Carbon Adsorbents from Spent Coffee for Removal of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange from Water

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

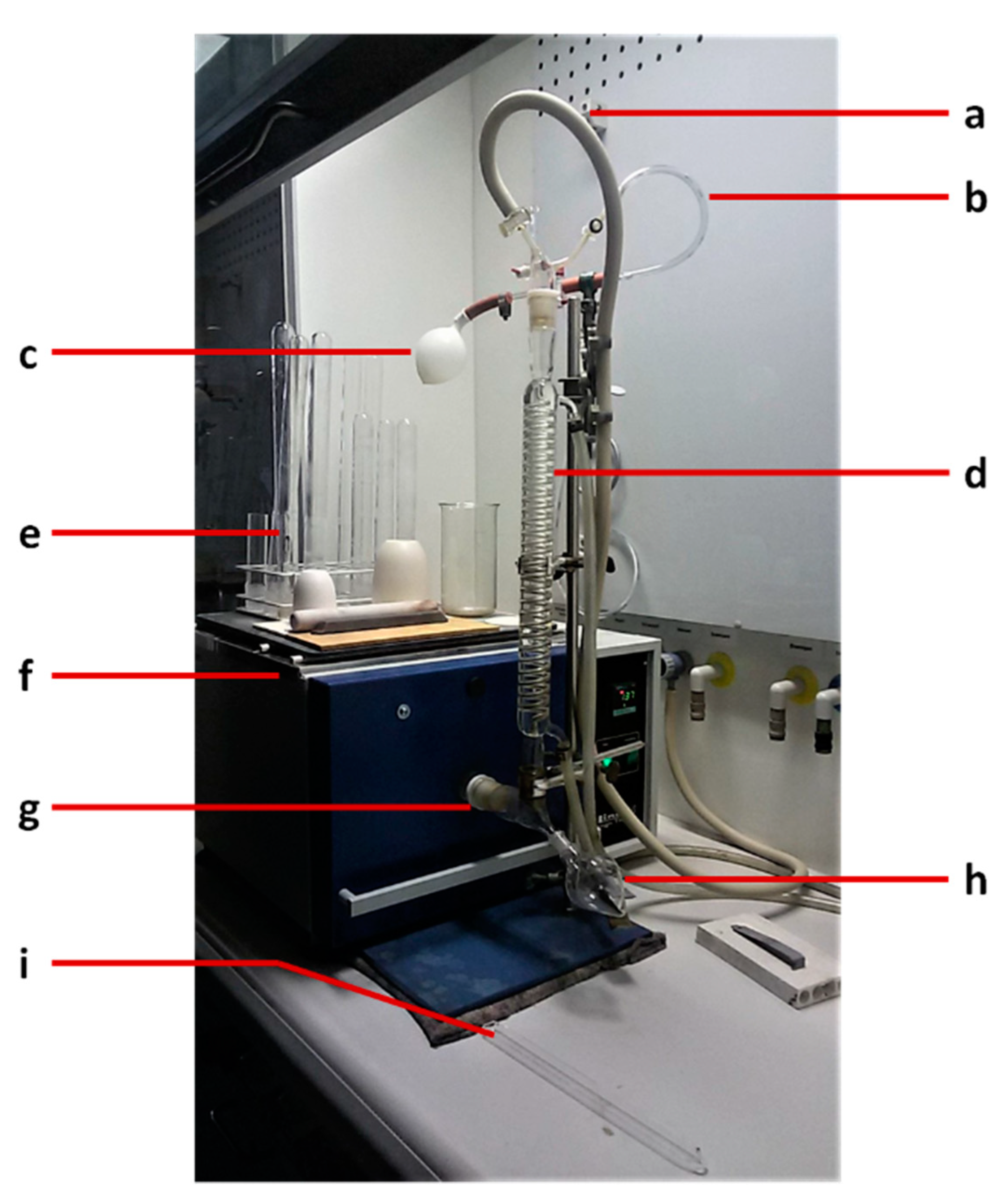

2.2. Methods

2.3. Sample Preparation

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

3. Results

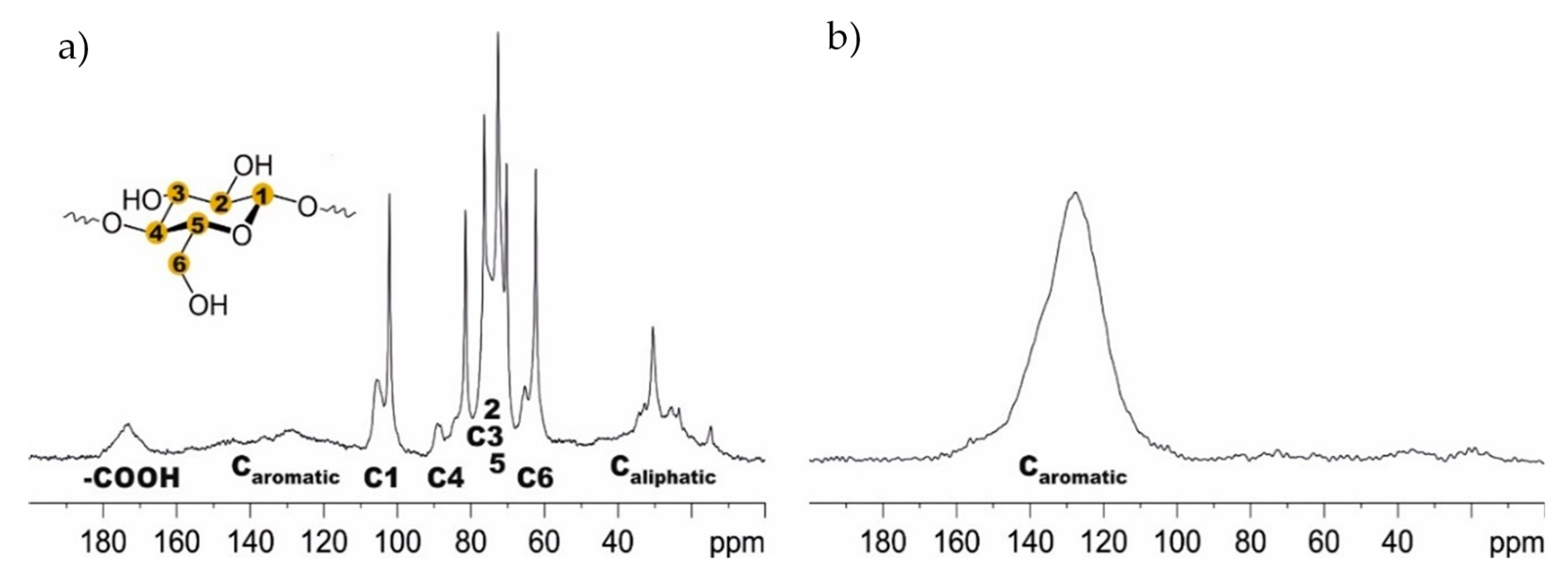

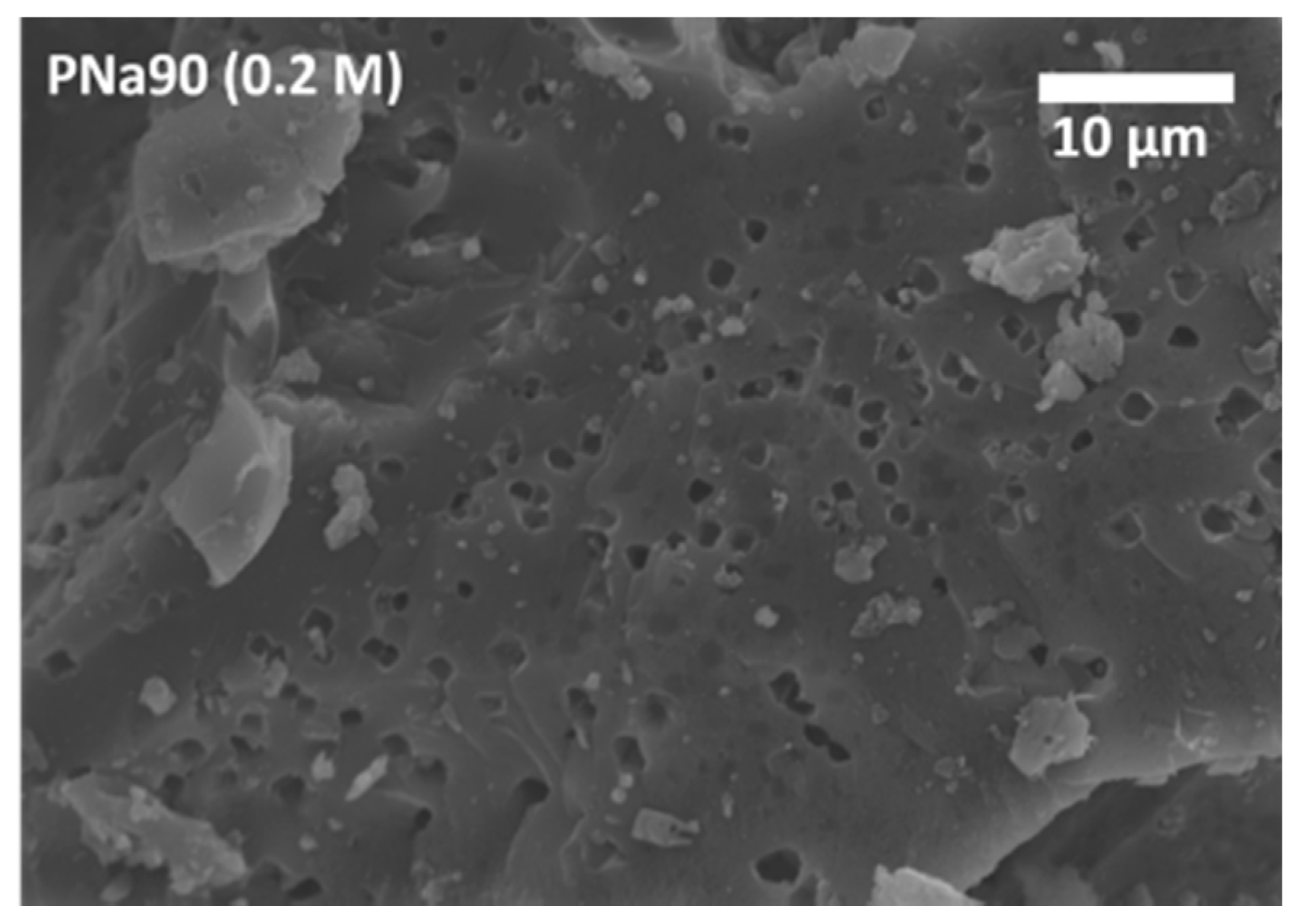

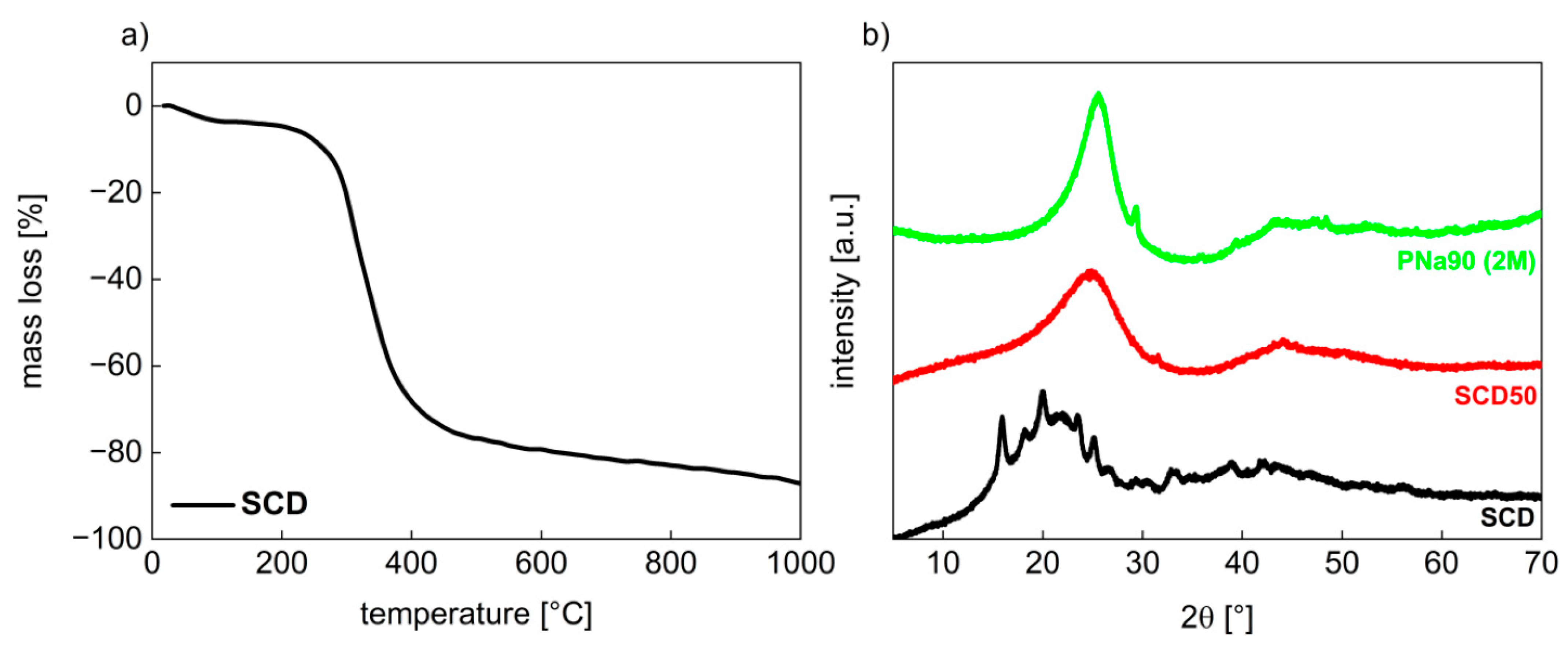

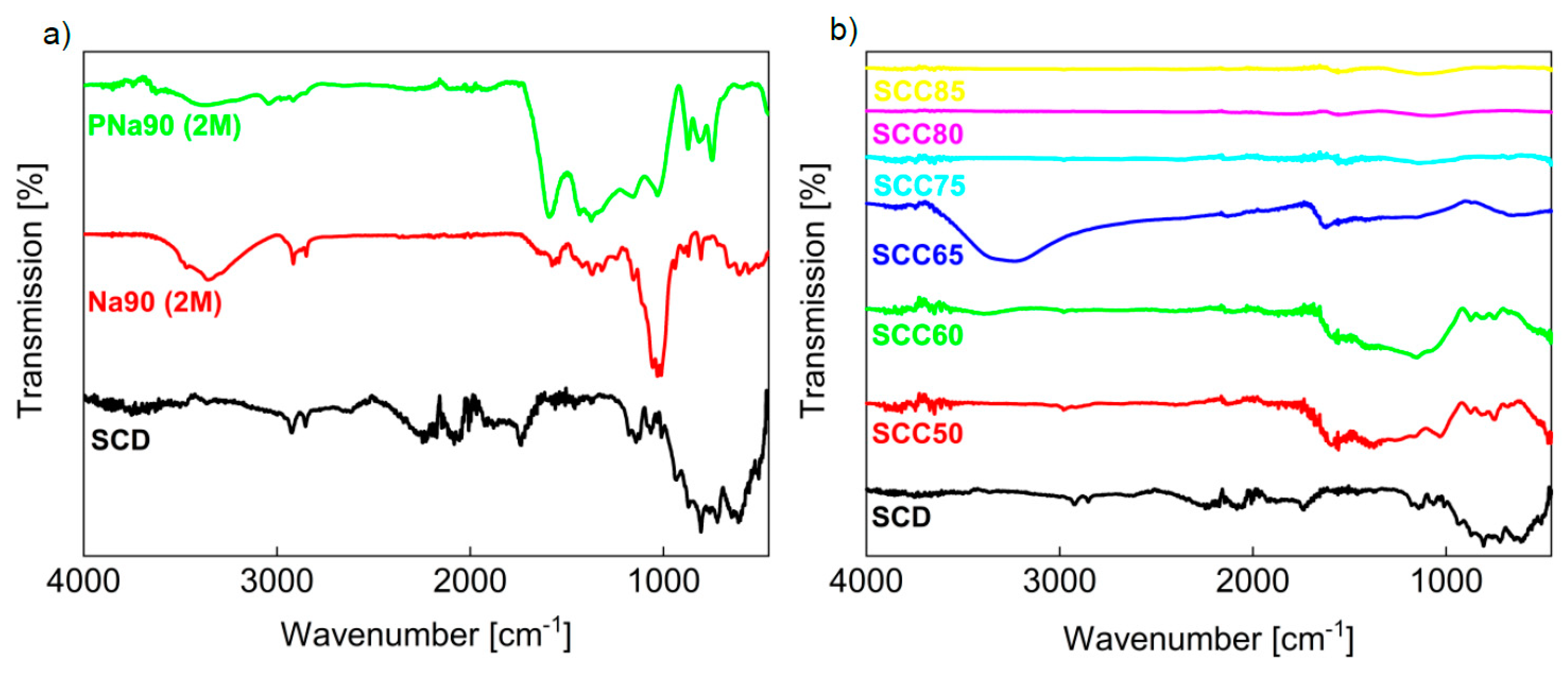

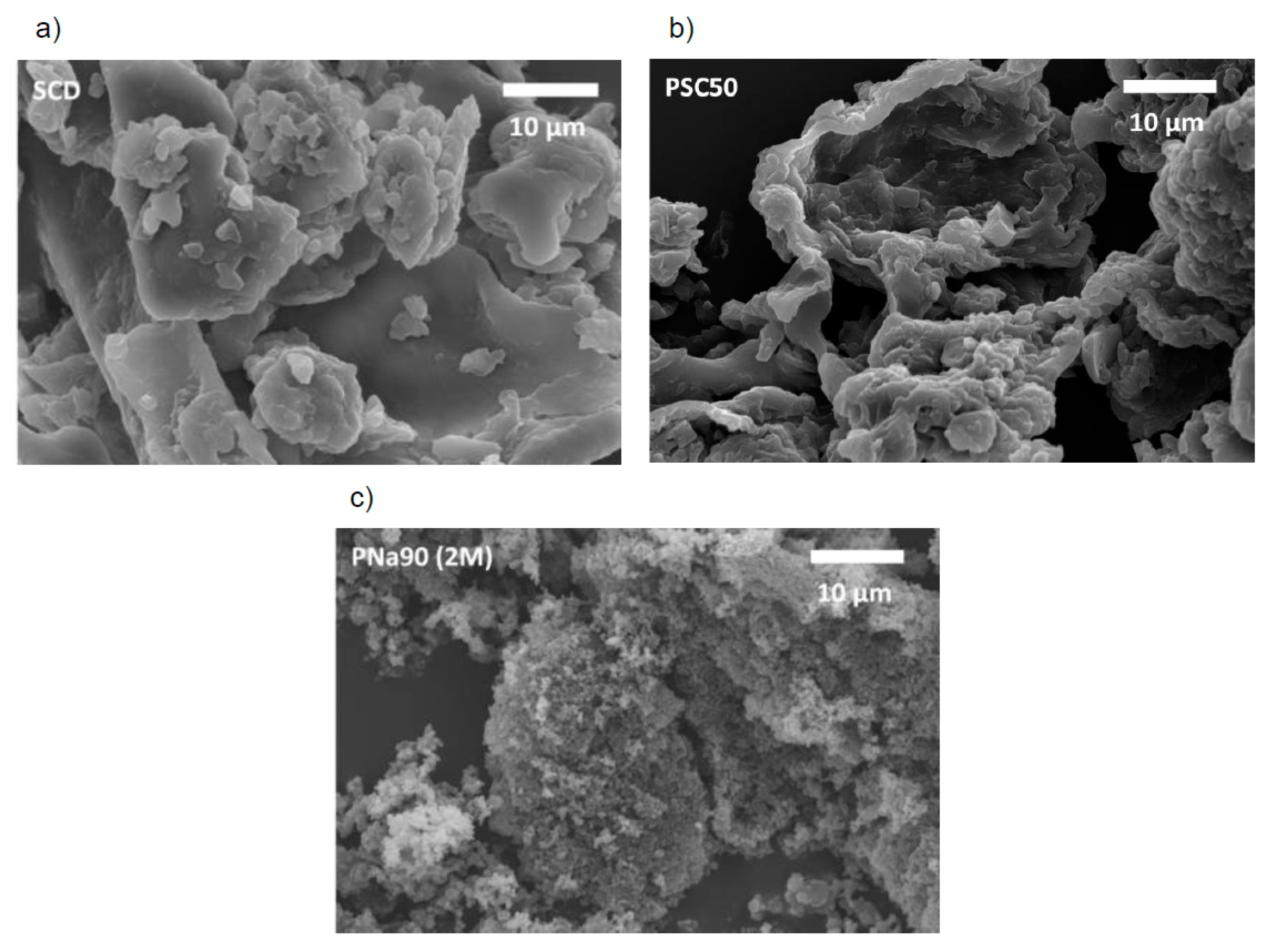

3.1. Activated Carbons from Chemically Pretreated Spent Coffee

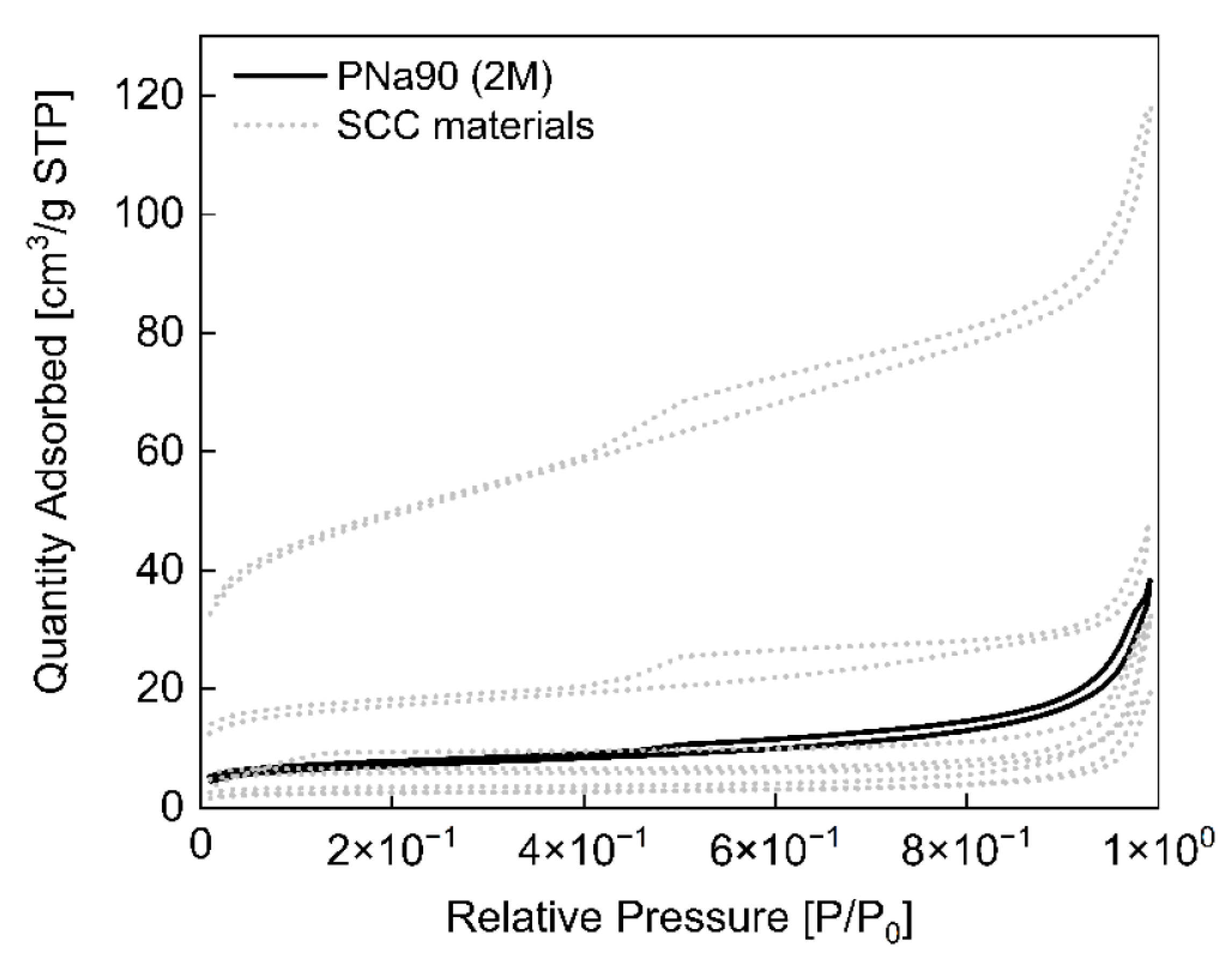

