1. Introduction

Concrete, as a key material in modern construction engineering, exhibits compressive strength that serves as a critical indicator determining structural safety and durability [

1]. Traditional strength prediction methods predominantly rely on empirical formulas [

2,

3,

4] or laboratory tests of concrete specimens [

5,

6,

7]. The former is limited by simplified mathematical assumptions that fail to capture the material’s nonlinear characteristics, while the latter suffers from lengthy cycles, high costs, and an inability to provide real-time guidance during construction. With the rapid advancement of machine learning techniques, data-driven predictive models for strength have gradually become a focus of research. These models can capture complex feature relationships from historical mix proportion data, significantly enhancing prediction efficiency [

8,

9,

10,

11].

In recent years, ensemble learning algorithms (such as Gradient Boosting Trees and Random Forest) and neural networks have demonstrated excellent performance in applications within the construction engineering field. Gradient Boosting Trees (GBT), as a representative ensemble learning algorithm, iteratively constructs a sequence of weak learners to optimize the model [

12,

13,

14]. This approach offers advantages in efficiently handling structured data, memory optimization, and processing categorical features. Random Forest (RF) enhances model generalization by constructing multiple decision trees and aggregating their results [

15]. It strengthens model robustness through twofold randomization (bootstrap sampling and feature subset selection) and supports feature importance evaluation. Backpropagation Neural Networks (BPNN) achieve complex function approximation via nonlinear combinations of multi-layer artificial neurons, operating through two core phases (forward propagation and error backpropagation) where continuous updates to neuronal weights and thresholds reduce model fitting errors within target ranges to improve prediction accuracy [

16,

17].

Existing research has extensively validated the effectiveness of various algorithms in predicting concrete strength: Elshaarawy et al. [

18] employed both ensemble and non-ensemble machine learning models for concrete strength prediction, demonstrating that CatBoost delivers superior predictive performance with significantly higher accuracy than traditional regression methods. Sun et al. [

19] and Wu et al. [

20] effectively utilized Backpropagation Neural Networks to predict concrete compressive strength. Meddage et al. [

21] and Abdellatief et al. [

22,

23] accurately predicted concrete compressive strength using gradient boosting algorithms (XGBoost). Kashem et al. [

24] introduced Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Random Forest (RF), and hybrid machine learning (HML) approaches to predict the compressive strength of rice husk ash concrete, revealing that the hybrid XGBoost-LGBM model exhibits outstanding predictive and generalization capabilities. Additionally, Alyami et al. [

25] applied seven machine learning algorithms to predict the compressive strength of fiber-reinforced concrete (3DP-FRC), finding that the Gene Expression Programming (GEP) model achieved higher accuracy in the validation set. Sami et al. [

26] collected 8 sets of high-strength concrete data samples from literature to develop predictive models for tensile and compressive strength, proving that the Gaussian Process Regression (GPR) model delivers greater accuracy in predicting both tensile and compressive strength of concrete. It is noteworthy that Abbas et al. [

27] utilized a deep autoencoder for damage identification in underground metro shield tunnels, demonstrating the potential of deep learning in structural health monitoring. Concurrently, Kumar et al. [

28] systematically reviewed research trends and future directions of machine and deep learning in concrete strength prediction, providing theoretical support for this study.

While machine learning algorithms demonstrate significant advantages in concrete strength prediction, they face challenges in quantifying feature contributions and interaction effects, resulting in a lack of theoretical guidance for concrete mix proportion optimization; particularly when optimizing mix designs based on prediction outcomes, model interpretability becomes a critical requirement. SHAP, LIME, and other interpretability methods quantify the marginal contributions of features to prediction outcomes, enabling the revelation of model decision logic at both global and local levels. While significant progress has been achieved in applying these interpretability approaches in medical and financial domains [

29,

30,

31], their implementation in civil engineering materials remains exploratory. Zhu et al. [

32] integrated SHAP with an XGBoost model to analyze feature weights affecting the shear capacity of fiber-reinforced polymer–concrete interfaces, identifying fiber-reinforced polymer content as the most critical factor. Frie et al. [

33] employed explainable machine learning to explore fatigue-influencing factors in materials. Yang et al. [

34] developed ANN- and RF-based mortar design and optimization models, coupling them with interpretability analysis to reveal that cement content and apparent density of natural coarse aggregates exhibit the greatest impact on compressive strength. Jia et al. [

35] leveraged SHAP to interpret LightGBM predictions, establishing an interpretable concrete mix proportion strength prediction model.

In the simulation of concrete mechanical behavior, numerical models widely employ discrete crack approaches and smeared damage approaches. Discrete crack approaches explicitly represent crack initiation and propagation, accurately capturing localization and softening behavior with high crack-path fidelity. For instance, De Maio et al. [

36] proposed an adaptive cohesive interface model combined with a moving mesh technique to simulate arbitrary crack growth in heterogeneous materials. Smeared damage approaches (e.g., smeared cracks, continuum damage mechanics with internal variables) distribute cracking over the continuum; they are efficient for large-scale structural analyses but require regularization for mesh objectivity and rely on well-calibrated softening laws. Fan et al. [

37] investigated the evolution of fatigue damage in concrete under uniaxial compression using sensors and X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans, providing an experimental basis for damage models.

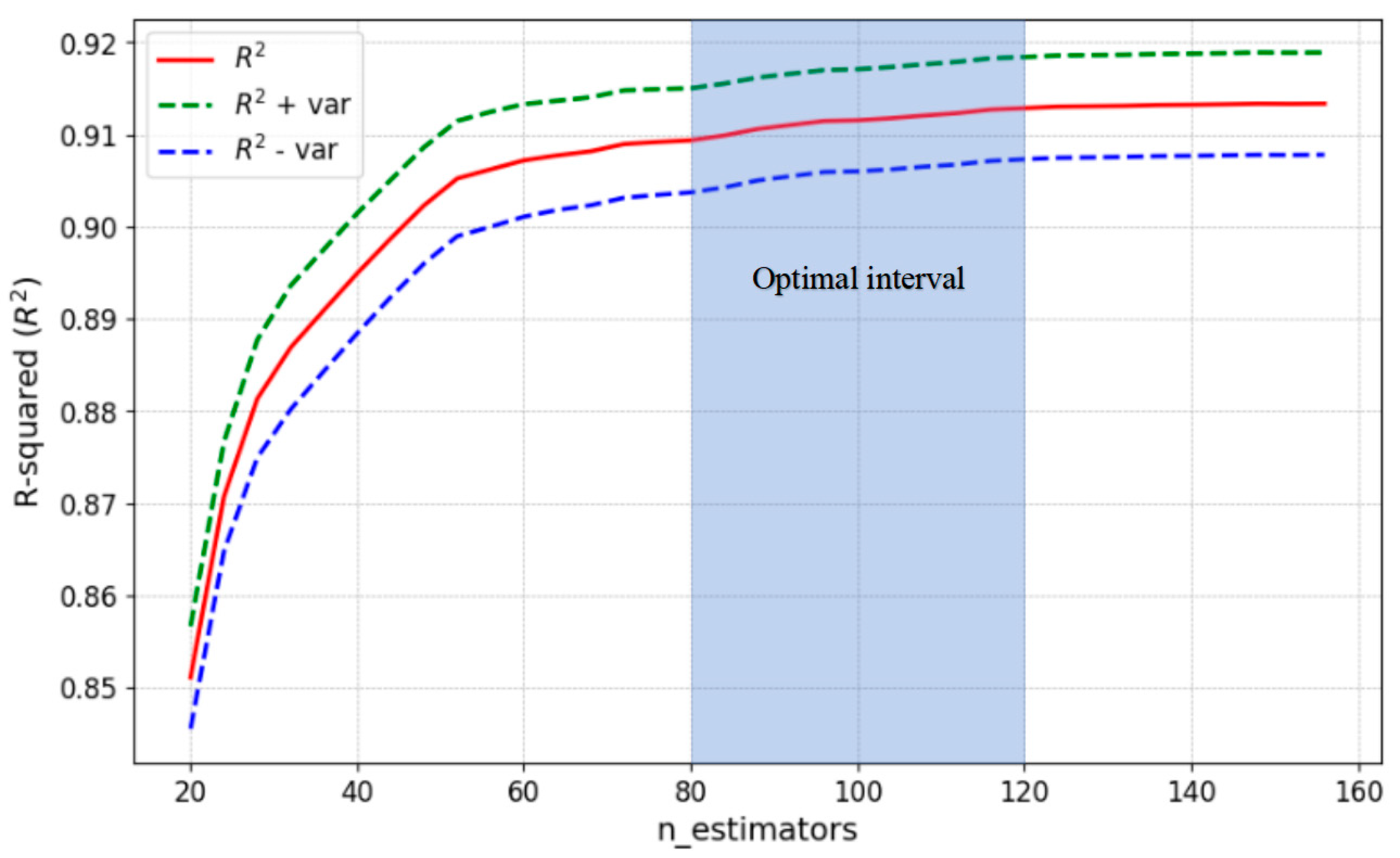

Furthermore, hyperparameter optimization serves as a critical step for enhancing model performance, effectively improving generalization capabilities. Traditional grid search and random search methods suffer from inefficiency, while Bayesian optimization, genetic algorithms, and particle swarm optimization offer novel approaches for rapid tuning of complex models. Tran et al. [

