Experimental Investigation of Polymer-Modified Bituminous Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Aggregate

2.2. Bitumen

2.3. Elvaloy RET

2.4. Polyphosphoric Acid (PPA)

2.5. Cellulose Fiber

2.6. Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts

3. Method

3.1. Recycling of Waste Cigarette Butts

3.2. Bitumen Modification

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis of Modified Bitumen

3.4. Bitumen Tests

3.5. SMA Mixture Tests

4. Results

4.1. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis Results of Modified Bitumen

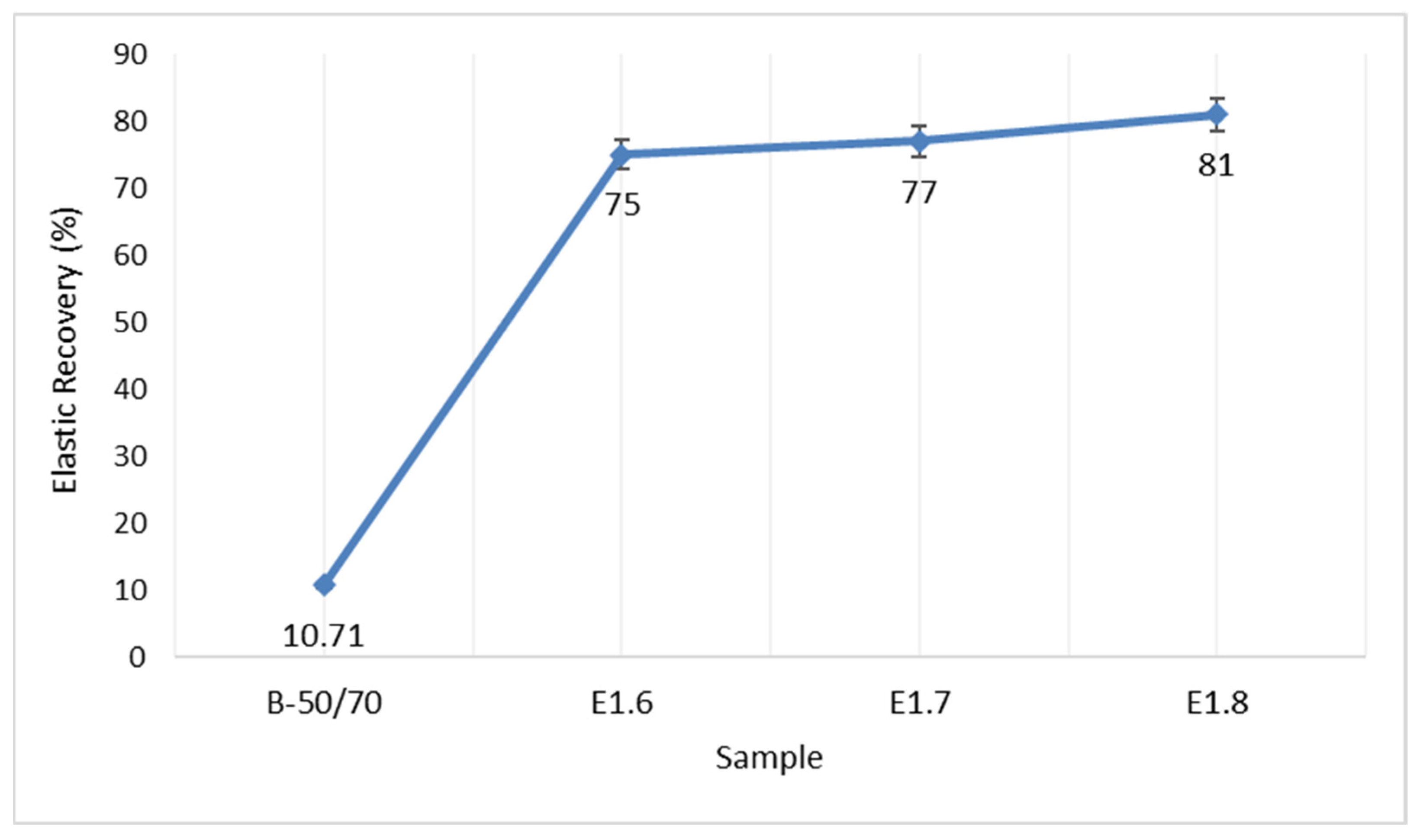

4.2. Bitumen Test Results

4.2.1. Conventional Bitumen Test Results

4.2.2. Results of Mass Loss After RTFOT, Residual Penetration, and Softening Point Tests of Bitumen Samples

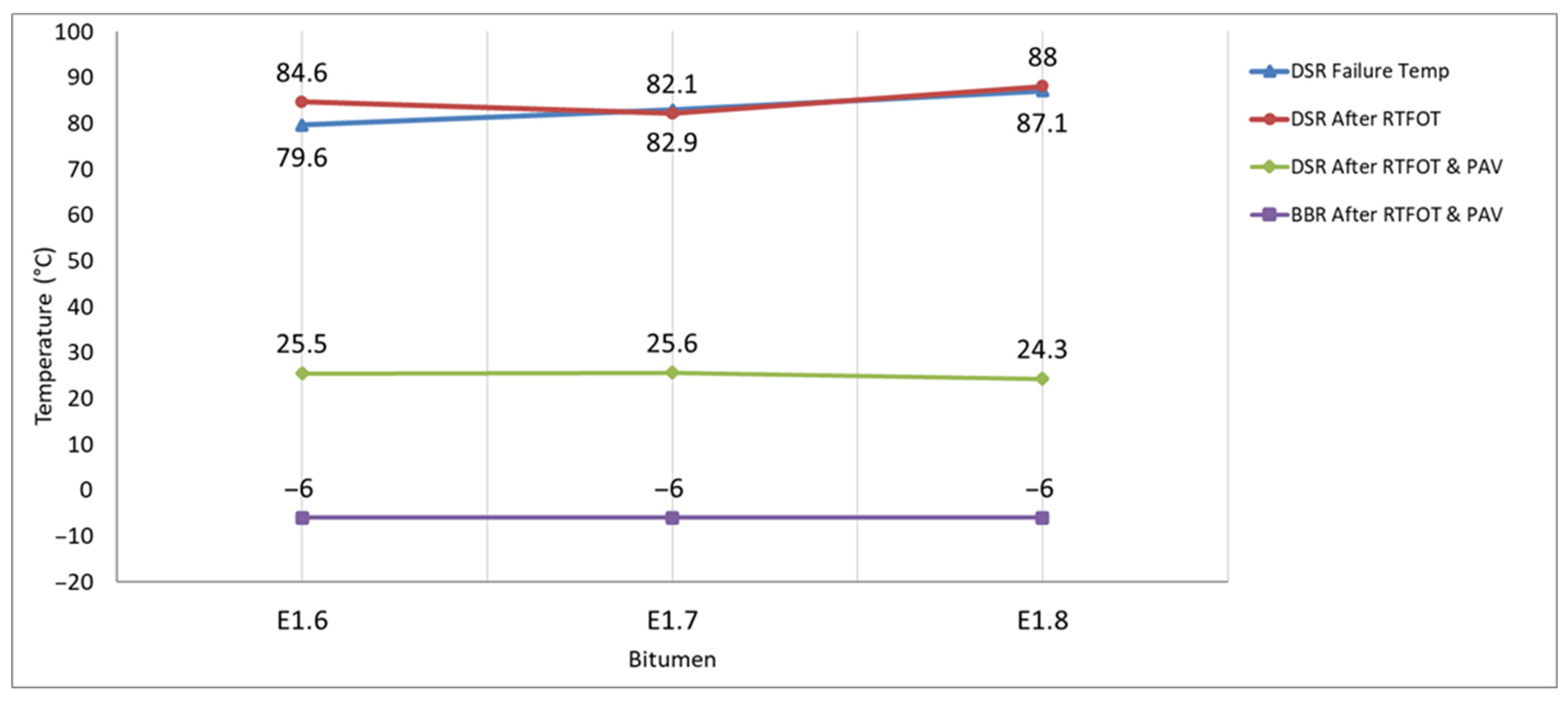

4.2.3. Dynamic Shear Rheometer (DSR) and Bending Beam Rheometer (BBR) Test Results

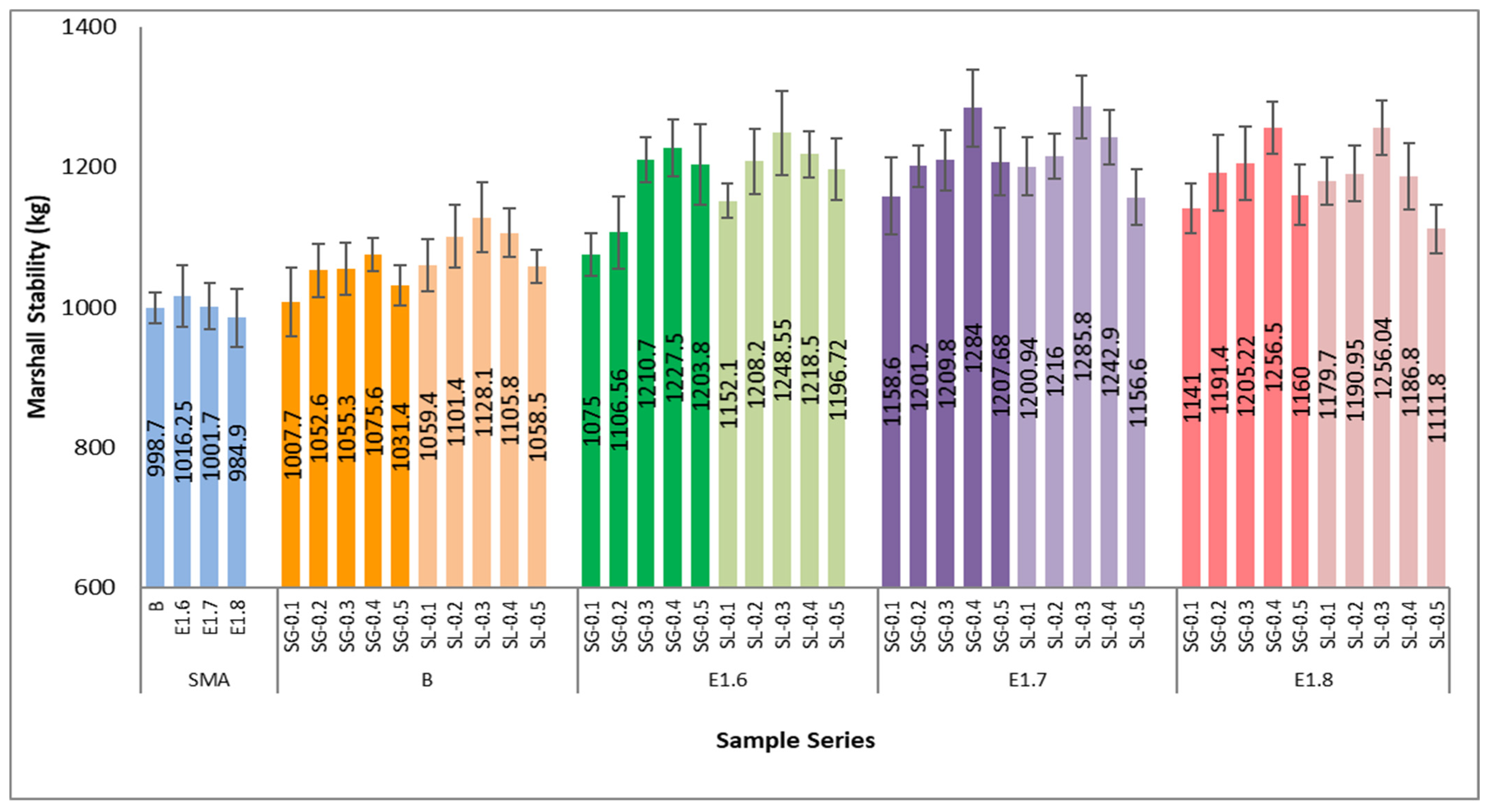

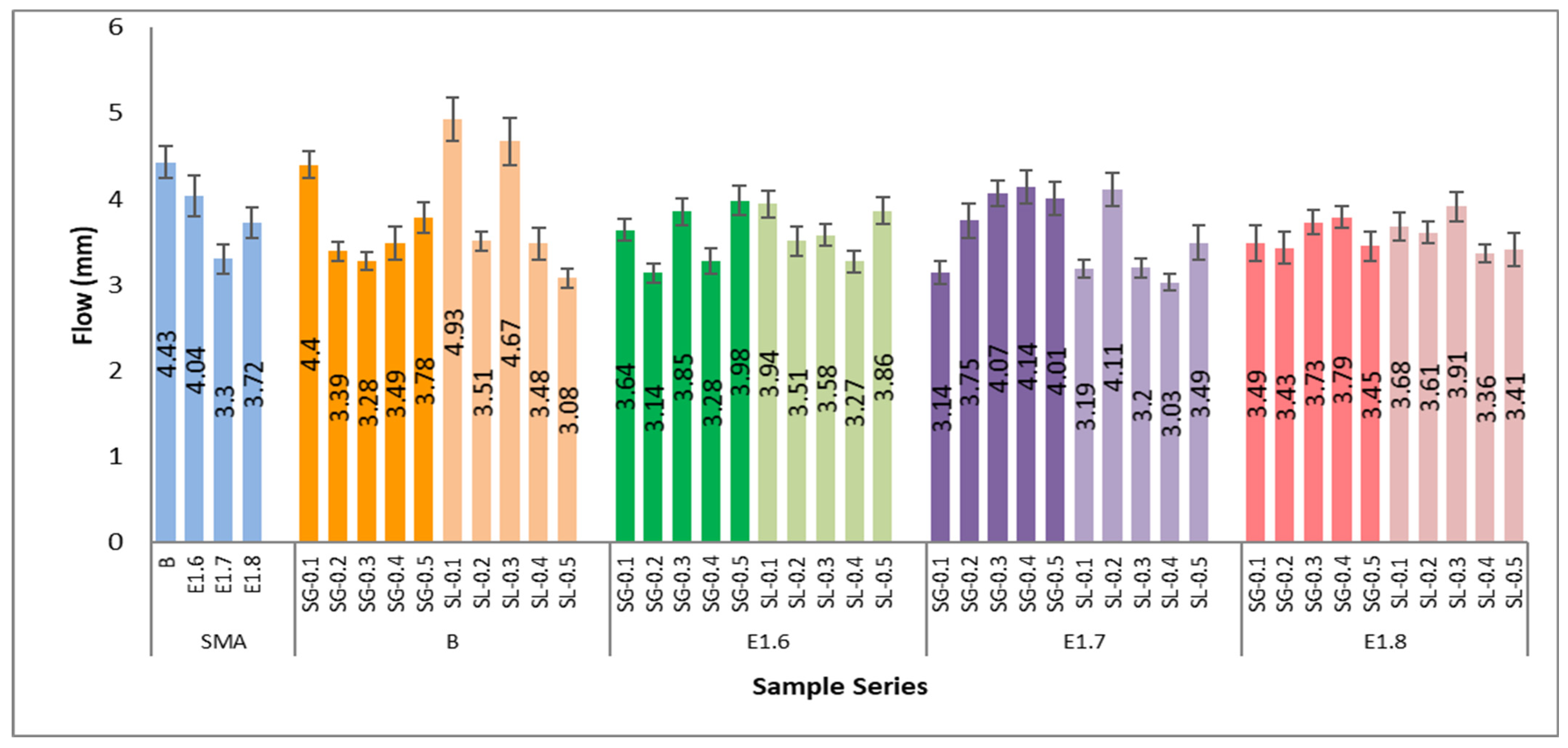

4.3. Mixture Test Results

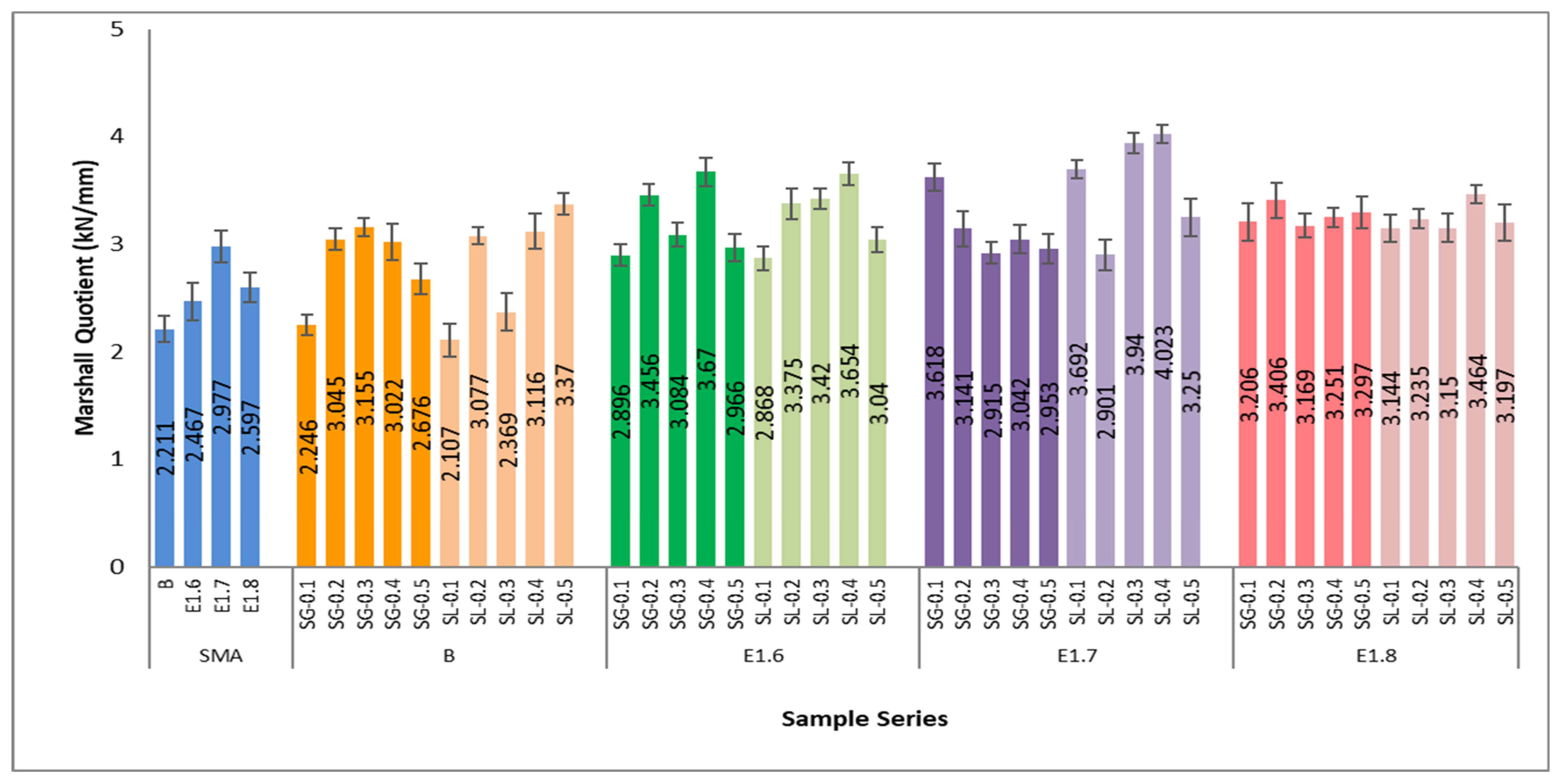

4.3.1. Marshall Stability, Flow and Marshall Quotient Results

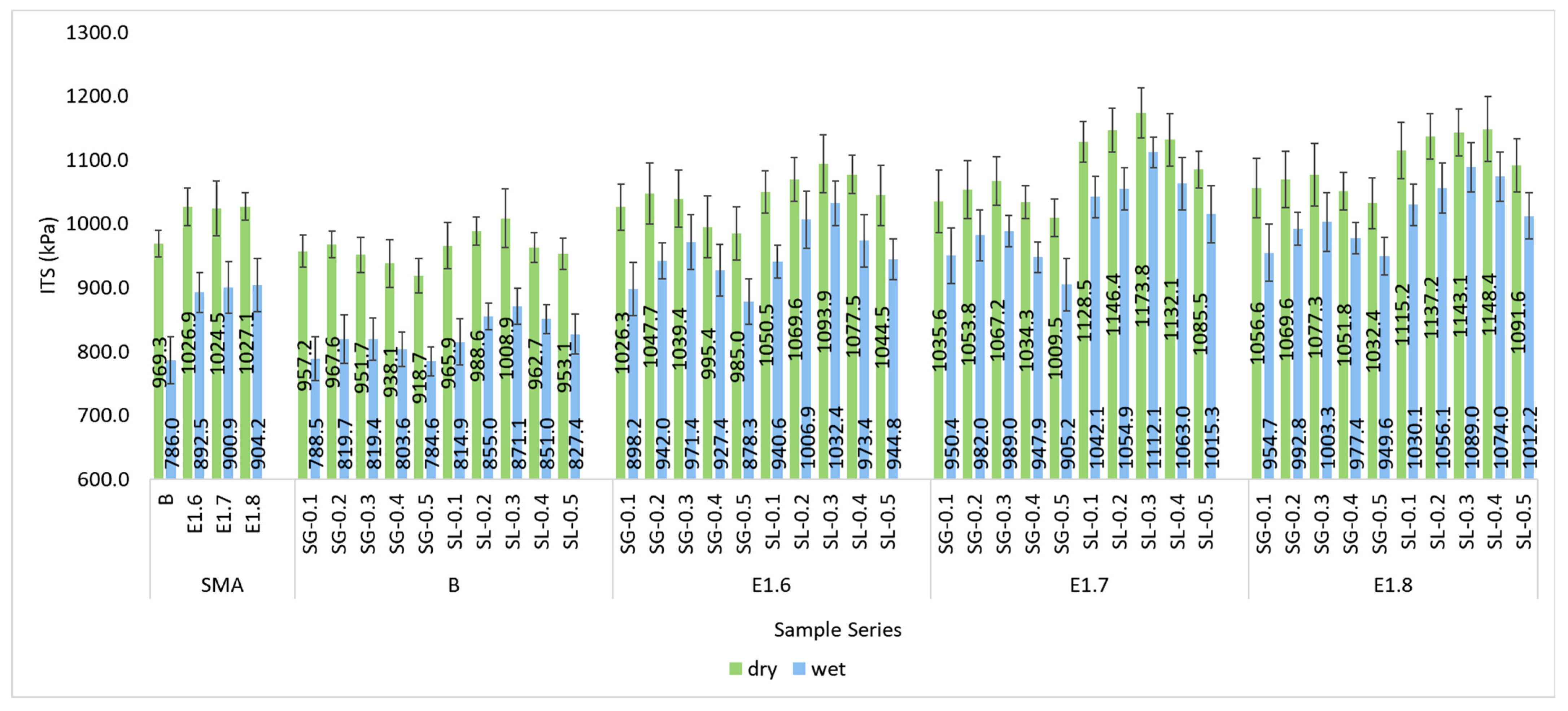

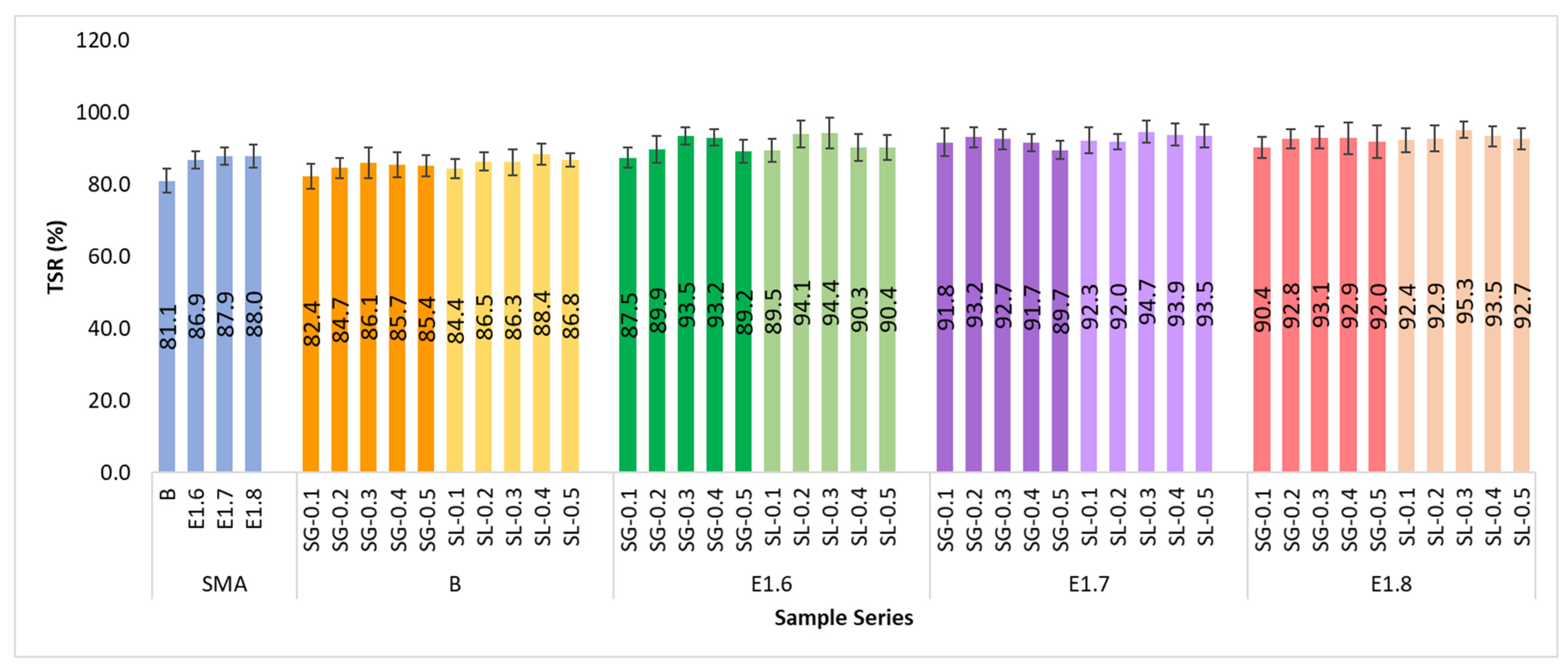

4.3.2. Indirect Tensile Strength and Moisture Damage Resistance Test Results

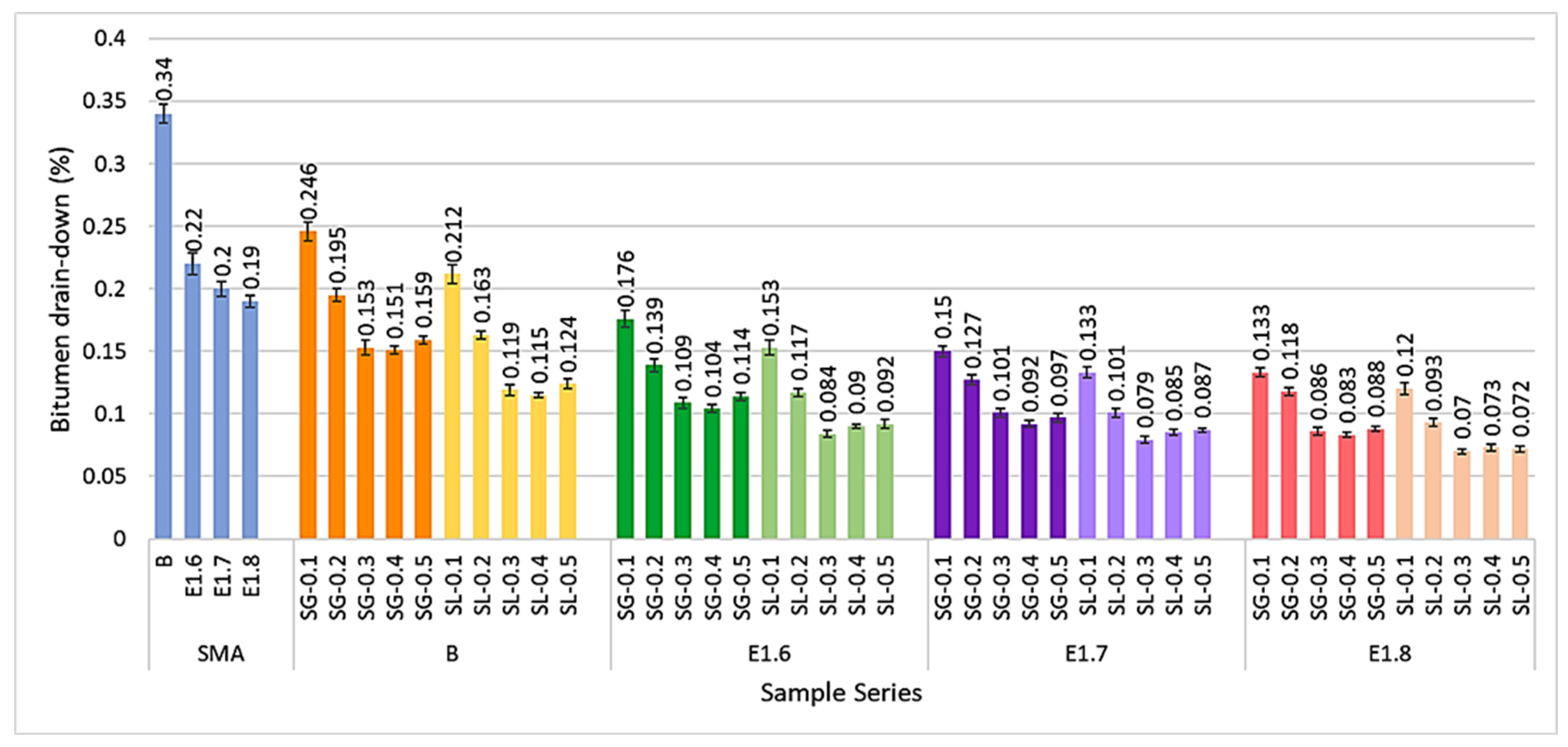

4.3.3. Bitumen Drain-Down Test Results

4.3.4. Sand Patch Test Results

4.3.5. Cantabro Test Results

4.3.6. Cost Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Moghaddam, T.B.; Karim, M.R.; Syammaun, T. Dynamic properties of stone mastic asphalt mixtures containing waste plastic bottles. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 34, 236–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evirgen, B.; Çetin, A.; Karslıoğlu, A.; Tuncan, A. An evaluation of the usability of glass and polypropylene fibers in SMA mixtures. Pamukkale Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2021, 27, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyf, S. Investigation of penetration and penetration index in bitumen modified with SBS and reactive terpolymer. Sigma J. Eng. Nat. Sci. 2010, 28, 26–34. [Google Scholar]

