Fabrication of Core–Shell Aggregates from Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP): A Modification Strategy for Tailoring Structural and Surface Properties

Highlights

- Optimized synthesis reduced aggregate crushing value by 43.9%.

- Core–shell RAP aggregates were fabricated via cement hydration.

- The method resolves issues such as RAP “pseudo-gradation” and excess fine content.

- It enables high-content RAP use in high-grade pavement layers.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP)

2.1.2. Cement

2.2. Experimental Methods

2.2.1. Preparation of Recycled Aggregates

2.2.2. Face-Centered Central Composite Design (FCCD)

2.2.3. Pavement Performance Study

2.2.4. Morphology and Elemental Analysis

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Optimization of the Preparation Process for Recycled Aggregates

3.1.1. Multi-Objective Response Optimization

3.1.2. Analysis of Influencing Factors on Recycled Aggregate Preparation

3.2. Analysis of the Particle Size Regulation Mechanism

3.3. Analysis of Pavement Performance

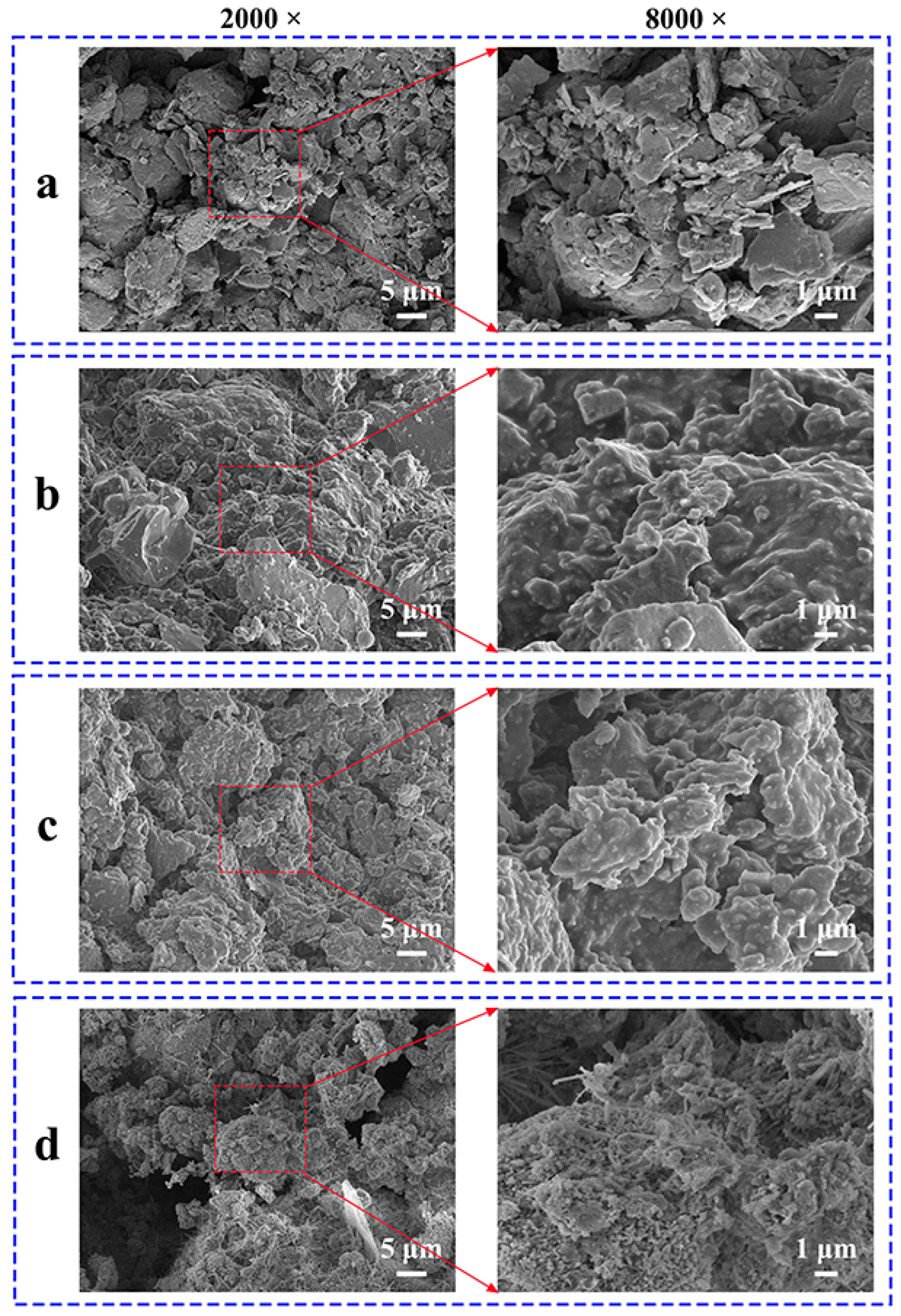

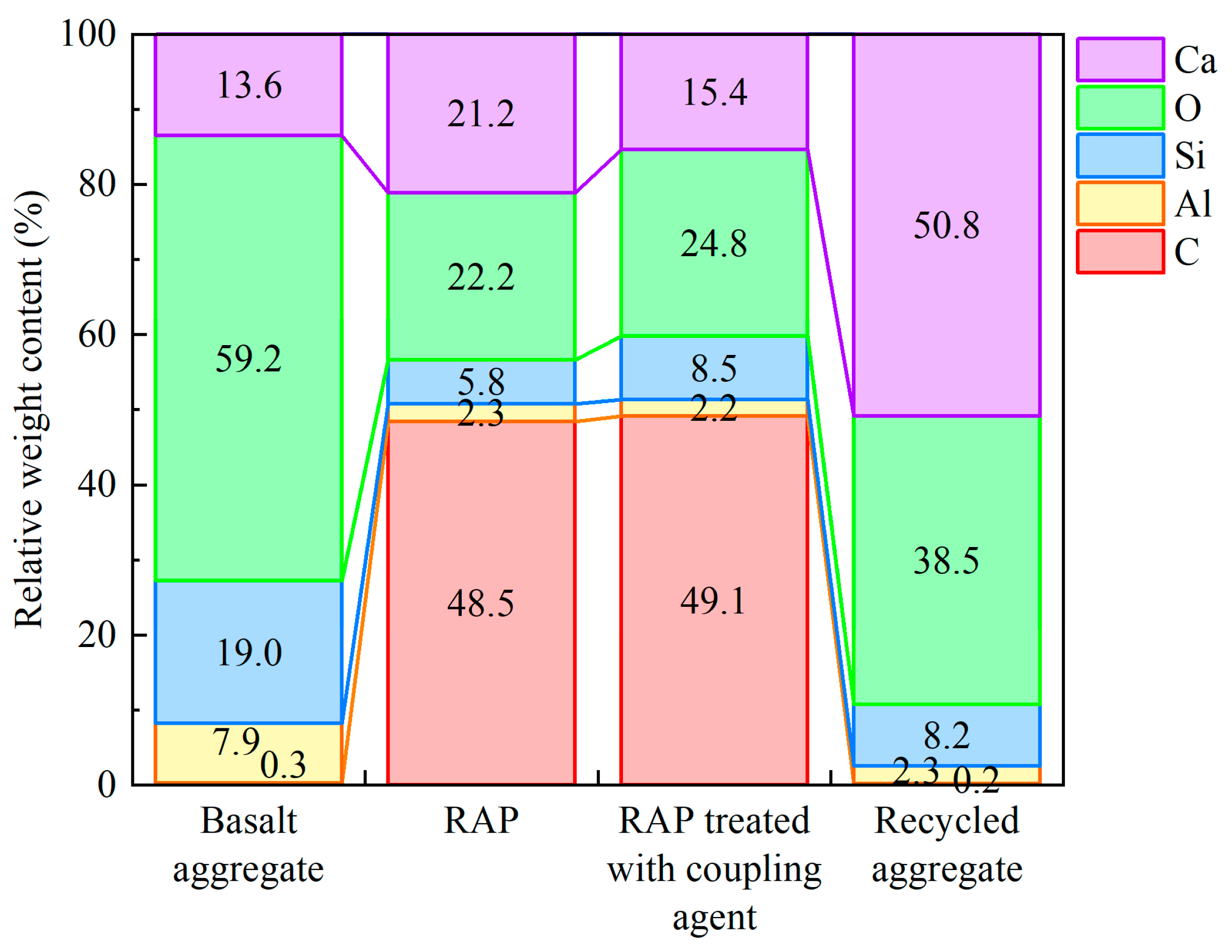

3.4. Surface Characteristics and Elemental Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Sustainability Analysis

4.2. Limitations

4.3. Future Perspectives

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cui, P.; Wu, S.; Xiao, Y.; Hu, R.; Yang, T. Environmental performance and functional analysis of chip seals with recycled basic oxygen furnace slag as aggregate. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 405, 124441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Chen, R.; Jiang, J. Environmental and economic assessment of collective recycling waste plastic and reclaimed asphalt pavement into pavement construction: A case study in Hong Kong. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Chen, A.; Wu, S.; Li, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J. Mechanism of asphalt concrete reinforced with industrially recycled steel slag from the perspectives of adhesion and skeleton. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 424, 135899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariyappan, R.; Palammal, J.S.; Balu, S. Sustainable use of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) in pavement applications—A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 45587–45606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Xu, H.; Wu, S.; Xie, J.; Chen, A.; Lv, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Li, Y. High-quality utilization of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) in asphalt mixture with the enhancement of steel slag and epoxy asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 445, 137963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, S.; Cui, P.; Amirkhanian, S.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L.; Wei, M.; Zhou, X.; Xie, J. Performance characterization and enhancement mechanism of recycled asphalt mixtures involving high RAP content and steel slag. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Xiao, F.; Toraldo, E.; Crispino, M.; Ketabdari, M. Effect of crumb rubber and reclaimed asphalt pavement on viscoelastic property of asphalt mixture. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 428, 139422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Jaber, M.t.; Al-shamayleh, R.A.; Ibrahim, R.; Alkhrissat, T.; Alqatamin, A. Mechanical properties evaluation of asphalt mixtures with variable contents of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Results Eng. 2022, 14, 100463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magar, S.; Xiao, F.; Singh, D.; Showkat, B. Applications of reclaimed asphalt pavement in India—A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Yang, J.; Yu, D.; Jiang, Y.; Ruan, K.; Tao, W.; Sun, C.; Luo, L. Reducing the variability of multi-source reclaimed asphalt pavement materials: A practice in China. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 278, 122389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, H.; Shi, C.; Yang, J. The feasibility of using epoxy asphalt to recycle a mixture containing 100% reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naser, M.; tasim Abdel-Jaber, M.; Al-shamayleh, R.; Louzi, N.; Ibrahim, R. Evaluating the effects of using reclaimed asphalt pavement and recycled concrete aggregate on the behavior of hot mix asphalts. Transp. Eng. 2022, 10, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F.; Xu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Hou, X. Recent applications and developments of reclaimed asphalt pavement in China, 2010–2021. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 37, e00697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, K.; Huang, G.; Shen, Z.; Sun, L. Effect of recycled aggregate gradation on the degree of blending and performance of recycled hot-mix asphalt (HMA). J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 398, 136550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baradaran, S.; Aliha, M.; Maleki, A.; Underwood, B.S. Fracture properties of asphalt mixtures containing high content of reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) and eco-friendly PET additive at low temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 449, 138426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardi, C.; Wang, D.; Wistuba, M.P.; Walther, A. Effects of polyacrylonitrile fibres and high content of RAP on mechanical properties of asphalt mixtures in binder and base layers. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2023, 24, 2133–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, D.B.; Neto, O.d.M.M.; Lucena, L.C.d.F.L.; Lucena, A.E.d.F.L.; Luz, P.M.S.G. Effects of recycling agents and methods on the fracture and moisture resistance of asphalt mixtures with high RAP contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zou, Y.; Airey, G.; Wang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Chen, A. Wetting of bio-rejuvenator nanodroplets on bitumen: A molecular dynamics investigation. