3.1. Characterization of Solution-Treated Ti50Ni41Cu7Co2 SMA

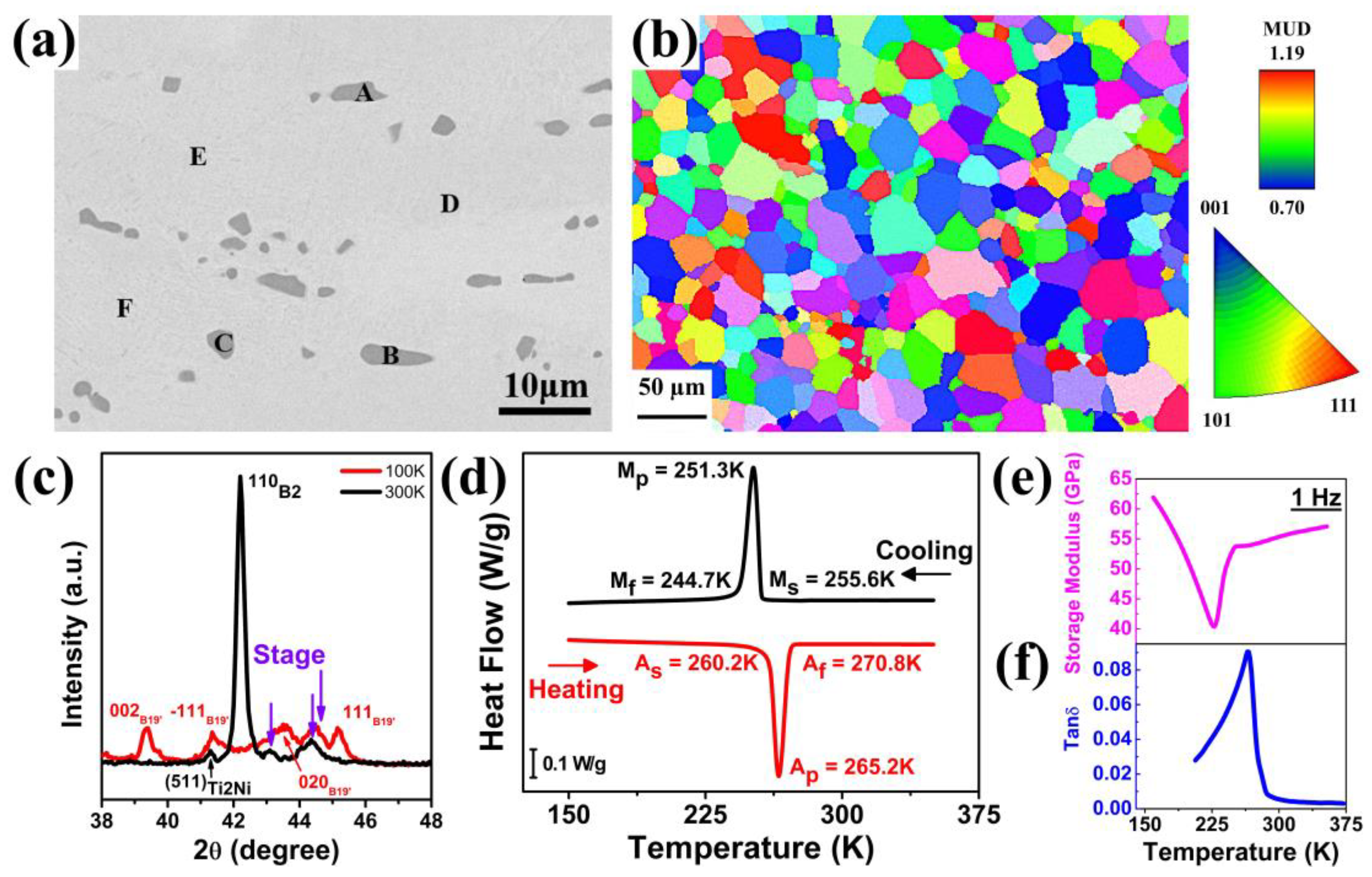

Figure 1a shows the SEM backscattered electron image of Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 after solution treatment at 1173 K for an hour. The compositions at different locations were analyzed by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) and are presented in

Table 1. The dark gray precipitates have an average composition of 65.3 at. % Ti, 29.1 at. % Ni, 4.8 at. % Cu, and 0.8 at. % Co while an average composition of base matrix is 49.0 at. % Ti, 40.2 at. % Ni, 8.9 at. % Cu, and 1.9 at. % Co. The lower Ti content in the matrix is mainly due to excess Ti in the Ti

2(Ni,Cu) precipitates. The decrease in Ni and increase in Cu are possibly attributed to the overlap of Cu and Ni signals in EDS, which reduces compositional accuracy and causes deviations from the expected values. Additionally, the low Cu content in the Ti

2(Ni,Cu) phase also caused an increase in the Cu content in the matrix. These dark gray Ti

2(Ni,Cu) particles were observed embedded in the matrix, which were inevitably formed due to the presence of even a small amount of oxygen during the melting, hot-rolling, and solution treatment process [

16,

17]. The oxygen is a Ti

2Ni (i.e., the Ti

2(Ni,Cu) phase in this study) stabilizer [

18,

19], which induces the formation of Ti

2(Ni,Cu) phase in this study, even though the alloy is not rich in Ti (i.e., Ti is not above 50 at. %), as also reported in several studies [

17,

20,

21,

22].

Figure 1b shows the electron backscattered diffraction (EBSD) image of the ST sample, highlighting its distribution of crystal orientations. The observation direction was perpendicular to the rolling direction. Using the intercept method, the average grain size was estimated to be approximately 30 μm. Additionally, although the crystals are predominantly oriented along the [111] direction, their intensity was not significant (1.19). Therefore, the alloy exhibited a weak texture and was significantly influenced by the orientation.

Figure 1c shows the XRD spectra collected at 300 K and 100 K. At 300 K, the B2 parent phase and Ti

2Ni were identified on the spectrum. Because the second phase exhibited a cubic structure (crystal structure of Ti

2Ni) and contained a slight amount of Cu content (

Table 1), it was marked as the Ti

2(Ni,Cu) phase. After cooling to 100 K, the B2 parent phase transformed to B19′ martensite, as identified by the diffraction signals. The XRD spectra confirmed that the alloy underwent a B2 to B19′ martensitic transformation.

