3.2. Three Points Flexural Tests

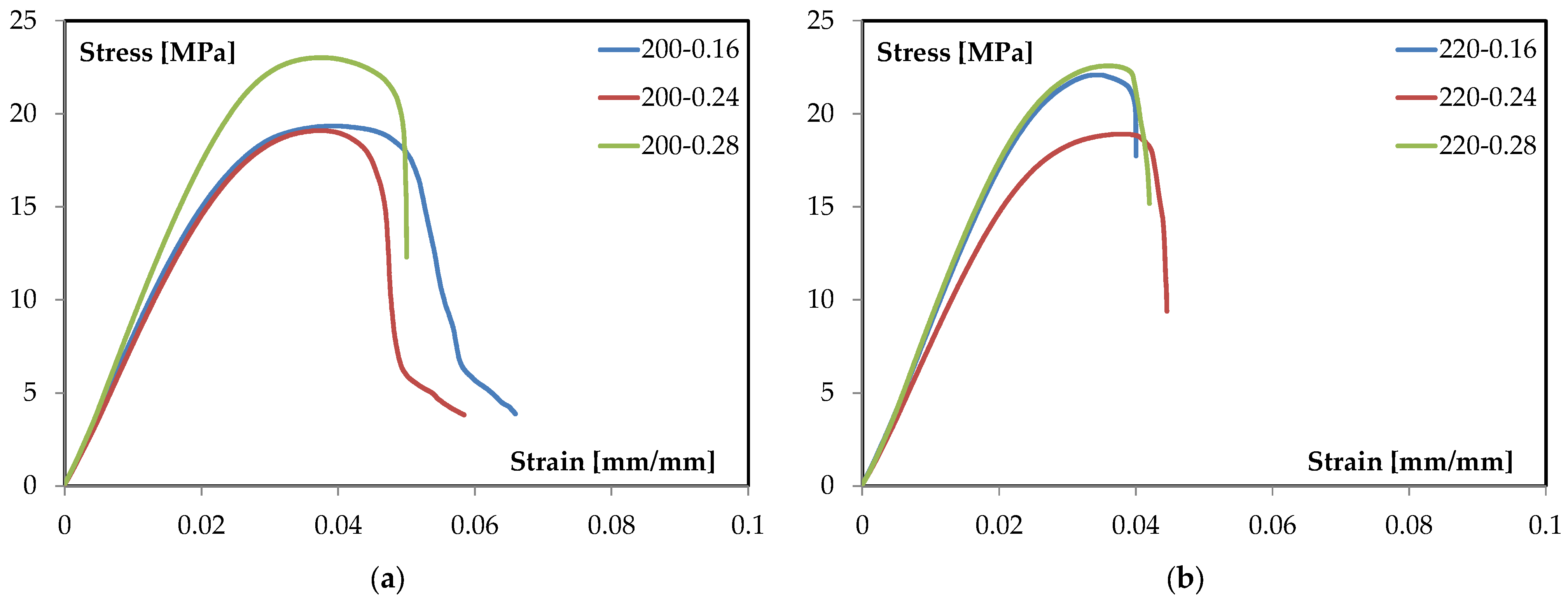

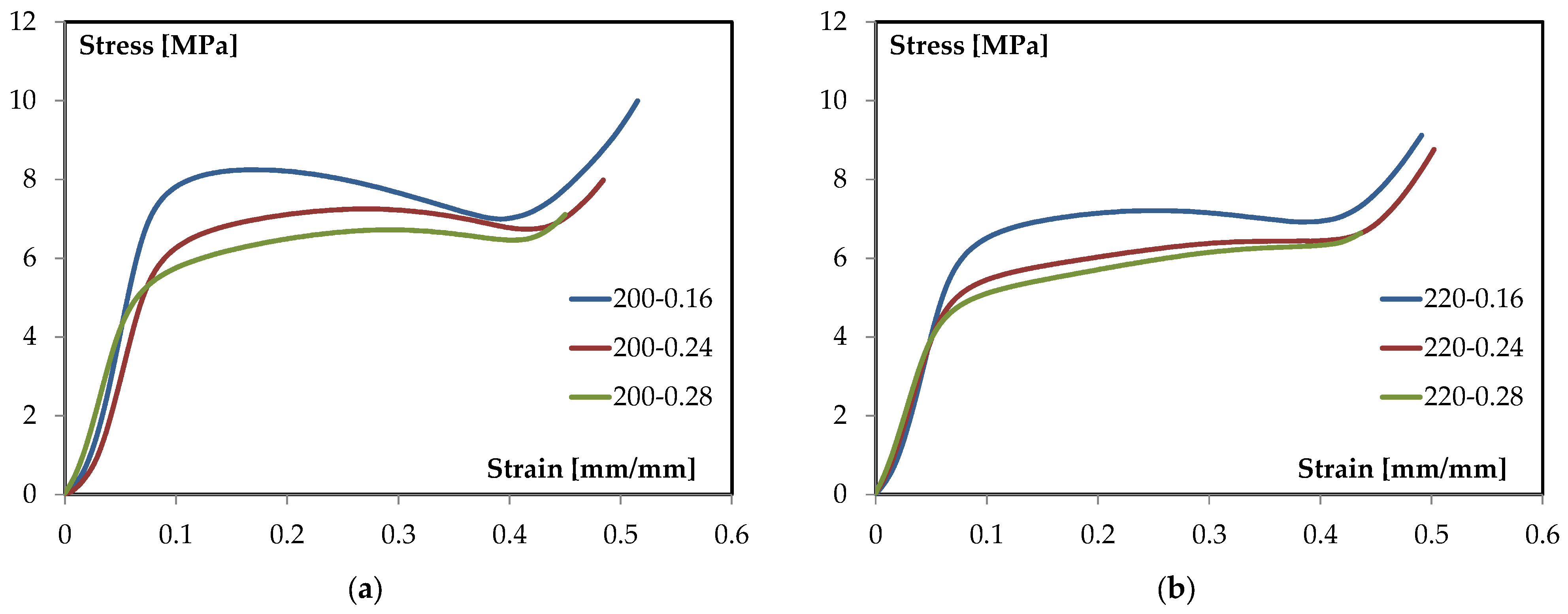

The flexural response of the TPMS-sandwich specimens is examined through representative stress–strain curves obtained under three-point bending. The analysis focuses on the characteristic regions of the curves and on how processing variables affect stiffness, peak stress, and post-peak evolution. To this end,

Figure 2a reports the family of curves at 200 °C for different layer heights, while

Figure 2b presents the corresponding set at 220 °C. The two figures are discussed comparatively to isolate the role of layer height at a fixed temperature and the role of temperature at a fixed geometry, enabling clear attribution of trends to process conditions. Quantitative observations are drawn directly from the plotted data, and qualitative interpretation is limited to the shape and progression of the curves.

The representative three-point-bending response of these TPMS sandwiches shows: (i) an initial linear region where the slope (apparent flexural modulus) is nearly constant; (ii) a nonlinear rise to a distinct maximum (peak stress), where the tangent stiffness drops to approximately 0; and (iii) a post-peak segment where the load-carrying capacity decreases with strain. This staging is consistent with standard ASTM D790 characterization and serves as the template for interpreting all subsequent curves in this study [

29]. This common set of descriptors enables a consistent, parameter-by-parameter comparison and prevents over-interpretation of local fluctuations in the raw signal. With this framework in place, the family of curves at 200 °C can be examined to quantify how varying only the layer height (0.16, 0.24, and 0.28 mm) modulates these metrics under otherwise identical conditions (see

Figure 2a).

All three curves closely overlay at very small strain, indicating comparable global stiffness in the purely elastic segment. Slight differences emerge as strain increases: the 0.28 mm condition tends to maintain a higher instantaneous slope for longer before deviating from linearity, whereas the 0.16 mm and 0.24 mm conditions depart toward nonlinearity earlier. This suggests a modest stiffening benefit at equal temperature when the layer height is increased. Similar sensitivities of elastic and early-plastic responses to printable bead geometry and inter-bead continuity have been documented for PLA under bending [

44,

45].

