Increasing Cathode Potential of Homogeneous Low Voltage Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) to Increase Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polycarbonate and Characterization by XPS C1s and O1s Peaks

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Procedure

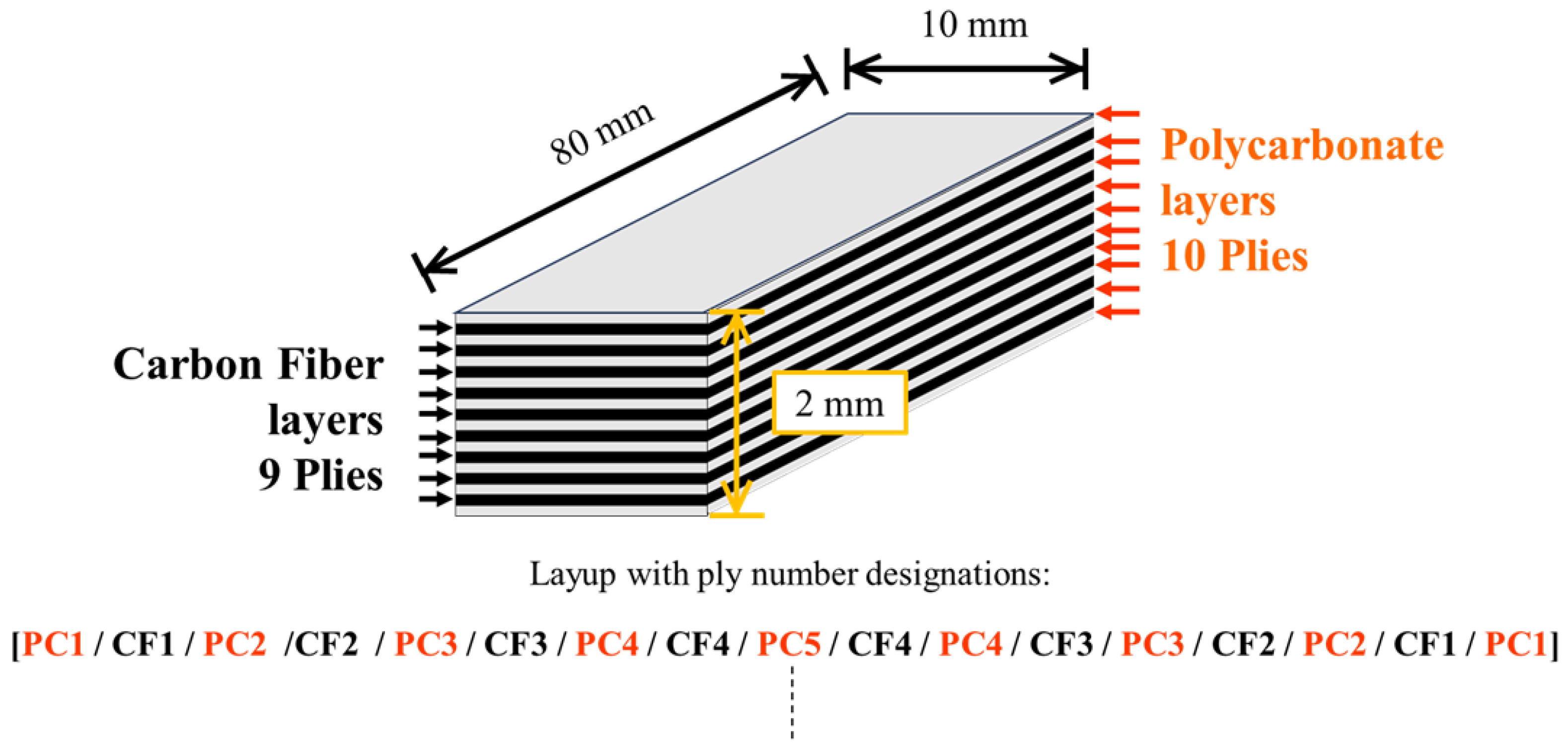

2.1. Composite Fabrication

2.2. Conditions of HLEBI

2.3. Penetration Depth, Dth, and Calculations for Interlayered Samples

=(10−5 m) × (4540 kgm−3)/[66.7 × (Vc)2/3] = 24.1 kV

= (25 × 10−3 m) × (1.13 kgm−3)/[66.7 × (Vc − ΔVTi)2/3] = 16.9 kV

2.4. Charpy Impact Test

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (EDS)

