Oil Effect on Improving Cracking Resistance of SBSMA and Correlations Among Performance-Related Parameters of Binders and Mixtures

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Investigate the oil effect on improving the cracking performance of SBSMA and consider the impact of oxidation aging;

- (2)

- Explore the internal relationship among cracking performance parameters of the binders;

- (3)

- Correlate the performance-related indices between the binder and mixture and identify the binder parameters that can be used to predict the mixture cracking performance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Preparation of Specimens

2.1.1. Binder Materials and Preparation of Specimens

2.1.2. Mixture Materials

2.2. Aging Method

2.3. Binder Experiments and Indices

2.3.1. Bending Beam Rheometer (BBR) Tests

2.3.2. Linear Amplitude Sweep (LAS) Tests

2.3.3. Frequency Sweep Tests and δ8967 kPa

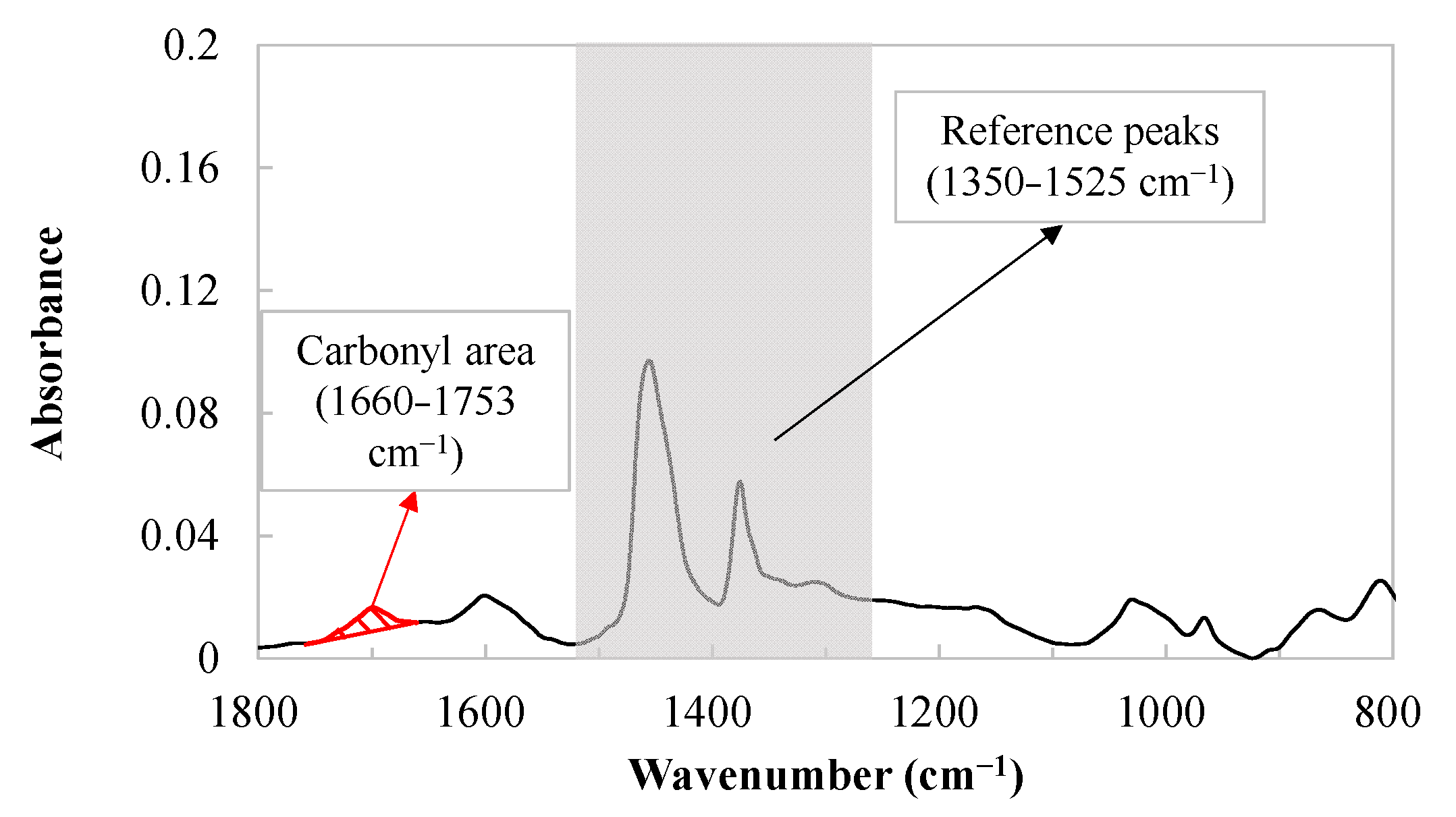

2.4. ATR-FTIR Scanning

2.5. Mixture Experiments and Indices

3. Results and Discussion

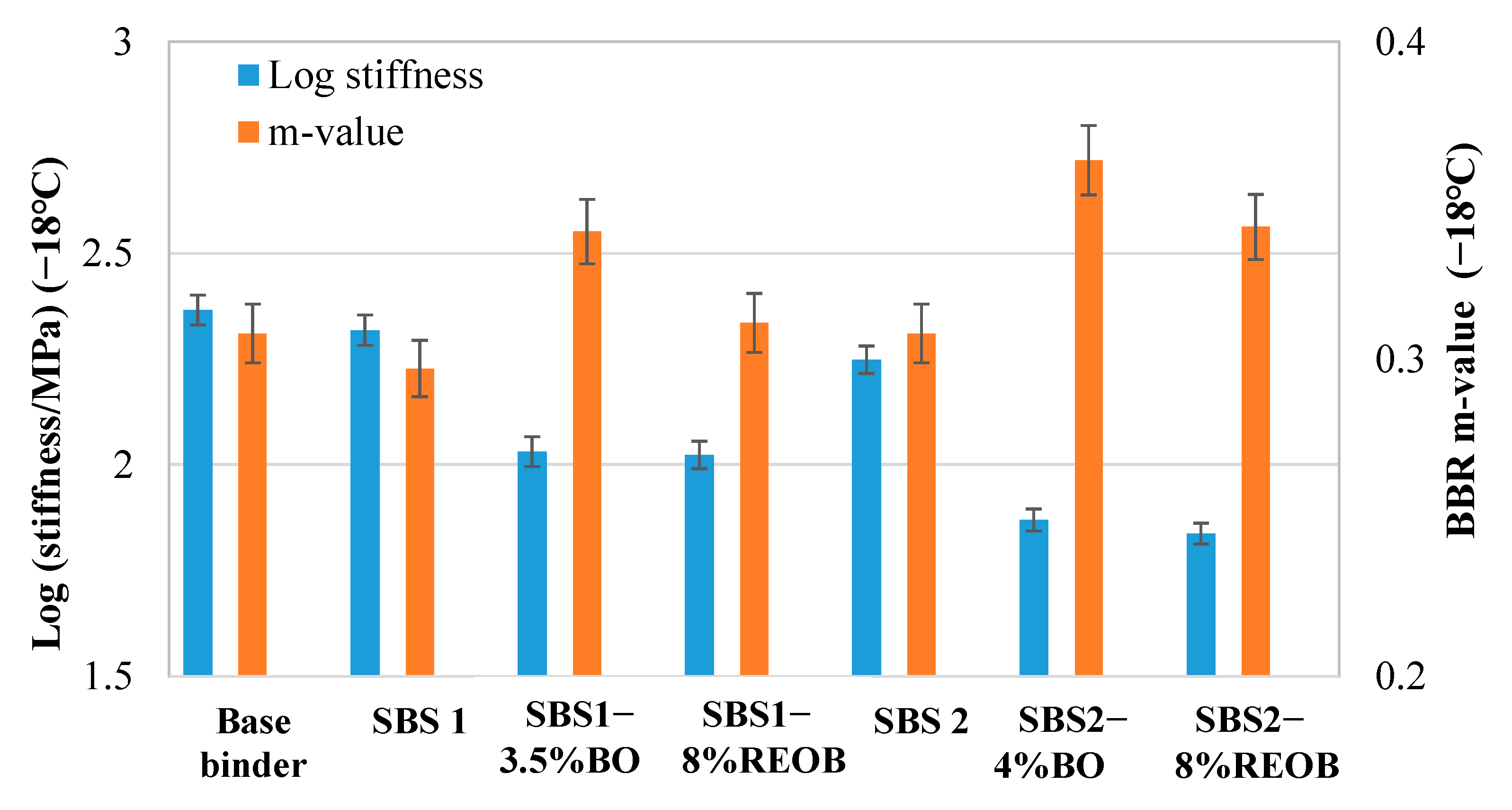

3.1. Low-Temperature Cracking Parameters from BBR Tests

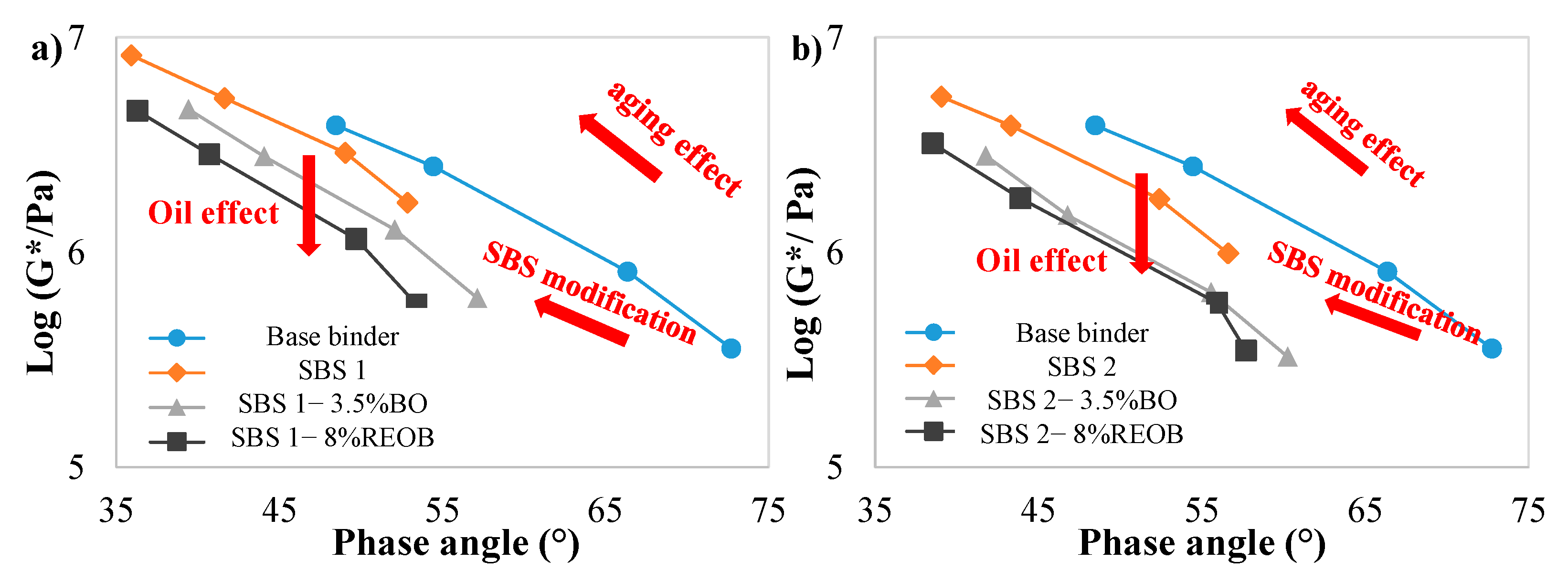

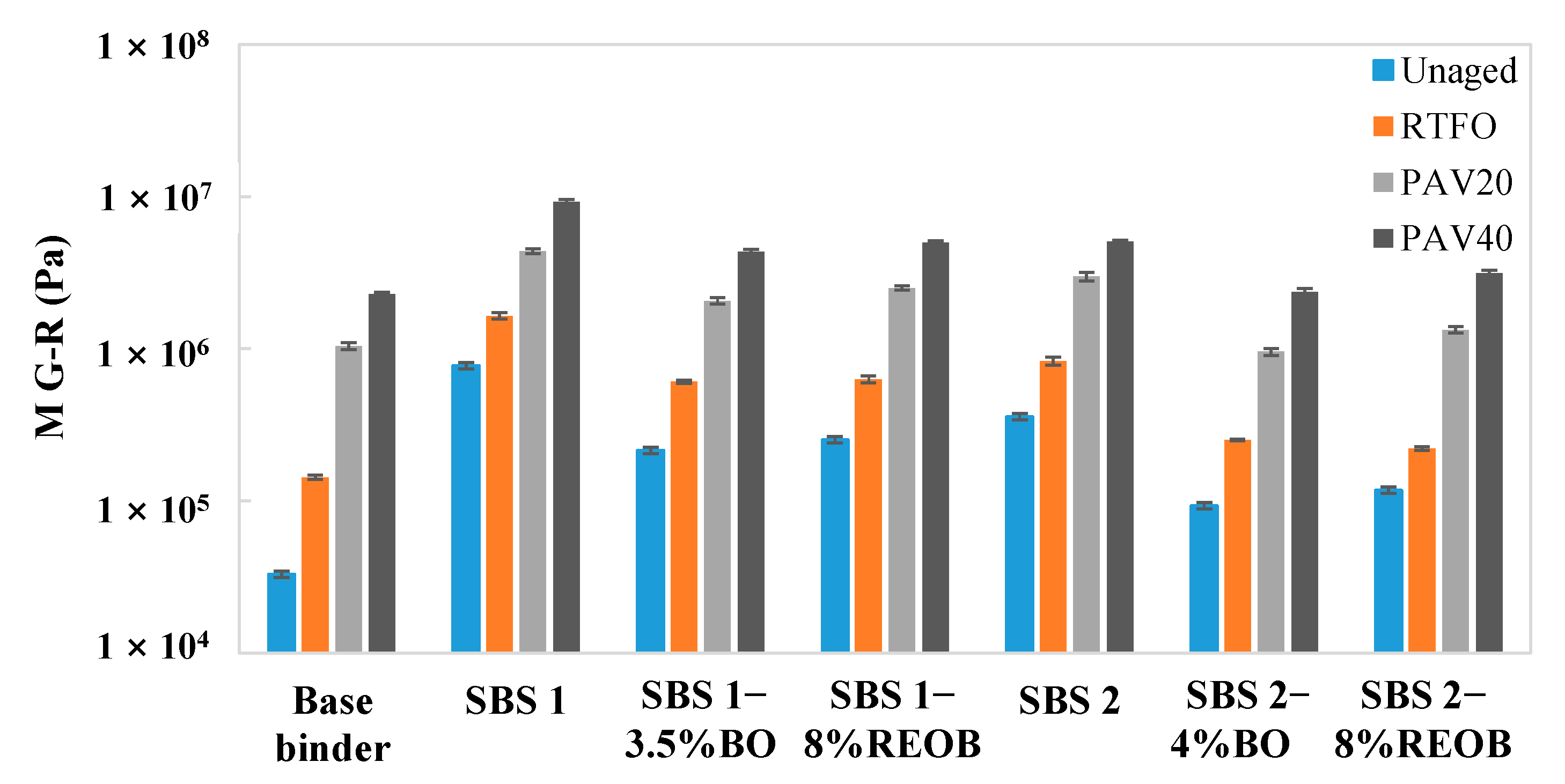

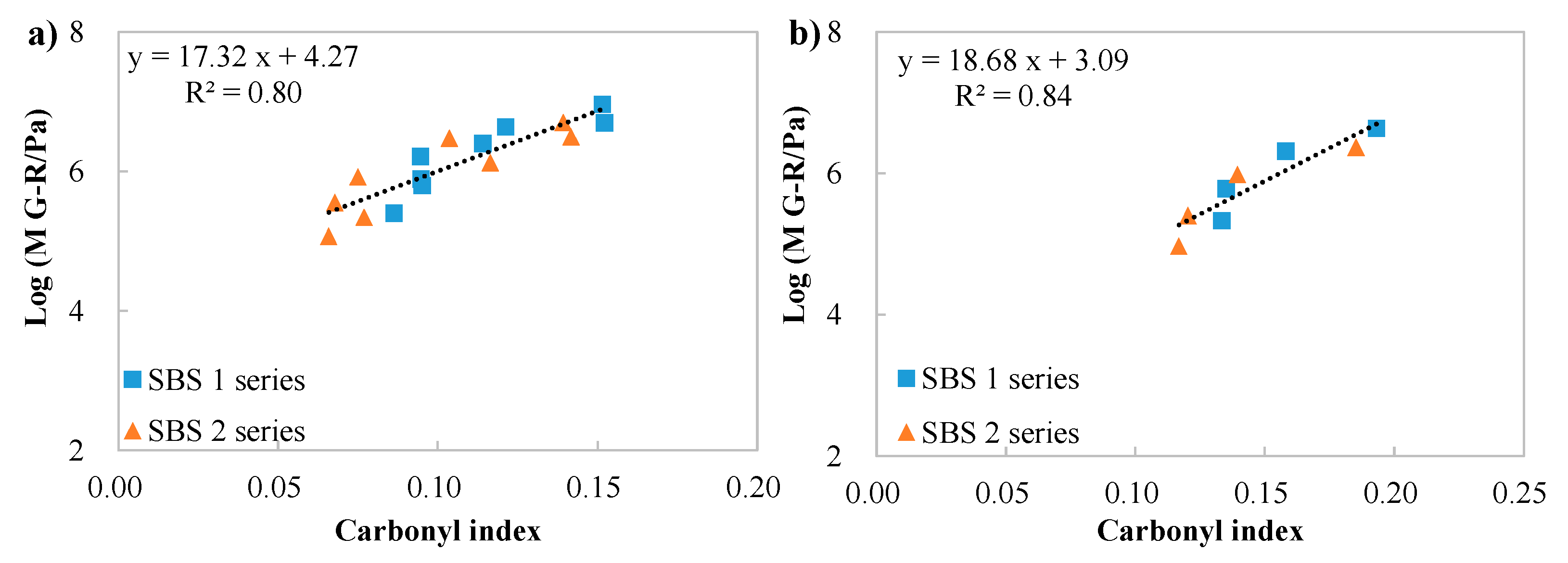

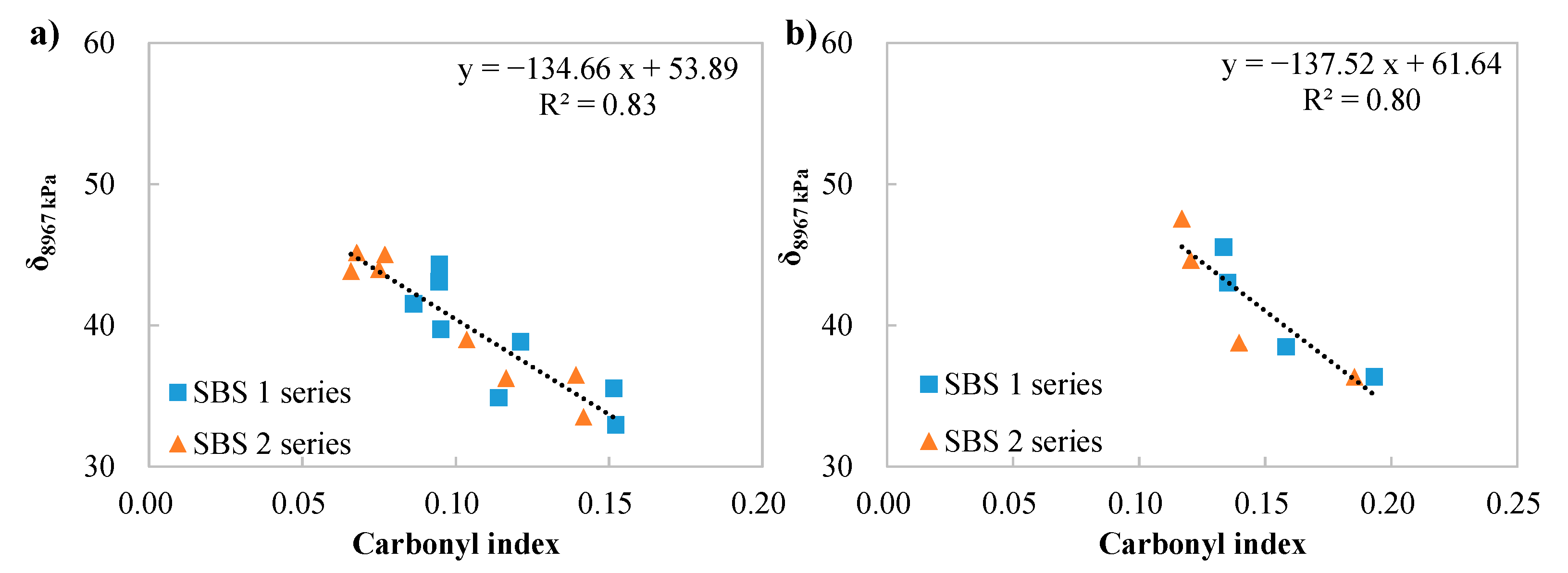

3.2. Black Diagrams and M G–R Results

