1. Introduction

For the current steel industry, the energy consumed in ironmaking is mainly carbonaceous energy and accompanied by a large amount of CO

2, and the excessive emission of CO

2 will have a serious impact on the environment [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. In order to reduce the emission of CO

2 in the ironmaking process, it may be a better way to use hydrogen-containing materials to replace part of the carbonaceous materials at present [

7,

8], in which the reduction behavior of iron ore under H

2–CO atmosphere will be involved. Therefore, it is necessary to systematically study the reaction behavior of iron oxides with H

2–CO gas mixture.

According to fundamental principles of reduction kinetics, in metallurgical processes, the reduction behavior of metal oxides (including iron oxides) is generally governed by a complex interplay among multiple parameters, primarily including the composition and flow rate of the gas reactant, the inherent physical properties of the iron oxide, and the reaction temperature. Du et al. [

9] investigated the reduction behavior of hematite powder to magnetite by H

2 at low temperatures, and the experimental results demonstrated that below 673 K, the reduction reaction’s possible rate-controlling step was controlled by the interfacial chemical reaction. However, when the temperature exceeded 723 K, the possible controlling mechanism shifted to gas diffusion. Yi et al. [

10] monitored the volumetric changes in iron ore pellets during reduction by H

2–CO gas mixture at 1073 K to 1273 K, and the results revealed that the ore pellet expansion was enhanced with increasing temperature and CO concentration, reaching its maximum rate when the reduction degree was 20–40% due to the formation of the wustite phase and pellet expansion. Jeongseog et al. [

11] examined the structure of the metallic iron product formed during the reduction of hematite by an H

2–CO gas mixture. Compared to the structure produced by pure H

2 reduction at 1073 K, the metallic iron generated using CO exhibited a more friable structure and less inter-particle sintering, which can be attributed to the carbon deposition during CO reaction and the difference in diffusion behavior and reduction behavior between H

2 and CO.

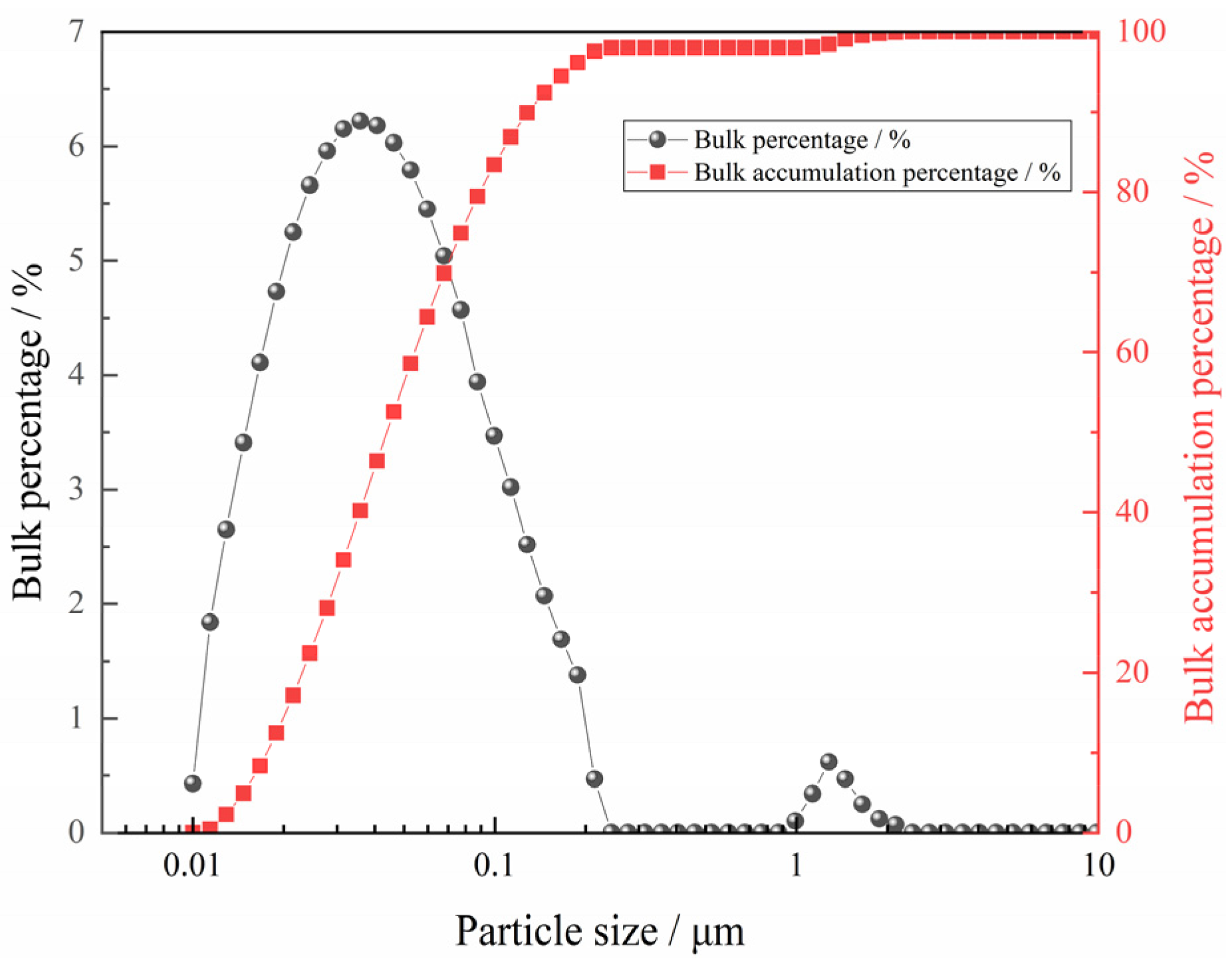

It is evident from the current published research that studies on the reduction of iron oxides by H

2–CO gas mixture predominantly focus on conventionally scaled materials. Rajakumar et al. [

12] systematically investigated the reduction of wustite particles with particle sizes of 100 μm, 200 μm, 300 μm, and 400 μm by H

2–CO gas mixtures at 1173 K–1373 K, and the results revealed that under H

2 reduction conditions, abundant metallic iron nuclei formed on the wustite surface, whereas fewer nuclei generated under CO reduction, but the growth rate of iron nuclei was faster than that of H

2. EI-Geassy et al. [

13] examined the reduction behavior of wustite pellets (150–250 μm) using H

2–CO gas mixture at 1173 K–1373 K, and demonstrated that introducing 5% CO into pure H

2 gas reactant would rapidly reduce the rate of reduction reaction. However, when the CO content in the H

2–CO gas mixture exceeded 25%, the difference in the reduction rate between the H

2–CO and H

2–Ar atmospheres diminished. The main influence mechanism was that once CO was adsorbed on the active site of the wustite, it occupied the adsorption site of H

