Sustainable Cold Mix Asphalt: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Innovations, Circular Economy Integration, Field Performance, and Decarbonization Pathways

Abstract

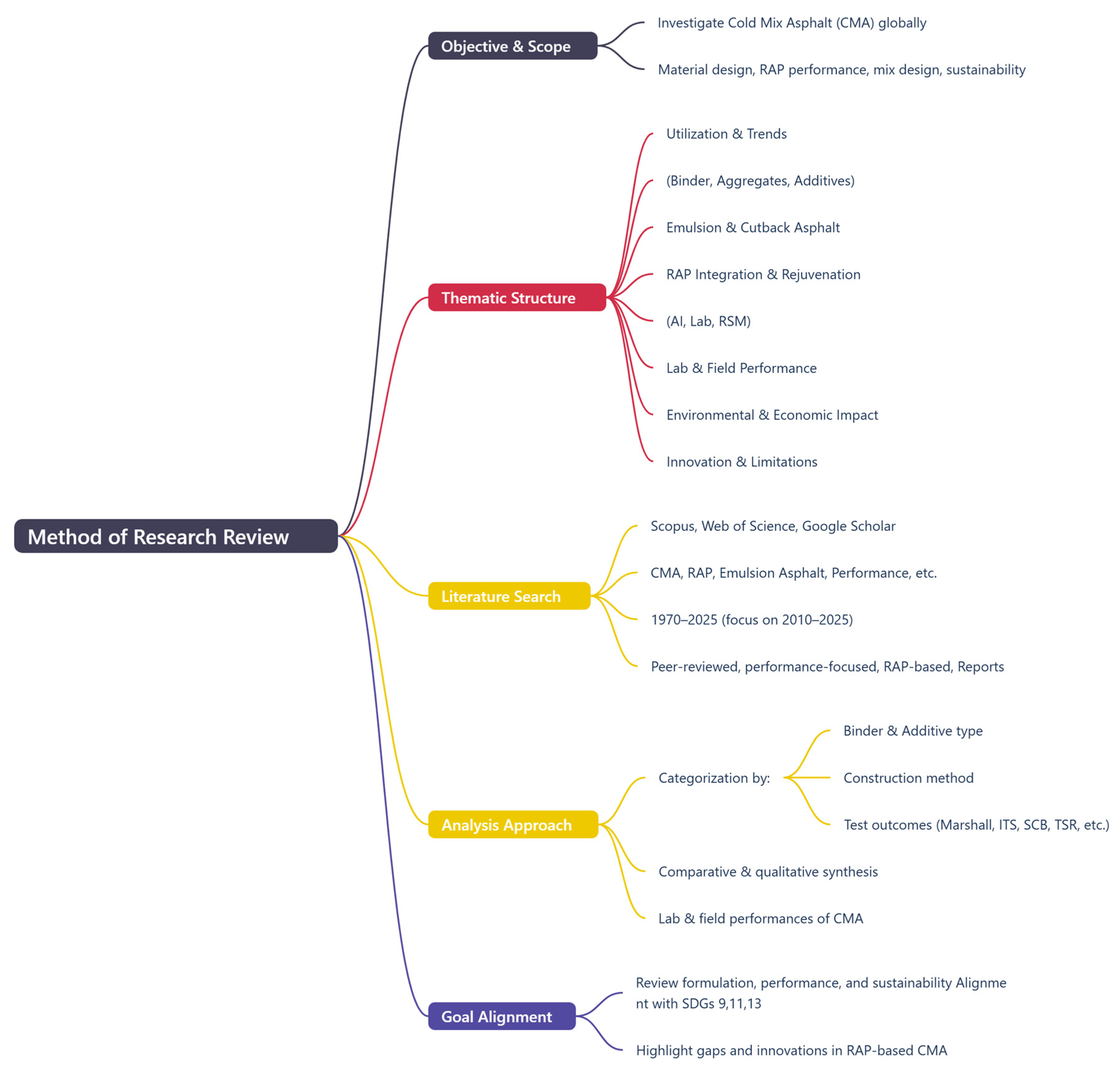

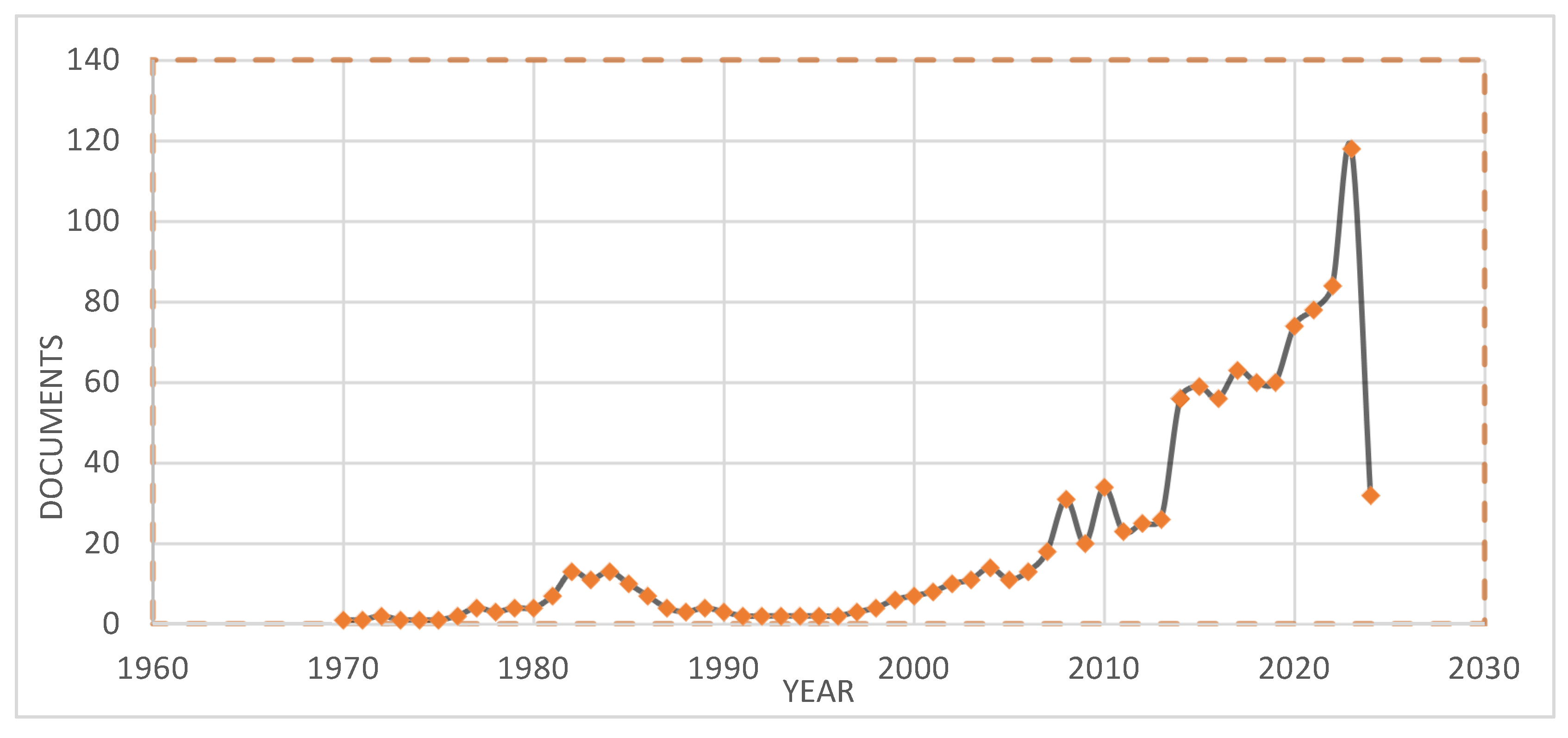

1. Introduction

- Material innovation: A chemo-rheological optimization of the binder-aggregate interface.

- Performance validation: An analysis of advanced characterization methods and a critical look at the methodological gaps in current testing standards.

