Multi-Objective Optimization of the Crashworthiness of Aluminum Circular Tubes with Graded Thicknesses

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Mechanistic Property Characterization

2.1. Fundamental Mechanical Characteristics of Thin-Walled Circular Tube

2.2. Crushing Response of Thin-Walled Tube

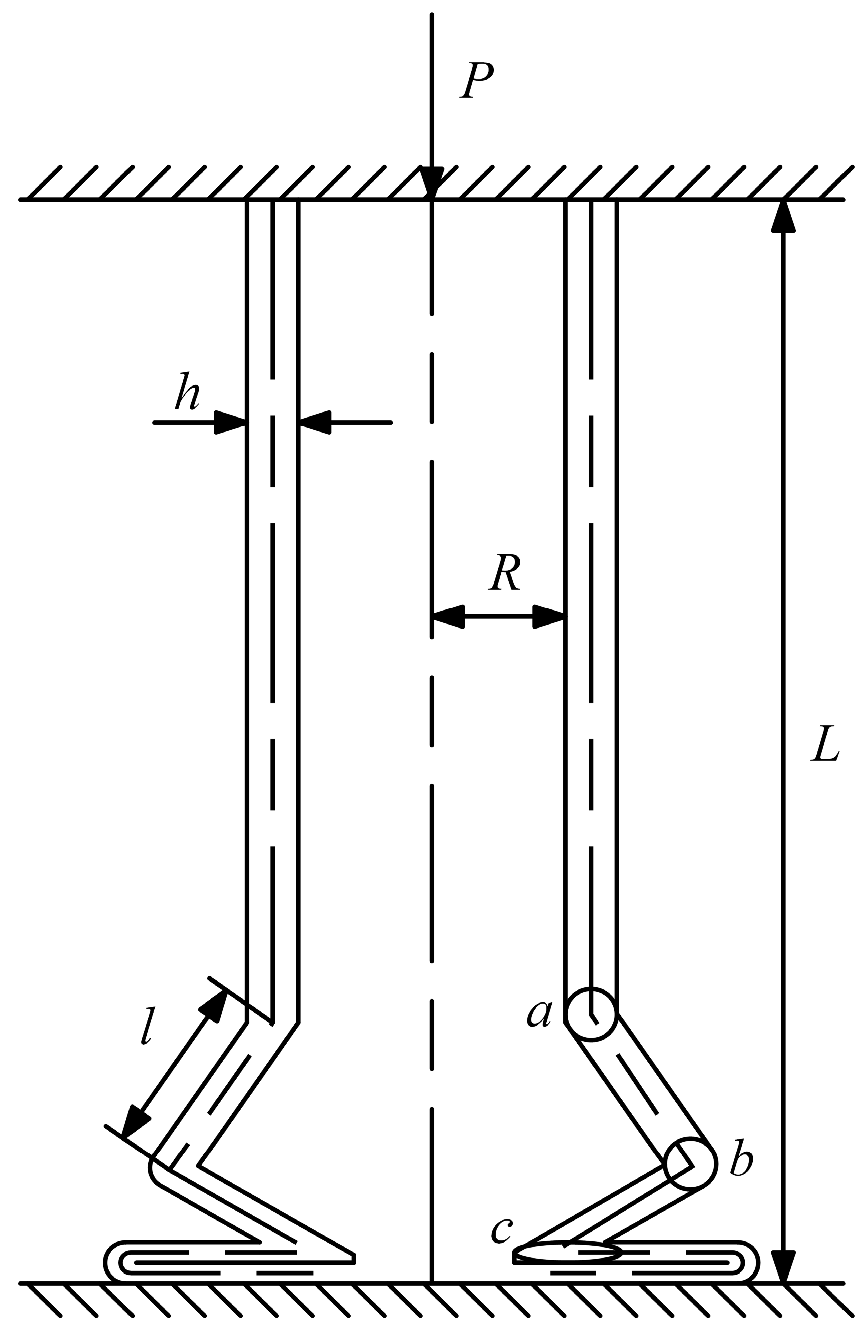

2.2.1. Bending Strain Energy Dissipation Assessment

2.2.2. Tensile Strain Energy Absorption Evaluation

2.3. Energy Absorption Characterization Indicators

3. Finite Element Model

3.1. FE Modeling

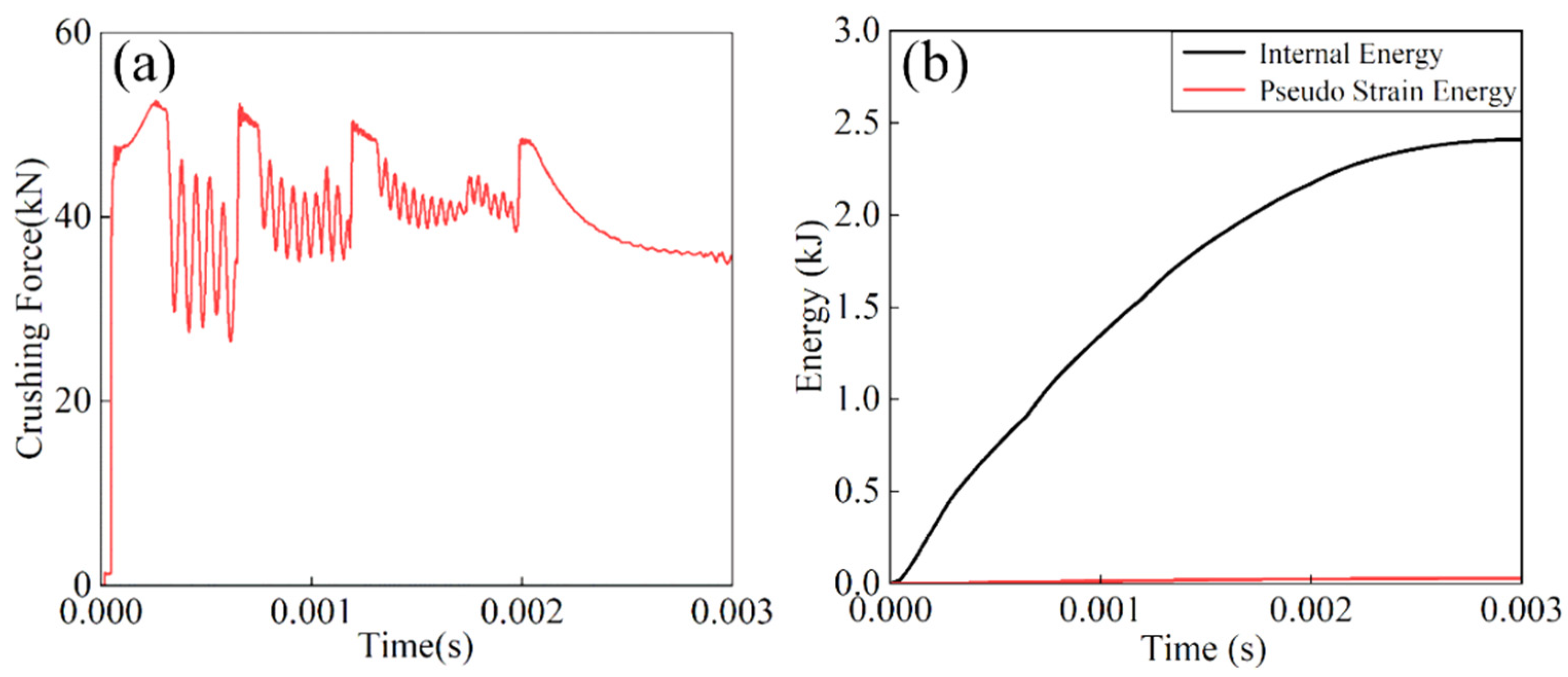

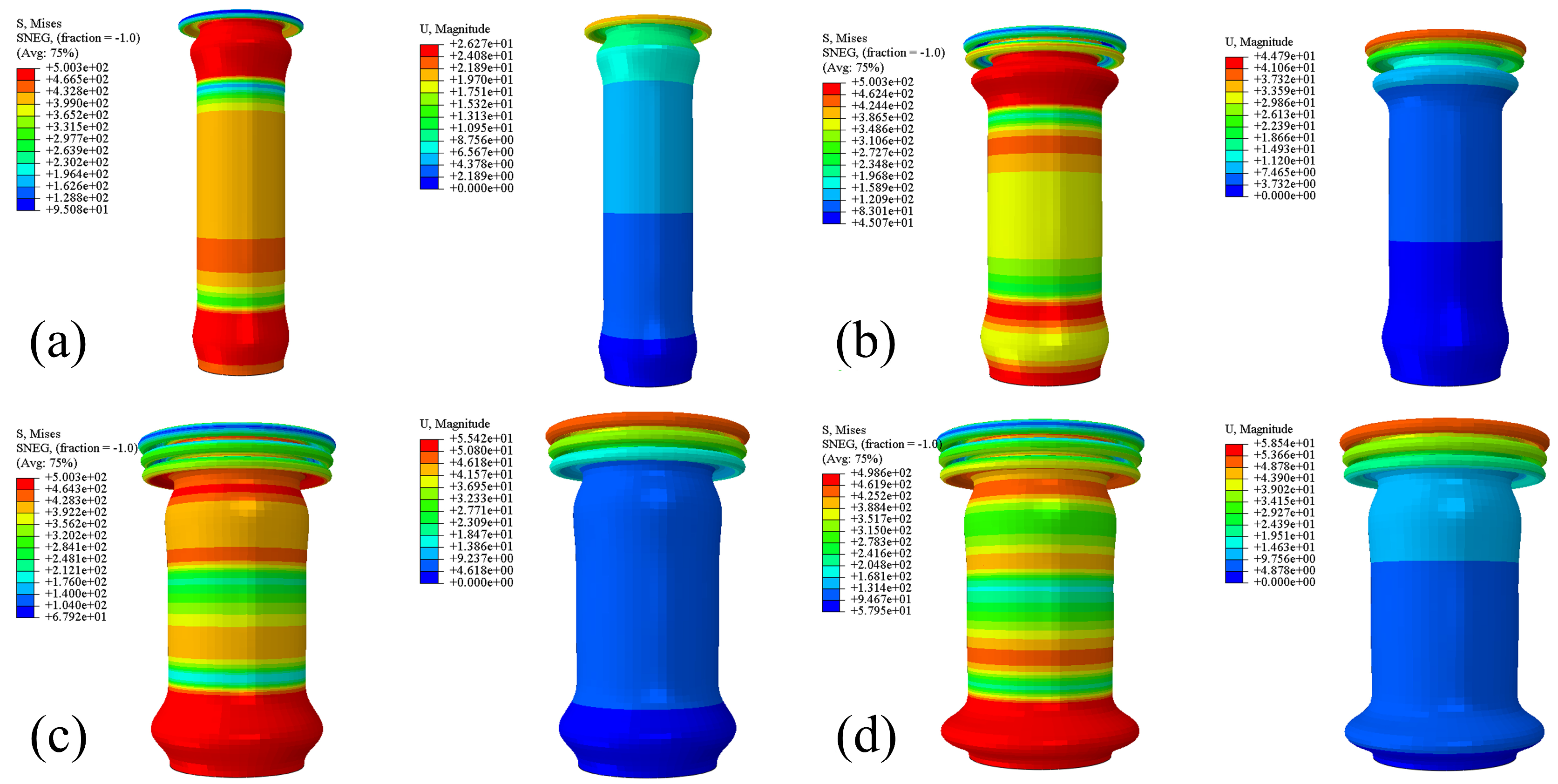

3.2. Numerical Simulation Results and Discussion

4. Experimental Methodology

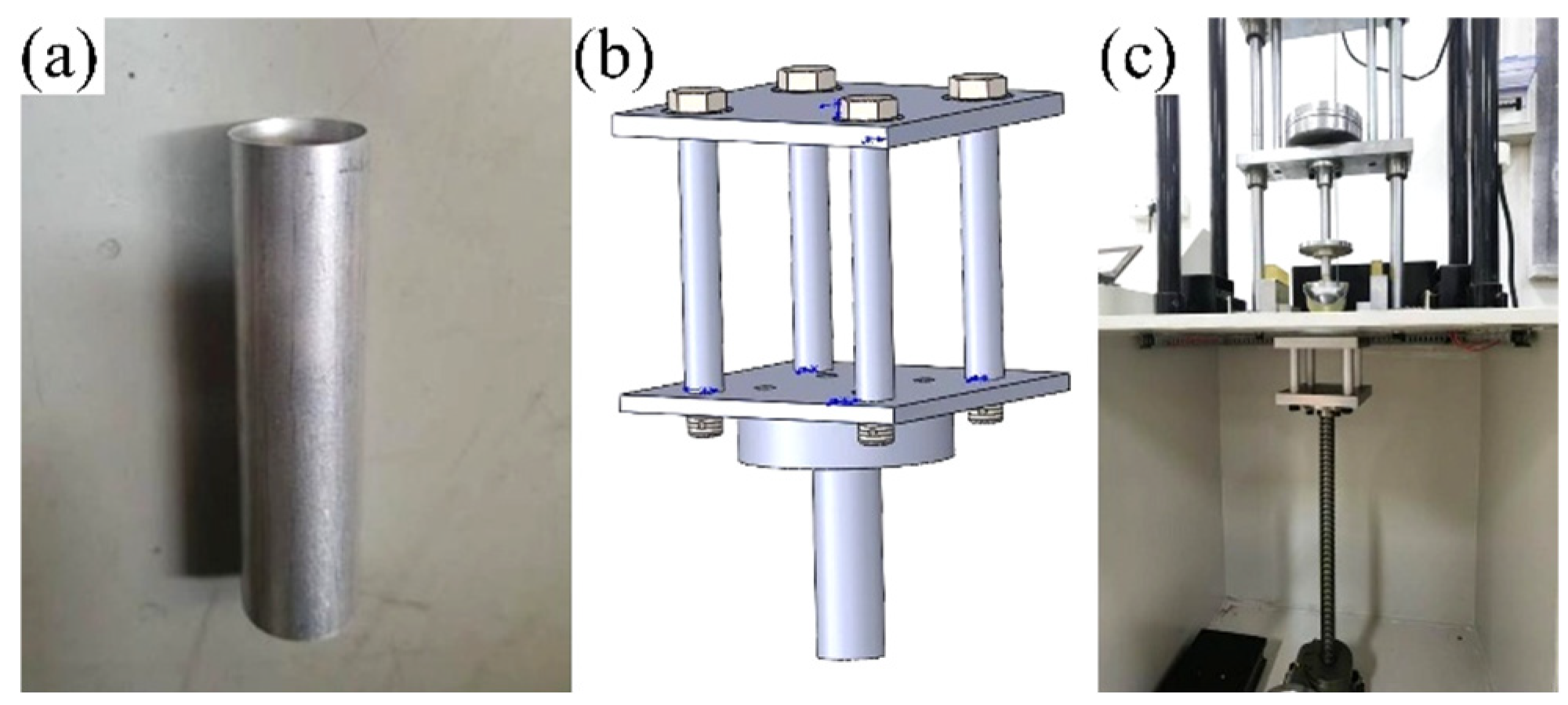

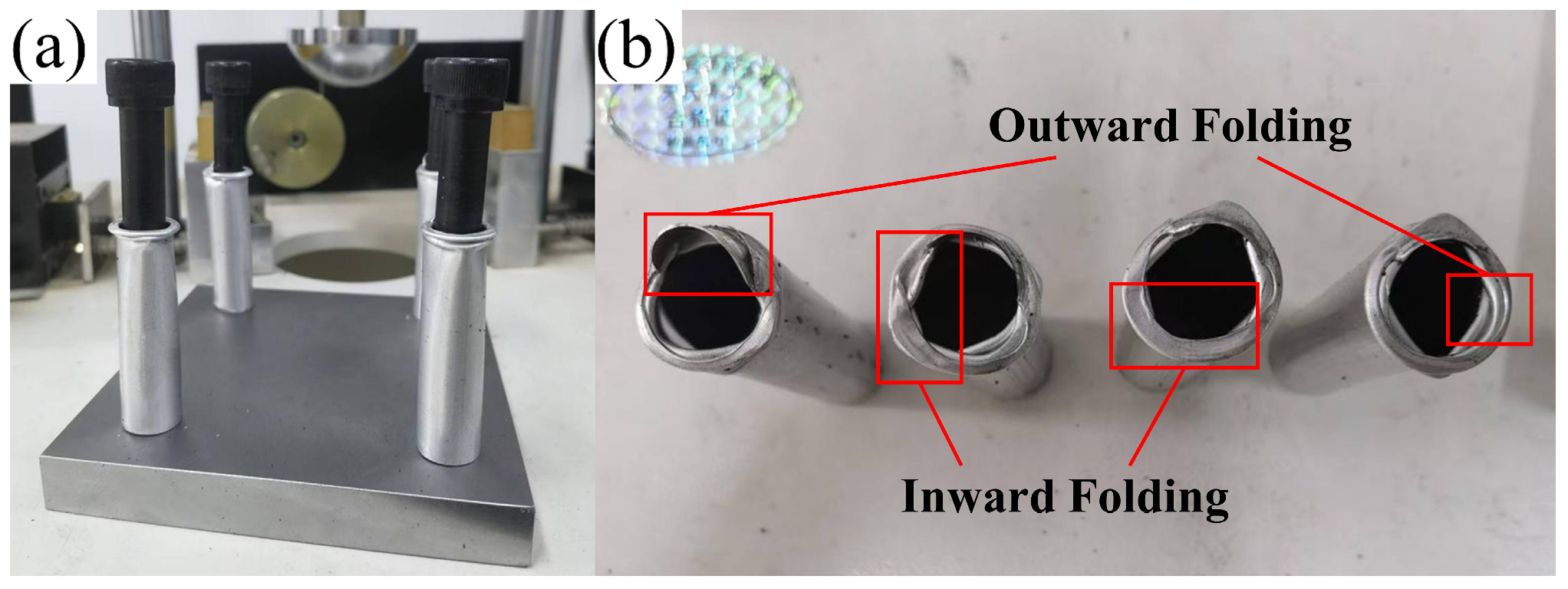

