Influence of Simulated Radioactive Waste Resins on the Properties of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement

Abstract

1. Introduction

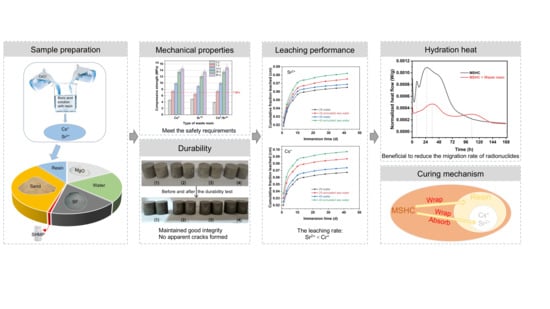

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Sample Preparation

2.2. Experimental Methods

3. Results

3.1. Mechanical Properties

3.1.1. Compressive Strength

3.1.2. Impact Resistance

3.2. Durability

3.2.1. Freeze-Thaw Resistance

3.2.2. Soaking Resistance

3.3. Leaching Performance

3.4. Microstructural Analyses

3.4.1. Hydration Heat

3.4.2. XRD

3.4.3. TG

3.4.4. SEM

3.4.5. MIP

4. Discussion

4.1. Impact of Waste Resins on MSHC

4.1.1. Influence of Incorporating Waste Resins on the Mechanical and Durability Performance of the MSHC-Solidified Body

4.1.2. Influence of Incorporating Waste Resin on the Microstructural Mechanism of the MSHC-Solidified Body

4.2. Factors Affecting Ion Leaching Performance and Leaching Models on MSHC-Solidified Body Containing Waste Resins

4.2.1. Factors Affecting Ion Leaching Performance on MSHC-Solidified Body Containing Waste Resins

4.2.2. Leaching Models of MSHC-Solidified Body Containing Waste Resins

4.3. Immobilization Mechanism of MSHC on Waste Resins and Nuclide Ions

4.4. Limitations and Applicability

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dai, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, F.; Cao, S.; Wang, S.; Yang, Y.; Dong, J. Development and economic analysis of fast breeder reactor- pressurized water reactor’s two-component nuclear power system. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2026, 190, 106011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, C.-L. Assessment of the radiological impact of a melting furnace explosion in a radioactive waste treatment facility on the multi-unit nuclear power plant site. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, M.; Li, B.; Pan, Y.; Yang, L. Thermal degradation of spent cation exchange resin with fixatives or metal ion catalysts: Insights from experiments, thermodynamics and kinetics. Thermochim. Acta 2025, 754, 180174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, J. Solidification of radioactive wastes by cement-based materials. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2021, 141, 103957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yi, L.; Wang, G.; Li, L.; Lu, L.; Guo, L. Experimental investigation on gasification of cationic ion exchange resin used in nuclear power plants by supercritical water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Bi, H.; Yu, Y.; Fu, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.; Hou, P.; Cheng, X. Low leaching characteristics and encapsulation mechanism of Cs+ and Sr2+ from SAC matrix with radioactive IER. J. Nucl. Mater. 2021, 544, 152701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaper, H.; Blaauboer, R. A probabilistic risk assessment for accidental releases from nuclear power plants in Europe. J. Hazard. Mater. 1998, 61, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Seo, E.-A.; Kim, D.-G.; Chung, C.-W. Utilization of recycled cement powder as a solidifying agent for radioactive waste immobilization. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 289, 123126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plecas, I.; Pavlovic, R.; Pavlovic, S. Leaching behavior of 60Co and 137Cs from spent ion exchange resins in cement–bentonite clay matrix. J. Nucl. Mater. 2004, 327, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wei, Y.; Gao, Y.; Liu, X.; Hao, Z.; Dong, L. Laboratory evaluation on performance of emulsified asphalt modified by reclaimed ion exchange resin. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 364, 129994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plećaš, I.; Perić, A.; Glodic, S.; Kostadinović, A. Leaching studies of 137Cs from ion-exchange resin incorporated in cement or bitumen. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. Lett. 1992, 166, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwaszko, J.; Zajemska, M.; Zawada, A.; Szwaja, S.; Poskart, A. Vitrification of environmentally harmful by-products from biomass torrefaction process. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 249, 119427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanito, R.C.; Bernuy-Zumaeta, M.; You, S.-J.; Wang, Y.-F. A review on vitrification technologies of hazardous waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 316, 115243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vienna, J.D. Nuclear Waste Vitrification in the United States: Recent Developments and Future Options. Int. J. Appl. Glas. Sci. 2010, 1, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Wang, J. Advances in cement solidification technology for waste radioactive ion exchange resins: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 135, 443–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Milestone, N.; Hayes, M. An alternative to Portland Cement for waste encapsulation—The calcium sulfoaluminate cement system. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 136, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Pang, B. Mechanical property and toughening mechanism of water reducing agents modified graphene nanoplatelets reinforced cement composites. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 226, 699–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagosi, S.; Csetenyi, L.J. Immobilization of caesium-loaded ion exchange resins in zeolite-cement blends. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 479–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhao, G.; Wang, J. Solidification of low-level-radioactive resins in ASC-zeolite blends. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2005, 235, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, M.; Nishi, T.; Kikuchi, M. Solidification of Spent Ion Exchange Resin Using New Cementitious Material, (II): Improvement of Resin Content by Fiber Resin reed Cement. J. Nucl. Sci. Technol. 1992, 29, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Pan, L.K.; Chang, B.D.; Chou, D.S. Optimization for solidification of low-level-radioactive resin using Taguchi analysis. Waste Manag. 2001, 21, 767–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; Qin, X. Influence of H2O/MgCl2 molar ratio on strength properties of the magnesium oxychloride cement solidified soft clay and its associated mechanisms. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 393, 132018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.; Ni, W.; Tsang, D.C. Treatment of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: State-of-the-art technologies and future perspectives. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 411, 125132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsiske, M.R.; Debus, C.; Di Lorenzo, F.; Bernard, E.; Churakov, S.V.; Ruiz-Agudo, C. Immobilization of (Aqueous) Cations in Low pH M-S-H Cement. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Cheeseman, C.; Vandeperre, L. Development of low pH cement systems forming magnesium silicate hydrate (M-S-H). Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Li, T.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Zhi, S.; Jia, Y.; Cheeseman, C.R. Immobilization of Radionuclide 133Cs by Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement. Materials 2019, 13, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, H.K.; Bishay, A.F. Uranium uptake from acidic solutions using synthetic titanium and magnesium based adsorbents. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 2010, 283, 765–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Cho, D.-W.; Tsang, D.C.; Yang, J.; Hou, D.; Baek, K.; Kua, H.W.; Poon, C.-S. Novel synergy of Si-rich minerals and reactive MgO for stabilisation/solidification of contaminated sediment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 365, 695–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walling, S.A.; Kinoshita, H.; Bernal, S.A.; Collier, N.C.; Provis, J.L. Structure and properties of binder gels formed in the system Mg(OH)2–SiO2–H2O for immobilisation of Magnox sludge. Dalton Trans. 2015, 44, 8126–8137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Vandeperre, L.J.; Cheeseman, C.R. Formation of magnesium silicate hydrate (M-S-H) cement pastes using sodium hexametaphosphate. Cem. Concr. Res. 2014, 65, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zou, J.; Li, Y.; Jia, Y.; Cheeseman, C.R. Stabilization/Solidification of Strontium Using Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement. Processes 2020, 8, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 14569.1-2011; Performance Requirements for Low and Intermediate Level Radioactive Waste Form-Cemented Waste Form. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2011. (In Chinese)