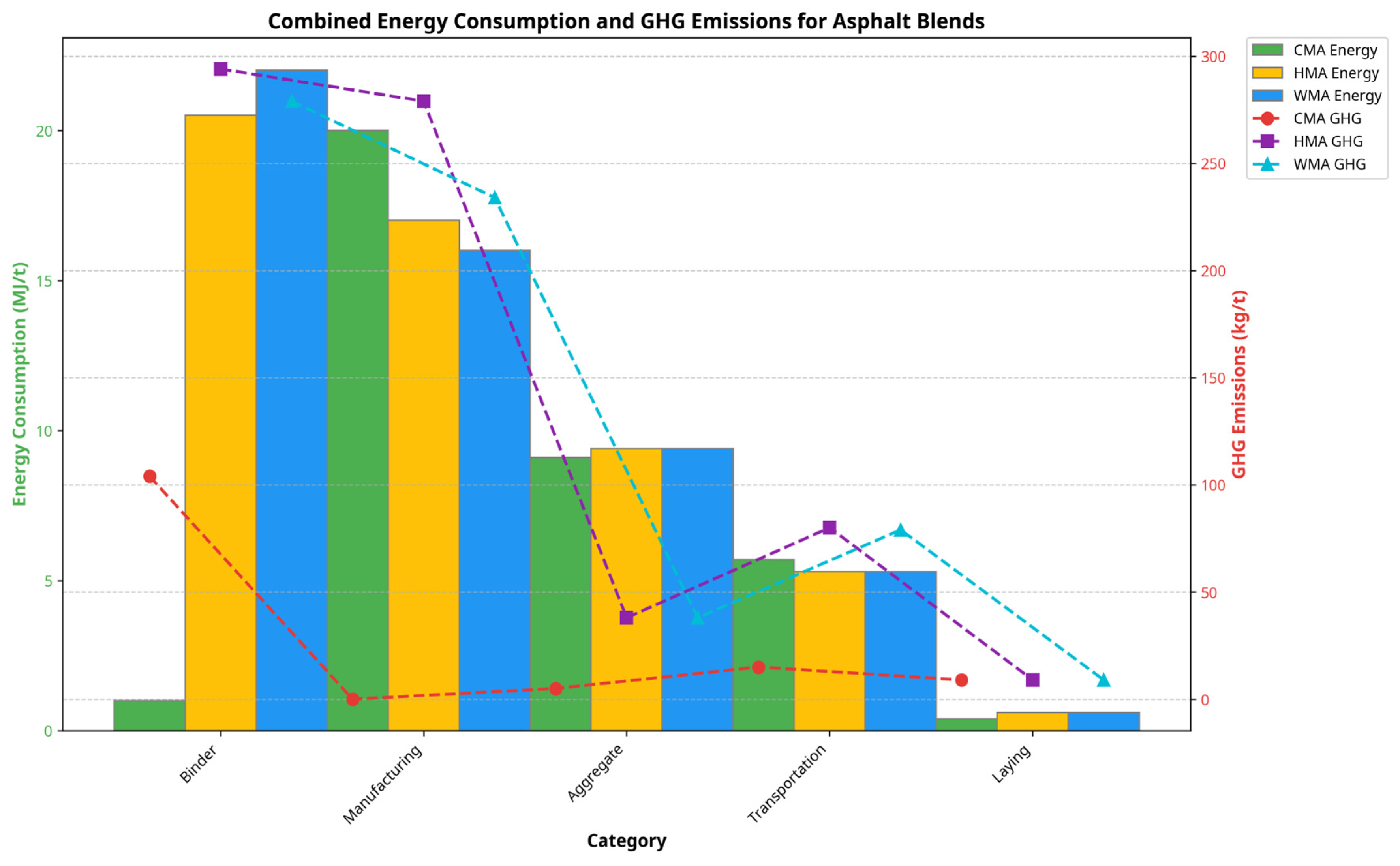

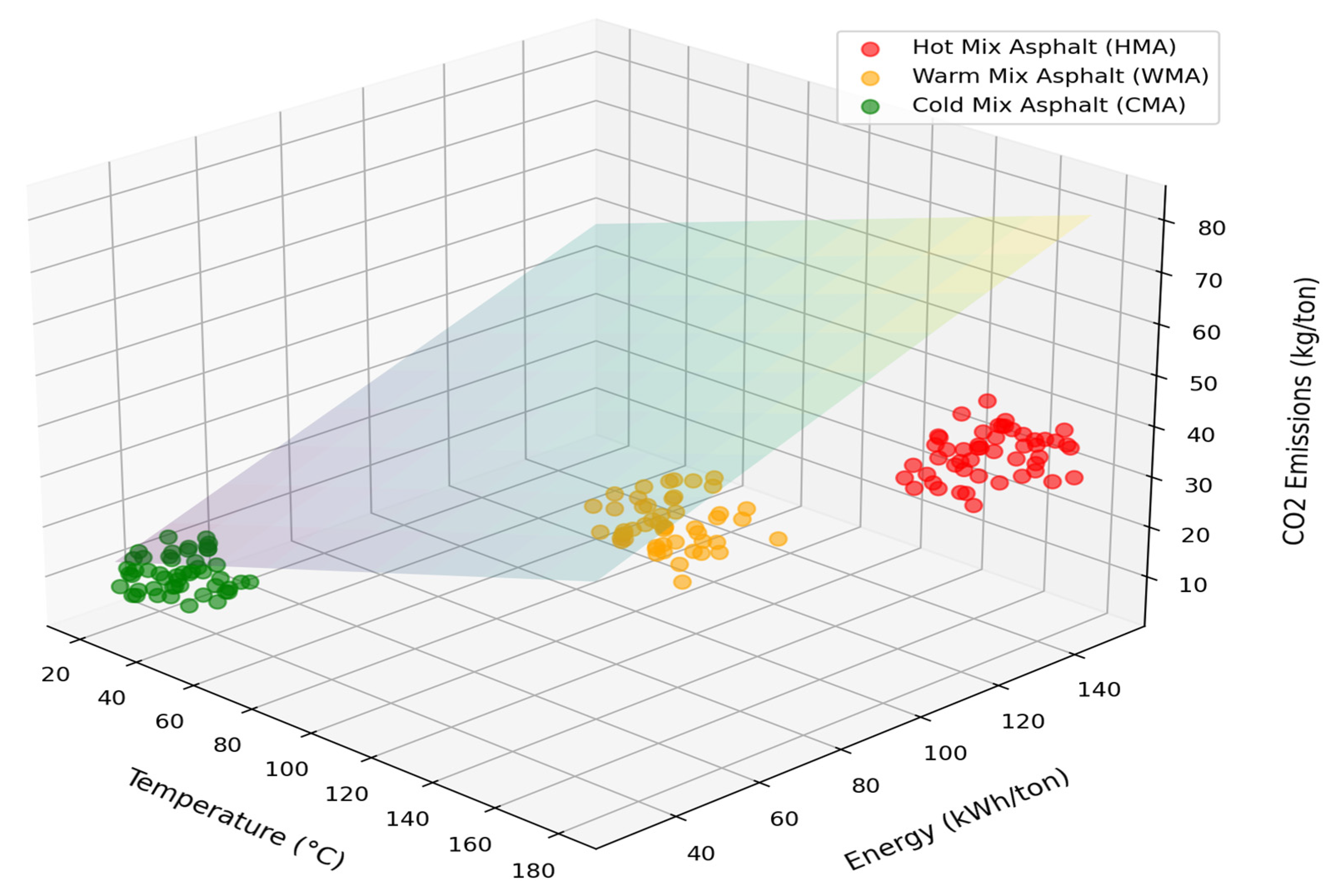

- Comparative Sustainability metrics: A life-cycle assessment (LCA) of modern CMA compared to traditional HMA/WMA alternatives.

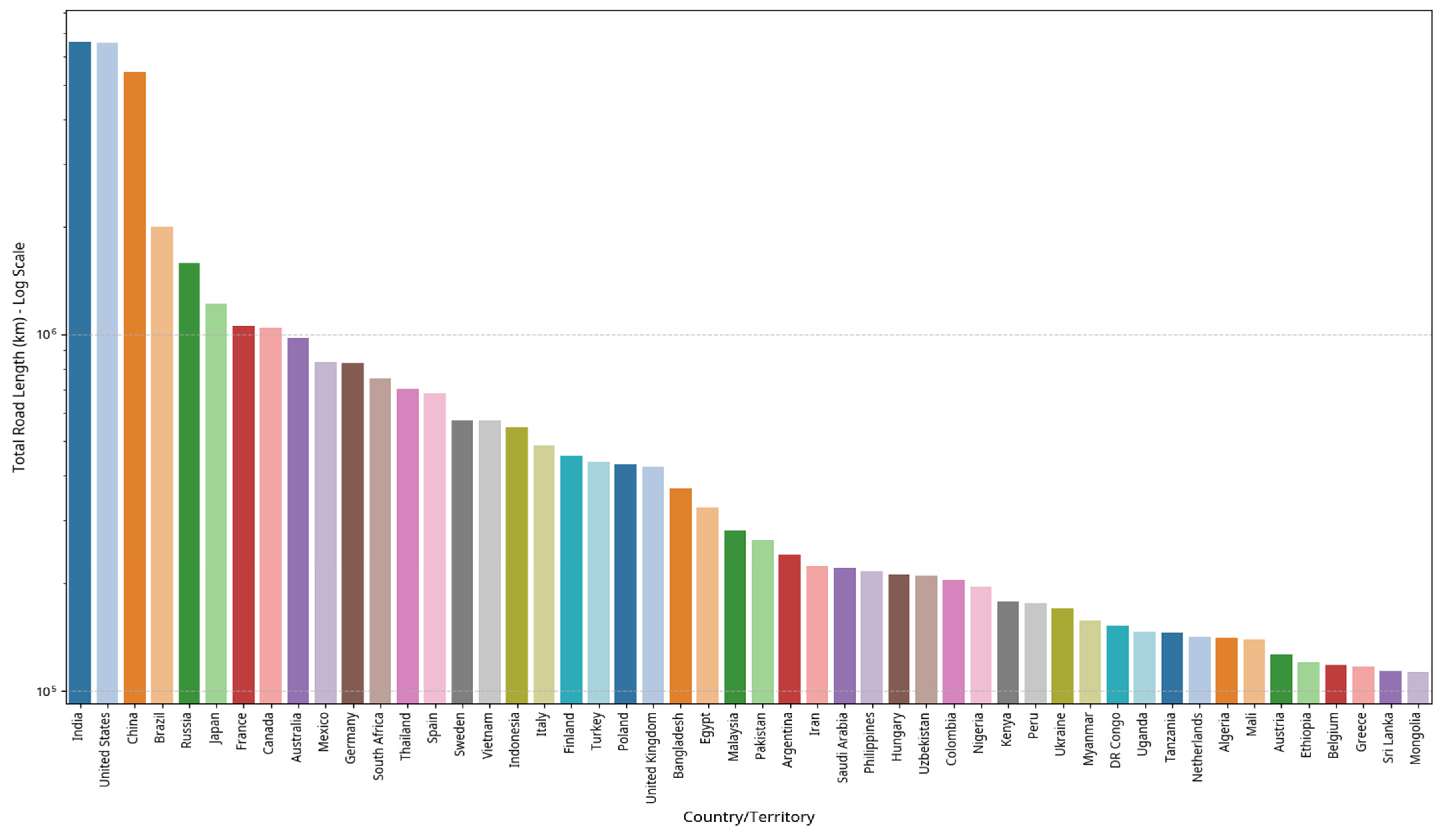

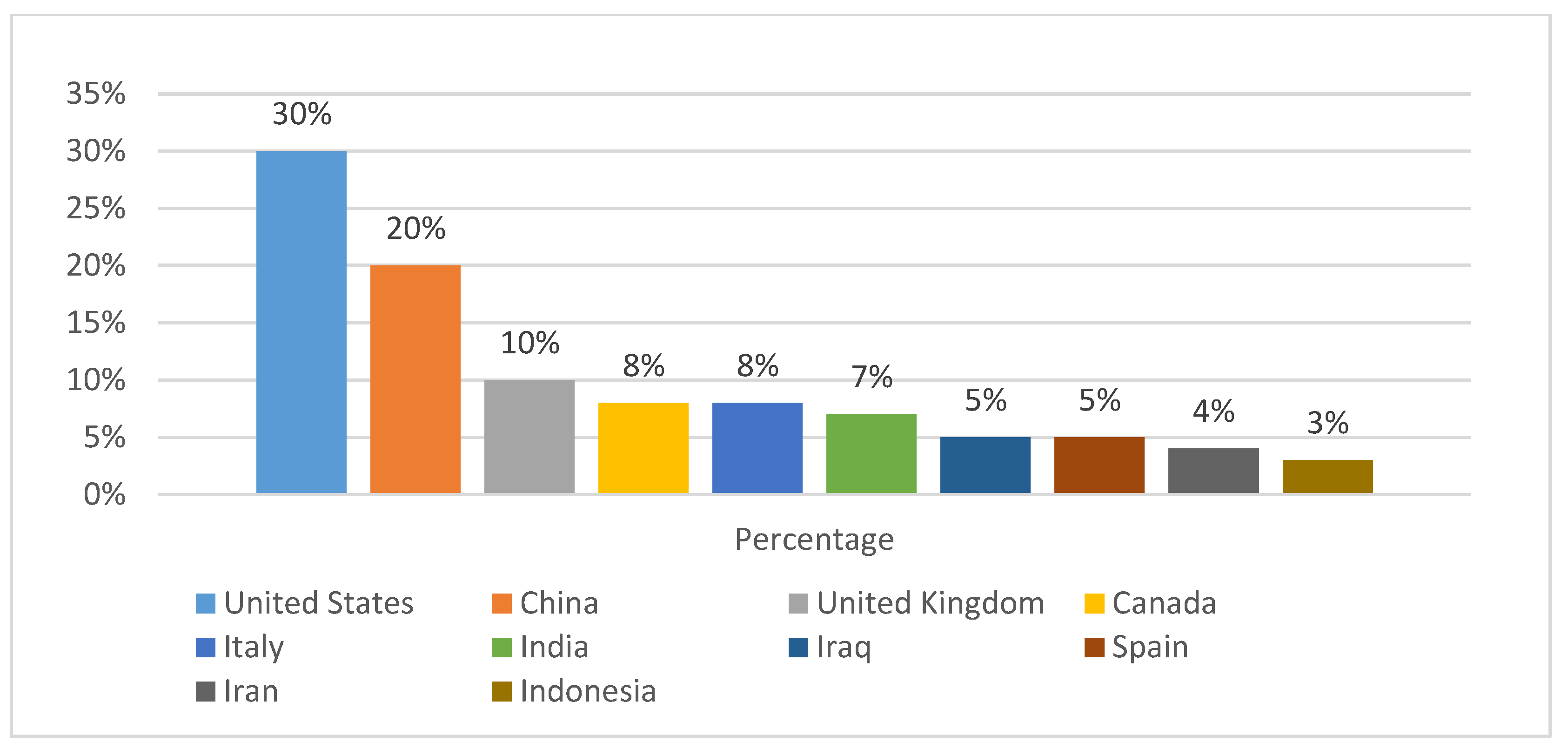

2. Global Utilization and Economic–Environmental Rationale

3. Material Composition and Chemo-Rheological Design

- Aggregates: Aggregates form the backbone of CMA and are carefully selected to achieve an optimal gradation, typically with a nominal maximum size below 12.5 mm. The particle size distribution generally follows established gradation frameworks, such as LB-10 or UPM-13, ensuring a dense, stable aggregate matrix. Incorporating 4–8% limestone aggregate (≤0.075 mm) into the mix will result in an increase in packing density to greater than 78%, which can result in better load transfer and improved rigidity. Angular crushed aggregate with a Los Angeles (LA) abrasion value less than 25% provides superior interlock characteristics and superior rut-resistant characteristics under traffic conditions [32].

- Binder: Binder is the binding agent that holds the aggregate together; binder is usually an emulsified asphalt (cationic CSS-1h) or cutback asphalt (MC-70) with a bitumen content between 60 and 70%. The binders are engineered to exhibit predictable failure behavior, enabling demulsification within 30 min at 25 °C for proper application and early strength development. Bio-based diluents are often incorporated to improve workability at ambient temperature by decreasing viscosity from 10–20 cP to 1–3 Pa·s at 25 °C, while providing a minimum flash point of 200 °C to ensure a safe, performant product [4,33].

- Additives: A range of polymeric and nano-scale modifiers are employed to strengthen the cohesion–adhesion balance of the mix [34]. Common examples include SBS elastomers (around 2% by weight) and nano-clay (0.5–1.5% by weight), both of which can boost Marshall stability from 0.5–1.5 kN in unmodified CMA to 4–12 kN in modified mixtures. Anti-stripping agents, such as hydrated lime (1–2% by weight), are also incorporated to improve moisture resistance, helping the mix retain a TSR of over 85% after 24 h of water immersion [35,36].

