Influence of the Nd3+ Dopant Content in Bi3TeBO9 Powders on Their Optical Nonlinearity

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of BTBO:Nd3+ Samples

2.2. Samples Characterization

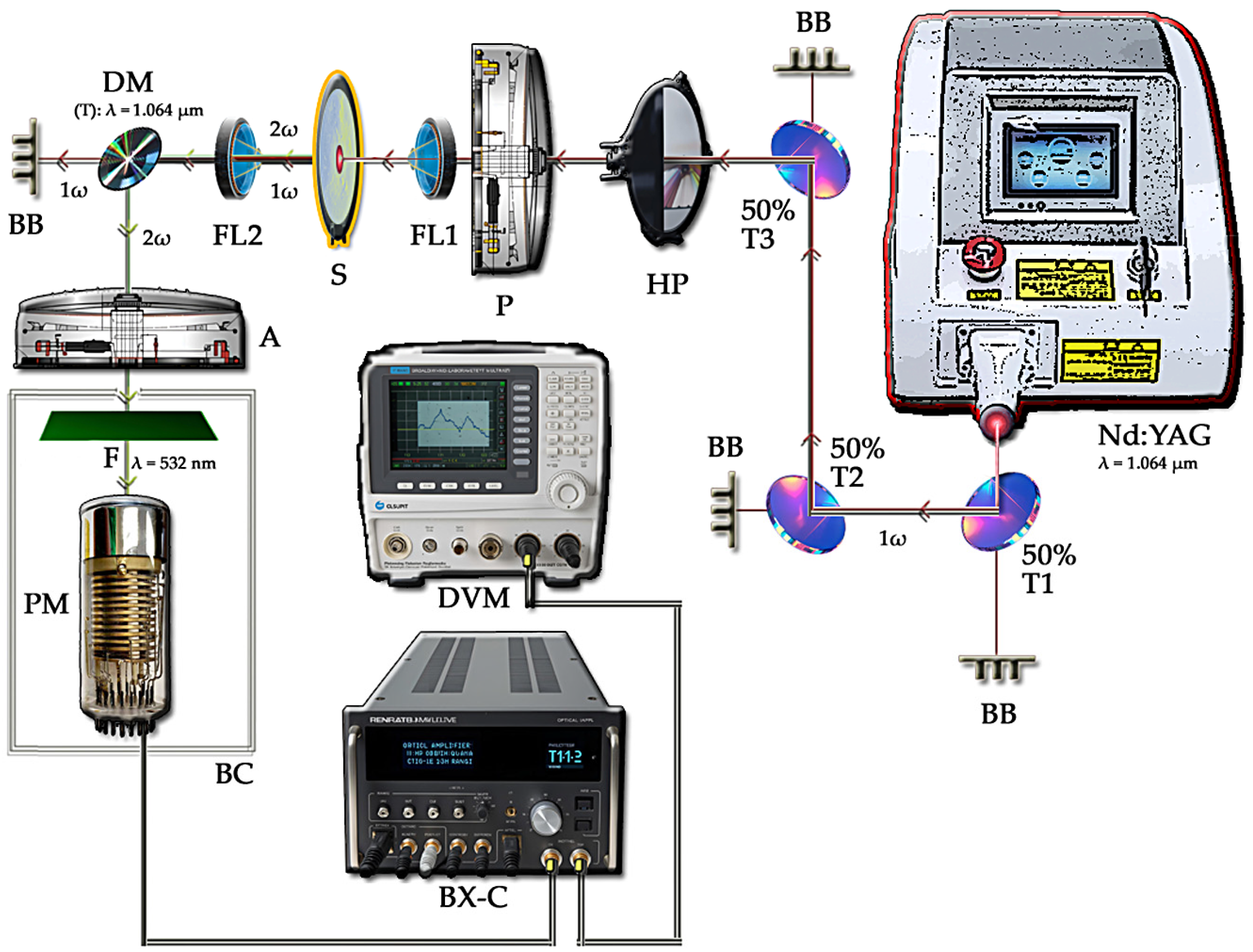

2.2.1. SHG Measurements at Room Temperature

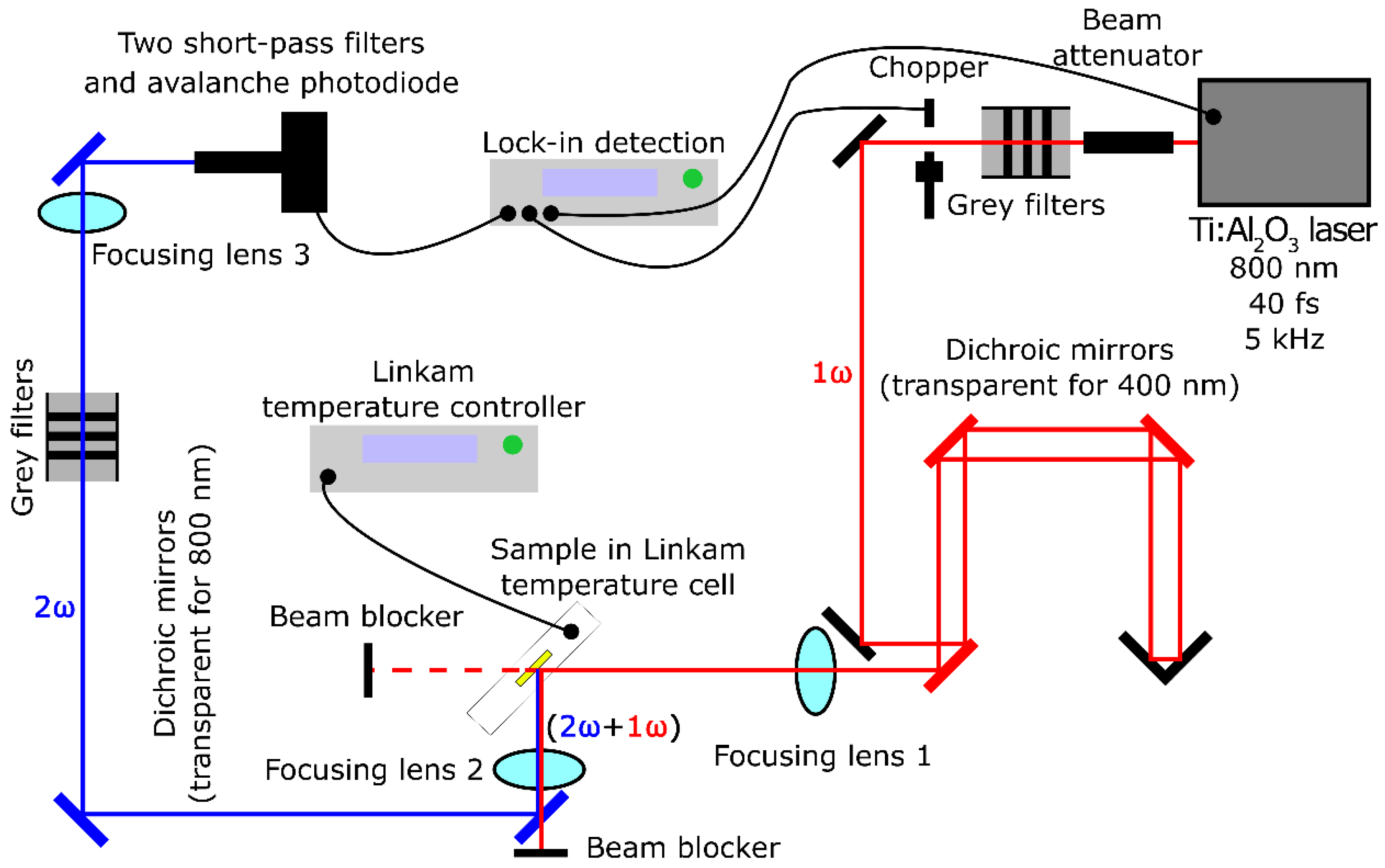

2.2.2. SHG Measurements at Higher Temperatures

2.2.3. UV-VIS Spectroscopic Studies

2.2.4. XRD Investigations

2.2.5. DTA/TG Measurements

2.2.6. EDX Studies

2.2.7. AFM Sample Preparation and Topography

3. Results and Discussion

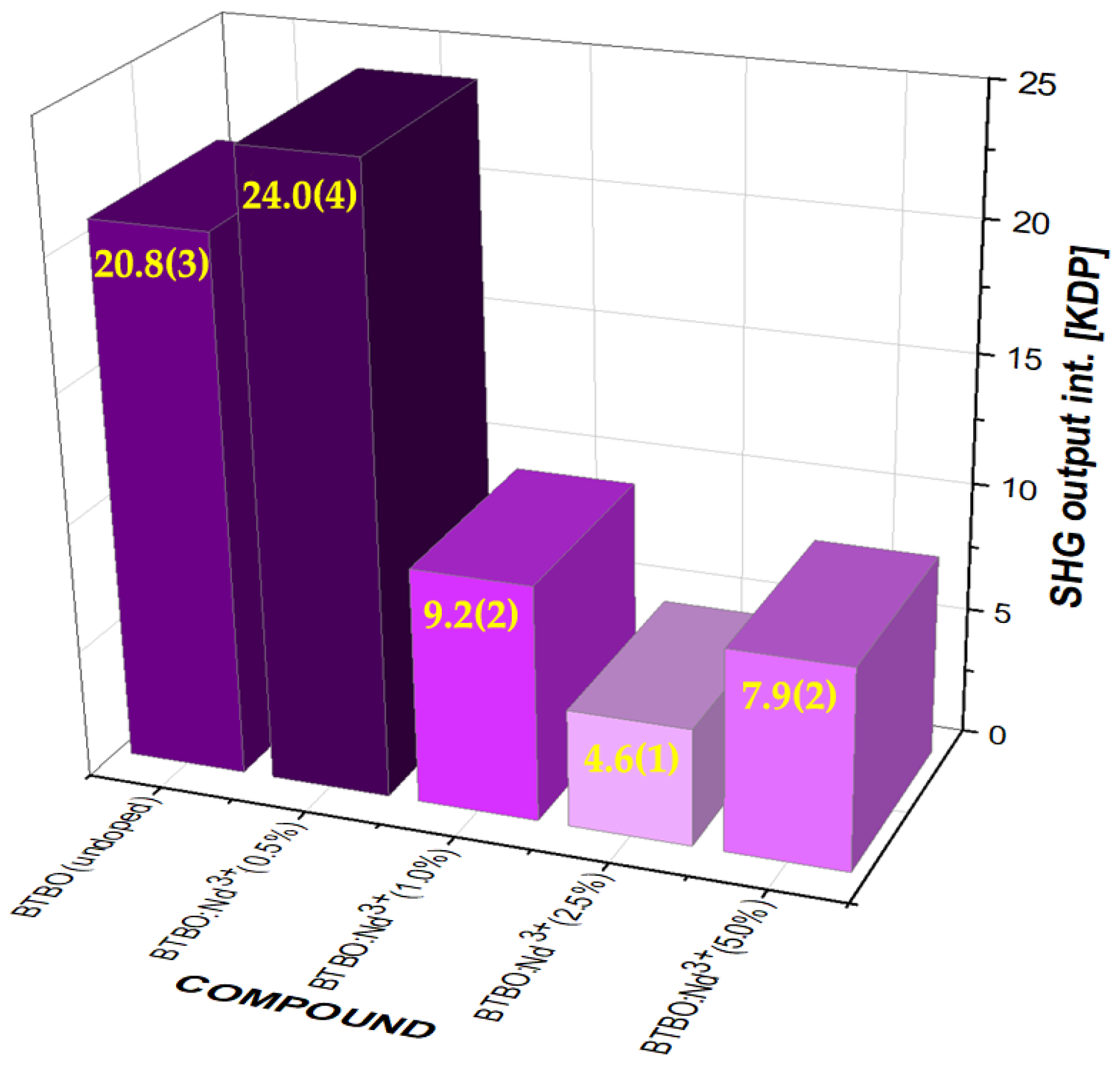

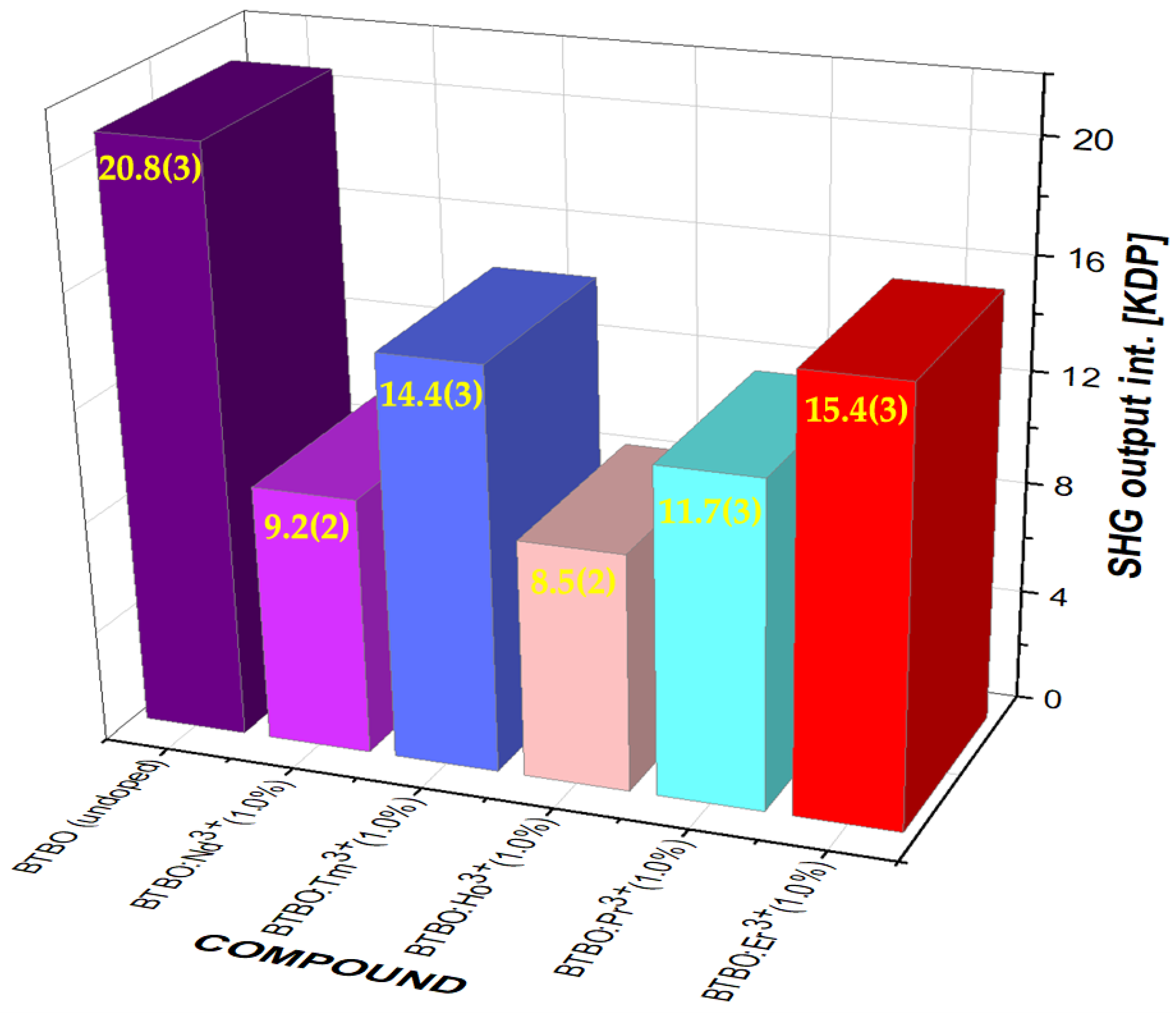

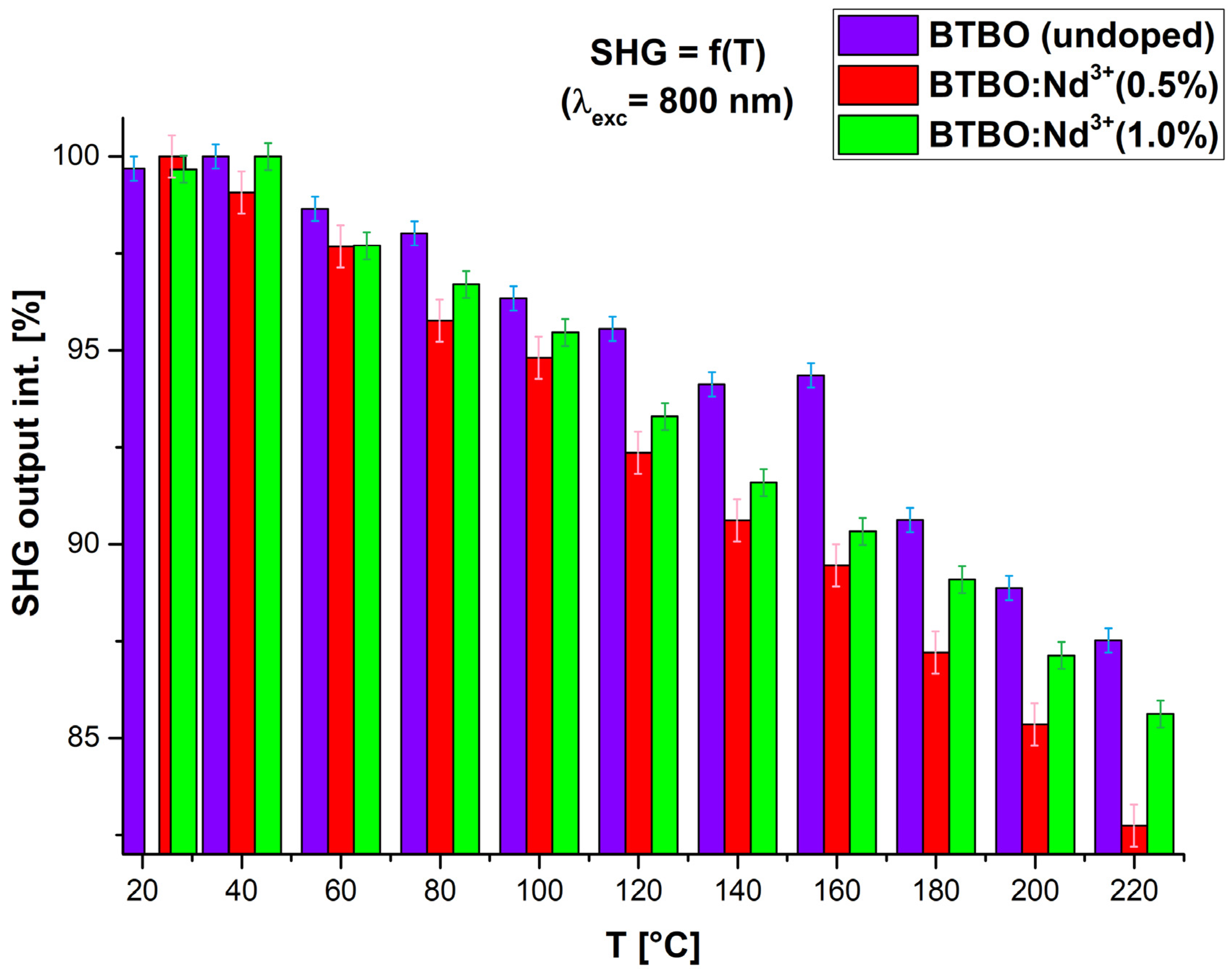

3.1. Effect of Nd3+ Content on Nonlinear Optical Behavior of BTBO:Nd3+

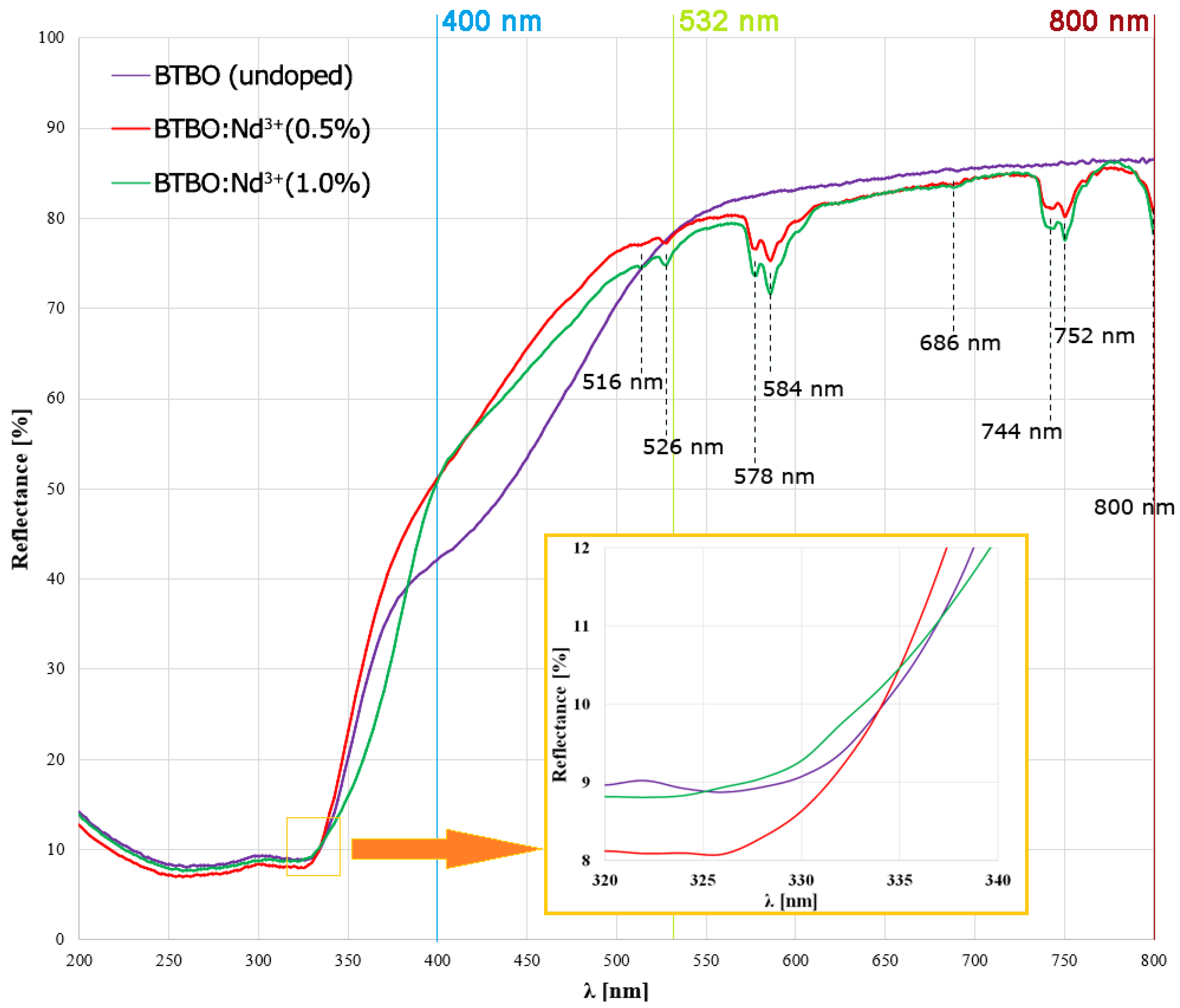

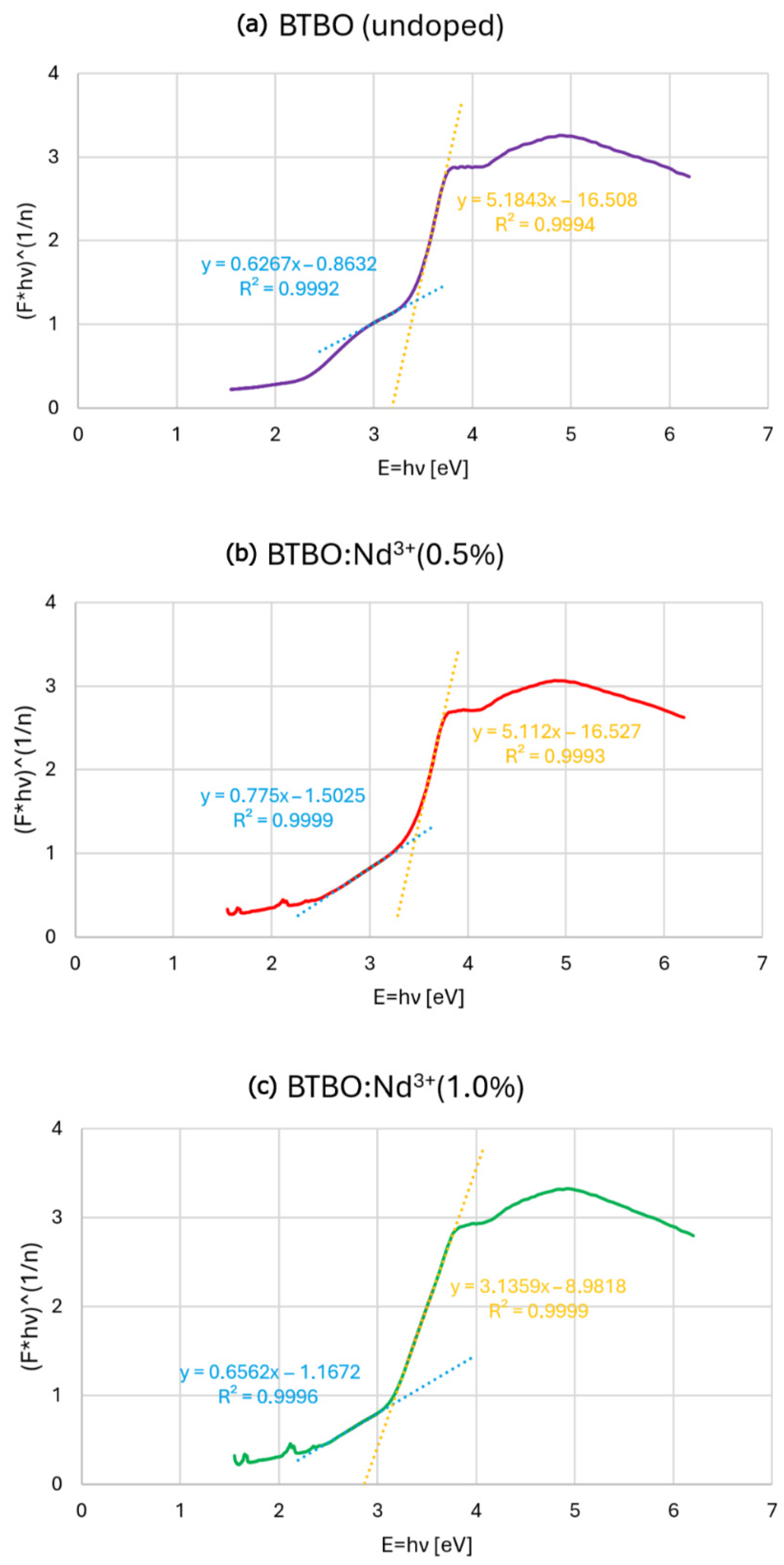

3.2. Absorption Studies and Determination of the Energy Band Gap of BTBO:Nd3+

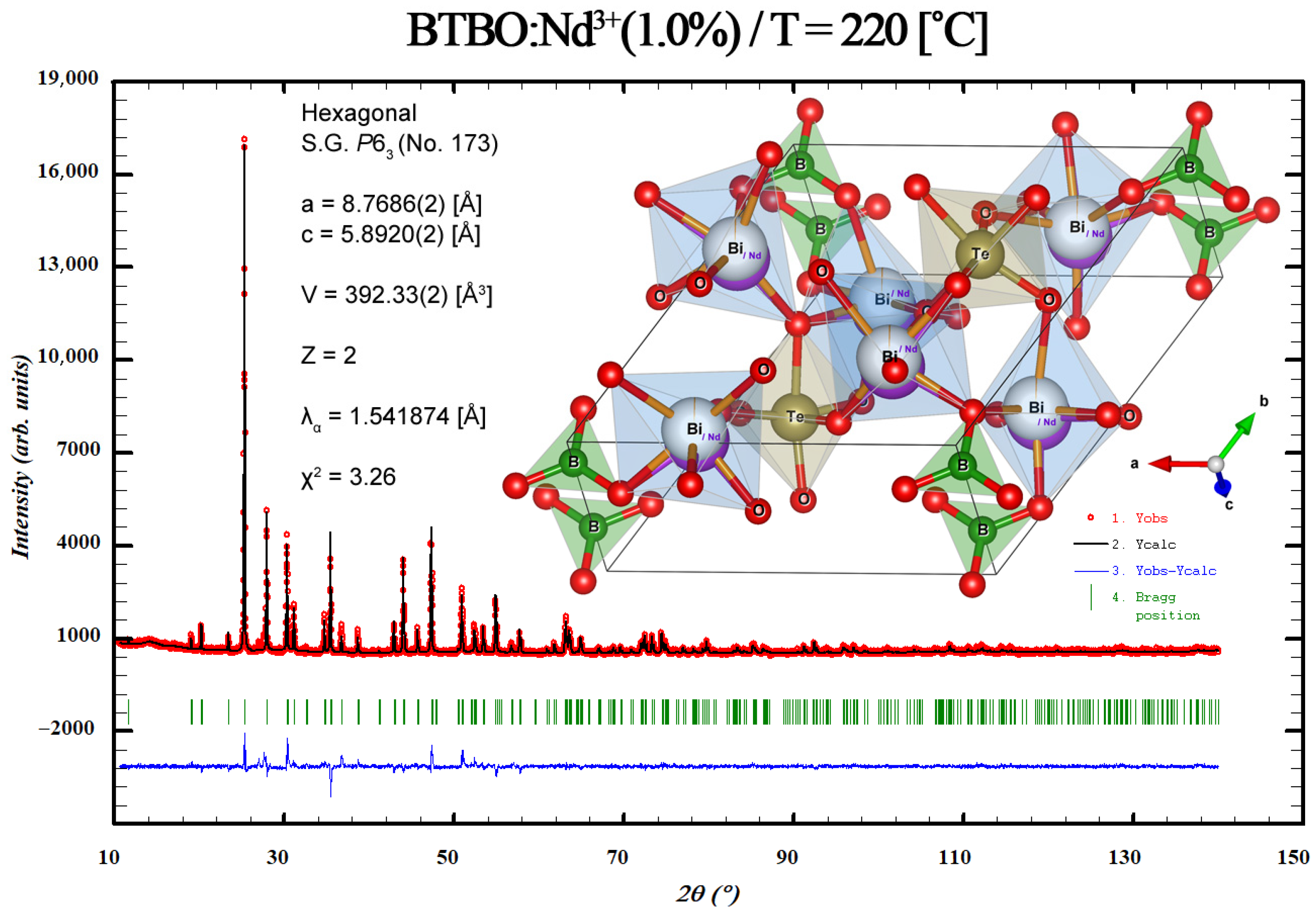

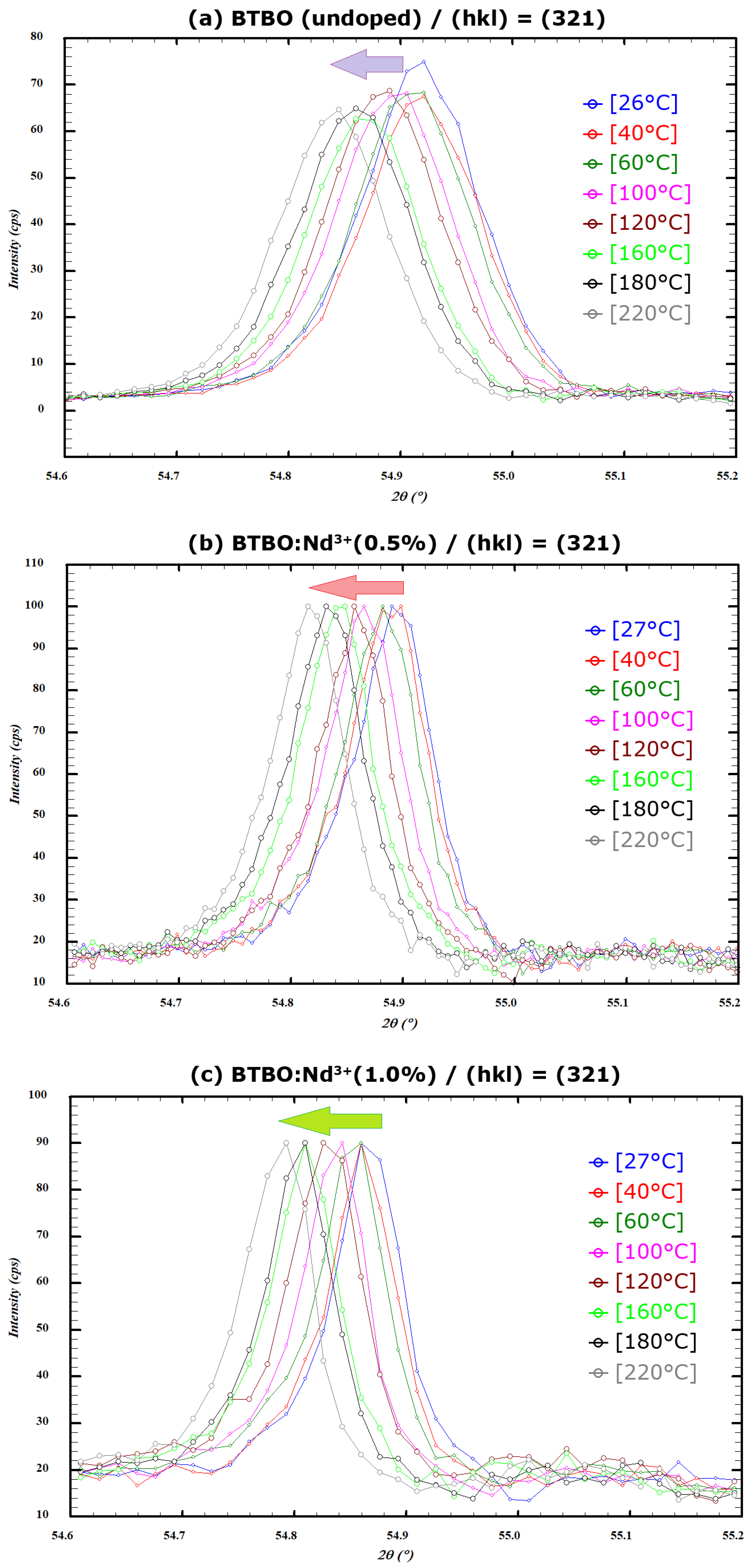

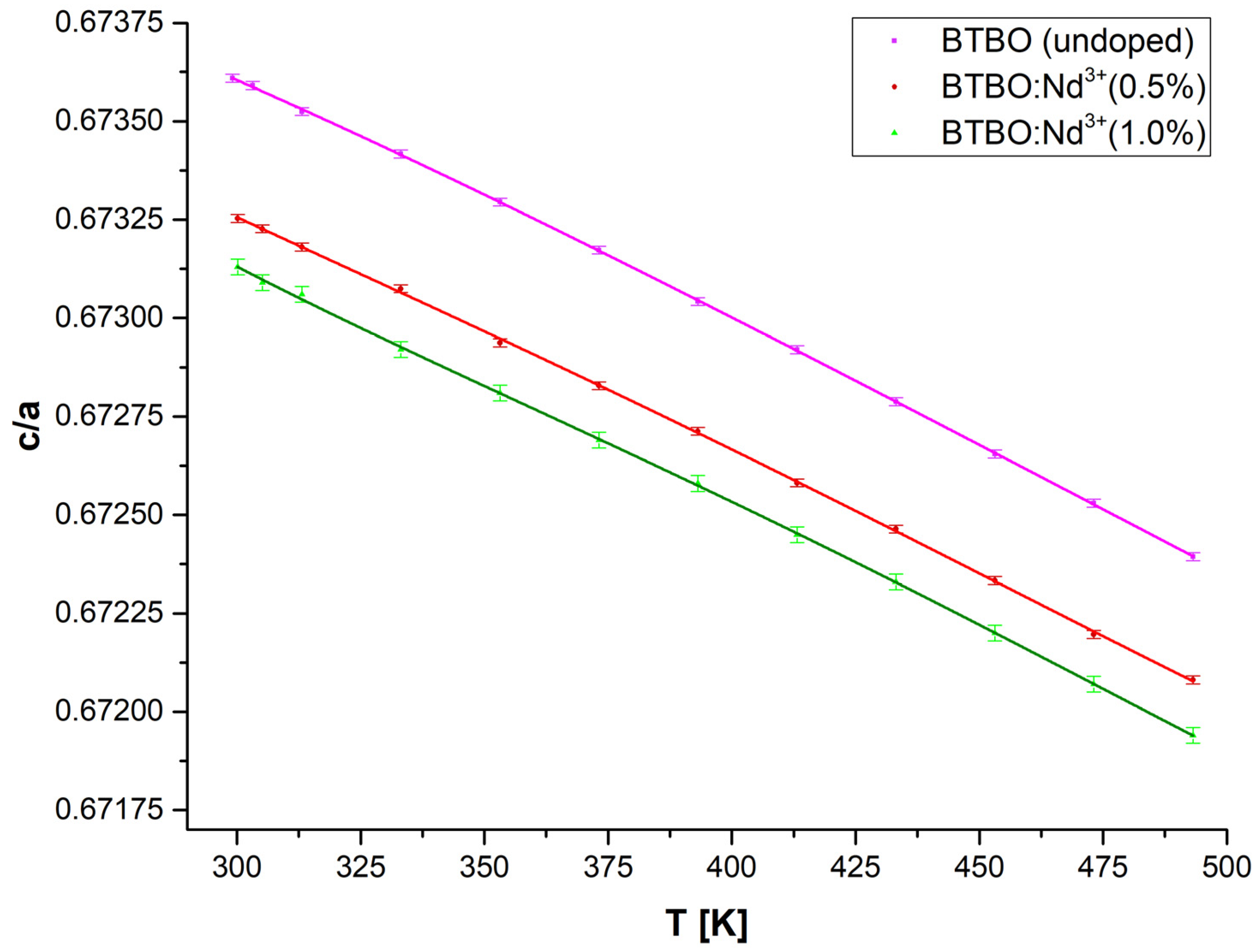

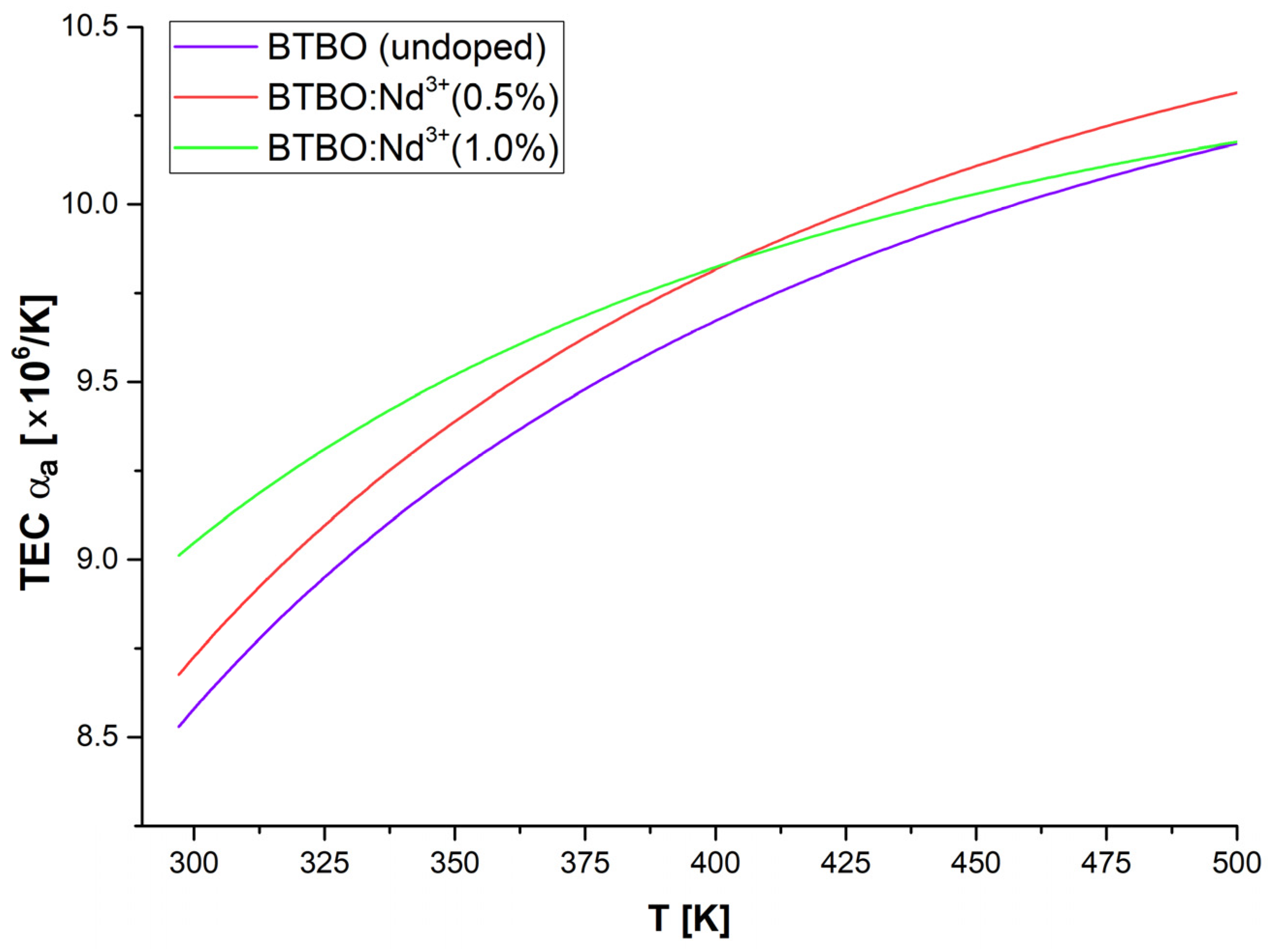

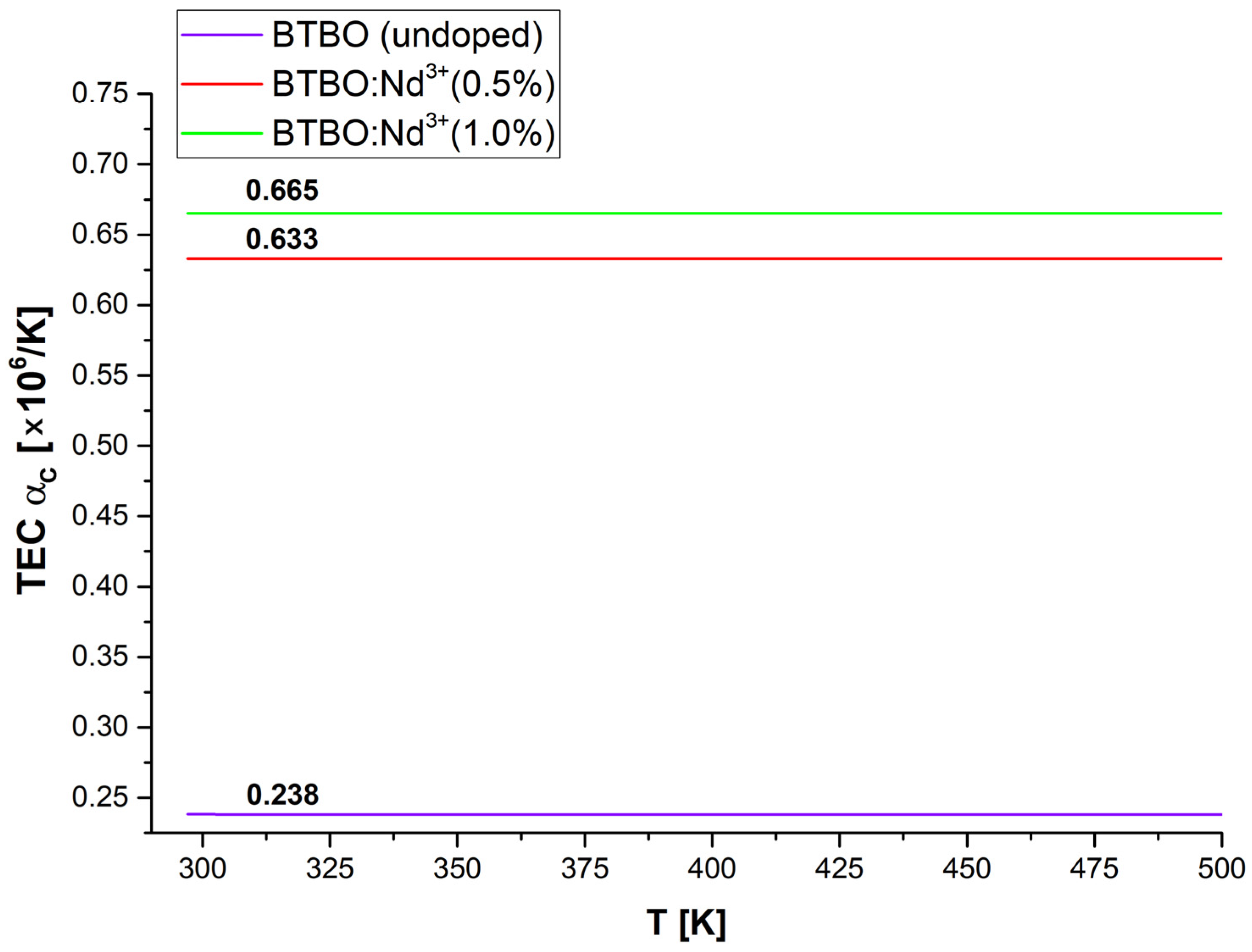

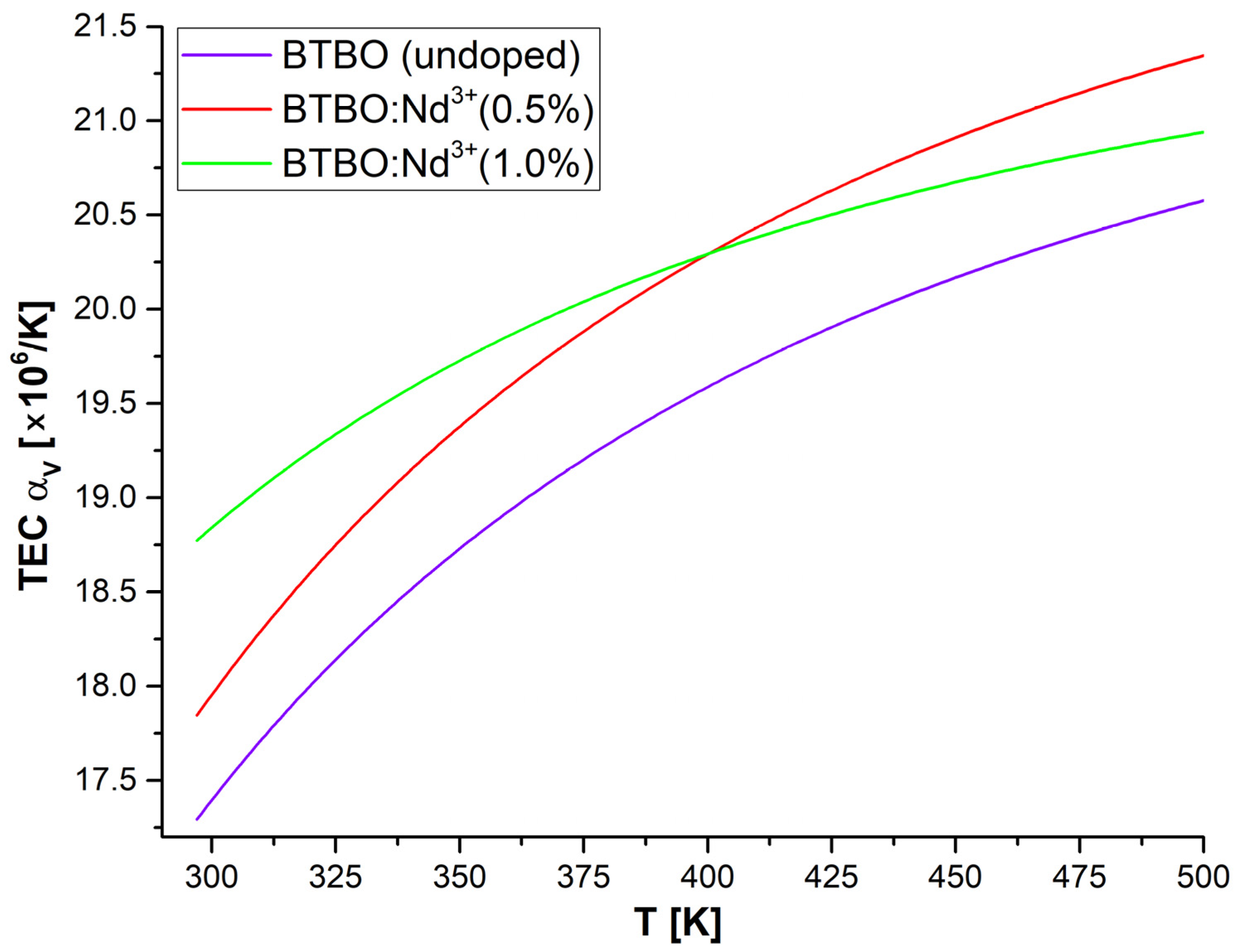

3.3. Anisotropy of Thermal Expansion in BTBO:Nd3+

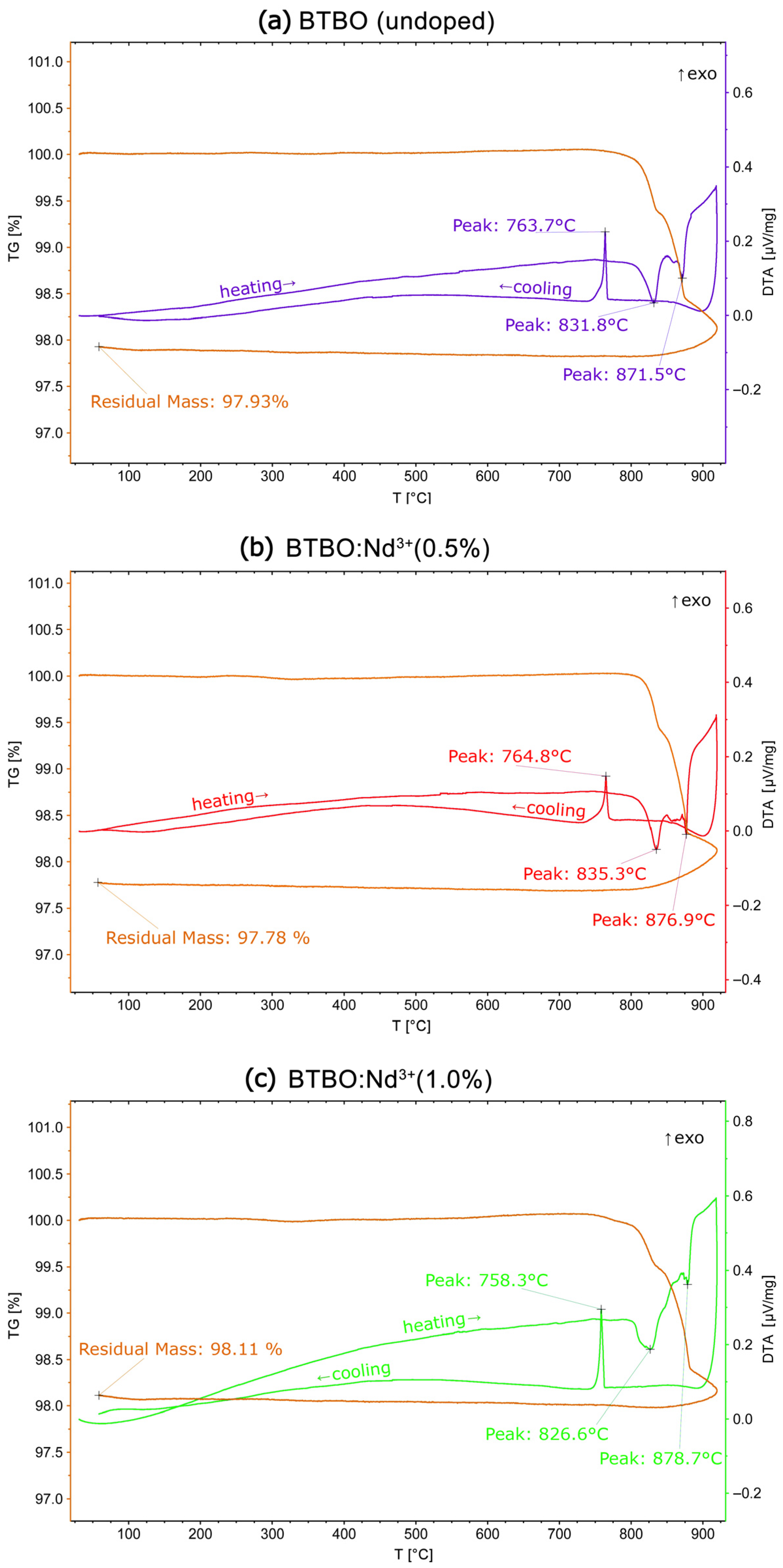

3.4. Thermal Stability of BTBO:Nd3+

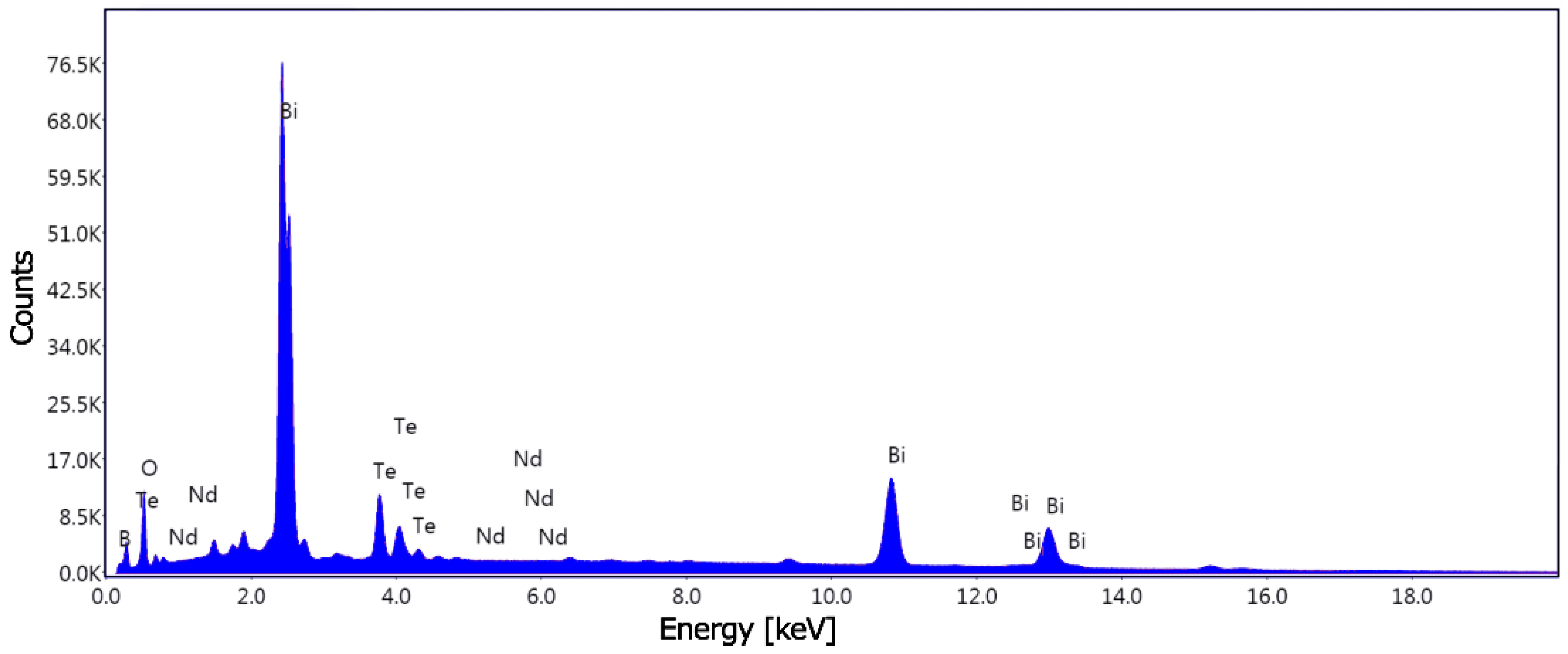

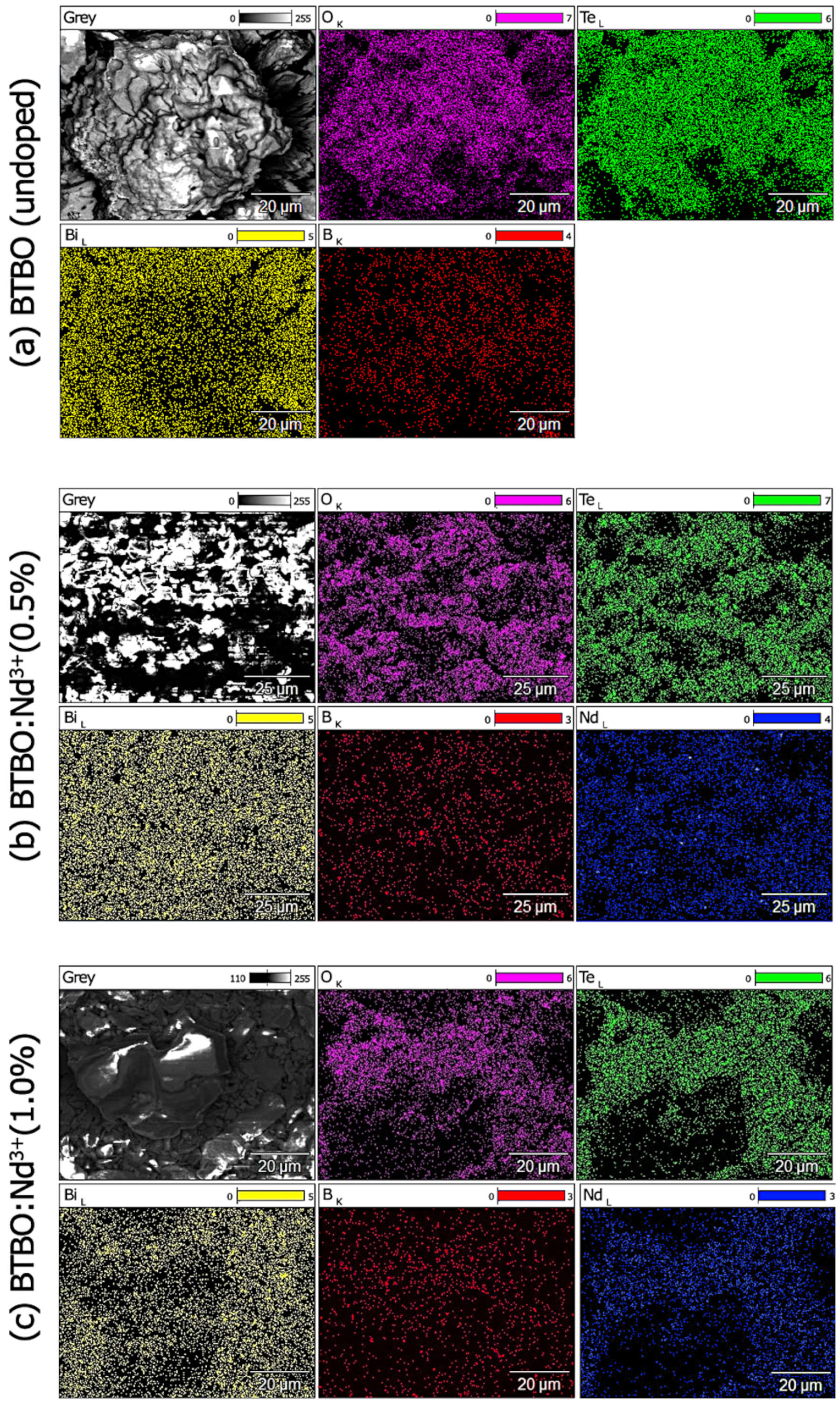

3.5. Distribution of Neodymium Dopant in BTBO:Nd3+

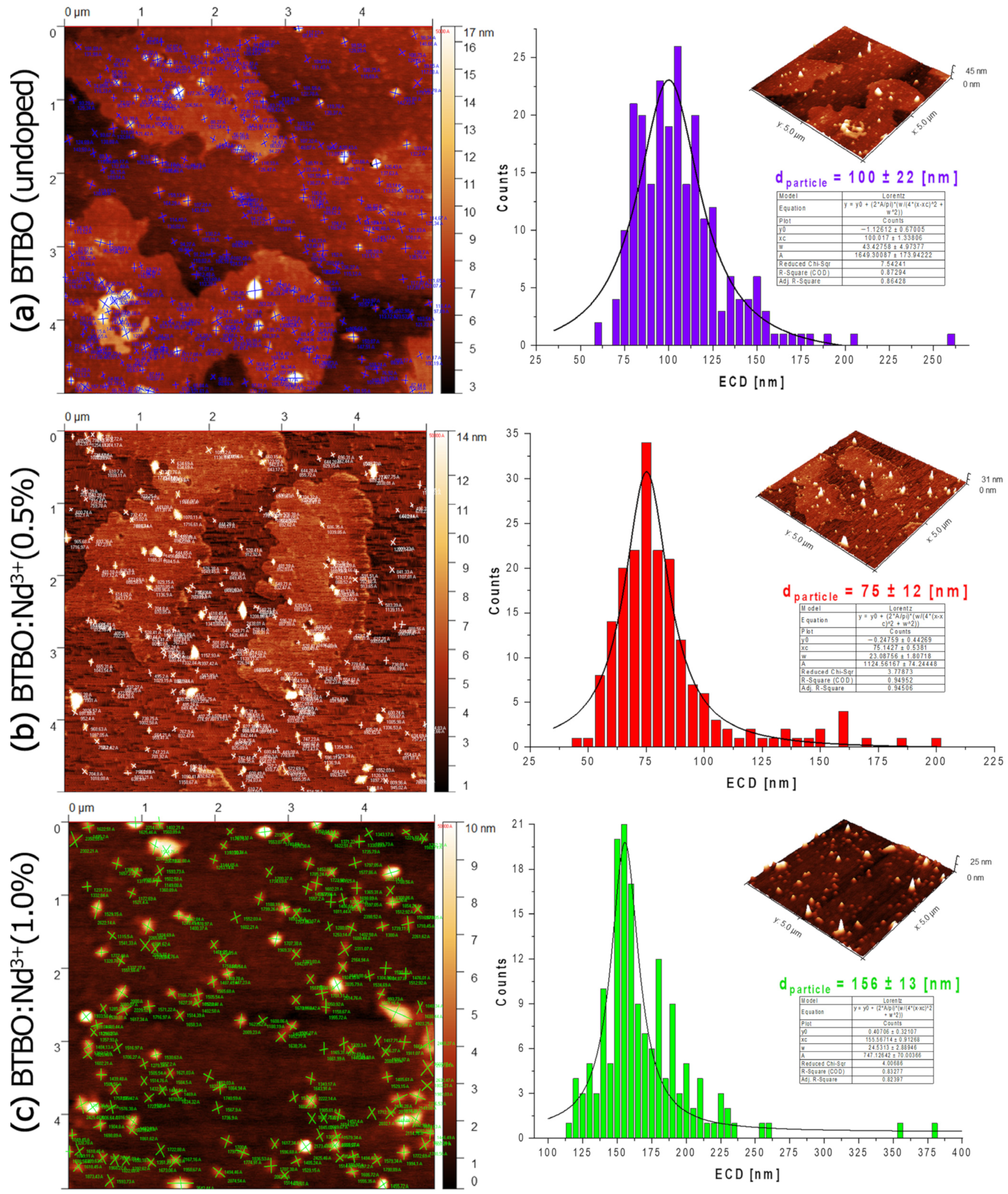

3.6. Morphology of BTBO:Nd3+ Nanofraction

