Photodynamic Microbial Defense of Cotton Fabric with 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled PAMAM Dendrimer

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

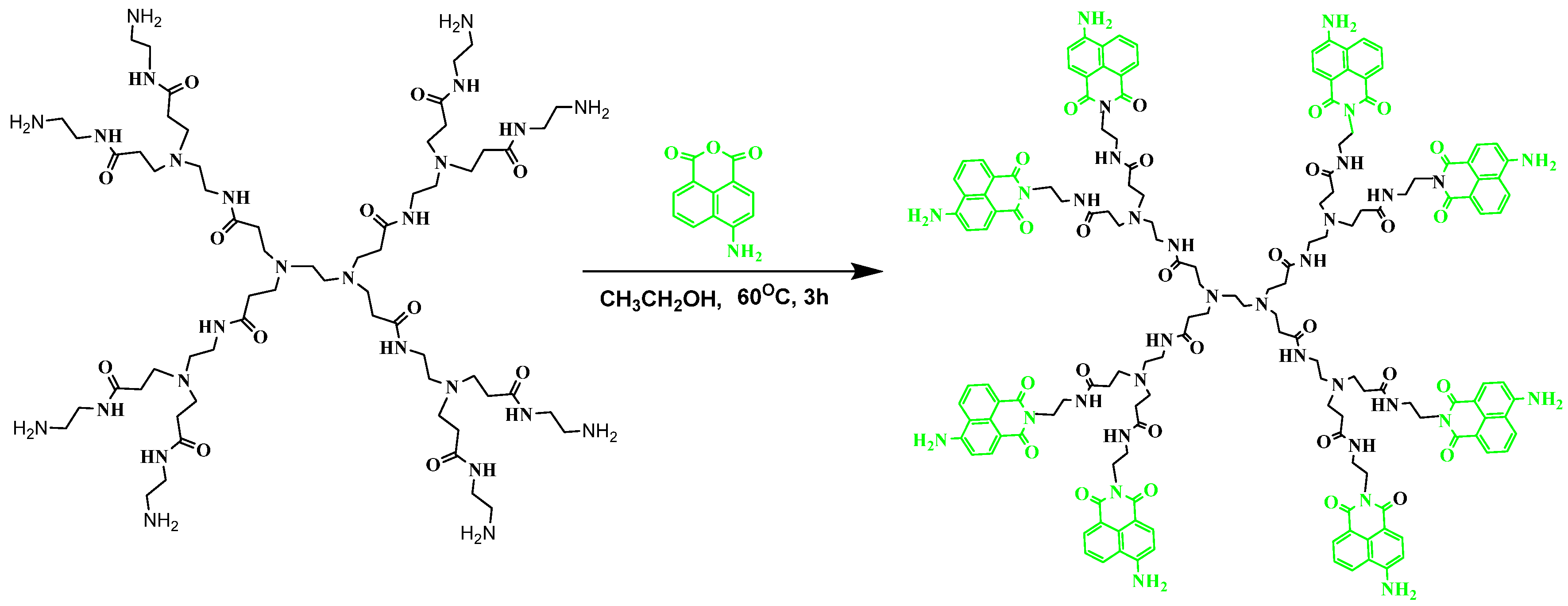

Synthesis of 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled Poly(Amidoamine) Dendrimer (DA)

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis of Fluorescent Dendrimer DA