- Seloğlu, M.; Geçkil, T. The effect of reactive terpolymer on the consistency and temperature susceptibility of bitumen. Firat Univ. J. Eng. Sci. 2019, 31, 203–213. [Google Scholar]

- Şengöz, B.; Işıkyakar, G. Evaluation of the properties and microstructure of SBS and EVA polymer modified bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1897–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordi, Z.; Shafabakhsh, G. Evaluating mechanical properties of stone mastic asphalt modified with nano Fe2O3. Constr. Build. Mater. 2017, 134, 530–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshad, A.K.; Shaffie, E.; Hashim, W.; Ismail, F.; Masri, K.A. Evaluation of nanosilica modified stone mastic asphalt. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, M.; Yang, J.; Yao, H.; Wang, M.; Niu, X.; Haddock, J.E. Investigating the performance, chemical, and microstructure properties of carbon nanotube-modified asphalt binder. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2018, 19, 1499–1522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, M.; Saeed, M.; Ahmed, S.; Ali, Y. Performance evaluation of elvaloy as a fuel-resistant polymer in asphaltic concrete airfield pavements. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2017, 29, 04017163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geçkil, T. Physical, chemical, microstructural and rheological properties of reactive terpolymer-modified bitumen. Materials 2019, 12, 921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taciroğlu, M.V. Comparison of elvaloy and styrene-butadiene-styrene added polymer modified bitumen. J. Innov. Transp. 2023, 4, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachhani, K.K.; Mishra, C. Influence of VG30 grade bitumen with and without reactive ethylene terpolymer (Elvaloy® 4170) in short-term aging. Int. J. Curr. Eng. Technol. 2014, 4, 4206–4209. [Google Scholar]

