Comprehensive Review on Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Fibers and Waste Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Fibers Used in Concrete

3.1. High Elastic Modulus (HEM) Fibers

3.1.1. Glass Fiber

3.1.2. Basalt Fiber

3.1.3. Carbon Fiber

3.2. Low Elastic Modulus (LEM) Fibers

3.2.1. Natural Fibers

Jute Fiber

Sisal Fiber

Banana Fiber

3.2.2. Synthetic Fibers

Polyester Fiber

Polyamide (Nylon) Fiber

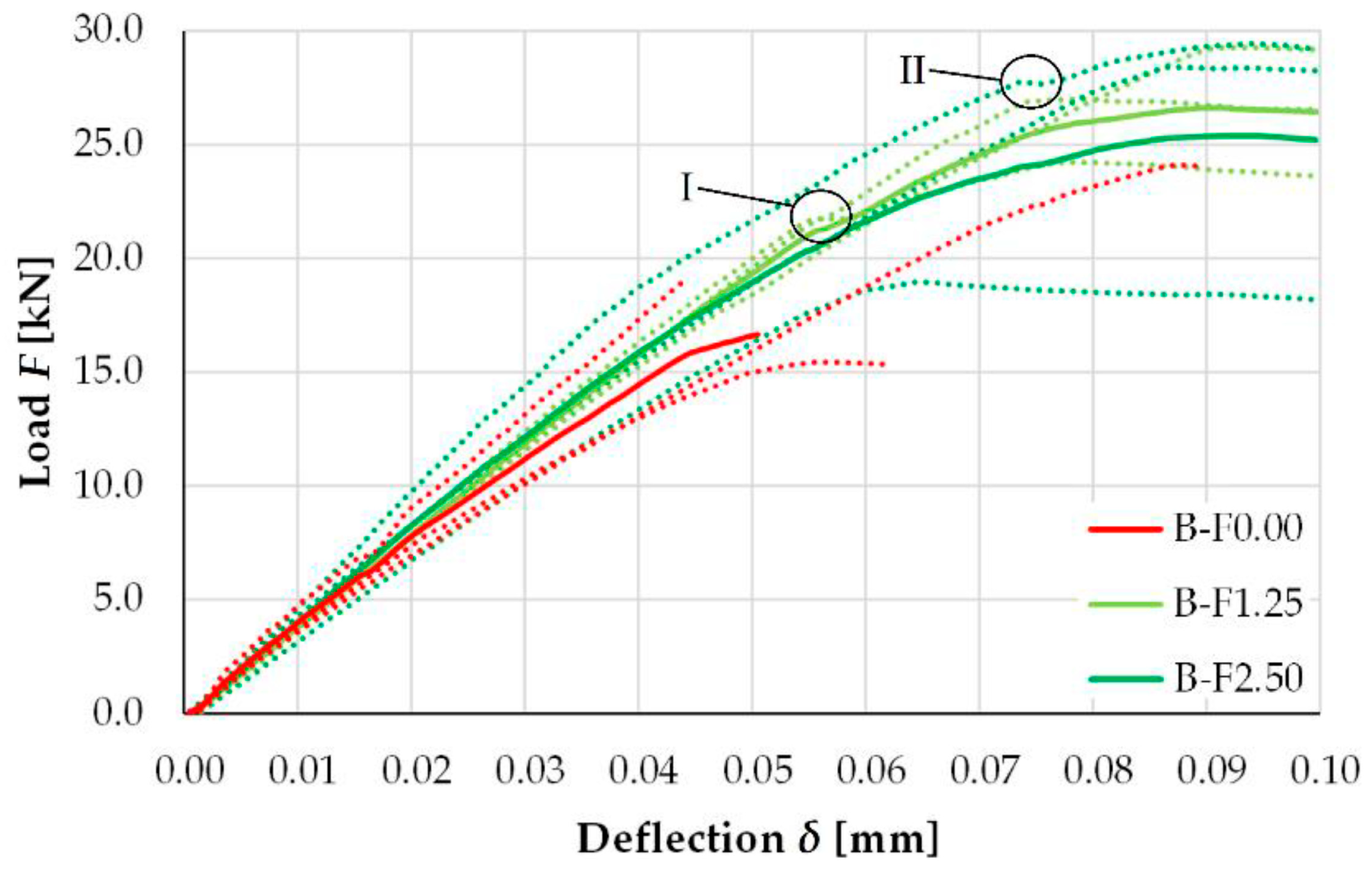

Polypropylene (PP) Fiber

High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE)