2 at low CO content, which hindered the reaction. When CO content was greater than 25%, the surface active sites were basically covered by CO, so the effect of further increasing CO on the active sites was limited, thus reducing the reaction rate difference. Fruehan et al. [

14] studied the reduction kinetics of iron oxide with different crystal sizes under H

2 atmosphere. The results indicated that for wustite with a grain size of approximately 1 μm, the reduction by H

2 showed negligible deceleration until a reduction degree of 95% was reached. In contrast, for samples with a grain size around 2 μm, the reduction rate decreased significantly even before the possible rate-controlling step shifted to gas diffusion. This study further proposed two kinetic mechanisms, provisionally designated as the gas-reduction kinetic equation and the solid-state diffusion kinetic equation, and identified the criteria for switching between these mechanisms based on the grain size of wustite and the thickness of the generated iron layer. For wustite grains around 1 μm in size, the gas-reduction kinetic equation remained applicable up to nearly complete reduction (>99% reduction degree); whereas for grains of 2 μm and larger, it was necessary to switch to the solid-state diffusion equation when the iron layer thickness was about 1 μm and the reduction degree reached 60–70%. Thus, it is noteworthy that relatively significant research gaps remain concerning the reaction behavior of ultrafine iron oxide powder (<1 μm) with H

2–CO gas mixture, and addressing this knowledge gap is crucial for developing low-carbon and efficient ironmaking technologies. Based on this situation, the present work conducts systematic experiments on the reduction of ultrafine ferric oxide powder (with the particle size range <1 μm) by H

2–CO gas mixture, and further improves the basic research on the reaction behavior of iron oxide and H

2–CO gas mixture. The purpose is to clarify the reaction kinetics and apparent activation energy of the reaction under low particle size, and to provide theoretical support for metallurgical process optimization.

3. Results and Discussion

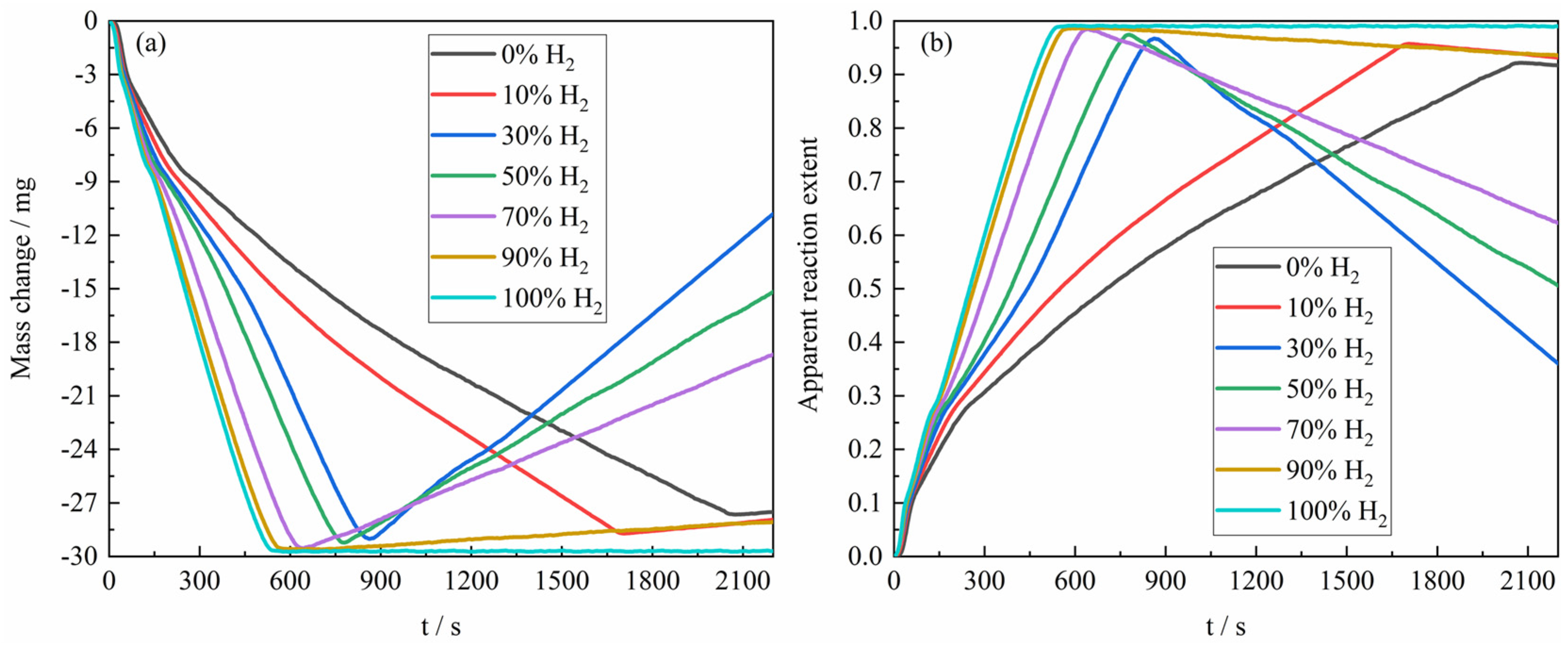

Figure 4a presents the mass change curves during the reduction of the ferric oxide sample by H

2–CO gas mixture with varying composition ratios at 1023 K. When the gas reactant only contained pure H

2, the sample exhibited the greatest mass loss, approaching the theoretical oxygen loss of 30 mg for the complete reduction of 100 mg Fe

2O

3 to Fe. As the CO content in the H

2–CO gas mixture increased, the mass loss of reaction gradually decreased, reaching only −27.6 mg under pure CO. The reduction process consisted of three distinct stages (Fe

2O

3 → Fe

3O

4, Fe

3O

4 → FeO, and FeO → Fe), which correspond, respectively, to mass changes in approximately 0 to −3 mg (Fe

2O

3 → Fe

3O

4) and −3 to −9 mg (Fe

3O

4 → FeO), and the average reaction rate at different stages of the reaction would change accordingly. In the later stages of reaction, carbon deposition occurred via the Boudouard reaction (2CO → C + CO

2), which corresponded to the mass increase of the reaction sample in the figure. Furthermore, the experimental results revealed that the rate of the carbon deposition reaction would tend to increase first and then decrease with the increase of the proportion of CO in the H

2–CO gas mixture, which can be attributed to the dual role of H

2. The main reason is that the presence of H

2 promotes the carbon deposition [

19] by facilitating the formation of an active intermediate during the Boudouard reaction. However, when the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture is relatively high, the CO content, as the main reactant of carbon deposition, is significantly reduced, resulting in a decrease in the carbon deposition rate. In addition, the metallic Fe formed under a relatively high H

2 atmosphere is prone to sintering densification, which reduces the effective surface area for carbon deposition and further reduces the rate and degree of carbon deposition. In addition, the conversion of sample mass change to apparent reaction extent was carried out according to Formula (1), and the results of apparent reaction extent for the reaction of H

2–CO gas mixture of different composition ratios with ferric oxide sample at 1023 K were presented in

Figure 4b.