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Daub, M.; Krummer, M.; Hoffmann, A.; Bayarjargal, L.; Hillebrecht, H. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Properties of Bi3TeBO9 or Bi3(TeO6)(BO3): A Non-Centrosymmetric Borate–Tellurate (VI) of Bismuth. Chem.-Eur. J. 2017, 23, 1331–1337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xia, M.; Jiang, X.; Lin, Z.; Li, R. “All-Three-in-One”: A New Bismuth–Tellurium–Borate Bi3TeBO9 Exhibiting Strong Second Harmonic Generation Response. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 14190–14193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasprowicz, D.; Zhezhera, T.; Lapinski, A.; Chrunik, M.; Majchrowski, A.; Kityk, A.V.; Shchur, Y. Lattice Dynamics of Bi3TeBO9 Microcrystals: μ-Raman/IR Spectroscopic Investigation and Ab Initio Analysis. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 782, 488–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R.G. Concerning Jahn–Teller Effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1975, 72, 2104–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Li, R. Large Difference in Nonlinear Optical Activity of Rare Earth Ion Substitution of Bi3+ in A3TeBO9 (A = Bi, La, Pr, Nd, Sm–Dy). Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 11265–11270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. Bi3TeBO9: A Borate Piezoelectric Crystal with a High Piezoelectric Coefficient. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 4243–4249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, B.; Zhu, M.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Wang, J. Bi3TeBO9: A Promising Mid-Infrared Nonlinear Optical Crystal with a Large Laser Damage Threshold. Inorg. Chem. 2022, 61, 8870–8878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenier, A.; Kityk, I.V.; Majchrowski, A. Evaluation of Nd3+-Doped BiB3O6 (BIBO) as a New Potential Self-Frequency Conversion Laser Crystal. Opt. Commun. 