Experimental Study of Glow Discharge Polymer Film Ablation with Shaped Femtosecond Laser Pulse Trains

Abstract

1. Introduction

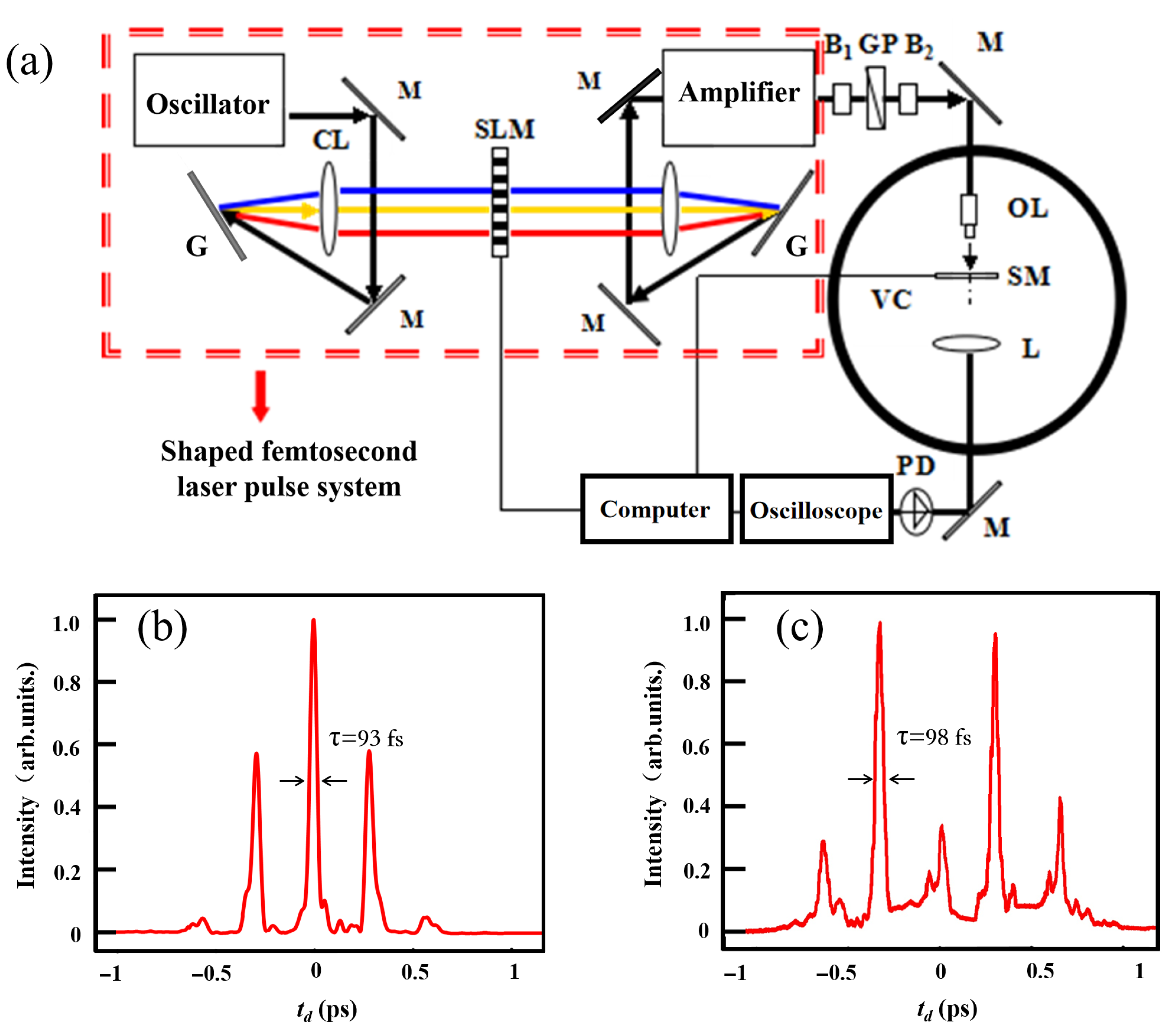

2. Experimental Methods and Setup

3. Results and Discussion

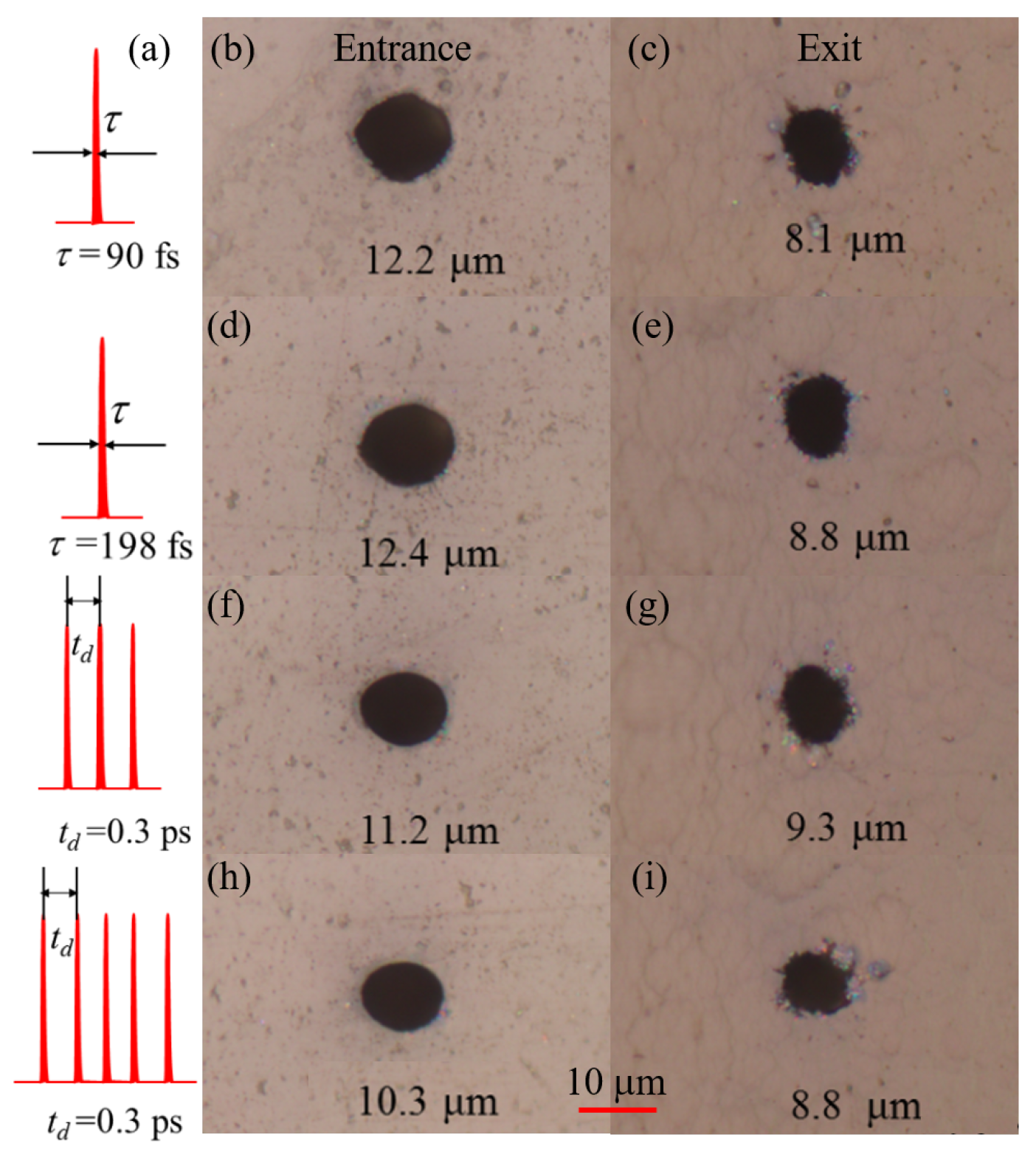

3.1. Influence of Pulse Shape on Laser Processing

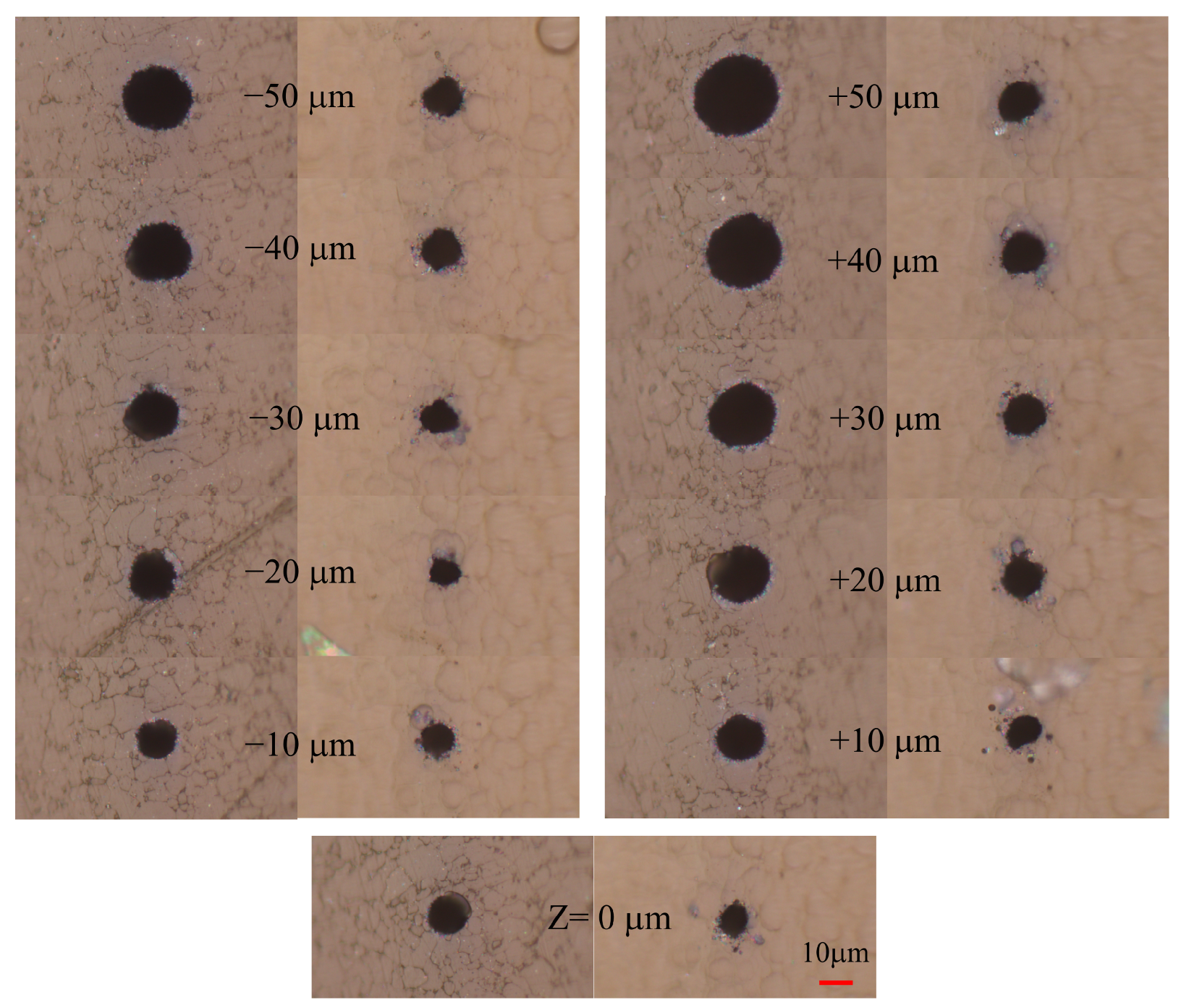

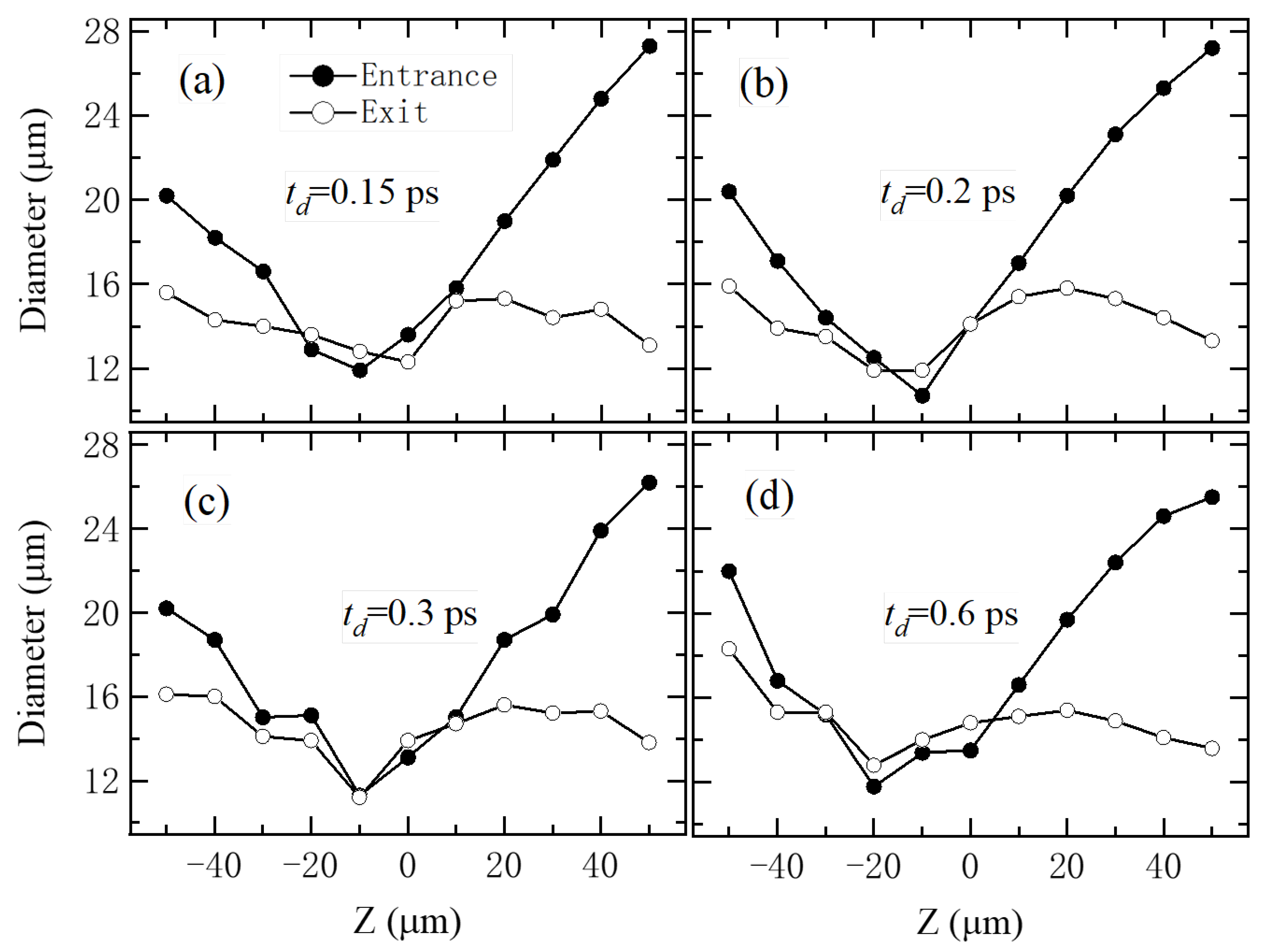

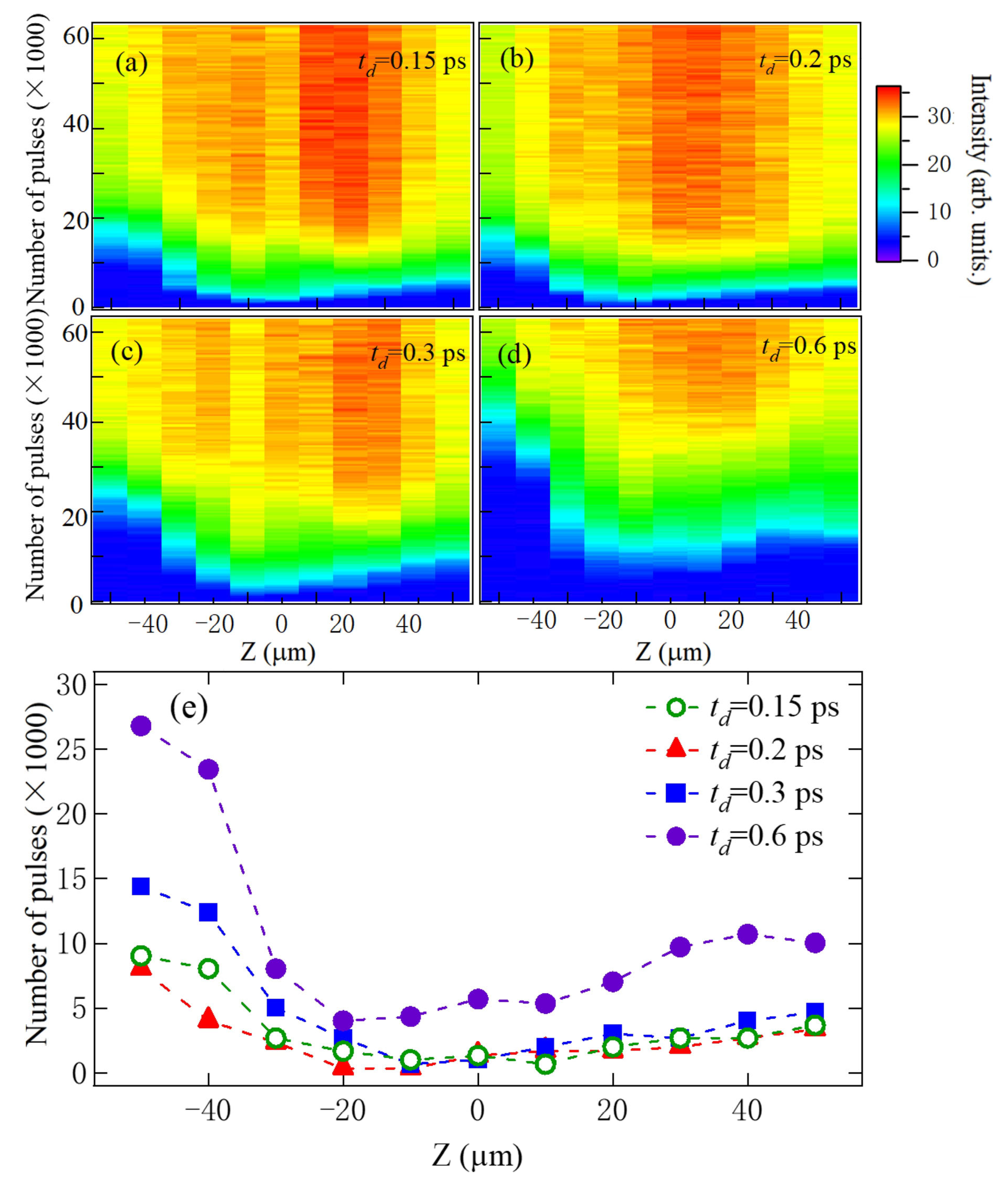

3.2. Effect of Focus Position on Laser Processing

3.3. The Processing Efficiency Under Different Pulse Shapes

