Physical and Mechanical Performance of Mortar with Rice Husk Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Partial Cement Replacement

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

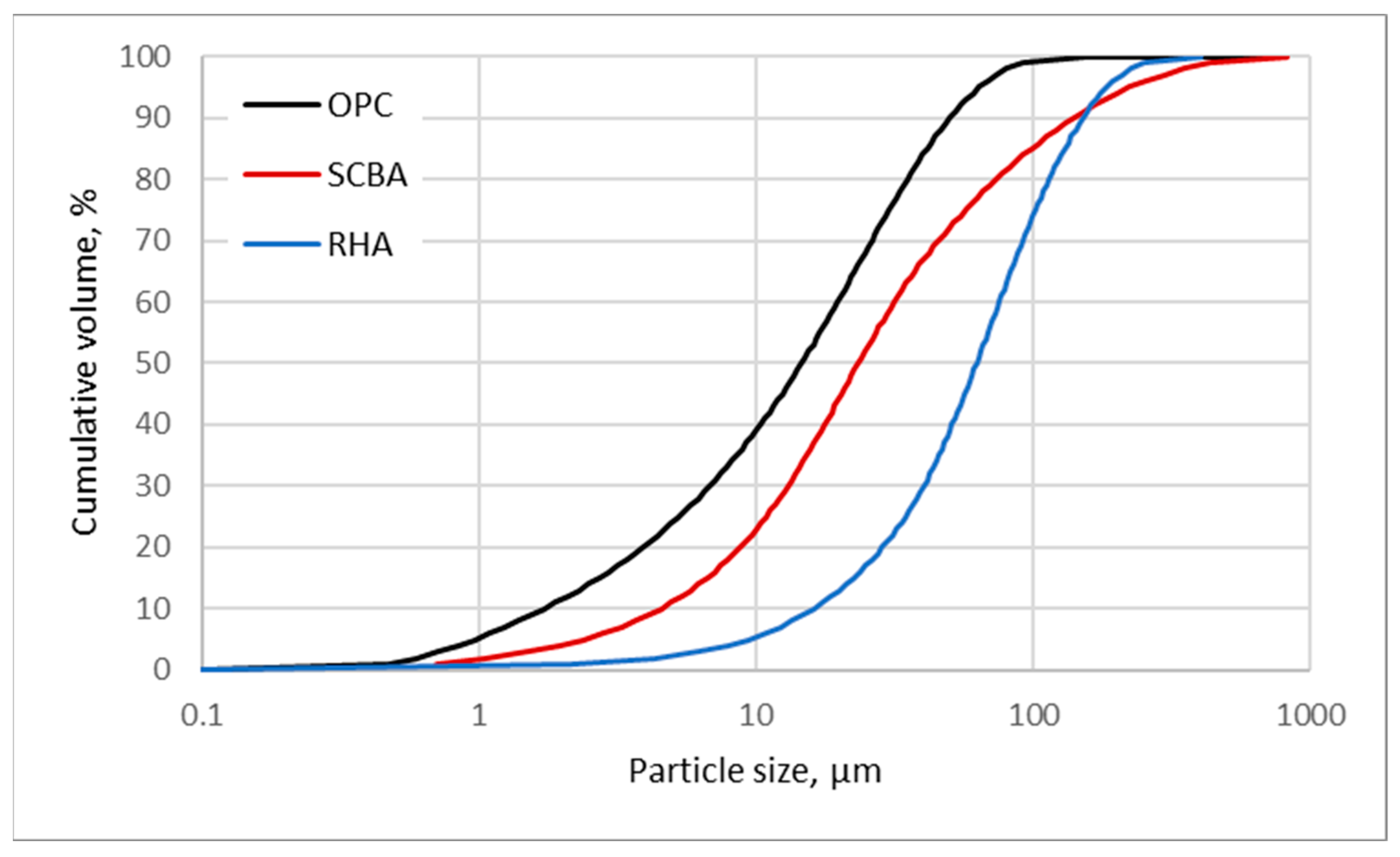

2.1. Materials

2.2. Test Methods

2.2.1. Properties of Fresh Mortar

2.2.2. Properties of Hardened Mortar

2.2.3. Microstructural Parameters

3. Results and Discussion

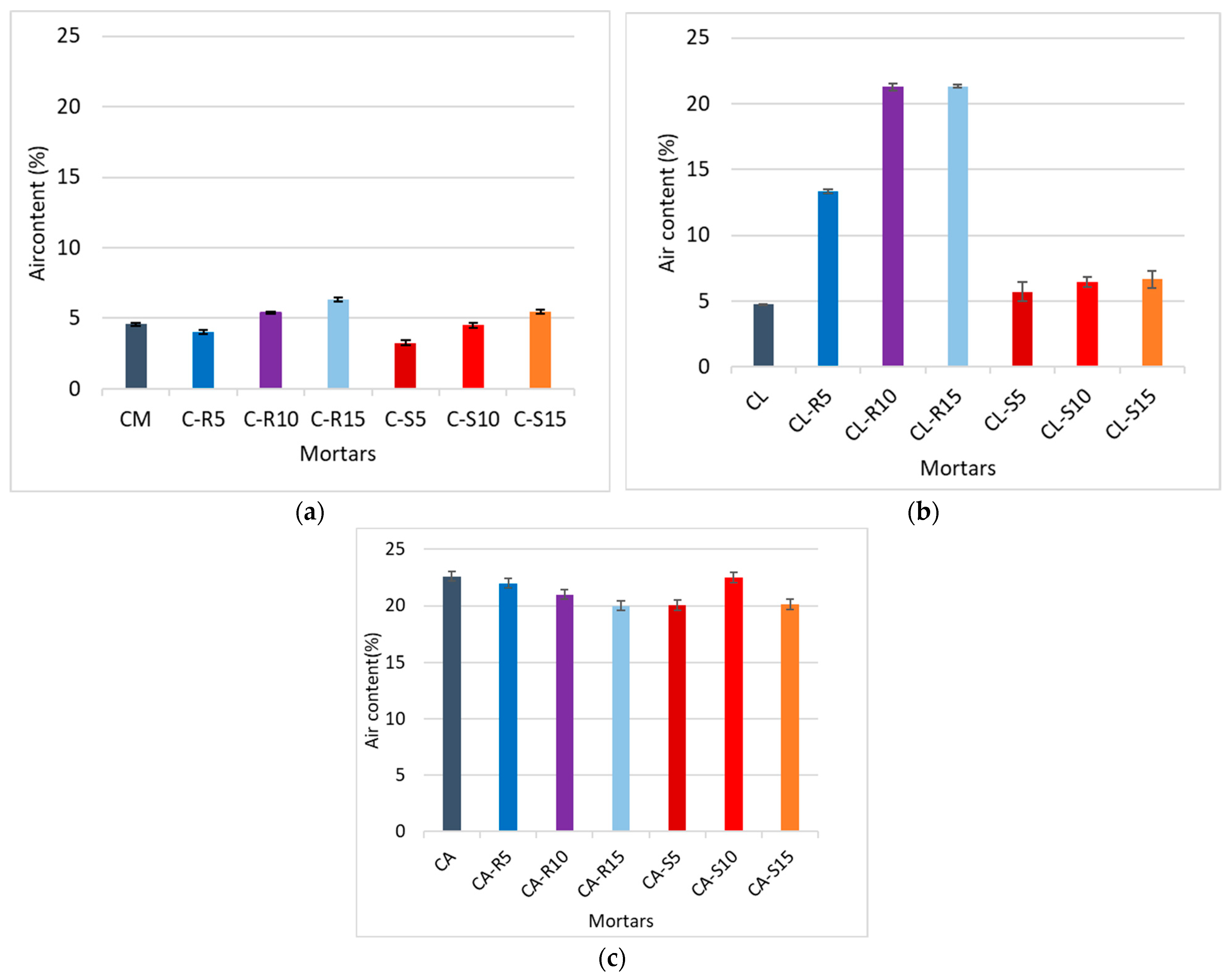

3.1. Air Content Analysis

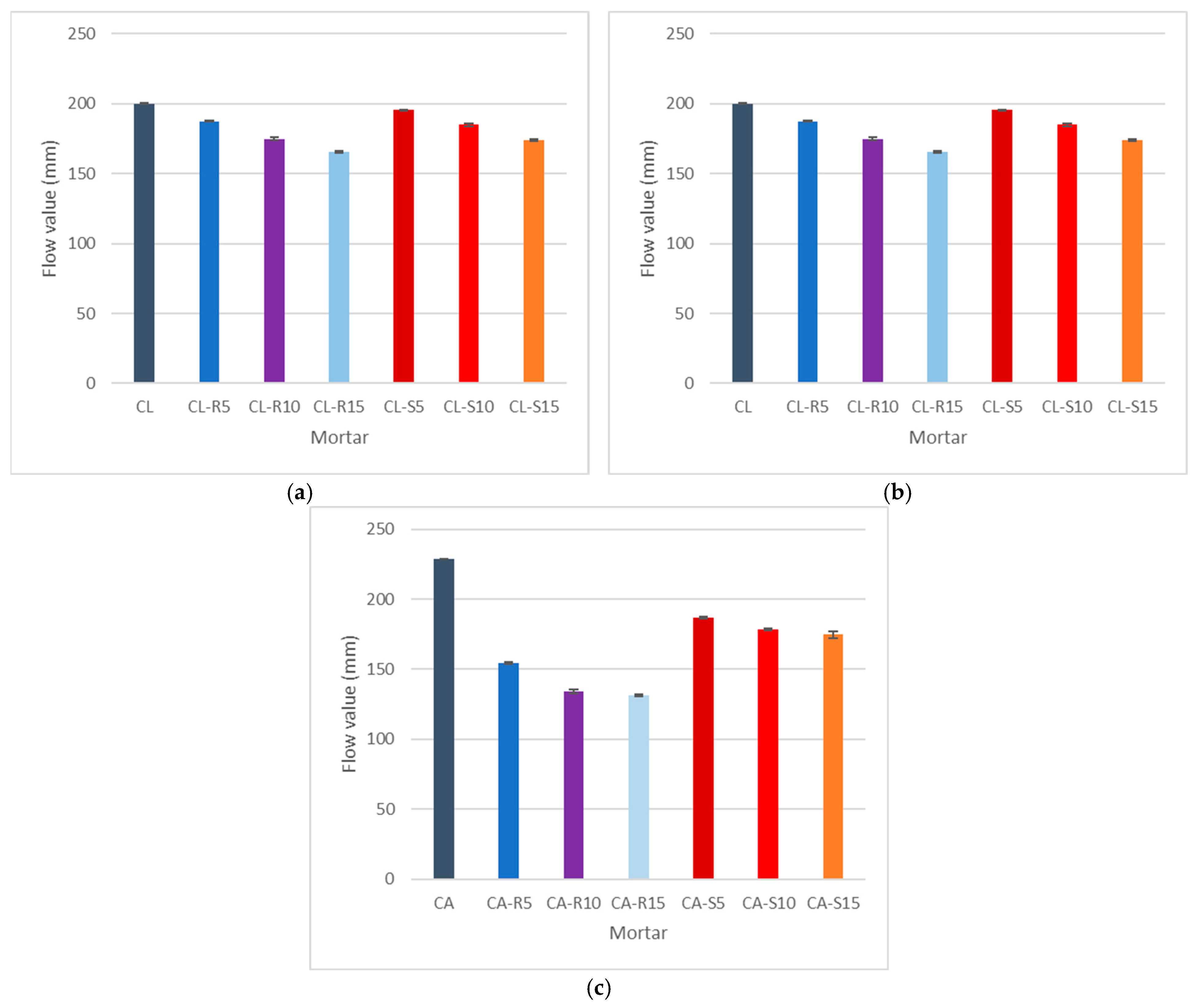

3.2. Consistency Analysis

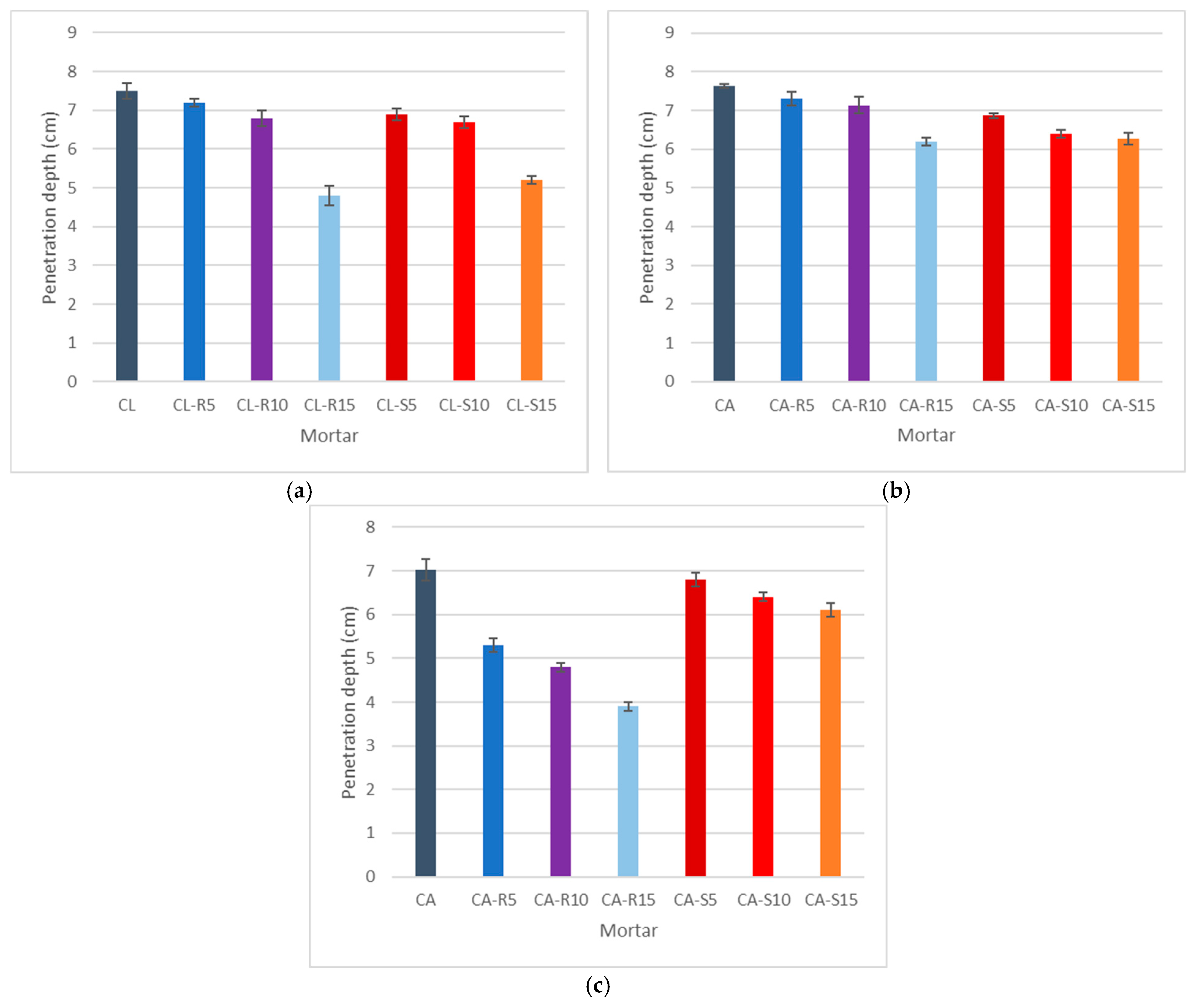

3.3. Compressive Strength

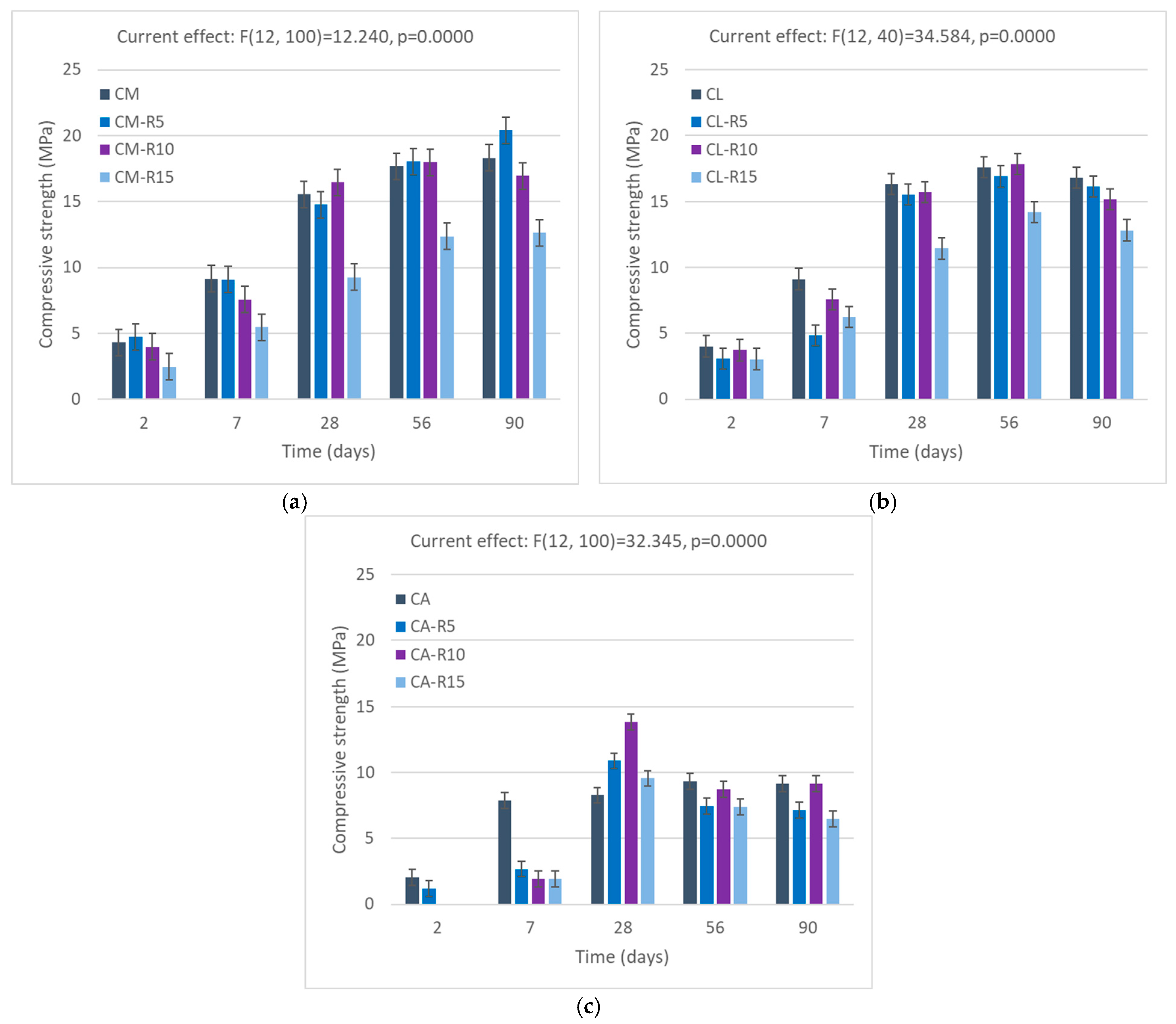

3.3.1. Compressive Strength of Mortars with RHA Addition

3.3.2. Compressive Strength of Mortars with SCBA Addition

3.4. Flexural Strength Analysis

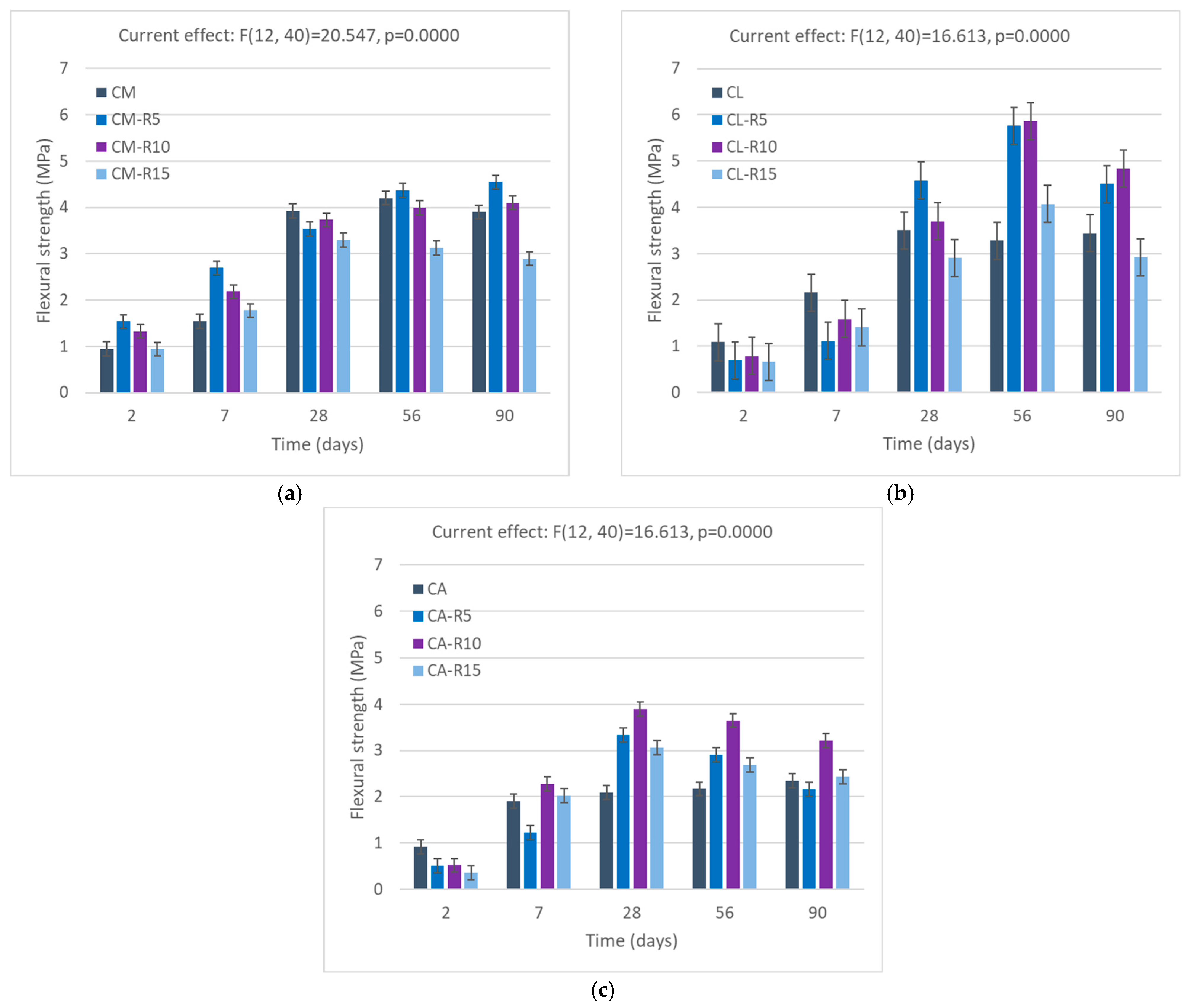

3.4.1. Flexural Strength of Mortars with RHA Addition

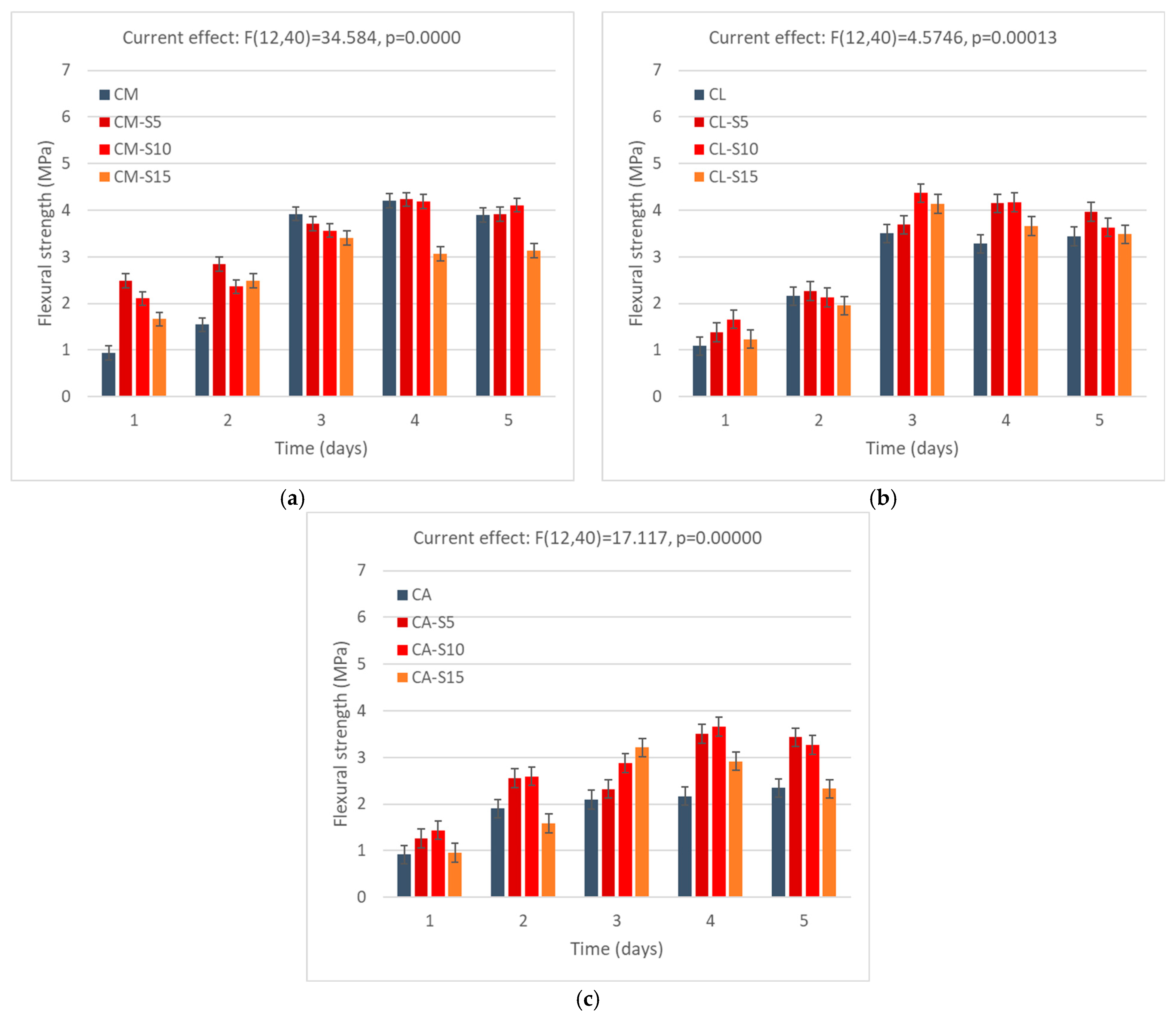

3.4.2. Flexural Strength of Mortars with SCBA Addition

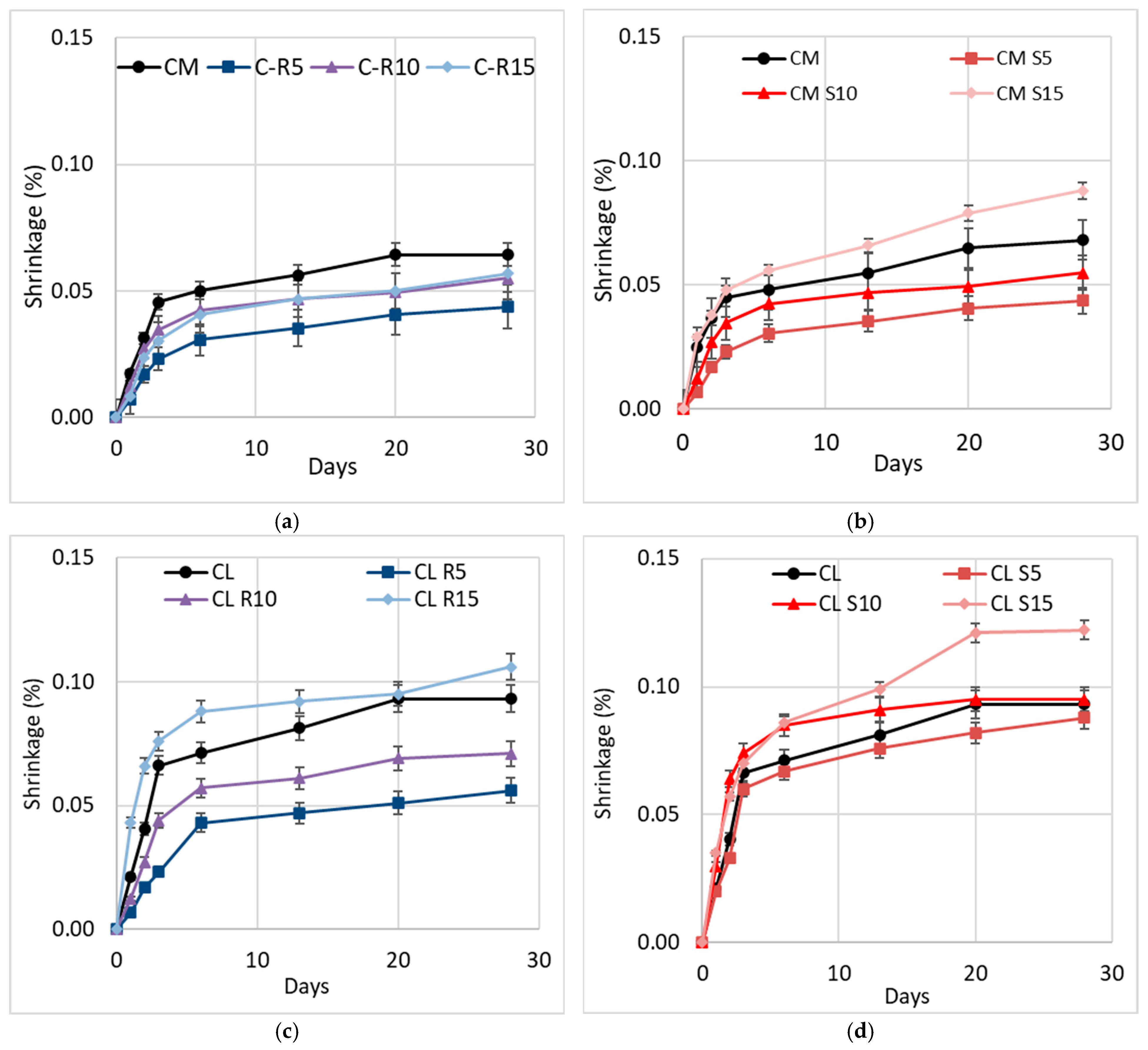

3.5. Drying Shrinkage of Mortars

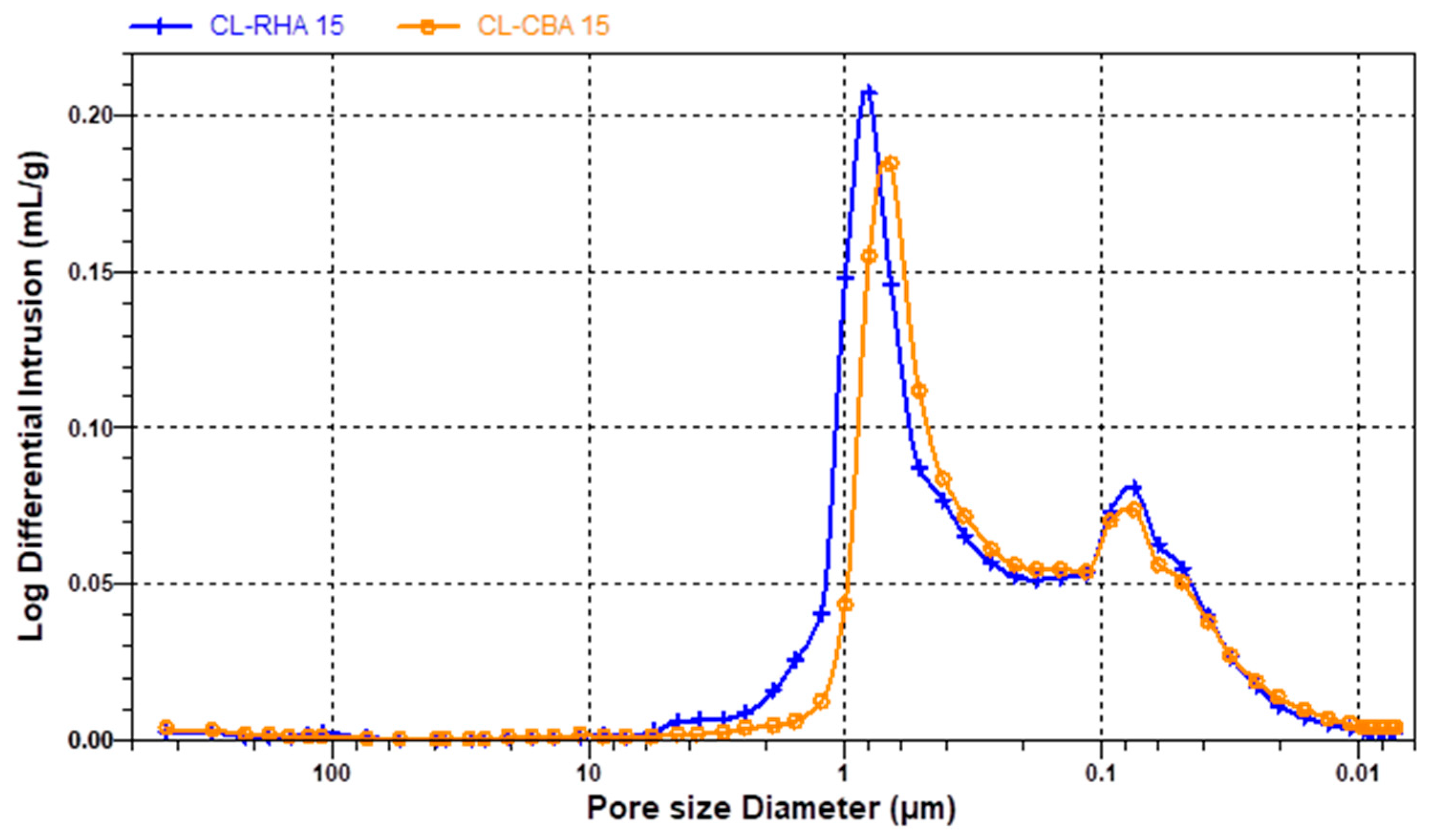

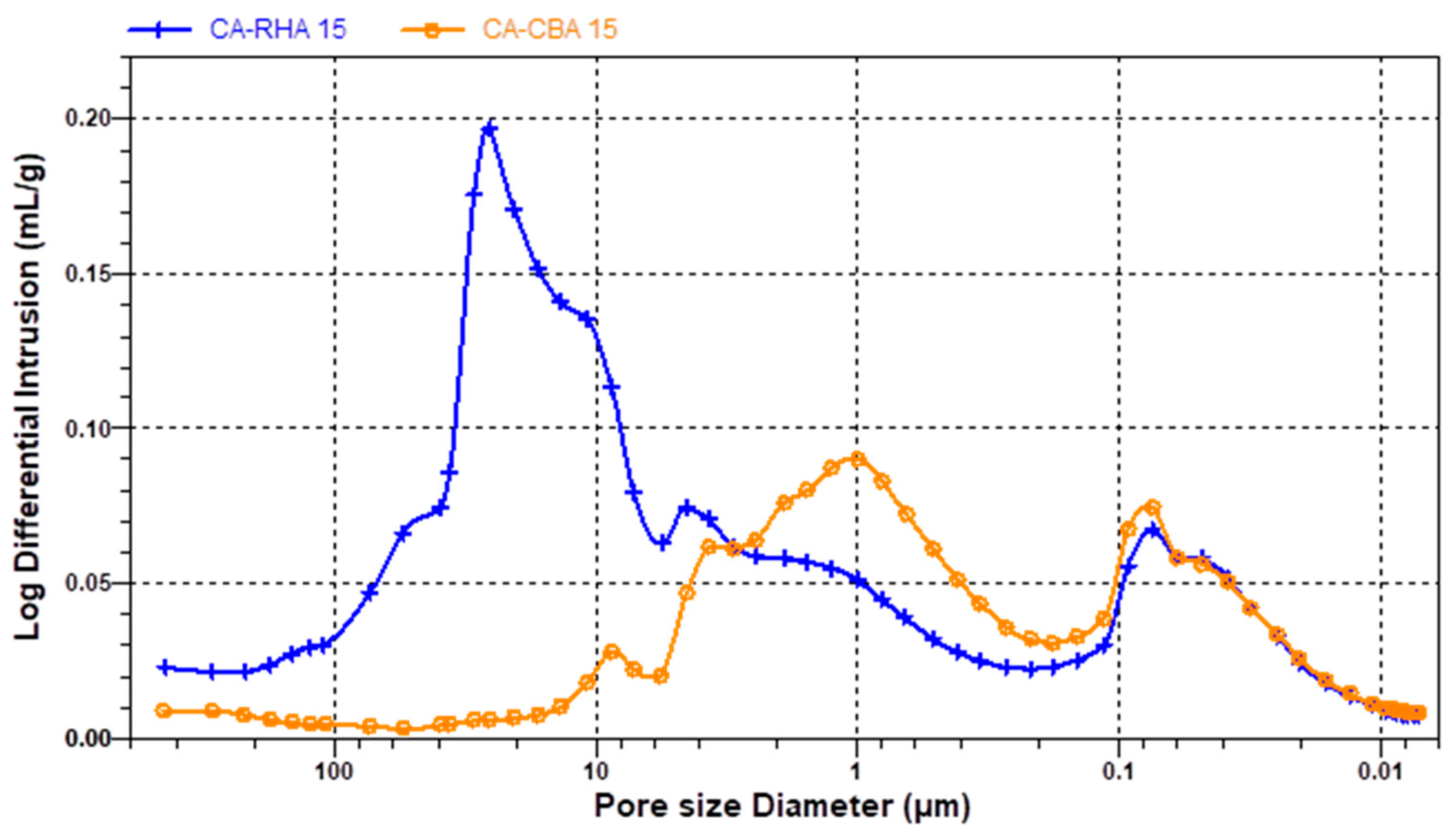

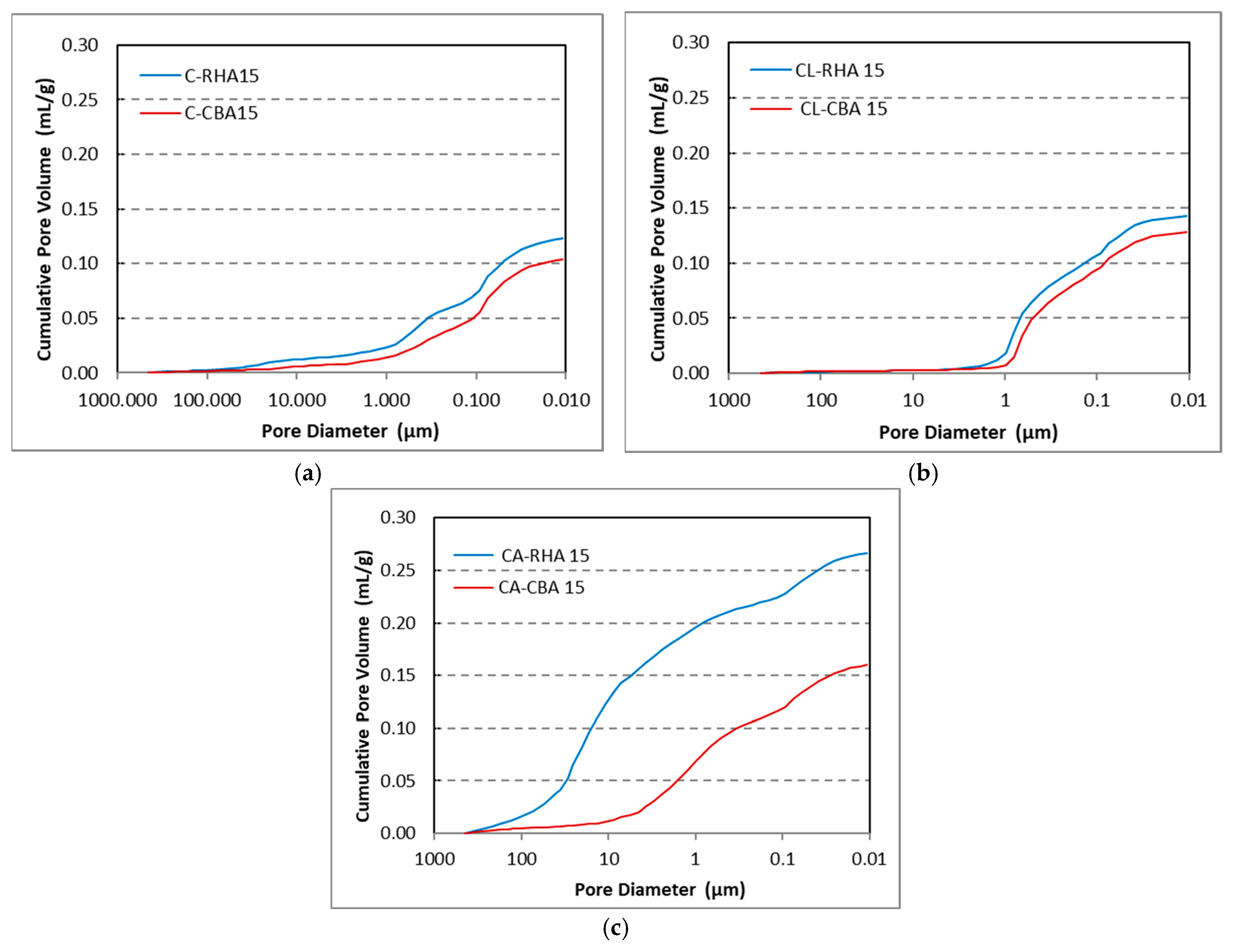

3.6. MIP Pore Structure Analysis

3.7. SEM Analysis Results

4. Conclusions

- Air content was affected to a small degree by the presence of SCBA and RHA, and the air content generally increased with the increase in SCM content. This may be due to the irregular shapes of the grains. In APA mortar samples, air voids arose due to the aerating effect of the admixture, and in this case no significant effect of the SCMs could be observed, possibly due to the large amount of air voids offsetting the issues caused by the shape of grains and changes in consistency.

