Geopolymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Chemical Stability, Leaching Behaviour, and Radiological Safety

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Component Functions

- -

- Mixture I utilizes a highly concentrated sodium hydroxide solution (16 M NaOH), providing intense alkalinity that promotes rapid precursor dissolution, fast setting, and early strength development. This makes it suitable for time-sensitive or rapid buildup applications where early load-bearing is critical.

- -

- Mixture II incorporates a commercial sodium silicate solution (Baucis waterglass; Ceske Lupkove Zavody, Nove Straseci, Czech Republic), offering a more balanced and controlled activation mechanism. The presence of soluble silica moderates reaction kinetics, enhances workability, and improves compatibility with thixotropic additives such as cellulose and sand, which is key for applications requiring high shape retention and delayed setting.

2.2. Mixture Composition

- Mixture I is activated using a concentrated sodium hydroxide solution (16 M NaOH) in combination with waterglass. It contains graphite and other fine-scale additives to enhance matrix cohesion and early mechanical performance.

- Mixture II employs a commercial sodium silicate solution (Baucis) as the sole activator. It includes additional rheology modifiers, cellulose, and sand to improve shape retention, stability, and workability during extrusion. The anhydrite content is also slightly increased to compensate for delayed setting behaviour.

2.3. 3D Printing Process

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Leaching Behaviour

3.2. Radioactivity Behaviour

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Raza, M.H.; Zhong, R.Y. A sustainable roadmap for additive manufacturing using geopolymers in construction industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 186, 106592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanferla, P.; Gharzouni, A.; Texier-Mandoki, N.; Bourbon, X.; de la Plaza, I.S.; Rossignol, S. Polycondensation reaction effect on the thermal behavior of metakaolin-based potassium geopolymers. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 114, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, H.; Neithalath, N. Synthesis and characterization of 3d-printable geopolymeric foams for thermally efficient building envelope materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2019, 104, 103377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorenko, G.; Kasprzhitskii, A. Geopolymer additive manufacturing: A review. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 55, 102782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, L.; Apicella, A.; Perrotta, V.; Aversa, R. Geopolymer materials for extrusion-based 3d-printing: A review. Polymers 2023, 15, 4688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archez, J.; Texier-Mandoki, N.; Bourbon, X.; Caron, J.F.; Rossignol, S. Shaping of geopolymer composites by 3d printing. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 34, 101894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.G.; Zhang, G.-H. Feasibility of underwater 3d printing: Effects of anti-washout admixtures on printability and strength of mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Gądek, S.; Dynowski, P.; Tran, D.H.; Rudziewicz, M.; Pose, S.; Grab, T. Additive manufacturing in underwater applications. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Oliwa, K.; Gądek, S.; Dynowski, P.; Źróbek, A.; Lin, W.-T. A review of additive manufacturing techniques in artificial reef construction: Materials, processes, and ecological impact. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Tao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, L.; Tittelboom, K.V.; Schutter, G.D. Development of 3d printable alkali-activated slag-metakaolin concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 444, 137775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilcan, H.; Sahin, O.; Kul, A.; Ozcelikci, E.; Sahmaran, M. Rheological property and extrudability performance assessment of construction and demolition waste-based geopolymer mortars with varied testing protocols. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2023, 136, 104891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwalla, J.; Saba, M.; Assaad, J.; El-Hassan, H. Performance of metakaolin-based alkali-activated mortar for underwater placement. In The 1st International Conference on Net-Zero Built Environment; Kioumarsi, M., Shafei, B., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 93–104. [Google Scholar]

