Machine Learning-Based Multi-Objective Composition Optimization of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels

Abstract

1. Introduction

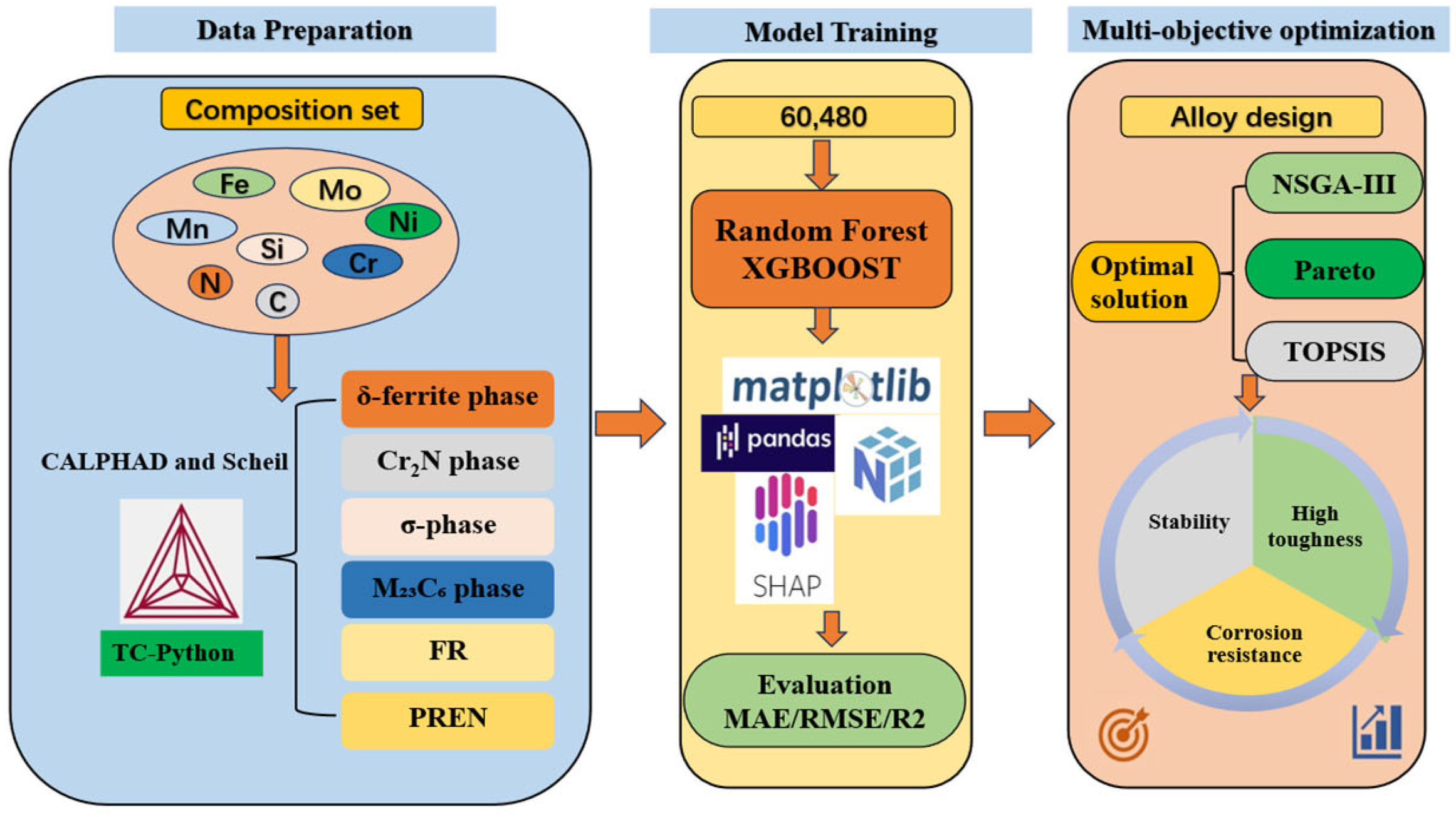

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. HTC Calculation

2.2. Machine Learning Model

2.3. Model Performance Metrics

3. Results and Discussion

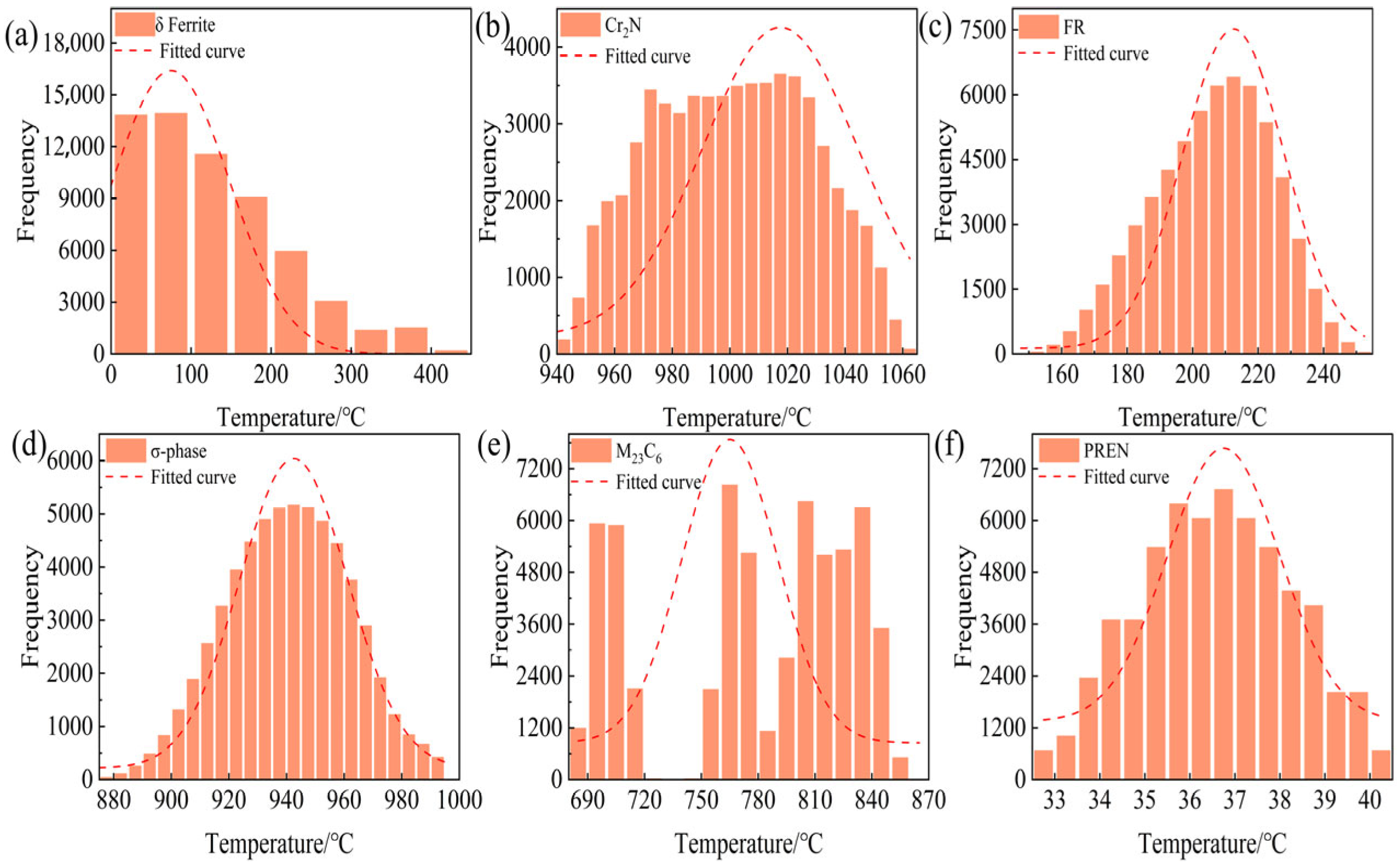

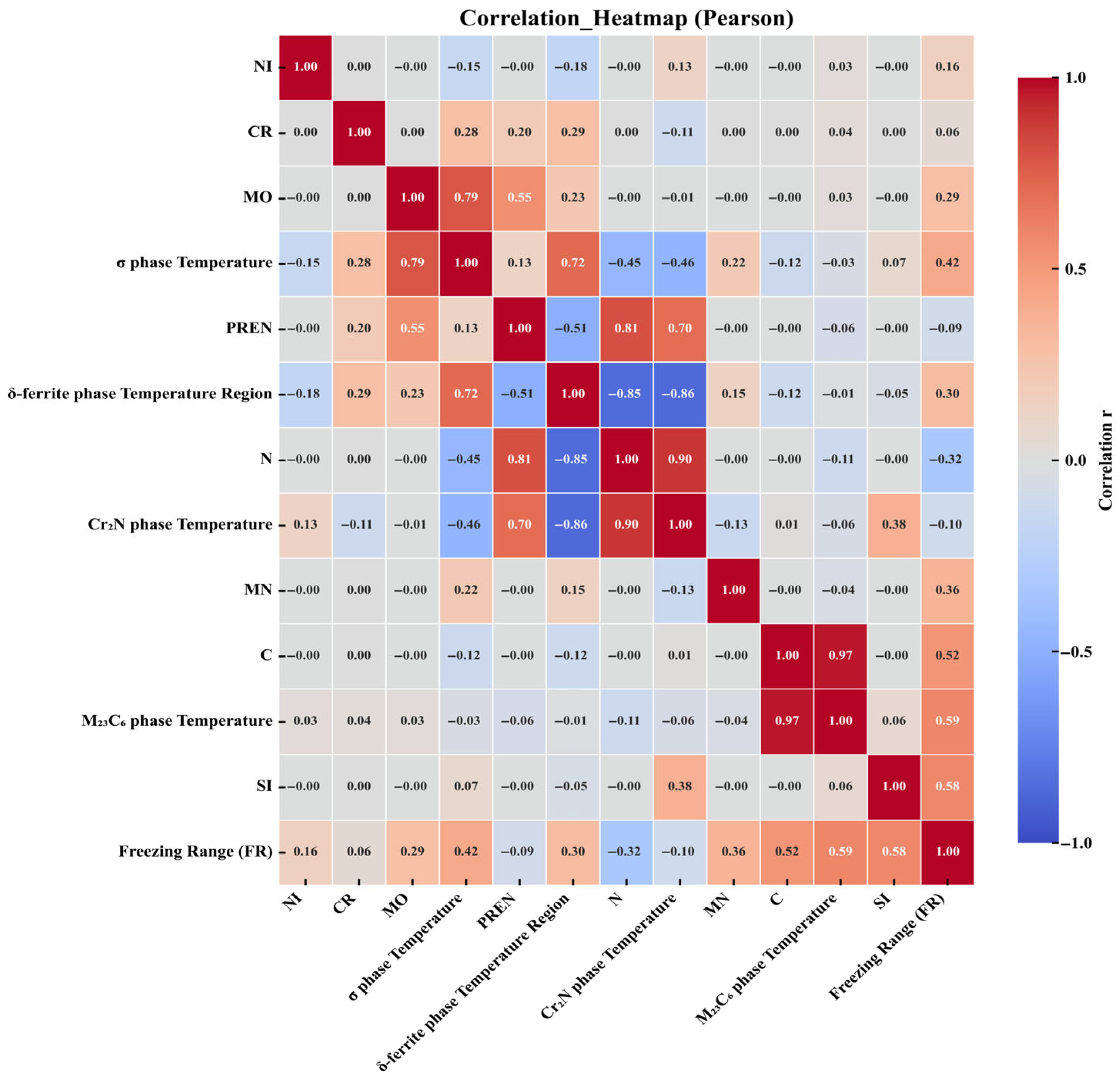

3.1. Correlation Analysis

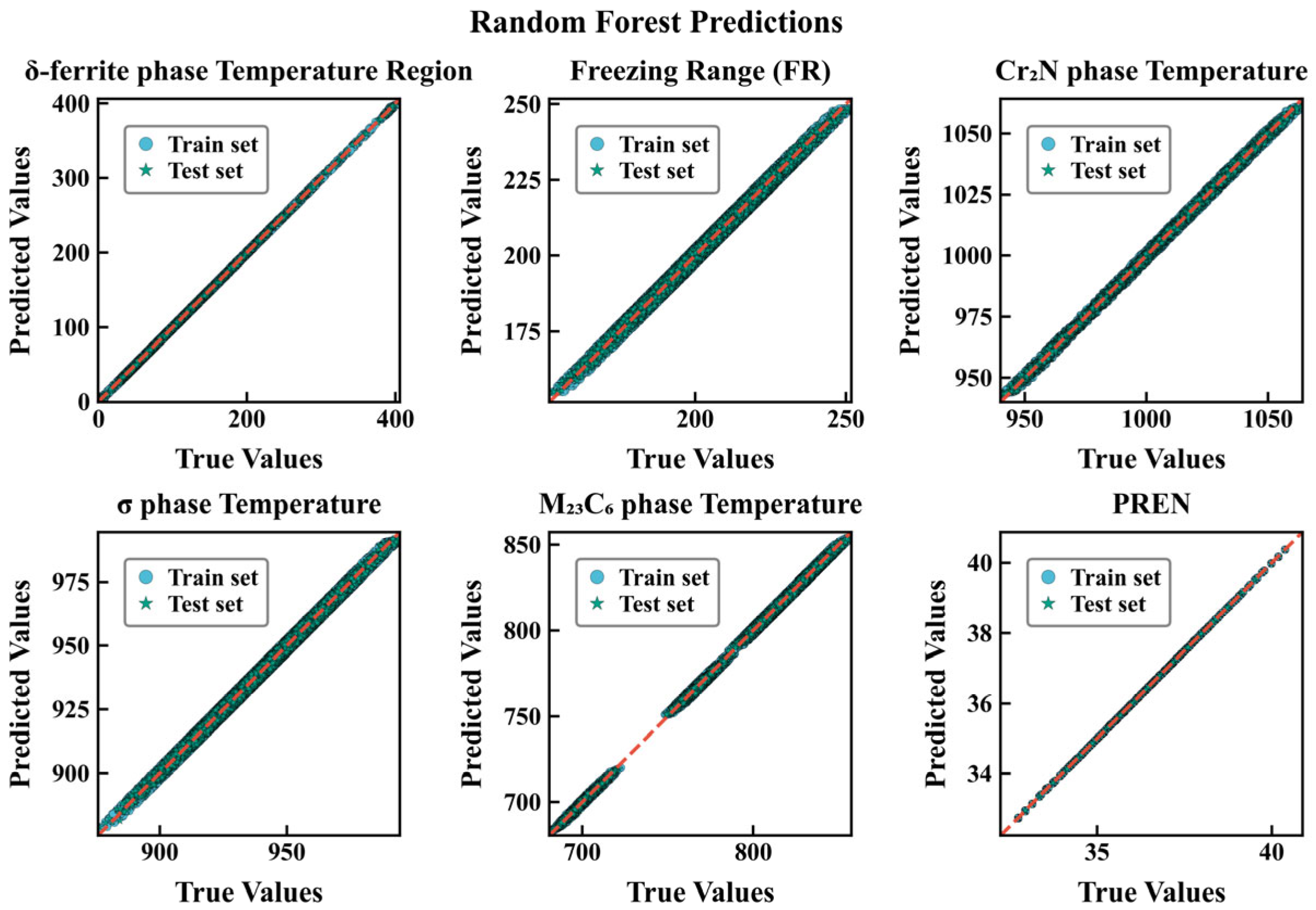

3.2. Evaluation of Different Models

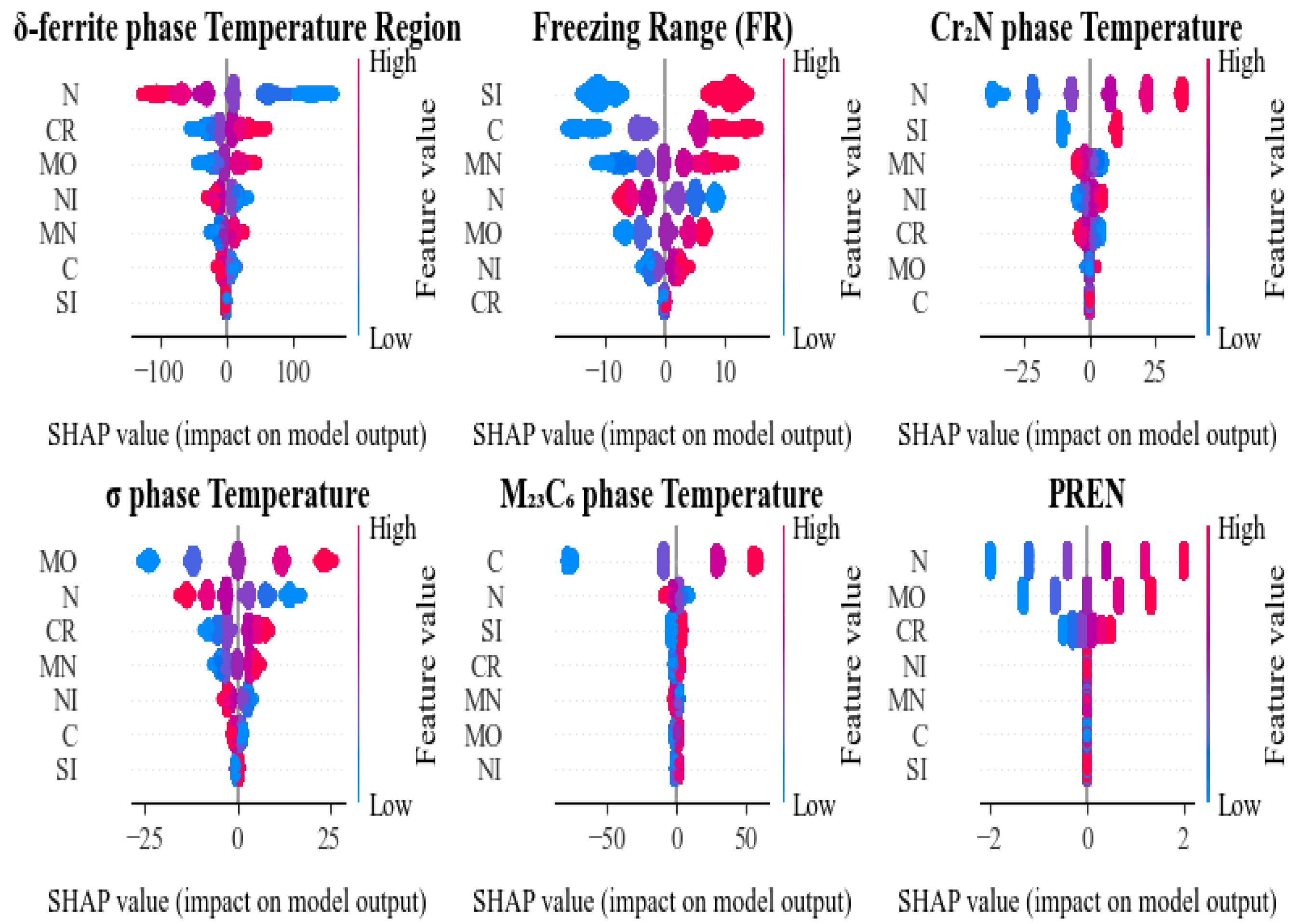

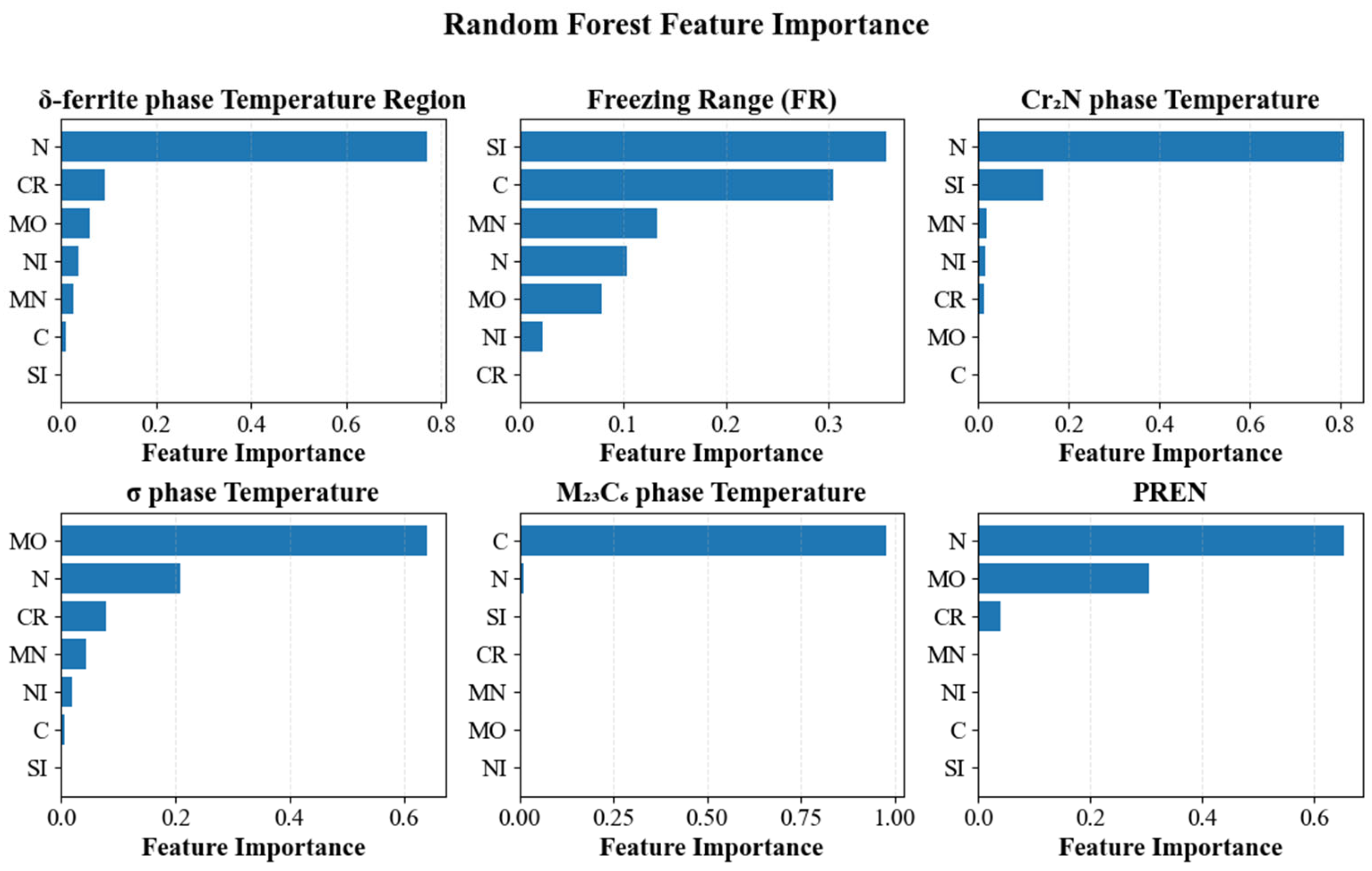