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 444, 141140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Gu, X.; Sun, L.; Wang, C. Laboratory evaluation of the performance of reclaimed asphalt mixed with composite crumb rubber-modified asphalt: Reconciling relatively high content of RAP and virgin asphalt. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2217320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhija, M.; Coleri, E. A review on the incorporation of reclaimed asphalt pavement material in asphalt pavements: Management practices and strategic techniques. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 26, 2991–3030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shen, A.; Mou, G.; Guo, Y.; Meiquan, Y. Effect of RAP gradation subdivision and addition of a rejuvenator on recycled asphalt mixture engineering performance. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 18, e02136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.; Shen, Z.; Hao, S.; Du, M.; Hu, J. Mitigating RAP Variability Through Detailed Particle Size Classification: Applications in High RAP Content Asphalt Mixtures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 23, e04993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katla, B.; Raju, S.; Waim, A.R.; Danam, V.A. Utilization of higher percentages of RAP for improved mixture performance by adopting the process of fractionation. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2022, 15, 349–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, G.; Zhou, J.; Guo, P.; Zhao, Y. Optimization of gradation design of recycled asphalt mixtures based on fractal and Mohr-Coulomb theories. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 248, 118649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Tang, W.; Li, N.; Jiang, M.; Huang, J.; Wang, D. Refined decomposition: A new separation method for RAP materials and its effect on aggregate properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 358, 129452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Hao, J. Cold recycled mixtures prepared with finely separated RAP aggregates and modified emulsified asphalt: Adhesive performance and interface fusion characteristics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 493, 143122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, G.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. The effect of refined separation on the properties of reclaimed asphalt pavement materials. Buildings 2024, 14, 1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, D.; Cao, J.; Gao, L.; Yi, J. Recent developments in asphalt-aggregate separation technology for reclaimed asphalt pavement. J. Road Eng. 2022, 2, 332–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Han, Z.; Cheng, H.; Yang, R.; Yuan, J.; Jin, T. Low-temperature performance improvement strategies for high RAP content recycled asphalt mixtures: Focus on RAP gradation variability and mixing process. Fuel 2025, 387, 134362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Wang, H. Study on the mixing process improvement for hot recycled asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 365, 130068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, M.; Nguyen, N.H. Effect of rejuvenator and mixing methods on behaviour of warm mix asphalt containing high RAP content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 197, 792–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Cheng, H.; Sun, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, N. Multi-performance evaluation of recycled warm-mix asphalt mixtures with high reclaimed asphalt pavement contents. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 377, 134209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keymanesh, M.R.; Amani, S.; Omran, A.T.; Karimi, M.M. Evaluation of the impact of long-term aging on fracture properties of warm mix asphalt (WMA) with high RAP contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousefi, A.; Behnood, A.; Nowruzi, A.; Haghshenas, H. Performance evaluation of asphalt mixtures containing warm mix asphalt (WMA) additives and reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP). Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 268, 121200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.-Y.; Sun, L.-J.; Xu, J.-Q.; Li, M.-C.; Xing, C.-W.; Zhang, Y.-N. Effect of RAP’s preheating temperature on the secondary aging and performance of recycled asphalt mixtures containing high RAP content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Feng, J.; Wang, F.; Wu, S.; Xu, H. Advanced and sustainable approach for large-scale, high-quality recycling of predominant pavement waste and its life cycle environmental impact assessment. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2026, 118, 108263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Yang, R.; Yang, J.; Fan, Y.; Liu, Y.; Tan, J. Effect of degree of blending on the fatigue performance of epoxy-recycled mixtures with high reclaimed asphalt pavement (RAP) content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 489, 142227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, S.; Yang, C.; Xie, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, L. Quantitative assessment of road performance of recycled asphalt mixtures incorporated with steel slag. Materials 2022, 15, 5005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez, D.B.; Caro, S.; Alvarez, A.E. Assessment of methods to select optimum doses of rejuvenators for asphalt mixtures with high RAP content. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2161544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Q.; Wu, S.; Gan, Y.; Zhang, L.; Liu, L.; Zhang, S.; Lu, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, C. Identification of characteristic components of waste tire pyrolysis oil and interfacial diffusion behavior in the rejuvenation of aged asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 501, 144287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, W.; Wu, W.; Yang, W.; Fan, X. Research on the Performance of Ultra-High-Content Recycled Asphalt Mixture Based on Fine Separation Technology. Materials 2025, 18, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- JTG/T 5521-2019; Technical Specifications for Highway Asphalt Pavement Recycling. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2019.