- Ly, O.; Yoris-Nobile, A.I.; Sebaibi, N.; Blanco-Fernandez, E.; Boutouil, M.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Hall, A.E.; Herbert, R.J.H.; Deboucha, W.; Reis, B.; et al. Optimisation of 3d printed concrete for artificial reefs: Biofouling and mechanical analysis. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 272, 121649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoris-Nobile, A.I.; Slebi-Acevedo, C.J.; Lizasoain-Arteaga, E.; Indacoechea-Vega, I.; Blanco-Fernandez, E.; Castro-Fresno, D.; Alonso-Estebanez, A.; Alonso-Cañon, S.; Real-Gutierrez, C.; Boukhelf, F.; et al. Artificial reefs built by 3d printing: Systematisation in the design, material selection and fabrication. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 362, 129766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, Q.; Chen, B.; Zhang, S.; Ferrara, L.; Li, W. Effect of raw materials on the performance of 3d printing geopolymer: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 84, 108501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, L.; Xu, L.; Wu, K.; Yang, Z. The failure mechanisms of precast geopolymer after water immersion. Materials 2021, 14, 5299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, J.R.; Novais, R.M.; Hotza, D.; Labrincha, J.A.; Senff, L. Waste-derived geopolymers for artificial coral development by 3d printing. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Wang, F.; He, X.; Hu, X. Resistance and durability of fly ash based geopolymer for heavy metal immobilization: Properties and mechanism. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 12580–12592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazan, P.; Figiela, B.; Kozub, B.; Łach, M.; Mróz, K.; Melnychuk, M.; Korniejenko, K. Geopolymer foam with low thermal conductivity based on industrial waste. Materials 2024, 17, 6143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denker, M.; Gharehpapagh, B.; Gruhn, R.; Pose, S.; Korniejenko, K.; Grab, T.; Zeidler, H. Compressive strength of geopolymer with recycled carbon fibres manufactured in air and in water by casting and additive manufacturing. Front. Built Environ. 2025, 11, 1620385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliwa, K.; Kozub, B.; Łoś, K.; Łoś, P.; Korniejenko, K. Assessment of durability and degradation resistance of geopolymer composites in water environments. Materials 2025, 18, 3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duxson, P.; Fernández-Jiménez, A.; Provis, J.L.; Lukey, G.C.; Palomo, A.; van Deventer, J.S.J. Geopolymer technology: The current state of the art. J. Mater. Sci. 2007, 42, 2917–2933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onyelowe, K.C.; Kamchoom, V.; Ebid, A.M.; Hanandeh, S.; Llamuca, J.L.L.; Yachambay, F.P.L.; Palta, J.L.A.; Vishnupriyan, M.; Avudaiappan, S. Optimizing the utilization of metakaolin in pre-cured geopolymer concrete using ensemble and symbolic regressions. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 6858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Işıkdağ, B.; Yalghuz, M.R. Strength development and durability of metakaolin geopolymer mortars containing pozzolans under different curing conditions. Minerals 2023, 13, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qaidi, S.; Najm, H.M.; Abed, S.M.; Ahmed, H.U.; Dughaishi, H.A.; Lawati, J.A.; Sabri, M.M.; Alkhatib, F.; Milad, A. Fly ash-based geopolymer composites: A review of the compressive strength and microstructure analysis. Materials 2022, 15, 7098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaurav, G.; Kandpal, S.C.; Mishra, D.; Kotoky, N. A comprehensive review on fly ash-based geopolymer: A pathway for sustainable future. J. Sustain. Cem.-Based Mater. 2024, 13, 100–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, I.; Abdelkhalik, A.; Mayhoub, O.A.; Kohail, M. Development of sustainable slag-based geopolymer concrete using different types of chemical admixtures. Int. J. Concr. Struct. Mater. 2024, 18, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, H.S. Durability of slag-based alkali-activated materials: A critical review. J. Aust. Ceram. Soc. 2024, 60, 885–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Karim, M.R.; Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M.N.; Zain, M.F.M. Durability of mortar and concrete containing alkali-activated binder with pozzolans: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 93, 95–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, T.; Luo, H.; Han, R.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, M.; Gui, Z.; Xing, J.; Chen, D.; He, B.-J. Red mud in combination with construction waste red bricks for the preparation of low-carbon binder materials: Design and material characterization. Buildings 2024, 14, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.; Cai, X.; Ou, X.; Zhao, X.; Wei, D.; Wang, S.; Luo, Q.; Huang, Y. Study on the heavy metal immobilization mechanism in the alkali-activated red mud-ground granulated blast furnace slag-based geopolymer. Matéria 2025, 30, e20240776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, N.; Chen, Z.; Gao, Z.; Song, X. The effect of copper slag as a precursor on the mechanical properties, shrinkage and pore structure of alkali-activated slag-copper slag mortar. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Chen, L. A review of the influence of copper slag on the properties of cement-based materials. Materials 2022, 15, 8594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maqbool, Q.; Mobili, A.; Blasi, E.; Sabbatini, S.; Ruello, M.L.; Tittarelli, F. Sustainable alkali-activated mortars for the immobilization of heavy metals from copper mine tailings. ACS Sustain. Resour. Manag. 2024, 1, 154–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seeni, B.S.; Maheswaran, C.; Nakarajan, A. Effect of copper slag addition on the properties of ambient cured alkali-activated pervious concrete. Road Mater. Pavement Des. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swaminathen, A.N.; Kumar, C.V.; Ravi, S.R.; Debnath, S. Evaluation of strength and durability assessment for the impact of rice husk ash and metakaolin at high performance concrete mixes. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 47, 4584–4591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moulick, K.K.; Shiuly, A.; Bhattacharjya, S.; Sau, D. Optimization of rice husk ash-based alkali activated composites (aac) blended with bauxite and ggbs for sustainable building materials. Discov. Civ. Eng. 2024, 1, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becher, A.F.; Zeidler, H.; Gądek, S.; Korniejenko, K. Shaping and characterization of additively manufactured geopolymer materials for underwater applications. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pn-en 12457-2:2006; Characterisation of Waste—Leaching—Compliance Test for Leaching of Granular Waste Materials and Sludges—Part 2: One Stage Batch Test at a Liquid to Solid Ratio of 10 l/kg for Materials with Particle Size Below 4 mm (Without or With Size Reduction). European Standard: Brussels, Belgium, 2006.