2002, 203, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhezhera, T.; Gluchowski, P.; Nowicki, M.; Chrunik, M.; Majchrowski, A.; Kosyl, K.M.; Kasprowicz, D. Efficient Near-Infrared Quantum Cutting by Cooperative Energy Transfer in Bi3TeBO9:Nd3+ Phosphors. J. Mater. Sci. 2022, 57, 185–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Sun, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, X.; Petrov, V.; Wang, J. Growth, Luminescence, and Judd–Ofelt Analysis of Pr3+ Doped Bi3TeBO9 Single Crystal. J. Lumin. 2025, 279, 121043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, H.; Xiang, Y.; Zhu, J. Content and Temperature Quenching of Tb3+-Activated Bi3TeBO9 Green Phosphor Excited by NUV/VIS Light. J. Solid. State Chem. 2022, 313, 123317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhezhera, T.; Gluchowski, P.; Nowicki, M.; Chrunik, M.; Majchrowski, A.; Kasprowicz, D. Enhanced Near-Infrared Emission of Er3+ as a Synergistic Effect of Energy Transfers in Bi3TeBO9:Yb3+/Er3+ Phosphors. J. Lumin. 2023, 258, 119774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhezhera, T.; Gluchowski, P.; Nowicki, M.; Chrunik, M.; Szczesniak, B.; Kasprowicz, D. Enhancement of Yb3+ Emission in Bi3TeBO9 through Efficient Energy Transfer from Bi3+ Ions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2024, 128, 14357–14367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.T.; Prewitt, C.T. Revised values of effective ionic radii. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B 1970, 26, 1046–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, S.; Wang, H.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, X. High-Performance, High-Temperature Piezoelectric BiB3O6 Crystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 2015, 3, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Liu, Q.J.; Jiang, C.L.; Liu, F.S.; Tang, B.; Peng, X.J. Structural, Elastic, Electronic, Phonon, Dielectric and Optical Properties of Bi3TeBO9 from First-Principles Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2018, 121, 139–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majchrowski, A.; Chrunik, M.; Rudysh, M.; Piasecki, M.; Ozga, K.; Lakshminarayana, G.; Kityk, I.V. Bi3TeBO9: Electronic Structure, Optical Properties, and Photoinduced Phenomena. J. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 1217–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrunik, M.; Majchrowski, A.; Szala, M.; Zasada, D.; Kroupa, J.; Bubnov, A.; Woźniak, M.J. Microstructural and Nonlinear Optical Properties of Bi2ZnB2O7:RE3+ Powders. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 694, 959–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostaço-Guidolin, L.; Rosin, N.L.; Hackett, T.L. Imaging Collagen in Scar Tissue: Developments in Second Harmonic Generation Microscopy for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisek, R.; Harvey, M.; Bennett, E.; Jeon, H.; Tokarz, D. Polarization-Resolved SHG Microscopy for Biomedical Applications. In Optical Polarimetric Modalities for Biomedical Research; Springer International Publishing: Cham, The Switzerland, 2023; pp. 215–257. [Google Scholar]

