Distinct Responses of Corrosion Behavior to the Intermetallic/Impurity Redistribution During Hot Processing in Micro-Alloyed Mg Alloys

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparations

2.2. Microstructure Characterization

2.3. Characterization of Corrosion Performance

3. Results

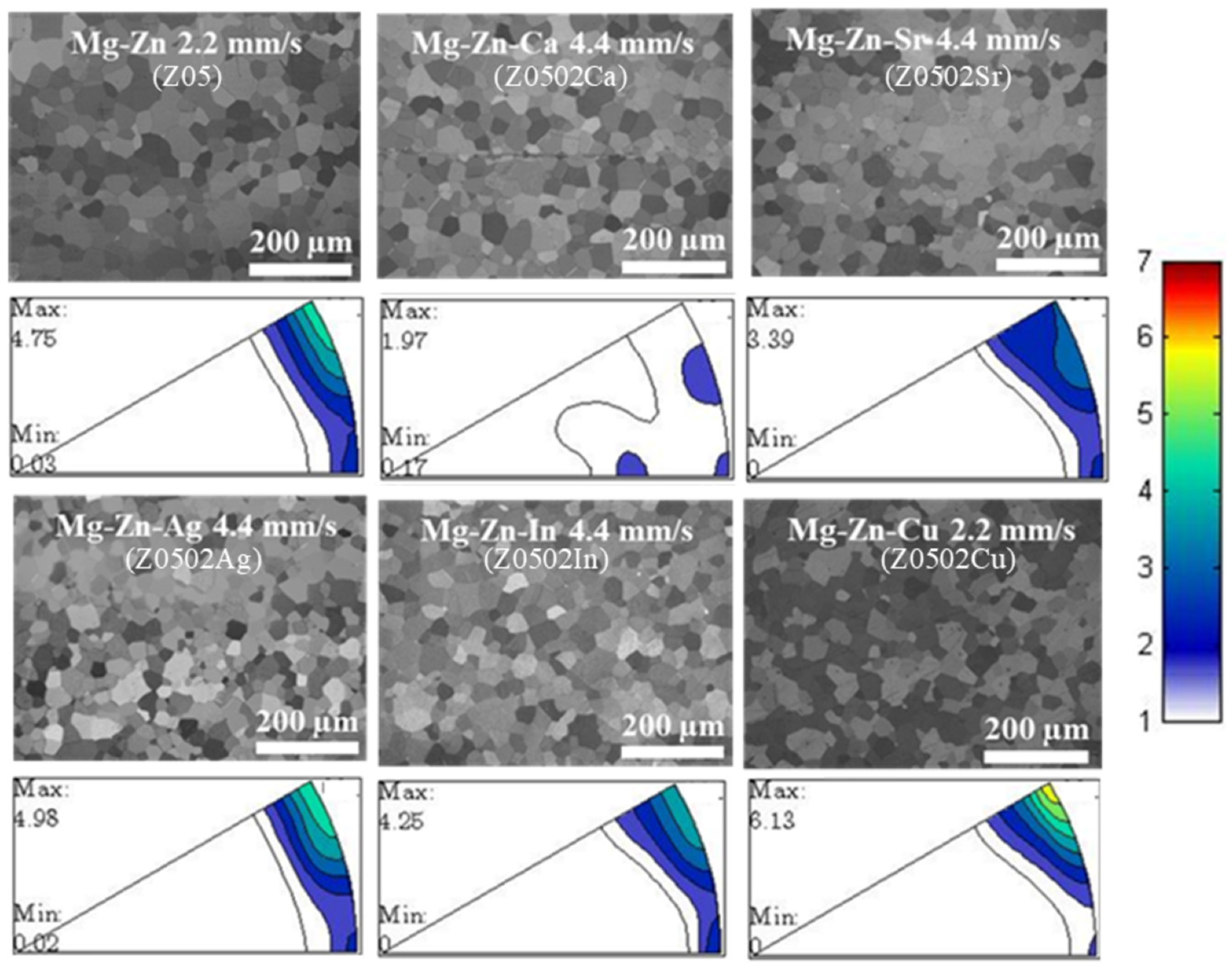

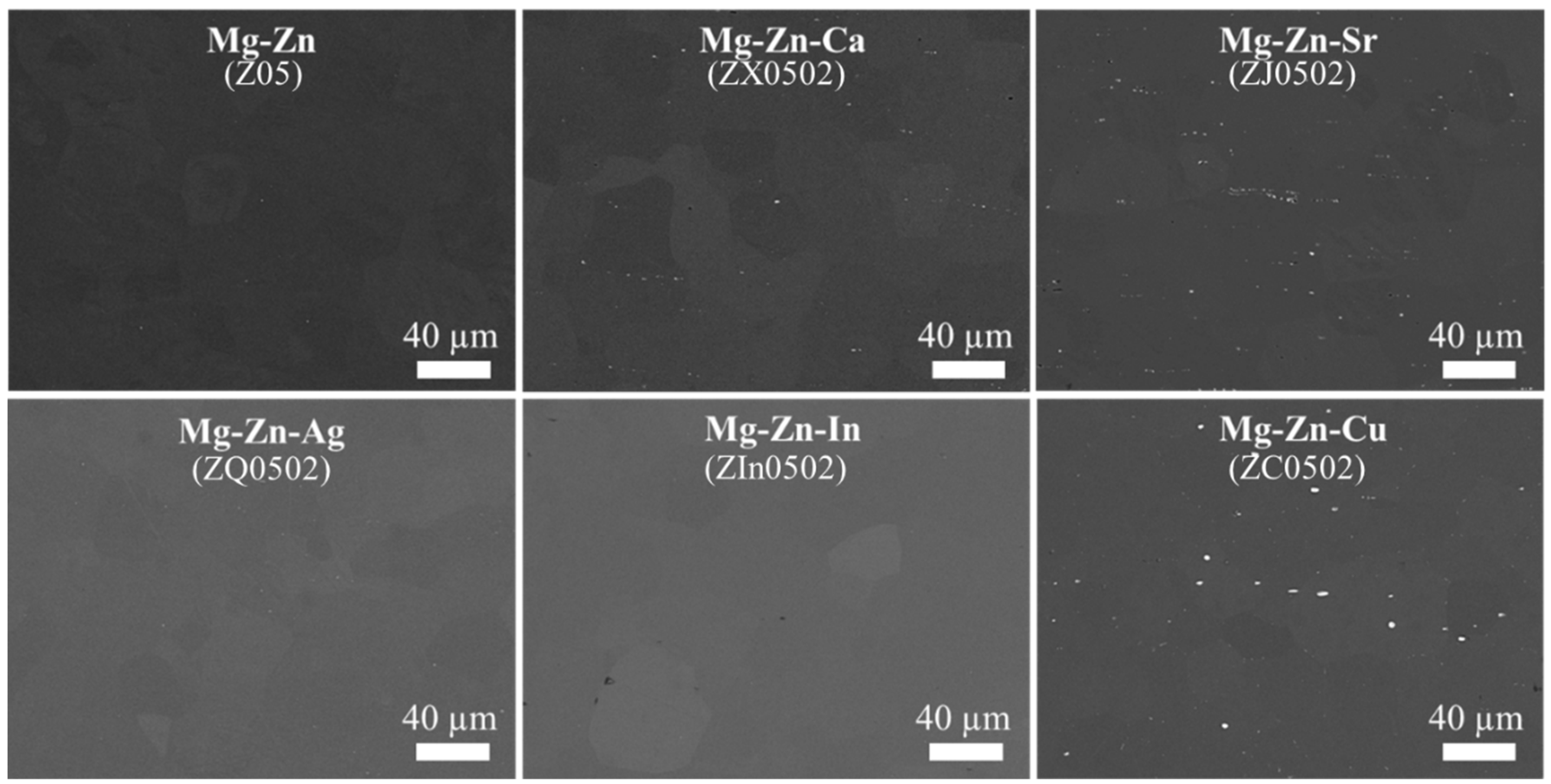

