Tunable Superconductivity in BSCCO via GaP Quantum Dots

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis of GaP:Zn2+/GaP–GaInP–GaP:Te2−/GaP Core–Shell Quantum Dots

2.2. Preparation of B(P)SCCO Superconducting Samples

2.3. Property Characterization of B(P)SCCO Superconducting Samples

3. Results

3.1. Phase Analysis

3.2. Microstructural Analysis

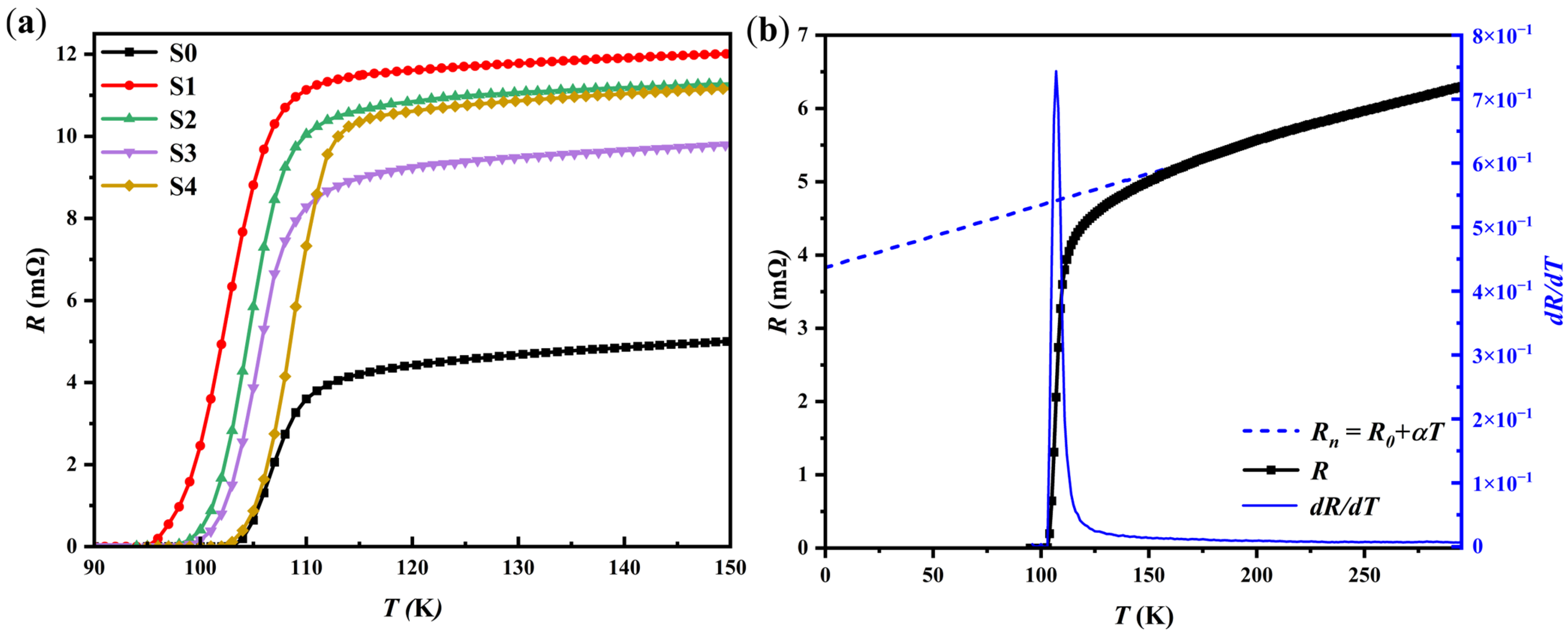

3.3. R–T Curve Measurement

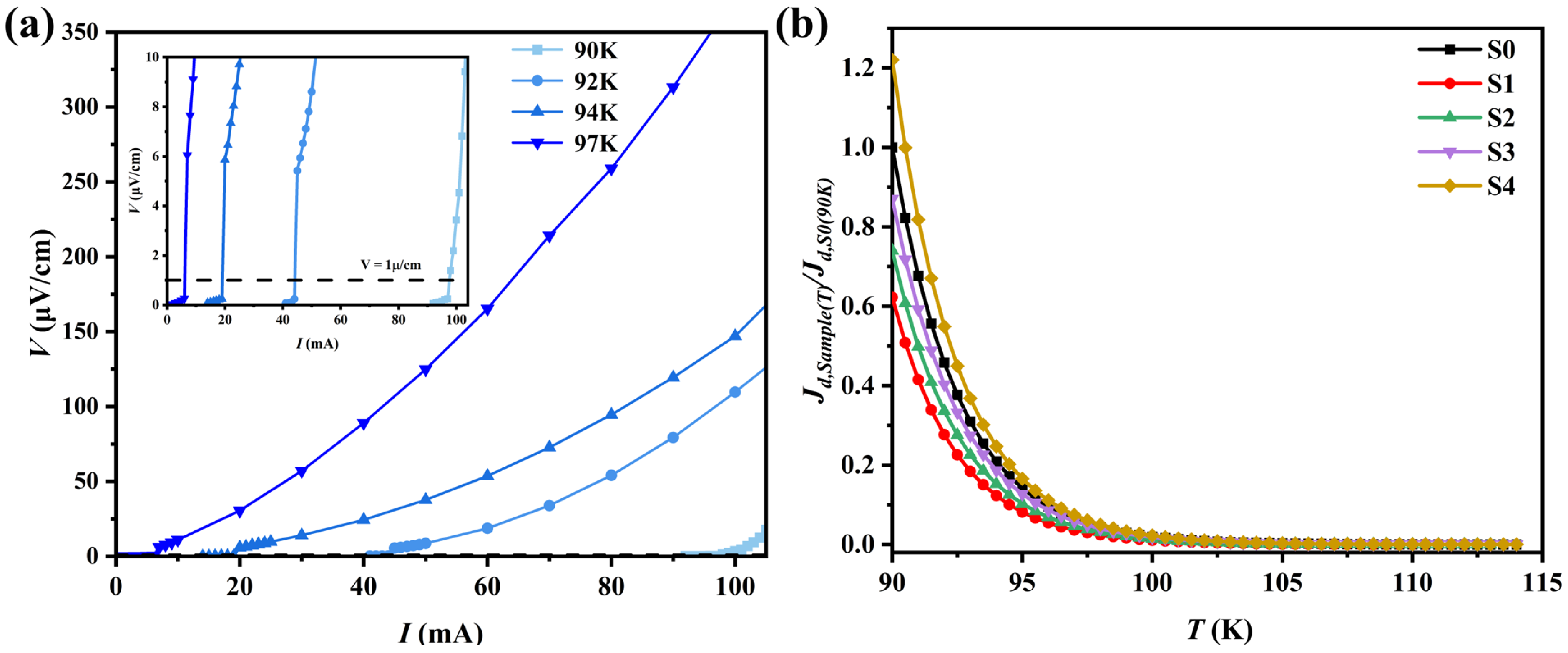

3.4. Jd–T Curve Measurement

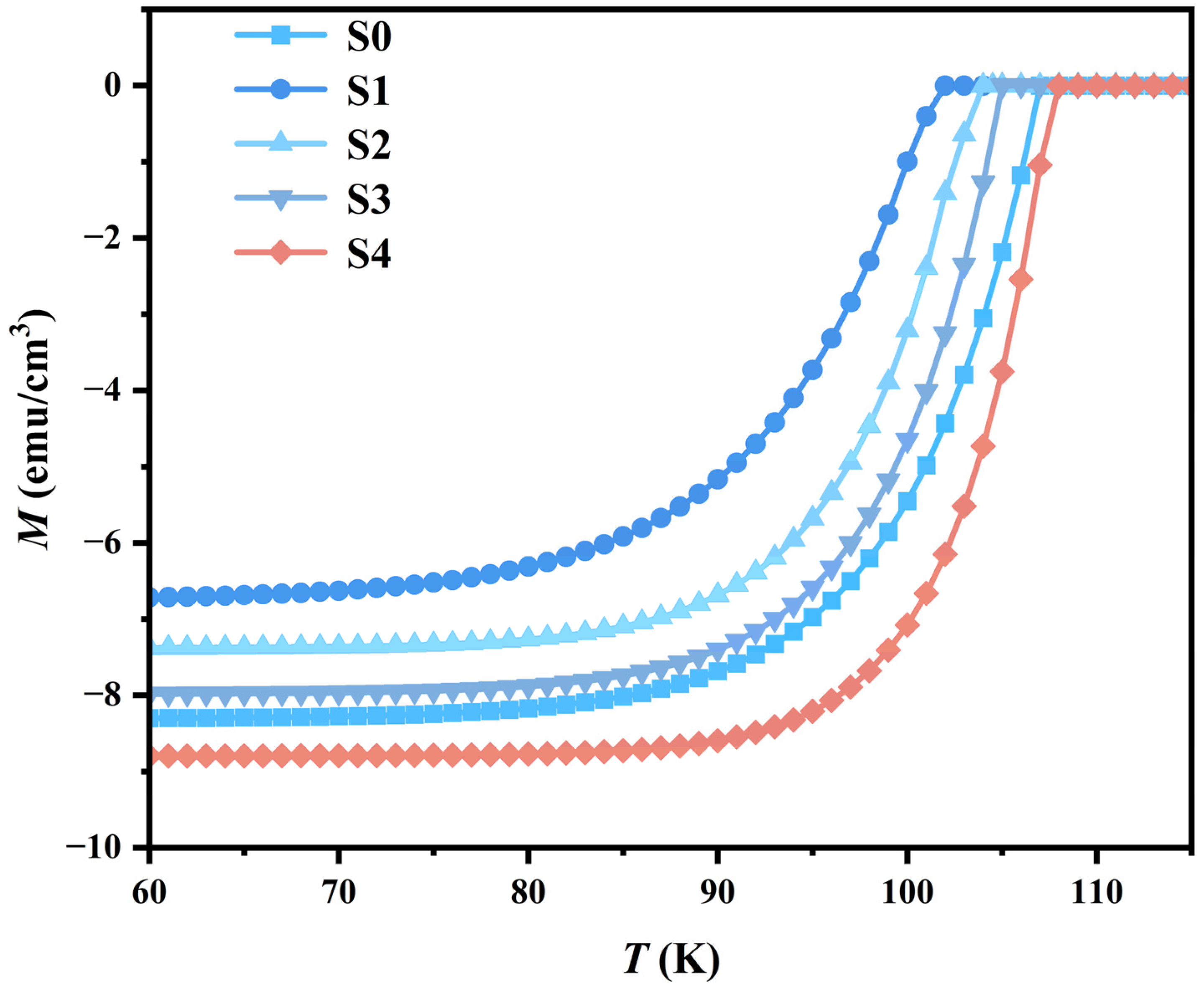

3.5. DC Magnetic Magnetization Measurement

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Maeda, H.; Tanaka, Y.; Fukutomi, M.; Asano, T. A new high-tc oxide superconductor without a rare-earth element. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1988, 27, L209–L210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarascon, J.M.; Lepage, Y.; Greene, L.H.; Bagley, B.G.; Barboux, P.; Hwang, D.M.; Hull, G.W.; McKinnon, W.R.; Giroud, M. Origin of the 110-K superconducting transition in the Bi-Sr-Ca-Cu-O system. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 38, 2504–2508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazen, R.M.; Prewitt, C.T.; Angel, R.J.; Ross, N.L.; Finger, L.W.; Hadidiacos, C.G.; Veblen, D.R.; Heaney, P.J.; Hor, P.H.; Meng, R.L.; et al. Superconductivity in the high-Tc Bi-Ca-Sr-Cu-O system—phase identification. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1988, 60, 1174–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallon, J.L.; Buckley, R.G.; Gilberd, P.W.; Presland, M.R.; Brown, I.W.M.; Bowden, M.E.; Christian, L.A.; Goguel, R. High-Tc superconducting phases in the series Bi2.1(Ca, Sr)n+1CunO2n+4+delta. Nature 1988, 333, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y.; Takano, M.; Hiroi, Z.; Oda, K.; Kitaguchi, H.; Takada, J.; Miura, Y.; Takeda, Y.; Yamamoto, O.; Mazaki, H. The High-Tc phase with a new modulation mode in theBi, Pb-Sr-Ca-Cu-O system. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 1988, 27, L2067–L2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, T.; Kato, T.; Yumura, H.; Watanabe, M.; Ashibe, Y.; Ohkura, K.; Suzawa, C.; Hirose, M.; Isojima, S.; Matsuo, K.; et al. Verification tests of a 66 kV HTSC cable system for practical use (first cooling tests). Phys. C 2002, 378, 1174–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurusu, T.; Ono, M.; Hanai, S.; Kyoto, M.; Takigami, H.; Takano, H.; Watanabe, K.; Awaji, S.; Koyama, K.; Nishijima, G.; et al. A cryocooler-cooled 19 T superconducting magnet with 52 mm room temperature bore. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2004, 14, 393–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.D.; Clem, J.R. From isotropic to anisotropic superconductors—A scaling approach—Comment. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1993, 71, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, D.; Kumar, R.; Awana, V.P.S. dc and AC susceptibility study of sol-gel synthesized Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ superconductor. Ceram. Int. 2013, 39, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazwir, M.H.; Balasan, B.A.; Zulkifli, F.H.; Abd-Shukor, R. Effect of Co0.5Ni0.5Fe2O4 Nanoparticles Addition in Ag-Sheathed Bi-2223 Superconductor Tapes Prepared by Co-Precipitation Method. Mater. Sci. Forum 2020, 981, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltyn, S.R.; Civale, L.; Macmanus-Driscoll, J.L.; Jia, Q.X.; Maiorov, B.; Wang, H.; Maley, M. Materials science challenges for high-temperature superconducting wire. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 631–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hudakova, N.; Plechacek, V.; Dordor, P.; Flachbart, K.; Knizek, K.; Kovac, J.; Reiffers, M. Influence of pb concentration on microstructural and superconducting properties of bscco superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 1995, 8, 324–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghari, R.; Naghshara, H.; Arsalan, L.; Sedghi, H. Comparing the Effects of Nb, Pb, Y, and La Replacement on the Structural, Electrical, and Magnetic Characteristics of Bi-Based Superconductors. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3889–3898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altin, S.; Aksan, M.A.; Yakinci, M.E. Normal State Electronic Properties of Whiskers Fabricated in Bi-, Ga- and Sb-doped BSCCO System Under Applied Magnetic Fields. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2011, 24, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Sánchez, M.; Sánchez-Mera, T.; Santos-Cruz, J.; Pérez-García, C.E.; Olvera, M.D.; Santillán-Rodríguez, C.R.; Matutes-Aquino, J.; Contreras-Puente, G.; de Moure-Flores, F. Effect of sintering time on structural, morphological and electrical properties of Sb-doped Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3Oy superconductor. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 16049–16053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Annabi, M.; M’Chirgui, A.; Azzouz, F.B.; Zouaoui, M.; Salem, M.B. Effects of nano-Al2O3 particles on the superconductivity of Pb-doped BSCCO. Phys. Stat. Sol. C 2004, 1, 1920–1923. [Google Scholar]

