Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Asymmetrically Rolled Ultra-Thin Ti-6Al-4V

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Methods

2.1. Preparation of Experimental Samples

2.2. Microstructural Characterization and Mechanical Property Testing

2.3. Electrochemical Testing

2.4. ICR Testing

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructure Analysis

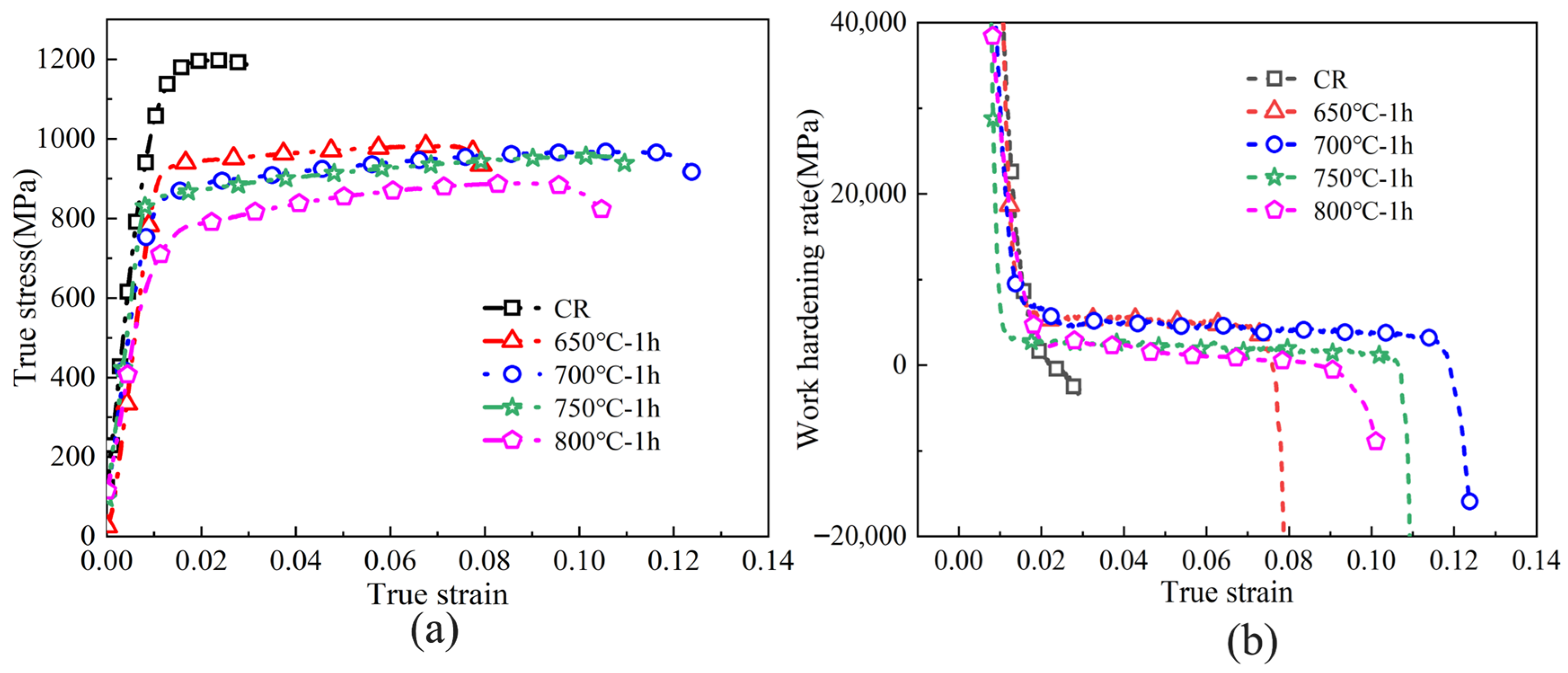

3.2. Mechanical Properties Analysis

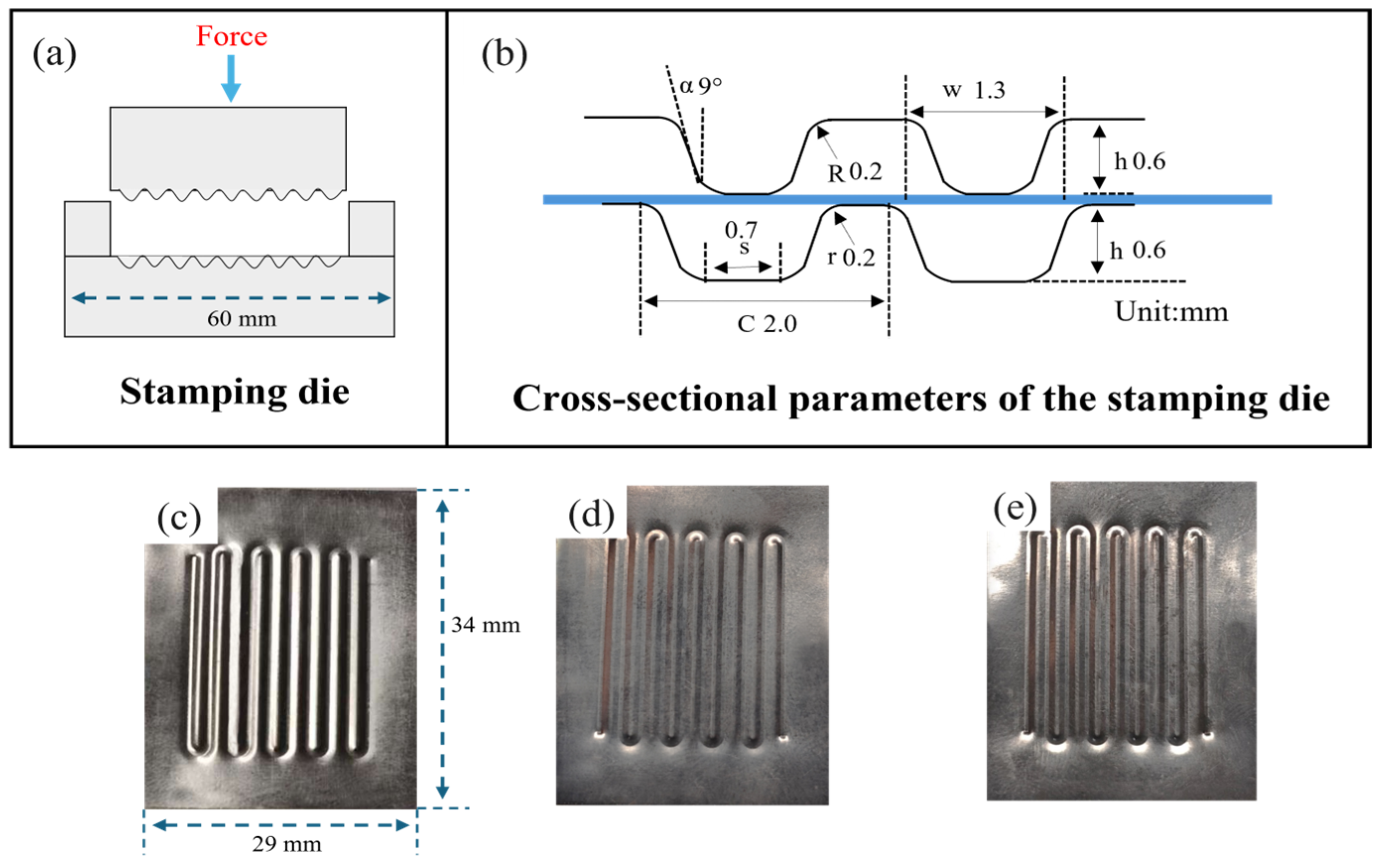