- ASTM D2216; Standard Test Method for Laboratory Determination of Water (Moisture) Content of Soil and Rock by Mass. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM D2419; Standard Test Method for Sand Equivalent Value of Soils and Fine Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ASTM D2172; Standard Test Methods for Quantitative Extraction of Asphalt Binder from Asphalt Mixtures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM D5444; Standard Test Method for Mechanical Size Analysis of Extracted Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- ASTM C128; Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Fine Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2025.

- ASTM C127; Standard Test Method for Relative Density (Specific Gravity) and Absorption of Coarse Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- JTG F40-2004; Technical Specifications for Construction of Highway Asphalt Pavements. China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2004.

- ASTM D5; Standard Test Method for Penetration of Bituminous Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D36; Standard Test Method for Softening Point of Bitumen (Ring-and-Ball Apparatus). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D113; Standard Test Method for Ductility of Asphalt Materials. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- BS 812-110; Testing Aggregates—Part 110: Methods for Determination of Aggregate Crushing Value (ACV). British Standards Institution: London, UK, 1998.

- ASTM C131; Standard Test Method for Resistance to Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ASTM D4791; Standard Test Method for Flat Particles, Elongated Particles, or Flat and Elongated Particles in Coarse Aggregate. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- GB 175-2023; General Purpose Portland Cement. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Gan, Y.; Li, C.; Ke, W.; Deng, Q.; Yu, T. Study on pavement performance of steel slag asphalt mixture based on surface treatment. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 16, e01131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 12697-22:2020; Bituminous mixtures-Test methods—Part 22: Wheel tracking. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

- EN 12697-46:2020; Bituminous mixtures-Test methods—Part 46: Low temperature cracking and properties by uniaxial tension tests. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2020.

| Test Item | Measured Value | Technical Requirements (JTG/T 5521-2019 [42]) | Test Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture content (%) | 0.81 | ≤3 | ASTM D2216 [43] | |

| Sand equivalent | 69 | ≥60 | ASTM D2419 [44] | |

| 0–5 mm | Asphalt content (%) | 5.92 | - | ASTM D2172 [45] |

| Mineral filler content (%) | 8.14 | - | ASTM D5444 [46] | |

| Apparent specific gravity | 2.33 | - | ASTM C128 [47] | |

| 5–15 mm | Asphalt content (%) | 3.51 | - | ASTM D2172 |

| Mineral filler content (%) | 1.41 | - | ASTM D5444 | |

| Apparent specific gravity | 2.48 | - | ASTM C127 [48] | |

| Test Item | Measured Value | Technical Requirements (JTG F40-2004 [49], SBS I-D) | Test Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Penetration (0.1 mm) | 34.4 | 40~60 | ASTM D5 [50] |

| Softening point (°C) | 76.5 | ≥60 | ASTM D36 [51] |

| Ductility at 15 °C (cm) | 32.8 | - | ASTM D113 [52] |

| Ductility at 5 °C (cm) | 8.4 | ≥20 | ASTM D113 |

| Test Item | Measured Value | Technical Requirements (JTG F40-2004, Expressway Surface Layer) | Test Method | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crushing value (%) | 22.3 | ≤26 | BS 812-110 [53] | |