- Fallah-Arani, H.; Koohani, H.; Tehrani, F.S.; Noori, N.R.; Nodoushan, N.J. The structural, magnetic, and pinning features of Bi-2223 superconductors: Effects of SiC nanoparticles addition. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 31121–31128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, A.T.; Le, T.; Nguyen, H.L.; Nguyen, H.N.; Nguyen, T.B.; Pham, P.; Nguyen, K.M.; Dang, T.B.H.; Pham, N.T.; Kieu, X.T.; et al. Effect of FePd nanoparticle addition on the superconductivity of Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+δ compounds. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 44736–44737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Sun, A.M.; Xu, B.; Zhang, H.T.; Zhang, M. Effect of the BSCCO superconducting properties by tiny Y2O3 addition. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2016, 30, 1650328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.P.; Zhang, Y.R.; Gao, S.L.; Zheng, Q.H.; Zhang, T.T.; Cheng, G.T.; Cao, S.Z.; Hang, W.P.; Ramakrishna, S.; Long, Y.Z. Fabrication and magnetic properties of SiO2 nanoparticles-doped BSCCO superconducting nanofibers by solution blow spinning. Phys. C 2023, 608, 1354251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelati, A.; Amirabadizadeh, A.; Kompany, A.; Salamati, H.; Sonier, J. Effect of Eu2O3 Nanoparticles Addition on Structural and Superconducting Properties of BSCCO. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2014, 27, 1369–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Arani, H.; Baghshahi, S.; Sedghi, A.; Riahi-Noori, N. Enhancement in the performance of BSCCO (Bi-2223) superconductor with functionalized TiO2 nanorod additive. Ceram. Int. 2019, 45, 21878–21886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, M.S.; Hamed, M.H.; Yousif, N.M.; Hashem, H.M. The impact of the addition of Bi2Te3 nanoparticles on the structural and the magnetic properties of the Bi-2223 high-Tc superconductor. Ceram. Int. 2021, 47, 25236–25248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilhamsyah, A.B.P.; Zabidi, N.A.M.; Hashidi, M.A.H.; Suib, N.R.M.; Mahat, A.M.; Abd-Shukor, R.; Masnita, M.J. Effect of copper (II) sulfide addition on the transport critical current density and AC susceptibility of Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3O10 superconductor. Appl. Phys. A 2024, 130, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, L.H.; Pham, A.T.; Thien, N.D.; Nam, N.H.; Riviere, E.; Pham, Q.N.; Man, N.K.; Binh, N.T.; Hong, N.T.M.; Cuong, L.; et al. Enhancements of critical current density in Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3O10+δ superconductors by additions of SnO2 nanoparticles. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 27614–27621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suib, N.R.M.; Ilhamsyah, A.B.P.; Mujaini, M.; Mahat, A.M.; Abd-Shukor, R. AC Susceptibility and Electrical Properties of BiFeO3 Nanoparticles Added Bi1.6Pb0.4Sr2Ca2Cu3O10 Superconductor. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2023, 36, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Makdah, M.H.; El Ghouch, N.; El-Dakdouki, M.H.; Awad, R.; Matar, M. Synthesis, characterization, and Vickers microhardness for (YIG)x/(Bi, Pb)-2223 superconducting phase. Ceram. Int 2023, 49, 22400–22422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karan, S.M.; Chattoraj, T.; Ali, M.A.; Banerjee, S.S. Co2C Nanoparticle-Decorated Grain Boundaries: A Source of Robust, Thermally Stable Vortex Pinning in Bi-2223 High Tc Superconductors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 7, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llordés, A.; Palau, A.; Gázquez, J.; Coll, M.; Vlad, R.; Pomar, A.; Arbiol, J.; Guzmán, R.; Ye, S.; Rouco, V.; et al. Nanoscale strain-induced pair suppression as a vortex-pinning mechanism in high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Mater. 2012, 11, 329–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlan, R.M.; Malozemoff, A.P.; Larbalestier, D.C. Superconducting materials for large scale applications. Proc. IEEE 2004, 92, 1639–1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, K.; Horide, T.; Osamura, K.; Mukaida, M.; Yoshida, Y.; Ichinose, A.; Horii, S. Enhancement of critical current density of YBCO films by introduction of artificial pinning centers due to the distributed nano-scaled Y2O3 islands on substrates. Phys. C 2004, 412, 1267–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feighan, J.P.F.; Kursumovic, A.; MacManus-Driscoll, J.L. Materials design for artificial pinning centres in superconductor PLD coated conductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2017, 30, 123001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horide, T.; Kawamura, T.; Matsumoto, K.; Ichinose, A.; Yoshizumi, M.; Izumi, T.; Shiohara, Y. Jc improvement by double artificial pinning centers of BaSnO3 nanorods and Y2O3 nanoparticles in YBa2Cu3O7 coated conductors. Supercond. Sci. 2013, 26, 075019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.R.; Kang, L.; Zhao, Q.; Fu, Q.H.; Song, J.; Zhao, X.P. Effect of nonuniform-defect split ring resonators on the left-handed metamaterials. Acta Phys. Sin. 2005, 54, 1607–1612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, F.L.; Zhao, Q.; Liu, Y.H.; Luo, C.R.; Zhao, X.P. Behaviour of hexagon split ring resonators and left-handed metamaterials. Chin. Phys. Lett. 2004, 21, 1330–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninova, V.N.; Yost, B.; Zander, K.; Osofsky, M.S.; Kim, H.; Saha, S.; Greene, R.L.; Smolyaninov, I.I. Experimental demonstration of superconducting critical temperature increase in electromagnetic metamaterials. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 7321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolyaninov, I.I.; Smolyaninova, V.N. Theoretical modeling of critical temperature increase in metamaterial superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 2016, 93, 184510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, P.F.; Calvin, J.J.; Woodfield, B.F.; Smolyaninova, V.N.; Prestigiacomo, J.C.; Osofsky, M.S.; Smolyaninov, I.I. Normal state specific heat of a core-shell aluminum-alumina metamaterial composite with enhanced Tc. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 024512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fausti, D.; Tobey, R.I.; Dean, N.; Kaiser, S.; Dienst, A.; Hoffmann, M.C.; Pyon, S.; Takayama, T.; Takagi, H.; Cavalleri, A. Light-Induced Superconductivity in a Stripe-Ordered Cuprate. Science 2011, 331, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicoletti, D.; Casandruc, E.; Laplace, Y.; Khanna, V.; Hunt, C.R.; Kaiser, S.; Dhesi, S.S.; Gu, G.D.; Hill, J.P.; Cavalleri, A. Optically induced superconductivity in striped La2−xBaxCuO4 by polarization-selective excitation in the near infrared. Phys. Rev. B 2014, 90, 100503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitrano, M.; Cantaluppi, A.; Nicoletti, D.; Kaiser, S.; Perucchi, A.; Lupi, S.; Di Pietro, P.; Pontiroli, D.; Riccò, M.; Clark, S.R.; et al. Possible light-induced superconductivity in K3C60 at high temperature. Nature 2016, 530, 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantaluppi, A.; Buzzi, M.; Jotzu, G.; Nicoletti, D.; Mitrano, M.; Pontiroli, D.; Riccò, M.; Perucchi, A.; Di Pietro, P.; Cavalleri, A. Pressure tuning of light-induced superconductivity in K3C60. Nat. Phys. 2018, 14, 837–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fava, S.; De Vecchi, G.; Jotzu, G.; Buzzi, M.; Gebert, T.; Liu, Y.; Keimer, B.; Cavalleri, A. Magnetic field expulsion in optically driven YBa2Cu3O6.48. Nature 2024, 632, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.W.; Tao, S.; Chen, G.W.; Zhao, X.P. Improving the Critical Temperature of MgB2 Superconducting Metamaterials Induced by Electroluminescence. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2016, 29, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, S.; Li, Y.B.; Chen, G.W.; Zhao, X.P. Critical Temperature of Smart Meta-superconducting MgB2. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2017, 30, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.G.; Li, Y.B.; Chen, G.W.; Xu, L.X.; Zhao, X.P. The Effect of Inhomogeneous Phase on the Critical Temperature of Smart Meta-superconductor MgB2. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2018, 31, 3175–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Chen, H.G.; Qi, W.C.; Chen, G.W.; Zhao, X.P. Inhomogeneous Phase Effect of Smart Meta-Superconducting. J. Low Temp. Phys. 2018, 191, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Chen, H.G.; Wang, M.Z.; Xu, L.X.; Zhao, X.P. Smart meta-superconductor MgB2 constructed by the dopant phase of luminescent nanocomposite. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.B.; Han, G.Y.; Zou, H.Y.; Tang, L.; Chen, H.G.; Zhao, X.P. Reinforcing Increase of ΔTc in MgB2 Smart Meta-Superconductors by Adjusting the Concentration of Inhomogeneous Phases. Materials 2021, 14, 3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Han, G.; Shi, M.; Zhao, X. Smart Metastructure Method for Increasing Tc of Bi(Pb)SrCaCuO High-Temperature Superconductors. J. Supercond. Nov. Magn. 2020, 33, 3015–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.G.; Wang, M.Z.; Qi, Y.; Li, Y.B.; Zhao, X.P. Relationship between the Tc of Smart Meta-Superconductor Bi(Pb)SrCaCuO and Inhomogeneous Phase Content. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.G.; Li, Y.B.; Qi, Y.; Wang, M.Z.; Zou, H.Y.; Zhao, X.P. Critical Current Density and Meissner Effect of Smart Meta-Superconductor MgB2 and Bi(Pb)SrCaCuO. Materials 2022, 15, 972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, D.; Li, Y.B.; Sun, C.; Hai, Q.Y.; Shi, M.; Chen, H.G.; Zhao, X.P. Green-light p-n junction particle inhomogeneous phase enhancement of MgB2 smart meta-superconductors. J. Mater. Sci.: Mater. Electron. 