Synthesis of Phosphonated Carbon Nanotubes: New Insight into Carbon Nanotubes Functionalization

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Characterization

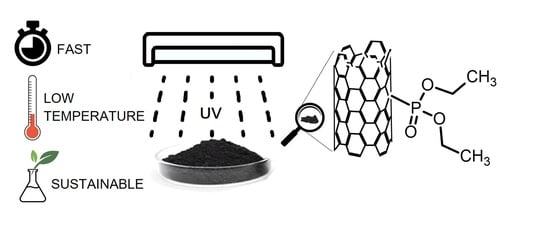

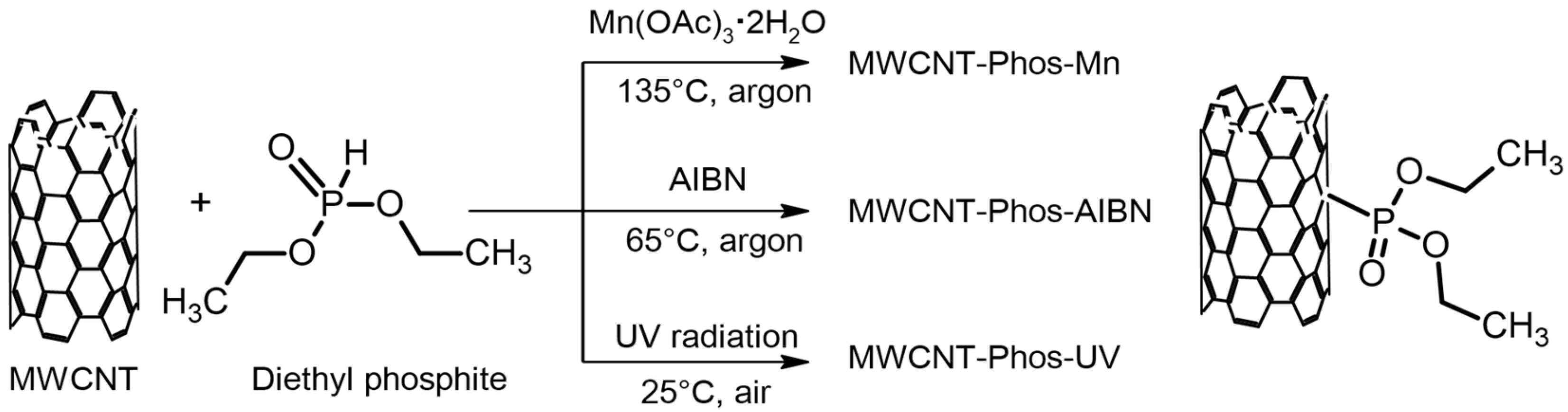

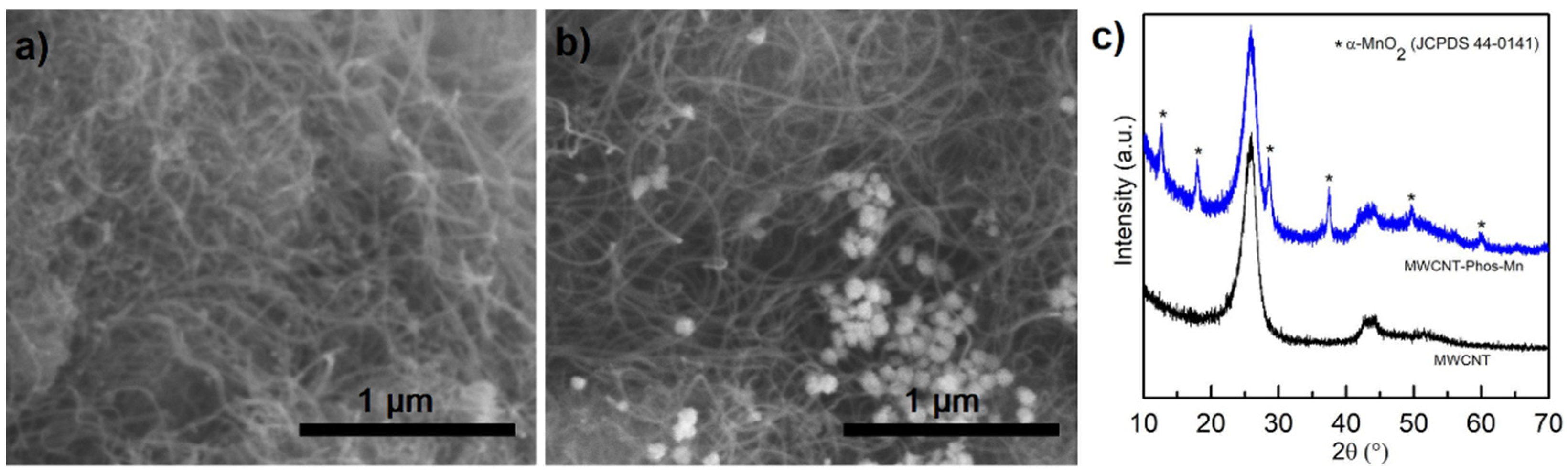

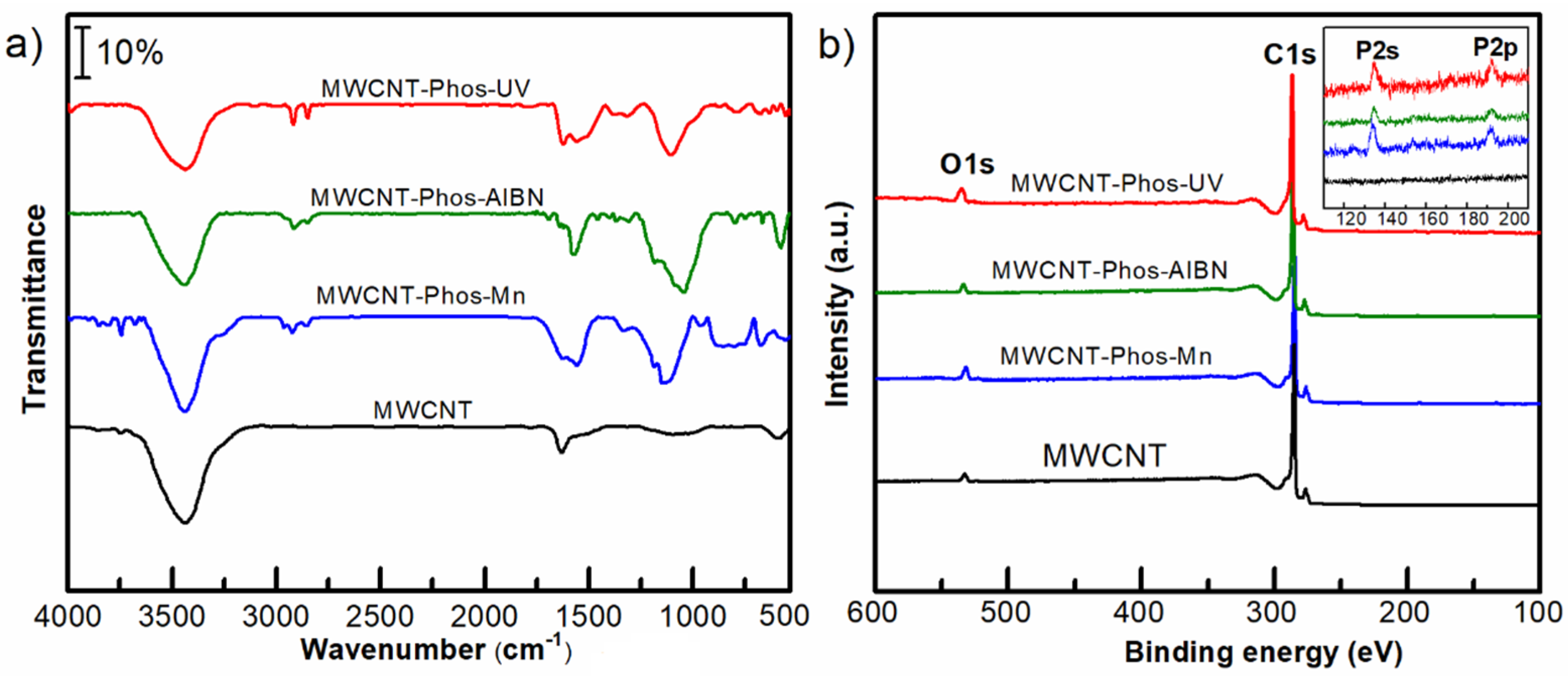

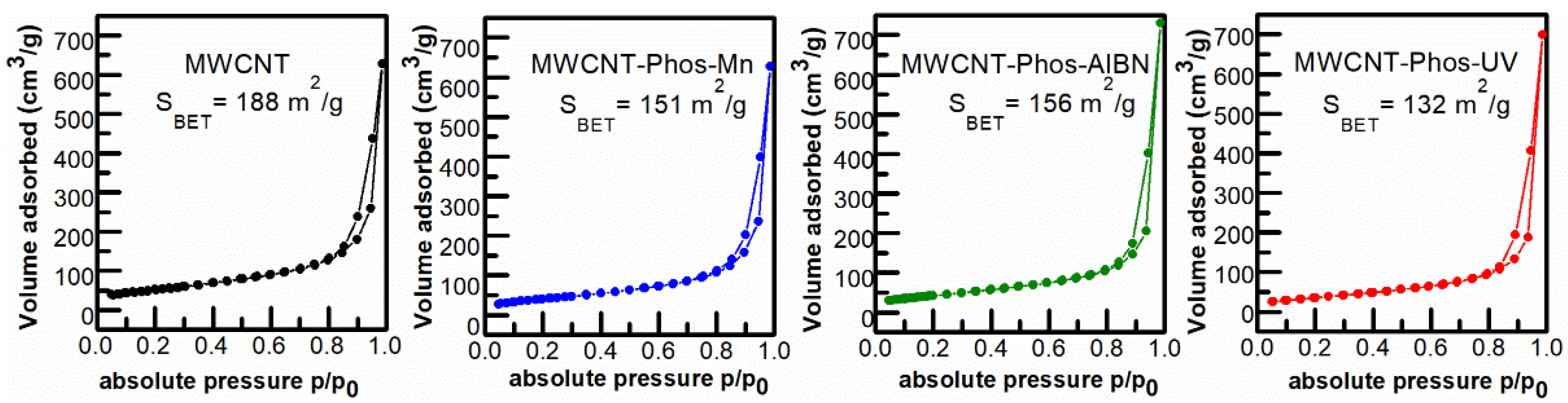

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Camilli, L.; Passacantando, M. Advances on Sensors Based on Carbon Nanotubes. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, V.; Savagatrup, S.; He, M.; Lin, S.; Swager, T.M. Carbon Nanotube Chemical Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 599–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Li, F.; Cheng, H.-M. Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene for Flexible Electrochemical Energy Storage: From Materials to Devices. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4306–4337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antiohos, D.; Romano, M.; Chen, J.; Razal, J.M. Carbon Nanotubes for Energy Applications. In Syntheses and Applications of Carbon Nanotubes and Their Composites; Suzuki, S., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2013; Volume 22, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanhui, Y.; Miao, J.; Yang, Z.; Xiao, F.-X.; Bin Yang, H.; Liu, B.; Yang, Y. Carbon nanotube catalysts: Recent advances in synthesis, characterization and applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 3295–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MabenaSuprakas, L.F.; Ray, S.S.; Mhlanga, S.D.; Coville, N.J. Nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes as a metal catalyst support. Appl. Nanosci. 2011, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, B.; Mandal, S.; Tsang, Y.F.; Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Ok, Y.S. Designer carbon nanotubes for contaminant removal in water and wastewater: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ihsanullah; Abbas, A.; Al-Amer, A.M.; Laoui, T.; Al-Marri, M.J.; Nasser, M.S.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M.A. Heavy metal removal from aqueous solution by advanced carbon nanotubes: Critical review of adsorption applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2016, 157, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, M.; Solati, N.; Ghasemi, A.; Estiar, M.A.; Hashemkhani, M.; Kiani, P.; Mohamed, E.; Saeidi, A.; Taheri, M.; Avci, P.; et al. Carbon nanotubes part II: A remarkable carrier for drug and gene delivery. