The Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Crowns: An In Vitro Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Setting, Study Group, and Sample Size Calculation

- (1)

- Plastic scaler: a plastic tip composed of Plasteel, a high-grade unfilled resin (Implacare II LG1/2, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co., Chicago, IL, USA).

- (2)

- Hand scaler: a stainless-steel metal tip (H3/H4 Jacquette Scaler, Hu-Friedy Mfg. Co., Chicago, IL, USA).

- (3)

- Ultra-sonic scaler: a piezoelectric scaler tip (Piezo Scaler Tip 201, KaVo PiezoLED Ultraschall Scaler, Kaltenbach & Voigt GmbH, Biberach, Germany).

2.2. Sample Preparation

2.3. Surface Roughness Assessment

2.4. Scaling Methods and Calculating the Change in the Average Surface Roughness

2.5. Statistical Analysis

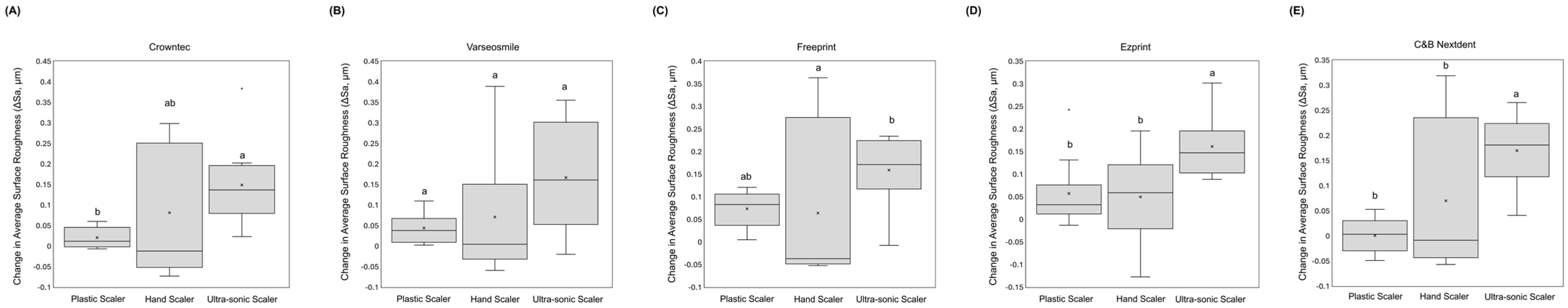

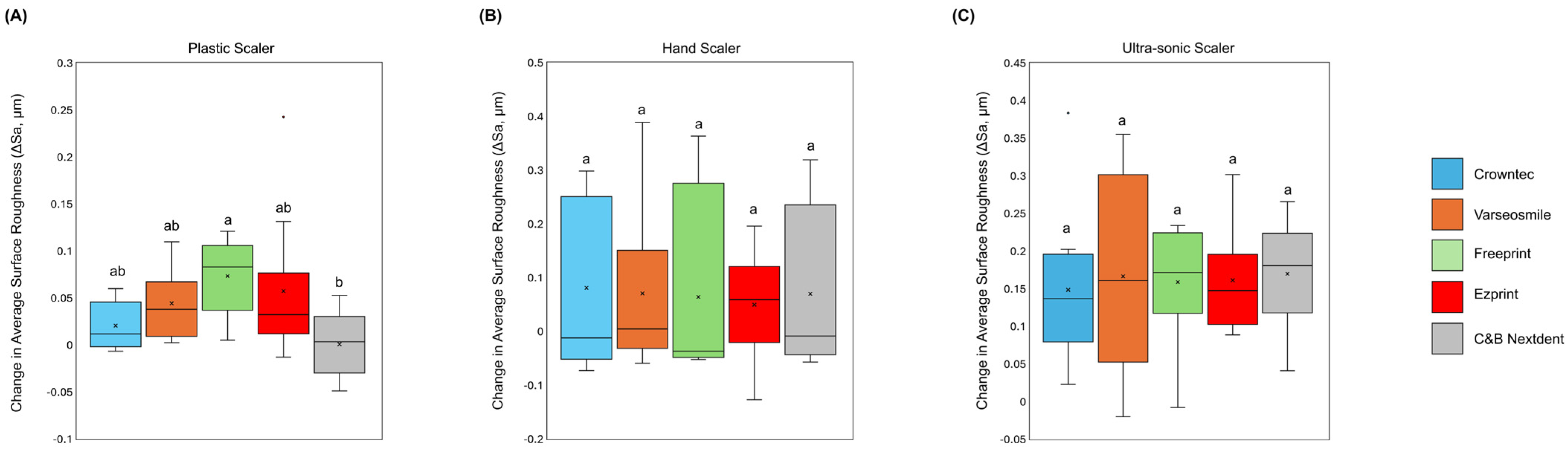

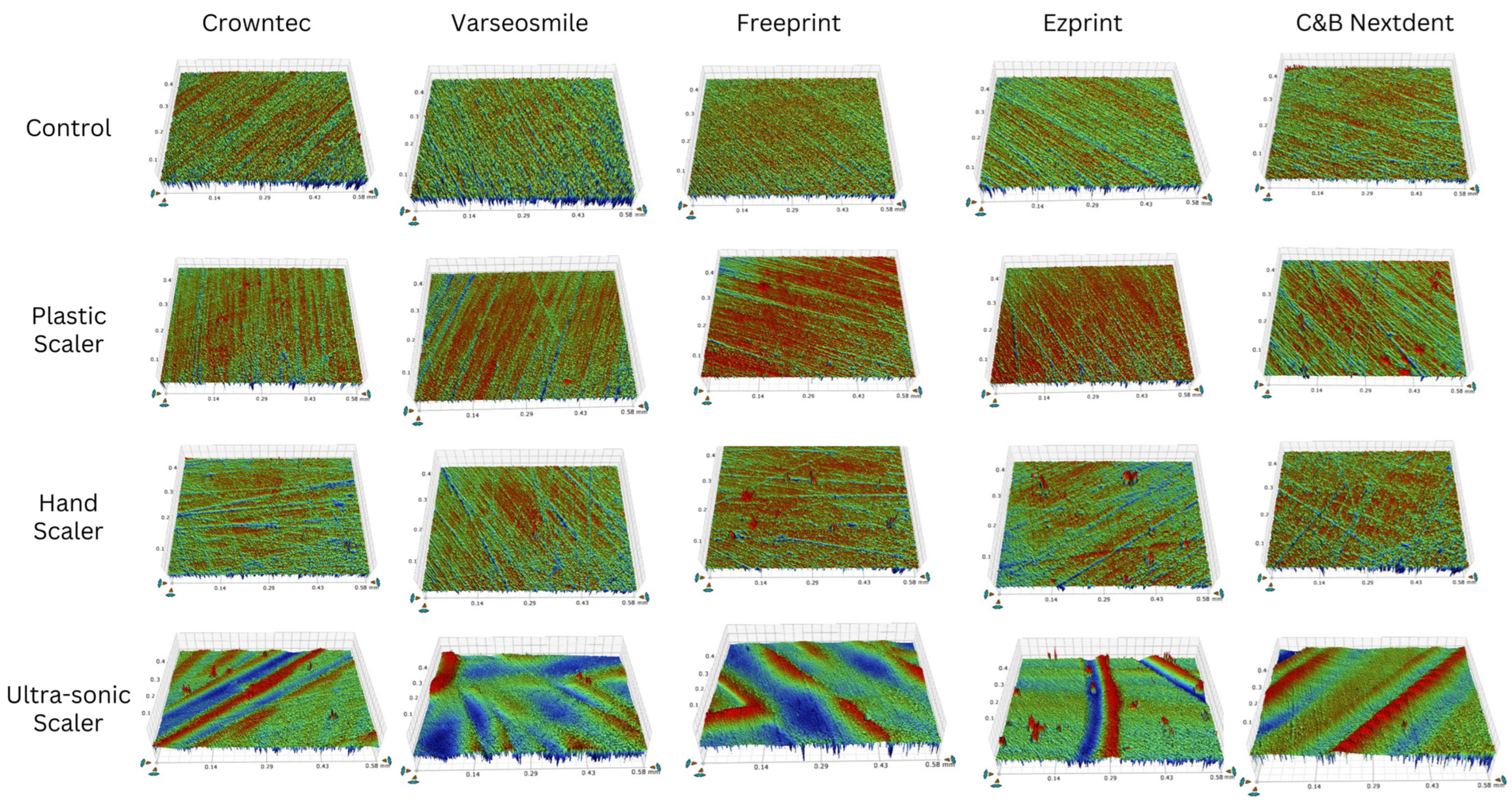

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ganguly, S.; Tang, X.S. 3D Printing of High Strength Thermally Stable Sustainable Lightweight Corrosion-Resistant Nanocomposite by Solvent Exchange Postprocessing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, T.; Zhang, Y.; Ruan, K.; Guo, H.; He, M.; Shi, X.; Guo, Y.; Kong, J.; Gu, J. Advances in 3D Printing for Polymer Composites: A Review. InfoMat 2024, 