38] integrated Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) with Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Support Vector Regression (SVR), and Gradient Boosting (GB) to optimize hyperparameters for predicting the compressive strength of recycled concrete; this approach features simple parameter settings and fast convergence but is prone to local optima. To address this limitation, Zhang et al. [

39] proposed an improved PSO where the inertia weight ω is dynamically adjusted with iterations to enhance particle swarm randomness and diversity, successfully applying it to mechanical parameter inversion analysis in dam engineering. Genetic algorithms (GA), grounded in principles of natural selection and genetic variation, enable global exploration of parameter spaces through crossover and mutation operations. Lim et al. [

40] employed GA to optimize high-performance concrete mix design, while Ma et al. [

41] developed four GA-machine learning models for predicting the shear performance of concrete beams, outperforming formula-based models in current international design codes. Beyond PSO and GA, Bayesian optimization exhibits unique advantages for hyperparameter tuning in concrete strength models: Zhang et al. [

42] combined Gradient Boosted Decision Trees (GBDT) with Bayesian optimization to efficiently identify optimal hyperparameter combinations for recycled aggregate concrete tree models. Ragaa et al. [

43] enhanced the generalization capability of neural networks predicting chloride and sulfate ingress into concrete using Bayesian optimization. Liu et al. [

44] constructed precise concrete strength prediction models by leveraging Bayesian optimization for optimal algorithm selection and hyperparameter configuration.

Drawing from the existing literature, it is evident that while machine learning demonstrates significant potential for predicting concrete compressive strength, several critical gaps remain unaddressed. Firstly, although various ensemble algorithms have been applied, a systematic comparison of the latest Gradient Boosting Tree variants (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost) against established methods like Random Forest and BPNN, using a controlled and consistent experimental dataset, is still lacking. This makes it difficult to identify the most robust algorithm for concrete mix-proportion problems. Secondly, the optimization process for these models often relies on traditional methods, leaving the full potential of efficient, advanced techniques like Bayesian optimization for this specific task underexplored. And the prevalent “black-box” nature of these high-performance models poses a major barrier to their practical adoption in engineering design.

