Optimizing the Tensile Performance of Repaired CFRP Laminates with Different Patch Parameters Using a Surrogate-Based Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

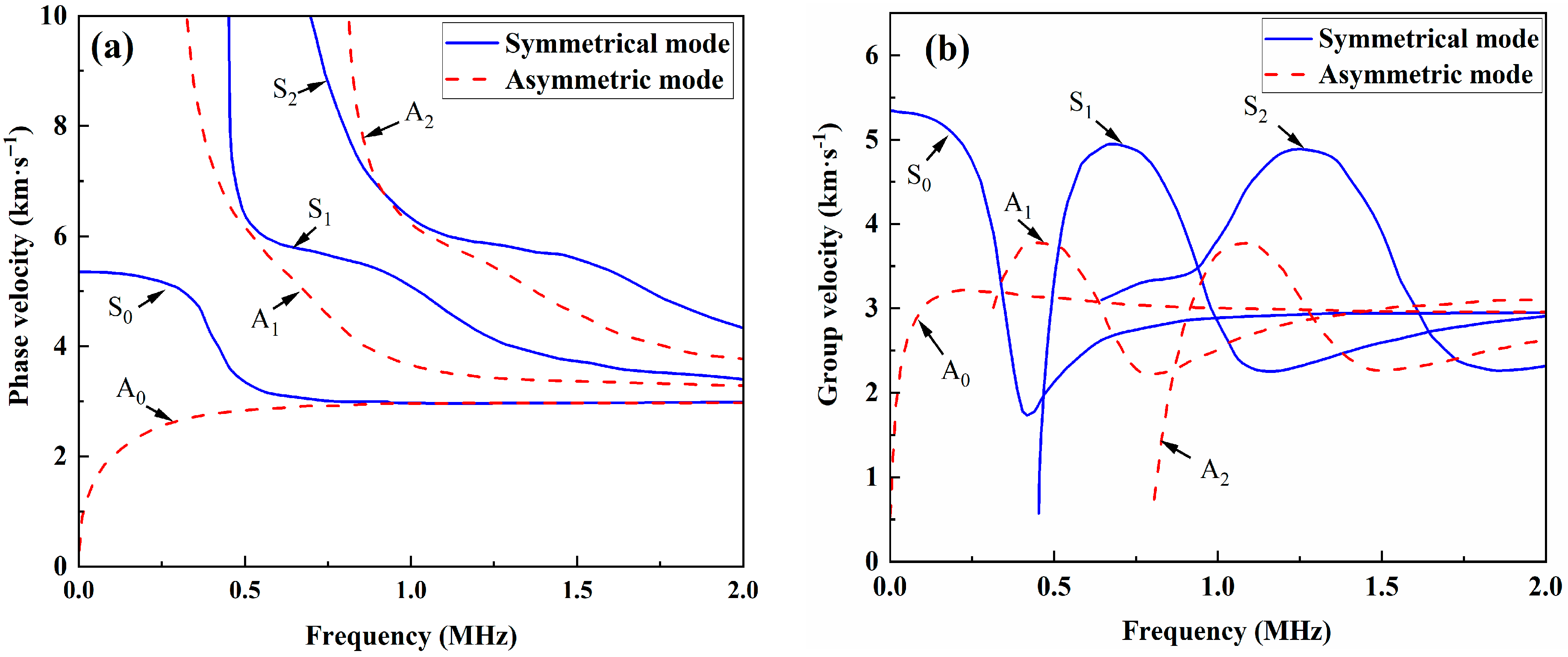

2. Theory of Lamb Waves

3. Finite-Element Simulation

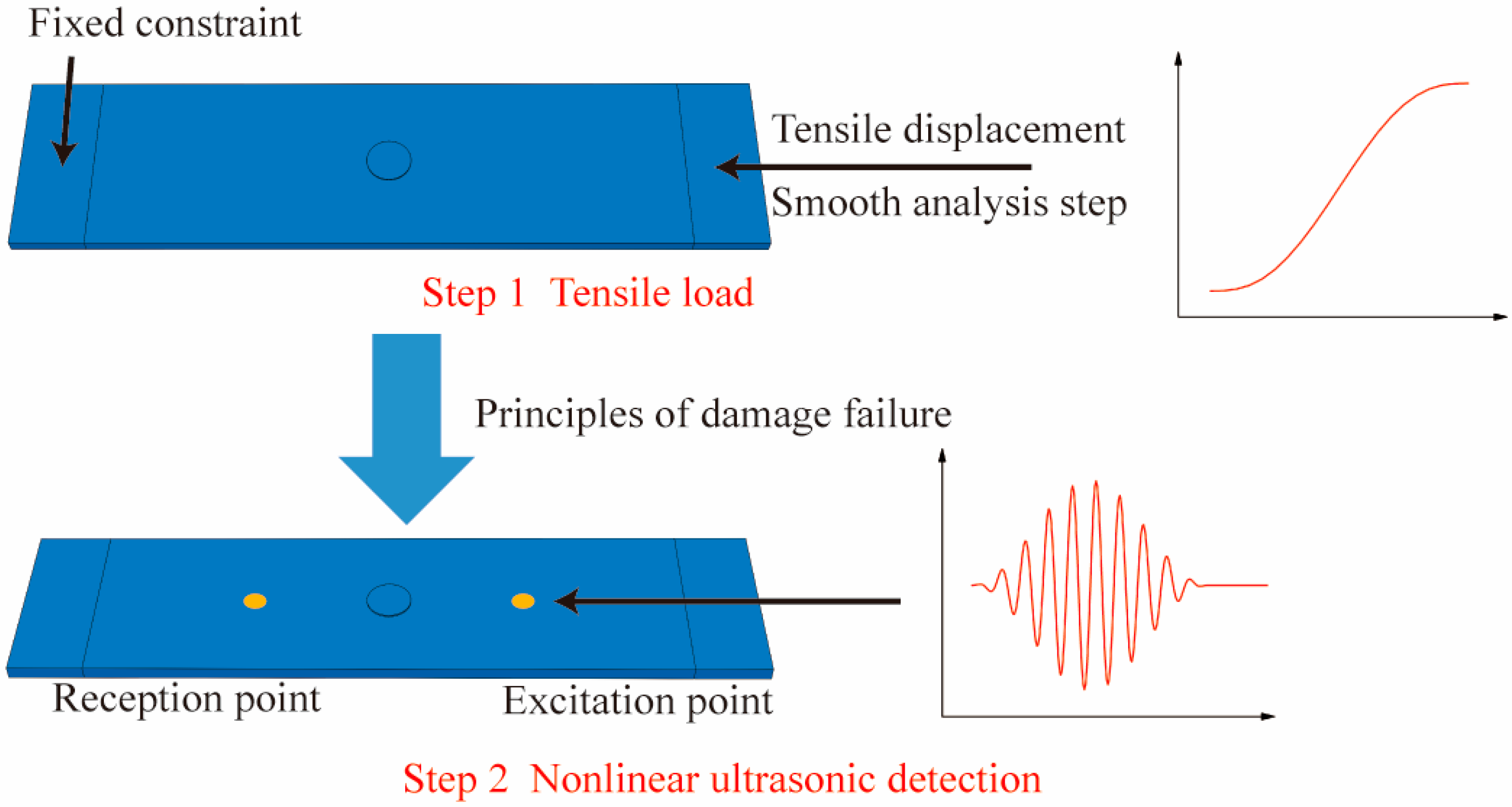