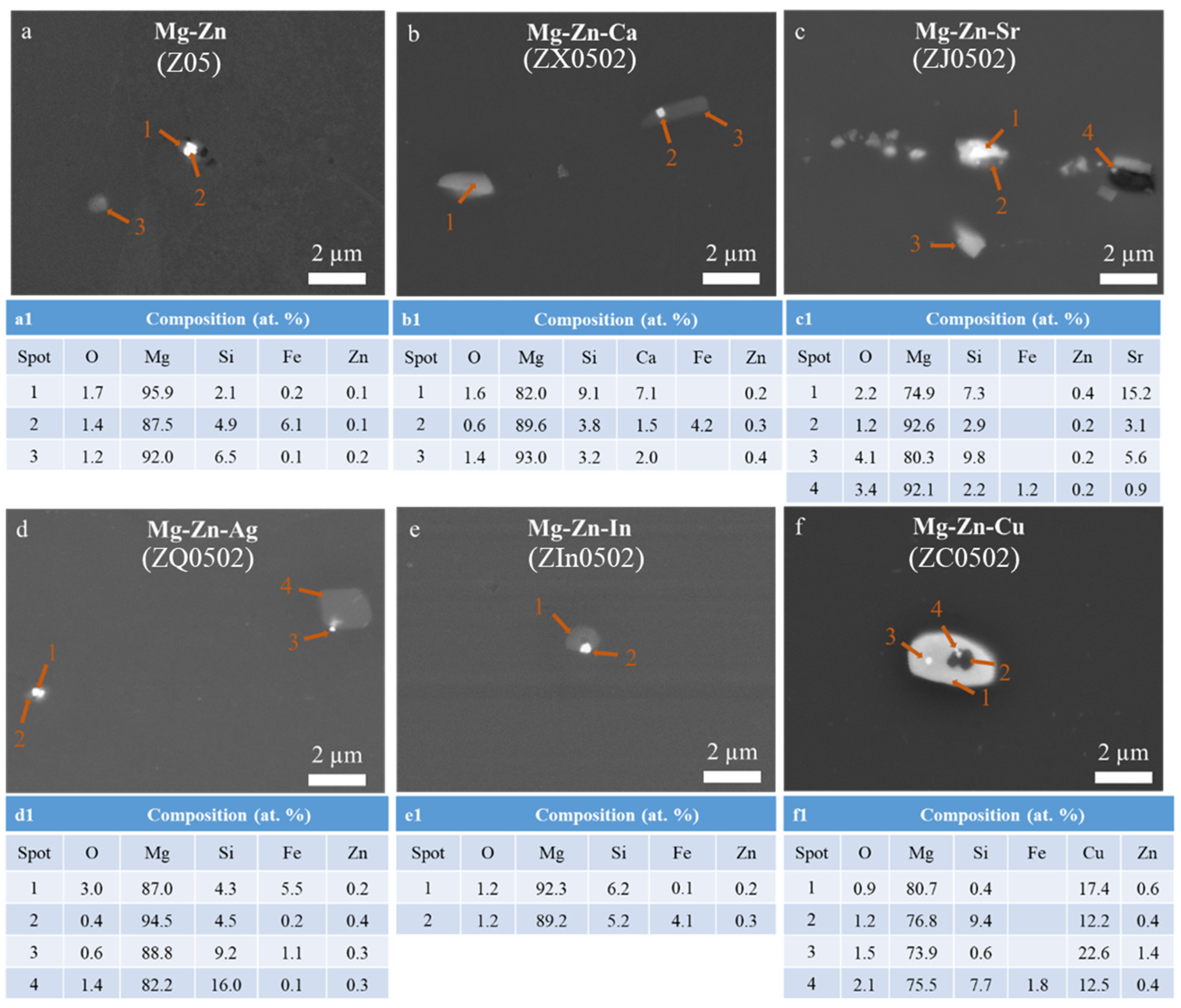

3.1. Microstructure

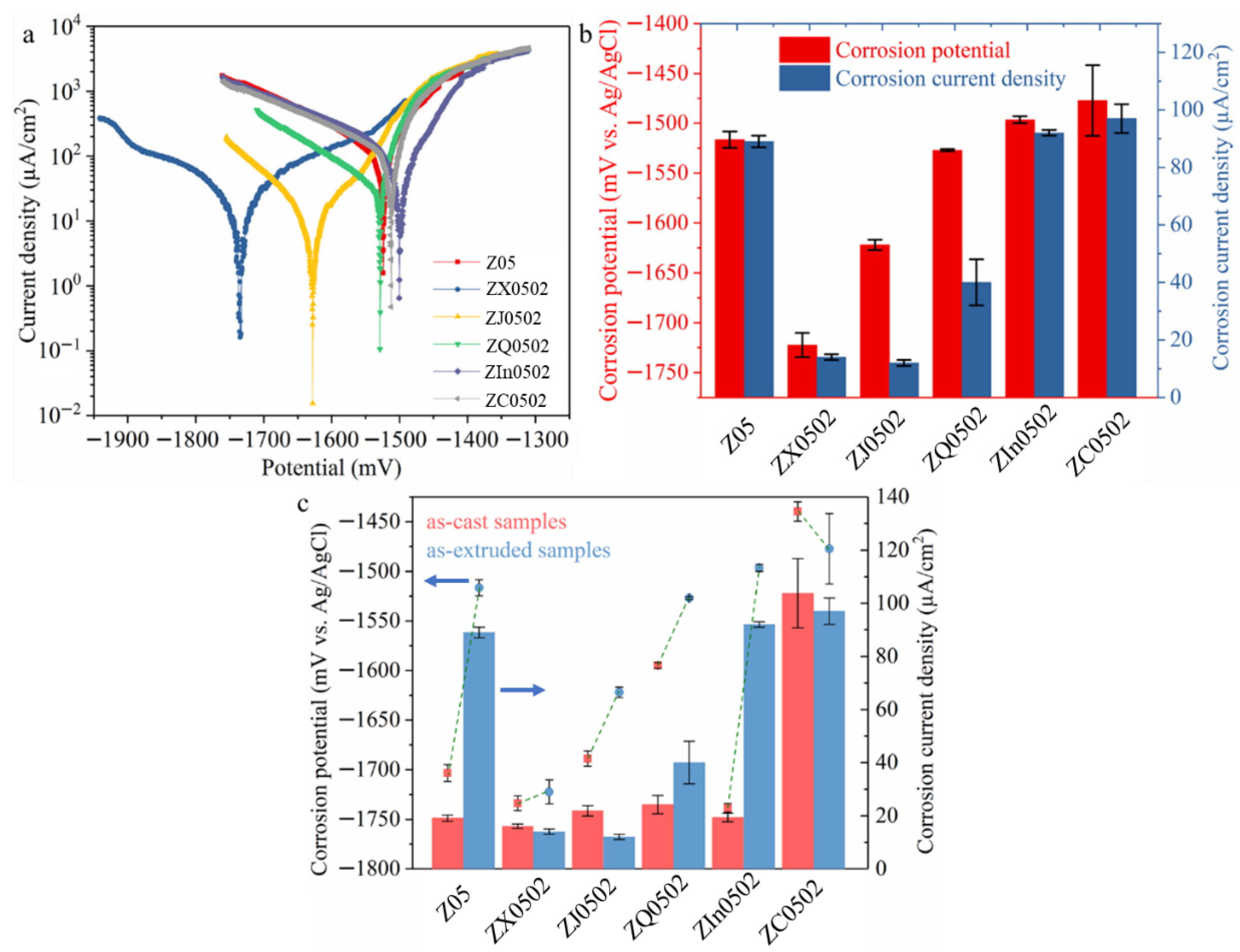

3.2. Corrosion Performance

4. Discussion

4.1. Microstructure

4.2. Corrosion Performance

4.3. Perspective: Design Strategy of Micro-Alloyed Mg Systems

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- After hot processing, the phenomenon of Fe precipitation can be seen in micro-alloyed Mg systems.

- (2)