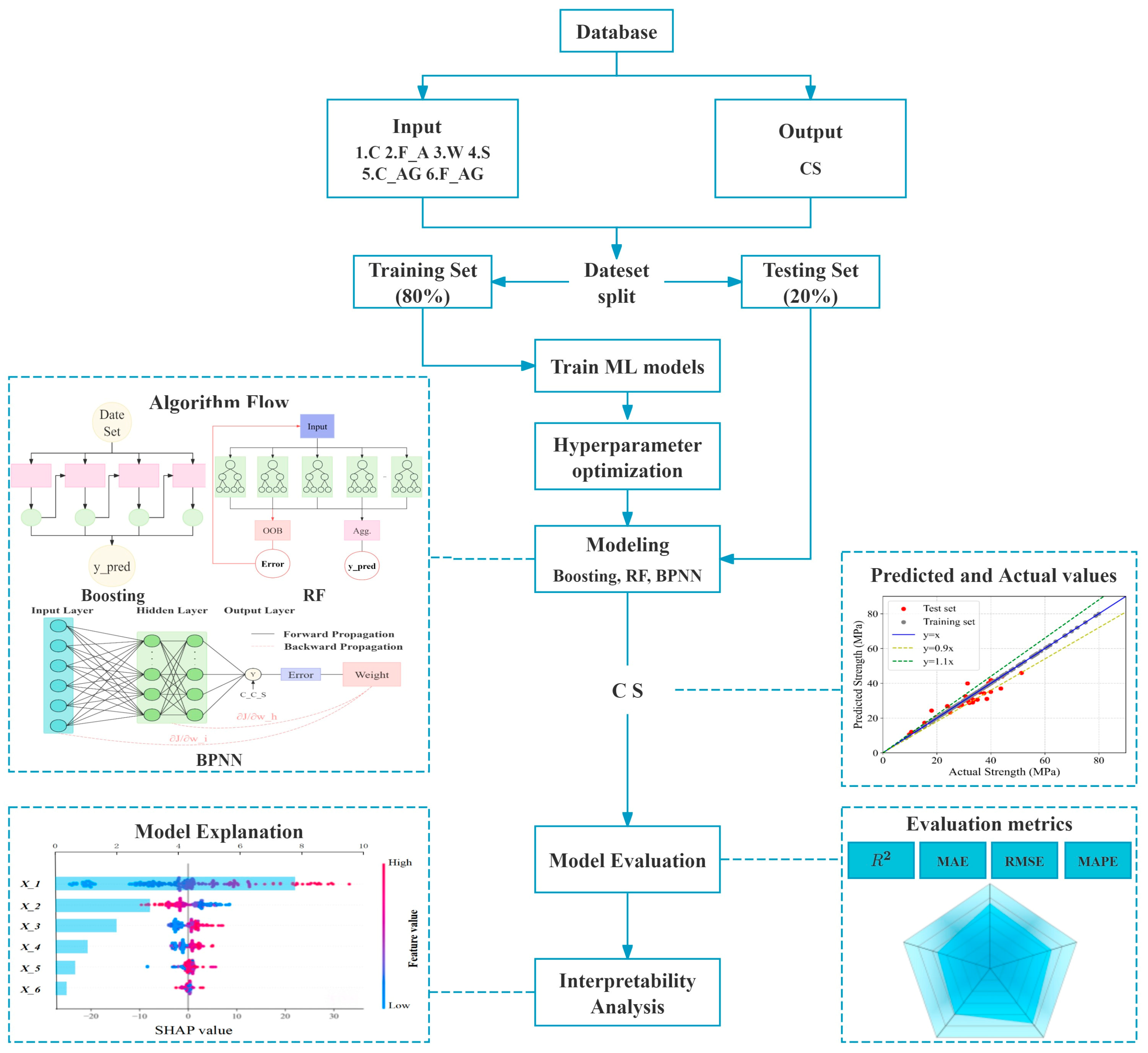

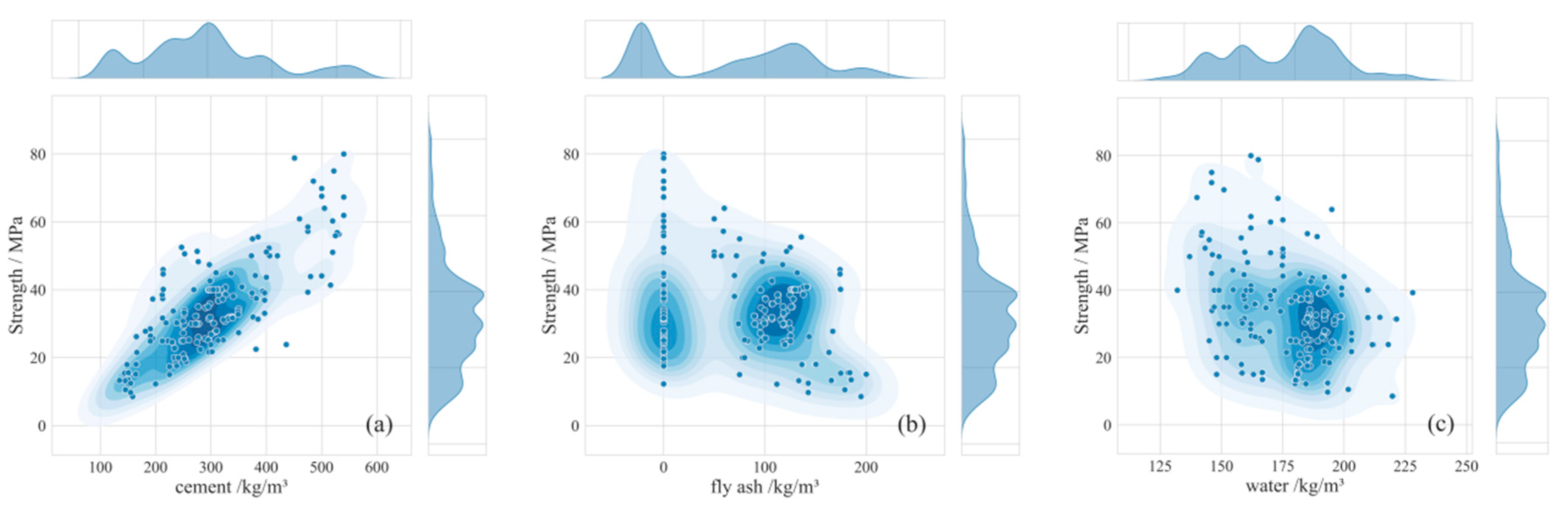

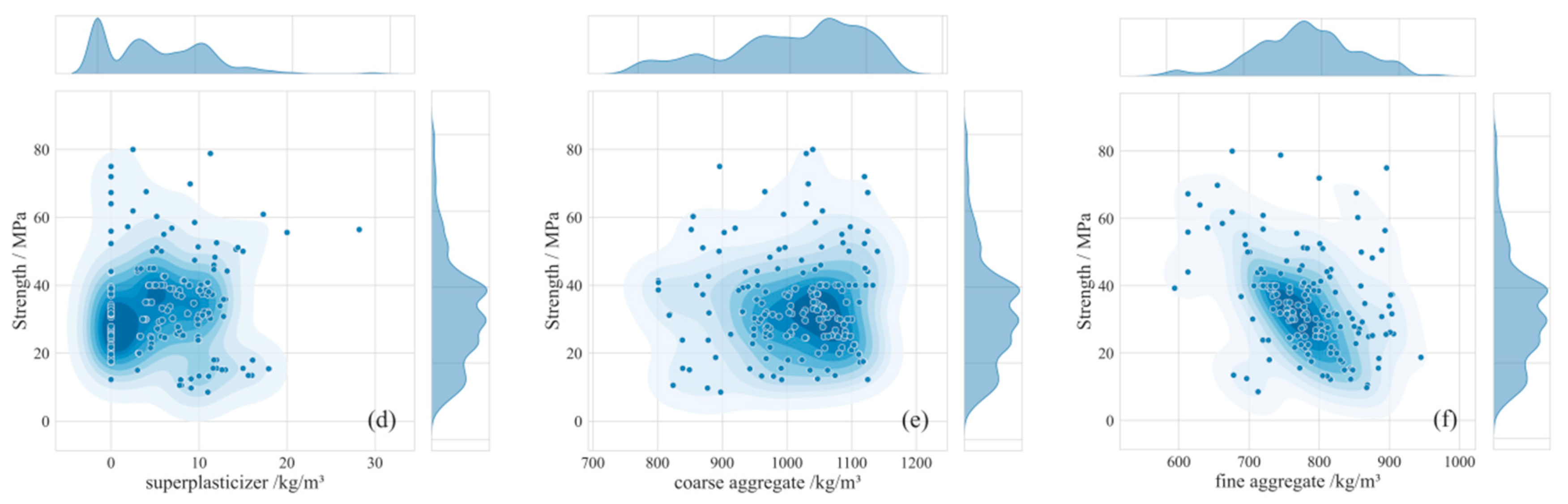

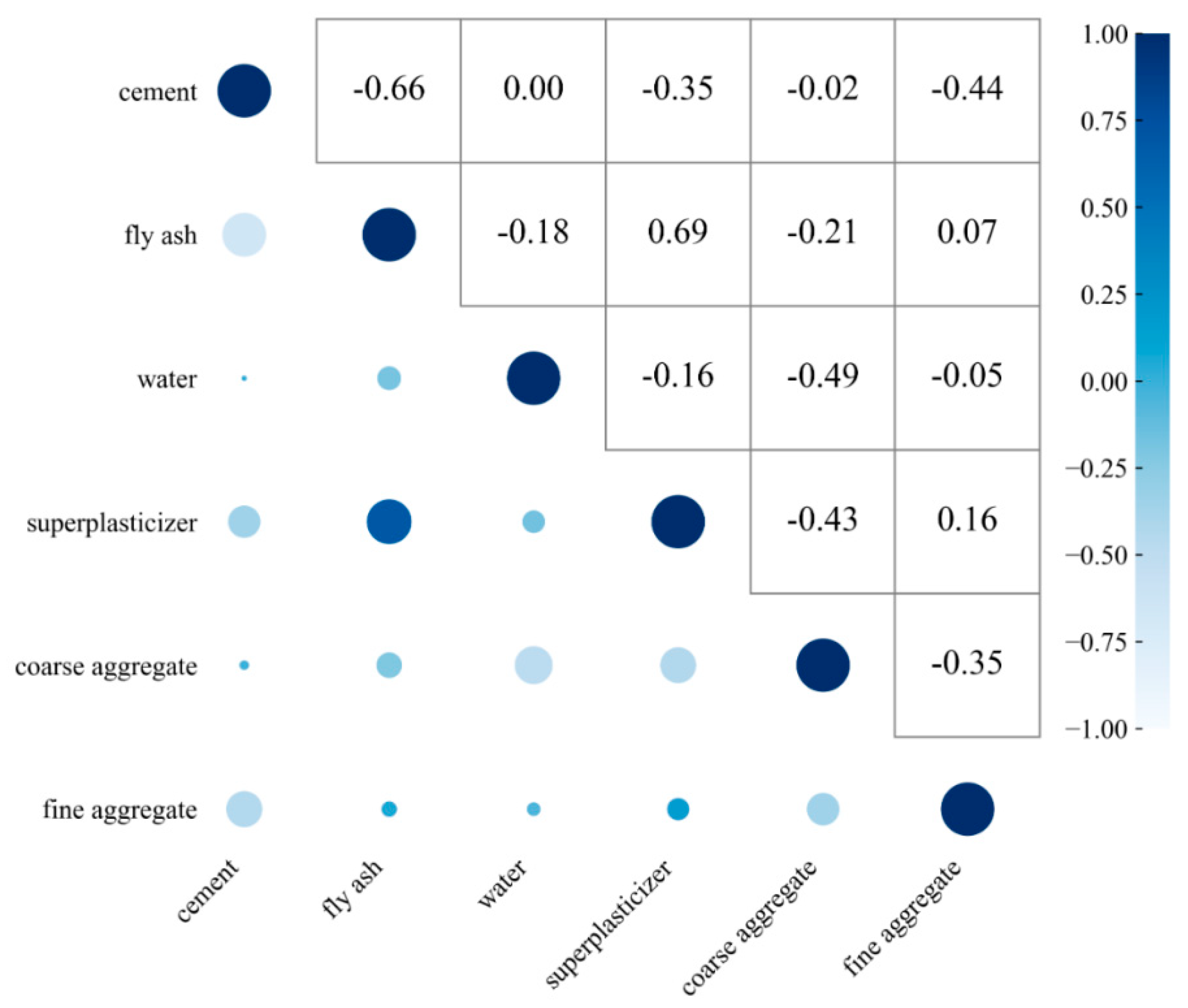

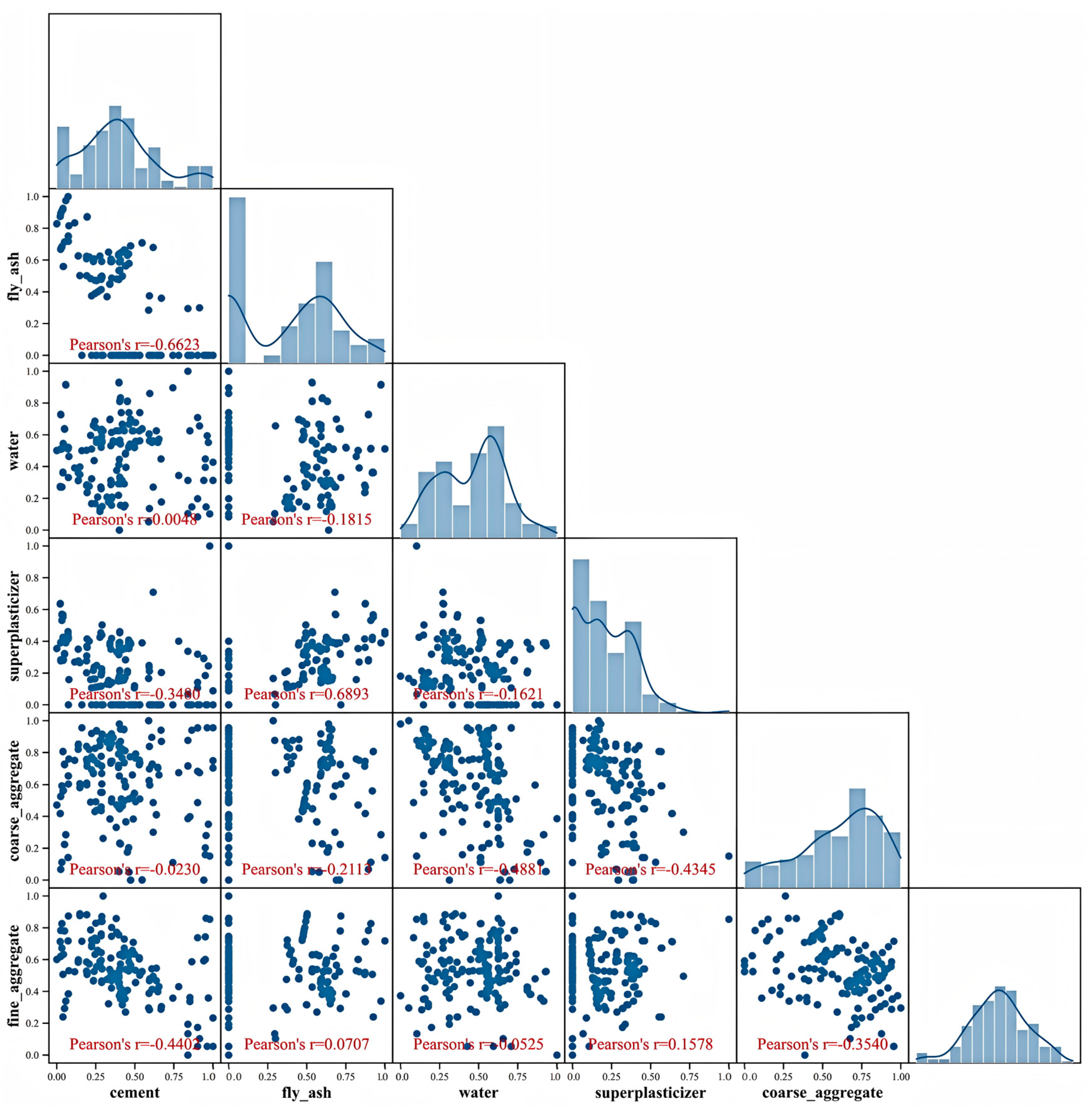

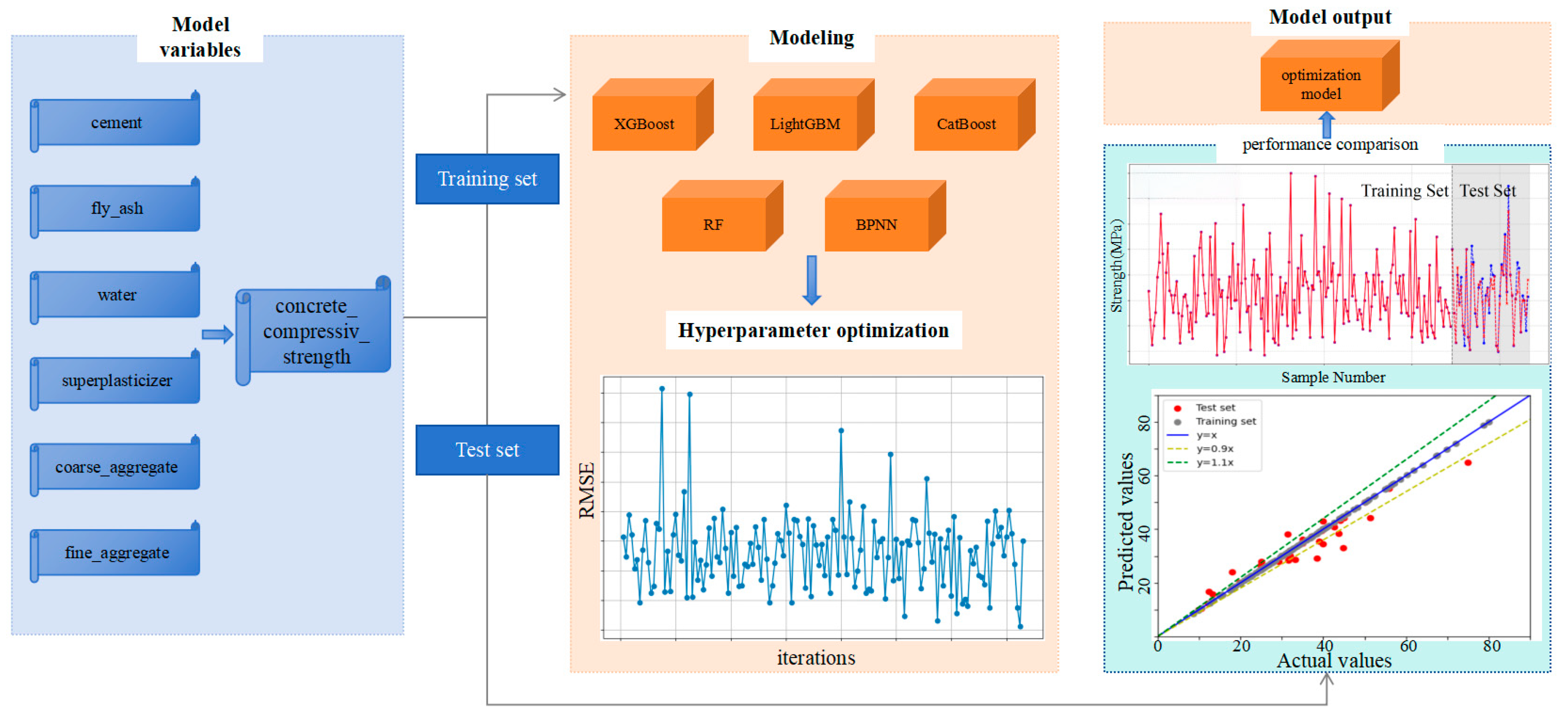

To address these issues, this study targets the prediction of 28-day compressive strength of concrete by adopting a machine learning framework integrating Bayesian optimization and interpretability analysis. Using 223 sets of mix proportion data obtained from field experiments, we systematically compare the predictive performance of five models: Gradient Boosting Trees (XGBoost, LightGBM, CatBoost), Random Forest (RF), and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN). Bayesian optimization is employed for efficient hyperparameter search to obtain optimal model parameters. Furthermore, SHAP methodology is introduced to quantitatively analyze the global contributions and local interaction effects of mix proportion parameters—including cement, fly ash, and water content—on compressive strength, revealing potential pathways for material proportion optimization (as illustrated in

Figure 1). This research aims to overcome the dual challenges of precision in concrete mix design and model interpretability, providing an intelligent tool with both predictive power and decision transparency for engineering practice, ultimately driving the transformation of concrete material design from experience-driven to data-driven paradigms.

3. Results and Analysis

3.1. Comparison and Evaluation of Algorithm Model

All five machine learning models discussed in this section were trained using the optimal hyperparameters identified in

Section 2.4.

Figure 9 presents box plots of the four core evaluation metrics, while

Table 2 provides point estimates of these metrics along with individual metric scores and comprehensive rankings. This approach not only reveals the stability of model performance across repeated validations but also quantifies the absolute performance of each model.

As an effective statistical visualization tool, the box plots illustrate the distribution characteristics of each metric. In

Figure 9, the boxes represent the interquartile range (IQR), the horizontal line inside each box indicates the median, the small black square denotes the mean. Overall, CatBoost demonstrates superior performance across all metrics: its box is positioned highest in the R

2 subplot (reflecting the best data fitting ability, with a median of 0.924), and lowest in the RMSE, MAE, and MAPE subplots (indicating the smallest prediction errors, with median values of 2.97 MPa, 1.77 MPa, and 5.64%, respectively). Moreover, CatBoost exhibits the narrowest 95% confidence intervals among all models (R

2: [0.822, 0.977], RMSE: [1.707, 4.477], MAE: [1.190, 2.564], MAPE: [3.924, 7.419]), confirming its exceptional performance stability.