3.1. Emulsion Chemistry and Its Influence on CMA Performance

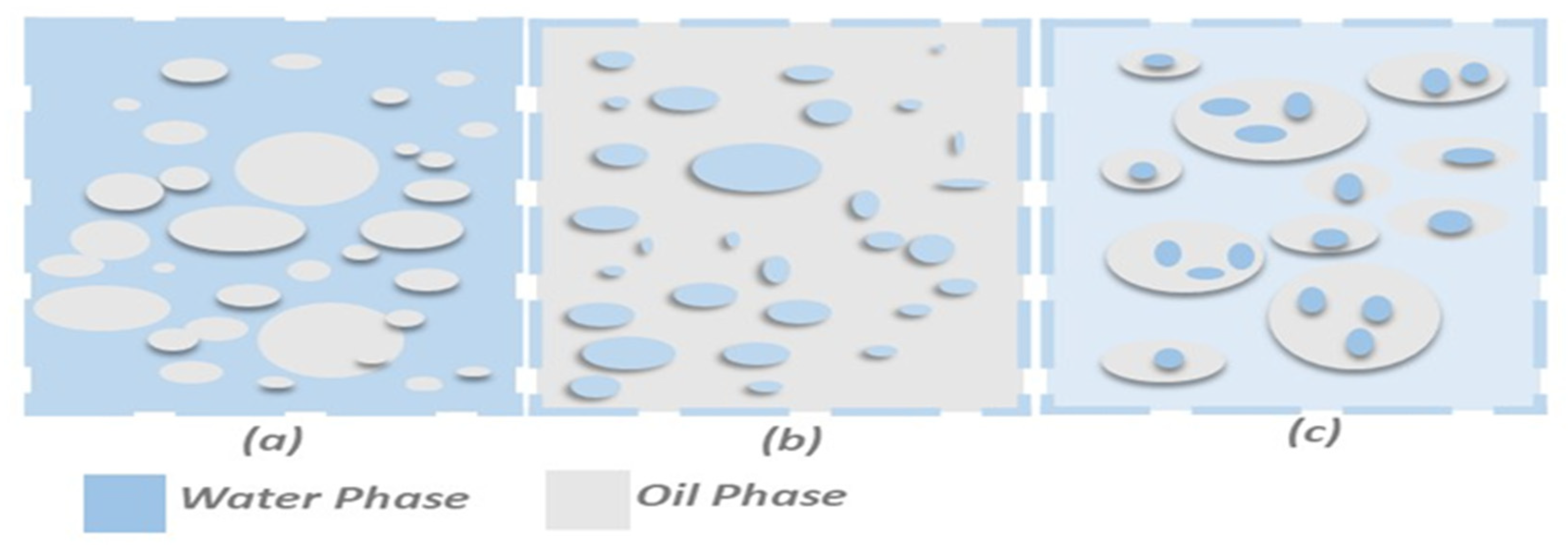

3.1.1. Emulsion Type and Electrical Charge

3.1.2. Breaking Mechanism and Curing Behavior

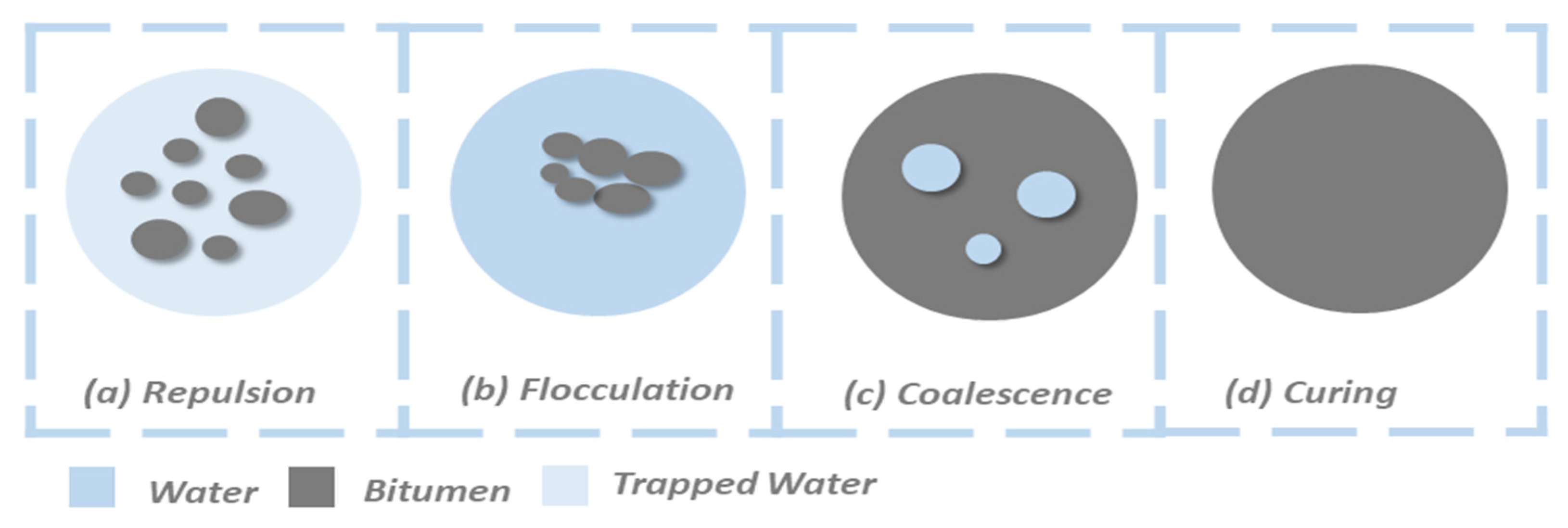

- Stage I-Flocculation: As water dilutes the surfactant, the zeta potential drops from stable ranges (+40–70 mV for cationic and −40–60 mV for anionic) to a critical level (~20–25 mV). Reduced electrostatic repulsion allows droplets to collide under Brownian motion, requiring <10 kT activation energy [41,42,43].

- Stage II-Coalescence: When the flocculated droplets come into contact with each other, a thin layer of water forms between them. The film will collapse when the capillary pressure is greater than 5 kPa. At that point, the residual zeta potential (approximately ±10–20 mV) will not be enough to prevent the droplets from merging more rapidly [41,42,43].

- Stage III-Curing: In the final stage of this process, the remaining water between the droplets will evaporate, and the binder will redistribute until the asphalt film has solidified. If there is too much humidity (greater than 90%), then the curing of the asphalt film may take two to three times as long because the retained moisture will delay the complete coalescence of the droplets [41,42,43].

3.1.3. Formulation and Performance-Enhancing Additives

- Polymers: Styrene-Butadiene-Styrene (SBS) and other polymers are frequently incorporated into the base bitumen before emulsification. When the polymer is mixed into the bitumen, the polymer creates a network in the binder, which increases the binder’s elastic properties, increases rutting resistance, and extends the binder’s fatigue life [29,41].

- Adhesion Promoters: After choosing the right charge for the emulsion, chemicals called anti-stripping agents are commonly used to increase the adhesion between the aggregate and binder and to improve water resistance [41].

3.2. Global Emulsion Standards and Innovations

- Nordic (Sweden):

- Western Europe:

- Southeast Asia:

- Graphene

- Microencapsulated bio-rejuvenators:

3.3. Cutback Asphalt: Composition, Classification, and Applications

- RC: Contains volatile solvents that evaporate quickly, allowing traffic to return rapidly. Ideal for patching and surface treatments.

- MC: Features a moderate evaporation rate, providing good workability and effectiveness for base courses and surface treatments [58].

- SC: Contains minimal volatile solvents, giving extended work time and suitability for prime coat applications and CMA treatments.