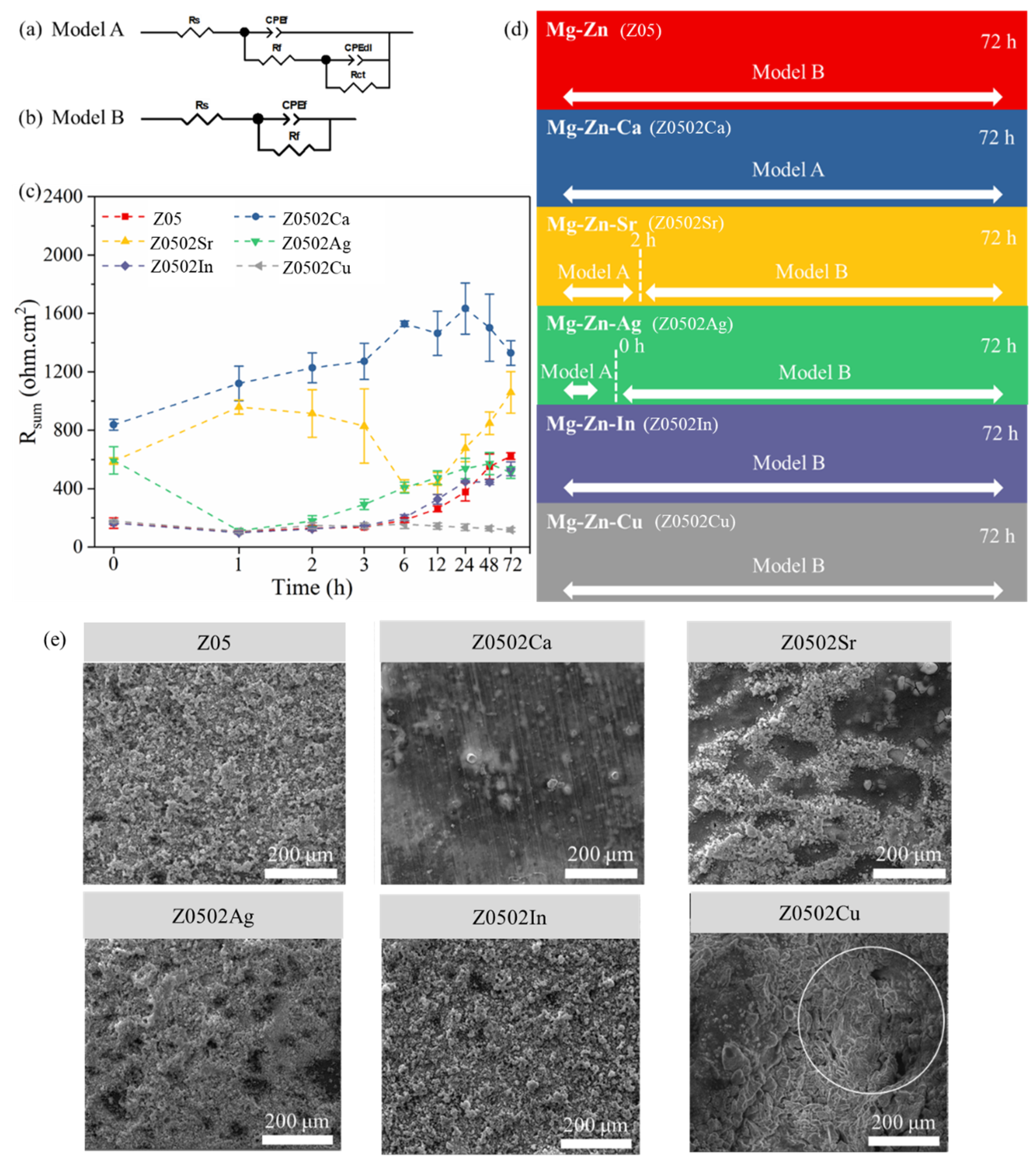

- The corrosion performances of as-extruded Z05, Z0502-Ag and Z0502-In deteriorate distinctly compared to the as-cast states due to the redistribution of Fe precipitates.

- (3)

