After explaining the LCA methodology used in the case study, the main results obtained from the research are interpreted and discussed. This is divided into several sections. The first outcome aims to evaluate which materials and processes contribute most to the environmental impact of the reference mortar. Subsequently, the rest of the section compares the results of Scenarios I and II through a sensitivity analysis and, finally, an economic analysis.

It should be noted that the results are primarily presented based on the functional unit defined in this study (0.0032 m3 of mortar). However, the results have also been extrapolated to a larger volume of 1 m3. Accordingly, the relative increases or decreases in environmental impacts across the assessed impact categories remain effectively the same when scaled to 1 m3, due to the linear relationship between material quantities, mix proportions in the unit processes and the resulting environmental impacts. These outcomes are presented in detail in the following subsections.

3.1. Reference Mortar Without Biochar Added

This first result, although it may seem very obvious, is fundamental to understanding how any additive can affect mortar mixes and what strategies in terms of environmental results can be defined as future lines of research.

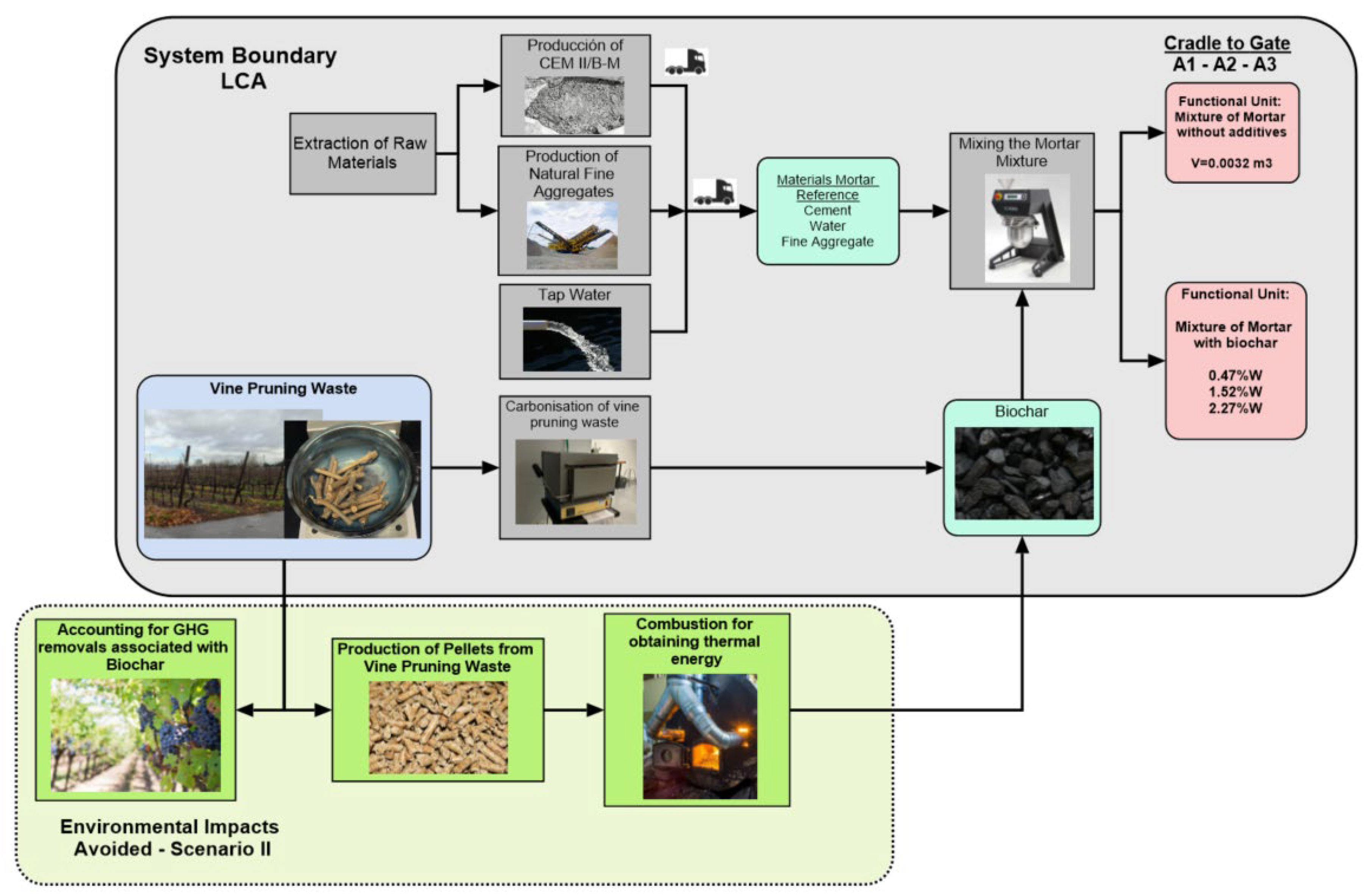

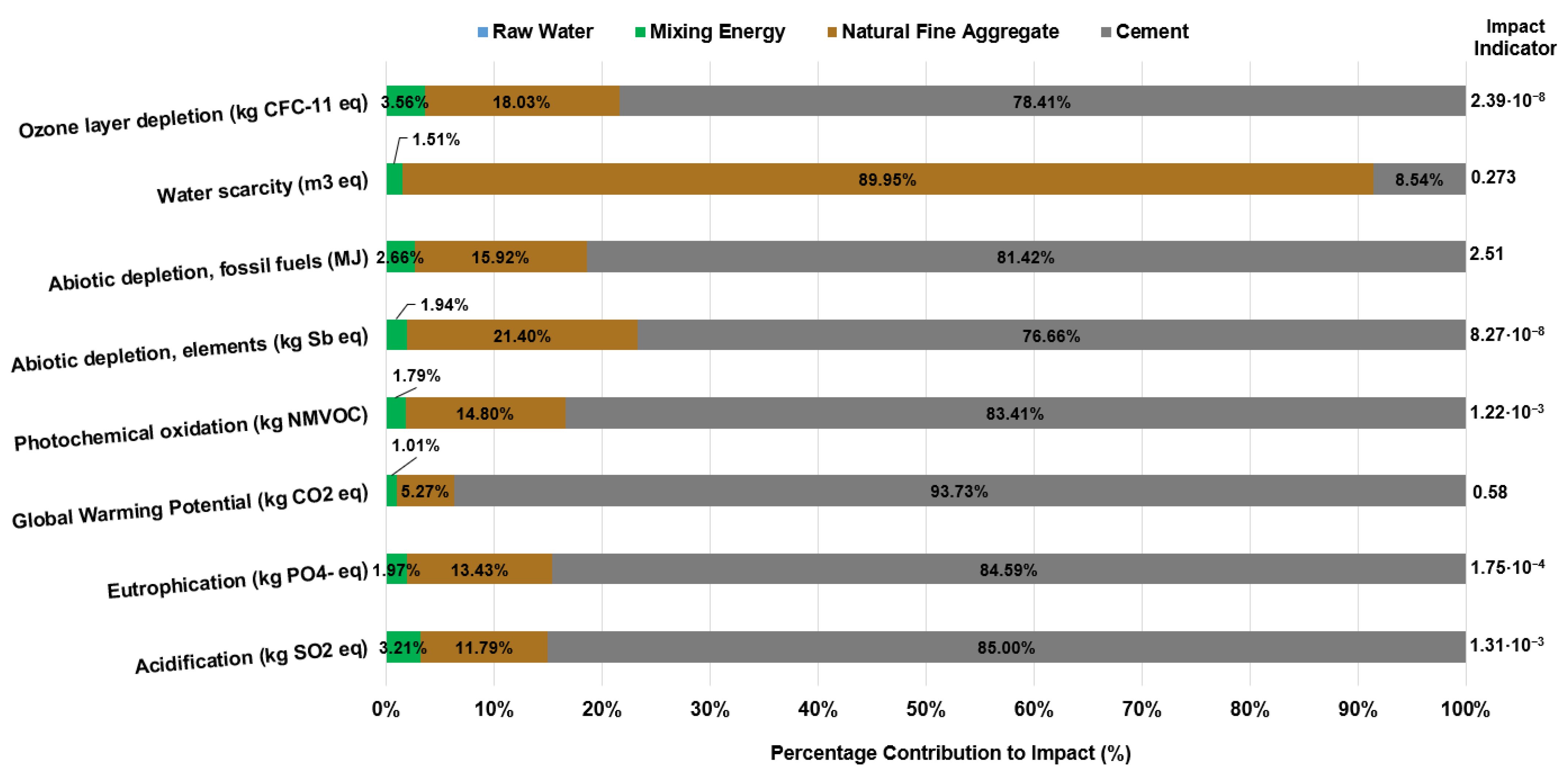

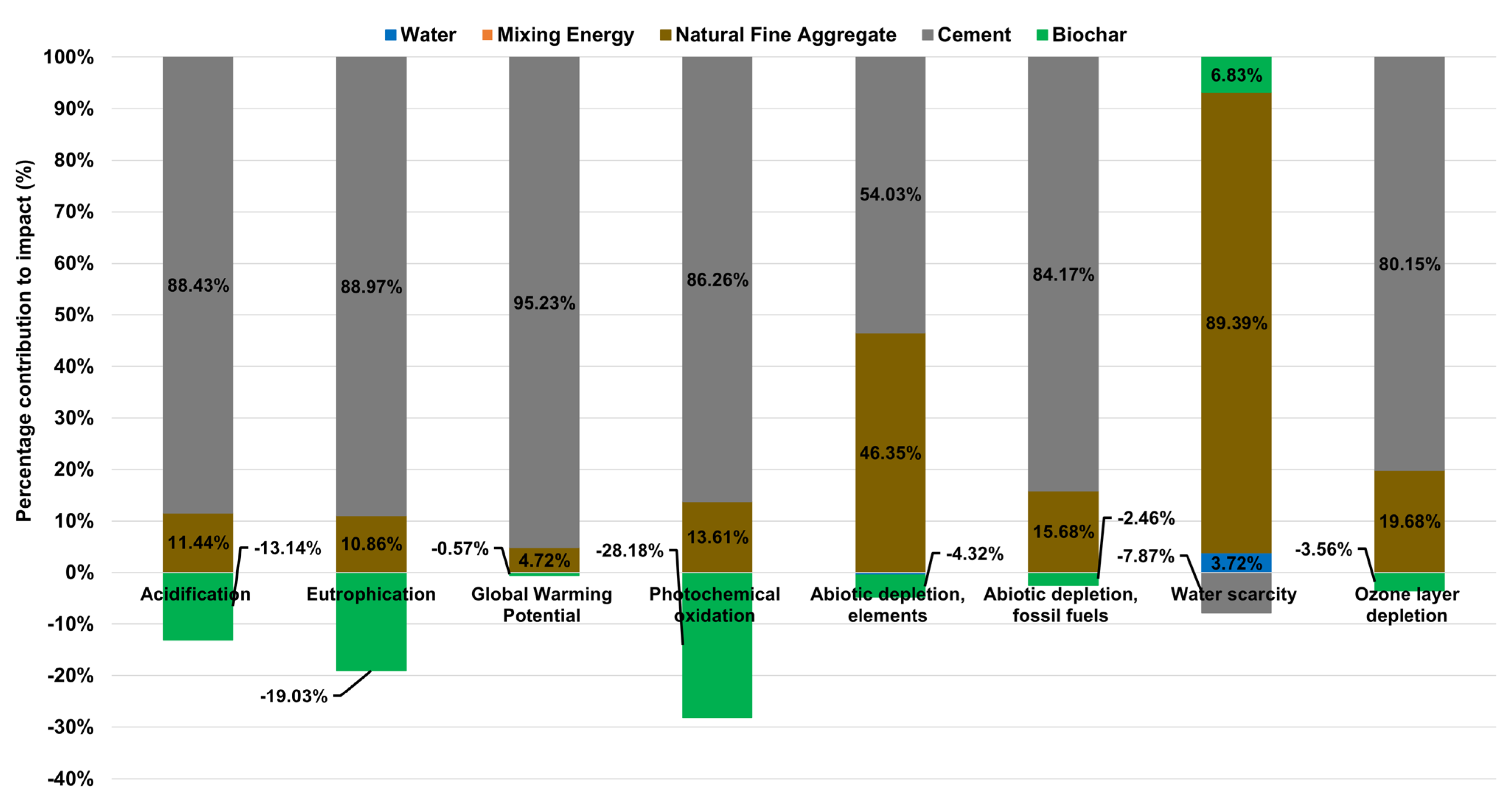

Figure 2 shows the x-axis representing the percentage contribution (%) of each material in the mortar mix that directly affects that category of impact assessed. The right-hand column shows the indicator value for each impact category, i.e., the calculation of all environmental impacts (see also

Table A2).