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2015, 12, 1089–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianco, A.; Kostarelos, K.; Partidos, C.D.; Prato, M. Biomedical applications of functionalised carbon nanotubes. Chem. Commun. 2005, 5, 571–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Cividanes, L.; Brito, F.S.; de Menezes, B.R.C.; Franceschi, W.; Simonetti, E.A.N.; Thim, G.P. Functionalizing Graphene and Carbon Nanotubes, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: Basingstoke, UK, 2016; pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramanian, K.; Burghard, M. Chemically Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes. Small 2005, 1, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Soltanian, S. Surface functionalization of carbon nanotubes: Fabrication and applications. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 109916–109935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saka, C. Overview on the Surface Functionalization Mechanism and Determination of Surface Functional Groups of Plasma Treated Carbon Nanotubes. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018, 48, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deline, A.R.; Frank, B.P.; Smith, C.L.; Sigmon, L.R.; Wallace, A.N.; Gallagher, M.J.; Goodwin, J.D.G.; Durkin, D.P.; Fairbrother, D.H. Influence of Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups on the Environmental Properties, Transformations, and Toxicity of Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 11651–11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.; Rehman, S.A.U.; Luan, H.-Y.; Farid, M.U.; Huang, H. Challenges and opportunities in functional carbon nanotubes for membrane-based water treatment and desalination. Sci. Total. Environ. 2019, 646, 1126–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.K.; Mahmood, Q.; Park, H.S. Surface functional groups of carbon nanotubes to manipulate capacitive behaviors. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 12304–12309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.; Yu, J.; Hu, Z. Thiol functionalized carbon nanotubes: Synthesis by sulfur chemistry and their multi-purpose applications. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 447, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Rupper, P.; Gaan, S. Recent Development in Phosphonic Acid-Based Organic Coatings on Aluminum. Coatings 2017, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabakaran, M.; Vadivu, K.; Ramesh, S.; Periasamy, V. Corrosion protection of mild steel by a new phosphonate inhibitor system in aqueous solution. Egypt. J. Pet. 2014, 23, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowack, B. Environmental chemistry of phosphonates. Water Res. 2003, 37, 2533–2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.; Kim, J.; Jang, B.N. Synthesis and performance of cyclic phosphorus-containing flame retardants. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2008, 93, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-L.; Hsiue, G.-H.; Lee, R.-H.; Chiu, Y.-S. Phosphorus-containing epoxy for flame retardant. III: Using phosphorylated diamines as curing agents. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1997, 63, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudaev, P.; Kolpinskaya, N.; Chistyakov, E. Organophosphorous extractants for metals. Hydrometallurgy 2021, 201, 105558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D. Development course of separating rare earths with acid phosphorus extractants: A critical review. J. Rare Earths 2019, 37, 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galezowska, J.; Gumienna-Kontecka, E. Phosphonates, their complexes and bio-applications: A spectrum of surprising diversity. Co-ord. Chem. Rev. 2012, 256, 105–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevrain, C.M.; Berchel, M.; Couthon, H.; Jaffrès, P.-A. Phosphonic acid: Preparation and applications. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2017, 13, 2186–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Li, P.; Fu, G.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lu, T. Efficient anchorage of highly dispersed and ultrafine palladium nanoparticles on the water-soluble phosphonate functionalized multiwall carbon nanotubes. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2013, 129, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, H.; Ding, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, Y.; Wei, H.; Cai, C.; Lu, T. Synthesis of water-soluble phosphonate functionalized single-walled carbon nanotubes and their applications in biosensing. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 15370–15378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sainsbury, T.; Fitzmaurice, D. Templated Assembly of Semiconductor and Insulator Nanoparticles at the Surface of Covalently Modified Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Mater. 