3.4. Aggregate and Water Composition

4. Production and Storage of CMA

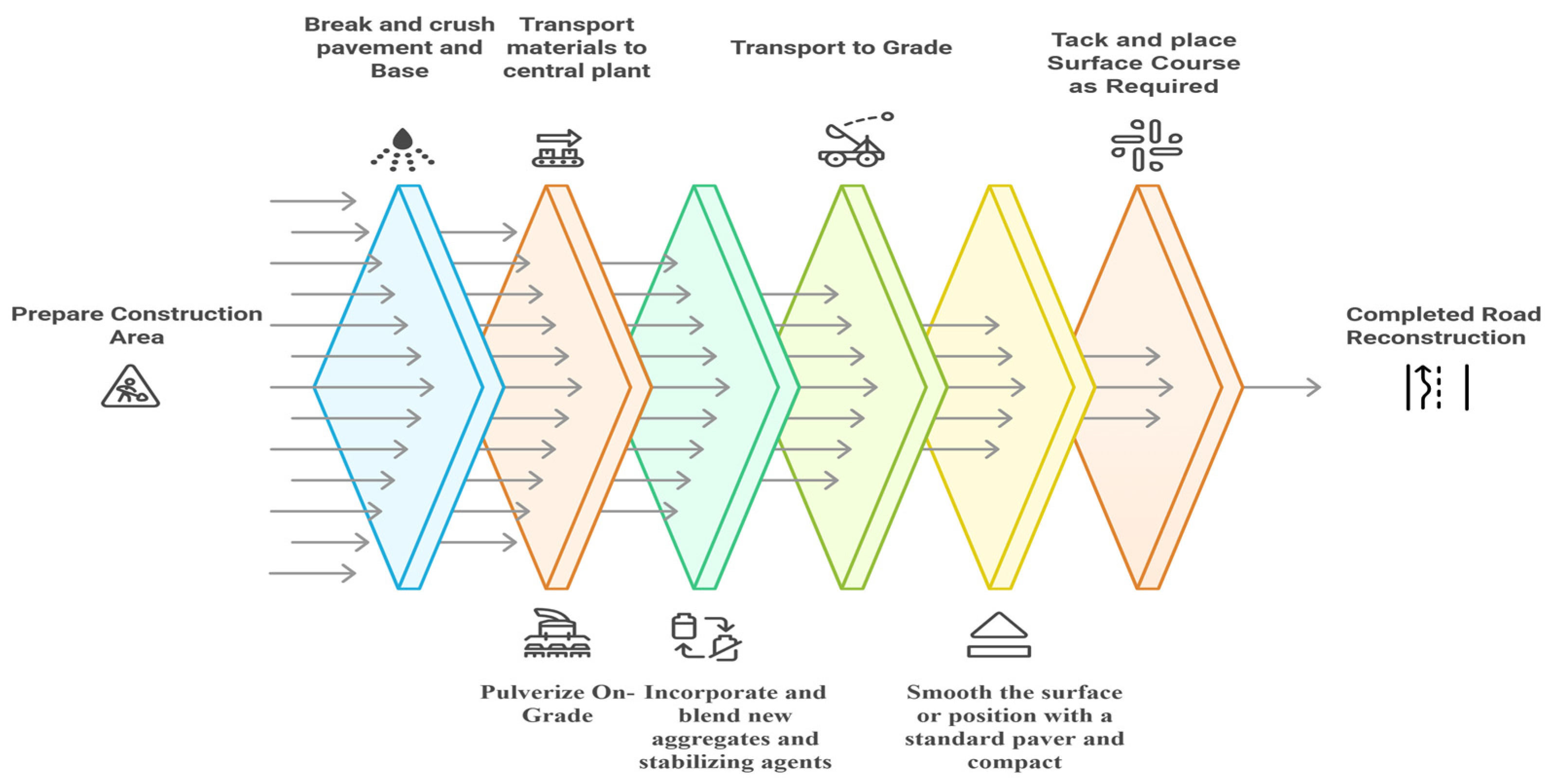

4.1. Mixed-in-Place (MIP) CMA

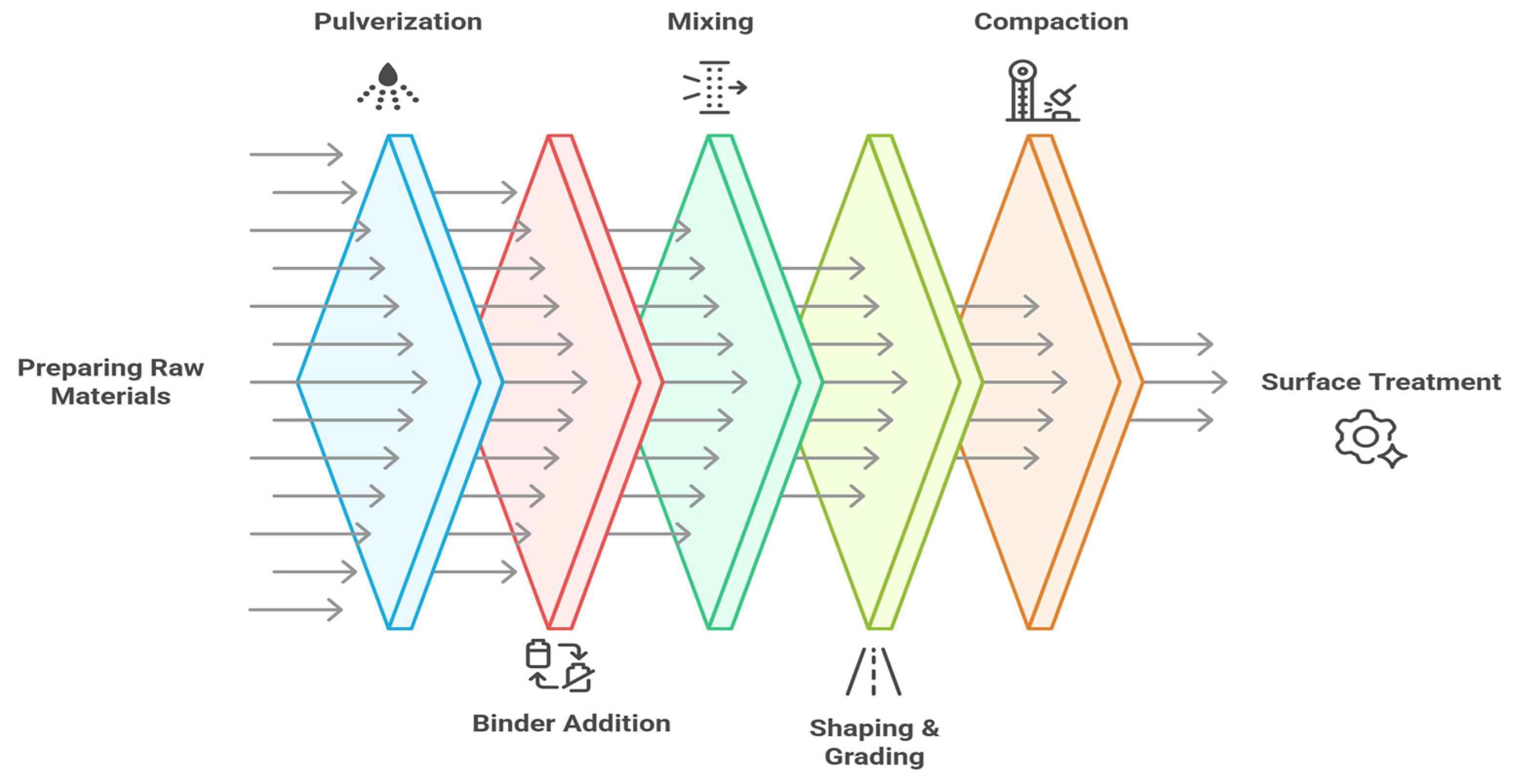

4.2. Central-Plant Mixing (CPM) CMA

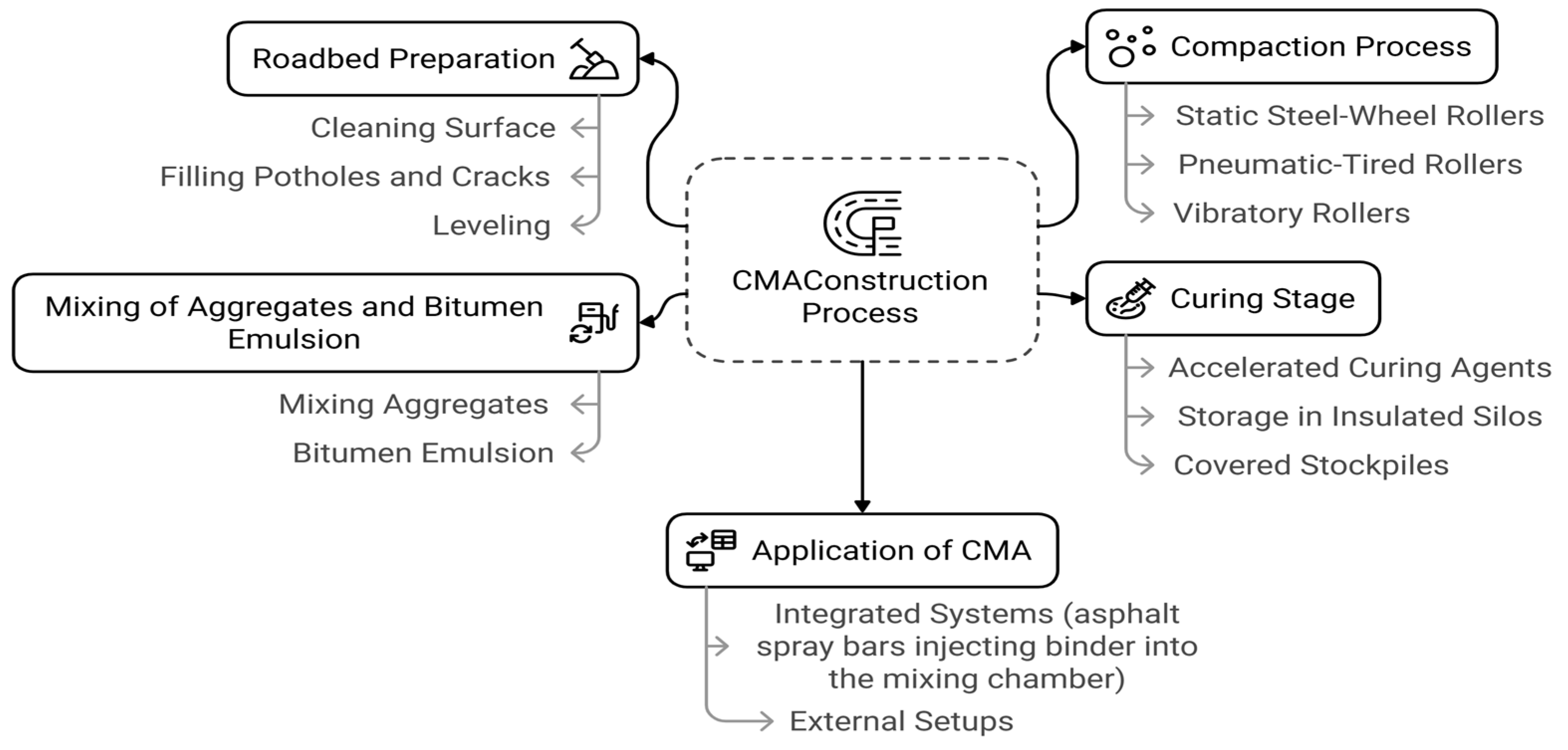

4.3. Construction Process of CMA

5. RAP in CMA: Rejuvenator-Driven Performance and Challenges

6. Mix Design Approaches for CMA

6.1. Overview of CMA Mix Design Philosophy

6.2. Laboratory-Based Mix Design

Key Factors Affecting Laboratory CMA Performance

| References | Conditioning Temperature | Time for Conditioning (Days) | Bitumen Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| [89] | 38 °C | 7, 28 | BM |

| Ambient | 1 | FM | |

| 38 °C | 7–14 | BM | |

| [85] | Ambient | 7 | FM |

| Ambient | 28 | FM | |

| 60 °C | 2 | FM | |

| [90] | 60 °C | 1, 3, and 7 | Both |

| [91] | 60 °C | 2 | BM |

| [92] | 40 °C | 18–21 | BM |

| [93] | 60 °C | 2 | Both |

| 20 °C | 101 | BM | |

| [94] | 38 °C, 40 °C, 60 °C | 1, 7, and 28 | BM |

| [81] | Ambient, 40 °C, 60 °C | 7–84 days (1–12 weeks) | CSS |

| [95] | 25 °C, 40 °C | 28 days | Foamed 50/70 bitumen |

6.3. Asphalt Institute Method of Mix Design

- 24 h in mold at 25 °C;

- 24 h in oven at 40 °C;

- 24 h stabilization in mold at 25 °C;

- 48 h water immersion (soaked stability evaluation).

- It does not specify acceptable porosity ranges.

- The definitions of fully cured and ultimate strength remain ambiguous.

- Moisture parameters used in volumetric analysis are inconsistent with modern standards.

6.4. Performance-Based Mix Design

- Low traffic (<3 MESA): ITS (dry/wet) and TSR;

- Medium traffic (3–6 MESA): ITS after moisture equilibration and soaking;

- High traffic (>6 MESA): triaxial testing for cohesion, friction angle, and moisture durability.

6.4.1. The Phenomenon of TSR Values Above 100%

6.4.2. Optimization of CMA Mix Design Using Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

7. Performance Evaluation of CMA

7.1. Laboratory Studies on the Performance of CMA

7.1.1. Effect of Aggregate and Gradation on the Performance of CMA

7.1.2. Effect of Additives on the Performance of CMA

7.1.3. Effect of Fillers on the Performance of CMA

7.1.4. Effect of Fiber Addition on the Performance of CMA

7.1.5. Effect of Compaction on the Performance of CMA

7.1.6. Effect of Curing on the Performance of CMA

- Curing time: Extending the curing period from 1 to 12 weeks raised the resilient modulus by 195% (0.85 → 2.51 GPa) and ITS by 144% (230 → 561 kPa) for the 4% BE mix.

- Moisture: Soaked curing reduced ITS by 14%, demonstrating moisture sensitivity.

- Emulsion dosage: Increased BE from 2% to 4% and cut rut depth from 13.6 to 9.0 mm and lengthened fatigue life by 49% [137].

7.2. Field Validation and Long-Term Performance of CMA

- Exceptional Durability under Heavy Traffic: On Scotland’s A90 trunk road, the Tayset CMA (70% RAP) exhibited no signs of distress after 10 years of service under extremely high traffic loads (>10 M ESA). Additionally, the stiffness stabilized at a very high level of 6 GPa within 6 months, demonstrating the long-term durability of the CMA, as well as significant carbon savings [139].

- Resilience in Extreme Climates: In a 15-year study in Sweden, it was demonstrated that CMA is a durable option, with the mix developing few cracks and no rutting over an extreme temperature range of −35 °C to 60 °C [140]. Conversely, field trials in China showed that, while AC-graded patches deteriorated rapidly in extreme cold winter conditions, open-graded LB patches did not develop defects after one year, demonstrating the importance of mix design for cold climates [141].

- Performance in High-Rainfall/High-Traffic Conditions: A CRM-E mix in Malaysia (100% RAP) displayed superior performance under extremely high rainfall and traffic (12,000 VPD/Lane). It produced higher stiffness levels than HMA (28–68%) and demonstrated excellent moisture resistance (TSR = 85–93%) and less than 2.5 mm of rutting after 12 months [142].

| Authors | Country | CMA Type | Climate and Traffic | Monitoring Duration | Summary of CMA Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shenghua Wu, Cade Marty [14] | USA | 100% RAP cold mix (with rejuvenator) | Florida (subtropical); low-volume road | 22 months | The 100% RAP CMA exhibited only minor weathering and raveling after 3 years. No cracking or rutting observed. Same-day compaction recommended for improved density and reduced raveling. |

| J. Yi et al. [141] | China | Solvent-based liquid asphalt with limestone aggregates | Severe winter; medium traffic | 10 days–1 year | Field trials revealed that AC-graded cold mix patches failed within a month, whereas open-graded LB patches showed <30 mm deformation and remained intact after one year. The LB mix’s coarser skeleton and higher voids enabled faster curing and improved durability, making it more suitable for winter pothole repair. |

| Jin, Dongzhao et al. [143] | USA (Michigan) | Cold in-place recycling (CIR) | Cold, wet; low-volume road | 20-year modeled life | CIR improved cracking and fatigue resistance under freeze–thaw cycles. Predicted rutting and IRI increases remained minimal, validating CIR for the cold, wet region. |

| David Allain et al. [144] | USA | CIR | Subtropical (Medium) | N/A | CIR and full-depth reclamation enhanced the structural strength and durability of CMA pavements. |

| Charmot et al. [142] | Malaysia | CRM-E (100% RAP + 3.5% emulsion + 1.5% OPC; HMA overlay | High rainfall; warm; 12,000 vpd/lane | 12 months | CRM-E (100% RAP with emulsion and cement) performed exceptionally under high rainfall and traffic, showing 28–68% higher stiffness than HMA, strong moisture resistance (TSR 85–93%), minimal rutting (<2.5 mm), and no cracking after 12 months. A same-day HMA overlay further improved early strength without affecting long-term durability. |

| S. Kolo et al. [61] | Nigeria | DPWS-modified (Dissolved Polythene Waste Sachets) bitumen | Tropical/subtropical; urban traffic | 4 months (intensive field monitoring) | LB-graded CMA performed well in cold regions (<30 mm deformation/year), while AC-graded mixes failed early. In tropical climates, DPWS-modified CMA with recycled polythene showed higher strength and minimal settlement, emphasizing the value of CMA-specific standards and recycled materials. |

| Dennis Day et al. [139] | UK | Tayset CMA (70% RAP + 30% virgin aggregate) with C60B5 emulsion | Cold, damp; >10 million ESA | 10 years (2008–2018) | The Tayset CMA (70% RAP, 30% virgin aggregate, C60B5 emulsion) showed no distress after 10 years and 10 million ESAs on Scotland’s A90. Its stiffness stabilized at 6 GPa within six months, with strong rutting resistance and 43 t CO2 savings, confirming its long-term durability and environmental benefits. |

| Suda, J et al. [140] | Sweden | Cold bituminous emulsion mixture | Tropical/Sub-Tropical | 15 years | After 15 years (−35 °C to 60 °C range), CMA displayed few cracks, slow binder ageing, and no rutting. RAP sections outperformed conventional soft asphalt. CMA is validated as an eco-friendly, durable option. |

