Efficient Removal of Fluorine from Leachate of Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Calcine by Porous Zirconium-Based Adsorbent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Reagents and Materials

2.2. Preparation of Adsorbent

2.3. Characterization

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

2.4.1. Adsorption of Fluoride Ions

2.4.2. Adsorption Isothermal and Adsorption Kinetics Processes

3. Results and Discussion

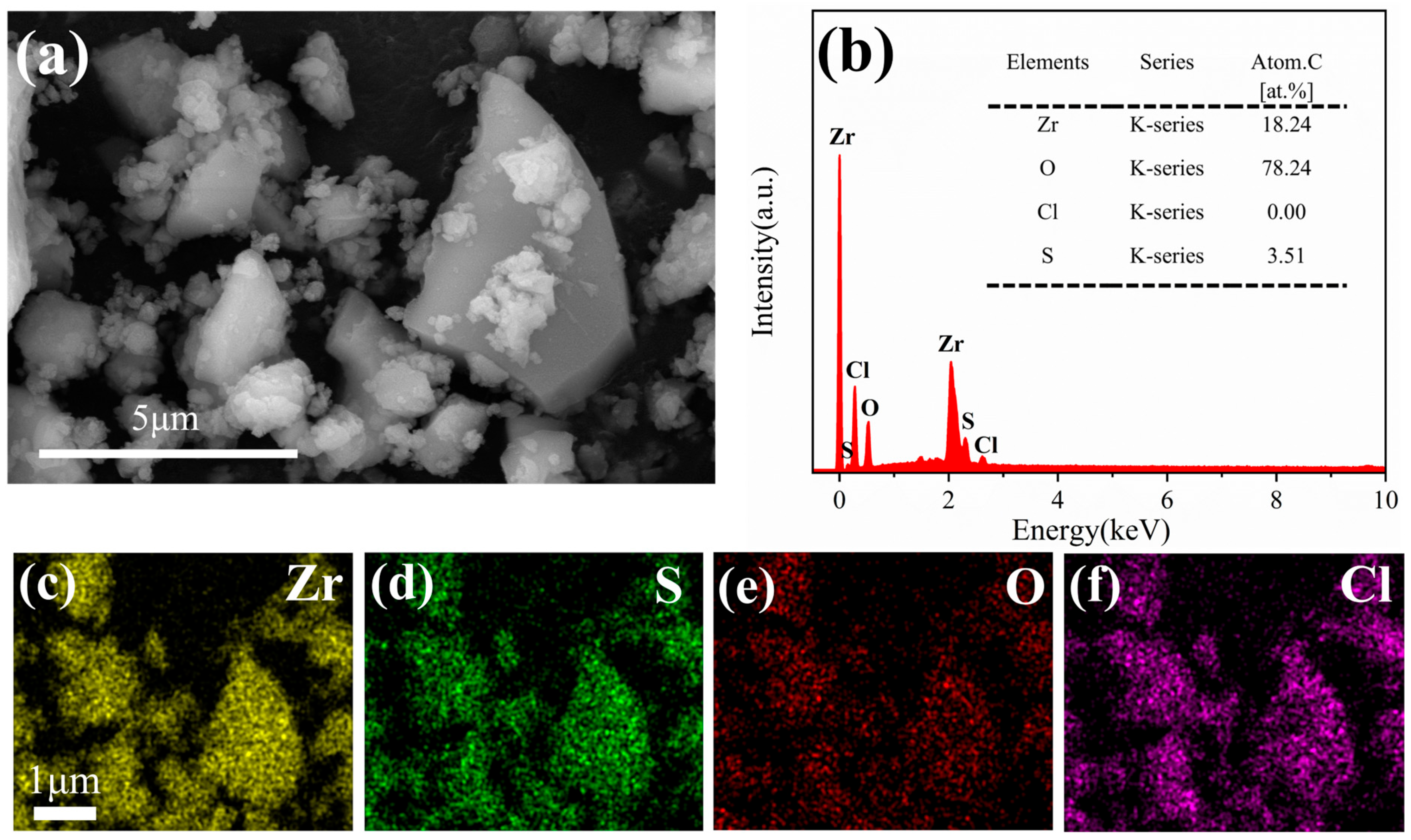

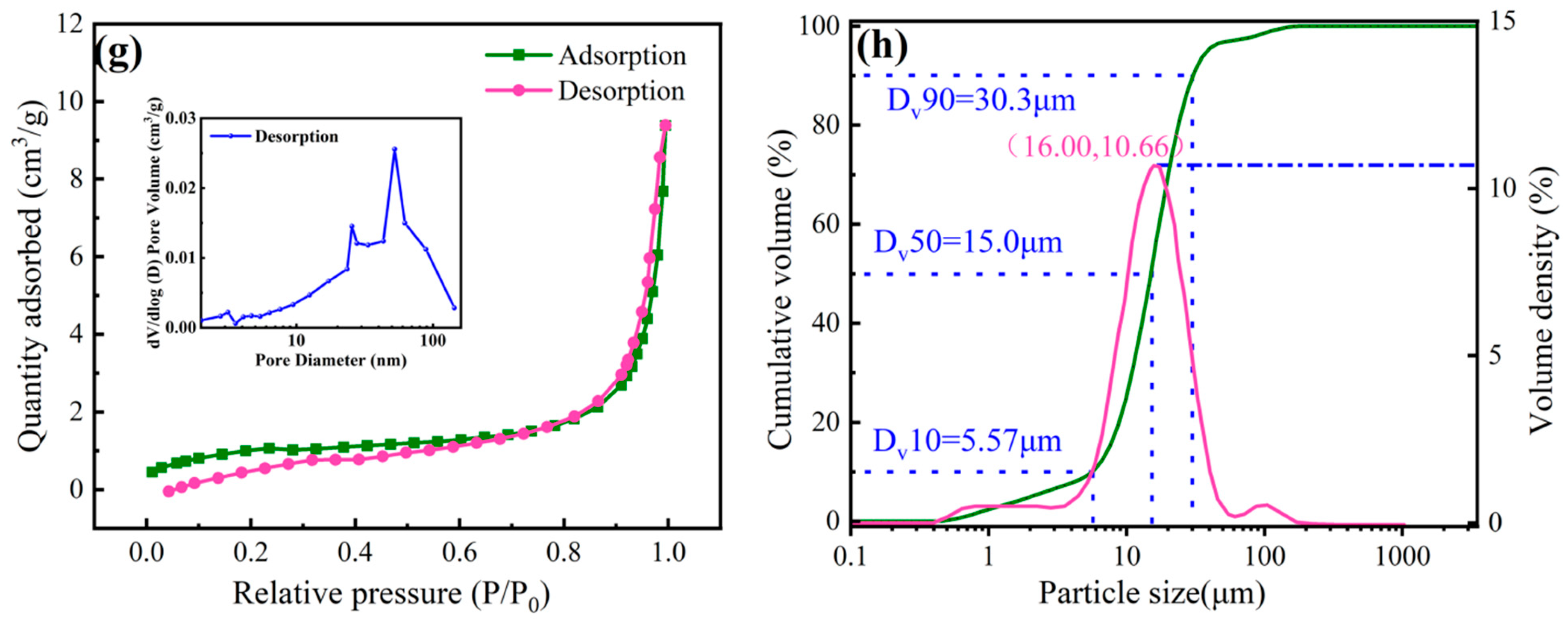

3.1. Characterization of Zirconium-Based Adsorbent