4.1. Experimental Setup and Specimens

4.2. Parameter Settings

4.3. Experimental Procedures

- (1)

- Specimen installation: Four aluminum thin-walled tubes were securely clamped between two steel plates of the test fixture. Each tube was constrained by partially threaded studs, which served to control deformation direction during impact. The tube-contacting sections of the studs maintained smooth cylindrical surfaces, while the threaded portions were firmly tightened into the steel plates for fixation.

- (2)

- Fixture mounting: The fixed end of the steel plate assembly was rigidly attached to the impact platform. The platform height was carefully adjusted to ensure proper alignment.

- (3)

- The electro-controlled impactor was programmed to ascend to the predetermined test height and maintain position until release.

- (4)

- Upon activation, the impactor was released to impact the upper surface of the steel plate assembly, transmitting the dynamic load to the tubular specimens.

- (5)

- The drop hammer height was adjusted, and the fixture was removed to inspect the crushing condition of thin-walled circular tubes.

- (6)

- The deformation characteristics of specimens were systematically examined and documented.

4.4. Analysis of Results

- (1)

- Although the four specimens were cut from the same batch of material, inherent manufacturing variations may have introduced slight dimensional or geometric inconsistencies that affected their deformation behavior.

- (2)

- The actual material properties (including density, elastic modulus, and strength) may exhibit spatial variations in the physical specimens, whereas the simulation assumes perfectly homogeneous material characteristics.

- (3)

- Manufacturing processes such as forming, heat treatment, or machining could induce residual stresses in the specimens, leading to mechanical responses that deviate from the idealized assumptions in simulations.

- (4)

- Imperfections in edge finishing (such as burrs or chamfering quality) may influence stress concentration behavior, while the simulation model assumes geometrically perfect boundaries.

- (5)

- Micro-scale surface roughness or irregularities present in actual specimens, which are typically neglected in the idealized geometric models used for simulation.

- (6)

- Potential misalignment between the impact center and the geometric symmetry axis of the four-tube assembly could lead to uneven load distribution during the impact event.