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gamaly, E.G.; Rode, A.V.; Luther-Davies, B.; Tikhonchuk, V.T. Ablation of solids by femtosecond lasers: Ablation mechanism and ablation thresholds for metals and dielectrics. Phys. Plasmas 2002, 9, 949–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamlage, G.; Bauer, T.; Ostendorf, A.; Chichkov, B. Deep drilling of metals by femtosecond laser pulses. Appl. Phys. A 2003, 77, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balling, P.; Schou, J. Femtosecond-laser ablation dynamics of dielectrics: Basics and applications for thin films. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2013, 76, 036502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vorobyev, A.Y.; Guo, C. Direct femtosecond laser surface nano/microstructuring and its applications. Laser Photonics Rev. 2013, 7, 385–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmed, K.T.; Grambow, C.; Kietzig, A.M. Fabrication of micro/nano structures on metals by femtosecond laser micromachining. Micromachines 2014, 5, 1219–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gattass, R.R.; Mazur, E. Femtosecond laser micromachining in transparent materials. Nat. Photonics 2008, 2, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugioka, K.; Cheng, Y. Ultrafast lasers—reliable tools for advanced materials processing. Light. Sci. Appl. 2014, 3, e149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimenov, S.; Zavedeev, E.; Jaeggi, B.; Neuenschwander, B. Femtosecond Laser-Induced Periodic Surface Structures in Titanium-Doped Diamond-like Nanocomposite Films: Effects of the Beam Polarization Rotation. Materials 2023, 16, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, H.; Sun, Y.; Fu, X.; Ji, S.; Liao, Y.; Tian, Y. A Review of an Investigation of the Ultrafast Laser Processing of Brittle and Hard Materials. Materials 2024, 17, 3657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautek, W.; Krüger, J. Femtosecond pulse laser ablation of metallic, semiconducting, ceramic, and biological materials. In Proceedings of the Laser Materials Processing: Industrial and Microelectronics Applications, Vienna, Austria, 5–8 April 1994; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 1994; Volume 2207, pp. 600–611. [Google Scholar]