| Los Angeles abrasion loss (%) | 13.5 | ≤28 | ASTM C131 [54] | |

| Flat and elongated particles (%) | 5.7 | ≤15 | ASTM D4791 [55] | |

| 0–5 mm | Apparent specific gravity | 2.69 | ≥2.50 | ASTM C128 |

| 5–15 mm | Apparent specific gravity | 2.67 | ≥2.60 | ASTM C127 |

| Test Item | PS.A 32.5 | PO 42.5 | PO 52.5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| SO3 (%) | 2.23 | 2.12 | 1.98 |

| Cl-content (%) | 0.035 | 0.015 | 0.046 |

| True density (g/cm3) | 3.148 | 3.155 | 3.153 |

| Fineness (>0.08 mm) (%) | 2.6 | 1.8 | 2.5 |

| Initial setting time (min) | 225 | 186 | 182 |

| Final setting time (min) | 248 | 234 | 304 |

| 3d flexural strength (MPa) | 3.1 | 3.6 | 6.2 |

| 3d compressive strength (MPa) | 15.2 | 21.3 | 31.2 |

| 28d flexural strength (MPa) | 6.2 | 8.3 | 9.4 |

| 28d compressive strength (MPa) | 38.8 | 49.1 | 61.4 |

| Factors | Code | Unit | Low Level | Medium Level | High Level | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variables | Cement strength grade | A | MPa | 32.5 | 42.5 | 52.5 |

| Water–cement ratio | B | - | 0.3 | 0.4 | 0.5 | |

| Paste–RAP ratio | C | - | 0.2 | 0.25 | 0.3 | |

| Response variables | Crushing value | CV | % | - | - | - |

| Apparent specific gravity | ASG | - | - | - | - | |

| Water absorption | WA | % | - | - | - | |

| Run | Cement Compressive Strength (MPa) | Water–Cement Ratio | Paste–RAP Ratio | Crushing Value (%) | Apparent Specific Gravity | Water Absorption (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 32.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 18.15 | 2.53 | 2.34 |

| 2 | 52.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 14.21 | 2.59 | 2.14 |

| 3 | 32.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 17.62 | 2.61 | 1.23 |

| 4 | 52.5 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 16.43 | 2.54 | 1.75 |

| 5 | 32.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 18.92 | 2.55 | 2.55 |

| 6 | 52.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 15.06 | 2.58 | 2.20 |

| 7 | 32.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 20.45 | 2.51 | 3.26 |

| 8 | 52.5 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 16.97 | 2.49 | 2.39 |

| 9 | 32.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 16.82 | 2.58 | 2.25 |

| 10 | 52.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 12.74 | 2.58 | 2.16 |

| 11 | 42.5 | 0.3 | 0.25 | 13.68 | 2.61 | 3.15 |

| 12 | 42.5 | 0.5 | 0.25 | 13.11 | 2.60 | 3.24 |

| 13 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 16.13 | 2.61 | 2.84 |

| 14 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 16.79 | 2.60 | 3.24 |

| 15 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 16.23 | 2.65 | 3.12 |

| 16 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 15.12 | 2.63 | 2.74 |

| 17 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 14.28 | 2.66 | 3.25 |

| 18 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 13.55 | 2.65 | 2.99 |

| 19 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 15.31 | 2.69 | 2.69 |

| 20 | 42.5 | 0.4 | 0.25 | 14.63 | 2.66 | 3.03 |

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 62.49 | 3 | 20.83 | 21.64 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A-Cement strength grade | 27.39 | 1 | 27.39 | 28.46 | <0.0001 | significant |

| C-Paste–RAP ratio | 3.19 | 1 | 3.19 | 3.32 | 0.0873 | not significant |

| C2 | 31.90 | 1 | 31.90 | 33.15 | <0.0001 | significant |

| Residual | 15.40 | 16 | 0.9624 | |||

| Lack of fit | 11.15 | 11 | 1.01 | 1.19 | 0.4511 | not significant |

| Pure error | 4.25 | 5 | 0.8504 | |||

| Corrected total | 77.88 | 19 | ||||

| R2 | 0.8023 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 0.0498 | 8 | 0.0062 | 13.29 | 0.0001 | significant |

