1. Introduction

As one of the most important plastic pipes, high-density polyethylene (HDPE) pipes have well-known advantages such as excellent safety, practicality, durability, and reasonable price [

1,

2,

3]. They have a wide range of applications and uses [

4,

5]. For example, HDPE is used for energy transportation and raw material transportation in the ocean. At the same time, HDPE pipelines are gradually replacing various metal pipelines in lifeline engineering [

6,

7,

8]. However, irrespective of their application in the ocean, HDPE B-FWJs are exposed to diverse and challenging working environments. Various geological disasters, external environmental interferences, temperature fluctuations due to seasonal changes, and numerous other factors can be encountered. In the event of any accidents, particularly in areas with a concentrated fishing industry or that are near the coast, the consequences can be severe. Due to the secondary processing of the pipe joint position, the performance of HDPE pipes may change, and the various properties at the pipe joint belong to the weak position of the pipe body during the aging process [

9,

10]. The B-FW method is extensively employed in on-site scenarios due to its fast and convenient application, offering high-quality and reliable pipeline joints [

11,

12]. There are two aging methods for pipeline joints: natural aging and accelerated aging [

13]. However, accelerated aging methods are commonly used to study the degree of polyethylene aging to shorten the experimental cycle and achieve the goal of rapid aging of polyethylene samples in a short period [

14]. The mechanical properties of HDPE undergo a decline, and its safe service time is subject to change in actual engineering due to the distinctive molecular structure of the material and the influence of various factors [

15]. Therefore, the focus of researchers has become the alterations in performance and reliable operational duration of HDPE pipelines during their operation [

16,

17].

Currently, the primary methodologies for connecting polyethylene (PE) pipelines are butt-fusion connection (BF) [

18] and electric-fusion connection (EF) [

19,

20]. Both BF and EF joints are created through docking machinery and procedures that involve butt-fusion welding [

21]. Consequently, the pipe joint section, being a secondary processing product, exhibits distinct performance characteristics and microstructures compared with the pipe body. In engineering practice, joints are often regarded as the Achilles’ heel of pipeline systems due to their susceptibility to failures [

22]. Therefore, the performance of joints is paramount to the overall safety and efficiency of the pipeline system. To this end, researchers have been actively exploring methods to evaluate and enhance the performance of PE joints. Wermelinger and his team designed a water axial tension (HAT) test to assess the performance of PE BF joints with various internal defects. This test provides valuable insights into the strength and durability of BF joints under different conditions [

23]. Similarly, Kim and his colleagues conducted notch tensile testing to compare the toughness of B-FWJ with the tube body. Their findings revealed that the toughness of welded joints was inferior to that of the tube body, highlighting the need for further research to improve the welding process and enhance joint performance [

24]. Ghanadi et al. conducted a study to investigate the effects of ultraviolet radiation on the degradation of HDPE pile sleeves in both natural and laboratory environments, with the aim of isolating the effects of UV radiation. Compared with samples exposed to accelerated UVB irradiation in the laboratory, those exposed to the marine environment exhibited an increase in oxygen-containing surface functional groups and more pronounced morphological changes [

25]. Liu et al. explored the characteristics of polyethylene changes under high-temperature aquatic conditions and found that depolymerization typically occurs subsequent to thermal cracking. During this process, the scission of PE molecules is random and primarily induced by thermal treatment, while reactions such as polymerization, cyclization, and radical recombination based on radical mechanisms are relatively less prevalent [

26]. Despite these advancements, there is still a paucity of research on the aging performance of BF joints in marine environments. Given the harsh conditions that marine pipelines endure, including exposure to high temperatures, pressure, and corrosive elements, it is imperative to conduct comparative experimental studies on the effects of hydrothermal aging at different temperatures on the performance of BF joints. Such studies will not only contribute to a better understanding of the aging mechanisms of PE materials in marine environments but also aid in the development of more durable and reliable pipeline systems.