A first general observation shows that the main contributor to the generation of environmental impacts in mortar mixing and in the various impact categories is CEM II/B-M cement. This is followed, in second place, by natural fine aggregate (sand), then the unit process of mixing the materials. Finally, to a negligible extent, the environmental impact generated by the water used in the mixture. The main reason for arranging the environmental impacts on mortar in this way lies in the production process for generating CEM II/B-M cement, which involves high energy consumption, especially of fossil fuels or electricity from the grid. They are used directly as a fuel source in rotary kilns, where limestone (CaCO3) is decomposed into calcium oxide (CaO) and carbon dioxide (CO2) at around 1400–1500 °C, in the presence of secondary materials such as silica, iron and alumina to produce clinker or Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC).

This cement manufacturing process has a considerable impact, as shown in

Figure 2, for impact categories such as Fossil Fuel Depletion 68.96% (2.04 MJ), Global Warming Potential 88.77% (0.539 kg CO

2 eq) and other impact categories directly related to the use of traditional energy sources, Acidification 77.81% (1.11 × 10

−3 kg SO

2 eq) and Eutrophication 76.61% (1.48 × 10

−4 kg PO

4− eq). Consequently, it follows that the higher the amount of clinker in the cement type, the greater the increase in environmental impacts. Therefore cements with high clinker content such as CEM I (95–100% by mass) have environmental impacts that are even 21.4% higher in certain impact categories such as Global Warming Potential than cements with lower clinker content such as CEM II (65–79% by mass) [

32], which is a well-established sustainability strategy in the cement industry.

Taken from the functional unit of the reference mortar mix, the average impact percentage for cement material is 66.58%, followed by fine aggregate with 31.33% and finally the mixing and kneading process with an average impact value of 1.97%. For water, the impact is 0.12% for the various categories. These results show that if a cut-off rule were applied, which basically consists of establishing a base percentage, for example, 1%, those materials or unit processes whose impact contribution is less than the percentage established by the cut-off rule could be excluded from the LCA system boundary. This results in an effective way to save complexity in the process of elaborating the system boundary (

Figure 1) and consequently the creation of the LCI.

3.2. Environmental Results—Scenario I

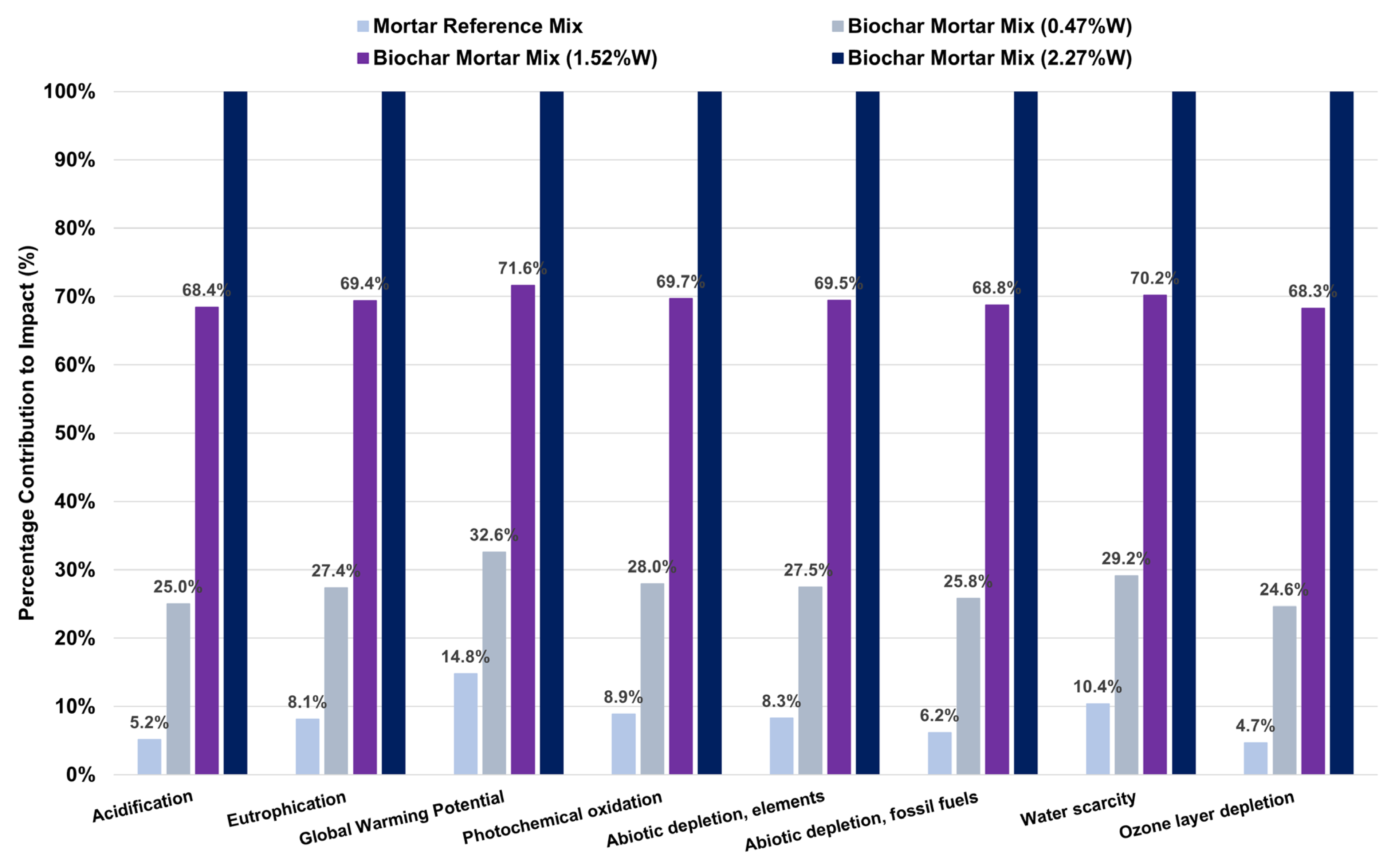

This first result (see

Figure 3 and

Table A3) explains the environmental comparison between the reference mortar mixes and those with a percentage of biochar additive added by mass for Scenario I, where the approach used is without incorporation of the biochar present in the biochar, as well as the processes/products avoided. As can be seen in general, as the use of biochar in the mix increases, the environmental impacts grow exponentially for all impact categories assessed in the EPD methodology.