At 200 °C, the maximum stress increases with layer height: 0.16 mm and 0.24 mm reach similar peaks (~19–20 MPa), while 0.28 mm peaks higher (about 23–24 MPa). The onset of nonlinearity occurs at comparable strain for all three batches, but the 0.28 mm trace sustains a larger stress increment before reaching the maximum. This “higher-peak at larger layer height” trend aligns with studies identifying layer height as a primary factor for flexural strength in FFF PLA, due to its influence on road cross-section, road overlap, and the effective load-bearing area of the outer skins [

45,

46].

Beyond the maximum, the softening slope steepens progressively from 0.16 to 0.24 to 0.28 mm. The 0.16 mm condition exhibits the longest tail (greater strain capacity after peak), while 0.28 mm shows the sharpest drop (shorter usable ductility). In practical terms, increasing layer height at 200 °C trades some post-peak tolerance for higher peak stress. This trade-off is coherent with broader MEX/FFF literature where coarser vertical discretization reduces the number of interlayer planes, alters neck geometry between adjacent rasters, and generally shifts the balance toward higher maxima with less gradual post-peak decay [

44,

45].

Well-established processing–structure relationships explain the observed family of curves at 200 °C.

Larger layer height reduces the number of layer interfaces across the thickness and increases the cross-section of each deposited road. Under bending, this can increase the effective load-bearing area of the outer skins and shift the peak upward, consistent with the higher maxima at 0.28 mm. Multiple investigations rank layer height among the most influential parameters for flexural strength in PLA parts, often ahead of raster angle when other settings are held constant [

46].

The softening portion of the curve is highly sensitive to the continuity and morphology of adjacent filaments (overlap ratio, local necking, and bead geometry), which are themselves governed by layer height and temperature. Studies correlating temperature field, interlayer coalescence, and elastic-modulus trends in PLA confirm that processing conditions which enhancing filament fusion tend to increase maxima and alter the subsequent decay of the stress–strain trace [

44,

47,

48].

While the sandwich architecture here is sheet-based TPMS, the macroscopic stress–strain shape under bending (linear → peak → softening) remains consistent with prior gyroid-focused studies combining experiments and simulations. Those works emphasize that, at a fixed core density, process parameters that affect the skins and skin–core continuity dominate the global bending curve metrics, consistent with the trends observed at 200 °C [

5].

Similarly, the family of curves at 220 °C can be examined (see

Figure 2b).

In the small-strain segment, the three traces essentially overlap, indicating comparable apparent flexural stiffness at 220 °C across layer heights. The departure from linearity occurs at nearly the same strain for all batches (≈0.025–0.03 mm/mm), suggesting that at this temperature, early-stage stiffness is weakly sensitive to vertical discretization and is mainly governed by the consolidated skins and the gyroid core acting as a shear spacer. The modest tendency of the 0.16 mm and 0.28 mm curves to maintain a higher instantaneous slope up to the onset of nonlinearity is observable and is consistent with temperature-assisted interroad coalescence improving effective skin continuity at 220 °C. Such temperature effects on elastic response and bonding quality in FFF PLA are documented by process-structure studies that track the temperature field and its impact on neck growth and modulus [

48].

The maximum stress shows clear stratification: the 0.28 mm condition reaches the highest peak (≈22–23 MPa), the 0.16 mm curve follows closely (≈21–22 MPa), and the 0.24 mm trace exhibits a distinctly lower maximum (≈18–19 MPa). Strain at peak clusters around ≈0.038–0.042 mm/mm for all three batches. The strength ranking aligns with the role of layer height as a primary factor for flexural strength in material-extrusion PLA, via its effect on road cross-section and the effective load-bearing area of the skins; elevated nozzle temperature further promotes interlayer diffusion and coalescence, which can sustain higher peak stresses when geometric conditions are favorable [

44,

45].

Beyond the maximum, all curves display a relatively short post-peak segment at 220 °C. The 0.24 mm case shows the steepest drop (shortest usable deformation after peak), while 0.16 and 0.28 mm retain slightly longer but still limited tails. The compactness of the softening region at this temperature indicates that, once the maximum is reached, residual load-carrying capacity decays rapidly for all layer heights. The sensitivity of the softening behavior to processing temperature, through its influence on filament wetting, interfacial consolidation, and the continuity of adjacent roads, is consistent with controlled studies that connect higher nozzle temperatures with improved maxima yet sharper post-peak evolution depending on the printed morphology [

44,

48].

Material-extrusion studies consistently report that (i) increasing layer height can raise flexural strength by enlarging the road cross-section and reducing the number of interlayer planes across the thickness, and (ii) higher extrusion temperature lowers melt viscosity, enhances interlayer diffusion, and strengthens interfacial bonding-factors that influence both the location of the peak and the subsequent decay of the curve. These mechanisms underpin the observed family of curves at 220 °C and align with parametric investigations on PLA and architected-core systems where skins dominate the macroscopic bending response [

5,

45].

Table 4 presents, in a compact form, the key features extracted from the stress–strain families in

Figure 2a,b, using a common set of descriptors (peak stress and qualitative post-peak character) for direct cross-comparison.

Taken together, the entries show that at 200 °C the response scales monotonically with layer height—0.28 mm delivers the highest peak with the shortest post-peak segment, 0.16 mm the lowest peak with the most extended tail, and 0.24 mm remains intermediate—whereas at 220 °C the ranking changes subtly: 0.28 mm retains the highest peak (≈22–23 MPa) and a short post-peak, 0.16 mm follows closely with a similarly compact softening, and 0.24 mm exhibits both a lower maximum and the steepest decay. Comparing temperatures at fixed geometry, raising T from 200 °C to 220 °C tends to compress the post-peak region for all cases, increases the peak for 0.16 mm, leaves 0.28 mm broadly high but slightly reduced, and penalizes 0.24 mm. Operationally, the coarse discretization (0.28 mm) is the most effective for maximizing peak stress at both temperatures, the fine discretization (0.16 mm) offers greater post-peak deformation capacity at 200 °C but converges to a short tail at 220 °C, and the mid-height setting (0.24 mm) emerges as the least robust when the temperature is elevated.