3.3. SHAP Analysis

3.4. Decision Variables and Value Ranges

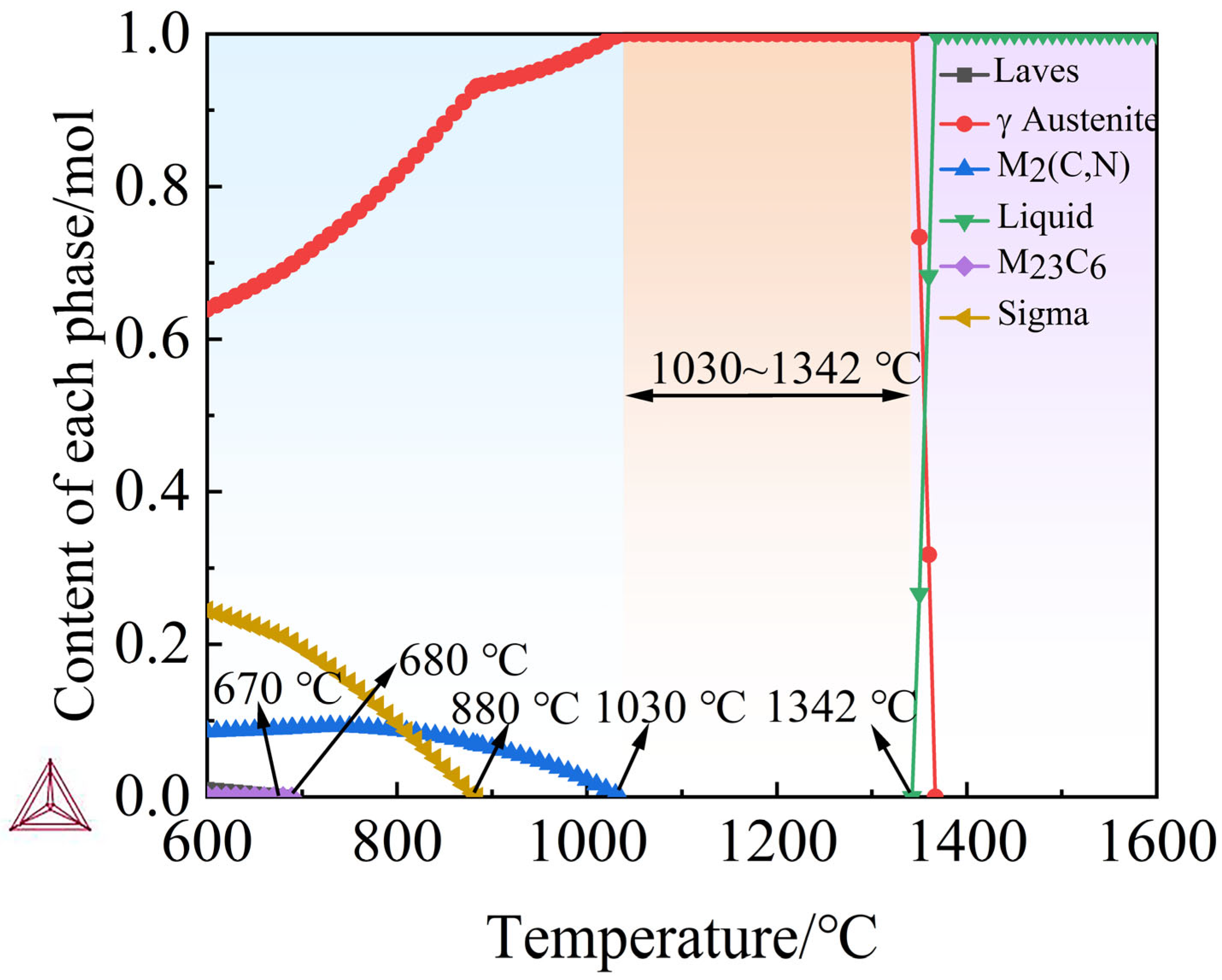

3.4.1. Model Validation

3.4.2. Optimize Objective Function

3.4.3. Optimization Algorithms and Parameter Settings

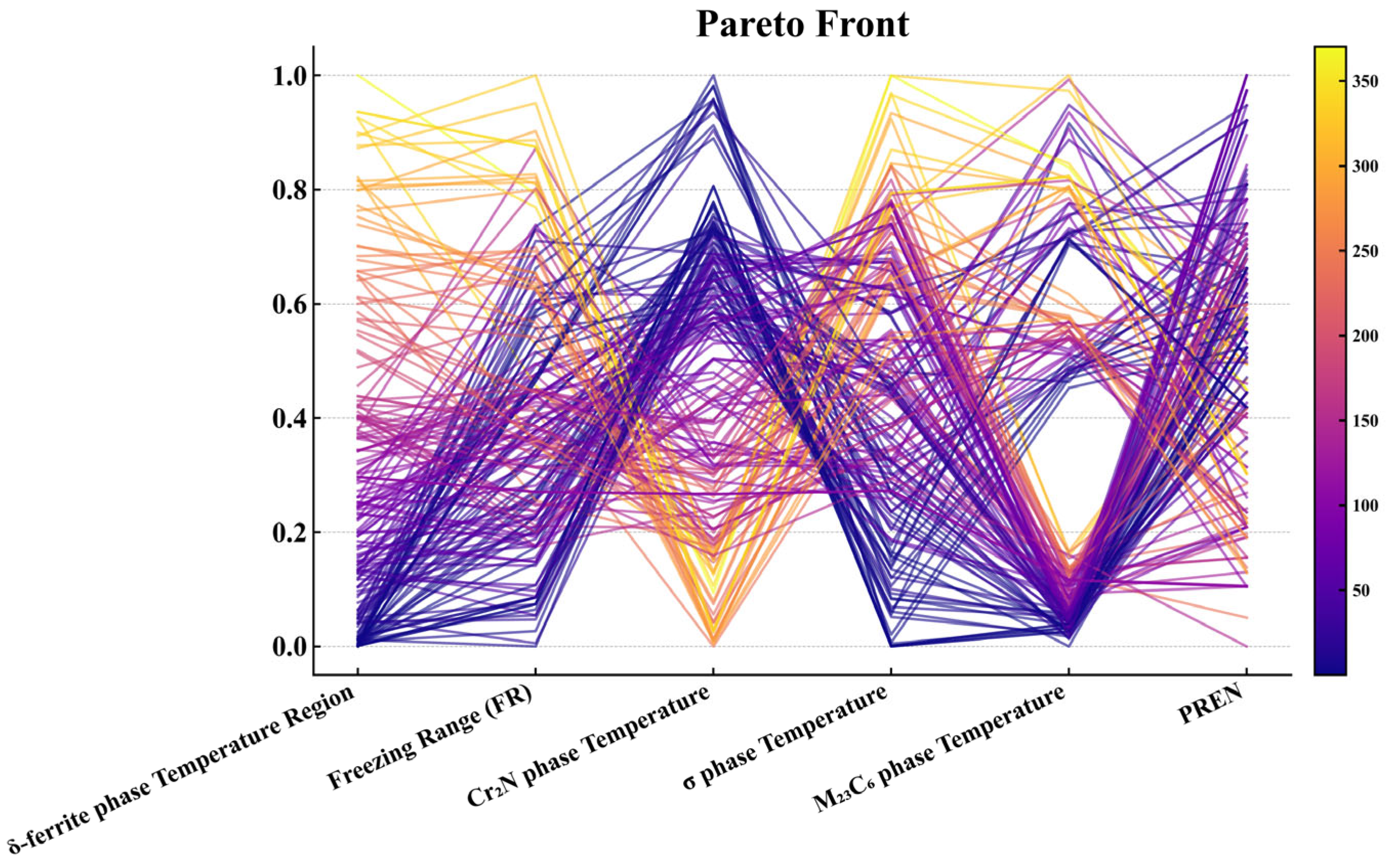

3.5. Results Screening and Evaluation

3.6. Optimization Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, T.H.; Wang, J.; Bai, J.G.; Wang, S.J.; Chen, C.; Han, P.D. Effect of boron on dissolution and repairing behavior of passive film on S31254 super-austenitic stainless steel immersed in H2SO4 solution. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2022, 29, 1012–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pujar, M.G.; Kamachi Mudali, U.; Singh, S.S. Electrochemical Noise Studies of the Effect of Nitrogen on Pitting Corrosion Resistance of High Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 4178–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsson, C.-O.A.; Landolt, D. Passive Films on Stainless Steels—Chemistry, Structure and Growth. Electrochim. Acta 2003, 48, 1093–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gao, Z.; Wu, G.; Mao, X. Titanium microalloying of steel: A review of its effects on processing, microstructure and mechanical properties. J. Univ. Sci. Technol. Beijing 2022, 29, 645–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, Y.X.; Zheng, Z.B.; Yang, H.K.; Long, J.; Han, P.X. Recent progress in microstructural evolution, mechanical and corrosion properties of medium-Mn steel. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2023, 30, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talha, M.; Behera, C.K.; Sinha, O.P. In-Vitro Long Term and Electrochemical Corrosion Resistance of Cold Deformed Nitrogen Containing Austenitic Stainless Steels in Simulated Body Fluid. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2014, 40, 455–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonguzhali, A.; Pujar, M.G.; Kamachi Mudali, U. Effect of Nitrogen and Sensitization on the Microstructure and Pitting Corrosion Behavior of AISI Type 316LN Stainless Steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2013, 22, 1170–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yang, Y. Intergranular Corrosion Behavior of High Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steel. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2009, 16, 654–660. [Google Scholar]