5. Optimization Design of Graded-Thickness Thin-Walled Al Circular Tubes

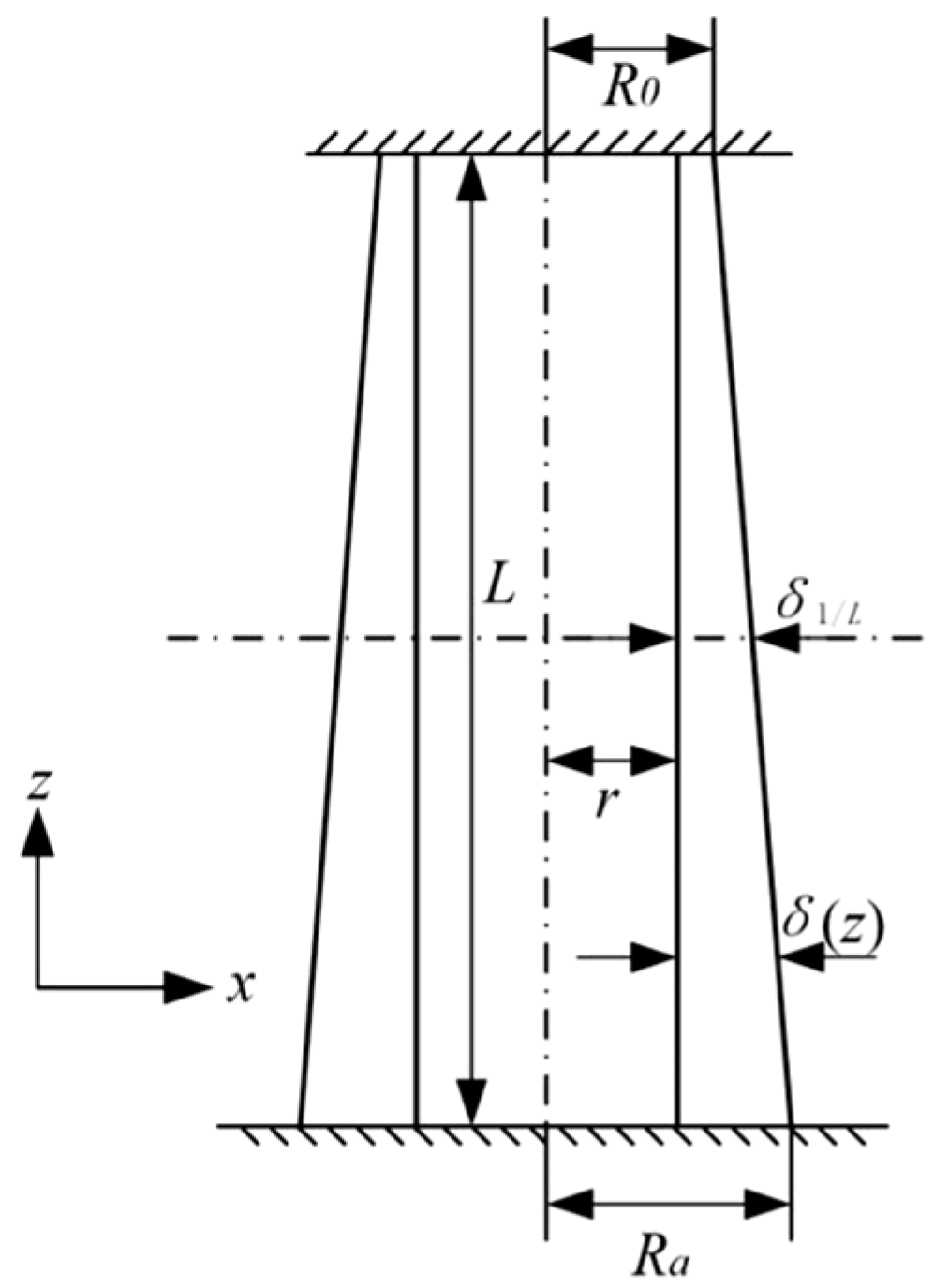

5.1. Parametric Modeling of Graded-Thickness Thin-Walled Al Circular Tubes

5.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Based on a Novel Optimization Algorithm

