Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel Production for Biomedical Applications: A Comparative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

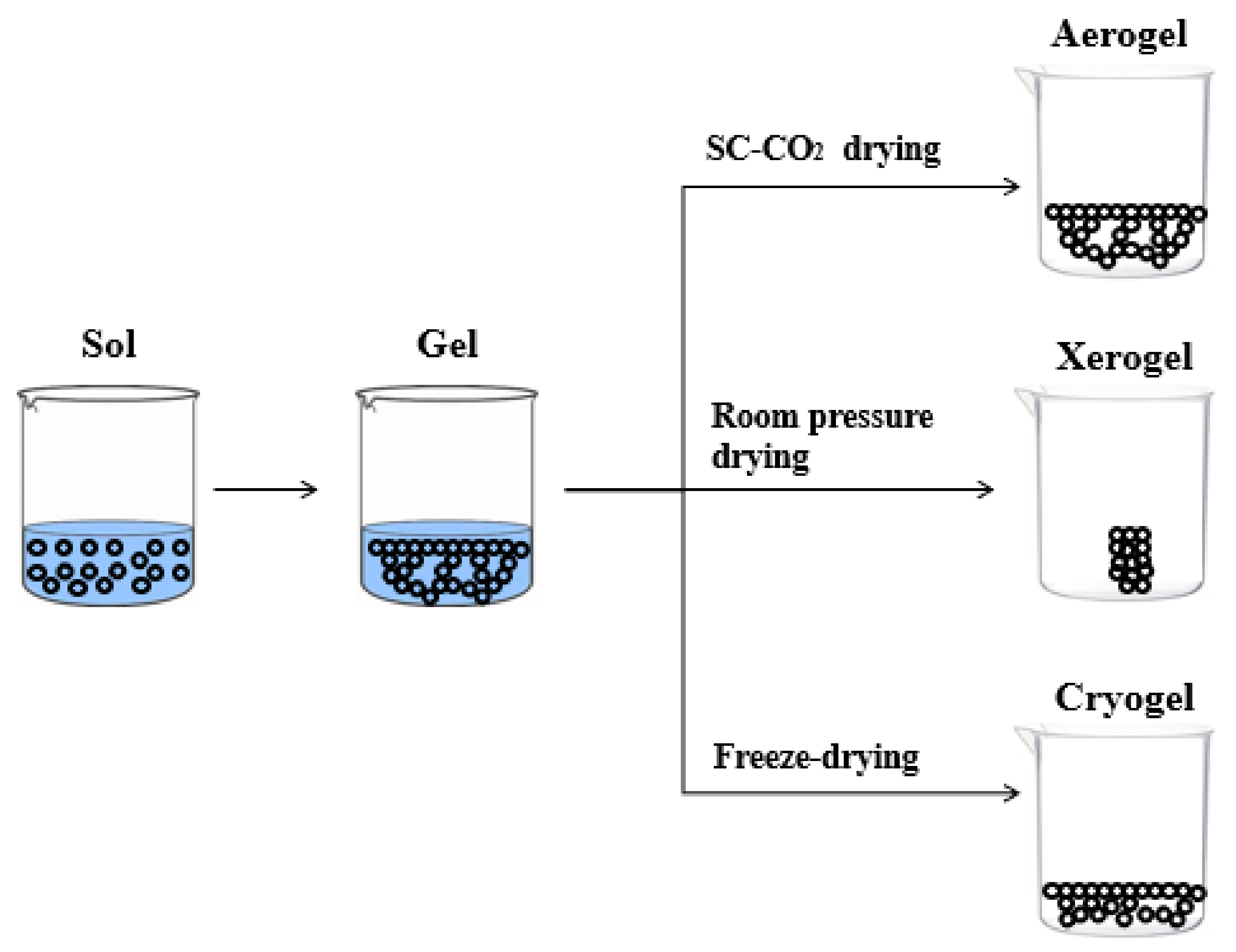

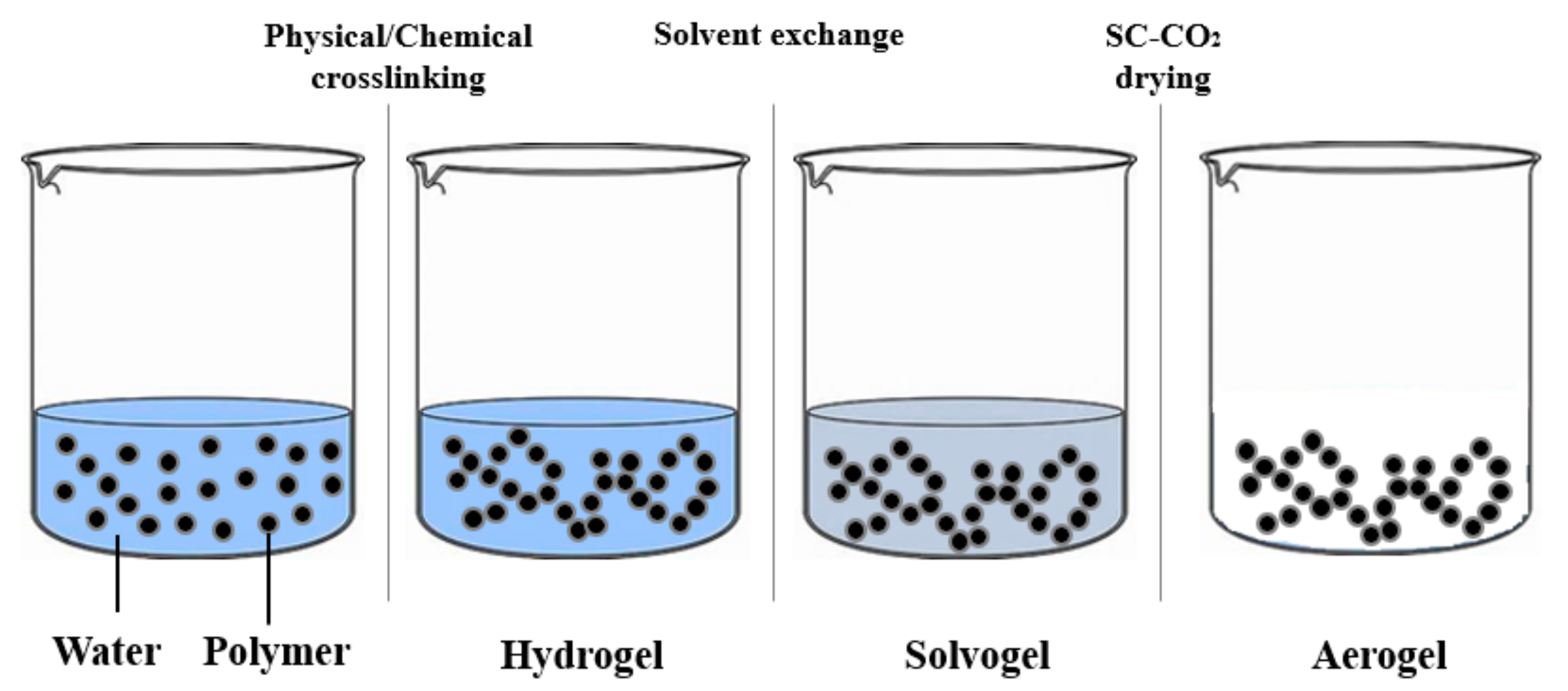

2. Classification

2.1. Inorganic Aerogels

2.2. Organic Aerogels

3. Specific Application: Chitosan, Alginate, Agarose Scaffolds for Tissue Engineering

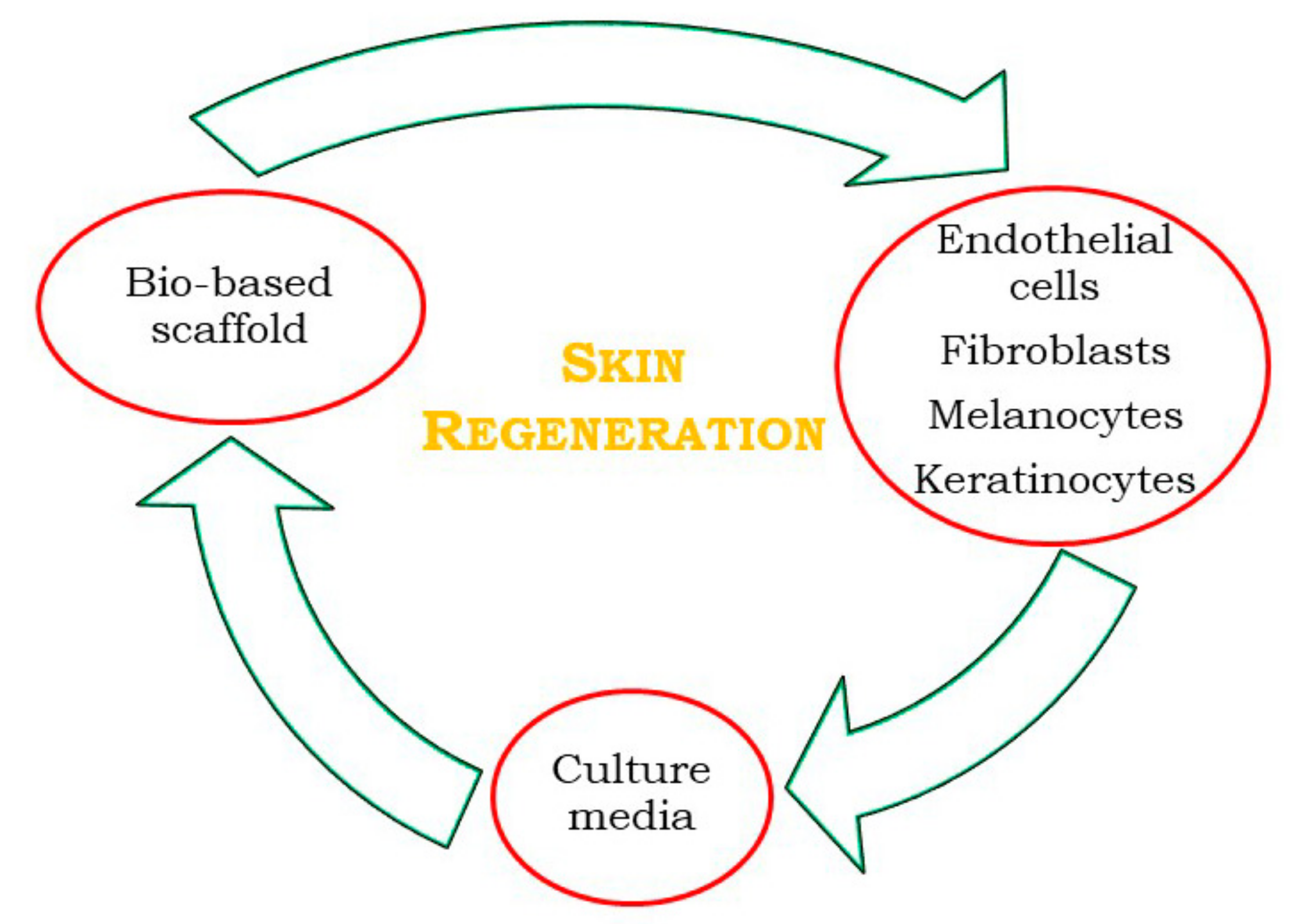

3.1. Skin Regeneration

3.1.1. Polysaccharide-Based Cryogels for Skin Regeneration

3.1.2. Polysaccharide-Based Aerogels for Skin Regeneration

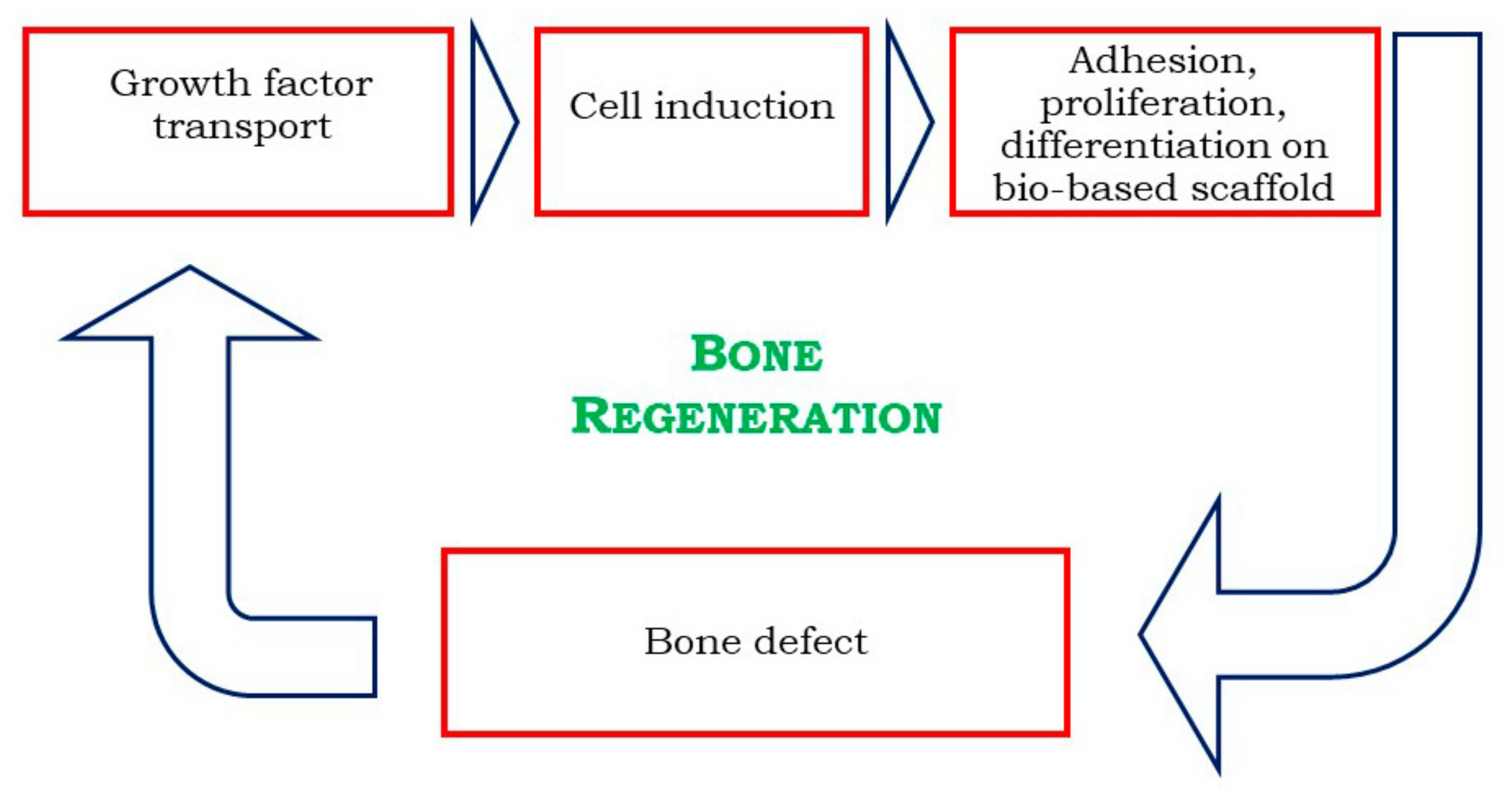

3.2. Bone Regeneration

3.2.1. Alginate-Based Cryogels for Bone Regeneration

3.2.2. Alginate-Based Aerogels for Bone Regeneration

3.2.3. Chitosan-Based Cryogels for Bone Regeneration

3.2.4. Chitosan-Based Aerogels for Bone Regeneration

3.2.5. Agarose-Based Cryogels for Bone Regeneration

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Kistler, S.S. Coherent expanded aerogels and jellies. Nature 1931, 127, 741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, C.A.; Budtova, T.; Durães, L.; Erkey, C.; del Gaudio, P.; Gurikov, P.; Koebel, M.; Liebner, F.; Neagu, M.; Smirnova, I. An opinion paper on aerogels for biomedical and environmental applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, H.; Durāes, L.; Portugal, A. An overview on silica aerogels synthesis and different mechanical reinforcing strategies. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2014, 385, 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Cunha, J.P.; Neves, F.; Lopes, M.I. On the reconstruction of Cherenkov rings from aerogel radiators. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2000, 452, 401–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, V. Development of aerogel windows. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1992, 145, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibiat, V.; Lefeuvre, O.; Woignier, T.; Pelous, J.; Phalippou, J. Acoustic properties and potential applications of silica aerogels. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1995, 186, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkateswara Rao, A.; Hegde, N.D.; Hirashima, H. Absorption and desorption of organic liquids in elastic superhydrophobic silica aerogels. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2007, 305, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-W.; Jung, S.-B.; Kang, M.-G.; Park, H.-H.; Kim, H.-C. Modification of GaAs and copper surface by the formation of SiO2 aerogel film as an interlayer dielectric. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 216, 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Kadib, A.; Bousmina, M. Chitosan bio-based organic-inorganic hybrid aerogel microspheres. Chem. Eur. J. 2012, 18, 8264–8277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-González, C.A.; Alnaief, M.; Smirnova, I. Polysaccharide-based aerogels-promising biodegradable carriers for drug delivery systems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 86, 1425–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, A.; Pascual, C.D. Bio-based polymers, supercritical fluids and tissue engineering. Process Biochem. 2015, 50, 826–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesan, K.; Budtova, T.; Ratke, L.; Gurikov, P.; Baudron, V.; Preibisch, I.; Niemeyer, P.; Smirnova, I.; Milow, B. Review on the production of polysaccharide aerogel particles. Materials 2018, 11, 2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parikka, K.; Leppänen, A.-S.; Xu, C.; Pitkänen, L.; Eronen, P.; Österberg, M.; Brumer, H.; Willför, S.; Tenkanen, M. Functional and anionic cellulose-interacting polymers by selective chemo-enzymatic carboxylation of galactose-containing polysaccharides. Biomacromolecules 2012, 13, 2418–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.-M.; Chen, G.-G.; Gong, X.-D.; Fu, G.-Q.; Niu, Y.-S.; Bian, J.; Peng, F.; Sun, R.-C. Enhanced mechanical performance of biocompatible hemicelluloses-based hydrogel via chain extension. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 33603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar, M.E.; Othman, S.I.; Allam, A.A.; Morsy, O.M. Synthesis, drying process and medical application of polysaccharide-based aerogels. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 145, 1115–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A.S. Hydrogels for biomedical applications. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012, 64, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshita, S.; Zao, S.; Malfait, W.J.; Koebel, M.M. Chemistry of chitosan aerogels: Three-dimensional pore control for tailored applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 2–26. [Google Scholar]