2004, 16, 3780–3790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Hu, H.; Mandal, A.S.K.; Haddon, R. A Bone Mimic Based on the Self-Assembly of Hydroxyapatite on Chemically Functionalized Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes. Chem. Mater. 2005, 17, 3235–3241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maho, A.; Detriche, S.; Fonder, G.; Delhalle, J.; Mekhalif, Z. Electrochemical Co-Deposition of Phosphonate-Modified Carbon Nanotubes and Tantalum on Nitinol. ChemElectroChem 2014, 1, 896–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, R.; Bipinlal, U.; Kurungot, S.; Pillai, V.K. Enhanced electrocatalytic performance of functionalized carbon nanotube electrodes for oxygen reduction in proton exchange membrane fuel cells. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 10312–10317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oki, A.; Adams, L.; Khabashesku, V.; Edigin, Y.; Biney, P.; Luo, Z. Dispersion of aminoalkylsilyl ester or amine alkyl-phosphonic acid side wall functionalized carbon nanotubes in silica using sol–gel processing. Mater. Lett. 2008, 62, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Sardarian, A.R.; Doroodmand, M.M. Preparation and characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), functionalized with phosphonic acid (MWCNTs–C–PO3H2) and its application as a novel, efficient, heterogeneous, highly selective and reusable catalyst for acetylation of alcohols, phenols, aromatic amines, and thiols. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2013, 11, 673–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, F.; Sardarian, A.R.; Doroodmand, M.M. An efficient method for synthesis of acylals from aldehydes using multi-walled carbon nanotubes functionalized with phosphonic acid (MWCNTs-C-PO3H2). Chin. Chem. Lett. 2014, 25, 1630–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleja, A.A.; Mbianda, X.; Krause, R.; Pillay, K. Synthesis, characterization and thermal decomposition behaviour of triphenylphosphine-linked multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Carbon 2012, 50, 2741–2751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muleja, A.A.; Mbianda, X.Y.; Pillay, K.; Krause, R.W. Phosphine functionalised multiwalled carbon nanotubes: A new adsorbent for the removal of nickel from aqueous solution. J. Environ. Sci. 2012, 24, 1133–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, K.; Jabłonowska, E.; Stolarczyk, K.; Wiser, R.; Bilewicz, R.; Roberts, K.P.; Biernat, J. Chemically modified carbon nanotubes: Synthesis and implementation. Pol. J. Chem. 2008, 82, 1309–1313. [Google Scholar]

