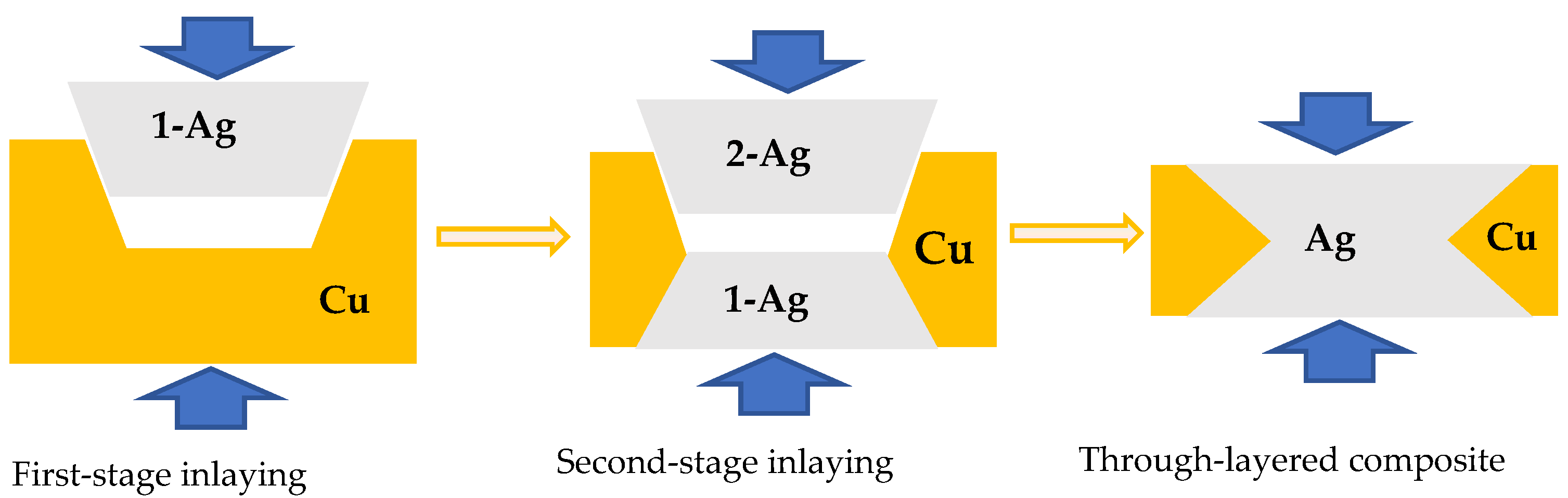

2. Brief Process of the Fabrication of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite

- A desired number of trapezoidal grooves are cut along the longitudinal direction on one surface of a Cu strip;

- Ag strips are inlaid into the grooves by hot-rolling and named 1-Ag, leading to a layered composite with Ag inlaid in Cu;

- The obtained Ag/Cu layered composite is annealed to improve the interface bonding strength;

- Trapezoidal grooves similar to those cut in step 1 are grooved on the other surface of the as-annealed composites at the positions corresponding to the inlaid Ag layers to expose their bottom surface;

- Additional Ag strips are inlaid into the grooves and named 2-Ag to obtain a through-layered Ag/Cu composite by hot-rolling;

- The through-layered Ag/Cu composite is rolled and annealed to the specified dimension with enough interface bonding strength.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Microstructure Characterization