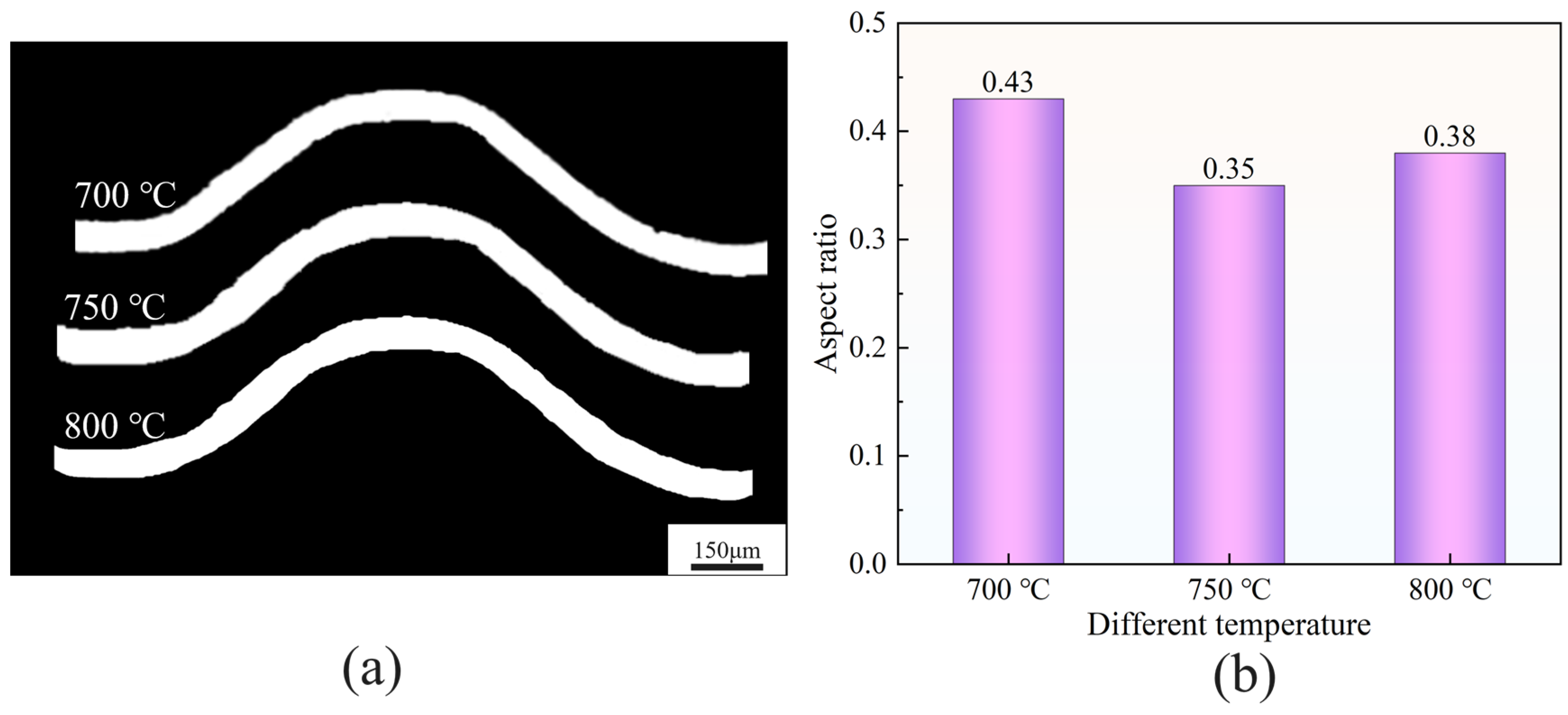

3.3. Ti-6Al-4V Bipolar Plate Forming Analysis

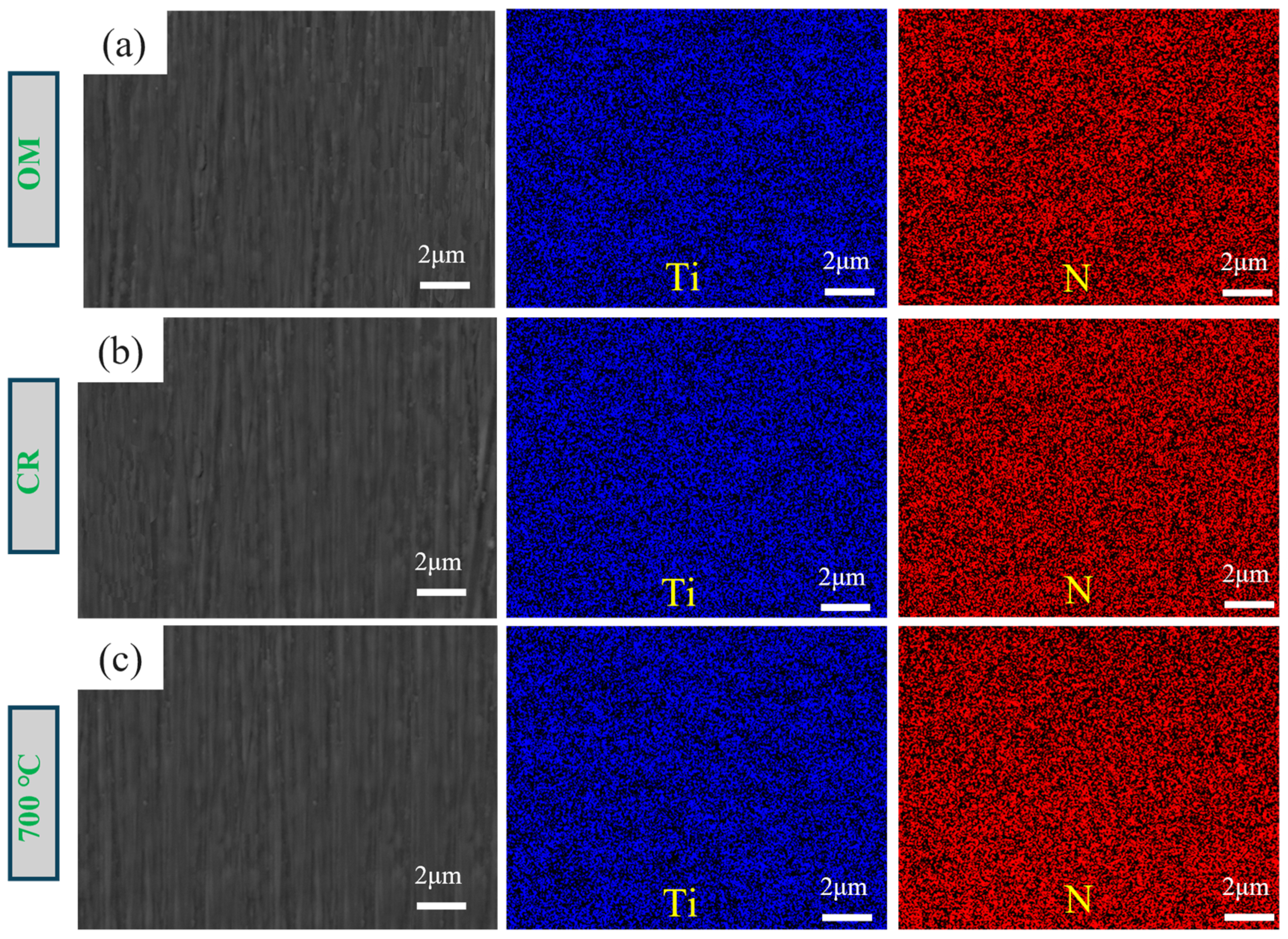

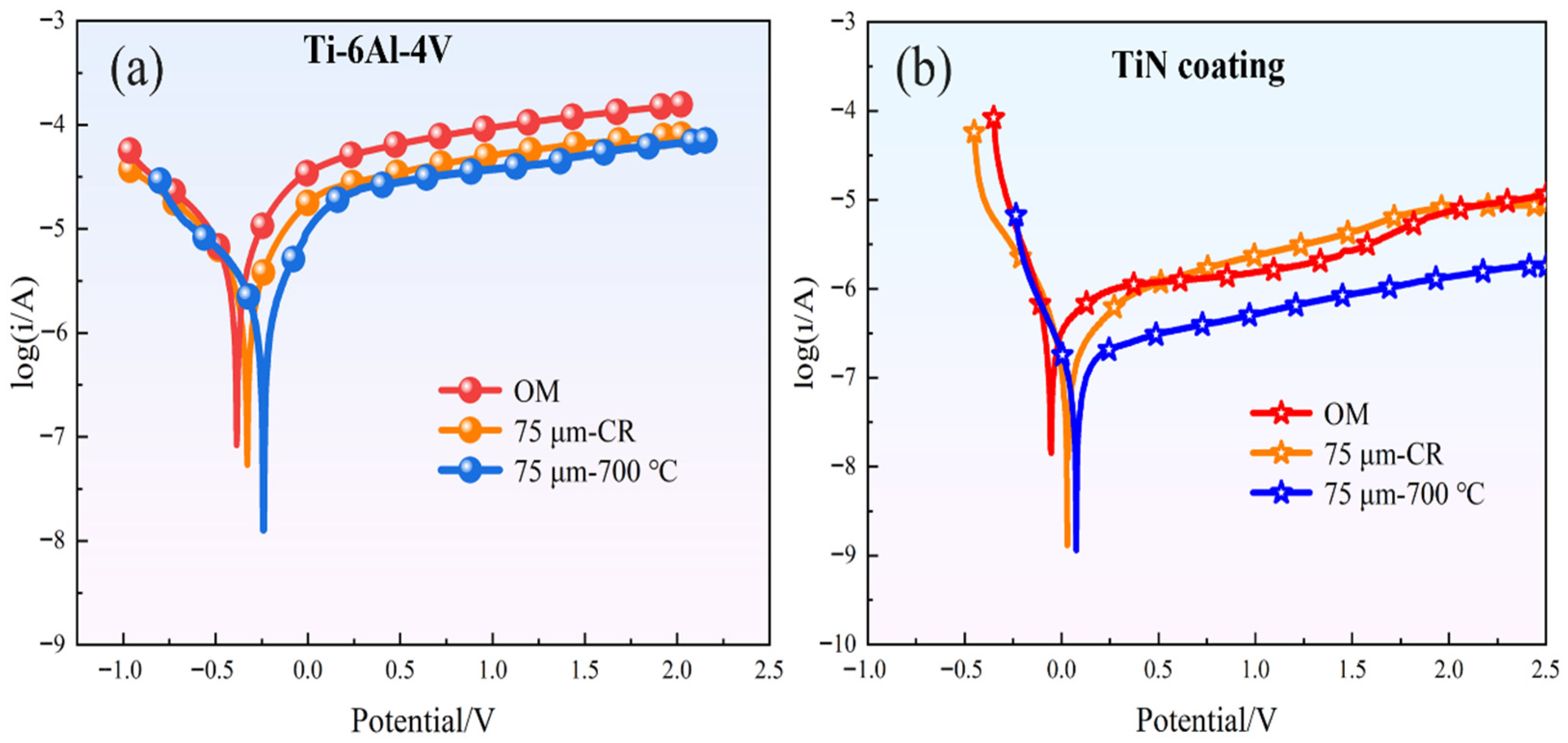

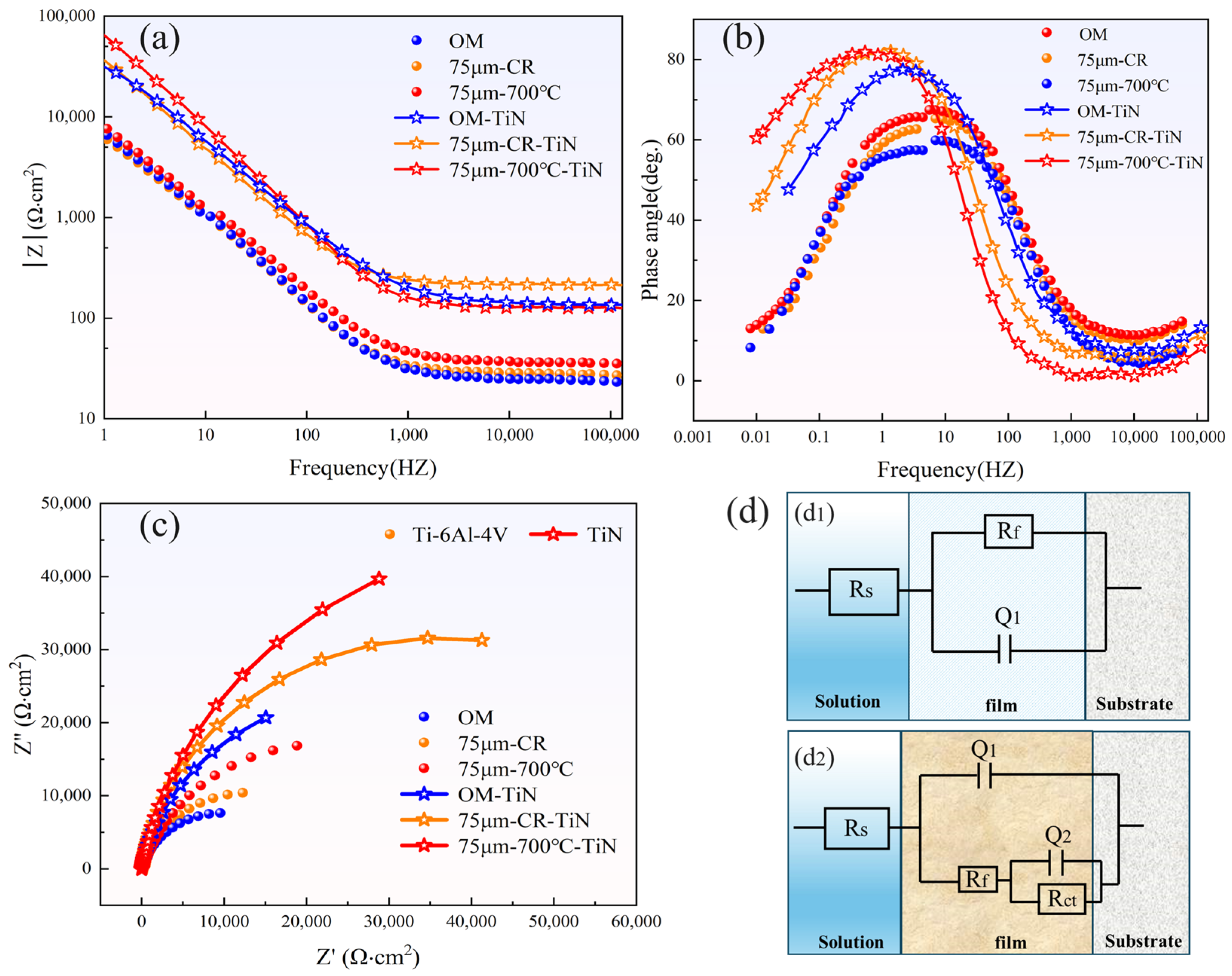

4. Electrochemical Corrosion Behavior Test

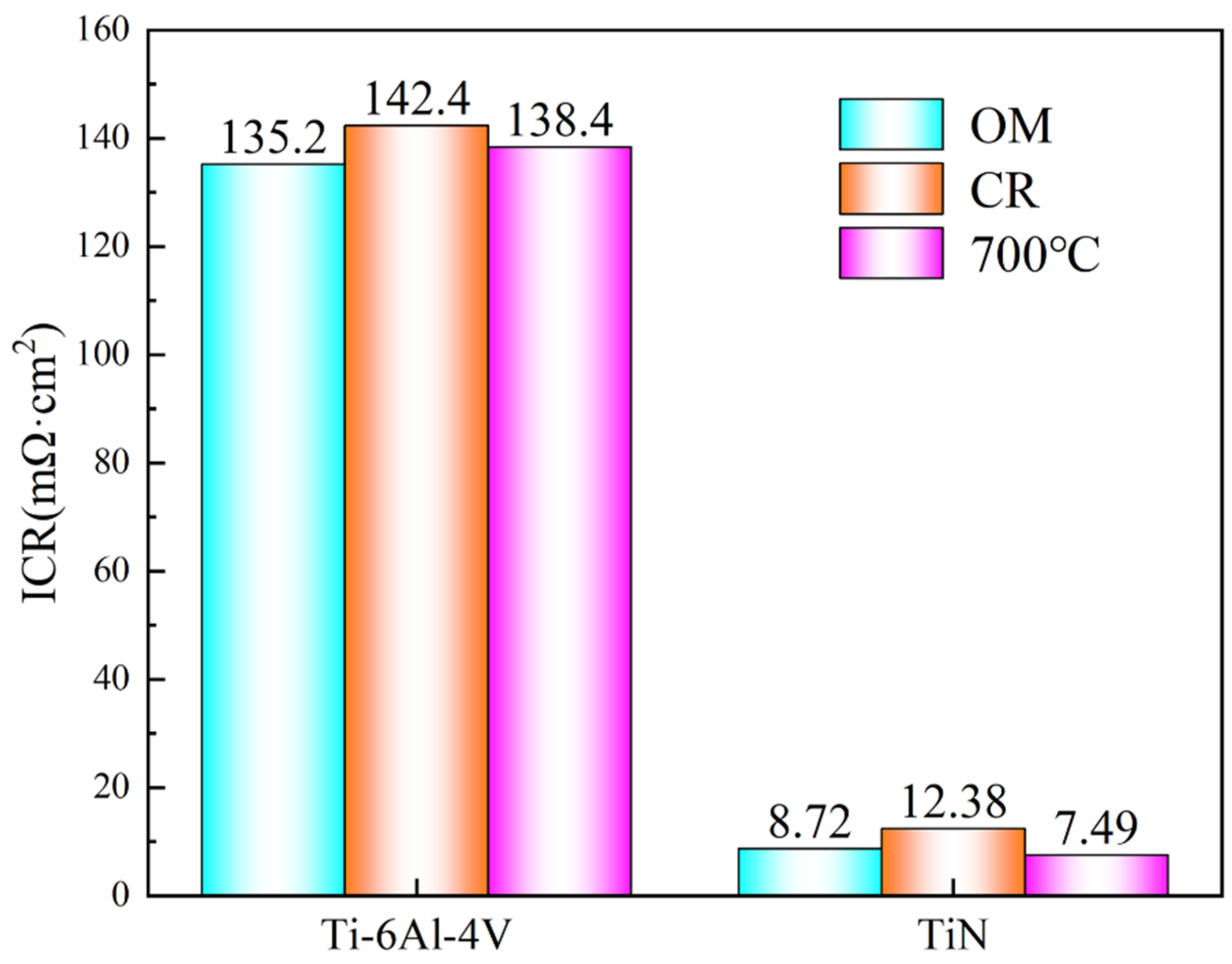

5. ICR Testing

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- After large plastic deformation through asymmetrical rolling, the Ti-6Al-4V samples exhibited microstructures composed of numerous substructured grains formed under shear stress. Significant grain refinement was achieved, which is beneficial for improving both corrosion resistance and elongation.

- (2)

- With increasing annealing temperature, the grain size gradually increased, and the GND density first increased and then decreased. At 700 °C, recrystallization was nearly complete, with an average grain size of 1.74 μm and a GND density reduced to 3.52 × 1014 m−2. When the annealing temperature exceeded 700 °C, the grains coarsened, the α and β phase size gradients increased, and the GND density rose again, resulting in a decrease in elongation.

- (3)

- As the annealing temperature was raised, a gradual decrease in the tensile strength of the Ti-6Al-4V ultra-thin strip was observed, while the elongation first increased and then declined. At 700 °C, uniformly equiaxed grains were formed, whose boundaries promoted dislocation movement and enhanced strain coordination, achieving an optimal balance of strength (887 MPa) and ductility (13.7%).

- (4)

