Performance Evolution of High-Slump Concrete Under Vibration: Influence of Vibration Timing on Mechanical, Durability, and Interfacial Properties

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Mix Proportion

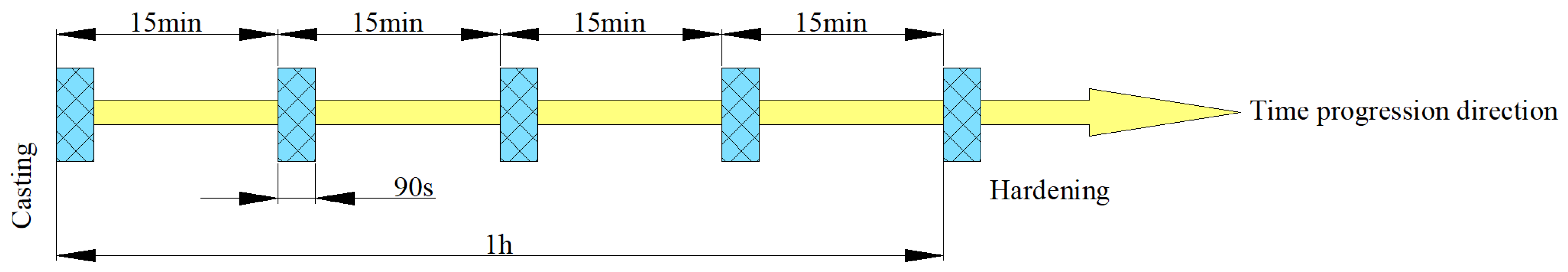

2.3. Vibration Modes

2.4. Mechanical Properties Test

2.4.1. Compressive Strength Test

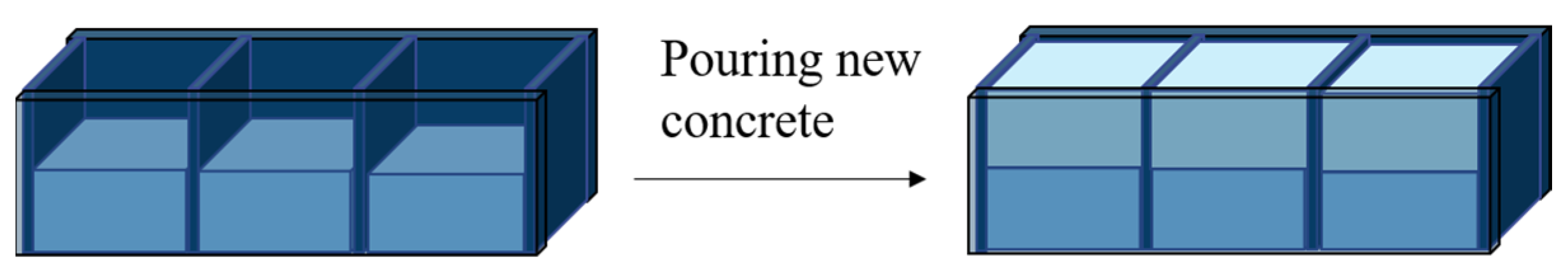

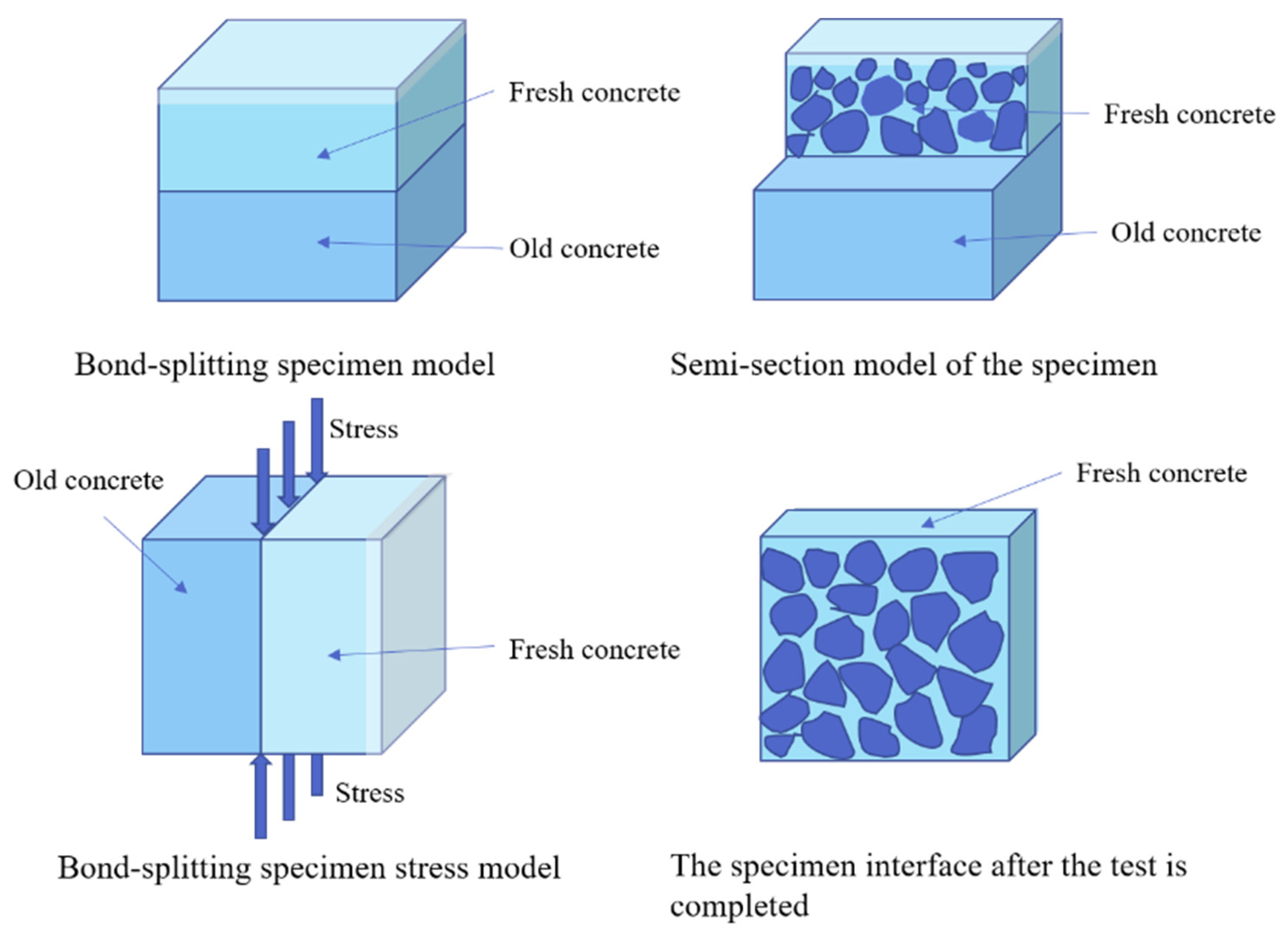

2.4.2. Bond-Splitting Strength Test

2.5. Durability Test

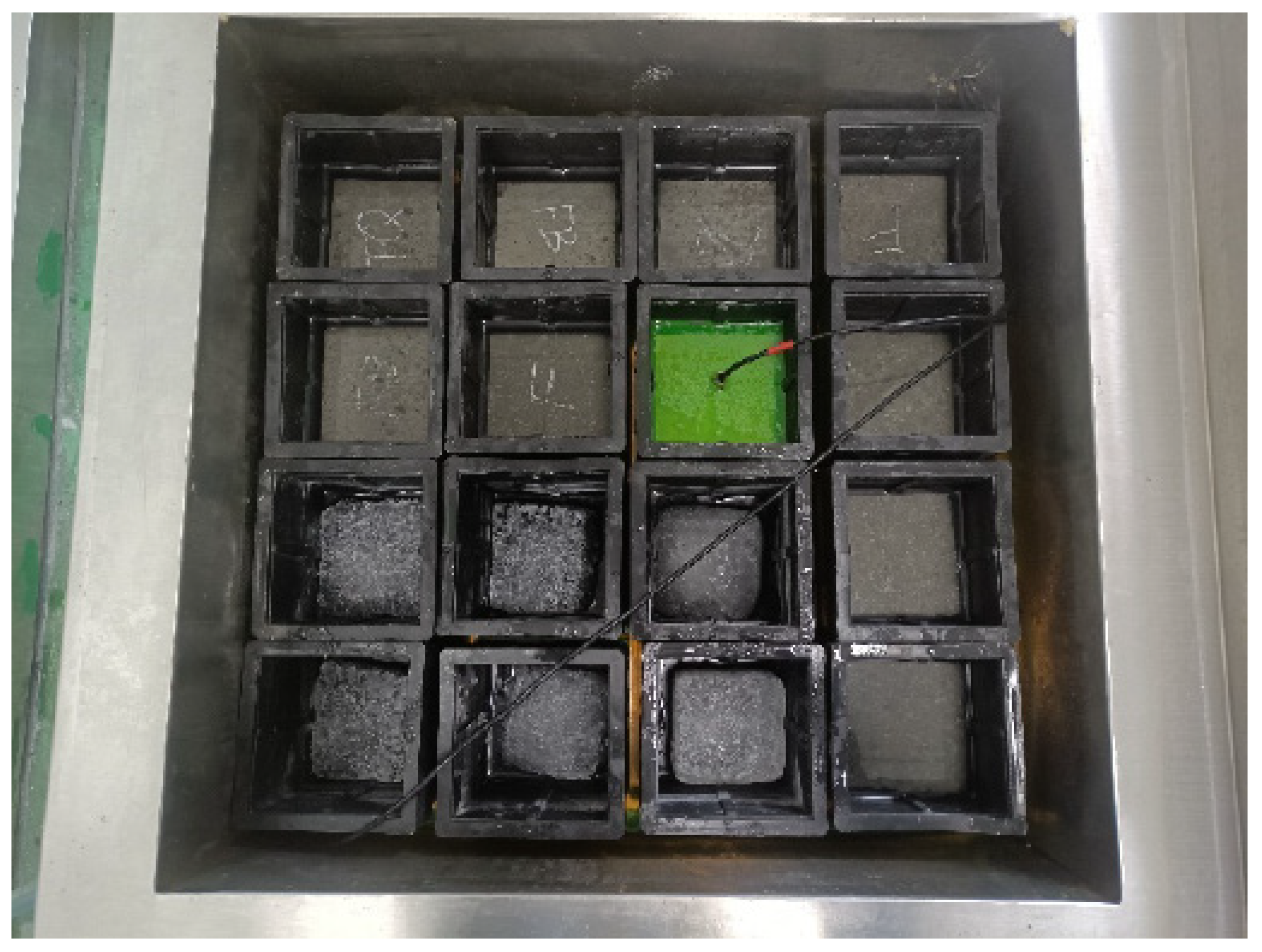

2.5.1. Freeze–Thaw Cycle Test

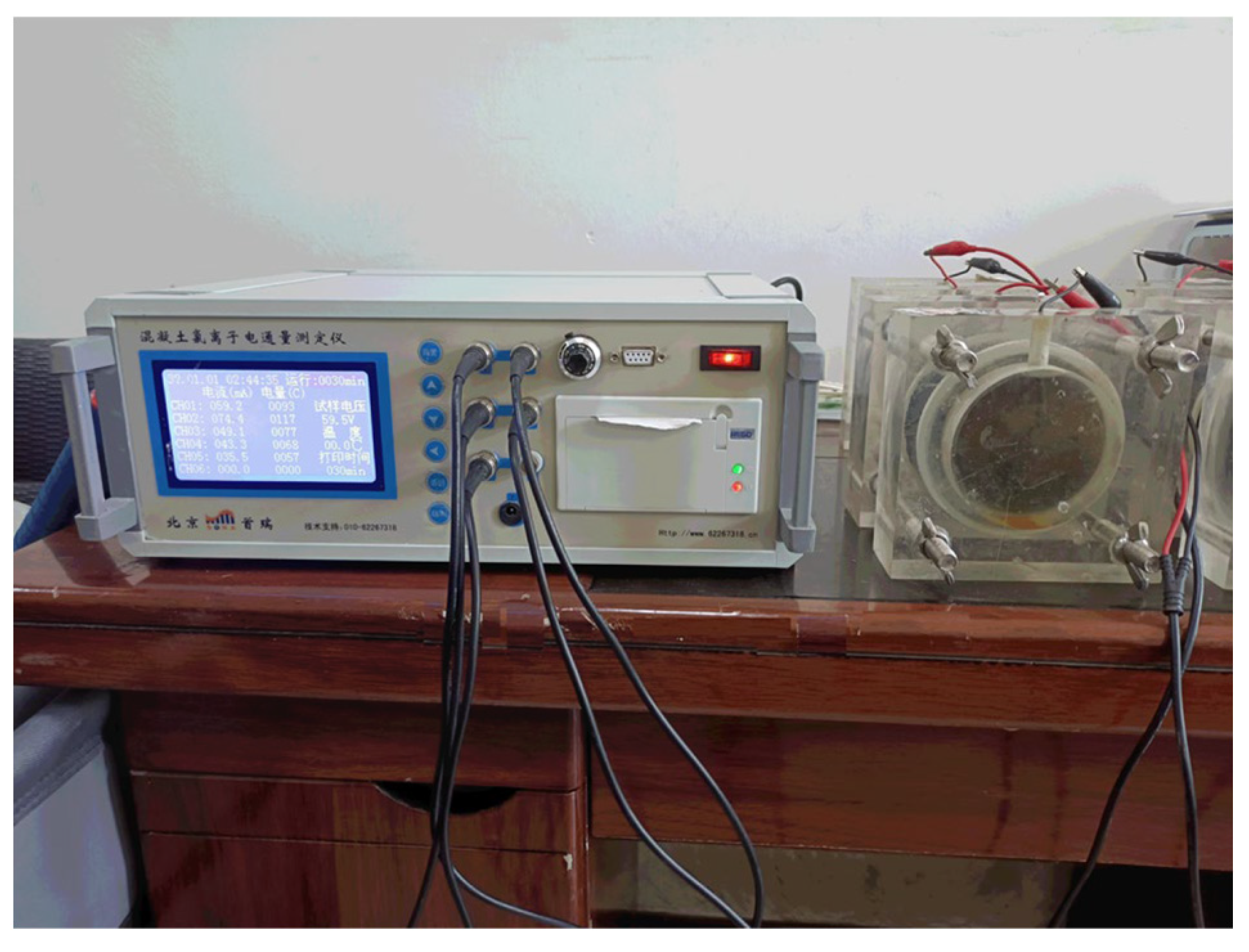

2.5.2. Chloride Ion Penetration Test

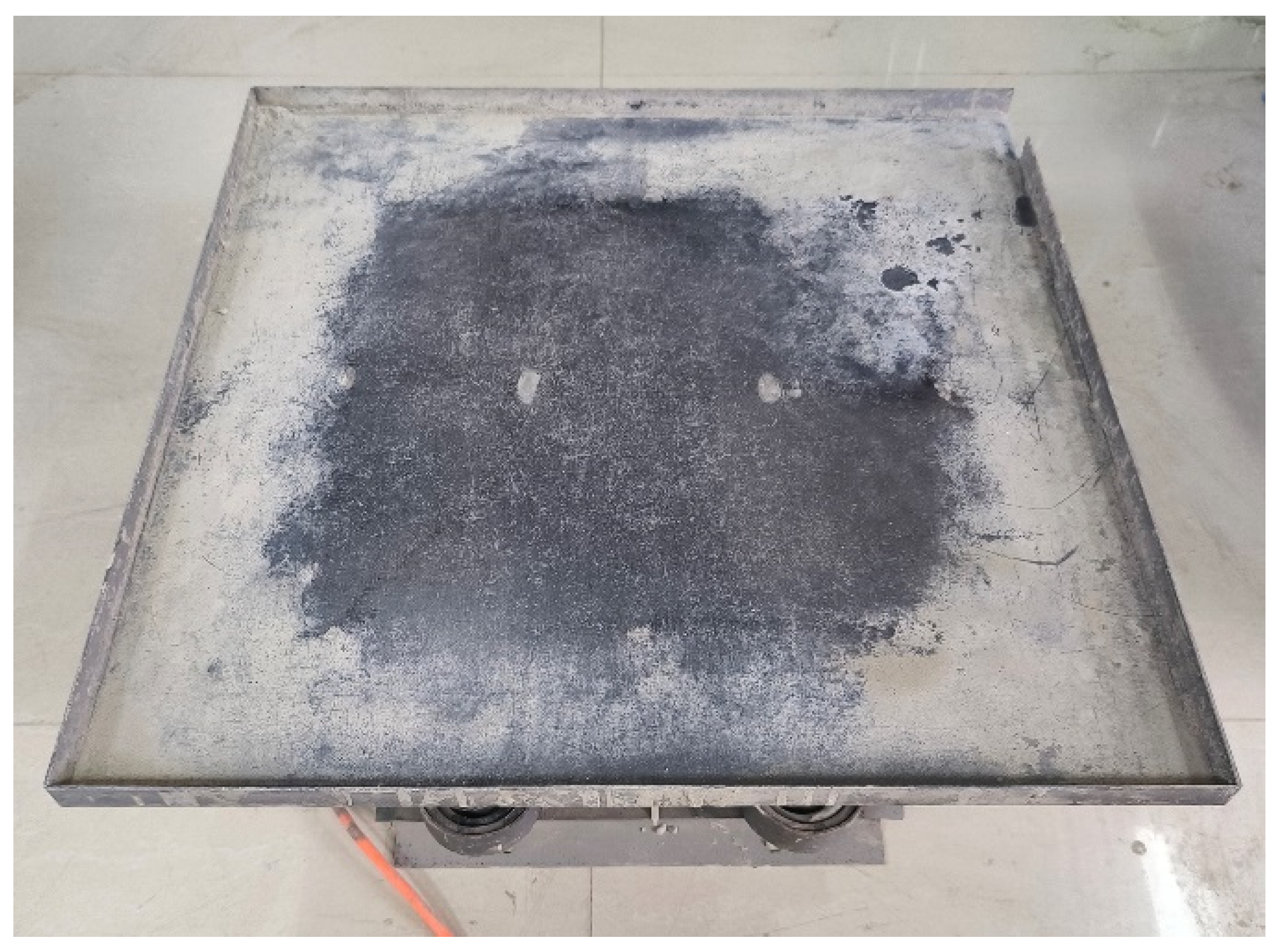

2.5.3. Abrasion Resistance Test

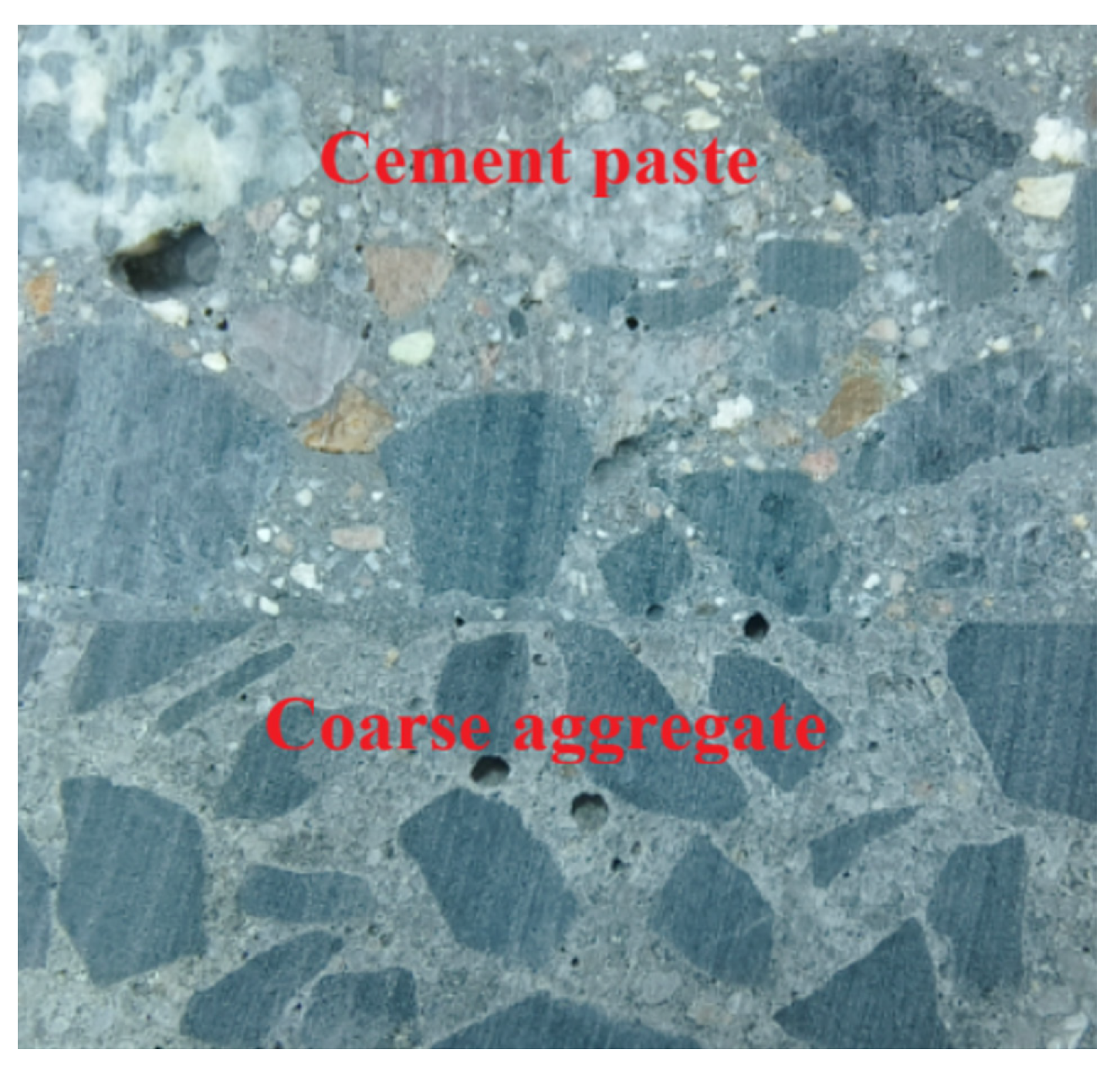

2.6. Microstructure Test

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties

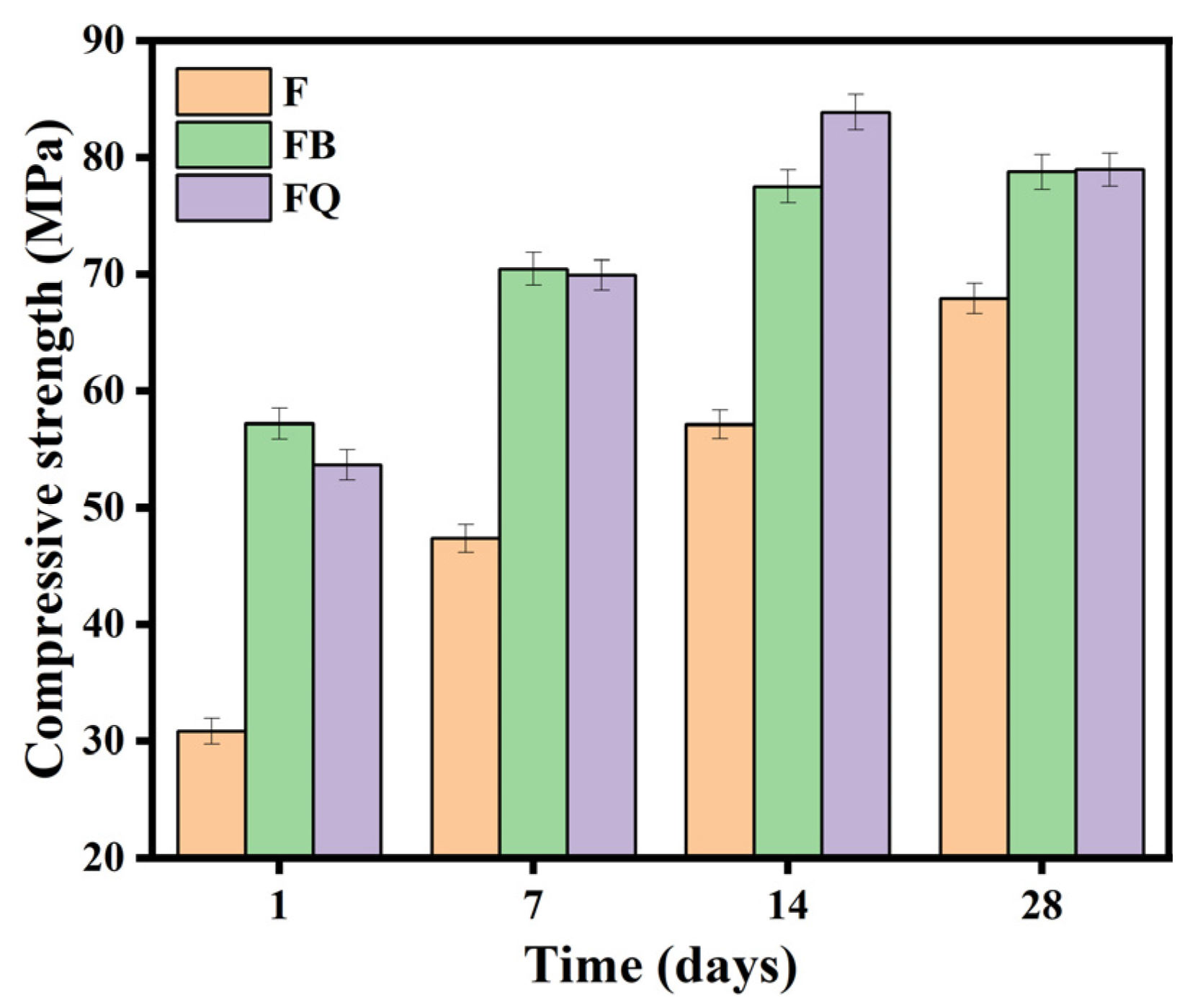

3.1.1. Compressive Strength

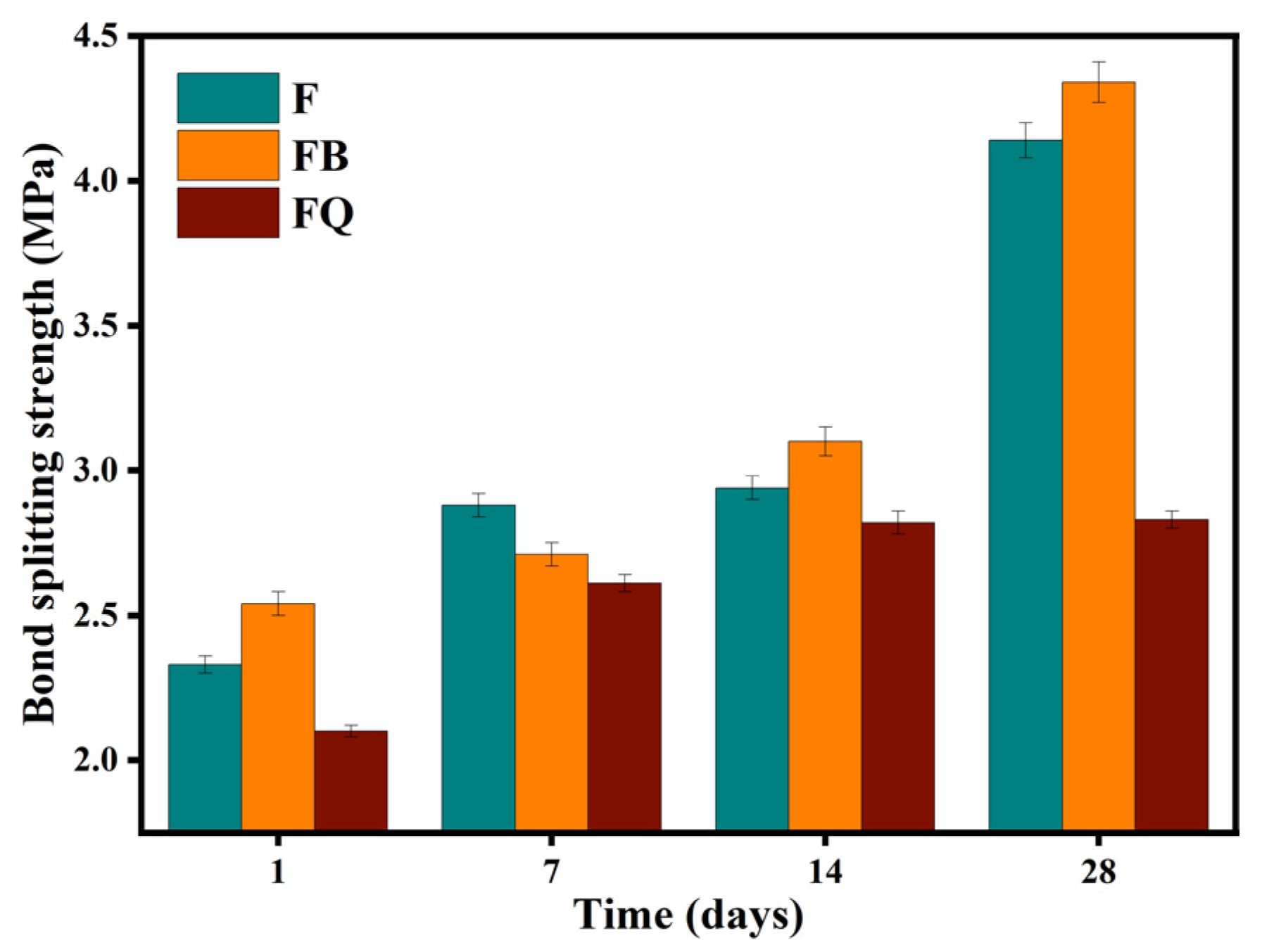

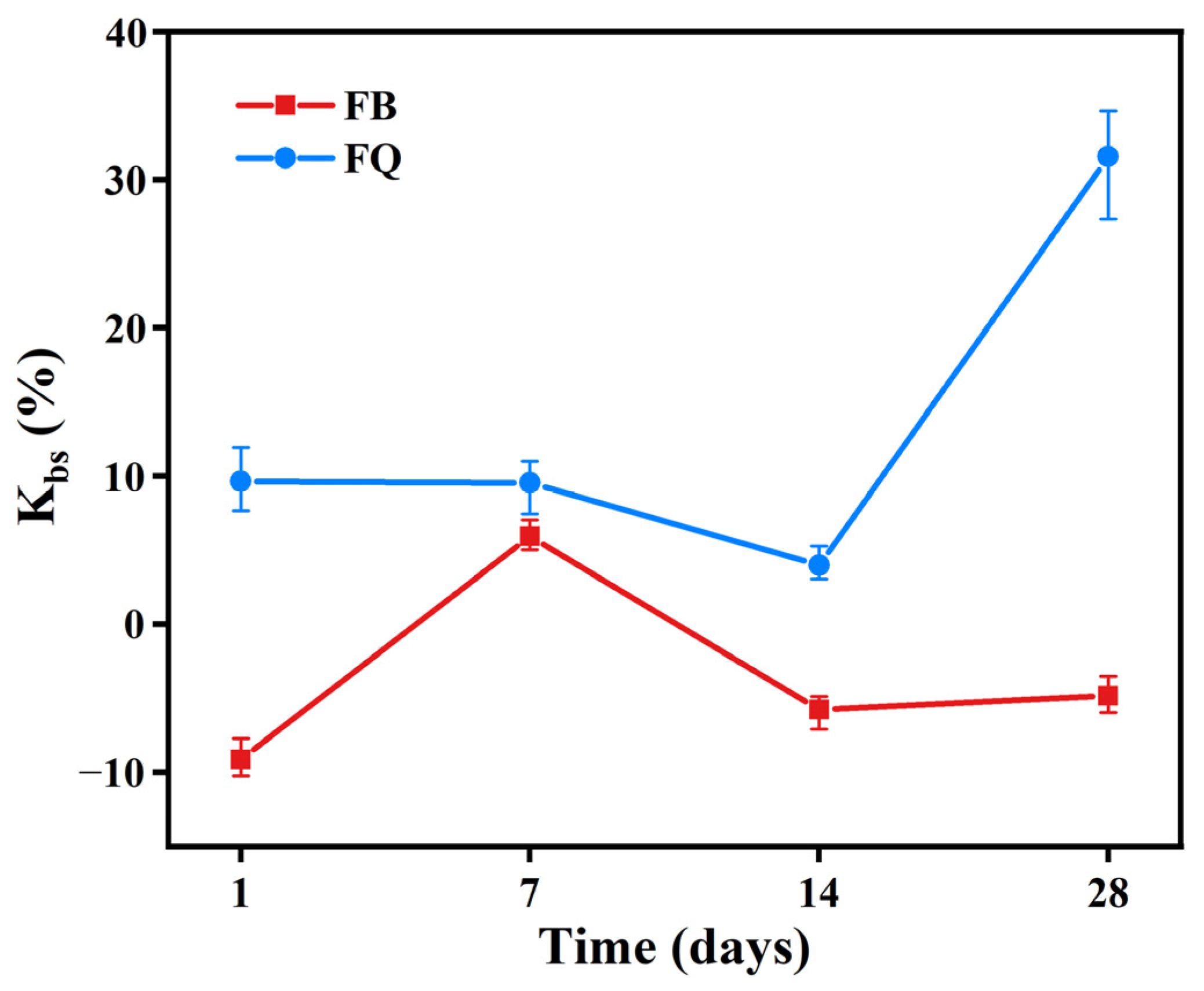

3.1.2. Bond-Splitting Strength

3.2. Durability Properties

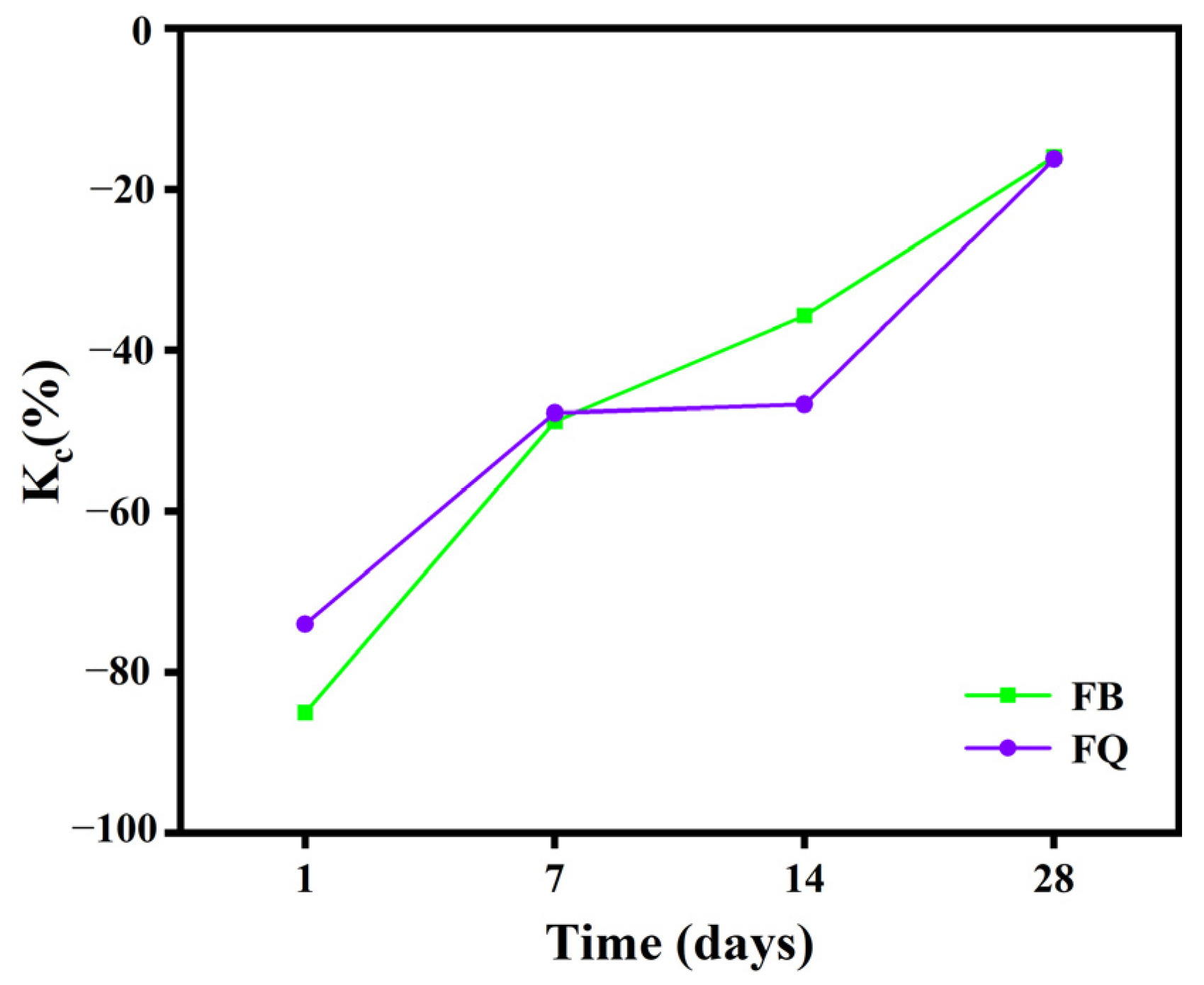

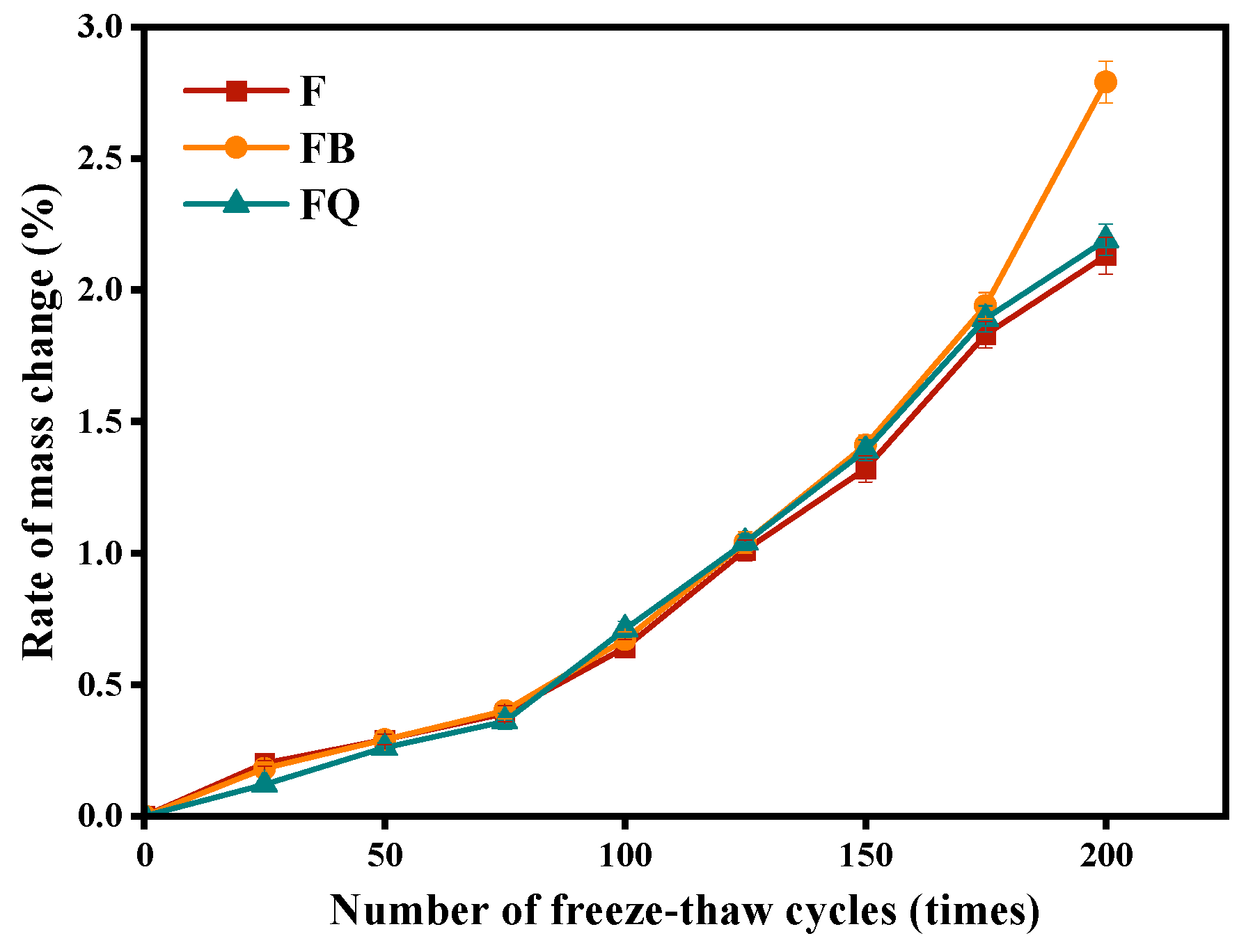

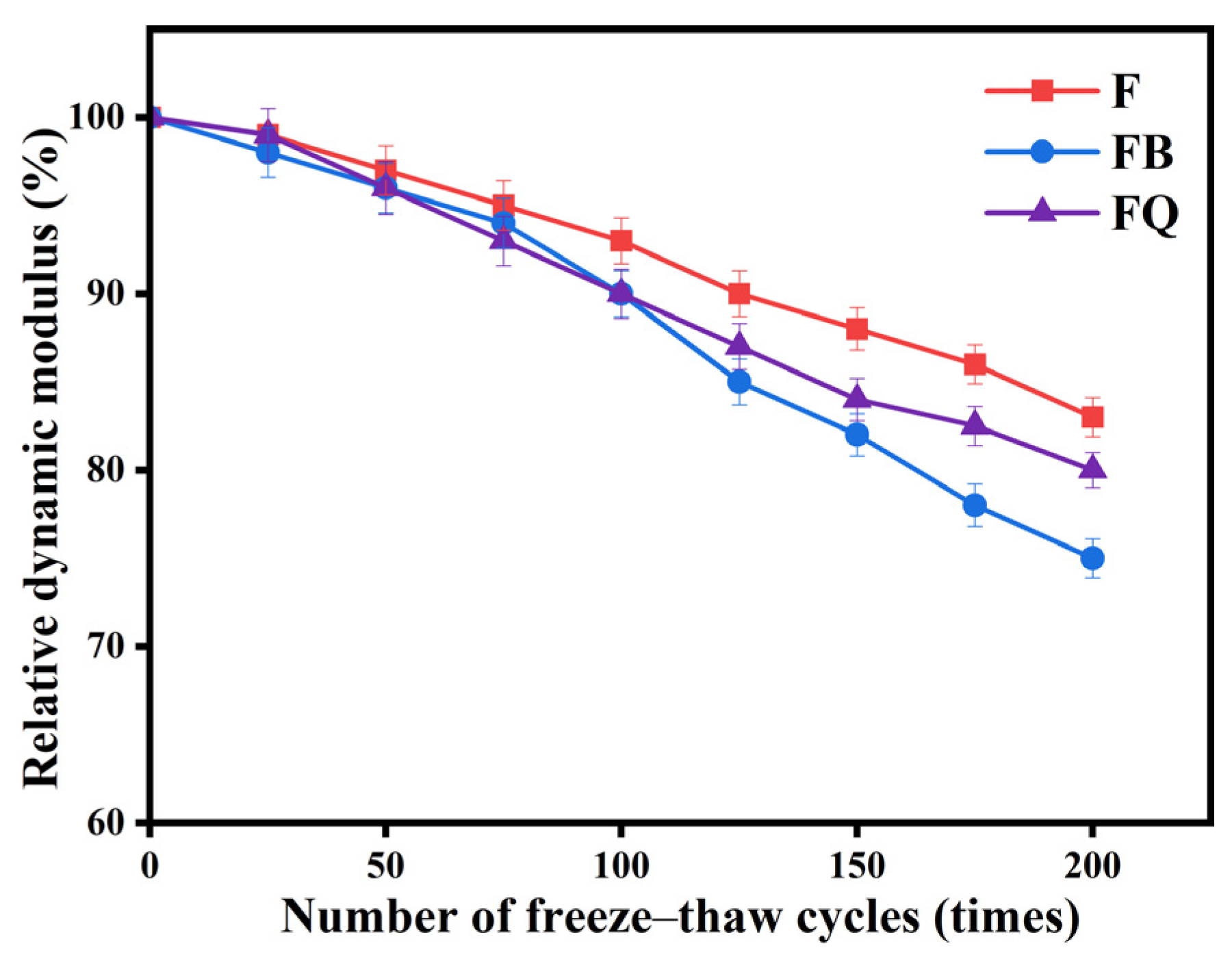

3.2.1. Frost Resistance

3.2.2. Chloride Penetration Resistance

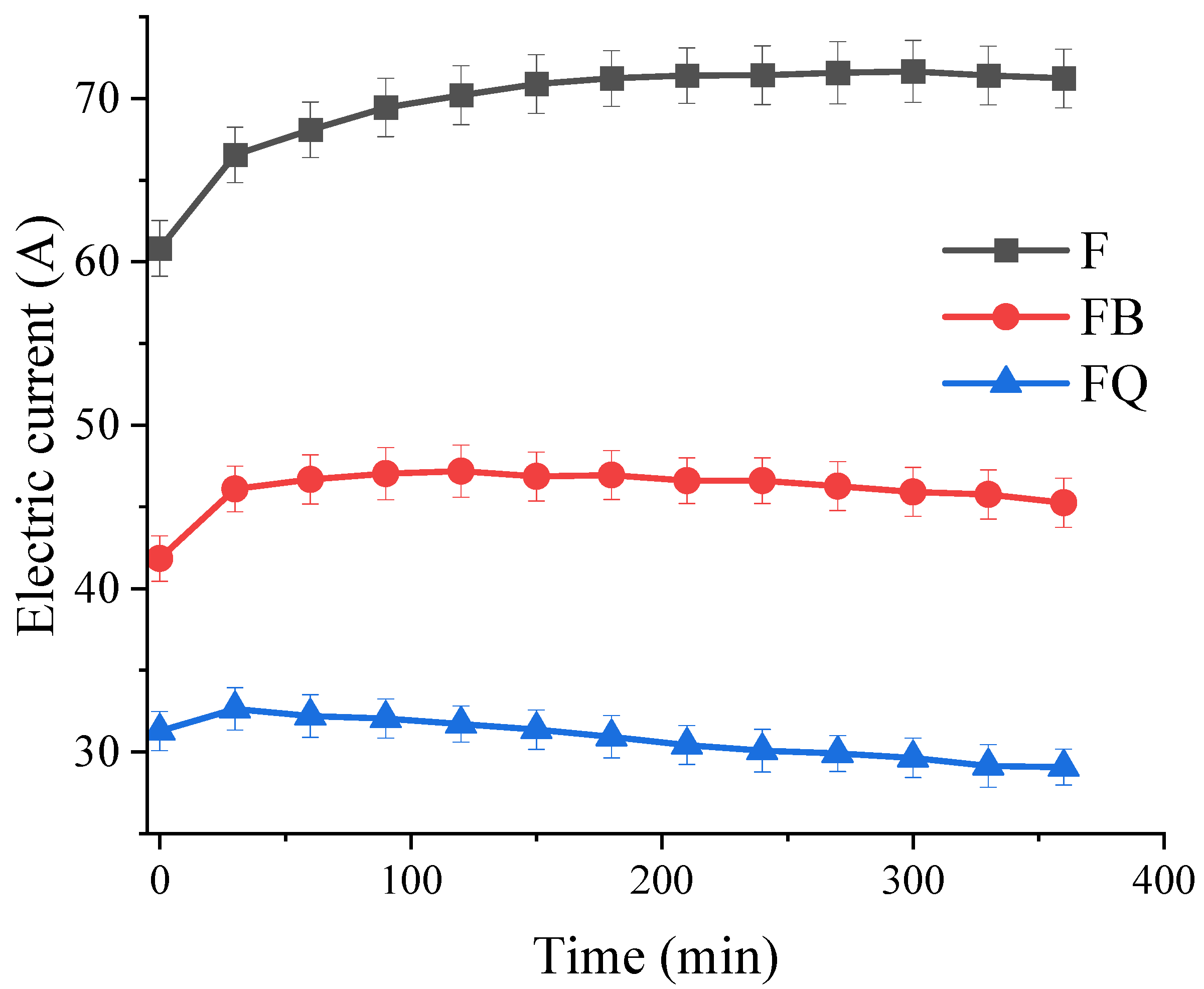

3.2.3. Abrasion Resistance

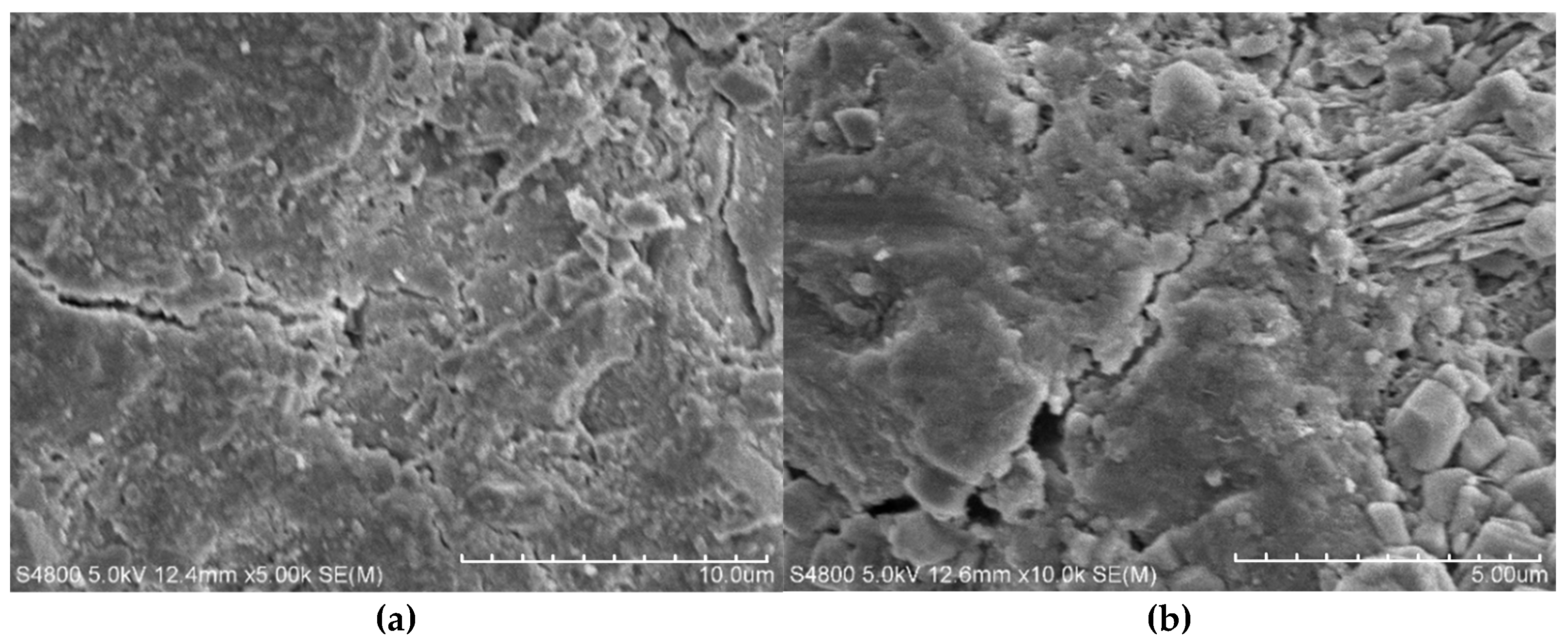

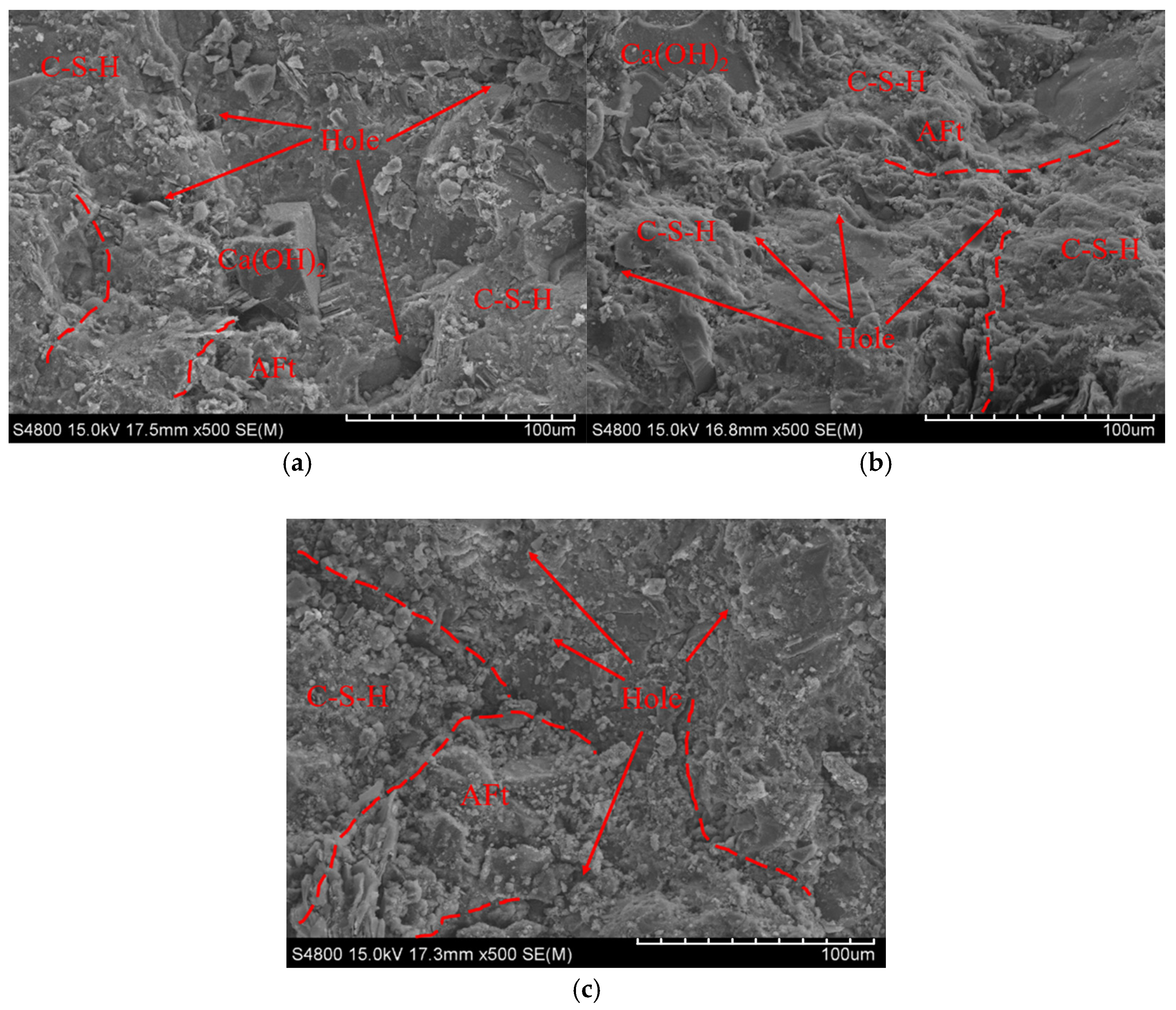

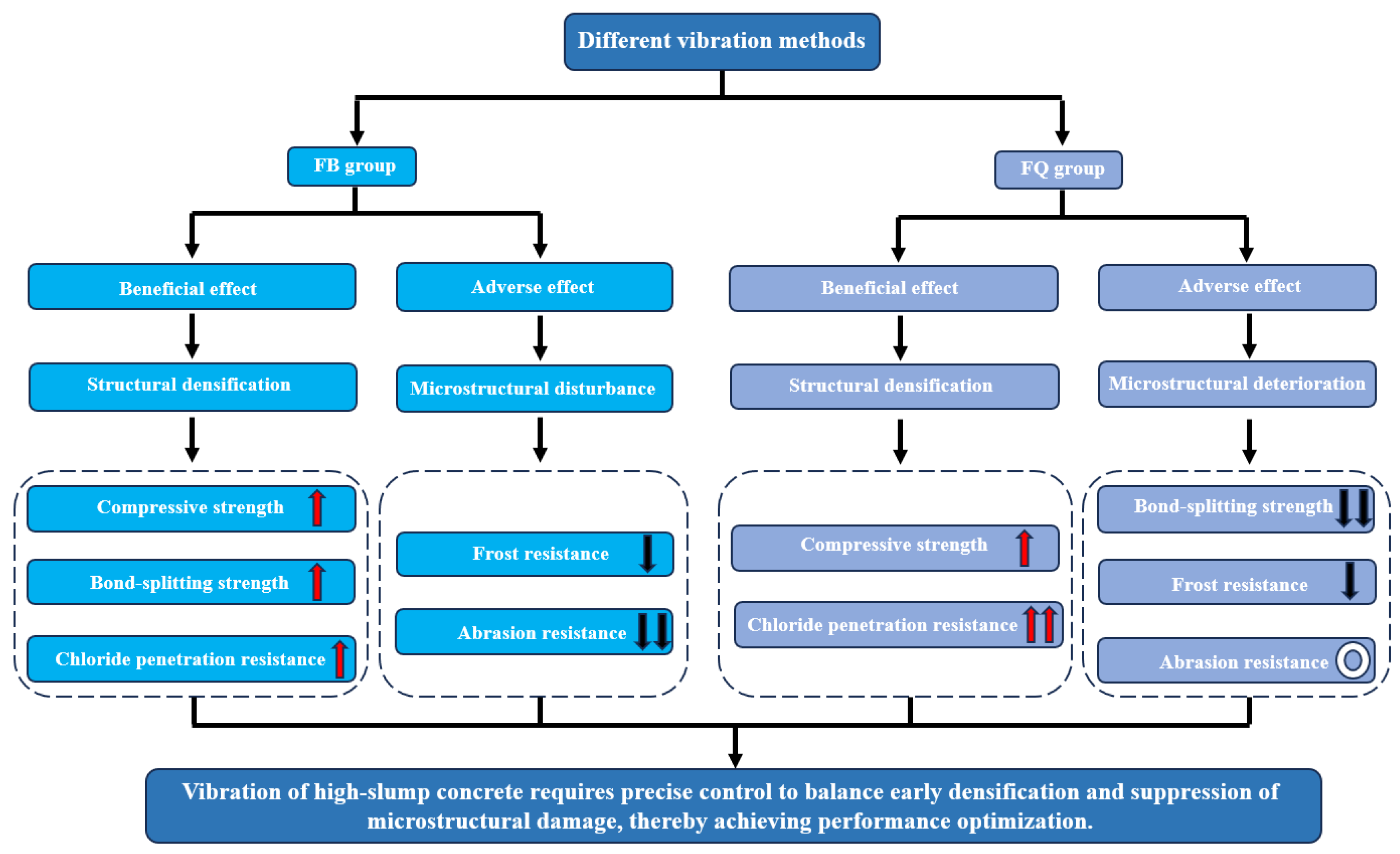

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zheng, S.; Lu, X.; Zhao, J.; He, R.; Chen, H.; Geng, Y. Influence of industrial by-product sulfur powder on properties of cement-based composites for sustainable infrastructures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 367, 130171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Yang, Z.; Gan, V.J.L.; Chen, H.; Cao, D. Mechanism of nano-silica to enhance the robustness and durability of concrete in low air pressure for sustainable civil infrastructures. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 321, 128783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Guo, Y. In-site health monitoring of cement concrete pavements based on optical fiber sensing technology. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Yang, J.; Liao, B.; Ma, S.; Zhong, H.; Lei, J. Investigation on the concrete strength performance of underlying tunnel structure subjected to train-induced dynamic loads at an early age. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 337, 127622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Pan, B.; Zhou, C.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Li, J. Study of interfacial transition zones between magnesium phosphate cement and Portland cement concrete pavement. J. Traffic Transp. Eng. (Engl. Ed.) 2024, 11, 523–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Chen, Y.; Deng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, M. Toughness improvement mechanism and evaluation of cement concrete for road pavement: A review. J. Road Eng. 2023, 3, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wu, H.; Li, L.; He, R.; Guo, H. Confined photocatalysis and interfacial reconstruction for durability wettability in road markings. Colloids Surf. A: Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2026, 729, 138902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, C.; Vorwagner, A.; Manninger, T.; Klackl, S.; Krispel, S.; Stadler, C.; Kleiser, M. Auswirkungen von Verkehrserschütterungen auf jungen Beton: Teil 2. Beton- Stahlbetonbau 2025, 120, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Yan, C.; Wang, X.; Wang, H. Effects of Vehicle-Induced Vibrations on the Tensile Performance of Early-Age PVA-ECC. Materials 2019, 12, 2652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Zhu, C.; Song, J.; Chen, B. Study on Microscopic Damage of Anti-disturbance Concrete during Splicing Maintenance under Normal Traffic Condition. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. 2024, 41, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.; Park, S. Effect of vehicle-induced vibrations on early-age concrete during bridge widening. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralbovsky, M.; Vorwagner, A.; Kleiser, M.; Kozakow, T.; Geier, R. Verkehrsschwingungen bei Betonierarbeiten auf bestehenden Straßenbrücken. Beton-Stahlbetonbau 2020, 115, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basler, F.; Mähner, D.; Fischer, O.; Hilbig, H. Influence of early-age vibration on concrete strength. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 6505–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, C.; Manninger, T.; Vorwagner, A.; Klackl, S.; Krispel, S.; Stadler, C.; Kleiser, M. Experimental study on the impact of traffic-induced vibrations on early-age concrete. Struct. Concr. 2025, suco.70143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Cui, W.; Qi, L. DEM study on the response of fresh concrete under vibration. Granul. Matter 2022, 24, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zheng, Y.; Rong, Z.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, J.; Yang, B. Impact of early-age vibration on the permeability and microstructure of mature-age concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 453, 139124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; Fu, Z. Effect of Vibrations at Early Concrete Ages on Concrete Segregation and Strength. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2016, 42, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Y.; Taylor, P. Effect of Controlled Vibration Dynamics on Concrete Mixtures. ACI Mater. J. 2021, 118, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Liu, Q.; Meng, Z.; Chen, M.; Li, W.; Šavija, B. Influence of coarse aggregate settlement induced by vibration on long-term chloride transport in concrete: A numerical study. Mater. Struct. 