2.6. X-Ray Spectroscopy (XPS)

3. Results

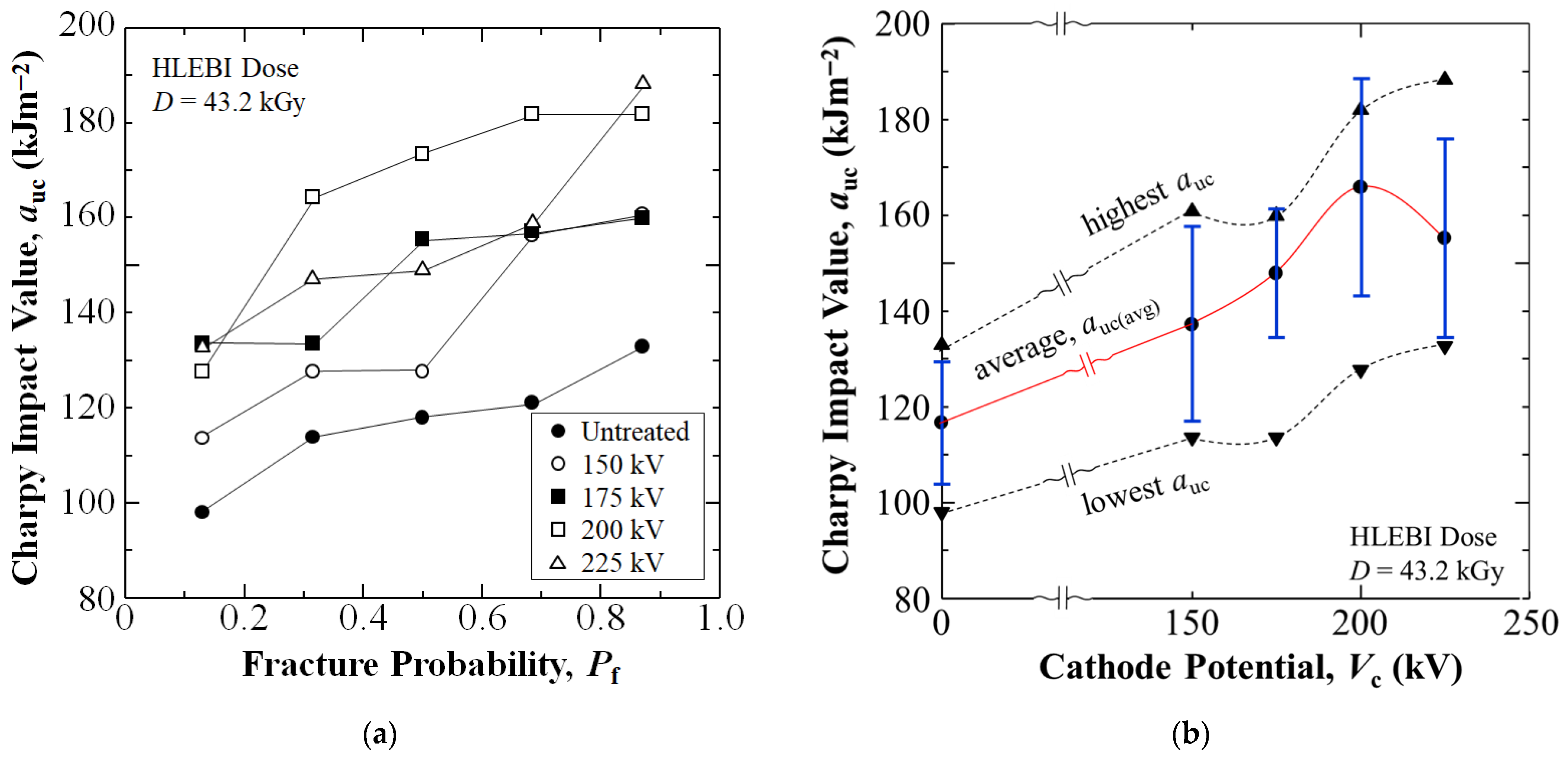

3.1. Impact Strengthening

3.2. Fracture Surface Observation by SEM and EDS

4. Discussion

4.1. Penetration Depth, Dth, by HLEBI

=(7.5 × 10−5 m) × (1200 kgm−3)/[66.7 × (Vc − ΔVTi − ΔV PC1)2/3] = 59.1 kV

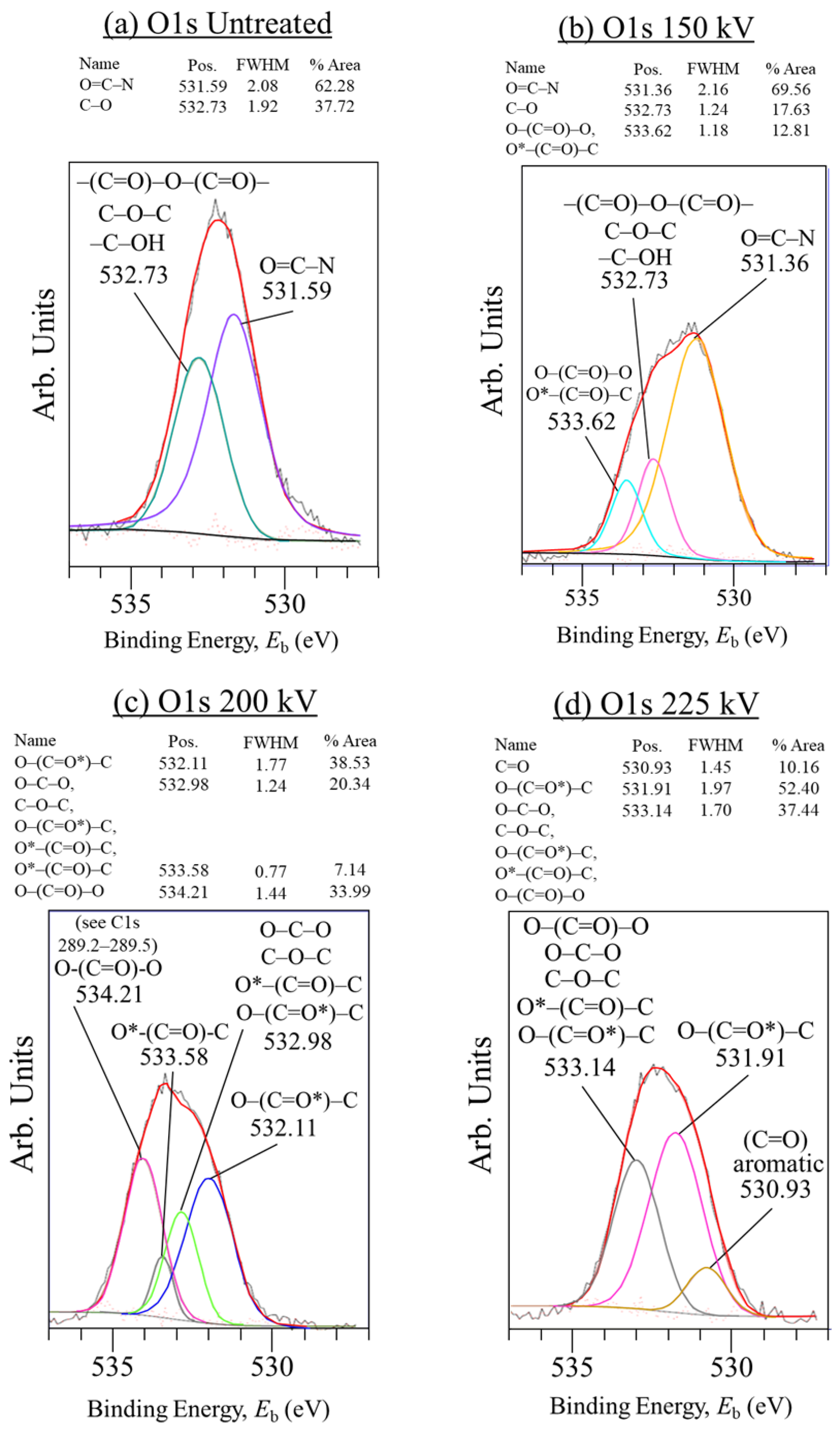

4.2. XPS C1s and O1s Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- New Space Economy: Business, Technology and Trends. Available online: https://newspaceeconomy.ca/2024/05/06/launch-vehicle-fairings-protecting-precious-payloads/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Sage Zander, Ltd. Carbon Fiber in Space. Available online: https://sagezander.com/carbon-fibre-composite-cfrp-space-rocket/ (accessed on 3 October 2025).