The rationale is that biochar does not replace any primary element such as cement in the mix; therefore, there may be a certain environmental advantage in reducing the percentage by mass of the original CEM II/B-M. Secondly, the production of biochar from pruning waste has a fairly high environmental impact on the defined functional unit. These environmental burdens are mainly associated with the process of carbonising the vine shoot residues at 450 °C for three hours in a muffle furnace, whose energy source is the national electricity grid itself (see

Table 6).

If we analyse the increases observed with respect to the reference mortar mix, for example, for Scenario I, in the Global Warming Potential impact category, it turns out that using 0.47%W of biochar leads to an increase of 17.83% (+0.7 kg CO

2 eq), 1.52%W to an increase of 56.39% (+2.21 kg CO

2 eq) and 2.27%W to an increase of 84.54% (+3.32 kg CO

2 eq). These net increases may not be very high due to the size of the functional unit, with a volume of only 0.0032 m

3. However, extrapolating to 1 m

3 of mortar would result in very significant values. This is clearly presented in

Table A5, where the results are evaluated for 1 m

3 of mortar under the same biochar dosage conditions, but with an increased functional unit volume.

One of the strategies currently being used is to obtain the thermal energy in the carbonisation process from energy sources with lower environmental impact value where their respective CO2 eq emissions, for example, are lower. This is indeed the case, as at a larger, industrial production scale the associated energy consumptions for biochar production are not as high; otherwise, the process would be unfeasible not only from an environmental perspective but also economically. Industrial process optimisation, such as the introduction of heat recovery systems to improve efficiency, further reduces energy demand. To investigate this, a comparative study of CO2 eq emissions has been carried out based on different types of energy used to produce the biochar.

A practical example would be to compare the same amount of energy recorded in the carbonisation of biochar used in the research (see

Table 6) but using two different technologies. The first of these energies is a muffle furnace that consumes energy from the grid, and the second is the same muffle furnace, but this one obtains energy from the combustion of biomass and natural gas. For this simulation, the final energy GHG emission factors provided by the Institute for Energy Diversification and Saving (IDAE in Spanish) are used [

33] and their respective values are shown in

Table 8. As can be seen, using energy sources with lower environmental impact in the manufacture of biochar would bring about a lower environmental burden on biochar and the results obtained with a cradle-to-gate approach would be lower than those seen in

Figure 2.

The initial interpretation of Scenario I and its respective approach is that the addition of biochar as an additive in terms of mass percentage has a greater environmental impact than the reference mortar. However, although these results correspond to a productive scope, this does not imply that environmental assessments in later phases of use and maintenance do not show environmental advantages of this type of mortar with additives. Specifically, the environmental advantage of using waste from industrial or agricultural sectors is more visible in the medium to long term [

32]. This is justified because these mortars with bio-agricultural waste often have improved physical and mechanical properties, such as improved thermal conductivity (λ) reflecting a decrease of up to 67% [

11], which makes them more efficient when used as insulation in buildings. This results in improved energy efficiency and, consequently, a reduced environmental impact. Alternatively, there may be an improvement in mechanical performance, according to research by Barbhuiya et al. In the specific case of biochar, its high surface area and porosity increase water absorption and therefore the moisture content within the mixture, which promotes greater durability, reducing shrinkage during the setting process and improving the appearance of cracks at an early stage, as well as increasing mechanical strength [

10,

29].

In later stages of mortar use and application in a building, the carbon sequestered by the biochar mortar could also be taken into account, as it acts as a CO

2 capture and retention agent from the atmosphere in the chemical process of concrete and mortar carbonation. Where the alkaline compound calcium hydroxide Ca(OH)

2 combines with CO

2 present in the atmosphere to form calcium carbonate CaCO

3 plus water H

2O. Many studies confirm that carbon sequestration can be an interesting way of mitigating GHGs associated with the construction sector [

10,

11,

12]. Therefore, although Scenario I has shown that the environmental profitability of manufacturing mortar with biochar as an additive in weight percentage (%W) is not ideal from a cradle-to-gate perspective and for the production processes developed for biochar, this does not mean that it will be excluded from subsequent assessments. Even when applying more sustainable technology in the manufacture of biochar, more satisfactory results can be obtained.