3.2. Activated Carbons from Spent Coffee/Calcium Carbonate Mixtures

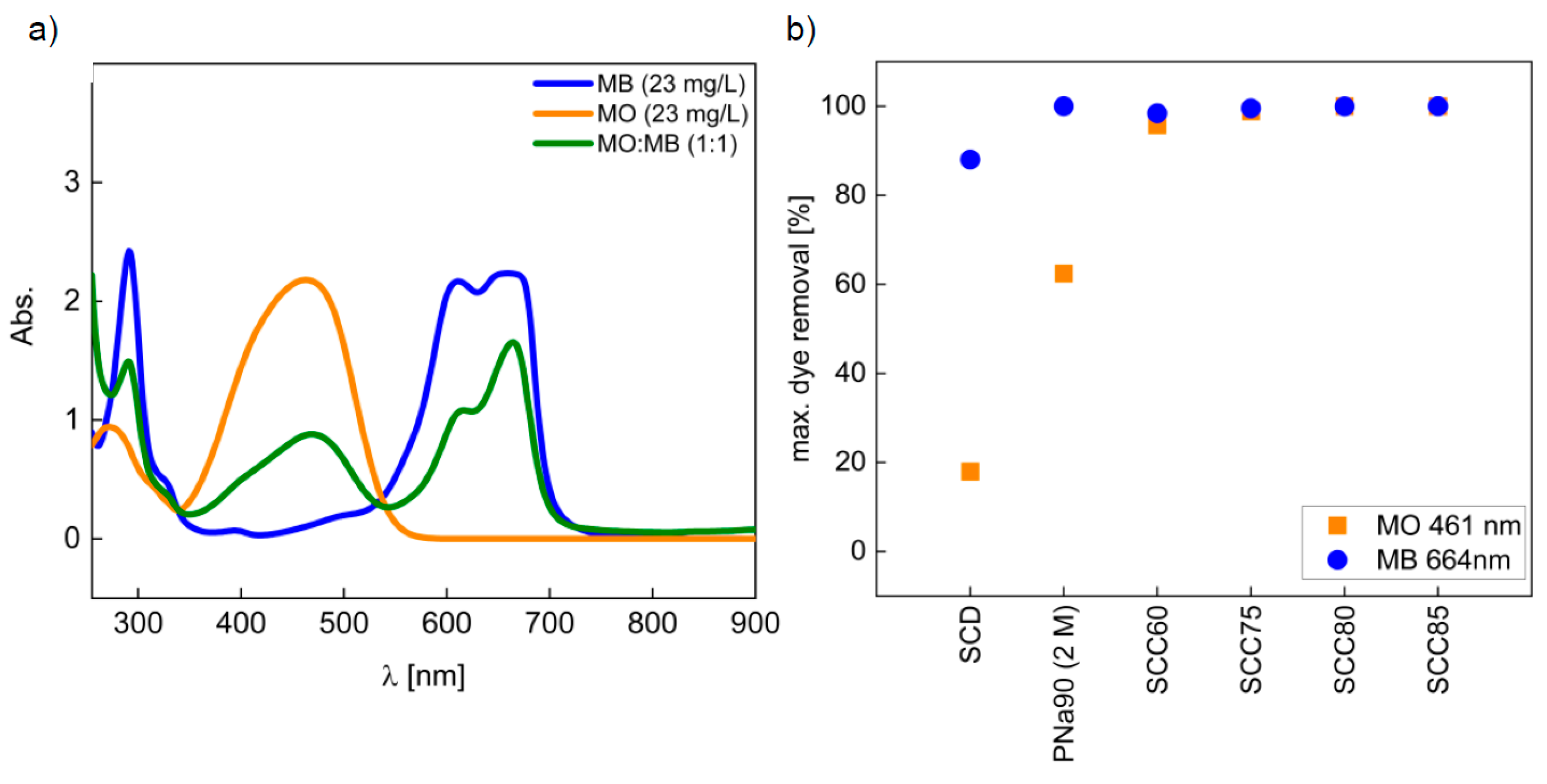

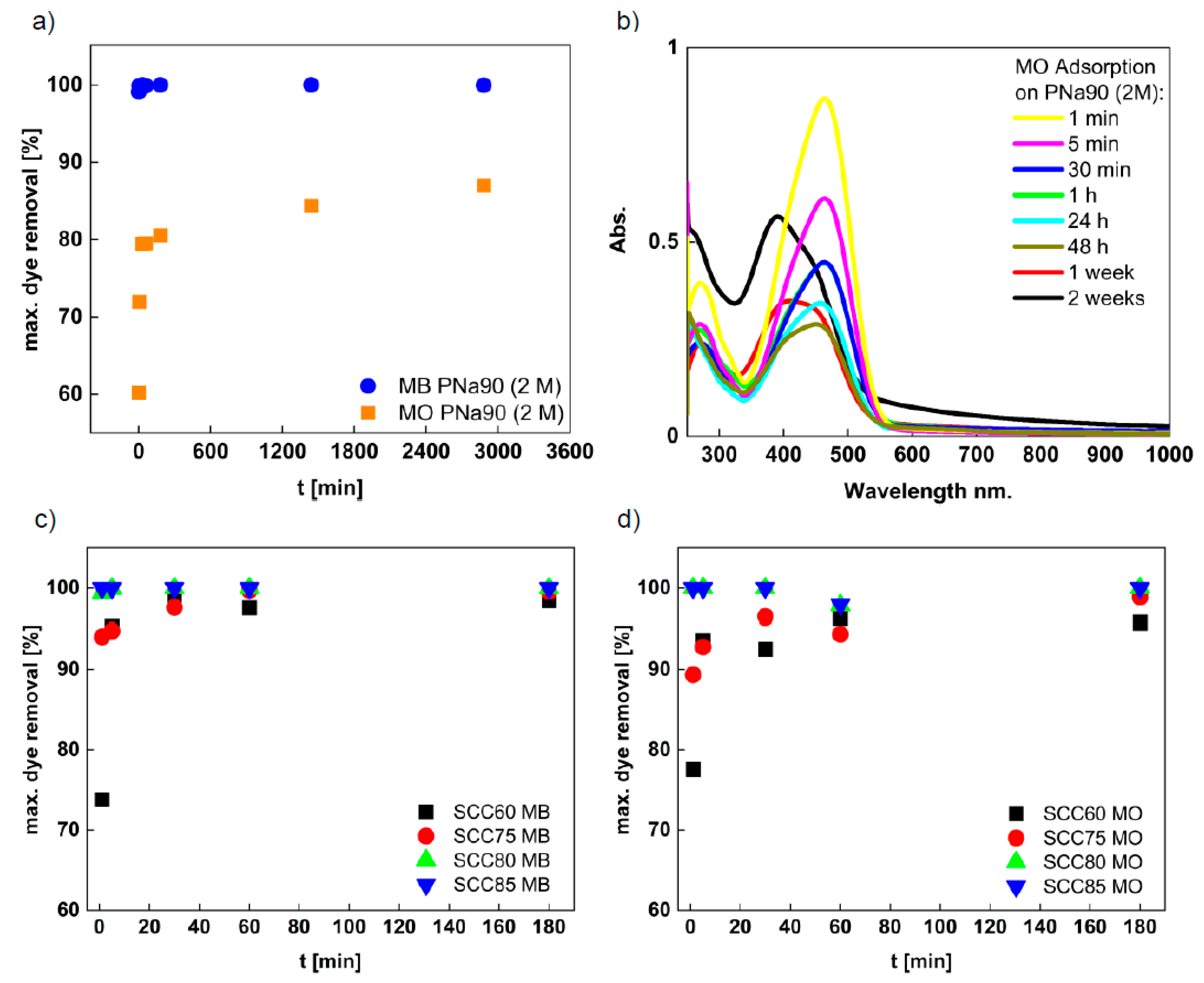

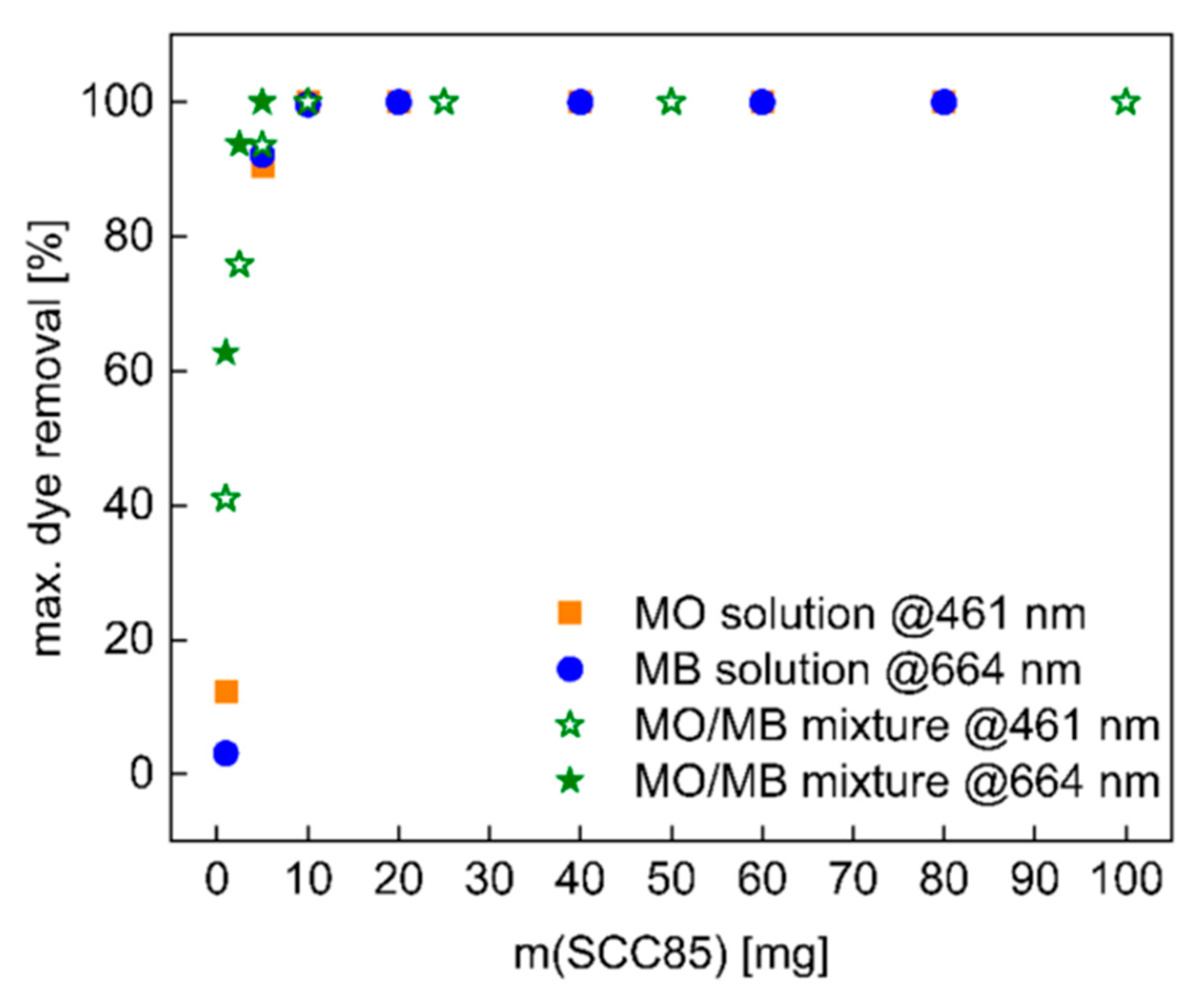

3.3. Dye Removal

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Cecen, F.; Aktas, Ö. Activated Carbon for Water and Wastewater Treatment: Integration of Adsorption and Biological Treatment; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany; Chichester, UK, 2012; ISBN 9783527324712. [Google Scholar]

- Perrich, J.R. Activated Carbon Adsorption for Wastewater Treatment; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1981; ISBN 0849356938. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, H.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Activated Carbon, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA, 2006; ISBN 0080444636. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, J.; Shahid, U.B.; Hijab, M.; Mackey, H.; McKay, G. Production and applications of activated carbons as adsorbents from olive stones. Biomass Conv. Bioref. 2019, 9, 775–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, H.; Xue, Y.; Long, L.; Hu, X. Adsorption of nitrate onto biochar derived from agricultural residuals. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 77, 548–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Unuabonah, E.I.; Nöske, R.; Weber, J.; Günter, C.; Taubert, A. New micro/mesoporous nanocomposite material from low-cost sources for the efficient removal of aromatic and pathogenic pollutants from water. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2019, 10, 119–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucar, S.; Erdem, M.; Tay, T.; Karagöz, S. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon produced from pomegranate seeds by ZnCl2 activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 8890–8896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, B.; Kannan, C.; Karthikeyan, S. Preparation and characterization of activated carbon prepared from balsamodendron caudatum wood waste through various activation processes. Rasayan J. Chem. 2012, 5, 321–327. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Awang, M.; Mohosina, B.S.; Kamaruzzaman, B.Y.; Nik, W.W.; Adnan, C. Waste Palm Shell Converted to High Efficient Activated Carbon by Chemical Activation Method and Its Adsorption Capacity Tested by Water Filtration. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 1, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Okman, I.; Karagöz, S.; Tay, T.; Erdem, M. Activated Carbons from Grape Seeds By Chemical Activation With Potassium Carbonate And Potassium Hydroxide. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2014, 293, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habeeb, O.A.; Ramesh, K.; Ali, G.A.; Yunus, R.b.M. Low-cost and eco-friendly activated carbon from modified palm kernel shell for hydrogen sulfide removal from wastewater: Adsorption and kinetic studies. DWT 2017, 84, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gulipalli, S.; Prasad, B.; Wasewar, K.L. Batch study, equilibrium and kinetics of adsorption of selenium using husk ash. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2011, 6, 586–605. [Google Scholar]