- Pang, J.; Fancey, K. Analysis of the tensile behaviour of viscoelastically prestressed polymeric matrix composites. Compos. Sci. Tech. 2008, 68, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motahari, S.; Cameron, J. Impact Strength of Fiber Pre-Stressed Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 1998, 17, 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motahari, S.; Cameron, J. Fibre Prestressed Composites: Improvement of Flexural Properties through Fibre Prestressing. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 1999, 18, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, A.S.; Ashton, J.N. On the influence of pre-stress on the mechanical properties of a unidirectional GRE composite. Compos. Struct. 1997, 40, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Okada, T.; Okada, S.; Hirano, M.; Matsuda, M.; Matsuo, A.; Faudree, M.C. Effects of Tensile Prestress Level on Impact Value of 50 vol% Continuous Unidirectional 0 Degree Oriented Carbon Fiber Reinforced Epoxy Polymer (CFRP). Mater. Trans. 2014, 55, 318–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-G.; Wang, C.Y.; Zhang, J.N.; Wu, H.-H. Experimental and theoretical investigation on tensile properties and fracture behavior of carbon fiber composite laminates with varied ply thickness. Compos. Struct. 2020, 249, 112543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.; Hazell, P.J.; Wang, H.; Escobedo, J.P. Shock response of unidirectional carbon fibre-reinforced polymer composites: Influence of fibre orientation and volume fraction. Compos. B 2025, 299, 112438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, K.; Tay, T.E.; Tan, V.B.C.; Haris, A.; Chew, E.; Pham, V.N.H.; Huang, J.Z.; Raju, K.; Sugahara, T.; Fujihara, K.; et al. Improving the impact performance and residual strength of carbon fibre reinforced polymer composite through intralaminar hybridization. Compos Part A 2023, 171, 107590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlay, J.G.; Waas, A.M.; Bartley-Cho, J.; Muraliraj, N. Combined loading of unreinforced and Z-pin reinforced composite pi joints: An experimental and numerical study. Compos. Part B 2024, 287, 111796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, X.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hui, X.; Liu, W.; Ma, C. Improving Mode II delamination resistance of curved CFRP laminates by a Pre-Hole Z-pinning (PHZ) process. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2023, 36, 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouritz, A.P. Review of z-pinned laminates and sandwich composites. Compos. Part A 2020, 139, 106128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Gao, S.; Mäder, E.; Sharma, H.; Wei, L.Y.; Bijwe, J. Carbon fiber surfaces and composite interphases. Compos. Sci. Tech. 2014, 102, 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, H.; Qi, M.; Yu, Y.; Xu, X.; Hu, J.; Chen, J.; Lin, J. Laser-induced synergistic modifications to enhance mode-I fracture toughness for adhesively bonded thermoset CFRP joints. Compos. Comm. 2025, 59, 102590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Duan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, J.; Liu, X. Cold plasma-coupled nano-lubricant minimum quantity lubrication micro-milling for CFRP removal mechanism study and machining performance evaluation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2026, 716, 164651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilsiz, N. Plasma surface modification of carbon fibers: A review. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2000, 14, 975–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J.D.H. The carbon fibre/epoxy interface—A review. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1999, 41, 13–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senol, H.; Ulus, H.; Al-Nadhari, A.; Topal, D.; Yildiz, M. Meliorating tensile and fracture performance of carbon fiber-epoxy composites via atmospheric plasma activation: Insights into damage modes through in-situ acoustic emission inspection. Comps. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2025, 195, 108929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayne, D.J.; Singleton, M.; Patterson, B.A.; Knorr, D.B.; Stojcevski, F.; Henderson, L.C. Carbon fiber surface treatment for improved adhesion and performance of polydicyclopentadiene composites synthesized by ring opening metathesis polymerization. Compos. Commun. 2024, 47, 101872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Seo, M.K.; Rhee, K.Y. Effect of Ar+ ion beam irradiation on the physicochemical characteristics of carbon fibers. Carbon 2003, 41, 579–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L. Effect of g-ray irradiation grafting on the carbon fibers and interfacial adhesion of epoxy composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Huang, Y.D.; Fu, S.Y.; Yang, L.H.; Qu, H.; Wu, G. Study on the surface performance of carbon fibres irradiated by g -ray under different irradiation dose. App. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 2000–2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Bijwe, J.; Panier, S. Gamma radiation treatment of carbon fabric to improve the fiber–matrix adhesion and tribo-performance of composites. Wear 2011, 271, 2184–2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Lee, J.R. Bending fracture and acoustic emission studies on carbon– carbon composites: Effect of sizing treatment on carbon fibres. J. Mater. Sci. 1998, 33, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.J.; Jang, Y.S. Interfacial characteristics and fracture toughness of electrolytically Ni-plated carbon fiber-reinforced phenolic resin matrix composites. Colloid Interf. Sci. 2001, 237, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Ishii, S.; Inui, S.; Kasai, A.; Faudree, M.C. Impact value of CFRP/Ti joint reinforced by nickel coated carbon fiber. Mater Trans. 2014, 55, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramanathan, T.; Bismarck, A.; Schulz, E.; Subramanian, K. Investigation on the influence of acidic and basic surface groups on carbon fibres on the interfacial shear strength in an epoxy matrix by mean of single fibre pull-out test. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2001, 61, 599–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Wang, R.; Wu, X.; Zhang, D.; Chen, Y. Improvements of adhesion strength of water-based epoxy resin on carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) composites via building surface roughness using modified silica particles. Compos. Part A 2023, 169, 107511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.Q.; Zhou, D.M.; Shiu, K.K. Permeability and permselectivity of polyohenylenediamine films synthesized at a palladium disk electrode. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 52, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, K.B.; Li, J.; Fan, Q.; Chen, Z.H. The enhancement of carbon fiber modified with electropolymer coating to the mechanical properties of epoxy resin composites. Compos. Part A 2008, 39, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zinger, B.; Shkolnik, S.; Hoecker, H. Electrocoating of carbon fibres with polyaniline and poly(hydroxyalkyl methacrylates. Polymer 1989, 30, 628–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashkovan, I.A.; Korabelnikov, Y.G. The effect of fiber surface treatment on its strength and adhesion to the matrix. Compos. Sci. Technol. 1997, 57, 1017–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishitani, A. Application of X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy to surface analysis of carbon fiber. Carbon 1981, 19, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Minary-Jolandan, M.; Naraghi, M. Controlling the wettability and adhesion of carbon fibers with polymer interfaces via grafted nanofibers. Comp. Sci. Tech. 2015, 117, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulyás, J.; Földes, E.; Lázár, A.; Pukánszky, B. Electrochemical oxidation of carbon fibres: Surface chemistry and adhesion. Compos. Part A 2001, 32, 353–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.J.; Wang, J.L.; Cai, X.P. The effect of electrolyte on surface composite and microstructure of carbon fiber by electrochemical treatment. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2013, 8, 2806–2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Tian, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liang, J. Interfacial and mechanical properties of carbon fibers modified by electrochemical oxidation in (NH4HCO3)/(NH4)2C2O4H2O aqueous compound solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2010, 256, 6199–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Gu, A.; Liang, G.; Yuan, L. Effect of the surface roughness on interfacial properties of carbon fibers reinforced epoxy resin composites. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2011, 257, 4069–4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Chen, G. Influence of rare earth treatment on interfacial properties of carbon fiber/epoxy composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2007, 444, 170–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, C.; Liu, L. Surface characteristics of rare earth treated carbon fibers and interfacial properties of composites. J. Rare Earths 2007, 25, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Fan, X.; Yan, C.; Li, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, X.; Yu, L. Interfacial microstructure and properties of carbon fiber composites modified with graphene oxide. Appl. Mater. Interf. 2012, 4, 1543–1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Greenhalgh, E.S.; Shaffer, M.S.P.; Bismarck, A. Carbon nanotube-based hierarchical composites: A review. J. Mater. Chem. 2010, 20, 4729–4756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, H.D. Nanotube-polymer adhesion: A mechanics approach. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2002, 361, 57–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Sager, R.; Dai, L.; Baur, J. Hierarchical composites of carbon nanotubes on carbon fiber: Influence of growth condition on fiber tensile properties. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 594–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sager, R.J.; Klein, P.J.; Lagoudas, D.C.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, J.; Dai, L.; Baur, J. Effect of carbon nanotubes on the interfacial shear strength of T650 carbon fiber in an epoxy matrix. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 898–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, P.