6, e12568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P.; Fouda, S.M.; Mahrous, A.A.; AlGhamdi, M.A.; Aly, N.M. Influence of CAD/CAM Milling and 3D-Printing Fabrication Methods on the Mechanical Properties of 3-Unit Interim Fixed Dental Prosthesis after Thermo-Mechanical Aging Process. Polymers 2022, 14, 4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Garcia, I.M.; Mokeem, L.; Alsahafi, R.; Majeed-Saidan, A.; Albagami, H.H.; Khan, A.S.; Ahmad, S.; Collares, F.M.; Della Bona, A.; et al. Three-Dimensional (3D) Printing in Dental Practice: Applications, Areas of Interest, and Level of Evidence. Clin. Oral Investig. 2023, 27, 2465–2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, A.; Hickel, R.; Reymus, M. 3D Printing in Dentistry-State of the Art. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Jang, Y.J.; Koh, M.; Choi, B.-K.; Kim, K.-K.; Ko, Y. In Vitro Analysis of the Efficacy of Ultrasonic Scalers and a Toothbrush for Removing Bacteria from Resorbable Blast Material Titanium Disks. J. Periodontol. 2013, 84, 1191–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.H.; Kim, S.H.; Han, J.S.; Yeo, I.S.L.; Yoon, H.I.; Lee, J. Effects of Ultrasonic Scaling on the Optical Properties and Surface Characteristics of Highly Translucent CAD/CAM Ceramic Restorative Materials: An in Vitro Study. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 14594–14601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.