- Dempsey, W.P.; Fraser, S.E.; Pantazis, P. SHG Nanoprobes: Advancing Harmonic Imaging in Biology. BioEssays 2012, 34, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villazon, J.I.; Jang, H.; Shi, L. Nonlinear Optical Imaging Modalities in Biomedicine. GEN Biotechnol. 2024, 3, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizuguchi, T.; Nuriya, M. Applications of Second Harmonic Generation (SHG)/Sum-Frequency Generation (SFG) Imaging for Biophysical Characterization of the Plasma Membrane. Biophys. Rev. 2020, 12, 1321–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.; Yun, S.H. Optofluidic Bio-Lasers: Concept and Applications. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, S.; Chen, Z.H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Yin, F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, M.; et al. Near-Infrared Spatiotemporal Color Vision in Humans Enabled by Upconversion Contact Lenses. Cell 2025, 188, 3375–3388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Bao, J.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, X.; Wan, C.; Huang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Han, G.; Xue, T. Mammalian Near-Infrared Image Vision through Injectable and Self-Powered Retinal Nanoantennae. Cell 2019, 177, 243–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhezhera, T.; Gluchowski, P.; Nowicki, M.; Chrunik, M.; Miklaszewski, A.; Kasprowicz, D. Pressure-Modified Upconversion Luminescence of Yb3+ and Er3+-Doped Bi3TeBO9 Ceramics. J. Lumin. 