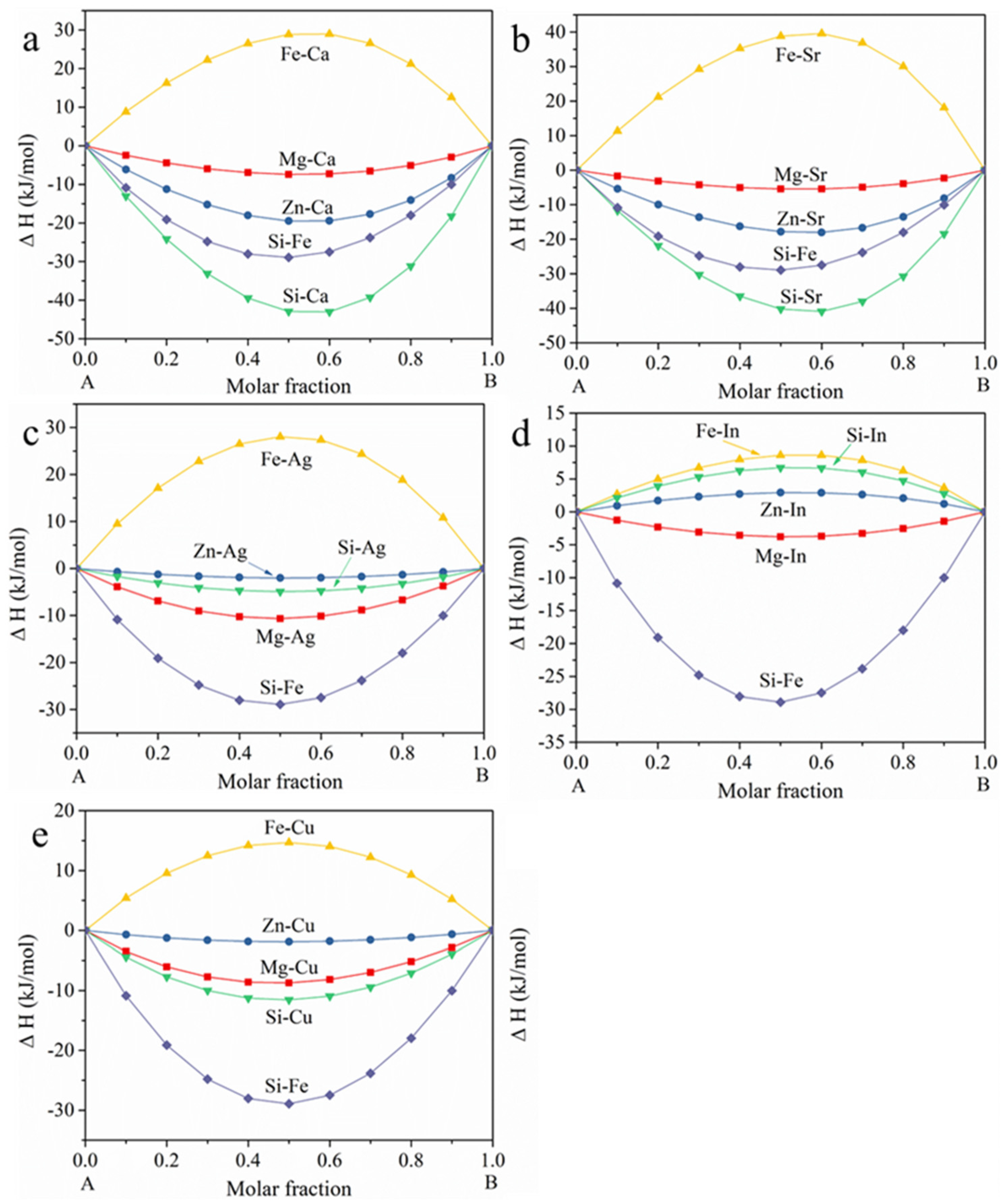

- The influence of Fe precipitation during hot processing is not that severe for Z0502-Ca and Z0502-Sr, mainly resulting from the lower ΔH of Ca-Si and Sr-Si compared to Fe-Si, and the appreciable ΔE of the MgCaSi and MgSrSi phases.

- (4)

- Regarding the corrosion performance of micro-alloyed Mg alloy, ΔH and ΔE of the precipitates are the key factors during hot processing. A corresponding database would be desired in the perspective of material design.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shangguan, F.-e.; Cheng, W.-l.; Chen, Y.-h.; Cui, Z.-q.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.-x.; Wang, L.-f.; Li, H.; Hou, H. Role of micro-Ca/In alloying in tailoring the microstructural characteristics and discharge performance of dilute Mg-Bi-Sn-based alloys as anodes for Mg-air batteries. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 12, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnedenkov, A.S.; Sinebryukhov, S.L.; Filonina, V.S.; Egorkin, V.S.; Ustinov, A.Y.; Sergienko, V.I.; Gnedenkov, S.V. The detailed corrosion performance of bioresorbable Mg-0.8Ca alloy in physiological solutions. J. Magnes. Alloys 2022, 10, 1326–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mahallawy, N.; Palkowski, H.; Klingner, A.; Diaa, A.; Shoeib, M. Effect of 1.0 wt. % Zn addition on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and bio-corrosion behaviour of micro alloyed Mg-0.24Sn-0.04Mn alloy as biodegradable material. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 100999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; She, J.; Chen, D.; Pan, F. Latest research advances on magnesium and magnesium alloys worldwide. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, T.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J.; Deng, B.; Peng, F.; Lin, X.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Zheng, X.; Xiao, J. Effect of homogenization on the microstructure, biocorrosion resistance, and biological performance of as-cast Mg–4Zn–1Ca alloy. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 33, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipan, N.; Pandey, A.; Mishra, P. Selection and preparation strategies of Mg-alloys and other biodegradable materials for orthopaedic applications: A review. Mater. Today Commun. 2022, 31, 103658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Dai, J.; Zhang, X. Improvement of corrosion resistance of magnesium alloys for biomedical applications. Corros. Rev. 2015, 33, 101–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Guan, D.; Tan, X. The relation between heat treatment and corrosion behavior of Mg–Gd–Y–Zr alloy. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1194–1199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, K.D.; Birbilis, N. Effect of grain size on corrosion: A review. Corrosion 2010, 66, 075005-1–075005-13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shunmugasamy, V.C.; Khalid, E.; Mansoor, B. Friction stir extrusion of ultra-thin wall biodegradable magnesium alloy tubes—Microstructure and corrosion response. Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 26, 102129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höche, D.; Blawert, C.; Lamaka, S.V.; Scharnagl, N.; Mendis, C.; Zheludkevich, M.L. The effect of iron re-deposition on the corrosion of impurity-containing magnesium. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 1279–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.L.; Atrens, A. Corrosion mechanisms of magnesium alloys. Adv. Eng. Mater. 1999, 1, 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanawalt, J.D.; Nelson, C.E.; Peloubet, J.A. Corrosion studies of magnesium and its alloys. Trans. AIME 1942, 147, 273–299. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, M.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Nagasekhar, A.V.; Schmutz, P.; Easton, M.; Song, G.-L.; Atrens, A. Calculated phase diagrams and the corrosion of die-cast Mg–Al alloys. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Shi, Z.; Song, G.