-B.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, N.; Park, S.; Jin, S.-H.; Choi, B.-K.; Kim, K.-K.; Ko, Y. Instrumentation with Ultrasonic Scalers Facilitates Cleaning of the Sandblasted and Acid-Etched Titanium Implants. J. Oral. Implantol. 2015, 41, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkala, P.; Munnangi, S.R.; Bandari, S.; Repka, M. Additive Manufacturing Technologies with Emphasis on Stereolithography 3D Printing in Pharmaceutical and Medical Applications: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. X 2023, 5, 100159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unkovskiy, A.; Schmidt, F.; Beuer, F.; Li, P.; Spintzyk, S.; Kraemer Fernandez, P. Stereolithography vs. Direct Light Processing for Rapid Manufacturing of Complete Denture Bases: An In Vitro Accuracy Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlQranei, M.S.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Melo, M.A.S. The Burden of Root Caries: Updated Perspectives and Advances on Management Strategies. Gerodontology 2021, 38, 136–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hossam, A.E.; Rafi, A.T.; Ahmed, A.S.; Sumanth, P.C. Surface Topography of Composite Restorative Materials Following Ultrasonic Scaling and Its Impact on Bacterial Plaque Accumulation. An in-Vitro SEM Study. J. Int. Oral Health 2013, 5, 13–19. [Google Scholar]