- The consistency by flow table analysis showed that replacement of 15% decreased the flow values of mixtures for both RHA and SCBA by 10% and 12% in cement mortar, 20% and 15% for cement–lime mortar, and 40% and 22% for APA cement mortar, respectively. Similar results were obtained for Novikov’s cone test. This effect may be linked to the fact that SCM addition increases the water demand on mixtures.

- RHA addition to cement mortar enhanced the compressive strength by up to 15% at 90 days. In cement–lime samples, strength increased slightly at 56 days, then decreased in the remaining days, which may possibly be a result of delayed shrinkage strains. In APA samples, RHA addition improved compressive strength by up to 50%. Flexural strength of mortars with RHA was higher than that of the reference sample; however, after 28 days their strength was comparable. In case of lime mortars, the early strength or mortar with RHA was lower than that of the reference sample, but comparable or higher at later dates. In the APA sample, the RHA showed a significant improvement in strength even with a higher replacement amount of 15%. The positive effect of RHA on strength can be attributed to the filler effect and pozzolanic reaction of RHA.

- SCBA outperformed RHA in compressive strength of cement mortar. SCBA increased the strength of cement mortars; however, with cement–lime mortar, the compressive strength of samples with RHA remained lower until 56 days. Surprisingly, the RHA addition increased strength for APA mortars by 25%, 55%, and 40% at 5%, 10%, and 15% replacement rates. SCBA increased the flexural strength of cement mortar by 50% to 48%, 35% to 40%, and 25% to 28% with replacement by 5%, 10%, and 15% at 2 and 7 days. Strength dropped by 20% with increased replacement. In case of SCBA replacement in cement–lime mortar, an increase of flexural strength occurred. The SCBA in APA samples increased flexural strength.

- RHA replacement decreased dry shrinkage by up to 35%. SCBA additions of 10% and 15% reduced the shrinkage. Those effects may be attributed to the excess water in the mortar being absorbed on SCM grains and then released.

- Adding RHA increased the pore size (0.5–1 µm) in cement mortar and by a higher amount in cement–lime mortar in comparison to the SCBA additive. Additionally, APA increased the pore size (1–30 µm) in mortar with the RHA additive. MIP results indicated a greater share of pores with smaller diameters for the SCBA additive, which translated into higher strength results but also a tendency towards greater shrinkage in comparison with the RHA additive, possibly due to differences in the morphology of the ash particles.

- The SEM examination results showed that bagasse ash mortar, especially with lime, had a finer microstructure and was less porous than mortar with the RHA additive. In case of the APA-containing cement mortar, the microstructure was more porous due to larger voids. Mortar containing lime and biomass ash had a homogenous structure with fewer pores, which helped improve its strength.