Experimental and Numerical Study of the Mixed Lubrication Considering Boundary Film Strength

Abstract

1. Introduction

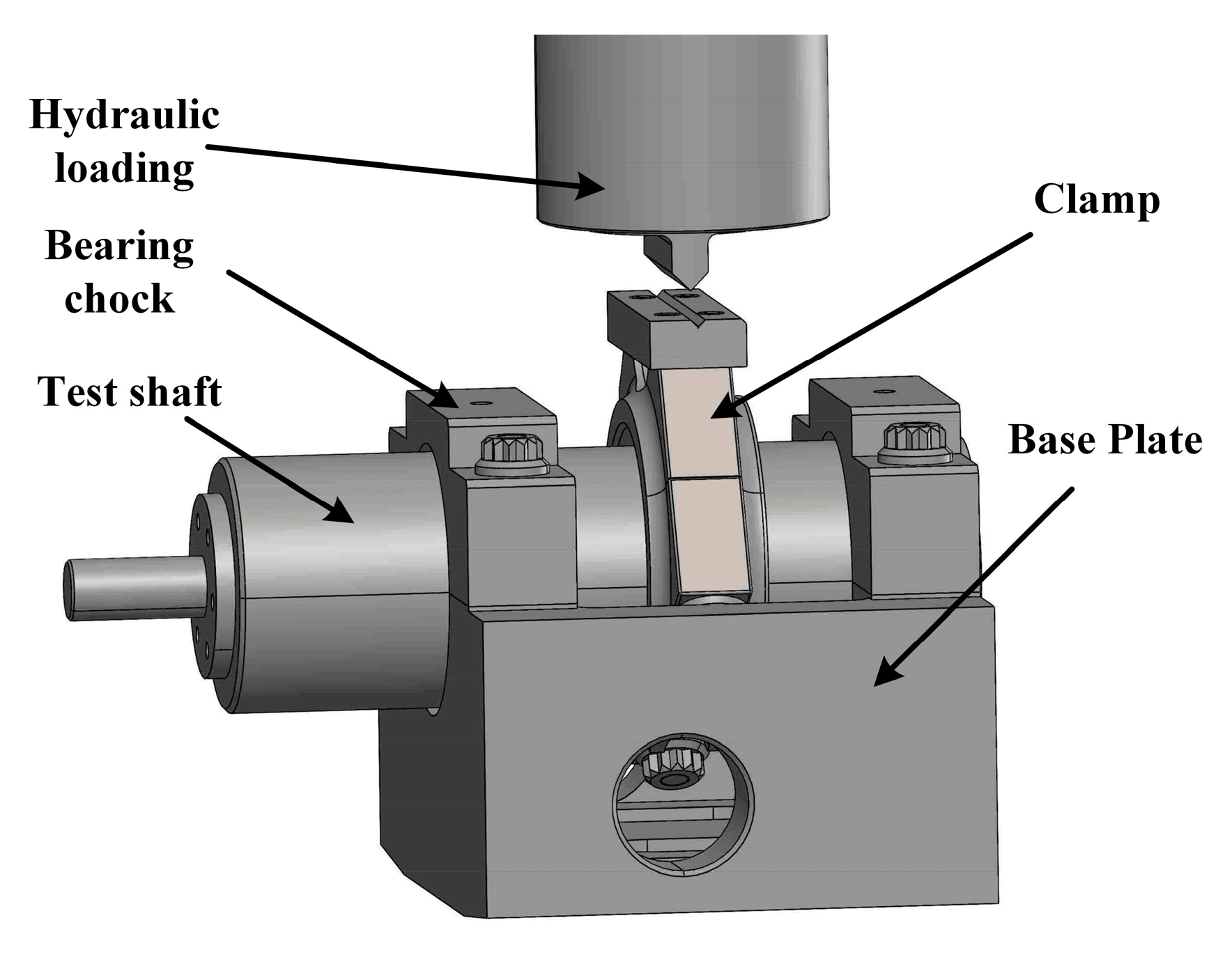

2. Test Method

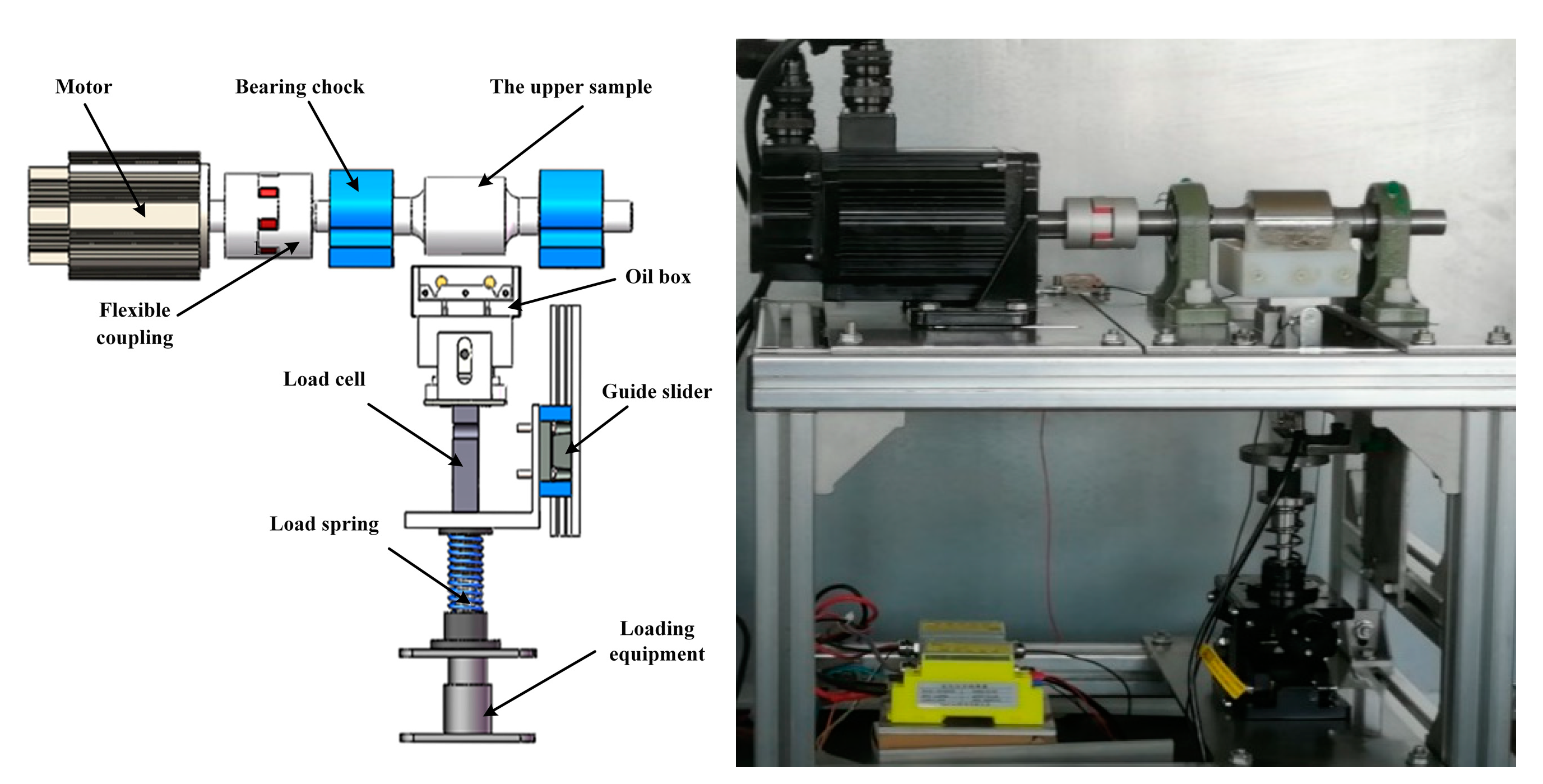

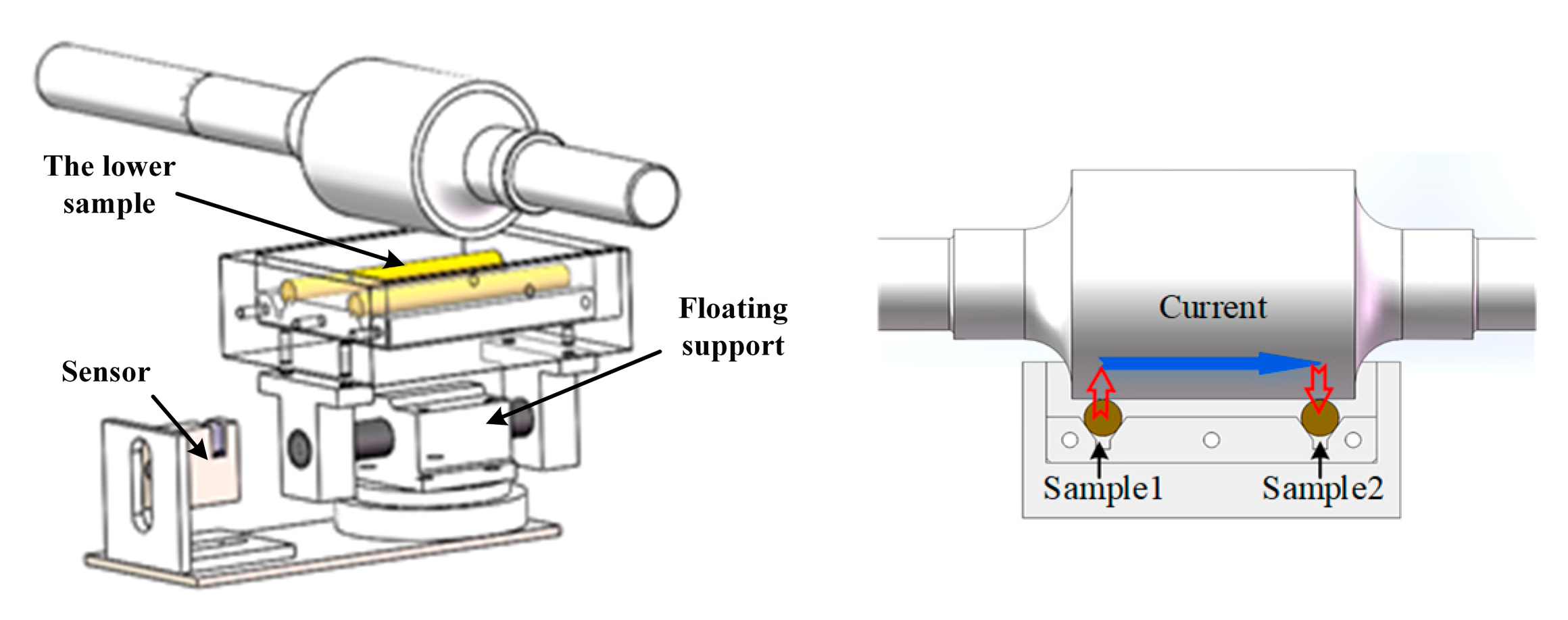

2.1. Testing Machine

2.2. Test Preparation

2.3. Test Specifications

3. Boundary Film Strength Model

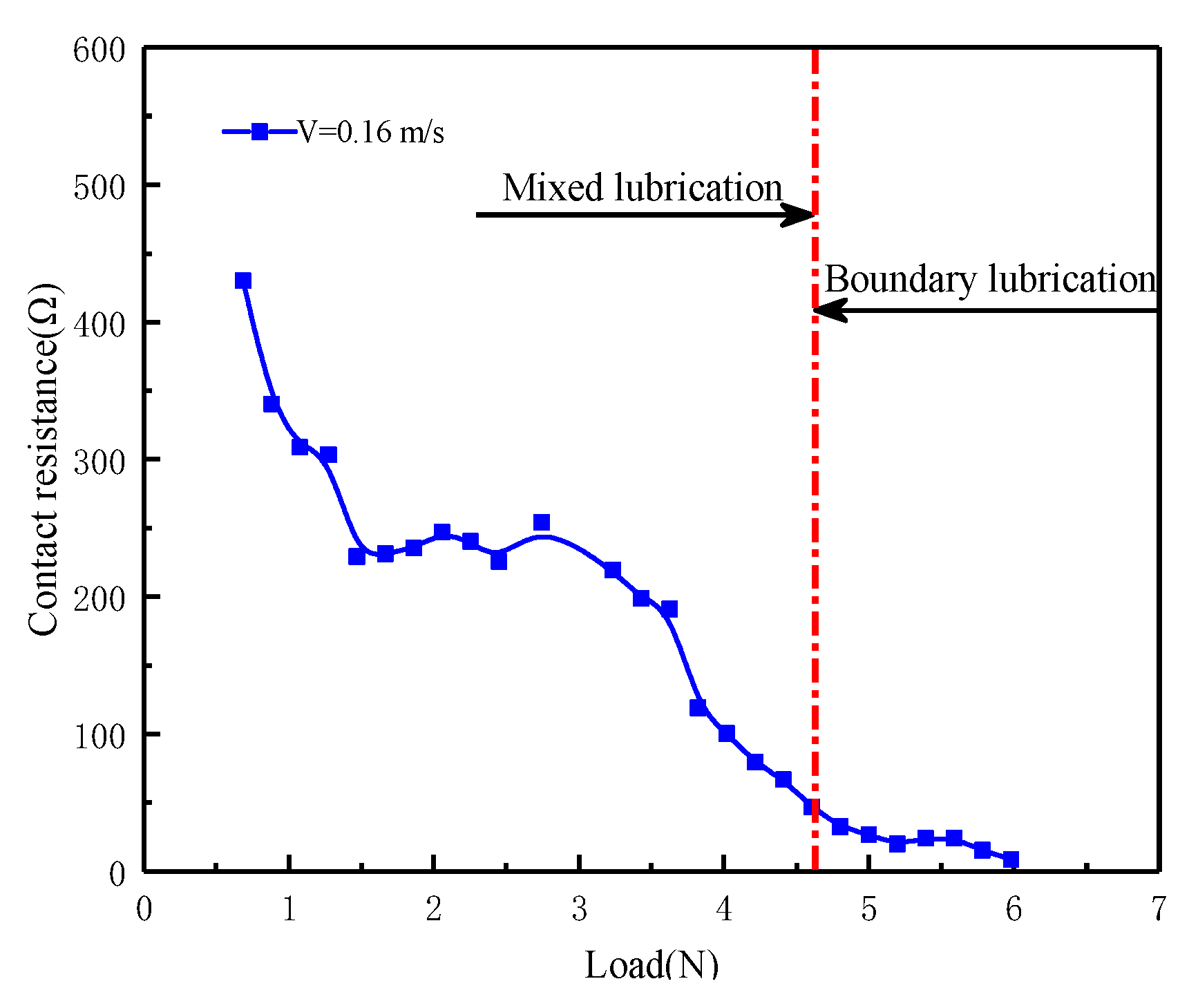