3.3. Environmental Results—Scenario II

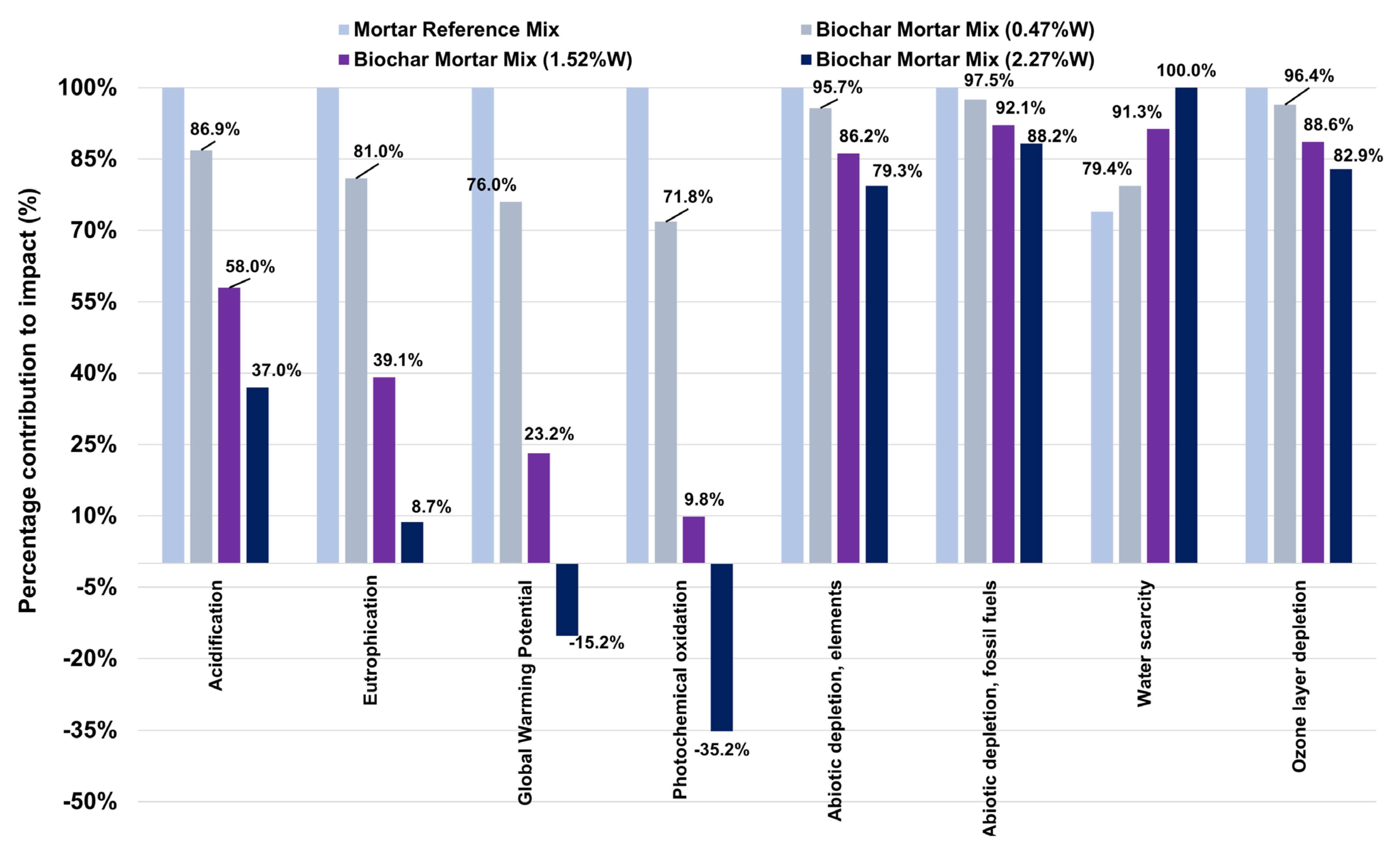

Figure 4 shows the environmental results of Scenario II (see

Table A4) and

Table A6 shows the respective extrapolation to 1 m

3 of mortar. The results for this scenario, compared with those obtained in Scenario I (see

Figure 3), show a notable change in trend. In general, and for all impact categories except Water Scarcity, the various mortar mix alternatives incorporating a percentage of biochar in %W generate lower environmental impacts compared with the reference mortar.

Following on from the explanation of the GWP impact category, the reference mix produces the highest impact value with a value of 0.58 kg CO

2 eq, whereas the mix with 0.47%W of biochar decreases by 24.01% (−0.14 kg CO

2 eq), the mix with 1.52%W decreases by 76.83% (−0.44 kg CO

2 eq) and finally, for the mix with 2.27%W, the decrease is 135.22% (−0.672 kg CO

2 eq), which means that for this alternative, the impact indicator is negative with a value of −0.089 kg CO

2 eq. Based on this initial observation, it is clear in Scenario II that accounting for biochar removals and environmental loads due to avoided processes and products gives the LCA results an environmental advantage when biochar is incorporated into mortar. This effect is consistent with current literature, for example, the research by Ee et al., where they evaluate a scenario of including biogenic CO

2 eq in concrete, where they add biochar together with fly ash, partially replacing OPC. The results of their LCA for the inclusion of biochar imply significant differences for 1 m

3 of concrete (f

ck = 30 MPa), specifically from 239 kg CO

2 eq to values of around 96 kg CO

2 eq [

20]. Also, research by Rylko et al. associates a CO

2 eq emissions credit to the use of biochar of −1.0 kg CO

2 eq/kg biochar [

34]. These situations considerably improve the LCA results, as also observed in the research by Wu et al., where replacing 5% of the amount of cement with biochar reduces CO

2 eq emissions by 20.7% [

35], as well as in the study by Shahmansouri et al., in which the use of up to 30% biochar as a cement replacement reduces CO

2 eq by 76% [

36].

Apart from the GWP impact category, other impact categories such as photochemical oxidation (−135.22%), ozone depletion (−17.07%), acidification (−63.01%) and eutrophication (−91.3%) show a reduction in their respective environmental impacts. These impact categories are limited as a result of modelling the combustion process of pellets in a biomass boiler to obtain thermal energy. Combustion processes generate various gases such as CO2 and NOx, as well as emissions of suspended particles and the creation of waste such as ash. Also, the pellet generation process, in its respective biomass densification process, the compacting machines’ main source of supply is electrical energy; therefore, their impacts directly affect the previously mentioned impact categories, as well as Fossil Fuel Depletion (−11.76%). Consequently, by modelling the avoidance of these effects, the environmental impacts of these impact categories are significantly reduced.

The only increase in the comparison is in the Water Scarcity impact category, where for mixes with a higher biochar content 2.27%W, the increase is 26.06% (+0.08 m3 of water), which is justified because as the mass content of vegetable carbon increases, the amount of electrical energy associated with this manufacturing process increases and, indirectly, the consumption of water used in the generation of electrical energy based on existing technologies.

Figure 5 shows the contribution of environmental impacts as a function of material for the alternative of a mixture with 0.47%W of biochar. As can be seen for Scenario II, the results for cement and fine aggregate are very similar to those in

Figure 2, with the exception of biochar. This clearly shows that in almost all impact categories, its percentage contribution is negative, with an average decrease of −10.18%, which implies that environmental impacts on the functional unit are being reduced.

Ultimately, in Scenario II, it is clear that the inclusion of biogenic removals in the LCA, as well as the justified modelling of avoided products and processes and, consequently, avoided environmental credits, give Scenario II very different results from those obtained in Scenario I.