HDPE B-FWJs were taken in this article as the subject of study, and accelerated aging tests were conducted on HDPE B-FWJs under hydrothermal aging conditions at different temperatures. Mechanical testing was conducted on the B-FWJs, the test results were analyzed, and the aging laws of the B-FWJs under different temperature hydrothermal aging conditions were summarized. The analysis focused on the cross-linking mechanism of molecular chains in the region influenced by the heat of HDPE B-FWJs following hydrothermal aging at various temperatures. The findings of this study contribute to addressing the knowledge gap in the aging theoretical system of HDPE pipes, specifically about the B-FWJ under hydrothermal aging conditions. The findings of this paper will contribute to a deeper understanding of the B-FWJ in marine environments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. SEM

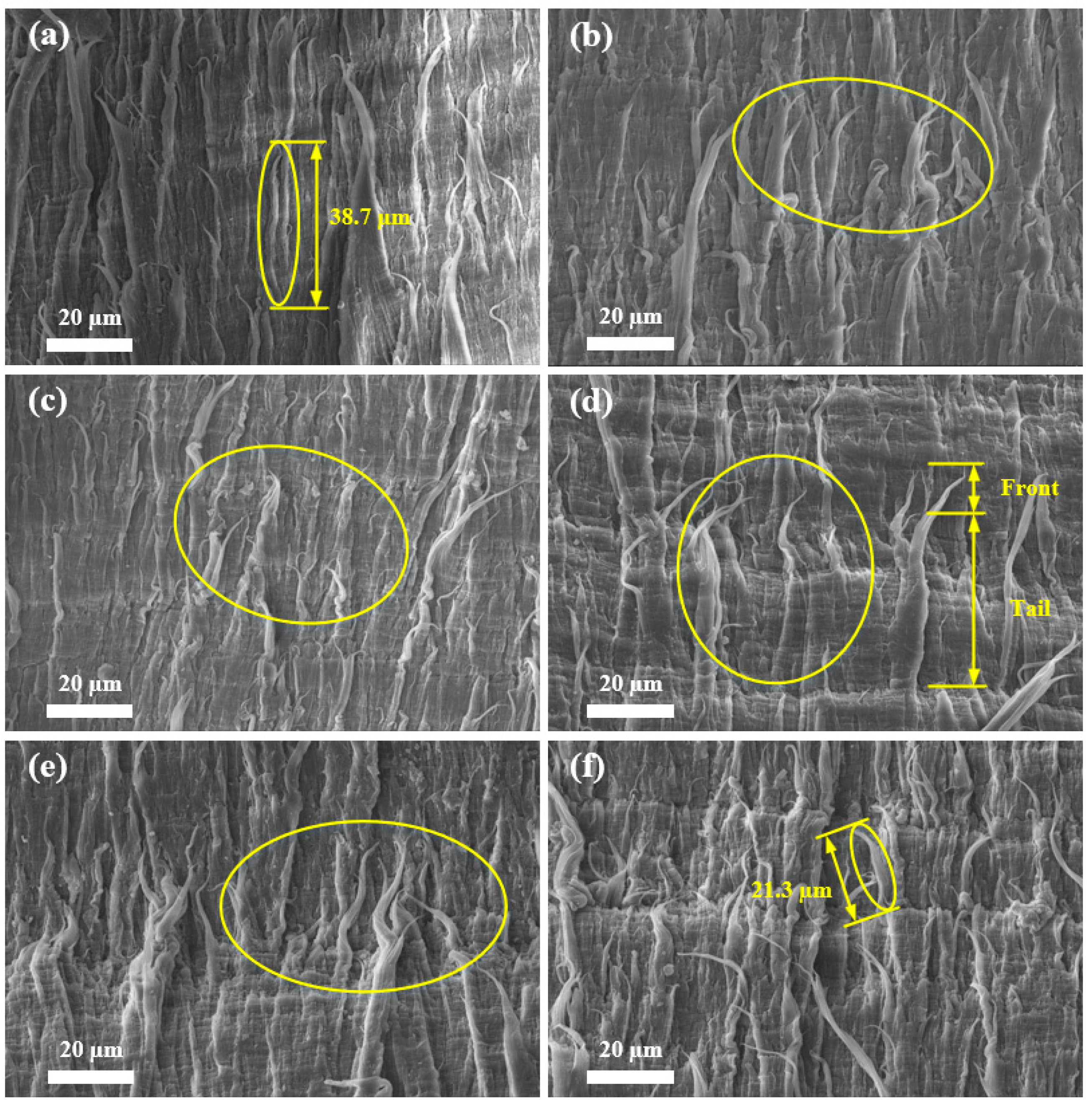

Figure 5 shows the micro-surface morphology (M-SM) of the fracture surface resulting from the B-FWJ at five distinct time points without aging and hydrothermal aging at 40 °C. During the 600 h aging process, the fiber length of the B-FWJ decreased from 38.7 μm to 21.3 μm. At 0–480 h, the diameter and length of the fibers in the B-FWJ did not change significantly, but the number of fibers in the B-FWJ increased. Following 600 h of aging, the length of the fibers in the B-FWJ notably decreased, while the number of fibers reached its maximum.