| A-Cement strength grade | 9 × 10−7 | 1 | 9 × 10−7 | 0.0019 | 0.9658 | not significant |

| B-Water–cement ratio | 0.0017 | 1 | 0.0017 | 3.66 | 0.0820 | not significant |

| C-Paste–RAP ratio | 0.0021 | 1 | 0.0021 | 4.55 | 0.0563 | not significant |

| AB | 0.0037 | 1 | 0.0037 | 7.89 | 0.0170 | significant |

| BC | 0.0034 | 1 | 0.0034 | 7.18 | 0.0214 | significant |

| A2 | 0.0063 | 1 | 0.0063 | 13.48 | 0.0037 | significant |

| B2 | 0.0020 | 1 | 0.0020 | 4.25 | 0.0637 | not significant |

| C2 | 0.0021 | 1 | 0.0021 | 4.41 | 0.0596 | not significant |

| Residual | 0.0052 | 11 | 0.0005 | |||

| Lack of fit | 0.0033 | 6 | 0.0006 | 1.49 | 0.3401 | not significant |

| Pure error | 0.0019 | 5 | 0.0004 | |||

| Corrected total | 0.0550 | 19 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9062 | |||||

| Source | Sum of Squares | Degrees of Freedom | Mean Square | F-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | 5.47 | 6 | 0.9120 | 20.23 | <0.0001 | significant |

| A-Cement strength grade | 0.0980 | 1 | 0.0980 | 2.17 | 0.1642 | not significant |

| B-Water–cement ratio | 0.0260 | 1 | 0.0260 | 0.5769 | 0.4611 | not significant |

| C-Paste–RAP ratio | 1.12 | 1 | 1.12 | 24.74 | 0.0003 | significant |

| AC | 0.2965 | 1 | 0.2965 | 6.58 | 0.0235 | significant |

| BC | 0.7200 | 1 | 0.7200 | 15.97 | 0.0015 | significant |

| A2 | 3.22 | 1 | 3.22 | 71.34 | <0.0001 | significant |

| Residual | 0.5861 | 13 | 0.0451 | |||

| Lack of fit | 0.3499 | 8 | 0.0437 | 0.9258 | 0.5618 | not significant |

| Pure error | 0.2362 | 5 | 0.0472 | |||

| Corrected total | 6.06 | 19 | ||||

| R2 | 0.9033 | |||||

| Value | Cement Strength Grade (MPa) | Water–Cement Ratio | Paste–RAP Ratio | Crushing Value (%) | Apparent Specific Gravity | Water Absorption (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicted | 49.3 | 0.365 | 0.241 | 13.40 | 2.63 | 2.59 |

| Actual | 52.5 | 0.365 | 0.241 | 12.53 | 2.62 | 1.99 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, Q.; Deng, Q.; Wu, S.; Liu, A.; Xia, G. Fabrication of Core–Shell Aggregates from Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP): A Modification Strategy for Tailoring Structural and Surface Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245542

Chen Q, Deng Q, Wu S, Liu A, Xia G. Fabrication of Core–Shell Aggregates from Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP): A Modification Strategy for Tailoring Structural and Surface Properties. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245542

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Qingsong, Qinhao Deng, Shaopeng Wu, An Liu, and Guoxin Xia. 2025. "Fabrication of Core–Shell Aggregates from Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP): A Modification Strategy for Tailoring Structural and Surface Properties" Materials 18, no. 24: 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245542

APA StyleChen, Q., Deng, Q., Wu, S., Liu, A., & Xia, G. (2025). Fabrication of Core–Shell Aggregates from Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement (RAP): A Modification Strategy for Tailoring Structural and Surface Properties. Materials, 18(24), 5542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245542