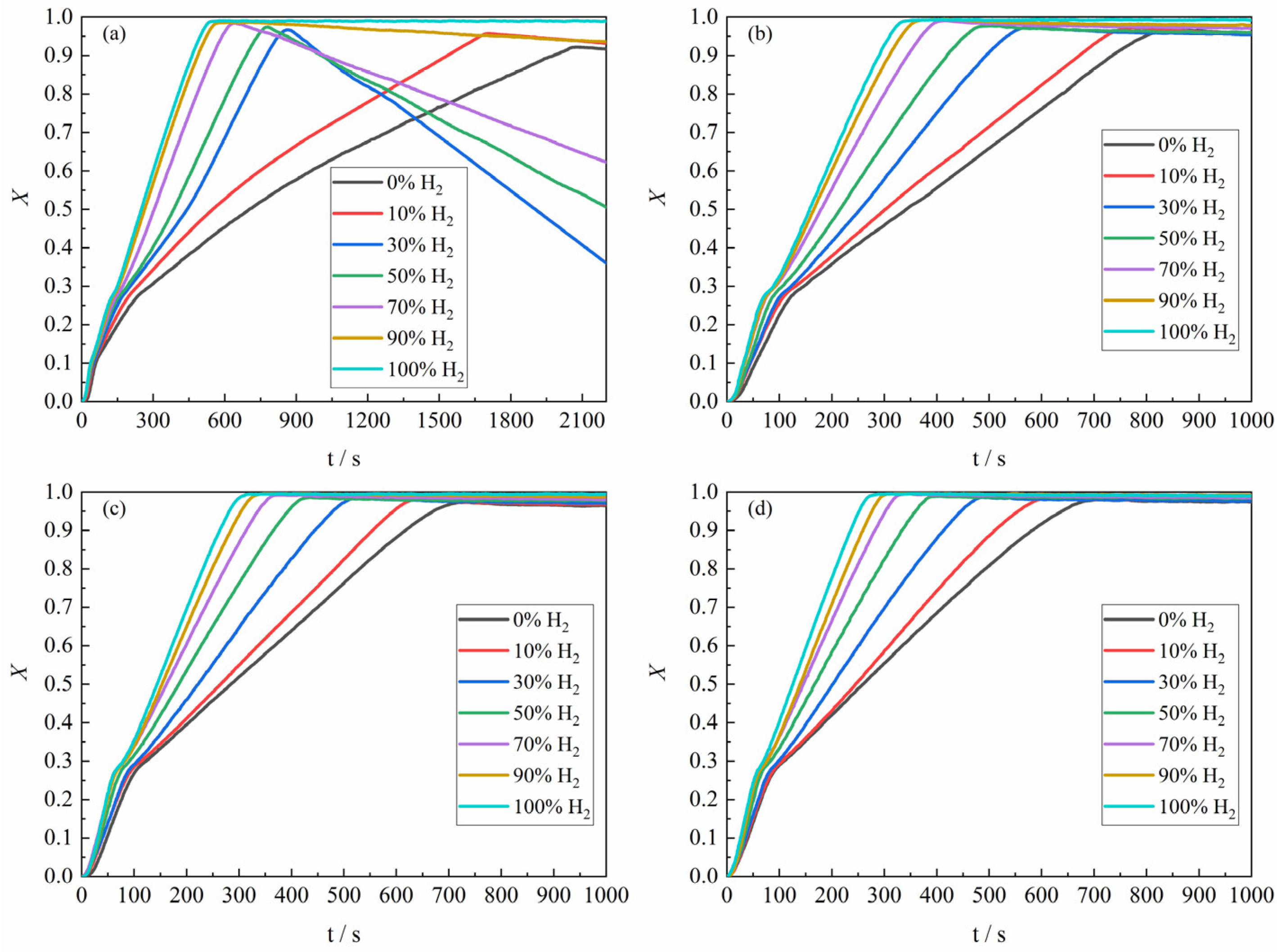

As shown in

Figure 5, the overall experimental results for the apparent reaction extent of H

2–CO gas mixture of different composition ratios with ferric oxide sample at 1023 K–1373 K were demonstrated. It can be found from

Figure 5b that the higher the proportion of H

2 in the H

2–CO gas mixture, the closer the mass change in the ferric oxide sample was to the theoretical maximum mass loss, which was consistent with the reaction condition at 1023 K. Moreover, when the gas reactant only contained pure CO, the maximum apparent reaction extent was higher than the apparent reaction extent of pure CO reducing ferric oxide sample at 1023 K. The apparent reaction extent curves of the ferric oxide sample with H

2–CO gas mixture at 1273 K and 1373 K are shown in

Figure 5c,d.

In summary, the reaction of the ferric oxide sample by the H

2–CO gas mixture during the reduction stage basically exhibited a consistent trend in apparent reaction extent curves. The time required to reach maximum mass loss decreased with increasing H

2 content, where the largest decrease was in the period of the increase of the H

2 content from 0% to 30%. At 1373 K, the reaction of the ferric oxide sample was relatively complete, and the H

2–CO gas mixture basically could reduce the ferric oxide sample to metallic iron, though the time required was similar to that at 1273 K.