A DSC heat flow curve was used to determine the characteristic martensitic temperatures, including martensite start temperature (M

s), martensite peak temperature (M

p), martensite finish temperature (M

f), austenite start temperature (A

s), austenite peak temperature (A

p), and austenite finish temperature (A

s), as shown in

Figure 1d. A sharp phase change peak during cooling and heating confirmed an obvious phase transformation B2 ⇿ B19′. The M

p and A

p were 251.3 K and 265.2 K, respectively. Furthermore, M

s and M

f were 255.6 K and 244.7 K, and A

s and A

f were 260.2 K and 270.8 K, respectively, with a transformation temperature range of 10.9 K for martensitic transformation (M

tr = M

s − M

f) and 10.6 K for reverse martensitic transformation (A

tr = A

f − A

s).

The variations in storage modulus and tan(δ) with temperature were measured by DMA, as shown in

Figure 1e,f, respectively. With a rise in temperature, the storage modulus fell sharply, reaching a minimum at a temperature of 265 K, and then rose steeply. Valley formation at a temperature of 265 K corresponded to the phase transformation (martensite ⇿ austenite). During the phase transformation, the storage modulus softens temporarily due to rearrangements in the crystal structure (coexistence of both martensite and austenite phases). However, tan(δ) increased with temperature, reaching a maximum at a temperature of 266 K, and then fell sharply, forming a peak at a temperature of 266 K. The peak formation also confirmed the phase transformation within the material, as this peak formation showed more internal friction generation, mainly due to interface movement during the phase transformation. The thermal analyses by DSC and DMA showed that the crystal structure transformed with temperature, which was a characteristic of SMAs.

3.2. Shape Memory Effect via Thermal Cycling Test Under Bias Applied Stress

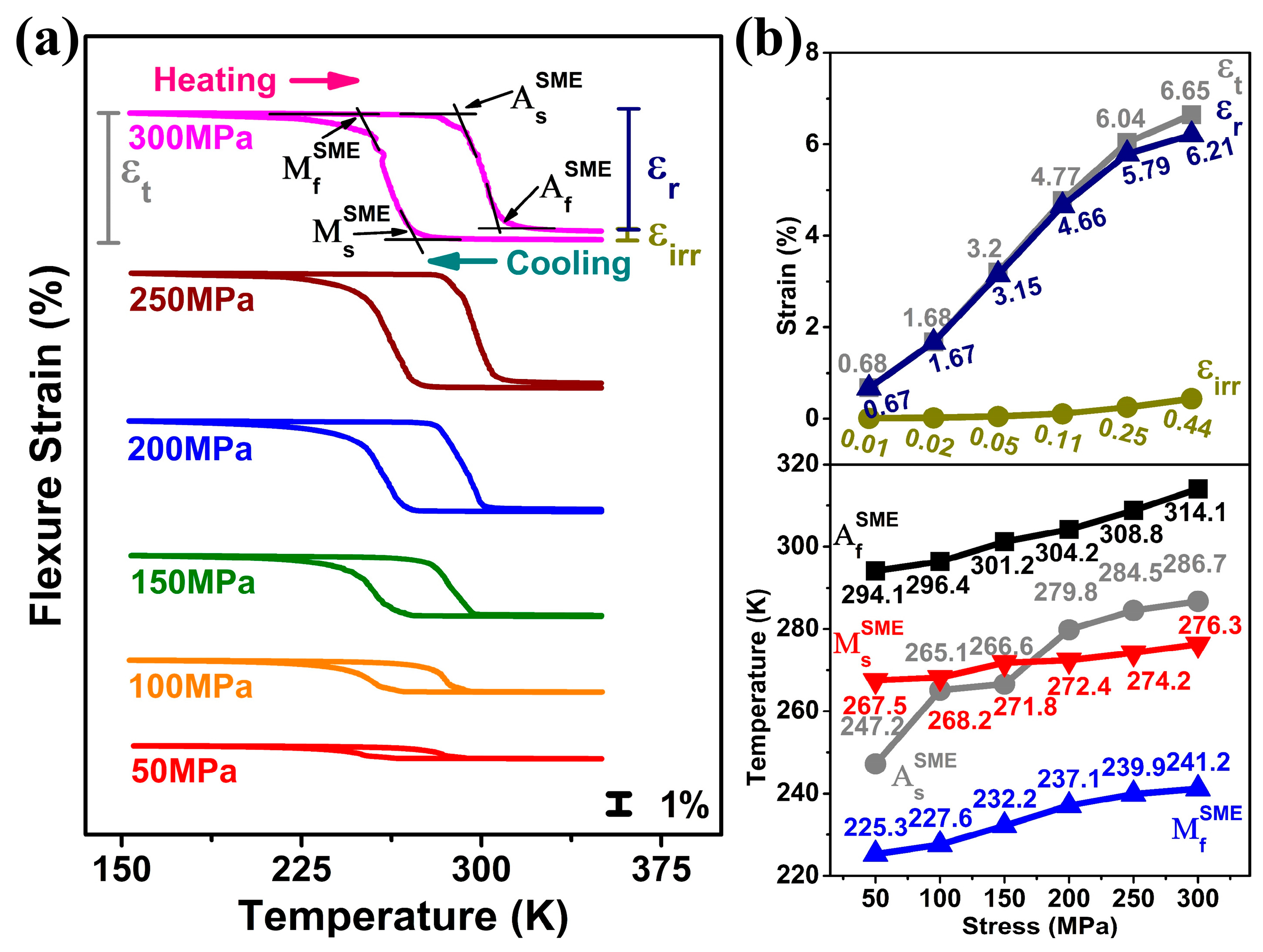

Shape memory effect (SME) was studied for different applied stress conditions (50 MPa to 300 MPa) in a temperature range of 150 K to 350 K.