3.2. Selective Removal Fluoride Ions

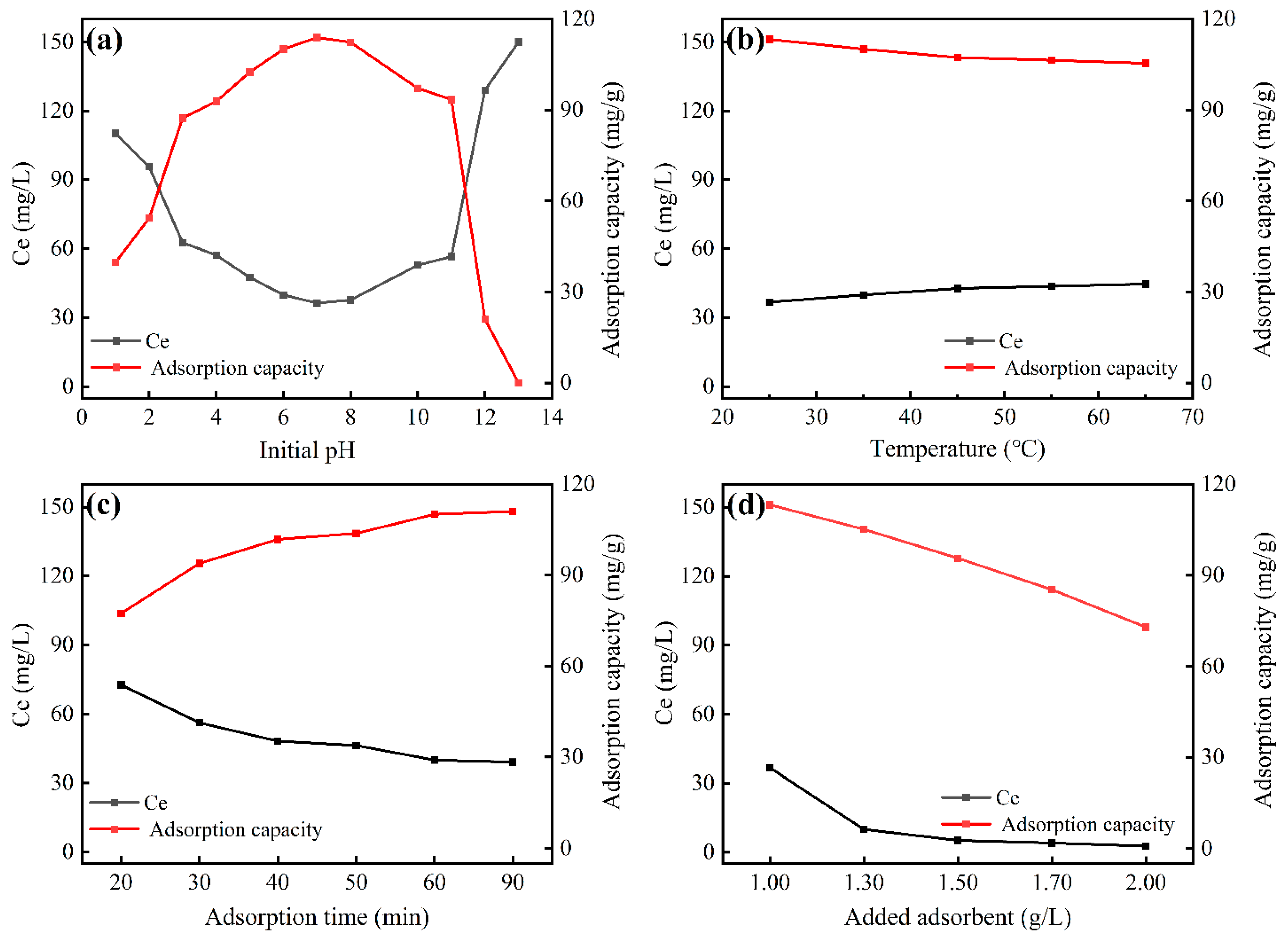

3.2.1. The Effect of Initial pH

3.2.2. The Effect of Temperature

3.2.3. The Effect of Adsorption Time

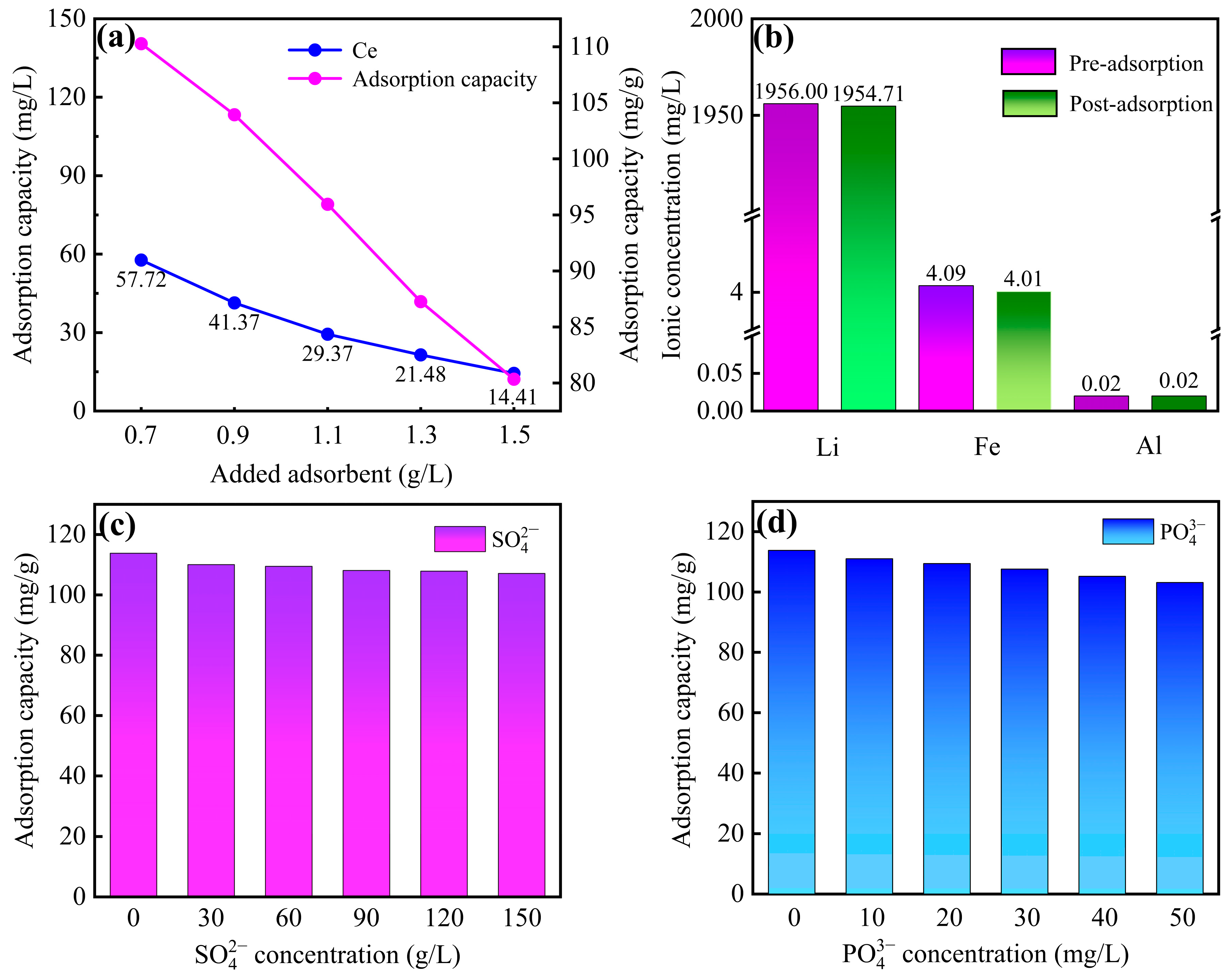

3.2.4. The Effect of Adsorbent Dosage

3.2.5. The Effect on Real Leachate of SLFP Calcine