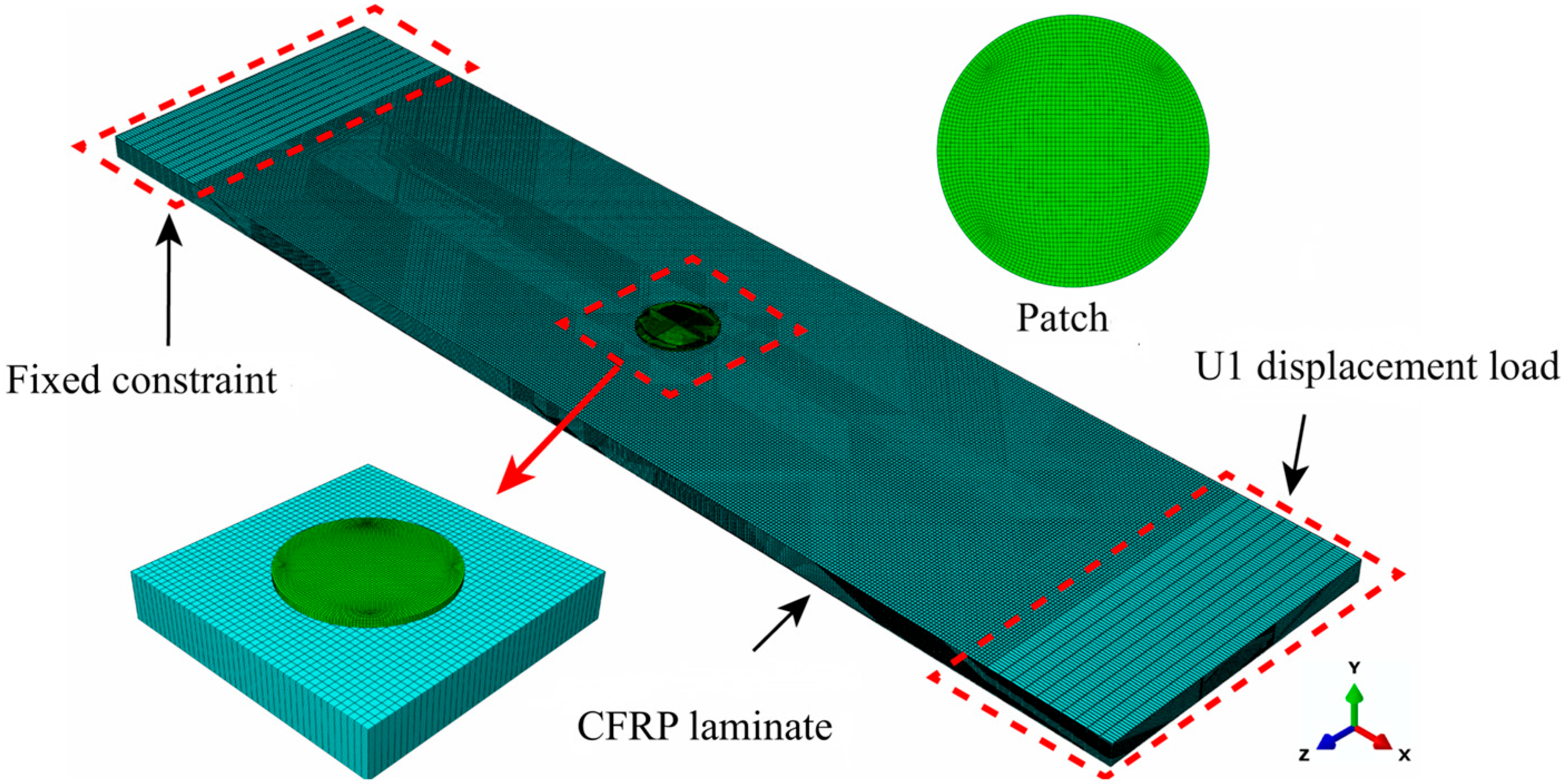

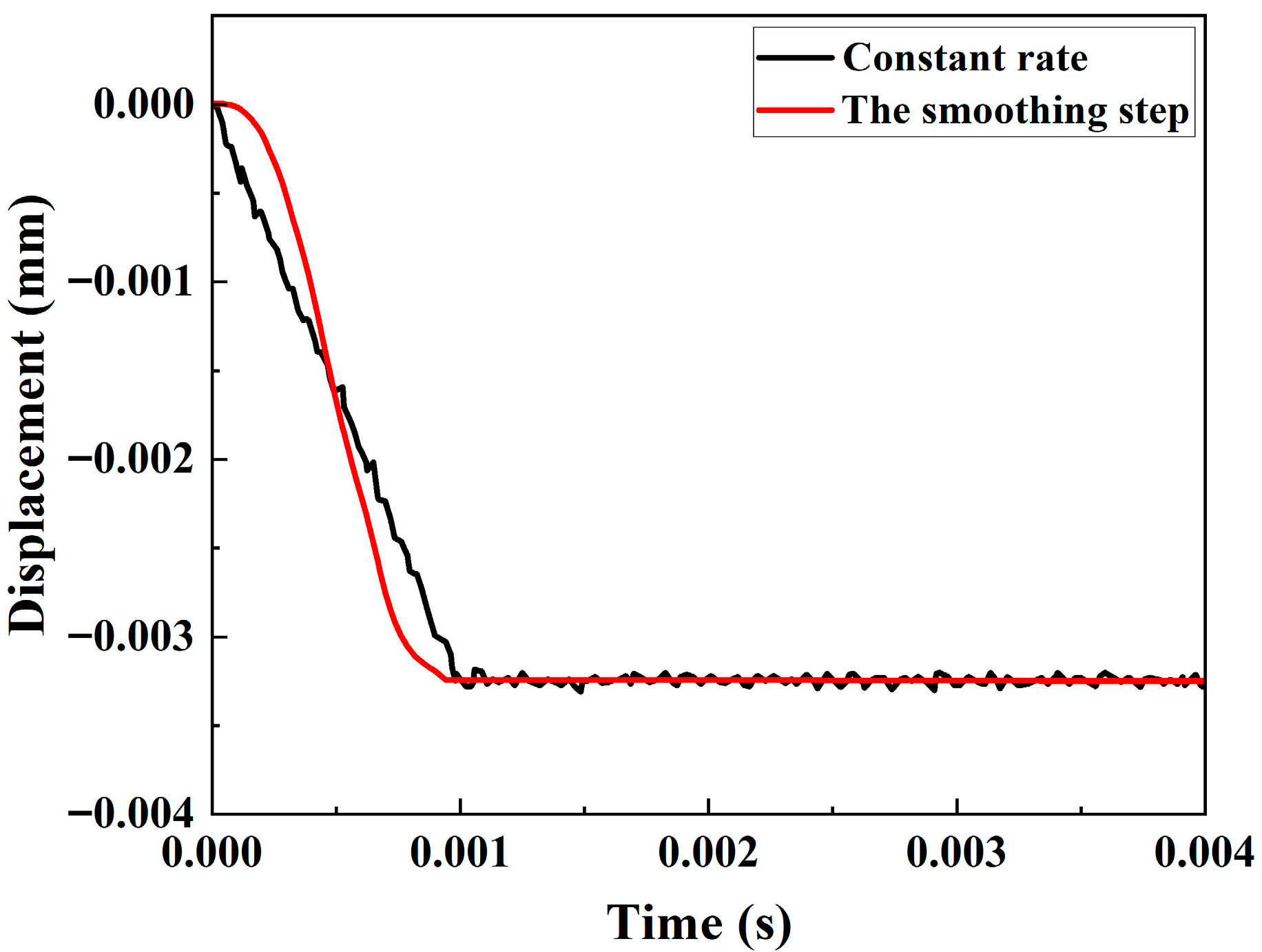

3.1. Finite-Element Model for Tensile Testing

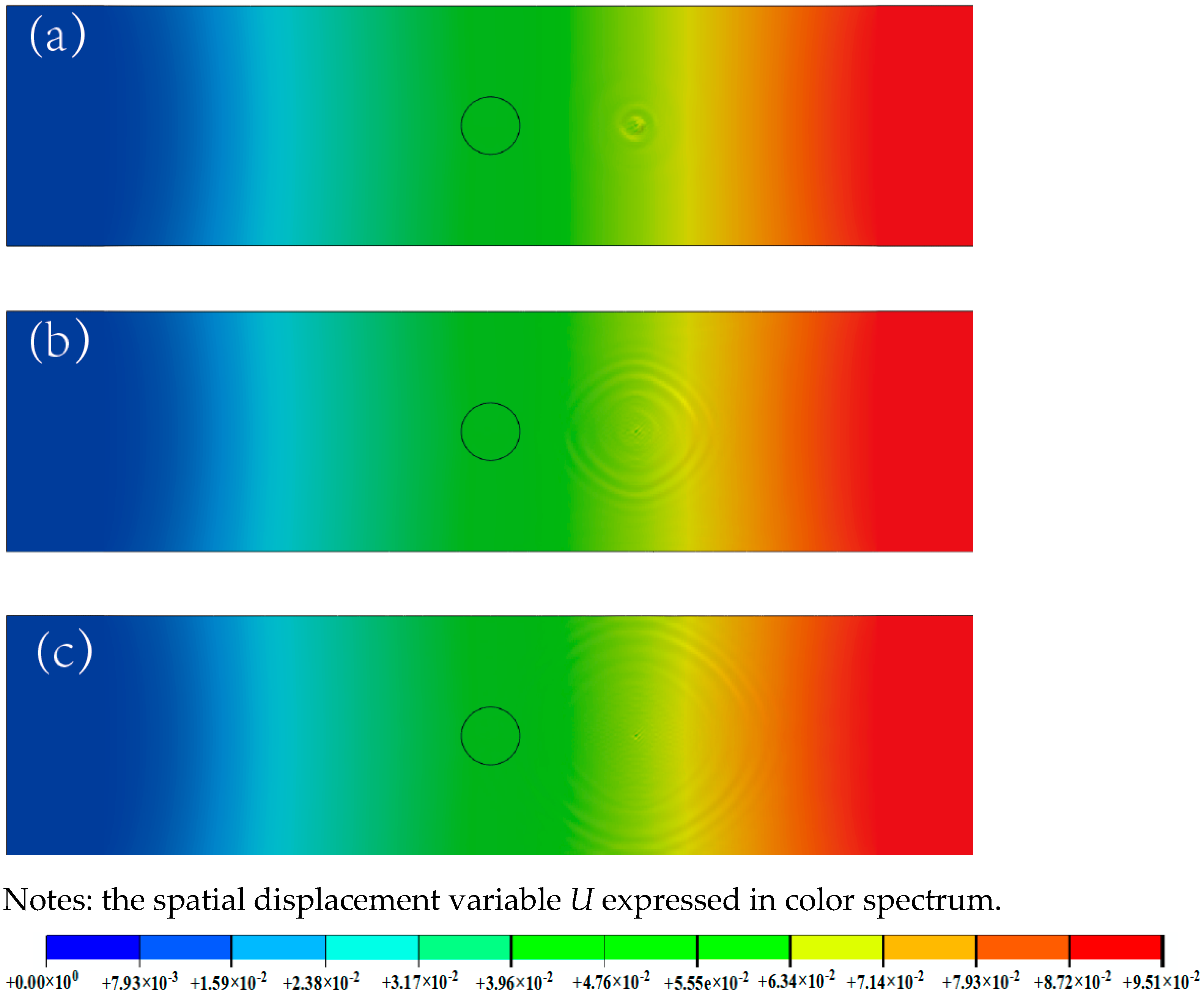

3.2. Nonlinear Lamb Wave Detection

4. Experimental Work

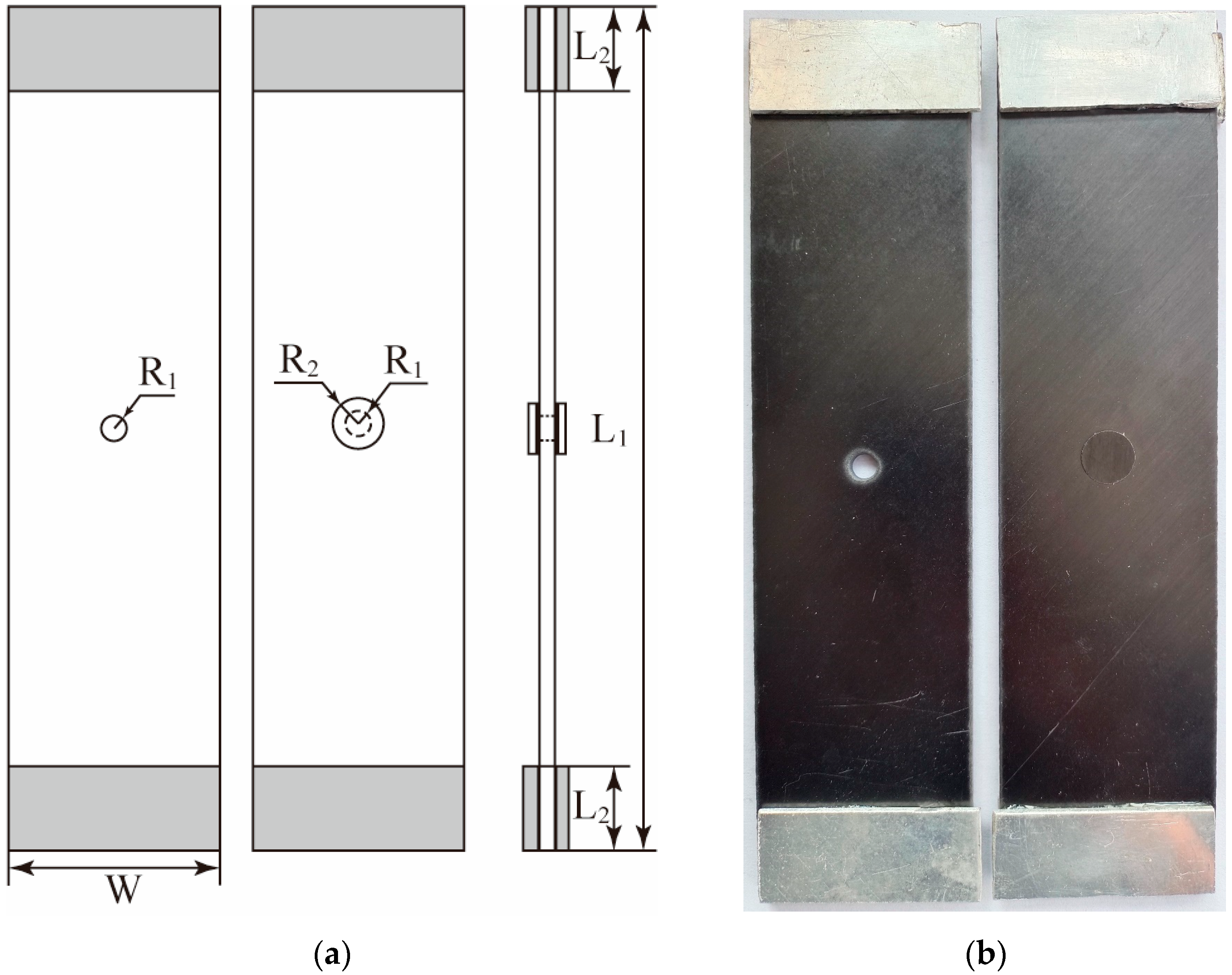

4.1. Specimen Preparation