- Duocastella, M.; Arnold, C.B. Bessel and annular beams for materials processing. Laser Photonics Rev. 2012, 6, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.; Velpula, P.K.; Colombier, J.P.; Olivier, T.; Faure, N.; Stoian, R. Single-shot high aspect ratio bulk nanostructuring of fused silica using chirp-controlled ultrafast laser Bessel beams. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 021107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wang, A.D.; Li, B.; Cui, T.H.; Lu, Y.F. Electrons dynamics control by shaping femtosecond laser pulses in micro/nanofabrication: Modeling, method, measurement and application. Light. Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 17134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, A.; Li, S.; Qi, H.; Qi, Y.; Hu, Z.; Jin, M. Influence of ambient pressure on the ablation hole in femtosecond laser drilling Cu. Appl. Opt. 2015, 54, 8235–8240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, Z.; Feng, J.; Tian, Z.; Yang, B.; Dong, X.; Xu, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y. Fabrication of artificial microstructure arrays with low surface reflectivity on ZnS by femtosecond laser direct writing. Appl. Phys. A 2025, 131, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badea, L.; Duta, L.; Mihailescu, C.; Oane, M.; Trefilov, A.; Popescu, A.; Hapenciuc, C.; Mahmood, M.; Ticos, D.; Mihailescu, N.; et al. Ultra-Short Pulses Laser Heating of Dielectrics: A Semi-Classical Analytical Model. Materials 2024, 17, 5366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, Y.; Qi, H.; Chen, A.; Hu, Z. Improvement of aluminum drilling efficiency and precision by shaped femtosecond laser. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 317, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, H.; Lian, Z.; Fei, D.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Z. Manipulation of matter with shaped-pulse light field and its applications. Adv. Phys. X 2021, 6, 1949390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y.; Qi, H.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Z.; Hu, Z. The influence of double pulse delay and ambient pressure on femtosecond laser ablation of silicon. Opt. Laser Technol. 2015, 66, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, D.; Sharafudeen, K.N.; Yue, Y.; Qiu, J. Femtosecond laser induced phenomena in transparent solid materials: Fundamentals and applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2016, 76, 154–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Qi, H.; Zhao, L.; Liu, X.; Lian, Z.; Tong, Q.; He, J.; Jin, C.; Li, J.; Bo, J.; et al. Control of ablation morphology on Cu film with tailored femtosecond pulse trains. Appl. Phys. A 2020, 126, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noël, S.; Hermann, J. Reducing nanoparticles in metal ablation plumes produced by two delayed short laser pulses. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 94, 053120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singha, S.; Hu, Z.; Gordon, R.J. Ablation and plasma emission produced by dual femtosecond laser pulses. J. Appl. Phys. 2008, 104, 113520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Luo, S.; Chen, Z.; Qi, H.; Deng, J.; Hu, Z. Drilling of aluminum and copper films with femtosecond double-pulse laser. Opt. Laser Technol. 2016, 80, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Song, G.; Huang, S.; Xu, J. Highly uniform fabrication of femtosecond-laser-modified silicon materials enabled by temporal pulse shaping. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2024, 124, 101601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lei, H.; Li, J.; Lin, W.; Qi, X.; Tang, Y.; Liu, Y. Characterization of inertial confinement fusion targets using X-ray phase contrast imaging. Opt. Commun. 2014, 332, 9–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfonso, N.; Carlson, L.C.; Bunn, T.L. Planarization of Isolated Defects on ICF Target Capsule Surfaces by Pulsed Laser Ablation. Fusion Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ni, H.; Lu, M.; Liu, Z.; Huang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Y. A measurement method for three-dimensional inner and outer surface profiles and spatial shell uniformity of laser fusion capsule. Opt. Laser Technol. 2021, 134, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamann, C.; Kampfrath, G. Glow discharge polymeric films: Preparation, structure, properties and applications. Vacuum 1984, 34, 1053–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ai, X.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, T.; Huang, J.; Li, J.; He, Z.; He, X. Surface morphology and chemical microstructure of glow discharge polymer films prepared by plasma enhanced chemical vapor deposition at various Ar/H2 ratios. Vacuum 2022, 202, 111142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.C.; Johnson, M.A.; Bunn, T.L. Surface Modification of ICF Target Capsules by Pulsed Laser Ablation. Fusion Sci. Technol. 