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kimbonguila, A.; Matos, L.; Petit, J.; Scher, J.; Nzikou, J.-M. Effect of Physical Treatment on the Physicochemical, Rheological and Functional Properties of Yam Meal of the Cultivar ‘Ngumvu’ from Dioscorea alata L. of Congo. Int. J. Recent Sci. Res. 2019, 9, 25083–25086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hn, S.; Deotale, A.R.; Sathawane, R.S. Effect of Partial Replacement of Cement by Fly Ash, Rice Husk Ash with Using Steel Fiber in Concrete. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res. 2012, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Bui, D.D.; Hu, J.; Stroeven, P. Particle size effect on the strength of rice husk ash blended gap-graded Portland cement concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 27, 357–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad Allah Mohamed, Y. Effects of Sugarcane’s Bagasse Ash Additive on Portland Cement Properties. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. Res. 2017, 3, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bie, R.-S.; Song, X.-F.; Liu, Q.-Q.; Ji, X.-Y.; Chen, P. Studies on effects of burning conditions and rice husk ash (RHA) blending amount on the mechanical behavior of cement. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 55, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.H.; Lastra, R.; Malhotra, V.M. Rice-husk ash paste and concrete: Some aspects of hydration and the microstructure of the interfacial zone between the aggregate and paste. Cem. Concr. Res. 1996, 26, 963–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, M.; Khan, M.N.; Karim, M.R.; Kaish, A.B.; Zain, M.F. Physical and chemical contributions of Rice Husk Ash on the properties of mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 128, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, J.S.; Papadakis, V.G. Rice Husk Ash—Importance of Fineness for its Use as a Pozzolanic and Chloride-Resistant Material. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference o Durability of Building Materials ad Components, Porto, Portugal, 12–15 April 2011; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Q.-G.; Lin, Q.-Y.; Yu, Q.-J.; Zhao, S.-Y.; Yang, L.-F.; Sugita, S. Concrete with highly active rice husk ash. J. Wuhan Univ. Technol. Mat. Sci. Edit. 2004, 19, 74–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Rice husk ash blended cement: Assessment of optimal level of replacement for strength and permeability properties of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2008, 22, 1675–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, I.M.T.; Figueiredo, S.S.; De Carvalho, J.B.Q.; Neves, G.A.; De Souza, J.; Menezes, R.R. Coating mortar using rice husk ash as binding. Mater. Sci. Forum 2012, 727–728, 1502–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, H.B.; Hamid, N.A.A.; Chin, K.Y. Production of High Strength Concrete Incorporating an Agricultural Waste-Rice Husk Ash. In Proceedings of the 2010 2nd International Conference on Chemical, Biological and Environmental Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, 2–4 November 2010; pp. 