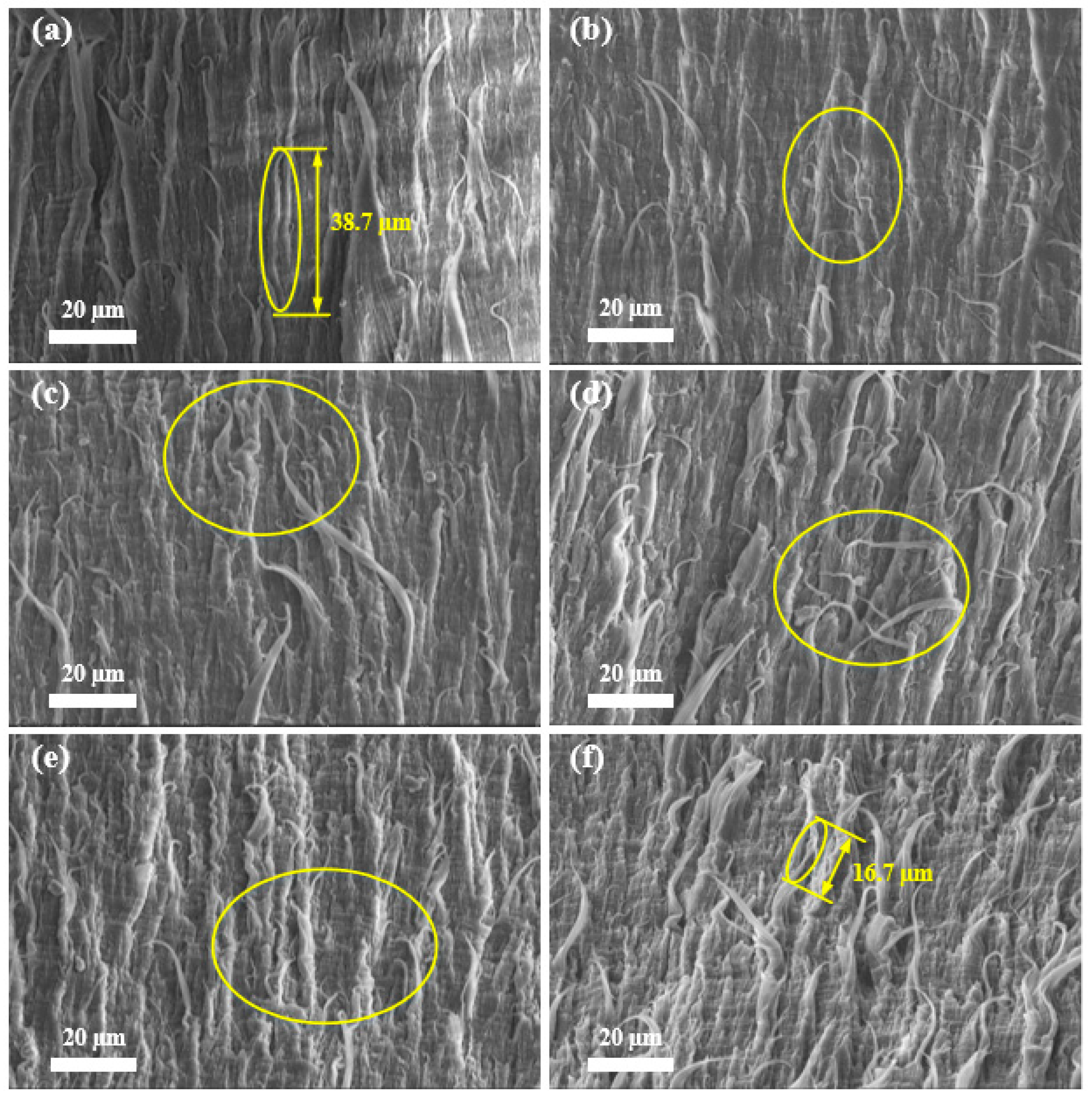

Figure 6 reveals the M-SM of the fracture surface resulting from the B-FWJ at five distinct time points without aging and hydrothermal aging at 60 °C. The B-FWJ, which had undergone aging for less than 600 h, exhibited a significant reduction of 54.8% in fiber length. The aging time of 480 h can be considered the threshold for fiber changes. The fiber length of the B-FWJ aged 360 h was 3.8 μm shorter than that of the B-FWJ aged 480 h. The fiber length of a 600 h-aged B-FWJ was 7.4 μm longer than that of a 480 h-aged joint. Before the boundary, the diameter and length of the fibers in the B-FWJ did not change significantly, but the number of fibers in the B-FWJ showed an increasing trend. After the boundary, the length of the B-FWJ fibers significantly decreased, and the number of fibers was higher than that of the B-FWJ fibers before aging for 600 h.

Figure 7 displays the M-SM of the fracture surface resulting from the B-FWJ at five distinct time points, including before the aging and under the hydrothermal aging at 80 °C. After a duration of 600 h, the fiber length of the B-FWJ decreased significantly, from 38.7 to 17.5 μm—a total reduction of 56.8%. The hydrothermal aging in water at this temperature resulted in a shorter fiber length on the surface of the rupture of the B-FWJ compared with at 40 °C and 60 °C, respectively. The changes in the fractured surface fibers of B-FWJ aged under hydrothermal aging at different temperatures exhibited similarities. After 0–480 h, there was no significant change in the diameters and lengths of the fibers in the B-FWJ, but the number of fibers showed an increasing trend. After undergoing aging for 600 h, the length of the fibers in the B-FWJ underwent a notable decrease. And the number of fibers was higher than that of the B-FWJ fibers before aging for 600 h.