2022, 55, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Fu, J.; Zhao, Q. Sulfate Attack Resistance of Concrete Subjected to Disturbance in Hardening Stage. Mater. Rev. 2018, 32, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsh, S.; Darwin, D. Effects of Traffic Induced Vibrations on Bridge Deck Repairs; Bridge NCHRP Synthesis of Highway Practice; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Ng, P.L.; Kwan, A.K.H. Effects of traffic vibration on curing concrete stitch: Part II—Cracking, debonding and strength reduction. Eng. Struct. 2007, 29, 2881–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Yang, R.; Wen, J.; Tang, R.; Wang, Z. Study on the Influence of Vehicle-Bridge Coupled Vibration on the Performance of Sulphoaluminate Cement-based Concrete Repair Materials. Mater. Rev. 2019, 33, 288–292. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X. Study on the Anti-disturbance of Concrete in the Setting and Hardening Period. China Concer. Cem. Prod. 2009, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgil, A.; Ozturk, B.; Bilgil, H. A numerical approach to determine viscosity-dependent segregation in fresh concrete. Appl. Math. Comput. 2005, 162, 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.H.; Griffith, A.M.; Hanzic, L.; Wang, Q.; Ho, J.C.M. Interdependence of passing ability, dilatancy and wet packing density of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 270, 121440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Improvement of Behaviors of Reinforced Concrete for Bridge. Mater. Rev. 2012, 26, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Park, W.; Yang, E. Evaluation of concrete durability due to carbonation in harbor concrete structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 48, 1045–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cai, F.; Liang, T. Experimental Evaluation of the Influence of Early Disturbance on the Performance of Basalt Fiber Concrete. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8853442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, H.; Wang, F.; Zhao, Q. Influence of Disturbance in Hardening Stage on Mechanical Properties of Concrete. J. Build. Mater. 2016, 19, 631–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Y. Effect of vehicle-bridge interaction vibration on young concrete. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2015, 19, 151–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fox, P.J. Numerical Investigation of the Geosynthetic Reinforced Soil–Integrated Bridge System under Static Loading. J. Geotech. Geoenviron. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, S.T.; Kowalsky, M.J.; Seracino, R.; Nau, J.M. Repair of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Columns Containing Buckled and Fractured Reinforcement by Plastic Hinge Relocation. J. Bridge Eng. 2014, 19, A4013001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chai, H.; Hu, Y.; He, R.; Wang, Z. Feasibility study on superabsorbent polymer (SAP) as internal curing agent for cement-based grouting material. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50164-2011; Standard for Quality Control of Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2011.

- JG/T 245-2009; Vibrating Table for Concrete Test. Standards Press of China: Beijing, China, 2009.

- JTG 3420-2020; Testing Methods of Cement and Concrete for Highway Engineering. People’s Communications Publishing House Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB/T 50080-2016; Standard for Test Method of Performance on Ordinary Fresh Concrete. China Architecture & Building Press: Beijing, China, 2016.