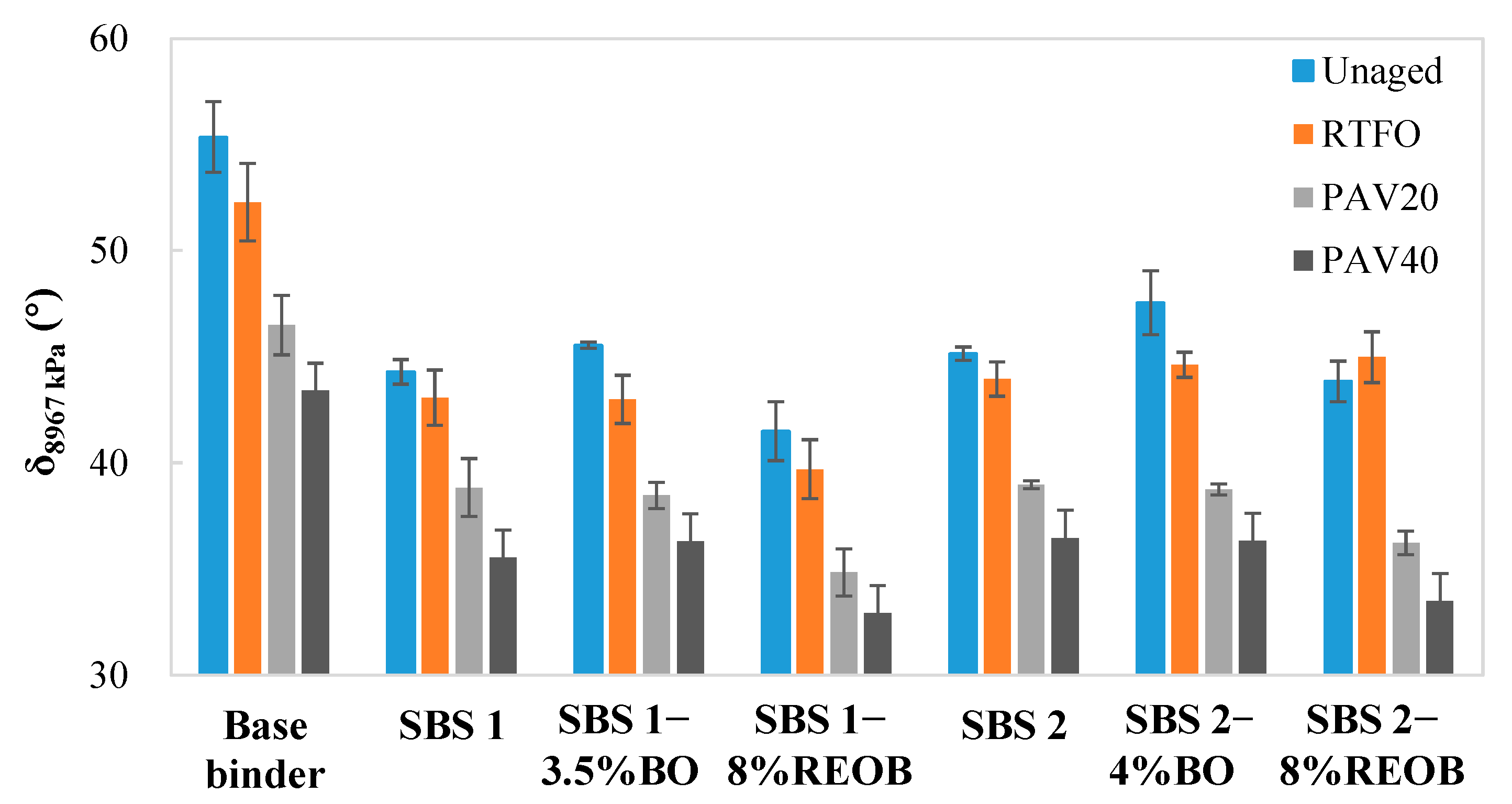

3.3. δ8967 kPa Results

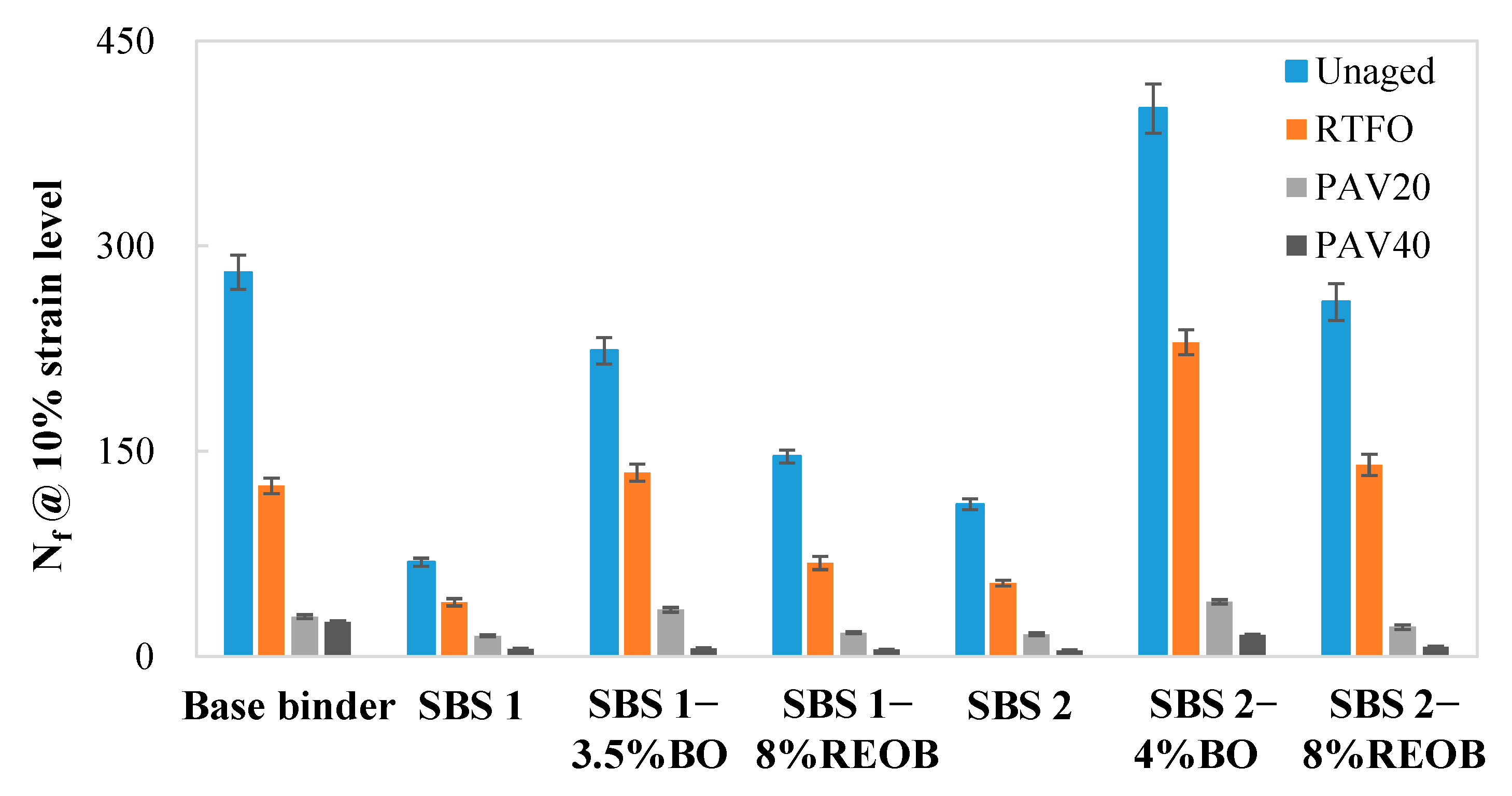

3.4. The Fatigue Life Results from LAS Tests

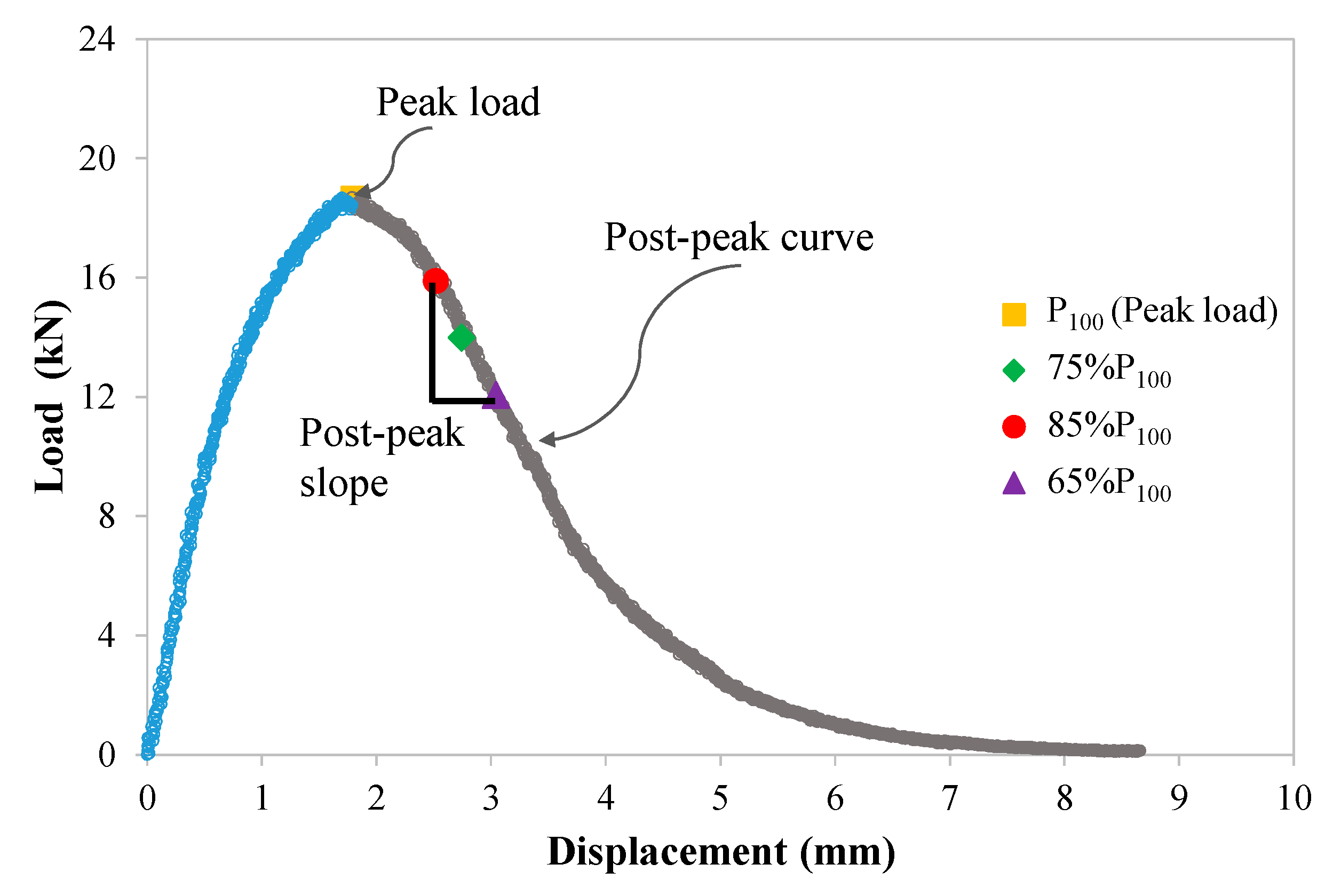

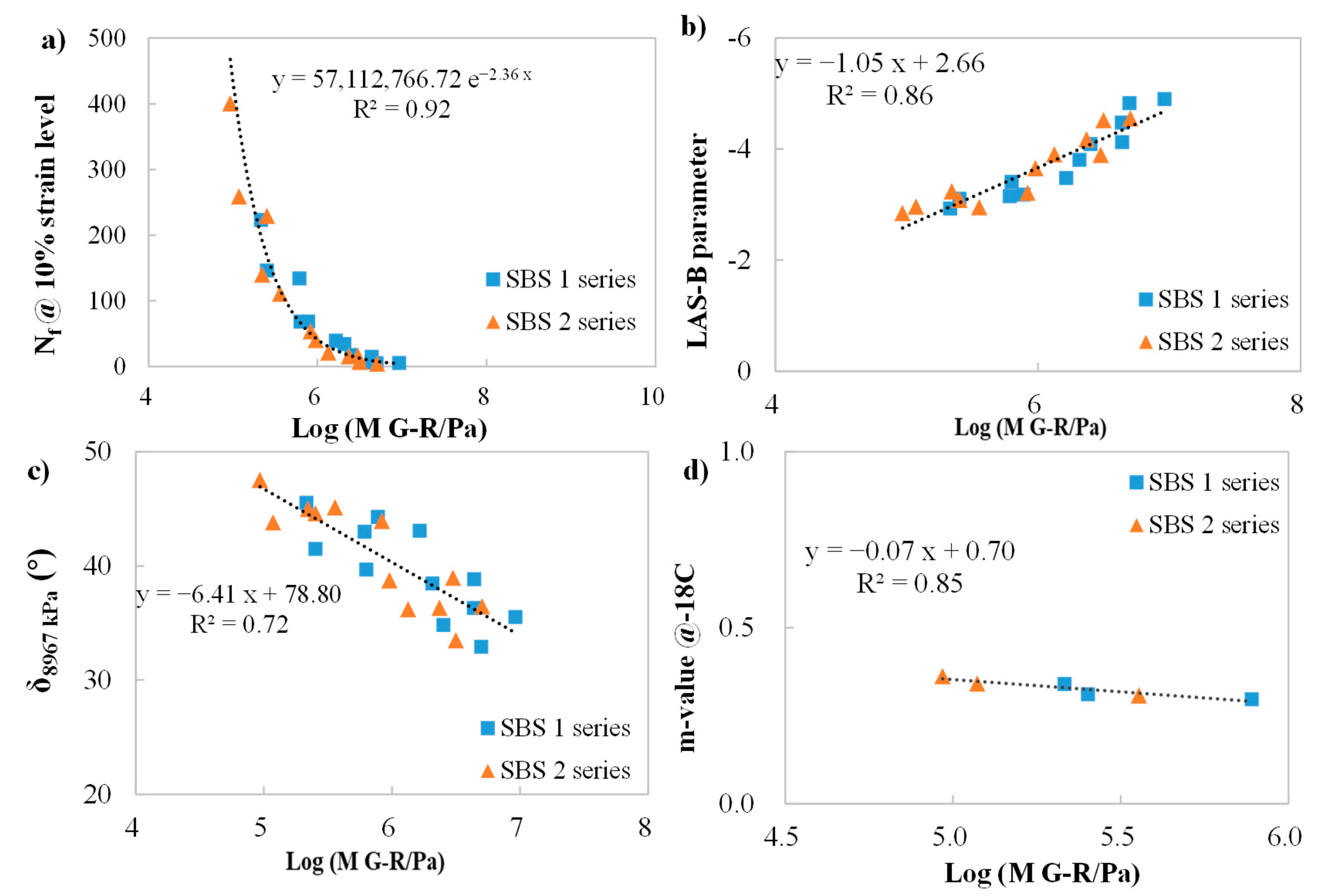

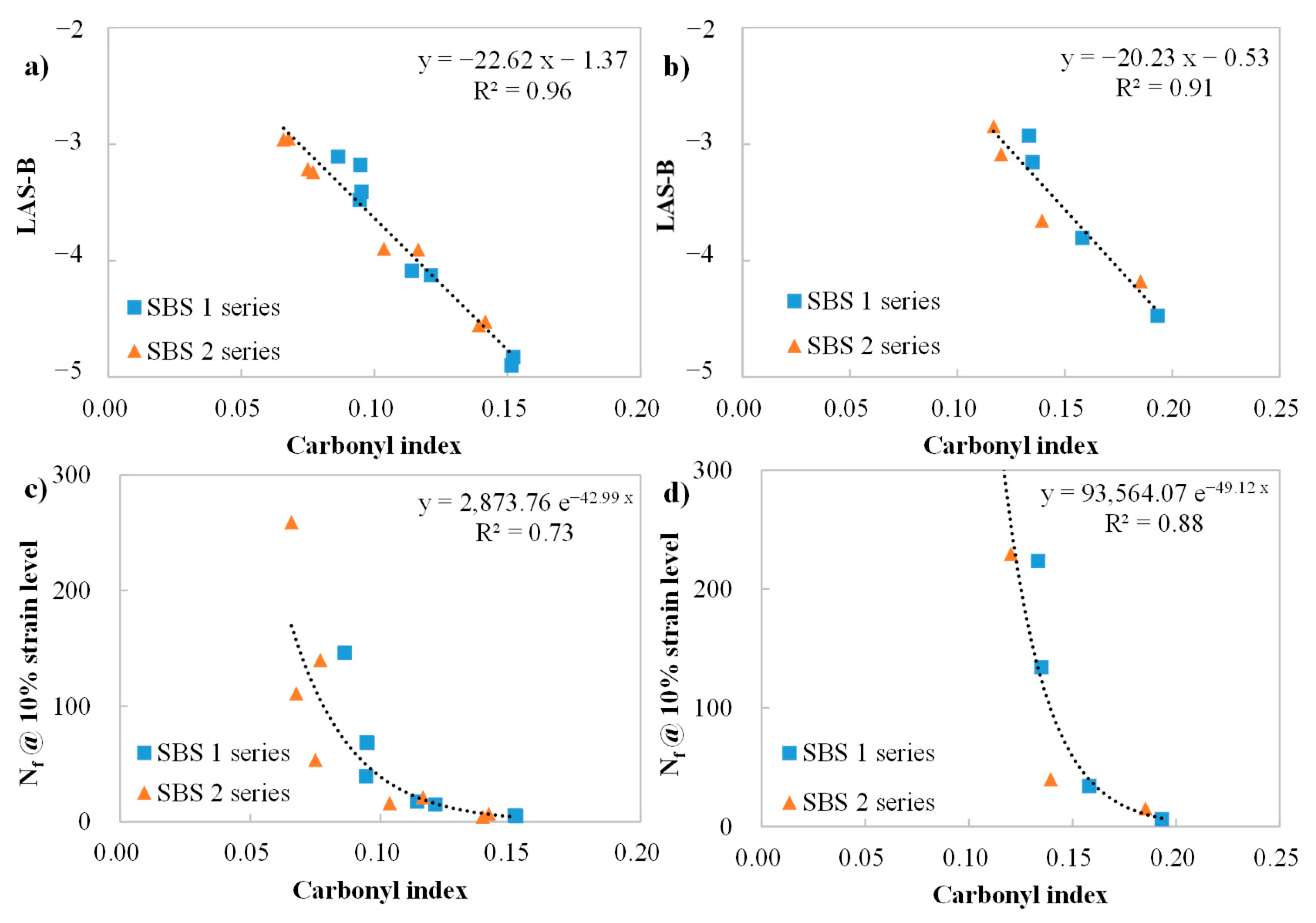

3.5. Correlating Analysis Among Cracking Performance Parameters of Binders

3.6. Correlations Between Chemical and Rheological Indices of Binders

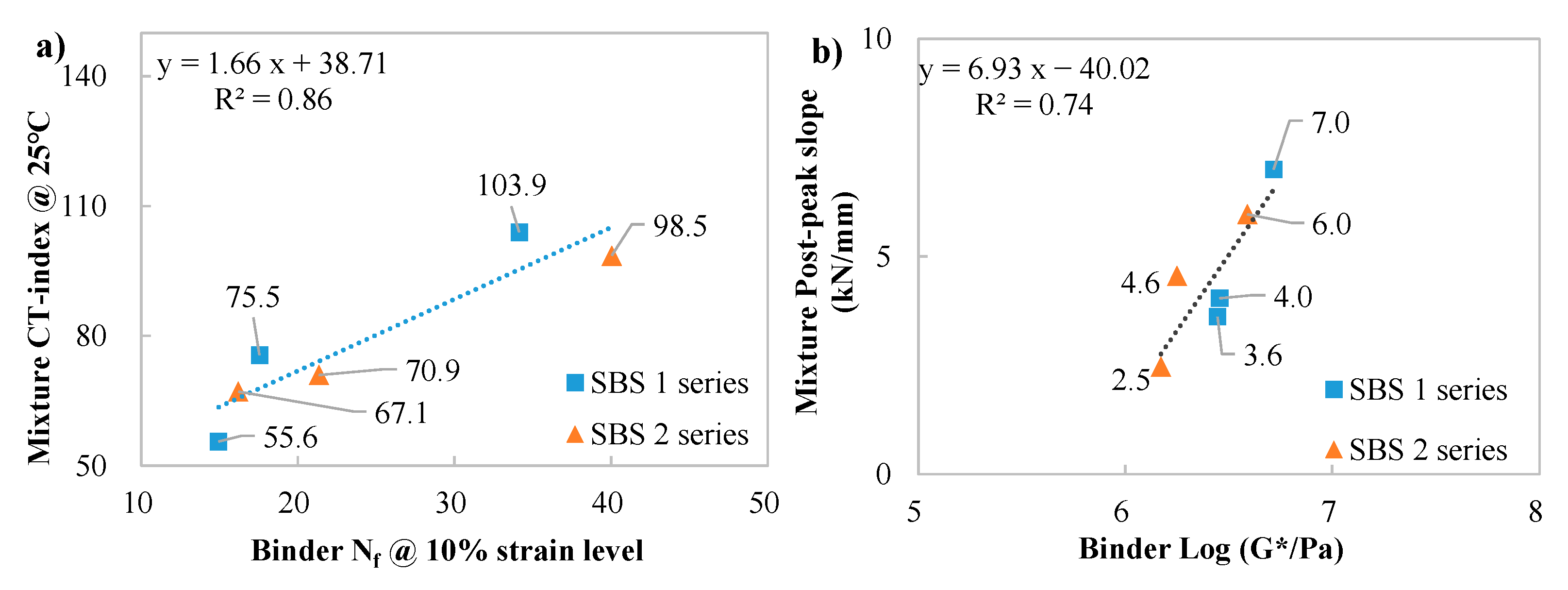

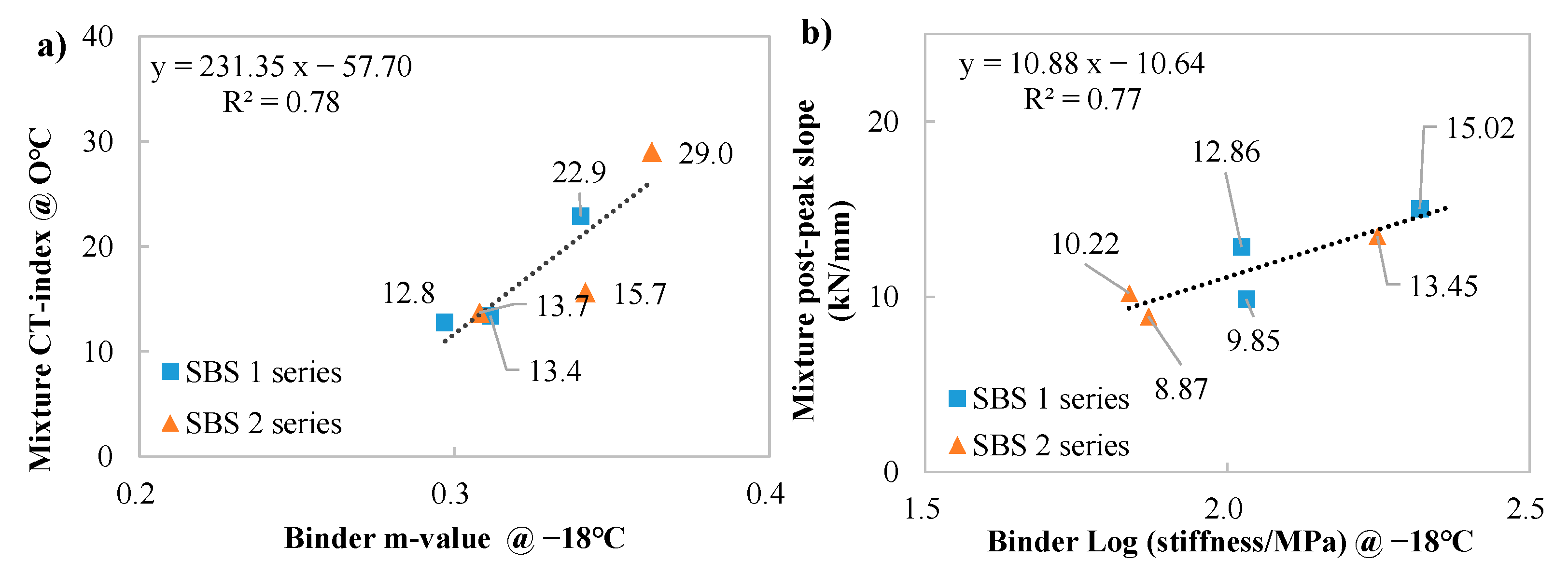

3.7. Correlating Analysis Between Mixture and Binder Indices

4. Conclusions

| Abbreviations | Definitions |

|---|---|

| SBS | Styrene–butadiene–styrene |

| SBSMA | Styrene–butadiene–styrene-modified asphalt |

| Bio-oil | Bio-based oil |

| REOB | Re-refined engine oil bottom |

| M G–R | Modified Glover–Rowe parameter |

| G* | Complex modulus |

| δ | Phase angle |

| δ8967 kPa | δ at G* = 8967 kPa |

| LAS | Linear amplitude sweep |

| Nf | Fatigue life obtained from LAS |

| IDEAL-CT | Indirect tensile asphalt cracking test |

| FTIR | Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy |

| PG | Performance grade |

| HT PG | High-temperature performance grade |

| LT PG | Low-temperature performance grade |

| VECD | Viscoelastic continuum damage |

| AC | Asphalt concrete |

| RTFO | Rolling thin film oven |