3.2. FTIR Spectral Characterization

3.3. SEM Analysis of 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalic Anhydride and Dendrimer DA

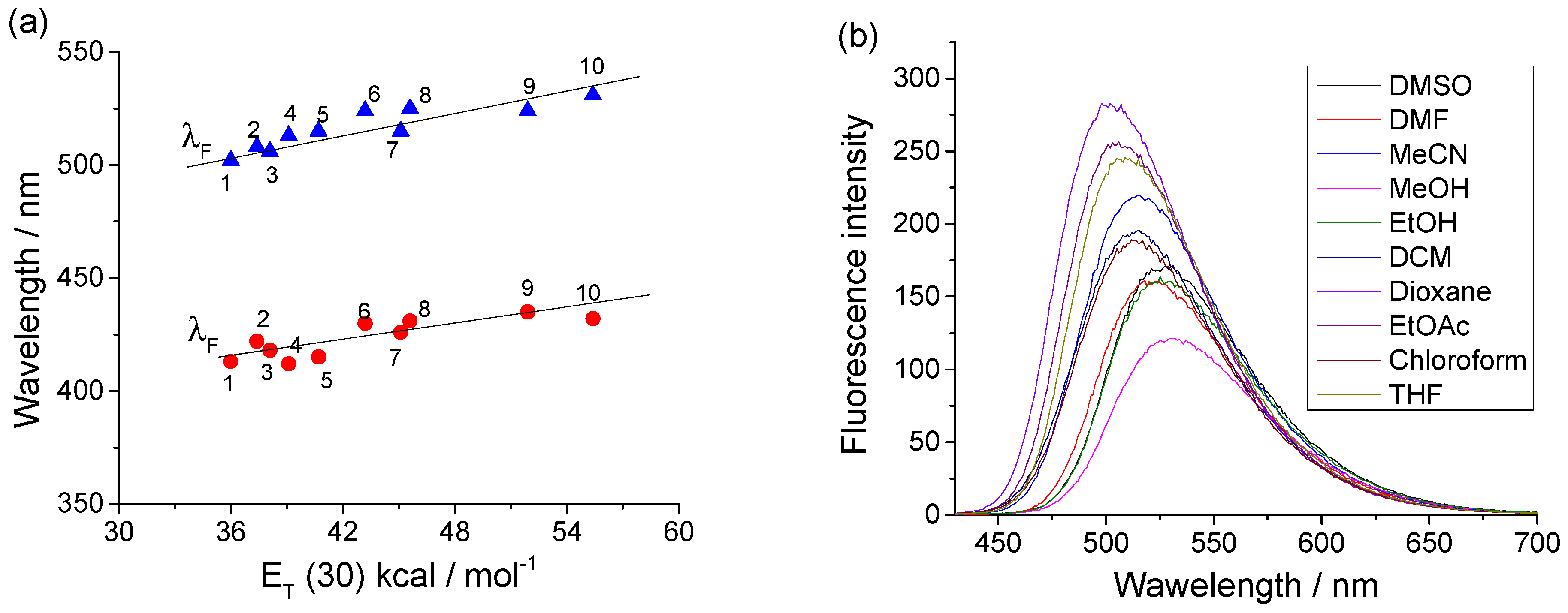

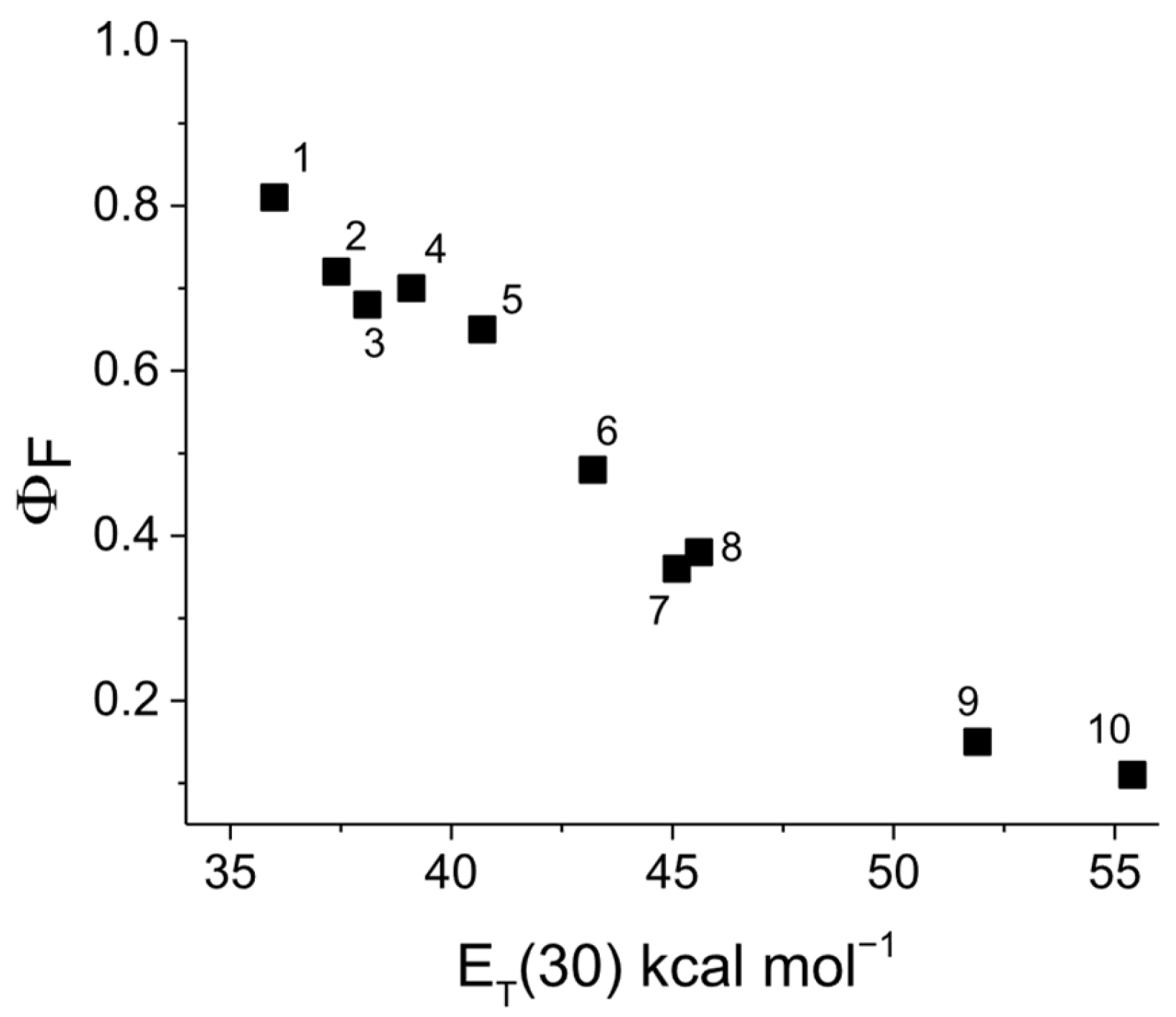

3.4. Photophysical Characteristics of the Dendrimer DA

3.5. Treatment of Cotton Fabrics with Dendrimer DA

3.6. Hydrophilicity of Cotton Fabrics

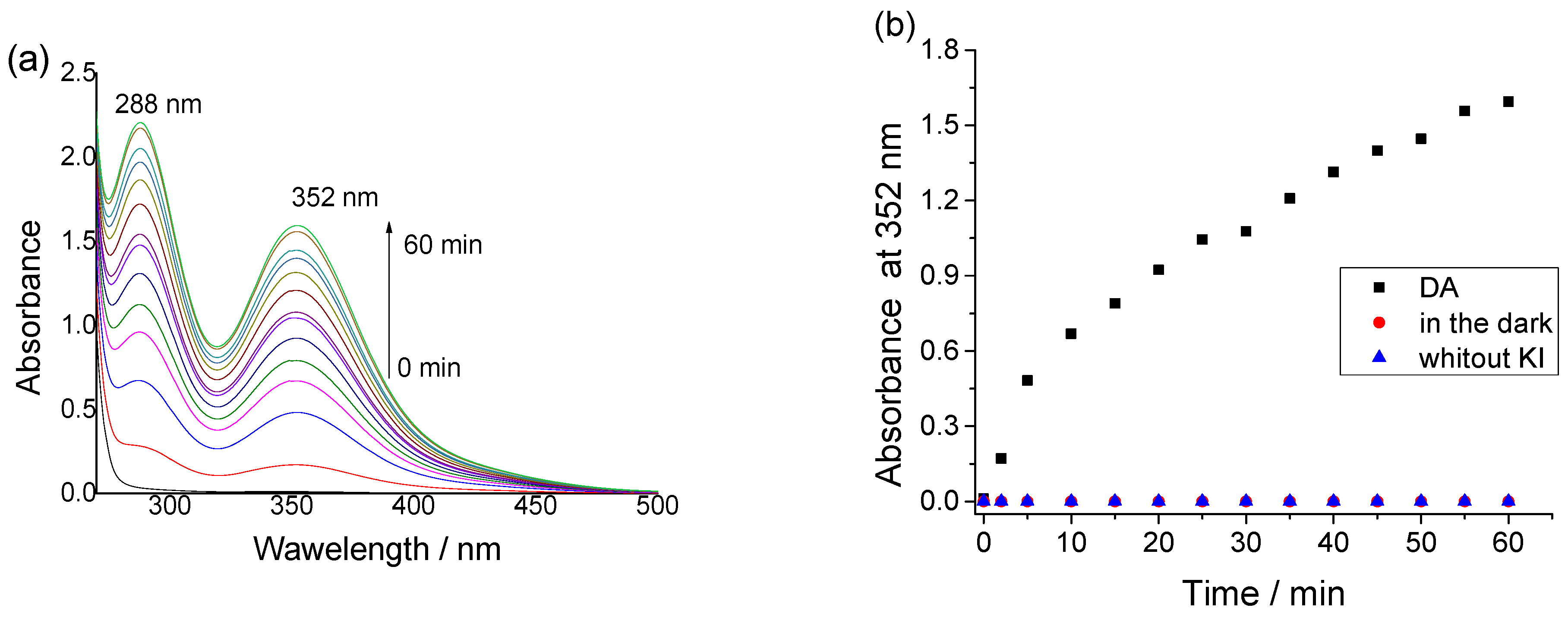

3.7. Reactive Oxygen Species (1O2) Generated from Dendrimer DA and Treated Cotton Fabric with It

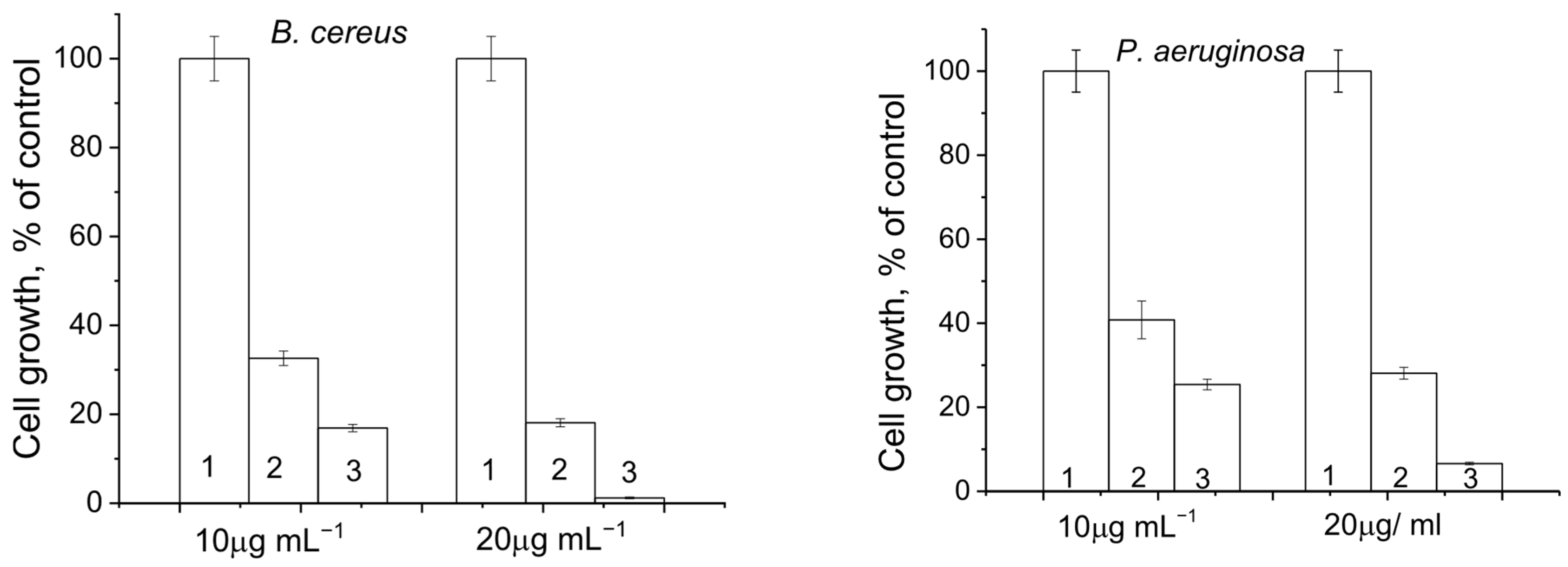

3.8. Antimicrobial Effect of Dendrimer DA and Cotton Fabrics DA15 and DA30

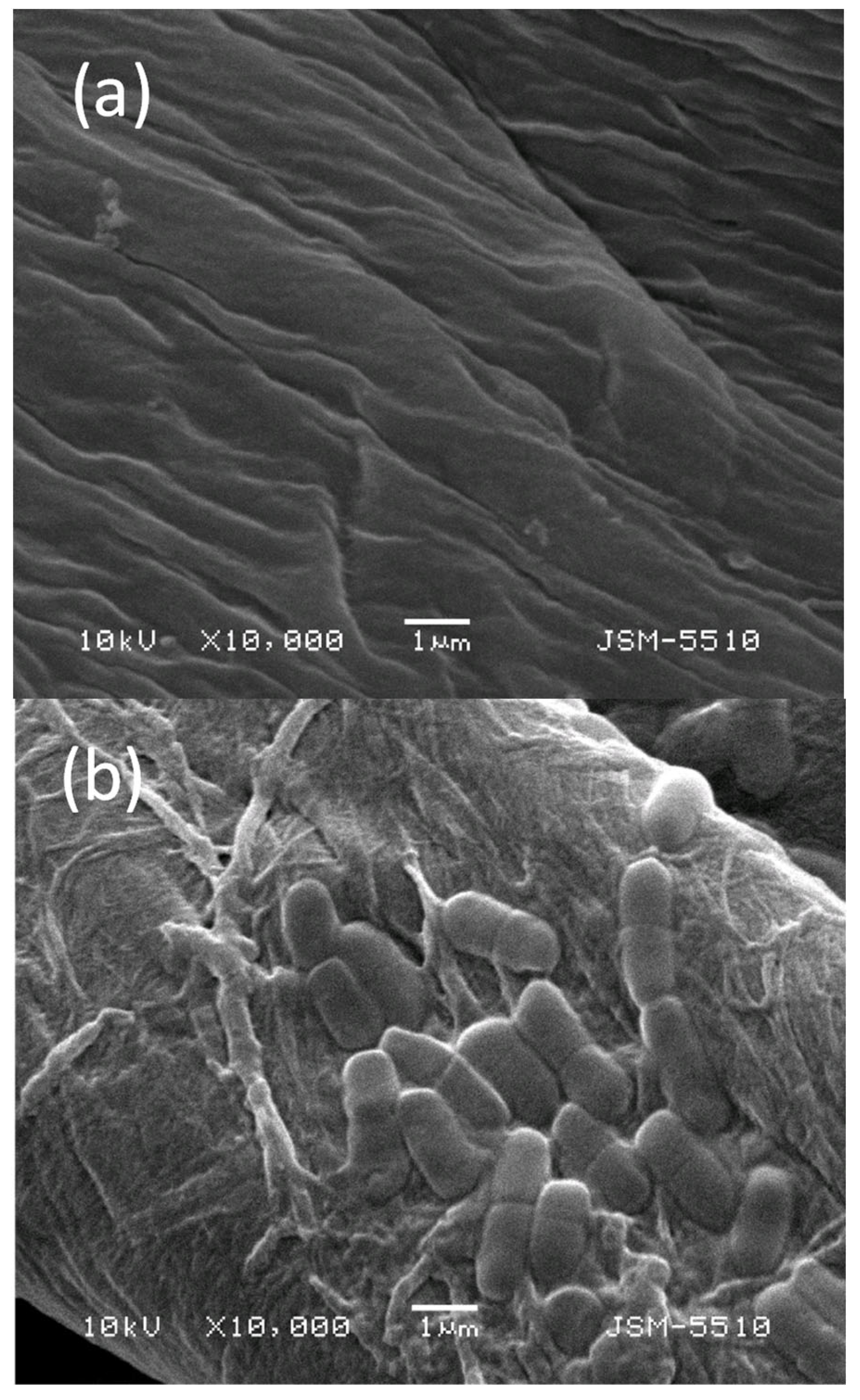

3.9. SEM Investigation of Cotton Fabrics

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sanders, D.; Grunden, A.; Dunn, R.R. A review of clothing microbiology: The history of clothing and the role of microbes in textiles. Biol. Lett. 2021, 17, 20200700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vojnits, K.; Mohseni, M.; Parvinzadeh Gashti, M.; Nadaraja, A.V.; Karimianghadim, R.; Crowther, B.; Field, B.; Golovin, K.; Pakpour, S. Advancing Antimicrobial Textiles: A Comprehensive Study on Combating ESKAPE Pathogens and Ensuring User Safety. Materials 2024, 17, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, R.; Sharma, S.; Sharma, R.K. Antimicrobial textile: Recent developments and functional perspective. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5747–5771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, L.E.; Gomez, E.D.; Solis, J.L.; Gomez, M.M. Antibacterial Cotton Fabric Functionalized with Copper Oxide Nanoparticles. Molecules 2020, 25, 5802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, D.; Atanasova, D.; Nenova, A.