Adsorption Mechanism of Short Hydrophobic Extended Anionic Surfactants at the Quartz–Solution Interface

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Apparatus and Method

2.2.1. Surface Tension Measurement

2.2.2. Contact Angle Measurement

3. Results

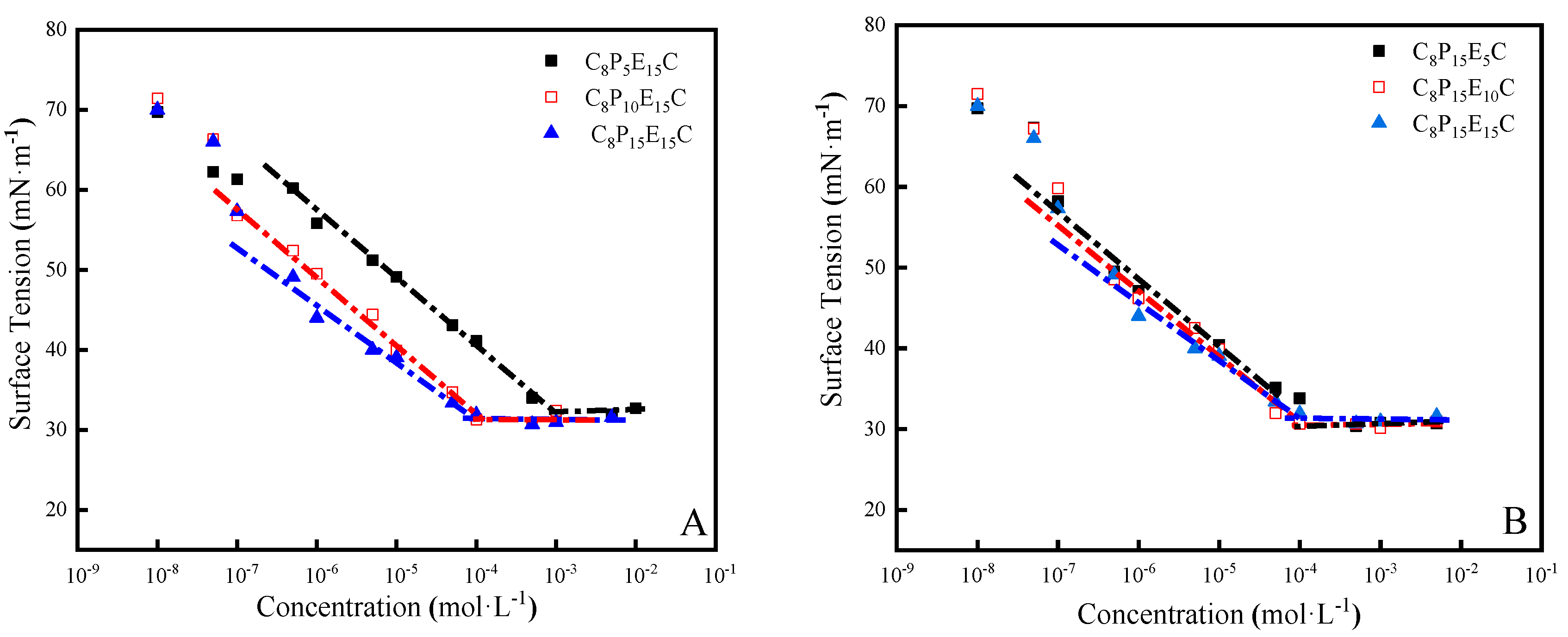

3.1. Surface Tension of C8PxEyC

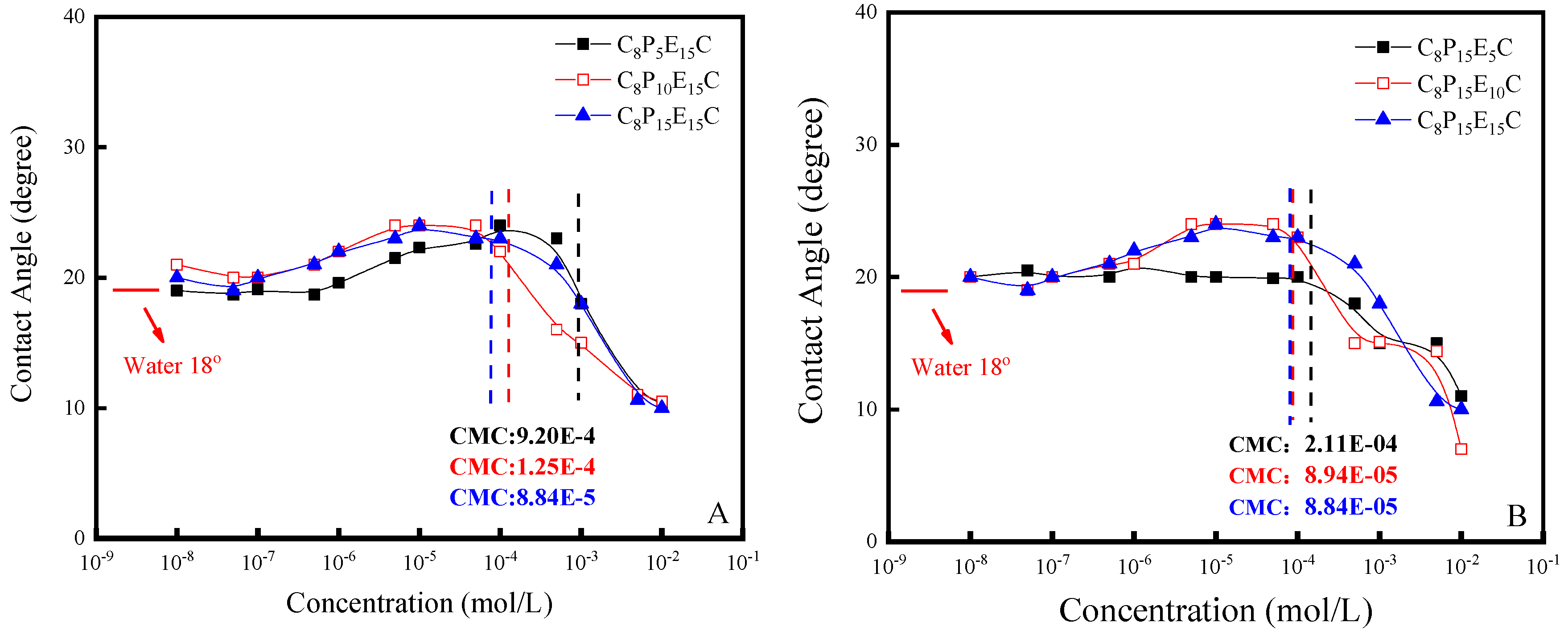

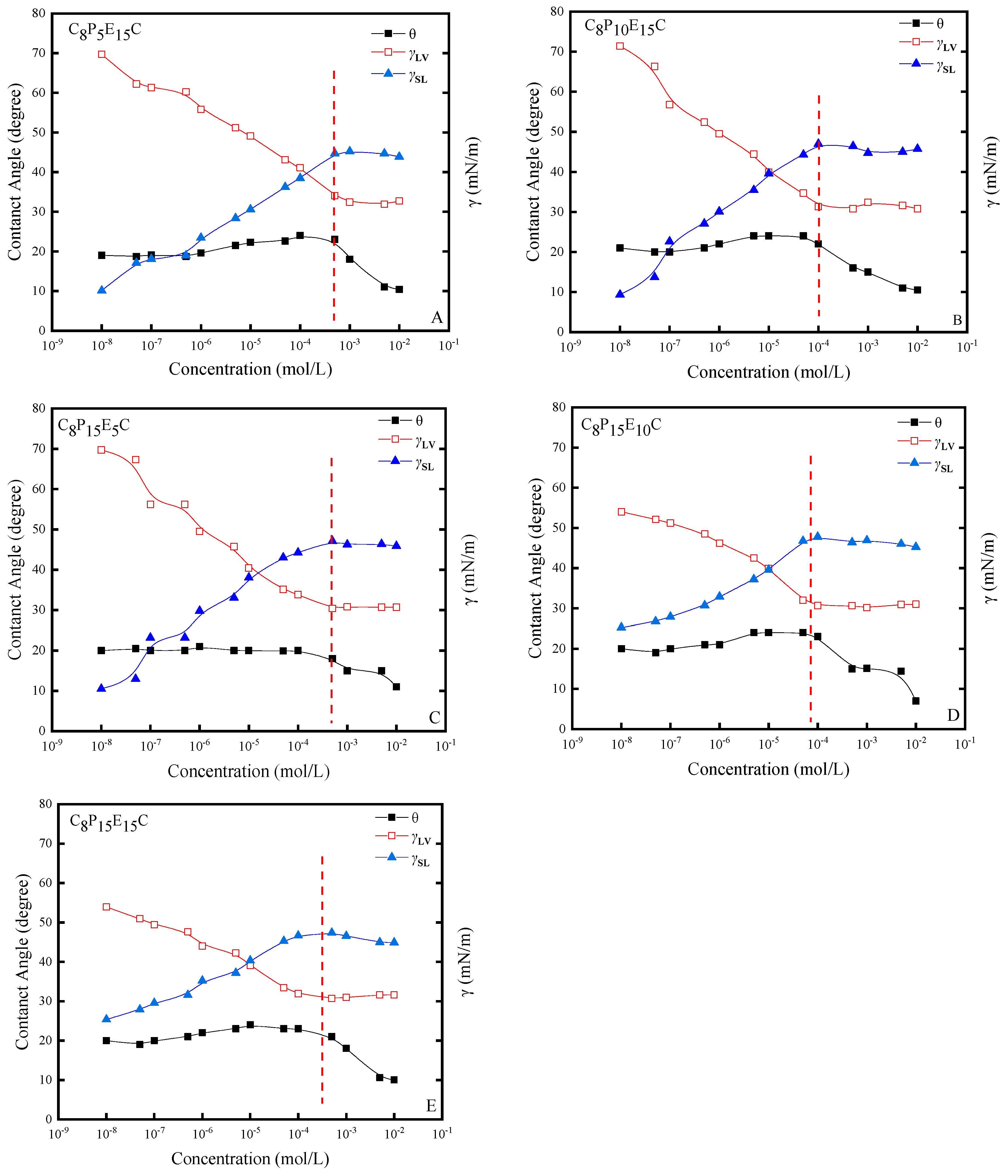

3.2. Contact Angles of C8PxEyC

3.3. Adhesional Tension of C8PxEyC

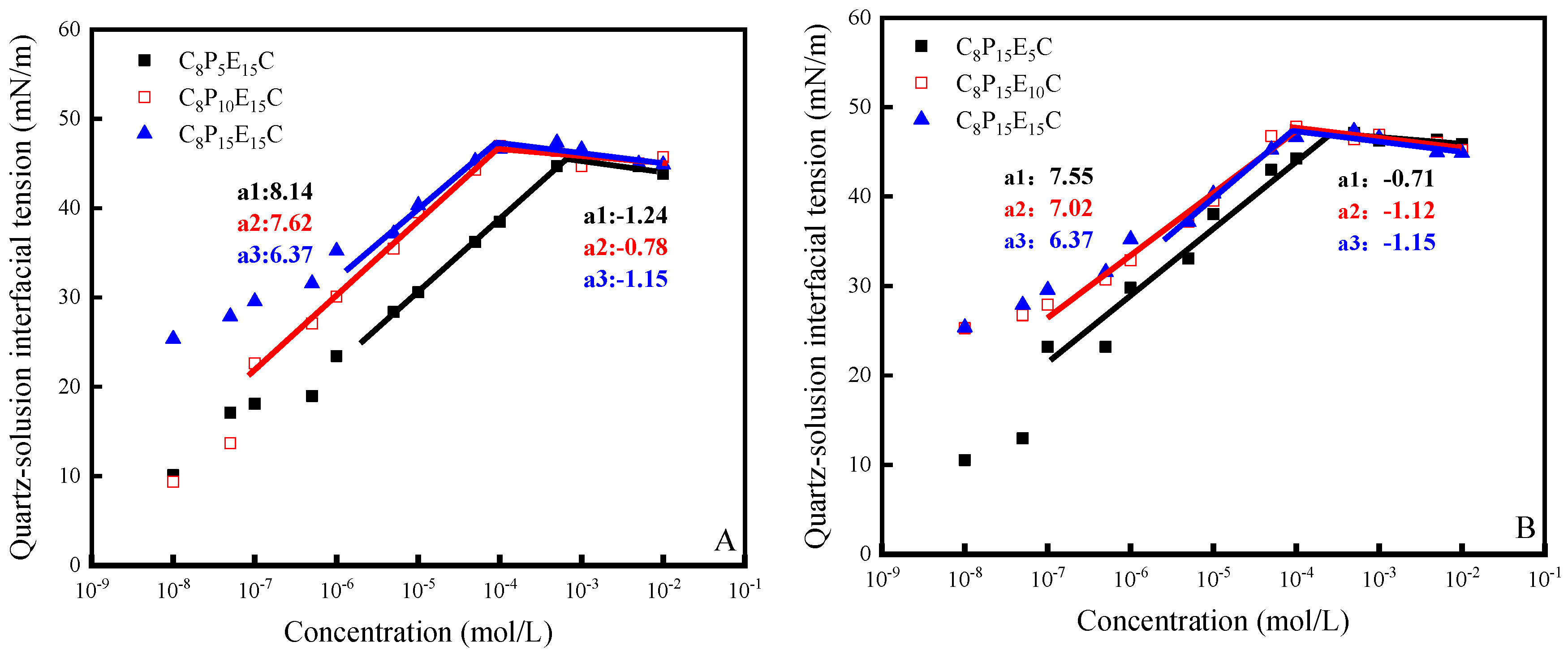

3.4. Interfacial Tension of C8PxEyC on the Quartz–Liquid Interface

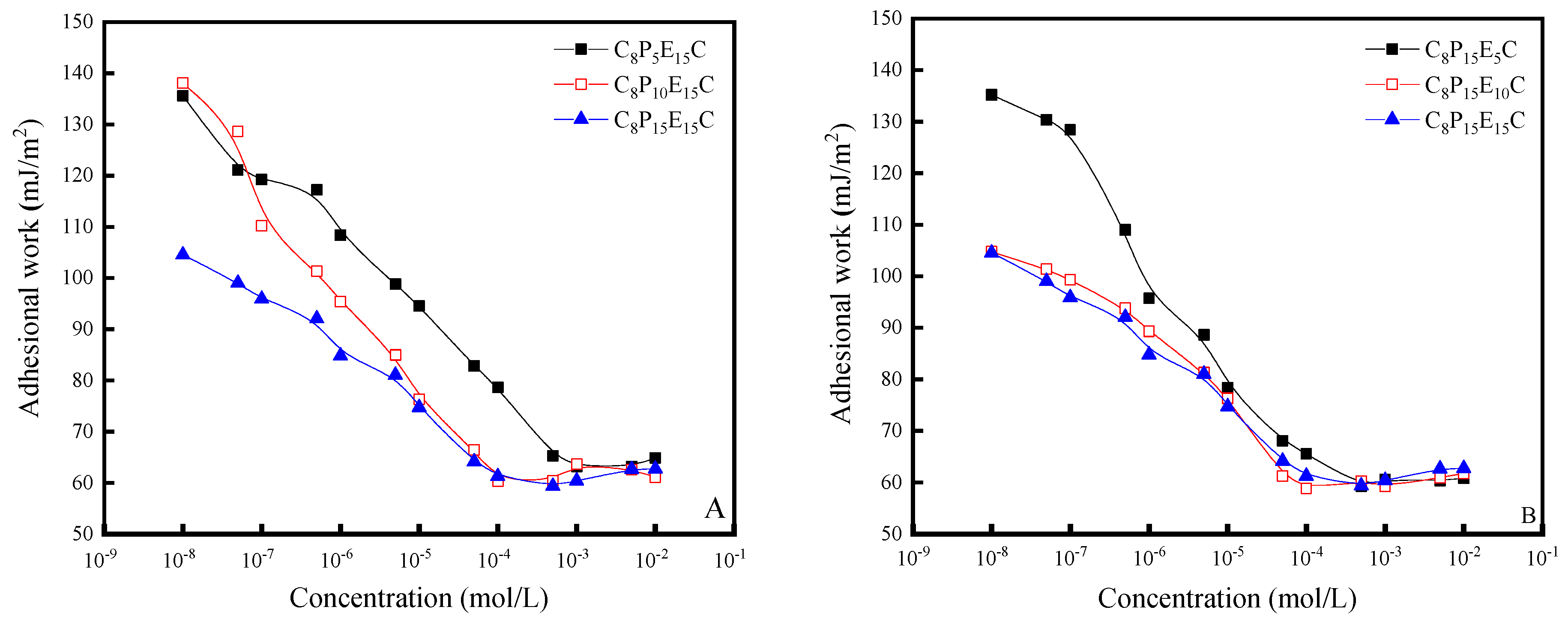

3.5. Adhesion Work of C8PxEyC

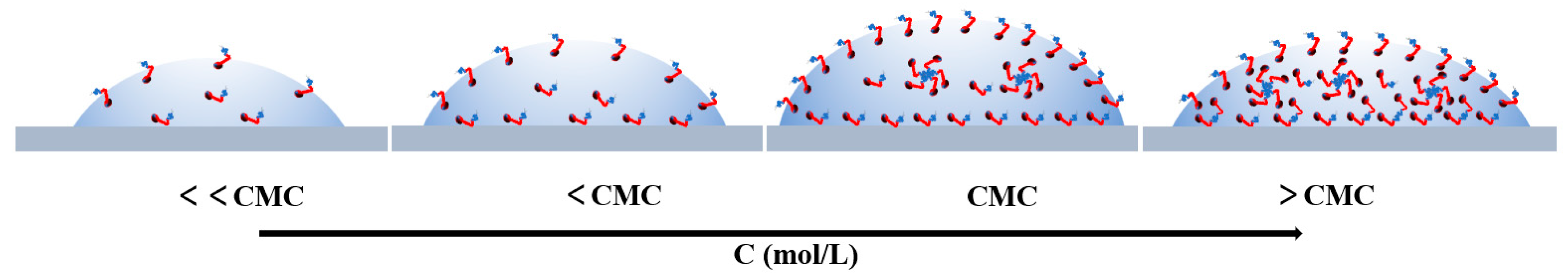

3.6. Adsorption Mechanism of C8PxEyC on Quartz

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, D.; Ao, X.; Yuan, X.; Liu, Q. Effect of dissolved metal ions from mineral surfaces on the surface wettability of phosphate ore by flotation. Colloids Surf. A 2024, 701, 134995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, F.; Zhang, K.; Xu, C.; Fang, K. Drying-free inkjet printing of cotton fabrics through controlling the diffusion of dye inks in wet sodium alginate films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 307, 141825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W.; Hou, X.; Duan, F.; Ma, Y.; Ali, M.K.A. Wettability influence on the lubrication performance of modified silver/carbon black nano additives. Tribol. Int. 2026, 213, 110996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Du, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, W.; Yan, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Wettability of a Polymethylmethacrylate Surface by Extended Anionic Surfactants: Effect of Branched Chains. Molecules 2021, 26, 863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arcos, X.V.; Mayorga, J.D.B.; Chaves-Guerrero, A.; Mercado, R. Wettability Assessment of Hydrophobized Granular Solids: A Rheological Approach Using Surfactant Adsorption. Materials 2025, 18, 1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, V.; Schneider, L.; Brosig, S.; Medrano, S.M.; Cucuzza, S. InterFace/Off: Characterization of competitive adsorption of novel surfactants and proteins at the solid-liquid and oil-liquid interfaces. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2025, 254, 114865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusseau, M.L. Quantifying the adsorption of PFAS and hydrocarbon surfactants at the air–water interface: A systematic review and meta-analysis of surface-science measurements, molecular-modeling simulations, and environmental-application results. Water Res. 2025, 284, 123952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, I.; Burley, A.; Petkova, R.; Hosking, S.; Webster, J.; Li, P.; Ma, K.; Penfold, J.; Thomas, R. Promoting the adsorption of saponins at the hydrophilic solid-aqueous solution interface by the coadsorption with cationic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 654, 1031–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubao, A.; Yang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tan, X.; Hu, R.; Wood, C.D.; Li, Y.; Chen, Y.-F. Understanding the alteration of quartz wettability in underground hydrogen storage from energetic and structural perspectives. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 175, 151502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.-L.; Li, Z.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.