- Inocente Domingos, M.D.; Faxina, A.L. Accelerated short-term ageing effects on the rheological properties of modified bitumens with similar high PG grades. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2015, 16, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasso, M.; Hampl, R.; Vacin, O.; Bakos, D.; Stastna, J.; Zanzotto, L. Rheology of conventional asphalt modified with SBS, Elvaloy and polyphosphoric acid. Fuel Process. Technol. 2015, 140, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedik, A. Utilising cellulose fibre in stone mastic asphalt. Građevinar 2023, 75, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauzi, N.M.; Masri, K.A.; Ramadhansyah, P.J.; Samsudin, M.S.; Ismail, A.; Arshad, A.K.; Hainin, M.R. Volumetric properties and resilient modulus of stone mastic asphalt incorporating cellulose fiber. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020; Volume 712, p. 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, P.; Valentin, J.; Mondschein, P. Asphalt concrete for binder courses with different jute fibre content. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 1203, p. 032041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaffie, E.; Rashid, H.A.; Shiong, F.; Arshad, A.K.; Ahmad, J.; Hashim, W.; Masri, K.A. Performance characterization of stone mastic asphalt using steel fiber. J. Adv. Ind. Technol. Appl. 2021, 2, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, R.; Haldenbilen, S.; Zengin, D. Investigation of usability of mineral fiber in stone mastic asphalt. Rev. Constr. 