Figure 2a shows the strain–temperature curves, which include cooling stage (austenite → martensite) and heating stage (martensite → austenite) for a given stress condition. The various strains measured during experiments were maximum strain (ε

t), recoverable strain (ε

r), and irrecoverable strain (ε

irr), as indicated in

Figure 2a. The results are summarized in

Figure 2b. In

Figure 2b, as the applied stress increased from 50 to 300 MPa (in a step of 50 MPa), all three strains increased; ε

t increased from 0.68% to 6.65%, ε

r from 0.67% to 6.21%, and ε

irr from 0.01% to 0.44%. Maximum strain (ε

t) and recoverable strain (ε

r) were nearly equal up to 200 MPa, but they deviated as stress increased beyond 200 MPa, indicating the occurrence of plastic deformation during martensitic transformation under this applied stress level. As shown in

Figure 2b, higher stresses triggered not only martensite formation and reorientation but also dislocation generation and plastic deformation, resulting in increased irrecoverable strain (ε

irr) and reduced SME efficiency. Further, increasing the applied stress steepens the cooling and heating slopes, thereby narrowing the transformation temperature range. Additionally, it was noted that the transformation temperatures under applied stress, including

,

,

and

, increased with increasing applied stress, following the Clausius–Clapeyron relation.

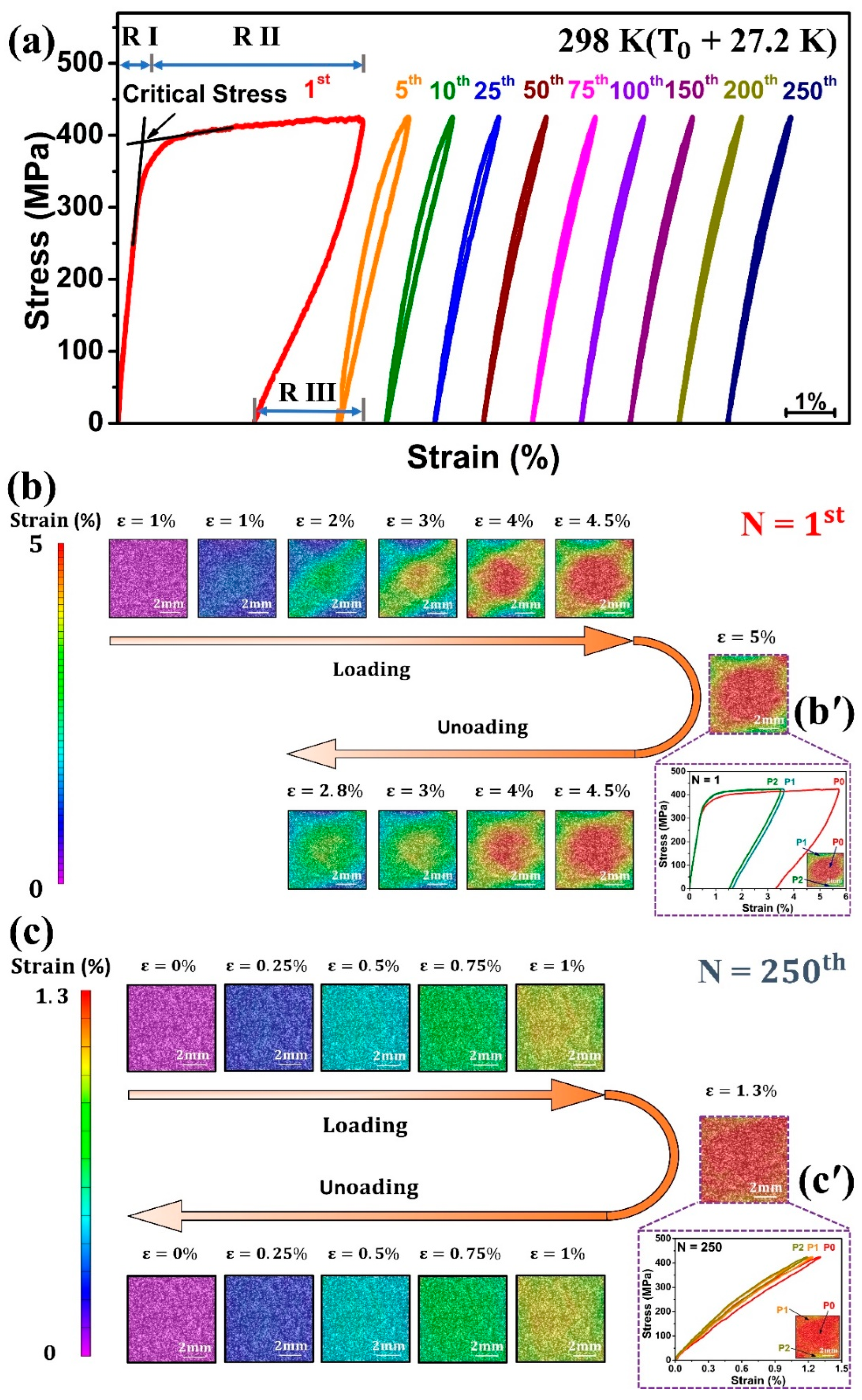

3.3. Cyclic Tensile Superelasticity

Cyclic tensile superelasticity test was conducted with a constant maximum stress of 425 MPa at room temperature (298 K), which is higher than A

f (270.8 K). The stress–strain curve during loading and unloading of the 1st cycle can be distinguished into three main regions, as shown in

Figure 3a. Region I (R I): austenite (B2) phase deformed elastically showing linear stress–strain response; region II (R II): this region started when stress reached to the critical stress, leading to the transformation of austenite (B2) into martensite (B19′); region III (R III): the unloading process caused reverse transformation with almost linear fall in stress–strain curve. The maximum strain (ε

t), recoverable strain (ε

r), and irrecoverable strain (ε

irr) obtained during the first cycle were 5.0%, 2.2%, and 2.8%, respectively. An obvious residual strain was observed during the 1st superelastic cycle.

Figure 3b shows the DIC analyses for the 1st cycle. During loading, Lüders-like strain bands appeared, and a change in strain was concentrated at the specimen center. During unloading, significant residual strain remained due to extensive B2 → B19′ transformation. The two lattices, B2 and B19′, generated dislocations at their interfaces, which hinder the reverse transformation [

14]. As a result, residual martensite was left [

23], causing residual strain after unloading.

Figure 3b’ illustrates the local stress–strain distribution at the maximum strain (ε

t = 5%) of the 1st cycle. Even though the average strain was 5%, the strain distribution throughout the region of consideration was non-uniform. The center region (P0) underwent the highest strain of 5.7%; however, regions (P1 & P2) far away from the center were less strained, reaching 3.6% and 3.5%, respectively, confirming a localized and heterogeneous transformation process.

The high irrecoverable strain indicated its lower strength and was prone to plastic deformation, which was undesirable for engineering applications. To achieve practical applications, stable superelasticity and elastocaloric performance were obtained through cyclic tensile stretching to 425 MPa at room temperature.