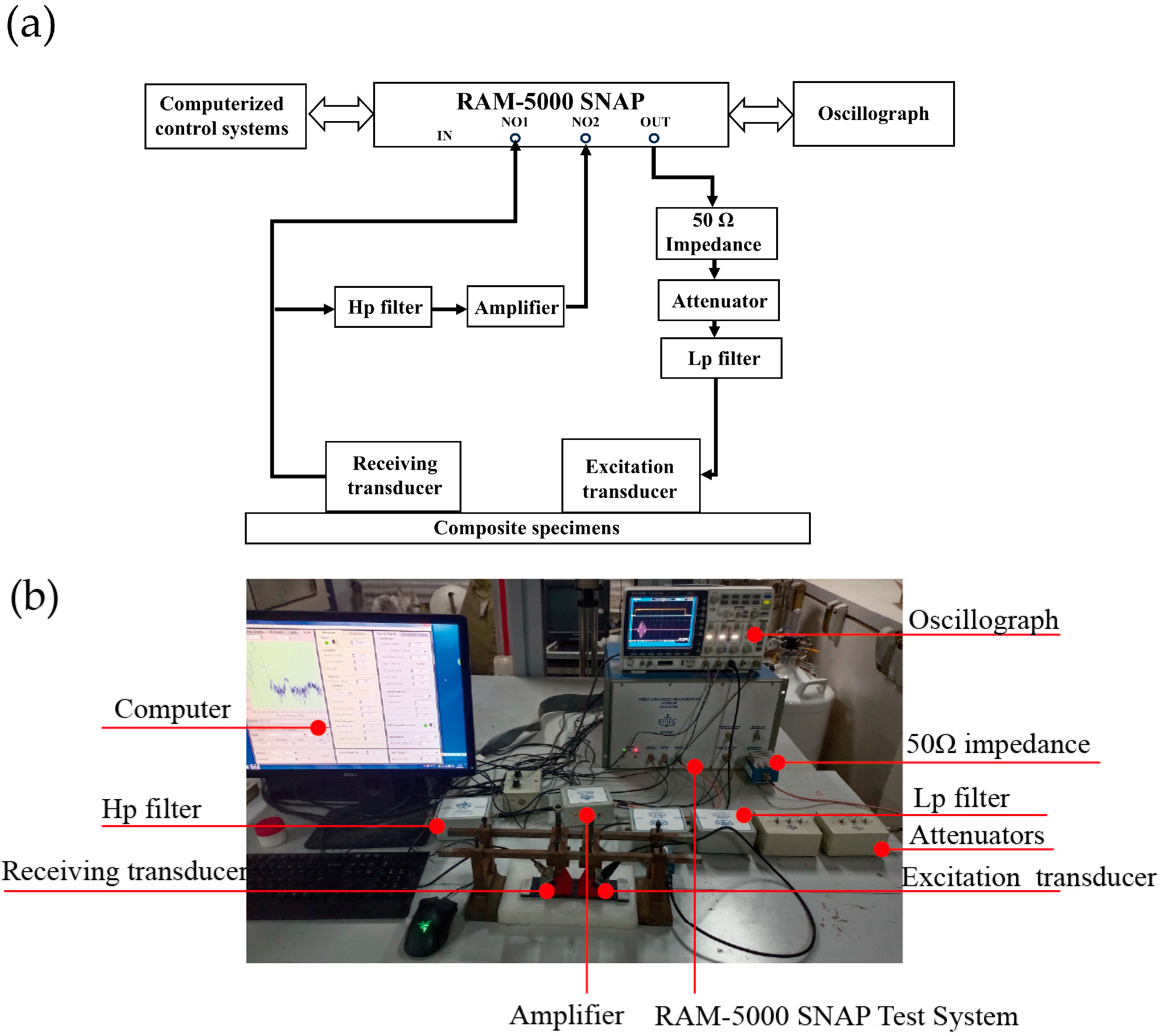

4.2. Experimental Design

5. Results and Discussion

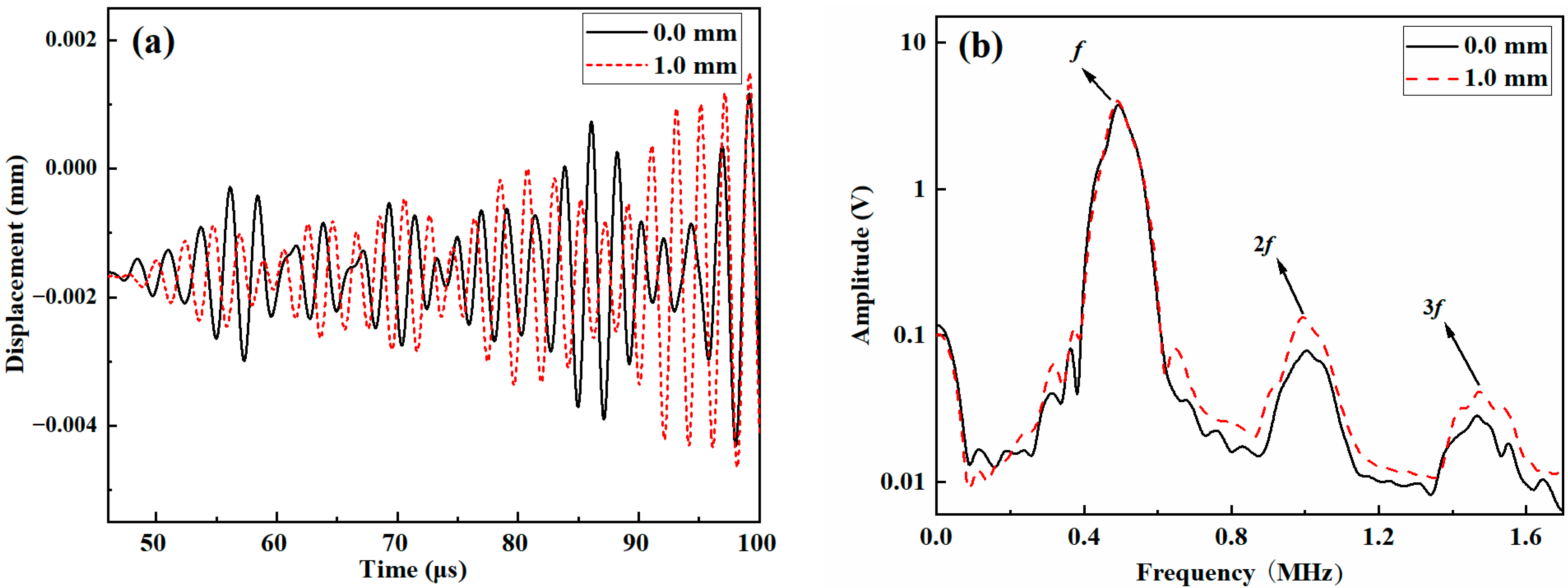

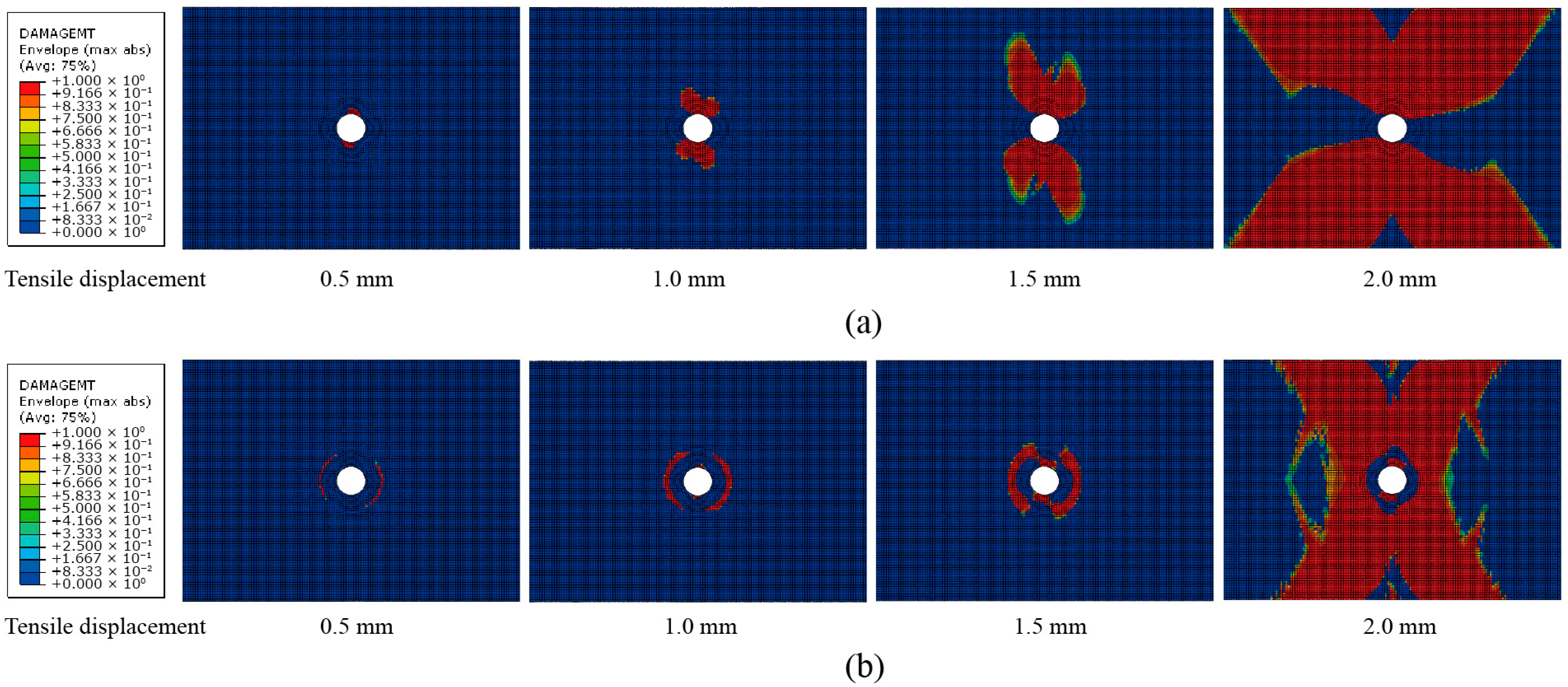

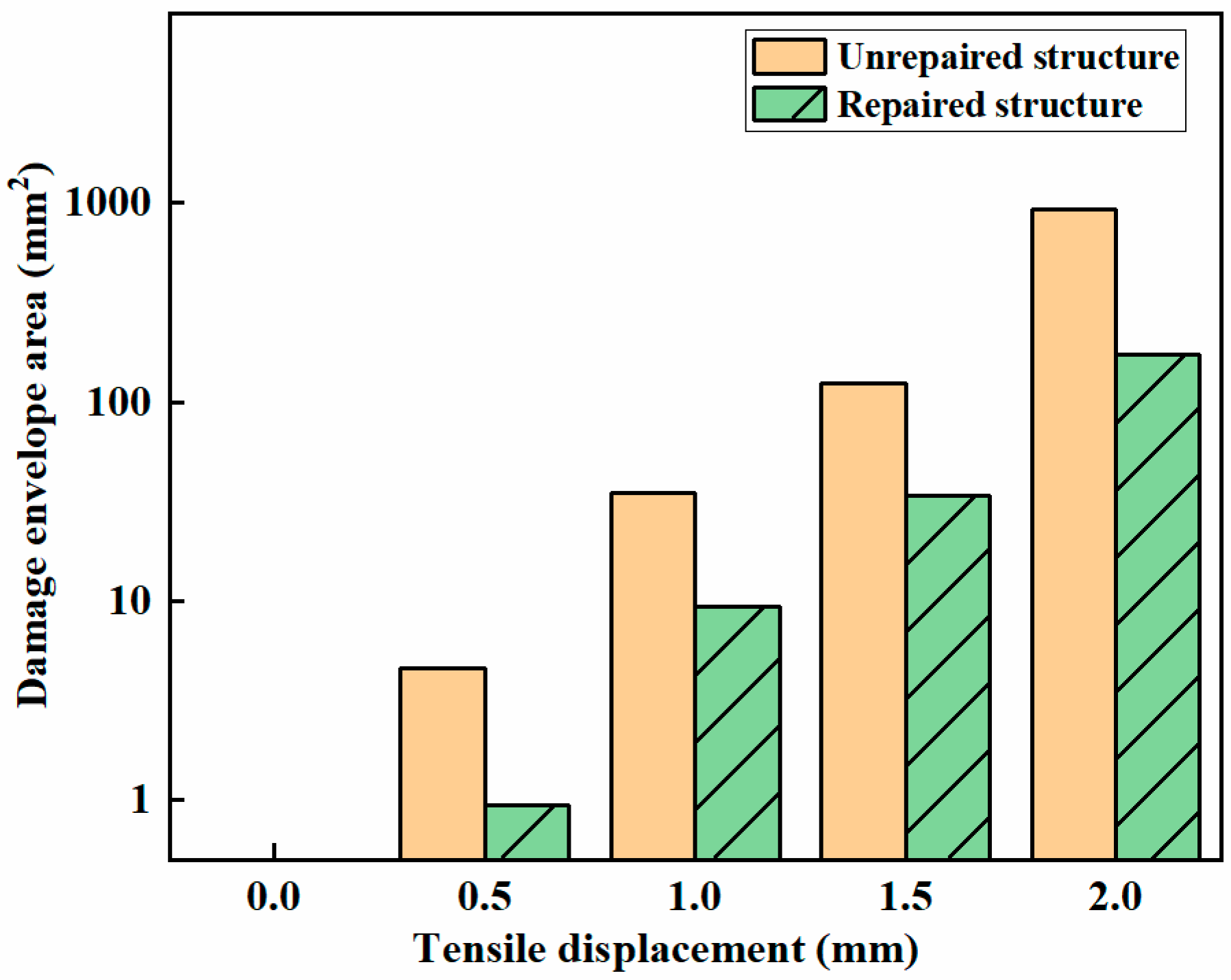

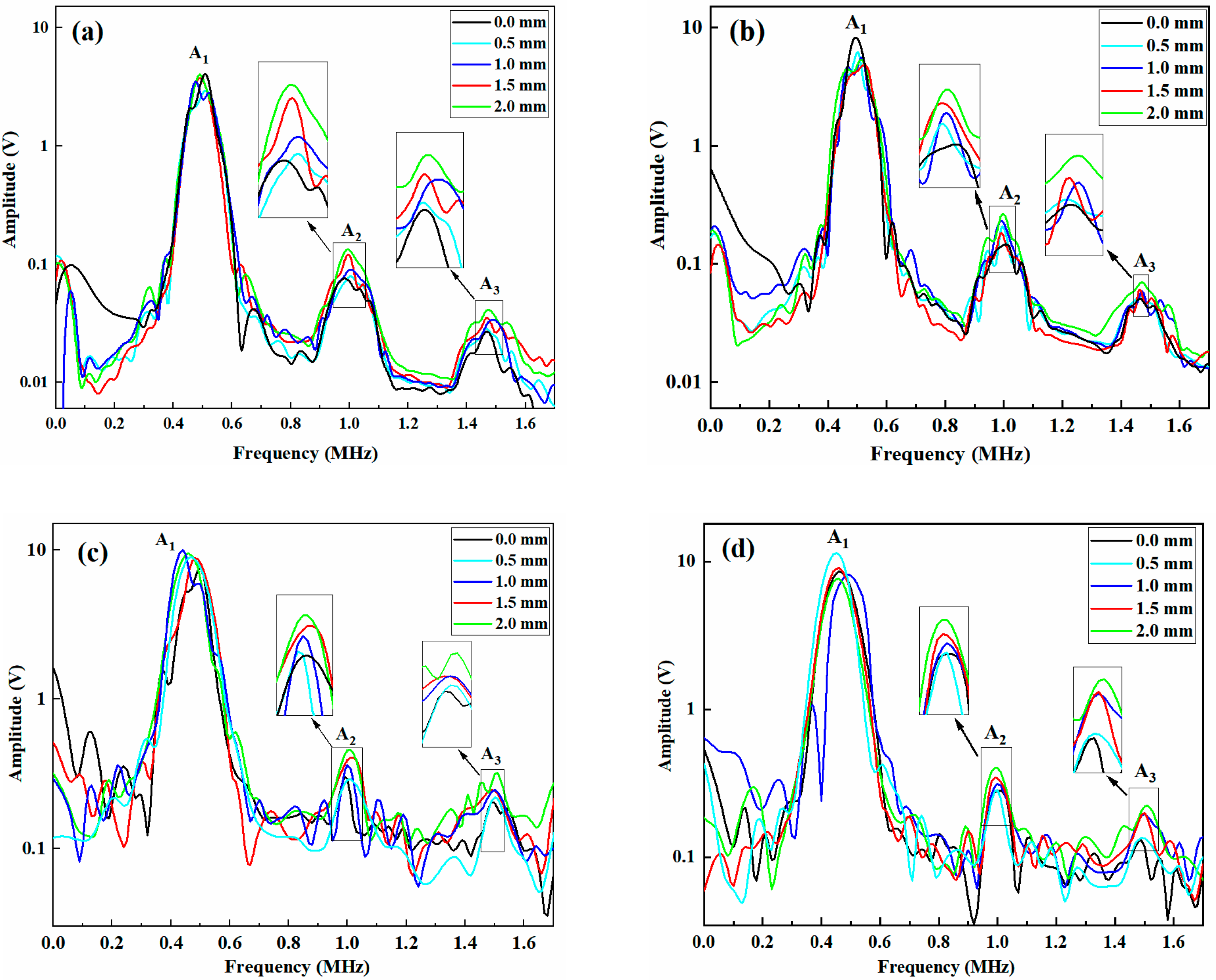

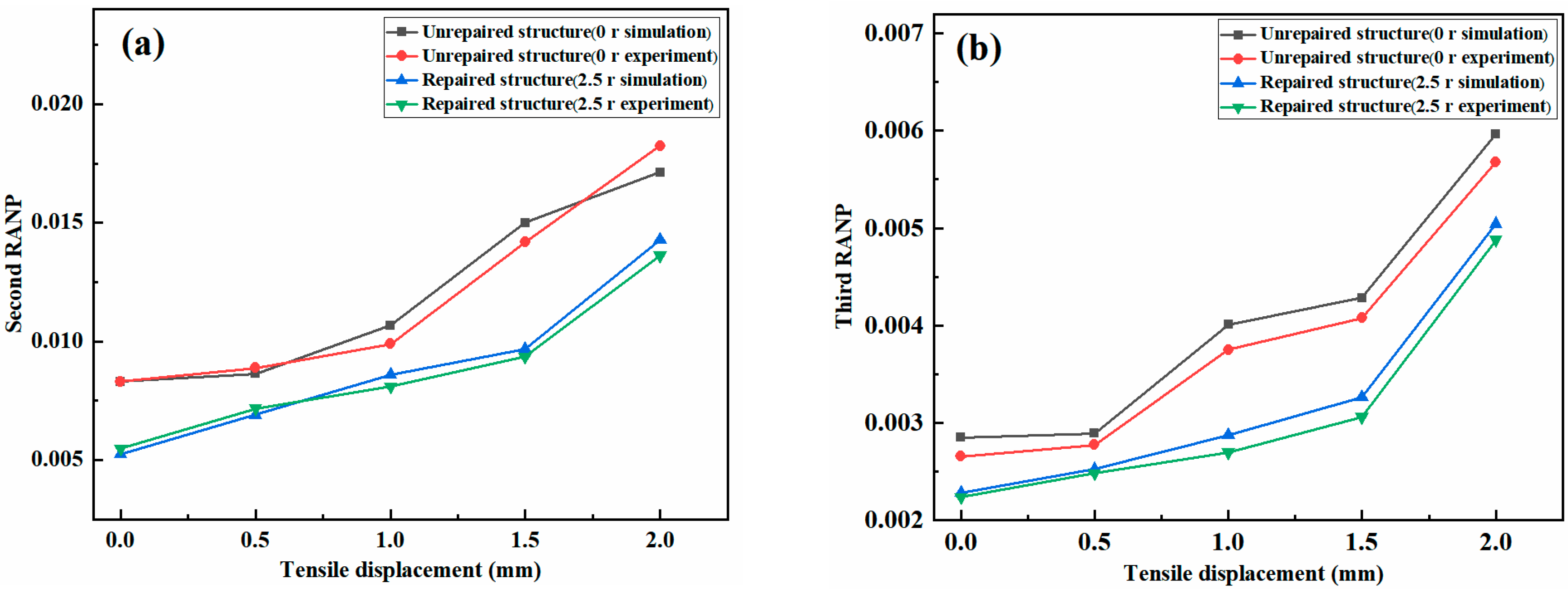