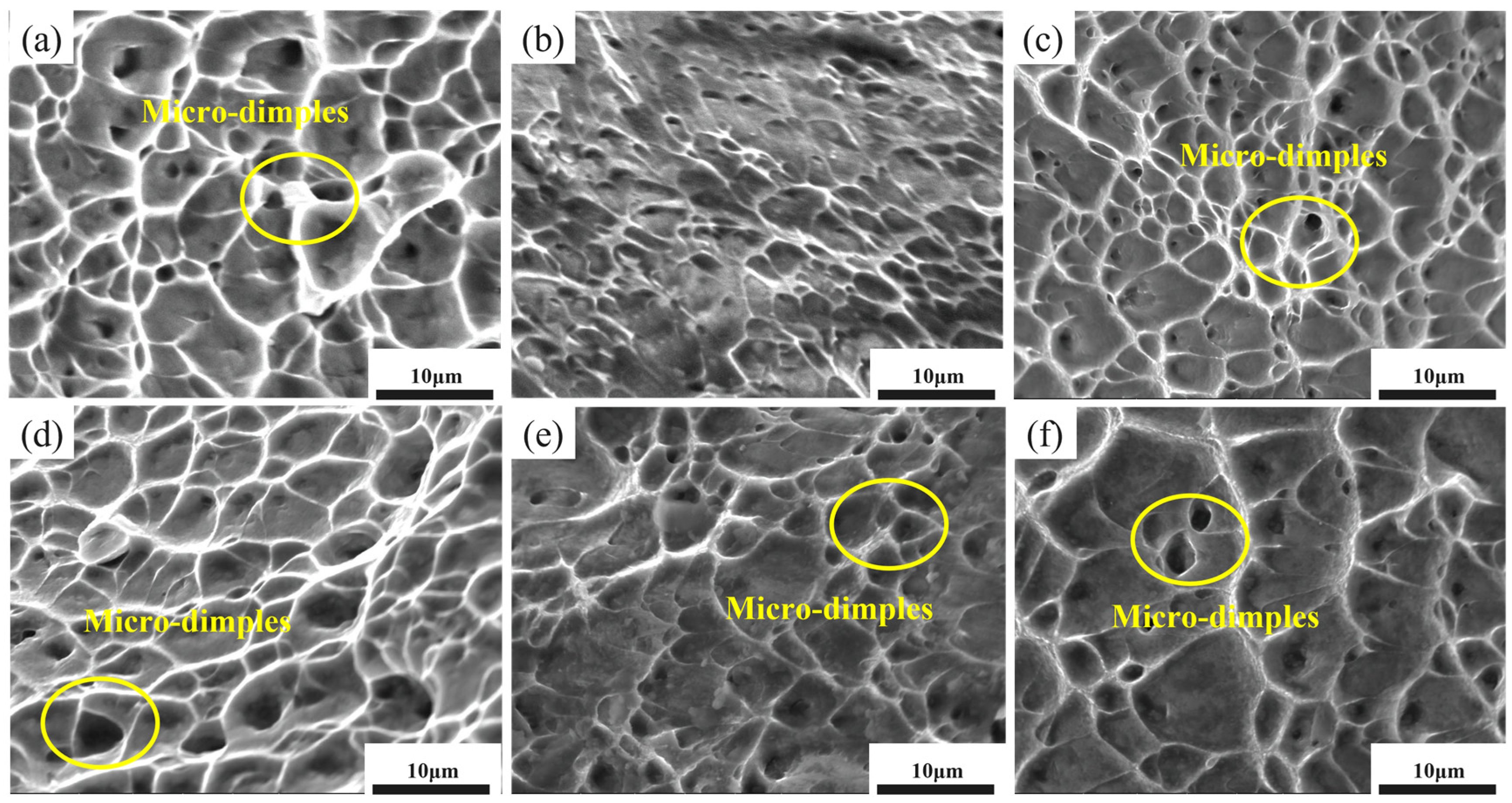

- Fractography analysis showed that the dimple morphology varied with annealing temperature. At 700 °C, large and deep dimples were observed, indicating typical ductile fracture. Moreover, the work-hardening rate curve exhibited the longest uniform deformation stage, which helps prevent strain localization during stamping.

- (5)