4. Various Types of Waste Fibers Used as Reinforcement in Concrete

4.1. Non-Biodegradable Waste

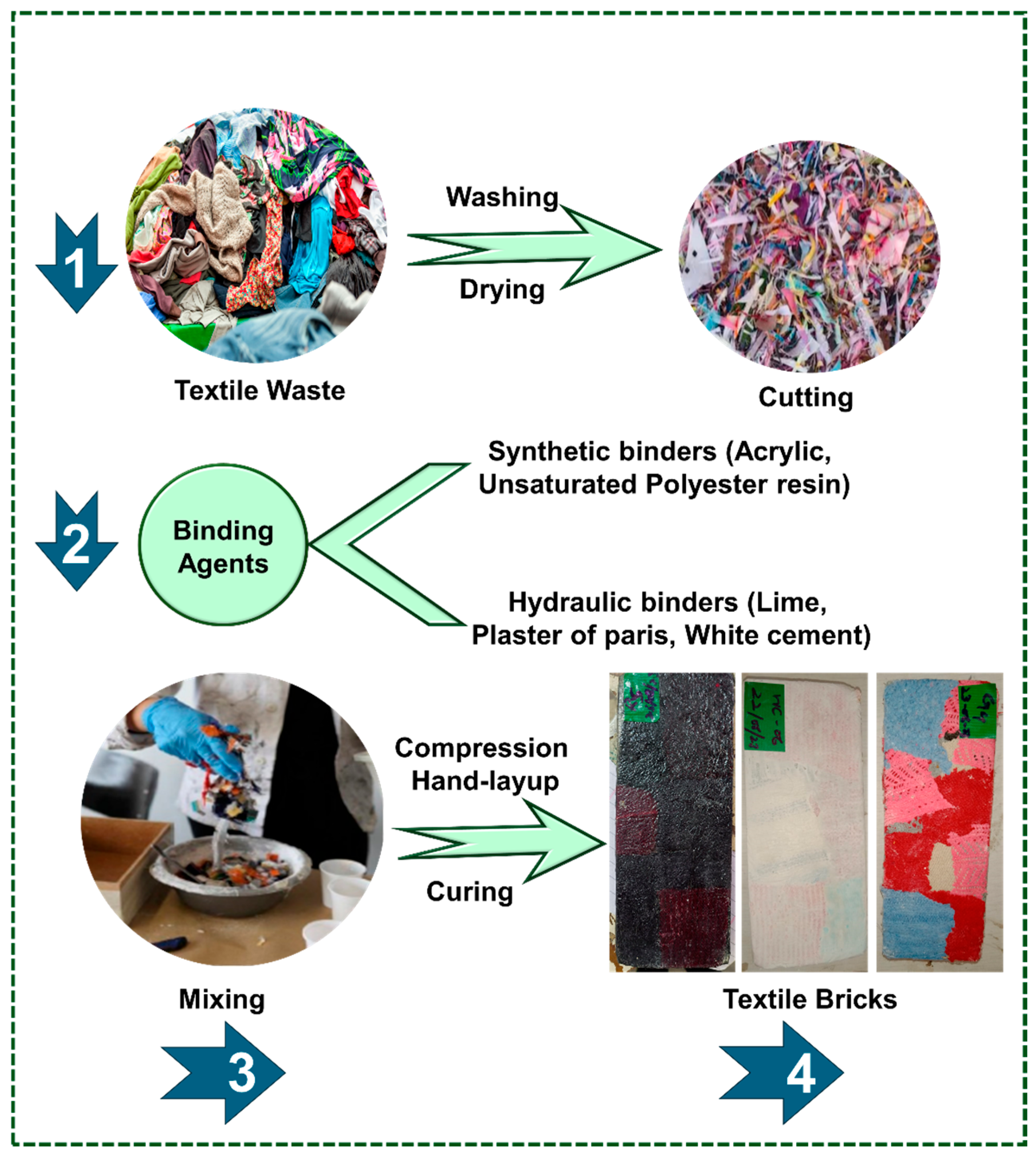

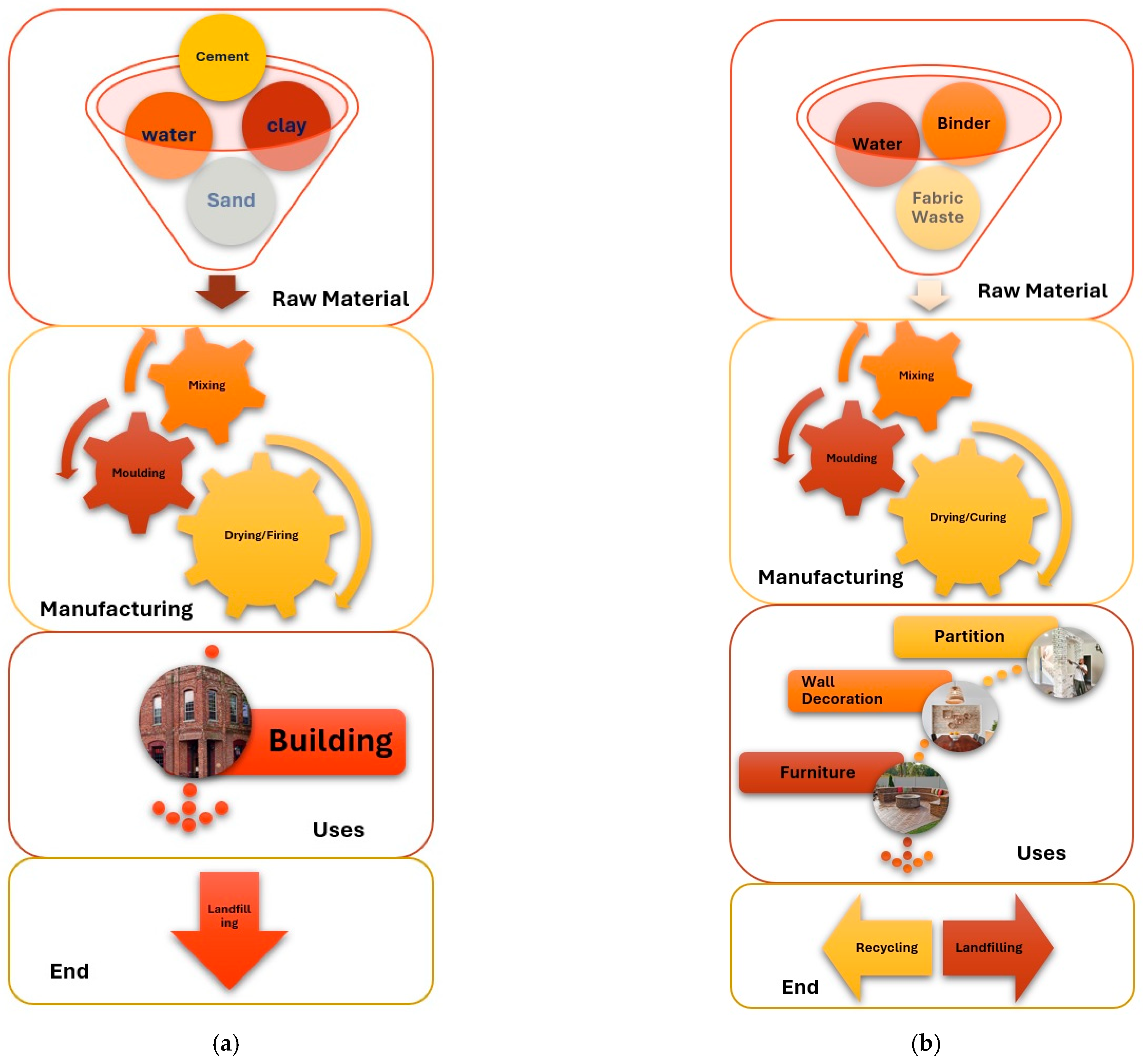

4.1.1. Different Types of Polymeric/Textile Wastes

4.1.2. Steel Waste Fibers

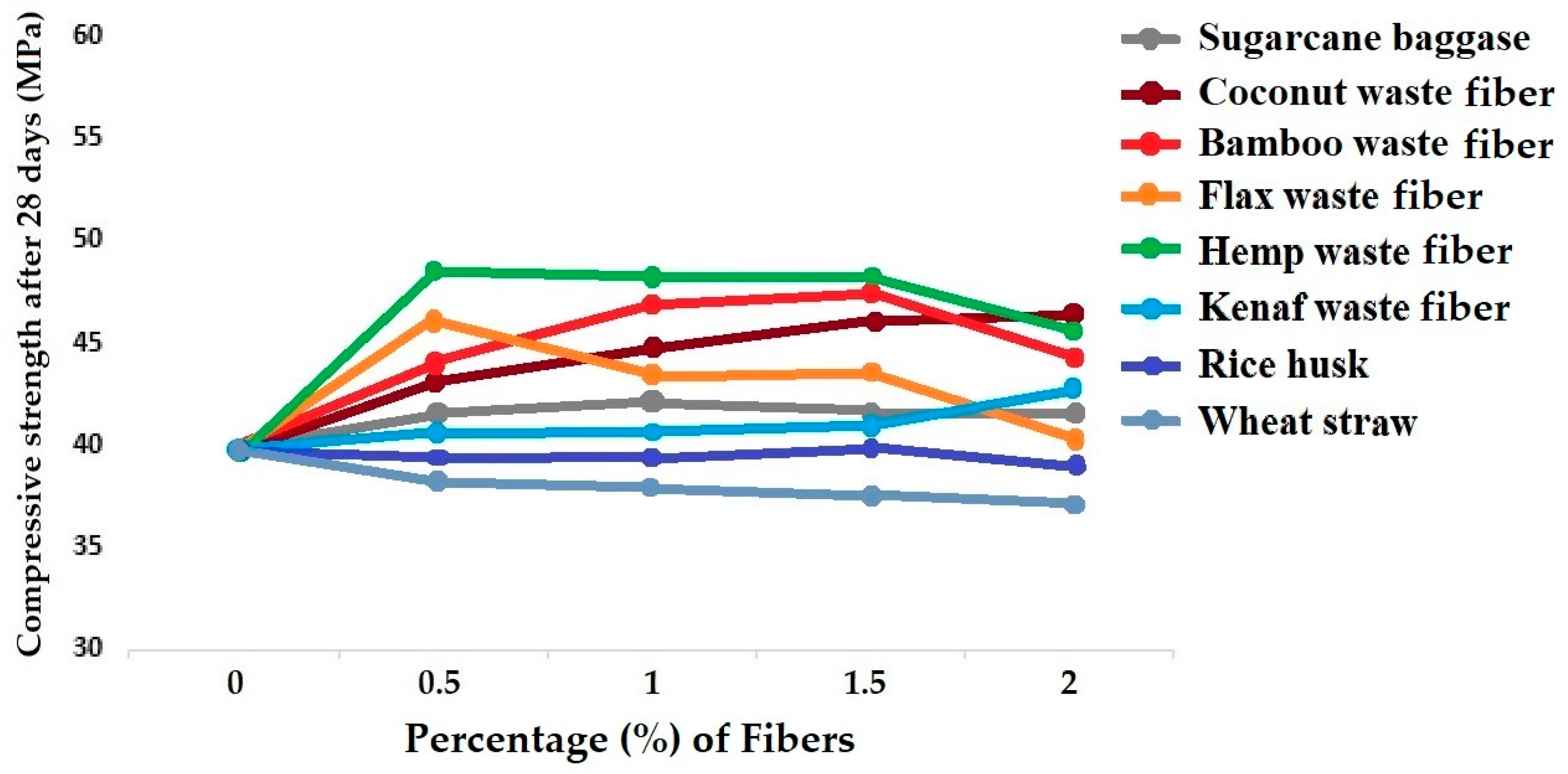

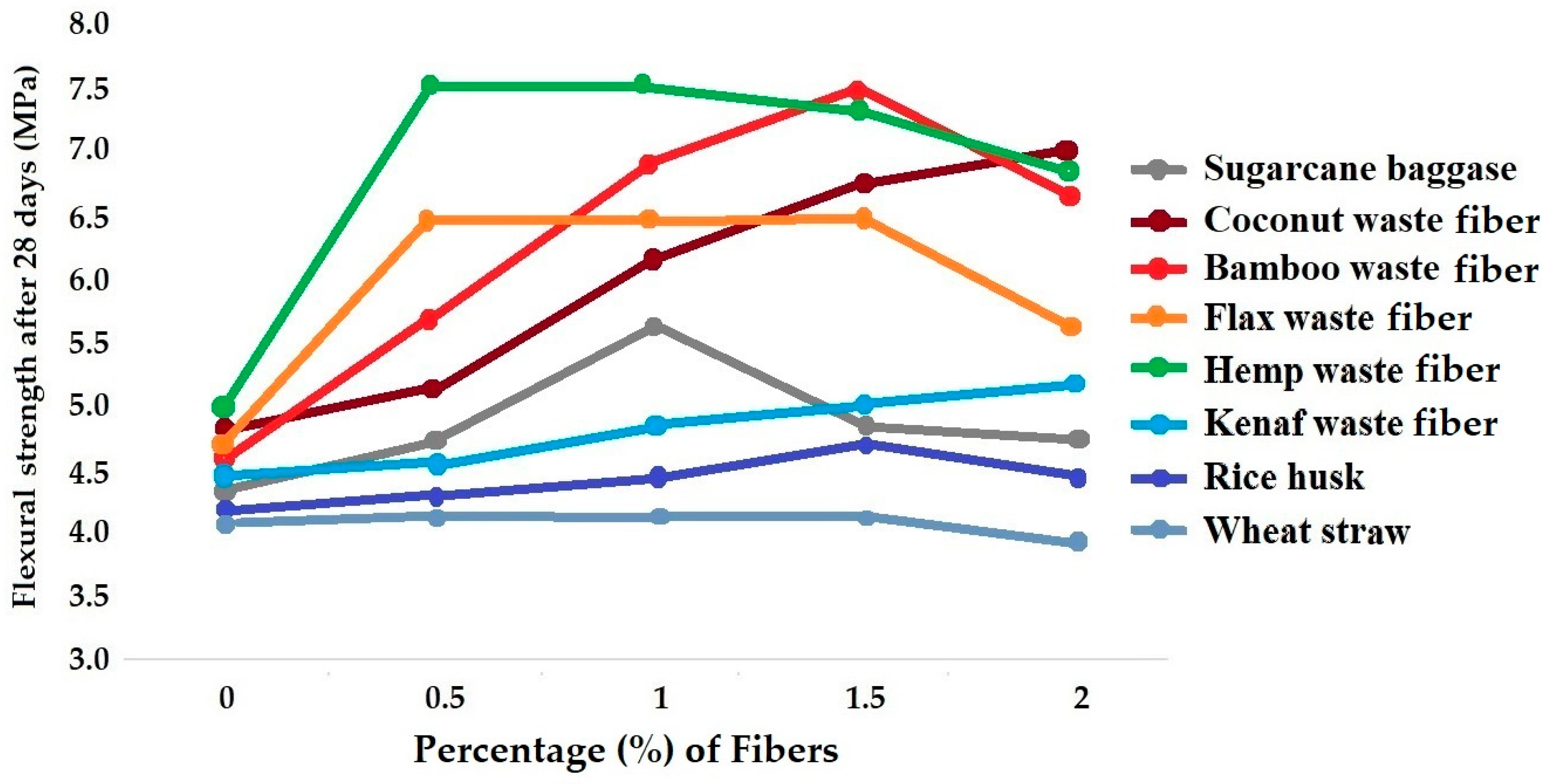

4.2. Biodegradable Waste Materials

4.2.1. Coconut Waste Fibers

4.2.2. Sugarcane Waste Fibers

4.2.3. Rice Husk

4.2.4. Wheat Straw

4.2.5. Bamboo Waste Fiber

4.2.6. Flax and Hemp Waste Fibers

4.2.7. Kenaf Waste Fiber

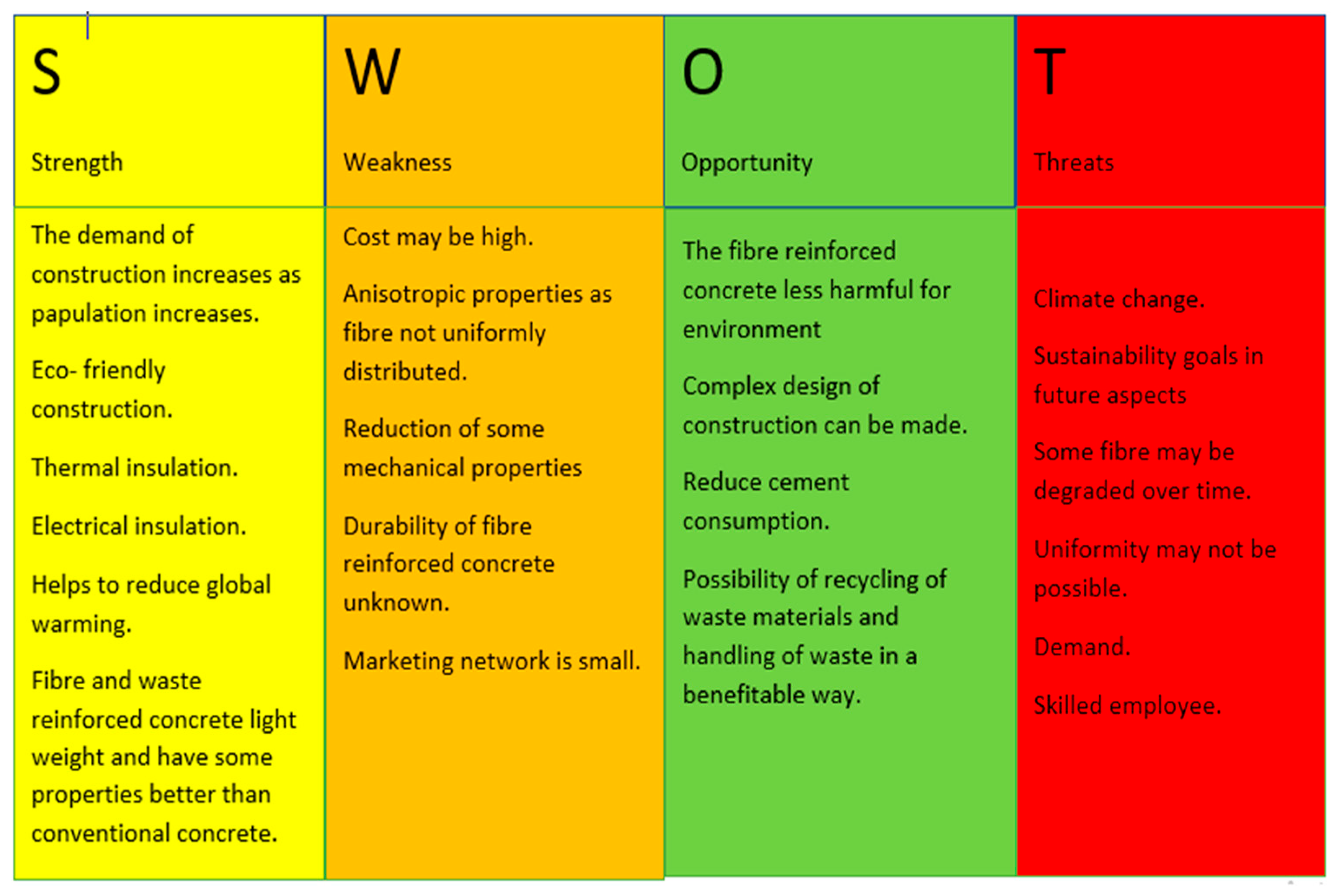

5. Conclusions

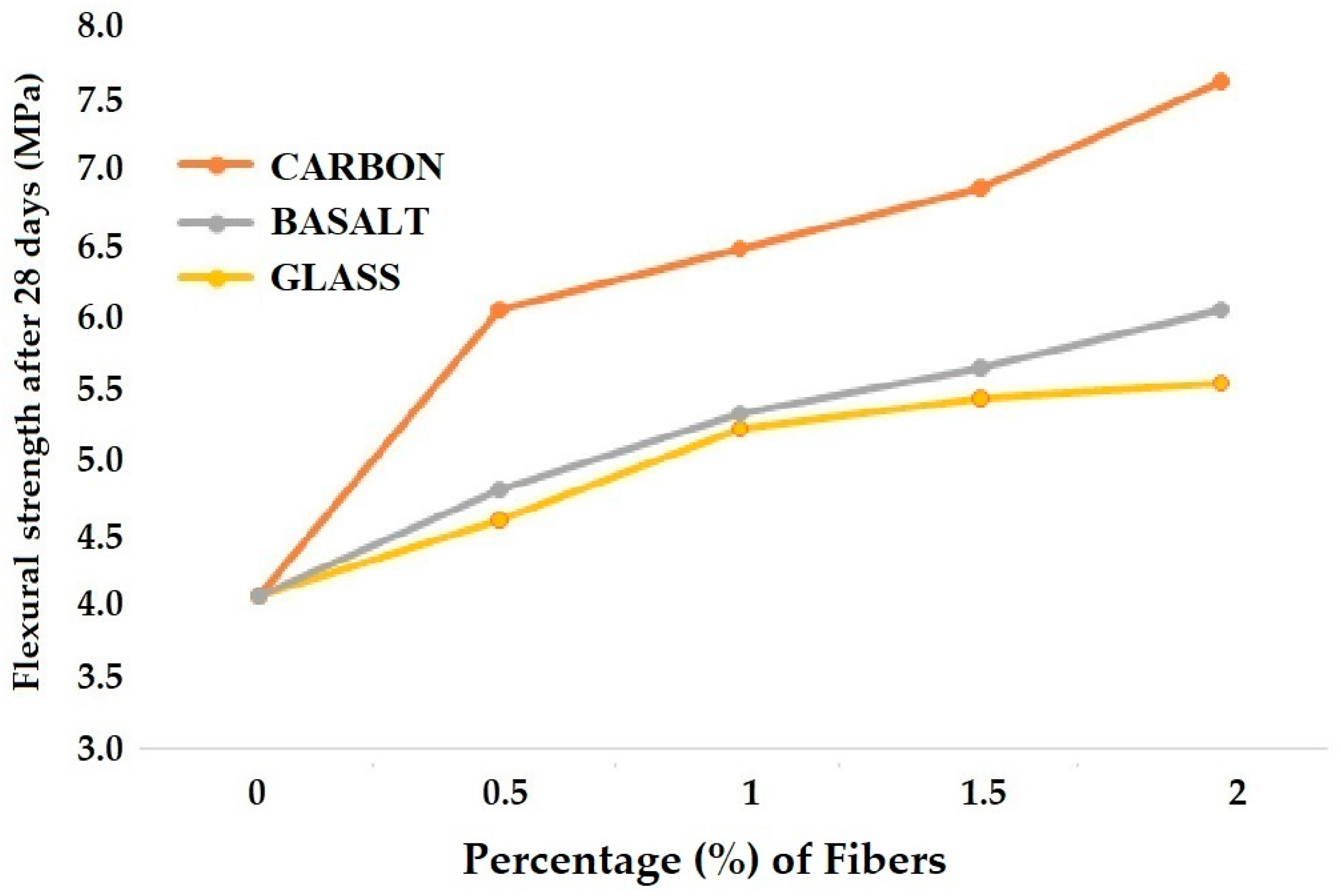

- The concrete containing glass fiber is more durable, non-corrosive, lightweight, and cost-effective for high-performance applications. Glass fiber can be used as a partial replacement of cement with an optimum content of 1%. The potential application of glass fiber can be used in exterior building structures;