In short, future lines of research arising from the current one can be divided into two situations. The first, based on Scenario I, where the use of biochar as an additive in %W by mass generates greater environmental loads, then resorts to the opposite situation, i.e., using it as a partial replacement for cement by mass. Research such as that conducted by Patel et al. found that a 2% substitution rate can increase compressive strength by around 18.95% [

10]. It could be added and assumed that, apart from using less cement in the mix, this avoids the process of creating this material. Another line of research would be to quantify, in the early stages of setting and use of these biochar-based mortars and concretes, the net amount of CO

2 eq sequestration and removal that occurs over a long period of use as a result of the carbonation process and to include this in the LCA study [

37].

3.4. LCA Sensitivity Analysis

After explaining the results obtained in the study, it was decided to determine the level of uncertainty associated with these results. To this end, a sensitivity analysis was carried out on the various outcomes for Scenario I and Scenario II.

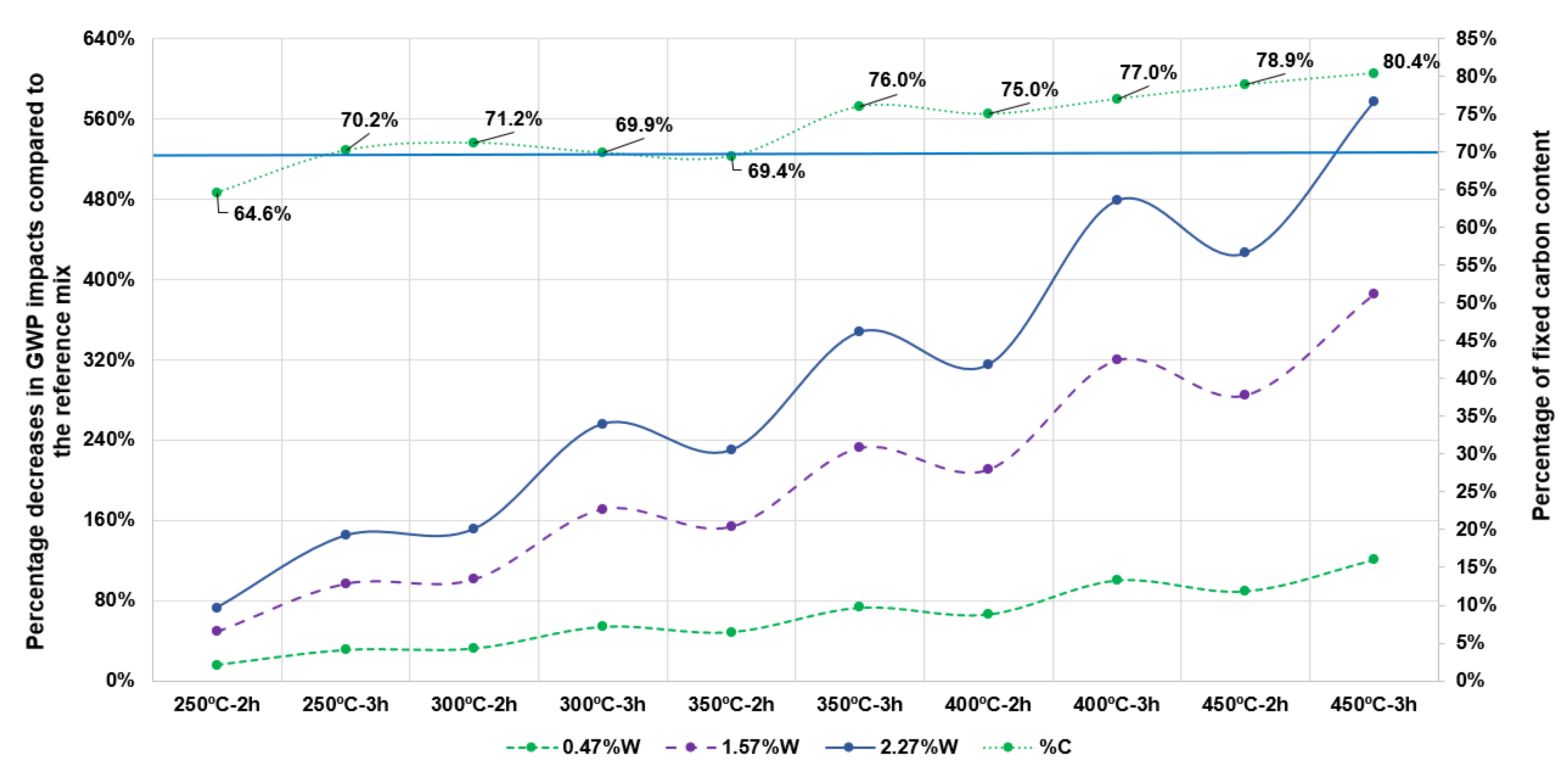

First, the analysis focuses exclusively on the GWP impact category, examining the variations obtained in Scenario I when using the different types of biochar produced. These types of biochar differ in several parameters, including energy consumption, yield and, consequently, the percentage of fixed carbon content (see

Table A1). The corresponding environmental results are illustrated in

Figure 6.

As shown, the left y-axis represents the percentage increase in CO2-eq emissions relative to the reference mix, i.e., the alternative in which no biochar is used. The right y-axis corresponds to the fixed carbon content (%C) of each type of biochar. All modelled scenarios were calculated under the assumption that electricity is the energy source used for the carbonisation process.

It is evident that biochar production conditions involving higher carbonisation temperatures and longer residence times lead to greater percentage increases in impacts. This effect becomes less pronounced at lower dosage levels; for instance, when comparing the 2.27%W and 0.47%W dosages, the difference is substantial. Specifically, using 0.47%W of a high-quality biochar with a fixed carbon content of 80.4%C results in a 120.75% increase in GWP, whereas the same biochar at 2.27%W leads to a 577.06% increase. This biochar—characterised by its high fixed carbon content—was selected for the study due to its potential to enhance the properties of the mortar.

As a result of this sensitivity analysis, a key conclusion can be drawn: if the quality of the biochar incorporated into the mortar is limited to an intermediate range—for example, around 70% fixed carbon content (%C), which still represents a biochar of acceptable quality and applicability—a region can be identified in

Figure 6 where the percentage increases in environmental impacts are not as pronounced relative to the reference mix.