- After TiN coating, the Ti-6Al-4V ultra-thin strip exhibited significantly improved corrosion resistance and electrical conductivity. The impedance spectra and fitting results clearly show that the corrosion resistance and stability of the material are significantly improved after coating. In particular, the sample annealed at 700 °C showed a decreased corrosion current density of 9.865 × 10−8A·cm−2 and ICR of 7.49 mΩ·cm2, meeting the 2025 DOE standard.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, T.; Islam, M.; He, X.; Saha, B. Application of metallic bipolar plates in PEMFCs: A comprehensive review of performance and durability. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2026, 226, 116421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Feng, Q.; Wang, H.; Li, H. Molybdenum carbide coated 316L stainless steel for bipolar plates of proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 4940–4950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Sabir, I. Review of bipolar plates in PEM fuel cells: Flow-field designs. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 359–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Tu, Z.; Chan, S.H. Recent development of hydrogen and fuel cell technologies: A review. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 8421–8446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Yuan, X.; Liu, G.; Wei, B.; Zhang, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H. A review of proton exchange membrane water electrolysis on degradation mechanisms and mitigation strategies. J. Power Sources 2017, 366, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toops, T.; Brady, M.; Zhang, F.-Y.; Meyer, H.M.; Ayers, K.; Roemer, A.; Dalton, L. Evaluation of nitrided titanium separator plates for proton exchange membrane electrolyzer cells. J. Power Sources 2014, 272, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.F.; Adesina, A.Y.; Gasem, Z.M. Electrochemical and electrical resistance behavior of cathodic arc PVD TiN, CrN, AlCrN, and AlTiN coatings in simulated proton exchange membrane fuel cell environment. Mater. Corros. 2019, 70, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Jiang, J.; Wang, R.; Yue, Y.; Chen, Y.; Pan, T. Anti-corrosion and conductivity of titanium diboride coating on metallic bipolar plates. Corros. Sci. 2020, 170, 108646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Duan, L.; Guo, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Tuan, W.-H.; Niihara, K. TiN-coated titanium as the bipolar plate for PEMFC by multi-arc ion plating. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 9155–9161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Dong, C.; Zhang, T.; Xiao, K.; Ji, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, X. Effect of plasma electrolytic nitriding on the corrosion behavior and interfacial contact resistance of titanium in the cathode environment of proton-exchange membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2019, 418, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y. Surface microstructure and performance of TiN monolayer film on titanium bipolar plate for PEMFC. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 31382–31390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Qiu, D.; Yi, P.; Peng, L. Towards mass applications: A review on the challenges and developments in metallic bipolar plates for PEMFC. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2020, 30, 815–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, A.; Chaudhuri, T.; Spagnol, P. Bipolar plates for PEM fuel cells: A review. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2005, 30, 1297–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, R.; Murty, S.V.S.N.; Alankar, A. Dynamic recrystallization in titanium alloys: A comprehensive review. Mater. Perform. Charact. 2020, 9, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, D.; Fabris, M.; Sivaswamy, G.; Rahimi, S.; Vorontsov, V. Miniaturised experimental simulation and combined modelling of open-die forging of Ti-6Al-4V titanium alloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 3622–3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, S.; Ueno, A.; Akebono, H. Combined effects of low temperature nitriding and cold rolling on fatigue properties of commercially pure titanium. Int. J. Fatigue 2020, 139, 105772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.W.; Lee, S.; Choe, H.-J.; Hyun, Y.-T.; Lee, D.W.; Lee, J.H. Recovery of sheet formability of cold-rolled pure titanium by cryogenic-deformation treatment. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 889, 145868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Peng, L.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Ran, R.; Yuan, G. Effect of annealing temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of cold-rolled commercially pure titanium sheets. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2022, 32, 2587–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, S.; Huang, Z.; Li, S.; Huang, Z.; Yu, H. Anisotropic mechanism of cold-rolled pure titanium plate during the two-step tensile process of the variable path. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2024, 906, 146755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Yu, D.; Zheng, W.; Xu, C.; Wang, Z.; Feng, L.; Chen, X.; Pan, F. An ultrahigh strain-independent damping capacity in Mg–1Mn alloy by cold rolling process. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 25, 4330–4341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, H.; Cao, S.; Peng, J.; Guo, P.; Long, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, C.; Wu, Y.; Huang, J.; et al. Effect of cerium alloying on microstructure, texture and mechanical properties of magnesium during cold-rolling process. J. Rare Earths 2024, 42, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Deng, X.; Zhang, F.; Wang, L.; Guo, D. Hot and cold rolling of a novel near-α titanium alloy: Mechanical properties and underlying deformation mechanism. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2023, 863, 144543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Yan, M.; Li, J.; Godbole, A.; Lu, C.; Tieu, K.; Li, H.; Kong, C. Mechanical properties and microstructure of a Ti-6Al-4V alloy subjected to cold rolling, asymmetric rolling and asymmetric cryorolling. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2018, 710, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Dong, P.; Zeng, S.; Wu, B. Effects of recrystallization on microstructure and texture evolution of cold-rolled Ti-6Al-4V alloy. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2016, 25, 1931–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Kim, W. Effect of roll speed ratio on the texture and microstructural evolution of an FCC high-entropy alloy during differential speed rolling. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 111, 152–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uniwersał, A.; Wroński, M.; Wróbel, M.; Wierzbanowski, K.; Baczmański, A. Texture effects due to asymmetric rolling of polycrystalline copper. Acta Mater. 2017, 139, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamimi, S.; Gracio, J.J.; Lopes, A.B.; Ahzi, S.; Barlat, F. Asymmetric rolling of interstitial free steel sheets: Microstructural evolution and mechanical properties. J. Manuf. Process. 2018, 31, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Gao, H.; Kong, C.; Wang, Z.; Cui, H.; Yu, H. Transverse texture weakening and anisotropy improvement of Ti-6Al-4V alloy sheet via asymmetric rolling and static recrystallization annealing. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1010, 177507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Chen, W. Preparation technology of bulk ultrafine-grained metallic materials by severe plastic deformation. J. Plast. Eng. 2010, 17, 123–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valiev, R.Z.; Islamgaliev, R.K.; Alexandrov, I.V. Bulk nanostructured materials from severe plastic deformation. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2000, 45, 103–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolyarov, V.; Zhu, Y.; Lowe, T.; Islamgaliev, R.; Valiev, R. A two step SPD processing of ultrafine-grained titanium. Nanostructured Mater. 1999, 11, 947–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kong, C.; Yu, H. High strength and toughness of Ti–6Al–4V sheets via cryorolling and short-period annealing. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 854, 143766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Sweikart, M.; John, A.T. Stainless steel as bipolar plate material for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. J. Power Sources 2003, 115, 243–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Yang, P. Interaction among deformation, recrystallization and phase transformation of TA2 pure titanium during hot compression. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2016, 26, 1863–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, T.; Belyakov, A.; Kaibyshev, R.; Miura, H.; Jonas, J.J. Dynamic and post-dynamic recrystallization under hot, cold and severe plastic deformation conditions. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2014, 60, 130–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradhan, S.; Tripathy, S.; Singh, R.; Murugaiyan, P.; Roy, D.; Humane, M.M.; Chowdhury, S.G. On the grain boundary character evolution in non equiatomic high entropy alloy during hot rolling induced dynamic recrystallization. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 922, 166126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, J.; Hartmaier, A. Elucidating the dual role of grain boundaries as dislocation sources and obstacles and its impact on toughness and brittle-to-ductile transition. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, T.; Yang, X.; Liu, T.; Xie, Q.; Hu, X.; Zhi, Y. Effect of annealing temperature on microstructure and mechanical properties of asymmetrically rolled unalloyed titanium ultra-thin strips. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2025, 924, 147773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunt, D.; Xu, X.; Busolo, T.; da Fonseca, J.Q.; Preuss, M. Quantification of strain localisation in a bimodal two-phase titanium alloy. Scr. Mater. 2018, 145, 45–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Liu, D.; Yuan, C.; Zhou, C.; Wan, M.; Huang, C. Tailoring the mechanical performance of electron beam melting fabricated TC4 alloy via post-heat treatment. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.-C.; Yang, T.-C.; Li, K.-C. Studies on the fabrication of metallic bipolar plates-Using micro electrical discharge machining milling. J. Power Sources 2011, 196, 2070–2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Lee, C.-Y.; Yang, K.-T.; Kuan, F.-H.; Lai, P.-H. Simulation and fabrication of micro-scaled flow channels for metallic bipolar plates by the electrochemical micro-machining process. J. Power Sources 2008, 185, 1115–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.K.; Kang, C.G. Fabrication by vacuum die casting and simulation of aluminum bipolar plates with micro-channels on both sides for proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2012, 37, 1661–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Molina, M.; Amores, E.; Rojas, N.; Kunowsky, M. Additive manufacturing of bipolar plates for hydrogen production in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 38983–38991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, S.; Timurkutluk, B.; Aydin, U.; Yagiz, M. Development of titanium bipolar plates fabricated by additive manufacturing for PEM fuel cells in electric vehicles. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 37956–37966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, Y.; Ming, P.; Yang, D.; Zhang, C. Stainless steel bipolar plates for proton exchange membrane fuel cells: Materials, flow channel design and forming processes. J. Power Sources 2020, 451, 227783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Pereira, M.P.; Rolfe, B.F.; Wilkosz, D.E.; Hodgson, P.; Weiss, M. Investigation of material failure in micro-stamping of metallic bipolar plates. J. Manuf. Process 2022, 73, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, N.; Zhang, X.; Hou, Z.; Wang, W.; Yang, D.; Min, J.; Ming, P.; Zhang, C. Hot stamping of ultra-thin stainless steel sheets for bipolar plates. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2023, 317, 117987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balyanov, A.; Kutnyakova, J.; Amirkhanova, N.A.; Stolyarov, V.V.; Valiev, R.Z.; Liao, X.Z.; Zhao, Y.H.; Jiang, Y.B.; Xu, H.F.; Lowe, T.C.; et al. Corrosion resistance of ultra fine-grained Ti. Scr. Mater. 2004, 51, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Zhang, D.; Qiu, D.; Peng, L.; Lai, X. Carbon-based coatings for metallic bipolar plates used in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2019, 44, 6813–6843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ti | Al | V | Fe | C | N | O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bal | 6.30 | 4.19 | 0.191 | 0.010 | 0.004 | 0.124 |