2024, 268, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Pan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J. Recent Advances in Self-Frequency-Doubling Crystals. J. Mater. 2016, 2, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikogosyan, D.N. Nonlinear Optical Crystals: A Complete Survey; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, L.F.; Ballman, A.A. Coherent Emission from Rare Earth Ions in Electro-Optic Crystals. J. Appl. Phys. 1969, 40, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dmitriev, V.G.; Raevskii, E.V.; Rubina, N.M.; Rashkovich, L.N.; Silichev, O.O.; Fomichev, A.A. Simultaneous Emission at the Fundamental Frequency and the Second Harmonic in an Active Nonlinear Medium: Neodymium-Doped Lithium Metaniobate. Sov. Tech. Phys. Lett. 1979, 4, 590. [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin, L.M.; Kuratev, I.I.; Leoniuk, N.I.; Timchenko, T.I.; Shestakov, A.V. Optical Second-Harmonic Generation in a New Nonlinear Active Neodymium-Yttrium-Aluminum Borate Crystals. Tech. Phys. Lett. 1981, 7, 555. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, C.; Qiu, M.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Jiang, A.; Luo, Z. The Study of a Self-Frequency-Doubling Laser Crystal Nd3+:GdAl3(BO3)4. J. Cryst. Growth 2000, 208, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petermann, K. Oxide Laser Crystals Doped with Rare Earth and Transition Metal Ions. In Handbook of Solid-State Lasers; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.Y.; Yu, H.H.; Zhang, H.J.; Li, J.; Zong, N.; Xu, Z.Y. Progress on the Research and Potential Applications of Self-Frequency Doubling Crystals. Prog. Phys. 2011, 31, 91–110. [Google Scholar]

