3.1. Solutions and Films of 2416SL

To determine the structure of electron-vibrational and exciton transitions in 2416SL, the absorption and PL spectra of aqueous and DMSO solutions at different concentrations were studied. Furthermore, the spectra of 2416SL films deposited on quartz provided additional insight. Absorption (

Figure 2, curves 1,3) and PL (

Figure 2, curves 2,4) spectra for low concentration (5·10

−6 M) solutions of 2416SL in water and DMSO at 296 K have variations, which can be associated with their different solubility. The positions of the maxima of the electronic and electronic-vibrational bands in the absorption and PL spectra (

Figure 2) of solutions of 2416S in water and DMSO are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2.

The spectra in DMSO (

Figure 2) are mirror symmetric, have a Stokes shift of 530 cm

−1, and oscillating repetitions with a frequency close to 1330 cm

−1 forming solid evidence that the spectra are of molecular origin. Absorption spectra for aqueous solutions of 2416SL (

Figure 2 and

Figure 3a) are lacking mirror symmetry between the absorption and PL spectra. There is a significantly reduced light absorption in the region of the purely electronic S

0(0) → S

1(0) optical transition, and a high intensity 502 nm band, approximately in the region of S

0(0) → S

1(1) transition. In the present work, only aqueous solutions of 2416SL are studied in detail, because aqueous solutions of CdTe and their mixtures with 2416SL are the focus of this study. The absence of mirror symmetry between the absorption and PL spectra of aqueous solutions, additional absorption in the short wavelength region, and reduced contribution of molecular spectral signatures evidence that, even at low concentrations, H-aggregates are formed. Therefore, the absorption and PL spectra are formed not only by molecular but also by collective excitations in the aggregates, and disk-like molecules of 2416SL aggregate into thread-like columnar structures with a diameter equal to the size of the molecule. Furthermore, the perylene derivatives are well-known for forming H-aggregates, where molecules are positioned almost parallel to each other [

23]. Such one-dimensional molecular aggregates have features characteristic of collective excitations (excimers, FE [

11,

12], CTE [

24,

25,

26]).

Due to the stacking parallel orientation of molecules and their dipoles in molecular H-aggregates in solutions and films, their PL of FE is significantly quenched in comparison to an isolated molecule. This is happening because optical transitions for FE in H-aggregate absorption and PL between S

0(0) ↔ S

1(0) electronic states are forbidden [

16]. However, the strict prohibition of S

0(0) ↔ S

1(0) transitions is valid, only for excitation delocalized along an infinite crystal [

16]. In real crystals, the effect of dipole ordering depends on the exciton coherence length. In molecular aggregates and thin polycrystalline films, the coherence length decreases due to thermal and structural disorder [

26,

27,

28], and optical S

1(0) → S

0(1) transitions to higher electronic vibrational states of the S

0(1) ground state are allowed, albeit with a smaller intensity. This can be related to the characteristic features of the absorption spectra for aqueous solutions of 2416SL at different concentrations (

Figure 3), there is a lack of mirror symmetry between the electronic absorption and PL spectra at room temperature, as well as very low absorption in the region of the purely electronic S

0(0) → S

1(0) transition and a significant intensity of the 502 nm band, approximately in the region of the allowed S

0(0) → S

1(1) transition. The above features of absorption and PL spectra for aqueous solutions of 2416SL can be explained by the manifestation of FE in H-aggregates, which are formed in these solutions.

For aqueous solutions of 2416SL of different concentrations, starting from 5·10

−6 M and more, changes in the PL spectra at room temperature are much more significant than in the absorption spectra (

Figure 3). Two bands with maxima at 550 and 594 nm can be distinguished in the steady-state PL spectrum of aqueous solutions for 2416SL at concentrations of 10

−4 M (

Figure 3b, curve 1). The position of the maximum of the first PL band corresponds to the S

1(0) → S

0(0) transition of the molecular solution, and the second maximum reflects the S

1(0) → S

0(1) transition of the H-aggregate, as this band is getting dominant in the high concentration solutions. An increase in the concentration from 5·10

−6 M to 10

−4 M leads to a significant drop in the intensity of the purely electronic S

1(0) → S

0(0) transition, and the intensity of the 594 nm band of the S

1(0) → S

0(1) transition relatively increases (

Figure 3b, curve 1). At the concentration increased to 10

−3 M, only a band with a maximum of 589 nm and a weak shoulder at 626 nm is observed in the PL spectrum (

Figure 3b, curve 2).