- Basalt fiber increases the strength, ductility, and thermal resistance of concrete. The addition of basalt fiber to partially reduce cement consumption affects the environment in a positive way. The potential application of basalt fiber in construction is for anti-seismic buildings and buildings that are exposed to high pressure/temperatures;

- Carbon fiber-reinforced concrete is durable, has high strength, and can be used for anti-seismic constructions. However, it is more expensive than conventional concrete;

- Natural fibers are low-cost and easily available alternatives for replacing certain components in concrete. Concrete reinforced with natural-origin fibers, e.g., jute, sisal, and banana, shows improved mechanical properties. The flexural and compressive strengths of concrete can be improved by the inclusion of only 1% natural fibers. These fibers can be used after special chemical treatment so that they will not decay quickly. The potential application of concrete reinforced with natural fibers can be in wall panels, interiors, roof tiles, etc;

- Synthetic fibers, e.g., polyester, polypropylene, polyamide (nylon), and high-density polyethylene (HDPE), can be used to partially replace some part of cement, fine aggregates, or coarse aggregates in concrete. These fibers can enable concrete to avoid plastic shrinkage and increase resistance to cracking. The mechanical performance of the concrete can be improved only when the fiber percentage is between 1 and 2%. The possible applications of synthetic fiber-reinforced concrete can be in industrial floors, tunnels, canals, tiles, and residential construction projects;

- Waste materials, such as biodegradable and non-biodegradable fibrous materials, can replace some part of cement and coarse aggregates. Use of fibrous waste materials in concrete improves some mechanical and chemical properties, and in addition, the waste material handling is carried out in an efficient way. Waste fibers from coconut, sugarcane, flax, hemp, bamboo, and kenaf used in concrete increase the ductility and the compressive strength when used at 0.5–2% content;

- Some types of agrowaste (biomass), e.g., rice husk or wheat straw, can help in reducing the overall weight and density of the construction; however, they do not improve the mechanical performance significantly.