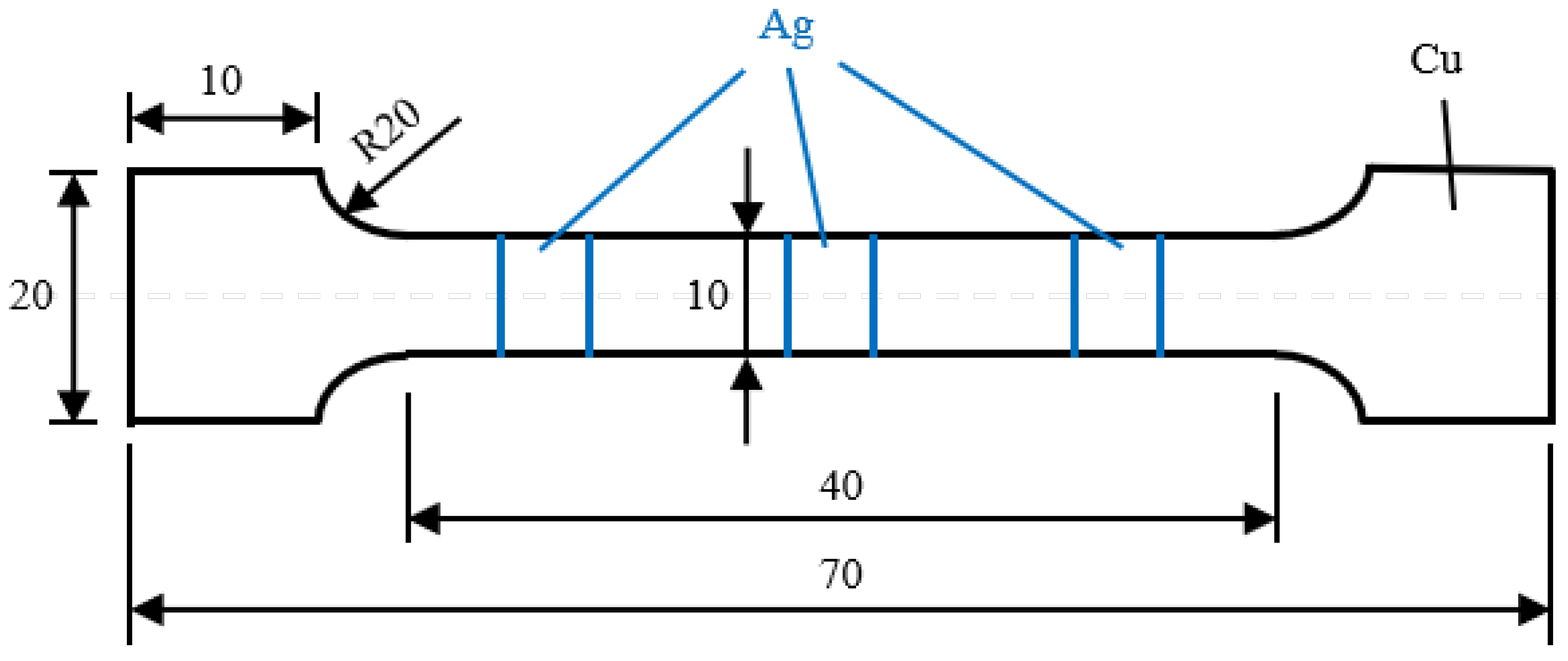

3.2. Mechanical and Electrical Properties Measurement

4. Results

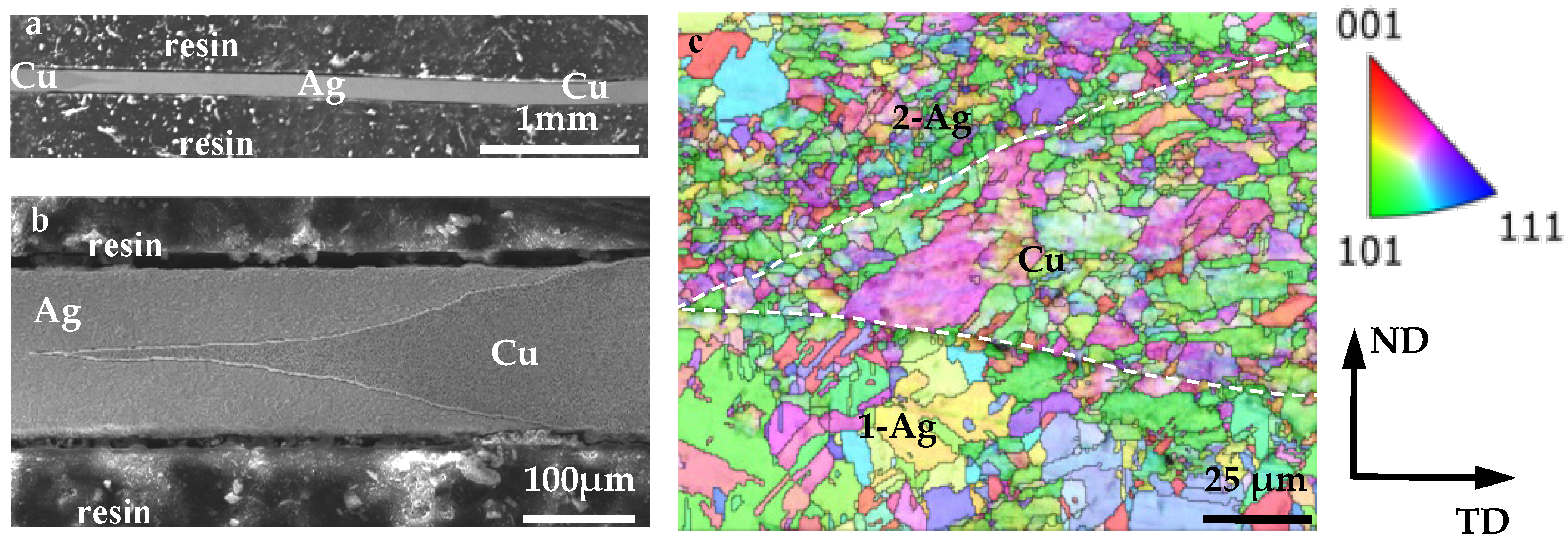

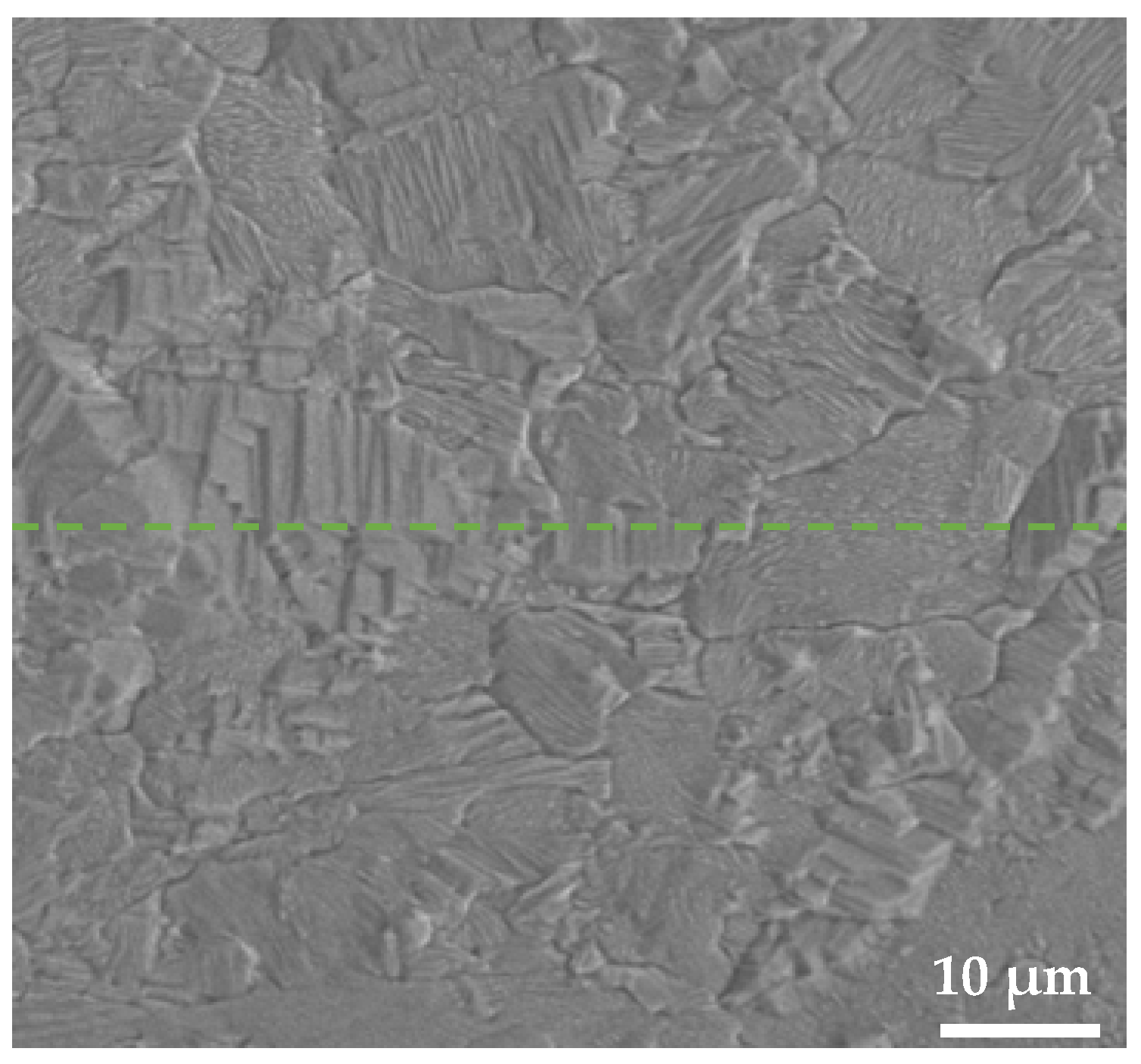

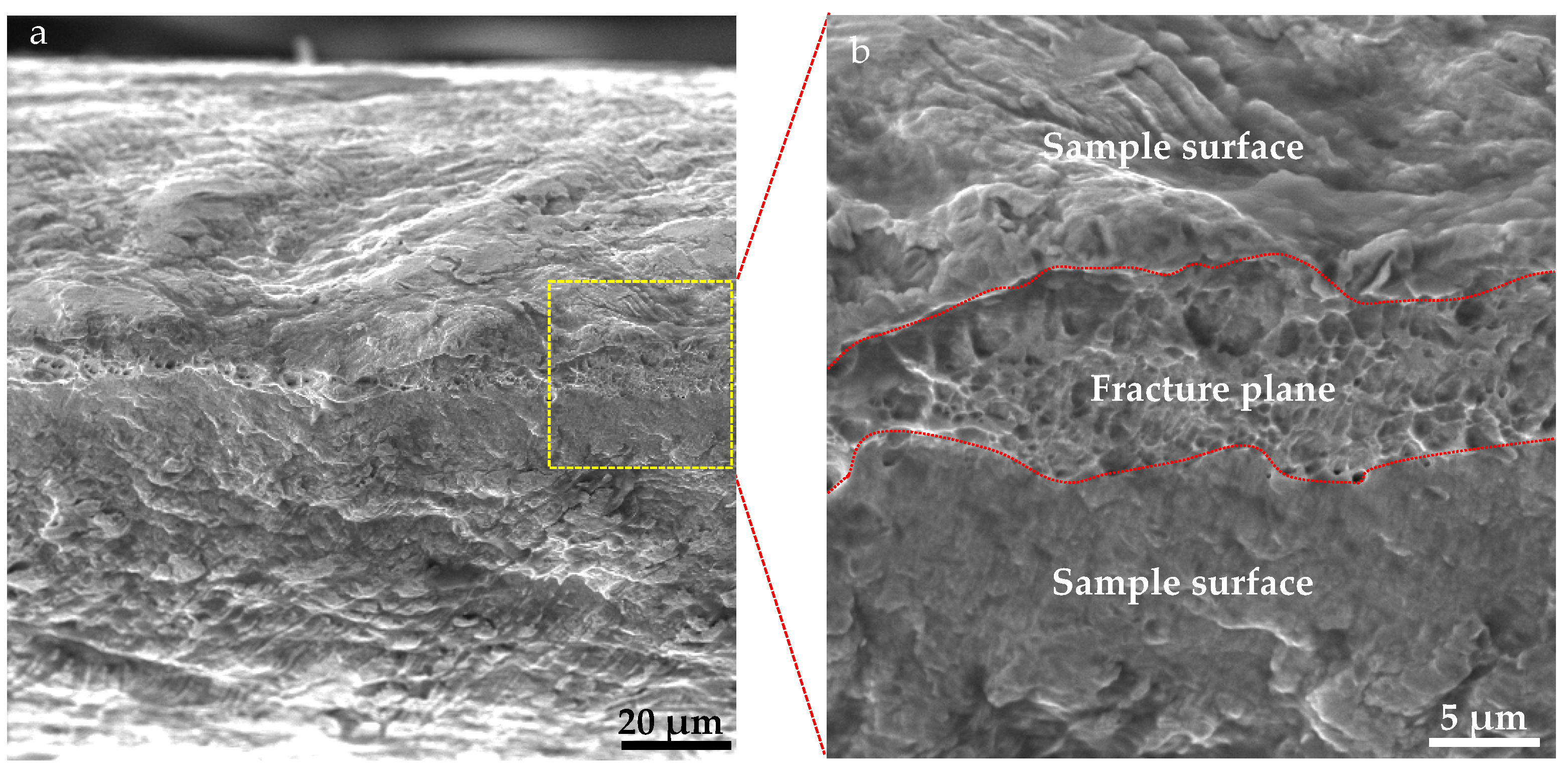

4.1. Ag/Cu Interfacial Microstructure

4.2. Crystallographic Orientation of Ag/Cu Composite

4.3. Mechanical Properties and Resistance

5. Discussion

5.1. Interdiffusion Between Ag and Cu Layer

5.2. Effect of Microstructure on Bonding Strength and Electrical Resistivity

- (1)

- Decreasing the length of the edges of the V-shaped interface under the condition of obtaining sufficient bonding strength;

- (2)