- EL Afandi, M.; Yehia, S.; Landolsi, T.; Qaddoumi, N.; Elchalakani, M. Concrete-to-concrete bond Strength: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 363, 129820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valipour, M.; Khayat, K.H. Debonding test method to evaluate bond strength between UHPC and concrete substrate. Mater. Struct. 2020, 53, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Shen, A.; Zhai, C.; Li, P. Abrasion resistance and microstructure of road concrete under different design parameters. J. Chang. Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 36, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, X.; Min, Y.; Luo, H.; Chen, Y.; Li, W. Study on performance improvement of ultra-high performance concrete by vibration mixing. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 327, 126823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Zhang, C.; Xu, X.; Shen, Y.; Jia, H.; Sun, C. Effects of Cyclic Freeze–Thaw on the Steel Bar Reinforced New-to-Old Concrete Interface. Molecules 2020, 25, 1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhang, X.; Hooton, R.D.; Zhang, X. Effects of interface roughness and interface adhesion on new-to-old concrete bonding. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 151, 582–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, H.; Yang, X.; Li, S.; Liang, W. Experimental study on the blasting-vibration safety standard for young concrete based on the damage accumulation effect. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 217, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basheer, L.; Kropp, J.; Cleland, D.J. Assessment of the durability of concrete from its permeation properties: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2001, 15, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. Effect of Early Disturbance on Properties of Concrete. Master’s Thesis, Yanshan Universit, Qinhuangdao, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Ren, Q.; Yuan, Z. Effects of Vehicle-Bridge Coupled Vibration on Early-Age Properties of Concrete and its Damage Mechanism. J. Build. Mater. 