3.2.6. Effect of Coexisting Anions

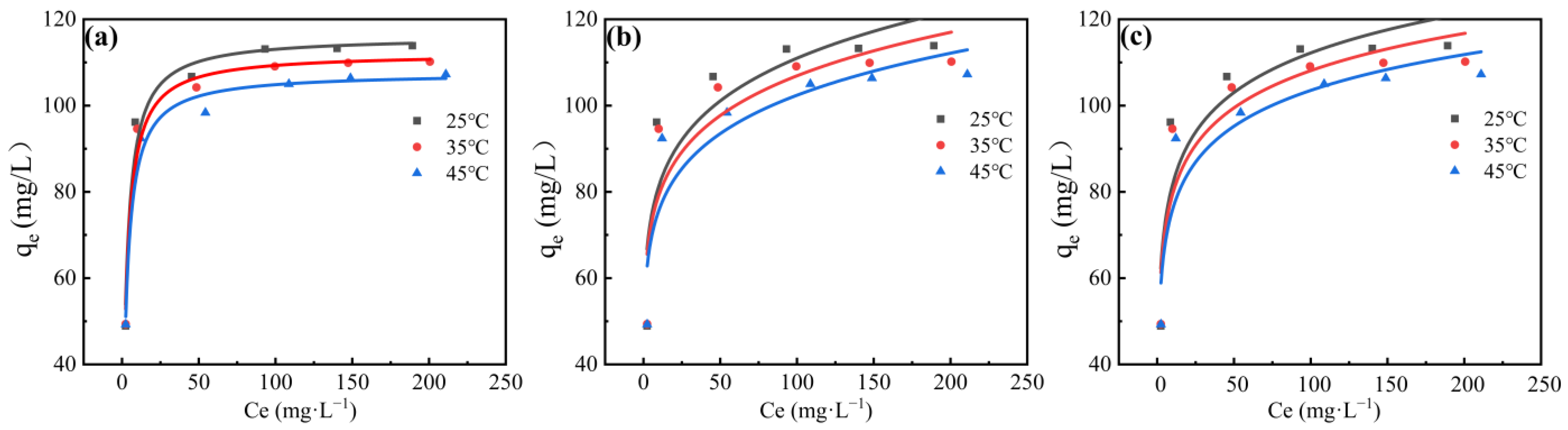

3.3. Adsorption Isotherm Characteristics and Thermodynamic Analysis

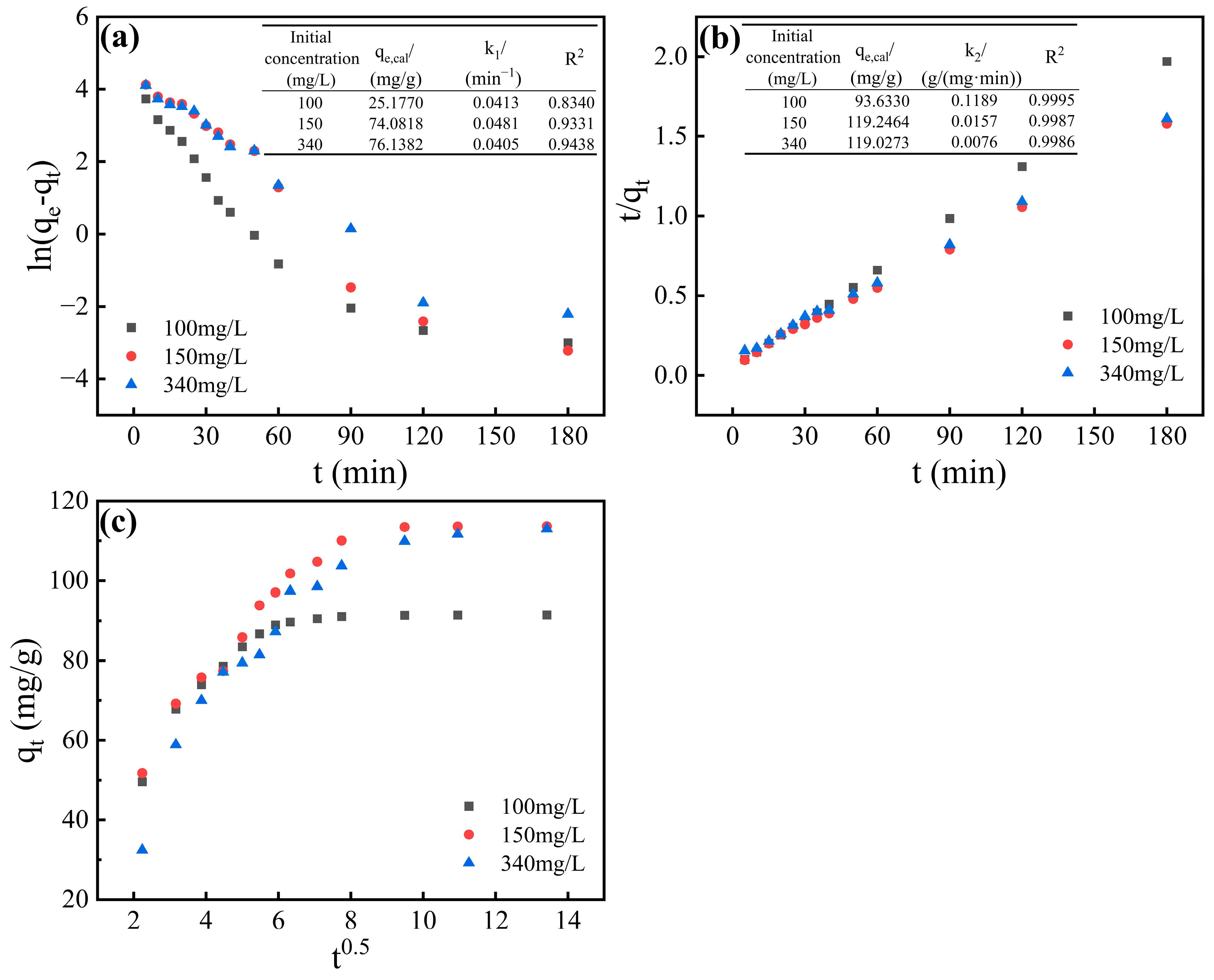

3.4. Adsorption Kinetic Characteristics

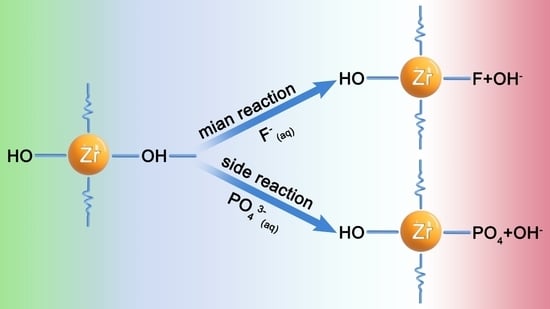