The absorption spectrum of the aqueous solution of 2416SL (8·10

−2 M) changes significantly with a temperature drop from 297 K (

Figure 3a, curve 3) to 77 K (

Figure 3a, curve 4). In the absorption spectrum at 77 K, the intensity of absorption at a longer wavelength increases dramatically and a new band of 571 nm appears. The presence of this band at low temperatures can be associated with structural changes in H-aggregates, a manifestation of their excitonic properties and the formation of low-temperature CTEs.

For the 10

−3 M solution at 4.2 K, the intensity of the PL bands at 589 and 626 nm decrease to practically zero, and only bands with maxima at 685 and 745 nm are observed in the PL spectrum (

Figure 3b, curve 3). The dramatic reduction of the 589 and 626 nm bands is characteristic of excimer emission [

12]. In solutions, 2416SL molecules form elongated disc-like aggregates and, in such one-dimensional molecular aggregates, the formation of excimers has already been established [

12]. Excimers should not be confused either with CTE states, which involve significant charge transfer between molecules, or with FEs, which characterize the coherent excitation of a crystal. An excimer is an optically excited dimer stabilized by resonance interaction. A necessary condition for the formation of excimers is a small distance between molecules, which is usually achieved due to effective π-stacking [

16] and the convergence of molecules in an excited state. The ground state of excimers is antibonding; therefore, excimers have no direct absorption in the ground state and must be excited by energy transfer. The excimer radiation is characterized by a broad structureless band of PL. In 2416SL nanoaggregates, as in pyrene and α-perylene, several types of excimers can be realized [

12]. In our case, the 2416SL excimers are featured by PL bands of 589 and 626 nm.

Changes in the PL spectra of the aqueous solutions at different concentrations can be associated with a manifestation of collective excitations of FEs, excimers, and CTEs in H-aggregates [

7,

12]. For molecular aggregates of perylene derivatives, CTEs play a significant role in PL [

6,

7,

12,

24,

25,

26,

29]. Comparative analysis of absorption and PL spectra for 2416SL in solutions and condensed state allows us to determine the nature of these collective excitations.

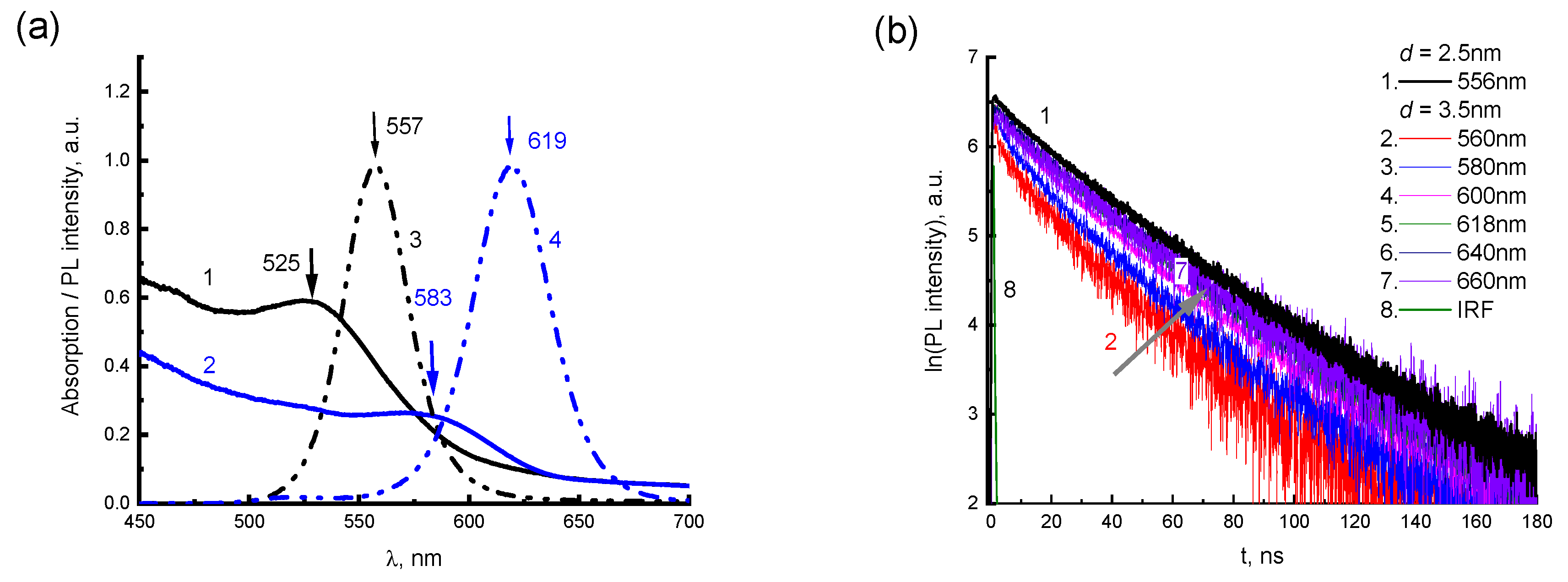

Figure 4 shows the spectra of absorption (

Figure 4, curves 2,3) and steady-state PL (

Figure 4, curves 4,5) of 2416SL films, before (

Figure 4, curves 2,5) and after thermal annealing (

Figure 4, curves 3,4). The absorption spectra of the films after thermal annealing (