As the aging time and the aging temperature increased, the diameter and length of B-FWJ fibers did not change significantly in the first stage (0–120 h). However, in the second stage (120–480 h), the diameter and length of the fibers in the B-FWJ diminished. Following a 600 h aging process, the fractured surface of the B-FWJ exhibited the greatest roughness at 80 °C, characterized by numerous fiber breaks and a reduction in fiber length. The fractured surface of the B-FWJ was the roughest at 40 °C. Therefore, it can be concluded that the increase in temperature under hydrothermal aging conditions will accelerate the aging rate of the B-FWJ. When the specimen was subjected to axial tension, as the stretching continued, the molecular chains of the B-FWJ continued to be subjected to force, and the molecular chain morphology gradually tended towards a linear shape. Furthermore, as the distance between molecular chains gradually increased, the interaction force between molecular chains gradually decreased, and a reduction in the toughness of the B-FWJ was observed. The macroscopic manifestation was that the fractured surface produced fiber filaments and fiber filament fractures, and the toughness of the B-FWJ decreased.

As the duration of hydrothermal aging increased at a constant temperature, two phenomena were observed. Firstly, the antioxidant content of the B-FWJ gradually decreased, leading to aging and degradation of the material; secondly, the interaction between the material’s molecular chains and groups with water molecules led to changes in the structural characteristics of their interfaces [

35]. Consequently, this reaction diminished the contribution of interaction forces between material molecular chains and molecular groups to the material’s strength, affirming the strength changes observed in

Section 3.4 for the B-FWJ.