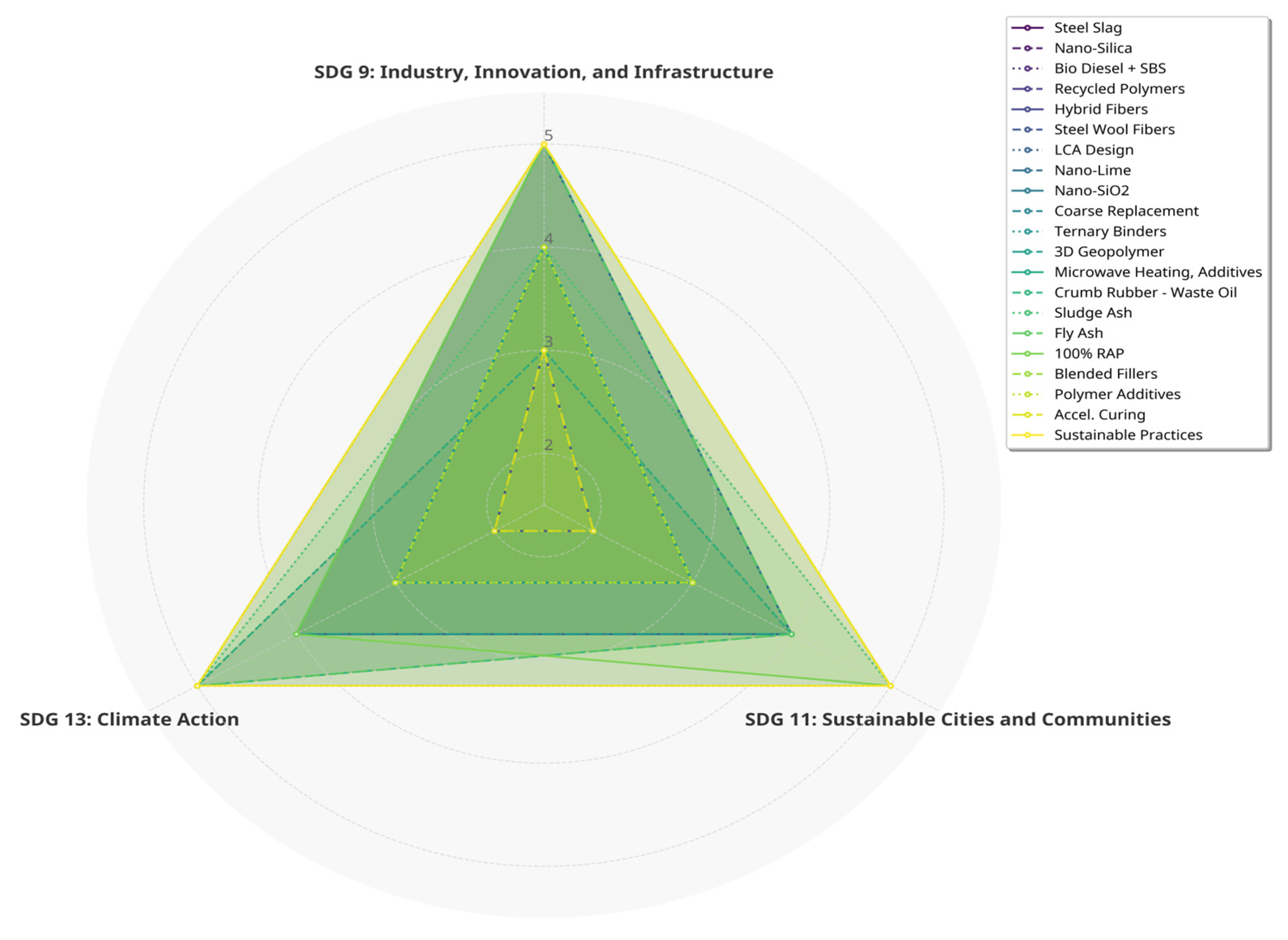

8. Environmental and Economic Impact of CMA

- SDG 11: CMA reduces reliance on virgin resources by incorporating RAP, WSA, and steel slag, thereby reducing landfill disposal and extending pavement life. For instance, using 100% RAP improves fatigue life by 49% and reduces permanent deformation. Steel slag provides a self-healing mechanism, enabling strength recovery of 74%, thus reducing future maintenance [150,151].

- SDG 9: Advanced materials stabilized by nano-silica, ternary PRBs, and 3D-printable geopolymers promote the mechanical properties of CMA as a basis for durable low-carbon infrastructure solutions.

- SDG 13: Innovations such as SBS binders with biodiesel blends, fly ashes, RHA, and microwave curing techniques reduce emissions of GHG in the process and enhance the curing and stiffness rates. That is, CKD and soda straw ash enhance the initial strength and reduce the need for heat techniques [148,150].

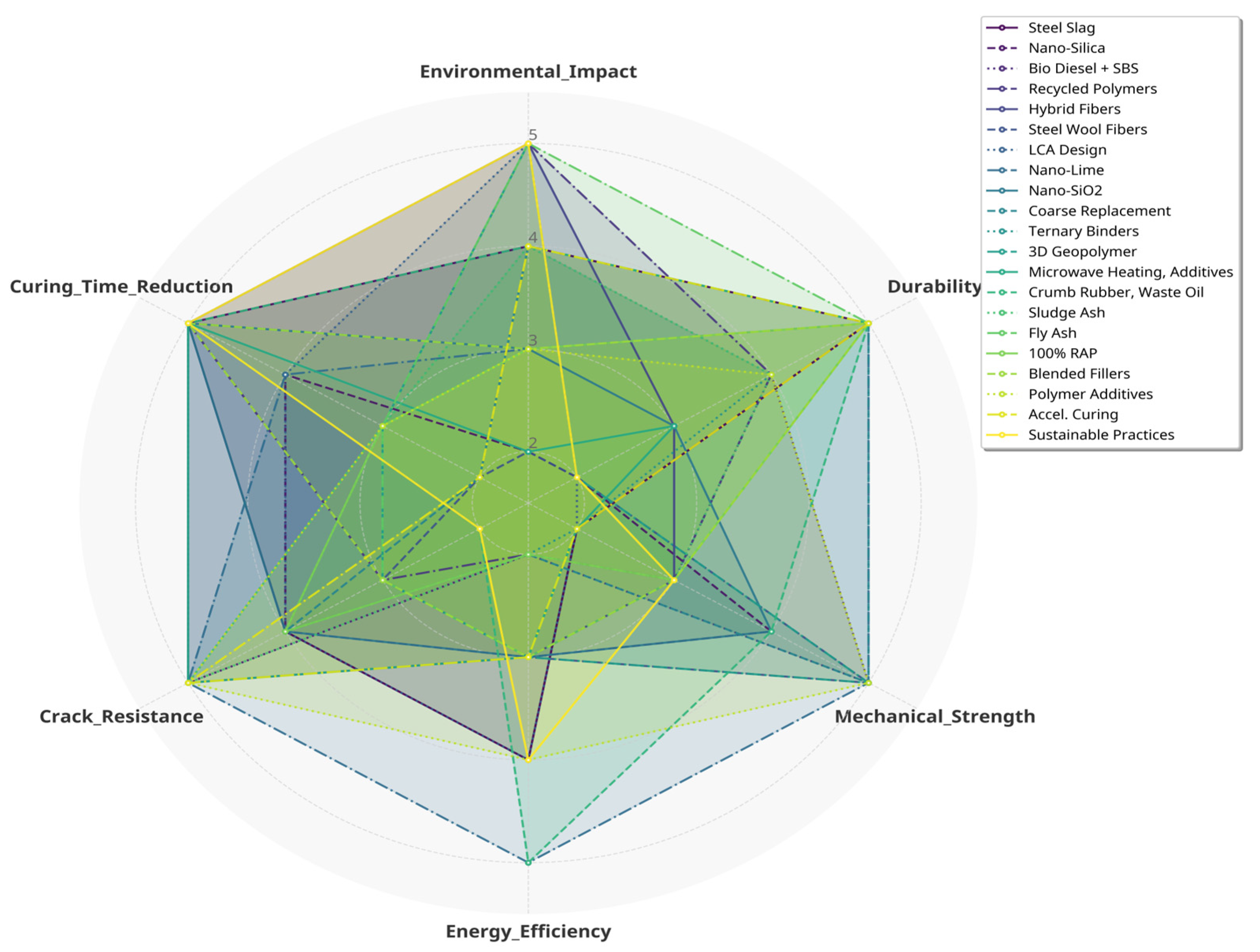

8.1. Innovations in CMA Formulation

8.1.1. Waste-Derived Fillers and Aggregates

8.1.2. Advanced Additives and Binders

8.1.3. Low-Energy and Accelerated Curing Techniques

8.1.4. Self-Healing and Durability Enhancements

8.1.5. Environmental Optimization

8.2. Sustainability Evaluation Through LCA of CMA Versus HMA

9. Performance Limitations and Field Implementation Challenges of CMA

9.1. Slow and Climate-Dependent Curing

9.2. Moisture Sensitivity and Adhesion

9.3. Long-Term Durability Uncertainties

9.4. Field Variability and Contractor Experience

- Moisture-induced stiffness scatter: Chongzheng Zhu [104] quantified the impact of stockpile moisture on 120 plant-produced CMA batches containing 35% RAP. A 1% increase in RAP free water elevated the effective binder content by 0.14% and reduced in situ air voids by 1.8%. Tensile adhesion decreased by 28% when the overnight relative humidity exceeded 85%. To mitigate this variability, contractors now enforce a 0–2% moisture limit and employ microwave sensors to adjust flux-oil dosage in real time [104].

- Temperature-driven viscosity window: A study reported by Ding et al. [7] recorded binder viscosity at 5 min intervals during 42 roadside trials under ambient temperatures ranging from 5 to 35 °C. Viscosity at 60 °C ranged from 1.1–2.0 Pa·s (CV = 18%), and the 1.6 Pa·s pot-life threshold was exceeded in 26% of loads, resulting in an average increase of 0.6 mm in Hamburg rutting depth. Consequently, a weather specification (substrate temperature ≥ 5 °C, relative humidity ≤ 85%) has been adopted to control field variability [7].

- Compaction variability at low temperature: Low temperature can result in a stiffer material (CMA), which makes the material less compactable; therefore, it has an uneven density and greater air voids. The results of these characteristics will lead to lower strength and less durability. It is necessary to adjust the appropriate mix design and optimize the compaction strategy to limit the variation that occurs with the temperature [83,133].

10. Conclusions and Future Direction

- Phase 1 (2025): Optimization of nano-additives (graphene oxide and nano-silica) to improve adhesion and moisture resistance.

- Phase 2 (2026–2027): AI-based forms predictive of the curing kinetics, the RAP–binder interaction, and the climate-dependent performance.