- Fidel, R.B.; Laird, D.A.; Spokas, K.A. Sorption of ammonium and nitrate to biochars is electrostatic and pH-dependent. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, D.; Samal, D.P.; BC, M. Preparation of Activated Carbon from Green Coconut Shell and its Characterization. J. Chem. Eng. Process. Technol. 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerda-Correa, E.M.; Diaz-Diez, M.A.; Macias-Garcia, A.; Ganan-Gomez, J. Preparation of activated carbons previously treated with sulfuric acid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2006, 252, 6042–6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caturla, F.; Molina-Sabio, M.; Rodríguez-Reinoso, F. Preparation of Activated Carbon by Chemical Activation with ZnCl2. Carbon 1991, 29, 999–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, D.C.; Araújo, J.C.S.; Bastos-Neto, M.; Torres, A.E.B.; Jaguaribe, E.F.; Cavalcante, C.L. Microporous activated carbon prepared from coconut shells using chemical activation with zinc chloride. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2007, 100, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppireddy, S.K.R.; Rashid, K.; Al Shoaibi, A.; Srinivasakannan, C. Production and characterization of porous carbon from date palm seeds by chemical activation with H3PO4: Process optimization for maximizing adsorption of methylene blue. Chem. Eng. Commun. 2014, 201, 1021–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, S.; Tay, T.; Ucar, S.; Erdem, M. Activated carbons from waste biomass by sulfuric acid activation and their use on methylene blue adsorption. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 6214–6222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, S.; Siddiqi, H.; Meikap, B.C.; Sen, T.K.; Khiadani, M. Preparation and Characterization of Raw and Inorganic Acid-Activated Pine Cone Biochar and Its Application in the Removal of Aqueous-Phase Pb2+ Metal Ions by Adsorption. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2020, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuabonah, E.I.; Agunbiade, F.O.; Alfred, M.O.; Adewumi, T.A.; Okoli, C.P.; Omorogie, M.O.; Akanbi, M.O.; Ofomaja, A.E.; Taubert, A. Facile synthesis of new amino-functionalized agrogenic hybrid composite clay adsorbents for phosphate capture and recovery from water. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 164, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuabonah, E.I.; Günter, C.; Weber, J.; Lubahn, S.; Taubert, A. Hybrid Clay: A New Highly Efficient Adsorbent for Water Treatment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 1, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unuabonah, E.I.; Taubert, A. Clay–polymer nanocomposites (CPNs): Adsorbents of the future for water treatment. Appl. Clay Sci. 2014, 99, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liedtke, A. Kaffeereport2019, Hamburg. 2019. Available online: https://www.tchibo.com/servlet/content/1302446/-/starteseite-deutsch/tchibo-unternehmen/sortiment/kaffee/kaffeereport/kaffeereport-2019.html;jsessionid=187477F94634FC8DBD370118F4B1A1A8.deliveryWorker (accessed on 5 July 2021).

- Iakovleva, E.; Sillanpää, M.; Maydannik, P.; Liu, J.T.; Allen, S.; Albadarin, A.B.; Mangwandi, C. Manufacturing of novel low-cost adsorbent: Co-granulation of limestone and coffee waste. J. Environ. Manag. 2017, 203, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cerino-Córdova, F.J.; Díaz-Flores, P.E.; García-Reyes, R.B.; Soto-Regalado, E.; Gómez-González, R.; Garza-González, M.T.; Bustamante-Alcántara, E. Biosorption of Cu(II) and Pb(II) from aqueous solutions by chemically modified spent coffee grains. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 10, 611–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Azouaoua, N.; Sadaouia, Z.; Mokaddema, H. Removal of Lead from Aqueous Solution onto Untreated Coffee Grounds: A Fixed-bed Column Study. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2014, 38, 151–156. [Google Scholar]