3.2. Oxidation Induction Time

DSC was utilized to measure the OIT of the B-FWJ following water bath aging at various temperatures. Previous research conducted by scholars has established the attenuation index equation for the OIT of polyethylene pipelines, represented by Equation (1), given below. The B-FWJ, a constituent of a polyethylene pipeline, followed the same attenuation equation for its OIT, as described below.

In Equation (1), t is the aging time of the B-FWJ, T(t) is the OIT of the B-FWJ after the aging time “t” in h hours, T0 is the OIT of the unprocessed B-FWJ, s is the antioxidant consumption rate, and A is a constant.

Figure 8 depicts the fitting curve and corresponding equation, which characterize the decline in the OIT of the B-FWJ subjected to wet heat aging at differing temperatures. The DSC technique was employed to measure the OIT of the B-FWJ following hydrothermal aging at various temperatures.

Figure 8 demonstrates that, as the aging duration increased, the antioxidants within the B-FWJ, which had undergone hydrothermal aging at various temperatures, underwent gradual consumption, resulting in a decreasing trend in their OIT values. The order of reduction in the oxidation induction period of B-FWJ subjected to hydrothermal aging at the same temperature, from highest to lowest, was as follows: 80 °C (25.00%), 60 °C (23.39%), and 40 °C (22.32%). The results are similar to the mechanical performance of the B-FWJ in

Section 3.4. At the same aging time, as the temperature increased, the activity of antioxidants in the B-FWJ increased, leading to a higher rate of antioxidant consumption and a gradual decrease in the oxidation induction period of the B-FWJ. When the aging time was the same, the higher the temperature of hydrothermal aging, the lower the oxidation induction period value of the B-FWJ. At an identical aging time, an increase in the temperature of hydrothermal aging resulted in a decrease in the oxidation induction period value of the B-FWJ.

3.3. ATR FT-IR Spectroscopy

To obtain the changes in the number of major functional groups during the aging procedure of HDPE B-FWJ, the commonly used method is to reflect the trend of the functional group changes through ATR testing. The asymmetric and symmetric tensile vibrations of methylene (-CH

2) occur at 2913 cm

−1 and 2846 cm

−1, respectively. Additionally, the deformation of hydrocarbon bonds and the rocking vibrations of carbon–carbon single bonds occur at 1461 cm

−1 and 717 cm

−1, respectively. The infrared spectra of the unaged and aged B-FWJ samples were similar and had little change, so it can be considered that the carbon skeleton structure of the B-FWJ did not show significant changes in the hydrothermal aging accelerated aging test. After the aging of the B-FWJ of the pipeline, the molecular chain breakage in the microstructure increased [

36]. By examining the infrared spectra of the B-FWJ sample in

Figure 9, during the aging process at different temperatures, it became evident that hydrothermal aging did not cause significant damage to the basic material skeleton.

As shown in

Figure 10, the absorption peaks of the B-FWJ after the hydrothermal aging were in the ranges 3662–3127 cm

−1, 1710–1527 cm

−1, and 1170–954 cm

−1. The functional groups within the 1710–1527 cm

−1 band mainly consisted of carbonyl groups. The stretching vibrations of C-O bonds in carbonyl C=O, undamaged alcohol structures, and -CH

2OH continuously increased with aging time within the 1710–1527 cm

−1 and 1170–954 cm

−1 bands [

37]. The functional groups in the 1170–954 cm

−1 band mainly consisted of ether groups, and a characteristic absorption peak of carbonyl groups appeared in this band [

38]. The products of B-FWJ hydrothermal aging mainly included esters, ketones, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids, identified as polyethylene degradation products [

39]. Furthermore, the presence of OH bonds could be attributed to a reaction between the water molecules and the B-FWJ molecular chain, and partly came from some molecular chains of B-FWJ and water molecules themselves [

40]. Therefore, it is believed that, after aging the B-FWJ in this hydrothermal aging test, there were aging products such as alcohols, ethers, phenols, and hydrocarbons in the material.