2024, 35, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, D.; Sun, C.; Hai, Q.Y.; Zhao, X.P. The Influence of Electroluminescent Inhomogeneous Phase Addition on Enhancing MgB2 Superconducting Performance and Magnetic Flux Pinning. Materials 2024, 17, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hai, Q.Y.; Chen, H.G.; Sun, C.; Chen, D.; Qi, Y.; Shi, M.; Zhao, X.P. Green-Light GaN p-n Junction Luminescent Particles Enhance the Superconducting Properties of B(P)SCCO Smart Meta-Superconductors (SMSCs). Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Bi, R.Y.; Xun, L.F.; Li, X.Y.; Hai, Q.Y.; Qi, Y.; Zhao, X.P. Core-Shell Composite GaP Nanoparticles with Efficient Electroluminescent Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Chen, D.; Bi, R.Y.; Hai, Q.Y.; Xun, L.F.; Li, X.Y.; Zhao, X.P. The effect of GaP quantum dot luminescent addition on the superconducting properties and electron-phonon coupling in MgB2. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 24043–24052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timusk, T.; Statt, B. The pseudogap in high-temperature superconductors: An experimental survey. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1999, 62, 61–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeal, N.; Lesueur, J.; Aprili, M.; Faini, G.; Contour, J.P.; Leridon, B. Pairing fluctuations in the pseudogap state of copper-oxide superconductors probed by the Josephson effect. Nat. Phys. 2008, 4, 608–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Pineda, E.M.; Rivera-Contreras, L.J.; Pineda-Peña, G.; Téllez, D.A.L.; Roa-Rojas, J. Observation of the Granular Josephson Mechanism and the Vortex-Glass Transition in the Polycrystalline GdBa2Cu3O7- δ Superconductor. J. Supercond. Novel Magn. 2024, 37, 1957–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraitis, P.; Koutsokeras, L.; Stamopoulos, D. AC Magnetic Susceptibility: Mathematical Modeling and Experimental Realization on Poly-Crystalline and Single-Crystalline High-Tc Superconductors YBa2Cu3O7−δ and Bi2−xPbxSr2Ca2Cu3O10+y. Materials 2024, 17, 1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolo, M. In Numerical Modeling of Ac Susceptibility and Induced Nonlinear Voltage Waveforms of High-Tc Granular Superconductors. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Application of Mathematics in Technical and Natural Sciences (AMiTaNS), Albena, Bulgaria, 20–25 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klamu, P.W. AC Susceptibility and Resistivity of the Granular Nd1.85Ce0.15CuO4.03. Phys. Stat. Sol. (A) 1993, 136, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamopoulos, D.; Speliotis, A.; Niarchos, D. From the second magnetization peak to peak effect. A study of superconducting properties in Nb films and MgB2 bulk samples. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2004, 17, 1261–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz, H.S.; Hänisch, J.; Polichetti, M.; Galluzzi, A.; Gozzelino, L.; Torsello, D.; Milošević-Govedarović, S.; Grbović-Novaković, J.; Dobrovolskiy, O.V.; Lang, W.; et al. Critical current density in advanced superconductors. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2026, 155, 101492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.P.; Hai, Q.Y.; Shi, M.; Chen, H.G.; Li, Y.B.; Qi, Y. An Improved Smart Meta-Superconductor MgB2. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivlev, B.I.; Lisitsyn, S.G.; Eliashberg, G.M. Nonequilibrium Excitations in Superconductors in High-Frequency Fields. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1973, 10, 449–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyatt, A.F.G.; Dmitriev, V.M.; Moore, W.S.; Sheard, F.W. Microwave-Enhanced Critical Supercurrents in Constricted Tin Films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1966, 16, 1166–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachmann, M.; Croitoru, M.D.; Vagov, A.; Axt, V.M.; Papenkort, T.; Kuhn, T. Ultrafast terahertz-field-induced dynamics of superconducting bulk and quasi-1D samples. New. J. Phys. 2013, 15, 055016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsunaga, R.; Tsuji, N.; Fujita, H.; Sugioka, A.; Makise, K.; Uzawa, Y.; Terai, H.; Wang, Z.; Aoki, H.; Shimano, R. Light-induced collective pseudospin precession resonating with Higgs mode in asuperconductor. Science 2014, 345, 1145–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Zhao, C.; Xia, B.; Ma, H.; Chen, H.; Cai, J.; Yang, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, L.; Guan, D.; et al. Interface-enhanced superconductivity in monolayer 1T’-MoTe2 on SrTiO3(001). Quantum Front. 2023, 2, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiora, J.; Wang, X.; Zheng, R. Superconductivity and interfaces. Phys. Rep. 2024, 1076, 1–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Hetero-Phase | EL Intensity a.u. | Addition Content wt.% | Sintering Process |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | / | / | 0 | 840 °C 120 h |