Table 2 summarizes the evaluation metrics for the five machine learning models. The values presented are point estimates calculated on the original full test set, not bootstrap medians. The gradient boosting tree models—CatBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM—collectively achieved R

2 values above 0.9, indicating strong data fitting performance. In contrast, Random Forest (RF) and the Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) yielded R

2 values below 0.9, reflecting relatively weaker fitting efficacy. Specifically, CatBoost attained the highest R

2 (0.9388), outperforming XGBoost (0.9304) and LightGBM (0.9133). In terms of error metrics, CatBoost also demonstrated lower RMSE (2.7131 MPa) and MAPE (5.45%) than the other two models. Although its MAE (1.9786 MPa) was slightly higher than that of XGBoost (1.8495 MPa), the difference was negligible. Therefore, CatBoost exhibits the best overall performance in terms of goodness-of-fit and error control, confirming its strong capability to accurately predict compressive strength across diverse mix proportions.

Figure 10 compares predicted versus actual concrete compressive strengths across five machine learning models using scatter plots with reference lines, where red and grey markers denote test and training sets, respectively; the blue line (y = x) represents the ideal prediction state, while yellow and green lines demarcate specific deviation ranges. Training set fit reflects prediction accuracy, whereas test set fit indicates generalization capability—analysis reveals minor deviations between predicted and actual values for most data points across all models, confirming robust predictive performance primarily attributable to Bayesian optimization tuning. Notably, Gradient Boosting Tree models (CatBoost, XGBoost, LightGBM) exhibit > 95% of data points within ±10% error bounds, whereas Random Forest (RF) and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) demonstrate 15–20% fitting errors, establishing GBDT superiority. Critically, XGBoost’s near-perfect training alignment contrasts with its test R

2 (0.9304), indicating overfitting and elevated generalization error. In contrast, CatBoost maintains uniform distribution of both training and test points within 10% error bounds, achieving superior test R

2 (0.9388) with minimal overfitting and optimized generalization.

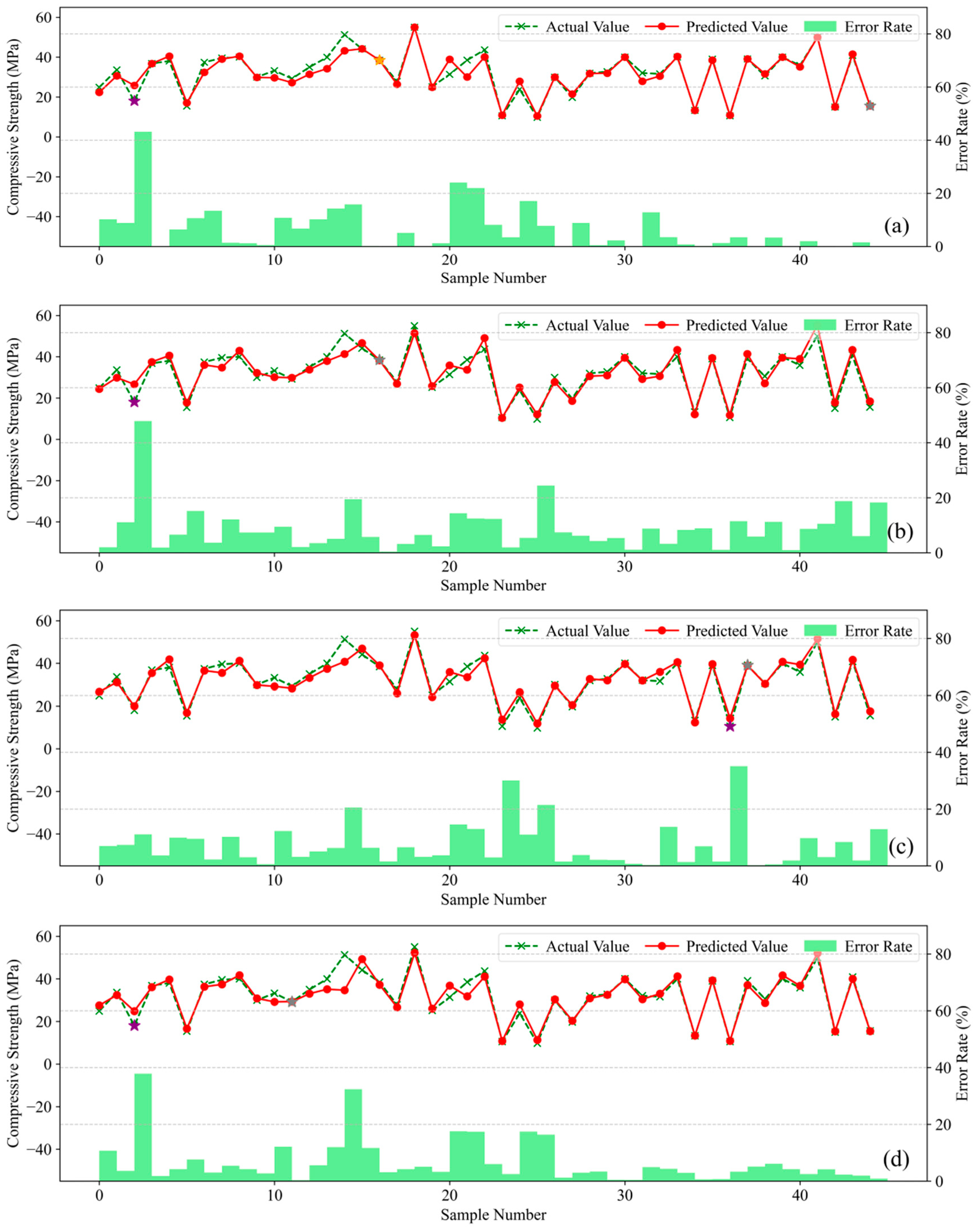

Figure 11 presents the prediction error analysis for the five machine learning models. The green polyline represents actual compressive strength values, the red polyline denotes model-predicted values, and green bars indicate the relative prediction error for each sample; comparison between the green and red polylines visually reveals prediction deviations per sample, while the error bars quantitatively illustrate the magnitude of divergence between predicted and actual values.

Analysis reveals that Gradient Boosting Tree models achieve close alignment between predicted and actual values on the training set. With only isolated exceptions exceeding 20% error, CatBoost, XGBoost, and LightGBM maintain relative errors within 10% for most samples. These models exhibit Mean Absolute Percentage Errors (MAPE) of 5.45%, 6.44%, and 8.71%, respectively. In contrast, Random Forest (RF) and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) yield higher MAPEs of 6.71% and 10.13%. Collectively, these results confirm CatBoost’s superior accuracy in predicting concrete compressive strength across diverse mix proportions.

Consequently, among the five evaluated models, CatBoost demonstrates optimal comprehensive performance with superior compatibility for this concrete mix proportion strength dataset. While XGBoost exhibits marginally inferior performance to CatBoost yet maintains competent predictive capability, whereas Random Forest (RF) and Backpropagation Neural Network (BPNN) deliver comparatively weaker overall performance.

3.2. Comparison and Evaluation of Empirical Formulas

To objectively assess the engineering applicability of the optimized CatBoost model, this study systematically compares its predictive performance with the current industry standard Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete (JGJ 55-2011) [

50]. According to JGJ 55, Equation (9) is used to calculate and predict the strength of concrete.

where

fcu,pred denotes the predicted cube compressive strength (MPa);

αa and

αb are regression coefficients (0.53 and 0.20, respectively);

fce is the actual compressive strength of cement (MPa);

C represents cement content (kg/m

3);

FA indicates mineral admixture content (kg/m

3); and

W is water content (kg/m

3).

Ten sets of validation experiments were designed, with concrete mix proportions detailed in

Table 3.