- Quirynen, M.; Bollen, C.M. The Influence of Surface Roughness and Surface-Free Energy on Supra- and Subgingival Plaque Formation in Man. A Review of the Literature. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1995, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Grover, V.; Satpathy, A.; Jain, A.; Grover, H.S.; Khatri, M.; Kolte, A.; Dani, N.; Melath, A.; Chahal, G.S.; et al. ISP Good Clinical Practice Recommendations for Gum Care. J. Indian Soc. Periodontol. 2023, 27, 4–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande, F.; Mochi Zamperoli, E.; Pozzan, M.C.; Tesini, F.; Catapano, S. Qualitative Evaluation of the Effects of Professional Oral Hygiene Instruments on Prosthetic Ceramic Surfaces. Materials 2021, 15, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellakany, P.; Aly, N.M.; Alghamdi, M.M.; Alameer, S.T.; Alshehri, T.; Akhtar, S.; Madi, M. Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Topography of Different CAD/CAM Ceramic Compositions. Materials 2023, 16, 2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabaci, T.; Ciçek, Y.; Canakçi, C.F. Sonic and Ultrasonic Scalers in Periodontal Treatment: A Review. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2007, 5, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, T.T.; Oztekin, F.; Keklik, E.; Tozum, M.D. Surface Roughness of Enamel and Root Surface after Scaling, Root Planning and Polishing Procedures: An in-Vitro Study. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2021, 11, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babina, K.; Polyakova, M.; Sokhova, I.; Doroshina, V.; Arakelyan, M.; Zaytsev, A.; Novozhilova, N. The Effect of Ultrasonic Scaling and Air-Powder Polishing on the Roughness of the Enamel, Three Different Nanocomposites, and Composite/Enamel and Composite/Cementum Interfaces. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mourouzis, P.; Koulaouzidou, E.A.; Vassiliadis, L.; Helvatjoglu-Antoniades, M. Effects of Sonic Scaling on the Surface Roughness of Restorative Materials. J. Oral Sci. 2009, 51, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checketts, M.R.; Turkyilmaz, I.; Asar, N.V. An Investigation of the Effect of Scaling-Induced Surface Roughness on Bacterial Adhesion in Common Fixed Dental Restorative Materials. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2014, 112, 1265–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Al Otaibi, A.M.; Alotaibi, K.S.; Al-Zain, A.O.; Ismail, E.H.; Al-Dulaijan, Y.A.; Alalawi, H.; Al-Thobity, A.M. The Impact of Streptococcus Mutans Biofilms on the Color Stability and Topographical Features of Three Lithium Disilicate Ceramics. J. Prosthodont. 2024. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Garcia, I.M.; Collares, F.M.; Weir, M.D.; Xu, H.H.; Melo, M.A.S. Pronounced Effect of Antibacterial Bioactive Dental Composite on Microcosm Biofilms Derived from Patients with Root Carious Lesions. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 583861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktug Karademir, S.; Atasoy, S.; Akarsu, S.; Karaaslan, E. Effects of Post-Curing Conditions on Degree of Conversion, Microhardness, and Stainability of 3D Printed Permanent Resins. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGhamdi, M.A.; Fouda, S.M.; Al-Dulaijan, Y.A.; Khan, S.Q.; El Zayat, M.; Al Munif, R.; Albazroun, Z.; Amer, F.H.; Al Ammary, A.T.; Mahrous, A.A.; et al. Nanocomposite 3D Printed Resins Containing Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) Nanoparticles: An in Vitro Analysis of Color, Hardness, and Surface Roughness Properties. Front. Dent. Med. 2025, 6, 1581461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, J.-S.; Kim, J.-Y.; Mangal, U.; Seo, J.-Y.; Lee, M.-J.; Jin, J.; Yu, J.-H.; Choi, S.-H. Durable Oral Biofilm Resistance of 3D-Printed Dental Base Polymers Containing Zwitterionic Materials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsubaie, T.; Alhebshi, R.A.; Khan, A.S.; Gad, M.M.; Balhaddad, A.A.; Alalawi, H. High-Speed Sintering on Monolithic Zirconia: Effects on Surface and Antagonist Wear in Vitro. J. Prosthodont. 2025. before inlusion in an issue. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellakany, P.; Madi, M.; Aly, N.M.; Alshehri, T.; Alameer, S.T.; Al-Harbi, F.A. Influences of Different CAD/CAM Ceramic Compositions and Thicknesses on the Mechanical Properties of Ceramic Restorations: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2023, 16, 646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, G.; Macedo, P.D.; Tsurumaki, J.N.; Sampaio, J.E.; Marcantonio, R. The Effect of the Angle of Instrumentation of the Piezoelectric Ultrasonic Scaler on Root Surfaces. Int. J. Dent. Hyg. 2016, 14, 184–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, K.; Nakamura, K.; Harada, A.; Shirato, M.; Inagaki, R.; Örtengren, U.; Kanno, T.; Niwano, Y.; Egusa, H. Surface Properties of Dental Zirconia Ceramics Affected by Ultrasonic Scaling and Low-Temperature Degradation. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoi, P.R.; Badole, G.P.; Khode, R.T.; Morey, E.S.; Singare, P.G. Evaluation of Effect of Ultrasonic Scaling on Surface Roughness of Four Different Tooth-Colored Class V Restorations: An in-Vitro Study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2014, 17, 471–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrali, O.B. Roughness Impact of Piezoelectric Dental Scaler on Two Distinct Flowable Composite Filling Materials. J. Vis. Exp. 2025, 215, e67446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seol, H.-W.; Heo, S.-J.; Koak, J.-Y.; Kim, S.-K.; Baek, S.-H.; Lee, S.-Y. Surface Alterations of Several Dental Materials by a Novel Ultrasonic Scaler Tip. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2012, 27, 801–810. [Google Scholar]