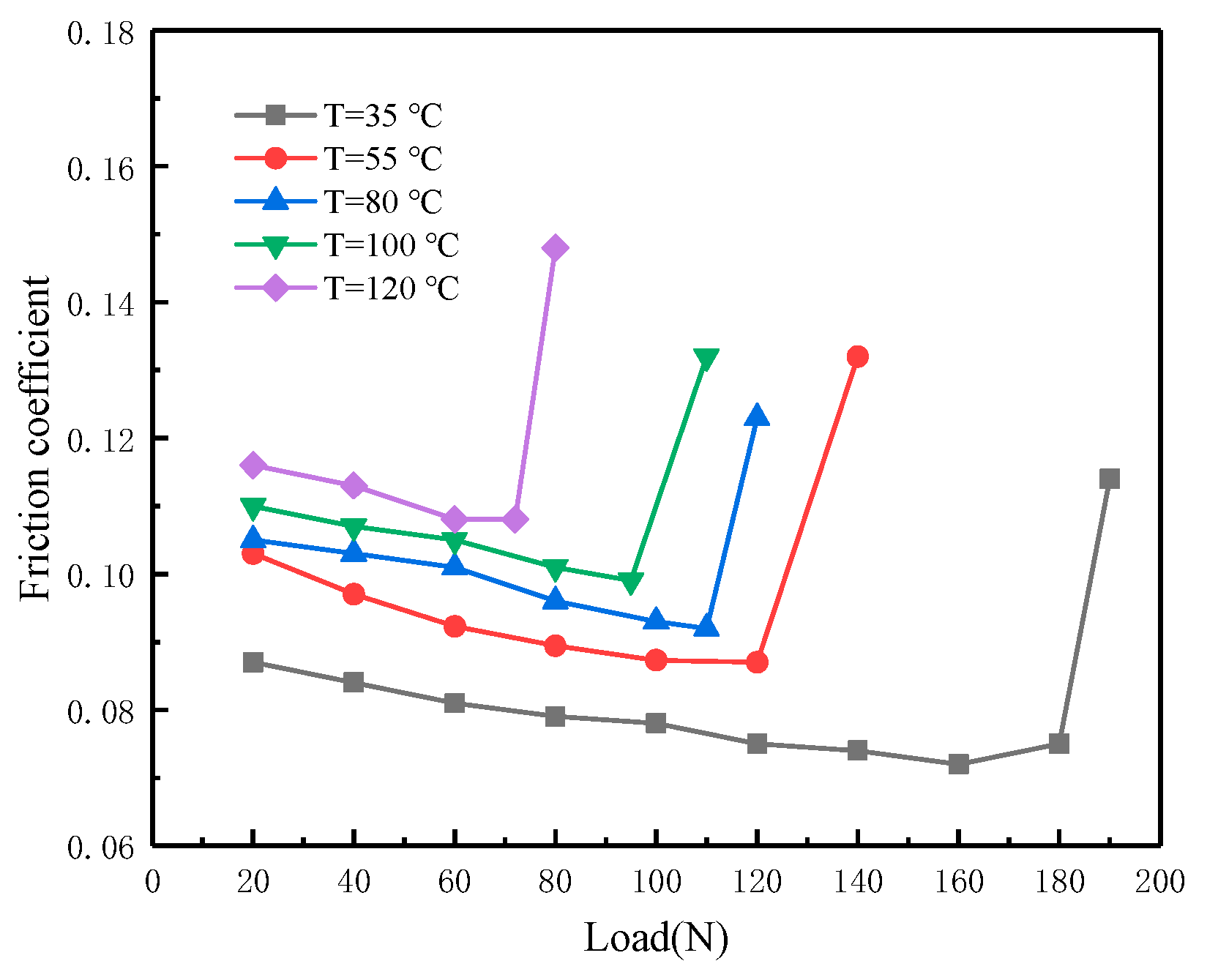

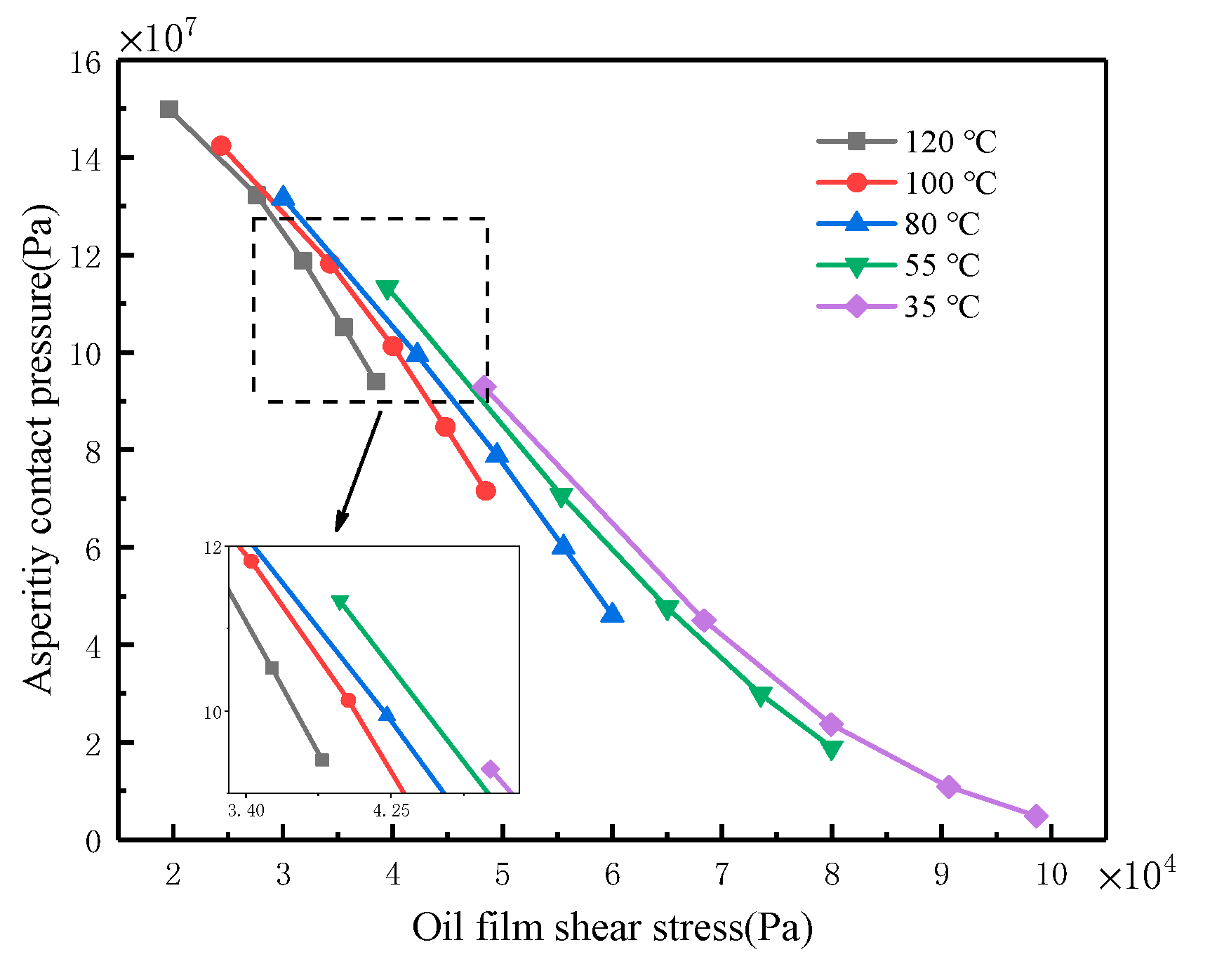

3.1. The Failure Features of the Boundary Lubrication

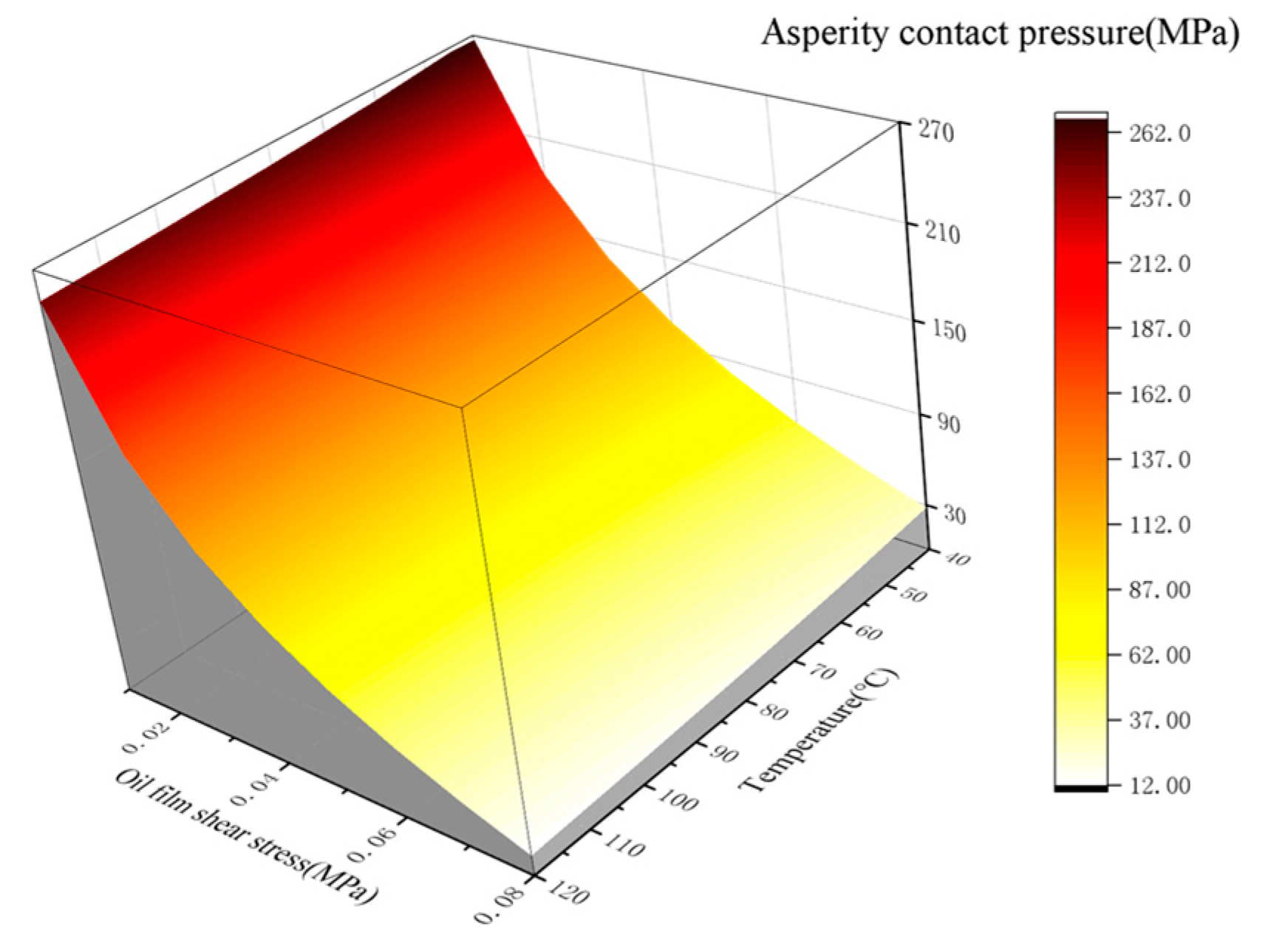

3.2. Model Fitting

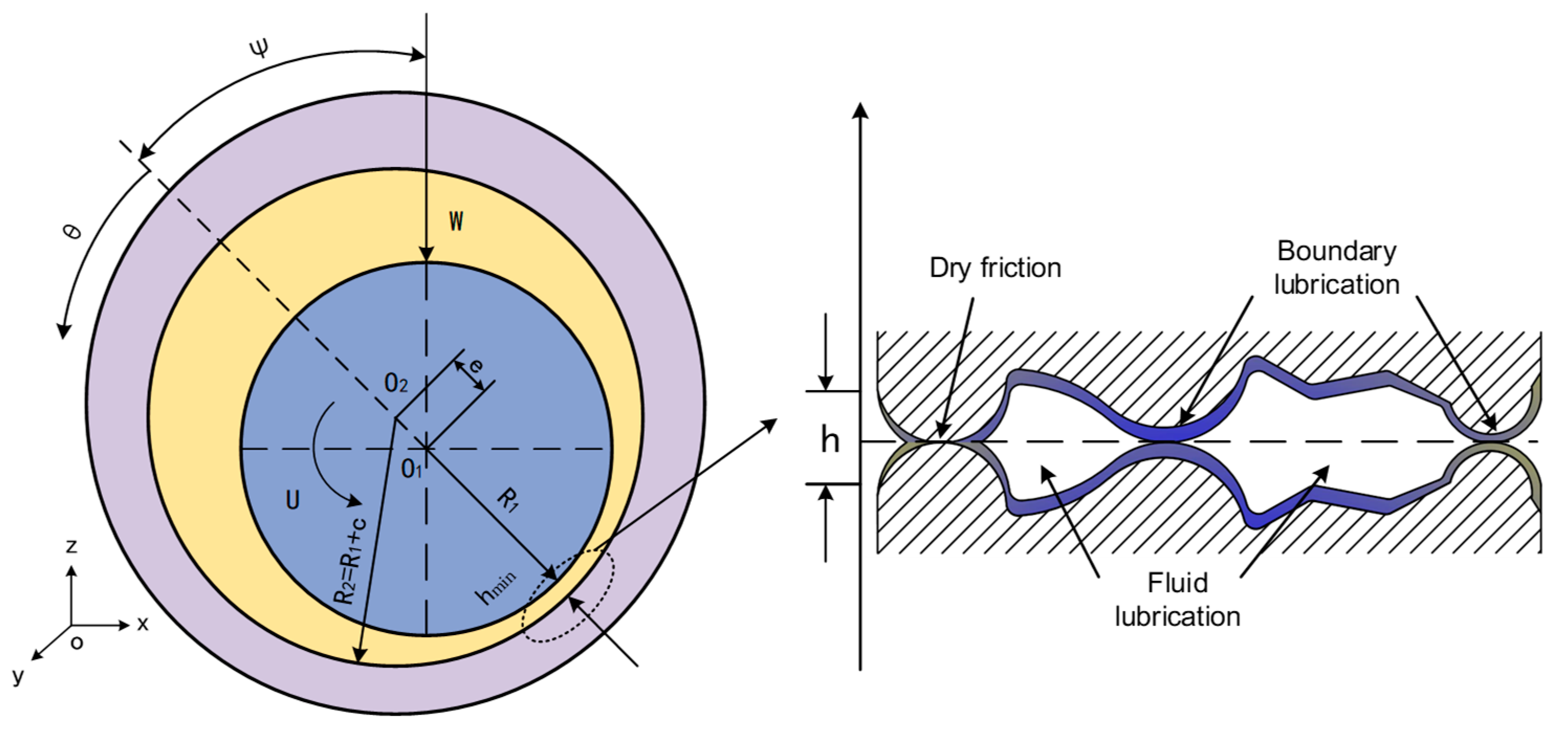

4. Establishment of Mixed Lubrication Model

4.1. Basic Model

4.2. Asperity Contact

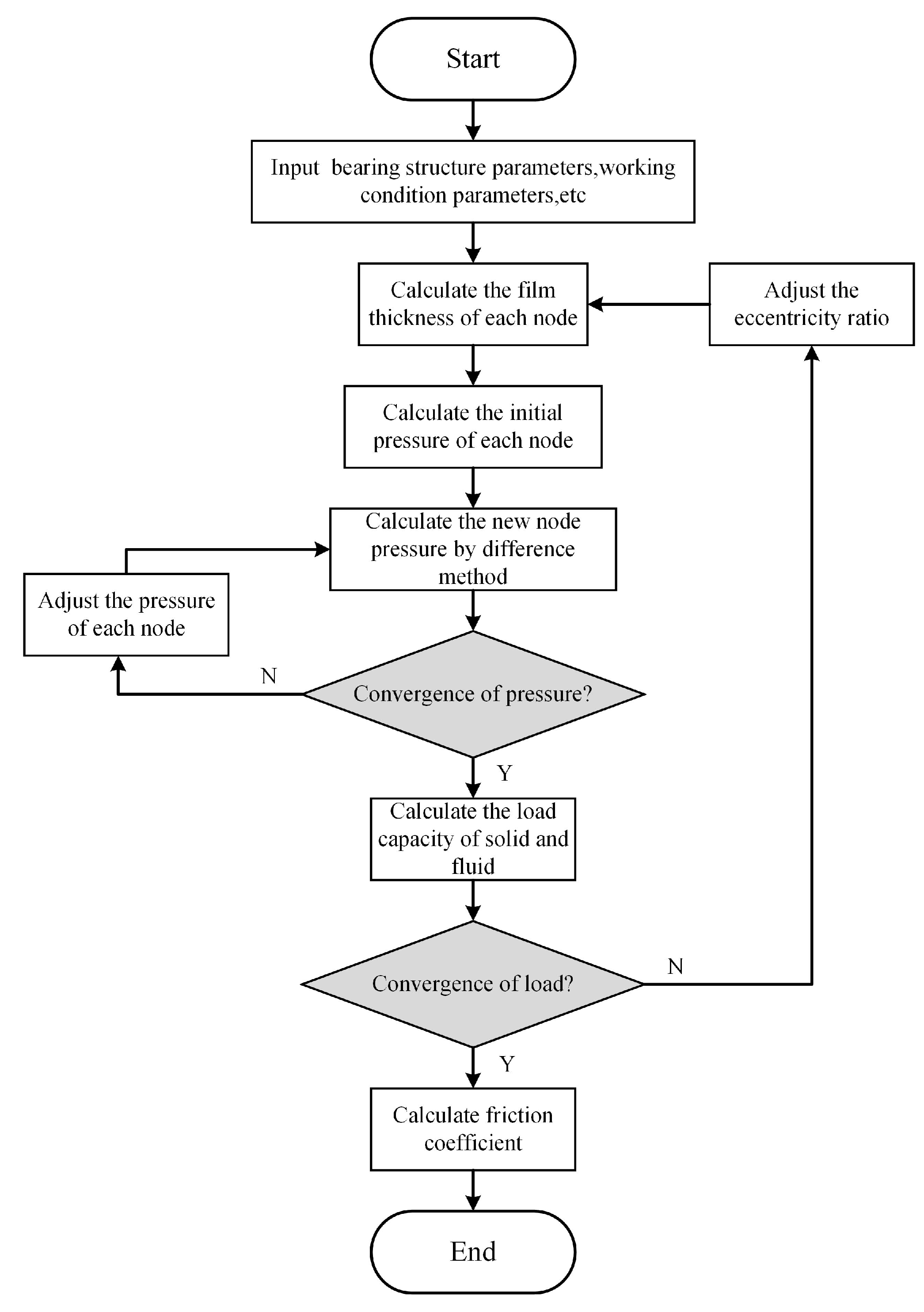