- Phase 3 (2028–2030): Utilization of IoT-enabled systems employing smart pavements and self-healing storms.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| CMA | Cold Mix Asphalt |

| RAP | Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement |

| MS | Marshall Stability |

| IRAC | Initial Residual Asphalt Content |

| CSS | Cationic Slow-Setting (emulsion) |

| SF | Silica Fume |

| HMA | Hot Mix Asphalt |

| TSR | Tensile Strength Ratio |

| MQ | Marshall Quotient |

| IEC | Initial Emulsion Content |

| OPC | Ordinary Portland Cement |

| FA | Fly Ash |

| WMA | Warm Mix Asphalt |

| ITS | Indirect Tensile Strength |

| LCA | Life-Cycle Assessment |

| OTLC | Optimum Total Liquid Content |

| GGBS | Ground-Granulated Blast-furnace Slag |

| CKD | Cement Kiln Dust |

References

- Tini, N.H.; Shah, M.Z.; Sultan, Z. Impact of Road Transportation Network on Socio-Economic Well-Being: An Overview of Global Perspective. Int. J. Sci. Res. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2018, 4, 282–296. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, M.; Hashemian, L.; Bayat, A.; Huculak, B. Investigation of Rutting Resistance and Moisture Damage of Cold Asphalt Mixes. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milad, A.; Babalghaith, A.M.; Al-Sabaeei, A.M.; Dulaimi, A.; Ali, A.; Reddy, S.S.; Bilema, M.; Yusoff, N.I.M. A Comparative Review of Hot and Warm Mix Asphalt Technologies from Environmental and Economic Perspectives: Towards a Sustainable Asphalt Pavement. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 14863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaya, I.N.A. Review and Recommendation of Cold Asphalt Emulsion Mixtures (CAEMs) Design. Civ. Eng. Dimens. 2007, 9, 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, S.; Wang, S.; Xia, C.; Liu, C. A New Method of Mix Design for Cold Patching Asphalt Mixture. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukhija, M.; Mayank, P.; Saboo, N. A comprehensive review of warm mix asphalt mixtures-laboratory to field. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 274, 121781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Zhao, S.; Si, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, X. Study on the micromorphologies and structural evolution in cold-mixed epoxy asphalt. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio, M.C.; Martínez, G.; Baena, L.; Moreno, F. Warm Mix Asphalt: An Overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 24, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolov, D. Asphalt Concrete Mixture Composition: Proportions of Materials. Available online: https://stroycomfort1.com/asphalt-concrete-mix-composition-components-design/ (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Al-Hashimi, Z.; Al-Busaltan, S.; Al-Abbas, B. Advancements and challenges in the use of cold mix asphalt for sustainable and cost-effective pavement solutions. E3S Web Conf. 2023, 427, 03006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swiertz, D.; Johannes, P.; Tashman, L.; Bahia, H. Evaluation of Laboratory Coating and Compaction Procedures for Cold Mix Asphalt. Asph. Paving Technol. 2012, 81, 81–102. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Geng, L.; Pan, B.; Zhou, C.; Xu, Q.; Xu, S. Cold Patching Asphalt Mixture with Cutback and 100% Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement: Interfacial Diffusion Mechanism and Performances Evaluation. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2024, 36, 04024022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List of Countries by Road Network Size. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_road_network_size (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Wu, S.; Marty, C. Three-Year Field Performance of a Low Volume Road with 100% Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement Cold Mix with Rejuvenator. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2677, 532–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press Information Bureau, India. Year End Review 2023—Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Available online: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1993425 (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/zhghs/202406/t20240614_4142419.html (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- IPWEA. A Solution for Australia’s Vast Unsealed Road Network. Available online: https://www.ipwea.org/blogs/intouch/2017/07/11/a-solution-for-australias-vast-unsealed-road-network (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Williams, B.A.; Shacat, J. Asphalt Pavement Industry Survey on Recycled Materials and Warm-Mix Asphalt Usage: 2019; National Asphalt Pavement Association: Greenbelt, MD, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Scopus. CiteScore 2023. Available online: https://www.scopus.com/sources (accessed on 12 February 2024).

- Addae, D.T.; Rahman, M.; Abed, A. State-of-the-art literature review on the mechanical, functional and long-term performance of cold mix asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 400, 132759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, F.; Ma, W.; West, R.C.; Taylor, A.J.; Zhang, Y. Structural performance and sustainability assessment of cold central-plant and in-place recycled asphalt pavements: A case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 208, 1513–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjurström, H.; Kalman, B.; Mollenhauer, K.; Winter, M.; Graziani, A.; Mignini, C.; Lo Presti, D.; Giancontieri, G.; Gaudefroy, V. Experiences from cold recycled materials used in asphalt bases: A comparison between five European countries. In Proceedings of the 7th Eurasphalt & Eurobitume Congress, Madrid, Spain, 15–17 June 2021. [Google Scholar]

- EN 13108-31:2019; Bituminous Mixtures—Material Specifications—Part 31: Asphalt Concrete with Bituminous Emulsion*. European Committee for Standardization (CEN): Brussels, Belgium, 2019.

- Grazietti, F.; Rombi, J.; Maltinti, F.; Coni, M. Comparison of the environmental benefits of cold mix asphalt and its application in pavement layers. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Athens, Greece, 3–6 July 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 231–245. [Google Scholar]

- García, A.; Lura, P.; Partl, M.N.; Jerjen, I. Influence of cement content and environmental humidity on asphalt emulsion and cement composites performance. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 1275–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Jain, S. Effect of lime and cement fillers on moisture susceptibility of cold mix asphalt. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2022, 23, 2433–2449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, G.; Gallego, J.; Miranda, L.; Marcobal, J.R. Cold asphalt mix with emulsion and 100% RAP: Compaction energy and influence of emulsion and cement content. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PG-4/88; Pliego de Prescripciones Técnicas Generales para Obras de Carreteras (General Technical Specifications for Road Works). Ministerio de Obras Públicas, Dirección General de Carreteras: Madrid, Spain, 1988.

- Redelius, P.; Östlund, J.-A.; Soenen, H. Field experience of cold mix asphalt during 15 years. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2016, 17, 223–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziyani, L.; Gaudefroy, V.; Ferber, V.; Deneele, D.; Hammoum, F. Chemical reactivity of mineral aggregates in aqueous solution: Relationship with bitumen emulsion breaking. J. Mater. Sci. 2014, 49, 2465–2476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X. A Fundamental Research on Cold Mix Asphalt Modified with Cementitious Materials. Ph.D. Thesis, ETH Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wulandari, P.; Tjandra, D. Properties evaluation of cold mix asphalt based on compaction energy and mixture gradation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1195, 012024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ouyang, J.; Meng, Y.; Han, B.; Sha, Y. Effect of Curing and Compaction on Volumetric and Mechanical Properties of Cold-Recycled Mixture with Asphalt Emulsion under Different Cement Contents. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 297, 123699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biradarpatil, A.C.; Jaya, R. Laboratory studies on cold bituminous mixes with Nanotac additive and its effect on curing time. iManag. J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 7, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dulaimi, A.; Al Busaltan, S.; Mydin, A.O.; Lu, D.; Özkılıç, Y.O.; Jaya, R.P.; Ameen, A. Innovative geopolymer-based cold asphalt emulsion mixture as eco-friendly material. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 17380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-R.; Lutif, J.S.; Bhasin, A.; Little, D.N. Evaluation of moisture damage mechanisms and effects of hydrated lime in asphalt mixtures through measurements of mixture component properties and performance testing. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2008, 20, 659–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asphalt Emulsion Manufacturers Association (AEMA). AEMA Guidelines for the Use of Asphalt Emulsions; AEMA: Annapolis, MD, USA, 1979; Available online: https://www.aema.org/ (accessed on 13 February 2024).

- Banapuram, R.R.; Andiyappan, T.; Kuna, K.K.; Reddy, M.A.; Deb, A. Influence of asphalt emulsion formulation parameters on the fluidity of cement asphalt mortar for high-speed rail tracks. Transp. Res. Rec. 2024, 03611981241257504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; Singh, B. Cold mix asphalt: An overview. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 280, 124378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3381-09; Standard Specification for Viscosity-Graded Asphalt Cement for Use in Pavement Construction. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2010.

- Miljković, M. Influence of Bitumen Emulsion and Reclaimed Asphalt on Mechanical and Pavement Design-Related Performance of Asphalt Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bochum, Germany, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ojum, C.K. The Design and Optimisation of Cold Asphalt Emulsion Mixtures. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ragheb, R.; Park, K.; Nobbmann, U.; Casola, J.; Panalytical, M. Determining the quality of asphalt emulsions by size and zeta potential. TechConnect Briefs 2019, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Meena, P.; Rongmei Naga, G.R.; Kumar, P.; Monu, K. Effect of binary blended fillers on the durability performance of recycled cold-mix asphalt. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, D.; Wang, Y.; Leng, Z.; Zhong, J. Influence of ternary blended cementitious fillers in a cold mix asphalt mixture. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres, A.; Rahmanzadeh, M.; Ayar, P. Effect of coal waste powder in HMA compared to conventional fillers: Mix mechanical properties and environmental impacts. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 91, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nynas. Nymuls CP 50—Safety Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.nynas.com/ (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- Lonbar, M.S.; Nazirizad, M. Laboratory investigation of materials type effects on the microsurfacing mixture. Civ. Eng. J. 2016, 2, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. Characterization and correlation analysis of mechanical properties and electrical resistance of asphalt emulsion cold-mix asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 119974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, J.; Shao, X.; Li, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, J.; Ruan, W.; Yu, X. Exploiting graphene oxide as a potential additive to improve the performance of cold-mixed epoxy asphalt binder. J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2023, 29, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS EN 12591:2009; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders—Specifications for Paving Grade Bitumens. British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2009.

- Fang, X.; Garcia-Hernandez, A.; Winnefeld, F.; Lura, P. Influence of cement on rheology and stability of rosin emulsified anionic bitumen emulsion. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2016, 28, 04015199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D2027/D2027M-13; Standard Specification for Cutback Asphalt (Medium-Curing Type). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

- AASHTO M 82-17; Standard Specification for Cutback Asphalt (Medium-Curing Type). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D2026/D2026M-15 (Reapproved 2021); Standard Specification for Cutback Asphalt (Slow-Curing Type). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Dong, Q.; Jahanzaib, A. Material properties of porous asphalt pavement cold patch mixtures with different solvents. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2020, 32, 06020015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgardner, G. Steps to Reduce Use of Cutback Asphalt in Pavement Maintenance and Preservation; AIEI—Asphalt, Innovate, Enlighten, Implement: Lexington, KY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Qian, J.; Liu, S.; Li, Y. Preparation and mix design of usual-temperature synthetic pitch–modified cutback asphalt. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2022, 34, 04022345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.; Naga, G.R.R.; Kumar, P. Effect of mechanical properties on the performance of cold mix asphalt with recycled aggregates incorporating filler additives. Sustainability 2023, 16, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braham, A.F.; Buttlar, W.G.; Marasteanu, M.O. Effect of binder type, aggregate, and mixture composition on fracture energy of hot-mix asphalt in cold climates. Transp. Res. Rec. 2007, 2001, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolo, S.S.; Shehu, M.; Abdulrahman, H.S.; Adamu, H.N.; Eso, O.S.; Eya, S.A.; Adeleke, S.A.; Rauf, A.T.; Ozioko, J.O.; Fetuga, I.A. Mechanical properties of cold mixed asphalt. Eng. Today 2024, 3, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardella, N.; Facchin, M.; Fabris, E.; Baldan, M.; Beghetto, V. Waste cooking oil as eco-friendly rejuvenator for reclaimed asphalt pavement. Materials 2024, 17, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M.I.; Mir, M.S.; Akhter, M. A synthesis on utilization of waste glass and fly ash in cold bitumen emulsion mixtures. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 17094–17107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deb, P.; Lakshman Singh, K. Mix design, durability and strength enhancement of cold mix asphalt: A state-of-the-art review. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2022, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMSNA (USA). Asphalt Cold Mix Manual, 3rd ed.; Part IV, Appendix F.; IMSNA: Lake Zurich, IL, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- FHWA. Cold Recycled Asphalt Mixtures; Federal Highway Administration Report, FHWA-HRT-23-056; FHWA: Glenwood, MN, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Highway Administration (FHWA). Chapter 12—98042—Recycling—Sustainability—Pavements. Available online: https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/pavement/recycling/98042/12.cfm (accessed on 2 March 2024).