Figure 4) are more structured than the absorption spectra of nanoaggregates in solutions and are more like the absorption spectra of PTCDA films [

6,

7]. Such spectral changes can be associated with structural changes in the aggregates after thermal annealing. In the spectra of thermally annealed films, clearly expressed CTE absorption maxima at 556 (CTE

1) and 589 nm (CTE

2) appear (well evidenced by differential spectrum in

Figure 4, curve 6). These maxima correspond to Franck-Condon’s non-relaxed optical CTE states [

14,

15]. The PL bands, which correspond to the emission of relaxed exciton states, have maxima at 636, 680, and 750 nm. The nature of the absorption and PL spectra in

Figure 4 will be analyzed below.

CTE occupying an intermediate place in the classification of excitons based on their internal structure have the charge or its part transferred to a neighboring molecule due to photoinduced electron transfer [

13,

14,

15]. With incomplete charge transfer, the wave function of the resulting state can be delocalized within two or more molecules and have both excitonic and ionic features. If the excitonic character prevails, CTE can coherently move along the crystal. Unrelaxed CTEs are formed directly upon optical excitation and appear in the absorption spectra. Due to a large static dipole moment (up to 25 Debye on the nearest molecules), CTEs can be a cause of a large nonlinear second-order polarizability and a strong electroabsorption. CTEs have a strong tendency to self-localize. They polarize the surrounding molecules, which leads to the relaxation of the crystal lattice into a new equilibrium. If the time of CTE excitation at the lattice nodes is longer than the lattice relaxation time, the excitation is accompanied by local deformation of the lattice and the formation of the excitonic polaron—CPE [

14]. Relaxed molecular-polaron excitons (CPE) are a characteristic feature of molecular crystals. CPEs appear as intermediate states in the processes of photogeneration and radiative recombination of CTE states.

In addition to excimer radiation in the long-wavelength region of the PL spectrum for concentrated solutions of 2416SL (

Figure 3), weakly intense bands of 680 and 750 nm can be distinguished. These bands are also observed in the spectra of 2416SL films at room temperature (

Figure 4). When the 2416SL solution is cooled to 4.2 K, the PL intensity in this spectral region increases significantly and the bands at 685 and 745 nm appear in the spectra (

Figure 3b, curve 3). The PL emission of the bands at 680 and 750 nm can be associated with CPE

1 and CPE

2, respectively.

Electronic states in quasi-one-dimensional molecular crystals of the PTCDA type with a strong overlap of molecular orbitals were comprehensively analyzed [

3,

6,

7,

12,

24,

25,

26,

29]. In such quasi-one-dimensional crystals, due to the small, less than 0.35 nm, intermolecular distance, there is a strong overlap of the π-orbitals of neighboring molecules. In such crystals, the difference between FE and CTE energies becomes small, and their strong mixing determines the nature of the lowest exciton states [

7,

13,

30,

31]. As soon as the energy difference between CTE and FE becomes small, both types of excitons can interact, and new mixed excitonic states are formed. At FE and CTE being close in energy, the FE band admixes some CTE states and shifts down, and CTE also shifts up, acquiring some energy of the FE state, and becomes optically allowed. These mixed FE-CTE states exhibit the properties of two types of excitons: FE provides a high oscillator strength, and CTEs lead to high sensitivity in external electric fields. Such exciton mixing can also result in a noticeable transition dipole for CTE [

7]. This can explain the spectral dependence of the PTCDA films on their thickness in the range of 0.3–10 nm when the effects of quantum confinement become important [

32]. In finite chains, simultaneously with excitonic “bulk” states, “surface” states can also arise [

33]. The “surface” states are localized at the end of the chain and can be shifted to the blue or red region of the spectrum compared to the bulk states. Thus, PL in 2416SL nanoaggregates can be caused by direct excitation due to the borrowing of some transition oscillator strength from intense transitions with subsequent radiative recombination or thermally activated decay into free charge carriers. In 2416SL having a strong tendency for mixing of FEs and CTEs, the CTEs play a significant role in PL emission.