Figure 3a shows the cyclic tensile response of solution-treated Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA. The stress–strain curve changed from the flag-type mode (1st cycle) to a quasi-linear one after tensile superelasticity cycles. In the first cycle, the maximum strain was 5.0% and an irrecoverable strain was 2.8%, but with an increase in the number of cycles, these strains decreased, and by the 10th cycle, their values decreased to 1.4% and 0.01%, respectively. For the later cycles, the maximum strain (ε

t) and recoverable strain (ε

r) stabilized at 1.3% while irrecoverable strain almost vanished, indicating the reaching of a stable status.

Figure 3c shows the DIC analyses of the 250th superelastic cycle. The strain distributions during the loading and unloading were more uniform than in the 1st cycle, and no residual strain was observed. Local strain distribution at the maximum strain of the 250th cycle is shown in

Figure 3c’. It can be seen that when P0 reached the maximum strain of 1.31%, P1 was 1.24% and P2 was 1.19%, indicating that the defects or dislocations generated during previous cycles promote the homogeneous martensitic phase transformation [

24].

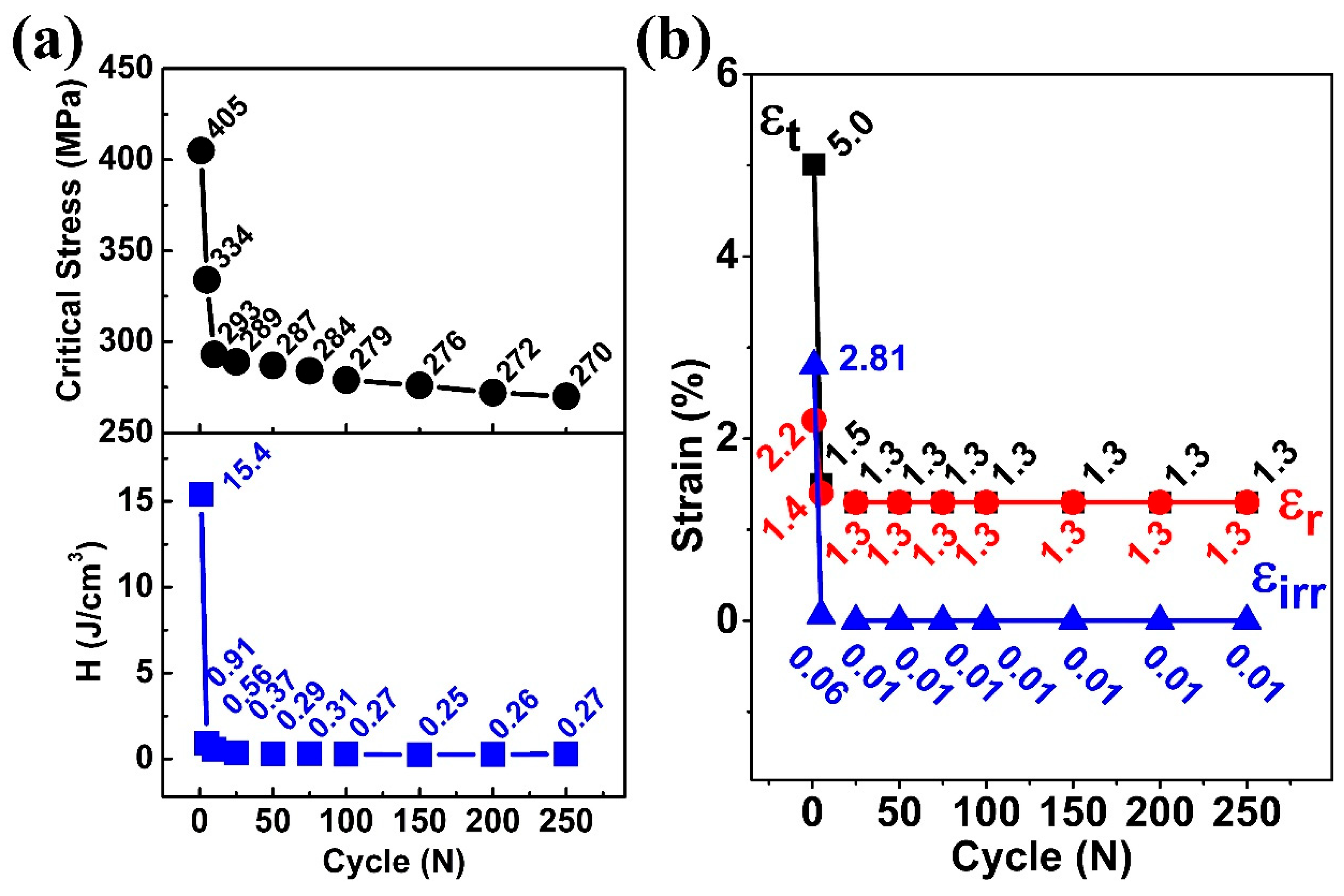

Figure 4a summarizes the evolution of the critical stress during the superelastic cycles. Critical stress for a shape memory alloy is defined as the stress that needs to be applied for the start of transformation from austenite (B2) to martensite (B19′) at a given temperature. Generally, the critical stress is identified as an intersection point between the tangents to the linear elastic deformation region I (R I) and the plateau transformation region II (R II), as shown in

Figure 3a. The critical stress for martensitic transformation dropped from 405 MPa in the 1st cycle to 334 MPa at the 5th and 270 MPa at the 250th cycles, as shown in

Figure 4a. This reduction in critical stress during the cyclic test was attributed to the residual martensite, which generated residual strain fields that promote transformation, thereby lowering the stress required to induce martensitic transformation [

25]. Further, the dissipation energy (H), which was calculated from the area of the stress–strain curves, also decreased sharply from 15.4 J/cm

3 in the 1st cycle to 0.91 J/cm

3 in the 5th and 0.27 J/cm

3 in the 250th cycles. This decline in dissipation energy indicated that the friction between the austenite and martensite during martensitic transformation reduced, associated with the quasi-linear stress–strain behavior.