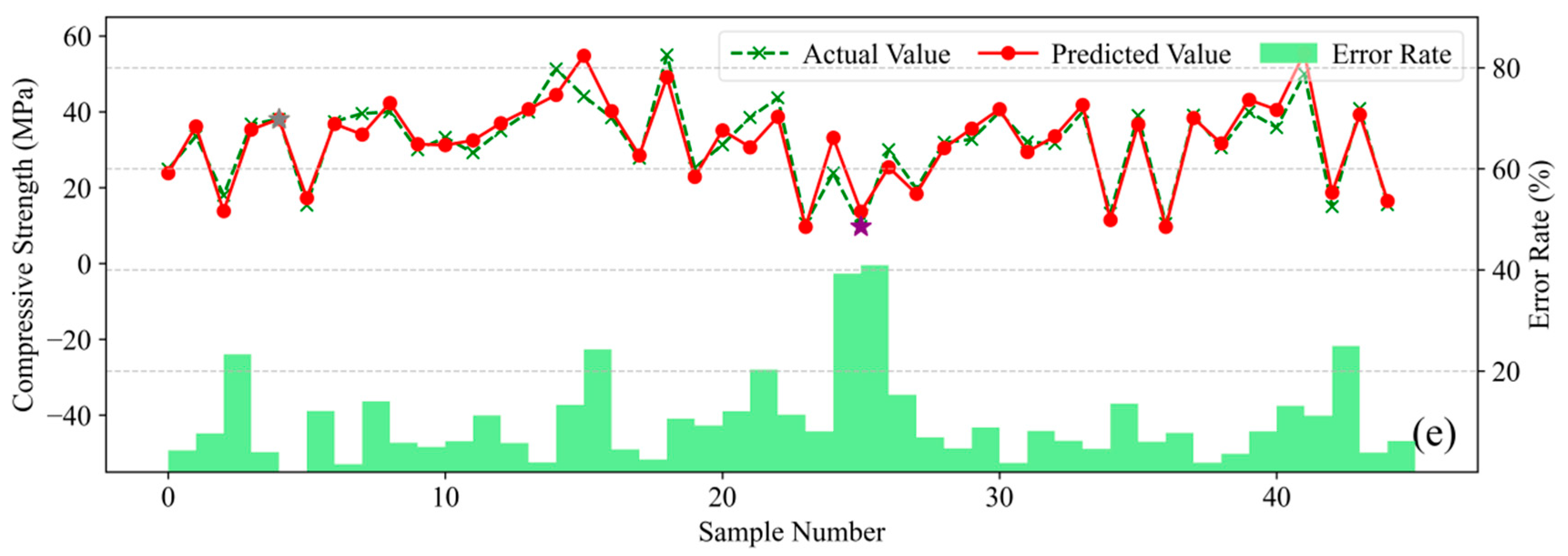

The ten sets of mix proportion parameters were input into Equation (9) and the established CatBoost prediction model, with results presented in

Figure 12. The red curve represents strength values predicted by the CatBoost model, the blue curve denotes calculated values from the empirical formula in the Design Code (Equation (9)), and the green curve indicates experimentally measured actual strength values. An accompanying bar chart displays error rates between the Design Code predictions, CatBoost predictions, and actual strength measurements.

Both empirical formula (Equation (9)) and the CatBoost model demonstrate competent concrete strength prediction, yet CatBoost achieves a lower mean absolute percentage error (MAPE = 2.94%) compared to the empirical formula (MAPE = 5.96%). Superiority of the CatBoost model is further evidenced by metrics including R2 score, MAE, and RMSE. Further analysis reveals that the core strength calculation in JGJ 55-2011 does not explicitly incorporate key parameters, such as water reducer dosage, coarse/fine aggregate quantities, or critical aggregate properties as direct variables. Instead, their influences are indirectly addressed through: (1) water reducer’s impact via water reduction rate (affecting water content), (2) aggregate effects via regression coefficients and sand ratio optimization, (3) Mandatory trial batching to derive qualified and economical mix proportions. The CatBoost model overcomes these simplifications by accurately capturing nonlinear couplings among admixtures, additives, and material properties. Thus, under the specific experimental conditions (P·O 42.5 cement, Class F Category II fly ash, graded aggregates, and retarding high-performance polycarboxylate superplasticizer), the CatBoost model marginally outperforms the empirical formula from Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete (JGJ 55-2011) in single-point strength prediction accuracy.

3.3. External Validation on UCI Dataset

To further evaluate the generalization performance of the proposed model, we conducted external validation on the Concrete Compressive Strength dataset from the UCI Machine Learning Repository. This dataset contains a total of 1030 samples, each with 8 input features (including cement, blast furnace slag, fly ash, water, superplasticizer, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate, and age) and the corresponding compressive strength value. It should be noted that the experimental dataset used in this paper only contains six features (cement, fly ash, water, superplasticizer, coarse aggregate, fine aggregate), indicating a feature discrepancy with the UCI dataset. To address this discrepancy, we adopted two evaluation strategies: Strategy A selected samples from the UCI dataset with a blast furnace slag content of 0 and an age of 28 days, obtaining a total of 175 samples. Strategy B selected 311 samples with a blast furnace slag content of 0 and an age not less than 28 days. The age of 28 days was chosen as the key age because concrete strength typically reaches over 90% of its final strength at this stage, and subsequent strength gain tends to stabilize, making age no longer a primary influencing factor. Furthermore, the larger sample size in Strategy B helps to more comprehensively test the model’s generalization capability.

The trained CatBoost model was directly applied to the aforementioned two UCI subsets without any retraining or parameter fine-tuning. The prediction performance results are summarized in

Table 4.

On the UCI subset with a higher degree of feature matching (Strategy A), the CatBoost model achieved a prediction performance of R2 = 0.9014, RMSE = 3.5827, and MAPE = 11.21%. Although slightly lower than the performance on the internal test set, potentially due to differences in material sources, curing conditions, and experimental procedures, the overall metrics remain at a high and acceptable level, indicating that the model maintains good predictive capability even outside the distribution of the training data.

For the Strategy B subset, which has a broader sample range but suffers from age feature mismatch, the model performance showed a further expected decline (R2 = 0.7480, RMSE = 6.9738, MAPE = 12.15%). This reflects the challenges faced when the key variable “Age” is missing from the model’s input features. It also indicates that the model’s prediction accuracy is affected when there are significant distributional differences between the external data and the training data. Nonetheless, the model maintained considerable predictive effectiveness in terms of R2 and error metrics and did not completely fail, further confirming its certain degree of robustness.

In summary, the external validation results on the UCI dataset demonstrate that the CatBoost model developed in this study possesses good generalization capability. Particularly on external data with good feature matching (Strategy A), the model can provide high-accuracy predictions comparable to those on the internal test set. Even in more challenging scenarios with incomplete feature matching and greater data distribution differences (Strategy B), the model can still output reference-worthy prediction results.

3.4. SHAP Interpretability Framework for Feature Importance Analysis

3.4.1. Global Interpretation and Analysis

The inherent opacity of machine learning models impedes explanatory insight into predictive outcomes, thereby compromising model trustworthiness. To resolve this limitation, we integrate the optimized CatBoost architecture with SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) interpretability framework. This synthesis quantifies interaction mechanisms between concrete mix proportion parameters (inputs) and compressive strength (output), establishing a systematic quantification paradigm for evaluating compositional influences on mechanical performance.