2015, 18, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltran, M.; Nassif, H. Field Monitoring of Rebar Debonding in Concrete Bridge Decks under Traffic-Induced Vibrations. Transp. Res. Rec. J. Transp. Res. Board 2014, 2407, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. Mechanism Analysis of the Effect of Disturbance on the Compressive Strength of Concrete. North. Commun. 2018, 5, 59–63+66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. The Impact of Traffic-Induced Bridge Vibration on Rapid Repairing High-Performance Concrete for Bridge Deck Pavement Repairs. Master’s Thesis, Shijiazhuang Tiedao University, Shi Jiazhuang, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Qi, L.; Ye, J.; Sun, J. Impact of Vibration-Induced Deformation Disturbance on Performance of Concrete in Integrated New-Old Bridge Connections. J. Highw. Transp. Res. Dev. (Appl. Technol. Ed.) 2017, 13, 279–282. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, D.; Mu, S.; Liu, J.; Shi, L.; Liu, K.; Liu, G. Research on the Chloride Migration Coefficient Evolution of Concrete After Being Disturbed. China Concr. Cem. Prod. 2020, 10, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J. Based on the Vehicle Bridge Coupling Vibration of Cast-In-Situ Concrete Durability Study. Master’s Thesis, Chongqing Jiaotong University, Chong Qing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Normal Consistency/% | Specific Surface Area (m2/kg) | Setting Time (min) | Compressive Strength (MPa) | Flexural Strength (MPa) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | Final | 3d | 28d | 3d | 28d | ||

| 24.7 | 345 | 115 | 195 | 24.3 | 56.6 | 4.8 | 8.6 |

| Cement (kg/m3) | Water (kg/m3) | w/c | Sand (kg/m3) | Aggregate (kg/m3) | Polycarboxylate Superplasticizer (kg/m3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5–10 mm | 10–20 mm | |||||