Figure 11 presents a magnified image of the B-FWJ within the 3662–3127 cm

−1 wavelength range, following exposure to hydrothermal aging at various temperatures. At a constant hydrothermal aging temperature and within the same absorbance band, the absorbance peak of the B-FWJ increased as the aging duration extended. The characteristics of the sample in the 3662–3127 cm

−1 band aligned with the vibrations of -OH and -C≡C-, providing further evidence for the formation of new substances or groups during the process of aging the B-FWJ.

3.4. Mechanical Properties

3.4.1. Analysis of Impact Performance

As depicted in

Figure 12, there was a negative correlation between the impact energy of the B-FWJ and the aging time after undergoing hydrothermal aging at various temperatures.

During the entire aging process, specifically in the aging period of 480–600 h at 80 °C in a water bath, the specimen’s B-FWJ impact energy decreased the most, reaching 0.09 J (a total decrease of 0.22 J), accounting for 40.91% of the total decrease. Moreover, the slope of the impact energy of the B-FWJ specimen was the largest.

Figure 12 shows the impact energy variation curve of the thermal butt-fusion joint following hydrothermal aging at varying temperatures. The impact energy change of the B-FWJ specimen during the aging process, particularly in the hydrothermal aging at 60 °C, was similar to the impact energy change of the B-FWJ specimen at 80 °C during hydrothermal aging. When the aging time reached 600 h, the decrease in impact energy (0.13 J reduction) of the B-FWJ after hydrothermal aging at 40 °C was comparatively smaller than the reductions observed in the B-FWJ after hydrothermal aging at 80 °C and 60 °C (0.22 J reduction for hydrothermal aging at 80 °C and 0.21 J reduction for hydrothermal aging at 60 °C).

As illustrated in

Figure 13, the B-FWJ’s impact strength diminished as it underwent hydrothermal aging at varying temperatures. As the aging duration increased, the impact strength diminished. Notably, after the aging process, the B-FWJ subjected to hydrothermal aging at 80 °C exhibited a significant reduction in impact strength, decreasing by 21.50% compared with the other two temperature conditions. Conversely, the B-FWJ showed the least decrease in impact strength when aged at 60 °C, with a mere reduction of 12.76%. When the aging time was the same, an increase in the test temperature made long-chain breakage in the molecules within the hydrothermal environment easier. This resulted in an increased number of short chains, a reduced difficulty in intermolecular cross-linking, increased brittleness of the material, and a subsequent decrease in both the impact energy and impact strength of the sample. Therefore, the impact energy and strength of B-FWJ were highly affected by temperature under the hydrothermal aging conditions.

3.4.2. Tensile Properties

Figure 14 shows that the B-FWJ’s tensile strength diminished as it underwent hydrothermal aging at varying temperatures There was a negative correlation between the tensile strength of the B-FWJ, aging time, and temperature. After 600 h of aging, the tensile strength of the B-FWJ, regardless of the aging temperature, demonstrated comparable values. Following the completion of the aging process, the tensile strength of the B-FWJ exhibited a reduction of 4.33 MPa after hydrothermal aging at 80 °C and a decrease of 2.73 MPa after hydrothermal aging at 40 °C.

As the aging time increased, the molecular bonds in the molecular chain of the B-FWJ became more susceptible to fracture or breakage, reducing the interaction force between the molecular chains. Hence, as the aging duration extended, the tensile strength of the B-FWJ diminished. When the aging time remained constant, increasing the temperature resulted in higher energy absorption by certain molecular chains in the B-FWJ (without reaching the energy required for disconnecting the bonds), reducing the molecular chains’ ability to resist tensile damage. Some molecular chains within the B-FWJ may also experience breakage. Under the combined action of molecular bond energy absorption and molecular chain breakage, the flexibility of the material was reduced. Due to the combined effects of molecular bond energy absorption and molecular chain rupture, the material’s flexibility underwent a reduction.