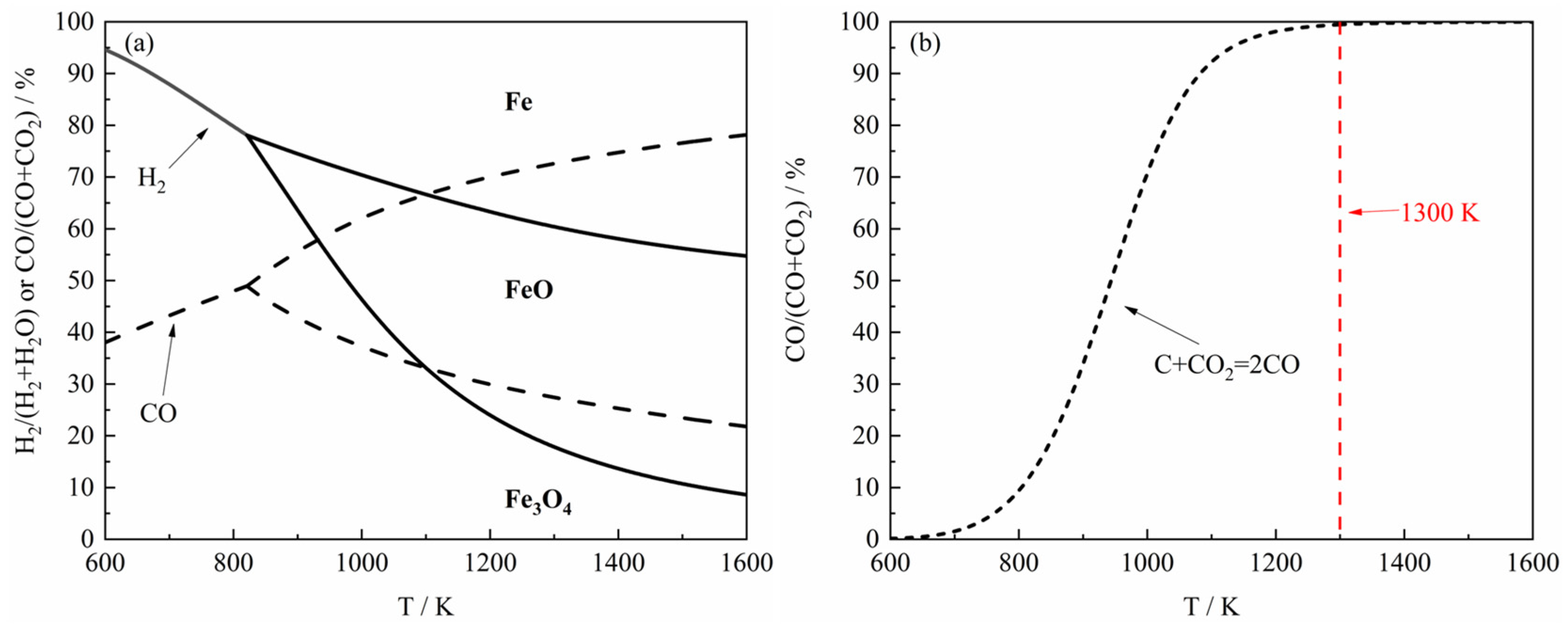

Figure 5d indicated that carbon deposition was largely suppressed at 1373 K, consistent with the thermodynamic trend shown in

Figure 3. Additionally, the maximum apparent volume of the product from CO reduction was approximately four times greater than that from H

2 reduction, as determined by measuring the apparent volume of the product sample in the crucible after reaction, in agreement with the results reported by Nasr et al. [

10,

24,

25], further confirming more severe sintering under H

2 atmosphere.

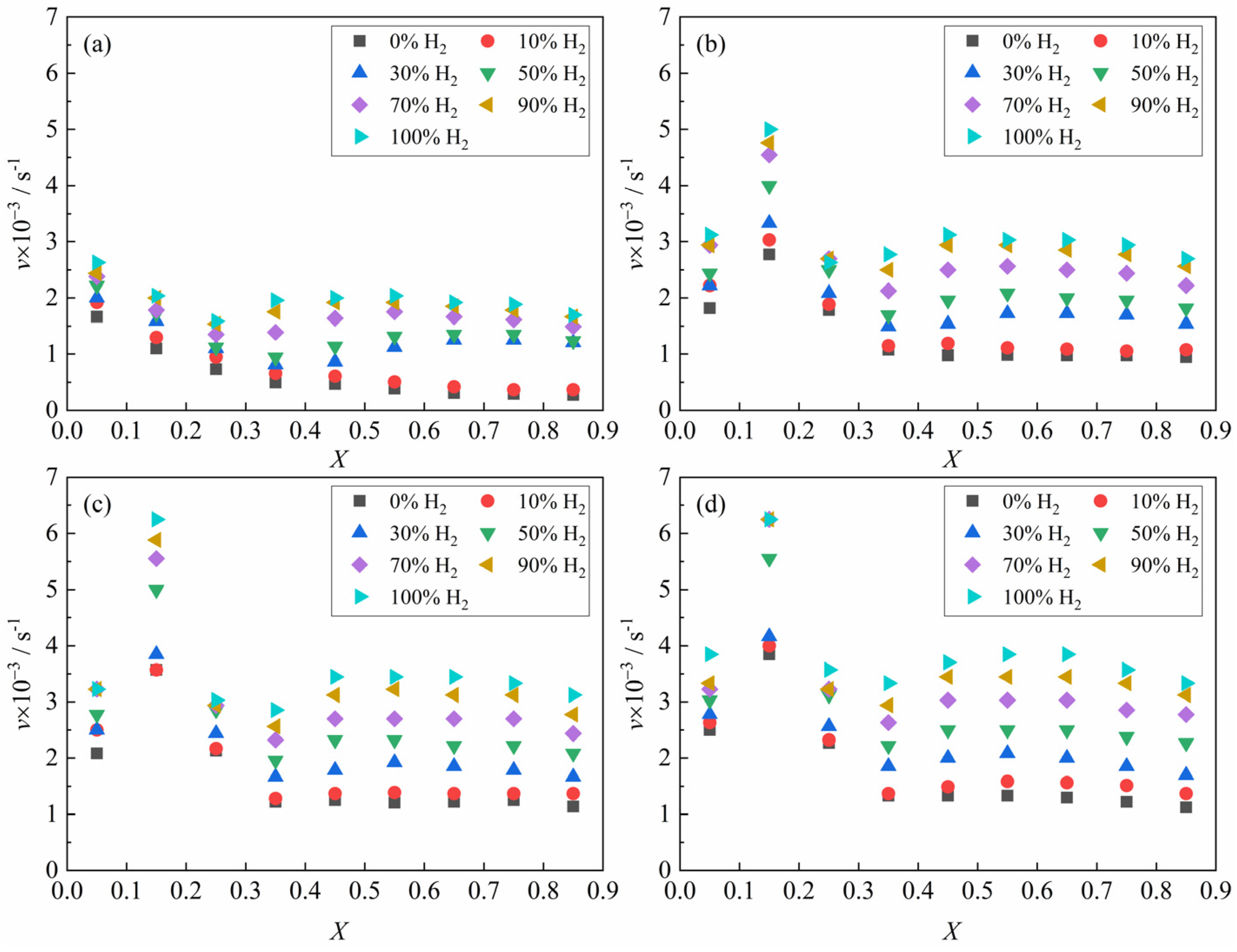

Figure 6 presents the relationship between the average reaction rate of the ferric oxide sample with the H

2–CO gas mixture and the apparent reaction extent under different conditions. At 1023 K, the average reaction rate decreased continuously within the apparent reaction extent range of 0–0.3 (Fe

2O

3 → Fe

3O

4 → FeO). At temperatures ≥1173 K, the average reaction rate first increased and then decreased. When the apparent reaction extent exceeded 0.3, the reaction entered the third reduction stage (FeO → Fe), which has been identified in