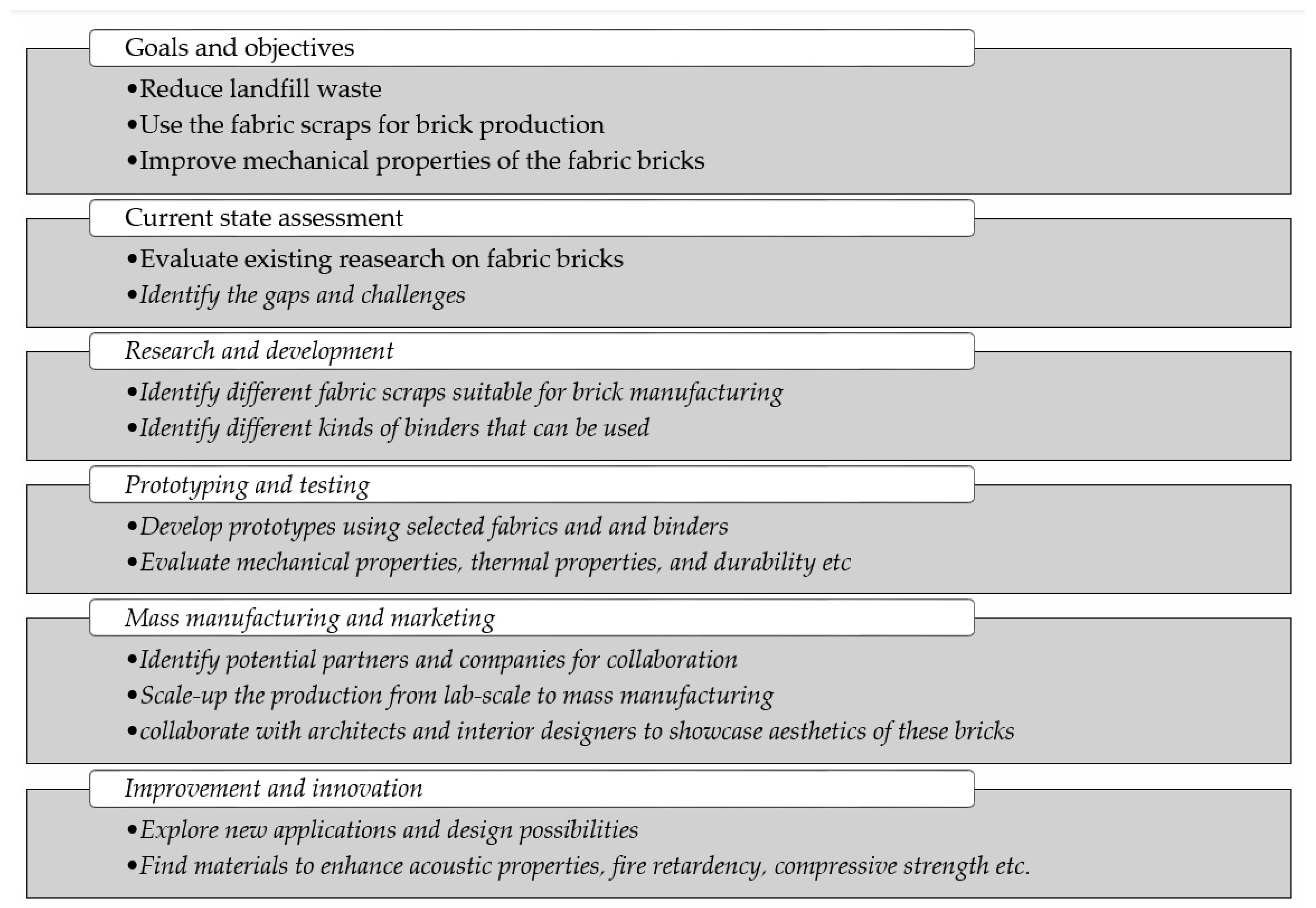

6. Future Strategies

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Flower, D.J.M.; Sanjayan, J.G. Green house gas emissions due to concrete manufacture. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2007, 12, 282–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petek Gursel, A.; Masanet, E.; Horvath, A.; Stadel, A. Life-cycle inventory analysis of concrete production: A critical review. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 51, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y. Performance assessment and design of ultra-high performance concrete (UHPC) structures incorporating life-cycle cost and environmental impacts. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 167, 414–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curbach, M.; Jesse, F. High-Performance Textile-Reinforced Concrete. Struct. Eng. Int. J. Int. Assoc. Bridge Struct. Eng. (IABSE) 1999, 9, 289–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, D.; Bolan, N.S.; Tsang, D.C.W.; Kirkham, M.B.; O’Connor, D. Sustainable soil use and management: An interdisciplinary and systematic approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 729, 138961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ütebay, B.; Çelik, P.; Çay, A. Textile Wastes: Status and Perspectives. Waste Text. Leather Sect. 2020, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Shah, A.; Shoaib, M.; Mishra, R.K. Recycled-Textile-Waste-Based Sustainable Bricks: A Mechanical, Thermal, and Qualitative Life Cycle Overview. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Symeonides, D.; Loizia, P.; Zorpas, A.A. Tire waste management system in Cyprus in the framework of circular economy stratégy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 35445–35460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, N.U.; Bassey, D.E.; Palanisami, T. COVID pollution: Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on global plastic waste footprint. Heliyon 2021, 7, e06343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oraimi, S.K.; Seibi, A.C. Mechanical characterisation and impact behaviour of concrete reinforced with natural fibres. Compos. Struct. 1995, 32, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihra, R.; Baheti, V.; Behera, B.K.; Militky, J. Novelties of 3-D woven composites and nanocomposites. J. Text. Inst. 2013, 105, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foti, D. Preliminary analysis of concrete reinforced with waste bottles PET fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1906–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakor, P.; Pimplikar, S.S. Glass Fibre Reinforced Concrete Use in Construction. Int. J. Technol. Eng. Syst. (IJTES) 2011, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Chandramouli, K.; Srinivasa Rao, P.; Pannirselvam, N.; Seshadri Sekhar, T.; Sravana, P. Strength properties of glass fibre concrete. ARPN J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2010, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Bobde, S.; Gandhe, G.; Tupe, D. Performance of glass fibre reinforced concrete. Int. J. Adv. Res. Ideas Innov. Technol. 2018, 4, 984–988. [Google Scholar]

- Bertolini, L. Steel corrosion and service life of reinforced concrete structures. Struct. Infrastruct. Eng. 2008, 4, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.X.; Lian, J. Basalt fibre reinforced concrete. Adv. Mater. Res. 2011, 194–196, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, B.; Eswari, S. Mechanical behaviour of basalt fibre reinforced concrete: An experimental study. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 2317–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Jia, B.; Huang, H.; Mou, Y. Experimental Study on Basic Mechanical Properties of Basalt Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Materials 2020, 13, 1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, R.K.; Behera, B.K.; Chandan, V.; Nazari, S.; Muller, M. Modeling and Simulation of Mechanical Performance in Textile Structural Concrete Composites Reinforced with Basalt Fibres. Polymers 2022, 14, 4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutanji, H.A.; El-Korchi, T.; Katz, R.N. Strength and reliability of carbon-fibre-reinforced cement composites. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1994, 16, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.W.; Chung, D.D.L. Concrete reinforced with up to 0.2 vol% of short carbon fibres. Composites 1993, 24, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, J.; Zhou, J.; Wen, X. The mechanical properties and microstructure of carbon fibres reinforced coral concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 249, 118771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljalawi, N.; Al-Jelawy, H. Possibility of Using Concrete Reinforced by Carbon Fibre in Construction. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 449–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamble, Z.; Behera, B.K.; Behera, P.K. Influence of cellulosic and non-cellulosic particle fillers on mechanical, dynamic mechanical, and thermogravimetric properties of waste cotton fibre reinforced green composites. Compos. Part B Eng. 2021, 207, 108595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghugal, Y.M.; Naghate, S.V. Performance of extruded polyester fibre reinforced concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 2016, 43, 247–257. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, J.; Zaid, O.; Pérez, C.L.-C.; Martínez-García, R.; López-Gayarre, F. Experimental Research on Mechanical and Permeability Properties of Nylon Fibre Reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete with Mineral Admixture. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohaib, N.; Seemab, F.; Sana, G.; Mamoon, R. Using Polypropylene Fibres in Concrete to achieve maximum strength. Int. J. Civ. Struct. Eng.—IJCSE 2018, 5, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, Z.A.; Kaleem, M.M.; Usman, M.; Jawad, M.; Ajwad, A. Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Normal & Polypropylene Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Sci. Inq. Rev. 2018, 2, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamigboye, G.; Ngene, B.; Aladesuru, O.; Mark, O.; Adegoke, D.; Jolayemi, K. Compressive Behaviour of Coconut Fibre (Cocos nucifera) Reinforced Concrete at Elevated Temperatures. Fibres 2020, 8, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Hussain, U.; Tichy, M.; Muller, M. Turning textile waste into valuable yarn. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2021, 5, 100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Ali, H.; Mishra, R.K.; Nazari, S.; Chandan, V. Durability and Accelerated Ageing of Natural Fibres in Concrete as a Sustainable Construction Material. Materials 2023, 16, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.; Suresh, T.K.; Krishnajith, V.; Saravanan, S. Experimental Study and Behaviour of Concrete with Sisal Fibre. Eng. Mater. Sci. 2020, 10, 25015–25018. [Google Scholar]