2023, 22, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Troyano, C.; Llopis-Castelló, D.; Olaso-Cerveró, B. Incorporating recycled textile fibers into stone mastic asphalt. Buildings 2025, 15, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoorob, S.E.; Suparma, L.B. Laboratory design and investigation of the properties of continuously graded asphaltic concrete containing recycled plastics aggregate replacement (Plastiphalt). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2000, 22, 233–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morova, N. Use of waste phonolite as filler material in flexible asphalt pavements. Mater. Sci. 2024, 30, 96–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, W.; Rivera, J.; Sevillano, M.; Torres, T. Performance evaluation of stone mastic asphalt (SMA) mixtures with textile waste fibres. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 455, 139125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlawat, Y.; Bhardawaj, A.; Bhardwaj, R. An experimental study on the stability and flow characteristics of mastic asphalt mix using cigarette butt additive. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 65, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzadkia, M.; Yavary Nia, M.; Yavari Nia, M.; Shacheri, F.; Nourali, Z.; Torkashvand, J. Reduction of the environmental and health consequences of cigarette butt recycling by removal of toxic and carcinogenic compounds from its leachate. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 23942–23950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.T.; Mohajerani, A.; Giustozzi, F. Possible use of cigarette butt fiber modified bitumen in stone mastic asphalt. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohajerani, A.; Kurmus, H.; Rahman, M.T.; Smith, J.V.; Woo, S.S.; Jones, D.; Calderón, C. Bitumen and paraffin wax encapsulated cigarette butts: Physical properties and leachate analysis. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2022, 15, 931–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallo, P.; Valentin, J. Study on use of two types of waste cigarette filters in asphalt mixtures. In International Conference Series on Geotechnics, Civil Engineering and Structures, Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Geotechnics, Civil Engineering and Structures, CIGOS 2024, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, 4–5 April 2024; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 638–646. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, J.; Wu, Z.; Song, J.; Liu, X. Research on the road performance of cigarette butts modified asphalt mixture. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 1168, p. 022053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataranni, P.; Sangiorgi, C. A preliminary laboratory evaluation on the use of shredded cigarette filters as stabilizing fibers for stone mastic asphalts. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Tataranni, P.; Tarsi, G.; Sangiorgi, C. Performance evaluation of stone mastic asphalt reinforced with shredded waste e-cigarette butts. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 20, e03126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ameri, N.A.H.; Ramadhansyah, P.J. Performance of asphalt mixture incorporated encapsulated cigarette butts as bitumen modifier. Construction 2022, 2, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Chen, X.; Yu, J.; Cheng, G.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, L. Physical properties and rheological characteristics of cigarette butt-modified asphalt binders. Coatings 2025, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- General Directorate of Highways. State Highways Technical Specifications (HTS); General Directorate of Highways: Ankara, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- TS EN 1097-6; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates–Part 6: Determination of Particle Density and Water Absorption. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2013.