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Das, B.B.; Adak, D.; Rajput, A.; Katare, V. Rice Husk Ash in Structural Concrete: Influence on Strength, Durability and Sustainability. Discov. Concr. Cem. 2025, 1, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.M.S.; Sobuz, M.H.R.; Khan, M.M.H.; Mim, N.J.; Meraz, M.M.; Datta, S.D.; Rana, M.J.; Saha, A.; Akid, A.S.M.; Mehedi, M.T.; et al. Integration of Rice Husk Ash as Supplementary Cementitious Material in the Production of Sustainable High-Strength Concrete. Materials 2022, 15, 8171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Tuan, N.; Ye, G.; Van Breugel, K.; Copuroglu, O. Hydration and Microstructure of Ultra High Performance Concrete Incorporating Rice Husk Ash. Cem. Concr. Res. 2011, 41, 1104–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givi, A.N.; Rashid, S.A.; Aziz, F.N.A.; Salleh, M.A.M. Assessment of the Effects of Rice Husk Ash Particle Size on Strength, Water Permeability and Workability of Binary Blended Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 2145–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.-B.; Kwon, S.-J.; Wang, X.-Y. Analysis of the Effects of Rice Husk Ash on the Hydration of Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 105, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, I.A.; Lopa, A.T.; Angraini, A.; Pertiwi, N.; Taufieq, A.S. Investigation of Mortar Using Rice Husk Ash as Partial Substitution of Porland Composite Cement. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 2022, 19, 20–26. [Google Scholar]