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Zhao, N.; Feng, W. Increasing the interfacial strength in carbon fiber/epoxy composites by controlling the orientation and length of carbon nanotubes grown on the fibers. Carbon 2011, 49, 4665–4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karapappas, P.; Tsantzalis, S.; Fiamegou, E.; Vavouliotis, A.; Dassios, K.; Kostopoulos, V. Multi-wall carbon nanotubes chemically grafted and physical adsorpted on reinforcing carbon fibres. Adv. Compos. Lett. 2008, 17, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riccardis, M.F.; Carbone, D.; Makris, T.D.; Giorgi, R.; Lisi, N.; Salernitano, E. Anchorage of carbon nanotubes grown on carbon fibres. Carbon 2006, 44, 671–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, A.S.; Parasuram, S.; Bose, S.; Sumangala, T.P.; Sreekanth, M.S. Tailoring the interfacial performance of epoxy nanocomposites reinforced with modified carbon fibre grafted MWCNTs—MoS2 hybrid. Results Eng. 2025, 27, 106500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Li, A.; Wu, J.; Yang, D. 3D printing of continuous carbon fibre reinforced high-temperature epoxy composites. Compos. Comm. 2025, 56, 102397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drzal, L.T.; Raghavendran, V.K. Adhesion of thermoplastic matrices to carbon fibers: Effect of polymer molecular weight and fiber surface chemistry. J Thermoplast. Compos. Mater. 2003, 16, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.B.; Zhang, S.; Hao, L.F.; Jiao, W.C.; Yang, F.; Li, X.F.; Wang, R.G. Properties of carbon fiber sized with poly(phthalazinoneether ketone) resin. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2013, 128, 3702–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozkan, C.; Gamze Karsli, N.; Aytac, A.; Deniz, V. Short carbon fiber reinforced polycarbonate composites: Effects of different sizing materials. Compos. B Eng. 2014, 62, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, T.; Yabushita, S. Enhancement of surface adhesion between carbon fiber and thermoplastic using polymer colloid dispersed in n-butanol. Results Mater. 2022, 16, 100322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.-Y.; Cho, K.-Y.; Im, D.; Kwon, Y.-J.; Shon, M.; Baek, K.-Y.; Yoon, H.G. High mechanical properties of covalently functionalized carbon fiber and polypropylene composites by enhanced interfacial adhesion derived from rationally designed polymer compatibilizers. Compos. Part B 2022, 228, 109439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, H.; Bismarck, A.; Greenhalgh, E.S.; Shaffer, S.P. Carbon nanotube grafted carbon fibres: A study of wetting and fibre fragmentation. Compos. Part A 2010, 41, 1107–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Bijwe, J.; Panier, S. Optimization of surface treatment to enhance fiber–matrix interface and performance of composites. Wear 2012, 274–275, 326–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, T. Plasma activation of carbon fibres for polyarylacetylene composites. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2007, 201, 4965–4968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Sharma, M.; Panier, S.; Mutel, B.; Mitschang, P.; Bijwe, J. Influence of cold remote nitrogen oxygen plasma treatment on carbon fabric and its composites with specialty polymers. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 964–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Baek, S.J.; Youn, J.R. New hybrid method for simultaneous improvement of tensile and impact properties of carbon fiber reinforced composites. Carbon 2011, 49, 5329–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Faudree, M.C.; Matsumura, Y.; Jimbo, I.; Nishi, Y. Tensile strength of a Ti/thermoplastic ABS matrix CFRTP joint connected by surface activated carbon fiber cross-weave irradiated by electron beam. Mater. Trans. 2016, 57, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirai, T.; Amano, K.; Onochi, Y.; Inoue, Y. Superior hygrothermal resistance and interfacial adhesion by ternary thermoplastic polymer blend matrix for carbon fiber composite. Compos. Part A 2021, 144, 106338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AnylytIQ. Polycarbonate Price Index. Available online: https://businessanalytiq.com/procurementanalytics/index/polycarbonate-price-index/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Business AnalytIQ. Epoxy Resin Price Index. Available online: https://businessanalytiq.com/procurementanalytics/index/epoxy-resin-price-index/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Nishi, Y.; Tsuyuki, N.; Faudree, M.C.; Uchida, H.T.; Sagawa, K.; Matsumura, Y.; Salvia, M.; Kimura, H. Impact Value Improvement of Polycarbonate by Addition of Layered Carbon Fiber Reinforcement and Effect of Electron Beam Treatment. Polymers 2025, 17, 1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, B.; Haneman, D. Dangling bonds on silicon. Phys. Rev. B 1978, 17, 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Faudree, M.C.; Enomoto, Y.; Takase, S.; Kimura, H.; Tonegawa, A.; Matsumura, Y.; Jimbo, I.; Salvia, M.; Nishi, Y. Enhanced Tensile Strength of Titanium/Polycarbonate Joint Connected by Electron Beam Activated Cross-Weave Carbon Fiber Cloth Insert. Mater. Trans. 2017, 58, 1606–1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudree, M.C.; Uchida, H.T.; Kimura, H.; Kaneko, S.; Salvia, M.; Nishi, Y. Advances in Titanium/Polymer Hybrid Joints by Carbon Fiber Plug Insert: Current Status and Review. Materials 2022, 15, 3220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Uchida, H.T.; Kaneko, S.; Faudree, M.C. Fracture toughness of CF-Plug joints of Ti and epoxy matrix CFRP. Key Eng. Mater. 2019, 821, 131–134. [Google Scholar]