- Developing a well-matched cube-on-cube crystal orientation relationship and a semi-coherent Ag/Cu phase boundary at the interface, which is also beneficial for increasing bonding strength [53].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Misra, E.; Theodore, N.D.; Mayer, J.W.; Alford, T.L. Failure mechanisms of pure silver, pure aluminum and silver-aluminum alloy under high current stress. Microelectron. Reliab. 2006, 46, 2096–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murin-Bore, V.; Lieutier, M.; Parizet, M.J.; Barrault, M.; Melquiond, S.; Rambaud, T.; Verite, J.-C. Silver mass flow in high-voltage fuses. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2000, 33, 753–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psomopoulos, C.S.; Barkas, D.A.; Kaminaris, S.D.; Ioannidis, G.C.; Karagiannopoulos, P. Recycling potential for low voltage and high voltage high rupturing capacity fuse links. Waste Manag. 2017, 70, 204–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gelet, J.L. Thermal fatigue of electrical fuses. In Proceedings of the Conference on Fatigue Design and Material Defects (FDMD-JIP), Paris, France, 11–13 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Makan, O.; Birke, K.P. Analyzing the influence of load current on the thermal RC network response of melting-type fuses used in battery electric vehicles. Energies 2025, 18, 5583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.H.; Sun, J.H.; Liu, X.F.; Wang, W.J. Heat transfer behavior and formation mechanism of stainless steel cladding carbon steel plate during horizontal continuous liquid-solid composite casting. Int. Commun. Heat Mass 2024, 159, 108105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Yang, H.K.; Li, X.H.; Feng, X.W.; Chen, T.L.; Li, G.F. Development of accumulative roll bonding for metallic composite material preparation and mechanical/functional applications. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2024, 31, 2611–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyebia, M.; Alizadeh, M. A novel two-step method for producing Al/Cu functionally graded metal matrix composite. J. Alloy Compd. 2022, 911, 165078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.J.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, J.L.; Fan, X.Y.; Jiao, K.X. Explosion welding research on large-size ultra-thick copper-steel composites: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 24, 4130–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradar, R.; Patil, S. A systematic review on microhardness, tensile, wear, and microstructural properties of aluminum matrix composite joints obtained by friction stir welding: Past, present and its future. Trans. Indian Inst. Met. 2024, 77, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, B. Recent advances in brazing fillers for joining of dissimilar materials. Metals 2021, 11, 1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.Y.; Jiu, Y.T.; Long, W.M.; Zhong, S.J.; Hou, J.T.; Ren, X.F.; Zhao, J.C.; Zhang, G.X.; Wei, S.Z. Microstructural evolution and bonding characteristics of Ag/Cu interface in Ag/Cu bimetallic strips fabricated via diffusion welding. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2025, 32, 14681476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.X.; Wen, D.S.; Wang, X.W.; Kong, B.B.; Lv, Q.H.; Zhang, M.H.; Gong, Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Yang, X.F.; Wang, S.R. A novel approach to the fabrication and mechanical properties of Al/Ta laminated composites via vacuum-embedded diffusion welding. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1021, 179714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Meng, L.; Zhou, S.P.; Yang, F.T. Behaviors of the interface and matrix for the Ag/Cu bimetallic laminates prepared by roll bonding and diffusion annealing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2004, 371, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Guo, Y.C.; Zhu, D.; Shan, G.B.; Yang, G.Y.; Chen, Y.Z. In situ observation of destabilization of a nanostructured Ag/Cu multilayer fabricated via multicomponent accumulative roll bonding. Mater. Des. 2023, 236, 112487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhou, S.P.; Yang, F.T.; Shen, Q.J.; Liu, M.S. Diffusion annealing of copper-silver bimetallic strips at different temperatures. Mater. Character 2001, 47, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, S.P.; Yang, F.T. Effects of rolling and sintering temperature on peel strength of bonding interfaces for Ag/Cu bimetallic strips. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2003, 19, 779–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, Y.F.; Li, P.Y.; Hou, J.T.; Liu, F.L.; Qin, J.; Hao, Q.L.; Zhong, S.J. Microstructure of interfacial diffusion layer of cross-layered silver-copper composite strip and its effect on resistivity. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2025, 32, 1940–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.N.; Wang, T.; Liu, F.L.; Yang, J.; Qin, J.; Cheng, Y.F. Effect of surface roughness on the properties of Ag/Cu composite strips. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 10516–10525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Q.; Yang, W.F.; Liu, B.X.; Zheng, S.J. Interface effects on the properties of Cu-Nb nanolayered composites. J. Mater. Res. 2020, 35, 2684–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.J.; Liu, X.F.; Ma, X.; Tian, S.J.; Cui, Q.H. Research status and prospects of the fractal analysis of metal material surfaces and interfaces. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2025, 32, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Yang, T.S.; Wang, L.Y.; Hua, C.J.; Zhang, H.X.; Chen, H.Q.; Zhu, Q. Study on cladding casting technology of large steel ingot and interface bonding between cladding layers. Int. J. Cast Metal. Res. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Zhu, D.; Yang, T.Y.; Xia, F.; Chen, Q.; Guo, Y.C. Interface-dominated microstructure development and mechanical and electrical properties of Al/Cu multilayered composites prepared via multicomponent accumulative roll bonding. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1017, 179149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.P.; Xie, W.B.; Miao, S.; Liang, T.X.; Zeng, L.F.; Zhang, X.H.; Wang, H. High strength, high electrical conductivity and thermally stable bulk Cu/Ag nanolayered composites prepared by cross accumulative roll bonding. Mater. Des. 2021, 200, 109455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubicza, J.; Hegedus, Z.; Lábár, J.L.; Kauffmann, A.; Freudenberger, J.; Sarma, V.S. Solute redistribution during annealing of a cold rolled Cu-Ag alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 623, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.B.; Zeng, Y.W.; Meng, L. Interface structure and energy in Cu-71.8 wt.% Ag. J. Alloys Compd. 2008, 464, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Beyerlein, I.J.; Mara, N.A.; Bhattacharyya, D. Interface-facilitated deformation twinning in copper within submicron Ag-Cu multilayered composites. Scripta Mater. 2011, 64, 1083–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.F. Stability of interfaces in a multilayered Ag-Cu composite during cold rolling. Scr. Mater. 2013, 68, 542–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X.H.; Zhu, S.M.; Cao, Y.; Kawasaki, M.; Liao, X.Z.; Ringer, S.P.; Nie, J.F.; Langdon, T.G.; Zhu, Y.T. Atomic-scale investigation of interface-facilitated deformation twinning in severely deformed Ag-Cu nanolamellar composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2015, 107, 011901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.Z.; Zhang, Z.F. Bulk eutectic Cu-Ag alloys with abundant twin boundaries. Scr. Mater. 2012, 66, 65–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Weng, H.; Tang, C.L. Interfacial bonding mechanism of aluminium and steel composites. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2018, 27, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.H.; Liu, T.T.; Guo, C.D.; Song, B.; Peng, H.; Jiang, X.Q. Effects of pre-cold corrugated pressing on the interface and bonding strength of hot-pressed Mg/Al laminated composite plates. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025; early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.L.; Liu, X.O.; Liang, S.A.; Yang, Y.H.; Liu, X.F.; Wang, W.J. Influence of surface state on interface bonding strength of Al/Ta laminated composite via differential temperature rolling. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 915, 147279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.D.; Zhang, S.Q.; Xu, J.H.; Zhang, Z.H.; Shao, W.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, J.H.; Chen, S.H.; Ye, Z.; Wang, W.L.; et al. Investigation on enhanced strength in W/(Ti/Cu) composite interlayer/steel diffusion bonding joint based on controlled diffusion mechanism. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2025, 343, 118978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Guo, C.D.; Tan, S.J.; Song, B.; Wang, M.; Huang, G.S.; Zheng, K.H.; Pan, F.S. Effect of hot-pressing rate on interface and bonding strength of Mg/Al composite sheets with Zn interlayer. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2024, 33, 10216–10227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.H.; Li, J.J.; He, W.J.; Bai, S.W.; Peng, J.; Jiang, B. Effect of diffusion bonding temperature on the microstructure and interfacial shear strength of TA15/cemented carbide composite plate with V/Fe composite intermediate layers. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2500089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Luo, Y.Z.; Xie, Y.Q.; Tan, Z.Q.; Fan, G.L.; Guo, Q.; Su, Y.S.; Li, Z.Q.; Xiong, D.B. The influence of interface structure on the electrical conductivity of graphene embedded in aluminum matrix. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 6, 1900468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.H.; Zhang, P.; Yang, X.J.; Chen, Y. Evolution of interface microstructure and tensile properties of AgPd30/CuNi18Zn26 bilayer laminated composite manufactured by rolling and annealing. Metals 2022, 12, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.X.; Huang, P.; Gao, Q.; Su, X.X.; Feng, Z.H.; Peng, L.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.H.; Zu, G.Y. Influence of continuous annealing on the interfacial compound evolution and mechanical behavior of hot-rolled titanium/steel composite plates. Mater. Des. 2025, 253, 113818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 228.1-2010; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1 Method of Test at Room Temperature. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2010.