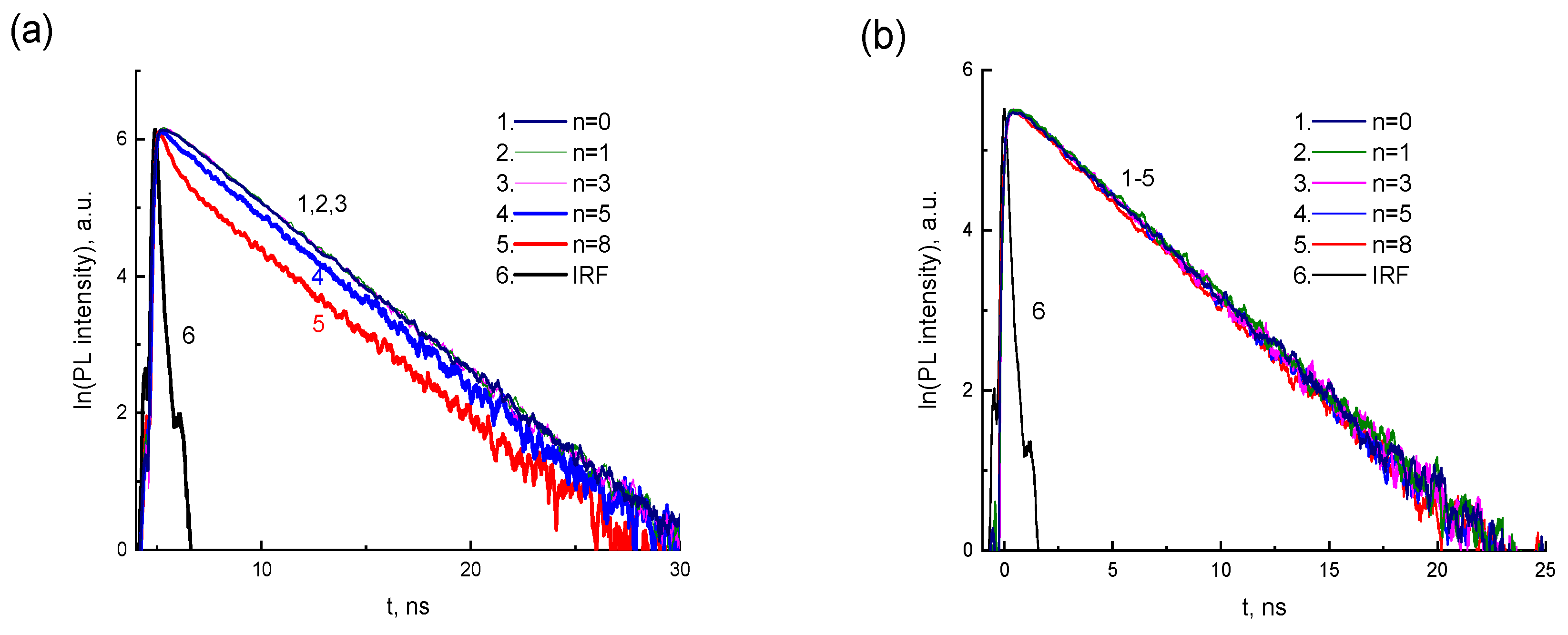

Registration of the dependence of the PL intensity on the decay time

t was carried out for radiation wavelengths

λEM = 550 and 590 nm corresponding to molecular and H-aggregate emissions, respectively. The PL decays for

λEM = 550 nm at the concentration of 10

−4 M are well described by a single-exponential function and feature molecular emission. The kinetics of PL decay for

λEM = 590 nm at the concentration of 10

−3 M have a good fit by a biexponential function with fast and slow components of lifetimes

τ. This can be attributed to the emission of molecular and aggregated forms of 2416SL.

Table 3 shows the values of

τ calculated for the PL kinetics of 2416SL.