- LeeBoy. Hot Mix vs. Cold Mix Asphalt: Which One Is Better for Your Road Project? LeeBoy: Lincolnton, NC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Pemberton, M. Quality of Cold-Mix Asphalt Deserves Attention; Roads and Bridges: Arlington Heights, IL, SUA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, L.; Zhai, J.; Huang, W. A review of design methods for cold in-place recycling asphalt mixtures: Design processes, key parameters, and evaluation. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 370, 133530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Transport Canada. Cold Mix Asphalt in Northern Climates; Technical Report TP 15236E; Transport Canada: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Asphalt Institute. Cold Mix Asphalt: A Practical Guide; Asphalt Institute: Lexington, KY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mashaan, N.S.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H.; Rezagholilou, A. Investigating the engineering properties of asphalt binder modified with waste plastic polymer. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2021, 12, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rkaby, A.H.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. Directional-dependence in the mechanical characteristics of sand: A review. Int. J. Geotech. Eng. 2016, 10, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keramatikerman, M.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. An investigation into effect of sawdust treatment on permeability and compressibility of soil–bentonite slurry cut-off wall. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegenizadeh, A.; Keramatikerman, M.; Nikraz, H. Liquefaction resistance of fibre-reinforced low-plasticity silt. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2018, 104, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. Investigation on strength of fiber-reinforced clay. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 261, 957–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. Composite soil: Fiber inclusion and strength. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 308, 1646–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javilla, B.; Fang, H.; Mo, L.; Shu, B.; Wu, S. Test evaluation of rutting performance indicators of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polaczyk, P.; Ma, Y.; Xiao, R.; Hu, W.; Jiang, X.; Huang, B. Characterization of aggregate interlocking in HMA by mechanistic performance tests. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2021, 22 (Suppl. S1), S498–S513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegenizadeh, A.; Tufilli, A.; Arumdani, I.S.; Budihardjo, M.A.; Dadras, E.; Nikraz, H. Mechanical properties of cold mix asphalt (CMA) mixed with recycled asphalt pavement. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slabonski, P.; Stankiewicz, B.; Beben, D. Influence of a rejuvenator on homogenization of an asphalt mixture with increased content of reclaimed asphalt pavement in lowered technological temperatures. Materials 2021, 14, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.S.; Chandrappa, A.K.; Sahoo, U.C. Design and performance of cold mix asphalt—A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 315, 125687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugener, M.; Partl, M.N.; Morant, M. Cold asphalt recycling with 100% reclaimed asphalt pavement and vegetable oil-based rejuvenators. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2014, 15, 239–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SABITA. The Design and Use of Emulsion-Treated Bases: Manual 21; Southern African Bitumen Association: Roggebaai, South Africa, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Busaltan, S. Investigating filler characteristics in upgrading cold bituminous emulsion mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Eng. Asph. Technol. 2014, 15, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Merzah, S.; Al-Busaltan, S.; Nageim, H.A. Characterizing cold bituminous emulsion mixtures comprised of palm leaf ash. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2019, 31, 04019069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A. Cold Mix Design in North America; Akzo Nobel: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dash, S.S. Effect of Mix Parameters on Performance and Design of Cold Mix Asphalt. Master’s Thesis, National Institutes of Technology, Odisha, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kekwick, S. Best Practice: Bitumen-Emulsion and Foamed Bitumen Materials Laboratory Processing. In Proceedings of the 24th Southern African Transport Conference, Pretoria, South Africa, 11–13 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kishore Kumar, C.; Amar Kumar, D.; Amaranatha Reddy, M.; Sudhakar Reddy, K. Investigation of cold-in-place recycled mixes in India. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2008, 9, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanaya, I.; Zoorob, S.; Forth, J. A laboratory study on cold-mix, cold-lay emulsion mixtures. Proc. Inst. Civ. Eng.–Transp. 2009, 162, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, J.; Ni, F.; Yang, M.; Li, J. An experimental study on fatigue properties of emulsion and foam cold recycled mixes. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2151–2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, P.; Ransinchung, G.; Kumar, P. A Comparative Study on Life Cycle Analysis of Cold Mix and Foamed Mix Asphalt. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2024, 1326, 012093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczyński, P.; Šrámek, J.; Mazurek, G. The influence of recycled materials on cold mix with foamed bitumen properties. Materials 2023, 16, 1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technical Guideline. Bitumen Stabilised Materials: A Guideline for the Design and Construction of Bitumen Emulsion and Foamed Bitumen Stabilised Material; Asphalt Academy: Pretoria, South Africa, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Road Transport and Highways. Specifications for Road and Bridge Works; Indian Roads Congress: New Delhi, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- IRC: SP-100; Use of Cold Mix Technology in Construction and Maintenance of Roads Using Bitumen Emulsion. Indian Roads Congress: New Delhi, India, 2014.

- AASHTO PP 80-20; Standard Practice for Emulsified Asphalt Content of Cold Recycled Mixture Designs. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2021.

- Ling, C.; Bahia, H.U. Development of a volumetric mix design protocol for dense-graded cold mix asphalt. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2018, 144, 04018039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.M.; Ahmed, T.M.; Ahmed, T.Y. Developing novel cold bitumen emulsion mixes by adding geopolymer. Salud Cienc. Y Tecnol. Ser. Conf. 2024, 3, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hdabi, A.; Al Nageim, H.; Seton, L. Performance of gap graded cold asphalt containing cement-treated filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 69, 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warid, M.; Hainin, M.; Yaacob, H.; Aziz, M.; Idham, M. Thin cold-mix stone mastic asphalt pavement overlay for roads and highways. Mater. Res. Innov. 2014, 18 (Suppl. S6), S6-303–S6-306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Li, J. Microstructure and road performance of emulsified asphalt cold recycled mixture containing waste additives and/or cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 448, 138199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassar, A.I.; Mohammed, M.K.; Thom, N.; Parry, T. Mechanical, durability and microstructure properties of cold asphalt emulsion mixtures with different types of filler. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 114, 352–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Xu, Z.; Qin, X.; Liao, M. Fiber-reinforcing effect in the mechanical and road performance of cement–emulsified asphalt mixtures. Materials 2021, 14, 2779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangita, M.P.S.; Yadav, A.; Pandey, Y.; Tare, V. Comparative study of emulsion-based half warm mix and cold mix for construction of SDBC and DBM. Int. J. Sci. Res. Dev. 2015, 3, 2933–3935. [Google Scholar]

- Pouliot, N.; Marchand, J.; Pigeon, M. Hydration mechanisms, microstructure, and mechanical properties of mortars prepared with mixed binder cement slurry–asphalt emulsion. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2003, 15, 54–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Sha, A. Microhardness of interface between cement asphalt emulsion mastics and aggregates. Mater. Struct. 2010, 43, 453–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.A.; Young, D.A. Evaluation of Type C fly ash in cold in-place recycling. Transp. Res. Rec. 1997, 1583, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, R.; Santucci, L.; Coyne, L. Performance characteristics of cement-modified asphalt emulsion mixes. In Proceedings of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists, Houston, TX, USA, 12–14 February 1973; Volume 42. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Jumaili, M.A.; Issmael, O.D. Sustainability of cold recycled mixture with high reclaimed asphalt pavement percentages. Appl. Res. J. 2016, 2, 344–352. [Google Scholar]

- Mushtaq, F.; Huang, Z.; Shah, S.A.R.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, Y.; Azab, M.; Hussain, S.; Anwar, M.K. Performance optimization approach of polymer-modified asphalt mixtures with PET and PE wastes: A safety study for utilizing eco-friendly circular economy–based SDGs concepts. Polymers 2022, 14, 2493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaimi, A.; Shanbara, H.K.; Al-Rifaie, A. The mechanical evaluation of cold asphalt emulsion mixtures using a new cementitious material comprising ground-granulated blast-furnace slag and a calcium carbide residue. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 250, 118808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Tan, Y.; Zhou, S. Multiscale test research on interfacial adhesion property of cold mix asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 68, 769–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, S.S.; Panda, M. Effect of aggregate gradation on cold bituminous mix performance. Adv. Civ. Eng. Mater. 2015, 4, 155–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, F.L.; Kandhal, P.S.; Brown, E.R.; Lee, D.-Y.; Kennedy, T.W. HMA Materials, Mixture Design, and Construction; National Asphalt Paving Association Education Foundation: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; p. 603. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, K.E.; Brown, S.; Pooley, G. The design of aggregate gradings for asphalt base courses. In Proceedings of the Association of Asphalt Paving Technologists, San Antonio, TX, USA, 11–13 February 1985; Volume 54. [Google Scholar]

- Vavrik, W.R.; Pine, W.J.; Bailey, R. Method for gradation selection in hot-mix asphalt mixture design. In Transportation Research E-Circular; TRB, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Number E-C044. [Google Scholar]

- Deb, P.; Singh, K.L. Accelerated curing potential of cold mix asphalt using silica fume and hydrated lime as filler. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2057976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Kumar, B.; Gupta, A. Laboratory evaluation on recycling waste industrial glass powder as mineral filler in HMA. In Proceedings of the Civil Engineering Conference—Innovation for Sustainability, Hamirpur, India, 28 October–1 November 2016; pp. 9–10. [Google Scholar]

- Modarres, A.; Alinia Bengar, P. Investigating the indirect tensile stiffness, toughness and fatigue life of HMA containing copper slag powder. Int. J. Pavement Eng. 2019, 20, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocci, E. Use of ladle furnace slag as filler in hot asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 161, 156–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, C.; Hanz, A.; Bahia, H. Measuring moisture susceptibility of cold mix asphalt with a modified boiling test based on digital imaging. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 391–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perca Callomamani, L.A.; Hashemian, L.; Sha, K. Laboratory investigation of the performance of fiber-modified asphalt mixes in cold regions. Transp. Res. Rec. 2020, 2674, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kafaji, M.; Al-Busaltan, S.; Kadhim, M.A.; Dulaimi, A.; Saghafi, B.; Al Hawesah, H. Investigating the impact of polymer and Portland cement on the crack resistance of half-warm bituminous emulsion mixtures. Sustainability 2023, 15, 15256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, B.d.S.; Da Silva, W.R.; de Lima, D.C.; Minete, E. Engineering properties of fiber reinforced cold asphalt mixes. J. Environ. Eng. 2003, 129, 952–955. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrotti, G.; Pasquini, E.; Canestrari, F. Experimental characterization of high-performance fiber-reinforced cold mix asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 57, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanbara, H.K.; Ruddock, F.; Atherton, W. Stresses and strains distribution of a developed cold bituminous emulsion mixture using finite element analysis. In Science and Technology Behind Nanoemulsions; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; Volume 9. [Google Scholar]