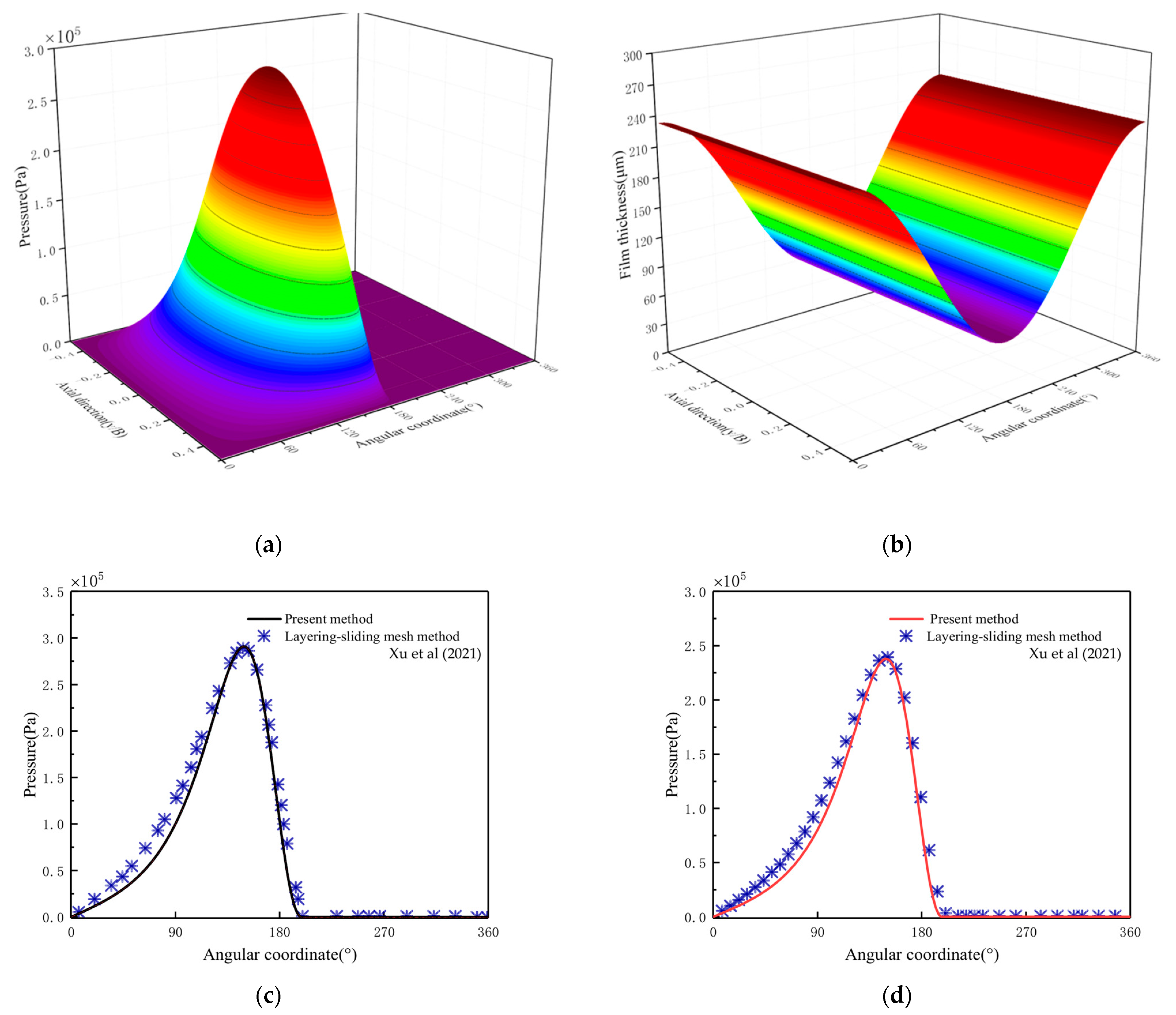

4.3. Solution Process and Preliminary Verification

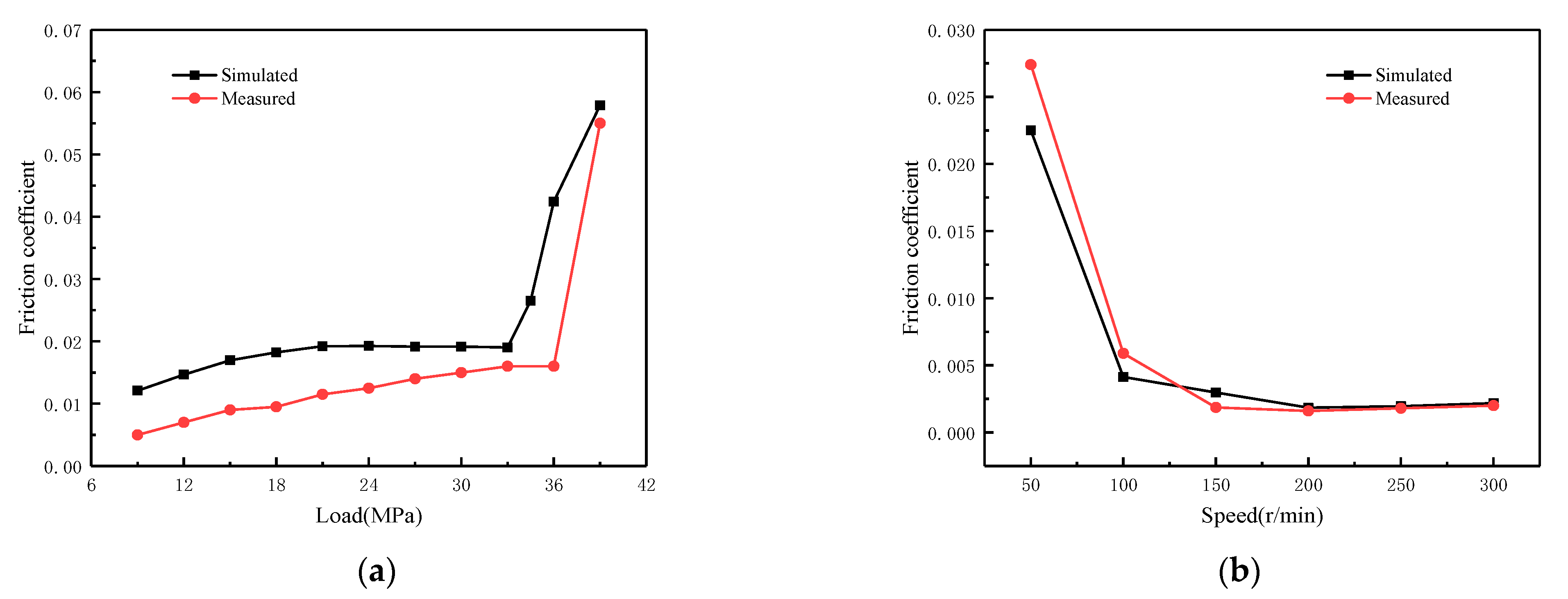

4.4. Experimental Verification

5. Application of Mixed Lubrication Model

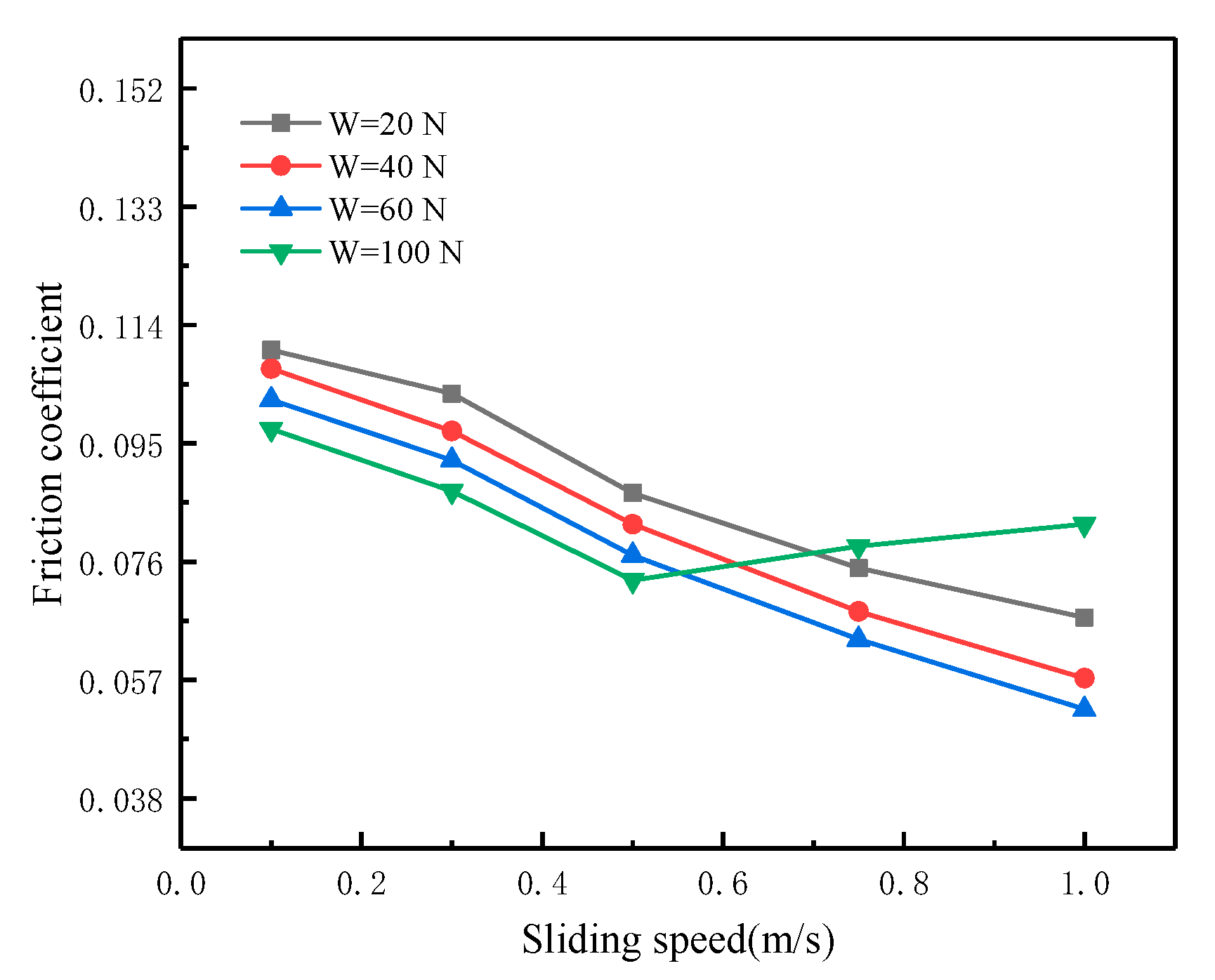

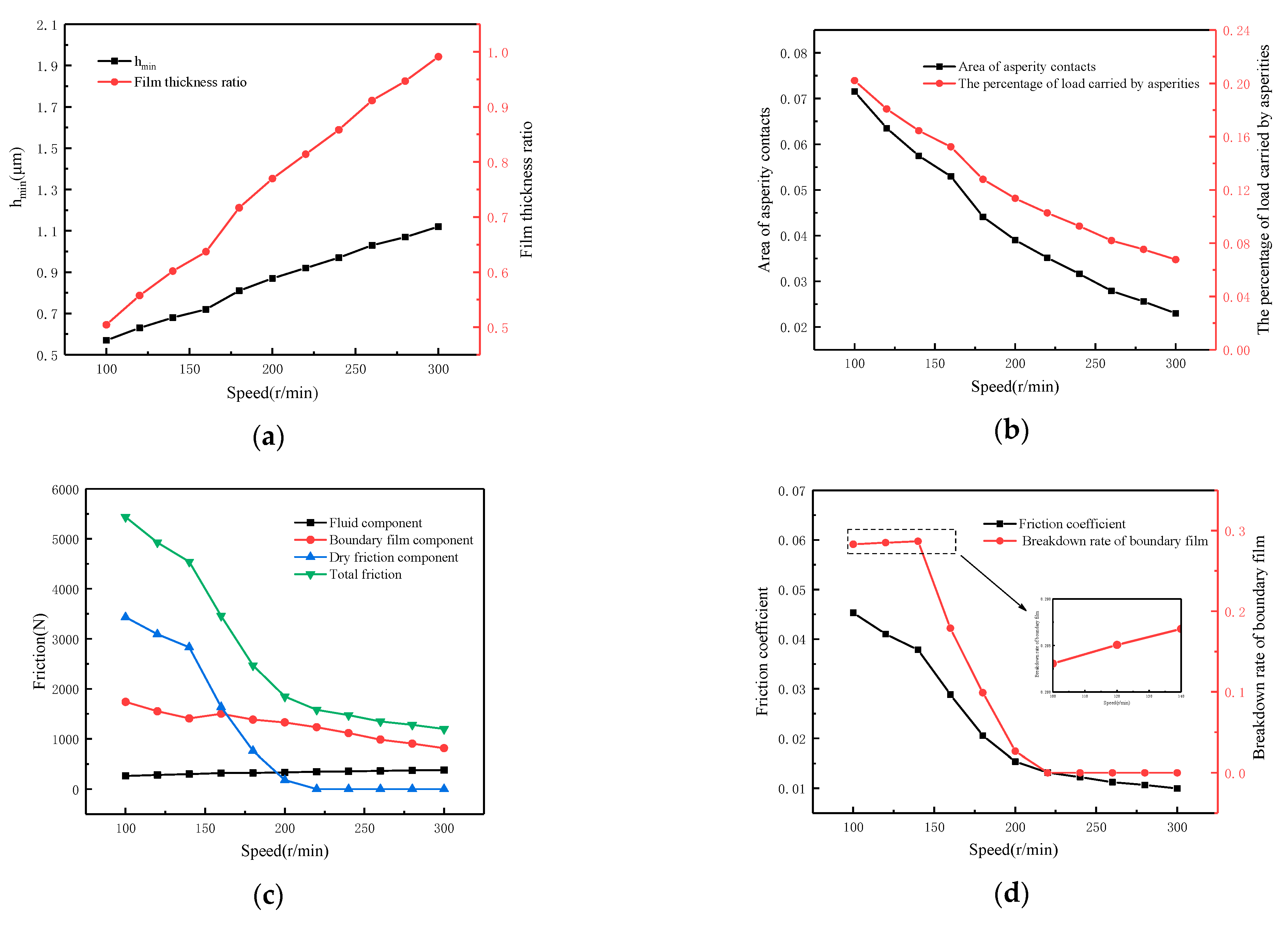

5.1. The Influence of Sliding Speed

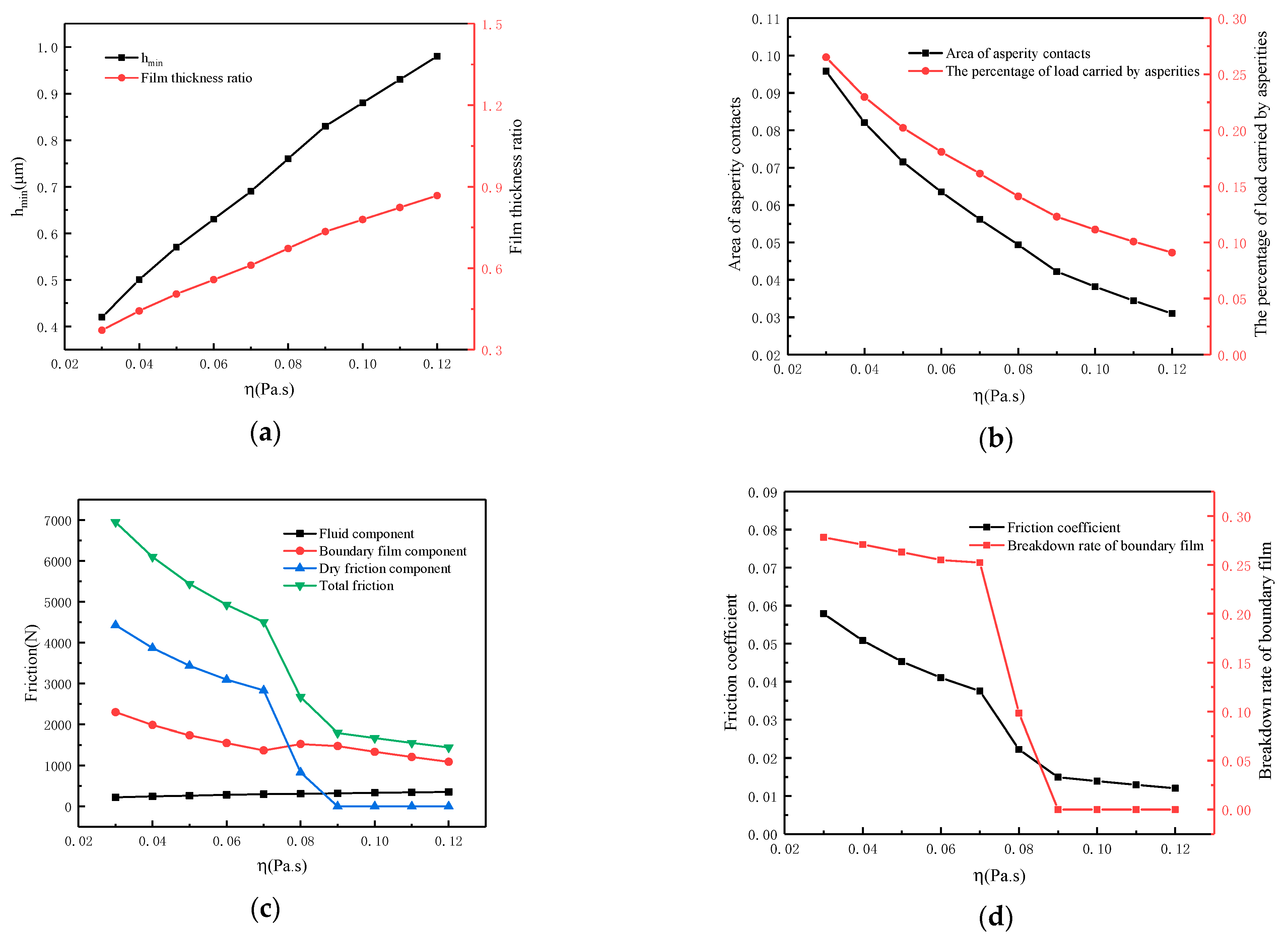

5.2. The Influence of Lubricant Viscosity