- Żelechowska, K.; Sobota, D.; Cieślik, B.; Prześniak-Welenc, M.; Łapiński, M.; Biernat, J.F. Bis-phosphonated carbon nanotubes: One pot synthesis and their application as efficient adsorbent of mercury. Full Nanotub. Carbon Nanostruct. 2018, 26, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maho, A.; Detriche, S.; Delhalle, J.; Mekhalif, Z. Sol–gel synthesis of tantalum oxide and phosphonic acid-modified carbon nanotubes composite coatings on titanium surfaces. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2013, 33, 2686–2697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, X.-Q.; Zou, J.-P.; Yi, W.-B.; Zhang, W. Recent advances in sulfur- and phosphorous-centered radical reactions for the formation of S–C and P–C bonds. Tetrahedron 2015, 71, 7481–7529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-W.; Wang, C.-Z.; Zhu, S.-E.; Murata, Y. Manganese(iii) acetate-mediated radical reaction of [60]fullerene with phosphonate esters affording unprecedented separable singly-bonded [60]fullerene dimers. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 6111–6113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-W.; Wang, C.-Z.; Zou, J.-P. Radical Reaction of [60]Fullerene with Phosphorus Compounds Mediated by Manganese(III) Acetate. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 6088–6094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luboch, E.; Wagner-Wysiecka, E.; Szulc, P.; Chojnacki, J.; Szwarc-Karabyka, K.; Łukasik, N.; Murawski, M.; Kosno, M. Photochemical Rearrangement of a 19-Membered Azoxybenzocrown: Products and their Properties. ChemPlusChem 2020, 85, 2067–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łukasik, N.; Chojnacki, J.; Luboch, E.; Okuniewski, A.; Wagner-Wysiecka, E. Photoresponsive, amide-based derivative of embonic acid for anion recognition. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 2020, 390, 112307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Jeught, S.; Stevens, C.V. Direct Phosphonylation of Aromatic Azaheterocycles. Chem. Rev. 2009, 109, 2672–2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wiemer, D.F. Synthesis of nonracemic phosphonates. Tetrahedron 1997, 53, 16609–16644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leca, D.; Fensterbank, L.; Lacôte, E.; Malacria, M. Recent advances in the use of phosphorus-centered radicals in organic chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2005, 34, 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marque, S.; Tordo, P. Reactivity of Phosphorus Centered Radicals. In New Aspects in Phosphorus Chemistry V; Majoral, J.-P., Ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2005; pp. 43–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bentrude, W.G. Free-Radical Reactions of Organophosphorus (3) Compounds. In The Chemistry of Organophosphorous Compounds; Hartley, F.R., Ed.; Wiley: Chichester, UK, 1990; Volume 1, pp. 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bahr, J.L.; Tour, J.M. Highly Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes Using in Situ Generated Diazonium Compounds. Chem. Mater. 2001, 13, 3823–3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, K.; Roberts, K.; Wiser, R.; Biernat, J.; Jabłonowska, E.; Bilewicz, R. Synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical testing of carbon nanotubes derivatized with azobenzene and anthraquinone. Carbon 2009, 47, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stolarczyk, K.; Sepelowska, M.; Lyp, D.; Żelechowska, K.; Biernat, J.F.; Rogalski, J.; Farmer, K.D.; Roberts, K.N.; Bilewicz, R. Hybrid biobattery based on arylated carbon nanotubes and laccase. Bioelectrochemistry 2012, 87, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaśkiewicz, M.; Nazaruk, E.; Żelechowska, K.; Biernat, J.F.; Rogalski, J.; Bilewicz, R. Fully enzymatic mediatorless fuel cell with efficient naphthylated carbon nanotube–laccase composite cathodes. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 20, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żelechowska, K.; Stolarczyk, K.; Łyp, D.; Rogalski, J.; Roberts, K.P.; Bilewicz, R.; Biernat, J.F. Aryl and N-arylamide carbon nanotubes for electrical coupling of laccase to electrodes in biofuel cells and biobatteries. Biocybern. Biomed. Eng. 2013, 33, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matyszewska, D.; Napora, E.; Żelechowska, K.; Biernat, J.F.; Bilewicz, R. Synthesis, characterization, and interactions of single-walled carbon nanotubes modified with doxorubicin with Langmuir–Blodgett biomimetic membranes. J. Nanopart. Res. 2018, 20, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazaee, M.; Xia, W.; Lackner, G.; Mendes, R.G.; Rümmeli, M.; Muhler, M.; Lupascu, D.C. Dispersibility of vapor phase oxygen and nitrogen functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes in various organic solvents. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 26208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Huang, J.; Kong, X.; Peng, H.; Shui, H.; Qian, F.; Zhu, L.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, Q. Hydrothermal synthesis of porous phosphorus-doped carbon nanotubes and their use in the oxygen reduction reaction and lithium-sulfur batteries. New Carbon Mater. 