Figure 5 and previous studies [

19,

20,

26,

27] as the rate-controlling stage of the overall process. Based on the apparent reaction extent curves and average reaction rate of the third reduction stage (FeO → Fe), this process can be divided into three periods [

28]: the incubation period, the acceleration period, and the exhaustion period. Referring to the systematic analysis of the reduction morphology of FeO by John et al. [

29,

30] and combining the results of the present experiments, it was found that in the initial stage of FeO reduction, pits formed on the FeO surface before extensive aggregation of metallic iron clusters. The main reason may be caused by lattice vacancy formation due to oxygen loss. During the incubation period, the gas reactant reacted with the oxygen atom in the FeO at the reaction interface and brought it out, while the oxygen atom in the FeO inside the reaction interface needed to diffuse to the reaction interface first and then reacted with the gas reactant. As the reaction progressed, iron atoms initially covering the reaction interface in localized regions of the sample agglomerated and grew, thereby exposing fresh FeO surfaces. And the gas reactant could directly contact the surface of the fresh FeO and react, causing the local reaction rate to be accelerated. When the whole sample showed this phenomenon, the macroscopic performance was that the reaction rate increased significantly, which means that the incubation period was over and the acceleration period had entered. During the acceleration period, the reaction interface continued to expand into the interior of the sample, causing the reaction interface to continuously increase. Due to the large consumption of FeO in the sample, the reaction finally entered the exhaustion period. In addition, according to

Figure 5 and other research results [

31], part of the iron oxide was tightly surrounded by dense metal iron and was difficult to reduce under certain reaction conditions in the exhaustion period.

During the reaction, it was assumed that the reduction of the sample with the gas reactant to produce a single iron atom was equivalent to the formation of a single-step nucleus, and then the overall nucleation rate was the reaction rate of the sample. According to the Jacobs single-step nucleation assumption theory [

32,

33], the rate of nucleation,

, can be derived using the following formula [

19]:

where

and

represent the rate constant of nucleation and the potential nucleation sites assuming equivalent probability of nucleation, and

is the number of active growth nuclei at time

t, respectively. Integration of Formula (3) using variable separation, the result can be obtained:

Substituting Formula (4) back into Formula (3) provides the time-dependent rate of nucleation:

The apparent average nucleation rate,

, over the nucleation period

, is defined as:

From

Figure 6, it can be indicated that the experimentally determined average reaction rate value is relatively low. Considering Formula (3), this observation implies that the rate constant of nucleation

is likely also small. Consequently, the exponential term in Formula (5) is approximately equal to 1. Therefore, it can be simplified to the expression for the apparent average nucleation rate:

As El-Geassy et al. [

13,

34] demonstrated, a relatively strong correlation between the apparent average nucleation rate and CO concentration in the gas reactant

. Therefore, provided

is considered to be a constant, there should be a functional relationship (

) between

and

. Based on Formula (7) and this inferred functional relationship (

) deduced from theoretical and experimental results, it can be simplified rewritten as a constant part (

) and a functional part (

) to further express the correlation on

:

Under the experimental conditions of 1023 K, relatively substantial carbon deposition induced by CO-containing gas reactant during the later stage of the reduction reaction introduces significant systematic deviations between the apparent reaction extent and the reduction extent, resulting in the inability to obtain real-time and accurate reduction extent data. Consequently, the reduction rate at this temperature cannot be analyzed. The experimental results in

Figure 6b–d, combined with Formula (8), revealed the corresponding relationship between the apparent average reduction rate of the reaction of ferric oxide samples with H

2–CO gas mixture and the composition of H

2–CO gas mixture in the temperature range of 1173 K to 1373 K. It can be found that the logarithm of apparent average reduction rate was basically linear with the CO content, as shown in

Figure 7.

where

and

are the slope of Formula (9) (a constant) and the apparent average reduction rate under pure H

2 conditions. In addition, since the specific functional relationship (

) between the nucleation rate and the gas reactant composition is not clear. Formula (9) is not derived strictly by a pure mathematical model, but obtained by assuming conditions and combining with experimental results, which can still be applied to predict relatively accurately the apparent average reaction rate under other atmosphere conditions.