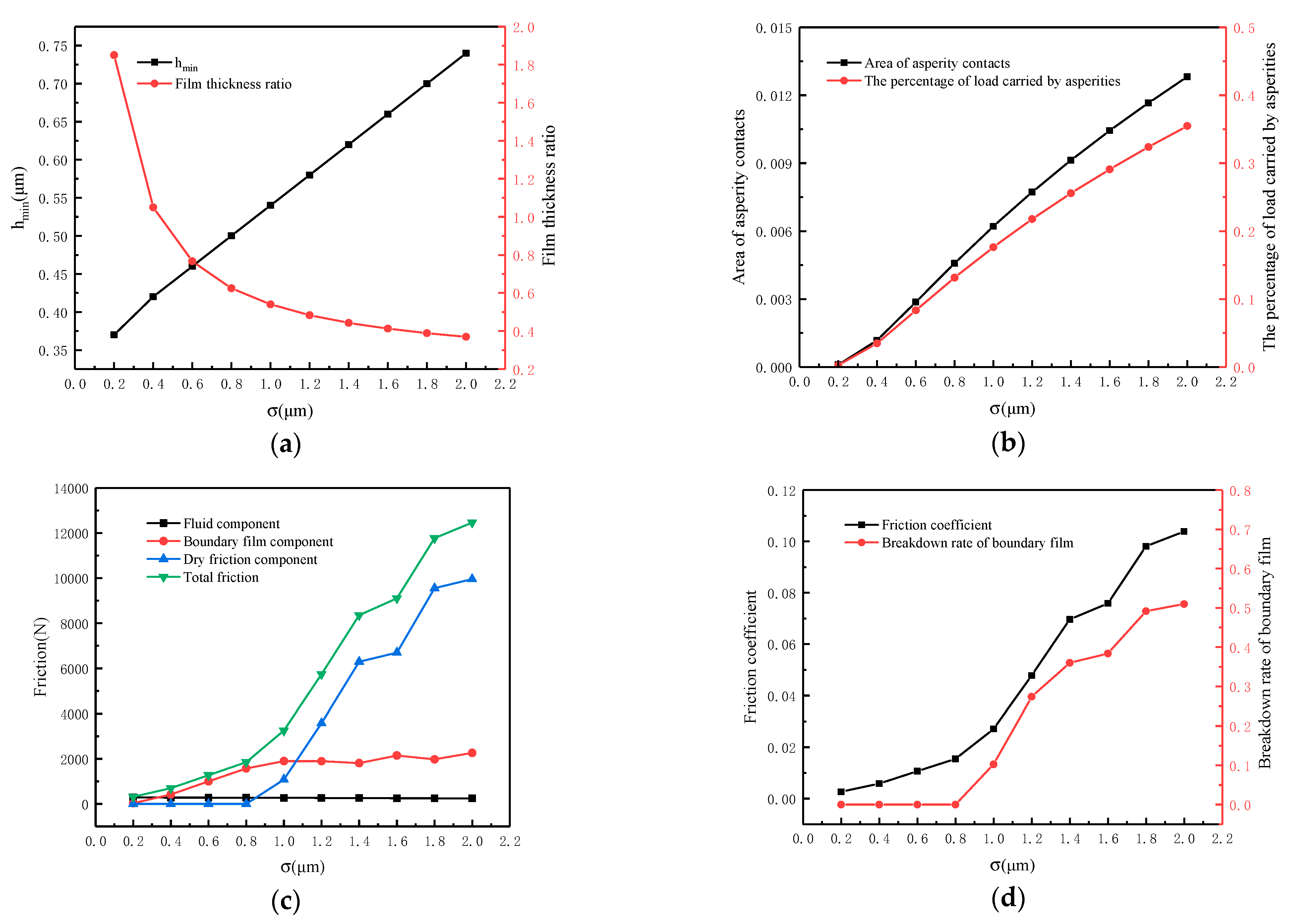

5.3. The Influence of Roughness

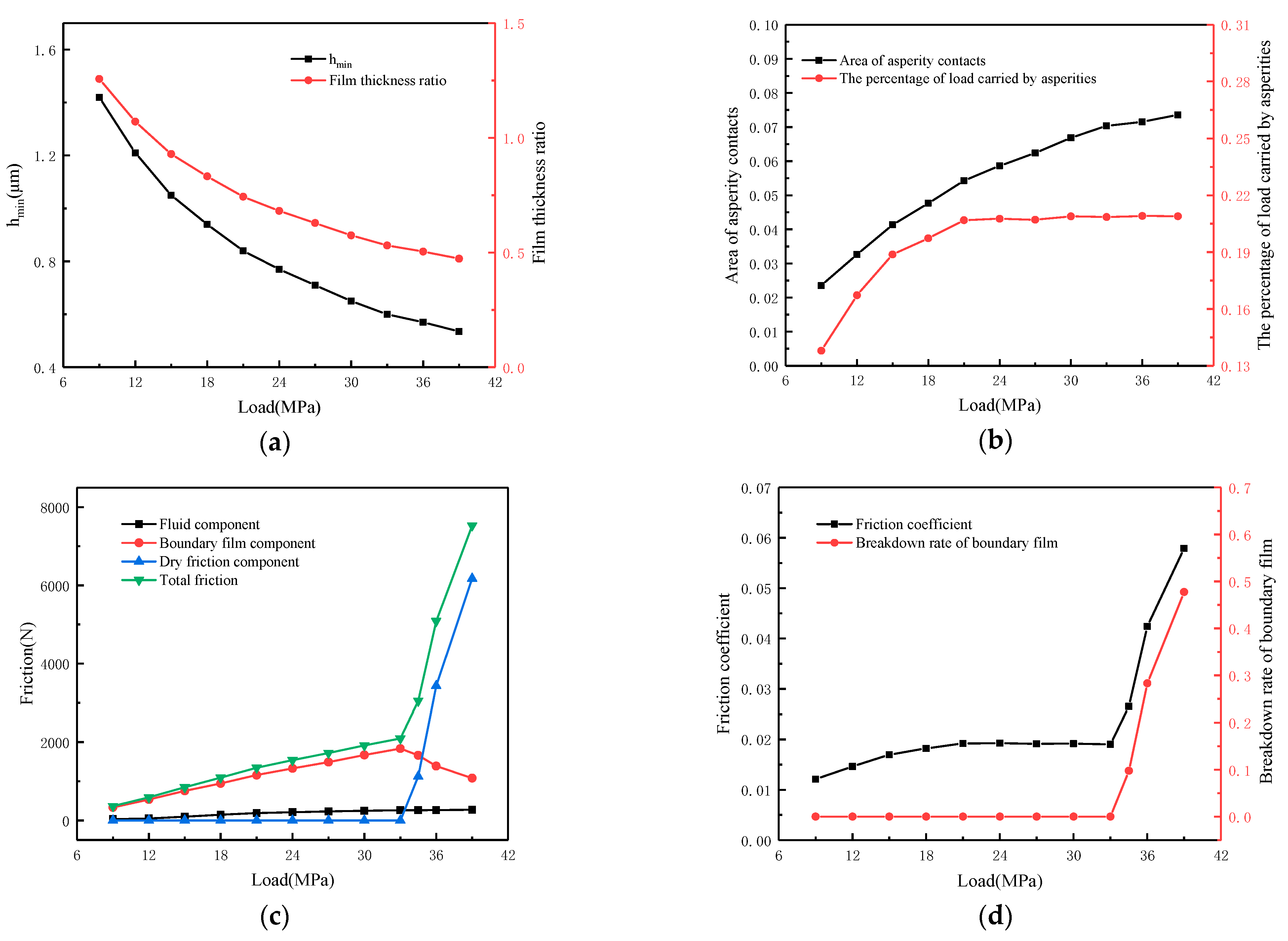

5.4. The Influence of Load

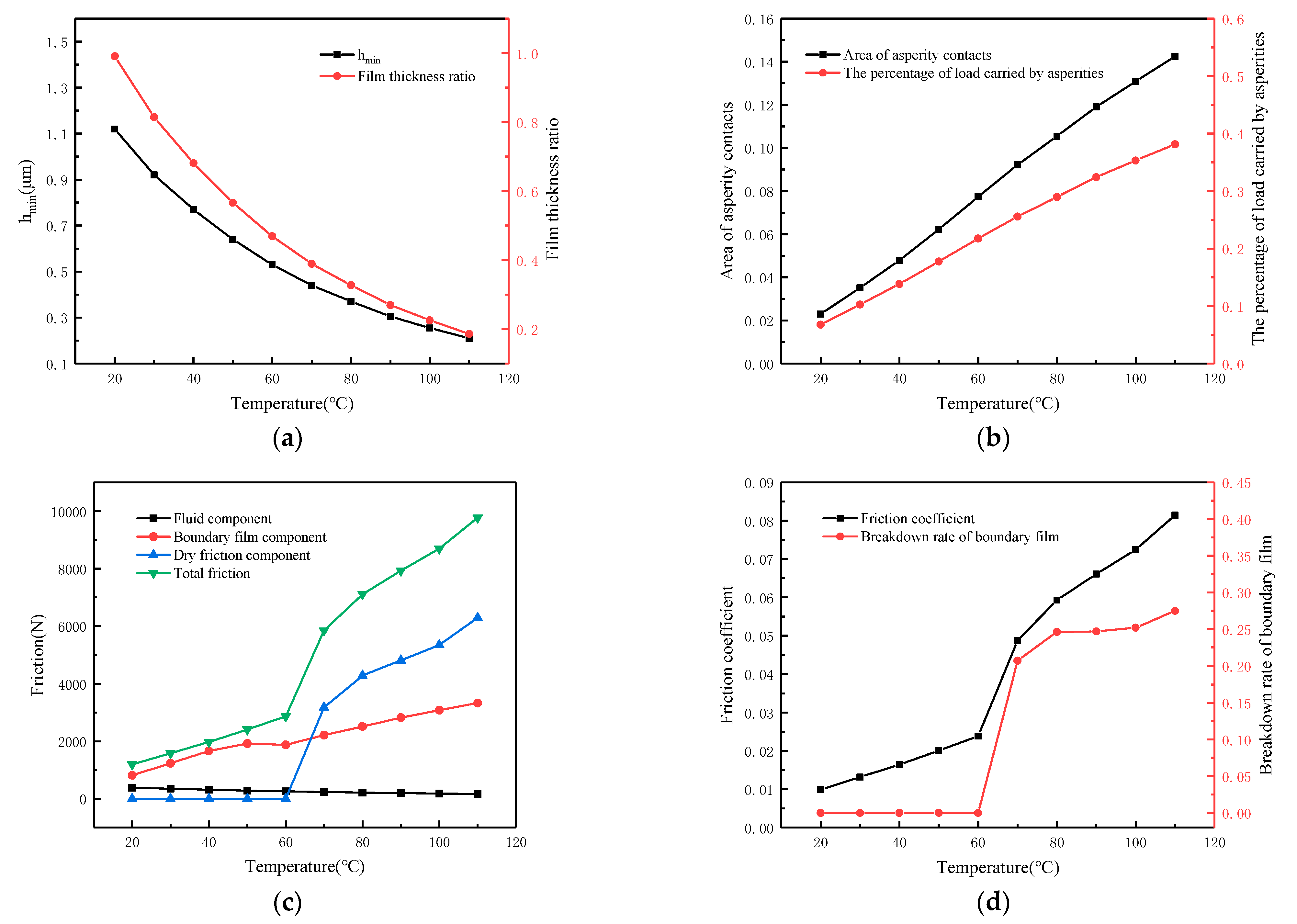

5.5. The Influence of Temperature

6. Conclusions

- The test results show that film thickness, pressure, shear stress and temperature are the key factors affecting the strength of boundary film. This paper developed an empirical boundary film strength model, and its parameters can be obtained from the test results, which is easier for engineering applications.

- A mixed lubrication model considering the boundary film strength was established. It can predict the transition of lubrication status and effectively reflect the tribological characteristics and action ratios of the fluid, boundary film and dry friction components under different working conditions.

- Low speed and low viscosity are not conducive to the formation of oil film. Properly increasing speed and viscosity can avoid the breakdown of boundary film and metal-to-metal direct contact. When the speed is above 200 r/min or the viscosity is higher than 0.09 Pa·s, the boundary film breakdown rate is almost 0 and the friction coefficient is lower than 0.02.

- The roughness of the contact surface plays an essential role in mixed lubrication. Reducing the contact surface roughness can improve the lubrication performance and ultimate load of the friction pair. When the roughness is reduced from 1.8 μm to 0.8 μm, the ultimate load of the journal bearing rises from 27 MPa to 36 MPa, an increase of about 33%.