3.5. Mechanisms of Adsorption

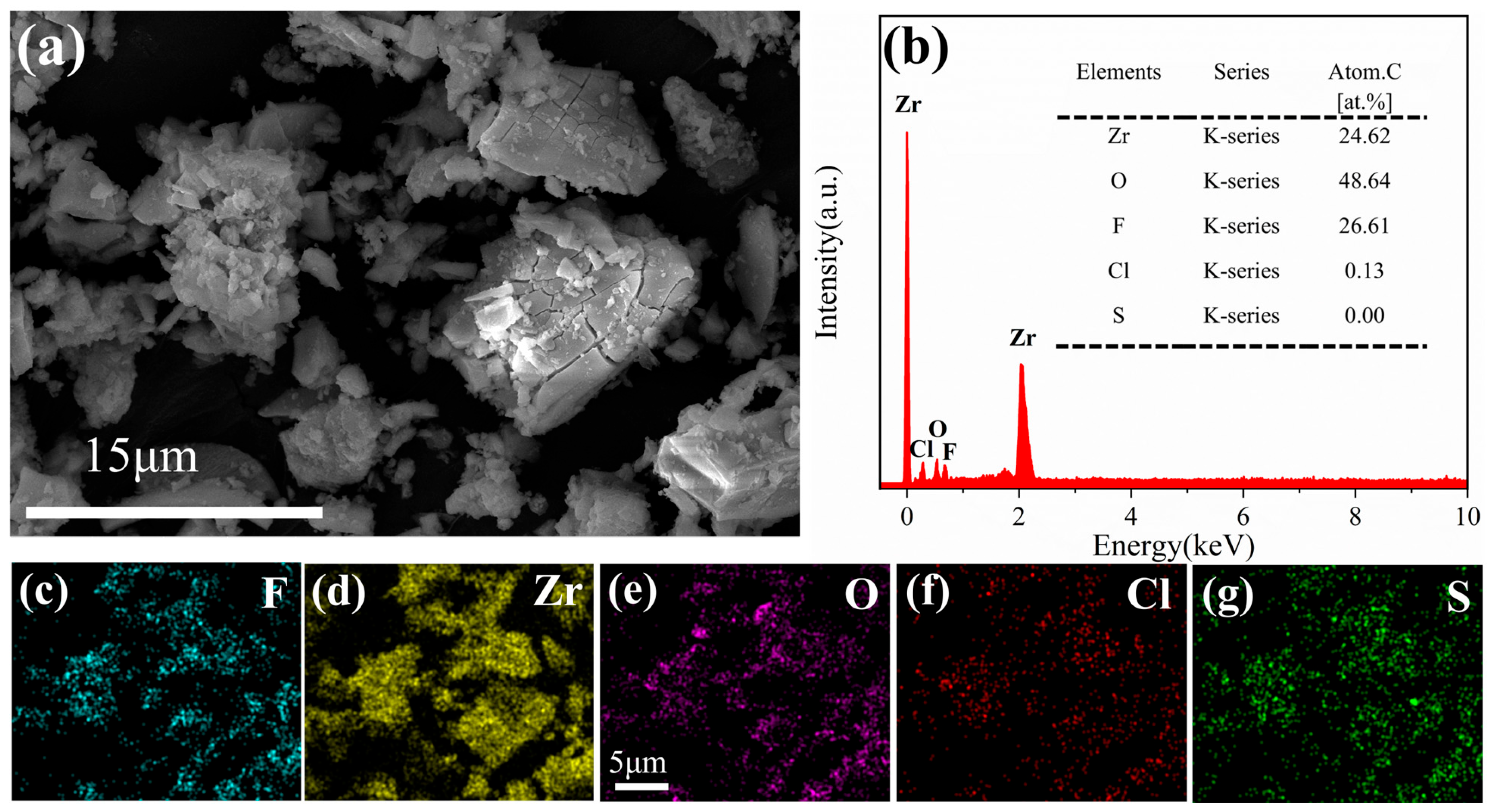

3.5.1. SEM and EDS Analysis of the Adsorbent

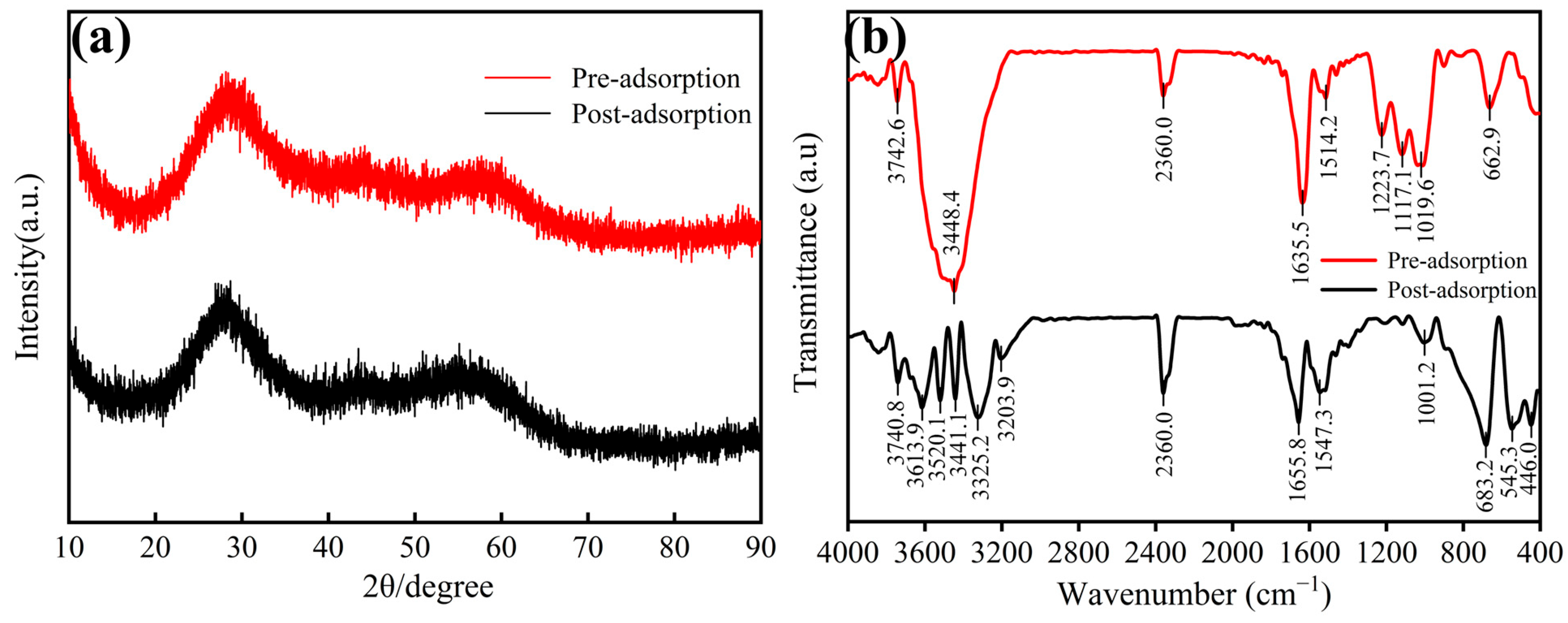

3.5.2. XRD and FTIR Analysis

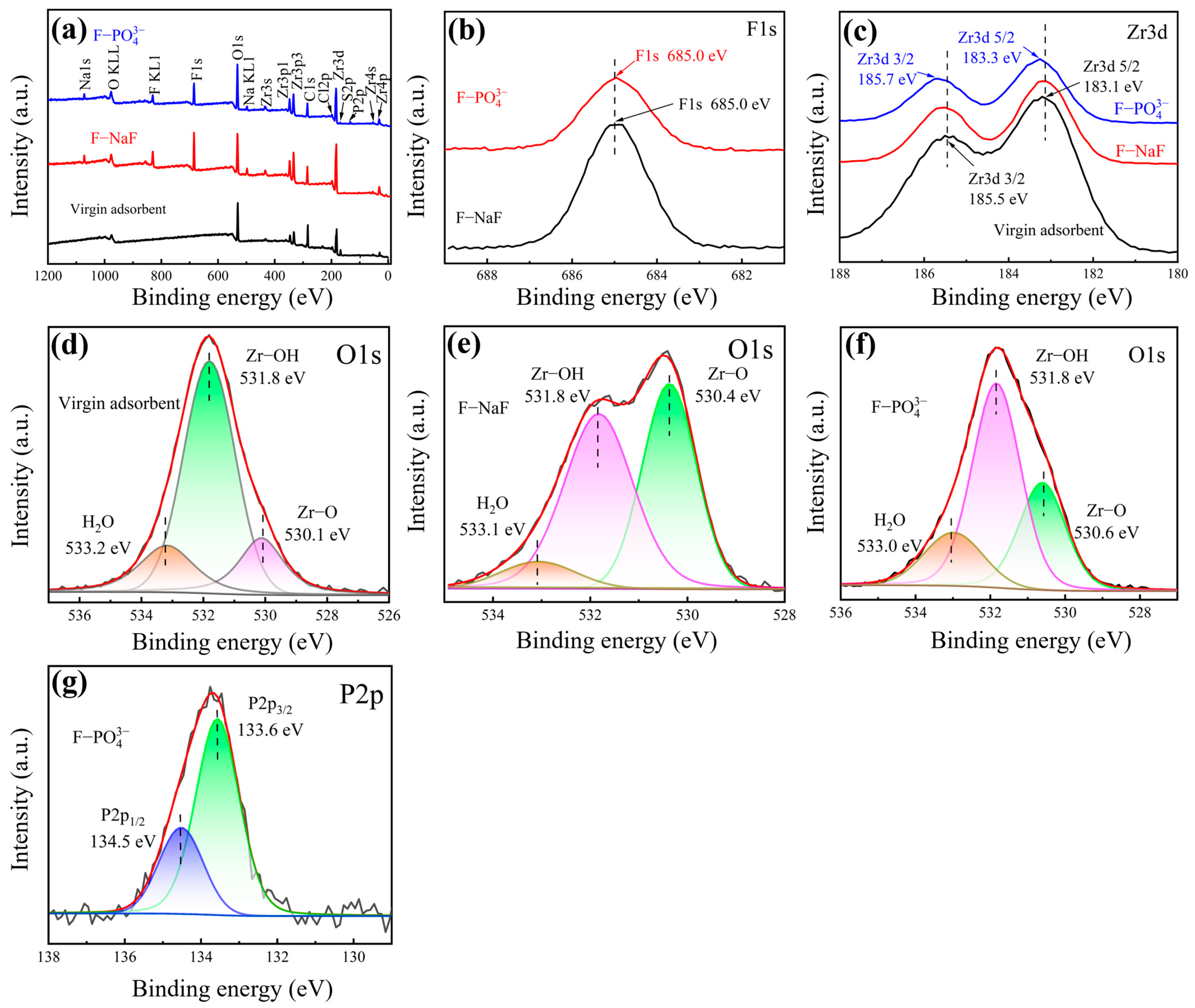

3.5.3. XPS Analysis

3.6. Conclusions and Discussion

- (1)