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grabchev, I. Cotton Fabric Modified with a PAMAM Dendrimer with Encapsulated Copper Nanoparticles: Antimicrobial Activity. Materials 2021, 14, 7832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehravani, B.; Ribeiro, A.I.; Zille, A. Gold Nanoparticles Synthesis and Antimicrobial Effect on Fibrous Materials. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- del Olmo, N.S.; Carloni, R.; Ortega, P.; García-Gallego, S.; de la Mata, F.J. Metallodendrimers as a promising tool in the biomedical field: An overview. Adv. Organomet. Chem. 2020, 74, 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mahltig, B.; Tatlises, B.; Fahmi, A.; Haase, H.J. Dendrimer stabilized silver particles for the antimicrobial finishing of textiles. J. Text. Inst. 2013, 104, 1042–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, Y.; Niu, L.N.; Ma, S.; Li, J.; Tay, F.R.; Chen, J.H. Quaternary ammonium-based biomedical materials: State-of-the-art, toxicological aspects and antimicrobial resistance. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2017, 71, 53–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, M.C.; Minbiole, K.P.; Wuest, W.M. Quaternary Ammonium Compounds: An Antimicrobial Mainstay and Platform for Innovation to Address Bacterial Resistance. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 288–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.S.; Chirila, L.; Popescu, A.; Radulescu, D.M.; Radulescu, D.E.; Dinischiotu, A. Essential Oil Microcapsules Immobilized on Textiles and Certain Induced Effects. Materials 2019, 