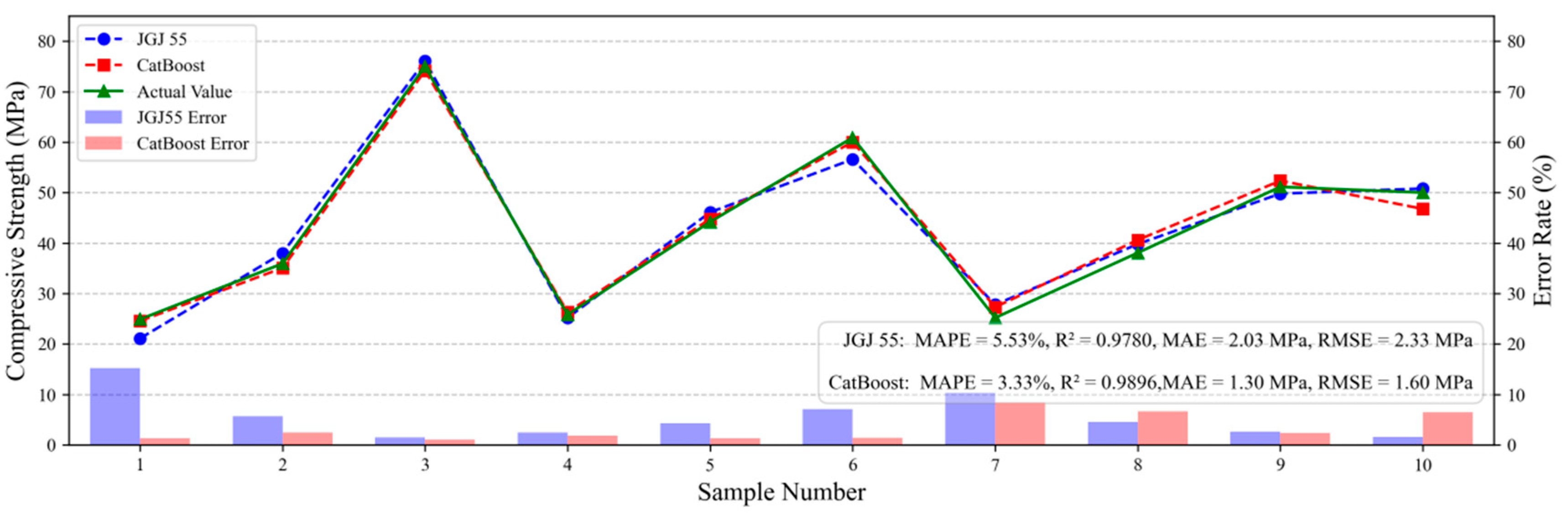

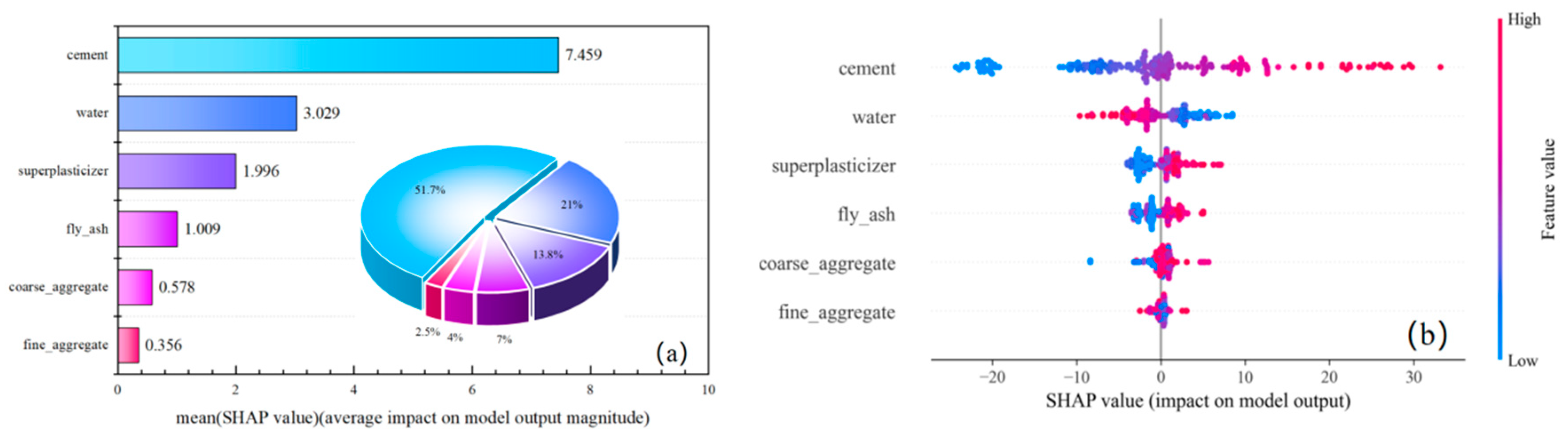

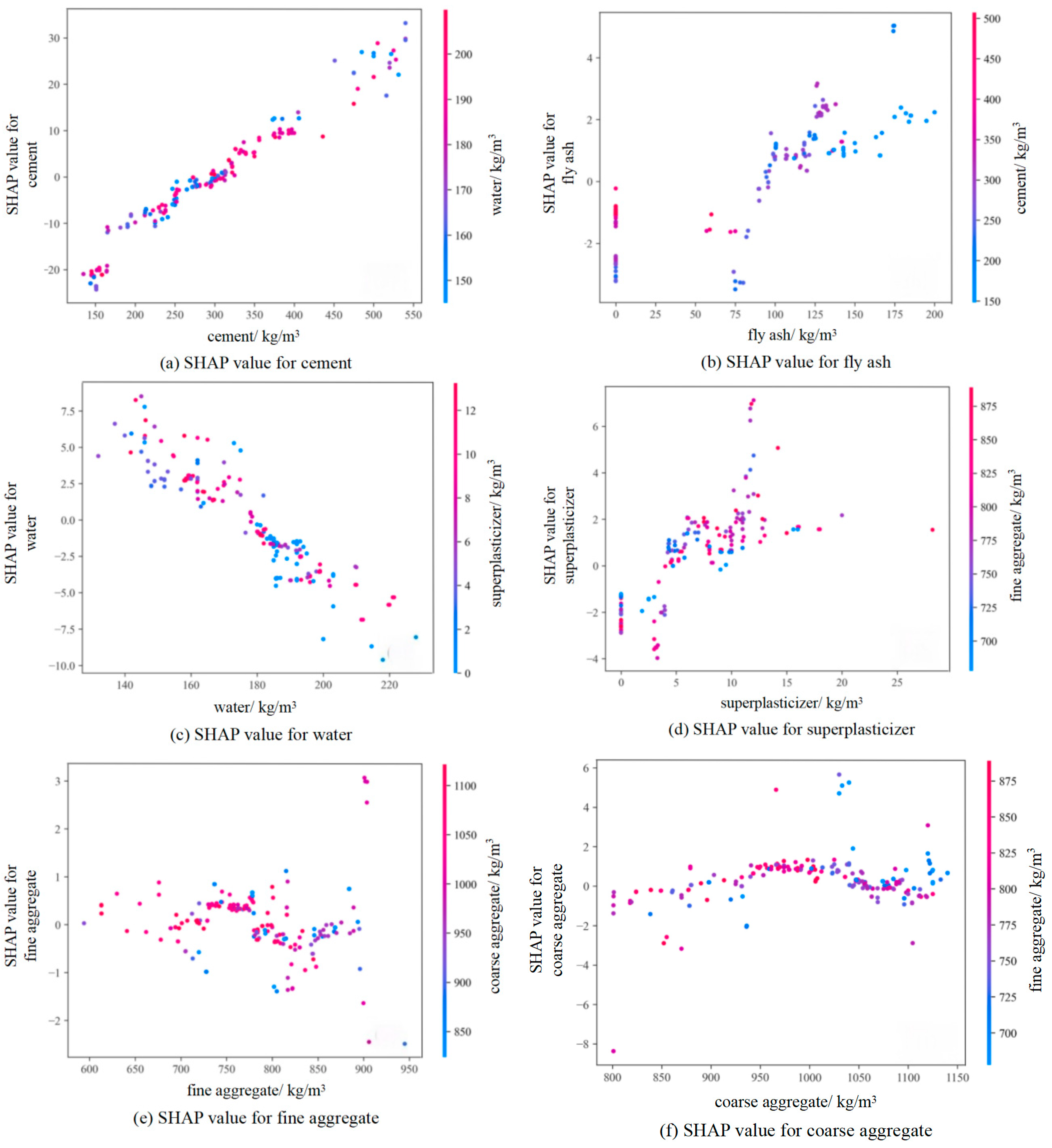

Figure 13 presents the SHAP summary plot for input features of the optimal CatBoost model, where the left panel displays global feature importance represented by mean absolute SHAP values across all samples. Cement exhibits the highest mean SHAP value (7.459), confirming its dominant influence on compressive strength predictions and establishing it as the most critical factor. The features are ranked in descending order of impact magnitude: cement > water > superplasticizer > fly ash > coarse aggregate > fine aggregate. The right panel visualizes feature effects through SHAP distributions. The horizontal axis denotes SHAP magnitude (negative values reduce output strength while positive values enhance it, with absolute magnitude indicating effect intensity); vertical ordering reflects influence hierarchy; color mapping indicates feature values (blue for low values, red for high values). Cement demonstrates complex dichotomous behavior: low values (blue) predominantly exert negative effects while high values (red) enhance strength. Superplasticizer, fly ash, and both aggregates exhibit consistent positive relationships with strength. Water displays threshold-dependent effects: lower content potentially increases strength whereas higher content diminishes it.

3.4.2. Feature Interaction Interpretation

Figure 14 presents SHAP dependence plots to visualize individual feature impacts on model outputs and their interactive effects; as shown in

Figure 14a, SHAP values exhibit significant fluctuations (−20 to +20) within the 200–500 kg/m

3 cement dosage range, yet demonstrate an overall positive correlation trend. Increasing cement dosage consistently elevates SHAP values, confirming cement’s substantial positive contribution to compressive strength predictions, with higher dosages being particularly critical for strength enhancement. Color gradients represent water content, revealing that under high-water conditions, cement increases correspond to more pronounced SHAP value elevations. This evidence indicates water content modulates cement’s strengthening efficacy, demonstrating a synergistic interaction effect where cement’s strength-enhancing potential is amplified under elevated water conditions.

As fly ash content increases, SHAP values initially decrease, then rise, and subsequently fluctuate—with more pronounced variation amplitudes occurring under high-cement conditions. This signifies a synergistic interaction between cement content and fly ash’s impact on concrete strength, where fly ash variations exert greater influence on strength development at high cement levels, as demonstrated in

Figure 14b. Concurrently, increasing fly ash correlates with decreasing cement content, leading to reduced SHAP values; this substitution relationship indicates that excessive cement replacement by fly ash may compromise concrete performance.