- Oguri, K.; Iwataka, N.; Tonegawa, A.; Hirose, Y.; Takayama, K.; Nishi, Y. Misting-free diamond surface created by sheet electron beam irradiation. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 16, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oguri, K.; Irisawa, Y.; Tonegawa, A.; Nishi, Y. Influences of electron beam irradiation on misting and related surface condition on sapphire lens. J. Intell. Mater. Struct. 2006, 17, 761–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Kobayashi, H.; Salvia, M. Effects of electron beam irradiation on Charpy impact value of GFRP. Mater. Trans. 2007, 48, 1924–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faudree, M.C.; Nishi, Y.; Gruskiewicz, M. Effects of Electron Beam Irradiation on Charpy Impact Value of Short Glass Fiber (GFRP) Samples with Random Distribution of Solidification Texture Angles from Zero to 90 Degrees. Mater. Trans. 2012, 53, 1412–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanda, M.; Miyazawa, Y.; Uyama, M.; Nishi, Y. Creation of Adhesive Force between Laminated Sheets of Aluminum and Polyurethane by Homogeneous Low Energy Electron Beam Irradiation Prior to Hot-Press. Mater. Trans. 2013, 54, 1795–1799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyama, M.; Fujiyama, N.; Okada, T.; Kanda, M.; Nishi, Y. High Adhesive Force between Laminated Sheets of Copper and Polyurethane Improved by Homogeneous Low Energy Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) Prior to Hot-Press. Mater. Trans. 2014, 55, 561–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minegishi, A.; Okada, T.; Kanda, M.; Faudree, M.C.; Nishi, Y. Tensile Shear Strength Improvement of 18-8 Stainless Steel/CFRP Joint Irradiated by Electron Beam Prior to Lamination Assembly and Hot-Pressing. Mater. Trans. 2015, 56, 1169–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Mizutani, A.; Kimura, A.; Toriyama, T.; Oguri, K.; Tonegawa, A. Effects of sheet electron beam irradiation on aircraft design stress of carbon fiber. J. Mater. Sci. 2003, 38, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Toriyama, T.; Oguri, K.; Tonegawa, A.; Takayama, K. High fracture resistance of carbon fiber treated by electron beam irradiation. J. Mater. Rsch. 2001, 16, 1632–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Faudree, M.C.; Quan, J.; Yamazaki, Y.; Takahashi, A.; Ogawa, S.; Iwata, K.; Tonegawa, A.; Salvia, M. Increasing Charpy Impact Value of Polycarbonate (PC) Sheets Irradiated by Electron Beam. Mater. Trans. 2018, 59, 1304–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishi, Y.; Tsuyuki, N.; Uchida, H.T.; Faudree, M.C.; Sagawa, K.; Kanda, M.; Matsumura, Y.; Salvia, M.; Kimura, H. Increasing Bending Strength of Polycarbonate Reinforced by Carbon Fiber Irradiated by Electron Beam. Polymers 2023, 15, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, F.; Sagawa, K.; Uchida, H.T.; Faudree, M.C.; Kimura, H.; Nishi, Y. Effect of EB-Irradiation of Finishing Process on Charpy Impact value of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastic Polycarbonate (CFRTP-PC). In Proceedings of the 8th ICAMSME 2024, International Conference on Advanced Materials, Structures, and Mechanical Engineering, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 15–17 March 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Technical Sheet for CF. Available online: https://shop.lab-cast.com/?pid=93479046 (accessed on 14 October 2025).