12, 2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Tarabily, K.A.; El-Saadony, M.T.; Alagawany, M.; Arif, M.; Batiha, G.E.; Khafaga, A.F.; Elwan, H.A.M.; Elnesr, S.S.; El-Hack, M.E.A. Using essential oils to overcome bacterial biofilm formation and their antimicrobial resistance. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5145–5156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falanga, A.; Del Genio, V.; Galdiero, S. Peptides and Dendrimers: How to Combat Viral and Bacterial Infections. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čuk, N.; Simončič, B.; Fink, R.; Tomšič, B. Bacterial Adhesion to Natural and Synthetic Fibre-Forming Polymers: Influence of Material Properties. Polymers 2024, 16, 2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staneva, D.; Said, A.I.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grabchev, I. Enhanced Photodynamic Efficacy Using 1,8-Naphthalimides: Potential Application in Antibacterial Photodynamic Therapy. Molecules 2022, 27, 5743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staneva, D.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grabchev, I. Chemical Modification of Cotton Fabric with 1,8-Naphthalimide for Use as Heterogeneous Sensor and Antibacterial Textile. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2019, 382, 111924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Liu, C.; Su, M.; Rong, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, K.; Li, X.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Recent advances in 4-hydroxy-1,8-naphthalimide-based small-molecule fluorescent probes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 448, 214153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Cao, J.; Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, M.; Gu, S. Research Progress of Fluorescent Probes for Detection of Glutathione (GSH): Fluorophore, Photophysical Properties, Biological Applications. Molecules 2024, 29, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.H.; Addla, D.; Lv, J.S.; Zhou, C.H. Heterocyclic naphthalimides as new skeleton structure of compounds with increasingly expanding relational medicinal applications. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 3303–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, W.; Xie, Z.; Wang, Y.; Xia, L.; Guo, Y.; Qiao, D. An Overview of Naphthylimide as Specific Scaffold for New Drug Discovery. Molecules 2024, 29, 4529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alsaeedi, H.; Alabdullah, I.; Alsalme, A.; Khan, R.A. Synthesis of 4-Chloro-1,8-Naphthalimide analogs: DNA binding, molecular docking, and in vitro cytotoxicity. J. Mol. Struct. 2026, 1352, 144527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, D.; Grabchev, I. Chapter 20, Dendrimer as antimicrobial agents. In Dendrimer-Based Nanotherapeutics; Kesharwani, P., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 363–384. ISBN 978-0-12-821250-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Gao, Y.; Dang, K.; Guo, X.; Ding, A. Naphthalimide-modified dendrimers as efficient and low cytotoxic nucleic acid delivery vectors. Polym. Int. 2021, 70, 1590–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabchev, I.; Angelova, S.; Staneva, D. Yellow-Green and Blue Fluorescent 1,8-Naphthalimide-Based Chemosensors for Metal Cations. Inorganics 2023, 11, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.I.; Staneva, D.; Grabchev, I. New Water-Soluble Poly(propylene imine) Dendrimer Modified with 4-Sulfo-1,8-naphthalimide Units: Sensing Properties and Logic Gates Mimicking. Sensors 2023, 23, 5268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.I.; Staneva, D.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grozdanov, P.; Nikolova, I.; Stoyanova, R.; Jordanova, A.; Grabchev, I. Synthesis, Spectral Characteristics, Sensing Properties and Microbiological Activity of New Water-Soluble 4-Sulfo-1,8-naphthalimides. Chemosensors 2024, 12, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cangiotti, M.; Staneva, D.; Ottaviani, M.F.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grabchev, I. Synthesis and characterization of fluorescent PAMAM dendrimer modified with 1,8-naphthalimide units and its Cu(II) complex designed for specific biomedical application. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 415, 113312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi-Kiakhani, M.; Safapour, S. Functionalization of poly(amidoamine) dendrimer-based nano-architectures using a naphthalimide derivative and their fluorescent, dyeing and antimicrobial properties on wool fibers. Luminescence 2016, 31, 1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordanova, A.; Tsanova, A.; Stoimenova, E.; Minkov, I.; Kostadinova, A.; Hazarosova, R.; Angelova, R.; Antonova, K.; Vitkova, V.; Staneva, G.; et al. Molecular Mechanisms of Action of Dendrimers with Antibacterial Activities on Model Lipid Membranes. Polymers 2025, 17, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; ISBN 978-92-4-009346.