5.1. Validity of the Finite-Element Model

5.2. Analysis of the Tensile Results

5.3. Effects of the Patch Parameters on MRANPs

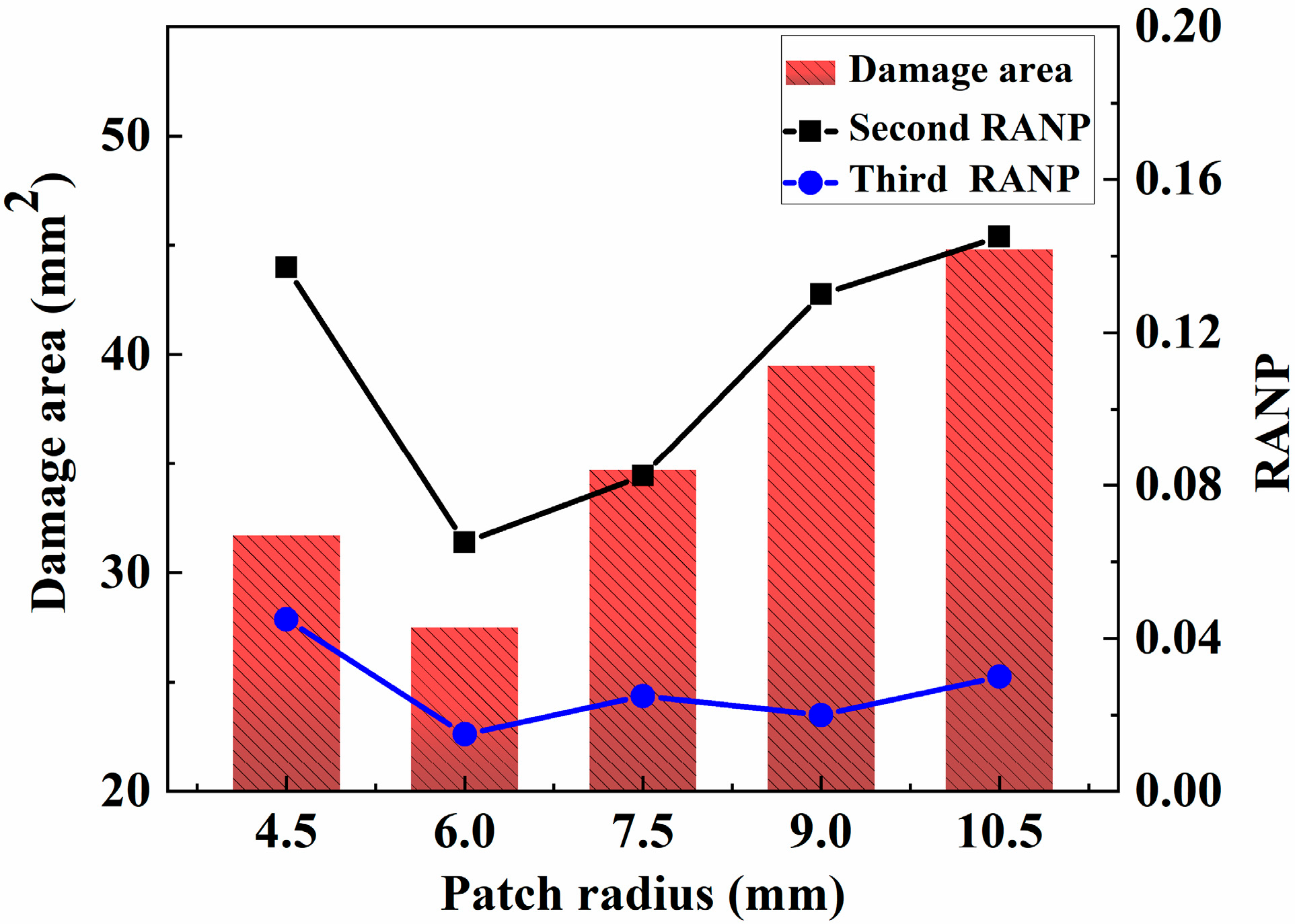

5.3.1. Effect of the Patch Radius on the Nonlinear Coefficients

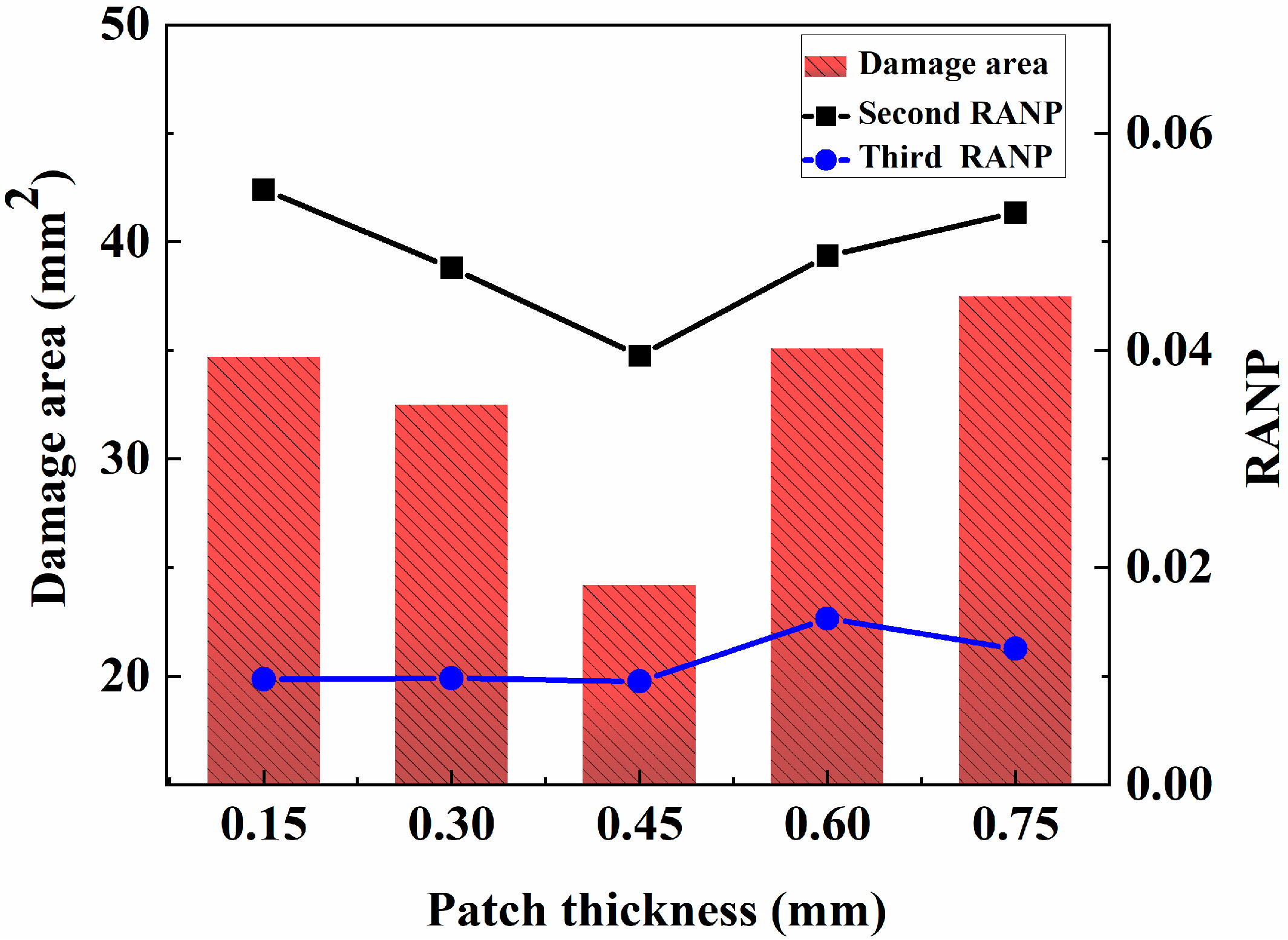

5.3.2. Effects of the Sheet Thickness on the Nonlinear Coefficient