- Christenhusz, R.; Reimer, L. Schichtdickenabhangigkeit der warmerzeugungdurch elektronenbestrahlung im energiebereichzwischen 9 und 100 kV (Layer thickness dependency of heat generation by electron irradiation in the energy range between9 and 100 kV). Z. Angew. Phys. 1967, 23, 396–404. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, S.-L.; Kim, J.-K. Cooling rate influences in carbon fibre/PEEK composites. Part III: Impact damage performance. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2001, 32, 775–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, V.; Baltopoulos, A.; Karapappas, P.; Vavouliotis, A.; Paipetis, A. Impact and after-impact properties of carbon fibre reinforced composites enhanced with multi-wall carbon nanotubes. Compos. Sci. Tech. 2010, 70, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imielińska, K.; Guillaumat, L.; Wojtyra, R.; Castaings, M. Effects of manufacturing and face/core bonding on impact damage in glass/polyester–PVC foam core sandwich panels. Compos. Part B 2008, 39, 1034–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidya, A.S.; Vaidya, U.K.; Uddin, N. Impact response of three-dimensional multifunctional sandwich composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2008, 472, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David-West, O.S.; Nash, D.H.; Banks, W.W. An experimental study of damage accumulation in balanced CFRP laminates due to repeated impact. Compos. Struct. 2008, 83, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aktay, L.; Johnson, A.F.; Holzapfel, M. Prediction of impact damage on sandwich composite panels. Computat. Mater. Sci. 2005, 32, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komai, K.; Minoshima, K.; Tanaka, K.; Nakaike, K. Influence of Electron Radiation and Water Absorption on Impact and CAI Fracture Behavior of Carbon/Epoxy Composite. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Composite Materials, Paris, France, 5–9 July 1999; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Aktaş, M.; Karakuzu, R.; Arman, Y. Compression-after impact behavior of laminated composite plates subjected to low velocity impact in high temperatures. Compos. Struct. 2009, 89, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japanese Industrial Standard JIS K 7077; Testing Method for Charpy Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Plastics. Japanese Standards Association: Tokyo, Japan, 1991.