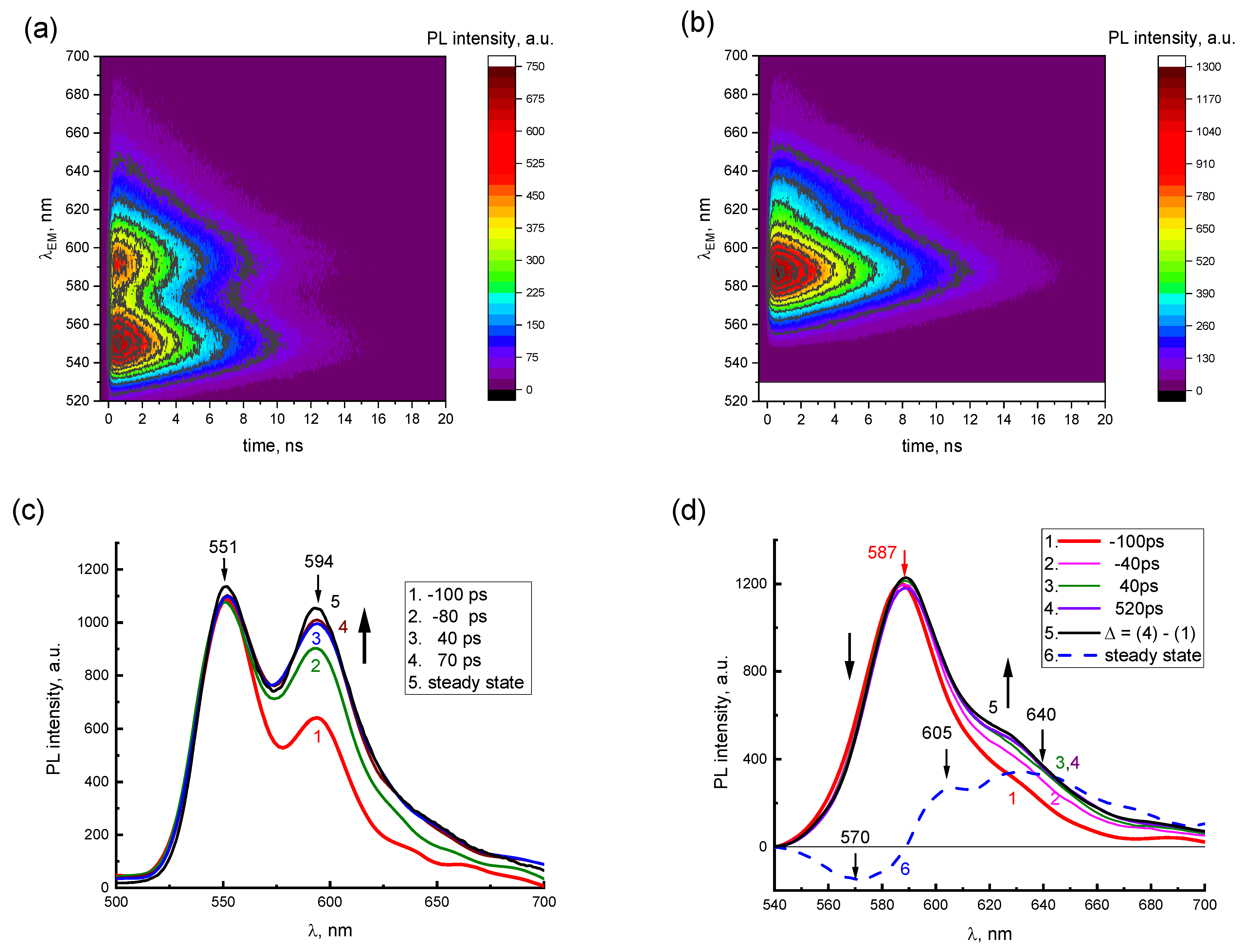

The presence of two emission components in the PL spectra of concentrated 2416SL solutions is demonstrated in TRES maps (

Figure 5a,b) and instantaneous PL spectra (

Figure 5c,d). In TRES maps, the dependence of the PL intensities vs.

t and

λEM for aqueous solutions of 2416SL at the concentrations of 10

−4 (

Figure 5a) and 10

−3 M (

Figure 5b) is shown. PL emission wavelengths (520–700 nm) and delay times (0–20 ns) are plotted on the vertical and horizontal axes, respectively, whereas PL intensity is a function of color in relative units. For 2416SL concentration of 10

−4 M (

Figure 5a), two PL bands with maxima at 551 and 594 nm can be distinguished in the TRES map. When the concentration of 2416SL increases to 10

−3 M (

Figure 5b), the intensity of the band at 551 nm decreases significantly, and only the band at 589 nm remains.

In

Figure 5c,d, instantaneous PL spectra are presented for aqueous solutions of 2416SL at various delay times

t and concentrations, using the data of TRES maps in

Figure 5a,b. The instantaneous PL spectra are normalized by the most intense PL bands in the steady-state spectra. These are bands with emission maxima at 551 nm and 589 nm for the concentration of 10

−4 (c) and 10

−3 M (d), respectively. Negative values of delay times mean that instantaneous PL spectra were recorded at the leading edge of the laser pulse. It can be seen from

Figure 5c that at short delay times of −100 ps, the instantaneous PL spectra are similar to the molecular spectra of

Figure 3, and already at delay times of 40 ps, they coincide with the steady-state PL spectra (

Figure 5c, curves 3,5), which is also manifesting contribution of the aggregated form of 2416SL.