- Conzatti, G.; Faucon, D.; Castel, M.; Ayadi, F.; Cavalie, S.; Tourrette, A. Alginate/chitosan polyelectrolyte complexes: A comparative study of the influence of the drying step on physicochemical properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 172, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henderson, T.M.A.; Ladewig, K.; Haylock, D.N.; McLean, K.M.; O’Connor, A.J.J. Cryogels for biomedical applications. Mater. Chem. B 2013, 1, 2682–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, C.; Li, Q.; Wang, X.; Wu, P.; Ho, J.K.; Jin, R.; Zhang, L.; Shao, H.; Han, C. Silver nanoparticle loaded collagen/chitosan scaffolds promote wound healing via regulating fibroblast migration and macrophage activation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Elizalde, I.; Bernáldez-Sarabia, J.; Moreno-Ulloa, A.; Vilanova, C.; Juárez, P.; Licea-Navarro, A.; Castro-Ceseña, A.B. Scaffolds based on alginate-PEG methyl ether methacrylate-Moringa oleifera-Aloe vera for wound healing applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 206, 455–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, W.; Xu, H.; Lan, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Huang, S.; Shi, S.; Hancharou, A.; Tang, B.; Guo, R. Preparation and characterisation of a novel silk fibroin/hyaluronic acid/sodium alginate scaffold for skin repair. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 130, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, P.; Nayak, K.K. Optimization of keratin/alginate scaffold using RSM and its characterization for tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 85, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; Lu, L.; Zhang, W.; Shi, J.; Cao, Y. Reinforced low density alginate-based aerogels: Preparation, hydrophobic modification and characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 88, 1093–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardea, S.; Pisanti, P.; Reverchon, E. Generation of chitosan nanoporous structures for tissue engineering applications using a supercritical fluid assisted process. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2010, 54, 290–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñor-Ruíz, A.; Escobar-García, D.M.; Quintana, M.; Pozos-Guillén, A.; Flores, H. Synthesis and characterization of a new collagen-alginate aerogel for tissue engineering. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 2875375. [Google Scholar]

- Baldino, L.; Concilio, S.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Interpenetration of natural polymers aerogels by supercritical drying. Polymers 2016, 8, 106–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Loaded silk fibroin aerogel production by supercritical gel drying process for nanomedicine applications. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2016, 49, 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Nanostructured chitosan-gelatin hybrid aerogels produced by supercritical gel drying. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2018, 58, 1494–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardea, S.; Gugliuzza, A.; Sessa, M.; Aceto, M.C.; Drioli, E.; Reverchon, E. Supercritical gel drying: A powerful tool for tailoring symmetric porous PVDF-HFP membranes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Su, Y.; Wang, W.; Fang, Y.; Riffat, S.B.; Jiang, F. The advances of polysaccharide-based aerogels: Preparation and potential application. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 226, 115242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Scognamiglio, M.; Reverchon, E. A new tool to produce alginate-based aerogels for medical applications, by supercritical gel drying. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2019, 146, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardea, S.; Baldino, L.; Scognamiglio, M.; Reverchon, E. 3D PLLA/Ibuprofen composite scaffolds obtained by a supercritical fluids assisted process. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 989–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Marco, I.; Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Supercritical gel drying for the production of starch aerogels for delivery systems. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 43, 307–312. [Google Scholar]