- Lu, X.; Ding, Y.; Dan, H.; Wen, M.; Mao, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. High capacity immobilization of TRPO waste by Gd2Zr2O7 pyrochlore. Mater. Lett. 2014, 136, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wei, J.; Yu, Q. Effect of the MgO/Silica Fume Ratio on the Reaction Process of the MgO–SiO2–H2O System. Materials 2018, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Lin, L.; Yu, J.; Tang, H.; Qin, J.; Qian, J. Performance of magnesium silicate hydrate cement modified with dipotassium hydrogen phosphate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 323, 126389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonat, C.; He, S.; Li, J.; Unluer, C.; Yang, E.-H. Strain hardening magnesium-silicate-hydrate composites (SHMSHC) reinforced with short and randomly oriented polyvinyl alcohol microfibers. Cem. Concr. Res. 2021, 142, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, Q.; Lv, Y.; Leng, D.; Jiang, D.; He, C.; Wu, K.; Dan, J. Influence of curing conditions on hydration of magnesium silicate hydrate cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 361, 129648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anagnostopoulos, C.A. Effect of different superplasticisers on the physical and mechanical properties of cement grouts. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 50, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Meng, X.; Liu, W.; Ren, Y. Study on the properties of C-S-H/epoxy nanocomposite structure doped with silica nanoparticles. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 74, 106894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yan, P. Hydration kinetics of the epoxy resin-modified cement at different temperatures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 150, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, B.; Sonat, C.; Yang, E.-H.; Tan, M.J.; Unluer, C. Use of magnesium-silicate-hydrate (M-S-H) cement mixes in 3D printing applications. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 117, 103901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, M.; Li, C.; Han, M.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Q. Metakaolin-Reinforced Sulfoaluminate-Cement-Solidified Wasteforms of Spent Radioactive Resins—Optimization by a Mixture Design. Coatings 2022, 12, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.A.; Zaki, A. Assessment of the leaching characteristics of incineration ashes in cement matrix. Chem. Eng. J. 2009, 155, 698–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K.; Ono, Y. Leaching characteristics of stabilized/solidified fly ash generated from ash-melting plant. Chemosphere 2008, 71, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, R.A.; El Abidin, D.Z.; Abou-Shady, H. Assessment of strontium immobilization in cement–bentonite matrices. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 228, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, D.; Glasser, F. Synthesis and characterisation of magnesium silicate hydrate gels. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brew, D.; Glasser, F. The magnesia–silica gel phase in slag cements: Alkali (K, Cs) sorption potential of synthetic gels. Cem. Concr. Res. 2005, 35, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasser, F. Application of inorganic cements to the conditioning and immobilisation of radioactive wastes. In Handbook of Advanced Radioactive Waste Conditioning Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 67–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.M. Stabilization/solidification of hazardous and radioactive wastes with alkali-activated cements. J. Hazard. Mater. 2006, 137, 1656–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojovan, M.I.; Varlackova, G.A.; Golubeva, Z.I.; Burlaka, O.N. Long-term field and laboratory leaching tests of cemented radioactive wastes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2011, 187, 296–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Composition (wt.%) | MgO | CaO | SO3 | SiO2 | P2O5 | Fe2O3 | Al2O3 | MnO | K2O | Na2O |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MgO | 95.80 | 2.04 | 0.73 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.01 | — |