- Le, H.T.; Kraus, M.; Siewert, K.; Ludwig, H.-M. Effect of Macro-Mesoporous Rice Husk Ash on Rheological Properties of Mortar Formulated from Self-Compacting High Performance Concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 80, 225–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, G.A.; Fayyadh, M.M. Rice Husk Ash Concrete: The Effect of RHA Average Particle Size on Mechanical Properties and Drying Shrinkage. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2009, 3, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, H.; Ye, G. Use of Rice Husk Ash for Mitigating the Autogenous Shrinkage of Cement Pastes at Low Water Cement Ratio. In Proceedings of the Ultra-High Performance Concrete and Hgh Performance Construction Materials, Kassel, Germany, 9–11 March 2016; Volume 27, pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yaseen, N. Exploring the Potential of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as a Sustainable Supplementary Cementitious Material: Experimental Investigation and Statistical Analysis. Results Chem. 2024, 10, 101723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dos Santos, F.C.; Silva Américo, R.M. Application of sugarcane bagasse ash in mortars: Systematic literature review. Rev. Tec. 2024, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francioso, V.; Lemos-Micolta, E.D.; Elgaali, H.H.; Moro, C.; Rojas-Manzano, M.A.; Velay-Lizancos, M. Valorization of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as an Alternative SCM: Effect of Particle Size, Temperature-Crossover Effect Mitigation & Cost Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, E.; Clark, M.W.; Lake, N. Sugar cane bagasse ash from a high efficiency co-generation boiler: Applications in cement and mortar production. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 128, 287–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Rajagopal, K.; Thangavel, K. Evaluation of bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2007, 29, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, W.; Ahmad, A.; Ostrowski, K.A.; Aslam, F.; Joyklad, P.; Zajdel, P. Sustainable approach of using sugarcane bagasse ash in cement-based composites: A systematic review. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2021, 15, e00698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, P.; Sachan, A.K.; Singh, R.P. Agro-waste sugarcane bagasse ash (ScBA) as partial replacement of binder material in concrete. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 44, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moraes, J.C.B.; Akasaki, J.L.; Melges, J.L.P.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Soriano, L.; Payá, J.; Tashima, M.M. Assessment of sugar cane straw ash (SCSA) as Pozzolanic material in blended portland cement: Microstructural characterization of pastes and mechanical strength of mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 94, 670–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.-H.; Sheen, Y.-N.; Lam, M.N.-T. Fresh and hardened properties of self-compacting concrete with sugarcane bagasse ash–slag blended cement. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 185, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modani, P.O.; Vyawahare, M.R. Utilization of bagasse ash as a partial replacement of fine aggregate in concrete. Procedia Eng. 2013, 51, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangi, S.A.; Jamaluddin, N.; Wan Ibrahim, M.H.; Abdullah, A.H.; Abdul Awal, A.S.M.; Sohu, S.; Ali, N. Utilization of sugarcane bagasse ash in concrete as partial replacement of cement. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 271, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, F.; Masood, A.; Ali, M. Characterization of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Pozzolan and Influence on Concrete Properties. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 3891–3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chusilp, N.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kiattikomol, K. Utilization of bagasse ash as a pozzolanic material in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 3352–3358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Kawasaki, S.; Achal, V. The Utilization of Agricultural Waste as Agro-Cement in Concrete: A Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Andreão, P.V.; Tavares, L.M. Pozzolanic Properties of Ultrafine Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash Produced by Controlled Burning. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghraby, Y.E.; Talaat, M.; Zenhom, M.; Moussa, R.R.; Salem, S. Utilization of Untreated Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in the Construction Industry. J. Umm Al-Qura Univ. Eng. Archit. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, J.T.; Babafemi, A.J.; Fanijo, E.; Chandra Paul, S.; Combrinck, R. State-of-the-Art Review on the Use of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash in Cementitious Materials. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2021, 118, 103975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.B.; Singh, V.D.; Rai, S. Hydration of Bagasse Ash-Blended Portland Cement. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1485–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossignolo, J.A.; Rodrigues, M.S.; Frias, M.; Santos, S.F.; Junior, H.S. Improved Interfacial Transition Zone between Aggregate-Cementitious Matrix by Addition Sugarcane Industrial Ash. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2017, 80, 157–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi, M.-C. Effects of Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash as a Cement Replacement on Properties of Mortars. Sci. Eng. Compos. Mater. 2012, 19, 279–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade Neto, J.D.S.; De França, M.J.S.; Amorim Júnior, N.S.D.; Ribeiro, D.V. Effects of adding sugarcane bagasse ash on the properties and durability of concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 266, 120959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro, G.C.; Toledo Filho, R.D.; Tavares, L.M.; Fairbairn, E.M.R. Pozzolanic Activity and Filler Effect of Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash in Portland Cement and Lime Mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2008, 30, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malathy, R.; Shanmugam, R.; Chung, I.-M.; Kim, S.-H.; Prabakaran, M. Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Composite Mortars with Lime, Silica Fume and Rice Husk Ash. Processes 2022, 10, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, D.J.; Pama, R.P.; Paul, B.K. Rice Husk Ash-Lime-Cement Mixes for Use in Masonry Units. Build. Environ. 1977, 12, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, J.R. Analysis of Impact of Selected Natural Waste Fibers and Ashes on Properties of Mortars. Ph.D. Thesis, Silesian University of Technology, Gliwice, Poland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- BS EN 998-1:2016; Specification for Mortar for Masonry. Rendering and Plastering Mortar. iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2016.

- Jittin, V.; Minnu, S.N.; Bahurudeen, A. Potential of sugarcane bagasse ash as supplementary cementitious material and comparison with currently used rice husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 273, 121679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Lo, T.Y.; Memon, S.A. Microstructure and reactivity of rich husk ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 29, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Quero, V.G.; Ortiz-Guzmán, M.; Montes-García, P. Durability of mortars containing sugarcane bagasse Ash. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1221, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 197-1:2011; Cement—Part 1: Composition, Specifications and Conformity Criteria for Common Cements. iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2011.

- PN-EN 413-2:2016; Masonry Cement—Part 2: Test Methods. iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2016.

- PN-B-04500; Zaprawy Budowlane. Badanie Cech Fizycznych i Wytrzymałościowych (Construction Mortars. Testing of Physical and Strength Properties). PKN: Warszawa, Poland, 1985. (In Polish)

- EN 1015-3:2000; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonry—Part 3: Determination of Consistence of Fresh Mortar (by Flow Table). iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2000.

- EN 1015-11:2001; Methods of Test for Mortar for Masonary—Part 11: Determination of Flexural and Compressive Strength of Hardened Mortar. iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2001.

- EN 12617-4:2004; Test Methods—Part 4: Determination of Shrinkage and Elongation. iTeh: Newark, DE, USA, 2004.