- Pajonk, G.M.; Manzalji, T. Synthesis of acrylonitrile from propylene and nitric oxide mixtures on PbO2-ZrO2 aerogel catalysts. Catal. Lett. 1993, 21, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurav, J.L.; Jung, I.-K.; Park, H.-H.; Kang, E.S.; Nadargi, D.Y. Silica aerogel: Synthesis and applications. J. Nanomater. 2010, 2010, 409310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, G.; Shen, J.; Wang, W.; Zou, L.; Lian, Y.; Zhang, Z. Silica-titania composite aerogel photocatalysts by chemical liquid deposition of titania onto nanoporous silica scaffolds. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 5400–5409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Neto, E.P.; Worsley, M.A.; Rodrigues-Filho, U.P. Towards thermally stable aerogel photocatalysts: TiCl4-based sol-gel routes for the design of nanostructured silica-titania aerogel with high photocatalytic activity and outstanding thermal stability. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 103425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Xie, J.; Lϋ, X.; Jiang, D. Synthesis and characterization of superhydrophobic silica and silica/titania aerogels by sol-gel method at ambient pressure. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2009, 342, 97–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Liang, W.; Rhodes, S.; Fang, J. Synthesis of silica-titania composite aerogel beads for the removal of Rhodamine B in water. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 72437–72443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, L.; Ji, Z.-H.; Han, W.-J.; Hu, J.-D.; Zhao, T. Synthesis and characterization of silica/carbon composite aerogels. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2010, 93, 1156–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Q.; Wang, T.; Liang, Y. Facile one-step precursor-to-aerogel synthesis of silica-doped alumina aerogels with high specific surface area at elevated temperatures. J. Porous Mater. 2017, 24, 889–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Zhou, Q.; Qiu, G.; Peng, B.; Guo, M.; Zhang, M. Synthesis of an alumina enriched Al2O3-SiO2 aerogel: Reinforcement and ambient pressure drying. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2017, 471, 160–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shao, G.; Cui, S.; Wang, L.; Shen, X. Synthesis of a novel Al2O3-SiO2 composite aerogel with high specific surface area at elevated temperatures using inexpensive inorganic salt of aluminum. Ceram. Int. 2016, 42, 874–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorcheh, A.S.; Abbasi, M.H. Silica aerogel; synthesis, properties and characterization. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2008, 199, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blaszczyński, T.; Ślosarczyk, A.; Morawski, M. Synthesis of silica aerogel by supercritical drying method. Procedia Eng. 2013, 57, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, L.K.; Na, B.K.; Ko, E.I. Synthesis and characterization of titania aerogels. Chem. Mater. 1992, 4, 1329–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocon, L.; Despetis, F.; Phalippou, J. Ultralow density silica aerogels by alcohol supercritical drying. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1998, 225, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaoui, R.; Elghniji, K.; Mosbah, M.B.; Elaloui, E.; Moussaoui, Y. Sol-gel synthesis of highly TiO2 aerogel photocatalyst via high temperature supercritical drying. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2017, 21, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizushima, Y.; Hori, M. Properties of alumina aerogels prepared under different conditions. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1994, 167, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Z.; Wang, J.; Wu, A.; Shen, J.; Zhou, B. High strength SiO2 aerogel insulation. J. Non Cryst. Solids 1998, 225, 101–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinoshita, M.; Shimoyama, Y. Dynamic phase behavior during sol-gel reaction in supercritical carbon dioxide for morphological design of nanostructured titania. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2016, 116, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoyama, Y.; Ogata, Y.; Ishibashi, R.; Iwai, Y. Drying processes for preparation of titania aerogel using supercritical carbon dioxide. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2010, 88, 1427–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, L.; Naddeo, F.; Cardea, S.; Naddeo, A.; Reverchon, E. FEM modeling of the reinforcement mechanism of hydroxyapatite in PLLA scaffolds produced by supercritical drying, for tissue engineering applications. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 51, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, J.; Ojima, T.; Shioya, M.; Hatori, H.; Yamada, Y. Organic and carbon aerogels derived from poly(vinyl chloride). Carbon 2003, 41, 285–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshrah, M.; Tran, M.-P.; Gong, P.; Naguib, H.E.; Park, C.B. Development of high-porosity resorcinol formaldehyde aerogels with enhanced mechanical properties through improved particle necking under CO2 supercritical conditions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 485, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štengl, V.; Bakardjieva, S.; Šubrt, J.; Szatmary, L. Titania aerogel prepared by low temperature supercritical drying. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2006, 91, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abecassis-Wolfovich, M.; Rotter, H.; Landau, M.V.; Korin, E.; Erenburg, A.I.; Mogilyansky, D.; Gartstein, E. Texture and nanostructure of chromia aerogels prepared by urea-assisted homogeneous precipitation and low-temperature supercritical drying. J. Non Cryst. Solids 2003, 318, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Fu, R.; Yu, Z. Organic and carbon aerogels from NaOH-catalyzed polycondensation of resorcinol-furfural and supercritical drying in ethanol. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2005, 96, 1429–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Xu, M.; Wang, L.; Li, J. Preparation and characterization of organic aerogels by the lignin-resorcinol-formaldehyde copolymer. Bio. Resour. 2011, 6, 1262–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, L.; Zhang, H. Controlled freezing and freeze drying: A versatile route for porous and micro-/nano-structured materials. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2010, 86, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, A.A.; Salama, A.H. Norfloxacin-loaded collagen/chitosan scaffolds for skin reconstruction: Preparation, evaluation and in-vivo wound healing assessment. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 83, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, P.X. Scaffold for tissue fabrication. Mater. Today 2004, 7, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverchon, E.; Cardea, S. Supercritical fluids in 3-D tissue engineering. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2012, 69, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baroni, A.; Buommino, E.; de Gregorio, V.; Ruocco, E.; Ruocco, V.; Wolf, R. Structure and function of the epidermis related to barrier properties. Clin. Dermatol. 2012, 30, 257–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varaprasad, K.; Jayaramudu, T.; Kanikireddy, V.; Toro, C.; Sadiku, E.R. Alginate-based composite materials for wound dressing application: A mini review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 236, 116025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Shi, G.; Bei, J.; Whang, S.; Cao, Y.; Shang, Q.; Yang, G.; Wang, W. Fabrication and surface modification of macroporous poly(L-lactic acid) and poly(L-lactic-co-glycolic acid) (70/30) cell scaffolds for human skin fibroblast cell culture. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2002, 62, 438–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, A.S.; Zimoch, J.; Biedermann, T. Skin tissue engineering: Application of adipose-derived stem cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2017, 2017, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, T.; Tanaka, M.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Hamblin, M.R. Chitosan preparations for wounds and burns: Antimicrobial and wound-healing effects. Expert Rev. Anti. Infect. Ther. 2011, 9, 857–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, H.; Mori, T.; Fujinaga, T. Topical formulations and wound healing applications of chitosan. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2001, 52, 105–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrulea, V.; Ostafe, V.; Borchard, G.; Jordan, O. Chitosan as starting material for wound healing applications. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. B 2015, 97, 417–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.C.; Marques, A.P.; Silva, S.S.; Oliveira, J.M.; Mano, J.F.; Castro, A.G.; Reis, R.L. In vitro evaluation of human polymorphonuclear neutrophils in direct contact with chitosan-based membranes. J. Biotechnol. 2007, 132, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjum, S.; Arora, A.; Alam, M.S.; Gupta, B. Development of antimicrobial and scar preventive chitosan hydrogel wound dressings. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 508, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, T.; Jiang, J.; Zhao, J.; Chen, S.; Yan, X. Regulating preparation of functional alginate-chitosan three dimensional scaffold for skin tissue regeneration. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 8891–8903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarrintaj, P.; Manouchehri, S.; Ahmadi, Z.; Saeb, M.R.; Urbanska, A.M.; Kaplan, D.L.; Mozafari, M. Agarose-based biomaterials for tissue engineering. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 187, 66–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nayak, K.K.; Gupta, P. In-vitro biocompatibility study of keratin/agar scaffold for tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 81, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazimierczak, P.; Benko, A.; Nocun, M.; Przekora, A. Novel chitosan/agarose/hydroxyapatite nanocomposite scaffold for bone tissue engineering applications: Comprehensive evaluation of biocompatibility and osteoinductivity with the use of osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2019, 14, 6615–6630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramana Ramya, J.; Arul, K.T.; Asokan, K.; Ilangovan, R. Enhanced microporous structure of gamma-irradiated agarose-gelatin-HAp flexible films for IR window and microelectronic applications. Mater. Today Commun. 2020, 24, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; Reverchon, E. Natural aerogels production by supercritical gel drying. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2015, 43, 739–744. [Google Scholar]