5.2.1. Basic Concepts of Multi-Objective Optimization Problems

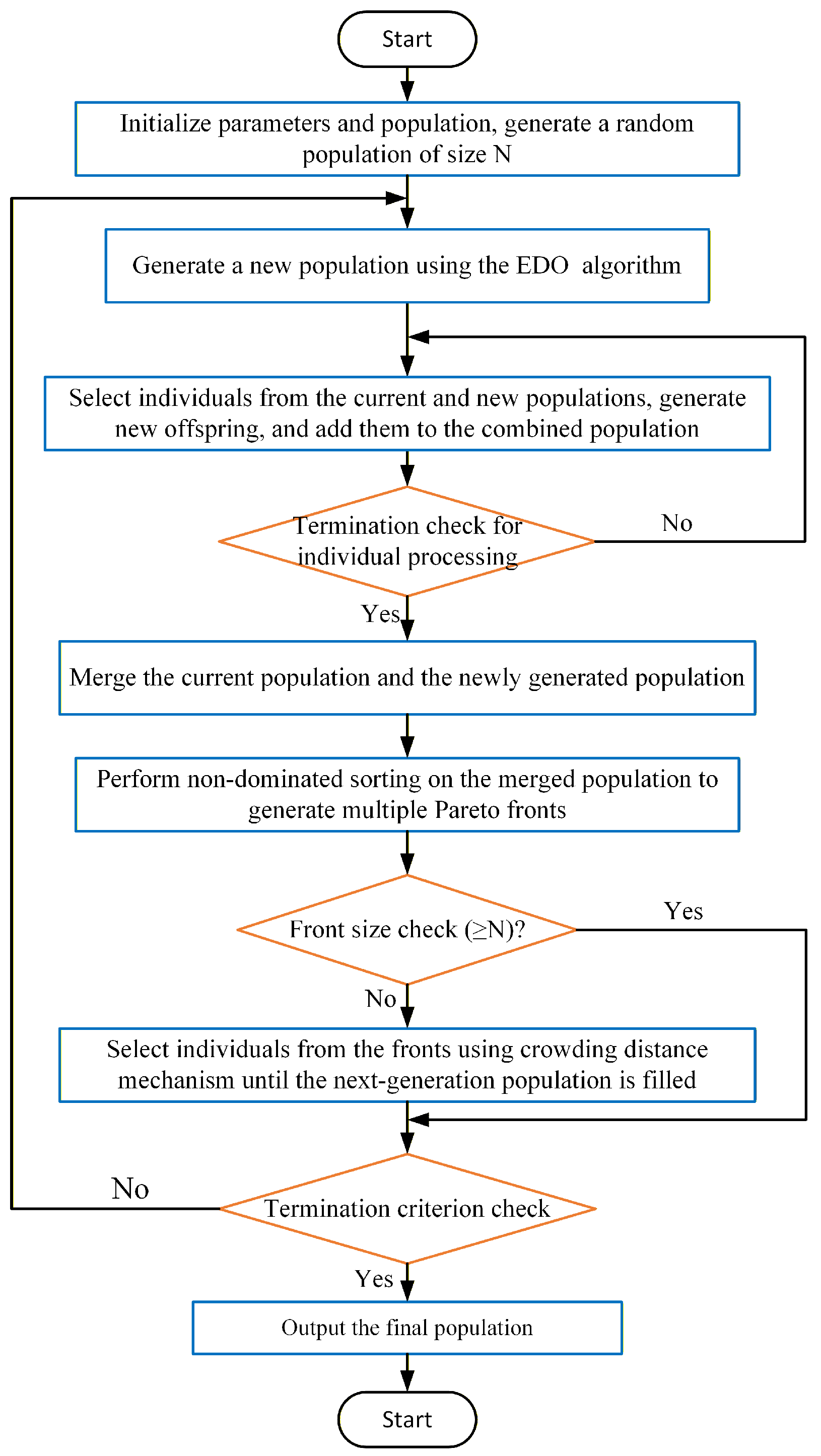

5.2.2. EDO Algorithm and MOEDO Algorithm

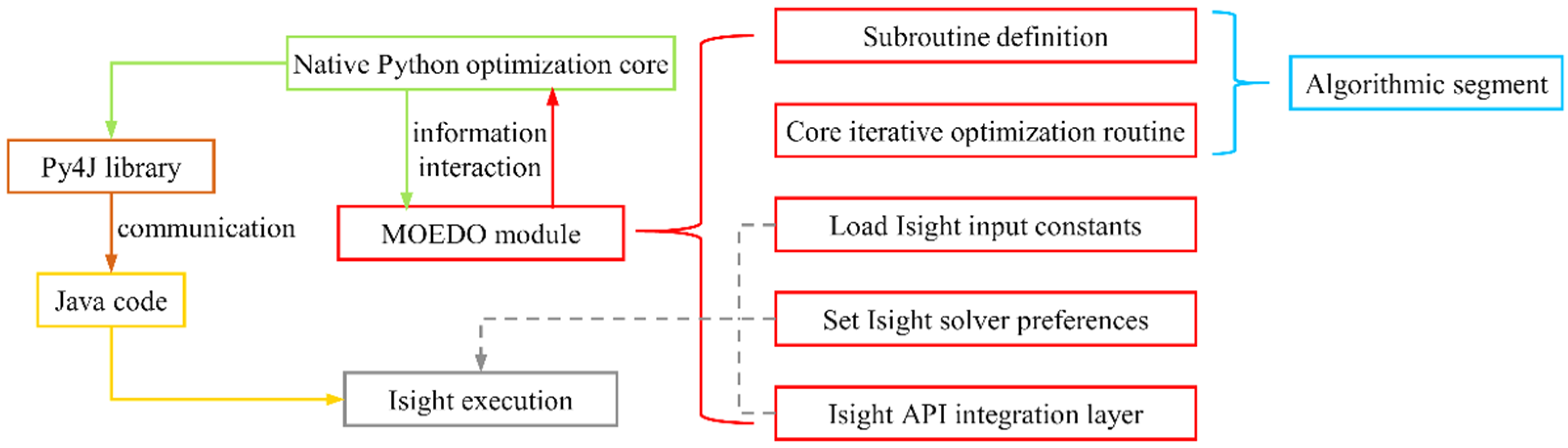

5.2.3. Interface of the MOEDO Algorithm

5.2.4. Engineering Problem Tests

5.3. Multi-Objective Optimization Scheme

5.3.1. Optimization Process

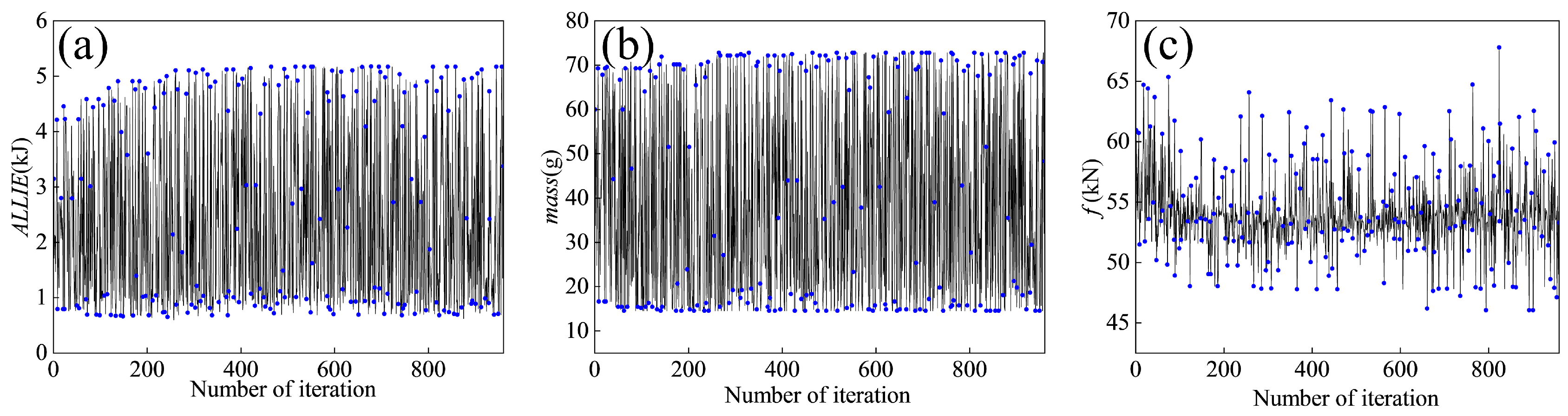

5.3.2. Optimization Results

6. Conclusions and Outlook

- (1)

- The occurrence of concertina lobes at the impact end can better absorb impact energy and prevent structural instability.

- (2)

- The 7050Al thin-walled tube exhibits excellent energy absorption characteristics under realistic crushing conditions. The experimental results validate the computational crushing model and confirm the structure’s suitability for use as a buffer structure in subsequent research.