- Bidra, A.S.; Daubert, D.M.; Garcia, L.T.; Kosinski, T.F.; Nenn, C.A.; Olsen, J.A.; Platt, J.A.; Wingrove, S.S.; Chandler, N.D.; Curtis, D.A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Recall and Maintenance of Patients with Tooth-Borne and Implant-Borne Dental Restorations. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25 (Suppl. S1), S32–S40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, H.S.; Ali, A.I.; Garcia-Godoy, F. Influence of Manual and Ultrasonic Scaling on Surface Roughness of Four Different Base Materials Used to Elevate Proximal Dentin-Cementum Gingival Margins: An In Vitro Study. Oper. Dent. 2022, 47, E106–E118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unursaikhan, O.; Lee, J.-S.; Cha, J.-K.; Park, J.-C.; Jung, U.-W.; Kim, C.-S.; Cho, K.-S.; Choi, S.-H. Comparative Evaluation of Roughness of Titanium Surfaces Treated by Different Hygiene Instruments. J. Periodontal Implant. Sci. 2012, 42, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balhaddad, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.S.; Weir, M.D.; Xu, H.H.K.; Melo, M.A.S. Concentration Dependence of Quaternary Ammonium Monomer on the Design of High-Performance Bioactive Composite for Root Caries Restorations. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, e266–e278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kara, D.; Tekçe, N.; Fidan, S.; Demirci, M.; Tuncer, S.; Balcı, S. The Effects of Various Polishing Procedures on Surface Topography of CAD/CAM Resin Restoratives. J. Prosthodont. 2021, 30, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daghrery, A. Color Stability, Gloss Retention, and Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed versus Indirect Prefabricated Veneers. J. Funct. Biomater. 2023, 14, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Crowntec | Varseosmile | Freeprint | EZprint | C&B Nextdent | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Saremco Dental, Rebstein, Switzerland | BEGO Bremer Goldschlägerei Wilh. Herbst, Bremen, Germany | DETAX, Ettlingen, Germany | Aidite (Qinhuangdao) Technology (Qinhuangdao, China) | Nextdent (Soesterberg, The Netherlands) |

| Composition | 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol (ethoxylated) and 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid (i.e., methacrylic-acid-ester-based resin), silanized dental glass fillers, and pyrogenic silica (inorganic fillers ~30–50% by mass, particle size ~0.7 µm), plus photoinitiators/initiators | Methacrylate-based composite resin composed of esterification products of 4,4′-isopropylidenediphenol (ethoxylated) and 2-methylprop-2-enoic acid, with silanized dental glass fillers (≈30–50 wt.%, ~0.7 μm), and a photoinitiator system containing diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide and methyl benzoylformate; minor pigments such as titanium dioxide and iron oxides are included | Methacrylate-based permanent crown resin composed primarily of an alkoxylated phenol derivative, methacrylate-terminated (≈40–<60 wt.%), combined with 7,7,9-trimethyl-4,13-dioxo-3,14-dioxa-5,12-diazahexadecane-1,16-diyl bismethacrylate (≈5–<20 wt.%), and 1,6-hexanediol dimethacrylate (≈5–<20 wt.%); minor monomeric components include hydroxypropyl methacrylate (≈0.1–<5 wt.%); the photoinitiation system consists of diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide and phenyl-bis(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (each ≈0.1–<5 wt.%) | Not available | Bisphenol-A ethoxylated dimethacrylate (Bis-EMA ≥50–<70 wt.%) and Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate (TEGDMA ≥10–<20 wt%), with Diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)phosphine oxide (TPO ≥0.1–<1 wt.%) as the photoinitiator |

| Layer thickness | 50 µm | 50 µm | 50 µm | 50 µm | 50 µm |

| Printing technology | LED-based digital light processing (DLP) | LED-based digital light processing (DLP) | LED-based digital light processing (DLP) | LED-based digital light processing (DLP) | Digital light processing (DLP) |