- Azouaoua, N.; Sadaouia, Z.; Djaafrib, A.; Mokaddema, H. Adsorption of cadmium from aqueous solution onto untreated coffee grounds: Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 184, 126–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franca, A.S.; Oliveira, L.S.; Ferreira, M.E. Kinetics and equilibrium studies of methylene blue adsorption by spent coffee grounds. Desalination 2009, 249, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávila-Guzmán, N.E.; de Jesús Cerino-Córdova, F.; Soto-Regalado, E.; Rangel-Mendez, J.R.; Díaz-Flores, P.E.; Garza-Gonzalez, M.T.; Loredo-Medrano, J.A. Copper Biosorption by Spent Coffee Ground: Equilibrium, Kinetics, and Mechanism. Clean Soil Air Water 2013, 41, 557–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, M.; Guerreiro, M.C.; Ramos, P.H.; de Oliveira, L.C.A.; Sapag, K. Activated carbon prepared from coffee pulp: Potential adsorbent of organic contaminants in aqueous solution. Water Sci. Technol. 2013, 68, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ching, S.L.; Yusoff, M.S.; Aziz, H.A.; Umar, M. Influence of impregnation ratio on coffee ground activated carbon as landfill leachate adsorbent for removal of total iron and orthophosphate. Desalination 2011, 279, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, K.C.; Baek, S.B.; Lee, W.-G.; Meyyappan, M.; Kim, K.S. Activated carbon derived from waste coffee grounds for stable methane storage. Nanotechnology 2015, 26, 385602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamine, S.M.; Ridha, C.; Mahfoud, H.-M.; Mouad, C.; Lotfi, B.; Al-Dujaili, A.H. Chemical Activation of an Activated Carbon Prepared from Coffee Residue. Energy Procedia 2014, 50, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alves, A.C.F.; Antero, R.V.P.; Oliveira, S.B.d.; Ojala, S.A.; Scalize, P.S. Activated carbon produced from waste coffee grounds for an effective removal of bisphenol-A in aqueous medium. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 24850–24862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanai, N.; Yoshihara, N.; Kawamura, I. Solid-state NMR characterization of triacylglycerol and polysaccharides in coffee beans. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2019, 83, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carruthers-Taylor, T.; Banerjee, J.; Little, K.; Wong, Y.F.; Jackson, W.R.; Patti, A.F. Chemical Nature of Spent Coffee Grounds and Husks. Aust. J. Chem. 2020, 73, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kögel-Knabner, I. The macromolecular organic composition of plant and microbial residues as inputs to soil organic matter. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002, 34, 139–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Duan, D.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ran, Y. Composition and structure of natural organic matter through advanced nuclear magnetic resonance techniques. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2017, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taleb, F.; Ammar, M.; Mosbah, M.B.; Salem, R.B.; Moussaoui, Y. Chemical modification of lignin derived from spent coffee grounds for methylene blue adsorption. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-H.; Lehmann, J.; Thies, J.E.; Burton, S.D. Stability of black carbon in soils across a climatic gradient. J. Geophys. Res. 2008, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rashidi, N.A.; Yusup, S.; Ahmad, M.M.; Mohamed, N.M.; Hameed, B.H. Activated Carbon from the Renewable Agricultural Residues Using Single Step Physical Activation: A Preliminary Analysis. APCBEE Procedia 2012, 3, 84–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Molina-Sabio, M.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F. Role of chemical activation in the development of carbon porosity. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2004, 241, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Chemical, Functional, and Structural Properties of Spent Coffee Grounds and Coffee Silverskin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 3493–3503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gao, G.; Cheong, L.-Z.; Wang, D.; Shen, C. Pyrolytic carbon derived from spent coffee grounds as anode for sodium-ion batteries. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2018, 1, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Ouyang, F. Adsorption properties of biomass-based activated carbon prepared with spent coffee grounds and pomelo skin by phosphoric acid activation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2013, 268, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunusa, W.R.; Isa, I.; Laliyo, L.A.R.; Iyabu, H. FTIR, XRD and SEM Analysis of Microcrystalline Cellulose (MCC) Fibers from Corncorbs in Alkaline Treatment. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2018, 1028, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hesas, R.H.; Arami-Niya, A.; Daud, W.M.A.W.; Sahu, J.N. Preparation and Characterization of Activated Carbon from Apple Waste by Microwave-Assisted Phosphoric Acid Activation: Application in Methylene Blue. BioResources 2013, 8, 2950–2966. [Google Scholar]

- Ciolacu, D.; Ciolacu, F.; Popa, V.I. Amorphous Cellulose—Structure and Characterization. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2011, 45, 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ihlenburg, R.B.J.; Lehnen, A.-C.; Koetz, J.; Taubert, A. Sulfobetaine Cryogels for Preferential Adsorption of Methyl Orange from Mixed Dye Solutions. Polymers 2021, 13, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillman, P.K. CNS toxicity involving methylene blue: The exemplar for understanding and predicting drug interactions that precipitate serotonin toxicity. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nejib, A.; Joelle, D.; Fadhila, A.; Sophie, G.; Malika, T.-A. Adsorption of anionic dye on natural and organophilic clays: Effect of textile dyeing additives. DWT 2014, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grassi, M.; Rizzo, L.; Farina, A. Endocrine disruptors compounds, pharmaceuticals and personal care products in urban wastewater: Implications for agricultural reuse and their removal by adsorption process. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2013, 20, 3616–3628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Label | Index ## | Pretreatment | TT (°C) | TP (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCD | - | - | - | - |

| PSC | 50 | - | - | 500 |

| PNa | 90 | NaOH (2 M) | 90 | 500 |

| SCC | 50 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | - | 500 |

| 60 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | 600 | ||

| 65 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | 650 | ||

| 75 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | 750 | ||

| 80 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | 800 | ||

| 85 | dry CaCO3, mixing ratio 1:1 (w/w) | 850 |

| TP (°C) | C (%) | H (%) | N (%) | S (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCD | - | 56.9 | 10.3 | 1.8 | - |

| PNa90 (2 M) | 500 | 41.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

| SCC60 | 600 | 70.3 | 2.4 | 2.6 | 0.5 |

| SCC75 | 750 | 82.0 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 0.5 |

| SCC80 | 800 | 82.4 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 0.5 |

| SCC85 | 850 | 82.2 | 1.4 | 2.5 | 0.4 |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Classification |

|---|---|

| 3500–3300 | O–H (stretching, intermolecular) |

| 2930–2840 | C–H (amorphous cellulose, caffeine), aromatic methoxyl and methylene groups, methyl groups |

| 1740 | C=O (stretching, esters) |

| 1700–1600 | caffeine, chlorogenic acids |

| 1600–1300 | C=C (aromatic compounds, oils, caffeine) |

| 1430 | C–H2 (crystallinity bond of cellulose) |

| 1284–1240 | C–O (aromatic ethers, esters, phenol) |

| 1100–900 | C–O (polysaccharides) |

| 900–800 | Β–glycosidic bond of cellulose |

| Sample Name | BET Surface (m2/g) | Pore Size (Å) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCC60 | 8.1 | 182.3 | 0.010 |

| SCC65 | 17.9 | 236.6 | 0.015 |

| SCC75 | 10.9 | 217.1 | 0.020 |

| SCC80 | 56.1 | 63.1 | 0.035 |

| SCC85 | 166.8 | 48.6 | 0.109 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Block, I.; Günter, C.; Duarte Rodrigues, A.; Paasch, S.; Hesemann, P.; Taubert, A. Carbon Adsorbents from Spent Coffee for Removal of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange from Water. Materials 2021, 14, 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14143996

Block I, Günter C, Duarte Rodrigues A, Paasch S, Hesemann P, Taubert A. Carbon Adsorbents from Spent Coffee for Removal of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange from Water. Materials. 2021; 14(14):3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14143996

Chicago/Turabian StyleBlock, Inga, Christina Günter, Alysson Duarte Rodrigues, Silvia Paasch, Peter Hesemann, and Andreas Taubert. 2021. "Carbon Adsorbents from Spent Coffee for Removal of Methylene Blue and Methyl Orange from Water" Materials 14, no. 14: 3996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14143996