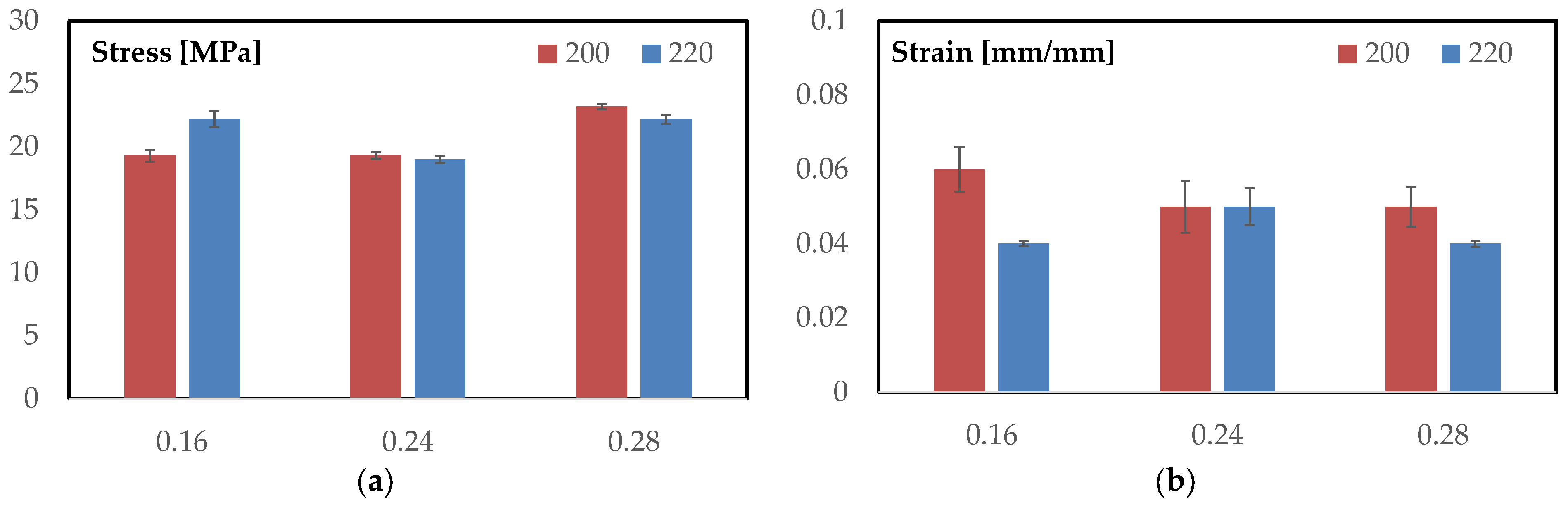

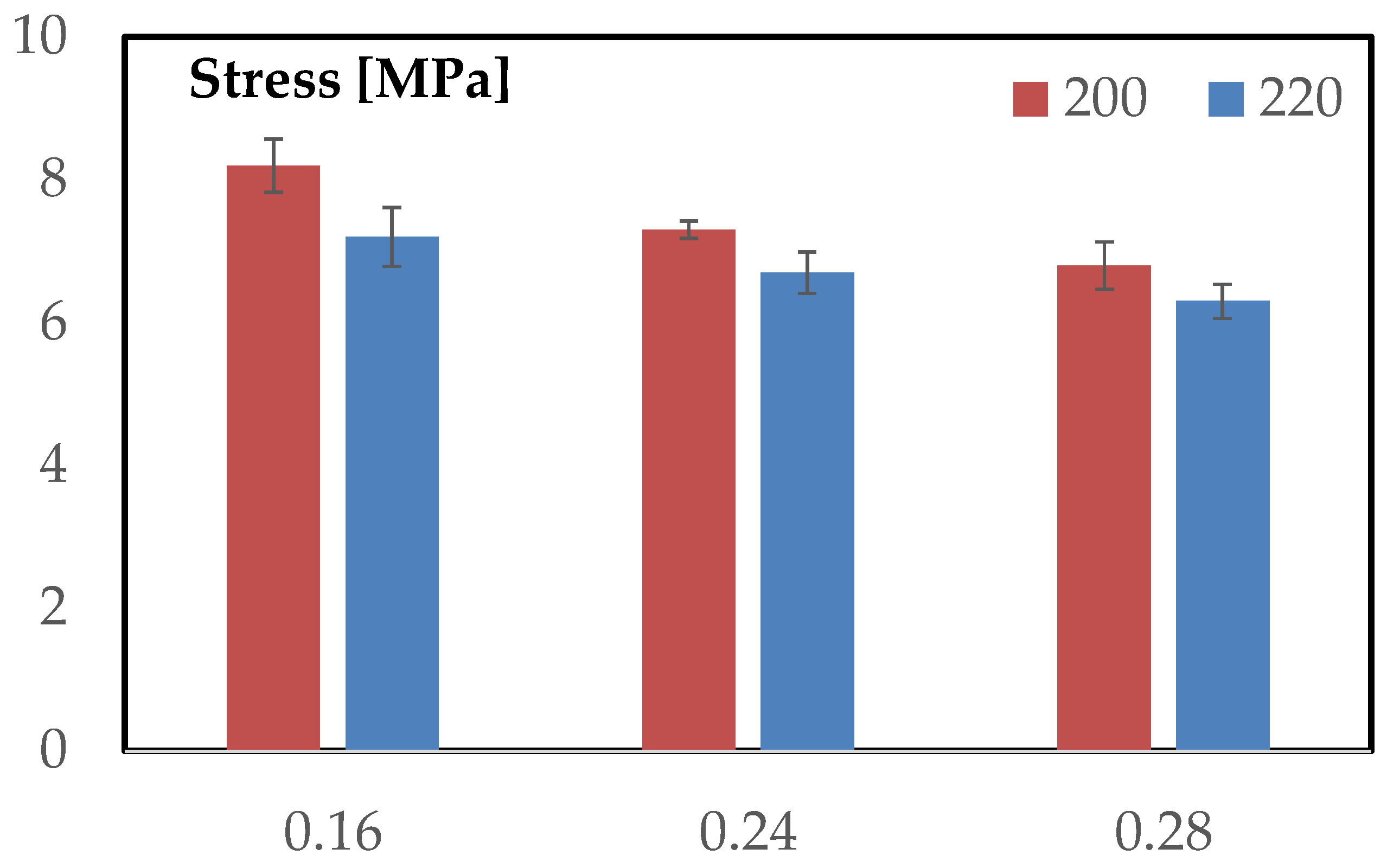

Figure 3a summarizes the maximum flexural stresses for each layer height at both temperatures, with error bars showing one standard deviation. At 200 °C, the ranking is monotonic with layer height: 0.28 mm = 23.2 ± 0.21 MPa (highest), while 0.16 mm = 19.3 ± 0.47 MPa and 0.24 mm = 19.3 ± 0.25 MPa are coincident within the scatter. At 220 °C, the pattern becomes bimodal: 0.16 mm = 22.2 ± 0.61 MPa and 0.28 mm = 22.2 ± 0.36 MPa share the highest value, whereas 0.24 mm = 19.0 ± 0.29 MPa remains distinctly lower. Comparing temperatures at fixed geometry, increasing T from 200 to 220 °C raises the peak for 0.16 mm by +2.9 MPa (+15.0%), leaves 0.24 mm essentially unchanged (−0.3 MPa; −1.6%), and slightly reduces 0.28 mm (−1.0 MPa; −4.3%).

It is important to note that the slight reduction in flexural strength observed at 220 °C is not related to any thermal degradation of the flax fibers. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) of the same PLA–flax filament, as reported by Calabrese et al. [

29], showed no measurable mass loss below 230–240 °C, confirming the thermal stability of both the PLA matrix and the flax reinforcement within the investigated temperature range. Therefore, the performance variation at 220 °C is attributed to process-related factors such as local over-melting, reduced dimensional stability, and minor geometric distortion of the TPMS walls rather than to fiber degradation.

Dispersion is uniformly small (coefficients of variation: 0.9–2.7%), supporting the robustness of these trends. Operationally, coarse discretization (0.28 mm) maximizes strength at 200 °C and remains high at 220 °C; fine discretization (0.16 mm) benefits markedly from the higher temperature; the intermediate setting (0.24 mm) underperforms at both temperatures.

Figure 3b reports the strain at maximum load for all conditions, with error bars representing one standard deviation. At 200 °C, the mean strain decreases from 0.060 ± 0.006 (0.16 mm) to 0.050 ± 0.007 (0.24 mm) and 0.050 ± 0.0054 (0.28 mm), indicating that coarser vertical discretization shortens the deformation capacity at the peak.

At 220 °C, the values more tightly clustered—0.040 ± 0.0007 (0.16 mm), 0.050 ± 0.005 (0.24 mm), and 0.040 ± 0.0008 (0.28 mm)—so the 0.16 mm and 0.28 mm settings converge to approximately 0.04, while 0.24 mm remains around 0.05. Comparing temperatures at fixed geometry, increasing T from 200 to 220 °C reduces the peak strain significantly for 0.16 mm (−0.020, −33%) and 0.28 mm (−0.010, −20%), whereas 0.24 mm is essentially unchanged (Δ ≈ 0.00). Variability analysis confirms the trend: coefficients of variation at 200 °C are about 10% (0.16 mm), 14% (0.24 mm), and 11% (0.28 mm), while at 220 °C they drop to 1.8–2.0% for 0.16 mm and 0.28 mm and remain, about 10% for 0.24 mm. In practical terms, the higher temperature compresses the strain-at-peak for the fine and coarse layer heights, yielding tighter, more repeatable maxima, whereas the intermediate 0.24 mm condition preserves a higher peak strain but with comparatively larger scatter.