| Printing orientation | 0 degree | 0 degree | 0 degree | 0 degree | 0 degree |

| Cleaning protocol | Immersed in isopropyl alcohol 99.9% liquid (Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), then dried with air | Immersed in isopropyl alcohol 99.9% liquid (Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), then dried with air | Immersed in isopropyl alcohol 99.9% liquid (Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), then dried with air | Immersed in isopropyl alcohol 99.9% liquid (Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), then dried with air | Immersed in isopropyl alcohol 99.9% liquid (Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), then dried with air |

| Printer | Asiga Max, technology: DLP wavelength 385 nm (ASIGA, Sydney, Australia) | Asiga Max, technology: DLP wavelength 385 nm (ASIGA, Sydney, Australia) | Asiga Max, technology: DLP wavelength 385 nm (ASIGA, Sydney, Australia) | Asiga Max, technology: DLP wavelength 385 nm (ASIGA, Sydney, Australia) | NextDent 5100 printer, technology: DLP wavelength 405 nm (NextDent 5100 printer, Nextdent B.V., Soesterberg, The Netherlands) |

| Curing process, time, and temperature | Asiga® Flash Cure Box (Asiga, Sydney, Australia) for 30 min (15 min for each surface) at 60 °C curing temperature | Asiga® Flash Cure Box (Asiga, Sydney, Australia) for 30 min (15 min for each surface) at 60 °C curing temperature | Asiga® Flash Cure Box (Asiga, Sydney, Australia) for 30 min (15 min for each surface) at 60 °C curing temperature | Asiga® Flash Cure Box (Asiga, Sydney, Australia) for 30 min (15 min for each surface) at 60 °C curing temperature | LC-3DPrint Box (3D Systems Corporation, Rock Hill, SC, USA) for 30 min (15 min for each surface) at 60 °C curing temperature |

| Storage condition | After printing, stored at room temperature away from bright light | After printing, stored at room temperature away from bright light | After printing, stored at room temperature away from bright light | After printing, stored at room temperature away from bright light | After printing, stored at room temperature away from bright light |

| Plastic Scaler | Hand Scaler | Ultra-Sonic Scaler | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crowntec | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 0.20 ± 0.02 b | 0.22 ± 0.01 a | 0.30 ± 0.15 a | 0.14 ± 0.01 a | 0.29 ± 0.10 b |

| Varseosmile | 0.15 ± 0.02 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 b | 0.20 ± 0.02 a | 0.27 ± 0.16 a | 0.16 ± 0.02 a | 0.32 ± 0.13 b |

| Freeprint | 0.17 ± 0.02 a | 0.24 ± 0.04 b | 0.18 ± 0.03 a | 0.24 ± 0.17 a | 0.18 ± 0.02 a | 0.33 ± 0.07 b |

| Ezprint | 0.22 ± 0.02 a | 0.27 ± 0.07 b | 0.19 ± 0.04 a | 0.24 ± 0.08 a | 0.16 ± 0.02 a | 0.32 ± 0.06 b |

| C&B Nextdent | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | 0.19 ± 0.03 a | 0.22 ± 0.02 a | 0.29 ± 0.15 a | 0.15 ± 0.03 a | 0.33 ± 0.07 b |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alshehri, T.; Albishri, D.; Alsayoud, A.M.; Alanazi, A.; Masaud, F.; Howsawi, A.A.; Balhaddad, A.A. The Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Crowns: An In Vitro Study. Materials 2025, 18, 5525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245525

Alshehri T, Albishri D, Alsayoud AM, Alanazi A, Masaud F, Howsawi AA, Balhaddad AA. The Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Crowns: An In Vitro Study. Materials. 2025; 18(24):5525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245525

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlshehri, Turki, Dhai Albishri, Aminah M. Alsayoud, Abdulkarim Alanazi, Faisal Masaud, Anas A. Howsawi, and Abdulrahman A. Balhaddad. 2025. "The Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Crowns: An In Vitro Study" Materials 18, no. 24: 5525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245525

APA StyleAlshehri, T., Albishri, D., Alsayoud, A. M., Alanazi, A., Masaud, F., Howsawi, A. A., & Balhaddad, A. A. (2025). The Effect of Different Scaling Methods on the Surface Roughness of 3D-Printed Crowns: An In Vitro Study. Materials, 18(24), 5525. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18245525