- Mehr, V.Y.; Toroghinejad, M.R.; Rezaeian, A.; Asgari, H.; Szpunar, J.A. A texture study of nanostructured Al-Cu multi-layered composite manufactured via the accumulative roll bonding (ARB). J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2909–2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, C.; Son, K.; Cho, H. Experimental analysis of deformation texture evolutions in pure Cu, Cu-37Zn, Al-6Mg, and -8Mg alloys at cold-rolling processes. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 934, 167879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Kumar, R.; Kaushik, L.; Shukla, S.; Tandon, V.; Choi, S.H. Microstructure and texture evolution in thermomechanically processed FCC metals and alloys: A review. Korean. J. Met. Mater. 2024, 62, 564–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.J.; Wang, J.; Carpenter, J.S.; Mook, W.M.; Dickerson, P.O.; Mara, N.A.; Beyerlein, I.J. Plastic instability mechanisms in bimetallic nanolayered composites. Acta Mater. 2014, 79, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, F.; Liu, X.F.; Pan, Y. Effect of process parameters on the interface microstructure and thickness of silver cladding copper wires prepared by core-cladding continuous casting. In Proceedings of the Chinese Materials Conference 2017, Yinchuan, China, 6–12 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ciano, M.D.; Caron, E.J.F.R.; Weckman, D.C.; Wells, M.A. Interface formation during Fusio™ casting of AA3003/AA4045 aluminum alloy ingots. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2015, 46, 2674–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Niu, J.Y.; Zhao, Y.K.; He, Y.B.; Ren, Z.F.; Chen, H.Q. Study on the cladding path during the solidification process of multi-layer cladding of large steel ingots. High Temp. Mat. Process. 2023, 42, 20220267. [Google Scholar]