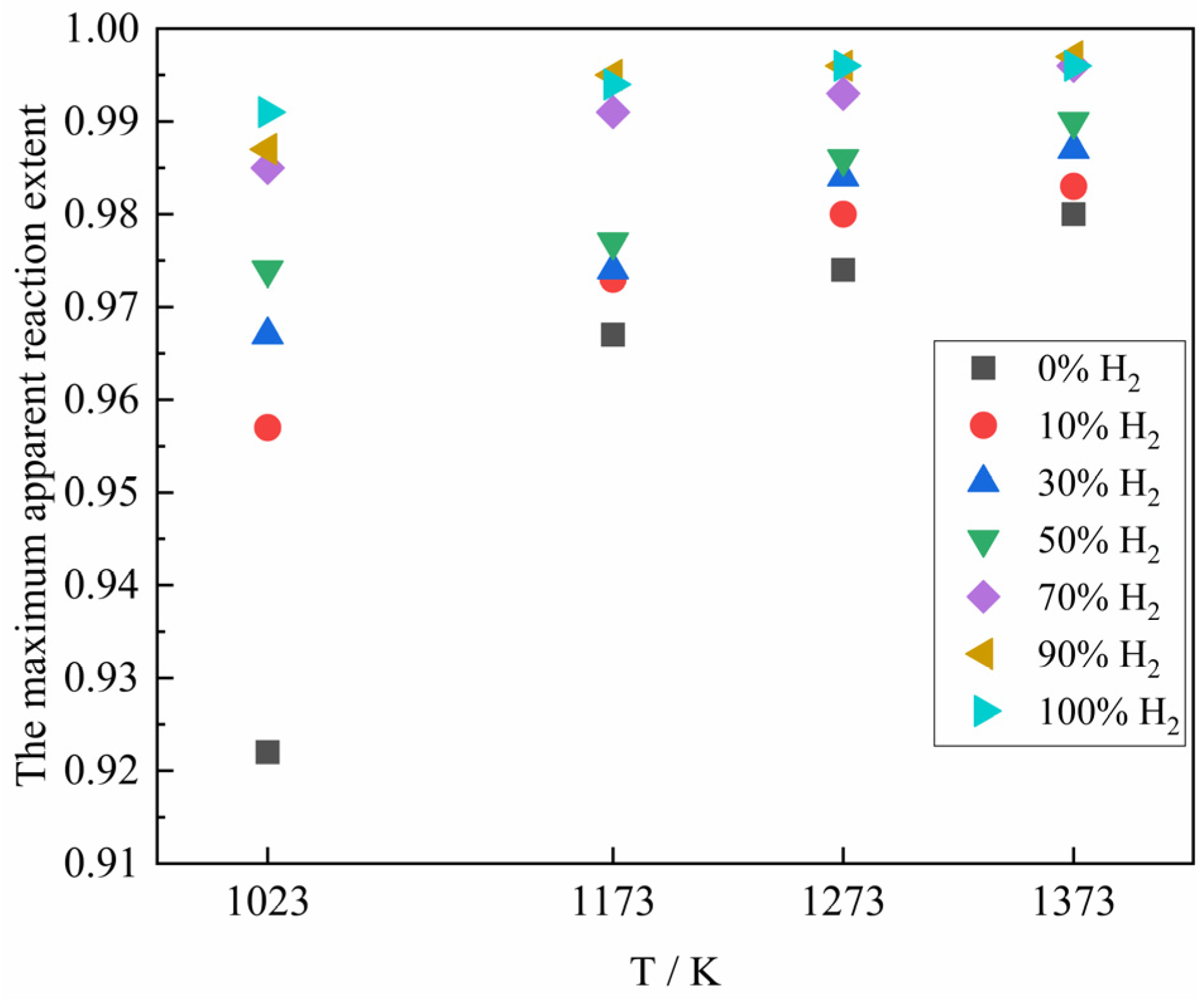

Figure 8 represents the variation of the maximum apparent reaction extent for the reaction of the ferric oxide sample with the H

2–CO gas mixture under different conditions. As shown in

Figure 8, with the increase of reaction temperature, the maximum apparent reaction extent presented an increasing trend. The possible explanation was that although higher temperatures accelerated the reduction rate and promoted sintering of the formed iron, the resulting structural changes were not sufficient to completely block gas diffusion pathways within the experimental timeframe. Consequently, the gas reactant could still access the reaction interface, allowing the reduction to proceed. The maximum apparent reaction extent of the sample also increased with the increase of H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture. Although the increase of H

2 content would make the sintering situation more serious (the faster kinetics and enhanced diffusion) and affect the gas diffusion, it could still improve the rate and apparent reaction extent of the reduction reaction as a whole. When the gas reactant was pure CO for the reduction reaction, the maximum apparent reaction extent at 1023 K was only 0.922, which may be mainly caused by the following two reasons. Firstly, during the reduction of ferric oxide sample by CO, due to the slow reduction rate of CO, the Fe reduced slowly blocked the pores after a long period of mutual diffusion, and compared with H

2, the large molecular structure and relatively low diffusion capacity of CO, which eventually made some iron oxides in the center of the sample were not completely reduced to Fe within the reaction time. Secondly, in the presence of Fe, CO as a gas reactant would take place carbon deposition reaction at the same time, resulting in the presence of graphite or cementite in the reduced sample, which was manifested as sample weight gain. In addition, when the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture was higher than 70%, the maximum apparent reaction extent of the sample was basically the same.

In order to further investigate the relationship between the reaction products and the components of the H

2–CO gas mixture, the carbon deposition phenomenon during the reduction process was briefly analyzed in this paper. As shown in

Figure 3, the thermodynamic equilibrium phase diagram of the carbon deposition reaction at different temperatures was presented, and it can be found from the figure that the carbon deposition reaction can only take place under higher CO content at high temperatures. According to previous studies [

19], in the presence of Fe, the carbon deposition reaction in H

2–CO gas mixture may be represented by the following steps, where the generation rate of

is relatively faster than

:

where

,

and

are the metastable state of H

2–CO active molecule, the metastable state of CO–CO active molecule, and the vacant active site on metallic Fe, respectively.

Overall, it can be found from

Figure 5 that the carbon deposition phenomenon was more serious at 1023 K, but with the increase of reaction temperature, the carbon deposition phenomenon decreased rapidly until it almost disappeared. In order to study the carbon deposition phenomenon of the product at 1023 K, the reaction was carried out again under the same experimental conditions as

Table 1. When the sample reached the maximum apparent reaction extent, the input of H

2–CO gas mixture was immediately stopped, and then the Ar gas was introduced, and the thermogravimetric analyzer was quickly cooled, instead of continuing the reaction. The reaction products were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD), and the results are shown in

Figure 9. From the figure, it can be found that when the gas reactant with a gas composition of 100% CO and 10% H

2–90% CO reacted with the ferric oxide sample, there would be a small amount of Fe

3C in the reaction product. However, as the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture continued to increase, there was basically only metal Fe in the reaction product. Therefore, it can be concluded that when the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture was higher than 30% at 1023 K, the carbon deposition reaction basically does not occur during the reduction reaction, or the C produced by the carbon deposition reaction was rapidly consumed (carbon direct reaction consumption or Boudouard reaction equilibrium shift), but the carbon deposition phenomenon occurred when the H

2 content was lower than 10%, which is in accordance with Szekely’s results [

35].

Further investigations were conducted at 1173 K under an H

2–CO gas mixture with H

2 content below 10%. The XRD diffraction pattern of the reaction products (

Figure 10) show basically no detectable Fe

3C phase (PDF#85-1317, the standard X-ray diffraction pattern is shown in

Figure S1 of Supporting Information), and the phase of the product was basically metal Fe (PDF#87-0721, the standard X-ray diffraction pattern is shown in

Figure S2 of Supporting Information). These results confirm that the reduction stage of the reaction between H

2–CO gas mixture and ferric oxide sample was basically not accompanied by the occurrence of carbon deposition reaction at 1173 K, consistent with the thermodynamic analysis in

Figure 3. In other words, under the same conditions, the carbon deposition phenomenon would be more difficult to occur with the increase of temperature in theory. To summarize, by detecting the phase of the reaction product and combining the apparent reaction extent curves, it can be seen that under the experimental conditions of this study, carbon deposition reaction occurred in the reduction stage (during FeO → Fe) only when the reaction temperature was 1023 K and the content of H

2 in the H

2–CO gas mixture was less than 30%, thus affecting the results of experiment.

As mentioned above, the third stage of the reaction is the controlling stage of the whole reaction. Therefore, in order to further explore the reaction behavior of the ferric oxide sample with an H

2–CO gas mixture, the rate-controlling step of the third stage of the reaction should be clarified, and the apparent activation energy (

Ea) obtained contributes to the understanding of the rate-controlling step. According to the Arrhenius Equation, the value of

Ea can be obtained [

36]:

where

A0,

k,

R,

f(

X),

F(

X) are the pre-exponential factor, the reaction rate constant, the gas constant, the reaction mechanism model differential form function, and the integral form function, respectively. Separating variables and integrating Formula (17), it can be derived that

Previous studies [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43] provide the proposed mathematical functions for the reaction kinetic model (with a comprehensive summary provided in the previous publication, Reference [

19]), which include the majority of probable mechanisms controlling the reaction. These functions will be employed in the mathematical modeling of the reaction kinetic data, with the optimal fitting functions being selected to eventually determine the dominant controlling mechanism of the reaction, where the slope of the fitting function is the rate constant of the reaction (

k), as shown in Formula (19), and the apparent activation energy is also indirectly obtained by the slope according to Formula (16).