- Splett, J.; Iyer, H.; Wang, C. McCowan: National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Recommended Practice Guide, Computing Uncertainty for Charpy Impact Test Machine Test Results; Special Publication 960-18; US Department of Commerce: Boulder, CO, USA, 2008; pp. 27–29.

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, J.; Qiang, S.; Lu, H.; Li, J. Effect of carbon fibers and graphite particles on mechanical properties and electrical conductivity of cement composite. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 94, 110036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shackelford, J.F. Introduction to Materials Science for Engineers, 5th ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; p. 549. [Google Scholar]

- James, A.; Lord, M. Macmillan’s Chemical and Physical Data, London and Basingstoke; The Macmillan Press, Ltd.: London, UK, 1992; pp. 398–399, 484–485. [Google Scholar]

- Beamson, G.; Briggs, D. High Resolution XPS of Organic Polymers—The Scienta ESCA300 Database; Wiley Interscience: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1992; Appendices 1, 2, 3.1 and 3.2. [Google Scholar]

- Grey, L.H.; Nie, H.-Y.; Biesinger, M.C. Defining the nature of adventitious carbon and improving its merit as a charge correction reference for XPS. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2024, 653, 159319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Liu, X.; Chen, X.; Soutis, C. π—π interaction between carbon fibre and epoxy resin for interface improvement in composites. Compos. B 2021, 220, 108983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, J.D.; Payne, B.P.; McIntyre, N.S.; Biesinger, M.C. Enhancing Oxygen Spectra Interpretation by Calculating Oxygen Linked to Adventitious Carbon. Surf. Interface Anal. 2025, 57, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujimoto, A.; Yamada, Y.; Koinuma, M.; Sato, S. Origins of sp(3)C peaks in C1s X-ray Photoelectron Spectra of Carbon Materials. Anal. Chem. 2016, 88, 6110–6114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | Epoxy CFRTS | CFRPC | HLEBI-Treated CFRPC |

|---|---|---|---|

| UTS (σb: MPa) | 413 | 95.0 | 290 |

| Strain at σb (εb) | 0.032 | 0.015 | 0.018 |

| Material | Vc (kV) | D (kGy) | Location | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [PC]4[CF]3 | 170 | 216 | all CF plies | impact as at Pf = 0 inc. 6% |

| [PC]4[CF]3 | 170 | 216 | all CF plies | bending σb at Pa = 0.50 inc. 25% |

| [PC]10[CF]9 | 250 | 86 to 172 | finished surfaces | impact auc at Pa = 0.50 inc. up to 25 to 30% |

| [PC]10[CF]9 (this study) | 150, 175, 200, 225 | 43.2 | finished surfaces | impact auc at Pa = 0.50 inc. up to 47% (200 kV) |

| Vc (kV) | 0 (Untreated) | 150 | 175 | 200 | 225 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Specimens | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Cathode Potential (Vc: kV) | Dropped Potential | Surface Electrical Potential at PC1 (Vx(PC1): kV) (x = 150, 175, 200, or 225) | Calculated Penetration Depth into PC1 Ply (Dth: μm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Ti-Window (ΔVTi: kV) | In N2 Gas Atmosphere (ΔVN2: kV) | |||

| 150 | 24.1 | 16.9 | 109.0 | 138 |

| 175 | 21.8 | 14.8 | 138.5 | 206 |

| 200 | 19.9 | 13.3 | 166.8 | 281 |

| 225 | 18.4 | 12.1 | 194.5 | 363 |

| Thickness | Density | Voltage at Top Surface of Layer (VX: kV)/ Penetration Depth from Top Surfaces (Dth: μm) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | T (μm) | ρ (kg/m3) | Vc = 150 kV | 175 kV | 200 kV | 225 kV | ||||

| (layer) | V150 | Dth | V175 | Dth | V200 | Dth | V225 | Dth | ||

| Ti window | 10 | 4540 | 150 | 62 | 175 | 80 | 200 | 100 | 225 | 122 |

| N2 | 25,000 | 1.13 | 125 | 186,651 | 153 | 259,032 | 180 | 339,021 | 207 | 426,186 |

| PC1 | 75 | 1200 | 109 | 138 | 138 | 206 | 167 | 281 | 194 | 363 |

| CF1 | 139 | 1800 | 50 | 25 | 88 | 65 | 122 | 111 | 154 | 164 |

| PC2 | 75 | 1200 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 11 |

| CF2 | 139 | 1800 | 0 | 0 | 0- | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sato, F.; Sagawa, K.; Uchida, H.T.; Irie, H.; Faudree, M.C.; Salvia, M.; Tonegawa, A.; Kaneko, S.; Kimura, H.; Nishi, Y. Increasing Cathode Potential of Homogeneous Low Voltage Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) to Increase Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polycarbonate and Characterization by XPS C1s and O1s Peaks. Materials 2025, 18, 5471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235471

Sato F, Sagawa K, Uchida HT, Irie H, Faudree MC, Salvia M, Tonegawa A, Kaneko S, Kimura H, Nishi Y. Increasing Cathode Potential of Homogeneous Low Voltage Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) to Increase Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polycarbonate and Characterization by XPS C1s and O1s Peaks. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235471

Chicago/Turabian StyleSato, Fumiya, Kouhei Sagawa, Helmut Takahiro Uchida, Hirotaka Irie, Michael C. Faudree, Michelle Salvia, Akira Tonegawa, Satoshi Kaneko, Hideki Kimura, and Yoshitake Nishi. 2025. "Increasing Cathode Potential of Homogeneous Low Voltage Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) to Increase Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polycarbonate and Characterization by XPS C1s and O1s Peaks" Materials 18, no. 23: 5471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235471

APA StyleSato, F., Sagawa, K., Uchida, H. T., Irie, H., Faudree, M. C., Salvia, M., Tonegawa, A., Kaneko, S., Kimura, H., & Nishi, Y. (2025). Increasing Cathode Potential of Homogeneous Low Voltage Electron Beam Irradiation (HLEBI) to Increase Impact Strength of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polycarbonate and Characterization by XPS C1s and O1s Peaks. Materials, 18(23), 5471. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235471