- Amal, R.; Narendra, J.; Sivakumar, M.; Anjaneyulu, M. Performance evaluation of cold bituminous mix reinforced with coir fibre. In AIJR Proceedings, Proceedings of the International Web Conference in Civil Engineering for a Sustainable Planet, Kollam, India, 5–6 March 2021; AIJR: Utraula, India, 2021; pp. 559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, G.S.; Pitanga, H.N.; da Silva, T.O.; e Almeida, D.C.; Lunz, K.B. Effect of geosynthetic reinforcement insertion on mechanical properties of hot and cold asphalt mixtures. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulaimi, A.; Al-Busaltan, S.; Kadhim, M.A.; Al-Khafaji, R.; Sadique, M.; Al Nageim, H.; Ibrahem, R.K.; Awrejcewicz, J.; Pawłowski, W.; Mahdi, J.M. A sustainable cold mix asphalt mixture comprising paper sludge ash and cement kiln dust. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedla, T.A.; Singh, D.; Showkat, B. Effects of air voids on comprehensive laboratory performance of cold mix containing recycled asphalt pavement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 368, 130416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Yao, H.; Yue, J.; Hu, S.; Liu, J.; Xu, M.; Chen, S. Compaction characteristics of cold recycled mixtures with asphalt emulsion and their influencing factors. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 575802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials. R-35: Standard Practice for Evaluating Transportation Resilience Guide; AASHTO: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Shijith, P.; Ashik, A.K.; Abhishek, V.K.; Snesha, N.; Revathi, A.K.; Swathi, N.; Arathi, A.; Priyanka, T. A case study on the performance of cold in-place recycled pavement in Kerala. In International Conference on Transportation System Engineering and Management; Springer: Singapore, 2024; pp. 393–404. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, D. Developments in Bitumen Emulsion Mixtures for Roads. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Chelelgo, K.; Gariy, Z.C.A.; Shitote, S.M. Modeling of fatigue-strength development in cold-emulsion asphalt mixtures using maturity method. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.; Lancaster, I.M.; McKay, D. Emulsion cold mix asphalt in the UK: A decade of site and laboratory experience. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. 2019, 6, 359–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suda, J.; Valentin, J.; Žák, J. Cold bituminous emulsion mixtures—Laboratory mix design, trial section job site and monitoring. In Proceedings of the 6th Eurasphalt & Eurobitume Congress, Prague, Czech, 1–3 June 2016; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Cheng, P.; Wang, Z.; Abdukadir, A.; Pei, Z.; Yu, W.; Fan, L.; Feng, D. Laboratory and field performance evaluation of cold-mix asphalt mixture with solvent-based liquid asphalt in winter pavement maintenance. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2025, 37, 04024531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmot, S.; Teh, S.Y.; Abu Haris, R.E.; Ayob, M.A.; Ramzi, M.R.; Kamal, D.D.M.; Atan, A. Field performance of bitumen emulsion Cold Central Plant Recycling (CCPR) mixture with same-day and delayed overlay compared with traditional rehabilitation procedures. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2022, 17, e01365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, D.; Yin, L.; Malburg, L.; You, Z. Laboratory evaluation and field demonstration of cold in-place recycling asphalt mixture in Michigan low-volume road. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e02923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, D.; Bowers, B.F.; Vargas-Nordcbeck, A.; Lynn, T. Pavement recycling in cold climates: Laboratory and field performance of the MnROAD cold recycling and full depth reclamation experiment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, B.F.; Powell, R.B. Use of a hot-mix asphalt plant to produce a cold central plant recycled mix: Production method and performance. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappat, M.; Bilal, J. The Environmental Road of the Future: Life Cycle Analysis, Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions; Colas Group: Morristown, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, W.-K. Assessment of Carbon Reduction Benefits of Concrete Products in Civil Engineering—A Case Study of Roads and Building Projects. Master’s Thesis, National Central University, Taiwan, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.-K.; Ho, M.-C.; Lin, J.-D.; Chiou, Y.-S.; Lu, C.-L. Road surface cold-mixed cold-laid recycled carbon-reduced pavement material research. HBRC J. 2024, 20, 785–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokesh, K.; Densley-Tingley, D.; Marsden, G. Measuring Road Infrastructure Carbon: A “Critical” in Transport’s Journey to Net-Zero. DecarboN8 Research Network. 2022. Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/id/eprint/197543/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- United Nations. Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, H. A review of sustainability in hot asphalt production: Greenhouse gas emissions and energy consumption. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 10246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nageim, H.; Al-Khuzaie, A.; Seton, L.; Croft, J.; Drake, J. Wastewater sludge ash in the production of a novel cold mix asphalt (CMA): Durability, aging and toxicity characteristics. Kufa J. Eng. 2024, 15, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buczyński, P.; Krasowski, J. Optimisation and composition of the recycled cold mix with a high content of waste materials. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshvar, D.; Motamed, A.; Imaninasab, R. Improving Fracture and Moisture Resistance of Cold Mix Asphalt (CMA) Using Crumb Rubber and Cement. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2022, 23, 527–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dovom, H.A.; Kargari, A.; Moghaddam, A.M.; Kazemi, M.; Fini, E.H. Self-healing cold mix asphalt containing steel slag: A sustainable approach to cleaner production. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 482, 144170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Wahed, T.; Dulaimi, A.; Shanbara, H.K.; Al Nageim, H. The impact of cement kiln dust and cement on cold mix asphalt characteristics at different climate. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Yu, X.; Dong, F.; Ji, Z.; Wang, J. Using silane coupling agent coating on acidic aggregate surfaces to enhance the adhesion between asphalt and aggregate: A molecular dynamics simulation. Materials 2020, 13, 5580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Sivakumar, M.; Anjaneyulu, M. Investigation of curing and strength characteristics of cold-mix asphalt with rice husk ash–activated fillers. J. Transp. Eng. Part B Pavements 2022, 148, 04022056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, F.; Alshubrumi, F.; Almoshaogeh, M.; Haider, H.; Elragi, A.; Elkholy, S. Sustainability evaluation of cold in-place recycling and HMA pavements: A case of Qassim, Saudi Arabia. Coatings 2022, 12, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. Research and Application of Green Environmental Cold Mix Asphalt Mixtures for Township Roads; Dean & Francis Academia Publishing: Oxfordshire, UK, 2024; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, Y.; Wen, X.; Liu, S.; Lv, S.; He, L. Stochastic analysis for comparing life cycle carbon emissions of hot and cold mix asphalt pavement systems. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2025, 212, 107881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaro, N.S.A.; Sutanto, M.H.; Baloo, L.; Habib, N.Z.; Usman, A.; Yousafzai, A.K.; Ahmad, A.; Birniwa, A.H.; Jagaba, A.H.; Noor, A. A comprehensive overview of the utilization of recycled waste materials and technologies in asphalt pavements: Towards environmental and sustainable low-carbon roads. Processes 2023, 11, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Zhou, J.; Wu, D.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, L. Preparation and performance evaluation of rubber powder-polyurethane composite modified cold patch asphalt and cold patch asphalt mixture. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 369, 130473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abaza, O.A.; Dahms, D. Performance evaluation of studded tire ruts for asphalt mix designs in a cold region environment. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | AI MS-14 [65,72] | TG [96] | AASHTO PP 80-20 [99] | IRC: SP:100 [97,98] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blend Classification | Well-graded or gap-graded aggregates | Traffic-dependent categories: BSM1 (>6 MESA), BSM2 (<6 MESA), BSM3 (<1 MESA). | Requires 100% crushing RAP to meet gradation targets; permits ≤15% virgin aggregates to correct deficiencies. | BM and SDBC mixes are specified. |

| IRAC/IEC Calculation | Empirical formulas with critical sieve sizes at 2.36 mm and 0.075 mm. | Not specified | Not specified | An empirical approach using 2.36 mm and 0.090 mm sieves as breakpoints. |

| Coating Requirements | ≥50% aggregate coating mandated. | Not specified | An aggregate coating of ≥90% is mandated, assessed visually during mixing. | Visual inspection for adequate coating (no quantitative threshold). |

| OTLC Determination | Derived from the moisture content yielding maximum dry density. | Optimum moisture content is established using modified AASHTO compaction. | Optimum water content determined at maximum dry density (modified Proctor). OTLC = Optimum water + foamed asphalt content. | Not specified |

| Variation in RAC | Maintains a constant OTLC | Not specified | Test ≥3 emulsion contents (e.g., 3.0%, 3.5%, 4.0%); select optimum via stability/voids. | Maintains the same OPWC, leading to a gradual increase in TLC. |

| Curing Process | Dry stability: 24 h mold (25 °C) → 24 h oven (40 °C) → 24 h mold (25 °C). Soaked: 48 h water immersion | Level 1: 72 h at 40 °C (unsealed). Levels 2–3: 26 h at 30 °C → sealed → 48 h at 40 °C | 72 h at 40 °C → 24 h at 25 °C (simulates 14-day field curing). | Air-dry loose mix (1–2 h) → oven-dry (40 °C, 2 h) → compact → 24 h mold (25 °C) → 72 h oven (40 °C). |

| Determination of ORAC | Maximizes soaked stability and dry density while meeting other criteria | Levels 1–2: indirect tensile strength (ITS) tests. Level 3: triaxial test results | Not Specified | It mainly focuses on maximum dry stability and density; soaked stability is not considered. |

| Moisture Damage | Stability values that have been retained are evaluated. | TSR values alongside moisture sensitivity tests are conducted | Stability values that have been retained are evaluated. | Analysis of retained ITS values. |

| Reference | Type of Emulsion/Asphalt | Blend Overview | Dosage | Curing | Key Results | Summary |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chongzheng Zhu [104] | CSS | RAP 84% + 12% virgin agg. + 4% mineral powder + 1.5% cement, FA, RH | 1.5% cement, FA, RH | 2 days @ 60 °C | ITS: 0.75–1.04 MPa; Stability: 1800–4200 passes/mm; TSR: 75–85% | FA maximized CRM tensile and low-temp performance; 0.75% FA + cement cut CO2 by ~50%. |

| Wenting Yang [33] | CSS | RAP 70% + limestone 30%; 4.4% added water | 4% emulsion; 0–2% cement | 2 days @ 60 °C, 3 days @ 20 °C + 2 days @ 60 °C | ITS: 0.74–0.94 MPa; AV: 10.3–11.7%; CSED: 2.03–2.77 kJ/m3 | Staged curing prioritizes cement hydration, producing a denser, stiffer matrix. |

| Li Yawen [49] | CSS | Aggregates + filler + cement (0–6%) | 8% emulsion + 0–6% cement | 28 days @ 23 °C, 55% RH | ITS: 540–1250 kPa; Stability: 6.8–13.1 kN; AV: 9–10% | 2% cement provides ≥80% of 28-day strength in 7 days; higher cement accelerates early strength. |

| Nassar et al. [105] | CE (C60B5) | Cold asphalt + OPC, FA, GGBS, Silica Fume | OPC: 8.8–43.9 g; additives 20–40% | - | ITSR: 80–105%; Stiffness: 282 MPa; AV: 8.5–9.8% | GGBS + SF reduces porosity and improves stiffness and durability. |

| Dulaimi [114] | CSS (C50B4) | 6% total filler: 4% GGBS + 2% CCR | 4% GGBS + 2% CCR | 3, 7, 56 days @ 20 °C | ITS: 1540–2510 MPa; AV: 8.9–9.2%; Rut: 3.2–3.5 mm; ITSR: 86–88% | 4% GGBS + 2% CCR outperforms limestone mixes, matches hot mix stiffness in 3 days. |

| Zhu Siyue [106] | SBS- Modified Emulsified Asphalt | CEAM + Cement + Fibers | 3% OPC, 0–0.2% fiber | 3–7 days @ 20 °C | ITS: 0.42–0.91 MPa; Flexural: 0.60–1.18 MPa; ITSM: 1050–2240 MPa; Rut: 2.5–4.8 mm; ITSR: 72–90% | 0.2% fiber + 3% OPC increases ITS, fatigue life, and reduces rut depth. |

| Chegeniza-deh [81] | CSS | 100% RAP + BE | 2–4% BE | 1–12 weeks @ 20 °C, soaked 24 h @ 25 °C | ITS: 230–561 kPa; RM: 771–2510 MPa; Rut: 9–13.6 mm; Fatigue: 102–153 k cycles | 4% CSS + 100% RAP optimizes stiffness, strength, fatigue, and rutting. |

| Rezaei [2] | Cutback/Emulsified/ Polymer-Modified | 9 cold mixes: DG + OG | Binder 2.4–6.7% | 24 h @ 25 °C, oven-cured 18 h @ 135 °C | MS: DG: 6.8–19 kN; OG: 3.4–10.1 kN; ITS: 370–1568 kPa; TSR: 0.64–1.06 | DG cold mixes with a low dust-to-binder ratio yield higher stability and the lowest rutting/moisture damage. |

| Mix ID | Cement (%) | Stage | Time (d) | Marshall Stability (kN) | ITS (kPa) | ITSM (MPa) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C0 | 0 | I | 0–3 | 2.0 | 250 | 520 (36%) |

| II | 3–14 | 4.8 | 600 | 1360 (95%) | ||

| III | 14–28 | 5.7 | 676 | 1435 | ||

| C2 | 2 | I | 0–3 | 5.0 | 370 | 3500 (52%) |

| II | 3–14 | 9.2 | 720 | 6300 (93%) | ||

| III | 14–28 | 10.5 | 807 | 6764 | ||

| C4 | 4 | I | 0–3 | 7.5 | 680 | 6300 (46%) |

| II | 3–14 | 15.2 | 1220 | 13,400 (97%) | ||

| III | 14–28 | 16.0 | 1331 | 13,805 | ||

| C6 | 6 | I | 0–3 | 13.3 | 730 | 8200 (46%) |

| II | 3–14 | 18.7 | 1420 | 16,100 (91%) | ||

| III | 14–28 | 21.0 | 1577 | 17,657 | ||

| HMA | — | — | — | — | — | 2705 |

| Material | Key Finding | Performance Gain | Sustainability Gain | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wastewater sludge ash (WSA) | Replaces limestone filler; passes UK/EN leachability limits | Increase moisture resistance and durability | Eliminates calcination CO2 | [152] |

| RAP | 50% RAP > control stability; 100% RAP increased +49% fatigue life; decrease rut depth | Matches or exceeds virgin mix | Diverts waste; cuts virgin aggregate | [44,81] |

| Hybrid (50% RAP + 30% other recycled agg.) | Portland cement/bitumen emulsion binder achieves parity with HMA | Stable, durable mix | Reduces virgin content by ≥80% | [27,83,153] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Malik, M.D.; Chen, Y.; Mu, J.; Dong, R. Sustainable Cold Mix Asphalt: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Innovations, Circular Economy Integration, Field Performance, and Decarbonization Pathways. Materials 2025, 18, 5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235452

Malik MD, Chen Y, Mu J, Dong R. Sustainable Cold Mix Asphalt: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Innovations, Circular Economy Integration, Field Performance, and Decarbonization Pathways. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235452

Chicago/Turabian StyleMalik, Muhammad Danyal, Yongsheng Chen, Jian Mu, and Ruikun Dong. 2025. "Sustainable Cold Mix Asphalt: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Innovations, Circular Economy Integration, Field Performance, and Decarbonization Pathways" Materials 18, no. 23: 5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235452

APA StyleMalik, M. D., Chen, Y., Mu, J., & Dong, R. (2025). Sustainable Cold Mix Asphalt: A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Innovations, Circular Economy Integration, Field Performance, and Decarbonization Pathways. Materials, 18(23), 5452. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235452