- When the load exceeds 36 MPa or the temperature is higher than 100 °C, more than 25% of the boundary film breaks and the dry friction component accounts for more than 60% of the total friction, which leads to a sudden increase in the friction coefficient. Therefore, it is important to select an appropriate load range and ensure sufficient heat dissipation for the friction pair.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, G.; Wetzel, B.; Wang, Q. Tribological behavior of PEEK-based materials under mixed and boundary lubrication conditions. Tribol. Int. 2015, 88, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hua, M.; Dong, G.N.; Zhang, D.Y.; Chin, K.S. A mixed lubrication model for studying tribological behaviors of surface texturing. Tribol. Int. 2016, 93, 583–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagdeviren, O.E.; Acikgoz, O.; Grutter, P.; Baykara, M.Z. Direct imaging, three-dimensional interaction spectroscopy, and friction anisotropy of atomic-scale ripples on MoS2. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2020, 4, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelio, C.; Spagnuolo, E.; Di Toro, G.; Nielsen, S.; Violay, M. Mechanical behaviour of fluid-lubricated faults. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, X.W.; Zhang, S.; Kang, J.Y.; Guo, Z.C.; Feng, B.Y.; Zhao, H.; Luo, Z.; Yu, J.; Song, W.L.; et al. Semi-convertible Hydrogel Enabled Photoresponsive Lubrication. Matter 2021, 4, 675–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.J.; Yu, Q.T.; Shen, X.J.; Chen, X.Y. A Simple Model for Scuffing Risk Evaluation of Point Contact Under Mixed Lubrication. J. Tribol. Trans. ASME 2018, 140, 31502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Chen, G.Y.; Zhao, J.; He, Y.Y.; Li, Y.L.; Luo, J.B. Coupling effect of boundary tribofilm and hydrodynamic film. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2022, 3, 100778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furey, M.J. The formation of polymeric films directly on rubbing surfaces to reduce wear. Wear 1973, 26, 369–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunsel, S.; Smeeth, M. Friction and wear reduction by boundary film-forming viscosity index improvers. SAE Trans. 1996, 105, 1831–1855. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, S.M.; Gates, R.S. Effect of materials on tribochemical reactions between hydrocarbons and surfaces. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2006, 39, 3128–3137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, J.; Fridrici, V.; Kapsa, P.; Huard, J.F. Surface topography and tribology of cast iron in boundary lubrication. Tribol. Int. 2009, 42, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, X.; Yang, X.; Xie, G.; He, F.; Wang, R.; Zhang, C.; Guo, D.; Luo, J. Superlubricity under ultrahigh contact pressure enabled by partially oxidized black phosphorus nanosheets. NPJ 2D Mater. Appl. 2021, 5, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yamada, N.; Xu, J.; Zhang, J.; Chen, Q.; Ootani, Y.; Higuchi, Y.; Ozawa, N.; Bouchet, M.B.; Martin, J.M.; et al. Triboemission of hydrocarbon molecules from diamond-like carbon friction interface induces atomic-scale wear. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaax9301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blok, H. “Seizure-Delay” Method for Determining the Seizure Protection of EP Lubricants. SAE Trans. 1939, 34, 193–220. [Google Scholar]

- Czichos, H.; Kirschke, K. Investigations into film failure (transition point) of lubricated concentrated contacts. Wear 1972, 22, 321–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czichos, H. Failure criteria in thin film lubrication—The concept of a failure surface. Tribology 1974, 7, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.A.; Barnes, C.G. Effects of Speed on Scuffing in Mixed Lubrication. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part. J. 1994, 208, 269–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Yin, Z.F.; Zhang, J.; Chen, C.I.; Hsu, S. Strength measurement of thin lubricating films. Wear 2000, 237, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huang, P. The calculation model of boundary lubrication under point contact. Int. Jt. Tribol. Conf. 2007, 48108, 85–87. [Google Scholar]

- Ajayi, O.O.; Lorenzo-Martin, C.; Erck, R.A.; Fenske, G.R. Scuffing mechanism of near-surface material during lubricated severe sliding contact. Wear 2011, 271, 1750–1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kahraman, A.; Anderson, N.; Wedeven, L.D. A model to predict scuffing failures of a ball-on-disk contact. Tribol. Int. 2013, 60, 233–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, Ł.; Mathia, T.G. Proposal of invariant precursors for boundary lubricated scuffing. Wear 2015, 340–341, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Spikes, H. On the Mechanism of ZDDP Antiwear Film Formation. Tribol. Lett. 2016, 63, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, C.; Espejo, C.; Wang, J.; Neville, A.; Morina, A. Understanding the Friction Reduction Mechanism Based on Molybdenum Disulfide Tribofilm Formation and Removal. Langmuir 2018, 34, 13523–13533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, B.; Yu, Y.; Cho, Y.-J. A scuffing model considering additive depletion in boundary lubrication. Ind. Lubr. Tribol. 2019, 72, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, B.; Meng, X.; Zhang, R.; Wen, C. A deterministic contact evolution and scuffing failure analysis considering lubrication deterioration due to temperature rise under heavy loads. Eng. Failure Anal. 2021, 123, 105276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, Ł.; Mathia, T.G. Focus on the concept of pressure-velocity-time (pVt) limits for boundary lubricated scuffing. Wear 2018, 402–403, 179–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.L.; Chen, W.B.; Yan, Z.J.; Zhang, S.F. Study on lubrication state of cylinder liner-piston ring based on resistance measurement method. Lubr. Sci. 2020, 32, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, H. Tribological Evaluation of Electrical Resistance of Lubricated Contacts. J. Tribol. 2020, 142, 114502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, R.L.; Angadi, S. Modelling of Lubricated Electrical Contacts. Lubricants 2022, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katiyar, J.K.; Sinha, S.K.; Kumar, A. Lubrication Mechanism of SU-8/Talc/PFPE Composite. Tribol. Lett. 2017, 65, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrock, B.J.; Dowson, D. Isothermal Elastohydrodynamic Lubrication of Point Contacts Part II—Ellipticity Parameter Results. J. Lubr. Technol. 1977, 99, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, J.A.; Tripp, J.H. The Contact of Two Nominally Flat Rough Surfaces. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. 1970, 185, 625–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.L.; Tevaarwerk, J.L. Shear Behaviour of Elastohydrodynamic Oil Films. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1977, 365, 215–236. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tian, Y.; Li, K.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J. Reynolds boundary condition realization in journal bearings: Location of oil film rupture boundary with layering-sliding mesh method. Tribol. Int. 2022, 165, 107330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zheng, L. An Average Reynolds Equation for Partial Film Lubrication with a Contact Factor. J. Tribol. 1989, 111, 188–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patir, N.; Cheng, H.S. Application of the Average Flow Model to Lubrication Between Rough Sliding Surfaces. J. Tribol. 1979, 101, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.L. Contact Mechanics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Tian, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yang, J. Reynolds Boundary Condition Approximation in Journal Bearings Based on Dynamic Mesh Method. Tribol. Online 2021, 16, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighton, M.; Morris, N.; Rahmani, R.; Rahnejat, H. Surface specific asperity model for prediction of friction in boundary and mixed regimes of lubrication. Meccanica 2016, 52, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawczyk, J.; Morgan, N.; Russo, J.; Spikes, H. Film Thickness and Friction of ZDDP Tribofilms. Tribol. Lett. 2019, 67, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.I.; Sherrington, I. A simplified approach to the prediction of mixed and boundary friction. Tribol. Int. 2022, 175, 107836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Radius of the upper sample, Rx | 0.025 m |

| Radius of the lower sample, Ry | 0.004 m |

| Equivalent elastic modulus, E | 148 GPa |

| Surface RMS roughness, σ | 0.59 μm |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Bearing radius, R | 0.05 m |

| Bearing width, b | 0.133 m |

| Speed, N | 459 r/min |

| Radius clearance, c | 0.000145 m |

| Lubricant viscosity, η0 | 0.0127 Pa·s |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Load, W | 9~38 MPa |

| Speed, N | 50~300 r/min |

| Bearing radius, R | 0.05 m |

| Bearing width, b | 0.033 m |

| Equivalent elastic modulus, E | 105 GPa |

| Surface RMS roughness, σ | 1.13 μm |

| Radius clearance, c | 0.0001 m |

| Ambient temperature, T0 | 55 °C, 70 °C |

| Lubricant viscosity, η0 | 0.05, 0.033 Pa·s |

| The friction coefficient of the boundary film, μa | 0.1 |

| Eyring stress of the lubricant, τ0 | 10 MPa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, S.; Yan, Z.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Sun, H.; Wu, S. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Mixed Lubrication Considering Boundary Film Strength. Materials 2023, 16, 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031035

Zhang S, Yan Z, Liu Z, Jiang Y, Sun H, Wu S. Experimental and Numerical Study of the Mixed Lubrication Considering Boundary Film Strength. Materials. 2023; 16(3):1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031035

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Shengwei, Zhijun Yan, Ze Liu, Yuanyuan Jiang, Haocheng Sun, and Shibo Wu. 2023. "Experimental and Numerical Study of the Mixed Lubrication Considering Boundary Film Strength" Materials 16, no. 3: 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031035

APA StyleZhang, S., Yan, Z., Liu, Z., Jiang, Y., Sun, H., & Wu, S. (2023). Experimental and Numerical Study of the Mixed Lubrication Considering Boundary Film Strength. Materials, 16(3), 1035. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma16031035