- Zakaria, M.; Ahmed, M.; Hoque, M.; Islam, S. Scope of using jute fibre for the reinforcement of concrete materiál. Text. Cloth. Sustain. 2017, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.D.A.A.; Ronghui, W.; Huseien, G.F. Mechanical Properties of Natural Jute Fibre-Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete: Effects of Various Lengths and Volume Fractions. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.K.; Raza, A.; Hussain, U.; Rahman, M.L.; Nazari, S.; Chandan, V.; Muller, M.; Choteborsky, R. Natural Cellulosic Fibre Reinforced Concrete: Influence of Fibre Type and Loading Percentage on Mechanical and Water Absorption Performance. Materials 2022, 15, 874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciel, L.P.; Leão Júnior, P.S.B.; Pereira Filho, M.J.M.; El Banna, W.R.; Fujiyama, R.T.; Ferreira, M.P.; Lima Neto, A.F. Experimental Analysis of Shear-Strengthened RC Beams with Jute and Jute–Glass Hybrid FRPs Using the EBR Technique. Buildings 2024, 14, 2893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, A.; Ali, M. Optimization of Hybrid Fibre-Reinforced Concrete for Controlling Defects in Canal Lining. Materials 2024, 17, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, V.; Militky, J.; Davies, L.; Slater, S. Thermal and water vapor transmission through porous warp knitted 3D spacer fabrics for car upholstery applications. J. Text. Inst. 2017, 109, 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurda, R. Effect of Silica Fume on Engineering Performance and Life Cycle Impact of Jute-Fibre-Reinforced Concrete. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, S.; Ivanova, T.A.; Mishra, R.K.; Müller, M.; Akhbari, M.; Hashjin, Z.E. Effect of Natural Fibre and Biomass on Acoustic Performance of 3D Hybrid Fabric-Reinforced Composite Panels. Materials 2024, 17, 5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.O.J.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Lima, P.R.L. Comparative Analysis of Sisal–Cement Composite Properties After Chemical and Thermal Fibre Treatments. Fibres 2025, 13, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palizzolo, L.; Sanfilippo, C.; Ullah, S.; Benfratello, S. Strengthening of Masonry Structures by Sisal-Reinforced Geopolymers. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shcherban’, E.M.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Meskhi, B.; Efremenko, I.; Shilov, A.A.; Vialikov, I.; Ananova, O.; Chernil’nik, A.; Elshaeva, D. Composition, Structure and Properties of Geopolymer Concrete Dispersedly Reinforced with Sisal Fibre. Buildings 2024, 14, 2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- dos Santos, D.O.J.; Lima, P.R.L.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Flexural Behavior of Lightweight Sandwich Panels with Rice Husk Bio-Aggregate Concrete Core and Sisal Fibre-Reinforced Foamed Cementitious Faces. Materials 2025, 18, 1850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbehiry, A.; Elnawawy, O.; Kassem, M.; Zaher, A.; Uddin, N.; Mostafa, M. Performance of concrete beams reinforced using banana fibre bars. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandramouli, K.; Pannirselvam, N.; NagaSaiPardhu, D.V.V.; Anitha, V. Experimental investigation on banana fibre reinforced concrete with conventional concrete. Int. J. Recent. Technol. Eng. 2019, 7, 874–876. [Google Scholar]

- Stel’makh, S.A.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Beskopylny, A.N.; Chernilnik, A.; Elshaeva, D. Eco-Friendly Concrete with Improved Properties and Structure, Modified with Banana Leaf Ash. J. Compos. Sci. 2024, 8, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilien, V.P.; Promentilla, M.A.B.; Leaño, J.L., Jr.; Oreta, A.W.C.; Ongpeng, J.M.C. Confinement of Concrete Using Banana Geotextile-Reinforced Geopolymer Mortar. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Massri, G.; Ghanem, H.; Khatib, J.; El-Zahab, S.; Elkordi, A. The Effect of Adding Banana Fibres on the Physical and Mechanical Properties of Mortar for Paving Block Applications. Ceramics 2024, 7, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, A.A. Flexural behavior and analysis of reinforced concrete beams made of recycled PET waste concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 155, 593–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, S.; Aparna, A.V. Strength Characteristic Study of Polyester Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Int. J. Engg. Res. Tech. (IJERT) 2018, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Kapkowski, M.; Kotowicz, S.; Kocot, K.; Korzec, M.; Kubacki, J.; Zubko, M.; Aniołek, K.; Siudyga, U.; Siudyga, T.; Polanski, J. From Recycled Polyethylene Terephthalate Waste to High-Value Chemicals and Materials: A Zero-Waste Technology Approach. Energies 2025, 18, 4375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haibe, A.A.; Vemuganti, S. Flexural Response Comparison of Nylon-Based 3D-Printed Glass Fibre Composites and Epoxy-Based Conventional Glass Fibre Composites in Cementitious and Polymer Concretes. Polymers 2025, 17, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazid, M.H.; Faris, M.A.; Abdullah, M.M.A.B.; Ibrahim, M.S.I.; Razak, R.A.; Burduhos Nergis, D.D.; Burduhos Nergis, D.P.; Benjeddou, O.; Nguyen, K.-S. Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer Concrete Incorporation Nylon66 Fibre. Materials 2022, 15, 9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, S.; Ishaq, M.A.A.; Kazmi, S.M.S.; Munir, M.J.; Ali, S. Investigating the Behavior of Waste Alumina Powder and Nylon Fibres for Eco-Friendly Production of Self-Compacting Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Shang, S.; Zhou, H.; Jiang, C.; Huai, H.; Xu, Z. Experimental and Numerical Study on Uniaxial Compression Failure of Concrete Confined by Nylon Ties. Materials 2022, 15, 2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abduallah, R.; Burris, L.; Castro, J.; Sezen, H. Utilization of Different Types of Plastics in Concrete Mixtures. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahish, H.A.; Alkharisi, M.K. Predicting the Properties of Polypropylene Fibre Recycled Aggregate Concrete Using Response Surface Methodology and Machine Learning. Buildings 2025, 15, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Tai, H.-W.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Su, T.; Liu, J. Frost Resistance and Life Prediction of Waste Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Coatings 2025, 15, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, L.; Lin, Z.; Xu, C.; Xu, H.; Li, B.; Shen, J. Study on the Hybrid Effect of Basalt and Polypropylene Fibres on the Mechanical Properties of Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.; Li, P.; Tang, X.; Xiong, G. Numerical Analysis of Impact Resistance of Prefabricated Polypropylene Fibre-Reinforced Concrete Sandwich Wall Panels. Buildings 2025, 15, 3015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haigh, R. A Life Cycle Assessment of HDPE Plastic Milk Bottle Waste Within Concrete Composites and Their Potential in Residential Building and Construction Applications. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.M.; Patro, S.K.; Basarkar, S.S. Mechanical and Post-Cracking Performance of Recycled High Density Polyethylene Fibre Reinforced Concrete. J. Inst. Eng. (India) Ser. A Springer India 2022, 103, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiersnowska, A.; Koda, E.; Fabianowski, W.; Kawalec, J. Effect of the Impact of Chemical and Environmental Factors on the Durability of the High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) Geogrid in a Sanitary Landfill. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkraidi, A.A.J.; Ghani, R.; Ksdhim, A.H.; Alasadi, A.M. Mechanical properties of highdensity polyethylene fibre concrete. Int. J. Civil. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 334–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandhania, V.A.; Sawant, S. Coir Fibre Reinforced Concrete. J. Text. Sci. Eng. 2014, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooqi, M.U.; Ali, M. Effect of Fibre Content on Compressive Strength of Wheat Straw Reinforced Concrete for Pavement Applications. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 422, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjitham, M.; Mohanraj, S.; Ajithpandi, K.; Akileswaran, S.; Deepika Sree, S.K. Strength properties of coconut fibre reinforced concrete. AIP Conf. Proc. 2019, 2128, 020005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalley, P.P.; Kwan, A.S.K. Use of Coconut Fibres as an Enhancement of Concrete. Cardiff University. 2005. Available online: https://orca.cardiff.ac.uk/id/eprint/43403/1/Yalley%20Kwan%20KNUST%20paper%20.%201.pdf (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Ali, M.; Liu, A.; Sou, H.; Chouw, N. Mechanical and dynamic properties of coconut fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 30, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Abdalla, J.A.; Hawileh, R.A.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Corrosion Inhibition in Concrete: Synergistic Performance of Hybrid Steel-Polypropylene Fibre Reinforcement Against Marine Salt Spray. Polymers 2025, 17, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Li, X.; Li, C.; Zhao, J.; Cheng, S. Mechanical Properties of Fully Recycled Aggregate Concrete Reinforced with Steel Fibre and Polypropylene Fibre. Materials 2024, 17, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Xue, X.; Hou, D.; Li, W.; Han, H.; Han, Y. Effect of Polyethylene and Steel Fibres on the Fracture Behavior of Coral Sand Ultra-High Performance Concrete. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeybek, Ö.; Özkılıç, Y.O.; Çelik, A.; Deifalla, A.F.; Ahmad, M.; Sabri, S.M.M. Performance evaluation of fibre-reinforced concrete produced with steel fibres extracted from waste tire. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 1057128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Wang, B.; Liu, C.; Hui, D.; Xu, Q.; Zhao, Q.; Wei, J.; Hong, X. Experimental study on basic mechanical properties of recycled steel fibre reinforced concrete. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2022, 61, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, M.; Akbar, A.; Mohamed, A.M.; Fathi, D.; Saeed, F. Recycling of Waste Facial Masks as a Construction Material, a Step towards Sustainability. Materials 2022, 15, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koniorczyk, M.; Bednarska, D.; Masek, A.; Cichosz, S. Performance of concrete containing recycled masks used for personal protection during coronavirus pandemic. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 324, 126712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilmartin-Lynch, S.; Saberian, S.; Li, J.; Roychand, R.; Zhang, G. Preliminary evaluation of the feasibility of using polypropylene fibres from COVID-19 single-use face masks to improve the mechanical properties of concrete. , J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 296, 126460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, H.; Mao, S.; Wang, L.; Deng, Z. Influence of Steel Fibre and Rebar Ratio on the Flexural Performance of UHPC T-Beams. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.; Zuaiter, H.; ElMaoued, D.; Tamimi, A.; AlHamaydeh, M. Mechanical Properties Quantification of Steel Fibre-Reinforced Geopolymer Concrete with Slag and Fly Ash. Buildings 2025, 15, 3533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dziomdziora, P.; Smarzewski, P. Reinforced Concrete Beams with FRP and Hybrid Steel–FRP Composite Bars: Load–Deflection Response, Failure Mechanisms, and Design Implications. Materials 2025, 18, 4381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, C.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Shi, J.; Mao, W.; Xing, S.; Chen, J.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J. Performance Analysis of Stainless Steel Fibre Recycled Aggregate Concrete Under Dry and Wet Cycles Based on Response Surface Methodology. Coatings 2025, 15, 1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, Q.; Xu, Z.; Chen, W.; Zhang, H.; Liu, S.; Yuan, Z. Shear–Flexural Performance of Steel Fibre-Reinforced Concrete Composite Beams: Experimental Investigation and Modeling. Materials 2025, 18, 4322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birol, T.; Aygen, A.; Yavaş, A. Effect of Steel Fibre Hybridization on the Shear Behavior of UHPC I-Beams. Buildings 2025, 15, 3335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinelli, F.R.B.; Ribeiro, F.R.C.; Marvila, M.T.; Monteiro, S.N.; Filho, F.d.C.G.; Azevedo, A.R.G.D. A Review of the Use of Coconut Fibre in Cement Composites. Polymers 2023, 15, 1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.K.; Singh, A. An Experimental Study on Coconut Fibre Reinforced Concrete. Int. Res. J. Eng. Technol. (IRJET) 2019, 6, 2250–2254. [Google Scholar]