| Pass | Thickness Before Rolling (H)/μm | Thickness After Rolling (h)/μm | Thickness After Rolling γ/% | Asymmetrical Speed Ratio (i) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 450 | 350 | 22.2 | 1.05 |

| 2 | 350 | 290 | 17.1 | 1.05 |

| 3 | 290 | 246 | 15.2 | 1.05 |

| 4 | 246 | 211 | 14.2 | 1.05 |

| 5 | 211 | 183 | 13.3 | 1.07 |

| 6 | 183 | 160 | 12.6 | 1.07 |

| 7 | 160 | 143 | 10.6 | 1.07 |

| 8 | 143 | 129 | 9.8 | 1.10 |

| 9 | 129 | 117 | 9.3 | 1.10 |

| 10 | 117 | 107 | 8.5 | 1.13 |

| 11 | 107 | 100 | 6.5 | 1.15 |

| 12 | 100 | 94 | 6.0 | 1.15 |

| 13 | 94 | 89 | 5.5 | 1.17 |

| 14 | 89 | 84 | 5.5 | 1.23 |

| 15 | 84 | 80 | 5.0 | 1.23 |

| 16 | 80 | 77 | 3.8 | 1.25 |

| 17 | 77 | 75 | 2.6 | 1.25 |

| Sample | Eccor/V | Iccor/A·cm−2 | βa/mv | βc/mv |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM | −0.389 | 5.207 × 10−6 | 181.3 | 221.2 |

| 75 μm-CR | −0.33 | 2.366 × 10−6 | 185.4 | 202.1 |

| 75 μm-700 °C | −0.237 | 1.302 × 10−6 | 191.7 | 227 |

| OM-TiN | −0.059 | 7.277 × 10−7 | 348.9 | 138.8 |

| 75 μm-TiN | 0.029 | 3.211 × 10−7 | 326.7 | 135.9 |

| 75 μm-700 °C-TiN | 0.077 | 9.865 × 10−8 | 310.4 | 143.7 |

| Sample | Rs/Ω·cm2 | Rf/Ω·cm2 | Rct/Ω·cm2 | Q1/F·cm−2 | Q2/F·cm−2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OM | 30.68 | 6.93 × 103 | - | 4.72 × 10−4 | - |

| 75 μm-CR | 29.73 | 8.65 × 103 | - | 3.15 × 10−4 | - |

| 75 μm-700 °C | 28.35 | 9.36 × 103 | - | 2.41 × 10−4 | - |

| OM-TiN | 25.18 | 2.28 × 104 | 5.72 × 104 | 4.11 × 10−4 | 2.87 × 10−4 |

| 75 μm-CR-TiN | 27.43 | 4.36 × 104 | 6.17 × 104 | 2.53 × 10−4 | 1.55 × 10−4 |

| 75 μm-700 °C-TiN | 24.27 | 7.28 × 104 | 8.28 × 104 | 2.24 × 10−4 | 1.01 × 10−4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, T.; Liu, T.; Jiang, M.; Huang, P.; Yang, X.; Hu, X. Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Asymmetrically Rolled Ultra-Thin Ti-6Al-4V. Materials 2025, 18, 5436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235436

Sun T, Liu T, Jiang M, Huang P, Yang X, Hu X. Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Asymmetrically Rolled Ultra-Thin Ti-6Al-4V. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235436

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Tao, Tan Liu, Mingpei Jiang, Peng Huang, Xianli Yang, and Xianlei Hu. 2025. "Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Asymmetrically Rolled Ultra-Thin Ti-6Al-4V" Materials 18, no. 23: 5436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235436

APA StyleSun, T., Liu, T., Jiang, M., Huang, P., Yang, X., & Hu, X. (2025). Effects of Annealing Temperature on the Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Asymmetrically Rolled Ultra-Thin Ti-6Al-4V. Materials, 18(23), 5436. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235436