-C.; Zhao, S.; Yu, J.-Y. Wettability of a Quartz Surface in the Presence of Four Cationic Surfactants. Langmuir 2010, 26, 18834–18840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdziennicka, A.; Szymczyk, K.; Jańczuk, B. Correlation between surface free energy of quartz and its wettability by aqueous solutions of nonionic, anionic and cationic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 340, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B.; Wójcik, W. Wettability of polytetrafluoroethylene by aqueous solutions of two anionic surfactant mixtures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2003, 268, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.-S.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.-C.; Gong, Q.-T.; Jin, Z.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Wettability alteration by novel betaines at polymer-aqueous solution interfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 355, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.-Q.; Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.-C.; Liu, D.-D.; Song, X.-W.; Cao, X.-L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Effect of Zwitterionic Surfactants on Wetting of Quartz Surfaces. Colloids Surf. A 2013, 430, 110–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, P.; Hu, X.; Fang, Y.; Li, M.; Xia, Y. Correlation among copolyether spacers, molecular geometry and interfacial properties of extended surfactants. Colloids Surf. A 2022, 639, 128286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Q.; Zhu, Y.-W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Studies on interfacial interactions between extended surfactant and betaine by dilational rheology. Colloids Surf. A 2025, 710, 136245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-q.; Zhang, M.