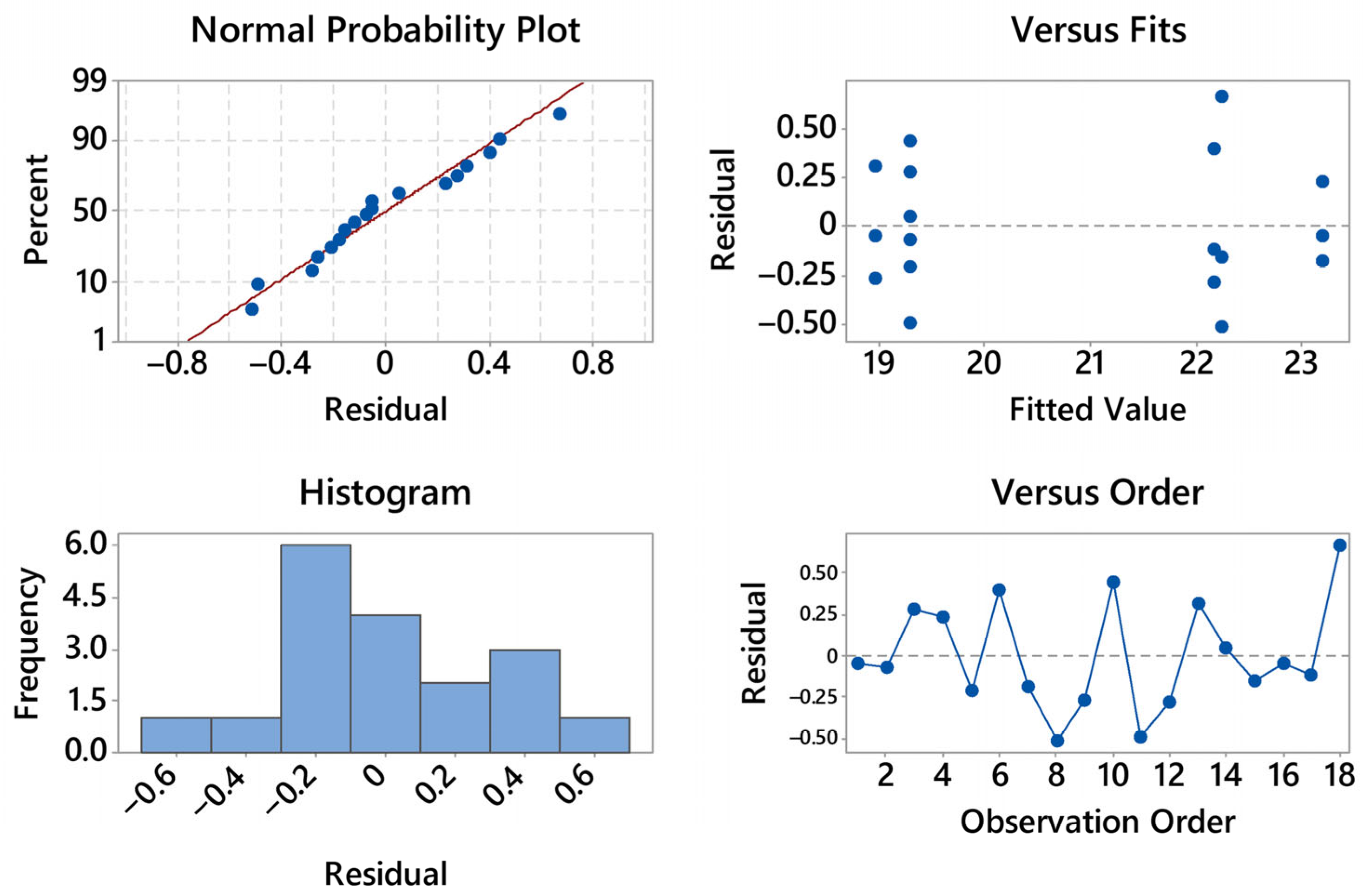

To assess whether temperature (T), layer height (h), and their interaction (T × h) have statistically significant effects on the flexural metrics, a two-way ANOVA is considered. The response variables are the maximum stress and the strain at maximum load; factors are fixed with two levels for T (200, 220 °C) and three levels for h (0.16, 0.24, 0.28 mm). The analysis follows the usual workflow: verification of model assumptions (approximate normality of residuals and homoscedasticity), computation of F-ratios for the two main effects and the interaction at α = 0.05, and reporting of effect sizes (e.g., η2 or partial η2). The forthcoming ANOVA plots (means with confidence intervals, interaction plots, residual diagnostics) are interpreted within this framework to determine which process variable(s) drive the observed differences and how robust those differences are.

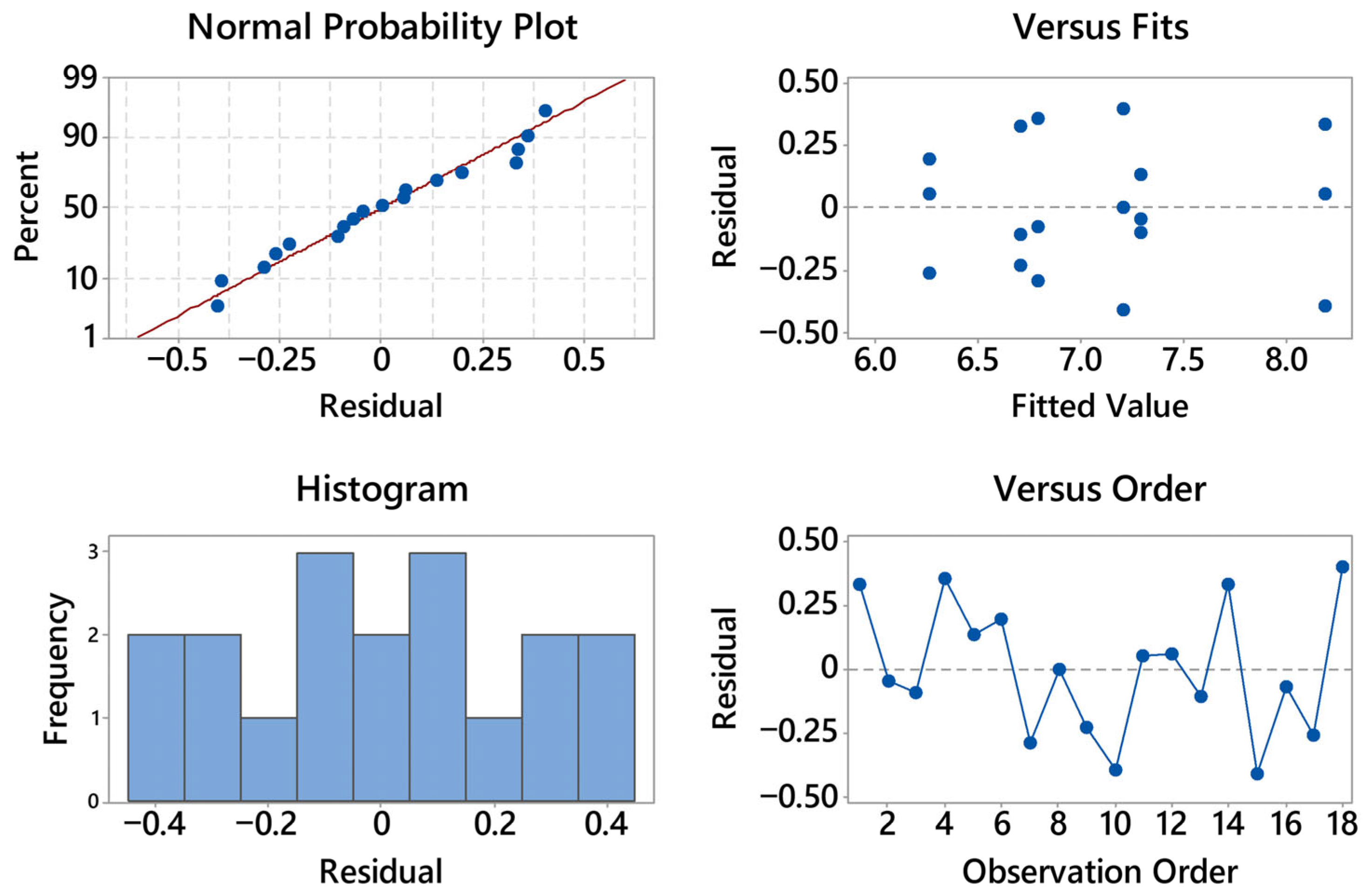

The residual diagnostics for stress are satisfactory (see

Figure 4). The normal probability plot is close to linear with only mild deviations at the extremes, suggesting at most a slight light-tailed behavior; no pronounced outliers are evident. The histogram is roughly symmetric and centered near zero, again consistent with approximate normality. In the residuals vs. fits panel there is no curvature or funneling—residual spread remains essentially constant from nearly 19 to 23 MPa—so heteroscedasticity is not indicated; the visible vertical clusters simply reflect the discrete treatment means. The residuals vs. order plot shows an alternating, patternless scatter around zero with no drift over time; the last positive residual (about +0.6) is isolated but not influential. Overall, the ANOVA assumptions of normality, homoscedasticity, and independence appear reasonable, and no transformation is warranted for the stress response.