-L.; Liu, M.; Atrens, A. Corrosion behaviour in salt spray and in 3.5% NaCl solution saturated with Mg(OH)2 of as-cast and solution heat-treated binary Mg–X alloys: X=Mn, Sn, Ca, Zn, Al, Zr, Si, Sr. Corros. Sci. 2013, 76, 60–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Shi, Z.; Song, G.-L.; Liu, M.; Dargusch, M.S.; Atrens, A. Influence of hot rolling on the corrosion behavior of several Mg–X alloys. Corros. Sci. 2015, 90, 176–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Lopez, M.; Pereda, M.D.; del Valle, J.A.; Fernandez-Lorenzo, M.; Garcia-Alonso, M.C.; Ruano, O.A.; Escudero, M.L. Corrosion behaviour of AZ31 magnesium alloy with different grain sizes in simulated biological fluids. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1763–1771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, Y.; Blawert, C.; Yang, H.; Wiese, B.; Bohlen, J.; Mei, D.; Deng, M.; Feyerabend, F.; Willumeit, R. Deteriorated corrosion performance of micro-alloyed Mg-Zn alloy after heat treatment and mechanical processing. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 92, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Shi, Z.; Atrens, A. Production of high purity magnesium alloys by melt purification with Zr. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2012, 14, 477–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, F.; Chen, X.; Yan, T.; Liu, T.; Mao, J.; Luo, W.; Wang, Q.; Peng, J.; Tang, A.; Jiang, B. A novel approach to melt purification of magnesium alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2016, 4, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, U.C.; Blawert, C.; Scharnagl, N.; Dietzel, W.; Kainer, K.U. Influence of inorganic acid pickling on the corrosion resistance of magnesium alloy AZ31 sheet. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2544–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwaogu, U.C.; Blawert, C.; Scharnagl, N.; Dietzel, W.; Kainer, K.U. Effects of organic acid pickling on the corrosion resistance of magnesium alloy AZ31 sheet. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2143–2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawlik, M.M.; Wiese, B.; Welle, A.; González, J.; Desharnais, V.; Harmuth, J.; Ebel, T.; Willumeit-Römer, R. Acetic acid etching of Mg-xGd alloys. Metals 2019, 9, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Zhou, X.; Hashimoto, T.; Thompson, G.E.; Scamans, G.; Fan, Z. Investigation of the microstructure and the influence of iron on the formation of Al8Mn5 particles in twin roll cast AZ31 magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 628, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Liang, S.-M.; Schmid-Fetzer, R.; Fan, Z.; Scamans, G.; Robson, J.; Thompson, G. Effect of traces of silicon on the formation of Fe-rich particles in pure magnesium and the corrosion susceptibility of magnesium. J. Alloys Compd. 2015, 619, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, G.; Lee, J.-Y.; Kim, Y.-C.; Park, J.H.; Kim, D.-I.; Han, H.-S.; Yang, S.-J.; Seok, H.-K. Preferred crystallographic pitting corrosion of pure magnesium in Hanks’ solution. Corros. Sci. 2012, 63, 316–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, J.; Martinelli, E.; Weinberg, A.M.; Becker, M.; Mingler, B.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. Assessing the degradation performance of ultrahigh-purity magnesium in vitro and in vivo. Corros. Sci. 2015, 91, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsubara, H.; Ichige, Y.; Fujita, K.; Nishiyama, H.; Hodouchi, K. Effect of impurity Fe on corrosion behavior of AM50 and AM60 magnesium alloys. Corros. Sci. 2013, 66, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Song, G.-L. Impurity control and corrosion resistance of magnesium–aluminum alloy. Corros. Sci. 2013, 77, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Blawert, C.; Yang, H.; Wiese, B.; Feyerabend, F.; Bohlen, J.; Mei, D.; Deng, M.; Campos, M.S.; Scharnagl, N.; et al. Microstructure-corrosion behaviour relationship of micro-alloyed Mg-0.5Zn alloy with the addition of Ca, Sr, Ag, In and Cu. Mater. Des. 2020, 195, 108980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandat Software Package for Calculating Phase Diagrams and Thermodynamic Properties of Multi-Component Alloys; CompuTherm LLC: Middleton, WI, USA, 2017.