- Elemental analysis determined the molecular formula of the adsorbent as Zr2(OH)6SO4·3H2O. N2 adsorption–desorption isotherms and pore size distribution confirmed its mesoporous structure, which facilitates fluoride adsorption.

- (2)

- Experimental results showed that the maximum fluoride adsorption capacity of the zirconium-based adsorbent reached 113.78 mg/g at 25 °C and pH = 7.0.

- (3)

- Adsorption isotherm studies indicated that the Langmuir model best described the monolayer chemisorption of fluoride on the adsorbent.

- (4)

- Thermodynamic analysis revealed that fluoride adsorption was a spontaneous and exothermic process.

- (5)

- Kinetic studies demonstrated that the pseudo-second-order model effectively described the adsorption process, suggesting chemical reaction rate control. The adsorbent achieved adsorption equilibrium within 90 min, exhibiting superior fluoride removal efficiency compared to most commercial adsorbents.

- (6)

- The 26.61 atomic% fluorine content in post-adsorption EDS spectra and the emergence of new F1s binding energy in XPS analysis provide direct evidence supporting fluoride adsorption behavior on the zirconium-based adsorbent.

- (7)

- The adsorption mechanism of fluoride ions by this zirconium-based adsorbent mainly involves the substitution of surface hydroxyl groups, ion exchange, and electrostatic adsorption.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, W.; Feng, X.; Han, X.; Zhang, W.; Jiang, F. Questions and Answers Relating to Lithium-Ion Battery Safety Issues. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zheng, M.; Liu, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Nai, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Tao, X. Direct recovery: A sustainable recycling technology for spent lithium-ion battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2023, 54, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Mei, H.; Wan, X.; Shen, F.; Peng, C. A chemical method for the complete components recovery from the ferric phosphate tailing of spent lithium iron phosphate batteries. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 18474–18484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qu, X.; Chen, X.; Liu, D.; Zhao, Z.; Xie, H.; Wang, D.; Yin, H. A sodium salt-assisted roasting approach followed by leaching for recovering spent LiFePO4 batteries. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Fu, J.; Zhang, S.; He, X.; Zhao, B.; Ren, J.; Zhong, J.; Liu, Z. Advances in recycling LiFePO4 from spent lithium batteries: A critical review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 338, 126551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, S.; Bhattacharjee, S.; De, S. Aluminium fumarate metal organic framework incorporated polyacrylonitrile hollow fiber membranes: Spinning, characterization and application in fluoride removal from groundwater. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 334, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štepec, D.; Ponikvar-Svet, M. Fluoride in Human Health and Nutrition. Acta Chim. Slov. 2019, 66, 255–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussein, I.A.; Vegi, M.R. Defluoridation of drinking water using coalesced and un-coalesced mica. Appl. Water Sci. 2020, 10, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, N.; Lei, J.; Gao, H.W.; Yu, F.; Pan, F.; Ma, J. Wedge-Like Microstructure of Al2O3/i-Ti3C2Tx Electrode with “Nano-Pumping” Effect for Boosting Ion Diffusion and Electrochemical Defluoridation. Adv. Sci. 2024, 12, e2411659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaudhary, M.; Rawat, S.; Maiti, A. Defluoridation by Bare Nanoadsorbents, Nanocomposites, and Nanoadsorbent Loaded Mixed Matrix Membranes. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2022, 52, 135–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Let, M.; Majhi, K.; De, A.; Roychowdhury, T.; Bandopadhyay, R. Revealing the defluoridation efficacy of a ureolytic bacterium Micrococcus yunnanensis MLN22 through MICP driven biomineralization for sustainable groundwater development. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Liu, C.; Xie, Y.; Xie, W.; He, Z.; Zhong, H. A critical review on adsorption and recovery of fluoride from wastewater by metal-based adsorbents. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 82740–82761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GB 8978-1996; Integrated Wastewater Discharge Standard. Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 1996.

- Damtie, M.M.; Woo, Y.C.; Kim, B.; Hailemariam, R.H.; Park, K.-D.; Shon, H.K.; Park, C.; Choi, J.-S. Removal of fluoride in membrane-based water and wastewater treatment technologies: Performance review. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 251, 109524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Messaoudi, N.; Franco, D.S.P.; Gubernat, S.; Georgin, J.; Şenol, Z.M.; Ciğeroğlu, Z.; Allouss, D.; El Hajam, M. Advances and future perspectives of water defluoridation by adsorption technology: A review. Environ. Res. 2024, 252, 118857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakkar, M.; Wu, Z.; Wei, L.; Mitra, S. Water defluoridation using a nanostructured diatom–ZrO2 composite synthesized from algal Biomass. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015, 450, 239–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parashar, K.; Ballav, N.; Debnath, S.; Pillay, K.; Maity, A. Hydrous ZrO2 decorated polyaniline nanofibres: Synthesis, characterization and application as an efficient adsorbent for water defluoridation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 508, 342–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, S.B.; Panda, A.P.; Swain, S.K.; Patnaik, T.; Muller, F.; Delpeux-Ouldriane, S.; Duclaux, L.; Dey, R.K. Development of aluminum and zirconium based xerogel for defluoridation of drinking water: Study of material properties, solution kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 6231–6242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Wei, X.; Ling, C.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, X. Revisiting regeneration performance and mechanism of anion exchanger-supported nano-hydrated zirconium oxides for cyclic water defluoridation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 301, 121906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Ji, L.; Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.; Li, X.-G.; Ma, J. Trimetallic MOFs (Zr–La–Ce) Adsorbent for Defluoridation with Ultrahigh Selectivity and Performance under a Wide pH Range. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2025, 17, 35353–35363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, D.; Du, Q.; Wang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Pan, J. Confined synthesis of ultrafine ZrO2 anchoring composites in switchable and microchannel-like space for fluoride removal. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 164275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mahbouby, A.; Ezaier, Y.; Zyade, S.; Mechnou, I. Elaboration and Characterization of Organo-Ghassoul (Moroccan Clay) as an Adsorbent Using Cationic Surfactant for Anionic Dye Adsorption. Phys. Chem. Res. 2023, 11, 913–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-R.; Zhou, J.-E.; Wang, F. Progress of research on advanced materials and their applications. J. Shaanxi Inst. Technol. 2001, 17, 7–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Y.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Chen, J.P. A zirconium based nanoparticle for significantly enhanced adsorption of arsenate: Synthesis, characterization and performance. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2011, 354, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, B.D.; Davis, B.H. Comparison ofNitrogen Adsorption and Mercury Penetration Results. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 1988, 5, 168–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svidrytski, A.; Hlushkou, D.; Thommes, M.; Monson, P.A.; Tallarek, U. Modeling the Impact of Mesoporous Silica Microstructures on the Adsorption Hysteresis Loop. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 21646–21655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmiel, G.L.I.; Sokatowski, S.; Patrykiejew, A. Adsorption in Energetically Heterogeneous Slit-like Pores: Comparison of Density Functional Theory and Computer Simulations. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1994, 90, 1153–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, F. Adsorption by Powders and Porous Solids Principles, Methodology and Applications; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; p. 467. [Google Scholar]