Figure 5d shows the instantaneous PL spectra for aqueous solutions of 2416SL at the concentration of 10

−3 M, which reflect the time dependence of the instantaneous spectra of the aggregated form of 2416SL. In the time delay of around 40 ps, the instantaneous PL spectra reach an equilibrium value and become similar to the steady-state PL spectra (

Figure 5d, curves 3,5). A relative decrease in PL on the long-wavelength side of the 589 nm band is also observed. The presented difference spectrum (

Figure 5d, curve 6), obtained by subtracting the instantaneous spectra at the time delay of 520 and −100 ps (

Figure 5d, curves 4,1), has bands with maxima at 570, 605, and 640 nm. Analysis of the instantaneous PL spectra (

Figure 5) and the lifetimes (

Table 3) allows ones to conclude that the band maxima at 551, 589, 626, 685 and 745 nm are of different natures. PL in these bands has different lifetimes and differs in temperature dependence.

3.3. Mixing of Excitons in Hybrid Systems of CdTe-2416SL

QDs of CdTe stabilized by thioglycolic acid are negatively charged and can adsorb on the surface positively charged molecules by Coulombic attraction. 2416SL molecules have a positive charge (

Figure 1) and can be attached to the surface of CdTe due to electrostatic interaction.

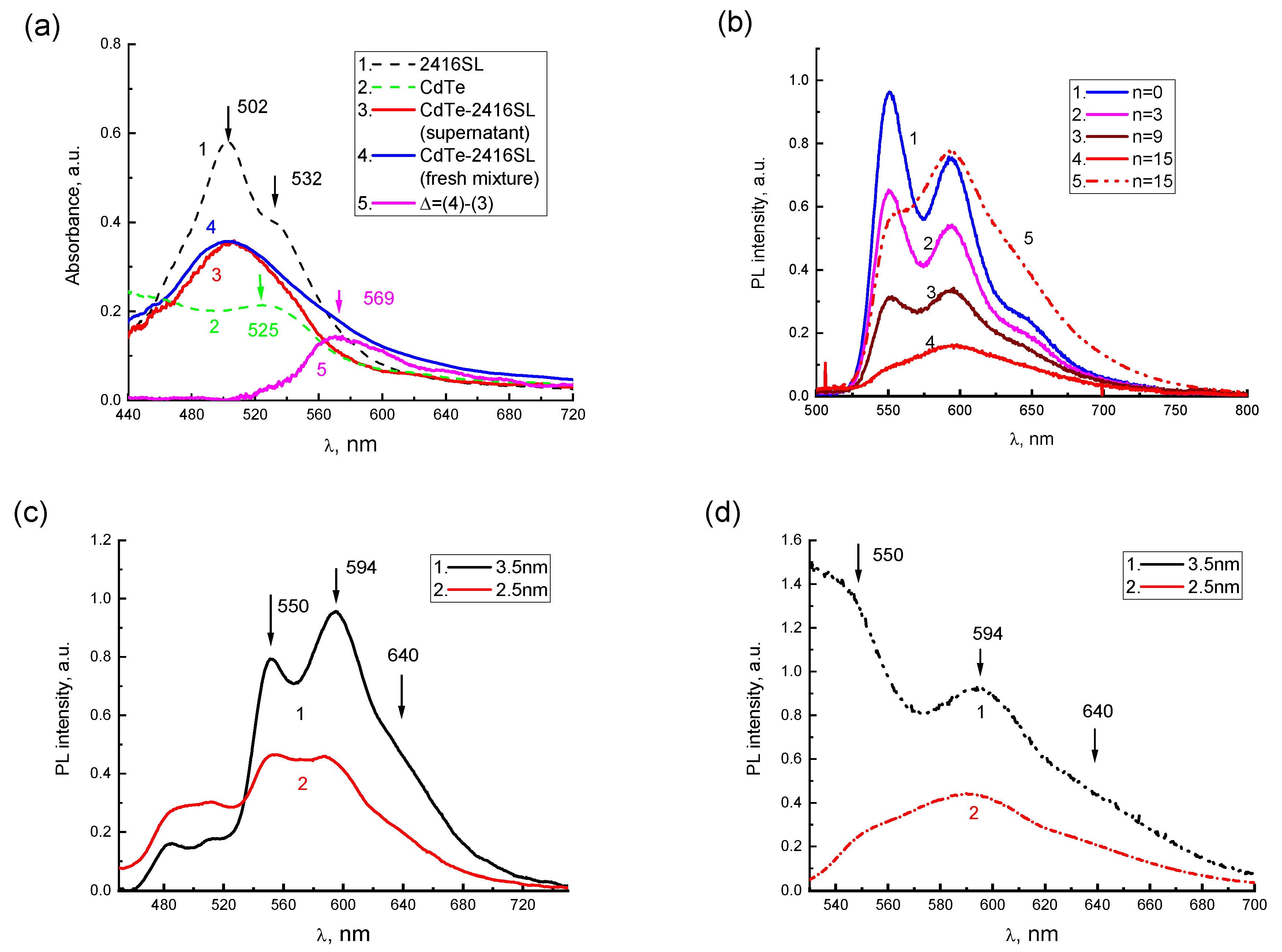

After the mixture of CdTe-2416SL at

n = 15, a broad absorption band (

Figure 7a, curve 3) with a maximum at 504 nm was observed. In

Figure 7a, the absorption spectra of the aqueous solutions of neat 2416SL (

Figure 7a, curve 1) and initial dispersions of CdTe (

Figure 7a, curve 2) are shown as a reference. A part of the formed CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates gradually precipitate. To analyze the spectral features of the nanoaggregates, absorption spectra of CdTe-2416SL supernatant without precipitate (

Figure 7a, curve 3) and freshly mixed CdTe-2416SL with all the nano-aggregations present (

Figure 7a, curve 4) were compared. The spectrum of freshly mixed CdTe-2416SL represent a superposition of the absorption of the supernatant and precipitated aggregate. The differential spectrum, Δ, (

Figure 7a, curve 5) obtained by subtraction of the supernatant spectrum from freshly mixed CdTe-2416SL spectrum demonstrate spectral features of the CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates. The differential absorption spectrum, which is characterized by a new absorption band with a maximum at 569 nm, can be associated with light absorption by CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates. The new absorption band that appears in the hybrid structures of CdTe-2416SL (