-j.; Fang, Y.; Jin, G.-y.; Chen, J. Extended surfactants: A well-designed spacer to improve interfacial performance through a gradual polarity transition. Colloids Surf. A 2014, 450, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.; Marquez, R. Extended Surfactants Including an Alkoxylated Central Part Intermediate Producing a Gradual Polarity Transition—A Review of the Properties Used in Applications Such as Enhanced Oil Recovery and Polar Oil Solubilization in Microemulsions. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 22, 935–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Hu, X.-y.; Fang, Y.; Jin, G.-y.; Xia, Y.-m. What dominates the interfacial properties of extended surfactants: Amphipathicity or surfactant shape? J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 547, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forgiarini, A.M.; Marquez, R.; Salager, J.-L. Formulation Improvements in the Applications of Surfactant–Oil–Water Systems Using the HLDN Approach with Extended Surfactant Structure. Molecules 2021, 26, 3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Zheng, Y.; Tian, F.; Liu, H.; Lu, X.; Yi, X.; Wang, Z. Performance of extended surfactant and its mixture with betaine surfactant for enhanced oil recovery in sandstone reservoirs with low permeability. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 391, 123228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.D.; Stevens, T.L.; Kibbey, T.C.G.; Sabatini, D.A. Preliminary formulation development for aqueous surfactant-based soybean oil extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 62, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, L.D.; Sabatini, D.A. Aqueous Extended-Surfactant Based Method for Vegetable Oil Extraction: Proof of Concept. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2010, 87, 1211–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaphong, C.; Sabatini, D.A. Detergents Optimized Microemulsion Systems for Detergency of Vegetable Oils at Low Surfactant Concentration and Bath Temperature. J. Surfact. Deterg. 2017, 20, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, M.J. Surfactants and Interfacial Phenomena, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Seredyuk, V.; Alami, E.; Nydén, M.; Holmberg, K.; Peresypkin, A.V.; Regev, O. Adsorption of Zwitterionic Gemini Surfactants at the Air–Water and Solid–Water Interfaces. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2002, 203, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-F.; Xu, Z.-C.; Gong, Q.-T.; Wu, D.-h.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, S. Adsorption of extended anionic surfactants at the water- polymethylmethacrylate interface: The effect of polyoxyethylene groups. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2023, 656, 130395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Li, Q.; Niu, J. Surface tension, interfacial tension and emulsification of sodium dodecyl sulfate extended surfactant. Colloids Surf. A 2016, 494, 201–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Zhou, Z.-H.; Gao, M.; Han, L.; Zhang, L.; Yan, F.; Wang, M.; Zhang, L. Adsorption and wettability of extended anionic surfactants with different PO numbers on a polymethylmethacrylate surface. Soft Matter 2021, 17, 6426–6434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B.; Wójcik, W. The wettability of polytetrafluoroethylene and polymethyl methacrylate by aqueous solution of two cationic surfactants mixture. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 293, 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bargeman, D.; Vader, F.V. Effect of surfactants on contact angles at nonpolar solids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1973, 42, 467–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucassen-Reynders, E.H. Surface Equation of State for Ionized Surfactants. J. Phys. Chem. 1966, 70, 1777–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Chu, Y.; Zhao, G.; Yin, Z.; Kuang, T.; Yan, F.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Study of surface wettability of mineral rock particles by improved Washburn method. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 15721–15729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szymczyk, K. Work of adhesion and activity of aqueous solutions of ternary mixtures of hydrocarbon and fluorocarbon nonionic surfactants at the water–air and polymer–water interfaces. Colloid Surf. A-Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 441, 226–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krawczyk, J.; Szymczyk, K.; Zdziennicka, A.; Jańczuk, B. Wettability of polymers by aqueous solution of binary surfactants mixture with regard to adhesion in polymer–solution system II. Critical surface tension of polymers wetting and work of adhesion. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2013, 45, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molecular Formulas | CMC (mol·L−1) | γCMC m−1) | Гmax (10−10 mol·m−2) | Amin (nm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C8P5E15C | 9.20 × 10−4 | 32.18 | 1.50 | 1.11 |