- Nayeb-Hashemi, A.A.; Clark, J.B. Phase Diagram of Binary Magnesium Alloys; ASM International: Novelty, OH, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, H. Grain size measurement by the intercept method. Metallography 1971, 4, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, F.; Hielscher, R.; Schaeben, H. Texture analysis with MTEX—Free and open source software toolbox. Solid State Phenom. 2010, 160, 63–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Fan, P.; Han, Q. Models of activity and activity interaction parameter in ternary metallic melt. Acta Metall. Sin. 1994, 30, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Miedema, A.R.; de Châtel, P.F.; de Boer, F.R. Cohesion in alloys—Fundamentals of a semi-empirical model. Physica B+C 1980, 100, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Huang, Y.; Tolnai, D.; Kainer, K.U.; Dieringa, H. Influences of Al and high shearing dispersion technique on the microstructure and creep resistance of Mg-2.85Nd-0.92Gd-0.41Zr-0.29Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 764, 138215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wei, Q. Effects of Zr Addition on Thermodynamic and Kinetic Properties of Liquid Mg-6Zn-xZr Alloys. Metals 2019, 9, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Shi, Z.; Hofstetter, J.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Song, G.; Liu, M.; Atrens, A. Corrosion of ultra-high-purity Mg in 3.5% NaCl solution saturated with Mg(OH)2. Corros. Sci. 2013, 75, 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Zhao, C.; Xie, C.; Zhang, X. Influence of heat treatments on in vitro degradation behavior of Mg-6Zn alloy studied by electrochemical measurements. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2010, 12, B170–B174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- op’t Hoog, C.; Birbilis, N.; Estrin, Y. Corrosion of pure Mg as a function of grain size and processing route. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2008, 10, 579–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aung, N.N.; Zhou, W. Effect of grain size and twins on corrosion behaviour of AZ31B magnesium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 589–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohlen, J.; Meyer, S.; Wiese, B.; Luthringer-Feyerabend, B.J.C.; Willumeit-Römer, R.; Letzig, D. Alloying and processing effects on the microstructure, mechanical properties, and degradation behavior of extruded magnesium alloys containing calcium, cerium, or silver. Materials 2020, 13, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkland, N.T.; Birbilis, N.; Staiger, M.P. Assessing the corrosion of biodegradable magnesium implants: A critical review of current methodologies and their limitations. Acta Biomater. 2012, 8, 925–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Z.; He, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, G.; Wu, R.; Jin, S.; Wang, J.; Lu, Z.; Yang, Z.; et al. Effect of I-Phase on Microstructure and Corrosion Resistance of Mg-8.5Li-6.5Zn-1.2Y Alloy. Materials 2023, 16, 3007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.F.M.; Sheikh, A.K.; Qamar, S.Z.; Raza, M.K.; Al-Fuhaid, K.M. Product defects in aluminum extrusion and their impact on operational cost. In Proceedings of the 6th Saudi Engineering Conference, Dhahran, Saudi Arabia, 14–17 December 2002; pp. 137–154. [Google Scholar]