- Cummins, P.L.; Bacskay, G.B.; Hush, N.S.; Ahlrichs, R. The prediction of nuclear quadrupole moments from ab initio quantum chemical studies on small molecules. I. The electric field gradients at the 14N and 2H nuclei in N2, NO, NO+, CN, CN−, HCN, HNC, and NH3. J. Chem. Phys. 1987, 86, 6908–6917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, X.; Wan, Y.; Feng, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, D. Highly Efficient Adsorption of Bulky Dye Molecules in Wastewater on Ordered Mesoporous Carbons. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Breakwell, C.; Foglia, F.; Tan, R.; Lovell, L.; Wei, X.; Wong, T.; Meng, N.; Li, H.; Seel, A.; et al. Selective ion transport through hydrated micropores in polymer membranes. Nature 2024, 635, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, J.; Dai, Z.; Lei, Y.; Liu, X.; Liu, G. Simple preparation and efficient fluoride removal of La anchored Zr-based metal–organic framework adsorbent. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, N.; Kumar, S.A.; Parab, H.; Pandey, A.K.; Bhatt, P.; Kumar, S.D.; Reddy, A.V.R. A fluoride ion selective Zr(IV)-poly(acrylamide) magnetic composite. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 10350–10357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekka, B.; Dhaka, R.S.; Patel, R.K.; Dash, P. Fluoride removal in waters using ionic liquid-functionalized alumina as a novel adsorbent. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 303–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaroniec, M. Adsorbents: Fundamentals and Applications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 12059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liang, L.; Mi, H.; Ma, H.; Li, L. Defluorination performance of lanthanum and zirconium modified aluminum hydroxide in zinc sulfate electrolyte. J. Cent. South Univ. Sci. Technol. 2024, 55, 895–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Bai, X.; Sun, S.; Li, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, T.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Z.; et al. Deep eutectic system based C3N4-Zr composite material for highly efficient removal of fluoride in hydrochloric acid. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 342, 126985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghouti, M.A.; Da’ana, D.A. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of adsorption isotherm models: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 393, 122383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The adsorption of gases on plane suafaces of glass, mica and platinum. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1918, 40, 1361–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnou, I.; Meskini, S.; Elqars, E.; Ait El Had, M.; Hlaibi, M. Efficient CO2 capture using a novel Zn-doped activated carbon developed from agricultural liquid biomass: Adsorption study, mechanism and transition state. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 52, 104846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Li, X.; Tian, L.; Wang, T.; Wang, Q.; Niu, P.; Chen, P.c.c.; Luo, X.l.c. Defluoridation investigation of Yttrium by laminated Y-Zr-Al tri-metal nanocomposite and analysis of the fluoride sorption mechanism. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 648, 1342–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tan, T.L.; Krusnamurthy, P.A.P.; Nakajima, H.; Rashid, S.A. Adsorptive, kinetics and regeneration studies of fluoride removal from water using zirconium-based metal organic frameworks. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 18740–18752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Zang, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ouyang, G.; Han, R. Enhanced fluoride adsorption from aqueous solution by zirconium (IV)-impregnated magnetic chitosan graphene oxide. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 182, 1759–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Zheng, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, S. Rapid and efficient removal of toxic ions from water using Zr-based MOFs@PIM hierarchical porous nanofibre membranes. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 452, 139198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Wang, J.; Ren, J.; Zhang, M.; Mao, H. Environmentally benign tannin-modified chitosan aerogel decorated with Zr(IV) enabled high-performance adsorption of fluoride. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 519, 165351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mechnou, I.; Oukkass, S.; El Kartouti, A.; Hlaibi, M.; Saleh, N.i.; Alanazi, A.K. High adsorption capacity of diclofenac and paracetamol using OMWW based W-carboxylate doped activated carbon. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 378, 134719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, P.; Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Pan, B. Substitution–Leaching–Deposition (SLD) Processes Drive Reversible Surface Layer Reconstruction of Metal Oxides for Fluoride Adsorption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 3814–3825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.S.; McKay, G. The kinetics of sorption of divalent metal ions onto sphagnum moss peat. Water Res. 2000, 34, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y. Review of second-order models for adsorption systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Guo, X. Rethinking of the intraparticle diffusion adsorption kinetics model: Interpretation, solving methods and applications. Chemosphere 2022, 309, 136732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Febrianto, J.; Kosasih, A.N.; Sunarso, J.; Ju, Y.-H.; Indraswati, N.; Ismadji, S. Equilibrium and kinetic studies in adsorption of heavy metals using biosorbent: A summary of recent studies. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 162, 616–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Shen, J.; Yan, P.; Liu, S.; Kang, J.; Bi, L.; Wang, B.; Zhao, S.; Chen, Z. Preparation of P-doped biochar and its high-efficient removal of sulfamethoxazole from water: Adsorption mechanism, fixed-bed column and DFT study. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 468, 143748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.; Zhang, S.; Hu, S.; Yu, Y.; Han, S.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wei, G.; Gu, Z. Polydopamine and polyethyleneimine comodified carbon fibers/epoxy composites with gradual and alternate rigid-flexible structures: Design, characterizations, interfacial, and mechanical properties. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 4495–4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhou, K.; Liu, X.; Chen, Q.-Z.; Liu, F. Deflouridation efficiency of MgO-LDH prepared by double drop co-precipitation. Chin. J. Nonferr. Met. 2017, 27, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, J. Leaching kinetics of fluorine during the aluminum removal from spent Li-ion battery cathode materials. J. Environ. Sci. 2024, 138, 312–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackwell, J.A.C.; Peter, W. Study of the fluoride adsorption characteristics of porous microparticulate zirconium oxide. J. Chromatogr. 1991, 549, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, M.K.; Verma, D.; Verma, S.K.; Bodhankarb, N.; Sircarc, J.K. Quantitative analysis of inorganic ions in soil employing diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (DRS-FTIR). J. Indian Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, S. Coagulation removal of fluoride by zirconium tetrachloride: Performance evaluation and mechanism analysis. Chemosphere 2019, 218, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dou, X.; Mohan, D.; Pittman, C.U.; Yang, S. Remediating fluoride from water using hydrous zirconium oxide. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 198–199, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, T.; Xiao, Y.; Tian, E.; Wang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Tian, L.; Jiang, H.; Luo, X. Efficient fluoride removal from aqueous solution by synthetic Fe–Mg–La tri-metal nanocomposite and the analysis of its adsorption mechanism. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 738, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ionics | F− | SO42− | Al3+ | Li+ | PO43− | Fe3+ | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | 134.92 | 92,424.20 | 0.02 | 1956.0 | 7.32 | 4.09 | 7.36 |