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Gospodarki z Dnia 16 Lipca 2015 r. w Sprawie Dopuszczania Odpadów do skłAdowania na skłAdowiskach. Dziennik Ustaw 2015, poz. 1277. 2015. Available online: https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20150001277/O/D20151277.pdf (accessed on 21 October 2025).

- European Commission, Radiation Protection Unit. Radiological Protection Principles Applicable to the Natural Radioactivity of Building Materials; Technical Report 112, “RP 112” Guidance for Screening Levels (Activity Concentration Index) in Building Materials. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities: Luxemburg, 1999.

- Salazar, P.A.; Fernández, C.L.; Luna-Galiano, Y.; Sánchez, R.V.; Fernández-Pereira, C. Physical, mechanical and radiological characteristics of a fly ash geopolymer incorporating titanium dioxide waste as passive fire insulating material in steel structures. Materials 2022, 15, 8493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houhou, M.; Leklou, N.; Ranaivomanana, H.; Penot, J.D.; de Barros, S. Geopolymers in nuclear waste storage and immobilization: Mechanisms, applications, and challenges. Discov. Appl. Sci. 2025, 7, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, E.; Choo, T.F.; Khairuddin, N.W.A.; Abdel Rahman, R.O. On the sustainable utilization of geopolymers for safe management of radioactive waste: A review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pławecka, K.; Bazan, P.; Lin, W.; Korniejenko, K.; Sitarz, M.; Nykiel, M. Development of geopolymers based on fly ashes from different combustion processes. Polymers 2022, 14, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Geopolymer Type | Properties | Applications | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metakaolin | High amorphous Si/Al content; rapid hardening and high early strength; excellent chemical durability; low shrinkage; predictable setting and consistent workability. | Precast elements, structural repair, chemically resistant underwater binders. | [22,23,24] |

| Fly Ash | Class F: low-Ca, forms N-A-S-H gel; Class C: Ca improves early strength but may reduce durability if uncured; variable fresh-state workability; often requires thermal or ambient curing. | Eco-concretes, structural components; limited underwater use without additives. | [25,26] |

| Slag | High CaO content; forms C-A-S-H gel; improves early strength at ambient temperatures; durable in mild seawater and under freeze–thaw cycles; rapid setting and slump loss unless modified with admixtures; enhances mechanical and bond strength; good abrasion resistance. | Marine structures, precast marine components, sewer/infrastructure linings; promising for underwater repairs. | [27,28] |

| Natural Pozzolan | Moderate reactivity; requires NaOH/KOH activation or blending; slower setting and lower early workability; sustainable but with moderate strength and durability. | Rural, earthen, low-carbon construction. | [29] |