| PAV | Pressure aging vessel |

| PAV20/40 | 20/40 h PAV |

| BBR | Bending beam rheometer |

| SENB | Single edge notched beam |

| Gf | Fracture energy |

| OMI | Oil modification index |

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, M.; Geng, J.; Xia, C.; He, L.; Zhuo Liu, Z. A review of phase structure of SBS modified asphalt: Affecting factors, analytical methods, phase models and improvements. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 294, 123610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesueur, D. The colloidal structure of bitumen: Consequences on the rheology and on the mechanisms of bitumen modification. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 145, 42–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nian, T.; Sun, H.; Ge, J.; Li, P. Molecular dynamics analysis of enhancing mechanical properties of aged SBS-modified asphalt through component regulation. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 491, 142784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.; Liang, P.; Fan, W.; Qian, C.; Xin, X.; Shi, J.; Nan, G. Thermo-rheological behavior and compatibility of modified asphalt with various styrene–butadiene structures in SBS copolymers. Mater. Des. 2015, 88, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Wen, H.P.; Ullah, Z.; Ali, B.; Khan, D. Evaluation of high modulus asphalts in China, France, and USA for durable road infrastructure, a theoretical approach. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 432, 136622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Huang, W.; Lin, P.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, Q. Chemical and rheological evaluation of aging properties of high content SBS polymer modified asphalt. Fuel 2019, 252, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, G.; Gong, M.; Chen, X.; Yang, J. Internal aging indexes to characterize the aging behavior of two bio-rejuvenated asphalts. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 220, 1231–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Huang, W.; Ma, J.; Xu, J.; Lv, Q.; Lin, P. Characterizing the SBS polymer degradation within high content polymer modified asphalt using ATR-FTIR. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 233, 117708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Li, B.; Sun, D.; Yu, F.; Hu, M. Chemo-rheological and morphology evolution of polymer modified bitumens under thermal oxidative and all-weather aging. Fuel 2021, 285, 118989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Fan, W.; Xu, J.; Erkens, S. Experimental characterization of viscoelastic behaviors microstructure thermal stability of CR/SBSmodified asphalt with TOR. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 261, 120524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, N.; Luo, M.; Xue, C.; Liu, S.; Li, R.; Zhu, H.; Cheng, H. Performance evaluation and mechanism investigation of aged SBS/chemically activated rubberized asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 158, 139497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilger, A.; Swiert, D.; Bahia, H. Long-Term Aging Performance Analysis of Oil Modified Asphalt Binders. Transp. Res. Rec. 2019, 2673, 404–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Pei, J.; Cai, J.; Liu, T.; Wen, Y. Performance improvement and aging property of oil/SBS modified asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 300, 123735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiada, W.; Liu, H.; Ezzat, H.; Al-Khateeb, G.G.; Underwood, B.S.; Shanableh, A.; Samarai, M. Review of the Superpave performance grading system and recent developments in the performance-based test methods for asphalt binder characterization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 319, 126063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Adwani, D.; Bhasin, A.; Hazlett, D.; Zhou, F. Identification of asphalt binder tests for detecting variations in binder cracking performance. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 439, 137345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, S.F.; Ali, A.; Purdy, C.; Decarlo, C.; Elshaer, M.; Mehta, Y. Thermal cracking in cold regions’ asphalt mixtures prepared using high polymer modified binders and softening agents. Int. Pavement Eng. 2023, 24, 2147523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Issa, M.; Goli, A.; Revelli, V.; Ali, A.; Mehta, Y. Influence of softening agents on low and intermediate temperature cracking properties of highly polymer modified asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 490, 142404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, S.; Li, L.; Li, P.; Saboundjian, S. Low temperature cracking analysis of asphalt binders and mixtures. Cold Regions Sci. Technol. 2017, 141, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Saboundjian, S. Evaluation of cracking susceptibility of Alaskan polymer modified asphalt binders using chemical and rheological indices. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 271, 121897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Adwani, D.; Zorigtbaatar, N.; Zhou, F.; Karki, P. Assessment of binder test methods for detecting cracking susceptibility in asphalt mixtures. Int. J. Fatigue 2025, 194, 108827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahia, H.U.; Hanson, D.I.; Zeng, M.; Zhai, H.; Khatri, M.A.; Anderson, R.M. Characterization of Modified Asphalt Binders in Superpave Mix Design; National Academy Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C. Estimating Asphalt Binder Fatigue Resistance Using an Accelerated Test Method. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Swiertz, D.; Bahia, H. Use of Blended Binder Tests to Estimate Performance of Mixtures with High Reclaimed Asphalt Pavement/Recycled Asphalt Shingles Content. Transp. Res. Record. 2021, 2675, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Bahia, H.; Tan, Y. Effect of bio-based and refined waste oil modifiers on low temperature performance of asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 86, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Ding, H.; Su, T. Non-isothermal low-temperature reversible aging of commercial wax-based warm mix asphalts. Int. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriz, P.; Campbell, C.; Kucharek, A.; Varamini, S. A Simple Binder Specification Tweak to Promote Best Performers. In Proceedings of the Sixty-Fifth Annual Conference of the Canadian Technical Asphalt Association (CTAA)-Cyberspace, Kelowna, Canada, 16–19 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D1980-87; Standard Test Method for Acid Value of Fatty Acids and Polymerized Fatty Acids. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1998.