3.4.3. Hardness

Figure 15 shows the B-FWJ’s surface hardness as it underwent hydrothermal aging at varying temperatures. After conducting hydrothermal aging tests at three distinct temperatures, the surface hardness of the B-FWJ samples increased. Notably, after 600 h of aging, the sample aged at 80 °C exhibited the greatest increase in surface hardness, amounting to 24.90%. The increase in surface hardness of the B-FWJB-FWJ was the smallest at 40 °C during hydrothermal aging, reaching 19.21%. As time went on, the hardness of the B-FWJ increased in a stepwise manner after the hydrothermal aging at different temperatures. The degree of stepwise growth in surface hardness during the pre-aging stage (0–360 h) was more significant compared with the post-aging stage (360–600 h), indicating a gradual stabilization of material aging over time.

Since the PE pipe B-FWJ is a product formed through secondary processing, the crystallization zone of the B-FWJ is mainly divided into two types: the semi-crystalline zone and the crystalline zone. The molecular chains within the semi-crystalline region remain intact, having not yet experienced degradation or oxidation reactions with oxides.

The molecular chain has a low degree of crystallinity, and its structure maintains a high porosity, providing a loose flow gap for water and oxygen molecules to flow between the polymeric chains in the semi-crystalline area [

41]. At the same aging time, as the hydrothermal aging temperature increases, the activity of oxygen and water molecules increases, and the number of them diffusing to the semi-crystalline region increases. The molecular chains undergo oxidation during the first stage and generate short chains. In the second stage, there is a shift in the arrangement of the molecular chains within the semi-crystalline region, resulting in a decrease in molecular chain spacing and a more orderly arrangement. Microscopic manifestation is that the crystallization zone of the B-FWJ expands, and its crystallinity increases. On a macroscopic level, the toughness of the B-FWJ decreases, the plasticity increases, and the hardness increases [

42]. Gulmine et al. [

43] conducted accelerated aging tests on polyethylene cables and found that the aging process increases the hardness and molecular chains of the polyethylene material.

3.4.4. Vicat Softening Temperature

Figure 16 shows the B-FWJ’s VST as it underwent hydrothermal aging at varying temperatures. During the 0–480 h period, the VST of the B-FWJ showed an increasing trend over time. At an aging time of 600 h, the VST of the B-FWJ peaked after hydrothermal aging at three different temperatures. Still, the Vicat temperature change during the aging was less than 1.8%, indicating that hydrothermal aging has an insignificant effect on the VST of the B-FWJ.

As the hydrothermal aging temperature rose at the same aging time, the B-FWJ experienced a higher degree of molecular chain cross-linking and entanglement, resulting in alterations in the relative positions of molecules and molecular chains, ultimately leading to a decrease in the mobility of the molecular chains.

3.5. Discussion on Ageing Mechanisms

As the B-FWJv is the product of secondary processing, part of the molecular chain of the B-FWJ in the heat-affected zone is destroyed during the heating process. It results in a molecular chain break and release of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups that affect the mechanical properties of materials. During the melting process, the molecular chains of the B-FWJ undergo cross-linking and fracture, producing free hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. A portion of the long chains of molecules forms a grid-like structure due to cross-linking. Some of the long chains of molecules undergo breakage, shortening their length and producing molecular chain breaks and free groups, such as hydroxyl and carbonyl groups.

Figure 17 illustrates the process of water molecule infiltration on the surface of the B-FWJ and the mechanism of aging resulting from the interaction between the B-FWJ and water molecules. With an increase in aging time, there was a corresponding increase in the number of water molecules that permeated into the B-FWJ. The red framed area in

Figure 17a depicts the B-FWJ, and the schematic diagram on its right side illustrates the penetration of water molecules into the B-FWJ. As the aging temperature rose and the degree of water molecule diffusion into the B-FWJ intensified, leading to the gradual consumption of antioxidants. The molecular chains of the oxidized B-FWJ underwent cross-linking and fracture. Due to the combined effect of temperature and water molecules, the aging reaction of the B-FWJ was severe in the early stage of hydrothermal aging. The reaction between the water molecules, oxygen, and the molecular chains of the B-FWJ led to the formation of alcohols, phenols, aldehydes, and ketones at the ends of the primary and secondary chains, indicating the initiation of aging in the B-FWJ, as shown in Phase I of