- Franco, P.; Pessolano, E.; Belvedere, R.; Petrella, A.; De Marco, I. Supercritical impregnation of mesoglycan into calcium alginate aerogel for wound healing. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2020, 157, 104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valchuk, N.A.; Brovko, O.S.; Palamarchuk, I.A.; Boitsova, T.A.; Bogolitsyn, K.G.; Ivakhnov, A.D.; Chukhchin, D.G.; Bogdanovich, N.I. Preparation of aerogel materials based on alginate-chitosan interpolymer complex using supercritical fluid. Russ. J. Phys. Chem. B 2019, 13, 1121–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Jin, S.; Fu, C.; Cui, S.; Zhang, T.; Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Shen, S.G.F.; Jiang, N.; Liu, Y. Macrophage-derived small extracellular vesicles promote biomimetic mineralized collagen-mediated endogenous bone regeneration. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2020, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revilla-Leόn, M.; Sadeghpour, M.; Özcan, M. An update on applications of 3D printing technologies used for processing polymers used in implant dentistry. Odontology 2020, 108, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Feng, Y.; He, M.; Zhao, W.; Qiu, L.; Zhao, C. A hierarchical janus nanofibrous membrane combining direct osteogenesis and osteoimmunomodulatory functions for advanced bon regeneration. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 31, 2008906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliramaji, S.; Zamanian, A.; Mozafari, M. Super-paramagnetic responsive silk fibroin/chitosan/magnetite scaffolds with tunable pore structures for bone tissue engineering applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, M.; Kang, Y. Engineering porous β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP) scaffolds with multiple channels to promote cell migration, proliferation, and angiogenesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 9223–9232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, T.-M.; Fratila-Apachitei, L.E.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Peppas, N.A. Bone tissue engineering via growth factor delivery: From scaffolds to complex matrices. Regen. Biomater. 2018, 5, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, I.; Ghayor, C.; Weber, F. The use of adipose tissue-derived progenitors in bone tissue engineering—A review. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2016, 43, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Pei, Y.; Tang, K.; He, X.; Huang, J.; Wang, F. Mechanical and drug release properties of alginate beads reinforced with cellulose. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2017, 134, 44495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens-Gámez, M.; Salesa, B.; Serrano-Aroca, Á. Physical and biological properties of alginate/carbon nanofibers hydrogel films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 151, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Shi, J.; Xia, Y. Effect of SiO2, PVA and glycerol concentrations on chemical and mechanical properties of alginate-based films. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. B 2018, 107, 2686–2694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alboofetileh, M.; Rezaei, M.; Hosseini, H.; Abdollahi, M. Effect of montmorillonite clay and biopolymer concentration on the physical and mechanical properties of alginate nanocomposite films. J. Food Eng. 2013, 117, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohamy, K.M.; Mabrouk, M.; Soliman, I.E.; Beherei, H.H.; Aboelnasr, M.A. Novel alginate/hydroxyethylcellulose/hydroxyapatite composite scaffold for bone regeneration: In vitro cell viability and proliferation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 112, 448–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purohit, S.D.; Bhaskar, R.; Singh, H.; Yadav, I.; Gupta, M.K.; Mishra, N.C. Development of a nanocomposite scaffold of gelatine-alginate-graphene oxide for bone tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 133, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afshar, H.A.; Ghaee, A. Preparation of aminated chitosan/alginate scaffold containing hallosyte nanotubes with improved cell attachment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 151, 1120–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, M.; Barros, A.A.; Quraishi, S.; Gurikov, P.; Raman, S.P.; Smirnova, I.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Reis, R.L. Preparation of macroporous alginate-based aerogels for biomedical applications. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2015, 106, 152–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzzarelli, R.; Baldassarre, V.; Conti, F.; Ferrara, P.; Biagini, G.; Gazzanelli, G.; Vasi, V. Biological activity of chitosan: Ultrastructural study. Biomaterials 1988, 9, 247–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thein-Han, W.W.; Kitiyanant, Y.; Misra, R.D.K. Chitosan as scaffold matrix for tissue engineering. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 1062–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiourvas, D.; Sapalidis, A.; Papadopoulos, T. Hydroxyapatite/chitosan-based porous three-dimensional scaffolds with complex geometries. Mater. Today Commun. 