| Red Mud | High Fe2O3/Al2O3 ratio; requires strong alkali activation or slag blending; effective for heavy metal immobilization; irregular workability and setting behaviour; durability is formulation-dependent. | Waste stabilization, eco-bricks, confined damping blocks. | [30,31] |

| Copper Slag | High Fe/Si, low Al content; low reactivity; enhances matrix density and abrasion resistance; ambient-cured matrices are compact but have lower strength; requires blending or chemical activation; heavy metal leaching is manageable. | Industrial flooring, abrasion-resistant tiles; cautious use in submerged conditions. | [32,33,34,35] |

| Rice Husk Ash | High amorphous silica content; refines pore structure and increases matrix density; significantly improves compressive strength in optimized blends; reduces workability; accelerates setting; lightweight; durable when combined with ground granulated blast furnace slag or bauxite. | Lightweight marine composites, blended alkali-activated binders. | [36,37] |

| Component | Mixture I (NaOH 16 M) | Mixture II (Baucis + Sand) |

|---|---|---|

| Metakaolin | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Waterglass | 0.90 (NaOH 16 M) | 0.90 (Baucis) |

| Silica | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| Graphite | 0.10 | 0.04 |

| Carbon fibers | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Alginate | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Anhydrite | 0.005 | 0.01 |

| Cellulose | – | 0.01 |

| Sand (<1 mm) | – | 1.00 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Printer model | WASP FOR 40100 CLAY |