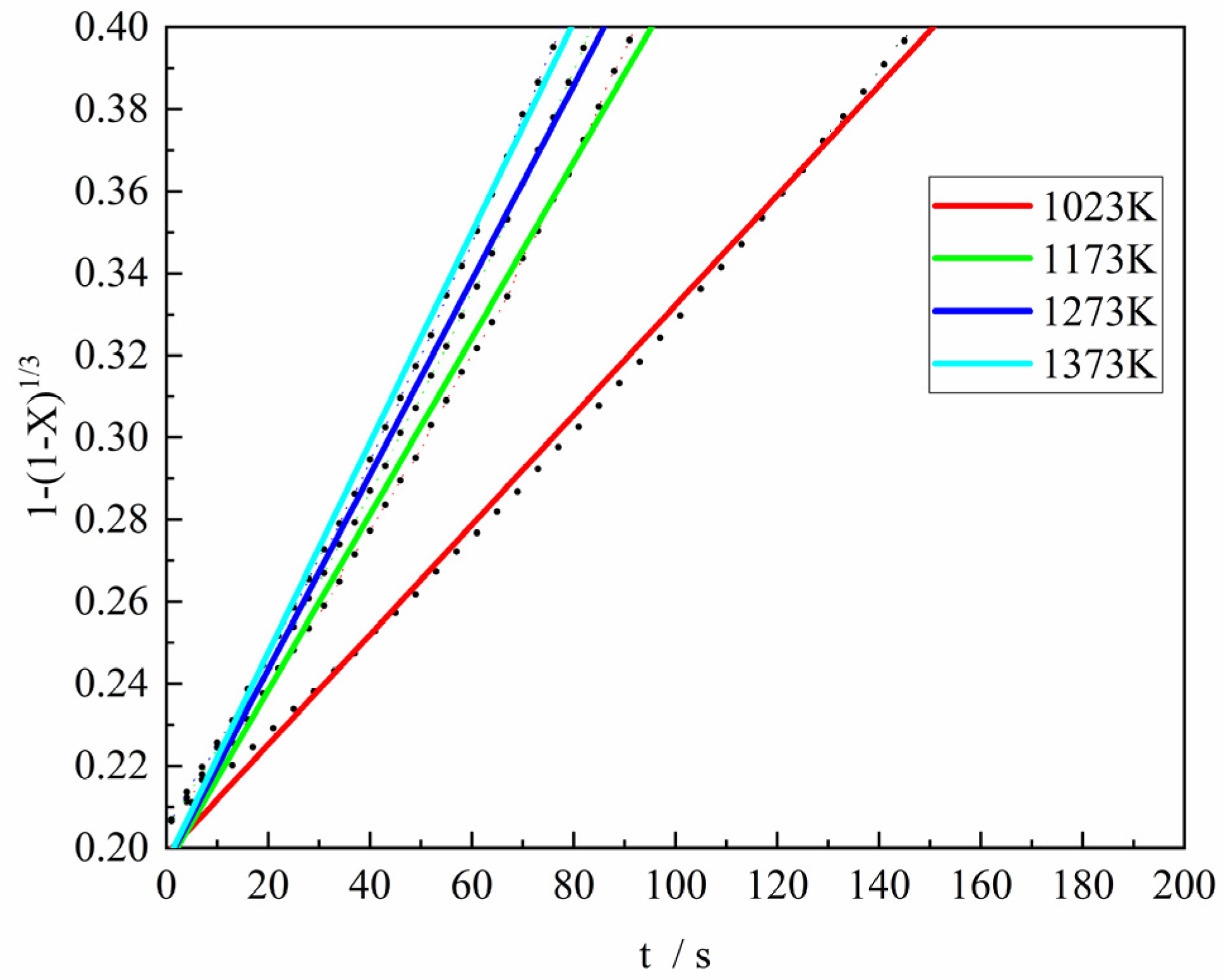

Figure 11 shows the fitting results of the Contracting Volume model (differential form:

, integral form:

) was used to fit the third stage of the reduction reaction between the gas reactant with H

2 content of 100% and the ferric oxide sample. It can be found from the figure that when the Contracting Volume model was used to fit the experimental data, the consistency was good and the fitting degree was high, and the correlation coefficient (R

2) of the Contracting Volume model fitting was all greater than 0.99. Consequently, it was considered that the Contracting Volume model was relatively reasonable under this condition. In the same way, the rate constant at each experimental temperature can be derived.