| SF | 0.26 | 0.83 | 0.15 | 97.09 | 0.24 | 0.11 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.80 | 0.12 |

| Category | Mass Loss Rate (%) | Compressive Strength Loss Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|

| MSHC | 0.12 | 9.41 |

| MSHC + Cs+ | 0.26 | 12.69 |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | 0.24 | 9.83 |

| MSHC + Cs+/Sr2+ | 0.32 | 11.85 |

| Category | Before Soaking (MPa) | After Soaking (MPa) | After Soaking/Before Soaking |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSHC | 45.36 | 54.22 | 1.20 |

| MSHC + Cs+ | 14.42 | 15.63 | 1.08 |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | 13.15 | 14.60 | 1.11 |

| MSHC + Cs+/Sr2+ | 9.48 | 11.83 | 1.25 |

| Curing Age (Days) | Category | Content (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mg(OH)2 | M-S-H Gel | ||

| 7 | MSHC | 17.953 | 13.790 |

| MSHC + Cs+ | 21.413 | 13.412 | |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | 22.742 | 11.153 | |

| MSHC + Cs+/Sr2+ | 18.459 | 13.128 | |

| 28 | MSHC | 12.231 | 21.283 |

| MSHC + Cs+ | 13.924 | 20.051 | |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | 17.546 | 19.878 | |

| MSHC + Cs+/Sr2+ | 15.429 | 21.132 | |

| Category | Average Pore Size (nm) | Median Pore Size (nm) | Total Pore Area (m2/g) | Porosity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSHC | 21.69 | 7.20 | 31.97 | 15.28 |

| MSHC + Cs+ | 34.40 | 19.80 | 62.68 | 37.87 |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | 58.30 | 19.10 | 40.09 | 42.11 |

| MSHC + Cs+/Sr2+ | 27.60 | 14.50 | 71.95 | 35.14 |

| Category | Leaching Models | Parameters | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| k | C | D | U0 | |||

| MSHC + Cs+ | FRM | 0.17825 | 0.02139 | - | - | 0.99124 |

| FRDM | −0.01901 | 0.01154 | 1.68759 × 10−4 | - | 0.96855 | |

| DDIM | - | −1.511 × 10−4 | 3.19733 × 10−4 | −0.00247 | 0.98675 | |

| FRDIM | 0.23982 | 0.00873 | - | 1.72368 × 10−4 | 0.99883 | |

| FRDDIM | −1.8459 × 10−6 | −1.51279 × 10−4 | 3.19735 × 10−4 | −0.00247 | 0.98675 | |

| MSHC + Sr2+ | FRM | 0.18426 | 0.01298 | - | - | 0.99354 |

| FRDM | −0.01877 | 0.00663 | 1.91572 × 10−4 | - | 0.96887 | |

| DDIM | - | −0.00237 | 3.62276 × 10−4 | −0.00289 | 0.98425 | |

| FRDIM | 0.34668 | 0.00795 | - | 1.42095 × 10−4 | 0.99891 | |

| FRDDIM | −1.348752 × 10−5 | −0.00237 | 3.62287 × 10−4 | −0.00289 | 0.98425 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, E.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Yang, J.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, T. Influence of Simulated Radioactive Waste Resins on the Properties of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement. Materials 2025, 18, 5385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235385

Sun E, Gao H, Li M, Yang J, Qiao Y, Zhang T. Influence of Simulated Radioactive Waste Resins on the Properties of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235385

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Enyu, Huinan Gao, Min Li, Jie Yang, Yu Qiao, and Tingting Zhang. 2025. "Influence of Simulated Radioactive Waste Resins on the Properties of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement" Materials 18, no. 23: 5385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235385

APA StyleSun, E., Gao, H., Li, M., Yang, J., Qiao, Y., & Zhang, T. (2025). Influence of Simulated Radioactive Waste Resins on the Properties of Magnesium Silicate Hydrate Cement. Materials, 18(23), 5385. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235385