- Doležal, P.; Zapletal, J.; Fintová, S.; Trojanová, Z.; Greger, M.; Roupcová, P.; Podrábský, T. Influence of processing techniques on microstructure and mechanical properties of a biodegradable Mg-3Zn-2Ca alloy. Materials 2016, 9, 880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-b.; Shan, D.-y.; Song, Y.-w.; Han, E.-h. Effects of heat treatment on corrosion behaviors of Mg-3Zn magnesium alloy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2010, 20, 1345–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, R.; Wang, Y.-P.; Yang, Y.; Luo, D.-M.; Meng, H.; Ma, L.; Tang, B.-Y. Structural and mechanical properties of ternary MgCaSi phase: A study by density functional theory. J. Chem. Res. 2020, 44, 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balducci, G.; Brutti, S.; Ciccioli, A.; Gigli, G.; Trionfetti, G.; Palenzona, A.; Pani, M. Vapor pressures and thermodynamic properties of strontium silicides. Intermetallics 2006, 14, 578–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Pan, F.; Mao, J.; Xu, X.; Yan, T. Microstructure, electromagnetic shielding effectiveness and mechanical properties of Mg–Zn–Cu–Zr alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2015, 197, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, J.; Zhong, L. On the microstructure and mechanical property of as-extruded Mg–Sn–Zn alloy with Cu addition. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 744, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, M.; Pekguleryuz, M. The influence of Sr on the microstructure and texture evolution of rolled Mg–1%Zn alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2011, 529, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gusieva, K.; Davies, C.H.J.; Scully, J.R.; Birbilis, N. Corrosion of magnesium alloys: The role of alloying. Int. Mater. Rev. 2015, 60, 169–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Y.; Geng, L.; Lu, C. Effects of calcium on texture and mechanical properties of hot-extruded Mg–Zn–Ca alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2012, 539, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Shi, X.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, G.; Kamado, S. Texture weakening and ductility variation of Mg–2Zn alloy with CA or RE addition. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2015, 645, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezbahul-Islam, M.; Mostafa, A.O.; Medraj, M. Essential magnesium alloys binary phase diagrams and their thermochemical data. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 2014, 704283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Hamu, G.; Eliezer, D.; Shin, K.S. The role of Si and Ca on new wrought Mg–Zn–Mn based alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 447, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreatta, F.; Apachitei, I.; Kodentsov, A.A.; Dzwonczyk, J.; Duszczyk, J. Volta potential of second phase particles in extruded AZ80 magnesium alloy. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 3551–3557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawar, S.; Zhou, X.; Thompson, G.E.; Scamans, G.; Fan, Z. The Role of Intermetallics on the Corrosion Initiation of Twin Roll Cast AZ31 Mg Alloy. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2015, 162, C442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, S.K.; Suh, B.-C.; Kim, N.R.; Kim, H.S.; Yim, C.D. The corrosion behavior of high purity Mg according to process history. In Magnesium Technology 2020; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 225–230. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, Y.; Guan, L.; Ye, L.; Guo, X. The microstructure and corrosion resistance of as-extruded Mg-6Gd-2Y- (0–1.5) Nd-0.2Zr alloys. Mater. Des. 2020, 186, 108289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralston, K.D.; Birbilis, N.; Davies, C.H.J. Revealing the relationship between grain size and corrosion rate of metals. Scripta Mater. 2010, 63, 1201–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shao, Y.; Meng, G.; Cui, Z.; Wang, F. Corrosion of hot extrusion AZ91 magnesium alloy: I-relation between the microstructure and corrosion behavior. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 1960–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, P.-R.; Han, H.-S.; Yang, G.-F.; Kim, Y.-C.; Hong, K.-H.; Lee, S.-C.; Jung, J.-Y.; Ahn, J.-P.; Kim, Y.-Y.; Cho, S.-Y.; et al. Biodegradability engineering of biodegradable Mg alloys: Tailoring the electrochemical properties and microstructure of constituent phases. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Guo, C.; Chai, L.; Sherman, V.R.; Qin, X.; Ding, Y.; Meyers, M.A. Mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of hot extruded Mg–2.5Zn–1Ca alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2015, 195, 50–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagihara, K.; Okubo, M.; Yamasaki, M.; Nakano, T. Crystal-orientation-dependent corrosion behaviour of single crystals of a pure Mg and Mg-Al and Mg-Cu solid solutions. Corros. Sci. 2016, 109, 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, G.-L.; Mishra, R.; Xu, Z. Crystallographic orientation and electrochemical activity of AZ31 Mg alloy. Electrochem. Commun. 2010, 12, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-R.; Zhang, C.; Pan, H.-C.; Wang, Y.-X.; Ren, Y.-P.; Qin, G.-W. Microstructures and bio-corrosion resistances of as-extruded Mg–Ca alloys with ultra-fine grain size. Rare Met. 2017, 42, 680–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambat, R.; Aung, N.N.; Zhou, W. Evaluation of microstructural effects on corrosion behaviour of AZ91D magnesium alloy. Corros. Sci. 2000, 42, 1433–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.-H.; Tan, L.-L.; Ren, Y.-B.; Yang, K. Effect of Microstructure on Corrosion Behavior of Mg–Sr Alloy in Hank’s Solution. Acta Metall. Sin. (Engl. Lett.) 2019, 32, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, M.; Eom, K.; Kyung, J.; Kim, D.; Cho, E.; Kwon, H. Design of Mg-Cu alloys for fast hydrogen production, and its application to PEM fuel cell. J. Alloys Compd. 2018, 741, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esmaily, M.; Svensson, J.E.; Fajardo, S.; Birbilis, N.; Frankel, G.S.; Virtanen, S.; Arrabal, R.; Thomas, S.; Johansson, L.G. Fundamentals and advances in magnesium alloy corrosion. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 89, 92–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, J.; Martinelli, E.; Pogatscher, S.; Schmutz, P.; Povoden-Karadeniz, E.; Weinberg, A.M.; Uggowitzer, P.J.; Löffler, J.F. Influence of trace impurities on the in vitro and in vivo degradation of biodegradable Mg–5Zn–0.3Ca alloys. Acta Biomater. 2015, 23, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bahmani, A.; Arthanari, S.; Shin, K.S. Corrosion behavior of Mg–Mn–Ca alloy: Influences of Al, Sn and Zn. J. Magnes. Alloys 2019, 7, 38–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, M.; Thierry, D.; LeBozec, N. The influence of microstructure on the corrosion behaviour of AZ91D studied by scanning Kelvin probe force microscopy and scanning Kelvin probe. Corros. Sci. 2006, 48, 1193–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willumeit, R.; Feyerabend, F.; Huber, N. Magnesium degradation as determined by artificial neural networks. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 8722–8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Element | Ca | Sr | Ag | Cu | In |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biocompatibility | Beneficial for bone regeneration and suppressing bone resorption | The released Ag+ and Cu2+ have antibacterial effect | Commonly added in alloys for dental materials | ||