Figure 17b. The macroscopic manifestation was the reduction in the material’s tensile strength and impact strength. Adjacent molecular chains underwent cross-linking reactions, producing -COOR (esters, carboxylic acids), increasing their molecular weight and reducing their flowability, as shown in Phase II of

Figure 17b. This structural change made it more difficult for the material to undergo deformation when subjected to external forces, resulting in higher hardness and VST. As the reaction between the molecular chains of the B-FWJ, water molecules, and oxygen progressed, the degree of cross-linking and fracture in the long chains of the B-FWJ molecules increased, exacerbating the aging process. Aging exerted a notable influence on the mechanical properties and hardness of B-FWJ. On the one hand, aging caused a decline in the material’s tensile strength and impact strength. On the other hand, due to cross-linking reactions and structural alterations in the molecular chains, the material’s hardness and VST increased. Consequently, when assessing the impact of aging on B-FWJ, it is imperative to take into account its dual effects on both mechanical properties and either hardness or VST.

The schematic diagram of the crystallization zone around the B-FWJ weld seam is shown in

Figure 18. In

Figure 18a, the area within the yellow framed box is selected to create a schematic diagram of the B-FWJ, which is shown in

Figure 18b. In this schematic, the red line in

Figure 18a and the dashed black line in

Figure 18b represent the centerline of the B-FWJ.

Figure 18c illustrates the division of the centerline of the B-FWJ into six layers within the red dashed box in (b), based on the different crystal structures along the weld seam towards the unmelted region. The centerline area of the B-FWJ weld seam is composed of linear spherical crystals. The area of the centerline of the B-FWJ weld seam was composed of linear spherical crystals. Spherical coarse-grained crystals were formed in the parts with low heat dissipation rates. Due to the increase in the heat dissipation rate from the inside out, the crystal morphology gradually changed into a spherical fine-grained crystalline layer from the part with a low heat dissipation rate to the part with a high heat dissipation rate. The melt region was composed of directional linear crystallization, and the interaction between the two parts of the tube during the melting welding process and the cooling of the joint produce directional linear crystallization. A portion of stretched spherical crystals was generated in the secondary and third layers, with a morphology similar to directional linear crystallization in the melt region. The stretched spherical crystal structure in the fifth layer was connected to the spherical coarse-grained crystal in the outermost unmelted region.

4. Conclusions

The accelerated aging tests performed on PE100 pipeline B-FWJ involved three hydrothermal aging cycles with a duration of 600 h. The results demonstrated that the impact resistance, tensile strength, and chemical properties of PE100 pipeline B-FWJ decreased with increasing aging time and temperature. Conversely, the VST and Shore hardness exhibited slight increases. These changes can be attributed to the enhanced reaction between the molecular chains of the B-FWJ and water molecules, accompanied by a broader range of cross-linking and molecular chain fracture. Notably, as the aging temperature rose, the alterations in the number and morphology of fiber filaments on the fractured surface of the B-FWJ could be divided into two stages. In the initial stage, no significant changes occurred in the number and morphology of fiber filaments. However, in the subsequent stage, the number of fiber strands sharply increased, while their length and width decreased. Additionally, the roughness of the fractured surface of the B-FWJ significantly increased due to these changes.

During the initial phase of hydrothermal aging, the B-FWJ underwent a pronounced aging reaction due to the combined influence of temperature and water molecules. This reaction involved the interaction between water molecules, oxygen, and the molecular chains of the welded joint, resulting in the formation of alcohols, phenols, aldehydes, and ketones at the terminals of both primary and secondary chains. This marked the onset of aging in the B-FWJ. Adjacent molecular chains underwent cross-linking reactions, This process increased the molecular weight of the molecular chains and decreased its flowability. Aging exerted a notable influence on the mechanical properties and hardness of B-FWJ. On the one hand, aging caused a decline in the material’s tensile strength and impact strength. On the other hand, due to cross-linking reactions and structural alterations in the molecular chains, the material’s hardness and VST increased. Consequently, when assessing the impact of aging on B-FWJ, it is imperative to take into account its dual effects on both mechanical properties and either hardness or VST.