- TS EN 1097-7; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates–Part 7: Determination of the Particle Density of Filler–Pyknometer Method. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2008.

- ASTM D2041; Standard Test Method for Theoretical Maximum Specific Gravity and Density of Asphalt Mixtures (Rice Test). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- AASHTO T 96; Standard Method of Test for Resistance to Degradation of Small-Size Coarse Aggregate by Abrasion and Impact in the Los Angeles Machine. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2019.

- TS EN 1097-1; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates–Part 1: Determination of the Resistance to Wear (Micro-Deval Test). Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2011.

- TS EN 1367-2; Tests for Thermal and Weathering Properties of Aggregates–Part 2: Magnesium Sulfate Test. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2010.

- BS 812; Methods for Determination of Particle Shape: Flakiness Index. British Standards Institution (BSI): London, UK, 1989.

- ASTM D1664; Standard Test Method for Coating and Stripping of Bitumen–Aggregate Mixtures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- TS EN 933-9; Tests for Geometrical Properties of Aggregates–Part 9: Assessment of Fines–Methylene Blue Test. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2010.

- TS EN 12591; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders–Specifications for Paving Grade Bitumens. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2011.

- TS EN 14023; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders–Framework Specification for Polymer Modified Bitumens. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE); Turkish and European Standard: Ankara, Turkey, 2006.

- Anonim. What Is ELVALOY™ 5160 Copolymer? Available online: https://www.dow.com/en-us/pdp.elvaloy-5160-copolymer.1891824z.html#overview (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- ASTM D792; Standard Test Methods for Density and Specific Gravity (Relative Density) of Plastics by Displacement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ISO 1183; Plastics–Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ASTM D1238; Standard Test Method for Melt Flow Rates of Thermoplastics by Extrusion Plastometer. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- ISO 1133; Plastics–Determination of the Melt Mass-Flow Rate (MFR) and Melt Volume-Flow Rate (MVR) of Thermoplastics. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- ASTM D3418; Standard Test Method for Transition Temperatures of Polymers by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- ISO 3146; Plastics–Determination of Melting Behaviour (Melting Temperature or Melting Range) of Semi-Crystalline Polymers by Differential Scanning Calorimetry. International Organization for Standardization (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2000.

- Kurt, Y. Experimental Investigation of the Use of Waste Paper Cups in Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures. Master’s Thesis, Graduate Education Institute, Isparta University of Applied Sciences, Isparta, Turkey, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Blazejowski, K. Stone Matrix Asphalt: Theory and Practice; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera-Puerta, C.F.; Suspes-García, S.; Galindres-Jimenez, D.M.; Cifuentes-Galindres, D.; Tinoco, L.E.; Piraján, J.C.M.; Murillo-Acevedo, Y. Exploring the thermal decomposition of cigarette butts and its role in chromium adsorption processes. Heliyon 2025, 11, e42162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Mohajerani, A. Thermal conductivity and environmental aspects of cigarette butt modified asphalt. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, Y.; Xue, Y. Reutilization of Recycled Cellulose Diacetate from Discarded Cigarette Filters in Production of Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 770150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Yu, J.; Wu, S. Effect of montmorillonite organic modification on ultraviolet aging properties of SBS modified bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 27, 553–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadiroudbari, M.; Tavakoli, A.; Aghjeh, M.K.R.; Rahi, M. Effect of Nanoclay on the Morphology of Polyethylene Modified Bitumen. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 116, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansar, M.; Sikandar, M.A.; Althoey, F.; Tariq, M.A.U.R.; Alyami, S.H.; Elsayed Elkhatib, S. Rheological, Aging, and Microstructural Properties of Polycarbonate and Polytetrafluoroethylene Modified Bitumen. Polymers 2022, 14, 3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Wang, L.; Zeng, X.; Wu, S.; Li, B. Effect of Montmorillonite on Properties of Styrene–Butadiene–Styrene Copolymer Modified Bitumen. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2007, 47, 1289–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TS EN 13399; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders–Determination of Storage Stability of Modified Bitumen. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2018.

- TS EN 13398; Bitumen and Bituminous Binders–Determination of Elastic Recovery. Turkish Standards Institution (TSE): Ankara, Turkey, 2010.

- Sağlık, A.; Orhan, F.; Güngör, A.G. BSK Kaplamalı Yollar Için Bitüm Sınıfı Seçim Haritaları; Ulaştırma, T.C., Ed.; Denizcilik ve Haberleşme Bakanlığı Karayolları Genel Müdürlüğü: Ankara, Türkiye, 2012. (In Turkish) [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D1559; Standard Test Method for Resistance to Plastic Flow of Bituminous Mixtures Using Marshall Apparatus. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 1989.

- Yalçın, E. The Assessment of the Effects of Hydrated Lime Usage as Filler on the Performance of Mixtures Prepared with Modified Bitumen. Master’s Thesis, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Fırat University, Elazig, Turkey, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D6931-17; Standard Test Method for Indirect Tensile (IDT) Strength of Bituminous Mixtures. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- AASHTO T 283; Standard Method of Test for Resistance of Compacted Asphalt Mixtures to Moisture-Induced Damage. American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO): Washington, DC, USA, 2014.