2016, 31, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.K.; Iyer, P.K.; Giri, P.K. Distinguishing defect induced intermediate frequency modes from combination modes in the Raman spectrum of single walled carbon nanotubes. J. Appl. Phys. 2012, 111, 064304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Che, B.D.; Nguyen, B.Q.; Nguyen, L.-T.T.; Nguyen, H.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Van Le, T.; Nguyen, N.H. The impact of different multi-walled carbon nanotubes on the X-band microwave absorption of their epoxy nanocomposites. Chem. Cent. J. 2015, 9, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.C.; Min, K.-I.; Jeong, M.S. Novel Method of Evaluating the Purity of Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Using Raman Spectroscopy. J. Nanomater. 2013, 2013, 615915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Kim, S.-I.; Lee, M.; Ezazi, M.; Kim, H.-D.; Kwon, G.; Lee, D.H. Synthesis of oxygen functionalized carbon nanotubes and their application for selective catalytic reduction of NOx with NH3. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 16700–16708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wepasnick, K.A.; Smith, B.A.; Schrote, K.E.; Wilson, H.K.; Diegelmann, S.R.; Fairbrother, D.H. Surface and structural characterization of multi-walled carbon nanotubes following different oxidative treatments. Carbon 2011, 49, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osswald, S.; Havel, M.; Gogotsi, Y. Monitoring oxidation of multiwalled carbon nanotubes by Raman spectroscopy. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2007, 38, 728–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zheng, G.; Lee, H.-W.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Yao, H.; Yang, W.; Cui, Y. Formation of Stable Phosphorus–Carbon Bond for Enhanced Performance in Black Phosphorus Nanoparticle–Graphite Composite Battery Anodes. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 4573–4580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H. Facile Preparation of 1D a-MnO2 as Anode Materials for Li-ion Batteries. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2016, 11, 8964–8971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ţucureanu, V.; Matei, A.; Avram, A.M. FTIR Spectroscopy for Carbon Family Study. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2016, 46, 502–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu, A.V.; Karuppanan, K.K.; Pullithadathil, B. Highly Surface Active Phosphorus-Doped Onion-Like Carbon Nanostructures: Ultrasensitive, Fully Reversible, and Portable NH3 Gas Sensors. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 2208–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, F.; Tao, L.-M.; Deng, Y.-C.; Wang, Q.-H.; Song, W.-G. Phosphorus doped graphene nanosheets for room temperature NH3 sensing. New J. Chem. 2014, 38, 2269–2272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Bhandari, S.; Khastgir, D. Synthesis of MnO2 nanoparticles and their effective utilization as UV protectors for outdoor high voltage polymeric insulators used in power transmission lines. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32876–32890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okpalugo, T.; Papakonstantinou, P.; Murphy, H.; McLaughlin, J.; Brown, N. High resolution XPS characterization of chemical functionalised MWCNTs and SWCNTs. Carbon 2005, 43, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, G.; Yu, S.; Zhang, J.; Tang, Y.; Li, P.; Ren, Y. Kinetics and Interfacial Thermodynamics of the pH-Related Sorption of Tetrabromobisphenol A onto Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 20968–20977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinsley, D.M.; Sharp, J.H. Thermal analysis of manganese dioxide in controlled atmospheres. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 1971, 3, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.-J.; Jeon, I.-Y.; Seo, J.-M.; Dai, L.; Baek, J.-B. Graphene Phosphonic Acid as an Efficient Flame Retardant. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2820–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, X.; Radovic, L. Inhibition of catalytic oxidation of carbon/carbon composites by phosphorus. Carbon 2006, 44, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Kingon, A.; Kukovecz, Á.; Konya, Z.; Vilarinho, P.M. Studies on the thermal decomposition of multiwall carbon nanotubes under different atmospheres. Mater. Lett. 2013, 90, 165–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, S.-U.; Nahm, K.S. Hydrogen uptake of high-energy ball milled nickel-multiwalled carbon nanotube composites. Mater. Res. Bull. 2014, 49, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Zeng, G.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, C.; Cheng, M.; Liu, Y.; Hu, L.; Wan, J.; Zhou, C.; et al. Adsorption of tetracycline antibiotics from aqueous solutions on nanocomposite multi-walled carbon nanotube functionalized MIL-53(Fe) as new adsorbent. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 627, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample ID | MWCNTs | Radical Initiator | Phosphate Groups Source | Reaction Medium | Atm | Temp. (°C) | Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNT- Phos-Mn | 100 mg | 90 mg Mn(OAc)3 ·2H2O | 3 mL of (C2H5O)2P(O)H | 3 mL of 1,2-dichlorobenzene | Ar | 135 | 5 |