| Thermophysical Properties | BET Surface Area (m2/g) | Micropore Area (m2/g) | Micropore Volume (cm3/g) | Average Pore Size (nm) | D [4,3] (μm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zirconium-based adsorbent | 3.8892 | 2.0087 | 0.000649 | 14.9227 | 18.5 |

| T (°C) | Langmuir Model | Freundlich Model | Temkin Model | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

(mg/g) | (L/mg) | R2 | (L/mg) | 1/n | R2 | b | R2 | ||

| 25 | 113.3781 | 0.4373 | 0.9640 | 59.6701 | 0.1348 | 0.7234 | 48.3987 | 187.3361 | 0.7898 |

| 35 | 110.1875 | 0.4309 | 0.9770 | 58.7578 | 0.1300 | 0.7295 | 59.5049 | 205.8674 | 0.7971 |

| 45 | 105.9237 | 0.4189 | 0.9776 | 55.9845 | 0.1311 | 0.7702 | 56.6582 | 220.7052 | 0.8332 |

| Absorbent Name | pH | BET Specific Surface Area (m2/g) | Maximum Adsorption Capacity (mg/g) | Adsorption Isotherm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y-Zr-Al [42] | 7.0 | 25 | 31.00 | Langmuir |

| MOF-801 [43] | - | 522 | 17.33 | Langmuir |

| Zr-MCGO [44] | 4–8 | - | 8.84 | Koble-Corrigan |

| La-UiO-66-(COOH)2 [33] | 3–9 | 80.249 | 57.23 | Langmuir |

| Ui-N@PIM-W and Ui-S@PIM-W [45] | 2–10 | 867 and 441 | 38.74 | - |

| CN-Zr composite material [38] | 1–11 | 87.77 | 145.34 | Langmuir |

| BTCA-Zr [46] | 3–10 | - | 86 | Langmuir |

| This work | 7.0 | 113.78 | Langmuir |

| T (°C) | /(kJ/mol) | /(kJ/mol) | /(J/(mol·K)) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | −2.8297 | −8.7657 | −19.9443 |

| 35 | −2.6070 | ||

| 45 | −2.4318 |

| Initial Concentration (mg/L) | Stage I (Boundary Layer Diffusion) | Stage II (Pore Diffusion Dominance) | Stage III (Adsorption Equilibrium) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | R2 | C2 | R2 | C3 | R2 | ||||

| 100 | 15.1124 | 17.1061 | 0.9185 | 7.5224 | 45.1335 | 0.9887 | 0.2081 | 88.1417 | 0.5757 |

| 150 | 14.8612 | 19.6391 | 0.9359 | 9.4991 | 38.8417 | 0.9536 | 0.5614 | 106.8706 | 0.3776 |

| 340 | 23.2163 | 23.2163 | 0.9520 | 7.5139 | 43.2012 | 0.9283 | 0.7650 | 102.8994 | 0.8942 |

| Sample | Peak | Binding Energy/eV | FWHM/eV | Area | Percent/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virgin adsorbent | Zr-O | 530.1 | 1.69 | 38,391.81 | 18.07 |

| Zr-OH | 531.8 | 1.96 | 137,211.27 | 64.58 | |

| H2O | 533.2 | 2.08 | 36,848.82 | 17.34 | |

| F-NaF | Zr-O | 530.3 | 1.31 | 30,638.59 | 42.38 |

| Zr-OH | 531.8 | 1.67 | 36,065.36 | 49.88 | |

| H2O | 533.1 | 1.82 | 5597.37 | 7.74 | |

| F-PO43− | Zr-O | 530.6 | 1.47 | 24,621.10 | 28.49 |

| Zr-OH | 531.8 | 1.52 | 47,655.95 | 55.14 | |

| H2O | 533.0 | 1.84 | 14,143.47 | 16.37 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gong, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, Z.; Jiang, T.; Peng, R.; Wang, J.; Chen, X. Efficient Removal of Fluorine from Leachate of Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Calcine by Porous Zirconium-Based Adsorbent. Materials 2025, 18, 5475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235475

Gong S, Huang H, Wang Y, Liu F, Chen Z, Jiang T, Peng R, Wang J, Chen X. Efficient Removal of Fluorine from Leachate of Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Calcine by Porous Zirconium-Based Adsorbent. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235475

Chicago/Turabian StyleGong, Shengqi, Haijun Huang, Yizheng Wang, Fupeng Liu, Zaoming Chen, Tao Jiang, Ruzhen Peng, Jinliang Wang, and Xirong Chen. 2025. "Efficient Removal of Fluorine from Leachate of Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Calcine by Porous Zirconium-Based Adsorbent" Materials 18, no. 23: 5475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235475

APA StyleGong, S., Huang, H., Wang, Y., Liu, F., Chen, Z., Jiang, T., Peng, R., Wang, J., & Chen, X. (2025). Efficient Removal of Fluorine from Leachate of Spent Lithium Iron Phosphate Calcine by Porous Zirconium-Based Adsorbent. Materials, 18(23), 5475. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235475