2016, 70, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez-Rueda, J.; Götte, N.; Siegel, J.; Soccio, M.; Zielinski, B.; Sarpe, C.; Wollenhaupt, M.; Ezquerra, T.A.; Baumert, T.; Solis, J. Nanofabrication of tailored surface structures in dielectrics using temporally shaped femtosecond-laser pulses. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 6613–6619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Qi, H.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Tong, Q.; Lian, Z.; Li, J.; Bo, J.; Fei, D.; Chen, Z.; et al. Ultrafast dynamics control on ablation of Cu using shaped femtosecond pulse trains. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2021, 26, 49–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guay, J.; Villafranca, A.; Baset, F.; Popov, K.; Ramunno, L.; Bhardwaj, V. Polarization-dependent femtosecond laser ablation of poly-methyl methacrylate. New J. Phys. 2012, 14, 085010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, A.M. Femtosecond pulse shaping using spatial light modulators. Rev. Sci. Instruments 2000, 71, 1929–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, A.M. Ultrafast optical pulse shaping: A tutorial review. Opt. Commun. 2011, 284, 3669–3692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozovoy, V.V.; Pastirk, I.; Dantus, M. Multiphoton intrapulse interference. IV. Ultrashort laser pulse spectral phase characterization and compensation. Opt. Lett. 2004, 29, 775–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Gunn, J.M.; Cruz, J.M.D.; Lozovoy, V.V.; Dantus, M. Quantitative investigation of the multiphoton intrapulse interference phase scan method for simultaneous phase measurement and compensation of femtosecond laser pulses. JOSA B 2006, 23, 750–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.; Venkatkrishnan, K.; Sivakumar, N.; Gan, G. Laser drilling of thick material using femtosecond pulse with a focus of dual-frequency beam. Opt. Laser Technol. 2003, 35, 199–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Tang, X.; Wang, H.; Li, J.; Wang, W.; Cai, J.; Zhang, J.; San, X.; Zhao, X.; Ma, P.; et al. Efficient generation of Bessel-Gauss attosecond pulse trains via nonadiabatic phase-matched high-order harmonics. Light. Sci. Appl. 2025, 14, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Mao, X.; Greif, R.; Russo, R. Experimental investigation of ablation efficiency and plasma expansion during femtosecond and nanosecond laser ablation of silicon. Appl. Phys. A 2005, 80, 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loktionov, E.Y.; Ovchinnikov, A.; Protasov, Y.Y.; Protasov, Y.S.; Sitnikov, D. Energy efficiency of femtosecond laser ablation of polymer materials. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 2012, 79, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domke, M.; Matylitsky, V.; Stroj, S. Surface ablation efficiency and quality of fs lasers in single-pulse mode, fs lasers in burst mode, and ns lasers. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 505, 144594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristoforetti, G.; Lorenzetti, G.; Benedetti, P.; Tognoni, E.; Legnaioli, S.; Palleschi, V. Effect of laser parameters on plasma shielding in single and double pulse configurations during the ablation of an aluminium target. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2009, 42, 225207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Xu, W.; Wang, X.; Shi, D.; Wang, J.; Zhao, L.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, J.; Hu, Z. Experimental Study of Glow Discharge Polymer Film Ablation with Shaped Femtosecond Laser Pulse Trains. Materials 2025, 18, 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204761

Wang Q, Xu W, Wang X, Shi D, Wang J, Zhao L, Cui Y, Zhang M, Liu J, Hu Z. Experimental Study of Glow Discharge Polymer Film Ablation with Shaped Femtosecond Laser Pulse Trains. Materials. 2025; 18(20):4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204761

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qinxin, Weiwei Xu, Xue Wang, Dandan Shi, Jingyuan Wang, Liyan Zhao, Yasong Cui, Mingyu Zhang, Jia Liu, and Zhan Hu. 2025. "Experimental Study of Glow Discharge Polymer Film Ablation with Shaped Femtosecond Laser Pulse Trains" Materials 18, no. 20: 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204761

APA StyleWang, Q., Xu, W., Wang, X., Shi, D., Wang, J., Zhao, L., Cui, Y., Zhang, M., Liu, J., & Hu, Z. (2025). Experimental Study of Glow Discharge Polymer Film Ablation with Shaped Femtosecond Laser Pulse Trains. Materials, 18(20), 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204761