| MWCNT- Phos-AIBN | 100 mg | (150 mg + 150 mg) AIBN | 3 mL of (C2H5O)2P(O)H | (C2H5O)2P(O)H | Ar | 65 | 5 |

| MWCNT- Phos-UV | 100 mg | UV radiation (365–370 nm) | 3 mL of (C2H5O)2P(O)H | (C2H5O)2P(O)H | Air | 25 | 1 |

| D Band | G Band | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Position (cm−1) | FWHM (cm−1) | Position (cm−1) | FWHM (cm−1) | ID/IG | |

| MWCNT | 1337 | 57 | 1596 | 69 | 1.88 |

| MWCNT–Phos–Mn | 1340 | 62 | 1597 | 77 | 1.53 |

| MWCNT–Phos–AIBN | 1334 | 65 | 1593 | 81 | 1.64 |

| MWCNT–Phos–UV | 1333 | 63 | 1593 | 72 | 1.49 |

| Sample Name | Temperature Range (°C) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 40–450 | 450–600 | 600–850 | |

| Mass Loss in % (DTG Peak Position (°C)) | |||

| MWCNT | 0.87 (100, 270) | 0.43 (-) | 0.75 (-) |

| MWCNT–Phos–Mn | 3.33 (166, 317) | 0.97 (520) | 1.63 (780) |

| MWCNT–Phos–AIBN | 2.51 (148, 272) | 0.34 (-) | 1.20 (710) |

| MWCNT–Phos–UV | 2.93 (158, 220) | 0.29 (-) | 1.43 (740) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nadolska, M.; Prześniak-Welenc, M.; Łapiński, M.; Sadowska, K. Synthesis of Phosphonated Carbon Nanotubes: New Insight into Carbon Nanotubes Functionalization. Materials 2021, 14, 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14112726

Nadolska M, Prześniak-Welenc M, Łapiński M, Sadowska K. Synthesis of Phosphonated Carbon Nanotubes: New Insight into Carbon Nanotubes Functionalization. Materials. 2021; 14(11):2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14112726

Chicago/Turabian StyleNadolska, Małgorzata, Marta Prześniak-Welenc, Marcin Łapiński, and Kamila Sadowska. 2021. "Synthesis of Phosphonated Carbon Nanotubes: New Insight into Carbon Nanotubes Functionalization" Materials 14, no. 11: 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14112726

APA StyleNadolska, M., Prześniak-Welenc, M., Łapiński, M., & Sadowska, K. (2021). Synthesis of Phosphonated Carbon Nanotubes: New Insight into Carbon Nanotubes Functionalization. Materials, 14(11), 2726. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma14112726