- Neville, A.M.; Brooks, J.J. Concrete Technology; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-273-75580-7. [Google Scholar]

- Saloni; Parveen; Pham, T.M.; Lim, Y.Y.; Pradhan, S.S.; Jatin; Kumar, J. Performance of Rice Husk Ash-Based Sustainable Geopolymer Concrete with Ultra-Fine Slag and Corn Cob Ash. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 279, 122526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Promsawat, P.; Chatveera, B.; Sua-iam, G.; Makul, N. Properties of self-compacting concrete prepared with ternary Portland cement-high volume fly ash-calcium carbonate blends. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2020, 13, e00426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gołaszewska, M.; Gołaszewski, J.; Bochen, J.; Cygan, G. Comparative Study of Effects of Air-Entraining Plasticizing Admixture and Lime on Physical and Mechanical Properties of Masonry Mortars and Plasters. Materials 2022, 15, 2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, V.-A.; Cloutier, A.; Bissonnette, B.; Blanchet, P.; Duchesne, J. The Effect of Wood Ash as a Partial Cement Replacement Material for Making Wood-Cement Panels. Materials 2019, 12, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulbe, L.; Vitina, I.; Setina, J. The Influence of Cement on Properties of Lime Mortars. Procedia Eng. 2017, 172, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashmi Nayak, J.; Bochen, J.; Gołaszewska, M. Experimental studies on the effect of natural and synthetic fibers on properties of fresh and hardened mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 347, 128550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath Bhowmik, R.; Pal, J. Application of Consistency-Based Water-to-Binder Ratio to Compensate Workability Loss in Concrete Modified with Rice Husk Ash. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 78, 767–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, G.H.M.J.S.; Naveen, P. Effect of rice husk ash and coconut coir fiber on cement mortar: Enhancing sustainability and efficiency in buildings. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 440, 137326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddika, A.; Mamun, M.A.A.; Alyousef, R.; Mohammadhosseini, H. State-of-the-Art-Review on Rice Husk Ash: A Supplementary Cementitious Material in Concrete. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2021, 33, 294–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Antonio, J.S. Evolution of Mechanical Properties and Drying Shrinkage in Lime-Based and Lime Cement-Based Mortars with Pure Limestone Aggregate. Constr. Build. Mater. 2015, 77, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C270; Standard Specificafion for Mortar for Unit Masonry. ASTM International: Washington, DC, USA, 2024.

- Stowarzyszenie Przemysłu Wapienniczego Tradycyjne Zaprawy Murarskie i Tynkarskie (Traditional Masonry Mortars and Plasters). Available online: https://wapno-info.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/112957-tradycyjne-zaprawy-murarskie-i-tynkarskie.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2025). (In Polish).

- Cupim, R.V.; Tostes Linhares Júnior, J.A.; Mesquita, L.C.; Marques, M.G.; Garcez de Azevedo, A.R.; Marvila, M.T. Rheological and Mechanical Properties of Mortars Made with Recycled Sugarcane Bagasse Ash. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 36, 3546–3555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liew, Y.X.; Saad, S.A.; Anand, N.; Tee, K.F.; Chin, S.C. Evaluating the Impact of Reducing POFA’s Particle Fineness on Its Pozzolanic Reactivity and Mortar Strength. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Eng. 2024, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahurudeen, A.; Kanraj, D.; Gokul Dev, V.; Santhanam, M. Performance Evaluation of Sugarcane Bagasse Ash Blended Cement in Concrete. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2015, 59, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, W.M.; Heniegal, A.M.; Amin, M.; Zeyad, A.M.; Agwa, I.S.; Hassan, H.H. Effect of Agricultural Wastes as Sugar Beet Ash, Sugarcane Leaf Ash, and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash on UHPC Properties. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, M.; Singh, K.R. Performance Characteristic of Sugarcane Fiber and Bagasse Ash as Cement Replacement in Sustainable Concrete. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2024, 9, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chusilp, N.; Jaturapitakkul, C.; Kiattikomol, K. Effects of LOI of Ground Bagasse Ash on the Compressive Strength and Sulfate Resistance of Mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2009, 23, 3523–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbasekar, M.; Hariprasath, P.; Senthilkumar, D. Study on potential utilization of sugarcane bagasse ash in steel fiber reinforced concrete. Int. J. Eng. Sci. Res. Technol. 2016, 5, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagadesh, P.; Ramachandra Murthy, A.; Murugesan, R. Effect of Processed Sugar Cane Bagasse Ash on Mechanical and Fracture Properties of Blended Mortar. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 262, 120846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, J.-R.; Liao, W.-C. Microstructure and Shrinkage Behavior of High-Performance Concrete Containing Supplementary Cementitious Materials. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 308, 125045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ortega, R.; Torres-Sanchez, D.; Lopez-Lara, T. Mechanical Properties of Hydraulic Concretes with Partial Replacement of Portland Cement by Pozzolans Obtained from Agro-Industrial Residues: A Review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fapohunda, C.; Akinbile, B.; Shittu, A. Structure and Properties of Mortar and Concrete with Rice Husk Ash as Partial Replacement of Ordinary Portland Cement—A Review. Int. J. Sustain. Built Environ. 2017, 6, 675–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Tang, J.; Geng, G. Exploring Microstructure Development of C-S-H Gel in Cement Blends with Starch-Based Polysaccharide Additives. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cizer, O.; Balen, K.V.; Gemert, D.V.; Elsen, J. Carbonation and Hydration of Mortars with Calcium Hydroxide and Calcium Silicate Binders. In Sustainable Construction Materials and Technologies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1-00-306102-1. [Google Scholar]

| Chemical Composition | OPC (%) | Lime (%) | RHA (%) | SCBA (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiO2 | 18.9 | 0.7 | 86.73 | 66.5 |

| Al2O | 3.8 | 0.04 | 4.82 | |

| Fe2O3 | 3.9 | 0.61 | 4.67 | |

| CaO | 63.3 | 90.2 | 0.39 | 3.83 |

| MgO | 1.2 | 1 | 0.08 | 2.87 |

| SO3 | 2.9 | 0.7 | 1.32 | |

| Na2O | 0.15 | 0.15 | 9.76 | 0.59 |

| K2O | 1.05 | 0.01 | 4.07 |

| Properties | OPC | RHA | SCBA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fineness, retained on 45 μm (%) | 13 | 19 | 14 |

| Density (kg/m3) | 3110 | 2240 | 2200 |

| Mixtures | Constituents (g) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CEM I 42.5R | Lime | Water | w/b Ratio (-) | Sand | Natural SCMs | Air-Entraining Admixture (APA) | ||

| RHA | SCBA | |||||||

| Cement mortar | ||||||||

| CM | 450 | - | 440 | 0.98 | 2308 | - | - | - |

| C-R5 | 427.5 | - | 2308 | 22.5 | - | |||

| C-R10 | 405 | - | 2308 | 45 | - | |||

| C-R15 | 382.5 | - | 2308 | 67.5 | - | |||

| C-S5 | 427.5 | - | 2308 | - | 22.5 | |||

| C-S10 | 405 | - | 2308 | - | 45 | |||

| C-S15 | 382.5 | - | 2308 | - | 67.5 | |||

| Cement–lime mortar | ||||||||

| CL | 350 | 253 | 410 | 0.68 | 1795 | - | - | - |

| CL-R5 | 332.5 | 253 | 1795 | 17.5 | - | |||

| CL-R10 | 315 | 253 | 1795 | 35 | - | |||

| CL-R15 | 297.5 | 253 | 1795 | 52.5 | - | |||

| CL-S5 | 332.5 | 253 | 1795 | - | 17.5 | |||

| CL-S10 | 315 | 253 | 1795 | - | 35 | |||

| CL-S15 | 297.5 | 253 | 1795 | - | 52.5 | |||

| Cement mortar with APA | ||||||||

| CA | 450 | - | 310 | 0.69 | 1795 | - | - | 2.25 |

| CA-R5 | 427.5 | - | 1795 | 17.5 | - | |||

| CA-R10 | 405 | - | 1795 | 35 | - | |||

| CA-R15 | 382.5 | - | 1795 | 52.5 | - | |||

| CA-S5 | 427.5 | - | 1795 | - | 17.5 | |||

| CA-S10 | 405 | - | 1795 | - | 35 | |||

| CA-S15 | 382.5 | - | 1795 | - | 52.5 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nayak, J.R.; Gołaszewska, M.; Bochen, J. Physical and Mechanical Performance of Mortar with Rice Husk Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Partial Cement Replacement. Materials 2025, 18, 4758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204758

Nayak JR, Gołaszewska M, Bochen J. Physical and Mechanical Performance of Mortar with Rice Husk Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Partial Cement Replacement. Materials. 2025; 18(20):4758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204758

Chicago/Turabian StyleNayak, Jyoti Rashmi, Małgorzata Gołaszewska, and Jerzy Bochen. 2025. "Physical and Mechanical Performance of Mortar with Rice Husk Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Partial Cement Replacement" Materials 18, no. 20: 4758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204758

APA StyleNayak, J. R., Gołaszewska, M., & Bochen, J. (2025). Physical and Mechanical Performance of Mortar with Rice Husk Ash and Sugarcane Bagasse Ash as Partial Cement Replacement. Materials, 18(20), 4758. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18204758