| S1 | GaP | / | 0.2 | 840 °C 120 h |

| S2 | GaP (1:1.4:1.4) | 2100 | 0.2 | 840 °C 120 h |

| S3 | GaP (1:1:1) | 2950 | 0.15 | 840 °C 120 h |

| S4 | GaP (1:1:1) | 2950 | 0.2 | 840 °C 120 h |

| Sample | Lattice Parameters of (Bi,Pb)-2223 | Phase Volume Fractions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | b (Å) | c (Å) | V (Å3) | 2223% | 2212% | 2201% | |

| S0 | 5.41 | 5.42 | 37.12 | 1089.8 | 94.49 | 2.41 | 3.1 |

| S1 | 5.41 | 5.41 | 37.10 | 1086.0 | 93.35 | 3.45 | 3.20 |

| S2 | 5.41 | 5.42 | 37.12 | 1089.1 | 92.49 | 5.27 | 3.24 |

| S3 | 5.41 | 5.42 | 37.12 | 1089.0 | 95.39 | 2.21 | 2.4 |

| S4 | 5.41 | 5.42 | 37.12 | 1080.1 | 94.16 | 3.64 | 2.2 |

| Sample | Tc,0 (K) | Tc,on (K) | Tc (K) | ΔT (K) | R295K (mΩ) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S0 | 103 ± 0.14 | 114 ± 0.12 | 107 ± 0.2 | 11 | 6.30 |

| S1 | 95 ± 0.17 | 112 ± 0.13 | 104 ± 0.18 | 17 | 11.90 |

| S2 | 97 ± 0.11 | 113 ± 0.16 | 105 ± 0.14 | 16 | 10.97 |

| S3 | 98 ± 0.15 | 114 ± 0.18 | 106 ± 0.15 | 16 | 10.32 |

| S4 | 102 ± 0.19 | 114 ± 0.14 | 109 ± 0.16 | 12 | 11.73 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hai, Q.; Chen, D.; Bi, R.; Qi, Y.; Xun, L.; Li, X.; Zhao, X. Tunable Superconductivity in BSCCO via GaP Quantum Dots. Materials 2025, 18, 5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235458

Hai Q, Chen D, Bi R, Qi Y, Xun L, Li X, Zhao X. Tunable Superconductivity in BSCCO via GaP Quantum Dots. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235458

Chicago/Turabian StyleHai, Qingyu, Duo Chen, Ruiyuan Bi, Yao Qi, Lifeng Xun, Xiaoyan Li, and Xiaopeng Zhao. 2025. "Tunable Superconductivity in BSCCO via GaP Quantum Dots" Materials 18, no. 23: 5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235458

APA StyleHai, Q., Chen, D., Bi, R., Qi, Y., Xun, L., Li, X., & Zhao, X. (2025). Tunable Superconductivity in BSCCO via GaP Quantum Dots. Materials, 18(23), 5458. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235458