Figure 7a) can be associated with the hybridization of CTE and WME at the interface of 2416SL and CdTe.

The addition of the CdTe dispersions to the solution of 2416SL resulted in significant quenching of 2416SL emission with the most intense relative quenching of PL in the 550 nm band (

Figure 7b). The band with a maximum at 595 nm featuring H-aggregated 2416SL remains in the PL spectrum of CdTe-2416SL mixtures and becomes more prominent upon excitation with

λe = 510 nm (

Figure 7b, curve 5) evidencing efficient absorption responsible for this emission. This behavior of the absorption and PL spectra can be associated with the formation of CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregate structures, as the observed emission is different to the features of H-aggregate and molecular PL of neat 2416SL. Importantly, the PL of CdTe QDs, which have a high quantum yield in the dispersions, was not observed. Strong quenching of QDs emission can be associated with the hybridization of WME in the CdTe QDs with the CTE states at the interface of 2416SL and CdTe and the formation of mixed exciton states—CTE-WME.

PL spectra of CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates based on CdTe QDs with a diameter of 3.5 and 2.5 nm (

Figure 7c,d) are similar featuring intense PL bands with maxima at 550, 594 and 640 nm. The bands are associated with the formation of CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates. The difference between these spectra can be attributed to the change of spectral positions of excitonic transitions for QDs of various diameters.

Figure 8 shows the PL kinetics of CdTe-2416SL mixtures for two

λEM (550 nm in

Figure 8a and 620 nm in

Figure 8b) depending on the concentration of CdTe QDs. The measured PL lifetimes for the above wavelengths are shown in

Table 5. According to the PL kinetics, the PL lifetime in the 620 nm band does not depend on the CdTe concentration. The PL intensity and lifetime in the 550 nm band decrease with increasing CdTe concentration, which can be associated with the processes of CdTe-2416SL formation and energy transfer in them. Förster resonant energy transfer (FRET) mechanism could be involved in studied CdTe-2416SL nanostructures.