- AOCS Cc 9a-48; Official Method for Neutral Oil and Loss (Wesson Method). American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 2017.

- ASTM D1475-21; Standard Test Method for Density of Liquid Coatings, Inks, and Related Products. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D4402-15; Standard Test Method for Viscosity Determination of Asphalt at Elevated Temperatures Using a Rotational Viscometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- AASHTO R 30-22; Standard Practice for Mixture Conditioning of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA). American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials: Washington, DC, USA, 2022.

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, H.; Bahia, H. Extended aging performance of high RAP mixtures and the role of softening oils. Int. Pavement Eng. 2022, 23, 2773–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahia, H.; Sadek, H.; Rahaman, Z.M.; Lemke, Z. Field Aging and Oil Modification Study Final Report WHRP 0092-17-04; Wisconsin Department of Transportation: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Chen, H.; Wen, Y.; Xue, B.; Li, R.; Pei, J. Aging property of oil recycled asphalt binders with reclaimed asphalt materials. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04021246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Xiao, F.; Huang, W. Short-Term Aging of High-Content SBSMA. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Im, S.; Sun, L.; Scullion, T. Development of an IDEAL Cracking Test for Asphalt Mix Design and QC/QA. Asph. Paving Technol. 2017, 86, 549–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behnood, A. Application of rejuvenators to improve the rheological and mechanical properties of asphalt binders and mixtures: A review. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 231, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golalipour, A. Investigation of the Effect of Oil Modification on Critical Characteristics of Asphalt Binders. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Properties | Bio-Oil | REOB | Standard |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acid value (mg KOH/g) | 23 | 35 | ASTM D 1980–87 [27] |

| Flash point (°C) | >290 | 220 | AOCS Cc 9a-48 [28] |

| Density @ 25 °C (g/cm3) | 1.03 | 0.94 | ASTM D1475 [29] |

| Viscosity @ 60 °C (mPa·s) | 27.5 | 305 | ASTM D4402 [30] |

| SBS1 | SBS1–3.5%BO | SBS1–8%REOB | SBS2 | SBS2–4%BO | SBS2–8%REOB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Base binder | 96.9% | 93.4% | 88.9% | 95.4% | 91.4% | 87.4% |

| Dushanzi | 3.0% | 3.0% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| LG 501 | 0% | 0% | 0% | 4.5% | 4.5% | 4.5% |

| Bio-oil | 0% | 3.5% | 0% | 0% | 4.0% | 0% |

| REOB | 0% | 0% | 8.0% | 0% | 0% | 8.0% |

| Sulfur | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% |

| HT PG | 82.9 | 76.2 | 77.1 | 82.7 | 75.7 | 77.8 |

| LT PG | −27.6 | −34.3 | −30.0 | −29.2 | −34.1 | −34.1 |

| PG | 82–28 | 76–34 | 76–28 | 82–28 | 76–34 | 76–34 |

| Gradation | Upper Limit | Lower Limit | The Median | Design Mix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Passing Percent (%) | ||||

| 16 mm | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 13.2 mm | 100 | 90 | 95 | 95.2 |

| 9.5 mm | 85 | 68 | 76.5 | 72.1 |

| 4.75 mm | 68 | 38 | 53 | 42.5 |

| 2.36 mm | 50 | 24 | 37 | 27.9 |

| 1.18 mm | 38 | 15 | 26.5 | 19.1 |

| 0.6 mm | 28 | 10 | 19 | 14.1 |

| 0.3 mm | 20 | 7 | 13.5 | 10.2 |

| 0.15 mm | 15 | 5 | 10 | 8.5 |

| 0.075 mm | 8 | 4 | 6 | 6.2 |

| Binder content (%) | NA | NA | NA | 5.2 |

| Samples | OMI | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Log Stiffness (MPa/%) | m-Value (/%) | ||

| SBS1 | Bio-oil | −0.08 | 0.012 |

| REOB | −0.04 | 0.002 | |

| SBS2 | Bio-oil | −0.09 | 0.014 |

| REOB | −0.05 | 0.004 | |

| Samples | Oil Type | 25 °C | 0 °C | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT-Index | Post-Peak Slope (KN/mm) | CT-Index | Post-Peak Slope (KN/mm) | ||

| SBS1 | NA | 55.6 | 7.0 | 12.8 | 15.0 |

| Bio-oil | 103.9 | 3.6 | 22.9 | 9.9 | |

| REOB | 75.5 | 4.0 | 13.4 | 12.9 | |

| SBS2 | NA | 67.1 | 6.0 | 13.7 | 13.5 |

| Bio-oil | 98.5 | 2.5 | 29.0 | 8.9 | |

| REOB | 70.9 | 4.6 | 15.7 | 10.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gu, R.; Xu, J.; Wan, W.; Zhang, K.; Zhu, Y.; Tan, X. Oil Effect on Improving Cracking Resistance of SBSMA and Correlations Among Performance-Related Parameters of Binders and Mixtures. Materials 2025, 18, 5443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235443

Gu R, Xu J, Wan W, Zhang K, Zhu Y, Tan X. Oil Effect on Improving Cracking Resistance of SBSMA and Correlations Among Performance-Related Parameters of Binders and Mixtures. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235443

Chicago/Turabian StyleGu, Ronghua, Jing Xu, Weihua Wan, Kai Zhang, Yaoting Zhu, and Xiaoyong Tan. 2025. "Oil Effect on Improving Cracking Resistance of SBSMA and Correlations Among Performance-Related Parameters of Binders and Mixtures" Materials 18, no. 23: 5443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235443

APA StyleGu, R., Xu, J., Wan, W., Zhang, K., Zhu, Y., & Tan, X. (2025). Oil Effect on Improving Cracking Resistance of SBSMA and Correlations Among Performance-Related Parameters of Binders and Mixtures. Materials, 18(23), 5443. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235443