The evolutions of the maximum strain (ε

t), recoverable strain (ε

r), and irrecoverable strain (ε

irr) during the superelastic cycles are summarized in

Figure 4b. It can be seen that when the maximum strain at the 1st cycle was 5.0%, the irrecoverable strain was 2.8%, which dropped sharply by 97.8% to 0.06% in the first 5 cycles. A similar observation was found for the maximum strain (ε

t). For the first 5 cycles, the maximum strain dropped by 70%, from 5.0% to 1.5%. In the 10th cycle, the maximum strain (ε

t) and irrecoverable strain (ε

irr) became 1.3% and 0.01%, respectively. After the 25th cycle, irrecoverable strain became negligible (0.01%), and the recoverable strain (ε

r) reached the maximum strain (ε

t), indicating that the system became stable. One can notice that even though the same maximum stress was reached during each cycle, the maximum strain attained during the loading decreases from 5% in the first cycle to 1.3% during the 250th cycle, indicating that the residual deformation during the cycle reduced the maximum strain by inhibiting the martensitic transformation. However, at the same time, the stability of the superelastic behavior became quasi-linear and stable.

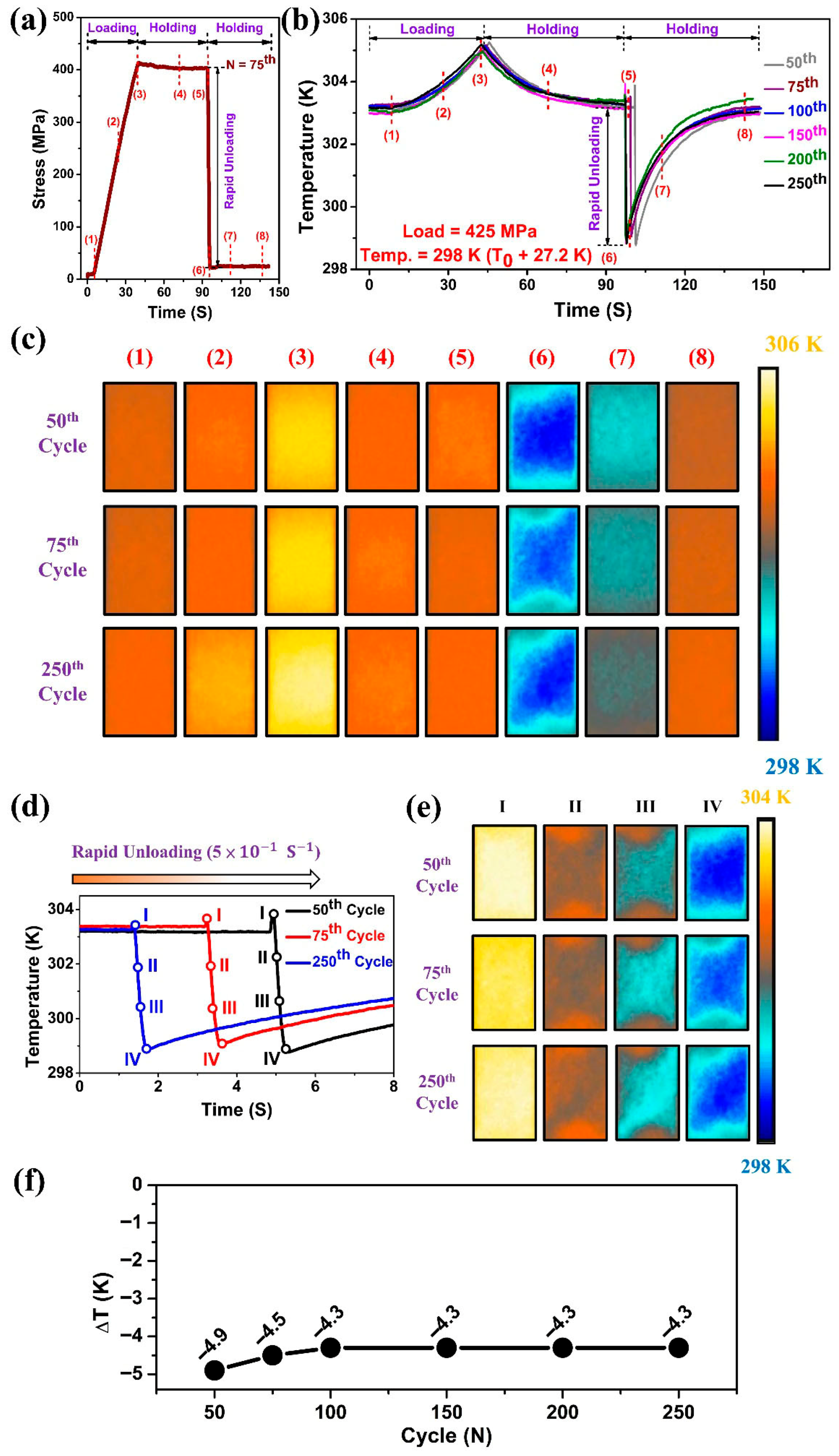

3.4. Cyclic Elastocaloric Cooling Effect

According to the superelasticity results shown in

Section 3.3, the superelastic behavior became stable after several cycles. Therefore, the initial cycles were ignored, and only the elastocaloric cooling effect from the 50th to the 250th cycle was considered.

Figure 5 shows the local temperature profiles captured by the IR camera at different tensile cycles with a loading stress of 425 MPa. The steps involved in measuring the elastocaloric cooling effect of Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA are presented in

Figure 5a. During loading, a slow strain rate of 3 × 10

−4 s

−1 was applied until a maximum load of 425 MPa was reached. Thereafter, the load was held for 50 s, and then rapidly unloaded to 50 MPa with a high strain rate of 5 × 10

−1 s

−1 to achieve a near adiabatic condition during the reverse phase transformation [

26].

The average temperature change with respect to time during loading and unloading (both forward and reverse transformation) over an observation area of 8 × 8 mm

2 is shown in

Figure 5b. To study the localized energy absorption and release during loading and unloading, sequential points were identified and marked on the curves, and their corresponding thermographs at specific cycles were presented in

Figure 5c. Point 1 was identified as the beginning of the martensitic transformation (B2 → B19′), as a slight rise in temperature was observed after this point. As the load increased, the temperature of the sample rose, and the temperature field (points 2 & 3) became slightly nonuniform. As can be seen in

Figure 3c,c’, a hot zone appeared near the center of the specimen, where higher deformation was observed, corresponding to the preferred region for phase transformation. Additionally, the upper and lower regions of the sample, which touch the clamps, also contribute to heat transfer, resulting in lower temperatures in these portions. Point 3 is marked at the peak of the temperature–time curve, where the load reached a maximum stress of 425 MPa. After reaching a maximum load of 425 MPa, the sample was held in the strained condition for 50 s, allowing the sample temperature to reach ambient temperature through heat exchange (Points 4 & 5).