| C8P10E15C | 1.25 × 10−4 | 31.23 | 1.47 | 1.12 |

| C8P15E5C | 1.43 × 10−4 | 30.56 | 1.43 | 1.16 |

| C8P15E10C | 9.71 × 10−5 | 30.84 | 1.39 | 1.19 |

| C8P15E15C | 8.84 × 10−5 | 31.37 | 1.26 | 1.32 |

| C16E3C [27] | 9.40 × 10−5 | 22.82 | 1.73 | 0.96 |

| C16E5C [27] | 4.50 × 10−5 | 31.84 | 1.52 | 1.09 |

| C16E7C [27] | 1.00 × 10−5 | 34.69 | 1.31 | 1.31 |

| C12P4S [28] | 4.20 × 10−4 | 40.00 | 1.66 | 1.66 |

| C12P8S [28] | 7.80 × 10−5 | 35.50 | 1.54 | 1.54 |

| C12P12S [28] | 4.30 × 10−5 | 33.70 | 1.64 | 1.64 |

| S-C12P7S [29] | 4.60 × 10−5 | 33.80 | 1.47 | 1.47 |

| S-C12P13S [29] | 1.20 × 10−5 | 31.90 | 1.48 | 1.48 |

| Surfactants | ГSL/ГLV | Гmax (10−10 mol·m−2) | Amin (nm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C8P5E15C | 0.93 | 1.40 | 1.19 |

| C8P10E15C | 0.93 | 1.37 | 1.21 |

| C8P15E5C | 0.93 | 1.33 | 1.25 |

| C8P15E10C | 0.93 | 1.29 | 1.29 |

| C8P15E15C | 0.93 | 1.17 | 1.42 |

| Abrr. | Γbelow (10−10 mol·m−2) | Abelow (nm2) | Γabove (10−10 mol·m−2) | Aabove (nm2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C8P5E15C | 1.43 | 1.16 | 0.22 | 7.64 |

| C8P10E15C | 1.34 | 1.24 | 0.14 | 12.15 |

| C8P15E5C | 1.32 | 1.26 | 0.12 | 13.35 |

| C8P15E10C | 1.23 | 1.35 | 0.20 | 8.46 |

| C8P15E15C | 1.12 | 1.49 | 0.20 | 8.24 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Xu, Z.; Jin, Z.; Ma, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Adsorption Mechanism of Short Hydrophobic Extended Anionic Surfactants at the Quartz–Solution Interface. Materials 2025, 18, 5392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235392

Zhang L, Xu Z, Jin Z, Ma W, Zhang L, Zhang L. Adsorption Mechanism of Short Hydrophobic Extended Anionic Surfactants at the Quartz–Solution Interface. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235392

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Linlin, Zhicheng Xu, Zhiqiang Jin, Wangjing Ma, Lei Zhang, and Lu Zhang. 2025. "Adsorption Mechanism of Short Hydrophobic Extended Anionic Surfactants at the Quartz–Solution Interface" Materials 18, no. 23: 5392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235392

APA StyleZhang, L., Xu, Z., Jin, Z., Ma, W., Zhang, L., & Zhang, L. (2025). Adsorption Mechanism of Short Hydrophobic Extended Anionic Surfactants at the Quartz–Solution Interface. Materials, 18(23), 5392. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235392