| Feeding system | Manual screw-based (without air pressure) |

| Tank shape | Funnel (metal) |

| Nozzle diameter | 4 mm |

| Layer height | 2 mm |

| Print speed | 80 mm/s |

| Infill pattern | Grid (rectilinear) |

| Infill density | 25% |

| Print temperature | Ambient (no heating) |

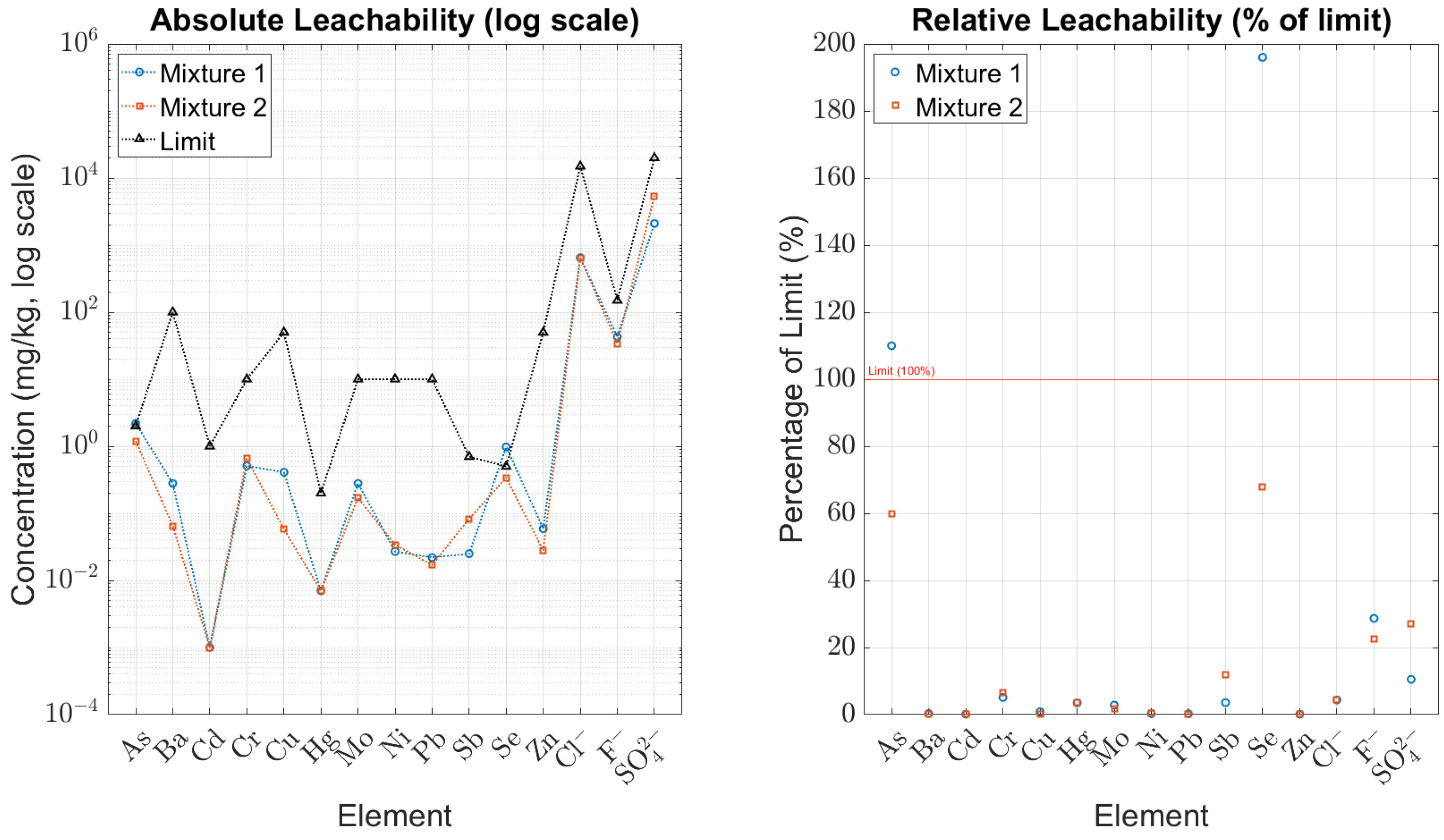

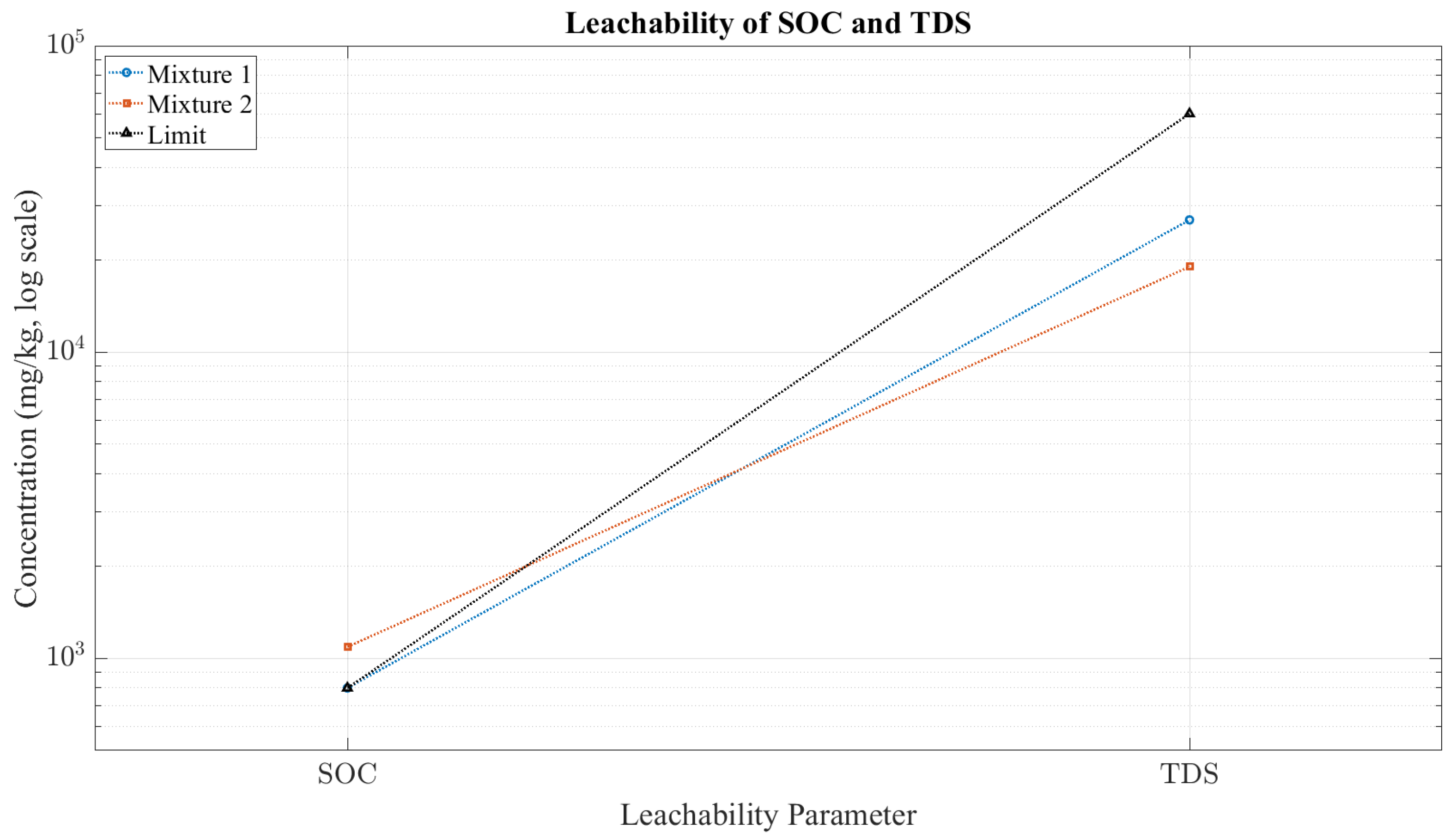

| Characteristic | Mixture I (mg/kg) | Mixture II (mg/kg) | Limit (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic (As) | 2.2 | 1.2 | 2 |

| Barium (Ba) | 0.280 | 0.065 | 100 |

| Cadmium (Cd) | <0.0010 | 0.0010 | 1 |

| Total Chromium (Cr) | 0.510 | 0.660 | 10 |

| Chromium (Cr VI) | 0.32 | 0.31 | – |

| Copper (Cu) | 0.410 | 0.058 | 50 |

| Mercury (Hg) | 0.0070 | <0.0070 | 0.2 |

| Molybdenum (Mo) | 0.280 | 0.170 | 10 |

| Nickel (Ni) | 0.027 | 0.034 | 10 |

| Lead (Pb) | 0.022 | 0.017 | 10 |

| Antimony (Sb) | 0.025 | 0.083 | 0.7 |

| Selenium (Se) | 0.980 | 0.340 | 0.5 |

| Zinc (Zn) | 0.059 | 0.028 | 50 |

| Chlorides | 650 | 650 | 15,000 |

| Fluorides | 43 | 34 | 150 |

| Sulphates | 2100 | 5400 | 20,000 |

| SOC | 800 | 1090 | 800 |

| TDS | 27,000 | 19,000 | 60,000 |

| pH [-] | 11 | 11 | – |

| Mixture | 226Ra (Bq/kg) | 232Th (Bq/kg) | 40K (Bq/kg) | Iac |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mixture I | 56.06 ± 6.22 | 53.79 ± 4.19 | 147.55 ± 2.63 | 0.50 ± 0.04 |