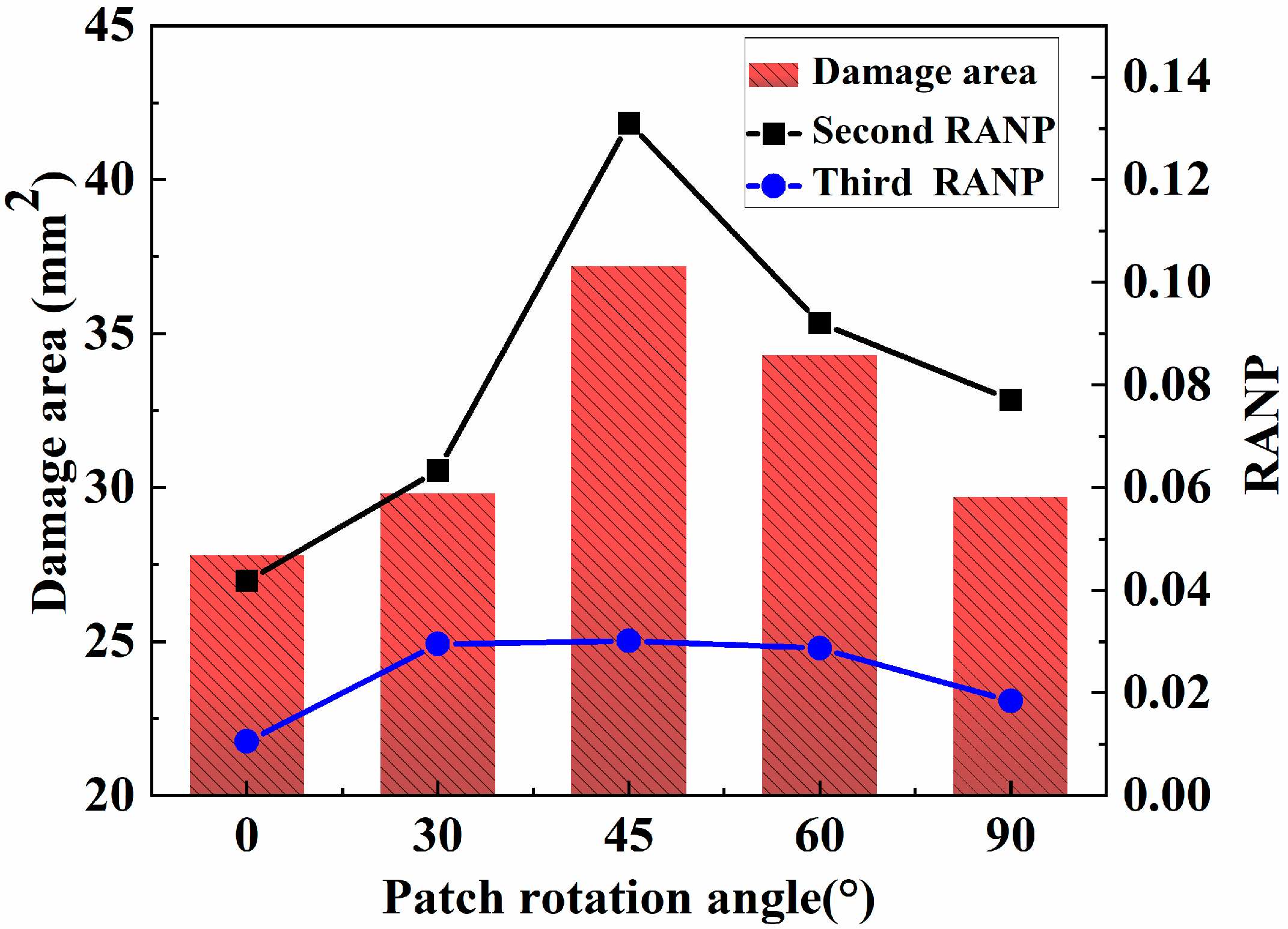

5.3.3. Effects of the Patch Rotation Angle on the Nonlinear Coefficients

6. Optimization of the Patch Parameters

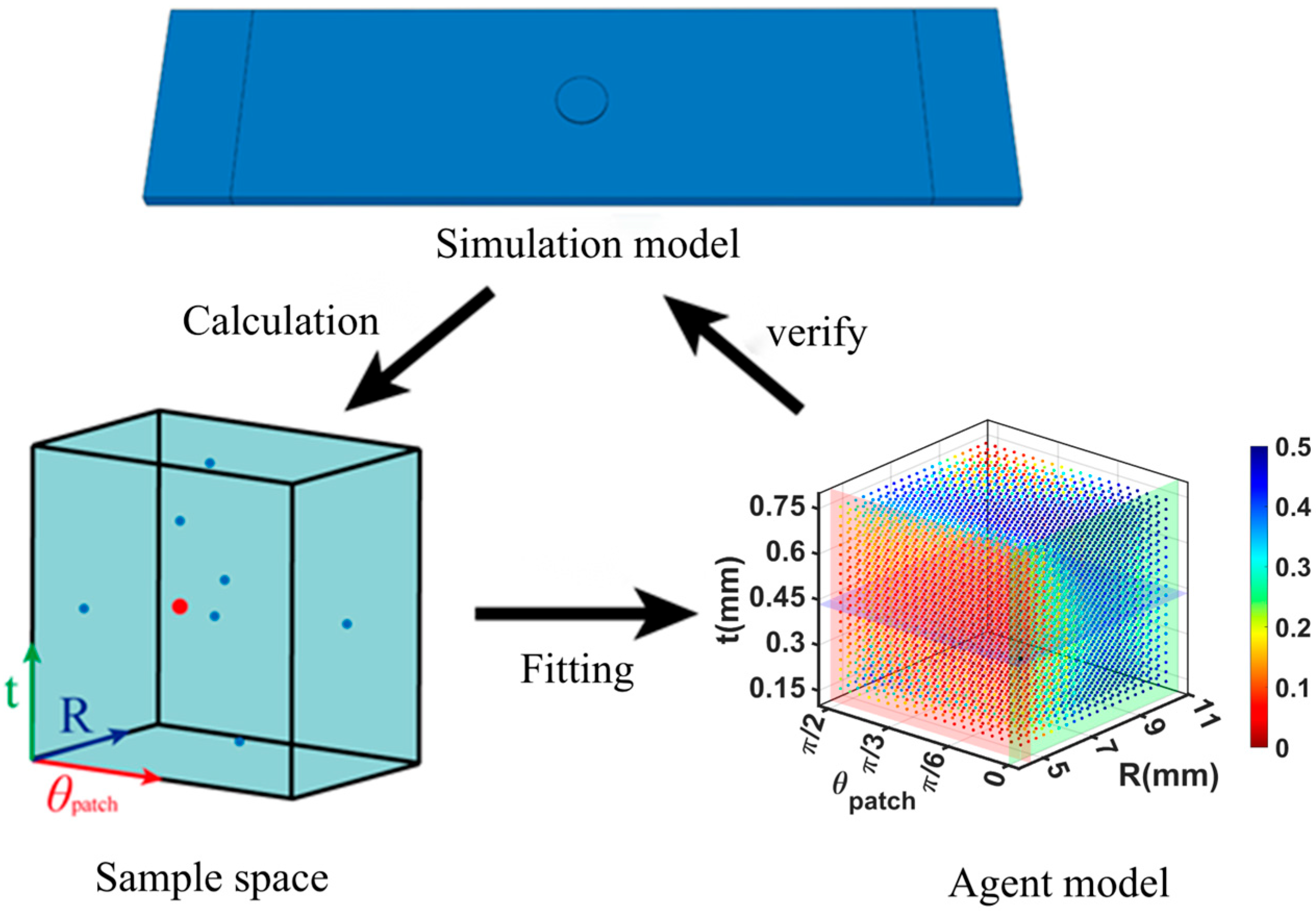

6.1. Surrogate Model Optimization Based on the Diffuse Approximation Method

- A series of sample points are selected using the Latin hypercube sampling design.

- Results are obtained for each sample point through a finite-element simulation.

- The sample space is constructed using quadratic fitting on the basis of the sample point results.

- The optimization results are validated.