2016, 7, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, I.R.; Fradique, R.; Vallejo, M.C.S.; Correia, T.R.; Miguel, S.P.; Correia, I.J. Production and characterization of chitosan/gelatin/β-TCP scaffolds for improved bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2015, 55, 592–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakker, S.P.; Rokhade, A.P.; Abbigerimath, S.S. Inter-polymer complex microspheres of chitosan and cellulose acetate phthalate for oral delivery of 5-fluorouracil. Polym. Bull. 2014, 71, 2113–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S.D.; Abueva, C.; Kim, B.; Lee, B.T. Chitosan-hyaluronic acid polyelectrolyte complex scaffold crosslinked with genipin for immobilization and controlled release of BMP-2. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 115, 160–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, U.; Rijal, N.P.; Khanal, S.; Pai, D.; Sankar, J.; Bhattarai, N. Magnesium incorporated chitosan based scaffolds for tissue engineering applications. Bioact. Mater. 2016, 1, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, Q.; Xu, S.; Zheng, Q.; Cao, X. Preparation and properties of 3D printed alginate-chitosan polyion complex hydrogels for tissue engineering. Polymers 2018, 10, 664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Z.; Shi, C.; Chen, M.; Gu, Y.; Liu, Y. Preparation and properties of dopamine-modified alginate/chitosan-hydroxyapatite scaffolds with gradient structure for bone tissue engineering. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2019, 107, 1615–1627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolanthai, E.; Sindu, P.A.; Khajuria, D.K.; Veerla, S.C.; Kuppuswamy, D.; Catalani, L.H.; Mahapatra, D.R. Graphene-oxide-a tool for the preparation of chemically crosslinking free alginate-chitosan-collagen scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 12441–12452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.-M.; Lin, Y.-C.; Chen, C.-Y.; Hsieh, Y.-Y.; Liaw, C.-K.; Huang, S.-W.; Tsuang, Y.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Lin, F.-H. Thermosensitive chitosan–gelatin–glycerol phosphate hydrogels as collagenase carrier for tendon–bone healing in a rabbit model. Polymers 2020, 12, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, P.; Öztϋrk Er, E.; Bakirdere, S.; ϋlgen, K.; Özbek, B. Application of supercritical gel drying method on fabrication of mechanically improved and biologically safe three-component scaffold composed of graphene oxide/chitosan/hydroxyapatite and characterization studies. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 5201–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldino, L.; Cardea, S.; De Marco, I.; Reverchon, E. Chitosan scaffolds formation by a supercritical freeze extraction process. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2014, 90, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, E.; Sendemir-Urkmez, A.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. Supercritical CO2 processing of a chitosan-based scaffold: Can implementation of osteoblastic cells be enhanced? J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 75, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Iglesias, C.; Barros, J.; Ardao, I.; Gurikov, P.; Monteiro, F.J.; Smirnova, I.; Alvarez-Lorenzo, C.; García-González, C.A. Jet cutting technique for the production of chitosan aerogel microparticles loaded with vancomycin. Polymers 2020, 12, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, P.J.; Ramos, J.C.; Martins, J.B.; Diogenes, A.; Figueiredo, M.H.; Ferreira, P.; Viegas, C.; Santos, J.M. Histologic evaluation of regenerative endodontic procedures with the use of chitosan scaffolds in immature dog teeth with apical periodontitis. J. Endod. 2017, 43, 1279–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Salcedo, S.; Nieto, A.; Vallet-Regí, M. Hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate/agarose macroporous scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Chem. Eng. J. 2008, 137, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, S.; Hashimoto, I.; Kawakami, K. Synthesis of an agarose-gelatin conjugate for use as a tissue engineering scaffold. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2007, 103, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Lai, H.; Lyu, Z.; Jiang, Y.; Xie, K.; Wang, X.; Wu, Q.; Yang, L.; Jin, Z.; Ma, Y.; et al. Hydrophilic hierarchical nitrogen-carbon nanocages for ultrahigh supercapacitive performance. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3541–3545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Zhang, X.; Machuki, J.O.; Dai, C.; Li, Y.; Guo, K.; Gao, F. Three-dimensionally N-doped graphene-hydroxyapatite/agarose as osteoinductive scaffold for enhancing bone regeneration. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 2, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivashankari, P.R.; Prabaharan, M. Three-dimensional porous scaffolds based on agarose/chitosan/graphene oxide composite for tissue engineering. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Materials | Process | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| You et al. [20] | NAg particles/CLG/CS | Freeze-drying | Bactericidal properties; Anti-inflammatory properties | Non-uniform morphology can damage fibroblast migration |