- Desurvire, E.; Zervas, M.N. Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers: Principles and Applications. Phys. Today 1995, 48, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dejneka, M.J.; Streltsov, A.; Pal, S.; Frutos, A.G.; Powell, C.L.; Yost, K.; Yuen, P.K.; Müller, U.; Lahiri, J. Rare Earth-Doped Glass Microbarcodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 389–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Condon, E.U.; Shortley, G.H. The Theory of Atomic Spectra; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1935. [Google Scholar]

- Laporte, O.; Meggers, W.F. Some Rules of Spectral Structure. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1925, 11, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pechini, M.P. Method of Preparing Lead and Alkaline Earth Titanates and Niobates and Coating Method Using the Same to Form a Capacitor. U.S. Patent No. 3330697, 11 July 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Matulková, I.; Cihelka, J.; Pojarová, M.; Fejfarová, K.; Dušek, M.; Vaněk, P.; Kroupa, J.; Krupková, R.; Fábry, J.; Němec, I. A new Series of 3,5-Diamino-1,2,4-Triazolium (1+) Inorganic Salts and Their Potential in Crystal Engineering of Novel NLO Materials. CrystEngComm 2012, 14, 4625–4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtz, S.K.; Perry, T.T. A Powder Technique for the Evaluation of Nonlinear Optical Materials. J. Appl. Phys. 1968, 39, 3798–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinakaran, S.; Verma, S.; Das, S.J.; Bhagavannarayana, G.; Kar, S.; Bartwal, K.S. Investigations of Crystalline and Optical Perfection of SHG Oriented KDP Crystals. Appl. Phys. A 2010, 99, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, R.; Boudrioua, A.; Loulergue, J.C.; Iltis, A. Effective Nonlinear Coefficients of Organic Powders Measured by Second-Harmonic Generation in Total Reflection: Numerical and Experimental Analysis. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 1999, 16, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haryński, Ł.; Olejnik, A.; Grochowska, K.; Siuzdak, K. A Facile Method for Tauc Exponent and Corresponding Electronic Transitions Determination in Semiconductors Directly from UV–Vis Spectroscopy Data. Opt. Mater. 2022, 127, 112205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makuła, P.; Pacia, M.; Macyk, W. How to Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV–Vis Spectra. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2018, 9, 6814–6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Carvajal, J. Recent Advances in Magnetic Structure Determination by Neutron Powder Diffraction. Phys. B 1993, 192, 55–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A.L. The Scherrer Formula for X-ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Born, M.; Wolf, E. Principles of Optics: Electromagnetic Theory of Propagation, Interference, and Diffraction of Light; Pergamon Press: Oxford, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Dmitriev, V.G.; Gurzadyan, G.G.; Nikogosyan, D.N. Handbook of Nonlinear Optical Crystals; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; Volume 64. [Google Scholar]

- Cong, R.; Yang, T.; Lin, Z.; Bai, L.; Ju, J.; Liao, F.; Wang, Y.; Lin, J. Rare Earth Induced Formation of δ-BiB3O6 at Ambient Pressure with Strong Second Harmonic Generation. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 17934–17941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Lin, Z. Deep-Ultraviolet Nonlinear Optical Crystals: Concept Development and Materials Discovery. Light. Sci. Appl. 2022, 11, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, R.; Wang, Y.; Kang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Lin, Z.; Yang, T. An Outstanding Second-Harmonic Generation Material, BiB2O4F: Exploiting the Electron-Withdrawing Ability of Fluorine. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Nakajima, S.; Taguchi, A.; Miyamoto, A.; Inagaki, M.; Sasaki, T.; Yoshida, H.; Nakai, S. New Nonlinear Optical Crystal CsLiB6O10 for Laser Fusion. AIP Conf. Proc. 1996, 369, 998–1003. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Fu, P.; Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, G.; Chen, C. A New Lanthanum and Calcium Borate La2CaB10O19. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yang, F.; Wang, X.; Zhou, J.; Ju, J.; Huang, L.; Gao, D.; Bi, J.; Zou, G. Deep-Ultraviolet Mixed-Alkali-Metal Borates with Induced Enlarged Birefringence Derived from the Structure Rearrangement of LiB3O5. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 5949–5955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Yue, Y.; Yao, J.; Hu, Z.G. YAl3(BO3)4: Crystal Growth and Characterization. J. Cryst. Growth 2010, 312, 3029–3033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shannon, R.D. Revised Effective Ionic Radii and Systematic Studies of Interatomic Distances in Halides and Chalcogenides. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 1976, 32, 751–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Jiang, S.; Liu, A.; Ye, L.; Ke, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, L.; Liu, Y.; Hong, M. Proof of Crystal-Field-Perturbation-Enhanced Luminescence of Lanthanide-Doped Nanocrystals through Interstitial H+ Doping. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherupally, L. Influence of Rare Earth Doping and Modifier Oxides on Optical and Thermoluminescence Properties of Tellurite Glasses for Radiation Dosimetry Applications. East Afr. J. Sci. Technol. Innov. 2024, 6, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, L.B.; Murthy, K.K.; Rajeev, Y.N.; Madhavan, J.; Sagayaraj, P.; Cole, S. Influence of Rare Earth Doping on the Spectral, Thermal, Morphological, and Optical Properties of Nonlinear Optical Single Crystals of Manganese Mercury Thiocyanate, MnHg(SCN)4. Optik 2015, 126, 4899–4904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komarala, V.K.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, M. Nonlinear Optical Properties of Er3+/Yb3+-Doped NaYF4 Nanocrystals. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2010, 490, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; He, C.; Dong, B.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, K.; Deng, C.; Li, Q.; Lu, Y. Investigation on Nonlinear Absorption and Optical Limiting Properties of Tm:YLF Crystals. Opt. Mater. 2024, 147, 114786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajna, M.S.; Perumbilavil, S.; Prakashan, V.P.; Sanu, M.S.; Joseph, C.; Biju, P.R.; Unnikrishnan, N.V. Enhanced Resonant Nonlinear Absorption and Optical Limiting in Er3+ Ions Doped Multicomponent Tellurite Glasses. Mater. Res. Bull. 2018, 104, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aramburu, I.; Ortega, J.; Folcia, C.L.; Etxebarria, J. Second-Harmonic Generation in Dry Powders: A Simple Experimental Method to Determine Nonlinear Efficiencies under Strong Light Scattering. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 071107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, A.E.; Ganem, J. Optical Thermometry Using Temperature-Dependent Absorption in Rare Earth-Doped Crystals. In Optical Components and Materials XXII; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2025; Volume 13362, pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Kornienko, A.; Loiko, P.; Dunina, E.; Fomicheva, L.; Kornienko, A. On the Temperature Dependence of Transition Intensities of Rare-Earth Ions: A Modified Judd–Ofelt Theory. Opt. Mater. 2024, 148, 114808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Ballato, J.; Riman, R.E. Temperature-Dependence of Multiphonon Relaxation of Rare-Earth Ions in Solid-State Hosts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 9958–9964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Lara, F.; Ramírez, M.O.; Flores, M.; Arroyo, R.; Caldiño, U. Optical Spectroscopy of Nd3+ Ions in Poly(acrylic acid). J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, 7951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balda, R.; Fernández, J.; Nyein, E.E.; Hömmerich, U. Infrared to Visible Upconversion of Nd3+ Ions in KPb2Br5 Low Phonon Crystal. Opt. Express 2006, 14, 3993–4004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mhlongo, M.R.; Koao, L.F.; Motaung, T.E.; Kroon, R.E.; Motloung, S.V. Analysis of Nd3+ Concentration on the Structure, Morphology and Photoluminescence of Sol-Gel Sr3ZnAl2O7 Nanophosphor. Results Phys. 2019, 12, 1786–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babu, S.S.; Babu, P.; Jayasankar, C.K.; Joshi, A.S.; Speghini, A.; Bettinelli, M. Luminescence and Optical Absorption Properties of Nd3+ Ions in K–Mg–Al Phosphate and Fluorophosphate Glasses. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2006, 18, 3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, A.; Gupta, M.; Kottilil, D.; Rath, B.B.; Vittal, J.J.; Ji, W. Anisotropic Two-Photon Absorption and Second Harmonic Generation in Single Crystals of Silver(I) Coordination Complexes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 31891–31897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Z.; Tu, C.; Li, J.; Wu, B. Crystal Growth and Spectroscopic Characterizations of Pure and Nd3+-Doped Cd3Y(BO3)3 Crystals. J. Cryst. Growth 2004, 263, 291–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favre, S.; Sidler, T.C.; Salathé, R.P. High-Power Long-Pulse Second Harmonic Generation and Optical Damage with Free-Running Nd:YAG Laser. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2003, 39, 733–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capmany, J.; García Solé, J. Second Harmonic Generation in LaBGeO5:Nd3+. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1997, 70, 2517–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardar, D.K.; Yow, R.M. Inter-Stark Energy Levels and Effects of Temperature on Sharp Emission Lines of Nd3+ in LiYF4. Phys. Status Solidi A 1999, 173, 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroud, J.S. Concentration Quenching of Nd3+ Fluorescence. Appl. Opt. 1968, 7, 751–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotti, R.E.; Giorgi, P.; Machado, G.; Dalchiele, E.A. Crystallite Size Dependence of Band Gap Energy for Electrodeposited ZnO Grown at Different Temperatures. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2006, 90, 2356–2361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.Z.; Khare, N. Effect of Intrinsic Strain on the Optical Band Gap of Single-Phase Nanostructured Cu2ZnSnS4. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2017, 63, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khatun, M.; Mitra, P.; Mukherjee, S. Effect of Band Gap and Particle Size on Photocatalytic Degradation of NiSnO3 Nanopowder for Some Conventional Organic Dyes. Hybrid. Adv. 2023, 4, 100079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caicedo-Dávila, S.; Caprioglio, P.; Lehmann, F.; Levcenco, S.; Stolterfoht, M.; Neher, D.; Kronik, L.; Abou-Ras, D. Effects of Quantum and Dielectric Confinement on the Emission of Cs–Pb–Br Composites. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2305240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadava, K.; Gallo, G.; Bette, S.; Mulijanto, C.E.; Karothu, D.P.; Park, I.H.; Medishetty, R.; Naumov, P.; Dinnebier, R.E.; Vittal, J.J. Extraordinary Anisotropic Thermal Expansion in Photosalient Crystals. IUCrJ 2020, 7, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Guo, Z.; Song, B. Application of Lagrange Equations in Heat Conduction. Tsinghua Sci. Technol. 2009, 14, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barron, T.H.K. Generalized Theory of Thermal Expansion of Solids. In Thermal Expansion of Solids; ASM International: Materials Park, OH, USA, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- Mosafer, H.S.R.; Paszkowicz, W.; Minikayev, R.; Kozłowski, M.; Diduszko, R.; Berkowski, M. The Crystal Structure and Thermal Expansion of Novel Substitutionally Disordered Ca10TM0.5(VO4)7 (TM = Co, Cu) Orthovanadates. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 14762–14773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCammon, R.D.; White, G.K. Thermal Expansion at Low Temperatures of Hexagonal Metals: Mg, Zn and Cd. Philos. Mag. 1965, 11, 1125–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.S.; Guan, H.; Shiota, Y.; He, C.T.; Wang, X.L.; Wu, S.Q.; Zheng, X.; Su, S.-Q.; Yoshizawa, K.; Kong, X.; et al. Giant Anisotropic Thermal Expansion Actuated by Thermodynamically Assisted Reorientation of Imidazoliums in a Single Crystal. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulbert, B.S.; Brodecki, J.E.; Kriven, W.M. Crystal Structure Solution and High-Temperature Thermal Expansion in NaZr2(PO4)3-Type Materials. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. B Struct. Sci. 2024, 80, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.G.; Zhu, Z.J.; You, Z.Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J.F.; Sun, C.L.; Cao, J.F.; Ji, Y.X.; Wang, Y.Q.; Tu, C.Y. The Growth, Thermal and Nonlinear Optical Properties of Single-Crystal GdAl3(BO3)4. Laser Phys. 2011, 21, 750–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, F.; Wu, Y.; Fu, P.; Guo, R. Thermal Expansion of Nonlinear Optical Crystal La2CaB10O19. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2005, 44, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. Experimental Analysis of Overall Thermal Properties of Nd:La2CaB10O19 Crystals. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartasyte, A.; Plausinaitiene, V.; Abrutis, A.; Murauskas, T.; Boulet, P.; Margueron, S.; Gleize, J.; Robert, S.; Kubilius, V.; Saltyte, Z. Residual Stresses and Clamped Thermal Expansion in LiNbO3 and LiTaO3 Thin Films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2012, 101, 122902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; Cheng, X.; Hu, X.; Burns, P.A.; Dawes, J.M. Thermal and Laser Properties of Yb:YAl3(BO3)4 Crystal. J. Cryst. Growth 2003, 250, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noda, N.; Ito, S.; Nunome, Y.; Ueki, Y.; Yoshiie, R.; Naruse, I. Volatilization Characteristics of Boron Compounds during Coal Combustion. Proc. Combust. Inst. 2013, 34, 2831–2838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Ai, N.; Lievens, C.; Love, J.; Jiang, S.P. Impact of Volatile Boron Species on the Microstructure and Performance of Nano-Structured (Gd,Ce)O2-Infiltrated (La,Sr)MnO3 Cathodes of Solid Oxide Fuel Cells. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 23, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasi, A.E.; Foreman, M.R.S.J.; Ekberg, C. Organic Telluride Formation from Paint Solvents under Gamma Irradiation. Nucl. Technol. 2022, 208, 1734–1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byer, R.L.; Young, J.F.; Feigelson, R.S. Growth of High-Quality LiNbO3 Crystals from the Congruent Melt. J. Appl. Phys. 1970, 41, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrunik, M.; Majchrowski, A.; Zasada, D.; Chlanda, A.; Szala, M.; Salerno, M. Modified Pechini Synthesis of Bi2ZnB2O7 Nanoparticles. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 725, 587–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piekara, A.; Ko, J.H.; Lee, J.W.; Naqvi, S.F.U.H.; Jankowska-Sumara, I.; Majchrowski, A.; Zasada, D.; Chrunik, M.; Podgórna, M. Effect of Sn Addition on Thermodynamic, Dielectric, Optical, and Acoustic Properties of Lead Hafnate. Phys. Status Solidi A 2020, 217, 1900958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwiazda, M.; Kaushik, A.; Chlanda, A.; Kijeńska-Gawrońska, E.; Jagiełło, J.; Kowiorski, K.; Lipińska, L.; Święszkowski, W.; Bhardwaj, S.K. A Flexible Immunosensor Based on Electrochemically Reduced Graphene Oxide with Au SAM Using Half-Antibody for Collagen Type I Sensing. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 9, 100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowiorski, K.; Heljak, M.; Strojny-Nędza, A.; Bucholc, B.; Chmielewski, M.; Djas, M.; Kaszyca, K.; Zybała, R.; Małek, M.; Swieszkowski, W.; et al. Compositing Graphene Oxide with Carbon Fibers Enables Improved Dynamical Thermomechanical Behavior of Papers Produced at a Large Scale. Carbon 2023, 206, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | SHG [KDP] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Bi3TeBO9 | 20 | [2] |