The ANOVA for stress, reported in

Table 5, indicates excellent model fit (R

2 = 96.66%, R

2(adj) = 95.26%, R

2(pred) = 92.48%; residual SD S = 0.390 MPa). Both temperature (T) and layer height (h) are statistically significant, as is their interaction T × h. Layer height is the dominant contributor (F = 124.75,

p < 0.001; Adj SS = 38.002 MPa

2, ≈69.5% of total variance), while temperature has a smaller but still significant effect (F = 8.24,

p = 0.014; Adj SS = 1.255 MPa

2, ≈2.3%). The interaction is large and highly significant (F = 44.59,

p < 0.001; Adj SS = 13.583 MPa

2, ≈24.8%), confirming that the influence of T depends on the chosen layer height and vice versa. The small error term (Adj MS = 0.152 MPa

2) relative to the treatment mean squares supports good repeatability and the robustness of the detected effects. In practical terms, h drives most of the strength variation, but because T × h is sizable, strength rankings change with temperature (e.g., the advantage of coarse layers at 200 °C and the bimodal 0.16/0.28 top values at 220 °C), so factor settings must be selected jointly rather than optimized in isolation.

The significant T × h interaction can be explained by the thermal history and diffusion dynamics at the layer–layer interface. At the smallest layer height (0.16 mm), the greater number of interfaces per unit thickness and the shorter time between neighboring passes favor heat accumulation and delay cooling of the previously deposited filament. Under these conditions, increasing the extrusion temperature to 220 °C lowers the melt viscosity of the PLA–flax composite and increases chain mobility, enhancing interlayer wetting and polymer interdiffusion at the interface and reducing voids. The resulting improvement in interlaminar bonding leads directly to the marked increase in flexural strength observed for 0.16 mm at 220 °C. In contrast, for the thickest layers (0.28 mm), the larger bead cross-section and the longer thermal path to the part interior promote a steeper temperature drop between successive layers; the outer region of each filament solidifies more rapidly, and the interface temperature at the moment of deposition is closer to, or below, the optimal healing window. In this regime, the benefit of a higher nozzle temperature is limited by insufficient time above the glass-transition temperature, so polymer reptation across the interface is constrained and the strength gain is small.

This behavior is in line with process–structure studies on PLA-based material extrusion, which show that interlayer adhesion depends on the combined effects of nozzle temperature, layer thickness, and interlayer time through their impact on interface thermal history and diffusion-driven healing, rather than on nozzle temperature alone [

44,

48]. It is also consistent with recent analyses of temperature-sensitive parameters and interfacial bonding in FFF parts, which highlight diminishing returns when available diffusion time is limited, even at elevated extrusion temperatures [

49,

50].

The residual diagnostics for strain at maximum load are fully acceptable (see

Figure 5). The normal probability plot is nearly linear with only minor deviations in the lower tail, indicating approximate normality and no outliers of concern.

The histogram is narrow and centered close to zero, consistent with a small residual variance. In the residuals vs. fits panel there is no curvature or funneling across the fitted range (~0.041–0.061), so homoscedasticity holds; the vertical groupings reflect the discrete treatment means rather than a modeling issue. The residuals vs. order plot shows an alternating scatter around zero without drift or cycles, supporting independence over the acquisition sequence. Overall, the assumptions for ANOVA (normality, constant variance, independence) appear well satisfied for the strain response; no transformation is warranted.

The ANOVA for strain at maximum stress, reported in

Table 6, shows a moderate model fit (R

2 = 76.39%, R

2(adj) = 66.55%, R

2(pred) = 46.87%; residual SD S = 0.00484). The dominant factor is temperature (F = 27.18,

p < 0.001; Adj SS = 0.000636), accounting for ~53% of the total variability in strain. Layer height alone is not significant at α = 0.05 (F = 1.13,

p = 0.355; Adj SS = 0.000053, ~4% of total), but the T × h interaction is significant (F = 4.69,

p = 0.031; Adj SS = 0.000219, ~18% of total), indicating that the effect of layer height depends on temperature. This is consistent with the sample means: at 200 °C strain decreases from 0.16 to 0.24/0.28, whereas at 220 °C, the 0.16 and 0.28 levels converge to approximately 0.04, while 0.24 remains around 0.05. The relatively lower R

2(pred) suggests some unexplained dispersion (expected for a deformation metric measured at the peak), but the inference is clear: ductility at peak is governed primarily by temperature, with layer height exerting a secondary, temperature-dependent influence. Therefore, control of strain capacity should prioritize temperature setting, with layer height adjusted conditionally.

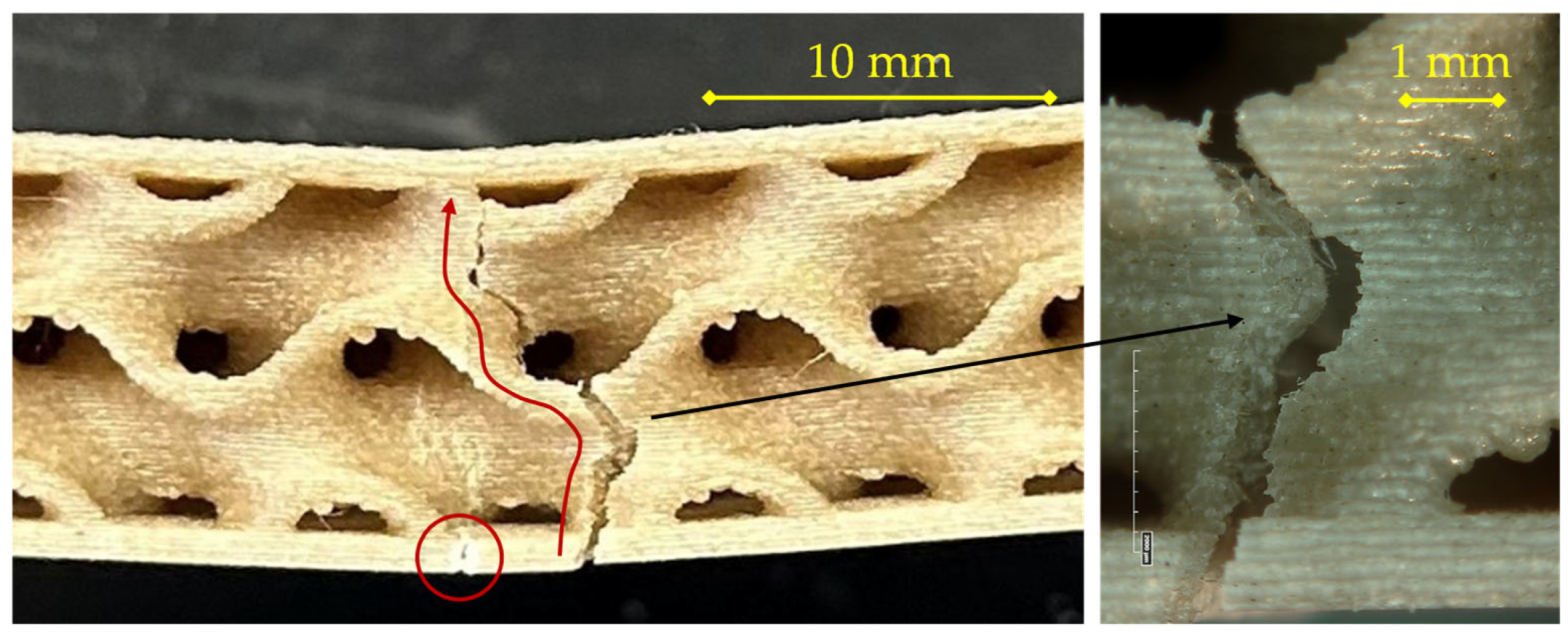

For the specimen printed at 200 °C with a 0.16 mm layer height, as observed in

Figure 6, the fracture sequence initiates at the tensile skin (bottom layer) and propagates upward through the core, showing a typical bending-induced failure pattern.