| Rubio-Elizalde et al. [21] | ALG/PEG–MA | Freeze-drying | Delayed degradation kinetics of ALG; Good antioxidant activity; Good antimicrobial activity; Good cell viability | Open pores on the surface can cause device contamination |

| Mahmoud et al. [62] | Norfloxacin/ CLG/CS | Freeze-drying | Good bio stability; Rapid release of norfloxacin | Polydisperse pores distribution |

| Anjum et al. [73] | CS/PEG/PVP/TC | Freeze-drying | No-scar formation | Burst effect during drug release |

| Zhu et al. [74] | Flu/ALG/CS | Freeze-drying + Amidation reaction | Good anti-inflammatory properties and good histocompatibility | Time-consuming process |

| Ramana Ramya et al. [78] | AGR/GLT/HAp | Freeze-drying + Gamma irradiation | Enhanced hemocompatibility; Enhanced antimicrobial activity and cell viability | Fast dissolution in aqueous medium |

| Franco et al. [80] | CAALG/MSG | SC-CO2 drying + SC-CO2 impregnation | Presence of a nanoporous structure; Structure suitable for cell attachment | Energy-consuming process |

| Valchuk et al. [81] | CS/ALG/ Levomycetin | SC-CO2 drying | Nanoporous structure | Burst effect during levomycetin release |

| Authors | Materials | Process | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Takeshita et al. [17] | CS | Air-drying; Freeze-drying; SC-CO2 drying | Presence of a suitable nanostructure during SC-CO2 drying | Structural degradation during freeze-drying and air-drying; Smooth pores surface for freeze-drying and SC-CO2 drying |

| Conzatti et al. [18] | CS/ALG | Air-drying; Freeze-drying; SC-CO2 drying | Mesoporosity was obtained by freeze-drying and SC-CO2 drying | Not presence of porosity after air-drying |

| Gupta and Nayak [23] | KRT/ALG | Freeze-drying | High level of porosity | Time-consuming process; Polydisperse macropores size distribution |

| Baldino et al. [27] | ALG/GLT | SC-CO2 drying | Possible modulation of morphology and mechanical properties of polymeric blends; Presence of nanopores and homogenous structure; Good polymer dispersion | Long time process to completely remove GTA traces |

| Baldino et al. [54] | CS | SC-CO2 drying | Removal of GTA during the process; Presence of nanoporous structure; Good definition of cells three-dimensional scaffolds orientation | Absence of microporosity |

| Kazimierczak et al. [77] | CS/AGR/HAp | Gas foaming + Freeze-drying | Good value of porosity | Presence of closed pores; Complex process |

| Baldino et al. [79] | CS/GLT | SC-CO2 drying | Possibility to obtain different levels of microporosity and nanoporosity changing polymeric blend compositions; Good mechanical properties | Possible phenomena of separation between the two biopolymers increasing the relative concentrations |

| Tohamy et al. [93] | SALG/Hydroxyethylcellulose/HAp | Freeze-drying + Cross-linking with Ca2+ | Improved good mechanical properties | Disomogenous macroporosity and absence of nanoporous structure for cell attachment |

| Purohit et al. [94] | GO/GLT/ALG | Freeze-drying | Suitable swelling profile | Morphology mainly represented by closed pores |

| Afshar and Ghaee [95] | CS/ALG/HNT | Freeze-drying + Amination reaction | Homogenous porous structure; Good biochemical characteristics | Complex and time-consuming process |

| Martins et al. [96] | CAALG/STR | SC-CO2 drying using three different depressurization rates | Good biocompatibility; Good bioactivity | Not presence of nanoporous structure |

| Tsiourvas et al. [99] | Nano-HAp/CS | Freeze-drying | Open interconnected highly porous structure; Improved mechanical properties of CS | Disomogenous macroporosity; HA microparticles were not homogenously dispersed |

| Serra et al. [100] | CS/GLT/β-TCP | Ionic cross-linking + Freeze-drying | Improved mechanical properties of CS after the addition of GLT and β-TCP; Good level of biomineralization | Drastic decrease in porosity after TCP addition |

| Nath et al. [102] | BMP-2/CS/HA/Genipin | Freeze-drying | Cross-linking of CS-HA improved the PEC stability in aqueous solution | Burst effect was detected for all samples |

| Adhikari et al. [103] | CS/CMC/MgG | Freeze-drying | MgG decreased water adsorption of CS scaffolds; Presence of macroporosity and smaller inner pores | Time-consuming process; Burst effect during MgG release |

| Liu et al. [104] | ALG/CS | Freeze-drying | Good bioactivity of the scaffolds | Samples collapse after processing |

| Shi et al. [105] | ALG–DA/QCS templated HAp | Iterative layering freeze-drying + Crosslinking by Ca2+ | Presence of a layered microstructure | Complex process; Uncontrolled degradation profile; Burst effect during levofloxacin release |

| Kolanthai et al. [106] | SALG/CS/CLG | Freeze-drying | Controlled swelling profile; Improvement of mechanical properties; Good support for cells growth and osteogenic differentiation | The use of a chemical cross-linker resulted in a loss of interconnectivity and in a loss of nanofibrous structure |

| Yilmaz et al. [108] | CS/GO/HAp | SC-CO2 drying | Improved tensile strength of CS scaffolds | Possible residues of GTA; Limitation in GO wt.% used because it can be cytotoxic for living cells; Not presence of nanopores |

| Baldino et al. [109] | CS | SFEP | Possible modulation of morphology; Uniform structure; High interconnectivity; Presence of micropores and nanopores | Time-consuming process |

| Ozdemir et al. [110] | CS | Freeze-drying; SC-CO2 drying | Smaller and more uniform structure after SC-CO2 drying | Not uniform structure during freeze-drying |

| Luo et al. [116] | NG/HAp/AGR | Hydrothermal + Cross-linking + Freeze-drying | Good mechanical properties | Large pores with irregular shape |

| Sivashankari and Prabaharan [117] | AGR/CS | Freeze-drying | Good swelling properties; Good mechanical properties; Good bioactivity | The effect of GO on the porosity did not show a precise trend |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Guastaferro, M.; Reverchon, E.; Baldino, L. Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel Production for Biomedical Applications: A Comparative Review. Materials 2021, 14, 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071631

Guastaferro M, Reverchon E, Baldino L. Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel Production for Biomedical Applications: A Comparative Review. Materials. 2021; 14(7):1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071631

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuastaferro, Mariangela, Ernesto Reverchon, and Lucia Baldino. 2021. "Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel Production for Biomedical Applications: A Comparative Review" Materials 14, no. 7: 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071631

APA StyleGuastaferro, M., Reverchon, E., & Baldino, L. (2021). Polysaccharide-Based Aerogel Production for Biomedical Applications: A Comparative Review. Materials, 14(7), 1631. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14071631