| 520 | 156 | 0.3 | 674 | 330 | 770 | 3 |

| Test Group | Definition |

|---|---|

| F | Specimens in this group remained in a static environment from casting to final setting time |

| FB | Specimens in this group were subjected to vibration from the initial setting time to the final setting time |

| FQ | Specimens in this group were subjected to vibration continuously from casting until the final setting time |

| Group | Coulomb Electric Flux (C) | Resistance to Chloride Ion Permeability |

|---|---|---|

| F | 1578 | Low permeability |

| FB | 1044 | Low permeability |

| FQ | 695 | Very low permeability |

| Group | Abrasion Quality (kg/m2) |

|---|---|

| F | 0.177 |

| FB | 0.311 |

| FQ | 0.177 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, S.; Shen, J.; Guo, H.; Zheng, X.; He, R. Performance Evolution of High-Slump Concrete Under Vibration: Influence of Vibration Timing on Mechanical, Durability, and Interfacial Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235389

Sun S, Shen J, Guo H, Zheng X, He R. Performance Evolution of High-Slump Concrete Under Vibration: Influence of Vibration Timing on Mechanical, Durability, and Interfacial Properties. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235389

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Shiwei, Junmin Shen, Haoqin Guo, Xinxin Zheng, and Rui He. 2025. "Performance Evolution of High-Slump Concrete Under Vibration: Influence of Vibration Timing on Mechanical, Durability, and Interfacial Properties" Materials 18, no. 23: 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235389

APA StyleSun, S., Shen, J., Guo, H., Zheng, X., & He, R. (2025). Performance Evolution of High-Slump Concrete Under Vibration: Influence of Vibration Timing on Mechanical, Durability, and Interfacial Properties. Materials, 18(23), 5389. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235389