In the SHAP dependence plot for water,

Figure 14c, SHAP values decrease significantly from +10 to −8 as water content increases (150–200 kg/m

3), demonstrating a strong negative correlation that confirms excessive water reduces compressive strength; however, this negative effect is partially mitigated under high superplasticizer content conditions, indicating that superplasticizers improve strength by reducing water demand, whereby a notable synergistic interaction exists between these parameters.

Coarse and fine aggregate contents exhibit no discernible monotonic trends with SHAP values, as shown in

Figure 14e,f, both demonstrate optimal content ranges where they contribute favorably to concrete strength, beyond which their effects become variable and less predictable.

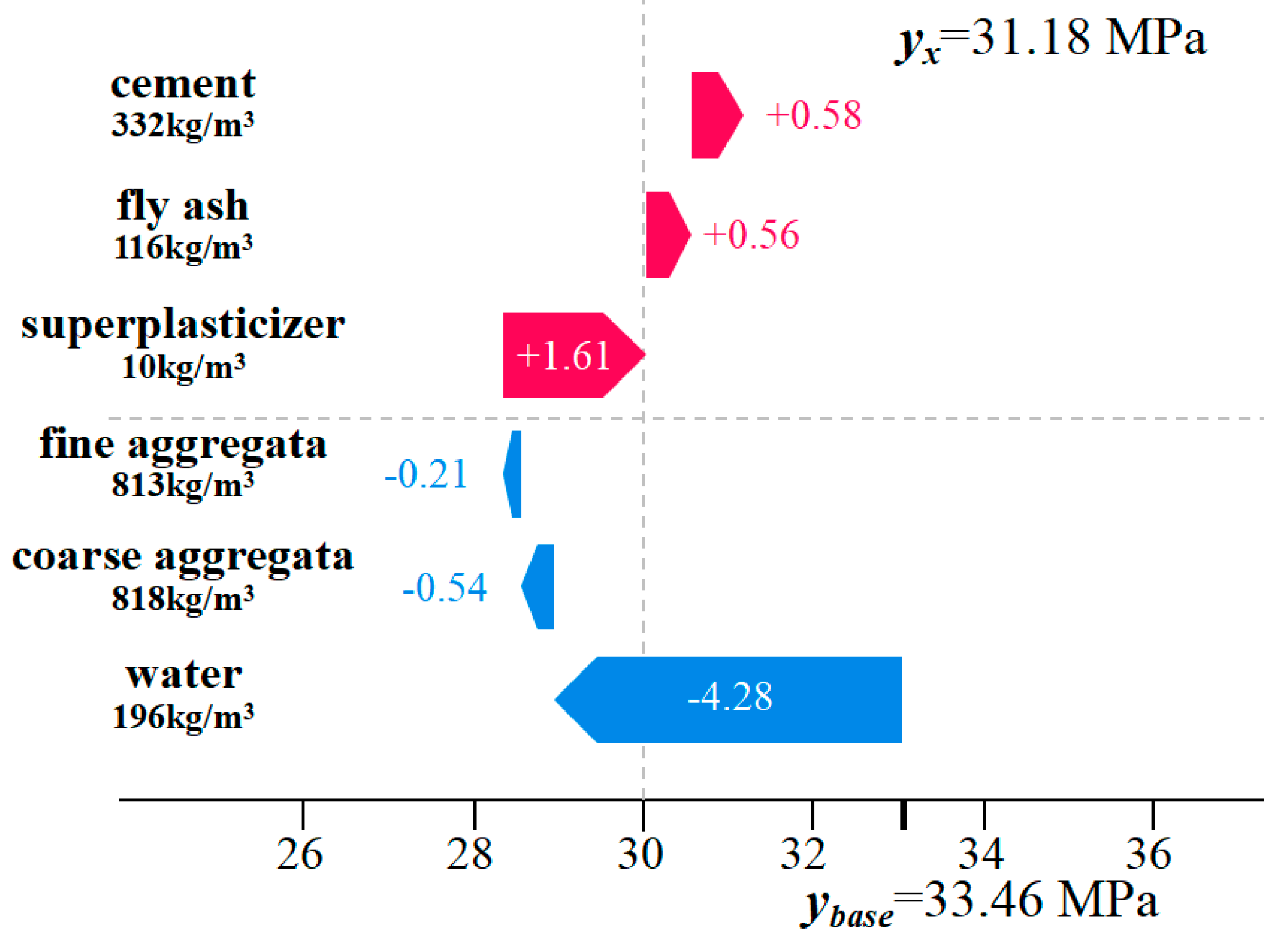

3.4.3. Local Explanation and Analysis

Local explanation is another interpretative approach provided by the SHAP method, used to interpret the prediction outcomes for individual samples within a dataset. For both global and local explanations, the sign (positive/negative) of the SHAP value represents the magnitude and direction of the driving force. The model prediction value equals the sum of the feature SHAP values and the baseline value.

Figure 15 illustrates the explanatory force plot for a sample randomly selected from the input dataset. In the figure, the baseline value for concrete strength is 33.46 MPa, while the actual predicted value is 31.18 MPa. The red arrow pointing left represents the direction of higher values, while the blue arrow pointing right represents the direction of lower values. Cement, fly ash, and superplasticizer are positioned in the direction of the red arrow, indicating that an increase in these component values would shift the model output above the baseline value of 31.18 MPa. Cement exhibits the longest force arm, signifying its substantial positive contribution to compressive strength. Conversely, water, coarse aggregate, and fine aggregate are positioned in the direction of the blue arrow, indicating that an increase in these component values would shift the model output below the baseline value.

4. Conclusions

This study systematically established a predictive model for the 28-day compressive strength of concrete based on an interpretable machine learning framework, integrating Bayesian optimization with the SHAP method. This research further investigated the key influencing mechanisms of material mix proportions on strength. Through modeling and optimization analysis of 223 sets of experimental data, the following main conclusions are drawn:

(1) Among the five predictive models, namely Gradient Boosting Trees, the CatBoost model, after Bayesian Optimization of its hyperparameters, demonstrated the best performance. Its coefficient of determination (R2) reached 0.9388, root mean square error (RMSE) was 2.7131 MPa, and mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) was 5.45%. All performance metrics were significantly superior to those of the other comparative models. Furthermore, box plot analysis from repeated validations confirmed that CatBoost exhibits the narrowest 95% confidence intervals (R2: [0.822, 0.977], RMSE: [1.707, 4.477], MAPE: [3.924, 7.419]), indicating superior performance stability.

(2) The integration of the machine learning framework with the Bayesian optimization algorithm plays a critical role in enhancing model predictive performance. Following hyperparameter optimization, not only was model accuracy improved, but the model’s generalization capability was also strengthened, validating the applicability of this approach to optimizing complex machine learning models.

(3) Compared with the empirical formulas specified in the current industry standard Specification for Mix Proportion Design of Ordinary Concrete (JGJ 55-2011), the CatBoost model established in this study demonstrates superior single-strength prediction accuracy under specific raw materials (e.g., P·O 42.5 cement, Class F Grade II fly ash) and curing conditions, achieving a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 2.94%. This validates the advantage of data-driven models in capturing complex nonlinear interactions among materials. External validation on the UCI dataset confirmed the model’s strong generalization capability and practical applicability in cross-dataset scenarios, achieving an R2 of 0.9014 on a well-matched feature subset and maintaining reasonable predictive performance (R2 = 0.7480) even under incomplete feature matching.

(4) SHAP analysis reveals that cement content is the most influential feature affecting concrete strength (mean SHAP value: 7.459), followed by water, superplasticizer, fly ash, and coarse/fine aggregates. Global interpretation uncovers nonlinear relationships among features: a synergistic effect between high cement content and appropriate superplasticizer dosage enhances strength, while excessive water significantly compromises compressive strength. Local dependence analysis further demonstrates that the cement–water interaction is particularly pronounced under high water–cement ratios, and the substitution effect of fly ash requires dynamic optimization adjustments based on cement content.

It is important to note that this study was conducted under standardized laboratory curing conditions (20 °C, ≥95% RH), which, while enabling a clear interpretation of mix proportion effects, limits the model’s direct application to real-world scenarios with fluctuating environments. Future research will therefore focus on enhancing the model’s practical utility and performance. This will involve incorporating real-time environmental parameters to improve on-site adaptability, while simultaneously exploring newer machine learning architectures on larger datasets to unlock greater predictive accuracy and material insight.