- Seleznev, M.; Mantel, J.; Schmidtchen, M.; Prahl, U.; Biermann, H.; Weidner, A. Steel-steel laminates manufactured via accumulative roll bonding. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.M.; Jia, N.; Wang, X.L.; Zhao, X.; Zuo, L. Inhomogeneous texture distribution in a Cu-Ag lamellar composite processed by cold rolling. Mater. Trans. 2016, 57, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Zhang, N.; Yu, L.; Lu, W.Q.; Li, J.G.; Hu, Q.D. Recent progress in metallurgical bonding mechanisms at the Liquid/Solid interface of dissimilar metals investigated via in situ X-ray imaging technologies. Acta Metall. Sin.-Engl. 2021, 34, 145–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; Chen, Y.L.; Wei, B.B.; Zheng, G.M.; Fan, Z.Z.; Zou, J.T.; Tang, B.; Li, J.S. Enhanced tensile strength of TiAl/Ti2AlNb diffusion bonding joint by a novel post-bonded hot deformation. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 3598–3605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishara, H.; Lee, S.; Brink, T.; Ghidelli, M.; Dehm, G. Understanding grain boundary electrical resistivity in Cu: The effect of boundary structure. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 16607–16615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Q.L.; Li, Y.B.; Ye, P.H.; Fu, W.J.; Cao, G.J.; Han, Q.H.; Li, X.W.; Wu, H.; Fan, G.H. The effect of the interface structure on the interfacial bonding strength of Ti/Al clad plates. Prog. Nat. Sci.-Mater. 2025, 35, 568–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Position | Ag/Cu-Ⅰ | Ag/Cu-Ⅱ | Ag/Cu-Ⅲ | Cu | Ag |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HV | 71.2 ± 4.3 | 73.2 ± 5.5 | 72.3 ± 4.8 | 60.9 ± 3.5 | 111.4 ± 6.6 |

| Total Width of Different Layers/cm | Measured Resistance /mΩ | Measured Resistivity /mΩ·cm | Calculated Resistivity /mΩ·cm | Deviation /% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Cu | ||||

| 1.02 | 4.08 | 0.63 | 1.78 × 10−3 | 1.67 × 10−3 | 6.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Guo, K.; Liu, T.; Zhao, X.; Huang, L.; Ruan, H.; Zhou, X.; Chen, Y. Interfacial Structure and Bonding Properties of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite Fabricated by Dual-Face Hot-Roll Inlaying Process. Materials 2025, 18, 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245580

Wang Y, Yang Q, Guo K, Liu T, Zhao X, Huang L, Ruan H, Zhou X, Chen Y. Interfacial Structure and Bonding Properties of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite Fabricated by Dual-Face Hot-Roll Inlaying Process. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245580

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yong, Quanzhen Yang, Kunshan Guo, Tianhao Liu, Xue Zhao, Lei Huang, Haiguang Ruan, Xiaorong Zhou, and Yi Chen. 2025. "Interfacial Structure and Bonding Properties of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite Fabricated by Dual-Face Hot-Roll Inlaying Process" Materials 18, no. 24: 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245580

APA StyleWang, Y., Yang, Q., Guo, K., Liu, T., Zhao, X., Huang, L., Ruan, H., Zhou, X., & Chen, Y. (2025). Interfacial Structure and Bonding Properties of Ag/Cu Through-Layered Composite Fabricated by Dual-Face Hot-Roll Inlaying Process. Materials, 18(24), 5580. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245580