| Bi3TeBO9 | 20.8 | This work |

| Bi2.985Nd0.015TeBO9 | 24 | |

| Bi2.97Nd0.03TeBO9 | 9.2 | |

| β-BaB2O4 | 4 | [52] |

| γ-Be2BO3F | 1.6 | |

| Bi2ZnOB2O6 | 0.585 | [18] |

| BiB2O4F | 10 | [53] |

| CsLiB6O10 | 2.5 | [54] |

| KBe2BO3F2 | 1.2 | [52] |

| La2CaB10O19 | 2 | [55] |

| LiB3O5 | 3 | [56] |

| NH4B4O6F | 3 | [52] |

| YAl3(BO3)4 | 6.0 | [57] |

| α-BiB3O6 | 8 | [53] |

| δ-BiB3O6:RE3+ | 4–6 | [51] |

| Transition Type | Spectral Range [nm] | Band(s) Detected [nm] | Character |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~800–820 | 800 | Strong | |

| ~740–760 | 744; 752 | Strong | |

| ~680–690 | 686 | Very weak | |

| ~575–590 | 578; 584 | Strong | |

| ~515–530 | 516; 526 | Weak |

| Compound | BTBO (Undoped) | BTBO:Nd3+(0.5%) | BTBO:Nd3+(1.0%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band Gap | 3.43 | 3.46 | 3.15 |

| (±0.03 [eV]) |

| Compound | T [°C] | T [K] | a [Å] | c [Å] | c/a | V [Å3] | Dcryst. [nm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 | 299.15 | 8.7523(1) | 5.8956(1) | 0.67361(1) | 391.11(1) | 59(1) |

| 30 | 303.15 | 8.7525(1) | 5.8956(1) | 0.67359(1) | 391.13(1) | ||

| 40 | 313.15 | 8.7533(1) | 5.8956(1) | 0.67352(1) | 391.20(1) | ||

| 60 | 333.15 | 8.7549(1) | 5.8957(1) | 0.67342(1) | 391.35(1) | ||

| 80 | 353.15 | 8.7563(1) | 5.8956(1) | 0.67329(1) | 391.47(1) | ||

| 100 | 373.15 | 8.7582(1) | 5.8958(1) | 0.67317(1) | 391.65(1) | ||

| 120 | 393.15 | 8.7598(1) | 5.8957(1) | 0.67304(1) | 391.79(1) | ||

| 140 | 413.15 | 8.7615(1) | 5.8958(1) | 0.67292(1) | 391.94(1) | ||

| 160 | 433.15 | 8.7632(1) | 5.8958(1) | 0.67279(1) | 392.10(1) | ||

| 180 | 453.15 | 8.7649(1) | 5.8958(1) | 0.67265(1) | 392.25(1) | ||

| 200 | 473.15 | 8.7667(1) | 5.8959(1) | 0.67253(1) | 392.42(1) | ||

| 220 | 493.15 | 8.7684(1) | 5.8958(1) | 0.67239(1) | 392.57(1) | ||

| Compound | T [°C] | T [K] | a [Å] | c [Å] | c/a | V [Å3] | Dcryst. [nm] |

| 27 | 300.15 | 8.7529(1) | 5.8929(1) | 0.67325(1) | 390.99(1) | 76(1) |

| 32 | 305.15 | 8.7533(1) | 5.8929(1) | 0.67323(1) | 391.02(1) | ||

| 40 | 313.15 | 8.7539(1) | 5.8930(1) | 0.67318(1) | 391.08(1) | ||

| 60 | 333.15 | 8.7554(1) | 5.8931(1) | 0.67307(1) | 391.22(1) | ||

| 80 | 353.15 | 8.7572(1) | 5.8930(1) | 0.67293(1) | 391.38(1) | ||

| 100 | 373.15 | 8.7588(1) | 5.8932(1) | 0.67283(1) | 391.53(1) | ||

| 120 | 393.15 | 8.7604(1) | 5.8932(1) | 0.67271(1) | 391.68(1) | ||

| 140 | 413.15 | 8.7623(1) | 5.8934(1) | 0.67258(1) | 391.86(1) | ||

| 160 | 433.15 | 8.7639(1) | 5.8934(1) | 0.67246(1) | 392.01(1) | ||

| 180 | 453.15 | 8.7657(1) | 5.8935(1) | 0.67233(1) | 392.17(1) | ||

| 200 | 473.15 | 8.7675(1) | 5.8935(1) | 0.67220(1) | 392.34(1) | ||

| 220 | 493.15 | 8.7693(1) | 5.8937(1) | 0.67208(1) | 392.51(1) | ||

| Compound | T [°C] | T [K] | a [Å] | c [Å] | c/a | V [Å3] | Dcryst. [nm] |

| 27 | 300.15 | 8.7520(2) | 5.8913(2) | 0.67313(2) | 390.80(2) | 80(1) |

| 32 | 305.15 | 8.7525(2) | 5.8912(2) | 0.67309(2) | 390.84(2) | ||

| 40 | 313.15 | 8.7532(2) | 5.8914(2) | 0.67306(2) | 390.92(2) | ||

| 60 | 333.15 | 8.7548(2) | 5.8913(2) | 0.67292(2) | 391.04(2) | ||

| 80 | 353.15 | 8.7565(2) | 5.8915(2) | 0.67281(2) | 391.21(2) | ||

| 100 | 373.15 | 8.7582(2) | 5.8916(2) | 0.67269(2) | 391.37(2) | ||

| 120 | 393.15 | 8.7597(2) | 5.8916(2) | 0.67258(2) | 391.51(2) | ||

| 140 | 413.15 | 8.7616(2) | 5.8917(2) | 0.67245(2) | 391.69(2) | ||

| 160 | 433.15 | 8.7632(2) | 5.8918(2) | 0.67233(2) | 391.84(2) | ||

| 180 | 453.15 | 8.7650(2) | 5.8918(2) | 0.67220(2) | 392.00(2) | ||

| 200 | 473.15 | 8.7668(2) | 5.8919(2) | 0.67207(2) | 392.17(2) | ||

| 220 | 493.15 | 8.7686(2) | 5.8920(2) | 0.67194(2) | 392.33(2) |

| Material | Type | TEC [×106/K] (at RT) | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| αa | αb | αc | |||

| Bi3TeBO9 | polycrystalline | 8.53 | - | 0.24 | This work |

| Bi2.985Nd0.015TeBO9 | 8.68 | - | 0.63 | ||

| GdAl3(BO3)4 | single crystalline | 5.30 | - | 18.8 | [90] |

| La2CaB10O19 | 8.64 | 8.39 | 2.27 | [91] | |

| La2CaB10O19:Nd3+ | 8.31 | 4.13 | 2.33 | [92] | |

| LiNbO3 | 19.2 | - | 2.7 | [93] | |

| YAl3(BO3)4:Yb3+ | 1.4–2.0 | - | 8.1–9.7 | [94] | |

| Compound | Theor. [at.%] | EDX exp. [at.%] | (Nd/Bi) Theor. | (Nd/Bi) EDX exp. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nd | Bi | Nd | Bi | |||

| BTBO:Nd3+(0.5%) | 0.1071 | 21.3214 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 13.98 ± 0.38 | 0.0050 | 0.0022 ± 0.0006 |

| BTBO:Nd3+(1.0%) | 0.2143 | 21.2143 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 12.38 ± 0.33 | 0.0101 | 0.0097 ± 0.0015 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chrunik, M.; Bubnov, A.; Minikayev, R.; Lysak, A.; Włodarczyk, D.; Nowicki, M.; Chlanda, A.; Michalska-Domańska, M.; Szczęśniak, B.; Gratzke, M. Influence of the Nd3+ Dopant Content in Bi3TeBO9 Powders on Their Optical Nonlinearity. Materials 2025, 18, 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245545

Chrunik M, Bubnov A, Minikayev R, Lysak A, Włodarczyk D, Nowicki M, Chlanda A, Michalska-Domańska M, Szczęśniak B, Gratzke M. Influence of the Nd3+ Dopant Content in Bi3TeBO9 Powders on Their Optical Nonlinearity. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245545

Chicago/Turabian StyleChrunik, Maciej, Alexej Bubnov, Roman Minikayev, Anastasiia Lysak, Damian Włodarczyk, Marek Nowicki, Adrian Chlanda, Marta Michalska-Domańska, Barbara Szczęśniak, and Mateusz Gratzke. 2025. "Influence of the Nd3+ Dopant Content in Bi3TeBO9 Powders on Their Optical Nonlinearity" Materials 18, no. 24: 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245545

APA StyleChrunik, M., Bubnov, A., Minikayev, R., Lysak, A., Włodarczyk, D., Nowicki, M., Chlanda, A., Michalska-Domańska, M., Szczęśniak, B., & Gratzke, M. (2025). Influence of the Nd3+ Dopant Content in Bi3TeBO9 Powders on Their Optical Nonlinearity. Materials, 18(24), 5545. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245545