| Maximal solubility in Mg (wt.%) | 1.34 | 0.11 | 15 | 0.0034 | 53 |

| Element | Z05 | ZX0502 | ZJ0502 | ZQ0502 | ZIn0502 | ZC0502 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zn (wt.%) | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.51 ± 0.02 | 0.48 ± 0.02 | 0.50 ± 0.02 | 0.49 ± 0.02 | 0.47 ± 0.02 |

| X (wt.%) | - | 0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.02 | 0.20 ± 0.01 |

| Mn (ppm) | 169 ± 5 | 200 ± 5 | 186 ± 5 | 168 ± 5 | 171 ± 5 | 174 ± 5 |

| Si (ppm) | 67 ± 4 | 137 ± 4 | 154 ± 4 | 140 ± 4 | 57 ± 4 | 59 ± 4 |

| Al (ppm) | 32 ± 5 | 52 ± 5 | 130 ± 5 | 146 ± 5 | 81 ± 5 | 55 ± 5 |

| Fe (ppm) | 13 ± 6 | 22 ± 6 | 13 ± 6 | 13 ± 6 | 12 ± 6 | 7 ± 6 |

| Cu (ppm) | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | - |

| Ni (ppm) | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 |

| Be (ppm) | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 | <3 |

| Speed | 0.6 mm/s | 2.2 mm/s | 4.4 mm/s | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alloy | ||||

| Z05 | 26 ± 1 µm | 30 ± 1 µm | 31 ± 1 µm | |

| Z0502Ca | 7 ± 1 µm | 20 ± 1 µm | 30 ± 2 µm | |

| Z0502Sr | 23 ± 2 µm | 26 ± 0 µm | 31 ± 1 µm | |

| Zn0502Ag | 24 ± 0 µm | 26 ± 0 µm | 29 ± 1 µm | |

| Z0502In | 24 ± 0 µm | 27 ± 2 µm | 30 ± 2 µm | |

| Z0502Cu | 22 ± 1 µm | 32 ± 1 µm | 37 ± 1 µm | |

| Alloy | As-Cast | EX | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intermetallics | Intermetallics | Form of Fe Impurity | |

| Z05 | Mg2Si, MgZn | Mg2Si | Fe-Si |

| Z0502-Ca | Mg2Ca, Ca2Mg6Zn3, MgCaSi | MgCaSi | MgCaSi(Fe) |

| Z0502-Sr | MgSrSi(Zn), SiSr2(Zn) | MgSrSi, Si2Sr | MgSrSi(Fe), Si2Sr(Fe) |

| Z0502-Ag | Mg2Si, Zn5Ag | Mg2Si | Fe-Si |

| Z0502-In | Mg2Si, MgZn | Mg2Si | Fe-Si |

| Z0502-Cu | Mg2Si, MgZnCu | Mg2Cu, Mg2Si, MgSiCu, MgZnCu | Fe-Si |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jin, Y.; Yang, H.; Bohlen, J.; Wiese, B.; Su, Y. Distinct Responses of Corrosion Behavior to the Intermetallic/Impurity Redistribution During Hot Processing in Micro-Alloyed Mg Alloys. Materials 2025, 18, 5473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235473

Jin Y, Yang H, Bohlen J, Wiese B, Su Y. Distinct Responses of Corrosion Behavior to the Intermetallic/Impurity Redistribution During Hot Processing in Micro-Alloyed Mg Alloys. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235473

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Yiming, Hong Yang, Jan Bohlen, Björn Wiese, and Yan Su. 2025. "Distinct Responses of Corrosion Behavior to the Intermetallic/Impurity Redistribution During Hot Processing in Micro-Alloyed Mg Alloys" Materials 18, no. 23: 5473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235473

APA StyleJin, Y., Yang, H., Bohlen, J., Wiese, B., & Su, Y. (2025). Distinct Responses of Corrosion Behavior to the Intermetallic/Impurity Redistribution During Hot Processing in Micro-Alloyed Mg Alloys. Materials, 18(23), 5473. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235473