| Mixture II | 42.36 ± 4.93 | 37.95 ± 3.33 | 1192.07 ± 69.27 | 0.72 ± 0.05 |

| Regulatory limit | 300 | 200 | 3000 | ≤1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gharehpapagh, B.; Denker, M.; Gadek, S.; Gruhn, R.; Grab, T.; Korniejenko, K.; Zeidler, H. Geopolymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Chemical Stability, Leaching Behaviour, and Radiological Safety. Materials 2025, 18, 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214886

Gharehpapagh B, Denker M, Gadek S, Gruhn R, Grab T, Korniejenko K, Zeidler H. Geopolymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Chemical Stability, Leaching Behaviour, and Radiological Safety. Materials. 2025; 18(21):4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214886

Chicago/Turabian StyleGharehpapagh, Bahar, Meike Denker, Szymon Gadek, Richard Gruhn, Thomas Grab, Kinga Korniejenko, and Henning Zeidler. 2025. "Geopolymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Chemical Stability, Leaching Behaviour, and Radiological Safety" Materials 18, no. 21: 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214886

APA StyleGharehpapagh, B., Denker, M., Gadek, S., Gruhn, R., Grab, T., Korniejenko, K., & Zeidler, H. (2025). Geopolymer Materials for Additive Manufacturing: Chemical Stability, Leaching Behaviour, and Radiological Safety. Materials, 18(21), 4886. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214886