For instance, under carbonisation conditions of 300–350 °C for 2–3 h and at lower dosage levels such as 0.47%W, the increases in GWP range from 32.06% to 72.99%. These values are relatively manageable and could be further reduced by using more sustainable energy sources, as shown in

Section 3.2, or through industrial-scale production where process efficiencies are typically higher.

The second sensitivity analysis corresponds to the environmental results of the LCA for Scenario II. The rationale for this analysis is that the avoided/substituted products defined in Scenario II are not the only possible treatment option for vine pruning residues, as explained in

Section 2.4. Therefore, it was decided to assess whether there is an environmental benefit in using biochar in mortars under a scenario in which the vine pruning residues are prevented from being openly burned on-site at a winery. For the simulation and quantification of the avoided environmental credits, the process specified in

Table 5 was selected. Additionally, within this first sensitivity analysis, the importance of including or excluding the accounting of CO

2 removals associated with biochar use (see

Section 2.4) was also studied, with the aim of understanding, under Scenario II, the main source of environmental benefit for the GWP category. These results are presented in

Figure 7.

As can be observed, for each biochar dosage in the mortar mix, four distinct results are obtained. The upper results correspond to calculations where the carbon retained in the biochar itself (quantified in

Section 2.4) is not included, whereas the two lower lines include it. Firstly, if we compare the two modelling approaches for the avoided products—namely, the production of densified biomass (pellets) and their subsequent combustion for heat generation, versus open field burning—the GWP impact category shows a slight environmental benefit for the first alternative of avoided products. For instance, for a 2.27%W biochar dosage, compared to the reference mix, the CO

2 eq emission reductions are −2.7% for the pellets + thermal energy scenario, and only −0.7% for open field burning, which is a practically negligible difference. This is explained by the fact that pellet production involves unit processes with energy consumption from the grid, which increases its environmental impact value. One conclusion drawn is that the modelling of the avoided products associated with biochar derived from vine pruning residues is not of critical importance for the GWP impact category and its corresponding environmental benefit. Furthermore, it should be noted that these modelling approaches cover the vast majority of alternatives for the use, treatment, disposal, or valorisation of vine pruning residues.

On the other hand, if we consider whether to include the carbon sequestered in the biochar in the calculation, the conclusions differ. The main advantage in the GWP impact category is directly attributed to these CO2 eq removals. For example, for a 2.27%W biochar dosage in mortars, the GWP reduction is −115.2% compared to the reference mix, in contrast to the previously mentioned reduction of −2.7%.

In conclusion, for this study, the inclusion of biogenic carbon in the biochar is essential for determining its environmental benefit under Scenario II and for the GWP category. The results of the sensitivity analysis for the GWP category are presented, while the differences for the remaining environmental impact categories are shown in

Figure 8.

For the remaining impact categories, the situation changes substantially in the sensitivity analysis. For example, impact categories such as acidification (−11%; −63.01%), eutrophication (−56.15%; −91.30%), GWP (−112.6%; −115.25%) and photochemical oxidation (−157.54%; −135.22%), both avoided product alternatives result in reductions in environmental impacts, with slightly greater reductions observed when the avoided products are densified biomass (pellets) and their combustion for heat generation, compared to open-field burning. This indicates that, for these impact categories, both modelling approaches are positive.

Conversely, impact categories such as abiotic depletion elements (+56.30%; −20.69%), abiotic depletion fossil fuels (+39.83%; −11.76%), water scarcity (+39.62%; +26.06%) and ozone layer depletion (+39.38%; −17.07%) show significant differences between the two modelling approaches. For instance, open field burning of vine pruning residues in these categories results in percentage increases in environmental impacts compared to the reference mix, translating into higher environmental impact values.

The rationale is that, when analysing the unit process of biochar production, open-field burning does not contribute environmental impacts to these categories; the increases are solely due to electricity consumption in the muffle furnace. In contrast, the other avoided product alternative generates negative environmental impacts compared to the reference mix.

3.5. Economic Analysis of Mortar with Biochar

After discussing and explaining the environmental results, a fundamental aspect that significantly affects the decision to start using biochar as an additive has been left out of the research, namely the economic criteria. Therefore, this section aims to quantify in monetary value (unit of measurement in euros, EUR) the economic cost of manufacturing these mortars with biochar.

However, it should be noted that the price per functional unit (volume of mortar of 0.003 m

3) is not very representative or significant in terms of magnitude, so it was decided to extrapolate the economic results to 1 m

3 of mortar, along with the corresponding environmental impacts, as shown in

Table A5. To calculate the unit prices of the materials, we refer to the research by Los Santos-Ortega et al. [

38], which establishes a price of EUR 103/t for cement, EUR 9.5/t for fine aggregates and EUR 2/m

3 for water. The price of biochar varies greatly depending on its previous production process and the origin of the biomass; however, over time, its economic value has fallen significantly [

39].

Compared to the price of cement, biochar is considerably more expensive, reflecting market conditions and the current real-world applications of biochar [

10]. For this research, biochar from pruning waste has been chosen at an average price of EUR 4/kg according to a national market survey. The other economic cost to consider is electricity consumption during mixing operations. Mel Fraga et al. estimate that the process of mixlying 1 m

3 of concrete consumes 1.61 kWh [

30], which means that if the average price per kWh is EUR 0.14, the economic cost associated with mixing the concrete is EUR 0.23/m

3.

Table 9 shows the quantities of materials for 1 m

3 of mortar and their unit prices.