- Gauba, A.; Rahman, K.M. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms in Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Khusro, A.; Zidan, B.M.R.M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Koirala, N. Antibiotic resistance in microbes: History, mechanisms, therapeutic strategies and prospects. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caivano, G.; Sciarra, F.M.; Messina, P.; Cumbo, E.M.; Caradonna, L.; Di Vita, E.; Nigliaccio, S.; Fontana, D.A.; Scardina, A.; Scardina, G.A. Antimicrobial Resistance and Causal Relationship: A Complex Approach Between Medicine and Dentistry. Medicina 2025, 61, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coque, T.M.; Cantón, R.; Pérez-Cobas, A.E.; Fernández-de-Bobadilla, M.D.; Baquero, F. Antimicrobial Resistance in the Global Health Network, Known Unknowns and Challenges for Efficient Responses in the 21st Century. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Almotiri, A.; AlZeyadi, Z.A. Antimicrobial Resistance and Its Drivers—A Review. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niño-Vega, G.A.; Ortiz-Ramírez, J.A.; López-Romero, E. Novel Antibacterial Approaches and Therapeutic Strategies. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, M.A.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A.A. Antimicrobial Resistance, A Growing Serious Threat for Global Public Health. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüssow, H. The Antibiotic Resistance Crisis and the Development of New Antibiotics. Microb. Biotechnol. 2024, 17, e14510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, N.S.; Mythili, R.; Cherian, T.; Dineshkumar, R.; Sivaraman, G.K.; Jayakumar, R.; Prathaban, M.; Duraimurugan, M.; Chandrasekar, V.; Peijnenburg, W.J.G.M. Overview of antimicrobial resistance and mechanisms: The relative status of the past and current. Microbe 2024, 3, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Sahu, A.; Mukherjee, T.; Mohanty, S.; Das, P.; Nayak, N.; Kumari, S.; Singh, R.P.; Pattnaik, A. Divulging the potency of naturally derived photosensitizers in green PDT: An inclusive review of mechanisms, advantages, and future prospects. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2025, 24, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delcanale, P.; Abbruzzetti, S.; Viappiani, C. Photodynamic treatment of pathogens. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 2022, 45, 407–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surur, A.K.; Barros de Oliveira, A.; De Annunzio, S.R.; Ferrisse, T.M.; Fontana, C.R. Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial photodynamic therapy: A critical update. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2024, 255, 112905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amendola, G.; Di Luca, M.; Sgarbossa, A. Natural Biomolecules and Light: Antimicrobial Photodynamic Strategies in the Fight Against Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polat, E.; Kang, K. Natural Photosensitizers in Antimicrobial Photodynamic Therapy. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aires-Fernandes, M.; Botelho Costa, R.; Rochetti do Amaral, S.; Mussagy, C.U.; Santos-Ebinuma, V.C.; Primo, F.L. Development of Biotechnological Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy: Cancer Research and Treatment—From Benchtop to Clinical Practice. Molecules 2022, 27, 6848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Correia, J.H.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Pimenta, S.; Dong, T.; Yang, Z. Photodynamic Therapy Review: Principles, Photosensitizers, Applications, and Future Directions. Pharmaceutics 2021, 13, 1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sai, D.L.; Lee, J.; Nguyen, D.L.; Kim, Y.P. Tailoring photosensitive ROS for advanced photodynamic therapy. Exp. Mol. Med. 2021, 53, 495–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.Y.; Libardo, M.D.J.; Angeles-Boza, A.M.; Pellois, J.P. Membrane Oxidation in Cell Delivery and Cell Killing Applications. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, D.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grozdanov, P.; Vilhelmova-Ilieva, N.; Nikolova, I.; Grabchev, I. Synthesis and photophysical characterisation of 3-bromo-4-dimethylamino-1,8-naphthalimides and their evaluation as agents for antibacterial photodynamic therapy. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 401, 112730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manov, H.; Staneva, D.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Grozdanov, P.; Nikolova, I.; Stoyanov, S.; Grabchev, I. Photosensitive dendrimers as a good alternative to antimicrobial photodynamic therapy of Gram-negative bacteria. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2021, 419, 113480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabchev, I.; Jordanova, A.; Vasileva-Tonkova, E.; Minkov, I.L. Sensing and Microbiological Activity of a New Blue Fluorescence Polyamidoamine Dendrimer Modified with 1,8-Naphthalimide Units. Molecules 2024, 29, 1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.-L.; Pan, Q.-J.; Ma, D.-X.; Zhong, Y.-W. Naphthalimide-Modified Tridentate Platinum(II) Complexes: Synthesis, Characterization, and Application in Singlet Oxygen Generation. Inorganics 2023, 11, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magri, D.C.; Johnson, A.D. Naphthalimide–organometallic hybrids as multi-targeted anticancer and luminescent cellular imaging agents. RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 4657–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Yang, Y.; Qian, X. Recent progress on the development of thioxo-naphthalimides. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2020, 31, 2877–2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneva, D.; Angelova, S.; Grabchev, I. Spectral Characteristics and Sensor Ability of a New 1,8-Naphthalimide and Its Copolymer with Styrene. Sensors 2020, 20, 3501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orasugh, J.T.; Temane, L.T.; Pillai, S.K.; Ray, S.S. Advancements in Antimicrobial Textiles: Fabrication, Mechanisms of Action, and Applications. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 12772–12816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaideki, K.; Jayakumar, S.; Rajendran, R.; Thilagavathi, G. Investigation on the effect of RF plasma and neem leaf extract treatment on the surface modification and antimicrobial activity of cotton fabric. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2008, 254, 2472–2478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosinger, J.; Mosinger, B. Photodynamic sensitizers assay: Rapid and sensitive iodometric measurement. Experientia 1995, 51, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, L.; Yiming, X. Iodine-sensitized oxidation of ferrous ions under UV and visible light: The influencing factors and reaction mechanism. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2013, 12, 2084–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, J.; Nuss, A.M.; Berghoff, B.A.; Klug, G. Singlet Oxygen Stress in Microorganisms. Adv. Microb. Physiol. 2011, 58, 141–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maisch, T.; Baier, J.; Franz, B.; Maier, M.; Landthaler, M.; Szeimies, R.M.; Bäumler, W. The role of singlet oxygen and oxygen concentration in photodynamic inactivation of bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 7223–7228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Solvents | λA (nm) | λF (nm) | νA–νF (cm−1) | ε (L mol−1 cm−1) | ΦF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimetyl sulfoxide | 431 | 525 | 3996 | 81,950 | 0.36 |