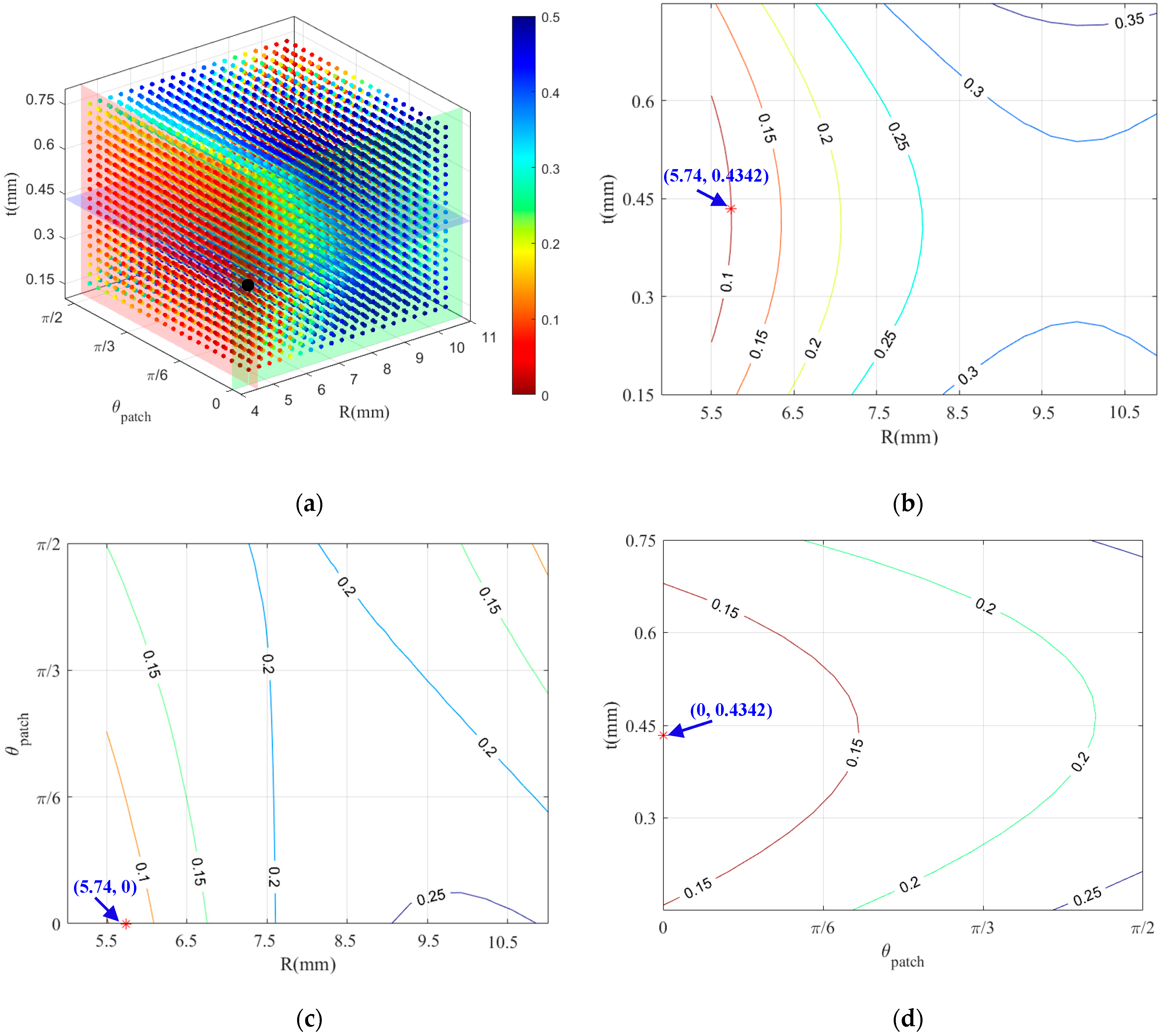

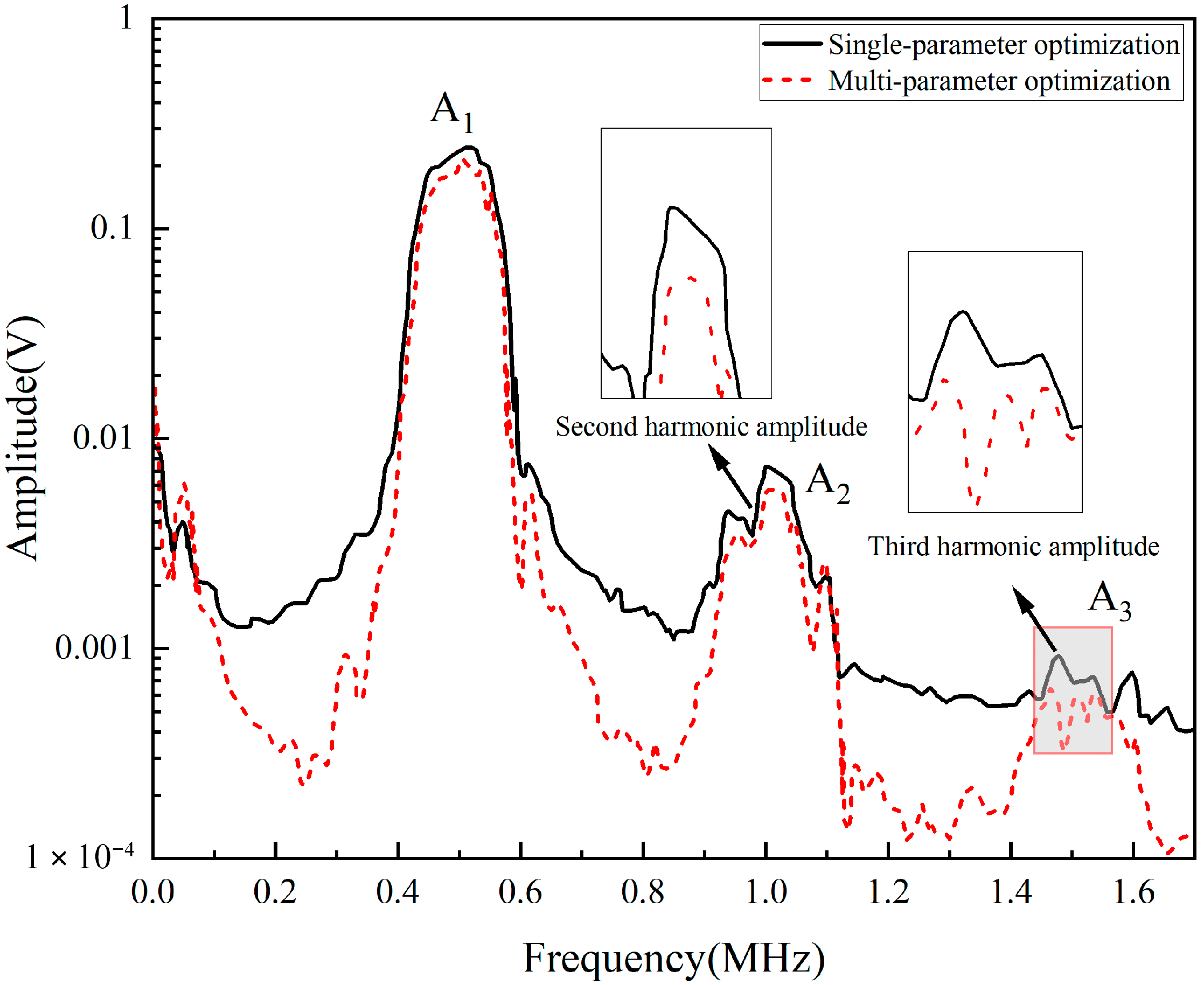

6.2. Analysis of the Optimization Results

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Takamura, M.; Isozaki, M.; Takeda, S.; Koyanagi, J. Numerical Analysis on Optimal Adhesive Thickness in CFRP Single-Lap Joints Considering Material Properties. Materials 2025, 18, 2423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šofer, M.; Cienciala, J.; Fusek, M.; Pavlíček, P.; Moravec, R. Damage analysis of composite CFRP tubes using acoustic emission monitoring and pattern recognition approach. Materials 2021, 14, 786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butenegro, J.A.; Bahrami, M.; Abenojar, J.; Martínez, M.Á. Recent progress in carbon fiber reinforced polymers recycling: A review of recycling methods and reuse of carbon fibers. Materials 2021, 14, 6401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Huo, S.; Chevali, V.; Hall, W.; Offringa, A.; Song, P.; Wang, H. Carbon Fiber Reinforced Thermoplastics: From Materials to Manufacturing and Applications. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2418709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Li, C.; Tie, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Duan, Y. Energy absorption characteristics of origami-inspired honeycomb sandwich structures under low-velocity impact loading. Mater. Des. 2021, 207, 109837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Qi, J.; Tie, Y.; Zou, T.; Duan, Y. Research on the energy absorption properties of origami-based honeycombs. Thin-Walled Struct. 2023, 184, 110520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliskan, U.; Ekici, R.; Yildiz Bayazit, A.; Apalak, M.K. Numerical model for composite patch repair of notched aluminum plates under impact loading. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part L J. Mater. Des. Appl. 2021, 235, 958–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Z.; Liu, J.; Brooks, R.A.; Crocker, J.; Joesbury, A.; Harper, L.; Blackman, B.; Kinloch, A.; Dear, J. The effectiveness of patch repairs to restore the impact properties of carbon-fibre reinforced-plastic composites. Eng. Fract. Mech. 2022, 270, 108570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitanga, M.Y.; Cioffi, M.O.H.; Voorwald, H.J.; Wang, C.H. Reducing repair dimension with variable scarf angles. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2021, 104, 102752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandyala, A.R.; Darpe, A.K.; Singh, S.P. Damage severity assessment in composite structures using multi-frequency lamb waves. Struct. Health Monit. 2022, 21, 2834–2850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, J.C.P.; Ng, C.T. Debonding detection at adhesive joints using nonlinear Lamb waves mixing. NDT E Int. 2022, 125, 102552. [Google Scholar]