- Durmaz, A.C.; Morova, N. Investigation of performance properties of milled carbon fiber reinforced hot mix asphalt. Mater. Sci. 2024, 30, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM E965; Standard Test Method for Measuring Pavement Macrotexture Depth Using a Volumetric Technique (Sand Patch Test). ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Özay, O.; Öztürk, E.A. Performance of modified porous asphalt mixtures. J. Fac. Eng. Archit. Gazi Univ. 2013, 28, 577–586. [Google Scholar]

| Test | Result | Standard | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse Aggregate Apparent Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | 2.680 | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Coarse Aggregate Bulk Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | 2.667 | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Coarse Aggregate Water Absorption (%) | 0.4% | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Fine Aggregate Apparent Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | 2.662 | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Fine Aggregate Bulk Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | 2.614 | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Fine Aggregate Water Absorption (%) | 0.6% | TS EN 1097-6 [35] | |

| Filler Specific Gravity (g/cm3) | 2.610 | TS EN 1097-7 [36] | |

| Effective Specific Gravity of Mixture (Experimental) | 2.666 | ASTM D-2041 [37] | |

| Effective Specific Gravity of Mixture (Calculated) | 2.658 | - | |

| Test | Result | HTS Requirement (SMA Wearing Course) [34] | Standard |

| Resistance to Fragmentation (Los Angeles Abrasion Loss, %) | 20 | ≤25 | AASHTO T-96 [38] |

| Abrasion Resistance (Micro-Deval, %) | 9.1 | TS EN 1097-1 [39] | |

| Durability Against Weathering (MgSO4, Freeze–Thaw Loss, %) | 1.6 | ≤14 | TS EN 1367-2 [40] |

| Flakiness Index (%) | 17 | ≤25 | BS 812 [41] |

| Stripping Resistance (%) | 70–75 | ≥60 | ASTM D1664 [42] |

| Methylene Blue Value (g/kg, of Mixture) | 1.5 | ≤1.5 | TS EN 933-9 [43] |

| Sieve Diameter | SMA Type-1A Mixture Gradation [34] | Sample Weight: 1050 g | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inch | mm | % Passing | % Retained | Retained Weight (g) | Cumulative Weight (g) |

| ¾” | 19.0 | 100.0 | - | - | - |

| ½” | 12.5 | 93.5 | 6.5 | 68.25 | 68.25 |

| 3/8” | 9.5 | 69.9 | 23.6 | 247.8 | 316.05 |

| No. 4 | 4.75 | 34.1 | 35.8 | 375.9 | 691.95 |

| No. 10 | 2.00 | 23.4 | 10.7 | 112.35 | 804.30 |

| No. 40 | 0.425 | 15.4 | 8 | 84 | 888.30 |

| No. 80 | 0.180 | 11.9 | 3.5 | 36.75 | 925.05 |

| No. 200 | 0.075 | 9.2 | 2.7 | 28.35 | 953.40 |

| Pan (Below 0.075 mm) | - | 9.2 | 96.6 | 1050 | |

| Physical Properties | ||

| Property | Nominal Values | Test Method(s) |

| Density (ρ) | 0.95 g/cm3 | ASTM D792/ISO 1183 [47,48] |

| Melt Flow Index (190 °C/2.16 kg) | 12 g/10 min | ASTM D1238/ISO 1133 [49,50] |

| Thermal Properties | ||

| Property | Nominal Values | Test Method(s) |

| Melting Point (DSC) | 80 °C (176 °F) | ASTM D3418/ISO 3146 [51,52] |

| Freezing Point (DSC) | 55 °C (131 °F) | ASTM D3418/ISO 3146 [51,52] |

| Processing Information | ||

| Property | Value | |

| Maximum Processing Temperature | 220 °C (428 °F) | |

| Property | Value |

|---|---|

| Chemical Formula | Hn+2PnO3n+1 |

| Physical Form | Liquid |

| Concentration | % ≥ 90– ≤ 100 |

| Metal Corrosion Rate | May corrode metals |

| Appearance | Thickness: 4–7 mm |

|---|---|

| Schellenberg Drain-down Value | Maximum 0.18% (Specification Limit: 0.3%) |

| Moisture Content | Maximum 5% |

| Oil Absorption Capacity | At least 5 times the weight of cellulose |

| Sample Code | Description | Sample Code | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| E1.6-SG-0.1 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.1 | E1.6-SL-0.1 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.1 |

| E1.6-SG-0.2 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.2 | E1.6-SL-0.2 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.2 |

| E1.6-SG-0.3 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.3 | E1.6-SL-0.3 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.3 |

| E1.6-SG-0.4 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.4 | E1.6-SL-0.4 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.4 |

| E1.6-SG-0.5 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.5 | E1.6-SL-0.5 | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.5 |

| E1.7-SG-0.1 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.1 | E1.7-SL-0.1 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.1 |

| E1.7-SG-0.2 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.2 | E1.7-SL-0.2 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.2 |

| E1.7-SG-0.3 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.3 | E1.7-SL-0.3 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.3 |

| E1.7-SG-0.4 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.4 | E1.7-SL-0.4 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.4 |

| E1.7-SG-0.5 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.5 | E1.7-SL-0.5 | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.5 |

| E1.8-SG-0.1 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.1 | E1.8-SL-0.1 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.1 |

| E1.8-SG-0.2 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.2 | E1.8-SL-0.2 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.2 |

| E1.8-SG-0.3 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.3 | E1.8-SL-0.3 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.3 |

| E1.8-SG-0.4 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.4 | E1.8-SL-0.4 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.4 |

| E1.8-SG-0.5 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SG %0.5 | E1.8-SL-0.5 | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA + SL %0.5 |

| Reference Samples | |||

| B-SG-0.1 | Pure bitumen + SG %0.1 | B-SL-0.1 | Pure bitumen + SL %0.1 |

| B-SG-0.2 | Pure bitumen + SG %0.2 | B-SL-0.2 | Pure bitumen + SL %0.2 |

| B-SG-0.3 | Pure bitumen + SG %0.3 | B-SL-0.3 | Pure bitumen+ SL %0.3 |

| B-SG-0.4 | Pure bitumen + SG %0.4 | B-SL-0.4 | Pure bitumen + SL %0.4 |

| B-SG-0.5 | Pure bitumen + SG %0.5 | B-SL-0.5 | Pure bitumen + SL %0.5 |

| B-SMA | Pure bitumen (unmodified)-SMA | ||

| E1.6-SMA | %1.6 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA (unmodified)-SMA | ||

| E1.7-SMA | %1.7 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA (unmodified)-SMA | ||

| E1.8-SMA | %1.8 Elvaloy + %0.2 PPA (unmodified)-SMA | ||

| Sample | Elvaloy RET (%) | PPA (%) | Penetration (0.1 mm) | Softening Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 0.0 | 0.0 | 58 | 51.0 |

| E1.6 | 1.6 | 0.2 | 45 | 60.0 |

| E1.7 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 47 | 61.0 |

| E1.8 | 1.8 | 0.2 | 48 | 62.4 |

| Sample Code | Mass Loss (%) | Residual Penetration (%) | Softening Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B-50/70 | 0.11 | 81.2 | 53.8 |