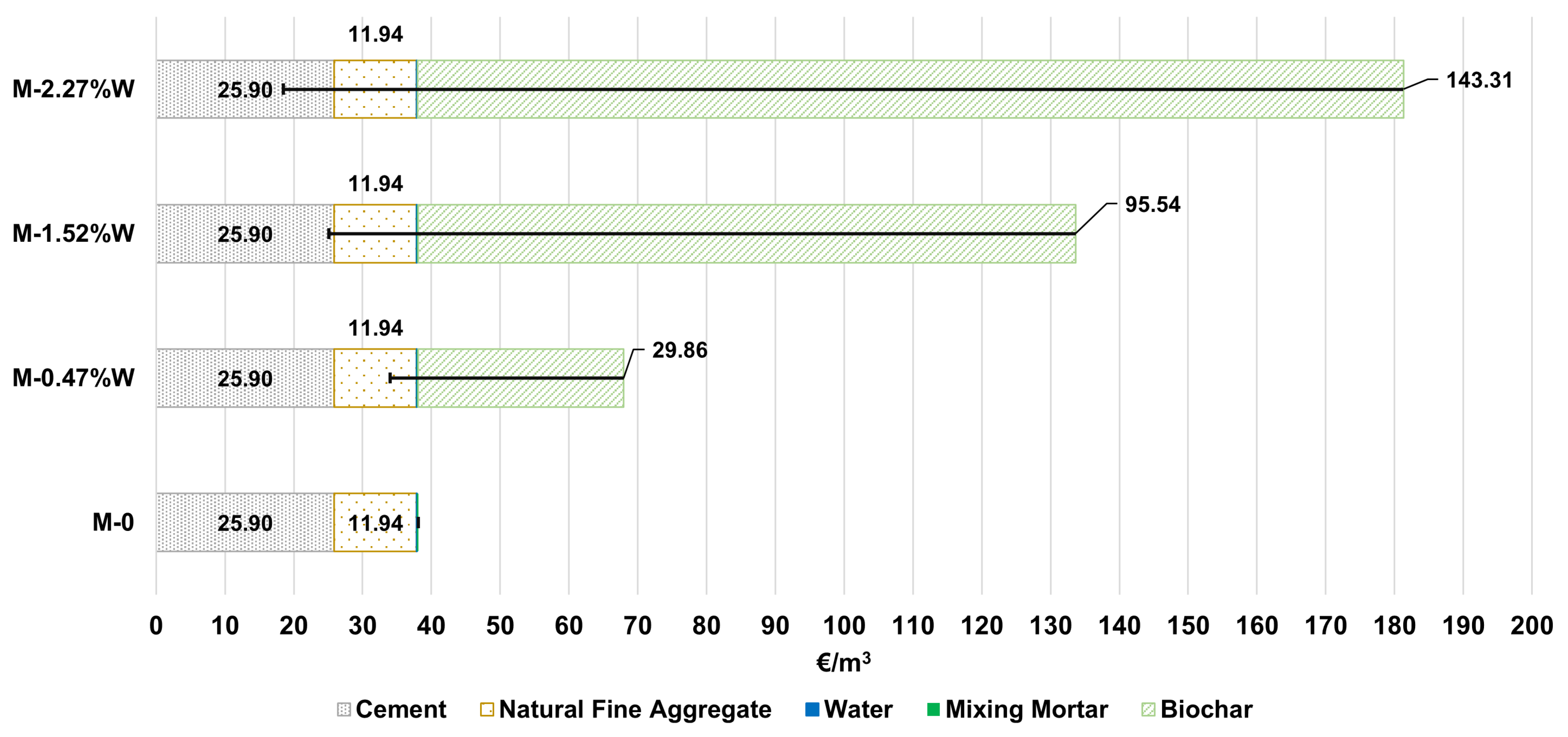

Figure 9 shows the resulting economic cost (EUR/m

3) in cumulative form for the various mixes (1 m

3).

The main results extracted from

Figure 9 show that, in 1 m

3 of mortar without biochar addition, the main economic cost per m

3 is associated with cement, where with the dosages proposed in the research for cement (251.42 kg/m

3), its respective cost accounts for 67.97% of the m

3. Logically, with higher quantities of cement, its cost will increase considerably. On the other hand, the price of aggregates (1257 kg/m

3) represents 31.33% of the economic cost. If both above materials are calculated, a total of 99.3% is established, with only 0.7% associated with the cost of mixing the mixture and the price of water use. These results remain constant as the quantities do not vary for the rest of the alternatives evaluated (0.47%W, 1.52%W, 2.27%W).

On the other hand, the incorporation of biochar as an additive linearly increases the monetary value, justified because its unit price is EUR 4/kg. As a result of increasing the percentage contribution by mass (%W) of the biochar additive, the price per m3 of mortar will increase. In the 2.27%W alternative, biochar has a cost of EUR 143.31/kg, which gives it a representative percentage of 79.05%, displacing cement to a percentage of 14.29% and fine aggregate to 6.6%. In short, this alternative is 375.86% more expensive than the reference mortar, rising from EUR 38.1/m3 to EUR 181.3/m3. This economic study is a partial cost analysis studying only the production stage (materials and energy) and is not a complete life cycle cost assessment of the biochar mortar.

Furthermore, it should be noted that biochar prices can fluctuate. In this study, the price analysed was for biochar sold to tertiary consumers, although prices may be lower than EUR 4/kg if supplied in large production volumes or in bulk. Despite this, it has been shown that adding biochar to mortar from cradle to gate reflects a substantial increase in economic prices, all within the scope of production. It is worth noting again that, if the use of these mortars results in mechanical and thermal advantages, it would be interesting to compare the economic savings that may exist in this situation with those of a reference mortar, which could offset economic profitability. Price limitations imposed by governments would also result in a strategy that promotes the use of this biochar in construction materials, as well as economic carbon removal programmes.

As an illustrative example, a simple quantification of the potential economic incentive for mortars containing biochar is presented, assuming payments for CO

2 eq retention and sequestration were available. For this purpose, the average annual price of CO

2 eq emission allowances for 2025 is used, considering this cost as the benefit obtained by avoiding emissions and sequestering CO

2 eq. The 2025 average price is EUR 72.83/tCO

2 eq [

40]. Based on the CO

2 eq retention values associated with biochar (see

Section 2.4) and the amounts of biochar per m

3 of mortar (see

Table 9), the following reductions would be applied to the prices shown in

Figure 9: 0.47%W (EUR −11.91/m

3), 1.57%W (EUR −38.12/m

3), and 2.27%W (EUR −57.18/m

3). Additionally, for this economic sensitivity analysis, the biochar supply price is assumed to decrease to EUR 1/kg. The results are presented as error bars in

Figure 9. As can be seen, the economic reductions are significant, and in some cases, the costs even fall below that of the reference mortar mix. This demonstrates that, although the production cost of mortar containing biochar is higher during the manufacturing phase, there are potential mechanisms to mitigate the economic cost, with additional reductions possible in later life cycle stages.