- Satheesh Kumar, S.; Murugesan, R.; Sivaraja, M.; Athijayamani, A. Innovative Eco-Friendly Concrete Utilizing Coconut Shell Fibres and Coir Pith Ash for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katman, H.Y.B.; Khai, W.J.; Bheel, N.; Kırgız, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Benjeddou, O. Fabrication and Characterization of Cement-Based Hybrid Concrete Containing Coir Fibre for Advancing Concrete Construction. Buildings 2022, 12, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Ahmad, W.; Alaboud, T.M.; Zia, A.; Akmal, U.; Awad, Y.A.; Alabduljabbar, H. Scientometric Analysis and Research Mapping Knowledge of Coconut Fibres in Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 5639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaguaña, M.; Guamán, L.; Gómez, N.B.Y.; Khorami, M.; Calvo, M.; Albuja-Sánchez, J. Test Method for Studying the Shrinkage Effect under Controlled Environmental Conditions for Concrete Reinforced with Coconut Fibres. Materials 2023, 16, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hussien, N.T.; Oan, A.F. The use of sugarcane wastes in concrete. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2022, 69, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikh Khalid, F.; Herman, H.S.; Azmi, N.B. Properties of Sugarcane Fibre on the Strength of the Normal and Lightweight Concrete. MATEC Web Conf. 2017, 103, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihan, M.A.M.; Alahmari, T.S.; Onchiri, R.O.; Gathimba, N.; Sabuni, B. Impact of Alkaline Concentration on the Mechanical Properties of Geopolymer Concrete Made up of Fly Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Wang, Y.; Fu, T.; Easa, S.M.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H. Mechanical, Electrical, and Tensile Self-Sensing Properties of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete Enhanced with Sugarcane Bagasse Ash. Materials 2024, 17, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zúniga, A.; Eires, R.; Malheiro, R. New Lime-Based Hybrid Composite of Sugarcane Bagasse and Hemp as Aggregates. Resources 2023, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, P.P.L.d.; Eires, R.; Malheiro, R. Sugarcane Bagasse as Aggregate in Composites for Building Blocks. Energies 2023, 16, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Javed, U.; Shah, M.I.; Hanif, A. Use of Processed Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in Concrete as Partial Replacement of Cement: Mechanical and Durability Properties. Buildings 2022, 12, 1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhath, N.; Kumara, B.S.; Vithanage, V.; Samarathunga, A.I.; Sewwandi, N.; Maduwantha, K.; Madusanka, M.; Koswattage, K. A Review on the Optimization of the Mechanical Properties of Sugarcane-Bagasse-Ash-Integrated Concretes. J. Compos. Sci. 2022, 6, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-said, A.; Awad, A.; Ahmad, M.; Sabri, M.M.S.; Deifalla, A.F.; Tawfik, M. The Mechanical Behavior of Sustainable Concrete Using Raw and Processed Sugarcane Bagasse Ash. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrant, W.E.; Babafemi, A.J.; Kolawole, J.T.; Panda, B. Influence of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash and Silica Fume on the Mechanical and Durability Properties of Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastin, S.; Priya, A.K.; Karthick, A.; Sathyamurthy, R.; Ghosh, A. Agro Waste Sugarcane Bagasse as a Cementitious Material for Reactive Powder Concrete. Clean. Technol. 2020, 2, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albadrani, M.A. Strength Development of PPC Concrete with Rice Husk Ash: Optimal Replacement Levels for Sustainable Construction. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.J.; Miah, M.S.; Mughal, H.; Hasan, N.M.S. Mitigating Environmental Impact Through the Use of Rice Husk Ash in Sustainable Concrete: Experimental Study, Numerical Modelling, and Optimisation. Materials 2025, 18, 3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Gao, S.; Xu, J.; Wang, L.; Xu, M.; Ying, H. Sustainable Strategy to Reduce Winter Energy Consumption: Incorporating PCM Aggregates and Rice Husk Ash–Fly Ash Matrix into Concrete. Buildings 2025, 15, 2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Xing, Y.; Deng, W.; Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Mao, Z. Effect of Combined MgO Expansive Agent and Rice Husk Ash on Deformation and Strength of Post-Cast Concrete. Materials 2025, 18, 2815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xavier, V.H.C.; Salles, A.M.d.S.L.d.M.; Meneghetti, E.M.; Maeda, G.H.H.; Sousa, A.M.D.d.; Félix, E.F.; Prado, L.P. Experimental and Numerical Analyses on the Flexural Tensile Strength of Ultra-High-Performance Concrete Prisms with and Without Rice Husk Ash. Buildings 2025, 15, 1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeshiwas, M.D.; Yehualaw, M.D.; Habtegebreal, B.T.; Nebiyu, W.M.; Taffese, W.Z. Rice Husk Ash and Waste Marble Powder as Alternative Materials for Cement. Infrastructures 2025, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, A.F.d.; Caldas, L.R.; Hasparyk, N.P.; Toledo Filho, R.D. Low-Carbon Bio-Concretes with Wood, Bamboo, and Rice Husk Aggregates: Life Cycle Assessment for Sustainable Wall Systems. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; He, C.; Xu, W. The Influence of Rice Husk Ash Incorporation on the Properties of Cement-Based Materials. Materials 2025, 18, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaed, M.M.; Al Mufti, R.L. The Effects of Rice Husk Ash as Bio-Cementitious Material in Concrete. Constr. Mater. 2024, 4, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zareei, S.A.; Ameri, F.; Dorostkar, F.; Ahmadi, M. Rice husk ash as a partial replacement of cement in high strength concrete containing micro silica: Evaluating durability and mechanical properties. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2017, 7, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.R.; Singh, D. Effect of Rice Husk Ash on Compressive Strength of Concrete. Int. J. Struct. Civ. Eng. Res. 2019, 8, 223–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastías, B.; González, M.; Rey-Rey, J.; Valerio, G.; Guindos, P. Sustainable Cement Paste Development Using Wheat Straw Ash and Silica Fume Replacement Model. Sustainability 2024, 16, 11226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ishfaq, M.; Amin, M.N.; Shahzada, K.; Wahab, N.; Faraz, M.I. Evaluation of Mechanical and Microstructural Properties and Global Warming Potential of Green Concrete with Wheat Straw Ash and Silica Fume. Materials 2022, 15, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amin, M.N.; Siffat, M.A.; Shahzada, K.; Khan, K. Influence of Fineness of Wheat Straw Ash on Autogenous Shrinkage and Mechanical Properties of Green Concrete. Crystals 2022, 12, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Javed, U.; Haris, M.; Khushnood, R.A.; Kim, J. Incorporation of Wheat Straw Ash as Partial Sand Replacement for Production of Eco-Friendly Concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 2078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.N.; Murtaza, T.; Shahzada, K.; Khan, K.; Adil, M. Pozzolanic Potential and Mechanical Performance of Wheat Straw Ash Incorporated Sustainable Concrete. Sustainability 2019, 11, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Memon, S.A.; Wahid, I.; Khan, M.K.; Tanoli, M.A.; Bimaganbetova, M. Environmentally Friendly Utilization of Wheat Straw Ash in Cement-Based Composites. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katman, H.Y.B.; Khai, W.J.; Bheel, N.; Kırgız, M.S.; Kumar, A.; Khatib, J.; Benjeddou, O. Workability, Strength, Modulus of Elasticity, and Permeability Feature of Wheat Straw Ash-Incorporated Hydraulic Cement Concrete. Buildings 2022, 12, 1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.; Jamshaid, H.; Mishra, R.; Chandan, V.; Jirku, P.; Kolar, V.; Muller, M.; Nazari, S.; Shahzada, K. Optimization of seismic performance in waste fibre reinforced concrete by TOPSIS method. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Meng, K.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, B.; Wei, B. Mechanical properties and stress-strain relationship of surface-treated bamboo fibre reinforced lightweight aggregate concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 424, 135914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joachim, L.; Oettel, V. Experimental Investigations on the Application of Natural Plant Fibres in Ultra-High-Performance Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 3519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Tian, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Z.-w.; Zhang, Z. Preparation and Properties of Natural Bamboo Fibre-Reinforced Recycled Aggregate Concrete. Materials 2024, 17, 2972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, J.N.; Tan, Q.Y.; Lim, K.S.; Gimbun, J.; Tee, K.F.; Chin, S.C. Effective Strengthening of RC Beams Using Bamboo-Fibre-Reinforced Polymer: A Finite-Element Analysis. Fibres 2023, 11, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Qin, G.; Luo, F.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, G.; Yao, S.; Ma, H. Experimental Study and Numerical Analysis on the Shear Resistance of Bamboo Fibre Reinforced Steel-Wire-Mesh BFRP Bar Concrete Beams. Materials 2023, 16, 3446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, C.M.; Oettel, V. Fibre Reinforced Concrete with Natural Plant Fibres—Investigations on the Application of Bamboo Fibres in Ultra-High Performance Concrete. Sustainability 2022, 14, 12011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Costa Santos, A.C.; Archbold, P. Suitability of Surface-Treated Flax and Hemp Fibres for Concrete Reinforcement. Fibres 2022, 10, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.W.; Bai, Y.L.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, J.J. Experimental study on dynamic properties of flax fibre reinforced recycled aggregate concrete. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 80, 108135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouta, N.; Saliba, J.; Saiyouri, N. Fracture behavior of flax fibres reinforced earth concrete. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2021, 241, 107378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwad, E.; Mabsout, M.; Hamad, B.; Farran, M.; Khatib, H. Studies on fibre-reinforced concrete using industrial hemp fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 35, 710–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Properties of hemp fibre reinforced concrete composites. Compos. Part. A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beskopylny, A.N.; Shcherban’, E.M.; Stel’makh, S.A.; Chernilnik, A.; Elshaeva, D.; Ananova, O.; Mailyan, L.D.; Muradyan, V.A. Optimization of the Properties of Eco-Concrete Dispersedly Reinforced with Hemp and Flax Natural Fibres. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Aziz, F.; Abdan, F.; Nasir, N.; Huseien, G. Experimental study on durability properties of kenaf fibre-reinforced geopolymer concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 396, 132160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, V.; Bobko, C.P. Nano-mechanical properties of internally cured kenaf fibre reinforced concrete using nanoindentation. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2014, 52, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsaid, A.; Dawood, M.; Seracino, R.; Bobko, C. Mechanical properties of kenaf fibre reinforced concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2011, 25, 1991–2001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baghban, M.H.; Mahjoub, R. Natural Kenaf Fibre and LC3 Binder for Sustainable Fibre-Reinforced Cementitious Composite: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sr. No. | Fiber | Density (Kg/m3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Glass | 2100 | 1000–3500 | 70–80 | 2.5–3.5 |