At the early stage of loading, small surface defects and printing-induced voids in the outer skin act as stress concentrators. A primary crack nucleates at mid-span in the lower skin (central circled region) and propagates along the raster direction of the deposited filaments. As deformation increases, the crack progressively opens, causing local separation of the bottom skin and limited delamination at the core–skin interface, as evidenced by the secondary circled cracks on either side. The fracture then turns upward into the gyroid wall, following a tortuous path governed by stress redistribution within the core.

The magnified view reveals the detailed morphology of the fracture path: a sequence of brittle rupture zones alternating with ductile tearing segments, typical of FFF-printed PLA composites with partial interlayer fusion. The microstructural roughness and fibrillation observed inside the crack suggest that failure occurred mainly by inter-layer decohesion rather than by intra-layer rupture. This indicates a limited degree of polymer diffusion between successive layers at 200 °C, consistent with the lower deposition temperature leading to incomplete molecular interpenetration. The presence of small voids and unbonded regions at the filament boundaries further confirms that interfacial adhesion, both between deposited lines and between the core and the skin, plays a dominant role in crack propagation under flexural stress.

Overall, the observed mechanism corresponds to a progressive and non-catastrophic failure, characterized by sequential opening of the lower skin, partial delamination of the interface, and gradual advance of the fracture front toward the upper layers of the core, in line with the behavior described for the PLA–flax sandwich structures in the reference study [

29].

For the 200 °C/0.24 mm configuration shown in

Figure 7, the fracture pattern remains consistent with tensile-skin-initiated failure, but the damage is more extensive and structurally integrated with the core than in the 0.16 mm case.

The sequence begins with crack nucleation at mid-span in the lower skin, where tensile stresses are maximal. The fracture initiates along a single filament track and then spreads laterally following the raster orientation. The detachment front advances along the skin–core interface, creating a partial delamination zone, as indicated by the secondary circled cracks on both sides of the midline. As opening increases, the primary circled crack kinks upward into the first gyroid wall, where stress redistribution within the core drives a tortuous propagation path (see right-hand detail).

The two detailed views show complementary aspects of this mechanism.

On the left, the surface morphology displays a stepped pattern associated with interlayer decohesion, typical of limited polymer diffusion at 200 °C. The presence of smooth facets alternating with micro-bridged ligaments suggests a mixed adhesive–cohesive failure, where partial bonding resisted before final rupture.

On the right, the crack tip exhibits evidence of progressive tearing and filament pull-out, indicating that the damage evolved gradually rather than catastrophically. This corresponds to the observed load–displacement behavior, in which stress decreases smoothly after the maximum load.

Compared with the 0.16 mm specimen, the 0.24 mm layer height leads to slightly larger delaminated regions and a more tortuous crack path through the interface, consistent with modestly improved interlayer fusion but still limited adhesion at this deposition temperature. The failure remains dominated by tensile rupture of the lower skin followed by localized delamination and upward crack propagation through the gyroid walls, confirming a progressive, non-brittle fracture mode typical of PLA sandwiches fabricated at 200 °C.

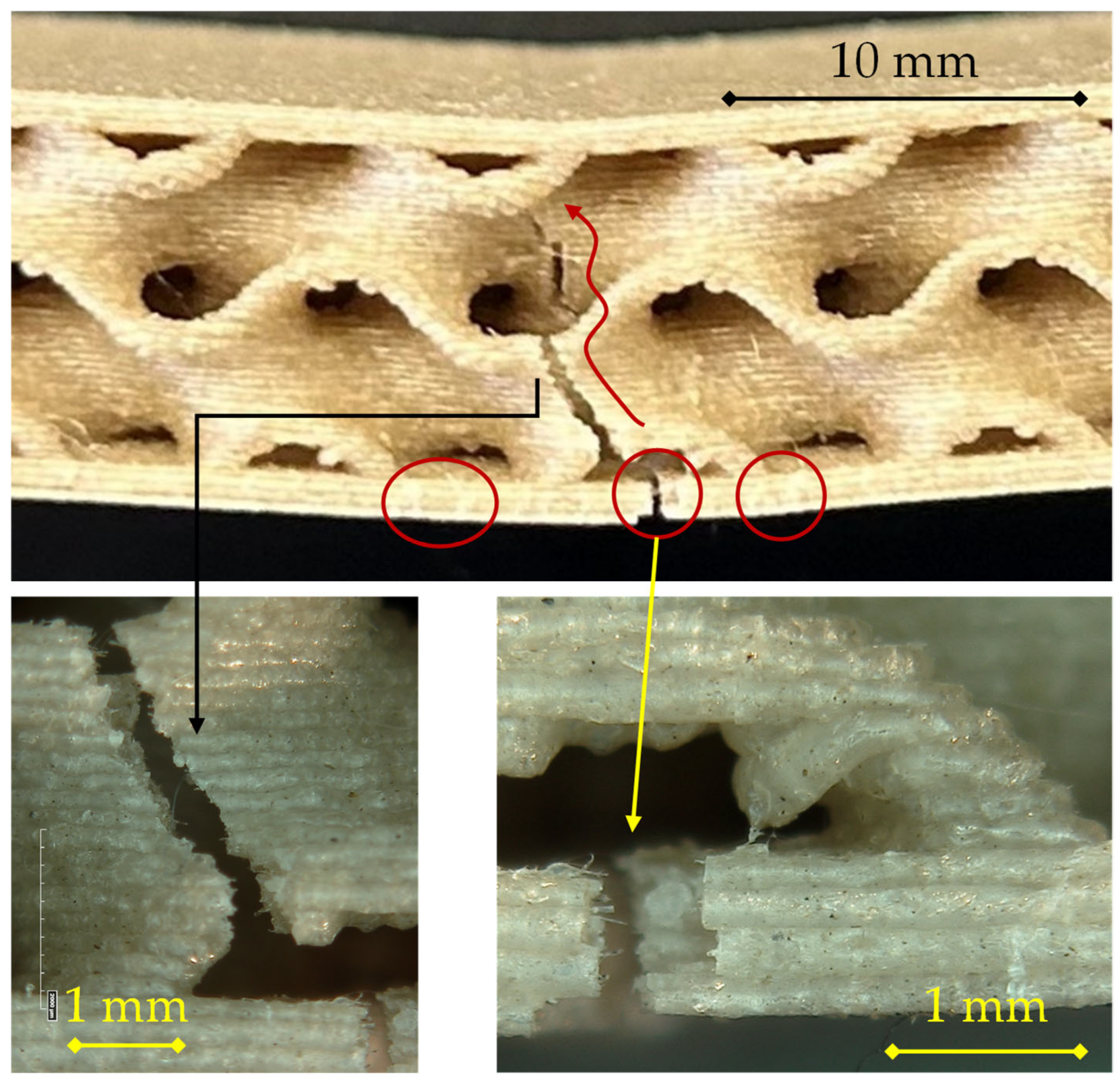

For the 200 °C/0.28 mm configuration, reported in

Figure 8, the fracture mode maintains the general pattern observed at lower layer heights but reveals more cohesive and localized failure in the tensile skin, along with reduced interfacial delamination.

In the main view, a primary crack nucleates at mid-span in the lower skin (central circled region) and remains relatively confined. The fracture front then propagates upward through the gyroid wall along a single, well-defined path (see right-hand detail). The absence of extended delamination at the skin–core interface, apart from the small secondary circled cracks, indicates stronger interlayer bonding, likely due to the reduced number of interfaces per unit thickness and the higher thermal retention of the thicker extruded lines, which enhances filament–filament fusion.

The microscopic details (bottom images) provide further evidence of this enhanced bonding.

On the left, the lower skin fracture surface exhibits a rough, fibrous morphology, indicating cohesive failure within the extruded filaments rather than interlayer separation. The limited presence of planar decohesion planes contrasts with the more layered appearance observed in the 0.16 mm and 0.24 mm specimens.

On the right, the propagation front within the core shows a narrow, continuous tear through successive gyroid walls, confirming that load transfer remained effective between the core and the skin up to the point of rupture.

The inset (top left) highlights a partial detachment occurring adjacent to the crack path, possibly related to local stress redistribution after skin rupture, but it does not evolve into extended delamination.