| E1.6 | 0.05 | 75.6 | 63.0 |

| E1.7 | 0.03 | 70.2 | 64.0 |

| E1.8 | 0.02 | 64.0 | 66.4 |

| Bitumen Content | Vh (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1.6-SG-0.1 | E1.6-SG-0.2 | E1.6-SG-0.3 | E1.6-SG-0.4 | E1.6-SG-0.5 | E1.6-SL-0.1 | E1.6-SL-0.2 | E1.6-SL-0.3 | E1.6-SL-0.4 | E1.6-SL-0.5 | ||

| 5% | 4.84 | 5.05 | 6.07 | 6.42 | 6.68 | 4.83 | 4.97 | 7.03 | 7.82 | 7.78 | |

| 5.5% | 4.09 | 3.93 | 4.58 | 5.39 | 5.42 | 3.09 | 3.35 | 5.57 | 5.32 | 5.69 | |

| 6% | 2.71 | 3.01 | 2.97 | 4.28 | 3.25 | 1.53 | 1.50 | 4.30 | 4.24 | 4.19 | |

| 6.5% | 1.36 | 1.69 | 1.52 | 3.38 | 3.55 | 1.30 | 1.30 | 3.15 | 3.29 | 3.26 | |

| 7% | 1.11 | 1.32 | 1.23 | 3.04 | 3.71 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 2.74 | 2.76 | 2.92 | |

| E1.7-SG-0.1 | E1.7-SG-0.2 | E1.7-SG-0.3 | E1.7-SG-0.4 | E1.7-SG-0.5 | E1.7-SL-0.1 | E1.7-SL-0.2 | E1.7-SL-0.3 | E1.7-SL-0.4 | E1.7-SL-0.5 | ||

| 5% | 5.09 | 5.99 | 7.51 | 7.71 | 6.78 | 5.89 | 5.93 | 7.30 | 7.47 | 7.55 | |

| 5.5% | 3.81 | 4.58 | 5.47 | 6.24 | 5.51 | 4.82 | 4.90 | 5.47 | 5.51 | 5.59 | |

| 6% | 2.97 | 3.16 | 3.71 | 5.02 | 3.34 | 3.71 | 3.79 | 4.12 | 3.99 | 4.08 | |

| 6.5% | 1.61 | 2.15 | 2.59 | 3.01 | 3.66 | 2.68 | 2.72 | 2.72 | 3.09 | 3.17 | |

| 7% | 1.32 | 1.85 | 2.35 | 3.67 | 3.80 | 1.89 | 1.94 | 2.43 | 1.40 | 1.48 | |

| E1.8-SG-0.1 | E1.8-SG-0.2 | E1.8-SG-0.3 | E1.8-SG-0.4 | E1.8-SG-0.5 | E1.8-SL-0.1 | E1.8-SL-0.2 | E1.8-SL-0.3 | E1.8-SL-0.4 | E1.8-SL-0.5 | ||

| 5% | 5.06 | 5.58 | 6.88 | 7.19 | 6.89 | 6.21 | 6.29 | 7.40 | 7.27 | 7.35 | |

| 5.5% | 3.80 | 4.16 | 4.85 | 5.64 | 4.97 | 5.32 | 5.34 | 5.43 | 5.68 | 5.77 | |

| 6% | 2.71 | 3.01 | 3.31 | 4.45 | 3.81 | 4.39 | 4.43 | 3.91 | 4.13 | 4.22 | |

| 6.5% | 1.81 | 2.12 | 2.26 | 3.63 | 3.41 | 3.42 | 3.57 | 2.85 | 2.63 | 2.71 | |

| 7% | 1.08 | 1.50 | 1.69 | 3.17 | 3.77 | 2.43 | 2.77 | 2.26 | 1.16 | 1.24 | |

| B-SG-0.1 | B-SG-0.2 | B-SG-0.3 | B-SG-0.4 | B-SG-0.5 | B-SL-0.1 | B-SL-0.2 | B-SL-0.3 | B-SL-0.4 | B-SL-0.5 | ||

| 5% | 4.61 | 4.72 | 4.60 | 5.17 | 5.01 | 4.62 | 6.52 | 6.74 | 5.29 | 6.90 | |

| 5.5% | 2.67 | 3.28 | 3.56 | 3.81 | 3.89 | 3.60 | 3.88 | 4.62 | 3.81 | 3.64 | |

| 6% | 2.03 | 2.15 | 2.40 | 2.60 | 2.97 | 2.38 | 2.78 | 2.69 | 2.40 | 2.52 | |

| 6.5% | 1.71 | 1.61 | 1.36 | 1.81 | 1.65 | 1.40 | 2.03 | 1.60 | 1.73 | 1.15 | |

| 7% | 0.99 | 1.23 | 1.07 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.02 | 0.85 | 0.77 | 1.40 | 1.73 | |

| B-SMA | E1.6-SMA | E1.7-SMA | E1.8-SMA | ||||||||

| 5% | 4.04 | 3.89 | 4.60 | 4.91 | |||||||

| 5.5% | 2.87 | 3.14 | 3.56 | 3.49 | |||||||

| 6% | 1.87 | 2.46 | 2.40 | 2.35 | |||||||

| 6.5% | 0.85 | 1.73 | 1.36 | 1.48 | |||||||

| 7% | 0.36 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 0.89 | |||||||

| Series | Opt. Bitumen (%) | Bitumen (kg) | Bitumen Cost ($) | Elvaloy Cost ($) | Fiber Cost ($) | Total ($/t) | Difference in SG Compared to SL ($) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-SG | 5.48 | 54.76 | 20.37 | 0 | 0.87 | 21.24 | −1.68 (-cost saving) |

| B-SL | 5.62 | 56.56 | 20.89 | 0 | 1.8 | 22.92 | |

| E1.6-SG | 6.02 | 59.46 | 22.16 | 5.73 | 0.87 | 28.76 | −2.15 (-cost saving) |

| E1.6-SL | 6.14 | 61.42 | 22.87 | 5.91 | 1.8 | 30.91 | |

| E1.7-SG | 6.08 | 60.82 | 22.63 | 6.21 | 0.87 | 29.8 | −1.64 (-cost saving) |

| E1.7-SL | 6.17 | 61.64 | 22.96 | 6.31 | 1.8 | 31.44 | |

| E1.8-SG | 6.04 | 60.78 | 22.46 | 6.65 | 0.87 | 30 | −2.53 (-cost saving) |

| E1.8-SL | 6.33 | 63.32 | 23.59 | 6.85 | 1.8 | 32.53 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Varol Morova, H.; Özel, C. Experimental Investigation of Polymer-Modified Bituminous Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts. Materials 2025, 18, 5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235340

Varol Morova H, Özel C. Experimental Investigation of Polymer-Modified Bituminous Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts. Materials. 2025; 18(23):5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235340

Chicago/Turabian StyleVarol Morova, Hande, and Cengiz Özel. 2025. "Experimental Investigation of Polymer-Modified Bituminous Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts" Materials 18, no. 23: 5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235340

APA StyleVarol Morova, H., & Özel, C. (2025). Experimental Investigation of Polymer-Modified Bituminous Stone Mastic Asphalt Mixtures Containing Cellulose Acetate Recycled from Cigarette Butts. Materials, 18(23), 5340. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18235340