The reverse transformation started immediately upon unloading from Point 5. The temperature of the sample dropped rapidly by −4.9 K for the 50th cycle and −4.3 K for the 250th cycle, respectively, due to the elastocaloric effect induced by the reverse transformation. Finally, heat transfer between the specimen and the surrounding environment raised the temperature of the specimen, exhibiting a uniform temperature profile (

Figure 5c—Points 7 and 8).

Figure 5d,e show the detailed evolution of temperature distributions during the unloading process at the 50th, 75th, and 250th cycles. The generation and propagation of the cold bands caused by the reverse martensitic transformation during rapid unloading were observed. The temperature of the samples dropped rapidly with the expansion of the cold bands, resulting in stable elastocaloric profiles over 250 cycles.

The evolution of ΔT with cycle number of the Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA is shown in

Figure 5f. It has been observed that for the 50th cycle, the ΔT was higher (−4.9 K); however, with an increase in testing cycles, the ΔT decreased slightly and stabilized at −4.3 K by the 100th cycle. Beyond the 100th cycle, the elastocaloric effect became stable, indicating no further changes in microstructure during loading.

With an increased number of repeated cycles, the cooling ability decreased slightly from −4.9 K at the 50th cycle to an almost stable cooling capacity of −4.3 K, while the temperature profile repeatedly followed the same pattern during loading and unloading of cycles. Additionally, the trained (cycled) Ti50Ni41Cu7Co2 SMA exhibited uniform temperature profiles, which could serve efficiently for elastocaloric applications.

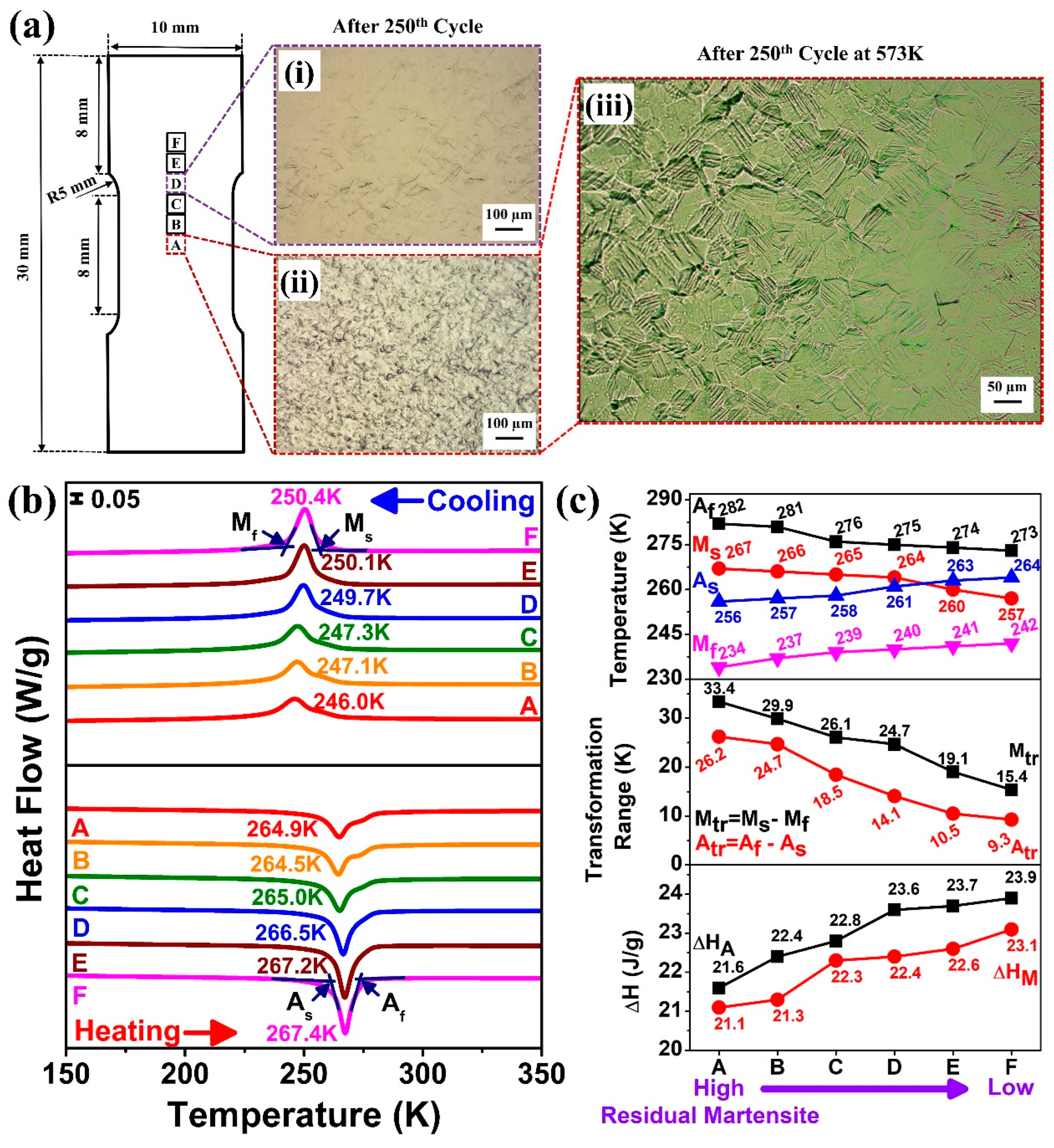

3.5. Study of Local Transformation Behavior After 250 Superelastic Cycles

A systematic study was conducted to reveal the local transformation behavior over the tensile specimen after the 250th superelastic cycle. The tensile specimen was sectioned in different regions (A–F) as shown in

Figure 6a.

Figure 6(ai) shows the optical microscope (OM) image of region D (far away from the deformation zone), and

Figure 6(aii) shows the OM image of region A (at the deformation zone). A small amount of martensite appeared in region D, characterized by less strain variation within this region; however, region A underwent greater deformation, resulting in more residual martensite.