- Erneman, J.; Schwind, M.; Liu, P.; Nilsson, J.-O.; Andrén, H.-O.; Ågren, J. Precipitation Reactions Caused by Nitrogen Uptake during Service at High Temperatures of a Niobium Stabilised Austenitic Stainless Steel. Acta Mater. 2004, 52, 4337–4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, Y.P.; Qu, H.P.; Chen, H.T.; Weng, Y.Q. Research progress and development tendency of nitrogen-alloyed austenitic stainless steels. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2015, 22, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Cabezon, C.; Blanco, Y.; Rodriguez-Mendez, M.L.; Martin-Pedrosa, F. Characterization of porous nickel-free austenitic stainless steel prepared by mechanical alloying. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 716, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ningshen, S.; Mudali, U.K.; Mittal, V.K.; Khatak, H.S. Semiconducting and passive film properties of nitrogen-containing type 316LN stainless steels. Corros. Sci. 2007, 49, 481–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Ngai, T.; Peng, H.; Li, L.; Zhou, F.; Peng, Z. Microstructure and Properties of Porous High-N Ni-Free Austenitic Stainless Steel Fabricated by Powder Metallurgical Route. Materials. 2018, 11, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ha, H.Y.; Lee, T.H.; Oh, C.S.; Kim, S.J. Effects of combined addition of carbon and nitrogen on pitting corrosion behavior of Fe–18Cr–10Mn alloys. Scr. Mater. 2009, 61, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, J.; Lee, T.H.; Shin, J.H.; Lee, J.W. Hot working behavior of a nitrogen-alloyed Fe–18Mn–18Cr–N austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2014, 594, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermanpur, A.; Behjati, P.; Han, J.; Najafizadeh, A.; Lee, Y.K. A microstructural investigation on deformation mechanisms of Fe–18Cr–12Mn–0.05 C metastable austenitic steels containing different amounts of nitrogen. Mater. Des. 2015, 82, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozuelo, M.; Wittig, J.E.; Jiménez, J.A.; Frommeyer, G. Enhanced mechanical properties of a novel high-nitrogen Cr-Mn-Ni-Si austenitic stainless steel via TWIP/TRIP effects. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 2009, 40, 1826–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masumura, T.; Seto, Y.; Tsuchiyama, T.; Kimura, K. Work-hardening mechanism in high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Trans. 2020, 61, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, K. High-cycle fatigue behavior of high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2009, 517, 257–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, J.B. Fatigue properties of high nitrogen steels. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 117, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Park, S.-J.; Kang, J.-Y.; Lee, C.-H.; Ha, H.-Y.; Moon, J.; Jang, J.H.; Lee, T.-H. Fatigue Behaviors of High Nitrogen Stainless Steels with Different Deformation Modes. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2017, 682, 622–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, X.; Zhao, T.; Sun, X.; Niu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhao, J.; Wang, T. Adding N to Enhance Low-Cycle Fatigue Properties of High-Mn Austenitic Steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 897, 146357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeng, W.-Y.; Kim, M.-H. Comparative Study on the Fatigue Crack Growth Behavior of 316L and 316LN Stainless Steels: Effect of Microstructure of Cyclic Plastic Strain Zone at Crack Tip. J. Nucl. Mater. 2000, 282, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, L.; Ngai, T.; Hu, L. Influence of Hydrogen Reduction on the Properties of Porous High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steel. Materials. 2022, 15, 5585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Fu, Y.; Huang, J.; Han, E.; Ke, W.; Yang, K.; Jiang, Z. Investigation on Pitting Corrosion of Nickel-Free and Manganese-Alloyed High-Nitrogen Stainless Steels. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2009, 18, 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olefjord, I.; Wegrelius, L. The Influence of Nitrogen on the Passivation of Stainless Steels. Corros. Sci. 1996, 38, 1203–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ren, Y. Nickel-free austenitic stainless steels for medical applications. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2010, 11, 014105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yao, Z.; Guan, Y.; Yang, H.; Shahzad, M.B.; Wu, Y.; Yang, K. High nitrogen stainless steel drug-eluting stent-assessment of pharmacokinetics and preclinical safety in vivo. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 5, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metikoš-Huković, M.; Babić, R.; Grubač, Z.; Petrović, Ž.; Lajçi, N. High Corrosion Resistance of Austenitic Stain-less Steel Alloyed with Nitrogen in an Acid Solution. Corros. Sci. 2011, 53, 2176–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, Z.; Zhang, L. Effect of nitrogen content on corrosion behavior of high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steel. npj Mater. Degrad. 2023, 7, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.B.; Zhao, S.P.; Cai, Y.; Li, J.; Liang, X.; Lu, L.; Luo, S.N. Superior Dynamic Mechanical Properties of High Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steel. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 307, 110897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.I. A unified approach to interpreting model predictions. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.07874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponce-Bobadilla, A.V.; Schmitt, V.; Maier, C.S.; Mensing, S.; Stodtmann, S. Practical guide to SHAP analysis: Explaining supervised machine learning model predictions in drug development. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2024, 17, e70056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oviedo, F.; Ferres, J.L.; Buonassisi, T.; Butler, K.T. Interpretable and Explainable Machine Learning for Materials Science and Chemistry. Acc. Mater. Res 2022, 3, 597–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, X.; Gallagher, B.; Liu, S.; Kailkhura, B.; Hiszpanski, A.; Han, T.Y.J. Explainable machine learning in materials science. npj Comput. Mater. 2022, 8, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonini, A.S.; Tanzola, J.; Asiain, L.; Ferracutti, G.R.; Castro, S.M.; Bjerg, E.A.; Ganuza, M.L. Machine Learning model interpretability using SHAP values: Application to Igneous Rock Classification task. Appl. Comput. Geosci. 2024, 23, 100178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A. Machine learning in materials research: Developments over the last decade and challenges for the future. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 2024, 33, 101189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ni, J. Machine Learning Advances in High-Entropy Alloys: A Mini-Review. Entropy 2024, 26, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huin, D.; Leblond, J.-B.; Darghoum, I.; Bergheau, J.-M.; Bertrand, F. Extended Wagner-Type Models and Their Application to the Prediction of the Transition from Internal to External Oxidation. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2022, 209, 111334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassemali, E.; Conway, P.L.J. High-throughput CALPHAD: A powerful tool towards accelerated metallurgy. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 889771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Bocklund, B.; Diffenderfer, J.; Chaganti, S.; Kailkhura, B.; McCall, S.K.; McKeown, J.T. A comparative study of predicting high entropy alloy phase fractions with traditional machine learning and deep neural networks. npj Comput. Mater. 2024, 10, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C. The Synergy of Machine Learning and CALPHAD: Revitalizing Traditional Approaches. Comput. Mater. Sci 2025, 258, 113970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Tan, X.; Hu, S.; Gao, M.C. CALPHAD-based Bayesian optimization to accelerate alloy discovery for high-temperature applications. J. Mater. Res. 2025, 40, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Ma, S.; Gao, J.; Zhong, J.; Gao, T.; Yang, S.; Li, Q. A novel atomic mobility model for alloys under pressure and its application in high pressure heat treatment Al-Si alloys by integrating CALPHAD and machine learning. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2025, 217, 116–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Neumeier, S.; Rao, Z.; Göken, M.; Pyczak, F. CALPHAD informed design of multicomponent CoNiCr-based superalloys exhibiting large lattice misfit and high yield stress. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 854, 143798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.A.; Rao, V.N.; Ghosh, A.; Karmakar, A.; Patra, S. Prediction of Mechanical Properties of Cr-Mn-N Austenitic Stainless Steel Using Machine Learning Approach. In The International Conference on Metallurgical Engineering and Centenary Celebration; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2023; pp. 119–130. [Google Scholar]