Overall, the fracture morphology of this sample supports a more integrated structural response, with higher load-bearing capability before failure and less progressive damage evolution than thinner-layer counterparts. The failure is still driven by tensile rupture of the bottom skin, but the increased layer thickness contributes to a more cohesive, stronger bond network, which delays crack propagation and explains the higher maximum load recorded for this configuration compared to 0.16 and 0.24 mm.

For the 220 °C/0.16 mm configuration, reported in

Figure 9, the fracture exhibits a distinctly more cohesive and concentrated failure mode, consistent with the improved interlayer adhesion expected at the higher deposition temperature.

As shown, the crack initiates at mid-span in the lower skin (circled region), where bending tensile stresses are highest. The separation front is narrow and well confined, unlike the broader damage observed at 200 °C. After initiation, the primary crack kinks upward into the core (curved red arrow), following a straighter, more continuous path that indicates homogeneous stress transfer across the skin–core interface and limited interfacial delamination.

The magnified view confirms this behavior: the fracture front appears compact and sharply defined, with limited signs of interlayer decohesion. The tearing pattern is dominated by cohesive rupture of the extruded filaments, indicating effective molecular interdiffusion between adjacent layers due to the higher temperature. The smoother transition between the fractured skin and the adjacent gyroid walls reveals that debonding at the interface is minimal, and the damage evolves primarily through the core structure.

Overall, the fracture morphology at 220 °C and 0.16 mm indicates that increasing the temperature enhances interlayer bonding, reduces premature delamination, and results in a more localized and cleaner crack path. This behavior is consistent with a higher strain at failure and a more stable post-peak response, reflecting the improved adhesion between the skin and core and the stronger cohesive integrity of the printed structure.

For the 220 °C/0.24 mm configuration, reported in

Figure 10, the fracture sequence maintains the typical pattern of tensile-skin initiation but shows a more complex and energy-dissipative crack evolution compared with the thinner-layer case, suggesting a balanced interaction between enhanced interlayer bonding and localized interfacial debonding.

Failure initiates at mid-span in the lower skin (primary circled crack). The microcrack follows the filament tracks and opens in a controlled manner. A shallow delamination develops at the skin–core interface, evidenced by the secondary circled cracks adjacent to the midline. The fracture then kinks upward into the first gyroid wall, remaining localized; the close-ups show limited interfacial separation with small bridging ligaments, consistent with improved interlayer bonding at 220 °C.

The magnified views provide further insight into the fracture mechanisms.

On the left, the rupture path exhibits alternating brittle and ductile features, with small unbroken filaments bridging the two fracture surfaces—evidence of partial filament coalescence and controlled energy dissipation.

On the right, the cross-sectional morphology highlights the tight contact between skin and core, with limited interfacial voids and no extended detachment, confirming effective stress transfer during bending.

Overall, the fracture mode at 220 °C and 0.24 mm layer height reflects a hybrid mechanism in which tensile cracking of the skin remains the governing factor, but the higher deposition temperature enhances molecular diffusion and fusion between printed layers, resulting in a more cohesive fracture surface and a smoother post-peak load decay. The damage evolves in a progressive yet more localized manner, in line with the improved mechanical stability observed in the corresponding flexural response.

For the 220 °C/0.28 mm configuration, reported in

Figure 11, the fracture exhibits the most cohesive and structurally integrated failure mode among all the tested conditions, highlighting the beneficial combined effect of higher deposition temperature and larger layer thickness on interlayer adhesion and overall structural integrity.

In the main view, a primary crack nucleates at mid-span in the lower skin (central circled region) and follows the filament tracks before kinking upward into the gyroid wall (curved red arrow). The crack path is compact and centrally confined, indicating a highly localized stress field. No extended delamination is visible at the skin–core interface; only small secondary circled cracks appear adjacent to the initiation site. This morphology confirms strong skin–core bonding at 220 °C and the cohesive nature of failure for the 0.28 mm layer.

The microscopic details provide additional evidence of this cohesive fracture mode:

On the left, the rupture surfaces display fused, plastically deformed filaments with limited interlayer separation, suggesting that failure occurred mainly by cohesive tearing rather than interfacial decohesion. The rough, fibrous texture reveals strong interdiffusion and thermal bonding between adjacent layers.

On the right, the crack front through the gyroid wall shows a continuous rupture path that cleanly connects the core and the skin, with no evidence of void formation or debonding. The core remains structurally intact except for the localized fracture zone, confirming its efficient load-transfer role during bending.

Overall, the 220 °C/0.28 mm sample demonstrates a highly cohesive and energy-absorbing fracture behavior, characterized by localized tensile rupture of the bottom skin followed by stable crack propagation through the gyroid wall. Enhanced thermal fusion between deposited filaments leads to a strong skin–core adhesion and suppresses interfacial delamination. This morphology is consistent with the highest maximum load recorded among the tested conditions, reflecting improved mechanical performance and failure stability associated with this optimized processing configuration.

3.3. Compression Behavior

The compressive response of the TPMS-sandwich specimens is examined through representative stress–strain curves obtained under quasi-static loading according to ASTM C365.

Figure 12a,b report the families of curves for the two extrusion temperatures, while the subsequent discussion focuses on the characteristic regions of the curves and on how layer height modulates stiffness, first-collapse stress, and post-collapse evolution.

All compressive stress–strain curves exhibit a characteristic multi-stage response typical of architected cellular solids:

Elastic region: At small strains, the response is linear and governed by the global stiffness of the gyroid core. All configurations show nearly identical initial slopes, indicating comparable elastic moduli.

Onset of collapse (first collapse): A well-defined peak marks the buckling or instability of the gyroid walls. This first-collapse stress represents the true strength of the cellular core in compression and is strongly affected by printing parameters.

Progressive densification (post-collapse softening or plateau-like region): Immediately after the peak, the stress either slightly drops or remains almost flat as the collapse band spreads through the structure. In this stage, the gyroid walls fold, bend, and progressively close the internal voids. Unlike classical foams, the gyroid does not form a long plateau; instead, it exhibits a short densification region where deformation localizes and the structure becomes increasingly compact.

Final compaction (sharp stress rise): Once the voids are almost fully closed and the collapsed walls have packed together, the structure behaves as a quasi-solid. At this point, the stress increases steeply, producing the pronounced upward turn visible in all curves at large strains (ε ≈ 0.45–0.55). This final rise marks the transition from geometrically governed collapse to the intrinsic compressive stiffness of the compacted material.

Overall, the curves reflect the smooth, continuous morphology of the gyroid: failure proceeds through stable folding and densification rather than sudden, brittle crushing, and the transition into the compaction regime occurs earlier than in conventional open-cell lattices due to the absence of thin struts and the presence of continuous curved walls.

At 200 °C, the three stress–strain curves share the same overall shape, but their relative position reveals clear differences in structural stability. The curve corresponding to the smallest layer height consistently lies above the others, indicating a more resistant and stable core during both the collapse and densification stages. As layer height increases, the curves shift progressively downward, signaling less stable wall buckling and a reduced ability to sustain load after the first collapse.

Despite this hierarchy, the general sequence of elastic rise, collapse, short densification, and final compaction remains the same for all configurations; what changes is the height of the curves, not their shape. The finest layer height produces the stiffest and most stable response, whereas the coarsest layer height exhibits an earlier drop in stress and a slightly smoother transition into compaction.

At 220 °C, the curves maintain the same relative ordering observed at 200 °C: the finest layer height again yields the uppermost curve, while the coarsest height produces the lowest one. However, the entire family of curves shifts downward compared to their 200 °C counterparts, revealing a moderate reduction in collapse resistance associated with the higher extrusion temperature.

The softening region following collapse is slightly smoother at 220 °C, suggesting more homogeneous filament fusion and fewer local imperfections in the TPMS walls. Nonetheless, the characteristic sequence of stages remains unchanged, and the distinction between layer heights is still apparent, even though the differences are somewhat less pronounced than at the lower temperature.

Comparing temperatures at a fixed layer height shows a consistent effect: the 220 °C curves lie below the 200 °C ones across the entire deformation range. This downward shift is evident immediately after the elastic region and becomes particularly clear at the onset of collapse. While the qualitative shape of the curves remains identical at the two temperatures, the higher extrusion temperature leads to slightly less stable walls and an earlier transition from collapse to densification.