- (3)

- The proposed methodology demonstrates improved computational efficiency and solution quality compared to conventional optimization approaches, providing an effective tool for the design of energy-absorbing structures with tailored performance characteristics.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gan, N.; Feng, Y.; Yin, H.; Wen, G.; Wang, D.; Huang, X. Quasi-static axial crushing experiment study of foam-filled CFRP and aluminum alloy thin-walled structures. Compos. Struct. 2016, 157, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikkhah, H.; Baroutaji, A.; Olabi, A.G. Crashworthiness design and optimisation of windowed tubes under axial impact loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 142, 132–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Hou, Y.; Yan, X. A bionic tree-liked fractal structure as energy absorber under axial loading. Eng. Struct. 2021, 245, 112914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, B.; Gao, W.; Xie, Z.; Pasini, D.; Tan, H. Thin-walled tubular structures integrating origami patterns and tension-dominated bulkheads for enhanced energy absorption. Thin-Walled Struct. 2025, 215, 113433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremanzadeh, Z.; Pirmohammad, S. Crashworthiness performance of square, pentagonal, and hexagonal thin-walled structures with a new sectional design. Mech. Adv. Mater. Struct. 2023, 30, 2353–2370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nia, A.A.; Hamedani, J.H. Comparative analysis of energy absorption and deformations of thin walled tubes with various section geometries. Thin-Walled Struct. 2010, 48, 946–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Shen, C.; Zhang, J.; Zheng, D.; Zhang, T. Study on energy absorption performance of variable thickness CFRP/aluminum hybrid square tubes under axial loading. Compos. Struct. 2021, 276, 114469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Meng, C.; Chong, Q.; Chen, L.; Guo, Y. Crushing behavior of biomimetic hierarchical multi-cell thin-walled tubes under multi-angle loading. Eng. Struct. 2025, 331, 119996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Xiao, J. Crashworthiness Design and Multi-Objective Optimization of Bionic Thin-Walled Hybrid Tube Structures. Cmes-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2024, 139, 999–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.F.; Zhong, J.L.; Wang, H.X.; Liu, C.; Li, M.; Liu, H. Impact behaviour and protection performance of a CFRP NPR skeleton filled with aluminum foam. Mater. Des. 2024, 246, 113295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acar, E.; Guler, M.A.; Gerçeker, B.; Cerit, M.E.; Bayram, B. Multi-objective crashworthiness optimization of tapered thin-walled tubes with axisymmetric indentations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2011, 49, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhatib, S.E.; Matar, M.S.; Tarlochan, F.; Laban, O.; Mohamed, A.S.; Alqwasmi, N. Deformation modes and crashworthiness energy absorption of sinusoidally corrugated tubes manufactured by direct metal laser sintering. Eng. Struct. 2019, 201, 109838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, F.; Jin, Y. Crashworthiness analysis and structural optimization of thin-walled circular tubes with porous arrays. Structures 2024, 70, 107811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wen, G.; Zhao, S.; Liu, J.; Kitipornchai, S.; Yang, J. Energy absorption of graded thin-walled origami tubes. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2024, 282, 109609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, F.; Shen, K.; Gong, Q. Energy absorption of variable stiffness composite thin-walled tubes on axial impacting. Compos. Part C Open Access 2023, 12, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinpour, E.; Goudarzi, A.M.; Morshedsolouk, F.; Gharehbaghi, H. Numerical and experimental study on the energy absorption characteristics of thin-walled auxetic cylindrical tubes with varying porosity. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 39, 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Meng, Z.; Yi, J.; Chen, C.Q. Auxetic metamaterials with double re-entrant configuration. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2025, 301, 110505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, N.; Tian, Y.-L.; Shu, Y.-Q.; Zhang, H.-R.; Huang, T.; Wang, P.-Y.; Zhang, R.; Sun, W.-T.; Cheng, F.-Y. Pseudo-bulk forming of thin-walled hollow components based on the self-consistency of internal pressure and shell deformation. Mater. Des. 2025, 259, 114865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, H. A review on functionally graded structures and materials for energy absorption. Eng. Struct. 2018, 171, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gao, Z.; Ruan, D. Square tubes with graded wall thickness under oblique crushing. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 183, 110429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Xu, F.; Sun, G.; Li, Q. A comparative study on thin-walled structures with functionally graded thickness (FGT) and tapered tubes withstanding oblique impact loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2015, 77, 68–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigdeli, A.; Nouri, M.D. A crushing analysis and multi-objective optimization of thin-walled five-cell structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2019, 137, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, C.; Yang, S.; Dong, F. Crushing analysis and multiobjective crashworthiness optimization of tapered square tubes under oblique impact loading. Thin-Walled Struct. 2012, 59, 103–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Xu, G.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, J.; Gao, Y. Multi-objective design optimization using hybrid search algorithms with interval uncertainty for thin-walled structures. Thin-Walled Struct. 2022, 175, 109218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Yang, H.; Yang, H.; Li, G.-J. Sequential multi-objective optimization of thin-walled aluminum alloy tube bending under various uncertainties. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2017, 27, 608–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanjarani, A.; Dibajian, S.H.; Mahdian, A. Multi-objective crashworthiness optimization of tapered thin-walled square tubes with indentations. Thin-Walled Struct. 2017, 116, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arjomandi Rad, M.; Khalkhali, A. Crashworthiness multi-objective optimization of the thin-walled tubes under probabilistic 3D oblique load. Mater. Des. 2018, 156, 538–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, C.; Zhao, L.; Hu, N.; Hou, S.; Han, X. Crashworthiness analysis and optimization design of special-shaped thin-walled tubes by experiments and numerical simulation. Thin-Walled Struct. 2024, 205, 112240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Li, Y.; Torrent, D.; Zhuang, X.; Rabczuk, T.; Jin, Y. Machine learning assisted intelligent design of meta structures: A review. Microstructures 2023, 3, 2023037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Liu, S.J.; Wang, J.H.; Zhao, C.F. Energy Absorption Characteristics of CFRP-Aluminum Foam Composite Structure Under High-Velocity Impact: Focusing on Varying Aspect Ratios and Relative Densities. Polymers 2025, 17, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W.B.; Yang, L.M.; Yu, T.X. Study on Dynamic Properties of Thin-walled Circular Tubes under Axial Compression. J. Ningbo Univ. NSEE 2014, 27, 92–96. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, S.; Qi, C. Multiobjective optimization for empty and foam-filled square columns under oblique impact loading. Int. J. Impact Eng. 2013, 54, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, H.; Wen, G.; Fang, H.; Qing, Q.; Kong, X.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Z. Multiobjective crashworthiness optimization design of functionally graded foam-filled tapered tube based on dynamic ensemble metamodel. Mater. Des. 2014, 55, 747–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, M.; Mishra, R.S.; Sankaran, K.K. Structure-property correlations in Al 7050 and Al 7055 high-strength aluminum alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. Mater. Prop. Microstruct. Process. 2008, 478, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, K.; England, G.; Ghani, E. Classification of the axial collapse of cylindrical tubes under quasi-static loading. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 1983, 25, 687–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, F.; Fu, J.; Shi, X.; Zeng, S. Crashworthiness multi-objective optimization design of novel thin-walled circular tube with continuous gradient variable cross-section. J. Chongqing Univ. Technol. Nat. Sci. 2022, 36, 105–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kalita, K.; Ramesh, J.V.N.; Cepova, L.; Pandya, S.B.; Jangir, P.; Abualigah, L. Multi-objective exponential distribution optimizer (MOEDO): A novel math-inspired multi-objective algorithm for global optimization and real-world engineering design problems. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, H.; Wen, G.; Hou, S.; Qing, Q. Multiobjective crashworthiness optimization of functionally lateral graded foam-filled tubes. Mater. Des. 2013, 44, 414–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Wang, Z.; Wang, S.; Gao, M.; Zeng, Y.; Jia, S. Efficient Parameterized Modeling Technology of Tire Based on Python Language and Abaqus Software. China Rubber Ind. 2021, 68, 816–821. [Google Scholar]