| N,N-dimnethylformamide | 430 | 524 | 4008 | 87,010 | 0.38 |

| Acetonitrile | 426 | 515 | 4563 | 88,720 | 0.36 |

| Methanol | 432 | 531 | 4316 | 86,740 | 0.15 |

| Ethanol | 435 | 524 | 3905 | 86,330 | 0.11 |

| Dichloromethane | 415 | 515 | 4973 | 93,500 | 0.65 |

| Dioxane | 413 | 502 | 4293 | 81,080 | 0.81 |

| Ethyl acetate | 418 | 506 | 4161 | 84,060 | 0.40 |

| Chloroform | 412 | 513 | 4779 | 81,680 | 0.70 |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 422 | 508 | 4012 | 79,780 | 0.72 |

| Sample | L* | a* | b* | ΔL* | Δa* | Δb* | ΔE* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine cotton | 84.70 | −0.10 | 0.56 | - | - | - | - |

| Cotton + DA15 Before washing | 81.73 | −5.25 | 41.24 | −2.97 | −5.15 | 40.68 | 41.11 |

| Cotton + DA15 After washing | 82.13 | −5.08 | 40.63 | −2.57 | −4.98 | 40.46 | 40.84 |

| Cotton + DA30 Before washing | 80.79 | −3.75 | 43.52 | −3.91 | −3.65 | 42.96 | 43.29 |

| Cotton + DA30 After washing | 80.14 | −3.59 | 42.82 | −4.56 | −3.49 | 42.65 | 42.98 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Staneva, D.; Atanasova, D.; Grabchev, I. Photodynamic Microbial Defense of Cotton Fabric with 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled PAMAM Dendrimer. Materials 2025, 18, 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245570

Staneva D, Atanasova D, Grabchev I. Photodynamic Microbial Defense of Cotton Fabric with 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled PAMAM Dendrimer. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245570

Chicago/Turabian StyleStaneva, Desislava, Daniela Atanasova, and Ivo Grabchev. 2025. "Photodynamic Microbial Defense of Cotton Fabric with 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled PAMAM Dendrimer" Materials 18, no. 24: 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245570

APA StyleStaneva, D., Atanasova, D., & Grabchev, I. (2025). Photodynamic Microbial Defense of Cotton Fabric with 4-Amino-1,8-naphthalimide-Labeled PAMAM Dendrimer. Materials, 18(24), 5570. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245570