- Ghadar, S.; Momeni, A.; Tolaminejad, B.; Soltanalinezhad, M. A comparative study on the hot deformation behavior of 410 stainless and K100 tool steels. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2019, 760, 394–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zheng, H.; Cheng, L.; Wang, E.; Sheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Prahl, U. Artificial Neural Network-Based Construction of a Processing Map for P550 Steel for Non-Magnetic Drill Collars. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 1543–1559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, H.; Deb, K. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point based nondominated sorting approach, part II: Handling constraints and extending to an adaptive approach. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2013, 18, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saller, G.; Aigner, H. High nitrogen alloyed steels for nonmagnetic drill collars. standard steel grades and latest developments. Mater. Manuf. Processes. 2004, 19, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jargelius-Pettersson, R.F.A. Application of the pitting resistance equivalent concept to some highly alloyed austenitic stainless steels. Corrosion 1998, 54, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Hussain, A.; Amir, S.B.; Awan, M.G.Z.; Ahmed, S.H.; Aslam, S.M.H. XGBoost and Random Forest Algorithms: An in Depth Analysis. Pak. J. Sci. Res. 2023, 3, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prokhorenkova, L.; Gusev, G.; Vorobev, A.; Dorogush, A.V.; Gulin, A. CatBoost: Unbiased boosting with categorical features. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1706.09516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Sha, J.; Wang, D.; Yu, Y.; Yang, Q.; Niu, X. Study on a prediction of P2P network loan default based on the machine learning LightGBM and XGboost algorithms according to different high dimensional data cleaning. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 31, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Tian, W.; Cui, Z.; Liu, B. A universal microkinetic-machine learning bimetallic catalyst screening method for steam methane reforming. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 311, 123270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Zhou, W.; Cao, X.; Liu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X. Machine learning for predicting separation factors of chiral diphosphine ligands in chiral extraction of amino acid and mandelic acid enantiomers. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.Y.; Qiao, L.Z.; Yao, S.J.; Lin, D.Q. Machine learning assisted QSAR analysis to predict protein adsorption capacities on mixed-mode resins. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 340, 126762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nohara, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Soejima, H.; Nakashima, N. Explanation of machine learning models using shapley additive explanation and application for real data in hospital. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2022, 214, 106584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, X.; Cai, W.; Yang, J.; Su, H. Optimal design of the austenitic stainless-steel composition based on machine learning and genetic algorithm. Materials 2023, 16, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, K.; Jain, H. An evolutionary many-objective optimization algorithm using reference-point-based nondominated sorting approach, part I: Solving problems with box constraints. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2013, 18, 577–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Elements (wt.%) | Elemental Content | Step Length |

|---|---|---|

| N (0.55–0.80) | 0.55/0.60/0.65/0.70/0.75/0.80 | 0.05 |

| Mo (1.8–2.6) | 1.8/2.0/2.2/2.4/2.6 | 0.2 |

| Cr (18–19) | 18.0/18.2/18.4/18.6/18.8/19.0 | 0.2 |

| Ni (3.5–4.5) | 3.5/3.7/3.9/4.1/4.3/4.5 | 0.2 |

| Mn (19.5–22.5) | 19.5/20.0/20.5/21.0/21.5/22.0/22.5 | 0.5 |

| Si (0.2–0.4) | 0.2/0.4 | 0.2 |

| C (0.01–0.04) | 0.01/0.02/0.03/0.04 | 0.1 |

| Total of Alloys’ Candidates | the total number of combinations: 6 × 5 × 6 × 6 × 7 × 2 × 4 = 60,480 | 60,480 |

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| δ-ferrite phase temperature | Ferritic phase that controls the solidification mode and strongly affects toughness and hot-cracking susceptibility in high-nitrogen austenitic stainless steels. |

| Cr2N phase temperature | Chromium nitride precipitate that consumes Cr and N from austenite, thereby degrading pitting resistance and lowering toughness, especially along grain boundaries. |

| σ-phase temperature | Cr- and Mo-rich intermetallic phase that causes severe embrittlement and depletes Cr and Mo from the matrix, reducing both toughness and localized corrosion resistance. |

| M23C6 phase temperature | Grain-boundary carbide that induces sensitization through local Cr depletion and simultaneously alters grain-boundary strength and creep resistance. |