Figure 6(aiii) shows the OM image of region A after heating at 573 K. The retained martensite indicates that defects generated during cyclic superelastic loading stabilized the martensitic phase, preventing its reversion to austenite even well above A

f (282 K), as shown in

Figure 6a. This stabilization resulted in reduced strain after the cyclic test, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4.

Figure 6b shows the DSC results for regions A–F of the tensile specimen. During cooling, the phase transformation signal (B2 → B19′) flattened gradually as the position moved from region F to A (increasing residual martensite), with decreases in the peak transformation temperature (from 250.4 K to 246.0 K). Similar behavior was observed while heating; the reverse martensitic phase peak (B19′ → B2) flattened similarly, and the reverse peak transformation temperature also decreased from 267.4 K to 264.9 K. It is obvious from the DIC experimental result that closer to region A, higher residual martensite and dislocation formed, which suppressed the phase transformation, resembling the effect of cold working [

27].

Figure 6c summarizes the phase transition temperatures across regions A–F. As moved from region F to A (increasing residual martensite), M

s and A

f temperatures increased from 257 K to 267 K and 273 K to 282 K, respectively. On the other hand, A

s and M

f temperatures decreased from 264 K to 256 K and from 252 K to 234 K, respectively. Due to the heavy processing near the deformation zone, M

s and A

f rose while M

f and A

s fell, and hence the transformation peak broadened. Further, the transition temperature ranges, i.e., M

tr and A

tr, increased from 15.4 K to 33.4 K and from 9.3 K to 26.2 K, respectively, across regions from F to A (i.e., increasing residual martensite). The wider ranges near region A result from defects generated during superelastic cycles, which created stress fields that alter local martensitic transformation temperatures [

28]. It was noted that the increase in M

s but decrease in M

f suggested that some martensitic transformation was triggered, but some was hindered by the dislocations.

Figure 6c also includes the latent heat variations across the tensile specimen. From region F to A (increasing residual martensite), both ΔH

M and ΔH

A decreased from 23.1 to 21.1 J/g and 23.9 to 21.6 J/g, respectively. This indicated that dislocations generated during the cyclic test suppressed martensitic transformation, resulting in smaller latent heat. Compared to region F, the highly deformed region A exhibited higher A

f and M

s, lower A

s & M

f, and wider M

tr and A

tr transformation temperature range with reduced ΔH

M and ΔH

A. These observations confirmed the stabilization and hindrance of martensitic phase transformation due to the generation of dislocations during superelastic cycles.

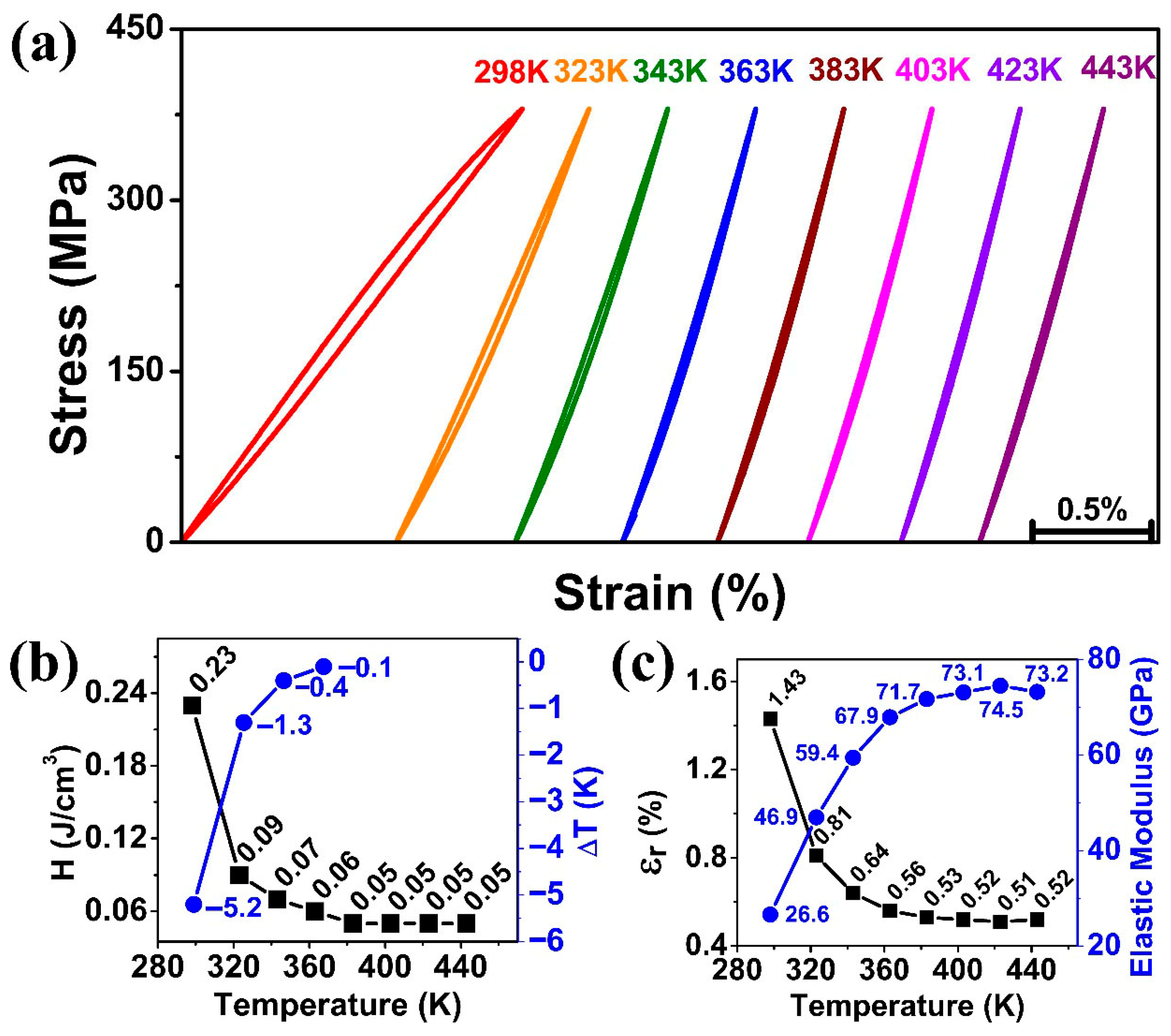

3.6. Effect of Operating Temperature on Superelasticity and Elastocaloric Effects

In order to serve industrial requirements, a shape memory alloy with stable superelasticity and elastocaloric cooling effect over an operating temperature range is desired. According to the results shown in

Section 3.3 and

Section 3.4, the SMAs showed high stability in superelasticity and elastocaloric cooling effect after 50 superelastic cycles. Therefore, a tensile sample trained with 100 superelastic cycles was selected for studying the effect of operating temperature on its functional performance.