- Sampath, S.; Sohn, H. Non-contact microcrack detection via nonlinear Lamb wave mixing and laser line arrays. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2023, 237, 107769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soleimanpour, R.; Soleimani, S.M. Scattering analysis of linear and nonlinear symmetric Lamb wave at cracks in plates. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2022, 37, 439–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, Y.; Li, C. Impact damage assessment in orthotropic CFRP laminates using nonlinear Lamb wave: Experimental and numerical investigations. Compos. Struct. 2020, 236, 111869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Li, C.; Tie, Y.; Duan, Y. Impact damage detection in patch-repaired CFRP laminates using nonlinear lamb waves. Sensors 2020, 21, 219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Pi, X.; Tie, Y.; Li, C. Study on impact resistance and parameter optimization of patch-repaired plain woven composite based on multi-scale analysis. Polym. Compos. 2023, 44, 5087–5103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tie, Y.; Hou, Y.; Li, C.; Meng, L.; Sapanathan, T.; Rachik, M. Optimization for maximizing the impact-resistance of patch repaired CFRP laminates using a surrogate-based model. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2020, 172, 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhao, Q.; Yuan, J.; Hou, Y.; Tie, Y. Simulation and experiment on the effect of patch shape on adhesive repair of composite structures. J. Compos. Mater. 2019, 53, 4125–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, K.; Lal, A.; Sutaria, B.M. Experimental investigation of repair of plate with edge and center crack by surface bounded composite patch. Int. J. Steel Struct. 2023, 23, 534–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, B.; Lenwari, A. Optimization of fiber-reinforced polymer patches for repairing fatigue cracks in steel plates using a genetic algorithm. J. Compos. Constr. 2020, 24, 04020006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Tu, X.; Lu, J.; Li, F. Dispersion curve analysis method for Lamb wave mode separation. Struct. Health Monit. 2020, 19, 1590–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, Y. Dispersion compensation method for lamb waves based on measured wavenumber. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 6704642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silitonga, D.J.; Declercq, N.F.; Walaszek, H.; Vu, Q.A.; Saidoun, A.; Samet, N.; Thabourey, J. A comprehensive study of non-destructive localization of structural features in metal plates using single and multimodal Lamb wave excitations. Acta Acust. 2024, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, S.; Cheng, L. Mode-mixing-induced second harmonic A0 mode Lamb wave for local incipient damage inspection. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 055020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Jiang, M.; Li, W.; Luo, Y.; Sui, Q.; Jia, L. Early fatigue damage evaluation based on nonlinear Lamb wave third-harmonic phase velocity matching. Int. J. Fatigue 2023, 167, 107288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.Y.; Jia, L.; Zhang, S.Z.; Li, X.B.; Wang, M. Second-order perturbation solution and analysis of nonlinear surface waves. Acta Phys. Sin. 2022, 71, 164301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Tie, Y.; Duan, Y.; Li, C. Optimization of nonlinear Lamb wave detection system parameters in CFRP laminates. Materials 2021, 14, 3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashi, Z. Failure criteria for unidirectional fiber composite. J. Appl. Mech. 1980, 47, 3292334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.; Tie, Y.; Duan, Y.C.; Li, C.; Chen, D. Impact damage assessment in patch-repaired CFRP laminates using the nonlinear Lamb wave-mixing technique. Polym. Compos. 2022, 43, 8152–8169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panella, F.W.; Pirinu, A. Fatigue and damage analysis on aeronautical CFRP elements under tension and bending loads: Two cases of study. Int. J. Fatigue 2021, 152, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, S.; Xiao, H.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Deng, M.; Kundu, T. Microcrack localization using nonlinear Lamb waves and cross-shaped sensor clusters. Ultrasonics 2022, 124, 106770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM D3039/D3039M—17; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Polymer Matrix Composite Materials. American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2014.

- Liu, N.; Cheng, S.; Fan, J.; Zhu, Y.; Yang, N.; Pan, Y. Simulation and experimentation of nonlinear Rayleigh wave inspection of fatigue surface microcracks. Ultrasonics 2025, 146, 107500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sass, J.; Westphal, D.; Wunderlich, R. Diffuse Approximations for periodically arriving expert opinions in a financial market with Gaussian drift. Stoch. Models 2023, 39, 323–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Zou, S.; Zhou, W.; Huang, Y.; Shao, L.; Yuan, J.; Gou, X.; Jin, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; et al. Clinically applicable histopathological diagnosis system for gastric cancer detection using deep learning. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, H.; Wu, J.; Dahal, S.; Joo, T.; Garg, N. Automated estimation of cementitious sorptivity via computer vision. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| T300/7901 CFRP Laminates | LJM-170 Adhesive Films | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Young’s modulus, E11/GPa | 125.90 | Tensile stiffness, Knn/(N·mm−3) | 105 |

| Young’s modulus, E22 = E33/GPa | 11.30 | Shear stiffness, Kss = Ktt/(N·mm−3) | 105 |

| Shear modulus, G12 = G13/GPa | 5.43 | Tensile strength, /MPa | 85 |

| Shear modulus, G23/GPa | 3.98 | Shear strength, /MPa | 146 |

| Poisson’s ratio, ν12 = ν13 | 0.30 | Toughness in tension, /(kJ·m−2) | 0.52 |

| Poisson’s ratio, ν23 | 0.42 | Toughness in shear, /(kJ·m−2) | 1.02 |

| Shear strength, S/MPa | 120 | ||

| Density, ρ/(kg·m−3) | 1800 | ||

| Tensile Displacement/mm | Experimental Load/kN | Simulated Load/kN | Relative Error/% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 28.31 | 27.29 | 3.60 |

| 1 | 55.23 | 54.36 | 1.58 |

| 1.5 | 80.68 | 79.69 | 1.23 |

| 2 | 99.74 | 97.53 | 2.22 |

| Tensile Displacement/mm | Second RANP | Third RANP | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Simulation | βSecond RANP (%) | Experiment | Simulation | δThird RANP (%) | |

| 0 | 0.00548 | 0.00525 | 4.20 | 0.00223 | 0.00228 | 2.24 |

| 0.5 | 0.00717 | 0.00692 | 3.49 | 0.00248 | 0.00252 | 1.61 |

| 1 | 0.00809 | 0.00860 | 6.30 | 0.00269 | 0.00287 | 6.69 |

| 1.5 | 0.00935 | 0.00967 | 3.42 | 0.00306 | 0.00326 | 6.54 |

| 2 | 0.01362 | 0.01429 | 4.92 | 0.00488 | 0.00505 | 3.48 |

| Run | R/mm | t/mm | θ/° | Numerical Value | Response Value | Relative Errors (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Second RANP | Third RANP | Second RANP | Third RANP | βSecond RANP | δThird RANP | ||||

| 1 | 6.07 | 0.27 | 4.86 | 0.0639 | 0.1162 | 0.0665 | 0.11561 | 4.10 | 0.51 |

| 2 | 5.14 | 0.69 | 16.17 | 0.0415 | 0.00742 | 0.0388 | 0.00801 | 6.46 | 7.96 |

| 3 | 8.52 | 0.46 | 70.35 | 0.0672 | 0.02551 | 0.0673 | 0.02550 | 0.15 | 0.03 |

| 4 | 4.63 | 0.16 | 51.67 | 0.0468 | 0.02594 | 0.0457 | 0.02618 | 2.29 | 0.92 |

| 5 | 6.36 | 0.51 | 76.86 | 0.0909 | 0.04004 | 0.0910 | 0.04003 | 0.04 | 0.02 |

| 6 | 8.17 | 0.74 | 65.38 | 0.1167 | 0.03257 | 0.1142 | 0.03312 | 2.14 | 1.69 |

| 7 | 10.17 | 0.22 | 38.31 | 0.0541 | 0.01161 | 0.0573 | 0.01089 | 5.91 | 6.16 |

| 8 | 8.96 | 0.4 | 25.68 | 0.1107 | 0.04426 | 0.1088 | 0.04687 | 1.72 | 5.91 |

| 9 | 6.73 | 0.61 | 43.07 | 0.1020 | 0.02692 | 0.1091 | 0.02536 | 6.96 | 5.81 |

| 10 | 7.35 | 0.32 | 88.08 | 0.0994 | 0.04829 | 0.0998 | 0.04819 | 0.36 | 0.21 |

| 11 | 9.41 | 0.56 | 21.83 | 0.1069 | 0.03272 | 0.1123 | 0.03151 | 5.05 | 3.69 |

| Project | R/mm | t/mm | θ/° | Quadratic Nonlinear Coefficient | Cubic Nonlinear Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-parameter optimization | 6 | 0.45 | 0 | 0.1477 | 0.07977 |

| Multi-parameter optimization | 5.74 | 0.4342 | 0 | 0.1082 | 0.05184 |

| Reduction rate (%) | — | — | — | 26.74 | 35.01 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yin, Z.; Wei, H.; Ma, Z.; Man, R.; Yu, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, H. Optimizing the Tensile Performance of Repaired CFRP Laminates with Different Patch Parameters Using a Surrogate-Based Model. Materials 2025, 18, 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225099

Yin Z, Wei H, Ma Z, Man R, Yu J, Wang X, Liu H. Optimizing the Tensile Performance of Repaired CFRP Laminates with Different Patch Parameters Using a Surrogate-Based Model. Materials. 2025; 18(22):5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225099

Chicago/Turabian StyleYin, Zhenhua, Haoying Wei, Zhenyu Ma, Ruidong Man, Jing Yu, Xiaoqiang Wang, and Hui Liu. 2025. "Optimizing the Tensile Performance of Repaired CFRP Laminates with Different Patch Parameters Using a Surrogate-Based Model" Materials 18, no. 22: 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225099

APA StyleYin, Z., Wei, H., Ma, Z., Man, R., Yu, J., Wang, X., & Liu, H. (2025). Optimizing the Tensile Performance of Repaired CFRP Laminates with Different Patch Parameters Using a Surrogate-Based Model. Materials, 18(22), 5099. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18225099