| Material | Poisson’s Ratio () | Yield Strength (MPa) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7050Al | 2.83 | 71,443 | 0.33 | 455 |

| εδ/mm | H/mm | ALLIE/J | mass/g | f/N | SEA/J·g−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOEDO | 1.79598 | 42 | 647.447 | 17.0951 | 38,262.5 | 37.8910 |

| NASGII | 1.81117 | 44 | 648.447 | 17.8262 | 38,563.9 | 36.3761 |

| NCGA | 1.85271 | 40 | 642.312 | 17.9999 | 39,250.3 | 35.6841 |

| AMGA | 1.82134 | 40 | 645.384 | 17.6541 | 38,641.8 | 36.7445 |

| MOPSO | 1.84332 | 53 | 636.131 | 21.2614 | 38,727.5 | 29.9195 |

| No. | E/mm | L/mm | ALLIE/kJ | Mass/g | f/kN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 47 | 3.03 | 57 | 0.76945 | 16.5934 | 50.1828 |

| 48 | 1.81 | 137 | 2.77441 | 39.8824 | 53.0441 |

| 49 | 2.46 | 69 | 1.09662 | 20.0867 | 51.3267 |

| 51 | 1.91 | 59 | 1.12547 | 17.1756 | 52.1482 |

| 56 | 1.86 | 106 | 2.00537 | 30.8579 | 52.9417 |

| 58 | 2.97 | 59 | 1.04049 | 15.4289 | 53.4363 |

| 949 | 1.86 | 106 | 0.70723 | 14.5556 | 47.9041 |

| 951 | 3.01 | 53 | 2.84317 | 41.9201 | 53.7196 |

| 955 | 1.80 | 50 | 0.69159 | 14.5556 | 47.1179 |

| 957 | 3.01 | 250 | 5.17421 | 72.7781 | 52.5926 |

| 958 | 3.10 | 110 | 1.35332 | 32.0223 | 49.0216 |

| 960 | 1.80 | 166 | 3.37618 | 48.3246 | 53.2855 |

| E/mm | L/mm | ALLIE/kJ | Mass/g | f/kN |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.90 | 101 | 1.9635 | 29.4 | 43.87 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ren, J.; Liu, S.; Dong, X.; Zhao, C. Multi-Objective Optimization of the Crashworthiness of Aluminum Circular Tubes with Graded Thicknesses. Materials 2025, 18, 5399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235399

Ren J, Liu S, Dong X, Zhao C. Multi-Objective Optimization of the Crashworthiness of Aluminum Circular Tubes with Graded Thicknesses. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235399

Chicago/Turabian StyleRen, Jie, Shujie Liu, Xiangyu Dong, and Changfang Zhao. 2025. "Multi-Objective Optimization of the Crashworthiness of Aluminum Circular Tubes with Graded Thicknesses" Materials 18, no. 23: 5399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235399

APA StyleRen, J., Liu, S., Dong, X., & Zhao, C. (2025). Multi-Objective Optimization of the Crashworthiness of Aluminum Circular Tubes with Graded Thicknesses. Materials, 18(23), 5399. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235399