| 2 | Basalt | 1560 | 2600–4800 | 79.3–93.1 | 2.0–3.2 |

| 3 | Carbon | 1750 | 3500–7000 | 200–600 | 0.3–2.4 |

| Sr. No | Fiber | Specific Gravity (Kg/m3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jute | 1020–1480 | 490–800 | 10–30 | 1.16–1.93 |

| 2 | Sisal | 1400–1500 | 380–725 | 9.0–22.0 | 2.0–14.0 |

| 3 | Banana | 700–1350 | 150–900 | 27–32 | 0.35–9.54 |

| 4 | Polyester | 1330–1405 | 500–800 | 2.5–10.0 | 13.5–14.3 |

| 5 | Polypropylene | 900–910 | 300–750 | 0.5–3.0 | 15.0–30.0 |

| 6 | Nylon | 1130–1150 | 40–90 | 1.3–4.2 | 15.0–50.0 |

| 7 | High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE) | 940–970 | 23–29.5 | 0.4–2.5 | 600–1350 |

| Sr. No. | Fiber | Density (Kg/m3) | Tensile Strength (MPa) | Elastic Modulus (GPa) | Elongation at Break (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sugarcane bagasse | 120–520 | 60–200 | 18–26 | 1.1–3.5 |

| 2 | Coconut | 1200–1500 | 170–500 | 2–8 | 17–25 |

| 3 | Rice husk | 321–425 | 70–80 | - | - |

| 4 | Wheat straw | 225–450 | 80–90 | - | - |

| 5 | Bamboo | 600–900 | 150–800 | 10–50 | 4.1–9.5 |

| 6 | Flax | 1300–1600 | 800–1500 | 50–150 | 1.2–3.7 |

| 7 | Hemp | 1400–1500 | 350–800 | 20–70 | 1.0–4.2 |

| 8 | Kenaf | 970 | 400–700 | 14–60 | 1.6–5.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mishra, R.K.; Jamshaid, H.; Muller, M.; Urban, J.; Penc, M. Comprehensive Review on Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Fibers and Waste Materials. Materials 2025, 18, 5419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235419

Mishra RK, Jamshaid H, Muller M, Urban J, Penc M. Comprehensive Review on Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Fibers and Waste Materials. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235419

Chicago/Turabian StyleMishra, Rajesh Kumar, Hafsa Jamshaid, Miroslav Muller, Jiri Urban, and Michal Penc. 2025. "Comprehensive Review on Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Fibers and Waste Materials" Materials 18, no. 23: 5419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235419

APA StyleMishra, R. K., Jamshaid, H., Muller, M., Urban, J., & Penc, M. (2025). Comprehensive Review on Mechanical Performance of Concrete Reinforced with Fibers and Waste Materials. Materials, 18(23), 5419. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235419