2416SL-CdTe nanocomposites arise due to the electrostatic interaction between the columnar nanoaggregates of 2416SL and CdTe QDs. A new band with a maximum of 569 nm appears in the absorption spectra of the mixtures (

Figure 7a, curve 5), which can be associated with the mixed exciton states—CTE-WME. The band with a maximum at 594 nm in the PL spectra of mixtures can also be attributed to the emission of mixed CTE-WME states. Such states arise due to the close position of CTE of 2416SL and WME in CdTe QDs. Electronic states and resonant energy transfer in hybrid nanostructures containing organic and inorganic semiconductor materials were studied before [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. The high efficiency of non-radiative energy transfer from semiconductor nanostructures (quantum wells/QDs) to organic material with overlapping electronic excitation spectra has been demonstrated [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The time of energy transfer for WME to organic matter is less than the exciton lifetime in the absence of an organic coating [

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In our case, significant changes of the PL spectra in the emission ranges of 2416SL and CdTe QDs are observed for the mixtures. The intensity and lifetime of PL in the emission band of CdTe-2416SL nanoaggregates (550 nm band) decrease with increasing CdTe concentration, which can be associated with FRET and formation of CdTe-2416SL nanostructures.

For FRET, the rate of energy transfer depends on the degree of overlapping of the PL spectrum of the donor and the absorption spectrum of the acceptor, the mutual orientation of the transition dipole moments, and on the distance

R between the interacting molecules [

40,

41]. As a result of FRET, the fluorescence quantum yield of the donor

φd and the lifetime of the excited state of the donor

τd decrease compared to the intrinsic radiation time

τD, since an additional channel for reducing the population of the excited state of the donor with the migration constant

km appears. If the donor and acceptor molecules are at a distance

R ≠

R0 from each other, then the ratio between the characteristic migration time

τm =

km−1 and the intrinsic radiation lifetime of the excited state of the donor:

where

R0 (Förster radius) is the characteristic distance, at which the probability of FRET is equal to the probability of spontaneous fluorescence of the donor molecule and is determined by the condition

km·τD = 1. In the first case of potential FRET, the 2416SL with absorption of 502 and 532 nm and PL emission peaking at 549 and 591 might be a donor, and the QDs would act as an acceptor. Absorption levels of QDs with

d = 2.5 nm are not having much of overlap for the above FRET conditions to be met properly. However, for 2416SL adsorbed on the QDs with a diameter of 3.5 nm, the above conditions for energy transfer are reasonably satisfied. The emission band of 2416SL overlaps with the absorption band of 3.5 nm CdTe QDs having a maximum of about 583 nm. Furthermore, it needs to be admitted that there is practically no PL emission from the QD levels for the mixtures due to formation of CTE-WME states with low quantum yield. Another case of potential FRET process might involve CTE states of 2416SL (absorption maxima at 556 and 589 nm) that could act as acceptors of energy from QDs levels. The photon energy absorbed by CTEs could quickly relax to CPE levels of emission, but due to CTE-WME hybridization the absorbed energy more likely to relax on the CTE-WME levels as these levels have much longer lifetime, and the emission would be observed from these mixed levels. Therefore, the FRET from the QDs to CTE is unlikely process. Overall, the hybrid CdTe-2416SL nanostructures with strong quenched emission of QDs might be applied in dissociative sensing. Such sensors would work by enabled interaction of the perylene dye with an analyte, leading to the dissociation of the nanostructures and an emergence of strong PL emission of the QDs. Current research provides a fundamental understanding for the emission of the hybrid CdTe-2416SL nanostructures and further studies toward sensing would be pursued to provide clear insight into the above applications.

The energy diagram is proposed in

Figure 9 to elucidate various types of exciton transitions for 2416SL in the condensed phase and mixed excitons in 2416SL nanocomposites with CdTe QDs. The nature of excitonic transitions has been discussed above, and the diagram is aiming to group the transitions and visualize the complexity of studied transitions. The first group is associated with FE transitions in 2416SL H-aggregates that occur in the solutions and films. In addition to FE, at optical Frank-Condon transitions, it is possible to excite an unrelaxed electron-polaron pair: excitons with charge transfer (CTE

1 and CTE

2). Relaxed molecular-polaron pairs (CPE

1 and CPE

2) appear as intermediate states in the processes of photogeneration and radiative recombination of the CTEs. In the hybrid 2416SL-CdTe nanostructures, the unrelaxed CTE

1 state of the aggregated 2416SL and the WME of CdTe QDs form mixed exciton states. As can be seen from the diagram, the interaction of exciton states leads to the appearance of new levels above the bottom of the exciton zone for CdTe WME and the exciton zone of CTE

1. The mixed exciton transition is indicated on the diagram as CTE

1-WME

1 transition. The emission of hybrid 2416SL-CdTe nanostructures (e.g., 594 nm) strongly overlaps with the emission of 2416SL aggregates and is not included in the diagram.

Table 6 summarizes the nature and values of exciton transitions for absorption and PL in the studied systems.