Importantly, this temperature effect does not modify the ordering imposed by layer height: at both 200 °C and 220 °C, finer layers provide the most stable compressive response, and coarser layers the least. Temperature acts as a vertical offset, uniformly lowering all curves, whereas layer height governs their relative elevation.

The qualitative comparison of the compression curves shows that layer height exerts the dominant influence on the structural stability of the TPMS core. Finer layers generate more uniform walls, with fewer geometric imperfections, and therefore sustain higher stresses during collapse and densification. Coarser layers, by contrast, produce walls with slightly larger waviness and less regular deposition, resulting in lower collapse resistance and a smoother transition into densification. These differences manifest as a clear vertical separation between curves at both temperatures.

Extrusion temperature plays a secondary but systematic role. Increasing the temperature slightly shifts all curves downward, suggesting that higher thermal input smooths or rounds the extruded walls, subtly reducing their ability to resist buckling. Despite this reduction in collapse strength, the overall shape of the curves remains unchanged: the transition from elastic rise to collapse, followed by short densification and final compaction, is consistently preserved for all process conditions. Temperature therefore affects the magnitude of the response but not its mechanism.

Taken together, the compressive behavior reflects the characteristic mode of deformation of gyroid architectures. The absence of discrete struts and the presence of continuous curvature promote stable wall folding and early densification, avoiding catastrophic collapse and ensuring a gradual redistribution of load. The clear influence of layer height, combined with the moderate effect of temperature, indicates that geometric fidelity of the walls, rather than interlayer adhesion, governs compressive performance.

The trends observed in compression complement those previously identified in bending and collectively reveal two distinct process–structure–property regimes within the same TPMS sandwich architecture.

Under bending, the response is skin-dominated. Peak stress and post-peak evolution depend primarily on the continuity, integrity, and bonding of the printed facesheets and on the quality of the skin–core interface. Here, layer height influences the effective cross-section of the outer skins, while extrusion temperature modulates interlayer diffusion and skin consolidation. The result is a complex interaction where the best configuration in bending emerges from a balance between improved skin strength and controlled bonding.

Under compression, by contrast, the response is core-dominated. The load is carried directly by the gyroid walls, and performance depends on their geometric stability and smoothness. Layer height determines the regularity of wall formation, while extrusion temperature acts mostly as a secondary geometric modifier. Interlayer adhesion plays a much smaller role compared to bending, and the ordering of the curves remains the same across temperatures. The collapse mechanism—wall buckling followed by densification—remains stable, predictable, and largely unaffected by skin behavior.

Together, these two regimes highlight the multi-axial nature of process–property relationships in TPMS sandwiches. A printing condition that optimizes bending strength does not necessarily maximize compression resistance, and vice versa. By analyzing both tests, the study provides a broader process window in which temperature and layer height can be tuned according to the functional loading scenario: stiffer skins and strong interfaces for bending, or more uniform walls for compression.

Figure 13 reports the average first-collapse stress for each layer height at the two extrusion temperatures. The qualitative trends observed in the stress–strain curves are fully confirmed here. At both temperatures, the configuration with the finest layer height produces the highest collapse stress, and the values decrease progressively as the layer height increases. This monotonic ordering underlines the central role of vertical discretization in determining the stability of the TPMS walls under axial load.

A second clear trend emerging from the histogram is the effect of extrusion temperature. For every layer height, the bars corresponding to 220 °C lie below those at 200 °C, indicating a uniform reduction in collapse resistance when the extrusion temperature is increased. This downward shift is modest but systematic and mirrors the behavior seen in the curve families: temperature affects the magnitude of the collapse stress but does not alter the ordering imposed by layer height.

The error bars also highlight an important aspect of the compressive behavior. Dispersion remains low and comparable across all configurations, suggesting that the collapse mechanism is highly repeatable and that process-induced variability has a limited influence on the structural stability of the TPMS walls. This is consistent with the smooth, continuous nature of the gyroid geometry, which tends to localize deformation in a predictable manner.

Overall, the histogram reinforces the conclusion that layer height is the dominant parameter governing compression strength, while temperature acts chiefly as a uniform vertical offset, slightly lowering performance but without modifying the underlying mechanical hierarchy established by the geometric discretization.

The residual diagnostics for compressive first-collapse stress are shown in

Figure 14. The normal probability plot is nearly linear, with only minor deviations at the extremes; no outliers or influential points are visible. The histogram is approximately symmetric and centered near zero, indicating reasonably normal residual distribution. In the residuals-versus-fitted plot, no curvature or funneling is observed: the spread of the residuals remains constant across the fitted range, suggesting homoscedasticity. The residuals-versus-order panel shows an alternating scatter without drift or cyclic patterns, supporting independence of the observations. Overall, the assumptions required for ANOVA, normality, constant variance, and independence, are satisfactorily met, and no transformation of the data is needed.

The ANOVA table for first-collapse stress confirms that both extrusion temperature and layer height have statistically significant main effects, whereas their interaction is not statistically significant (see

Table 7). The linear terms collectively explain the vast majority of the variance, and the model achieves a good fit (R

2 ≈ 85%), with acceptable adjusted and predicted R

2 values.

Layer height emerges as the dominant factor, contributing the largest portion of explained variance. This is consistent with the qualitative behavior of the curves, where finer layers consistently provided higher collapse stresses. The significant F-value for layer height reflects the structural sensitivity of the TPMS walls to vertical discretization: smaller layers promote more uniform deposition, reduced geometric irregularities, and more stable buckling behavior.

Temperature also exerts a significant but secondary effect. Its influence is uniform across layer heights: for any given geometry, higher extrusion temperature results in a downward shift of the curve. The significant F-value associated with temperature confirms this systematic reduction in collapse stress, in line with the visual ordering of the histogram. This behavior likely originates from subtle geometric smoothing and reduced dimensional sharpness of the extruded walls at higher thermal input.

In contrast, the interaction term is not statistically significant, indicating that temperature affects all layer heights similarly. This further confirms the trends observed in the stress–strain curves, where temperature acted as a vertical offset rather than modifying the relative ordering established by layer height. The stability and consistency of this response across configurations reinforce the notion that compression is primarily governed by geometric fidelity of the TPMS walls, with interlayer diffusion playing a minimal role.

In summary, the ANOVA reveals a clear, hierarchical influence of process parameters on compressive behavior: layer height is the primary driver of collapse strength, temperature is a secondary but systematic modifier, and no interaction is present, reflecting the inherently core-dominated nature of the compressive response.

The failure morphology observed under compression reflects the progressive and highly stable collapse mechanism characteristic of gyroid TPMS cores. A representative sequence of deformation stages is shown in

Figure 15, illustrating the evolution from the undeformed configuration to post-collapse and finally to densification.

In the undeformed state, the gyroid walls maintain their continuous, smoothly curved geometry, with clearly defined passages and minimal filament irregularities. This morphology explains the consistent elastic response observed across all printing conditions: the structure behaves as a homogeneous cellular solid prior to the onset of buckling.

Immediately after first collapse, the deformation localizes within a horizontal band across the specimen. The walls within this band undergo coordinated buckling and bending, accompanied by local rotations and the formation of flattened regions between adjacent surfaces. Importantly, the collapse remains stable and non-catastrophic: no brittle cracking is observed, nor is there any sudden fragmentation of the TPMS walls. Instead, the structure accommodates deformation through progressive folding, which is consistent with the smooth post-collapse behavior recorded in the stress–strain curves.

As loading continues, the specimen enters the densification stage, where the previously buckled walls begin to contact and pack against each other. The gyroid passages become constricted, and the curved surfaces lose their distinct topology as voids close. This progressive impingement of folded walls marks the transition from geometric collapse to solid-like compaction. The deformation becomes more uniform across the height of the sample, and the stress rises sharply once the remaining porosity is exhausted—precisely matching the steep terminal increase in the mechanical curves.

Across all processing conditions, the failure morphology remains qualitatively identical: compression is governed by wall buckling, folding, and packing, rather than by fracture or interfacial separation. This behavior highlights the inherent stability of gyroid architectures under axial loading and explains why temperature and layer height influence primarily the magnitude of collapse stress while leaving the fundamental mechanism unchanged.