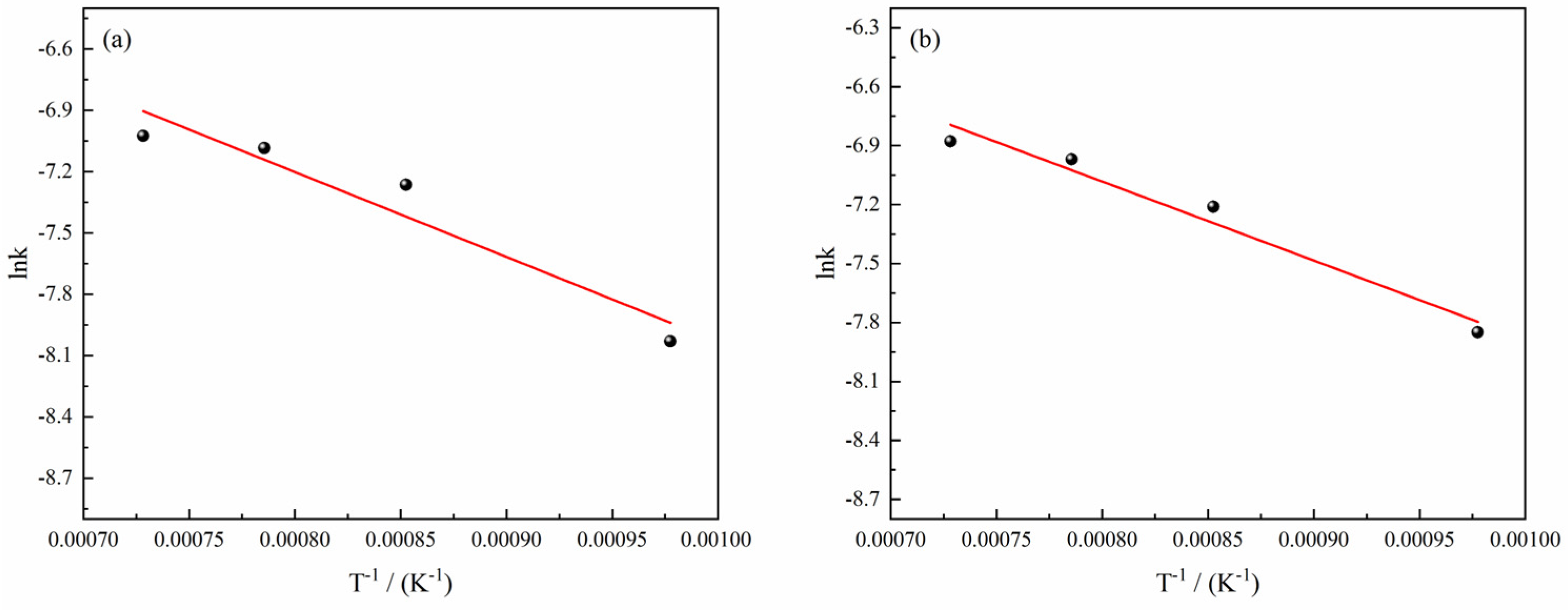

Figure 12 depicts a linear fitting relationship between the natural logarithm (ln

k) of the rate constant of the reduction reaction of H

2–CO gas mixture with ferric oxide sample and the reciprocal of temperature (1/

T) under different conditions (the complete data diagram is shown in

Figure S4 of Supporting Information), from which it can be found that the linear fitting degree between ln

k and 1/

T was relatively better, and the slope of the fitting line was the negative value of the quotient of the apparent activation energy and the Molar Gas Constant (

). As a result, the apparent activation energy under different conditions obtained from

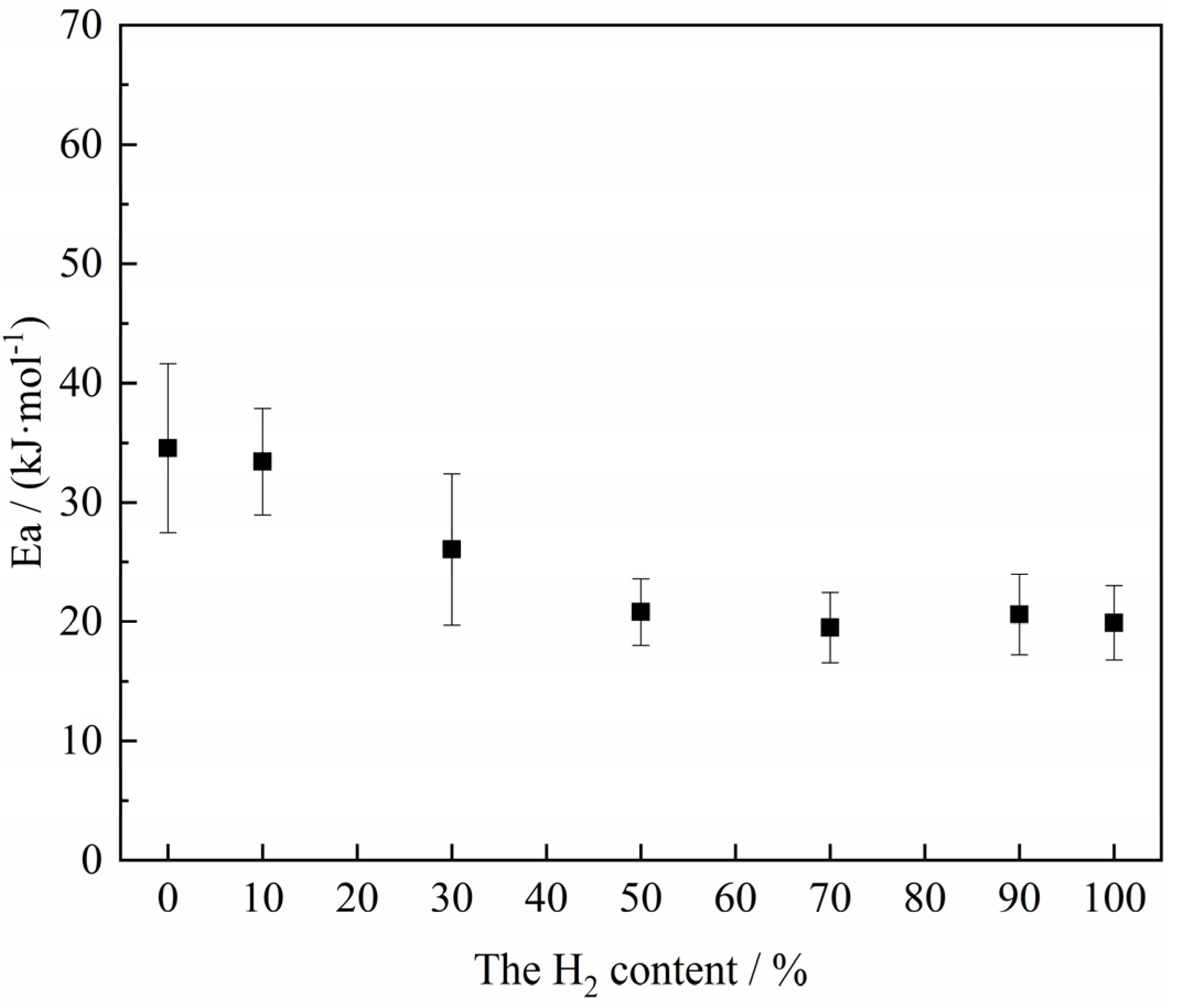

Figure S4 is shown in

Figure 13. The results show that the apparent activation energy exhibited a tendency to decrease with the decrease of H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture on the whole. When the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture was less than 10%, the apparent activation energy was maintained at about 34 kJ/mol. According to the empirical relationship between the apparent activation energy and the reaction rate-controlling step studied by Nasr [

34] (Gas diffusion: 8–16 kJ/mol; Combined gas diffusion and interfacial chemical reaction: 29–42 kJ/mol; Interfacial chemical reaction: 60~67 kJ/mol; Solid-state diffusion: >90 kJ/mol), the possible rate-controlling step is the combined gas diffusion and interfacial chemical reaction.

When the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture was more than 30%, the apparent activation energy of the reaction was basically maintained at about 20 kJ/mol to 25 kJ/mol, and the possible rate-controlling step was combined gas diffusion and interfacial chemical reaction influenced towards the gas diffusion. The main reason could be that when the H

2 content in the H

2–CO gas mixture was high, the sintering and volume shrinkage of the sample was more serious due to its own structural characteristics, resulting in a significant decrease in porosity [

12,

44], which further made it more difficult for the gas reactant to diffuse to the reaction interface even though H

2 had a small molecular structure. Moreover, H

2 had a faster rate of interfacial chemical reaction compared to CO. As a result, the reaction was more inclined to gas diffusion controlling under these atmosphere conditions.