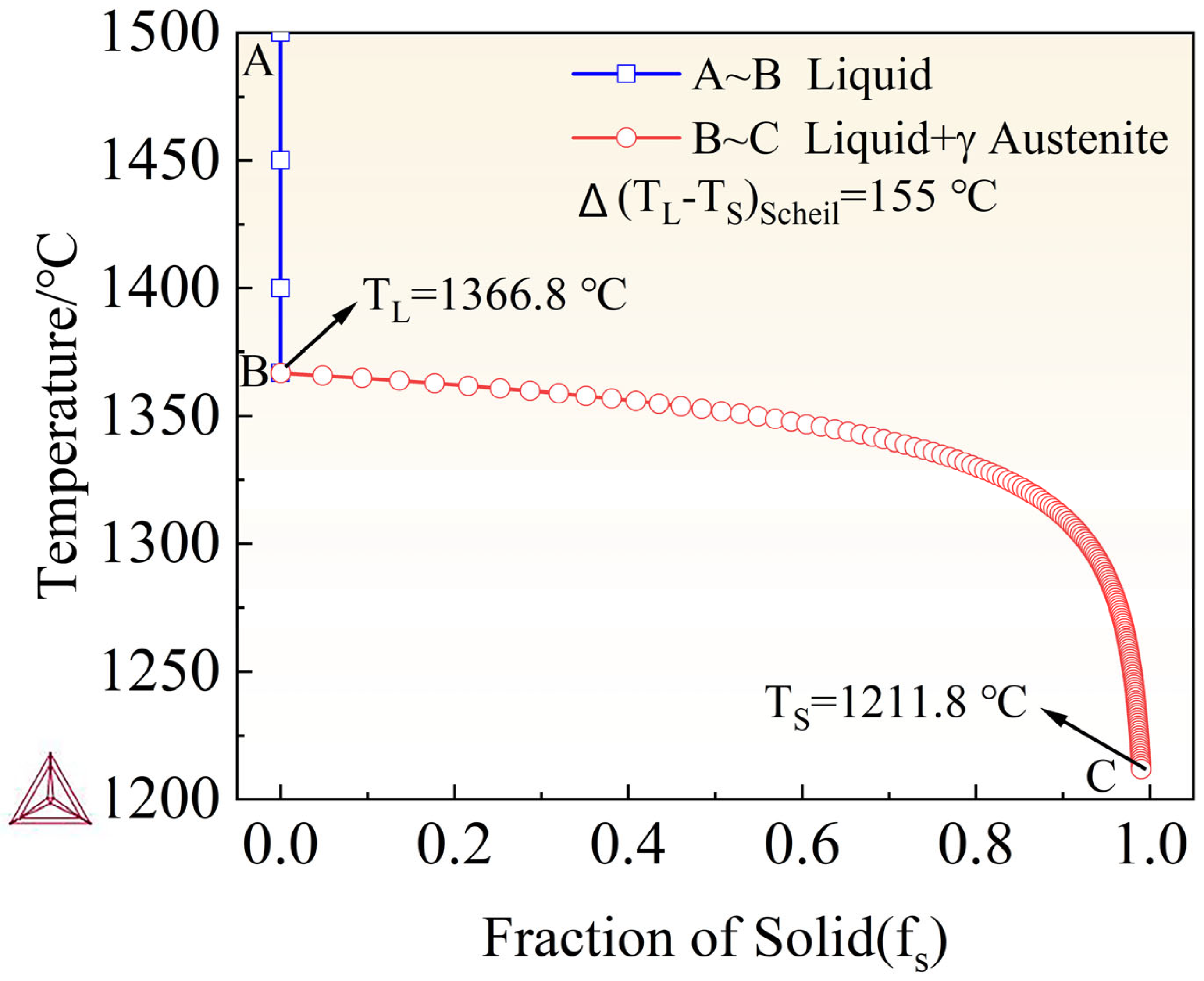

| Freezing range | Temperature interval between the liquidus and the solidus; a larger freezing range promotes microsegregation, hinders feeding and increases the risk of solidification cracking. |

| PREN | Empirical pitting resistance equivalent number that quantifies resistance to localized corrosion in chloride-containing environments, with higher values indicating better performance. |

| Type | Dataset Type | R2 | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ-ferrite phase temperature Region | Training set Test set | 0.922 0.911 | 18.387 18.701 | 26.058 27.819 |

| Freezing range | Training set Test set | 0.917 0.916 | 4.309 4.311 | 5.231 5.249 |

| Cr2N precipitation temperature | Training set Test set | 0.953 0.929 | 4.904 4.931 | 5.972 6.024 |

| σ-phase temperature | Training set Test set | 0.930 0.929 | 4.446 4.508 | 5.659 5.732 |

| M23C6 phase temperature | Training set Test set | 0.974 0.974 | 6.792 6.758 | 8.204 8.164 |

| PREN | Training set Test set | 0.966 0.965 | 0.254 0.254 | 0.313 0.309 |

| Type | Dataset Type | R2 | MAE | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δ-ferrite phase temperature Region | Training set Test set | 0.984 0.980 | 10.44 10.31 | 13.91 12.95 |

| Freezing range | Training set Test set | 0.986 0.98. | 1.37 1.27 | 1.76 1.65 |

| Cr2N precipitation temperature | Training set Test set | 0.999 0.998 | 0.98 0.979 | 1.27 1.23 |

| σ-phase temperature | Training set Test set | 0.981 0.978 | 2.11 2.11 | 2.62 2.65 |

| M23C6 phase temperature | Training set Test set | 0.974 0.974 | 1.08 1.09 | 1.43 1.41 |

| PREN | Training set Test set | 0.999 0.999 | 0.003 0.003 | 0.004 0.004 |

| Number | Name | Value |

|---|---|---|

| f1 | δ-ferrite phase temperature Region | Min |

| f2 | Cr2N phase temperature | Min |

| f3 | σ-phase temperature | Min |

| f4 | M23C6 phase temperature | Min |

| f5 | the freezing range | Min |

| f6 | PREN | Max |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Chen, L.; Cheng, L.; Wang, E.; Sheng, Z.; Zhang, L. Machine Learning-Based Multi-Objective Composition Optimization of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels. Materials 2025, 18, 5460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235460

Wang Y, Chen L, Cheng L, Wang E, Sheng Z, Zhang L. Machine Learning-Based Multi-Objective Composition Optimization of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235460

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yinghu, Long Chen, Limei Cheng, Enuo Wang, Zhendong Sheng, and Ligang Zhang. 2025. "Machine Learning-Based Multi-Objective Composition Optimization of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels" Materials 18, no. 23: 5460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235460

APA StyleWang, Y., Chen, L., Cheng, L., Wang, E., Sheng, Z., & Zhang, L. (2025). Machine Learning-Based Multi-Objective Composition Optimization of High-Nitrogen Austenitic Stainless Steels. Materials, 18(23), 5460. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235460