Figure 7 shows the effect of operating temperature on superelasticity and elastocaloric effect tested between 298 K and 443 K. Under the maximum stress of 425 MPa, the stress–strain curves remained linear for all temperatures, as shown in

Figure 7a.

Figure 7b shows the energy dissipation of the stress–strain curves at different temperatures, which dropped drastically for the early increase in temperature. It was 0.23 J/cm

3 at 298 K and dropped to 0.09 J/cm

3 at 323 K, and became almost stable at 0.05 J/cm

3 beyond 363 K.

Figure 7b also shows the elastocaloric cooling effect at different temperatures. While the highest cooling effect was measured at 298 K (−5.2 K), and then sudden drop in cooling effect (dropped by 75%) was measured at 323 K, which was −1.3 K. Thereafter, elastocaloric effects continuously decreased to −0.4 K and −0.1 K at temperatures of 343 K and 363 K, respectively. After 383 K, no obvious elastocaloric effect was observed, suggesting that mainly elastic deformation occurred at the temperature of 383 K. These features followed the Clausius–Clapeyron relation, which meant that the more the operating temperature is away from the austenite finish temperature (A

f), the less likely it is to produce stress-induced martensitic transformation.

Figure 7c shows the relationship between the recoverable strain (ε

r) and elastic modulus (E) at different operating temperatures. For all the temperature conditions, ε

irr was negligible, and ε

t and ε

r were equal. The recoverable strain (ε

r) almost followed a similar trend as that of the energy dissipation, showing a rapid decline from 1.43% at 298 K, to 0.81% at 323 K, and to just 0.52% above 363 K. Additionally, the elastic modulus was calculated using Equation (1), according to S. Zhao et al. [

29] as follows:

where

E,

σmax, and

εmax represent the elastic modulus, the maximum stress, and the maximum strain, respectively. The elastic modulus rose drastically from 26.6 GPa to 71.7 GPa with increasing temperature from 298 K to 383 K, and then became stable. Above the operating temperature of 383 K, no obvious phase transformation was detected (neither energy dissipation nor elastocaloric effect), which suggested the stress of 425 MPa was not sufficient for stress-induced martensitic transformation at these high temperatures (according to the Clausius–Clapeyron relation), and hence only elastic deformation occurred in the specimen. Therefore, the elastic moduli at temperatures of 383 K, 403 K, 423 K, and 443 K were 71.7 GPa, 73.1 GPa, 74.5 GPa, and 73.2 GPa, respectively, which are quite close to each other and provide almost stable elastic modulus for high-temperature conditions. It is also noted that, even though the martensitic transformation was limited at these high temperatures, relatively large recoverable strains (>0.5%) were available, surpassing the 0.2% plastic deformation strain for conventional metallic materials.

After being trained with 100 superelastic cycles, the Ti50Ni41Cu7Co2 SMA showed a rapid decline in the performance of the elastocaloric effect with an increase in operating temperature due to the insufficient stress to induce martensitic transformation. It is expected that, to trigger the superelasticity and elastocaloric effect at high operating temperatures, an increase in the applied stress is needed. However, an increase in applied stress is also expected to disrupt the original stability and may cause the formation of residual strain, which needs further study in the future.

3.7. Discussion on the Performance of TiNiCuCo SMA

The Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA exhibits stable functional properties after superelastic training, including a 1.3% recoverable strain, a −4.3 K elastocaloric cooling effect, and superelasticity over a wide temperature range with strains exceeding 0.5%. The stabilization of functionality is also observed in a binary TiNi

50.8 SMA [

29], which exhibits reversible strains of around 1.6–2.3% after 100 cycles. This quasi-linear feature was also observed in compression deformation of TiNi

50.4 [

30] and Ti

50Ni

48Fe

2 [

31] SMAs, in which recoverable strains of about 2% and 1.6% were reported, respectively. The smaller recoverable strain in the TiNiCuCo shape memory alloy was attributed to the addition of copper, which is known to reduce recoverable strain as the copper content increased [

31]. Additionally, the TiNi

50.4 [

30] and Ti

50Ni

48Fe

2 [

31] SMAs exhibited elastocaloric cooling effects of −3.9 K and −3.5 K after cyclic loading, respectively, which were slightly smaller than that of the Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA reported in this study. These features indicated that the Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA could generate a comparable or better elastocaloric cooling effect with a smaller strain, which is beneficial for designing a compact cooling system.

The as-homogenized Ti-rich Ti

54Ni

31.7Cu

12.3Co

2 bulk SMA was also reported to exhibit quasi-linear superelastic behavior after 100 cycles [

14]. Due to the difference in the testing method, where the sample was unloaded to 100 MPa (not full unloading) and then reloaded, their results could not be directly compared with the functional properties reported here. Nevertheless, a trend was that the Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA exhibited much better stability during the cyclic loading at the solution-treated state during the superelastic cycles. Furthermore, since the shape memory effect, the elastocaloric effect, and the operating temperature window were not tested for the Ti

54Ni

31.7Cu

12.3Co

2 SMA [

14], this study provides a detailed analysis of the bulk TiNiCuCo SMA.

Excellent functional stability over 107 cycles was reported in the TiNiCuCo SMAs in the thin-film form [

13,

32]. Owing to the refined grain size and nano-scale Ti

2Cu phase formed in the thin films, the strength and stability of the TiNiCuCo SMAs were significantly improved. However, as shown in the previous study [

14] and this one, the bulk Ti

54Ni

31.7Cu

12.3Co

2 and Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMAs did not demonstrate results as promising as their thin-film counterparts. Therefore, for applications of TiNiCuCo SMAs in bulk form, careful control of the microstructure is necessary to further enhance their functional stability, such as through cold working, grain refinement, or precipitation hardening (achieved through alloy design). Since studies on bulk TiNiCuCo SMAs are limited, this study provides a comprehensive analysis of the functional performance of the Ti

50Ni

41Cu

7Co

2 SMA in its solution-treated state. Further improvements in performance are expected to be realized through alloy design and microstructure control.